In this article, we discuss how the Dutch archaeological sector presents the past in terms of gender representations and stereotypes and what can be observed in public perceptions of people in the past. The study of gender representations is encouraged by national and international policy frameworks (e.g., UNESCO, the Council of Europe, etc.) that ask the cultural heritage sector to achieve greater accessibility and wider public participation. This implicitly means that the aim of the sector's presentation efforts and all other participation activities is to reach out and include as many people as possible, allowing everyone to enjoy heritage and to connect to and identify with the past. However, the sector faces serious challenges to actually increase community engagement and to maximize inclusiveness. There is, in fact, an abundance of survey data showing that we do not reach large parts of the public yet; we miss out on large groups, such as young adults, migrants, and disabled people.

In the Netherlands, we can observe a significant and persisting discrepancy between male and female participation in archaeology. We note that in this article, we use a simplified two-gender classification, acknowledging that genderqueers may not identify with either group and that representation of gender-fluid and genderqueer experiences could be studied further as well. The typical audience for archaeology is mostly older (45-plus) males with a high degree of education and a high standard of living. This was the case in the 1990s and has hardly changed since (see, for instance, van den Dries and Boom Reference van den Dries, Boom, Kamermans and Bakels2017). Data from a large public survey that was conducted at the start of 2015 by the NEARCH research network (http://www.nearch.eu/) in nine European countries (see also Kajda et al. Reference Kajda, Marx, Wright, Richards, Marciniak, Rossenbach, Pawleta, van den Dries, Boom, Guermandi, Criado-Boado, Barreiro, Synnestvedt, Kotsakis, Kasvikis, Theodoroudi, Lüth, Issa and Frase2018) shows that this gender gap is rather consistent across Europe.Footnote 1 For example, nearly three-quarters of the male respondents said they had once visited an archaeological site, and this was the case with only two-thirds of the female respondents. The survey shows many additional examples along these lines.

The fact that across the board in Europe there is still a statistically significant lower participation in archaeology by women is puzzling because the NEARCH public survey also shows that their attitude toward archaeology is not less positive. In fact, a slightly larger percentage of women than men indicated that they consider archaeology useful (92% vs. 89%) and of great value (91% vs. 90%). Moreover, women are not significantly less interested in the subject of archaeology either; 64% would be interested in taking part in an archaeological excavation versus 57% of the men. For the Netherlands, this was 45% (versus 42% of the male respondents). For us this high interest among women was surprising, as it is not always the case. For instance, in a locally conducted public survey in a town called Oss (province of Noord Brabant) we found more males than females interested in joining the excavation that was taking place in their neighborhood (van den Dries et al. Reference van den Dries, Boom, van der Linde, Bakels and Kamermans2015).

The NEARCH survey also demonstrated that a majority (55%) of all the female respondents in Europe seem to feel a “personal attachment” to the topic. This number almost equaled that of the male respondents (57%). In the Netherlands, these statistics differed, with 41% measured for females and 48% for males, but we had more females (16%) than males (12%) expressing an interest in studying archaeology. This higher interest among women represents the situation at the Faculty of Archaeology of Leiden University, the largest academic institute for archaeology in the Netherlands, where 54% of all 3,598 newly inscribed students between 2006 and 2013, were registered as a female.Footnote 2

Given these statistics, the question remains why women seem to be less inclined to make an effort to engage with archaeology by visiting sites or exhibitions or by reading books or watching documentaries. There are no obvious or straightforward explanations for the discrepancies shown in the NEARCH survey or in other visitor studies, and we can only surmise about the reasons that females participate less in archaeology. We do know that if archaeology is presented at places that people visit for other reasons, like to buy groceries or attend a horticultural show, large numbers of females do engage with archaeological exhibitions (Boom et al. Reference Boom, van den Dries, Gramsch, van Rhijn, Jameson and Musteata2018; van den Dries et al. Reference van den Dries, van Rhijn, Willems, Hoogduin and Lam2017). It has been observed at several such locations that female viewers outnumbered males. This implies that to further develop inclusivity by breaking down barriers for particular groups, we need to better understand what the push and pull factors are, for whom, and when.

The NEARCH survey does offer some clues with which to better understand the interest of women in participating in archaeology. For instance, 64% of the Dutch female respondents think archaeological exhibitions in Dutch museums are informative for every group, while the European average for this question was 70%. This suggests that some may not find what they are looking for in the stories and presentations offered. Moreover, female respondents differed from male respondents; if they were going to visit an archaeological site or exhibition, Dutch women would prioritize one devoted to prehistory, and men would choose the Middle Ages. In fact, females showed a significantly lower interest in the Middle Ages (16%) than male respondents (23%). Such statistics made the authors wonder whether they illustrate Holtorf's (Reference Holtorf, Smith, Messenger and Soderland2010:45) suggestion that “the story people are perhaps most interested in when they choose to visit heritage sites is in part a story about themselves.” Could the observed lower interest in participating among women perhaps reflect diverging preferences, and thus relate to the mainstream archaeological narratives and the way the heritage sector depicts the past? In other words, do we actually offer men and women equal opportunities to connect and identify with the past? Is the kind of information we display in books and exhibitions actually what all of our target groups are interested in? It is within this context that the authors started to collect data on how the past is presented in Dutch archaeology and on the public perception of gender stereotypes in the past. The first results are discussed here.

