Implications

Kisspeptin has emerged as a key regulator of reproductive function in pigs. It acts within the central nervous system to stimulate the secretion of reproductive hormones from the anterior pituitary gland that promote the initiation and maintenance of reproductive cycles. Kisspeptin holds tremendous promise to provide new methods to control reproduction and fertility in pork production; however, research in swine has fallen behind that of other livestock species. Given the unique differences in the regulation of reproduction between livestock species, pig-specific research is needed to fully capture the benefits that kisspeptin can bring to improving reproduction in pigs.

Introduction

Reproductive failure is the number one reason for culling gilts and sows (Knauer et al., Reference Knauer, Stalder, Karriker, Johnson and Layman2006; Tummaruk et al., Reference Tummaruk, Kesdangsakonwut and Kunavongkrit2009). Approximately 30% of replacement gilts never farrow (Stancic et al., Reference Stancic, Stancic, Bozic, Anderson, Harvey and Gvozdic2011). A common reason for this is that gilts fail to become cyclic or their cyclicity is delayed beyond acceptable ages (Saito et al., Reference Saito, Sasaki and Koketsu2011). Initiation of puberty is dependent upon the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. In general, pubertal development culminates with the activation of high-frequency pulses of LH (Diekman et al., Reference Diekman, Trout and Anderson1983; Lutz et al., Reference Lutz, Rampacek, Kraeling and Pinkert1984; Camous et al., Reference Camous, Prunier and Pelletier1985) that are driven by cyclic increases in the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus (Lutz et al., Reference Lutz, Rampacek and Kraeling1985; Kraeling and Barb, Reference Kraeling and Barb1990). Inadequate gonadotropin secretion also results in pubertal failure and contributes to prolonged wean to oestrus intervals in postpartum sows (Edwards and Foxcroft, Reference Edwards and Foxcroft1983). Moreover, insufficient gonadotropin secretion can underlie seasonal dips in cyclicity of gilts and sows (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Britt and Cox1986, Barb et al., Reference Barb, Estienne, Kraeling, Marple, Rampacek, Rahe and Sartin1991). Even though it has been known for many decades that dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis contributes to reproductive inefficiency of pigs that results in considerable financial loss, little progress has been made in understanding the regulation of this key physiological process. In the last decade and a half, kisspeptin has emerged as being critically important in controlling gonadotropin secretion and is central to the effects of nutrition, disease, stress and season on gonadotropin secretion in laboratory and livestock species. The intent of this review is to examine the current state of knowledge regarding kisspeptin and regulation of reproduction in the pig with reference to other species where information in the pig may be lacking.

Kisspeptin and reproduction

Kisspeptin and central regulation of the reproductive neurosecretory axis

Kisspeptin is the peptide product of the KISS1 gene (Kotani et al., Reference Kotani, Detheux, Vandenbogaerde, Communi, Vanderwinden, Le Poul, Brezillon, Tyldesley, Suarez-Huerta, Vandeput, Blanpain, Schiffmann, Vassart and Parmentier2001; Ohtaki et al., Reference Ohtaki, Shintani, Honda, Matsumoto, Hori, Kanehashi, Terao, Kumano, Takatsu, Masuda, Ishibashi, Watanabe, Asada, Yamada, Suenaga, Kitada, Usuki, Kurokawa, Onda, Nishimura and Fujino2001). Synthesized as a pre-prohormone, kisspeptin is proteolytically cleaved to produce a series of peptides ranging from 10 to 54 amino acids in length. These kisspeptins share complete homology at the c-terminus and retain full biological activity. The kisspeptin receptor is a G-protein-coupled receptor that was found to be critical for the initiation of puberty in lab animals (Seminara et al., Reference Seminara, Messager, Chatzidaki, Thresher, Acierno, Shagoury, Bo-Abbas, Kuohung, Schwinof, Hendrick, Zahn, Dixon, Kaiser, Slaugenhaupt, Gusella, O’Rahilly, Carlton, Crowley, Aparicio and Colledge2003). Kisspeptin and kisspeptin receptor gene expression are hormonally regulated (Navarro et al., Reference Navarro, Castellano, Fernandez-Fernandez, Barreiro, Roa, Sanchez-Criado, Aguilar, Dieguez, Pinilla and Tena-Sempere2004), and early studies revealed that central (intracerebroventricular, ICV) and peripheral (intravenous, IV; subcutaneous, SC) treatment with kisspeptin had potent stimulatory effects on the secretion of gonadotropin hormones in laboratory rodents (Matsui et al., Reference Matsui, Takatsu, Kumano, Matsumoto and Ohtaki2004; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Patterson, Murphy, Smith, Dhillo, Todd, Ghatei and Bloom2004) and nonhuman primates (Shahab et al., Reference Shahab, Mastronardi, Seminara, Crowley, Ojeda and Plant2005). It was subsequently reported that kisspeptin powerfully stimulates gonadotropin secretion, particularly LH secretion, in livestock species, including sheep (Caraty et al., Reference Caraty, Smith, Lomet, Ben Said, Morrissey, Cognie, Doughton, Baril, Briant and Clarke2007a), goats (Hashizume et al., Reference Hashizume, Saito, Sawada, Yaegashi, Ezzat, Sawai and Yamashita2010), cattle (Kadokawa et al., Reference Kadokawa, Matsui, Hayashi, Matsunaga, Kawashima, Shimizu and Miyamoto2008) and horses (Magee et al., Reference Magee, Foradori, Bruemmer, Arreguin-Arevalo, McCue, Handa, Squires and Clay2009). Prepubertal gilts received one of two doses of kisspeptin (10 or 100 μg) injected in to the lateral ventricles of the brain (Lents et al., Reference Lents, Heidorn, Barb and Ford2008). Both kisspeptin treatments produced a robust and immediate surge-like secretion of LH that was sustained for several hours. The 10-μg dose of kisspeptin elevated LH secretion for about 2 h, whereas the 100-μg dose increased LH for the entire 3-h post-injection sampling period. The magnitude of this LH release was one-half to two-thirds that induced by an IV injection of GnRH (100 μg). The 100-μg dose of kisspeptin also stimulated FSH secretion for over 3 h, and this release of FSH was similar in magnitude to that stimulated by GnRH. These results firmly established that kisspeptin is a potent stimulant of LH in the pig. The more potent effect of kisspeptin in stimulating secretion of LH compared with FSH was attributed to the fact that LH secretion is more responsive to GnRH than is FSH. It was concluded that kisspeptin plays a major role in the onset of LH pulses in the pig during puberty.

A substantial body of evidence indicates that the effect of kisspeptin to stimulate LH secretion occurs centrally within the hypothalamus. Kisspeptin receptor is expressed in GnRH neurons of the ovine hypothalamus (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Li, Yap, Shahab, Roseweir, Millar and Clarke2011), and kisspeptin-stimulated secretion of LH in ewes is accompanied by a concomitant release of GnRH (Messager et al., Reference Messager, Chatzidaki, Ma, Hendrick, Zahn, Dixon, Thresher, Malinge, Lomet, Carlton, Colledge, Caraty and Aparicio2005; Caraty et al., Reference Caraty, Smith, Lomet, Said, Morrissey, Cognie, Doughton, Baril, Briant and Clarke2007b). Moreover, kisspeptin failed to stimulate LH secretion in ewes treated with neutralizing antibodies to GnRH (Arreguin-Arevalo et al., Reference Arreguin-Arevalo, Lents, Farmerie, Nett and Clay2007), and in ewes in which the hypothalamus had been disconnected from the pituitary to eliminate GnRH input to gonadotroph cells (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Rao, Pereira, Caraty, Millar and Clarke2008b), demonstrating that kisspeptin stimulates LH secretion in a GnRH-dependent manner. Although similar studies have not been reported for pigs, the spatial distribution of kisspeptin expression within the porcine hypothalamus implies kisspeptin regulation of GnRH neurons in the pig as well.

