This article examines Afro-Asian Jewish repatriation to Morocco and Iraq from Israel in the mid-1970s. For historical context, I begin with a general overview of state-based responses to Jewish out-migrants to illustrate the difficulties faced by potential emigres. Then, I move on to several high-profile cases of Moroccan and Iraqi Jewish repatriates from Israel and the discourses surrounding their migration. I make use of government transcripts and reports; annual statistical reports; as well as the three most popular Israeli newspaper sources—Ma'ariv (Evening), Ha'aretz (The Land), and Davar (Word)Footnote 1—to understand the position of the Israeli state elite. To demonstrate the thinking, motivation, and concerns of out-migrants, I make use of interview transcripts from the Iraqi Jewish Archives. Examining Jewish repatriation to the Arab world as an act of transgressive migration, I argue for further complication and carefulness in the study of migration to and from Israel by focusing specifically on out-migration and what it tells us about the notion of Jewish homeland.

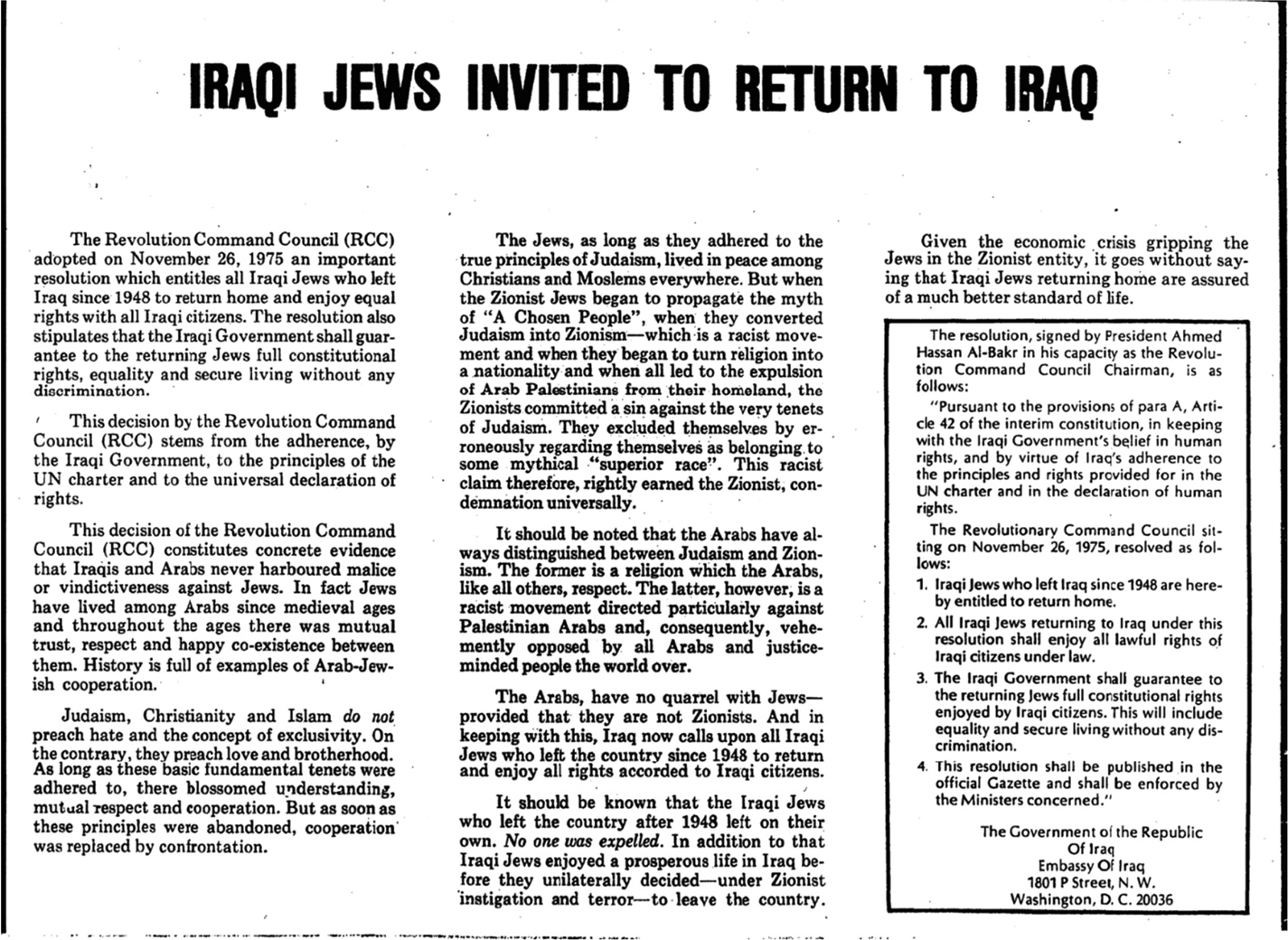

In 1975, King Hassan II of Morocco and President Saddam Hussein of Iraq sent advertisements throughout France, the UK, and the US with one request: for its Jewish Diaspora to return to their “beloved” homeland (Fig. 1).Footnote 2 A year later, the theme of the twenty-eighth anniversary celebration of Israel's founding was “Israel and the Diaspora.” Events following the announcement of this theme would prove it to be a topical choice. As a part of the festivities, Israel released its annual demographic report on Israeli Jewish migration. But, with Moroccan and Iraqi families repatriating and an unprecedented higher rate of migration of Israeli Jews out of Israel than to it, the report was no cause for celebration. Then prime minister Yitzhak Rabin gave a well-known televised interview where he infamously derided yordim—Israeli Jewish citizens who emigrate from Israel—as the “fallout of wimps” (nepolet shel nemoshot). Rabin's equation of Jewish out-migrants to manufacturing waste such as from defective materials in an assembly line or radioactive residue—albeit shocking—was not unique in Israeli history. Throughout the twentieth century, Zionist leaders referred to Jewish migrants to Israel/Palestine as “human material.” Human material (menschenmaterial), that horrific German un-word (unwort) of the twentieth century, has remained within Israeli Hebrew parlance in the form of questions surrounding Jews as desirable migrants/emigres. The phrase echoed those of societal engineer Arthur Ruppin, who successfully pushed for—in his capacity as immigration policy influencer—a racialized restrictive immigration policy (Auslese prinzip) within the Yishuv. This selective immigration policy privileged Western European Jews as desirable, high-quality “human material” while Mizrahi Jewish migrants to Palestine were low-quality material who were to be “sifted” out, useful only for their quantity.Footnote 3 David Ben-Gurion expressed a similar sentiment