The Politics of Lynching

Following the end of the Civil War, the Radical Republicans used the Union Army to suppress White racist violence, disenfranchise former Confederates, and force the former Confederate states to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment. During these years, Southern Blacks’ political power and representation in the American South increased dramatically. Although White supremacists often suppressed Black and White-Republican political power through violence, the Union Army remained a powerful counterweight. By 1876, however, only a few statesFootnote 1 remained under Reconstruction Republican governorship. The ending of Reconstruction accelerated in 1876 with the contested election of Rutherford Hayes, who was loath to use the federal government and Union Army in defense of Blacks and White Republicans. The Republican Party, and Black political power generally, soon crumbled in the Deep South in the face of White supremacist electoral fraud and violence (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1998 [1935]: 670–90; Foner Reference Foner1990: 242–49).

Following the withdrawal of federal intervention, White supremacist violence became more public and less covert. The kinds of lynchings that Ida B. Wells termed “color-line murder” (Wells 1909) became a favored terrorist tactic of White supremacists throughout the former slave states (Brundage Reference Brundage1993; Tolnay and Beck Reference Bederman1995). Between 1883 and 1943, well more than four thousand people, mostly Black men, were murdered by lynch mobs in the United States (Seguin and Rigby Reference Beck and Tolnay2019). Color-line lynchings had many proximate causes, but ultimately resulted from White’s motivation to reestablish a system similar to slavery (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1998 [1935]: ch. XVI), and a lack of state protection of Blacks from White violence (see, e.g., Hagen et al. Reference Carle2013). Color-line lynchings also helped cement such White political supremacy by intimidating Blacks and increasing White racial solidarity (Smångs Reference Gottschalk2016).

Particularly after 1877, most Whites saw racist violence as a local matter, and “the South’s rulers enjoyed a free hand in managing the region’s domestic affairs” (Foner Reference Foner1990: 248). Throughout the 1880s, many Whites drew on previous framings of lynching in the Wild West which understood lynching as a legitimate—even democratic—form of “rough justice” (Waldrep Reference Blackett2002: ch. 3). White newspapers, both northern and southern, framed lynchings as crime stories in which mobs of “determined citizens” were the agents of direct democratic justice, unmediated by slow and ineffectual courts. Newspapers framed lynching victims as depraved criminal “brutes,” and presidents and lawmakers tended to ignore lynching altogether (ibid.). Local elites, law enforcement, and newspapers often tacitly endorsed lynching through silence or even explicitly promoted it (Jean Reference Barrow2005). Over time, however, lynching lost legitimacy with many of the national institutions that once supported it, and newspapers outside of the South began framing lynching as shaming the United States before the “civilized world”:

Northern periodicals stopped treating lynching as a colorful Southern folkway. They dropped their jocular tones and piously condemned lynching as “barbarous.” It became a truism that lynching hurt America in the eyes of the “civilized world.” (Bederman Reference Bederman1995: 70; see also: Waldrep Reference Blackett2002: 124–25)

American presidents, even those known to champion racist policies, also began to denounce lynching. For example, Ming-Francis shows how increasing pressure from the NAACP prompted Woodrow Wilson to make a statement condemning lynching in July 1919, and that the NAACP’s efforts to educate President Harding prompted him to make multiple statements in opposition to lynching (2014: 73–90).

Scholars agree that sometime between the early 1890s and late 1920s, lynching became increasingly viewed as “uncivilized” by White institutions outside of the South. Accounts differ, however, on exactly when and why lynching lost legitimacy. Some argue that the transformation began in response to Ida B. Wells’s 1894 British tour (e.g., Bederman Reference Bederman1995: 70; Waldrep Reference Blackett2002). Others argue it began during the World War I years in response to the early NAACP’s antilynching campaign and the lynching of Jesse Washington in 1916 (e.g., Bernstein Reference Barrow2005; Brundage Reference Brundage1993; Ming-Francis Reference Ming-Francis2014). Because these studies implicate many different actors and historical eras, we use a wide lens to analyze changes in what we call “lynching politics”: the ways political actors such as activists, journalists, and politicians attacked or defended the practice of lynching. We draw on data from five sources. First, we use datasets describing all known lynchings from 1883 to 1930 in the United States (Seguin and Rigby Reference Beck and Tolnay2019; Tolnay and Beck Reference Bederman1995) to identify which lynchings were the most widely covered in national newspapers. Second, we searched through all State of the Union (SOTU) messages and addresses from 1880 to 1930 to identify when presidents discussed lynching (Woolley and Peters 2011). Third, we use dictionary (keyword) analyses to evaluate when the national newspapers began framing lynching as “barbaric” or “uncivilized.” Fourth, we analyze all articles relating to lynching in the United States from one British newspaper and two Italian newspapers. Fifth, we draw on archival sources from both the United States and Italy.

Our expansive approach to data collection and analysis allows us to identify cases and dynamics that past scholarship overlooks. We find that across domestic and international newspapers and the US presidency, an antilynching response began in 1891 in response to a lynching of 11 Italian immigrants in New Orleans. This lynching is widely known in the literature (see, e.g. Webb Reference Blackett2002), but its effects have not been fully appreciated. We argue this lynching had two key effects: (1) it brought direct and immediate political pressure on American political elites from the Italian embassy, and (2) it generated international condemnation of lynching in the United States from other European states. We then show how Ida B. Wells capitalized on this international outrage during her 1893 and 1894 British tours to draw international attention to the lynching of Black Americans. This international condemnation created an “interest convergence” (Bell Reference Barrow2005) wherein Whites concerned with the United States’ international reputation now had a shared interest with Blacks in denouncing and containing lynching. Presidents such as Harrison and McKinley began by condemning the lynching of Italian nationals. Later presidents, most notably Theodore Roosevelt, denounced the lynching of Blacks in response to international outrage. We conclude by discussing the implications of this case for understanding the politics of racist violence more generally.

Research Design and Data Gathering

We used a combination of digital text searches and qualitative techniques to gather and analyze data. Table 1 summarizes these datasets and analyses. Our overall strategy begins with systematic searches of newspapers and presidential SOTU addresses to identify moments of increased political attention to lynching. We gathered data on which lynching victims were most covered in the national newspapers, when presidents spoke about lynching in the SOTU, and when papers began framing lynching as “uncivilized.” We then used these data to guide further data collection from international newspapers in Britain and Italy, archival sources in the United States and Italy, and additional secondary sources. Although Congress was an important political actor, we do not include congressional data because searches of the Congressional Record showed little meaningful activity on lynching until the 1920s.Footnote 2 Considering that international relations are the president’s prerogative, it makes sense that we would see less congressional action on lynching if, as we argue, Whites mainly treated it as an international relations issue. Table 1 briefly summarizes our six sources of data and analyses, which we discuss in detail in the following text.

Table 1. Data and sources

Lynching Victims in the National Newspapers

News media tend to report on discrete events rather than trends found in statistics, and this period was no different (Ryfe Reference Hess and Brian2006: 62). We therefore focus on specific lynching events to understand what newspapers were saying about lynching. To identify the most politically significant events, we searched newspapers for every known lynching in the United States from 1883 to 1930. We began with Tolnay and Beck’s original (1995) inventory of lynching victims, supplemented with data from outside the Southeast from Seguin and Rigby (Reference Beck and Tolnay2019). These data gave us identifying information on 3,627 unique victims of lynching.Footnote 3 We searched digital archives of three major national papers with broad geographic coverage from outside the Southeast (the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and Los Angeles Times)Footnote 4 to identify articles that mentioned any of these 3,627 victims. For each victim, we queried the online archives using a Boolean search for the last name(s) of the victim(s), the name of the state or place-line abbreviation of the state (e.g., Ala. for Alabama), and the terms “lynching,” “lynched,” or “lynches.”Footnote 5 We searched for articles for each victim in a 30-day window beginning on the day of the lynching. In most cases, this search strategy worked well. In cases such as mass lynchings, however, where individual names were often not reported, we used search terms that referenced a more specific location instead of victims’ names. This procedure yielded a count of newspaper articles devoted to each lynching in the three papers we searched. Article counts are not exact measures of media attention, but they do correlate highly with more sophisticated measures that include things like story placement or word counts.Footnote 6 We used these counts as a guide to help locate politically influential lynchings.Footnote 7

Presidential Data

We gathered systematic data on presidential attention to lynching from SOTUs from 1880 to 1930, made available through the Presidency Project (Woolley and Peters 2011). SOTUs are prominent speeches and occur at regular intervals, making them useful for studies of change in presidential rhetoric over time (see, e.g., Rule et al. Reference Beck2015). We searched all SOTUs for any mention of “lynching” or “lynched” or “mob” (N = 50 SOTUs). We found 13 SOTUs (26% of the total) that mentioned lynching and read these addresses closely, followed by targeted searches for additional sources on presidential discourse, as we discuss in the text that follows.