SOURCES AND METHODOLOGY

The aim of this study was not to conduct an exhaustive study of all sources and presentations on Dutch archaeology that are available, as this would not be feasible. The aim was to sample the main sources through which the Dutch public may learn about the archaeological past in order to get an idea of what a majority may see. The main source through which children are introduced to the past is through schoolbooks and museum visits, so we included a collection of those. Adults obviously learned the same way during childhood, but in the NEARCH survey, they indicated that today their main sources of information are television/radio programs and local newspaper articles (NEARCH; van den Dries and Boom Reference van den Dries, Boom, Kamermans and Bakels2017). As it would be very difficult to identify a sample of these that may have been watched or read by a large group, we identified major exhibitions and publications for this group too since visits to museums and reading books are among the top-10 sources for information about archaeology.

Our sample of books included three of the main popular Dutch books on archaeology published in the past 30 years. The first, Verleden Land (Bloemers et al. Reference Bloemers, Kooijmans and Sarfatij1981), dates from the 1980s. The first of its kind, it offered the public the first synopsis of the main discoveries and state of affairs of Dutch archaeology. It was distributed in a print run of 96,000 copies and won the “book of the month” award in September 1981. It was also accompanied in 1982 by a traveling exhibition that was on display in several large museums across the country. The second popular book we selected, Oermensen in Nederland (Roebroeks Reference Roebroeks1990), dates from the 1990s and focused on the earliest ancestors from the Paleolithic. This one was selected for our study because in 1991 it won the KIJK/Wetenschapsweek prijs, an award for disseminating academic knowledge to the public. The most recent selection, Onder onze voeten (Verhart and van Ginkel Reference Verhart and van Ginkel2009), was published in 2009. It is the successor of Verleden Land as it offers an updated state of affairs on Dutch archaeology.

The analysis of these three books focused on illustrations. It consisted of a quantification of the feminine and masculine objects shown in pictures and a gender classification of mannequins and of characters in reconstruction drawings (including models, photos of reenactment activities, representatives of indigenous tribes, etc.). We also made a gender classification of archaeologists and other experts (or people at work) visible in drawings and photos, and a gender classification of visitors—again, in illustrations only. For the objects, we verified if they were either held by a male or female or were identified as masculine or feminine in the captions or associated text referring to the illustration. We distinguished two gender groups, males and females, and an “unspecified” category. The classification of individuals in the illustrations was based on a combination of clothing and physical characteristics (like posture, facial features, and hairstyle). Gender in this context is therefore defined as a person's representation as male or female as interpreted by the researchers. Whenever there was any doubt with regard to a person's gender, this person was not counted or counted as a separate category (unspecified, or unknown). Children were not counted as it was considered unreliable to distinguish boys from girls on the basis of physical differences and clothing only.

The category of exhibitions included three of the main permanent archaeological exhibitions in the Netherlands. The National Museum of Antiquities (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden [RMO]) in Leiden was selected as it is the oldest and main archaeological exhibition in the Netherlands. It receives on average between 150,000 and 200,000 visitors annually, of which more than 10% are schoolchildren.Footnote 3 Here, the exhibition of the Dutch prehistory was analyzed in July 2016. The Noordbrabants Museum in Den Bosch was selected as it is one of the few larger provincial museums still displaying a substantial collection of archaeological artifacts.Footnote 4 It received 177,000 visitors in 2015.Footnote 5 Here, the permanent exhibition on the history and culture of Noord Brabant and the southern Netherlands was analyzed in September 2015. The third exhibition is located in the northern part of the country. The archaeological center of the province of North Holland, the Huis van Hilde (Hilde's House) in Castricum, was selected as it is the newest Dutch museum focused on archaeology. It opened its doors at the start of 2015 and is named after a female historic character, Hilde. In its first year, it received 46,000 visitors, of which a quarter were children.Footnote 6 Here, the exhibition on the habitation history of the province was analyzed in July 2016. These museums were visited by one of the authors, and they were analyzed in the same way as the books, with a focus on the objects on display and on people in any kind of reconstruction and in all other illustrations.

Also at each of these three museums, a popular book was purchased in the museum shop. These are books that were linked to the exhibitions that we analyzed and were also top sellers at the museum. The latter is an indication that these publications were purchased by the general public and as such can be considered a source through which quite a number of people learn about the past. At the RMO, Varen op de Romeinse Rijn (Hazenberg and van der Heijden Reference Hazenberg and van der Heijden2016) was selected; at the Noordbrabants Museum, De Romeinse Villa van Hoogeloon (Hiddink Reference Hiddink2015) was selected; and at the Huis van Hilde, Het land van Hilde (Dekkers et al. Reference Dekkers, Dorren and van Eerden2006) was selected. These exhibition publications were analyzed in the same way as the three main popular books.

