1. Introduction

Any consideration of the isrāʾ narrative, usually translated as Muḥammad's ‘Night Journey’ from Mecca to Jerusalem, must begin by taking account of its ‘one disadvantage’ that ‘none of this was at first glance to be found in the Scripture itself’, as Josef van Ess puts it, with reference to both Q. 17:1 and Q. 53:1–18.Footnote 1 In Ibn Isḥāq's early Sīra narrative, the isrāʾ (based on Q. 17:1) denotes the Prophet's journey in the company of the angel Gabriel to Jerusalem, where he meets Abraham, Moses and Jesus.Footnote 2 The miʿrāj (based on Q. 53:1–18) denotes his ascent to Heaven where he meets many of the same figures, and is given the five daily prayers.Footnote 3 At some point these two narratives were fused.Footnote 4 However, Q. 17:1, the clearest base text for the narrative, is conventionally understood as, ‘Glory be unto He who took His servant on a night journey (asrā bi-ʿabdihi laylan) from the sacred place of prayer (al-masjid al-ḥarām) to the furthest place of prayer (al-masjid al-aqṣā) upon which We have sent down Our blessing, that We might show him some of Our signs. He is the all-hearing, the all-seeing’.Footnote 5 Extensive scholarly discussion has revolved around the identification of al-masjid al-aqṣā with the terrestrial Jerusalem. A number of orientalists have argued that the original Qur'anic isrāʾ was a journey to Heaven, a stance most recently defended by Heribert Busse.Footnote 6 Angelika Neuwirth and Uri Rubin have both argued for a terrestrial understanding of al-masjid al-aqṣā.Footnote 7 The original reception by the Qur'anic audience is obscured by Umayyad-era and later polemic about whether Muḥammad could have had a physical vision of God, according to Josef van Ess.Footnote 8

Absent from the debate, however, is much attention to the etymology of the verb asrā, from which the noun isrāʾ (not itself found in the Qur'an) is derived. Moving away from meanings connected to ‘night travel’ helps partially explain an unsatisfying redundancy in the Arabic that perplexed medieval Muslim exegetes: why is the adverbial laylan (by night) used if asrā itself means ‘to send on a night journey’? Asrā can, however, be elucidated even further based on three sources: the Sabaic inscriptions of South Arabia, early Arabic historiographical usage, and pre-Islamic poetry. Rather than read asrā, a form IV verb, as a transitive form of the form I sarā meaning ‘to travel by night’, it is preferable to read it as a denominal verb derived from sariyya (pl. sarāyā, sarayāt), a military expedition taking place at any time of day or night, thus meaning ‘to send on a royal or military expedition’. The word sariyya is cognate with, and probably derived from, a Sabaic usage found in monumental sixth-century inscriptions of South Arabian monarchs.

The sariyya military expedition forms part of a small cluster of ideological terms that the early Muslim polity inherited from the defunct South Arabian monarchy, just as they inherited religious terms.Footnote 9 Early Muslims did not simply adopt the institution of the sariyya without modification; it was distinguished as an instrument of Prophetic delegation, thus allowing for the relative centralisation of his authority. At the same time, at some point it attained both a proselytising as well as a military role. The sariyya was a ‘mission’, both military and religious.

The sariyya was not the only institution imported from South Arabia, and early Arabic poetry in particular offers a hitherto poorly exploited resource for establishing the cultural and political mechanisms through which the early Islamic Hijaz interacted with South Arabia. Mukhaḍram poets contemporary to the first Muslims depict a worldview in which South Arabian notions of monarchy mixed side-by-side with emergent Islamic notions of Prophetic rule, and they offer a view into some of the military and ideological preoccupations of early Islam that were later discarded.

Early poets may also help us speculate as to the reception of the Qur'anic isrāʾ, if we understand it as God ‘sending the Prophet on a divine sariyya’. This isrāʾ may well have been understood by its contemporaries as a long-distance military expedition of the sort undertaken by South Arabian monarchs or Hijazi tribal leaders. The goal of such an expedition must thus have been understood as the terrestrial Jerusalem, either as a territorial heritage of the early Muslims, or as a backdrop for the Prophet qua folkloric Arabian spiritual hero, supressing the symbol of older religions.

2. Isrāʾ: Problems of Definition in Tafsīr and Qur'anic Usage

The exegetic tradition, from a very early date, presupposes the Sīra narrative of isrāʾ in interpreting the word asrā. This is already the case in the tafsīr of Muqātil ibn Sulaymān (d. 150/767), the earliest completely extant Qur'anic exegetical text. He understands al-masjid al-aqṣā as Jerusalem (bayt al-maqdis), where Muḥammad was prescribed the five prayers, given the opportunity to drink from one of the three rivers (milk, honey, and wine, from which he chose milk), and saw Burāq, his steed.Footnote 10 This led in time to attempts to explain the redundancy of the expression asrā bi-ʿabdihi laylan. Such attempts were initially implicit rather than explicit. Al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/923) relies on a variant attributed to the Companion Ḥudhayfa ibn al-Yamān, min al-layl, to gloss the adverbial laylan, but he does not discuss the issue further.Footnote 11 Al-Zamakhsharī (d. 538/1144), in his al-Khashshāf, returns to this variant in his reading of the verse, and was the first to explicitly pose the question, “If you asked, ‘does not isrāʾ always take place by night, so what then does it mean to mention laylan?”’ He states, “I would respond that laylan, in the indefinite, signifies the short length of the isrāʾ (taqlīl muddat al-isrāʾ), and that He sent him on a forty-night journey from Mecca to Syria in the space of a single portion of the night, thus the use of the indefinite indicates the meaning of portion-ness (al-baʿḍiyya)”.Footnote 12 Al-Zamakhsharī is relying, implicitly, on the variant min al-layl (of the night), which could indeed mean baʿḍ al-layl (part of the night).Footnote 13 In addition to Ḥudhayfa ibn al-Yamān, he cites Ibn Masʿūd as a source for this phrasing. However, neither al-Ṭabarī nor al-Zamakhsharī are interested in the possibility that laylan might offer a different meaning from its variant min al-layl. Moreover, min al-layl could have other meanings, and the Sīra narratives are obviously dictating the interpretation of the Qur'anic text. Nevertheless, al-Zamakhsharī's interpretation became normative, and al-Rāzī (d. 606/1209) and al-Bayḍāwī (d. 685/1286), among others, continued to quote his explanation.Footnote 14

Another inadequacy of these explanations, from an historical point of view, emerges from their atomistic approach, typical of the tafsīr genre. Comparisons are not made across the Qur'anic text, but if one does do so, it becomes evident that the usage of temporal adverbs denoting night with the verb asrā is not consistent with the exegetes’ explanations. Not all usages, after all, can be explained as signifying a swift journey, only taking part of the night. Now, aside from Q. 17:1, asrā appears in five additional places in the Qur'an, in all cases in the imperative. In two identical formulations, Lot is told to flee the impending destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah with the expression asri bi-ahlika bi-qiṭʿin min al-layl (so go forth with your family in a portion of the night).Footnote 15 In three locations, God commands Moses to take the Israelites out of Egypt.Footnote 16 In two of these cases no time is specified, but in one, the setting is night: fa-asri bi-ʿibādī laylan (go forth by night with my servants).Footnote 17

Scholars have noted that perhaps a ‘night journey’ is not the most accurate rendering of isrāʾ. Having surveyed the above passages, John Wansbrough has argued that the original referent of ʿabd in Q. 17:1 was Moses, not Muḥammad.Footnote 18 Angelika Neuwirth, while continuing to read ʿabd as a reference to Muḥammad, sees a translation of ‘exile’ as more compelling than ‘night journey’, especially as in the larger context of Q. 17 the Muslims fearful of being driven from Mecca are implicitly compared favourably with the disobedient Jews driven from Egypt.Footnote 19 In addition to contemporary Western scholars, the medieval lexicographical tradition provides further support for a re-definition of asrā; Abū Isḥāq al-Fārisī (d. after 377/987) explains asrā in this verse as sayyara (he made him travel, he sent him), no doubt suggested by the identical root letters.Footnote 20

There are thus several reasons for rejecting the interpretation of the Qur'an's usage of the verb asrā as ‘to travel by night’. A necessary first step is to examine all instances of Qur'anic usage comparatively. The verb asrā is thus seen to be characterised by several other features. Lot is not really being exiled, per Neuwirth; God is commanding him to avoid catastrophe, and the Qur'an gives no basis for construing his departure as an unjust expulsion in the same vein as the Jews’ exodus from Egypt or the Muslims’ emigration from Mecca. What the passages using the verb asrā have in common is, firstly, that the only subject or speaker to use the verb is divine or supernatural, namely, God or an angel. Secondly, all of the situations are clearly hierarchical. In five out of the six usages, the verb is used in the imperative, and in all of them the subject is either explicitly or implicitly an ʿabd or servant of the divine will. A further hierarchical level exists if we consider Lot or Moses as intermediaries between the divine realm on one hand, and their human kin or the Israelites on the other. The divine command goes out to representatives of human groups who are, in turn, in command over their kin group, be it a tribe or a smaller family unit—the distinction between the two being quantitative rather than qualitative in such social contexts. This then implies a certain socio-political context to the use of the verb, especially in the situation of the Israelites following Moses, who are frequently depicted in a military context in the Qur'an; the Jews under Moses are consistently encouraged to bravely wage war for the Holy Land.Footnote 21 The isrāʾ verse is followed by Q. 17:2–7, which describes the Jewish Scripture's (al-kitāb) foretelling of two Israelite transgressions and two subsequent punishments; for most Biblically literate readers this evokes the destruction of the First Temple by Nebuchadnezzar in 587 bce and the Second by the Romans following the Jewish revolt of 66–70 ce, but most Muslim exegetes saw the cause of the first destruction as the killing of the prophet Zachariah and the precipitating sin of the second the killing of John the Baptist (Yaḥyā ibn Zakariyyāʾ).Footnote 22 In either case, the Jews here are engaged with politico-military forces, albeit against the backdrop of the consistent Biblical and Qur'anic spiritual struggle for monotheistic purity.

