For someone with an entrenched pattern of violent criminal behaviour that is not caused by a major mental illness, intervention to reduce violence risk is one of the few options available for rehabilitation. Assessment and treatment of violence should be based on theoretically sound and empirically validated principles, and should be integrated in their implementation to increase the likelihood of successful outcome. However, common practice often lags behind theory and treatment efficacy suffers. We use the Violence Reduction Programme (VRP) and the Violence Risk Scale (VRS) to illustrate how a theoretically derived and empirically driven treatment programme and assessment process can be integrated in practice. We then describe the participants of a similar programme, Aggressive Behaviour Control Programme, currently being offered to illustrate the principles discussed and to test the efficacy of the programme through outcome evaluations.

Effective correctional treatment

Risk-need-responsivity principles have been identified as useful guidelines for treatment interventions designed to reduce the risk of recidivism. Treatment approaches, often referred to as correctional treatment, that follow the risk-need-responsivity principles are generally more effective in reducing the risk of recidivism in adult and young offenders than those that do not follow such principles (see Reference Andrews, Zinger and HogeAndrews et al, 1990; Reference Andrews and BontaAndrews &Bonta, 2003).

Risk-need-responsivity principles and treatment change

The risk principle states that the intensity of treatment should match the clients' risk level: clients with ‘high’, ‘medium’ and ‘low’ levels of risk should receive the corresponding intensities of treatment.

The need principle states that the individual's criminogenic needs (needs that are linked to violence or criminality, such as criminal attitudes, criminal associates etc.) must be assessed, identified and targeted for treatment. Effective correctional treatment should lead to positive changes in the criminogenic needs, resulting in risk reduction. Interventions directed at areas not related to recidivism will not reduce the individual's recidivism risk.

The responsivity principle states that treatment effectiveness can be maximised if treatment delivery can accommodate the clients' idiosyncratic characteristics, such as their cognitive and intellectual abilities, level of motivation and readiness for treatment, cultural background, and so forth. Responsivity refers to the individual's characteristics, which, although not a direct or indirect cause of criminal behaviours, must none the less be taken into account to ensure that treatment and management strategies are effective (see Reference Wong and HareWong & Hare, 2005: p. 5). One of the most daunting responsivity factors in correctional treatment is to treat the unmotivated, non-adherent and treatment-resistant client (i.e. dealing with the general issue of treatment readiness). Many individuals with psychopathy or personality disorder are often unmotivated and treatment resistant, at high risk to recidivate and prone to drop out of treatment prematurely (Reference Ogloff, Wong and GreenwoodOgloff et al, 1990). Thus, paradoxically, those who are in need of treatment the most cannot receive the treatment they need. Assessment of treatment readiness, to ensure that treatment delivery matches the clients' treatment readiness, is therefore essential to reduce treatment drop out, thereby increasing treatment efficacy.

Within this conceptual framework, personality disorder is considered primarily as a responsivity factor. For example, individuals suffering from psychopathy are more likely to be manipulative, lacking in remorse and guilt, self-centred/narcissistic and so forth (Factor 1 characteristics of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R); Reference HareHare, 2003). These interpersonally exploitative and affectively shallow traits are personality traits, and therefore are resistant to change. The behavioural manifestations of these traits and other personality disorder characteristics can significantly interfere with treatment as they impede the formation of a good working alliance with the treatment provider and, therefore, must be appropriately managed for effective correctional treatment and risk reduction to proceed (see Reference Wong and HareWong & Hare, 2005).

Treatment readiness

The Transtheoretical Model of Change or the Stage of Change Model (Reference Prochaska, DiClemente and NorcrossProchaska et al, 1992) addresses the issue of treatment readiness, treatment change and the need to match treatment delivery to client readiness. The model postulates that individuals who modify their problem behaviours progress through a series of five stages: the pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance stages characterised by specific behaviours.

Those in the pre-contemplation stage have neither insight nor intention to change in the foreseeable future. They are often in denial and externalise blame. Those in the contemplation stage are fence-sitters; they acknowledge their problems but have shown no relevant behavioural change: ‘all talk, no walk’. Those in the preparation stage combine intentions to change with relevant behavioural changes to address problems. However, changes tend to be recent and/or quite unstable. Those in the action stage actively modify their behaviours, attitudes and environment to address their problems; overt behavioural changes are made, commitments followed through and energies expended to change. In the maintenance stage, relapse prevention techniques are used to consolidate, strengthen and generalise the gains made in the action stage.

In progressing through the stages, positive changes become more stable, internalised and sustainable. However, treatment interventions effective for one stage may not be effective or may even be counter-productive for some, at other stages. Lapses or cycling through the stages is considered to be a rule rather than an exception. For example, those in the pre-contemplative stage should be provided with treatment engagement activities such as motivational interviewing (Reference Miller and RollnickMiller & Rollnick, 1991). Action stage activities such as skill training (e.g. assertiveness training), although appropriate in general for those in the preparation and action stages, are inappropriate for those in the pre-contemplation stage. Prematurely putting unmotivated clients in action-oriented interventions may lead to increased resistance and treatment drop out. Assessment of the client's treatment readiness, therefore, is critically important in treating resistant clients such as those with psychopathy or personality disorder.

Treatment is a process of change. The primary goal of correctional treatment is to bring about positive changes in criminogenic needs leading to risk reduction. Treatment changes must be assessed objectively and systematically to determine the amount of risk reduced. Assessment and treatment must be closely integrated: assessments of the clients' risk, need and responsivity should inform treatment providers of who to treat (risk principle), what to treat (need principle) and how to deliver treatment, in particular to treatment-resistant clients (responsivity principle). Clinicians who provide correctional treatment require the appropriate tools to assess risk, needs, responsivity and treatment readiness, and to measure treatment change.