In the category of schoolbooks, 10 history books were included: nine for primary education and one for secondary education.Footnote 7 These were all books that were in use at schools in 2015–2016. The secondary education book was analyzed in the same way as the popular books and the exhibitions. The analysis of the schoolbooks for primary education, however, was conducted as elaborate bachelor's thesis research (Kerkhof Reference Kerkhof2016). It did not include objects and experts, only illustrations of historic characters and scenes (reconstructions). These were analyzed in more detail than the other depictions we studied, a bit similar to the study of reconstructions of prehistoric life in National Geographic magazine by Julie Solometo and Joshua Moss (Reference Solometo and Moss2013) and of Paleolithic life in cavemen dioramas by Diane Gifford-Gonzalez (Reference Gifford-Gonzalez1993). This yielded data on how men and women are being portrayed: active or passive, at the front or the back of the picture, in what kind of scenery (public or private), and associated with what kind of activity.

Perceptions of the Public

As stated earlier, the authors also aimed to evaluate whether there would be a difference or similarity between the representation of the past by professionals and the image that members of the public have in mind about the past. Therefore, the authors also included material from the public in their analyses. This consisted of two sources. First, the NEARCH research project, in which the first author was a partner, has a sample of over 300 drawings, paintings, photos, and videos from members of the public. These were submitted in 2015 by people from 15 European countries as part of an archaeological art competition, which was then turned into a traveling exhibition (see http://www.archaeologyandme.eu/en/ or http://www.nearch.eu/). Members of the public were asked to creatively express their answer to the question, What is archaeology for you? The drawings and paintings that were part of this collection (33 made by children/young adults and 97 made by adults) were analyzed to get an idea of how the public depicts the past and to see what their gender representation looks like when they draw or paint their impressions or inspirations from the archaeological past.

Second, the authors designed a study in order to gather data on gender representations and role models directly from children. During the summer of 2017, we revisited the RMO in Leiden and the Huis van Hilde (Hilde's House) in Castricum, and we asked children ages 8–10 to express their ideas about men and women and gender roles in the past. These were children who were visiting the museum with their parents or other adult chaperones. After we got permission from the accompanying adults, we would ask the children who had just visited the exhibition to fill out a short questionnaire and to make a drawing about the past. In total, the study included 100 children, 50 at each location, all 8–10 years old. At both locations, the number of girls and boys were split evenly (25; Kerkhof Reference Kerkhof2017).

RESULTS

Here, a selection of the results is briefly discussed for each of the sources we analyzed; some were drawn from reports by Kerkhof (Reference Kerkhof2016, Reference Kerkhof2017). All data is on file at the Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University.

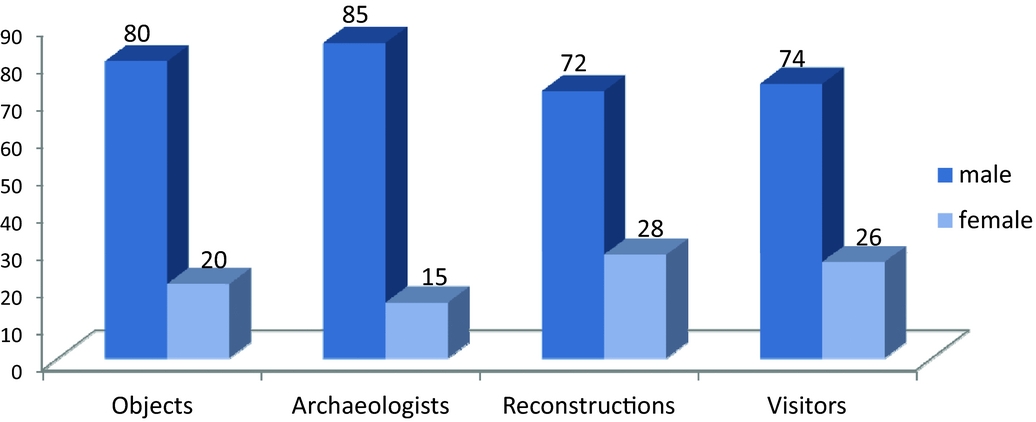

For the three popular Dutch archaeological books, 430 objects (128, 7, and 295, respectively) could be characterized as masculine or feminine. In general, weaponry was associated with males, household items and jewelry with females. It turned out that in two of these books, there was a considerable overrepresentation of objects associated with males (Figure 1). The book from the 1990s shows a different picture; due to the fact that its topic is the earliest ancestors from the Dutch Paleolithic, who date back to 250,000 BP, it shows only a few objects (mostly stone tools). As these objects could not be linked to any gender group, this book was determined to be gender neutral in regard to the objects it displays.

FIGURE 1. Gender distribution (in percentages) in the illustrations in three major popular publications on Dutch archaeology. It concerns 430 objects, 439 archaeologists/experts, 133 individuals in reconstructions, and 107 members of the public.