A final, grammatical characteristic of the verb asrā in the Qur'an sets it apart from extra-Qur'anic usages, in that it is consistently used transitively with the preposition bi-. This is worth emphasising since asrā bi-hi is evidently distinguishable from the verb asrā, used intransitively and meaning quite clearly ‘to travel by night’, by the use of this preposition. According to the lexicons, there is no difference between asrāhu, where the object is expressed by a pronominal suffix, and asrā bi-hi.Footnote 23 This is a problematic assertion, however, as in this case the bi- must be superfluous (zāʾida), but it is also said that the preposition in asrā bi-hi functions as it does in akhadha bi-l-khiṭām (take hold of the nose-rein), which would typically be considered as expressing close attachment or adherence (ilṣāq)—it is not superfluous.Footnote 24 In fact, asrā in the earliest sources is always intransitive. For example, all three examples given in Lisān al-ʿArab are intransitive: from Labīd we have the expression asrā al-qawmu (the tribe departed in the night), asrat ilay-hi min al-Jawzāʾi sāriyatun (a night-travelling cloud came to him in the night), from al-Nābigha, and the proverbial isrāʾ qunfudh (the night travel of a porcupine).Footnote 25 To all appearances then, the bi- in asrā bi-hi is to make the verb transitive (bāʾ al-taʿdiya), but this construction is typical of Form I verbs, not Form IV. The construction asrā bi-hi is used consistently in all six instances of the verb in the Qur'an, while it is not used at all in the poetic corpus (discussed below), or if it is, with such rarity that the examples would have little evidentiary value. This hints, despite lexicons’ assertions, at differential etymologies for asrā and asrā bi-hi.

As used in the Qur'an, the meaning of ‘night travel’ for the verb asrā is thus untenable. It is used irregularly with adverbs of time denoting night, a redundancy; it is used in hierarchical situations where another dimension of meaning besides nocturnal movement seems to be intended; and its grammatical construction, frequently in the imperative and always with the preposition bāʾ, suggests an idiomatic construction with a specific meaning. The traditional meaning of ‘night travel’, and more particularly the canonical interpretation of ‘in a single night’ for laylan (or rather, for the variant min al-layl), relies on the Prophet's biography. All these considerations argue for seeking another candidate for the meaning of asrā than ‘night travel’, either from Arabic or from another Semitic language.

3. Sariyya: Lexicographical Definitions in Light of Non-Arabic Sources

The term asrā is partially elucidated by a comparison with other Semitic languages. Among the Northwest Semitic languages, the root SRY does not mean ‘to travel by night’, but denotes in all cases, e.g. Hebrew šārā, ‘to loosen’,Footnote 26 a meaning absent from Arabic sarā (SRY), but present in sarā (SRW), as in sarawtu al-thawb ʿannī (I threw off the garment from me).Footnote 27 In Aramaic and its dialects, the meaning of ‘to untie’ leads, through the sense of the motion of unpacking, to the verb šerēʾ (or šerāʾ, šerê) meaning, ‘to encamp, to dwell’.Footnote 28 There is no particular reason to assume that the Qur'anic asrā is derived from SRY rather than SRW, as the distinction would not be manifest in most form IV conjugations. Thus, the Arabic verb asrā (SRW), a denominal form derived from sarāh (the back or highest part of anything, mountains), does not mean ‘to travel by night’, but ‘to travel towards or in the uplands’. At least one commentator has suggested that this may be the meaning of asrā bi-ʿabdhi in Q. 17:1.Footnote 29 For that matter, SRW/Y gives us at least two other Arabic words: sarā (SRW) can also mean ‘to be liberal, generous’, and its Form VIII, istarā, can mean ‘to select the best of something’.

Amongst Arabian Semitic languages, in Safaitic, however, we do find that s¹ry means ‘to travel’ and perhaps even ‘to travel by night,’ although it is only attested twice in the corpus of inscriptions for that language.Footnote 30 In Sabaic there are no other common words from SRW/Y, although s¹r means a valley or wadi.Footnote 31 This could have several etymologies, but sarī, meaning ‘a stream, rivulet’, in Q. 19:24, is a very likely cognate. If this is the case, the root of s¹r could be SRY, and both words related to the Arabic verb yasrī, used of water flowing. A general etymological connection is evident in both Arabian and other Semitic languages: to loosen; to travel; to alight; to travel (by night); to flow; river-valley. Again very generally, this larger context is helpful for realising that reading asrā as ‘night travel’ means passing up numerous other fields of meaning associated with movement. However, a view too wide, or a longue durée approach to a word's meaning lacks historical specificity. If it is possible to read asrā as something other than ‘night travel’, it must be situated within the context of the pre-Islamic Arabian milieu.Footnote 32

Once we abandon assumptions about Muḥammad's night journey, a large number of possibilities present themselves. As we have seen, Neuwirth has suggested ‘exile’, although this is insufficient in explaining all usages in the Qur'an. Two additional possibilities from the medieval Arabic lexicographical tradition have already emerged, that asrā means to travel into the sarāh (highlands), or that it means simply sayyara, or some similar term denoting travel without reference to night. These meanings are not incompatible with the pre-Islamic Arabian milieu. A final, stronger possibility is that asrā is the denominal verb of an as-yet unsuggested noun; the word sariyya suggests itself, as it carries with it notions of hierarchy and command that seem implicit in the Qur'anic usage of asrā, and there is more evidence for its usage in pre-Islamic inscriptional and Arabic texts. Instances of asrā (form IV) meaning ‘to send forth a sariyya’ are admittedly lacking, but sarrā (form II) can mean just that, and form IV asrā could carry the same meaning as its form II, sarrā, as is so often the case with Arabic verbs.

Ironically, medieval lexicographers also struggled to relate the word sariyya, a sort of military expedition, to night travel. This confusion results from the medieval lexicographical strategy of explaining a non-Arabic word with reference to a more well-known Arabic root. Thus in al-Azharī's (d. 380/980) Tahdhīb al-lugha, we find that the sariyya is so named “because it travels by night (tasrī laylan) in secrecy, so as not to give any warning to the enemy, who might then be cautious and avoid it”.Footnote 33 This is etymologically possible, but what little evidence we have suggests that there was no actual relationship between the sariyya and time of day. The earliest texts give examples of sariyya meaning a military expedition taking place during the day. For example, during the battle of Dhāt al-Riqāʿ, al-Wāqidī tells us that the Prophet sent sarāyā that returned at nightfall.Footnote 34 A hadith related by both al-Tirmidhī and Abū Dāwūd on the authority of Ṣakhr ibn Wadāʿa al-Ghāmidī has the Prophet sending all armies and sarāyā at dawn (idhā baʿatha sariyya aw jayshan baʿathahum min awwal al-nahār).Footnote 35 Lane attempts to rationalise these inconsistencies away by supposing that this is the origin of the word, but that it came to be “afterwards applied to such as march by day”, as was the case in later medieval usage.

There are two arguments that could be brought against such a reconstruction based on traditional Arabic lexicography. The first is the Sabaic origin of the word sariyya.Footnote 36 The Sabaic inscriptions were left by monarchs, governors, and other notables of South Arabia, emerging early in the first millennium and continuing until the mid-sixth century ce.Footnote 37 By the sixth century Yemen was controlled by Abraha, a general of Kālēb Ella Aṣbəḥa, the emperor of Aksum, located in present-day Eritrea and northern Ethiopia. Abraha had seized power following a Byzantine-supported Aksumite invasion and subsequently ruled from about 535–565.Footnote 38 While not ethnically South Arabian, Abraha continued to use the inscriptional language and regnal titles of previous Ḥimyarite monarchs, although he replaced the Judeo-monotheistic formulae of the later Ḥimyarites with Christian expressions. He also followed Ḥimyarite practice in attempting to exercise control over the Arabs of the southern and central Arabian Peninsula via a group of Arab client-tribes, many of whom (e.g. Kinda), well-known to the Arabic literary sources, were still present at the advent of Islam. His military campaigns were recalled in a legendary fashion in Q. 105 (Sūrat al-Fīl).Footnote 39 These legends had some basis in reality; one of his inscriptions, Ry 506, dated to 552 ce and located at Murayghān, about half-way between Sanaa and Mecca, offers one such testimonial to the suppression of a tribal group called Maʿadd. Inscriptions disappear after 558 ce, and the literary tradition tells us that the Sasanians exercised loose control over Yemen from the 570s, a state of affairs that prevailed until Islam's appearance.

If we look to one particular inscription, CIH 541, dated from March 548 ce, chiefly commemorating Abraha's rebuilding of the famous Maʾrib dam, we find a cognate and the likely source of the Arabic word sariyya, the Sabaic s¹rwt. CIH 541 records the suppression of a revolt of one Yzd (perhaps as the Arabic Yazīd) bn Kbs2t, who had been named governor (ḫlft) over the Arab tribe of Kinda (Kdt). A larger number of other notables joined in the rebellion, but when Abraha led an expedition himself, Yzd came to him and reaffirmed his allegiance. At this time, news of a breach in the important dam at Maʾrib reached Abraha and he successfully concluded the affair in order to return and oversee repairs, with which the rest of the inscription deals.