Assessment to inform treatment

Assessing risk-need-responsivity and treatment change

Many forensic assessment tools are designed primarily for predicting recidivism not complementing treatment. For example, the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG; Reference Quinsey, Harris and RiceQuinsey et al, 1998) and the Static-99 (Reference Hanson and ThorntonHanson & Thornton, 1999) are designed to predict non-sexual and sexual recidivism respectively. Since these tools use mainly static (unchangeable) predictors, such as criminal history and early behavioural problems, they can predict risk but they cannot assess criminogenic need or responsivity, nor can they measure change in risk. Douglas & Skeem (Reference Douglas and Skeem2005) suggest that development of risk assessment tools with dynamic variables is the next challenge in the field of forensic assessment.

Some assessment tools, such as the Level of Service Inventory (LSI-R; Reference Andrews and BontaAndrews & Bonta, 1995) are designed to assess risk and needs by incorporating changeable or criminogenic need (dynamic risk) variables together with static variables. The LSI-R uses ten domains to assess risk and need; these include criminal history, education and employment, financial resources, etc. This tool provides useful information on the client's risk and need but it does not assess the key responsivity issue of treatment readiness. It is also unclear how to link the amount of change observed in treatment with changes in the dynamic need variables (i.e. what behaviours observed in treatment should one use to indicate changes in these domains). For example, within the LSI-R, the financial and employment domain can be measured if the offender was recently employed in the community. However, it is difficult to assess changes in the domain if the individual has been incarcerated for a long time.

The Violence Risk Scale

The VRS (Reference Wong and GordonWong & Gordon, 2006) is designed to integrate the assessment of risk, need, responsivity and treatment change into a single tool. It assesses the clients' level of violence risk, identifies treatment targets linked to violence, assesses the clients' readiness for change and their post-treatment improvements on the treatment targets. Treatment improvement or lack thereof is linked to quantitative changes in violence risk.