Structural organization of kisspeptin neurons in the hypothalamus

In the central nervous system of rodents, kisspeptin cells are localized primarily in two discrete regions involved in the regulation of gonadotropin secretion, including the anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV) near the preoptic area (POA) and the arcuate nucleus (ARC; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Dungan, Stoll, Gottsch, Braun, Eacker, Clifton and Steiner2005). Livestock do not have a true AVPV similar to that in rodents; rather kisspeptin neurons are organized in the POA and ARC (Franceschini et al., Reference Franceschini, Lomet, Cateau, Delsol, Tillet and Caraty2006). Immunoreactive kisspeptin was localized in these regions to cell bodies and fibres. In the POA of the ewe, kisspeptin immunostaining was observed to extend from the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis to the opening of the preoptic recess into the third ventricle. During sexual maturation in the ewe, messenger RNA (mRNA) for kisspeptin is expressed in the discrete region of the periventricular (PeV) nucleus (Redmond et al., Reference Redmond, Baez-Sandoval, Spell, Spencer, Lents, Williams and Amstalden2011a). Similarly, kisspeptin gene expression is found in the PeV of sexually mature and developing gilts (Tomikawa et al., Reference Tomikawa, Homma, Tajima, Shibata, Inamoto, Takase, Inoue, Ohkura, Uenoyama, Maeda and Tsukamura2010; Ieda et al., Reference Ieda, Uenoyama, Tajima, Nakata, Kano, Naniwa, Watanabe, Minabe, Tomikawa, Inoue, Matsuda, Ohkura, Maeda and Tsukamura2014). This is a similar area as the AVPV in mice and may be important for GnRH secretion controlling ovulation in pigs.

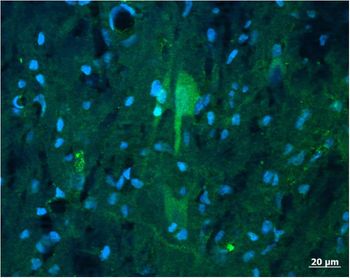

Kisspeptin mRNA is expressed in the medial basal hypothalamus (MBH) of gilts (Thorson et al., Reference Thorson, Heidorn, Ryu, Czaja, Nonneman, Barb, Hausman, Rohrer, Prezotto, McCosh, Wright, White, Freking, Oliver, Hileman and Lents2017) within the ARC (Tomikawa et al., Reference Tomikawa, Homma, Tajima, Shibata, Inamoto, Takase, Inoue, Ohkura, Uenoyama, Maeda and Tsukamura2010). A spatially distinct pattern of kisspeptin expression is seen throughout the ARC of the pig, with the greatest gene expression in the medio-caudal sections (Tomikawa et al., Reference Tomikawa, Homma, Tajima, Shibata, Inamoto, Takase, Inoue, Ohkura, Uenoyama, Maeda and Tsukamura2010; Thorson et al., Reference Thorson, Prezotto, Adams, Petersen, Clapper, Wright, Oliver, Freking, Foote, Berry, Nonneman and Lents2018). This is similar to the ARC distribution of kisspeptin observed in sheep and cattle (Redmond et al., Reference Redmond, Baez-Sandoval, Spell, Spencer, Lents, Williams and Amstalden2011a; Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Alves, Sharpton, Williams and Amstalden2015). The work on localization of kisspeptin within the porcine hypothalamus has thus far been limited to the expression of mRNA for the kisspeptin gene. Reports identifying the spatial distribution of kisspeptin-expressing cells with immunocytochemistry are lacking for pigs. Preliminary data demonstrate that neuronal cell body as well as nerve fibres can be identified within the porcine ARC (Figure 1). It is thus anticipated that the structural organization of kisspeptin neurons within the porcine ARC is similar to other species. Specifically, kisspeptin neurons in the POA act on GnRH cell bodies, whereas kisspeptin neurons in the ARC regulate GnRH terminal axons in the median eminence.

Figure 1 A population of neurons (arrow) positive for kisspeptin (green) and simultaneously counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindolel; blue) to reveal neuronal and glia nuclei were found in the arcuate nucleus of the porcine hypothalamus. The antibody labelled cell body as well as nerve fibres. Image was captured with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 imaging photomicroscope (Carl Zeiss Vision, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a digital camera (Axio Cam MRc) and appropriate filters. The captured image was evaluated with the Axio Vision 4.6 Imaging system. For the preparation of microscopic illustrations, Corel Graphic Suite 11 was used only to adjust brightness, contrast and sharpness. Source: CA Lents, unpublished.

Oestrogen feedback and expression of kisspeptin

Escape from oestrogen negative feedback with advancing age is critical for increased LH secretion in gilts (Berardinelli et al., Reference Berardinelli, Ford, Christenson and Anderson1984; Barb et al., Reference Barb, Kraeling, Rampacek and Estienne2000; Barb et al., Reference Barb, Hausman and Kraeling2010a), but the mechanisms behind this hormonal regulation of reproduction are not understood. Oestrogen receptor is not expressed in GnRH neurons, suggesting that the feedback effects of oestrogen on the GnRH pulse generator are mediated through other afferent neurons. Kisspeptin neurons in sheep express oestrogen receptor alpha (Franceschini et al., Reference Franceschini, Lomet, Cateau, Delsol, Tillet and Caraty2006; Bedenbaugh et al., Reference Bedenbaugh, D’Oliveira, Cardoso, Hileman, Williams and Amstalden2017), and oestrogen receptor signalling in kisspeptin neurons is critical for the timing of puberty in mice (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Acosta-Martinez, Dubois, Wolfe, Radovick, Boehm and Levine2010). Oestrogen was shown to have profound negative effects on the expression of kisspeptin in the ARC of adult ewes (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Clay, Caraty and Clarke2007), demonstrating that hypothalamic expression of kisspeptin is under the influence of gonadal steroids. In prepubertal ewe lambs, the expression of kisspeptin mRNA in the POA, PeV and ARC areas increased with pubertal maturation (Redmond et al., Reference Redmond, Baez-Sandoval, Spell, Spencer, Lents, Williams and Amstalden2011a). The expression of kisspeptin in the ARC was correlated to the age-related increase in LH pulses, suggesting that kisspeptin neurons in this region of the hypothalamus are critical for the pubertal transition in gonadotropin secretion of sheep. This contrasts with the gilt in which the expression of the kisspeptin gene in the PeV region of the hypothalamus was undetectable, by in situ hybridization, during pubertal maturation (from 0 to 5 months of age) (Ieda et al., Reference Ieda, Uenoyama, Tajima, Nakata, Kano, Naniwa, Watanabe, Minabe, Tomikawa, Inoue, Matsuda, Ohkura, Maeda and Tsukamura2014). Robust expression of the kisspeptin gene in the ARC of these gilts was observed, but the ARC expression of kisspeptin did not differ with age or puberty status. This finding was corroborated by a recent report that the expression of kisspeptin gene in the MBH of prepubertal, peripubertal or postpubertal luteal phase gilts did not differ (Thorson et al., Reference Thorson, Heidorn, Ryu, Czaja, Nonneman, Barb, Hausman, Rohrer, Prezotto, McCosh, Wright, White, Freking, Oliver, Hileman and Lents2017). Thus, it appears that the pubertal decrease in sensitivity to oestrogen negative feedback in the gilt does not involve changing kisspeptin gene expression. However, it is noted that the gene expression for tachykinin 3 (TAC3), which encodes neurokinin B, and the tachykinin 3 receptor (TAC3R) gene is upregulated in the MBH of peripubertal gilts compared to prepubertal gilts (Thorson et al., Reference Thorson, Heidorn, Ryu, Czaja, Nonneman, Barb, Hausman, Rohrer, Prezotto, McCosh, Wright, White, Freking, Oliver, Hileman and Lents2017). Given the important role of neurokinin B, acting through its receptor, to stimulate kisspeptin and LH secretion (Nestor et al., Reference Nestor, Briscoe, Davis, Valent, Goodman and Hileman2012; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Hileman, Nestor, Porter, Connors, Hardy, Millar, Cernea, Coolen and Lehman2013), it is speculated that a reduced sensitivity to oestrogen negative feedback and the upregulation of LH pulse frequency in the gilt involve increased neurokinin B activation of kisspeptin neurons. In this regard, kisspeptin neurons in the ARC are likely critical for pubertal onset in gilts.