In three locations in CIH 541, the word s¹rwt is used.Footnote 40 The word can be rendered several ways, as ‘soldiers’, ‘troops’, or ‘expeditionary force’.Footnote 41 In the first instance, the s¹rwt seem to refer to Ḥimyarite (Ḥmyrm—as opposed to Aksumite) soldiers under the command of two ‘governors’ or ‘generals’ (ḫlyf) named Waṭṭah and ʿAwīdhah.Footnote 42 These troops were sent against the rebels and were sufficiently numerous to lay siege to the rebels’ fortified area, Kadūr.Footnote 43 After submitting, the rebels travelled to Maʾrib in the company of these s¹rwt in order to give their allegiance again to the king. This s¹rwt is the most likely candidate for the etymology of sariyya, rather than ‘night travel’;Footnote 44 it was a large-scale, logistically complex, hierarchical endeavour, and in this case, overseen by a regional monarch and taking place over a wide (ranging between Maʾrib and Ḥaḍramawt) geographical area.

This usage of s¹rwt as a group of soldiers actually accords much more fully with definitions given in some of the lexicographical and historical sources. Based on the inscriptional evidence, if we were to hypothesise about another Arabic word cognate with it, it could be the word sarī (SRW), meaning ‘generous, noble, a chief’.Footnote 45 Perhaps a sariyya then is led by an individual of the sarī rank. There is, unfortunately, no textual or inscriptional evidence for this. Together ḫlyf, s¹rwt forms two modes of deputisation which are strikingly similar to Muḥammad's, who would leave a khalīfa in charge of Medina when he went out on expeditions and put an amīr in charge of a sariyya when he was unable to personally take charge.

The second argument against the reconstructed derivation of sariyya from ‘night travel’ comes from lexicographical sources, where the sariyya is simply a part of an army of a certain significant size, and in fact, there is much more evidence that this is the original sense than any speculative etymological connection with night travel. The lexicon al-Ṣiḥāḥ by al-Jawharī (d. ca. 393/1003) defines sarriya as qiṭʿatun min al-jaysh (a part of an army), stating that the best sariyya is four hundred men.Footnote 46 The number four hundred originates in a hadith, quoted by al-Wāqidī (207/822), that “the best [number] of companions is four men, the best of all sarāyā has four hundred men, and the best of all armies (juyūsh) four thousand”.Footnote 47 In his lexicon al-Muḥkam (458/1066), Ibn Sīdah gives two definitions: that a sariyya ranges from five to three hundred, or that it consists of four hundred horse (khayl).Footnote 48 This is similar to what we might infer from the Sabaic attestations, however, the term sariyya as such has never been adequately explored.

As we have seen, the term asrā in the Qur'an assumes a distinctly hierarchical and perhaps military context. The reading of asrā as a denominal verb meaning ‘to send a sariyya’ is grammatically plausible and should be understood as the best fit for the hierarchical contexts in which the term appears in the Qur'an. A brief survey of the meanings associated with s¹rwt has demonstrated that sariyya originates in South Arabia, and that the original meaning was suited to use by regional monarchs in a strongly hierarchical social milieu. It may not have been the case that this meaning was imported lock, stock, and barrel into Arabic, but the term sariyya has unfortunately never been the object of individual study. An examination of the historiographic texts is therefore necessary to confirm the etymological impressions given thus far.

4. The Sariyya in Early Muslim Historiography

Ella Landau-Tasseron, in an important essay on the pre-conquest Muslim armies, has distinguished several types of warfare, based on strategic and tactical considerations: caravan looting, raids against bedouin, attacks on settled communities, frontal encounters, and defensive warfare.Footnote 49 She points out that it is difficult to discern a linear development among these modes,Footnote 50 but nevertheless, in an examination of Muḥammad's system of delegation, concludes that the expeditions’ command structure was ad hoc and innovative.Footnote 51 She does not therefore extensively analyse pre-Islamic forerunners of the early Muslim military structure, although she does note that early Muslims were urban, and that Qurashī logistical affairs (in contrast to those of the Muslims) are depicted as relatively centralised and sophisticated.Footnote 52

In discussing delegation, Landau-Tasseron neglects to distinguish between two types of expedition named in early historiographical texts, the sariyya and the ghazwa. A further consideration of the distinction between these two types of expedition in early Islamic history and historiography is therefore necessary to elucidate the issue. Both are often rendered as ‘raid’, but they are discussed by early Islamic historians as two distinct types of expedition. The sariyya, in particular, was delegated by Muḥammad to a deputy. Landau-Tasseron's analysis of Muḥammmad's military delegation has recently been further explored in a very comprehensive article by Michael Cook in which he examines whether there is any common stratum of historical reality behind the numerous references to Muḥammad's deputies in Medina during his campaigns in the second- and third-century ah historiographical sources, chiefly al-Wāqidī, Ibn Hishām (d.218/833), and Khalīfa ibn Khayyāṭ (d. 240/854).Footnote 53 Cook provides lists of every deputy mentioned in these sources, and while there is a certain degree of overlap between them in terms of the individuals named, there is wide disagreement regarding which individual was put in charge of Medina during any given expedition. Cook offers two plausible explanations for the disagreement: that at some point (but not at the earliest stage) in the development of Islamic historiography, information about deputies became a generic necessity, thus causing compilers to generate names for each ghazwa that the Prophet participated in; and that the names of some deputies were lost if they lacked powerful or numerous offspring to transmit their deeds. Nevertheless, he argues, “the assumption that the sources do in fact convey to us a significant measure of truth … does not seem unreasonable”,Footnote 54 a point that I agree with.

Our present concern lies not in the deputies themselves but in the terms used for the expeditions: ghazwa and sariyya, which appear to be terminologically different. As we have seen, an etymological difference may have underlain the difference in usage, as sariyya is drawn from the Sabaic s¹rwt. The more common word for a military expedition, ghazwa, is also present in Sabaic inscriptions as ġzt or ġzwt (pl. ġzwy).Footnote 55 However, cognates of ghazwa are found quite widely in other Arabian Semitic languages; it was, for example, also used for raids in Safaitic, indicating that ĠZW is an older and more widely-spread root, and perhaps that its use entered into the sedentary Sabaic language cultures from nomadic Arabian tribes.