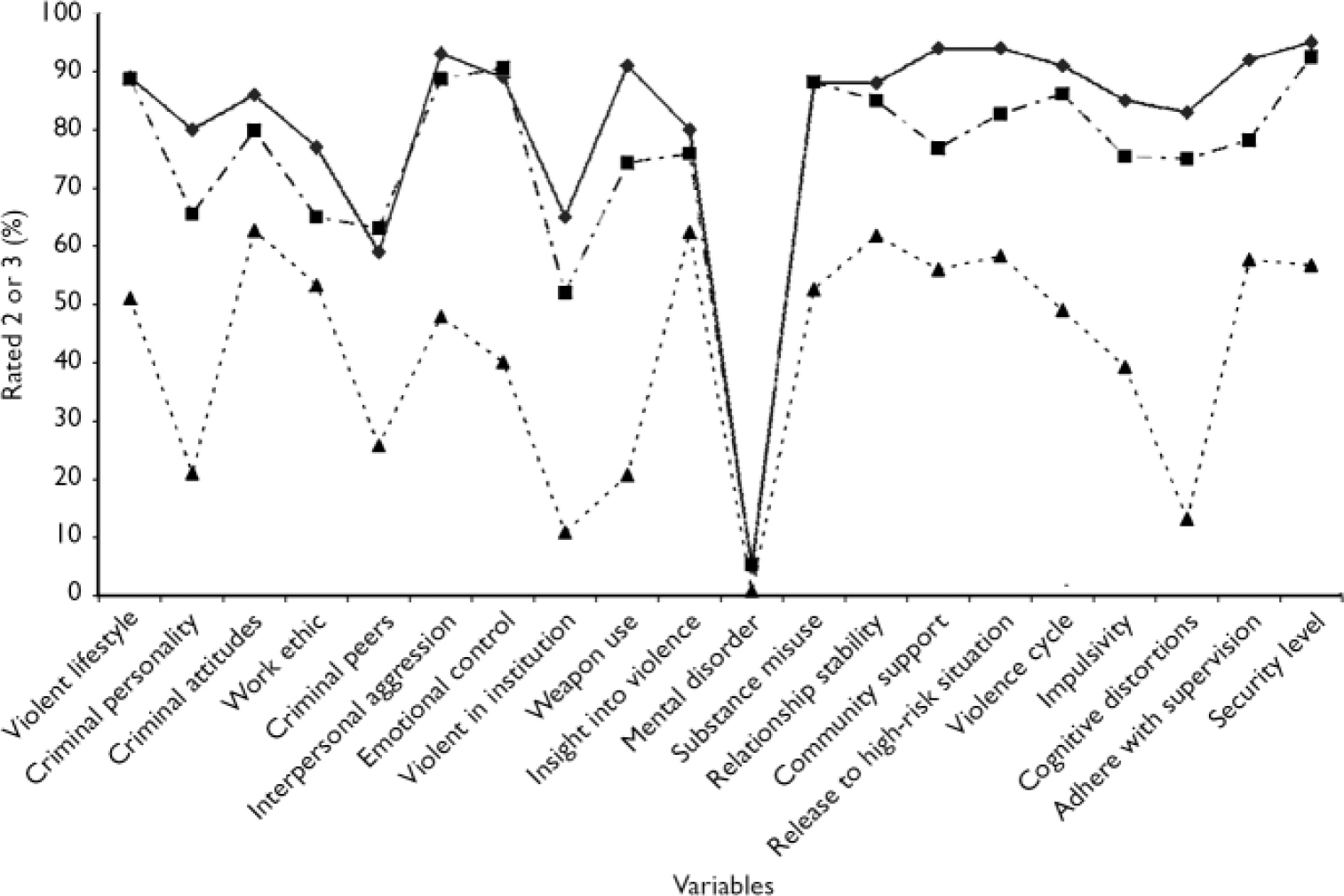

The VRS uses 6 static and 20 dynamic variables derived primarily from and underpinned by the theory of the psychology of criminal conduct and the risk, need and responsivity principles (Reference Andrews and BontaAndrews& Bonta, 2003; see Fig. 1 for VRS dynamic variables). The linkage between the VRS and the principles of effective correctional treatment is by design such that assessment and treatment are closely integrated theoretically. The VRS static and dynamic variables are rated on a four-point scale (0, 1, 2 or 3), based on a careful review of file information and a semi-structured interview. The VRS static variables can predict general and violent recidivism, but remain unchanged with treatment. Higher ratings on the static variables indicate worse ‘track records’ of dysfunctional and antisocial behaviour. The dynamic variables, such as interpersonal aggression and criminal attitudes, are changeable risk predictors; they can be used as treatment targets and can measure changes in risk. Higher ratings (2 or 3) on dynamic variables indicate that the variables in question are closely linked to violence and are appropriate targets for treatment (need principle). The sum of the ratings of the static and dynamic variables reflects the client's level of violence risk;the higher the score, the higher the risk. In selecting clients for treatment, those with higher VRS scores should be appropriate candidates for higher intensity intervention (risk principle). The VRS can also be used as a stand alone measure to assess a client's current risk of violence.

For individuals identified for treatment, the VRS also uses a scheme based on a modified Transtheoretical Model of Change (Reference Prochaska, DiClemente and NorcrossProchaska et al, 1992). Each dynamic variable identified as a treatment target (ratings of 2 or 3) is also assessed to determine the client's stage of change (readiness for treatment). The operationalisations of the various stages of change (except pre-contemplation) are designed to measure the extent to which any newly acquired positive attitudes and coping skills are stable, sustainable and generalisable. Progression in treatment from a less advanced to a more advanced stage of change for each treatment target is an indication of improvement, which should lead to risk reduction in that treatment target. The VRS translates the progress from one stage to the next stage into a quantitative risk reduction of 0.5. The only exception is progress from pre-contemplation to contemplation stage, which carries no risk reduction since those in the contemplation stage only ‘talk the talk’ but have not yet ‘walked the talk’ (i.e. they have shown no relevant behavioural change). Positive changes during the treatment programme are reflected as risk reduction measured by the VRS, in other words, integrating treatment change with risk reduction. The pre-treatment risk level (pre-treatment VRS scores) minus the total risk reduction score is a measure of the client's overall post-treatment risk level. Rating of the VRS variables, the stages of change and the computation of risk scores are provided in detail in the VRS manual (see Reference Wong and GordonWong & Gordon, 1999-2003).

Fig. 1 Risk profile of 20 Violence Risk Scale dynamic variables for offenders with high psychopathy (—♦—), those in the Aggressive Behaviour Control Programme (–·▪·–) and a random sample of offenders (--▾--)

In addition, according to the Transtheoretical Model of Change, the client's prototypical behaviours at each stage of change should be matched with appropriate intervention: the responsivity principle. As such, assessment of the client's stage of change also identifies the most appropriate therapeutic approach to take. A brief summary of therapist tasks that correspond to each stage of change follows.

Pre-contemplation. The therapist should: focus on developing a working alliance, enhancing motivation for change and engagement in treatment;raise doubts and create dissonance regarding the client's current functioning and his hopes of achieving future goals; use cost-benefit analyses to highlight the cost of criminal behaviour.

Contemplation. The therapist should: tip decisional balance; evoke reasons to change in order to reduce dissonance; strengthen the client's confidence to effect change (i.e. increase self-efficacy).

Preparation. The therapist should assist the client in: determining the best course of action to change; setting and achieving shorter-term behavioural goals that are planned, observable, measurable and relevant; highlighting successes and emphasising change potential.

Action. This is the main skill-teaching and skill-building phase of treatment. The therapist should assist the client in strengthening skills through overpractice and reinforce client's self-efficacy in problem-solving and achieving treatment goals.

Maintenance. The therapist should: assist and encourage the client to practice and generalise learned skills to new and challenging situations by providing access to such situations; identify strategies and interventions to prevent lapses and relapses. Obviously, strengthening and reinforcing the client's self-efficacy is important whenever the client takes steps to make changes, regardless of the stage of change.

Integration of assessment and treatment of violence-prone offenders

We will describe the VRP (Reference Gordon and WongGordon &Wong, 2000; Wong, Reference Wong2000a ,Reference Wong b ), a risk reduction focused correctional treatment programme for violence prone forensic clients, to illustrate further the integration of treatment and assessment approaches. The design of the VRP is also based on the theory of criminal conduct, the risk-need-responsivity principles and a modified Transtheoretical Model of Change. An integral part of the VRP is the VRS. Treatment services are delivered using a three-phase model described below.

The objectives of the VRP are to reduce the frequency and intensity of violence by first challenging antisocial beliefs, attitudes, schemas and behaviours that support the use of violence and second, assisting programme participants to acquire appropriate skills that can reduce the risk of violence, as well as developing self-efficacy and confidence in using the skills. The VRP is designed to address the treatment needs of high-risk violence prone clients, in particular those who are non-adherent, unmotivated and resistant to treatment. The programme, although structured and goal-oriented, is flexible enough to accommodate the heterogeneity of criminogenic needs and responsivity often found in this client group.