Oestrogen has a biphasic effect on LH secretion in pigs. Small developing follicles secrete low levels of oestrogen, which suppresses LH (Kesner et al., Reference Kesner, Price-Taras, Kraeling, Rampacek and Barb1989). As circulating concentrations of oestrogen secreted from large preovulatory follicles increase, oestrogen acts positively to stimulate an ovulatory surge of LH about 72 h later (Kraeling et al., Reference Kraeling, Johnson, Barb and Rampacek1998). Treating ovariectomized ewes with a kisspeptin receptor antagonist (p-271) abolished the oestrogen-induced surge of LH (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Li, Yap, Shahab, Roseweir, Millar and Clarke2011), suggesting that kisspeptin is essential for the release of GnRH necessary to induce the LH surge. In this regard, the upregulation of kisspeptin expression in the PeV of the gilt may play a critical role in generating oestrogen-induced ovulatory surge of LH in pigs. When sexually mature ovariectomized gilts were treated with a dose of oestradiol that caused an ovulatory surge of LH, the expression of the kisspeptin gene in the PeV was increased compared to control ovariectomized gilts (Tomikawa et al., Reference Tomikawa, Homma, Tajima, Shibata, Inamoto, Takase, Inoue, Ohkura, Uenoyama, Maeda and Tsukamura2010). The expression of kisspeptin mRNA in the ARC, however, did not differ between oestrogen-treated and control gilts. This implies that discrete subpopulations of kisspeptin neurons in the porcine hypothalamus independently control both surge and tonic secretion of LH.

Kisspeptin receptor gene is expressed in many tissues, including the hypothalamus (Li et al., Reference Li, Ren, Yang, Guo and Huang2008). The expression of the kisspeptin receptor gene in the porcine hypothalamus differs with stage of the oestrous cycle (Li et al., Reference Li, Ren, Yang, Guo and Huang2008). Hypothalamic expression of the kisspeptin receptor gene is increased near the time of puberty in rats and primates (Navarro et al., Reference Navarro, Castellano, Fernandez-Fernandez, Barreiro, Roa, Sanchez-Criado, Aguilar, Dieguez, Pinilla and Tena-Sempere2004; Shahab et al., Reference Shahab, Mastronardi, Seminara, Crowley, Ojeda and Plant2005). These changes are driven by sex steroids from the maturing gonad. How kisspeptin receptor expression changes with sexual maturity or gonadal steroids in the pig is unknown.

Kisspeptin effects on other reproductive organs

The receptor for kisspeptin is expressed in the anterior pituitary gland and the gonad of the pig (Li et al., Reference Li, Ren, Yang, Guo and Huang2008), suggesting a direct effect of kisspeptin on these reproductive tissues. Kisspeptin neural fibres are located in the external zone of the median eminence (ME) of the ewe (Pompolo et al., Reference Pompolo, Pereira, Estrada and Clarke2006), and kisspeptin is secreted into the hypophyseal portal vasculature of sheep (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Rao, Pereira, Caraty, Millar and Clarke2008b) where it can affect pituitary function. In this regard, kisspeptin stimulated LH secretion from the primary cultures of ovine (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Rao, Pereira, Caraty, Millar and Clarke2008b) and porcine (Suzuki et al., Reference Suzuki, Kadokawa and Hashizume2008) anterior pituitary cells. In the porcine ovary, both kisspeptin and kisspeptin receptor are expressed in the granulosa cells and oocytes of developed follicles (Basini et al., Reference Basini, Grasselli, Bussolati, Ciccimarra, Maranesi, Bufalari, Parillo and Zerani2018). Kisspeptin may function in the ovary for ovulation and development of the corpus luteum (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Tang, Zhang, Zhang, Zhong, Zong, Yang and Kuang2013; Laoharatchatathanin et al., Reference Laoharatchatathanin, Terashima, Yonezawa, Kurusu and Kawaminami2015). It was recently reported that kisspeptin improved in vitro development of porcine oocytes (Saadeldin et al., Reference Saadeldin, Swelum, Abdelazim and Almadaly2018). It is becoming increasingly evident that kisspeptin and its receptor can have important effects on peripheral reproductive tissues. What is unclear is the biological relevance this has for pig reproduction. Nonetheless, direct effects at the level of the anterior pituitary gland or ovary could have important implications in the development and use of kisspeptin or kisspeptin analogues for managing reproduction of gilts and sows.

Kisspeptin and nutritional regulation of reproduction

Changing energy balance and hypothalamic expression of kisspeptin

It is well established that the initiation of puberty and postpartum reproductive cycles in pigs are metabolically gated. In general, higher growth rates and backfat are positively associated with earlier cyclicity. Limiting dietary energy and amino acids, or feed restriction, even if supplying metabolizable energy above maintenance requirements, delays sexual maturity in gilts (Beltranena et al., Reference Beltranena, Aherne, Foxcroft and Kirkwood1991; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Moreno and Johnson2011; Calderón Díaz et al., Reference Calderón Díaz, Vallet, Boyd, Lents, Prince, DeDecker, Phillips, Foxcroft and Stalder2017) and decreases LH pulsatility (Prunier et al., Reference Prunier, Martin, Mounier and Bonneau1993; Booth et al., Reference Booth, Cosgrove and Foxcroft1996). Gilts of modern genotypes typically exhibit more than adequate growth rates (Amaral Filha et al., Reference Amaral Filha, Bernardi, Wentz and Bortolozzo2009), but these are less fat and are leaner than in previous generations. This may limit their ability to deal with short-term nutritional challenges associated with diet or housing changes. Gilts, in particular, are very sensitive to metabolic shifts, and even short-term energy restrictions (7 to 10 days) are sufficient to suppress LH pulses (Whisnant and Harrell, Reference Whisnant and Harrell2002; Thorson et al., Reference Thorson, Prezotto, Adams, Petersen, Clapper, Wright, Oliver, Freking, Foote, Berry, Nonneman and Lents2018), and realimentation of gilts restores LH pulses in as little as 12 h (Booth et al., Reference Booth, Cosgrove and Foxcroft1996). At issue here is what are the physiological mechanisms that underlie this nutritional regulation of tonic release of LH in gilts?

Zhou et al. (Reference Zhou, Zhuo, Che, Lin, Fang and Wu2014) restricted feed to cyclic gilts for a prolonged period (100 days), to the point that they ceased cycling. Nutritionally induced acyclicity in pigs results from a complete loss of LH pulsatility (Armstrong and Britt, Reference Armstrong and Britt1987). Using quantitative PCR, it was shown that kisspeptin, kisspeptin receptor and GnRH mRNA expression were all downregulated in the MBH of nutritionally induced acyclic gilts (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhuo, Che, Lin, Fang and Wu2014). This demonstrates that the negative effects of undernutrition on LH secretion in the pig may be mediated through the suppression of the kisspeptin neuronal system. Long-term undernutrition and prolonged BW loss, however, are not common under typical circumstances. More recently, Thorson et al. (Reference Thorson, Prezotto, Adams, Petersen, Clapper, Wright, Oliver, Freking, Foote, Berry, Nonneman and Lents2018) used short-term (10 days) negative energy balance to induce a mild loss in bodyweight that would be similar to what might occur under normal circumstances. In this case, ovariectomized feed-restricted gilts showed reduced frequency and increased amplitude of LH pulses. This change in LH pulse pattern is reflective of a late prepubertal or late lactation LH pulse pattern and would be insufficient to support final maturation and ovulation of ovarian follicles. In this study, in situ hybridization was used to measure the spatial distribution of kisspeptin mRNA expression throughout the entire hypothalamic ARC. No differences in ARC expression of the kisspeptin gene between feed-restricted and full-fed gilts were observed (Thorson et al., Reference Thorson, Prezotto, Adams, Petersen, Clapper, Wright, Oliver, Freking, Foote, Berry, Nonneman and Lents2018). Thus, nutrition-induced changes in LH pulse patterns of gilts can occur without altering the transcription of hypothalamic kisspeptin, which in pigs appears to depend on the duration and magnitude of nutritional restriction.