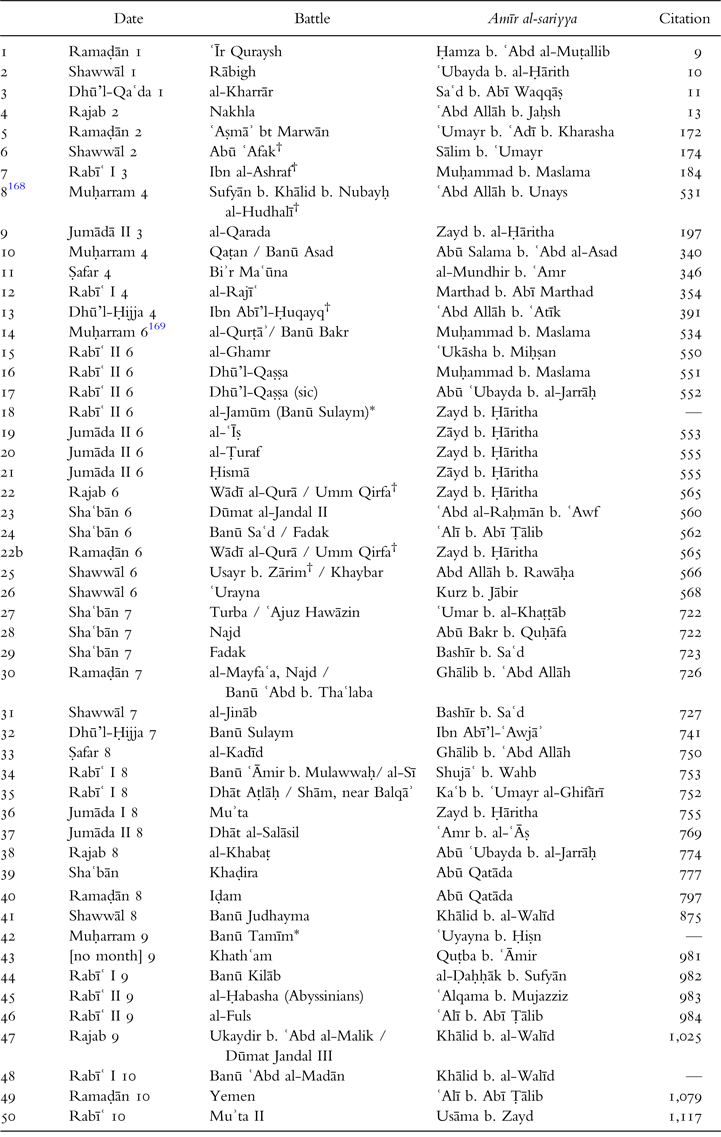

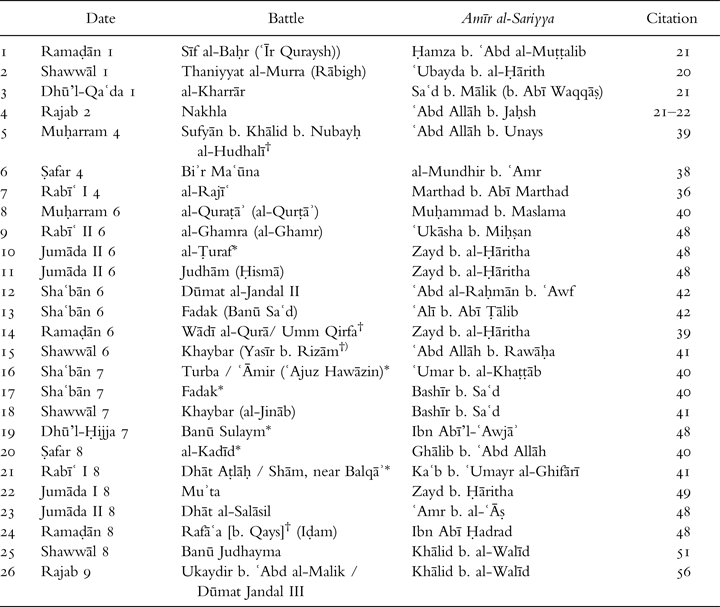

In the Arabic sources, historians clearly felt that ghazwa should be used for raids led personally by the Prophet, while a sariyya was deputised. For example, Ibn Hishām in an appendix to his biography of the Prophet asserts, citing Ibn Isḥāq, that the Prophet led 27 ghazawāt (wa-kāna jamīʿ mā ghazā rasūl Allāh … bi-nafsihi sabʿan wa-ʿishrīn ghazwa).Footnote 56 In contrast, “those expeditions that he sent, and his sarāyā, were 38 in number (wa-kānat buʿūthuhu … wa-sarāyāhu thamāniyan wa-thalāthīn)”.Footnote 57 Al-Wāqidī operates on a similar assumption, although giving some different numbers: the Prophet led 27 ghazawāt (al-ghazawāt … allatī ghazā bi-nafsihi), of which he fought personally in nine.Footnote 58 His sarāyā were 47 in number.Footnote 59 Khalīfa ibn Khayyāṭ does not give a central list of sarāyā, and in fact his text possesses much less information than either al-Wāqidī's or Ibn Hishām's, but his chronicle does feature year-by-year lists of sarāyā, all of which are marked as delegated by the word baʿatha (‘he dispatched’).Footnote 60

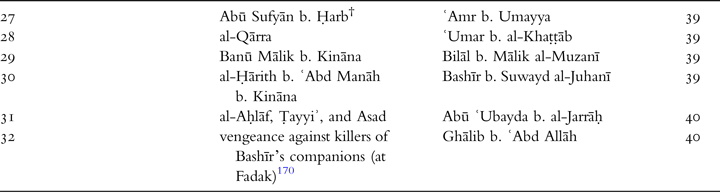

The question emerges, however, as to whether or not these prefatory and summary statements match the historians’ actual documentation of the battles, since there are immediately evident internal inconsistencies. A fuller discussion of this issue is impossible here, but a summary of the consistency of this usage in the three historians Cook makes use of is of some value both in the present discussion, and as a continuation of his research. While Cook in his article lists the dates and locations of expeditions led personally by Muḥammad, along with the personality to whom the oversight of Medina was delegated, we are concerned here with the obverse activity, the expeditions delegated by Muḥammad to a commander while he remained in Medina. Following Cook's methodology, I have taken al-Wāqidī's list of deputised expeditions in the introduction to the Maghāzī as my basis. Following al-Wāqidī's chronological sequence for the sake of convenience,Footnote 61 I give data on the same expeditions as found in Ibn Isḥāq/Ibn Hishām and Khalīfa ibn Khayyāṭ. The complete data is given in Appendix 1 but can be summarised here. There are several issues: the terminology of sarāyā and ghazawāt, and the nature and composition of the sarāyā; the ideological and ritual aspects of delegation; and the identity of the commanders of the delegated expeditions.

The data on the terminology is quite noisy, but the early historians all operate on the assumption that there is a distinction between ghazawāt and sarāyā, and that this distinction is not merely terminological, but rather inherent in their sources. Al-Wāqidī is the most consistent on this point. In his list, despite his count of 47, there are 50 deputised expeditions, 12 of which are termed ghazwa in the list, while 38 are termed sariyya. In the body of his text, 38 are termed sariyya, eight ghazwa, and four have no clear appellation.Footnote 62 Ibn Hishām seems to give almost the opposite impression, in that the term ghazwa predominates in his descriptions of deputised raids. While he asserts that the Prophet delegated 38 expeditions, I count 40. Seven are termed sariyya in the body of the text and 14 are termed ghazwa.Footnote 63 The rest have no specific appellation. This inconsistency may be the result of a lack of terminological rigour; he also uses both terms, sariyya and ghazwa, for at least two expeditions, and two expeditions are termed baʿth (expedition) and one simply masīr (journey).Footnote 64 Crucially though, both Ibn Hishām and al-Wāqidī strictly avoid use of the term sariyya for those expeditions led by the Prophet. Khalīfa's terminology also favours the term sariyya as a term for a delegated expedition, although since he usually simply gives lists without using either term in detailed narrative exposition, his text provides less data.

Al-Wāqidī gives the most information about the composition of the sarāyā. He uses the term for three types of expedition: military offensives, assassinations, and once, a proselytising mission. Khalīfa largely observes the same usage, the logic being that any delegated expedition is a sariyya. Ibn Hishām also observes the same usage in his lists but is not as consistent in the body of his text, describing some assassinations as ghazawāt, for example.Footnote 65

For the purpose of potential comparison with the Qur'anic isrāʾ, the most interesting use of the term sariyya is as a military-cum-missionary activity (indeed, the English term ‘mission’ carries both senses as well). After the conquest of Mecca, al-Wāqidī describes how the Prophet sent Khālid ibn al-Walīd to bring Islam to the nearby tribe of Jadhīma.Footnote 66 When he made contact with them, they asserted that they had already adopted Islam. The various accounts are contradictory, but Khālid clearly felt Jadhīma's professions of faith were some kind of tactical ruse, and thus imprisoned them, and then ordered the prisoners executed. The accounts accordingly emphasise that the sariyya was sent in peace; al-Wāqidī has it that, “the Prophet sent him to Banū Jahdīma, and he sent him to call them unto Islam (dāʿiyan la-hum ilā al-islām), he did not send him for combat (muqātilan)”.Footnote 67 This was, according to Ibn Isḥāq, part of a larger operation: “the Prophet sent sarāyā calling to God Almighty, and he did not command them to engage in combat”.Footnote 68 Many other missions were in fact potentially proselytising, as the Muslims were enjoined to call the enemy to submission to Islam before engaging in hostilities.Footnote 69 As this protocol became normative in Islamic law, we would be right to be on guard for retrojection in the sources. Without assuming that the call to submission was standardised during the Prophet's lifetime, the controversy around Khālid still suggests that the observance of such a protocol was being advocated for from the earliest period.

The act of delegation of command was accompanied by ritual acts. Both Ibn Hishām and al-Wāqidī consider it important to note the first sariyya delegated by the Prophet. This was, according to al-Wāqidī, the sariyya led by the Prophet's uncle, Ḥamza ibn ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib, which intercepted a Qurashī caravan taking the road by the sea from the Levant to Mecca, without, however, engaging in combat.Footnote 70 There were competing accounts, however, for this prestigious claim, and according to other sources followed by Ibn Hishām, ʿUbayda ibn al-Ḥārith, a cousin of the Prophet and early convert, was the first commander of a delegated expedition. He encountered Quraysh at a watering place called Thaniyyat al-Murra, but there was no fighting here either.Footnote 71 Ibn Hishām does also cite a poem put into the mouth of Ḥamza, al-Wāqidī's candidate, about commanding the first expedition.Footnote 72 Both writers, however, depict the command as an honour conveyed by the Prophet accompanied by a bestowal of a banner (Ibn Hishām uses the term rāya,Footnote 73 and al-Wāqidī liwāʾ Footnote 74) that the Prophet ‘bound’ (ʿaqadhā), presumably to a spear, as seen below.Footnote 75

Aside from the liwāʾ or rāya, the headgear (or turban, ʿimāma) of the commander of a sariyya is also sometimes specified. Before leaving on an expedition to Dūmat al-Jandal, the Prophet re-wrapped the black cotton turban of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿAwf so that “about four fingers (in length) hung loose in the back”.Footnote 76 A highly elaborated version of the conferral of the liwāʾ and ʿimāma together are given for the expedition of ʿAlī to Yemen:

the Prophet of God bound his banner for him on that day; he took a turban (ʿimāma) and folded it and refolded it (mathniyyatan murabbaʿatan) and bound it to the head of the spear, and gave it to [ʿAlī] and said, “thus is the banner (al-liwāʾ)”. Then he tied his turban on his head, wrapping it thrice, leaving a cubit (dhirāʿ) [hanging] in front and a span (shibr) behind. Then he said, “thus is the ʿimāma”.Footnote 77

The liwāʾ on the spear represents the authority conferred upon and borne by the leader of the sariyya. The specific manner in which the ʿimāma is folded, with its ends intentionally left hanging, resembles nothing so much as a provincial version of the Hellenistic diadem, “a flat strip of white cloth tied around the head with the ends left loose and hanging”.Footnote 78 Versions of the diadem were adopted throughout the Near East. Among others, the Sasanian kings of kings were prominently depicted with diadems in their rock reliefs.Footnote 79 The Arabic accounts dealing with the ʿimāma perhaps represent later attempts to put a Prophetic imprimatur on an obscure early practice.Footnote 80 For our purposes, the relevant question is whether the tradition represents an early Hijazi practice—not whether it was necessarily Prophetic—and there is no reason to doubt that this was the case.