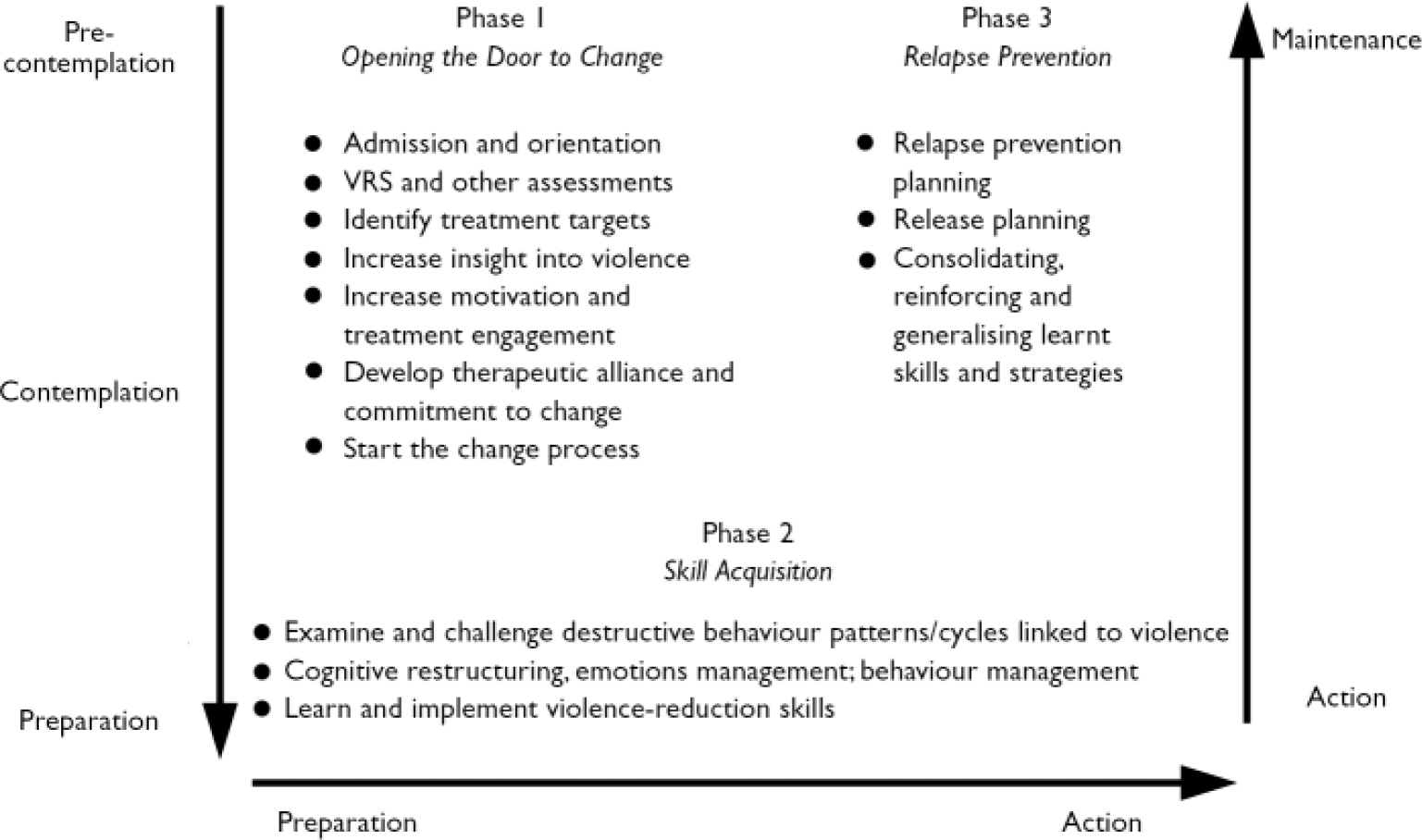

The programme uses cognitive-behavioural therapeutic approaches and social learning principles within a relapse prevention framework to assist participants to make changes and learn new behaviours. It is recognised that learning takes place incrementally (i.e. in small steps) and reinforcement of small incremental improvements is the key. The delivery of the VRP is structured within a three-phase model of treatment delivery (Reference Gordon and WongGordon & Wong, 2000; see Fig. 2). In each of the three phases, participants and those delivering treatment have different tasks and objectives. Phase 1 focuses on helping the client develop insight into past patterns of violence, on identifying treatment targets and on developing therapeutic or working alliance. Motivational interviewing techniques, which should be used throughout the programme, are particularly important in phase 1 and are essential to engage resistant clients in treatment. Phase 2, which is mainly oriented towards action or skill acquisition, focuses on helping participants to acquire relevant skills to restructure negative thoughts, feelings and behaviours associated with violent and destructive patterns. Phase 3 focuses on relapse prevention strategies and the generalisation of skills across situations and to the community. Phase 3 work consists mainly of consolidation, generalisation and maintenance of phase 2 gains.

The client's level of readiness for treatment, assessed as one of the five stages of change by the VRS, can be mapped quite readily onto the three phases (see Fig. 2). The pre-contemplation, contemplation and preparation stages are located in phase 1; the preparation and action stages in phase 2 and the action and maintenance stages in phase 3. The preparation stage is located on both phase 1 and 2 and the action stage on both phase 2 and 3 to emphasise the continuity and movement of the stages through the different phases. The three-phase model integrates the treatment readiness of the client with the therapeutic approaches of the staff to form a ‘road map’ as guidance for clients and staff throughout the treatment process. Clients are taught the conceptual meaning of the ‘stages’ and ‘phases’ in order to develop a common language of treatment and change among staff and clients.

With a heterogeneous group of clients, treatment progress is not expected to be smooth or uniform; frequent lapses are the norm. Programmes that are highly scripted, with content that has to be delivered in a specific chronological order and time frame, would not have the flexibility to accommodate the varied needs of the clients. Progress in the three-phase model depends upon the achievement of specific phase objectives (see Reference Gordon and WongGordon & Wong, 2000). Lapses (e.g. regression from action to contemplation stage) would signal staff to allocate additional resources and time to work with the client using phase 1 approaches to help re-engagement in treatment and the process of change. On the other hand, those who progress faster can move on without being held back. The three-phase model provides staff and clients with a road map that has both the structure and flexibility essential for the treatment of a heterogeneous and resistant group of clients. Improvements are quantified and measured using the VRS.