Feed restriction has been the primary approach to understand nutritional regulation of the reproductive neurosecretory axis in livestock. The converse approach is to feed additional nutrients or energy. In one study, prepubertal gilts were fed either a standard diet formulated to meet the nutritional requirements for gilts (3.22 MCal/kg digestible energy, 19.1% CP) or the standard diet with additional energy in the form of added fat (Zhuo et al., Reference Zhuo, Zhou, Che, Fang, Lin and Wu2014). As would be expected, the gilts fed the higher-energy diet exhibited greater BW gain and accumulation of backfat, resulting in their attaining puberty 12 days earlier than gilts fed the standard diet. When gene expression in the MBH was quantified with PCR, no differences in the expression of kisspeptin, kisspeptin receptor or GnRH mRNA were observed in gilts fed standard or high-energy diets. This would be consistent with the observation of Thorson et al. (Reference Thorson, Prezotto, Adams, Petersen, Clapper, Wright, Oliver, Freking, Foote, Berry, Nonneman and Lents2018) that modest energy restriction of gilts did not affect ARC expression of kisspeptin. On the other hand, mRNA expressions for kisspeptin and its receptor were upregulated in the hypothalamic tissue containing the caudal POA and PeV of gilts fed a higher-energy diet (Zhuo et al., Reference Zhuo, Zhou, Che, Fang, Lin and Wu2014). The POA of the porcine hypothalamus contains a population of GnRH neurons that are considered critical for the initiation of pubertal cycles (Kineman et al., Reference Kineman, Leshin, Crim, Rampacek and Kraeling1988). This implies that dietary regulation of pulsatile secretion of LH in gilts may depend on hypothalamic subpopulations of kisspeptin neurons that respond differently to nutritional signals in regulating the GnRH pulse generator.

Kisspeptin links leptin with gonadotropin secretion

A nutritional signal that has important impacts on the reproductive axis of the pig is leptin (Barb et al., Reference Barb, Hausman and Lents2008; Hausman et al., Reference Hausman, Barb and Lents2012). Leptin is secreted by adipose tissue and is a key regulator of appetite. Age-related increases in the synthesis and secretion of leptin in the pig (Qian et al., Reference Qian, Barb, Compton, Hausman, Azain, Kraeling and Baile1999) are associated with increased expression of leptin receptor in the hypothalamus (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Barb, Matteri, Kraeling, Chen, Meinersmann and Rampacek2000). Both events are related to increased secretion of LH during the pubertal escape from oestrogen negative feedback (Barb et al., Reference Barb, Kraeling, Rampacek and Estienne2000; Barb et al., Reference Barb, Hausman and Kraeling2010a). Furthermore, leptin stimulates the secretion of GnRH from the hypothalamus and LH from the anterior pituitary gland of prepubertal gilts (Barb et al., Reference Barb, Barrett and Kraeling2004a). Consequently, leptin is considered a permissive metabolic signal for the initiation of puberty, and indeed, serum concentrations of leptin are genetically correlated with age at puberty in gilts (Kuehn et al., Reference Kuehn, Nonneman, Klindt and Wise2009). Thus, leptin acting at the level of the hypothalamus is clearly important for the pubertal increase in pulsatile LH secretion in pigs.

Importantly, GnRH neurons lack leptin receptor (Quennell et al., Reference Quennell, Mulligan, Tups, Liu, Phipps, Kemp, Herbison, Grattan and Anderson2009; Louis et al., Reference Louis, Greenwald-Yarnell, Phillips, Coolen, Lehman and Myers2011), which implies that leptin must affect GnRH secretion indirectly through second- or third-order neurons. Leptin receptors are expressed throughout the ARC of the pig hypothalamus (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Barb, Kraeling and Rampacek2001; Czaja et al., Reference Czaja, Lakomy, Sienkiewicz, Kaleczyc, Pidsudko, Barb, Rampacek and Kraeling2002b), indicating that kisspeptin neurons in this region may be direct targets for leptin. In this regard, leptin stimulated the firing of kisspeptin neurons in hypothalamic slices of the ARC from guinea pigs (Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Fang, Bosch, Rønnekleiv and Kelly2011). Although this is strong evidence for a direct effect of leptin on kisspeptin neurons, other studies have called this assumption into question. It was reported that few kisspeptin cells in the hypothalamus of mice or sheep co-localized with STAT3 (Louis et al., Reference Louis, Greenwald-Yarnell, Phillips, Coolen, Lehman and Myers2011; Quennell et al., Reference Quennell, Howell, Roa, Augustine, Grattan and Anderson2011), the major intracellular signalling molecule induced by leptin acting at its receptor. These and other studies have led to the general conclusion that leptin probably affects the secretion of GnRH through other neuronal systems, such as neuropeptide Y (NPY).

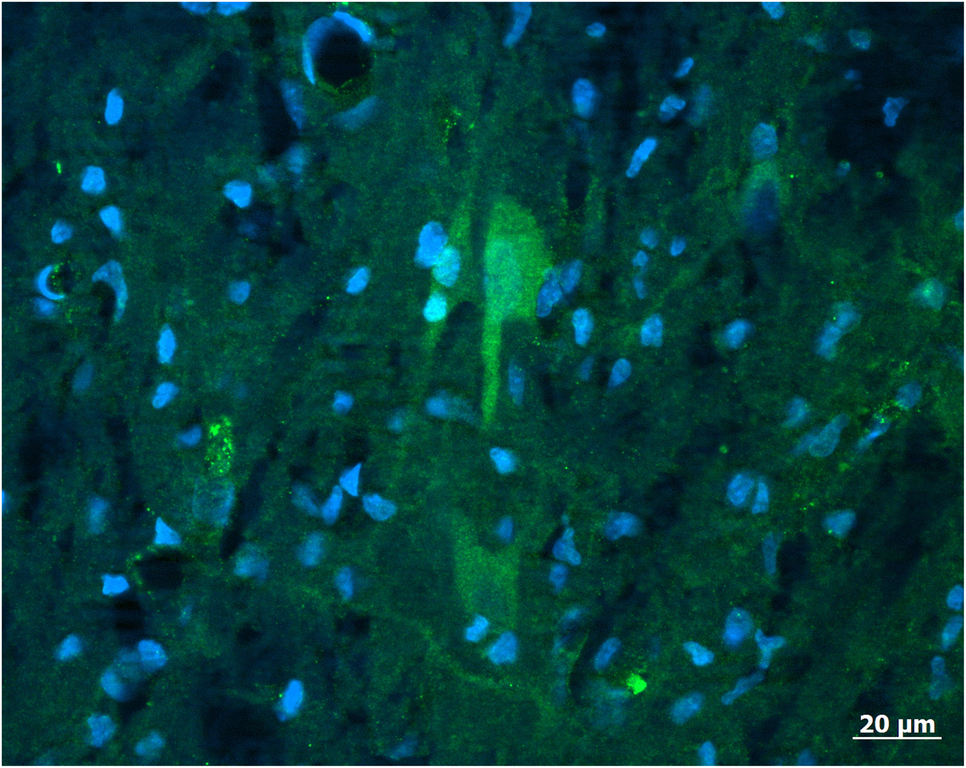

Neuropeptide Y is an orexigenic neuropeptide that is negatively regulated by leptin. Leptin receptor is co-localized with NPY neurons in the pig (Czaja et al., Reference Czaja, Lakomy, Kaleczyc, Barb, Rampacek and Kraeling2002a), demonstrating that NPY is a primary target for leptin in the porcine hypothalamus. When pigs received ICV injections of leptin, it suppressed the stimulatory effect of NPY on food intake (Barb et al., Reference Barb, Kraeling, Rampacek and Hausman2006). Furthermore, the pulsatile secretion of LH in gilts is strongly suppressed by NPY (Barb et al., Reference Barb, Kraeling, Rampacek and Hausman2006). This implies that leptin-induced reduction in NPY is important for increased LH pulses in gilts. Between 30% and 60% of kisspeptin cells in the ARC of sheep and cattle are in close apposition to NPY fibres (Backholer et al., Reference Backholer, Smith, Rao, Pereira, Iqbal, Ogawa and Clarke2010; Alves et al., Reference Alves, Cardoso, Prezotto, Thorson, Bedenbaugh, Sharpton, Caraty, Keisler, Tedeschi, Williams and Amstalden2015), suggesting that NPY might directly suppress kisspeptin neurons to affect GnRH secretion. Fibres for NPY are also in close contact with GnRH neurons in the POA and MBH of heifers (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Cardoso, Prezotto, Thorson, Bedenbaugh, Sharpton, Caraty, Keisler, Tedeschi, Williams and Amstalden2015). When the heifers were fed a high-energy diet that promoted an early age at puberty, the proportion of GnRH neurons contacted by NPY fibres in the MBH were reduced compared with heifers fed a low-energy diet; however, diet did not alter the number of kisspeptin neurons contacted by NPY dendrites (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Cardoso, Prezotto, Thorson, Bedenbaugh, Sharpton, Caraty, Keisler, Tedeschi, Williams and Amstalden2015). These data are interpreted to mean that when circulating concentrations of leptin are low, the expression of NPY is upregulated and suppresses the pulsatile secretion of LH by acting to directly inhibit GnRH release. The suppression of GnRH secretion by NPY may be further amplified by its inhibition of kisspeptin neurons, which attenuates kisspeptin-stimulated release of GnRH. The prepubertal rise of leptin in pigs likely suppresses the negative NPY tone and permits the transition to a higher LH pulse frequency for the initiation of puberty and reproductive cycles (Figure 2).