Civilization Discourse Data

The literature on lynching identifies an important change in the language used to describe lynchings by the northern press and political elites. This language, which we call “civilization discourse,” drew from imperialist themes, casting the violence of lynching as indicative of “lower civilization” or “savagery,” as opposed to the “higher [White] civilization” to which most of the United States supposedly belonged (see especially, Bederman Reference Bederman1995; Waldrep Reference Blackett2002). We drew upon this literature and our own experience from reading thousands of newspaper articles on lynching to develop a set of keywords that would identify the presence of “civilization discourse” in newspaper articles. Our keyword searches are less technically sophisticated than machine-learning approaches to text classification. However, dictionary or keyword searches are reliable when properly validated and more interpretable when guided by the analyst’s substantive knowledge (Grimmer and Stewart Reference Carle2013: 274–75). We selected keywords that generally referred to mob participants or actions rather than the victim or their alleged offense. The terms “brute” or “brutes,” for example, were generally used to describe Black victims in an animalistic way and generally not applied to mobs. “Savage,” “savagery,” or “savages” occasionally referred to Native American victims but far more often referred to the mob’s members or actions. We then used these keywords to search digital archives of the Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and New York Times and gather all matching newspaper articles.Footnote 8 We describe the method and our validation procedures more thoroughly in appendix 1 (online supplementary materials).

International Newspaper Data

We gathered data on the amount of attention that both British and Italian newspapers paid to Black and Italian lynching victims in the United States. Prior research has argued that Ida B. Wells’s British tours of 1893 and 1894 spurred British criticism of American lynching, which was particularly influential given Britain’s claim to “higher civilization” (e.g., Silkey Reference Beck2015; Weber 2011). Italian reactions to the lynching of their conationals in the United States brought direct political pressure from the Italian embassy (Webb Reference Blackett2002) and helped make lynching in the United States a global news topic.

To analyze British news coverage, we searched the digital archives of the Manchester Guardian for all news articles mentioning “lynching” or “lynched” as well as “America” or the “United States” from 1880 to 1930, yielding 889 articles. We read these articles and confirmed that 458 out of 889 were, in fact, about lynching in the United States.Footnote 9 We manually coded these 458 remaining articles, assigning a code for whether the article discussed the lynching of Black Americans, Italians, or other groups (mainly Mexicans, Chinese, and White Americans).

We selected the digital archives of two Italian national papers, La Stampa and Corriere Della Sera, from which we gathered all lynching related articles for the period 1880–1930. These two papers were founded, respectively, in 1867 and 1876, in Turin and Milan. Today they are the most important newspapers in the country, and they were among the few papers of the time that reported both national and global news. We developed a list of search terms that include derivatives of the Italian verb linciare Footnote 10 (to lynch) to search both archives from 1880 to 1930 and collected matching articles. We read the resulting 1,962 articles, keeping only the articles about lynching in the United States, yielding 271 articles from La Stampa and 332 from Corriere della Sera. Footnote 11 We then systematically coded these articles, assigning a code for whether the article discussed the lynching of Black Americans, Italians, or other groups (mainly Mexicans, Chinese, and White Americans).

Archival Data

Data on newspapers, presidential speeches, and lynching victims provides detailed and broad-based information on the reaction to lynching. Still, these data do little to establish what moved political elites to action. To understand the motivations of political elites, we relied on secondary literature when possible, but often found it necessary to gather detailed archival information on the interactions and deliberations of Italian and US political elites.

Correspondence regarding US-Italian diplomatic relations comes from the Italian archive of Foreign Affairs, Archivio Storico Diplomatico Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale, located in Rome. This archive stores the official documentation produced by consular representatives of Italy abroad. We made three visits to this archive between December 2016 and January 2017, allowing us to reconstruct US-Italian diplomatic correspondence regarding lynchings of Italian citizens in New Orleans, Louisiana, Walsenburg, Colorado, Hahnville, Louisiana, Tallulah, Mississippi, Erwin, Mississippi, and Tampa, Florida.

Our data on SOTU addresses, and some of the secondary literature (e.g., Ziglar Reference Ziglar1988), showed that the Roosevelt administration spoke out on lynching more than did other presidents. We found that existing biographies and other secondary sources did not provide sufficient details to reconstruct Roosevelt’s decision making during critical moments. Here we used the Theodore Roosevelt Center’s online archives to locate correspondence from Roosevelt and relevant administration members like Secretary of State John Hay.

We also drew on sources from other digitized historical newspaper archives for many of our case studies, such as the London Times’ digital archives and other newspapers through the Chronicling America digital archive. These archives allowed us to reconstruct critical moments, such as how the British responded to the lynching of George White in 1903.

The Lynching of Italians and the Origin of Antilynching Politics

Lynchings of Blacks rose from 1877 into the early 1880s (Beck 2015: 124). In the seven years and two months from January 1883 until February of 1891, lynchings of Blacks declined some, but our data still record 631 Black victims of lynching. During these years, following the White national consensus established in the late 1870s, lynching and racial violence generally were considered “local matters” by the larger White public and political elites. Newspapers often ignored the lynching of Blacks, and even mass lynchings of Blacks could receive little attention. For instance, in December 1889, eight Blacks were lynched in Barnwell County, South Carolina, with almost no mention of it in the national press. When White newspapers did cover the lynching of Black victims, they often framed the lynchings as “rough justice” in response to the supposed crimes of “black brutes.”Footnote 12 The New York Times, for instance, recycled the headline “Brutal Negro Lynched” 11 times over this period. SOTUs from this period did not mention lynching even in general terms. White newspapers and US presidents simply did not consider lynching an important political issue so long as its victims were Black.Footnote 13

The lynching of 11 Italians in March 1891 set processes into motion that would make lynching—first of foreign nationals and later of Black Americans—into a political problem for many White Americans. Much of White American society during the 1880s and 1890s maligned Sicilians as undesirable immigrants who were prone to violence and brought with them a political culture that was incompatible with American democracy. Between 1886 and 1910, mobs lynched 29 Sicilians in the United States, far fewer than the thousands of Black American lynching victims, but more than any other European immigrant group (Webb Reference Blackett2002: 46). Native-born White Americans generally had little sympathy for Sicilian lynching victims (Webb Reference Blackett2002: 48). Italians, in contrast to American Blacks, however, had institutional power through their embassy, which reacted quickly to the lynching of Italian citizens beginning in 1891 (Webb Reference Blackett2002). As Ida B. Wells would note less than two years later:

In the past ten years over a thousand colored men, women and children have been butchered, murdered and burnt in all parts of the South. The details of these horrible outrages seldom reach beyond the narrow world where they occur. Those who commit the murders write the reports, and hence these lasting blots upon the honor of a nation cause but a faint ripple on the outside world. They arouse no great indignation and call forth no adequate demand for justice. The victims were black, and the reports are so written as to make it appear that the helpless creatures deserved the fate which overtook them. Not so with the Italian lynching of 1891. They were not black men, and three of them were not citizens of the Republic, but subjects of the King of Italy. (Wells Reference Wells1893)

In this section, we show that three key processes unfolded in response to the lynching of Italian citizens in 1891: (1) reactions from the Italian embassy immediately forced US presidents to treat lynching as an international relations problem; (2) the lynching of Italians brought unprecedented and sustained attention to American lynching in both the Italian and British presses, which spurred later attention to Black American lynching victims following Ida B. Wells’s British Tour of 1894 and the lynching of George White in 1903; and (3) increased international attention led to domestic newspapers to increasingly describe lynching as “uncivilized.”