Implementation of the VRP

The VRP is designed so that it can be modified and adapted for use by different organisations to serve different client groups. It can also be adjusted to fit local requirements such as length of treatment, staffing complement, resource availability, security level, management approaches and so forth. A number of treatment programmes based on the conceptual framework of the VRP have been implemented in various sites in the UK. A VRP pilot programme at the Woodhill Close Supervision Centre, a super-maximum security prison, has been completed, and was evaluated by an independent evaluation team (see Reference Fylan and ClarkeFylan & Clarke, 2006). The objectives of this 7-month VRP pilot programme were to reduce the frequency and intensity of violence of very high-risk and violence-prone prisoners, all of whom had committed homicides while incarcerated. In addition, one of the expected outcomes was that by participating in the VRP, the behaviours of the prisoners would improve to the extent that they could be re-integrated into other mainstream prisons or custodial settings. The results of the evaluation should indicate the feasibility of implementing the VRP programme in a super-maximum security prison.

Another programme that is conceptually similar to the VRP and has been in operation for over a decade is the Aggressive Behaviour Control (ABC) Programme at the Regional Psychiatric Centre, a secure forensic in-patient facility within the Correctional Service of Canada. Both S.W. and A.G. have been actively involved for many years in the development and modification of the ABC Programme. The design of the ABC programme is similar to that of the VRP; both utilise the three-phase treatment model, adhere to the risk-need-responsivity principles and utilise a cognitive-behavioural therapeutic approach. The design of the ABC programme has to accommodate local requirements such as programme length, staffing complements, resource allocation and management requirements. The ABC programme is about 6-8 months long and, similar to the VRP, is designed for clients that have serious histories of violence, have not had success in past treatment attempts, may belong to gangs and often have significant institutional problems such as episodes of serious violence. Criminogenic factors are addressed in offence cycle groups, psychoeductional groups and individual therapy. Services to address issues of education, work and life skills, relationships with significant others, family dynamics, community support and early abuse are provided where appropriate. Like the VRP, the ABC programme attends to client responsivity such as personality disorders, cognitive and language abilities, cultural background, treatment readiness, and so forth. At the end of the programme, each participant is required to develop a relapse prevention plan that delineates in detail interventions that can be used to mitigate risks of recidivism.

Fig. 2 Three-phase treatment delivery model.

METHOD

Participants

Participants included 203 male federal offenders (serving a sentence of⩾2 years), most of whom were referred by the other federal penitentiaries in the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba for treatment in the ABC programme over a period of about 7 years (1996-2003). The sample was selected as they were all administered the VRS as a part of the assessment process and they all completed the ABC programme. They were also given a psychiatric diagnosis on or shortly after admission. The sample demographics are given in Table 1.

Table 1 Demographics of male federal offenders referred for treatment over the period 1996–2003 1

| Prior convictions, n: mean (s.d.) | |||

| Violent | 5.37 | (3.26) | |

| Non-violent | 18.24 | (12.75) | |

| Sexual | 0.17 | (0.52) | |

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | |||

| At first conviction | 17.60 | (4.10) | |

| At index sentence | 25.45 | (6.26) | |

| At sentence expiry | 33.08 | (7.26) | |

| Educational level, years 2 | 9.52 | (2.36) | |

| Marital status, % 3 | |||

| Single | 52.2 | ||

| Married/common-law | 29.3 | ||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 18.5 |

1. n=203 unless otherwise indicated

2. n=64

3. n=92

Assessment of risk, need and responsivity

About 1 month after admission, participants were rated using the VRS by staff trained by A.G. Ratings included the static and the dynamic variables and the stages of change for each dynamic variable identified as a treatment target, plus an overall stage of change rating reflecting the predominant stage of change of all the dynamic variables. Most participants tended to show a predominant stage of change for most of the problem areas, but there are exceptions.

RESULTS

Risk ratings

The mean VRS total score (static plus dynamic variables) for the sample is 55.23 (s.d.=10.70), which is almost 1.5 s.d. above the mean (35.49;s.d.=14.97, n=652; t=20.76; P<0.00001) of a sample of randomly selected federal penitentiary inmates from the same three provinces (random sample). In a separate study (Reference Wong and GordonWong & Gordon, 2006), it was found that those who scored 55-60 on the VRS had about 55% and 69% likelihood of recidivating violently and generally, respectively, after 3-year follow-up compared with 25% and 49% for those that scored 35-40, that is, the random sample. Participants in the programme are more than twice as likely to recidivate violently than the general offender sample and have very extensive criminal records (Table 1), with a mean of almost 24 convictions accumulated in an average 8-year criminal career, five of which are violent convictions. The treatment sample comprised violence-prone offenders and it is appropriate to provide them with high-intensity risk reduction treatment.