Figure 2 A model depicting the proposed role of Kiss, NPY and POMC neuronal pathways and their regulation of GnRH secretion during positive and negative energy balance in the pig. Positive energy balance, characterized by nutrient sufficiency, is signalled to the hypothalamus by NPY and POMC cells in the ARC, which act as metabolic sensors for the activation of GnRH secretion. Increasing leptin inhibits the negative effects of NPY on GnRH and Kiss neurons, and upregulates the activation of POMC cells, which project axonal fibres rostrally to the POA and AHA. These afferent projections are predicted to impact both Kiss and GnRH expression cells in the POA and ARC, thus driving increased secretion of GnRH for high-frequency, low-amplitude pulses that promote ovarian follicular growth and maturation. During negative energy balance, leptin is reduced and lessens the excitatory signal (POMC) and increases the inhibitory signal (NPY). Remodelling of neuronal projections from NPY to GnRH neurons inhibit GnRH release for high-amplitude, low-frequency LH pulses that limit the maturation of ovarian follicles. The inhibitory signal of NPY to GnRH secretion is amplified by its inhibition of Kiss neuronal stimulation of GnRH secretion. These neuronal systems are sensitive to feedback from ovarian oestradiol, which switches from one of positive influence to one of negative influence when leptin concentrations are decreasing. OC=optic chiasm; MB=mammillary body; ME=median eminence; INF=infundibulum; AP=anterior pituitary gland; Kiss=kisspeptin; NPY=neuropeptide Y; POMC=proopiomelanocortin; GnRH=gonadotropin-releasing hormone; ARC=arcuate nucleus; AHA=anterior hypothalamic area; POA=preoptic area.

Increasing leptin suppresses feed intake not only by lessening NPY action but also by upregulating proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in the hypothalamus (Barb et al., Reference Barb, Hausman and Lents2008). The POMC gene produces the alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), which, acting at melanocortin-3 and -4 receptors, is anorexigenic in pigs (Barb et al., Reference Barb, Hausman, Rekaya, Lents, Lkhagvadorj, Qu, Cai, Couture, Anderson, Dekkers and Tuggle2010b). The ARC of the porcine hypothalamus contains dense populations of POMC-expressing cells that project neural fibres rostrally to the POA and anterior hypothalamic area (AHA) (Kineman et al., Reference Kineman, Kraeling, Crim, Leshin, Barb and Rampacek1989) where GnRH neurons are found. This indicates a strong possibility for POMC to affect GnRH release in pigs directly or indirectly through kisspeptin neurons in the ARC. Many kisspeptin cells in the ARC of sheep and cattle are in close contact with POMC neuronal fibres (Backholer et al., Reference Backholer, Smith, Rao, Pereira, Iqbal, Ogawa and Clarke2010; Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Alves, Sharpton, Williams and Amstalden2015). Feeding heifers a high-energy diet, which reduced the age of first oestrus, resulted in greater circulating concentrations of leptin, greater expression of α-MSH in the ARC and more kisspeptin cells being contacted by POMC fibres (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Alves, Sharpton, Williams and Amstalden2015). These results suggest that increased signalling from POMC to kisspeptin neurons stimulates increased GnRH secretion for puberty in heifers. In support of this, treating ewes in the luteal phase of the oestrous cycle with a melanocortin agonist (MTII) increased POA expression of kisspeptin, which was accompanied by increased LH pulsatility (Backholer et al., Reference Backholer, Smith and Clarke2009). Whether the same relationship between kisspeptin and POMC neurons exists in the pig is unknown. There are distinct structural differences in the distribution of POMC neurons in pigs compared with ruminants. Unlike cattle (Leshin et al., Reference Leshin, Rund, Crim and Kiser1988), for example, pigs do not exhibit POMC fibres in the external zone of the ME (Kineman et al., Reference Kineman, Kraeling, Crim, Leshin, Barb and Rampacek1989). Treating gilts with a melanocortin antagonist (SHU9119) or a melanocortin agonist (NDP-MSH) failed to affect LH secretion (Barb et al., Reference Barb, Robertson, Barrett, Kraeling and Houseknecht2004b). Caution should be used when interpreting these results because gilts were ovariectomized. Thus, whether POMC signalling at kisspeptin or GnRH neurons in the hypothalamus is related to the pubertal transition in pulsatile secretion of LH in gilts remains to be fully answered.

Kisspeptin and genetic control of fertility

A role for kisspeptin in reproduction did not become evident until it was discovered that some patients with hypogonadal hypogonadism (HH) harboured mutations in the gene for kisspeptin receptor (de Roux et al., Reference de Roux, Genin, Carel, Matsuda, Chaussain and Milgrom2003; Seminara et al., Reference Seminara, Messager, Chatzidaki, Thresher, Acierno, Shagoury, Bo-Abbas, Kuohung, Schwinof, Hendrick, Zahn, Dixon, Kaiser, Slaugenhaupt, Gusella, O’Rahilly, Carlton, Crowley, Aparicio and Colledge2003; Semple et al., Reference Semple, Achermann, Ellery, Farooqi, Karet, Stanhope, O’Rahilly and Aparicio2005). Cases of HH are characterized by a lack of gonadal development and low levels of gonadotropin secretion from the anterior pituitary gland. Individuals with HH arising from mutations in the kisspeptin receptor gene failed to transition through puberty. Patients with HH displayed gonadal responsiveness to treatment with exogenous gonadotropin. Moreover, the secretion of endogenous gonadotropins could be restored when individuals were treated with GnRH (Seminara et al., Reference Seminara, Messager, Chatzidaki, Thresher, Acierno, Shagoury, Bo-Abbas, Kuohung, Schwinof, Hendrick, Zahn, Dixon, Kaiser, Slaugenhaupt, Gusella, O’Rahilly, Carlton, Crowley, Aparicio and Colledge2003). Mouse models were developed in which the gene for kisspeptin or its receptor were knocked out (Funes et al., Reference Funes, Hedrick, Vassileva, Markowitz, Abbondanzo, Golovko, Yang, Monsma and Gustafson2003; Seminara et al., Reference Seminara, Messager, Chatzidaki, Thresher, Acierno, Shagoury, Bo-Abbas, Kuohung, Schwinof, Hendrick, Zahn, Dixon, Kaiser, Slaugenhaupt, Gusella, O’Rahilly, Carlton, Crowley, Aparicio and Colledge2003; d’Anglemont de Tassigny et al., Reference d’Anglemont de Tassigny, Fagg, Dixon, Day, Leitch, Hendrick, Zahn, Franceschini, Caraty, Carlton, Aparicio and Colledge2007; Lapatto et al., Reference Lapatto, Pallais, Zhang, Chan, Mahan, Cerrato, Le, Hoffman and Seminara2007). Indeed, these mice recapitulated the HH phenotype and failed to become pubertal. Males had small testes with no sperm production, reduced sex steroids and lacked the development of secondary sex characteristics. Female kisspeptin receptor-knockout mice failed to have normal ovarian follicular maturation or to become pregnant upon exposure to fertile males. Despite being hypogonadotropic, these mice had normal levels of GnRH in the hypothalamus and a normative response to exogenous GnRH. Other than an infertile phenotype, these mice were completely normal.