The commander of a sariyya is invariably called an amīr. The term does not appear as such in the Quran or in early poetry,Footnote 81 and scholars have thus tended to assume that it is an Islamic innovation.Footnote 82 If this is the case, it most likely emerged at a very early stage; the expression is used frequently in hadith where the amīr of a sariyya is described,Footnote 83 and it appears in the earliest Egyptian papyrological evidence (in Greek as amiras) from 22/643,Footnote 84 about ten years after the death of the Prophet. The term could be used for almost any level of military leader, up to provincial leaders, governors, and apparently even the caliph.Footnote 85 It is possible that the command structure of the pre-Islamic sariyya as inherited from South Arabia entailed an amīr, but there is no inscriptional evidence for this.

The term occurs copiously in early historiography and other texts. This is evident, for example, in the formula al-Wāqidī uses multiple times in his list of sarāyā: thumma sariyyat … amīruhā (then the sariyya of such-and-such, its commander so-and-so).Footnote 86 A particularly interesting usage is the term amīr al-muʾminīn (commander of the faithful) for the leader of a sariyya, a term that was later, of course, reserved exclusively for the caliph.Footnote 87 In many passages, al-Wāqidī gives the clear impression that the sariyya by definition was led by a surrogate for the Prophet. For example, Saʿīd ibn Zayd was amīr al-qawm (the commander of the group) until the Prophet arrived, and the phrase amīr al-nabī (the Prophet's commander) appears twice.Footnote 88

There are two points on which the evidence relating to the amīr of the sariyya in early Islamic texts may appear suspiciously consistent: the names of leaders, and the use of the actual term amīr. With regard to the first, the leaders of the sarāyā according to Ibn Hishām, al-Wāqidī, and Khalīfa are exceedingly consistent. As Cook phrases it, “We tend to be suspicious if the sources agree too much or too little with each other—too much because it would suggest interdependence, too little because not enough is corroborated”.Footnote 89 While there are some deviations between al-Wāqidī, Ibn Hishām, and Khalīfa—in particular, Ibn Hishām includes three unique reports of expeditions, and Khalīfa six—for the most part they overwhelmingly agree on the names of the leaders. There is, however, a small quantity of isnād evidence given in Ibn Hishām and al-Wāqidī to cautiously suggest that they were not drawing on the same sources. There are four instances in which both al-Wāqidī and Ibn Hishām give isnāds for sarāyā: al-Wāqidī's expedition nos. 11, 23, 36, and 38. In all but no. 23 (Dūmat al-Jandal II), the isnāds have no common links.Footnote 90

In the case of the deputies put in charge of Medina, Cook supposes that at some point, “the idea emerged that no account of an expedition led by Muḥammad was complete without the identification of his deputy in Medina”.Footnote 91 In that case, the earlier historian Ibn Isḥāq appears to very infrequently (only four out of 27 times) mention the delegated ruler of Medina during Muḥammad's expeditions, while the later historians al-Wāqidī and Ibn Hishām disagree fairly frequently on the leaders but consistently identify someone or other as being in charge. In our case, it seems to be rather that the information on the leaders of delegated expeditions appears earlier; in the case of Ibn Hishām, he directly cites Ibn Isḥāq for 25 out of 41 expedition leaders.Footnote 92 If the data on the leaders is accurate, we can conclude that, unlike the information on the deputies put in charge of Medina described by Cook, the Islamic community recorded the names of the leaders of deputised military expeditions at an earlier point. It might also more tentatively be posited that this information is more likely to be accurate than the names of deputies in charge of Medina.

There is however, a growth or increasing consistency over time in the use of the term amīr. I only find two instances in all of Ibn Hishām where the term is used.Footnote 93 It is quite possible that while accurate information on the leader of the sarāyā was recorded at an early date, and enough evidence points to the Prophet clearly delegating the role to his subordinates, the terminology in historiographic texts became more consistent with time. It is curious that while the Egyptian papyrological evidence shows the term had widespread currency, it is not used by the Baghdad-based Ibn Isḥāq. Perhaps there were regional differences in early usage.

In sum, the solidity of an early stratum of real records on the sarāyā is somewhat more convincing than in the case with Cook's subject, the delegated governorship of Medina. It is worth noting, in passing, that Cook concludes that the term khalīfa for the ‘governor’ of Medina is earlier than ʿāmil; khalīfa, like sariyya, has a Sabaic cognate.Footnote 94 As noted above, cognates of these two terms appear in close proximity in cih 541, implying that Muhammad's system of delegation had something in common with that used by Abraha.Footnote 95 As far as the sariyya is concerned, there is a fair degree of uniformity with regard to its being a delegated expedition, and with regard to the names of the leaders involved. Early historians do not seem to have been drawing on the same sources for this information, and they also debate with each other over significant ritual acts: the liwāʾ or rāya, the rumḥ, and the ʿimāma. In both places, they were probably drawing on earlier material. They almost certainly did so with regard to nomenclature, particularly in using the term sariyya and even more so with regard to amīr.

The sariyya then, as it was brought into early Islamic governance, entailed a ritualised system for delegating authority. This system does not appear to have existed in nomadic Arabian culture, and the nearest sedentary polity on which the early Muslims could have drawn was Ḥimyar. Although numbers are unreliable, these expeditions could have been larger, up to 3,000 men, and long-range, reflecting political concerns akin to those of the South Arabian monarchs. Early Muslims modified the sariyya for their own ideological needs, endowing the military ‘mission’ with a proselytising function that was undoubtedly messier in early practice than in later theory.

The sariyya was thus central to early Islam. Muslims adapted an institution of regional royal power and remade it as a vehicle for Prophetic authority and military hierarchy in an otherwise relatively egalitarian community, and an instrument of an idealistic ‘foreign policy’ of missionising/conquest.Footnote 96 It is by no means arbitrary then, that although it does not appear as a noun in the Qur'an, it should underlie the verb asrā. It only remains to demonstrate that there is significant further evidence, in the form of poetry corroborated by inscriptional usage, for such ideological borrowings from South Arabia.

5. Ḥimyar Revisited: Poetic Connections between the Hijaz and Yemen

The relationship between the early Muslim Arabians of the Hijaz and South Arabia has already drawn extensive scholarly attention, most of it revolving around a few key topics such as the massacre at Najrān in the year 523 ce or the so-called expedition of the Elephant connected to Q. 105.Footnote 97 To a large extent, concern for these topics has revolved around their inherent interest as sources of influence on early Islam, that is, they are viewed through the lens of religious developments.Footnote 98 Scholars have generally been swift to suppose that epigraphic evidence might shed light on obscure areas of the Qur'an's text,Footnote 99 but there has been less analysis of the political influence of the South Arabian polity on the early Islamic state.

Yet some degree of political influence must also have occurred. Christian Robin has argued consistently for a very strong reading of South Arabia's influence on Arabia Deserta, including the Hijaz. Abraha left inscriptions describing his dominance of local Arabs in Murayghān, about halfway between Sanaa and Mecca. In this he was continuing earlier incursions by the Ḥimyarite monarchs, dating back at least to the mid-fifth century. These inscriptions describe the suppression of the tribal confederations of the Maʿadd and Muḍar.

What were the mechanisms of South Arabian influence on the Arabs of the peninsula? The mid-fifth century ce Ry 509, at Maʾsal al-Jumḥ, is approximately 1,000 km north of Ẓafār, the Ḥimyarite capital, yet carefully describes the military equipage that the kings travelled with—lower ranking noblemen (qwl, pl. ʾqwl; Arabic qayl, pl. aqyāl), some sort of equestrian corps (ṣyd), officials and tributary Arab tribes. As Robin points out, “a document that describes the peaceful movement of all the accoutrements of royal pomp, without mentioning any other power, implies Ḥimyar's political domination of the region”.Footnote 100 We can imagine the impression that such a spectacle would have made on Arabian tribesmen. And yet, in contrast to the fairly copious information preserved in the Arabo-Islamic literary tradition on Kinda and the Ḥujrids, there seems to be little awareness of Ḥimyarite power amongst the Arabs, a fact that Robin himself notes.Footnote 101

In fact, on several points, it is difficult to say with much precision anything about Kinda's relationship with Ḥimyar. Although the Ḥimyarites were Jewish (or more precisely, Judaising monotheists), less is known about Kinda's religious affiliations—although at least some members of the tribe were likely also Jewish.Footnote 102 While inscriptional evidence confirms, as found in the Arabo-Islamic tradition, that the Ḥujrids claimed kingship for themselves,Footnote 103 Ḥimyar did not actually grant this title, and we are left to speculate about the Ḥujrids’ actual political duties, perhaps as tax-collectors.Footnote 104 It is often asserted that Kinda's capital was Qaryat al-Fāw,Footnote 105 but this rests on inscriptions found in southern Arabia testifying to South Arabian monarchs’ attacks on ‘Qryt dht-Khlm’, associated with Qaryat al-Fāw by its excavator, A. R. al-Ansary.Footnote 106 Kinda is mentioned in connection to the region, but it is far from clear that Qaryat al-Fāw functioned as their ‘capital’. The findings at Qaryat al-Fāw are outstanding and are still not well-enough known, but all that can be said with certainty linking the site with Kinda is that there is some kind of relationship.