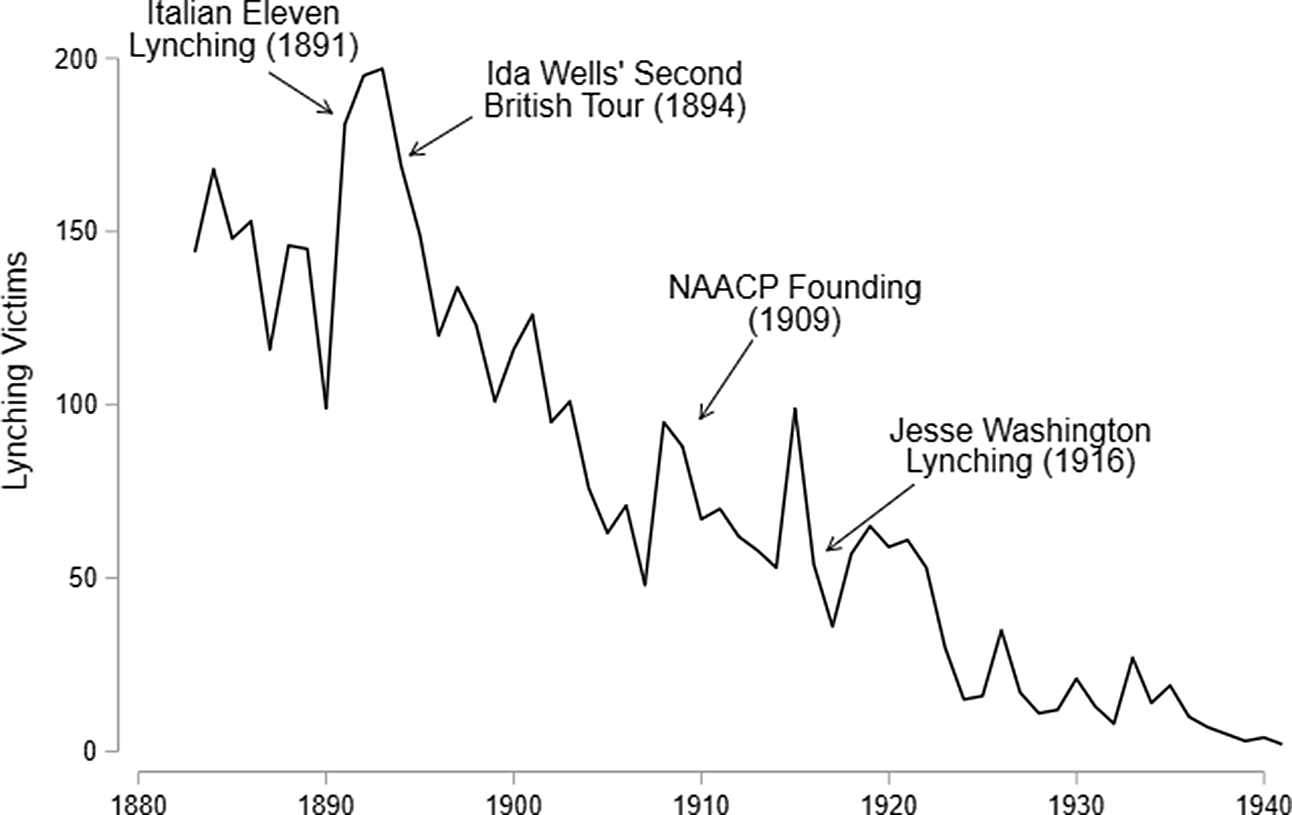

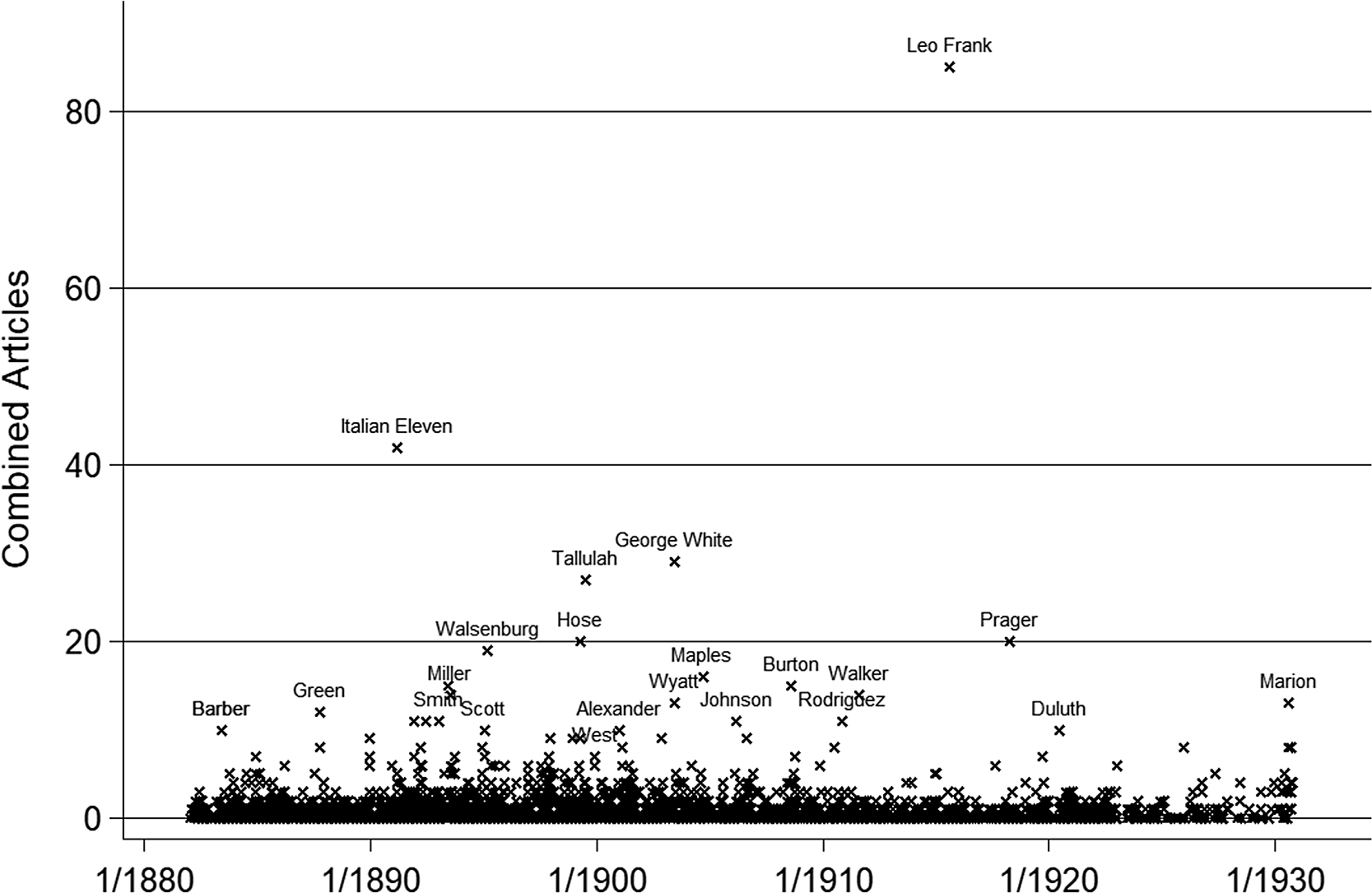

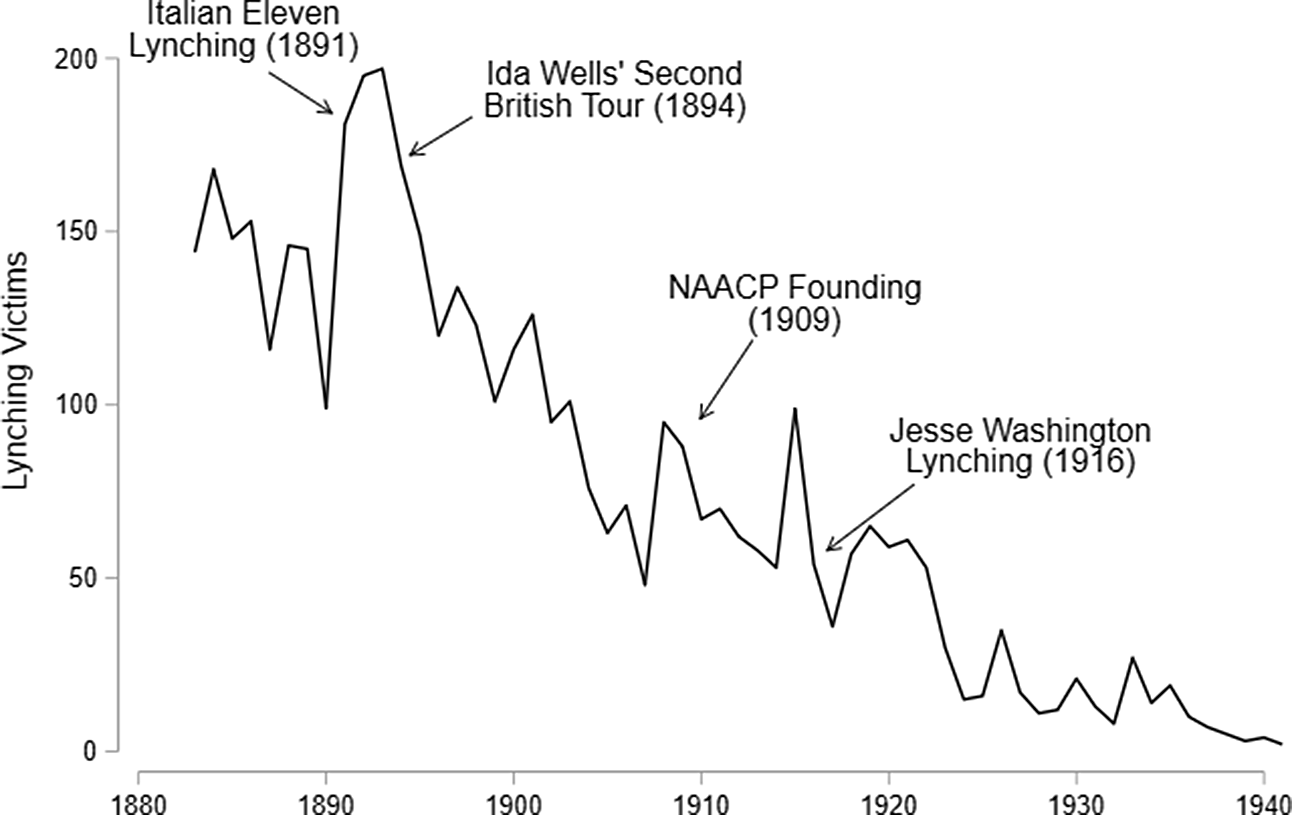

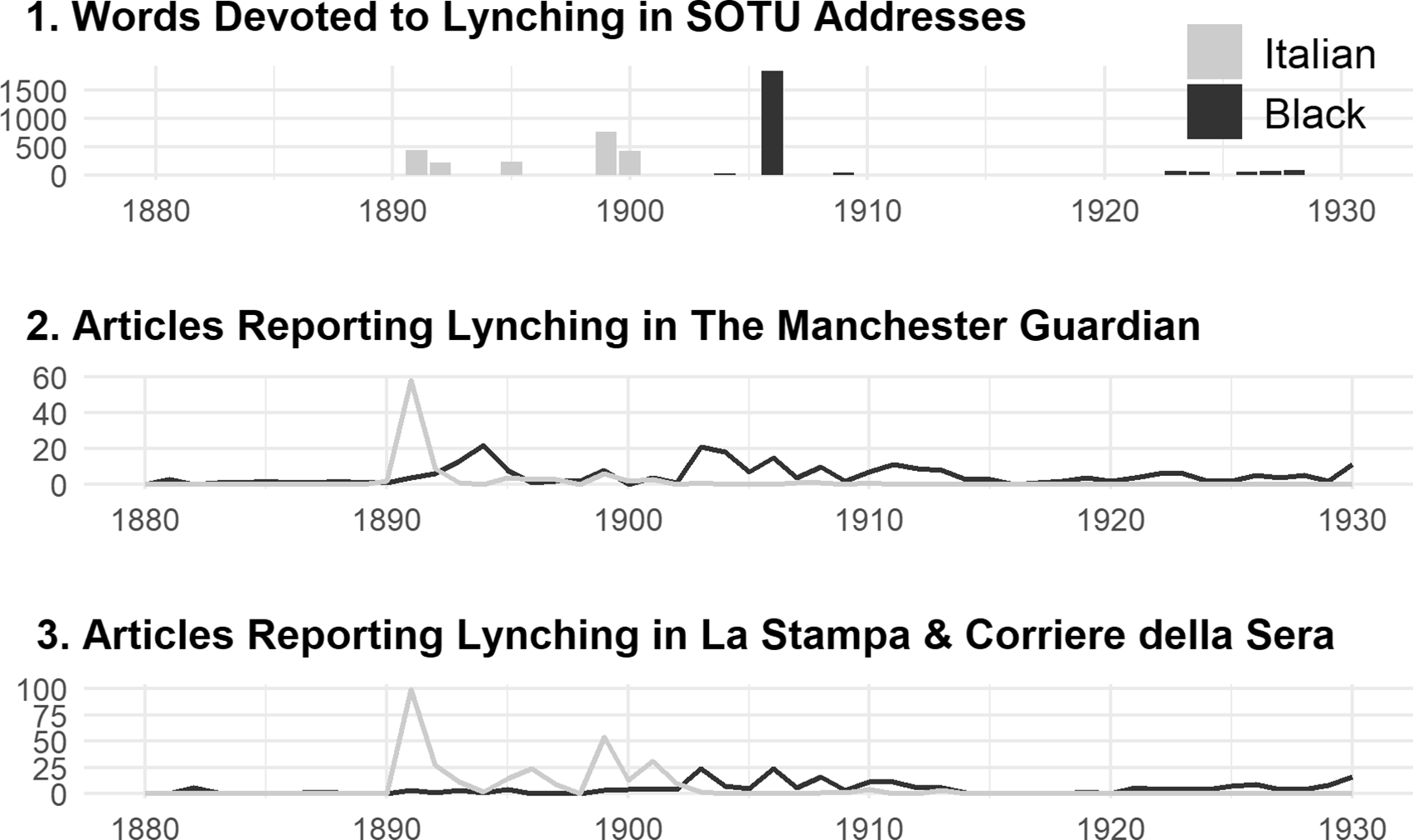

Figure 1 shows trends in total lynchings over this period alongside some key events. Figure 2 shows trends in our data. Panel 1 shows how US presidents began discussing the lynching of Italians in SOTUs starting in 1892. Panels 2 and 3 show how a British newspaper (the Manchester Guardian) and two Italian newspapers (La Stampa and Corriere della Sera) began to discuss the lynching of Italians in the United States in 1891. Figure 3 displays the number of newspaper articles in three US newspapers (The New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and Los Angeles Times) that discuss lynching alongside keywords identifying “civilization discourse.” The frequency of these articles rises dramatically in 1891 and continues at a higher level thereafter.

Figure 1. Key events and the decline of lynching.

Figure 2. Trends in attention to lynching by victim race.

Figure 3. Articles mentioning lynching and “civilization” in American papers.

Note: This figure shows the total number of articles, each year, that were run by the Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and New York Times mentioning “lynching” or “lynched” and one or more of several keywords denoting “civilization discourse.”