Genetically modified large animal models for the study of the kisspeptin system did not exist until 2016 when pigs that contained an edit in the kisspeptin receptor gene were developed (Sonstegard et al., Reference Sonstegard, Carlson, Lancto and Fahrenkrug2016). Boars were produced through somatic cell nuclear transfer using cell lines from White Composite pigs that had been genetically edited with TALen gene editing techniques. The gene edit introduced a premature stop codon in the third exon to create a kisspeptin receptor knockout. The kisspeptin receptor-knockout pig produced a similar hypogonadal phenotype to that observed in mouse knockout models. Histological analysis revealed the formation of seminiferous tubules in the testes; however, no sperm was observed in the lumen of these tubules. The lack of sperm production was presumed to be a consequence of hypogonadotropism as indicated by low circulating concentrations of testosterone (0.20 to 0.25 ng/ml). Results from Sonstegard et al. (Reference Sonstegard, Carlson, Lancto and Fahrenkrug2016) unequivocally demonstrated that kisspeptin neuronal signalling in the hypothalamus is essential for sexual maturation in the pig.

Kisspeptin receptor-knockout boars were noted as being phenotypically normal with similar behaviour and growth as barrow pigs. Although intact, the low androgen production from kisspeptin receptor-knockout boars indicates that their risk of developing boar taint would be low. The possibility of utilizing pigs that are edited for kisspeptin or its receptor for pork production has been postulated (Sonstegard et al., Reference Sonstegard, Fahrenkrug and Carlson2017), and there would be an obvious advantage from an animal welfare standpoint; pigs would not be subjected to castration. Beyond regulatory concerns is the obvious practical challenge of how to produce pigs at a commercial scale from animals with a gene edit that produces an infertile phenotype. When kisspeptin receptor-knockout pigs were treated with either exogenous gonadotropin hormones (both LH and FSH) or GnRH to initiate testicular development, testicular size increased over 200% compared to sham-treated kisspeptin-knockout boars (Sonstegard et al., Reference Sonstegard, Carlson, Lancto and Fahrenkrug2016). Despite histological evidence that testes of hormone-treated knockout boars could potentially support sperm production, no sperm were produced. This illustrates that managing the reproductive phenotype of kisspeptin receptor-knockout pigs will not be straightforward. Does postnatal proliferation of Sertoli cells in these pigs occur to support normal sperm production? Is the spermatogonial stem cell niche in these pigs properly established? These and other important questions will have to be addressed before genetic manipulation of the kisspeptin system for pork production could become practical. Nonetheless, these types of genetically modified pig models hold tremendous potential as a scientific tool to gain new insights into the reproductive development of pigs that could lead to new discoveries to improve pork production.

Genome-wide association studies have been conducted for delayed puberty and age at puberty in White crossbred and composite maternal lines of pigs (Tart et al., Reference Tart, Johnson, Bundy, Ferdinand, McKnite, Wood, Miller, Rothschild, Spangler, Garrick, Kachman and Ciobanu2013; Nonneman et al., Reference Nonneman, Lents, Rohrer, Rempel and Vallet2014 and Reference Nonneman, Schneider, Lents, Wiedmann, Vallet and Rohrer2016). Several genomic regions containing genes regulating growth, adiposity and neural function were identified; however, genomic associations for regions containing kisspeptin or its receptor were not identified. Using a genetic resource population developed from White Duroc × Chinese Erhualian crossbred pigs, Li et al. (2008) identified a number of polymorphisms in the kisspeptin receptor gene. Many of the alleles were fixed or occurred at a higher frequency in Chinese breeds than in Western breeds. Five different haplotypes for polymorphic sites within the kisspeptin receptor gene with frequencies greater than 0.01 were evaluated for association with age at puberty, but no significant association was detected, despite substantial variance in age at puberty within the population. Phenotypic associations for genetic variants that occur at low allele frequency are not easily detected in typical genomic analyses. Functional variants in kisspeptin receptor with deleterious effects would result in complete or substantial infertility and would not likely increase in allele frequency because gilts and boars harbouring such mutations would be quickly culled from the herd. In the case of the kisspeptin gene, it is small and nucleotide variation in the coding sequence is rare. The few kisspeptin sequence variants that have been found in humans are typically monoallelic, and in rare instances these are associated with a reproductive condition, these are more typically associated with precocious puberty rather than hypogonadotropism (De Guillebon et al., Reference De Guillebon, Dwyer, Wahab, Cerrato, Wu, Hall, Martin, Plummer, Au, Pitteloud, Lapatto, Broder-Fingert, Paraschos, Hughes, Seminara, Chan, Van der Kamp, Nader, Min, Bianco, Kaiser, Kirsch, Quinton, Cheetham, Ozata, Ten, Chanoine and Schiffmann2011). Thus, it is unlikely that adequate genetic diversity exists in kisspeptin or kisspeptin receptor genes for genetic selection to improve gilt and sow fertility.

Use of kisspeptin and kisspeptin analogues for pharmacological control of reproductive cycles

The potential for kisspeptin to be useful in managing reproductive cycles and ovulation in livestock is obvious. The bulk of the work in this area has been conducted in sheep (Redmond et al., Reference Redmond, Macedo, Velez, Caraty, Williams and Amstalden2011b) with a few studies in cattle (Whitlock et al., Reference Whitlock, Daniel, Wilborn, Rodning, Maxwell, Steele and Sartin2008; Ezzat Ahmed et al., Reference Ezzat Ahmed, Saito, Sawada, Yaegashi, Yamashita, Hirata, Sawai and Hashizume2009) and mares (Magee et al., Reference Magee, Foradori, Bruemmer, Arreguin-Arevalo, McCue, Handa, Squires and Clay2009; Decourt et al., Reference Decourt, Caraty, Briant, Guillaume, Lomet, Chesneau, Lardic, Duchamp, Reigner, Monget, Dufourny, Beltramo and Dardente2014). These studies encompass a wide range of differences in seasonality, presence of gonadal steroid feedback, stage of the ovarian cycle and state of sexual maturation that must be taken into careful consideration when comparing studies. In general, IV injection of kisspeptin at doses ranging from 0.75 to 5 nmol/kg induce a surge-like release of LH in cattle and sheep (Caraty et al., Reference Caraty, Smith, Lomet, Ben Said, Morrissey, Cognie, Doughton, Baril, Briant and Clarke2007a; Whitlock et al., Reference Whitlock, Daniel, Wilborn, Rodning, Maxwell, Steele and Sartin2008; Redmond et al., Reference Redmond, Macedo, Velez, Caraty, Williams and Amstalden2011b). Endocrine changes for prepubertal gilts treated with approximately 11.4 to 56.9 nmol/kg (768 to 3839 nmol per gilt) of kisspeptin have been reported (Lents et al., Reference Lents, Heidorn, Barb and Ford2008) and are similar to those observed in other species. All doses of kisspeptin induced a surge-like release of LH. The 11.4 nmol/kg dose of kisspeptin is probably maximal in pigs as there was no further increase in LH secretion beyond this dose. Regardless of treatment dose, the pulse of LH was transient, lasting for about 1.5 h before returning to baseline due to the short half-life (<60 s) of kisspeptin in serum. Moreover, FSH secretion in these gilts was not effectively stimulated by IV treatment with kisspeptin. These data were recently corroborated when it was reported that IV treatment of 18-week-old gilts with kisspeptin at even higher doses (3839 and 7678 nmol per gilt) induced similar secretory profiles of LH (Ralph et al., Reference Ralph, Kirkwood and Tilbrook2017). The secretory profile of gonadotropins in prepubertal gilts treated with a single injection of kisspeptin would not be expected to affect ovarian follicular growth sufficiently to lead to oestrus and ovulation.