In total, 439 (153, 60, and 226, respectively in the three books) archaeologists or other experts could be classified as male or female, and at least three-quarters of the total number of individuals on display turned out to be male. We note, however, that Verleden Land (Bloemers et al. Reference Bloemers, Kooijmans and Sarfatij1981) aimed to present the state of affairs in Dutch archaeology on the basis of all excavations conducted until that time, so it included a number of historic photographs showing archaeologists from a period in which women still made up a small portion of the profession. The most recent book contains some historic photos as well, but as it aimed to present the developments since the 1981 book was published, including new research developments and new discoveries, it could have compensated for the historic gender bias with pictures from more recent periods in which women are well represented in the profession.

In the reconstruction drawings, a total of 133 individuals (73, 13, and 47, respectively) could be identified as either male or female. In each of these books, at least 70% of them were male. Oermensen in Nederland (Roebroeks Reference Roebroeks1990) does not contain many reconstruction drawings as such, but it shows photographs of people from contemporary traditional tribes conducting activities analogous to those of the past and using stone age–like artifacts. It is striking to see that while the presentation of the artifacts is gender neutral, as we just discussed, the interpretation and the narrative mainly portrays males using such tools (77% vs. 23% female).

The public is not shown in large numbers in these books; only 107 individuals (20, 1, and 86, respectively) could be classified as male or female in the books we purchased. Nevertheless, a majority of these visitors are male (74%). The book from 1990 contains only a single individual, a woman. We were surprised by this high number of male visitors portrayed; we know from the NEARCH survey and other studies that men outnumber women as visitors, but not in a ratio of 3:1.

Exhibitions and Related Popular Books

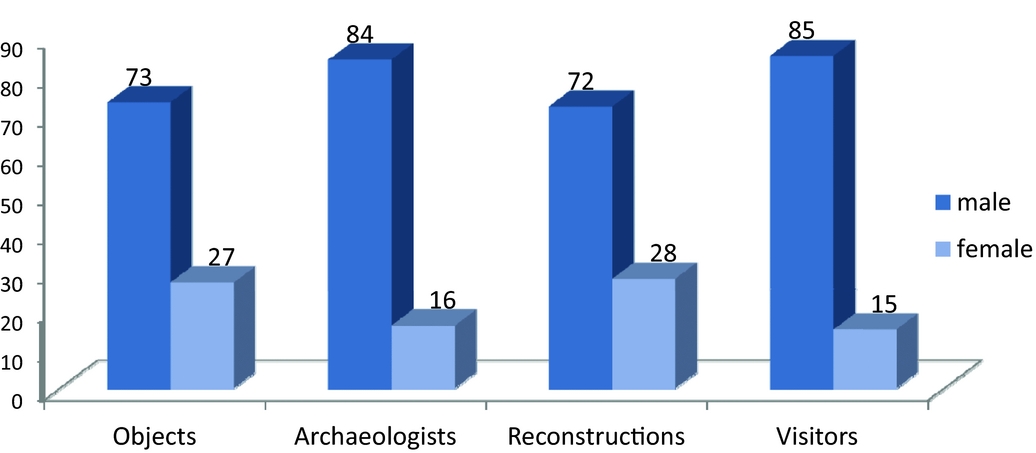

The analysis of the three permanent exhibitions at the selected museums yielded similar patterns (Figure 2). A total of 79 objects were counted in the Noordbrabants Museum, 145 in the RMO, and 38 in the Huis van Hilde. In the first two, there was a dominance (both 76%) of objects associated with males, like weaponry, or with masculine activities, like fighting. The Huis van Hilde showed a slightly different picture, with much more gender balance in its collection of objects on display (58% masculine and 42% feminine). In the reconstructions (drawings or mannequins) in the three exhibitions, 288 individuals (165, 78, and 45, respectively) could be identified as male or female. In the first two exhibitions, a majority of around three-quarters were men; in the Huis van Hilde, just over half (53%) were men. Of the latter's life-size mannequins, 60% are male (9 out of 15). The representation of archaeologists was extremely unbalanced in all three exhibitions, with a total of over 80% being male.

FIGURE 2. Gender distribution (in percentages) in the permanent archaeological exhibitions in three of the main Dutch museums. The material analyzed concerns 262 artifacts on display, 280 archaeologists in illustrations, 288 individuals in reconstructions, and 33 visitors.