Because several inscriptions have been found at Maʾsal al-Jumḥ, Robin speculates that this was the “seat of Ḥimyar's power in central Arabia”,Footnote 107 and that it was perhaps the site of pilgrimage or markets.Footnote 108 Again here, there is little evidence of any awareness of the site in the Arabo-Islamic tradition. Robin asserts that Maʾsal al-Jumḥ's “strong symbolic power” is confirmed by its appearance several times in pre-Islamic poetry.Footnote 109 This is not at all the case; rather, the term ‘Maʾsal’ (the term appears on its own, which already weakens its association with Maʾsal al-Jumḥ) appears in conventional lines of poetry that list place names with little specificity. Al-Namir ibn Tawlib, for example, opens a poem, as so many poets do, bemoaning the dereliction of the former abodes (aṭlāl) of his beloved, Jamra, which entails naming them:

Labīd, in ubi sunt mode, describes how death comes for every created thing, no matter where it dwells, even in mountainous redoubts:

Pre-Islamic poetry is replete with such toponyms; they almost certainly represented real places, but great care must be taken in locating them precisely.Footnote 112 In both of these instances of Maʾsal's usage, for example, the poem rhymes in lām, which perhaps dictates the particular toponyms mentioned.

Robin is, however, certainly correct to look for the influence of South Arabian modes of rule on tribal Arabia and, by extension, early Muslims, urban Hijazis as they were (rather than nomadic pastoralists). There are several terms from Sabaic that made their way into Arabic, most likely reflecting an actual exchange between the two cultures. Setting aside the numerous cognates in religious language, several early Arabic political and military terms have Sabaic cognates. Sariyya and s¹rwt have already been extensively discussed, and, in passing, we have seen that cih 541 uses the term ḫlft for a ‘governor’ or some such subordinate ruler, evidently cognate with Arabic khalīfa; this governor was normally a vassal from within Kinda.Footnote 113

Other examples are worth citing; Sabaic ḫms1 meaning ‘the main force of an army’ is cognate with the Arabic khamīs, meaning ‘army’, which medieval lexicographers strove to relate to ‘five’ (ḪMS); Sabaic mṣnʿt meaning ‘fortification’ is found in Q. 26.129, ‘Do you build fortresses (maṣāniʿ) because you hope to be immortal?’; the term for nomads used by (urban) Muslims, Aʿrāb, has a long history, but seems to be cognate with Sabaic ʾʿrb.Footnote 114 These people are constantly spoken of derisively in the Qur'an, indicating that the sedentary Hijazis and South Arabians viewed them similarly.Footnote 115 The lexical borrowings from South Arabia are in all likelihood more extensive than from any other Semitic source. Martin Zammit has noted that the number of Qur'anic cognates with terms found exclusively in South Semitic (8.9% of the Qur'anic corpus) almost equals those of purely Northwest Semitic usage (9.4%), which is “particularly significant given that the lexical evidence available from this area of Semitic is no match for the extensive lexical resources available in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Syriac”.Footnote 116

Very few Sabaic cognates of the sort discussed occur with any frequency in pre-Islamic poetry, nomadic (or pseudo-nomadic) as it is, leading one to suppose that they were part of the vocabulary of urban Arabians, reflecting a more cosmopolitan interaction with sedentary South Arabia. However, in order to demonstrate the influence of South Arabian culture on Arabia Deserta, poetic evidence is helpful, drawing frequently as it does on lines of transmission very different from the prose accounts of pre-Islamic lore. Three examples are relevant to our discussion: on the usage of sariyya in poetic texts; an instance of a military conflict between Hijazi tribes and Ḥimyarite client-tribes named in inscriptions; and most significantly, an instance of South Arabian titulature found in a poem in praise of the Prophet.

The poetic tradition makes use of other words derived from the root SRY that clearly have to do with night travel.Footnote 117 The word al-sārī (night traveller) is used quite often and is invoked most frequently as the object of hospitality. Al-Nābigha, for example, boasts that he camps in the open, where his fire is visible to any guest, as evidence of his wealth and generosity.Footnote 118 When a poet wishes to boast about his own night travel, however, the verbal noun for night travel (al-surā) is used, most often projected onto the speaker's weary but persevering camel. Suwayd ibn Abī Kāhil al-Yashkurī, for example, describes his camels as “[emaciated] as thin arrows, experienced in night travel (ʿārifātin li-l-surā)”.Footnote 119 Although these examples are by no means exhaustive, usage of the terms al-sārī and al-sūrā are largely confined to these themes, both of which are relatively common, thus prohibiting extensive analysis here.

On the other hand, the verb asrā and the noun sariyya are extremely uncommon in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry. The usage of asrā is virtually restricted to the line of Labīd cited in lexicons, and which is indeed also found in his dīwān. When it does appear it is intransitive and means ‘to travel by night’, and I can find no example of asrā bi-hi. The word sariyya barely occurs in canonical anthologies of early Arabic poetry. It is absent from the Mufaḍḍaliyyāt of al-Mufaḍḍal al-Ḍabbī (d. 163/780), al-Aʿlam al-Shantamarī's (d. 476/1083) collection Al-Shuʿarāʾ al-sitta al-jāhiliyyūn, and the poetry of the Hudhayl tribe compiled by Abū Saʿīd al-Sukkarī (d. 275/888), Ashʿār al-Hudhaliyyīn. Since the terms sariyya and asrā (bi-hi) are quite common in the Qur'an and in early Islamic historiography, we can conclude tentatively that they are reflective of urban Hijazi usage rather than that of the semi- and pseudo-nomadic tribal elites of Najd and the Hijaz who produced the bulk of extant poetry.

The noun sariyya occurs relatively conclusively in only two early poetic texts that I have been able to locate. In both cases the plural form sarāyā is used. In ʿAntara, the speaker's enemies are described as fighting in sarāyā:

The term sariyya appears to be synonymous with katība, a word which denotes a larger-scale military expedition. The sarāyā are not associated here either with small-scale raiding, or with night travel. As in al-Wāqidī, the groups are designated by a liwāʾ, a term which in this context indicates a tribal grouping's banner. Labīd compares the bray of an onager to the scream of a leader fearing sarāyā and unexpected attack (ightiyāl).Footnote 121 Here too, the point seems to be that the onager is hoarse, as a man screaming in the midst of a particularly extensive battle, indicated by the use of the term sarāyā.

There are several other texts of less certain authenticity or transmission where the word sariyya occurs. While little can be concluded from these usages, there does seem to be a trend of tribes associated geographically (i.e. they inhabited the southern Hijaz) or politically with early Muslims to use the term. In an elegy for her brother, Suʿdā bint Shamardal (Juhayna) calls him hādī sariyyatin (the guide of the sariyya).Footnote 122 Khufāf ibn Nadba, or Nudba, (Sulaym) laments the death of Ṣakhr and Muʿāwiya, the brothers of the poetess al-Khansāʾ; Ṣakhr was “abandoned to the sariyya (li-l-sariyyati ghādarūhu)”.Footnote 123 An almost certainly inauthentic lament for al-Muṭṭalib, the brother of the Prophet's paternal grandfather ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib, attributed tentatively by Ibn Hishām to Maṭrūd ibn Kaʿb (Khuzāʿa) describes the Hashimites as “ornaments of the sarāyā’”.Footnote 124 A poem by al-ʿAbbās ibn Mirdās (Sulaym) refers to the sarāyā of which the Prophet of God is the amīr.Footnote 125 This usage, of course, contrasts strongly with the amīr as the leader delegated by the Prophet that we have seen already. Finally, Taʾabaṭṭa Sharran (Fahm), puts a boastful self-description into the mouth of one Umm Mālik, who sees him and his companions “dishevelled and dust-covered after a sariyya”.Footnote 126

These are not a particularly reliable set of citations. Of these five instances, those of Suʿdā, Khufāf, and Taʾabbaṭa Sharran rely on variant readings, while the poems of Maṭrūd and al-ʿAbbās ibn Mirdās (and perhaps the folkloric Taʾabaṭṭa Sharran as well) are probably inauthentic. Taken in addition to the two lines by Labīd and ʿAntara, we have in total seven instances of sariyya being used in poetry and the data perhaps has some collective value. There is a noteworthy tribal distribution; with the exception of ʿAntara, all of the poets hail from tribes that are either southern Hijazi (Sulaym, Juhayna, Fahm, Khuzāʿa) or who directly interacted with the early Muslims (as did Labīd, who reportedly converted). Particularly prominent are poets connected to the tribe of Sulaym ibn Manṣūr; Suʿdā, although of Juhayna, laments her brother killed by a Sulamī, while al-ʿAbbās is Sulamī himself, as is Khufāf. Three of the texts are from elegies and bear some similarity to the style of the Sulamiyya al-Khansāʾ, and indeed, al-ʿAbbās was said to be al-Khansāʾ's son,Footnote 127 and Khufāf her cousin.Footnote 128 Even if the poems represent distorted oral traditions or outright forgeries, the overall tone of these texts could reflect a historical kernel. Taken collectively, these citations seem to support the entrance of the word sariyya into Arabic via a Hijazi adoption of the South Arabian term.

Two further examples of interaction between South Arabia and the Hijaz more fully confirm the strength of interaction. One example is military. Aṣmaʿiyya no. 70, by al-ʿAbbās ibn Mirdās, records a long-range feud between his tribe Sulaym, who, as we have seen, made the most use of the term sariyya in the poetic tradition, and a clan called Zubayd, which dwelt somewhere far to the south of Mecca. The relevant portion of the poem is:

The names are initially obscure, but the overall context is clear. The speaker is leading a long-distance expedition, and he gives the distance in terms of nights travelled. This method of reckoning (counting nights rather than days) appears to be the same as we find in early Islamic historiography, both for lunar month dating and for military expedition distance and is not necessarily related to ‘night travel’, as is evident from his description of the chameleon, which proverbially stares at the sun, and is a stock feature of scorched desert landscapes. The expedition is heavily armed and includes horse-mounted cavalry and the use of (expensive) armour. The scale of such an undertaking indicates a political conflict, rather than local concerns over bloodwit or pasture.