Figure 4 shows the combined article count of each lynching victim in the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and the Los Angeles Times. Note that newspapers heavily reported mass lynchings of Italians at New Orleans, Louisiana, Walsenburg, Colorado, and Tallulah, Louisiana. George White, who was lynched in 1903, was the most heavily reported Black lynching victim.

Figure 4. Articles covering lynching victims.

Note: The figure shows articles in the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and Los Angeles Times mentioning lynching victims. Each “x” represents a specific lynching victim, or group of victims in mass lynchings, and how many articles these papers ran on the lynching in the three months following. N = 3,500 articles, N = 3,627 victims.

The Lynching of the Italian Eleven

The Italian Eleven were US residents of Italian descent lynched in New Orleans, Louisiana, on March 14, 1891. Crucially, 3 of the 11 victims were citizens of Italy, and thus covered under mutual protection treaties between Italy and the United States. The Eleven were accused of the murder of the New Orleans police chief, David Hennessy, who had become famous in 1881 for his role in capturing a supposed Mafioso. In October and November 1890, the New York Times and Chicago Tribune ran roughly 30 articles on the Hennessy murder. During the same period, the two papers ran 19 articles mentioning the Mafia, which the newspapers had already constructed as a shadowy and murderous Sicilian criminal organization.Footnote 14 National papers paid considerable attention to the trial of the 19 Italians charged with Hennessey’s murder, nine of which were found innocent or had their cases declared mistrials amid charges of jury tampering.