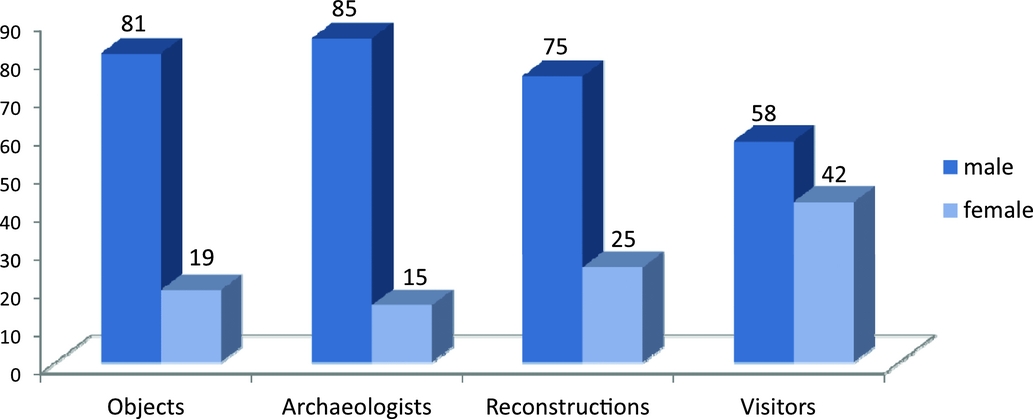

From the three exhibit publications, the same patterns occurred once more (Figure 3). While Het Land van Hilde (Dekkers et al. Reference Dekkers, Dorren and van Eerden2006) displays an almost balanced number of male (52%) and female objects (48%), the other two do not, leading to a total of 81% of all 75 objects being associated with a male or a masculine activity. Most of the individuals (N = 217) represented in the reconstructions in these booklets are males (75%) as well. It is most striking that the book telling the story of a Roman house (villa)—thus, a domestic scene in which one certainly would expect female characters to be represented—actually shows the lowest number of females (6%). In all three books, the archaeologists are again almost exclusively male (85%), with one of them (Varen op de Romeinse Rijn [Hazenberg and van der Heijden Reference Hazenberg and van der Heijden2016]) showing no female experts at all.

FIGURE 3. Gender distribution (in percentages) in the illustrations in three small popular publications that are linked to the three permanent museum exhibitions. It concerns 75 objects, 106 archaeologists, 217 individuals in reconstructions, and 60 visitors.

SCHOOLBOOKS

It did not come as a surprise that in the schoolbooks on history women were again hard to find. In the book that is in use at secondary schools, 86% of the 455 counted objects were associated with males. The historic figures and other individuals (206 in total) presented consisted predominantly (84%) of men. In the nine books used at primary schools, a total of 3,806 individuals were counted in 616 illustrations, of which 2,862 (75%) were identified as males and 677 (18%) as females; the remaining 7% could not be classified (Kerkhof Reference Kerkhof2016).

In the portrayal of these individuals, an apparent gender stereotyping could be observed. It was found that 1,113 of the males (adults and children) were depicted in the foreground, against 375 females; this is 39% of the men versus 55% of the women. However, in terms of passive and active postures, a minority of 34% of the women were active, in contrast to 87% of the males. With regard to the type of scenery or the location in which individuals were portrayed, a huge difference could be observed as well, with 40% of the females being placed in the direct vicinity of the house or the dwelling area, against 9% of the males. A majority of the women (54%) were positioned in a public setting, such as a market, but this was also the case with 86% of the males.

Furthermore, there is a strong tendency of depicting men and women while performing stereotypical activities. The things men do most are heroic activities, like fighting, safeguarding or saving others, and hunting/fishing. They also are mostly traders, farmers, and builders, and they have roles in governing. Traveling and performing rituals are also among the top-10 activities shown most for males. Females are mostly active in taking care of children and of older people; household activities like cooking, cleaning, butchering, and gathering food; and in artisan production, like textiles, leather, and ceramics. Also in the top-10 activities are conducting rituals and buying or selling things at the market. Even elderly people are depicted stereotypically: they are often shown as passive, being poor or weak (paupers), or as ill and being taken care of or deceased. When they are active, favorite activities for elderly people are teaching and leading rituals.

Altogether, a rather disturbing pattern emerges from these schoolbooks; namely, that the whole of history is made by males. They are the heroes. Women played only a minor role. They are not portrayed in important roles and do not appear in equal numbers in educational material. This androcentric interpretation of the past is, based on the aforementioned analyses, what our present-day society is teaching our children.