A prose summary of the expedition is given by Abū al-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī in the Kitāb al-Aghānī, on the authority of Abū ʿUbayda Maʿmar ibn al-Muthannā (d. ca. 210/825).Footnote 132 Abū’l-Faraj's use of isnāds is not always rigorous,Footnote 133 but his account from Abū ʿUbayda has a ring of authenticity. He identifies the tribe attacked as a southern or Yemeni one, namely, Murād, even though they are not directly named in the text of the poem. ʿAmr ibn Maʿdīkarib was said to have responded to al-ʿAbbās's poem.Footnote 134 ʿAmr does not belong to Murād, but he does belong to its sister tribe, Saʿd al-ʿAshīra.Footnote 135 Abū al-Faraj does not quote the entirety of al-ʿAbbās's poem, as he states that only the beginning is sung, and therefore the rest is not of interest.Footnote 136 He does not quote from ʿAmr ibn Maʿdīkarib at all, although he gives the location of the battle as ‘Tathlīth, in Yemen’, a southern site according well with a battle with Murād or Saʿd al-ʿAshīra. All of this gives the air of an editor transmitting genuinely received material, the content of which he is uninterested in altering or distorting.

ʿAmr ibn Maʿdīkarib's text confirms (or is the source of) the battle location as Tathlīth, and his poem survives as citations in disparate sources, one of which is Abū ʿUbayd al-Bakrī's (d. 487/1094) geographical dictionary, Muʿjam mā istaʿjam, in the entry on ‘Tathlīth’. Al-Bakrī quotes al-Hamdānī (d. 334/945) as stating that Tathlīth lies three and a half stages (marāḥil) to the north of Najrān, and as belonging to Banū Zubayd, ʿAmr ibn Maʿdīkarib's clan.Footnote 137 The geographer Yāqūt states that the site is mentioned numerous times elsewhere in the Arabic poetic tradition as a location of battles.Footnote 138 It is not, thus, in Yemen, as Abū al-Faraj asserts, but apparently near present-day Tathlīth governorate (muḥāfaẓa) in Saudi Arabia, about 500 km southwest of Mecca and 300 km to the north of Najrān. In the text cited by al-Bakrī, two lines are given:

This text, of which only two lines are given, was clearly composed in response to al-ʿAbbās's poem. As a muʿāraḍa, both are written in the same rhyme (-(i)sā) and meter (al-ṭawīl). ʿAmr's poem addresses al-ʿAbbās directly and gives the placename of Tathlīth. Without relying on al-Hamdānī, it is identified internally as near Ṣaʿda, in the northwest of present-day Yemen (about 350 km south of Tathlīth). Such a location, distant from Sulaym's territory, accords with the long-distance journey described by al-ʿAbbās (Tathlīth is about 900 km south-southeast of Medina). Finally, the authorship of ʿAmr or someone from his tribe is tentatively confirmed by a line, cited elsewhere but evidently originating in the same poem, mentioning ‘banī ʿUṣm’, another ancestral clan of ʿAmr.Footnote 140

Given all these details in multiple sources, there is little reason to doubt the general outline of the narrative of Abū ʿUbayda/ Abū al-Faraj in explication of al-ʿAbbās and ʿAmr's poems. Further confirmation of their pre-Islamic content comes from several important South Arabian inscriptions. To begin with, ʿAmr's father bears the name of South Arabian nobility—Maʿdīkarib—indicating that his tribe was not only a military client, but culturally influenced by South Arabia. For example, Madhḥij, which according to classical genealogical handbooks was the father-tribe of ʿAmr's tribe Saʿd al-ʿAshīra, is mentioned as supporting the Ḥimyarite king Maʿdīkarib Yaʿfur on a military expedition commemorated in an inscription at Maʾsal al-Jumḥ, Ry 510, dated to 521.Footnote 141 Murād, Saʿd, and Madhḥij are all mentioned as military clients of South Arabian monarchs, sometimes in inscriptions found in the area dealt with in the poems. Ja 1028, for example, deals with the events connected to the massacre at Najrān in 523 CE, and is located 90 km north-northeast of Najrān, almost midway between it and Tathlīth. Both Madhḥij and Murād (inscriptional Mḏḥgm and Mrdm) are mentioned there supporting the Ḥimyarite noble Sharaḥʾīl Yaqbul dhu-Yazʾan in retaking control of Najrān.Footnote 142

The most striking appearance of these tribes, however, is that of Saʿd (generally understood as Saʿd al-ʿAshīra) and Murād together in Ry 506, dated to 552, in which Abraha commemorates his victories in Arabia Deserta, with Saʿd among his vassals. This inscription was found at Murayghān, about 20 km from present-day Tathlīth, lending historical credibility and a sense of the political stakes at play to the fight at Tathlīth between al-ʿAbbās and ʿAmr. Given that Yāqūt mentions that numerous battles in the ‘Ayyām al-ʿArab’ tradition took place at Tathlīth, it thus very much appears that al-ʿAbbās and ʿAmr were continuing the long-distance feud instigated by Abraha's incursions into Arabia Deserta, and that warfare between two groupings of tribes, Hijazi and Yemeni, continued for some time around this strategic site.

We have, then, one model by which cultural interaction continued to take place in the early sixth century at the time of Islam's emergence. The poems of al-ʿAbbās ibn Mirdās and ʿAmr ibn Maʿdīkarib indicate not only that the client-tribes of the South Arabian monarchy continued to inhabit approximately the same territory as in the early-sixth century, but that South Arabian culture continued to influence them, and that military conflicts continued to take place between South Arabia and the Hijaz. The raid described by al-ʿAbbās can be seen, in effect, as an antecedent of the sariyya sent to Yemen carried out by ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as commanded by the Prophet, and both, in turn, as a continuation of events set off by Abraha's incursion. It is within this context that the exchange of military and logistical terms such as sariyya and khalīfa would have taken place. Continued long-distance military feuds between client-tribes would have continued long after the dissolution of the South Arabian monarchy, but because of their lesser political significance to any chroniclers, they would have received less attention. After the Second Persian War between the Byzantines and Sasanians (540–545), the Ghassānids and Lakhmids, their Arab clients, continued fighting for years afterwards, but in their case Procopius (d. 565 ce) took note of the struggle.Footnote 143 Absent the attention of a Procopius, some local or sub-imperial conflicts—independent of but engendered, maintained, or exploited by imperial powers—will have left their traces in history only in the form of poems and etymologies.

A second example of poetry seems to indicate that Arabians of the Hijaz were actually aware of South Arabian royal titulature, and that it potentially offered a model for their own ideological projects. Beginning in the year ca. 445 ce, the kings of Ḥimyar began to add the title, ‘kings … of the Bedouin of the highlands and the coast’ (mlk … ʾʿrb Ṭwd w-Thmt) to their titulature. This expression first appears in the inscription Ry 509, located at Maʾsal al-Jumḥ,Footnote 144 and continued in use until 558 ce, about two generations preceding the advent of Islam.Footnote 145 Robin argues that Ṭwd refers more or less to what is known as Najd in Arabic (both words meaning ‘upland’), and that it was inhabited by the tribal confederation Maʿadd. Ḥimyar ruled it via the client Ḥujrid dynasty of Kinda.Footnote 146 There is a fair degree of evidence for such an arrangement from Byzantine chronicles dealing with Roman diplomacy in Arabia, and some inscriptional evidence. There is less evidence for Thmt, but Robin equates it with the Hijaz, particularly its northern oases, inhabited by a confederation known as Muḍar and ruled over by the pro-Byzantine Banū Thaʿlaba.Footnote 147 He does also suppose that Quraysh would have fallen under Muḍar's sway.Footnote 148

There has hitherto been essentially no direct evidence—as opposed to the indirect testimonial of the impact of Abraha's elephant in their collective memory—that Quraysh was directly affected in other ways by South Arabian incursions. Robin broaches the possibility, however, that the pairing of ʾʿrb Ṭwd w-Thmt is paralleled by the pairing of Najd and Tihāma in Arabic. The opposition of Najd and Tihāma is actually relatively widespread in Arabic, and forms a merism, a common rhetorical device, especially in Semitic languages, by which entirety of a thing is expressed via two contrasting opposites (as in the ‘heavens and the earth’ to refer to all of creation). Kister had already noted a tradition according to which the Persian emperor Kavadh I (488–531) attempted to impose Mazdakite teachings on all Arabs, ahl al-Najd wa-Tihāma (the people of [both] Najd and Tihāma).Footnote 149 As Kister recognised at the time, this tradition is probably spurious, and the meaning “the Arabs of the highlands and the lowlands”, i.e. “all Arabs”, may have no political valence. Such is the case in the vast majority of similar usages.Footnote 150

A poem preserved in the Ashʿār al-Hudhaliyyīn in praise of the Prophet by one Usayd ibn Abī Iyās of Kināna gives one such example of the Najd/Tihāma pairing used in a political sense. Al-Sukkarī tells us, transmitting from al-Aṣmaʿī, that the Prophet had declared Usayd's blood licit, and that Usayd came to the Prophet while the latter was at al-Ṭāʾif to apologise.Footnote 151 From the poem, it appears that Usayd had composed invective against the Muslims. Of interest here is the first line:

This poem deals with more than a rhetorical merism. If the poem were an inauthentic later fabrication, one would expect a more common expression of the totality subjected to Islam, such as that of al-ʿAjam wa-l-ʿArab (Arabs and non-Arabs/Persians), a merism of more interest to post-conquest Muslims. Usayd opts, however, for a geography which does not even encompass the entire Arabian Peninsula, but which very closely resembles the Sabaic inscriptional formula describing Arabia Deserta, Ṭwd and Thmt, the ‘highlands’ and the ‘lowlands’. We have, then, another merism, but one with a political valence; the speaker is clearly paying allegiance to Muḥammad, as his addressee, and makes use of an imagined historical geography which obtained among Muslims only for a very short time, describing the largest relevant political sphere as the ‘highlands and the lowlands’ of Arabia Deserta last dominated, a generation or two before Muḥammad, by Abraha and Ḥimyar. Muḥammad is being addressed, in effect, as a successor to the defunct monarch of South Arabia.Footnote 153 Given that Muḥammad sent expeditions to conquer/convert Yemen in his lifetime and given that his system of delegation owed something to South Arabian influence, Usayd is making an apt assumption.