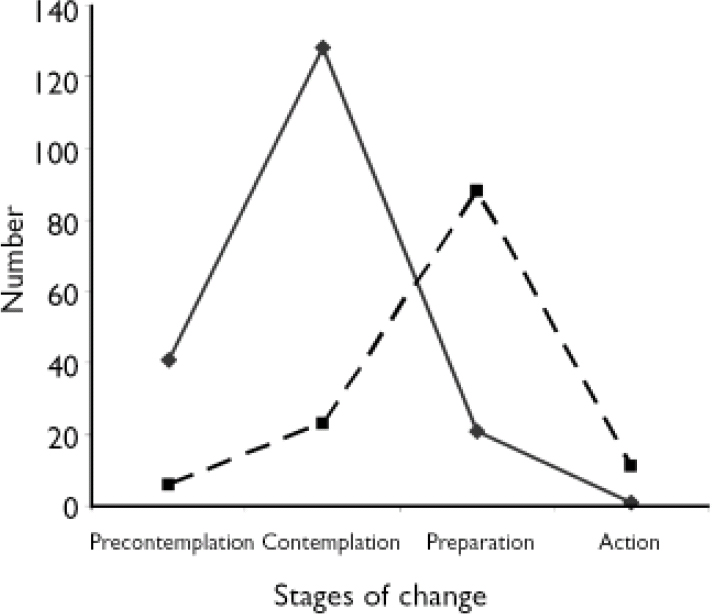

Fig. 3 Stages of change before (—♦—) and after (---▪---) treatment

Criminogenic needs or dynamic risk ratings

The VRS dynamic variables rated 2 or 3 are closely linked to violence and can be considered as problem areas or treatment targets. One way to describe the prevalence of problems in the sample is to show the percentages of the sample that rated 2 or 3 on each of the 20 dynamic variables to give a ‘dynamic risk profile’ (Reference Wong, Burt, Yuille and HerveWong & Burt, 2007; see Fig. 1). As a comparison, the dynamic risk profiles of a group with psychopathy (mean PCL-R score=28.2, s.d.=2.7; mean VRS score=58.4, s.d.=7.7, n=65; Reference Wong, Burt, Yuille and HerveWong & Burt, 2007) and the random sample are also presented in Fig. 1.

In the ABC sample, all but one of the dynamic variables had prevalence rates of 50% and above, with most variables between 70 and 90% (a very high prevalence of criminogenic problems). The one variable that has very low prevalence is mental disorder, which assesses the presence of associations between Axis I major mental illnesses and violence (not the mere presence of mental illness). The ABC programme Footnote 1 is not designed primarily to treat individuals whose violence is the result of Axis I major mental illnesses. Not surprisingly, for the group with psychopathy, 16 out of 20 variables had prevalence rates of 80%. The overall dynamic risk profile of the ABC sample is slightly lower than that of the group with high psychopathy but still indicates a high-risk, high-need profile. The ABC group profile is much higher than the random group on all but the mental disorder variable, further confirming that the ABC group has many more problems and therefore is much higher risk than the average offender population.

Treatment readiness

The number of participants in the five stages of change (Reference LewisLewis, 2004) from a subsample of 191 are shown in Fig 3. The post-treatment stage of change is also presented to show the advancement in the stages of change as a function of treatment (n=128). Most participants started treatment at the contemplation stage and progressed to the preparation stage post-treatment. None was at the maintenance stage and only a few were in the action stage at the end of treatment.

Psychiatric diagnosis

Of the 203 participants, 190 (94%) and 184 (90%) received at least one DSM-III/IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1987, 1994) Axis I and Axis II diagnosis respectively. Missing data and no diagnosis accounted for the remainder. Substance use disorders accounted for 89% of the Axis I diagnoses and 91% of Axis II diagnoses were antisocial personality disorder. Schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders and mood disorders accounted for less than 6% of the Axis I diagnoses. Most of the sample consisted of offenders with antisocial personality disorder and a very high incidence of substance use. The results are in line with ratings of the VRS variables: about 65% were rated 2 or 3 on the criminal personality variable (PCL-R factor 1 psychopathic personality traits), and 90% on the substance abuse variable. It is well established that a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder overestimates the incidence of psychopathic traits. The criteria for admission for the ABC programme are not based on whether or not the individual has a personality disorder, but among violence-prone and high-need forensic clients, the prevalence of such a diagnosis is expected to be high.

Treatment outcome

The efficacy of the correctional programmes using the VRP approach in reducing recidivism and institutional misconduct in high-risk, violence-prone and difficult-to-manage offenders was assessed in four recent studies (Wong et al, Reference Wong, Van der Veen and Leis2005, Reference Wong, Witte and Gordon2006; Reference Di Placido, Simon and WitteDi Placido et al, 2006; Reference Fylan and ClarkeFylan & Clarke, 2006). Incarcerated offenders with gang affiliations present special challenges to correctional authorities. Many of these gang members have extensive histories of violence before incarceration and while incarcerated they are often responsible for a large proportion of institutional violence and management problems (Reference SheldonSheldon, 1991; Reference KnoxKnox, 2000; Reference Gaes, Wallace and GilmanGaes et al, 2002). The ABC programme had provided treatment to many gang members who fit the prototypical profile of the high-risk, high-need and difficult-to-manage offender group. Recently, a carefully controlled study was carried out to compare treatment outcomes (about 24 months follow-up) of a treated gang group with a matched control gang group who had received little or no treatment. For members of both groups the mean age was about 24 years and they had about 20 criminal convictions before treatment; they were serving, on average, 6-year sentences. The mean length of treatment was about 8 months. The treated gang group had a significantly lower incidence of recidivism, significantly less major institutional misconduct and committed significantly less serious violent offences than the matched controls (Reference Di Placido, Simon and WitteDi Placido et al, 2006). The results suggested that, for a group of high-risk, high-need violent gang members, treatment in a risk reduction focus institutional programme, such as the ABC, can reduce both institutional misconduct and violence after release to the community.

Offenders who have committed serious violence acts such as murder or hostage-taking while incarcerated are often housed under extremely restrictive regimes in super-maximum security facilities. Deciding when they are safe enough to be transferred back to regular prisons is difficult, but prison authorities often are required to reintegrate them into the general offender population. Participation in the ABC treatment programme has been used as a transitional strategy to facilitate their reintegration. Within the ABC programme, both their security requirements and treatment needs can be adequately met. Results of an evaluation of such a strategy indicated that over 80% of the offenders (n=31) admitted from the super-maximum institution, the Special Handling Unit in Canada, were successfully reintegrated into a lower-security facility without relapsing (returning to the super-maximum institution) within a 20-month follow-up. They also have significantly lower institutional offence rates after reintegration than before (Reference Wong, Van der Veen and LeisWong et al, 2005).