Following these verdicts, several prominent native White citizens of New Orleans organized a mob that lynched 11 of these men. Three factors coalesced to make this the most infamous lynching of its time. First, Hennessy’s murder, the trial of the men charged with his murder were already a national news stories, so the lynching was naturally reported as a continuation of the story. Second, and ultimately most importantly, the lynching precipitated an international relations crisis.Footnote 15

Shortly after the lynching, northern newspapers tended to express sympathy with the lynch mob, arguing that lynching was the only recourse available considering the perversion of justice by the Mafia (Weber Reference Weber2011: 50). Northern Republican political elites often expressed similar sentiments. Henry Cabot Lodge, for instance, argued that:

whatever the proximate causes of the shocking event at New Orleans may have been, the underlying cause, and the one with which alone the people of the United States can deal, is to be found in the utter carelessness with which we treat immigration to this country. (Lodge Reference Blaine1891: 604)

Unaware of how the political ramifications of the lynching would come to vex him over a decade later as president, Theodore Roosevelt called it “a rather good thing” in a letter to his sister, Anna Cowles (Ziglar Reference Ziglar1988: 15). Thus, because it conformed to justifications centered on the failure of legal justice and Sicilians’ supposed criminality, the lynching did not immediately elicit much domestic criticism.

The Italian Eleven Lynching Strains US–Italian Relations

The United States soon found that the Italian embassy would be a “permanent source of institutional resistance” to the lynching of Italians (Webb Reference Blackett2002: 66). The day after the lynching, the Italian Consul in New Orleans, Pasquale Corte, wrote to the Italian Ambassador in Washington, Baron Saverio Fava. Corte described the lynching as “horrid,” and referred to the mob as “popolaccio,” meaning “the dregs of society” or “riff-raff” (author’s translation). Corte openly denounced the mob and local authorities:

I cannot understand how the most educated part of the citizenry took the lead to commit a murder in such a shameful way. I understand even less how all authorities, municipal, judiciary and administrative, not only did nothing to avoid it, but they knowingly consented to it, if not facilitated and instigated it. (Corte Reference Blaine1891: 6 [author’s translation])

That same day (March 15, 1891), the US Secretary of State, James G. Blaine, sent a confidential communication to Baron Fava. Blaine highlighted the US government’s delicate position and restated the constitutional impossibility of overstepping the legislative autonomy of the state of Louisiana. Blaine assured Fava that he would bring the issue to President Harrison’s attention and send a letter on behalf of the president encouraging the governor of Louisiana to cooperate “in maintaining the obligations of the US toward the Italian subjects” (Blaine Reference Blaine1891: 4). Toward the end of the day, Fava visited Blaine at his home, and Blaine showed Fava a copy of a telegram that Blaine, on behalf of President Harrison, was about to send to the governor of Louisiana and release to the press. The telegraph expressed great regret that the citizens of New Orleans had lynched “three or more subjects of the King of Italy” and that they “had so disparaged the purity and adequacy of their own tribunals” (ibid.: 3). Blaine also confidently repeated multiple times to Fava that the federal government would eventually approve a request of indemnity (Salvetti Reference Salvetti2003: 16). On the same day, the Italian prime minister, Antonio di Rudinì, wrote to Fava, instructing him to ask for “immediate and energetic measures [author’s translation]” to ensure the remaining Italian prisoners’ safety in New Orleans (di Rudinì Reference Blaine1891).

The Italian government demanded the prosecution of the culprits and indemnity for the victims’ families. As the US government hesitated to provide answers, the tension between the two countries escalated, along with the impatience of Prime Minister di Rudinì and the Italian American communities who closely followed the case. The conflict led to a break in diplomatic relations: On March 31, 1891, a little more than two weeks after the lynching, Italy recalled Ambassador Fava and, consequently, the United States recalled their ambassador in Italy, Albert G. Porter (Salvetti Reference Salvetti2003: 22). On May 5, 1891, a New Orleans grand jury found none guilty of the lynching. Corte denounced the verdict in an open letter to the jury foreman, published on May 6, 1891 (ibid.: 25). Corte’s protests brought US officials to the point of demanding that the Italian government take action against him.Footnote 16

The diplomatic crisis concluded only one year later, in the spring of 1892, following ongoing negotiations between the US and Italian governments. Ambassador Fava returned to the United States in April 1892 after the payment of 125,000 francs indemnity to the victims and President Harrison’s explicit condemnation of the New Orleans massacre in the State of the Union on December 9, 1891. It was not until March 1892 that Minister di Rudinì declared his satisfaction and restored normal diplomatic relations between the United States and Italy (Salvetti Reference Salvetti2003: 32).

Thus, although US presidents had ignored hundreds of lynchings of Black victims up to 1891, what was probably only the third lynching of Sicilians (Webb Reference Blackett2002: 47) prompted the first presidential denouncement of lynching in our data. Moreover, after March 1891, presidents also began to prosecute lynchings that occurred under federal jurisdiction. Roughly a month after the lynching in New Orleans, in April 1891, for instance, the lynching of A. J. Hunt by federal troops in Walla Walla, Washington, prompted President Harrison to demand a court of inquiry into the lynching, and seven soldiers were later indicted (Pfeifer Reference Carrigan2004).

Civilization and the Italian Eleven

The lynching of the Italian Eleven shamed the United States before the other White nations that made up, in the imperialist ideology, the “civilized world.” None of these nations were more important than the British. Before 1891, British newspapers occasionally discussed lynching in the United States. Race relations in the US South were also an occasional topic; the London Times, for instance, had sent a correspondent to the American South to do a 10-part series on race relations (Weber Reference Weber2011: 117). However, as figure 2 panel 2 demonstrates, following the lynching of the Italian Eleven, discussion of American lynching in the British papers exploded, and this attention endured at increased levels after that. Similar dynamics occurred in other European newspapers (Casilli Reference Casilli1992: 363) and the Italian press, as shown in figure 2 (panel 3).

Scholars have argued that the framing of lynching in the United States shifted post-1894, following Ida B. Wells’s British tour, toward a characterization of lynching as “barbaric” or “uncivilized” (Bederman Reference Bederman1995; Waldrep Reference Blackett2002). Figure 3 shows results from a systematic search for articles mentioning civilization, barbarism, savagery, and related keywords alongside mentions of lynching. The figure shows such civilization discourse rising in 1891. A close reading of the articles shows that they were specifically framing lynching and lynch mobs—not lynching victims—as uncivilized (see appendix 1 in online supplementary materials).

The year 1891 was also the beginning of a dramatic surge in lynchings (see figure 1), and this surge could potentially explain the rise of civilization discourse applied to lynchings. Three considerations cast doubt on this as a primary explanation, however. First, the surge in civilization language used to describe lynching begins immediately after the Italian Eleven lynching, and most of the articles in 1891 using civilization language refer to the Italian Eleven lynching specifically, suggesting that it, and not a slower-moving rise in lynchings generally, was the initial trigger. Second, such language use drops in 1892 (although it remains at higher levels than pre-1891) and does not peak again until 1899 and 1903 (see figure 3), when overall lynchings had been declining for many years (see figure 1). Third, many of the articles using “civilization discourse” at these peaks in 1899 and 1903 are explicitly about lynchings that, as we show in the following text, were widely condemned internationally: the lynching of Italians at Tallulah in 1899 and the lynching of George White in 1903.

Nevertheless, articles framing lynching as uncivilized immediately after 1891 were not only about Italian victims but also of Blacks. These articles often took a racist stance, even as they condemned lynching. An editorial in April 1892 in the New York Times, for example, argues that Blacks in the South must “submit to political inferiority to the whites” and that “talk of ‘social equality’ was for the most part very aimless.” Nevertheless, the editorial also argued that lynching was proof that the “community which acquiesced in it is sunk in barbarism” and that:

Such an act would be proof of savagery if it were committed by the blacks in Africa or Haiti. It is not less a proof of savagery when it is committed by Whites in Texas. But it is impossible to prevent the commission of such an act or of the lynchings that have been performed and are justified by Southern whites except by raising the standard of civilization in the communities by which they are tolerated. (Anon 1892)

Thus, by 1892 the lynching of Italians (but generally not Blacks) in the United States was a subject of international news, and a new way of talking about lynchings generally, as “uncivilized,” rather than as “rough justice,” was beginning to take hold in the United States. Ida B. Wells would successfully exploit both of these developments in her campaign against lynching.