6. Conclusions

If this essay may seem to have wandered fairly far afield from isrāʾ, this is in the nature of the subject, which if it does not fly express by night across the broad swath from Mecca to Jerusalem, equally well requires us to cast our gaze south towards Yemen, traipsing over the mountains of the Hijaz alongside tribal poets. Through such a survey, the range of alternatives to isrāʾ as ‘night journey’ has been established, and indeed, there is no good reason except for fidelity to the Sīra to continue to suppose that isrāʾ means a ‘night journey’. The classical lexicographical and exegetical tradition continued, throughout the pre-modern period, to preserve alternative meanings. It was also aware that the use of asrā with laylan was redundant. The usage of asrā in the Qur'an is unique in early Arabic, and indicative of a context of authority, command, and hierarchy. It is for these reasons that an etymology relating asrā to sariyya has been proposed here. This has necessitated a larger excursus on the term sariyya, which had hitherto not yet been adequately examined, and on cultural interaction between the pre-Islamic Hijaz and Yemen more broadly. On both of these fronts further research would certainly bring relevant new material to light.

It is worth speculating briefly what an ‘indigenous’ Hijazi isrāʾ may have meant to the early community of Muslims, and—what need not at all have been the same thing—what it meant to contemporary audiences of Arabian converts, most of whom can be assumed to have been essentially coerced.Footnote 154 My reading alters the nuance, and not the denotation of Q. 17:1. Rather than, “Glory be to Him, who carried His servant by night from the holy mosque to the further mosque”,Footnote 155 I would prefer something like, “Glory be to Him, who sent his servant forth by night on a [royal] mission, from the holy mosque to the further mosque”. Such a translation at first glance solves none of the problems that we associate with the Sīra narrative or related scholarly discussions; it does not clarify whether the journey was corporeal or took place in a dream state and it does not conclusively identify either the Prophet or Jerusalem as the referents of obscure nouns (ʿabdahu) and periphrastic phrases (alladhī bāraknā ḥawlahu).

Beyond this, however, an etymology of asrā rooted in sariyya suggests a shift in the reading of Q. 17. Several alternatives to the traditional biographical account, which relies on Sīra and other accounts of revelation (asbāb al-nuzūl), have been suggested by scholars, but one of the most compelling is that of Angelika Neuwirth. In seeking the cause of the traditional accounts’ concern with prayer (most Sīra accounts of the isrāʾ feature Muḥammad leading previous prophets in prayer, while the miʿrāj accounts, later merged with it, feature negotiations between God and the Prophet over the number of canonical prayers in Islam), she notes that Q. 17 is punctuated (Q. 17:78–80, 110–111) with fairly detailed instructions regarding prayer; she thus argues that the early community would have understand ayātinā of Q. 17:1 as revelations concerning prayer rituals and, specifically, a new understanding of sacral states.Footnote 156 According to Neuwirth, this early understanding served as the basis for the mythologising narratives that later emerged.

The sense of a ‘mission’ to Jerusalem, however, implies a more political sense of the topographia sacra Neuwirth mentions, and in this regard Q. 17 ought to be read, not only against Q. 53 (Sūrat al-Najm), as is traditionally the case and as Neuwirth does, but also against Q. 30 (Sūrat al-Rūm), which opens with its prediction of the favourable outcome for the Romans of their war with the Sasanian Persians. Both suras are widely viewed as Meccan,Footnote 157 and as such we would not expect the early community to show much concern with jihād. The root of isrāʾ in a military term does not change this, but there is, nonetheless, a military aspect to the early community's sense of belonging to a sort of ‘greater Hijaz’, encompassing Syria and Yemen.Footnote 158 The Muslims in Mecca would have understood the revelation of both Q. 17 and Q. 30 first and foremost in terms of their embattled situation in the city. As Neuwirth notes, the early Muslims sense of kinship to the Israelites led by Moses serves as an archetype for their own possible expulsion from Mecca.Footnote 159

Yet the scriptural geography—the Christian, Jewish, and in sum, monotheistic world—that the early Muslims inhabited is not that of those other communities. Constantinople or the Mesopotamian centres of Jewish learning held no such significance for them as they would have for Late Antique Christians and Jews. Instead, the Muslims inhabited a monotheistic Hijaz; they encountered regionally inflected versions of Judaism and Christianity. While this initial environment is difficult to reconstruct, it would go on to have significant political consequences. Both early revelation and military activity are directed to the north and south, not to the east or (via the Red Sea) west.Footnote 160 The prophecy of Q. 30, and the spiritual isrāʾ of Muḥammad, anticipate the sariyya of Tabūk. The Qur'an is interested in Sabaʾ, and, as we have seen, ʿAlī was sent on an expedition to Yemen. Yet Muḥammad, as Landau-Tesseron observes, never invaded Yamāma in Najd, although it was a locus of significant military and political activity in the sixth century.Footnote 161

Q. 17 is no less concerned with prophecy than Q. 30. The Torah foretells the destruction of the Second Temple: “We decreed for the children of Israel in the Scripture (al-kitāb): “you shall wreak corruption in the earth twice…”’ (Q. 17:4). The Jewish scripture is then contrasted with the Muslims’ revelation, hādhā al-Qurʾān (Q. 17:9), which foretold ‘great reward’ (ajran ʿaẓīman) to the believers. Again, this certainly does not amount to jihād, but universalist spiritual claims in Late Antiquity would necessarily have entailed territorial claims. For the Qur'an, it was the prerogative of God to bequeath both land and scripture.Footnote 162

The early Muslims would not only have identified with the Banū Isrāʾīl as exiles, but also experienced a sense that they had surpassed them spiritually, just as they had the Meccans; the sins of pride in plentiful sons and wealth, and the resulting hubris and polytheistic disregard for God's sovereignty, are shared by both the Jews and Quraysh according to Q. 17, as Neuwirth points out.Footnote 163 While on a more immediate polemical level, the Muslims are promised to inherit the Meccan polytheists, the community may have been catching a glimpse of the possibility that they would also be heirs to the entire topographica sacra of the Hijaz. The same language of the righteous ‘inheriting the earth’ is used of corrupt pre-Islamic communities (bywords for the transitory nature of the world's glories), for the Jews in the Holy Land, and for the Muslims’ territories in the Hijaz, principally Yathrib.Footnote 164 The isrāʾ as a spiritual ‘mission’ to Jerusalem anticipates this reality, which Muḥammad and the first generation of Muslims’ military-proselytising sarāyā would later strive, eventually successfully, to fulfil.

The militaristic connotation of isrāʾ also has repercussions for how the understanding of the mythologising night journey narratives came about.Footnote 165 The earliest Muslims consisted of a core of more or less devout believers, and a much larger body of Arabian converts (nomadic tribes, Quraysh in Mecca and Thaqīf in al-Ṭāʾif) who submitted to Islam for more pragmatic reasons. These two groups would have viewed the personality of the Prophet differently and it is the latter who would have contributed to the origins of the mythologising ‘night journey’ narratives. Based on the evidence discussed above, some features of the early days of the isrāʾ narrative can here be suggested.

Usayd ibn Abī Iyās's dim awareness of Sabaic royal titulature allows us to conjecture that early converts imagined God the king with some of the lineaments of a South Arabian monarch. Deputising long-distance military expeditions was the prerogative of such a figure. As befitted such a monarch's status, these expeditions would have been mounted and initiated with suitable delegation ceremonies such as we see in the earliest sarāyā described in the Sīra, which also notes that the fighters were mounted (rākib).

Early converts would have imagined Muḥammad being similarly deputised by God. In the case of Muḥammad's isrāʾ, the mount becomes mythologised as Burāq, a figure that several scholars have noted is evidently an indigenous Arabian element in the narrative, rather than, say, a later accretion influenced by Jewish apocalypticism. Neuwirth notes that the interpretation of isrāʾ as a “movement on horseback” is “alien to the horizon of qur'anic imagery”, while Reuven Firestone supposes that Burāq's presence reflects the strong equestrian culture of pre-Islamic Arabia.Footnote 166 Al-Azraqī also notes that Abraham used Burāq to travel between Syria and Mecca,Footnote 167 and if this is an ancient report, Muḥammad's journey on Burāq may reflect his status as a new Abraham from the originally non-Muslim but henotheistic, Arabian perspective of early converts. They would, after all, have associated Abraham and the Meccan sanctuary before the emergence of Islam; the Qur'an presupposes the connection.