Artwork

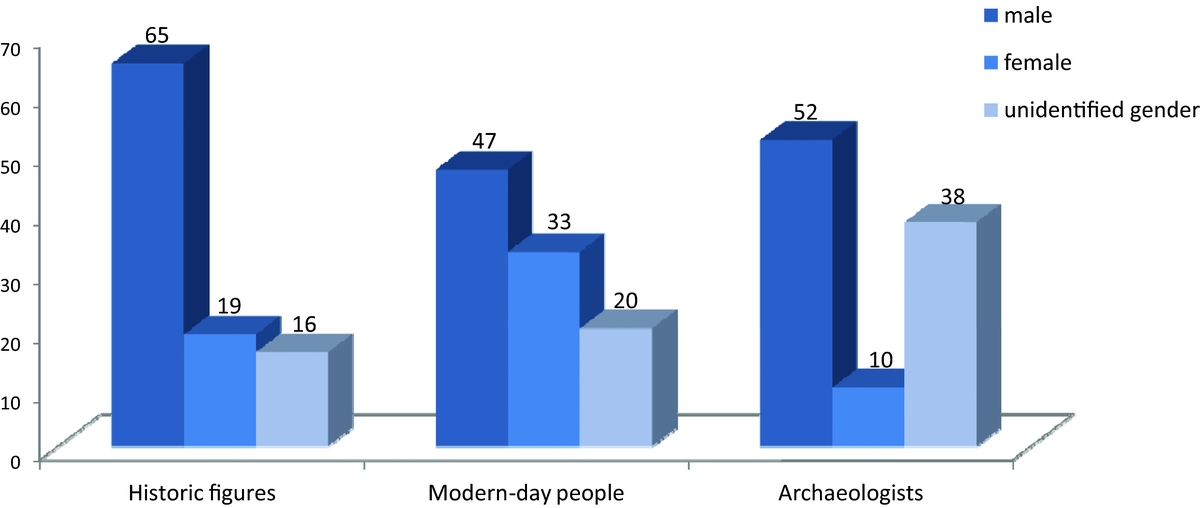

With regard to the artistic expressions produced by children and young adults for the NEARCH competition, we noticed, first, that the children had a clear preference for drawing objects rather than persons, animals, buildings, or landscapes, et cetera; 22 out of the total of 33 drawings showed one or more objects. The second most popular subject was people. They were present in 20 works of art, and they showed a total of 29 individuals: 9 were historic characters, 8 were archaeologists, 11 were modern-day individuals, and 1 was a fantasy character. In terms of gender representation (Figure 4), there was an overrepresentation of males, both in historic figures (65%) and archaeologists (52%).

FIGURE 4. Gender distribution (in percentages) in the artwork (33) children contributed to the NEARCH exhibition Archaeology&ME. The artwork showed 43 historic figures, 15 modern-day individuals, and 21 archaeologists.

Children showed in their artwork a more gender-balanced representation of contemporary individuals than of historic figures. Their perception of gender balance in the past seems to deviate from that of the present. This raises the question of whether what they learned about the past differs from what they observe in daily life.

Also interesting is that when the artwork depicted prehistoric activities (16 times), fighting dominated. Fighting was drawn five times. Moreover, in every instance, it was exclusively performed by male characters. Although such small numbers do not allow rigid conclusions, they do suggest that the children we interviewed had gender stereotypes in mind when they imagined the past.

When we compared gender representation in the artwork of the children with that of the adults, we noticed adults drew more male than female characters as well. In particular, when archaeologists were portrayed, 73% were male versus 7% female (with 20% unidentified). It suggests that even though nowadays in Europe more than half of the workforce (50.3%) consists of female archaeologists,Footnote 8 members of the public still consider archaeology a typically male occupation. Perhaps this is the Indiana Jones effect, a strong traditional role model that is hard to get rid of, but it is also not helpful that the sector shows predominantly male archaeologists in books and exhibitions too.