Ida B. Wells Brings International Attention to the Lynching of Black Americans

In 1891 there was not an organized Black mass-movement against lynching. Although some organizations did exist, such as the Afro-American League, most activism came from a loose network of activists, mostly composed of church leaders, academics, and journalists (Carle Reference Carle2013). John Mitchell, editor of the Black newspaper the Richmond Planet, was a prominent member of this activist network. Following the Italian Eleven lynching in March 1891, Mitchell was quick to see that it could draw attention to the lynching of Black Americans. Mitchell called the Italian Eleven lynching:

a God-send for the Afro-American. It has called the attention of the civilized world to the horrors of American lynch-law, and behind it all lurks the shadows of fifty thousand bleeding negroes who have been its victims. (quoted in Weber Reference Weber2011: 52)

Ida B. Wells, another prominent member of Black activist networks and an ally of Mitchell, began an antilynching campaign in 1892 but had—by her own assessment—made little progress as of 1893 (Giddings Reference Giddings2009: 260). Drawing on old British abolitionist networks, and the endorsement of Frederick Douglass, Wells was invited and traveled to Scotland and England in 1893 and 1894 for speaking tours to bring the lynching of Black Americans to the attention of the British public. Many scholars argue that her 1894 tour catalyzed a shift in the discourse of lynching, in which US newspapers increasingly framed lynching as “uncivilized” or “savage” (e.g., Bederman Reference Bederman1995; Giddings Reference Giddings2009, Waldrep Reference Blackett2002). Contrary to these scholars, our analysis (see figure 3) shows that “civilization discourse” begins in 1891, two years before Wells’s first British tour. Instead, we argue, Wells successfully exploited the international concern about the lynching of Italians to bring international condemnation of the lynching of Blacks (Silkey Reference Beck2015).

Because of the Italian Eleven lynching in 1891 Wells was speaking to Britons “who were already questioning the civilization of the South” (Weber Reference Weber2011: 63). Wells referenced the New Orleans lynching, reminding Britons that even foreign nationals were not exempt from lynch law (Silkey Reference Beck2015:70). Crucially, Wells was informing the British of the lynching of Black Americans, which, our analysis shows, had been mostly missing from British coverage (see figure 2, panel 2). Wells was also calling attention to the increasing cruelty of White mobs. In an interview for the Manchester Guardian in May 1893, for example, Wells noted that lynchings of Blacks were “increasingly barbarous” and that:

The mob are no longer content with shooting and hanging, but now burn negroes alive, and, not satisfied even with that, torture them to death, as in the horrible case at Paris, Texas. (Anon 1892)

A key result of Wells’s tour was the creation of the British Anti-Lynching Committee (BALC). A relatively small organization, membership of the BALC was estimated at 66. Despite its small size, however, BALC membership included 17 members of Parliament, a member of the House of Lords, 7 journalists, and 2 prominent trade unionists (Weber Reference Weber2011: 189–90). BALC conducted investigations of lynchings in the United States and wrote letters directly to US political leaders, and received formal responses from the governors of Georgia, Virginia, and Alabama (ibid.: 193–96). William Lloyd Garrison Jr., writing in November 1894 in defense of Wells and BALC in the Times of London, summarized Wells’s tour thus:

[Wells] found deaf ears to her complaint in the United States. Spoken from the vantage of London, her faintest whisper goes like an arrow to its mark.… A year ago the South derided and resented Northern protests; today it listens, explains, and apologizes for its uncovered cruelties. (Garrison Jr. Reference Garrison1894)

The Guardian’s shift from covering Italian victims after the Italian Eleven lynching toward covering Black victims of US lynching beginning with Wells’s first tour in 1893, also illustrates Wells’s impacts (see figure 2, panel 2). From March 1, 1891 to March 31, 1893, the Guardian ran roughly five times as many articles on Italian victims than Black victims: 67 articles on Italian victims and only 13 on Black victims. From April 1, 1893 to April 31, 1895, the ratios are reversed, with the Guardian running almost seven times as many articles on Black victims than Italians: 34 articles on Black victims and only 5 on Italian victims.Footnote 17 Wells’s role in this shift is also highlighted by the fact that no such change occurs in the Italian newspapers, where there was no similar activist campaign, until 1903 (see figure 2, panel 3). Thus, Wells played a crucial role in exploiting international outrage against the lynching of Italian nationals to bring attention to the lynching of Black Americans.

The Political Response to Additional Lynchings of Italians

Later in the 1890s two lynchings of Italian citizens drew similar political responses to that of 1891. These lynchings occurred in March 1895 in Walsenburg, Colorado, and in July 1899 in Tallulah, Louisiana. Both lynchings were among the most covered of the period (see figure 4). In his 1895 SOTU address, Grover Cleveland mentioned the “deplorable lynching” at Walsenburg that was “naturally followed by international representations” (Cleveland Reference Cleveland1895). Newspapers again used civilization discourse to frame both lynchings. A letter to the editor printed on August 1, 1899 in the New York Times, for instance, proclaimed that: “No class of savages can compete with the work of fiendishness as carried on by a southern mob.” The author also tied the lynching of Italians to the lynching of Black Americans, arguing that: “the negro’s right must be respected as much as the Italian’s” (James Reference James1899). Newspaper coverage immediately anticipated international relations dilemmas following both lynchings. A headline from the Chicago Tribune on July 23, 1899, the day after the lynching in Tallulah, is instructive (note that Count Vinchi is Fava’s representative):

MAY CAUSE A WRANGLE.

________________

lynching of italian’s brought

to government’s notice.

____________

Count Vinchi, Charge d’Affaires, Lays

the Matter Before the State Department—Secretary Hay Calls on the

Governor of Louisiana for the Facts

in the Case—Similar to the Mafia

Killing in New Orleans Several

Years Ago. (Anon 1899)

The US federal government, through the Department of Justice, made a special inquiry into the lynching at Tallulah, overstepping the government of Louisiana’s authority. This was not McKinley’s first federal intervention into lynching: the 1898 lynching of a McKinley-appointed Black postmaster in Lake City, South Carolina, Frazier Baker, had also prompted legal action from the McKinley administration (Fordham Reference Fordham2008: 66–74). However, because the investigation in Tallulah came in response to requests from Fava, it was interpreted as a success of the Italian government’s lobbying. Local intransigence stymied the official inquiry, but, Fava argued, the Tallulah case had demonstrated the necessity of making the lynching of foreign nationals a federal offense to both the US Congress and public (Salvetti Reference Salvetti2003: 33).

In his 1899 SOTU address, McKinley condemned the “recurrence of these distressing manifestations of blind mob fury directed at dependents or natives of a foreign country” and repeated Harrison’s call to make the lynching of foreign nationals a federal offense; he repeated this call again in his 1900 address. Following Tallulah, in response partially to pressure from Fava on Secretary of State John Hay, McKinley supported the adoption of two bills to grant federal courts the authority to rule on international lynching cases, arguing that: “It is our duty to fill the constitutional vacuum that brought us, and could bring us again, to such deadly results,” although the bill was never passed (ibid.: XXXVII).Footnote 18

1903: International and Domestic Condemnation of the Lynching of Blacks

Presidents said little about lynching in 1901 and 1902. McKinley was assassinated in September 1901. Shortly after taking office, Theodore Roosevelt sparked a national controversy, angering White southerners by dining with Booker T. Washington at the White House. Roosevelt coveted White Southerners’ support and was loath to say or do anything that might attract their anger after the reaction to his dinner with Washington (Morris Reference Blackett2002: 57–58). International papers also had relatively little to say about lynching in the United States over these years. Nevertheless, by 1903 conditions were right for a breakthrough in antilynching politics: the lynching of Italians at New Orleans, Walsenburg, and Tallulah had precipitated three major international incidents, and the British had been paying attention to the lynching of Black Americans in earnest since Ida Wells’s tours in 1893 and 1894.