Offenders with high levels of psychopathy were also treated in the ABC programmes (mean length of treatment about 8 months), with the primary treatment objective of reducing their risk for reoffending rather than resolving their personality disorders. In a recent treatment outcome study (Reference Wong, Witte and GordonWong et al, 2006), 34 treated offenders with significant levels of psychopathy were matched with 34 untreated controls (mean PCL-R ratings of 28.6 and 28.0 respectively). The two groups were also matched for age (38.5 and 37.9 respectively), past criminal history (17.8 and 19.5 prior convictions respectively), and follow-up time (both 7.4 years). Their VRS scores were 51.1 and 55.2 respectively (P=NS). They were high-risk, high-need and violence-prone offenders with high psychopathy scores. On follow-up, the treated and matched group did not differ in the number of violent, and non-violent re-convictions and sentencing dates, or the time to first re-conviction. However, the treated group had a significantly less violent pattern of reoffence as indicated by the significantly shorter aggregated sentences they received (27.7 v. 56.4 months respectively, P<0.05). Sentence length has been shown to be a reasonable proxy for the level of violence or severity of offending (Reference CampbellCampbell, 1993; Reference BélangerBélanger, 2001; Reference Di Placido, Simon and WitteDi Placido et al, 2006). Treatment may not prevent offenders with significant levels of psychopathy from reoffending, or even decrease the frequency of reoffending, but it did appear to reduce the degree of violence or severity of reoffending - a harm reduction effect. For offenders with fairly high PCL-R scores, 8 months of treatment is probably not long enough to produce the optimal outcome. Despite the less than optimal treatment ‘dosage’, the results support the contention that risk reduction correctional programmes that use the VRP approach can reduce violent recidivism in forensic clients with high levels of psychopathy.

Description and treatment outcome of the VRP pilot programme

The VRP pilot programme is a major part of an overall violence reduction strategy designed for the close supervision centres ‘to reduce physical, emotional and organisational violence, and to provide [prisoners with] an integrated care package… which addresses their physical and mental health needs’ (Reference Fylan and ClarkeFylan & Clarke, 2006: p. 6). The other components of the strategy are to provide high-standard mental healthcare to prisoners in close supervision centres and appropriate training to staff to equip them with the necessary skills to manage and care for violence-prone prisoners.

The programme participants were four prisoners with a mean age of 32 years (range 25-36) who spent a mean of 5.25 years (range 1.5-9.0) in the close supervision centre. Three of them murdered a fellow offender and one murdered a member of the prison staff while they were incarcerated or in custody. All had dysfunctional or difficult childhoods, long histories of serious violent criminal behaviours, substance misuse, and obviously, very serious institutional violence. One had symptoms of borderline personality disorder and another paranoid schizophrenia. The four treated prisoners were compared with two untreated prisoners (waiting list controls) who were 41 and 24 years of age and spent 8 and 3 years in close supervision centres respectively and had very similar social, criminological and institutional behaviour backgrounds. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews (using questionnaires developed for the purpose) with key staff and the prisoners, behavioural monitoring using Likert-type rating scales for target behaviours, scoring of the VRS and systematically collected behavioural observation narratives. Data were obtained during and after the programme when prisoners were transferred to a new but less supportive environment to test the generalisation of any newly acquired behaviour.

The small sample size precluded quantitative data analyses. We provide a synopsis of the findings taken from the summaries of the report (Reference Fylan and ClarkeFylan & Clarke, 2006; pp. 3 and 47). The authors of the report noted that ‘Data from interviews with staff involved with the program indicate the VRP has produced a marked improvement in prisoner behaviour. While the improvement staff perceived may in part be influenced by their greater insight into the prisoners and their behaviour, there is some independent evidence that violent behaviour has decreased and inter-personal skills have improved. There is also evidence, gained from interviews with staff and prisoners that better insight into prisoner behaviour - on the part of both prisoners and staff - has resulted in more effective management of the risk of violence. Prisoners are better able to talk to staff about their emotional reactions and to avoid high-risk situations, and staff are better able to avoid high-risk situations for individual prisoners, and to better interpret and anticipate prisoners’ behaviour. Data collected from the prisoners' new locations provide evidence that the skills developed during the VRP have been maintained, and that the changes achieved have been maintained in less supportive environments…. all three of the prisoners who agreed to be interviewed post-program report that they continue using the skills they developed on the VRP and that it has enabled them to better control their actions and to reduce the frequency and intensity of violent incidents.'

The authors further noted that ‘The VRP is potentially suitable for all prisoners, although their level of motivation to engage with the programme should be sufficiently high’, thus for some prisoners education/orientation and motivational enhancement strategies should be provided before the programme. Staff do not believe that the VRP would discriminate against any prisoner groups. There is no evidence that (close supervision centre) staff at Woodhill have higher workplace stressors than those at the other (close supervision centre) sites. ‘All four prisoners on the pilot have progressed from or within the (Close Supervision Centre)’ to a less secure environment which has provided further support for the findings of Wong et al (Reference Wong, Van der Veen and Leis2005).

Overall, the results suggest that the VRP is efficacious in reducing the frequency and intensity of violent acts by prisoners, and in assisting the reintegration of these prisoners into mainstream custodial settings. The programme staff also felt that they were better equipped to provide more effective management of the risk of violence through staff training, input from the mental health team, and interactions with prisoners within the framework of the VRP. The caveats in the interpretation of the results are the small sample size, the design of the study which limits causal inferences and the lack of statistical testing of the data.