Children's Survey on Gender Roles

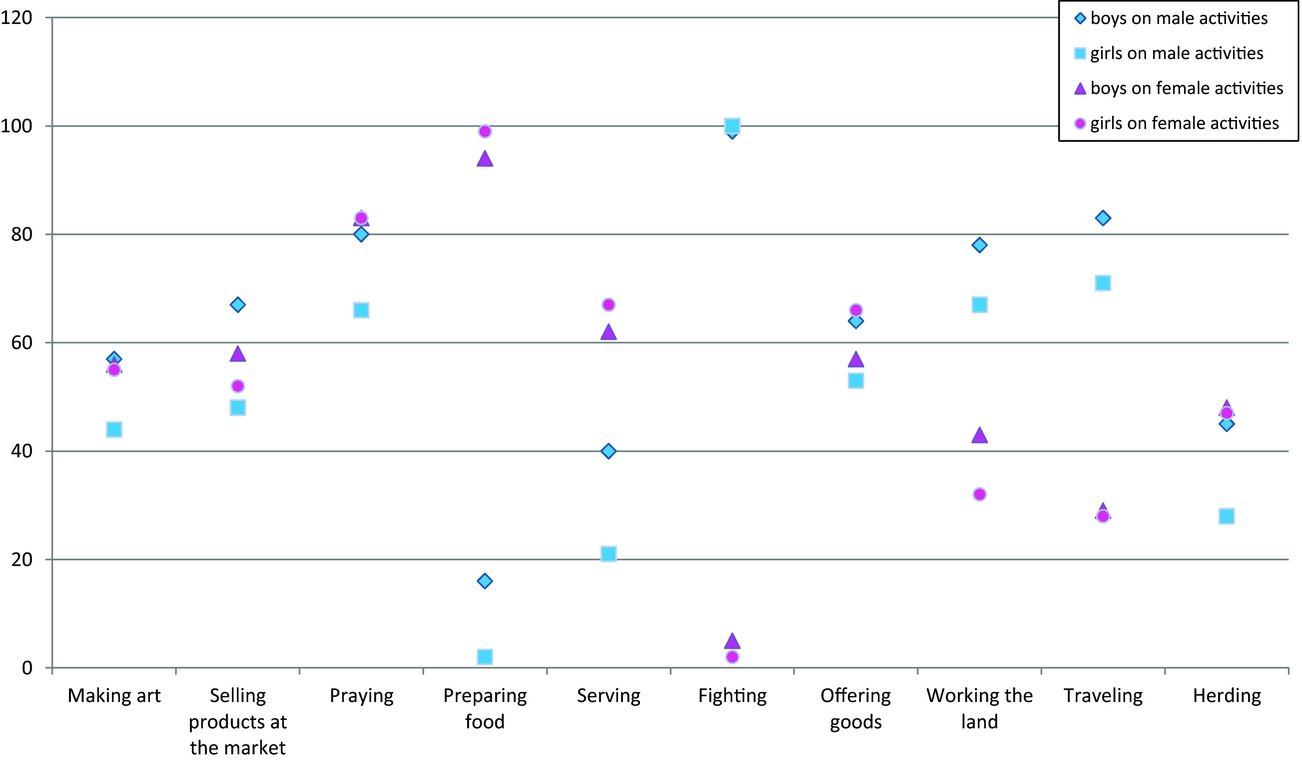

Figure 5 shows to which gender group the children connected the historic activities we mentioned. We presented the same activities for both the Roman period and the Middle Ages. The results demonstrate that our survey participants had strong gender-stereotyped ideas about the past; nearly all boys and girls associated fighting exclusively with males. Girls in particular connected household activities, like preparing food and serving, mostly with females. Moreover, outdoor activities were far less ascribed to women than to men. Some boys seemed a bit more emancipated, as they selected a larger variety of activities for both males and females. Several boys (16) said, for instance, that men could have been preparing food, while only two girls thought so.

FIGURE 5. Presumed gender roles in the past, indicated by 100 children (50 girls, 50 boys) ages 8–10 in a survey at two Dutch museums.

We were struck by how well these gender associations coincide with the schoolbook portrayals and how many boys and girls agreed on these gender roles, those of females in particular. The fact that they are so unanimous about these role models raises the question of whether they all came up with these stereotypes by themselves or whether they were just reproducing what they had been taught.

When we asked the children whether they believed males outnumbered females in the past or vice versa, 43% of the children assumed for the Roman era an overrepresentation of males, and 36% expected the numbers to have been equal. The prime reason given for such an overrepresentation was that men were needed in combat. Since women did less dangerous work, fewer females were needed (25%). Interestingly, 59% believed in an equal gender representation in the medieval period; only 24% thought there might have been more males. Apparently, these children associate the Roman period more strongly with fighting than the Middle Ages. When we asked whether they would have preferred to be a boy or a girl if they had lived in the past, six girls said they would have liked being a boy versus two boys who would have preferred to be a girl. All others held to their current gender. A large number mentioned fighting and safety as the prime reasons for their choice.

This strong association of the past with fighting recurred throughout this survey. When we asked the children to select one illustration out of six that for them most typically represents the Roman era and the Middle Ages, for both periods a picture showing combat was selected most (by 81 children for the Roman era and 49 for the mediaeval period). Moreover, in the pictures we asked them to draw about the past (thus, the things they associate the past with), we saw a preference for objects (60%)—like in the artwork of the NEARCH project (Table 1)—and over 50% of these 65 objects related to combat. Only 26% of the objects concerned household activities. Interestingly, 55% of the weaponry was drawn by girls, and so were all five items of jewelry. It struck us even more that not one of the 43 historic characters drawn was a female (Figure 6), so all the girls drew a male historic figure. There was clearly a connection with the exhibition the children had just visited, as most children chose to draw an object or person that was on display in the exhibition.

TABLE 1. Subjects of the Drawings Made by 100 Children (50 girls, 50 boys) between the Ages of 8 and 10 during a Survey at Two Dutch Museums.

FIGURE 6. When we asked 100 children “to picture the past,” both girls and boys (ages 8–10) drew male historic figures (17) only, such as the “gladiator” in this example.

Given the influence of the exhibition on the drawings, we were curious to see whether there would be a difference in the answers and depictions between the groups of children at the two locations. At the Huis van Hilde, which is named after a female character, there is much more attention to women than at the RMO. It has, for example, a large number of life-size female mannequins. One is a woman (called Brecht), who lived in the transitional period from the late Middle Ages to the era of the Dutch Revolt beginning in the sixteenth century AD, who holds a large sword. This seems to have affected the perception of the children, as at the RMO—which has no such female role model—none of the children assigned women a role in fighting, while at the Huis van Hilde, seven did. On the other hand, girls at the Huis van Hilde associated women far less with offering goods (25 times) than at the RMO (41), even though at the former, there is also a prominent depiction of a female performing a sacrifice ritual.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The above shows the first and preliminary results of work in progress on a systematic evaluation of gender representation in Dutch archaeology. Although the sources so far analyzed are not a statistically representative sample of the archaeological narratives in books and exhibitions on offer, we have no reason to expect these patterns would change drastically if we enlarged our sample. Our results are strongly patterned, and they correspond with those of prior comprehensive studies on gender representation in illustration and pictorial reconstructions (see, for example, Gifford-Gonzalez Reference Gifford-Gonzalez1993; Henson Reference Henson2017; Moser Reference Moser, Cros and Smith1993; Solometo and Moss Reference Solometo and Moss2013). Although our analyses have not been as detailed as some of these, they do reveal a similar notable imbalance in gender representations and a strong tendency toward gender stereotyping in depictions of prehistoric activities.