Roosevelt’s desire to avoid angering the White South would soon come into conflict with his international ambitions. In what became known as the “Roosevelt Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, Roosevelt believed that the United States should project military power in the Western Hemisphere and intervene when human rights violations occurred. By 1903 Roosevelt understood that lynching was similar or worse than human rights violations committed abroad and was willing to denounce lynching if it served his international goals. For instance, in a 1902 address at Arlington cemetery, Roosevelt’s first public statement on lynching excused the brutal suppressing of Philippine insurrection. Roosevelt argued that many lynchings in the United States were “infinitely worse” in their cruelty than atrocities committed by American soldiers in the Philippines and asked if there was “anything more disgraceful to civilization in [the United States] than this lynching practice” (quoted in Ziglar Reference Ziglar1988: 17). Although lynchings might be a useful comparison to downplay US brutality in the Philippines, Roosevelt also understood that if the United States were to use human rights violations abroad to justify imperialist actions, lynching made claims of “higher civilization” transparently hypocritical.

In April 1903, a pogrom in the Russian empire brought the tensions between lynching in the United States and Roosevelt’s desire to intervene in human rights violations abroad to a peak. The Kishinev Pogrom (in the capital of present-day Moldova, then a part of the Russian empire) left roughly 50 Jews dead, around 400 injured, and perhaps 10,000 homeless (Schoenberg Reference Schoenberg1974: 262–63). US and international newspapers followed the story closely. The Jewish diaspora in the United States, especially Russian émigrés, mobilized several political elites on their behalf, including former president Grover Cleveland, to pressure Roosevelt and others to denounce the pogrom (Zipperstein Reference Aytaç, Schiumerini and Stokes2018).

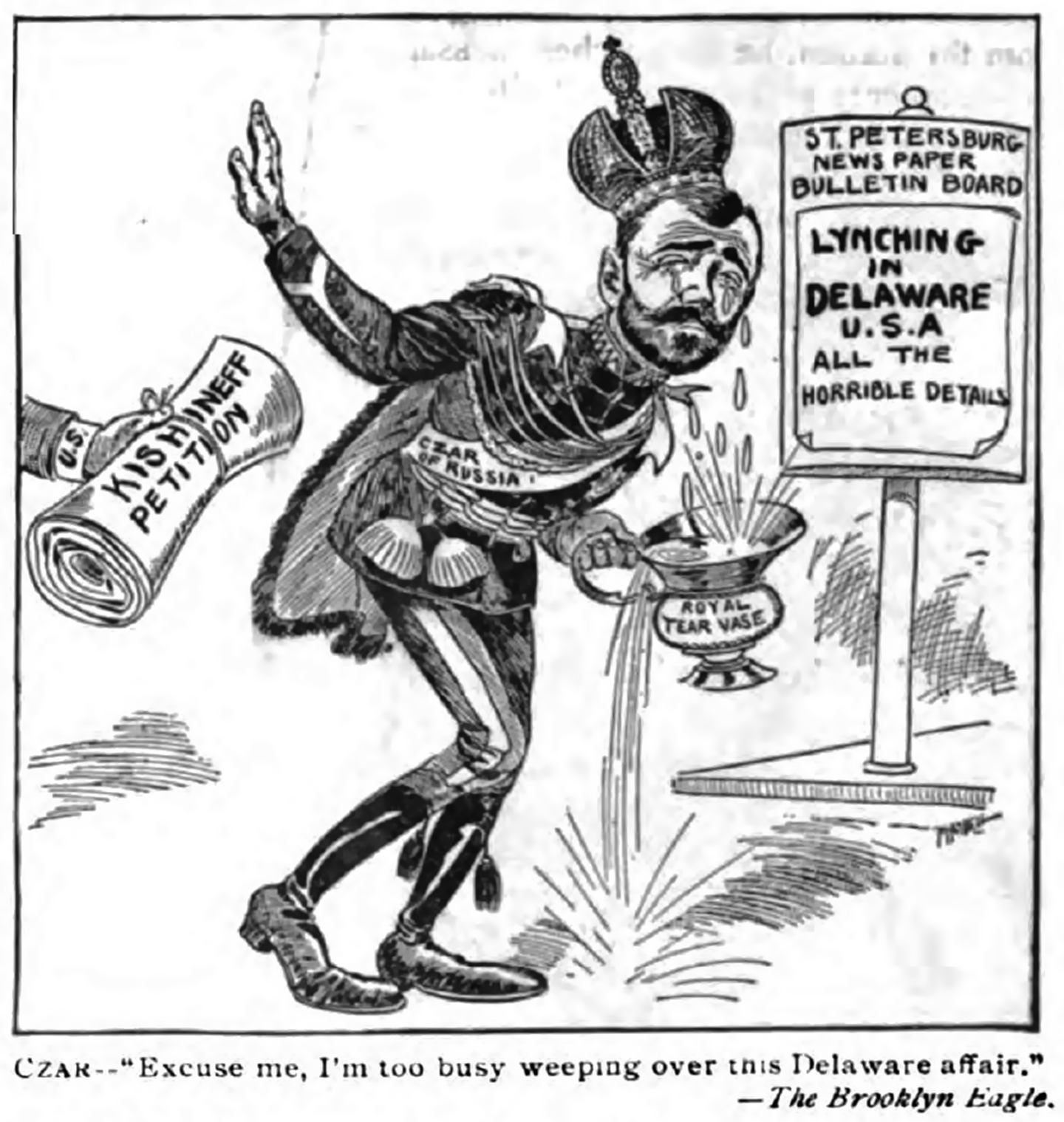

Despite Roosevelt’s desire to condemn the violence, the White House and State Department were silent about Kishinev initially because lynching left them open to similar charges from Russia. Roosevelt’s Secretary of State, John Hay, for instance, wrote in a private letter on May 20, “What would we do if the Government of Russia should protest against mob violence in this country, of which we can hardly open a newspaper without meeting examples” (quoted in: Schoenberg Reference Schoenberg1974: 276). Roosevelt contemplated making a public donation to a Kishinev relief fund but thought it would “be much like the Czar expressing his horror of our lynching negroes” (Roosevelt Reference Keppler1903a). Figure 5 illustrates Roosevelt’s predicament in cartoon form. In July 1903, Roosevelt eventually added his name to a petition denouncing the pogrom, which he had cabled to Russia (Morris Reference Blackett2002: 255–56).

Figure 5. A skeleton of his own.

Source: Keppler 1903.

Note: Notice the word “lynchings” written on the feather in the skeleton’s hat.

On June 22, 1903 during the height of political tensions surrounding the Kishinev pogrom, a Wilmington, Delaware mob lynched a Black man, George White. Despite its political importance, fairly little has been written on the lynching of George White. What we do know is that White had been arrested on charges of the rape and murder of a local White woman. A mob estimated by contemporaries as around five or ten thousand broke White from jail and burned him aliveFootnote 19 (Barrow Reference Barrow2005: 254–56; Downey Reference Carle2013; Williams Reference Davis2001).

The lynching attracted immediate national and international attention. White became the most domestically covered Black lynching victim in our data (see figure 4). Moreover, notice in panels 2 and 3 of figure 2 that attention to Black victims of lynching hits a second peak in the British papers in 1903, while attention to Black victims peaks for the first time in 1903 in the Italian newspapers. Finally, note that the use of civilization discourse displayed in figure 3 peaks again in 1903—this time in the absence of any lynchings of Italians.

The press immediately drew parallels to the lynching of White and the Kishinev Pogrom. Such comparisons were already so widespread just two days after the lynching of White, that the London Times correspondent in New York argued that the comparison had become the standard framing on the lynching, but was not “a just analogy” and that:

This negro’s crime was unspeakably blacker than anything of which the Kishineff Jews were falsely accused, but these are the terms in which the burning of him are denounced. (Anon 1903)

Figure 6 illustrates Roosevelt’s petition denouncing the pogrom being received by Tsar Nicholas, who is weeping over the lynching of George White.

Figure 6. Excuse me, I’m too busy weeping over this Delaware affair.

Note: Originally from The Brooklyn Eagle, reprinted in Literary Digest, July 18, 1903. Taken from Zhuravleva (Reference Andrews and Neal2010: 49).