DISCUSSION

We suggested that the assessment and treatment of violence-prone forensic clients for the purpose of risk reduction should be theoretically based, empirically driven and closely integrated. Assessment should tell treatment providers about the ‘who’, ‘what’ and ‘how’ of treatment. The goal of treatment is change, and how much positive change has occurred in treatment should be assessed and translated into a measure of risk reduction. Assessment and treatment should be closely integrated. Establishing a clear and psychologically relevant common language between assessment and treatment approaches as well as between staff and clients should increase the chances of achieving the stated goal of risk reduction. The VRP and VRS were described to illustrate how such integration and the use of a common language (i.e. having a common theoretical underpinning) can be achieved in practice and this was illustrated by reference to the existing programmes.

Risk

The risk level of the ABC sample indicated a probability of violent recidivism (55%) which is more than two times that of the average offender sample. Although the admission criteria for the ABC programme are not based on VRS scores, the type of clients admitted to the programme did clearly satisfy the violence-prone or ‘high risk’ admission criteria.

Criminogenic need or dynamic risk

The criminogenic need or dynamic risk profile of the ABC sample clearly showed that the sample has multiple problem areas linked to violence, and participation in a high-intensity violence-reduction programme would be appropriate. The group had only slightly fewer problems than a group with high levels of psychopathy but many more problems (or higher risk) than a randomly selected group of offenders. The group profile is also useful for planning the treatment programme. Managers and lead clinicians can use the information to decide what types of programmes are needed to address the existing criminogenic needs of a certain population. Overall treatment planning can then be undertaken and resources allocated based on the prevalence of problem areas in the samples of interest.

A similar profile could be constructed for the individual through a comprehensive clinical risk assessment. The ratings (0, 1, 2 or 3) of the 20 dynamic variables, rather than percentages, can be displayed as the individuals' dynamic risk or problem-strength profile. Ratings of 0 and, to some extent, 1 are the individual's strengths, and ratings of 2 and 3 are problem/treatment targets. The profile can inform staff of the presence and seriousness of the individual's problems. Further in-depth investigation may be warranted depending on the presenting problems. Risk reduction interventions could then be formulated based on the individual's risk profile and stage of change. The level of risk after attending a treatment programme can be re-assessed and similarly presented. The profile is useful for individual treatment planning. Offenders who are prone to violence and those with psychopathy share many similar problems and risk reduction treatment for both groups should be quite similar. However, management strategies and treatment ‘dosage’ would be different (see Reference Wong and HareWong & Hare, 2005; Reference Wong, Burt, Yuille and HerveWong & Burt, 2007).

Treatment readiness

The majority of the ABC sample was at the contemplation stage on admission to the programme, followed by those in the pre-contemplation stage and the preparation stage, but none in the action or maintenance stage. The majority admitted to having problems but had not done anything about it yet - contemplation. The result is not unexpected as all ABC participants were admitted on a voluntary basis and would have, at least, ‘talked the talk’ by expressing a desire to change. Those in action or maintenance stages do not need such a high-intensity programme. The results suggest that the staff would need to use a lot of phase 1 treatment approaches, such as motivational interviewing and other treatment engagement techniques to try to encourage and motivate these clients to start taking steps to move forward. Even more so, for the smaller group in the pre-contemplation stage, the first step for staff would be to assist the client in acknowledging their problems and considering the need for treatment. As an illustration, at the end of treatment, the majority of clients moved to the preparation stage, a substantial advance given the relatively short duration of treatment.

Treatment outcome

The results of four outcome studies, three with comparison groups, are encouraging. Both the VRP pilot programme and the ABC programme, which is similar in treatment philosophy and design to the VRP, appeared to be effective in reducing the risk and/or the severity of violent recidivism and/or institutional misconduct among perhaps some of the most challenging client groups: violent gang members, prisoners incarcerated in super-maximum security prisons and those with high levels of psychopathy. For those with psychopathy, and probably other high-risk violent offenders, the harm reduction treatment outcome is not unexpected.

In providing treatment to those with psychopathy and other very high-risk, high-need individuals, treatment providers should be realistic in their expectations of changes during treatment and outcomes after treatment. Wong& Hare (Reference Wong and Hare2005: p. 9) wrote in the Guidelines for a Psychopathy Treatment Program:

‘…it would be a mistake to believe that…individuals with a history of predatory behavior will become model citizens. Saul will not become Paul, to use a biblical analogy. About the best we can hope for is that psychopaths who have gone through the…[treatment program] will be significantly (in a practical as well as statistical sense) less prone to engage in violent behavior than they were before the program. Still, even modest reductions in the use of aggression and violence by psychopaths would be of enormous benefit to society'.

Statistical analyses of treatment outcomes (criterion variables) using measures of changes in rates of reoffence or time to first reoffence (e.g. using survival analysis) may not be sensitive enough to detect some harm reduction effects, that is, reduction in severity of reoffending.

With appropriate modifications, the VRP could be used for the treatment of sex offenders and young offenders, as well as those with Axis I major mental illnesses and co-occurrence of significant antisocial behaviours (personality disorders). Acute symptoms of mental illness have to be appropriately stabilised and staff need to be competent and prepared to deal with the expected periodic decompensations. However, those who are mentally ill and vulnerable should be treated in a separate treatment environment.

The development of the VRP and the VRS is an attempt to integrate correctional treatment and risk assessment for the purpose of providing theoretically derived and empirically driven assessment and interventions to violence-prone and treatment-resistant clients. The VRP and VRS are complementary: each providing the other with information required to fulfill the tasks of assessment, treatment and risk reduction.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.