To sustain the secretion of gonadotropin hormones, repeated injections of kisspeptin are required. Repeated injections of kisspeptin to ovariectomized (Caraty et al., Reference Caraty, Smith, Lomet, Ben Said, Morrissey, Cognie, Doughton, Baril, Briant and Clarke2007a) or seasonally anoestrous ewes (Caraty et al., Reference Caraty, Lomet, Sebert, Guillaume, Beltramo and Evans2013) resulted in repeatable pulses of LH, but no effects on FSH. Similar results were obtained in prepubertal ewe lambs treated every hour for 24 h (Redmond et al., Reference Redmond, Macedo, Velez, Caraty, Williams and Amstalden2011b). An LH surge occurred at about 17 h after the start of treatment in four of the six kisspeptin-treated lambs and resulted in ovulation. These lambs failed to maintain corpora lutea, suggesting that gonadotropin output after cessation of kisspeptin treatment was not adequate for luteotropic support. Sufficient sexual maturation in females must occur such that the GnRH pulse generator can be sustained to make kisspeptin treatment useful in prepubertal animals. The other approach that has been tested is to continuously infuse kisspeptin. In adult ovariectomized (Caraty et al., Reference Caraty, Smith, Lomet, Ben Said, Morrissey, Cognie, Doughton, Baril, Briant and Clarke2007a) or anoestrous ewes (Caraty et al., Reference Caraty, Smith, Lomet, Ben Said, Morrissey, Cognie, Doughton, Baril, Briant and Clarke2007a; Sebert et al., Reference Sebert, Lomet, Said, Monget, Briant, Scaramuzzi and Caraty2010), continuous infusion resulted in an initial increase in LH secretion followed by an ovulatory surge of LH between 15 and 30 h later. Approximately 80% of kisspeptin-treated ewes ovulated. The initial kisspeptin-induced increase in LH and FSH was followed subsequently by increasing the concentrations of oestradiol from developing follicles that were critical for the induction of the subsequent LH surge. Similar increases in LH and FSH were seen with kisspeptin treatment in the mare, but kisspeptin failed to stimulate ovulation (Magee et al., Reference Magee, Foradori, Bruemmer, Arreguin-Arevalo, McCue, Handa, Squires and Clay2009; Decourt et al., Reference Decourt, Caraty, Briant, Guillaume, Lomet, Chesneau, Lardic, Duchamp, Reigner, Monget, Dufourny, Beltramo and Dardente2014). Important differences between mares and ewes are that mares are oestrus for a longer duration, the timing of the ovulatory LH surge relative to the start of oestrus is more variable, and the LH surge is more protracted. There have been no studies in pigs evaluating the effect of sustained infusion of kisspeptin on inducing an LH surge or ovulation; however, it is noted that a long duration of oestrus and variable timing of the LH surge relative to the onset of oestrus and ovulation in pigs is similar to that of the mare. This highlights the important need for species-specific studies in kisspeptin research.

Repeated injections or chronic infusion are not practical for the reproductive management of livestock. Some researchers have tried to alter kisspeptin to increase its half-life or potency to overcome this issue. This approach was successful for GnRH but has proven to be less useful for kisspeptin. There are some kisspeptin analogues that have been developed and tested for their ability to control reproduction in livestock (Table 1). The effects of kisspeptin analogue TAK683 (kisspeptin receptor agonist; Ac-[D-Tyr46,D-Trp47,Thr49,azaGly51,Arg(Me)53,Trp54]metastin(46-54)) on LH have been extensively characterized in goats. Small doses (3.5 nmol) given IV or SC to cyclic does after the removal of a progesterone device (CIDR) resulted in elevated concentrations of LH for 10 h (Kanai et al., Reference Kanai, Endo, Ohkura, Wakabayashi, Matsui, Matsumoto, Ishikawa, Tanaka, Watanabe, Okamura and Tanaka2017). The SC treatment resulted in a preovulatory increase in oestradiol and advanced ovulation by 3 days. In ovariectomized does, TAK683 had minimal (Goto et al., Reference Goto, Endo, Nagai, Ohkura, Wakabayashi, Tanaka, Matsui, Kusaka, Okamura and Tanaka2014) to no effect (Kanai et al., Reference Kanai, Endo, Ohkura, Wakabayashi, Matsui, Matsumoto, Ishikawa, Tanaka, Watanabe, Okamura and Tanaka2017) on LH secretion, which highlights the importance of ovarian steroids in modulating the effects of kisspeptin analogues. Other studies reported that IV injections of 35 nmol of TAK683 induced surges of LH lasting 6 to 12 h in follicular and luteal-phase does (Endo et al., Reference Endo, Tamesaki, Ohkura, Wakabayashi, Matsui, Tanaka, Watanabe, Okamura and Tanaka2015). The timing of oestradiol changes associated with TAK683 injection depended upon the phase of oestrous cycle at the time of treatment, but ovulation was induced in five of five does and four of five does when TAK683 treatment was initiated in the follicular and luteal phase of the oestrous cycle, respectively. The magnitude of LH release induced by TAK683 was greater when does were treated in the follicular phase (Endo et al., Reference Endo, Tamesaki, Ohkura, Wakabayashi, Matsui, Tanaka, Watanabe, Okamura and Tanaka2015) than in the luteal phase (Endo et al., Reference Endo, Tamesaki, Ohkura, Wakabayashi, Matsui, Tanaka, Watanabe, Okamura and Tanaka2015; Rahayu et al., Reference Rahayu, Behiry, Endo and Tanaka2017).

Table 1 Effect of kisspeptin analogues on the indices of reproductive function in livestock

OVX=ovariectomized; CIDR=progesterone-controlled internal drug release; PG600=400 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropin and 200 IU chorionic gonadotropin; TAK683=Ac-[D-Tyr46,D-Trp47,Thr49,azaGly51,Arg(Me)53,Trp54]metastin(46-54); C17=Palm-γ-Glu-Tyr-Lys[γ(N-Palm-Glu)]-Trp-Asn-Ser-Phe-Glyψ[Tz]Leu-Arg-Tyr-NH2; C6=Palm-γ-Glu-Tyr-Asn-Trp-Asn-Ser-Phe-Glyψ[Tz]Leu-Arg(Me)-Tyr-NH2; FTM080=4-Fluorobenzoyl-Phe-Gly-Leu-Arg-Trp-NH2; IV=intravenous; SC=subcutaneous; IM=intramuscular.

Although these data would support the expectation that TAK683 could be useful for inducing or timing ovulation in livestock, there are negative effects. The TAK683 molecule was developed as a kisspeptin receptor antagonist. After the initial increase in LH secretion, TAK683 suppresses LH pulsatility and circulating concentrations of LH within 24 h from the start of treatment (Yamamura et al., Reference Yamamura, Wakabayashi, Sakamoto, Matsui, Kusaka, Tanaka, Ohkura and Okamura2014). Pulsatile secretion of LH was completely abolished in ovariectomized does treated with a 5-day SC infusion (500 nmol/kg) of TAK683. This effect has intriguing potential for managing reproduction in pigs. Altrenogest is the only approved product available to prevent oestrus and ovulation in pigs and is used extensively to synchronize oestrus. Kisspeptin antagonists could be a useful alternative because pituitary responsiveness to GnRH remains intact. Chronic SC infusion of TAK683 appears to abolish LH pulses in goats without affecting the GnRH pulse generator (Yamamura et al., Reference Yamamura, Wakabayashi, Sakamoto, Matsui, Kusaka, Tanaka, Ohkura and Okamura2014). However, there may be negative effects on ovarian follicles at subsequent ovulations. Goto et al. (Reference Goto, Endo, Nagai, Ohkura, Wakabayashi, Tanaka, Matsui, Kusaka, Okamura and Tanaka2014) reported that ovulations induced in cyclic does with TAK683 resulted in lower levels of progesterone during the luteal cycle. Moreover, the emergence of new follicles was delayed in these goats. Consequently, they ovulated smaller, less mature follicles in the subsequent oestrous cycle, which would be expected to reduce fertility. These and other issues will need to be addressed for the effective use of such kisspeptin antagonists in pork production.