Newspapers couched their comparisons of the lynching of White to Kishinev in civilization discourse. Three days after the lynching of White, for instance, in an article titled “A BLOT ON OUR CIVILIZATION,” the San Francisco Chronicle wrote:

The frequent lynchings of negroes in the United States will produce in Europe substantially the results which the massacre of Jews in Russia produced in the United States. It will be assumed that only in a community of savages could such occurrences take place. (Anon 1903)

On August 8, 17 days after the lynching of White, Roosevelt sent a widely publicized letter, now known as the “Durbin Letter,” congratulating Indiana Governor Winfield Durbin on suppressing a race riot and, therefore, presumably preventing a lynching. Roosevelt began the letter by “acknowledging” that lynching was motivated by the supposed heinous crimes of Black rapists but went on to frame lynching as a moral blot on the nation in the context of Western civilization:

Where we permit the law to be defied or evaded, whether by rich man or poor man, by black man or white, we are by just so much weakening the bonds of our civilization and increasing the chance of its overthrow and the substitution in its place of a system in which there shall be violent alternations of anarchy and tyranny. (Roosevelt Reference Keppler1903b)

In his 1904 SOTU, Roosevelt returned to the subject of lynching. Roosevelt argued that the United States’ supposedly exemplary human rights record justified intervention in Venezuela, Cuba, Panama, China, and the Russo-Japanese war while acknowledging that the United States’ “worst crime” was lynching. “Thankfully,” Roosevelt argued, lynching was “never more than sporadic,” and, therefore, it was natural that the “nation should desire eagerly to give expression to its horror on an occasion like that of the massacre of the Jews in Kishineff” (Roosevelt Reference Roosevelt1904). During 1905 Roosevelt attempted to repair his relationship with White southerners, largely avoiding questions of lynching and embarking on a well-received tour of the South in which he avoided discussion of Black disfranchisement (Morris Reference Blackett2002: 425). In 1906 Roosevelt devoted some 1,845 words to the subject of lynching in his SOTU—perhaps the most comprehensive statement from a president on lynching. Roosevelt returned to the theme of civilization, arguing that each lynching represented a “loosening of the bands of civilization” (Roosevelt Reference Roosevelt1906).

Moreover, in 1906 Roosevelt’s Justice Department brought charges of contempt of court against a southern sheriff, Joseph Shipp, who had allowed a mob to lynch Ed Johnson, a Black man. Because Johnson’s case was scheduled to appear before the Supreme Court, the lynching fell under federal jurisdiction, and the court sentenced Shipp to 90 days in jail (Curriden and Phillips Reference Curriden and Leroy1999).

Conclusion

Lynching Historiography

In the eight years from 1883 until 1891, although White lynch mobs murdered hundreds of Black Americans, American lynching was rarely discussed outside of the United States, was ignored by US presidents, and was not a point of comparison with other “civilized” nations in the newspapers. All this changed when a mob in New Orleans lynched 11 Italian nationals. Italians, unlike Black Americans, were protected through international treaties and had the backing of a nation-state. Action from the Italian embassy prompted denouncement from other parts of the “civilized world.” This international reaction shifted US (nonsouthern) newspaper framing toward describing lynching as a “barbaric” or “uncivilized” practice, which shamed the United States in front of the “civilized world.” Initially, lynching was an international relations liability for US presidents only when foreign nationals, Italians in particular, were lynched, and presidents began to call for laws making the lynching of foreign nationals a federal offense.

Black activists seized the opportunity afforded by the lynching of Italians. Ida B. Wells exploited the new international attention to the lynching of Italians to draw attention to the lynching of Black Americans in her British Tours in 1893 and 1894. Almost a decade later, international condemnation of the lynching of Blacks reached a peak when it was juxtaposed with the Kishinev pogrom in 1903, prompting Theodore Roosevelt to denounce lynching. This international antilynching pressure placed on US presidents also appears to have led to the prosecution of lynch mobs when they fell under federal jurisdiction. Biographers of Ida B. Wells (e.g., Giddings Reference Giddings2009; Silkey Reference Beck2015) have long pointed to international aspects of lynching politics. Still, much of the literature on the antilynching movement downplays or ignores the role of international political pressure. Such use of international political pressure by Black activists and their allies is a central part of historical understandings of both the abolition and the civil rights movements (e.g., Blackett Reference Blackett2002; Dudziak Reference Dudziak2000). Our article places these international dynamics at the center of the antilynching movement as well.

Existing antilynching historiography has focused mostly on the early NAACP’s efforts to publicize lynchings of Black victims. Much antilynching historiography begins in 1909 with the founding of the NAACP, and the lynching of Jesse Washington in 1916, which was publicized by the NAACP, has become a central case, despite its relative obscurity in our data (Bernstein Reference Barrow2005; Carrigan Reference Carrigan2004: 185; Ming-Francis Reference Ming-Francis2014; Wood Reference Giddings2009: 179). The focus on the NAACP is logical given that most lynching victims were Black and that the NAACP was the preeminent Black organization of the time. We show, however, that it was the lynching of non-Black victims (Italian citizens) and non-NAACP actors (the Italian government and Ida B. Wells), which initially moved American political institutions to act, thus demonstrating the need for scholarship to look to periods before the NAACP’s founding and to actors aside from the NAACP. A full accounting of the NAACP’s impacts is beyond this article’s scope but see appendix 2 (online supplementary materials) for a more detailed discussion. Future historical research should elucidate the connections between the NAACP’s antilynching campaign and this earlier wave of antilynching politics.

Theoretical Implications

Bell (Reference Barrow2005) argues that policy in the United States to alleviate the suffering of Black Americans does not follow from increasing Black suffering, but only occurs when it also benefits many Whites; what he calls an “interest convergence.” In a recent example, Gottschalk shows how, as mass incarceration increasingly targets not only Blacks but also Whites, opposition to mass incarceration has grown among Whites and political elites (2016). We show that most of the early gains by the antilynching movement occurred when international pressure generated by the lynching of Italians and Ida B. Wells’s British tours made it advantageous to Whites who were sensitive to their international reputation to oppose lynching. Work on social movements’ impact shows how movements use tactics like boycotts or protests to impose costs on targets and induce concessions (see, e.g., Biggs and Andrews Reference Beck2015). We show here how movements of a subordinated minority can use sympathy and attention generated by the victimization of more powerful groups to create allies for their own cause, impose costs on their targets, and generate an interest convergence.

Lynching was uncontested by those with political power when groups with little domestic or international political power were the only victims. That systematic violence targets those with less political power is well known, but less understood is when such violence is successfully contested. Many explanations focus on the organization of mass-movements among those targeted (e.g., Morris Reference Morris1986), but organizing is exceedingly difficult under conditions of widespread violent repression such as lynching.Footnote 20 Scholars of social movements have focused on the conditions that lead to the “backfire” of repression (e.g., Hess and Martin Reference Hess and Brian2006), but have largely ignored the racial dimensions of repression and backfire (although see Oliver Reference Oliver2017: 403). Only when lynching violence spilled over to victimize a group (Italians) with more international power did political elites begin to take notice, suggesting that if lynching victimhood had remained more racially segregated, effective resistance to lynching would have been slower to develop.

If opposition to racist violence by nonmarginalized groups is generally is contingent upon failure to maintain strict racial segregation in victimhood, the underlying ethnic power relations or “structure of social cleavages” (Aytaç et al. Reference Aytaç, Schiumerini and Stokes2018: 1221; Wimmer Reference Aytaç, Schiumerini and Stokes2018) may determine the likelihood that opposition emerges. Following this logic, we hypothesize that societies cleanly divided into two groups, with one dominant and the other subordinate, will be the most durably oppressive because it is comparatively simple for dominant groups to segregate repression in these contexts. Consider, for instance, how the sharp racial division of the “one-drop rule,” or hypodescent, was used to create the sharp racial boundaries necessary for Jim Crow segregation (Davis Reference Davis2001: 51–58). Conversely, racist or ethnic violence may be more likely to provoke resistance in places with many cross-cutting ties or identities: in such contexts targeting members of one marginalized demographic risks the victimization of members of more politically powerful overlapping demographics (for a similar argument, see, e.g., Chandra Reference Barrow2005).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2021.43

Acknowledgments

For helpful comments on previous drafts, and other support of this research, we thank Gary Adler, Kenneth Andrews, Christopher Bail, Kenneth Bollen, Robert Braun, Fitzhugh Brundage, Dan DellaPosta, Jennifer Earl, Roger Finke, Brandon Gorman, Carl Jorgensen, Charles Kurzman, Aliza Luft, Tom Maher, John McCarthy, Laura Nelson, Eric Plutzer, Sarah Silkey, and audiences at the University of North Carolina, Stanford University, University of Iowa, University of Arizona, Washington University at St. Louis, University of Pittsburgh, University of Maryland, UCLA, Penn State, the Comparative Historical ASA Mini-Conference in Seattle 2016, and the Social Science History Association Conference 2018. Charles Seguin acknowledges the support of NSF grant number 1435424.