From the results, we have to conclude that what the Dutch archaeological community is showing society is not representative of what happened in the past. With some exceptions, such as the presentation in the Huis van Hilde, most portrayals are misleading, as there surely was not a ratio of 70%–80% of males and 30% or less of females in the past. The ratio of male and female archaeologists on display is wrong as well. Yet, these are the dominant patterns presented to the Dutch public, time after time, over a period of several decades. There are some alternative examples, like the preschool children's book De archeoloog (Slegers Reference Slegers2010) about the archaeology profession (Figure 7) made by the Archaeology in Contemporary Europe project in 2010 and in which the main character is a female archaeologist, but these seem to be exceptions. In fact, the Dutch heritage sector is showing a worse gender imbalance in representations than Dutch newspaper photos, which consist of a ratio of 65% males versus 35% females (Melis Reference Melis2014).

FIGURE 7. In 2010, the Archaeology in Contemporary Europe project developed a book about the archaeology profession for preschool children showing a female archaeologist.

We cannot claim with any degree of certainty, on the basis of this study, that these male-dominated stories cause women to identify less with the narratives about the past and therefore to engage less with archaeology than men, as we saw in the NEARCH survey. However, the public, both adults and children, does seem to mimic gender bias and stereotyping in their perceptions of the past, and they tend to express a stronger bias in artistic presentations of the past than of the present. This suggests that this presumed relation deserves to be studied in more depth, in particular because it cannot be ruled out that this gender bias has negative impacts on our audiences, such as on children. In social science, for instance, evidence is found that children who are presented with stereotypical gender behavior in the media tend to internalize these roles and shape their own behavior likewise (e.g., Ward and Aubrey Reference Ward and Aubrey2017). According to these studies, it can be seen that even young children already think boys and men are better than girls and women. They associate brilliance more with boys than girls, even though girls graduate with higher marks. It even seems to keep both girls and boys from experiencing their full intellectual and professional potential, something which is obviously detrimental to these children and to society (Ward and Aubrey Reference Ward and Aubrey2017).

Regardless of whether our presentations have such a serious impact on our visitors or not, this inequality and gender bias can be considered abject. The underlying message we implicitly convey by continuously overemphasizing male objects, male activities, and male musculature in depictions is that men and masculine activities deserve more attention than women and feminine activities. The message that we still value these two gender groups differently is further strengthened by showing males predominantly in strong, heroic, and public activities and females in domestic settings and as the more passive group. As a sector, we have a responsibility to strive for inclusiveness, an ambition not many people will disagree with. But our goals are not demonstrated by our actions. The fact that there is still a very limited consciousness about gender bias among some of the people who are producing archaeological narratives and presentations also means we have to keep monitoring gender bias, even after more than 25 years of gender archaeology.

Fortunately, there is a positive perspective as well. From the comments we have had on discussions about this topic, it is clear that some (male) presenters of archaeological narratives were quite shocked to hear about the patterns we found in our data. They said they were unaware of a gender bias in their presentations, and they were also unaware of any of the previous studies on gender bias (or they never related these to their own practices). This suggests that current representation practices are not driven by immoral motives or by specific marketing objectives, like for instance in the film industry, but are merely the result of unawareness. There should, therefore, be a willingness to change these old-fashioned practices. We could start by realizing and acknowledging that we are always biased when telling stories about the past, as we have “a self-referencing representational tradition” (Gifford-Gonzalez Reference Gifford-Gonzalez1993:24). In each narrative we tell, each exhibition we construct, we should thus apply equality measures by exploiting the rich source of gender studies that help people move away from stereotypical portrayals.Footnote 9

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to colleagues and family members for helping to collect data: Femke Tomas (Faculty of Archaeology) provided data on student numbers from the Dienst Uitvoering Onderwijs registers; Jarien Fokkens and Harry Fokkens joined to do the endless counting in the museum exhibitions. We also thank the children and parents visiting the Huis van Hilde and the National Museum of Antiquities (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden [RMO]) for participating in the survey and for their artistic contributions. We are further grateful to Anouk Veldman and Myrthe Flierman of the Huis van Hilde, and to Rita van Oosterhoud of the RMO for allowing us to do the research among their visitors. We thank them for their support and for helping to organize this aspect of our research project. Finally, we are grateful to the reviewers and editors for their useful comments on our drafts. Muchas gracias a Eldris Con Aguilar for translating the abstract. This publication was produced in the framework of the NEARCH project, with the support of the Culture 2007–2013 program of the European Commission.

Data Availability Statement

All data is on file at the Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University.