Another well-characterized compound is the kisspeptin receptor agonist C6 (Palm-γ-Glu-Tyr-Asn-Trp-Asn-Ser-Phe-Glyψ[Tz]Leu-Arg(Me)-Tyr-NH2). In adult rams, i.m. injections of C6 (15 nmol) resulted in a sustained (10 h) increase in circulating concentrations of LH that were accompanied by elevated concentrations of testosterone (Beltramo and Decourt, Reference Beltramo and Decourt2018). Prepubertal bulls treated with C6 exhibited greater secretion of LH lasting 6 h, but FSH and testosterone were unaffected (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Coffman, Pohler, Daniel, Aucagne, Beltramo and Whitlock2019). This may indicate that adequate pubertal development must occur in bulls to achieve the expected gonadal response. Moreover, repeated injections of C6 to prepubertal bulls for 4 days resulted in a loss of LH secretory response to treatment, possibly resulting from kisspeptin receptor desensitization. In adult acyclic ewes primed with progesterone or in cyclic ewes, a single IM injection of C6 resulted in an increase in LH secretion lasting 10 to 12 h (Decourt et al., Reference Decourt, Robert, Anger, Galibert, Madinier, Liu, Dardente, Lomet, Delmas, Caraty, Herbison, Anderson, Aucagne and Beltramo2016). This treatment in cyclic ewes resulted in an initial surge-like release of FSH followed by a sustained increase in the secretion of FSH, such as would follow ovulation, approximately 24 h after C6 treatment started. Indeed, all 12 of the cyclic ewes treated with C6 ovulated, and 8 of 12 noncyclic ewes ovulated in response to C6 treatment. A preliminary report indicated that a single IM injection of C6 to 18-week-old gilts caused a sustained increase in LH secretion resulting in ovulation in five of seven gilts (Ralph et al., Reference Ralph, Kirkwood, Beltramo, Aucagne and Tilbrook2018). In this case, gilts had been primed with human chorionic and pregnant mare serum gonadotropin followed by altrenogest such that adequate follicle development was present for ovulation to occur. It is not clear if C6 may be useful for stimulating oestrus and ovulation in non-steroid-primed prepubertal gilts or postpartum sows. Nonetheless, the results point to a real possibility that kisspeptin analogues could be developed for the control of reproduction in pigs.

Is kisspeptin involved in seasonal infertility of swine?

In the northern hemisphere, seasonal decreases in fertility are evident in commercial swine. This seasonal infertility is a decrease in the reproductive performance of pigs during summer and early fall (July, August, September) that manifests as reduced farrowing rates during the winter months (November, December, January). In the southern hemisphere, decreased farrowing rates are observed in late summer to early autumn. Seasonal infertility usually affects 5% to 10% of breeding females, but this can be as high as 25% in some geographical locations or production systems. The summer decrease in reproductive performance of pigs is generally characterized by decreased cyclicity of replacement gilts, increased wean to oestrus intervals of sows, increased loss of pregnancy and reduced litter size, with gilts and first parity sows being most affected (Tummaruk et al., Reference Tummaruk, Tantasuparuk, Techakumphu and Kunavongkrit2007; Bloemhof et al., Reference Bloemhof, Mathur, Knol and van der Waaij2013). It must be noted that seasonal infertility is an issue affecting all geographical regions of pork production and a wide array of management and housing systems. Many risk factors, including heat stress, nutritional stress, immune function, ovarian function, uterine function, and others, have been linked to seasonal infertility of pigs, which illustrates the extremely complex aetiology of the problem. The discussion that follows is highly focused. For a broader perspective, the reader is referred to more comprehensive reviews (Love et al., Reference Love, Evans and Klupiec1993; Peltoniemi and Virolainen, Reference Peltoniemi and Virolainen2006; Bertoldo et al., Reference Bertoldo, Holyoake, Evans and Grupen2012; De Rensis et al., Reference De Rensis, Ziecik and Kirkwood2017).

It is generally concluded that seasonal infertility in swine involves, to some extent, inadequate gonadotropin secretion. Reduced GnRH, LH and FSH in weaned sows has been reported during summer months (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Britt and Cox1986). The reason for this is not fully understood, but it is speculated to be related to increased sensitivity to oestradiol negative feedback during summer months. The suppressive effect of oestradiol on basal concentrations of LH and LH pulse amplitude of gilts, however, was greater during short-day photoperiod than in long-day photoperiod (see Love et al., Reference Love, Evans and Klupiec1993). Further, season had little to no effect on the LH secretory response of ovariectomized gilts treated with low or high levels of oestradiol, nor was there a season × oestradiol interaction on the response of gilts to exogenous GnRH (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Ramirez, Matamoros, Bennett and Britt1987; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Almond and Dial1991). Seasonally anoestrus weaned primiparous sows responded normally to pulsatile treatment with GnRH (Armstrong and Britt, Reference Armstrong and Britt1985), exogenous oestradiol (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Esbenshade and Britt1983) and gonadotropin hormones (Britt et al., Reference Britt, Esbenshade and Heller1986), suggesting that the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian–axis of sows remains fully functional during summer months. These data indicate that any potential seasonal effect on gonadotropin secretion in the pig lies upstream of GnRH, but seasonal responses to oestradiol feedback are yet to be fully resolved.

Seasonal acyclicity exhibited by caprine and ovine species is determined by increases in daylength that result in an increase in sensitivity to oestrogen negative feedback and molecular changes in the expression of kisspeptin in the hypothalamus associated with a reduced frequency of LH pulses (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Clay, Caraty and Clarke2007; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Coolen, Kriegsfeld, Sari, Jaafarzadehshirazi, Maltby, Bateman, Goodman, Tilbrook, Ubuka, Bentley, Clarke and Lehman2008a). Seasonal infertility of domestic swine coincides with the nonbreeding season of Eurasian wild boar (Mauget, Reference Mauget, Cole and Foxcroft1982), and it has been proposed that the kisspeptin neuronal system may underlie seasonal differences in gonadotropin secretion of domestic sows (De Rensis et al., Reference De Rensis, Ziecik and Kirkwood2017). There have been no published studies evaluating the effect of season, photoperiod or melatonin on kisspeptin function in pigs; so this hypothesis remains to be tested. It is difficult to unravel the confounding of seasonal changes in temperature and photoperiod, but these factors can have independent effects on sow fertility (Tantasuparuk et al., Reference Tantasuparuk, Lundeheim, Dalin, Kunavongkrit and Einarsson2000; Sevillano et al., Reference Sevillano, Mulder, Rashidi, Mathur and Knol2016) (Auvigne et al., Reference Auvigne, Leneveu, Jehannin, Peltoniemi and Sallé2010). Regardless, seasonal effects on LH seem to be largely related to a suppression of feed intake and its associated metabolic state. As discussed above, fluctuations in nutrient intake seem to have little effect on the expression of kisspeptin mRNA unless nutritional restriction is severe and prolonged. Whether differences in feed intake are affecting the transcription and expression of kisspeptin protein, however, remain to be determined. Administering kisspeptin or its analogues to seasonal anoestrous ewes overcomes the seasonal inhibition of LH secretion leading to ovulation (Caraty et al., Reference Caraty, Smith, Lomet, Ben Said, Morrissey, Cognie, Doughton, Baril, Briant and Clarke2007a; Sebert et al., Reference Sebert, Lomet, Said, Monget, Briant, Scaramuzzi and Caraty2010; Decourt et al., Reference Decourt, Robert, Anger, Galibert, Madinier, Liu, Dardente, Lomet, Delmas, Caraty, Herbison, Anderson, Aucagne and Beltramo2016). It is expected that as kisspeptin analogues become developed and optimized for use in swine, these will be useful tools for mitigating seasonal effects on sow fertility.

Conclusion

Strong evidence has accumulated that kisspeptin is a critical component in the regulation of gonadotropin secretion and reproduction in swine. Anatomical distribution of the kisspeptin neuronal system is organized similarly in the pig as other species, but there are clear differences in its regulation, particularly from gonadal steroids. In this regard, research on the role of kisspeptin in regulating reproductive biology of pigs has lagged that of other livestock species, particularly sheep and goats. This is a critical area of need going forward because of the distinct physiological differences between species. Kisspeptin and kisspeptin analogues demonstrate promise for use in managing reproductive cycles and ovulation in pigs. However, pig-specific research is needed to optimize the use of such compounds for a precise control of fertility in pork production.

Acknowledgements

None.

Declaration of interest

Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the USDA. The USDA prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, colour, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Ethics statement

No relevant information to declare for review article.

Software and data repository resources

None of the data were deposited in an official repository.