when he referred to Holocaust survivors and Afro-Asian Jewish immigrants as “raw human material” (homer enoshi galmi); “a mixed multitude (erev rav) and human dust (avak adam).”Footnote 4 Moreover in early 1949, Ha'aretz correspondent Aryeh Gelblum infamously penned a series of articles under the title “Ha'emet ’al Haḥomer Ha'enoshi” (The Truth about Human Material) in which he framed Jewish migration to Israel in explicitly racialized terms and warned of the “dangerous Aliyah from Africa” of Moroccan Jews.Footnote 5 While Rabin was a fairly inarticulate and brash speaker, this disturbing sentiment has held credence as an acceptable term. If Afro-Asian Jews were such poor-quality human material, then why such a backlash against out-migrants? Why such a visceral reaction to the freedom of movement allowed to a Jewish population? What does this tell us about Jewish belonging, particularly for Moroccan and Iraqi Israelis subject to marginalization and derision? How might transgressive migration complicate our notions of Diaspora and homeland?

Figure 1. New York Times paid advertisement by the Iraqi Embassy in Washington, DC, inviting Iraqi Jews to return to Iraq

This article sheds light on the power of Jewish migration as an effective tool of resistance by rejecting the diaspora/homeland binary and racialized selective migration ethos. Examining Afro-Asian Israeli repatriation to the Arab world as an act of transgressive migration, I argue for further complication and carefulness in the study of migration to and from Israel by focusing specifically on yeridah and what it tells us about the notion of Jewish homeland. I employ the term Afro-Asian Jews throughout as it allows for a terminological framing that is not dependent solely on Israel but acknowledges the transnational, (anti-)colonial context from which Jews of Africa and Asia originate. I use the term Mizrahi (Easterners) when historically appropriate, such as when describing the Israeli Black Panthers. Rather than focusing on the commonly prescribed reasonings for out-migration, I look to the clear examples of those who left for reasons of racism and discrimination, viewing such acts as a strategy of political protest. Such a protest's efficacy is not judged by the length of time one stays abroad or if one returns, but by the power of the messaging perceived by the state institutions. The cases discussed are small in number in comparison to those who left Israel; yet, they made a huge impact on perceptions of Israeli emigres. The importance lies not in the number of repatriates but in the significance of threat perceived by the Israeli establishment. Afro-Asian Jewish repatriation sent a message that the Zionist project, particularly as the opposing nationalist movement to Pan-Arabism, was a failure. Even though the majority of Afro-Asian Jewish Israelis remained, the state saw emigres and repatriates as a serious threat in which “one Yored can do infinitely more damage than 20 people successfully absorbed.”Footnote 6

For historical context, I begin with a general overview of state-based responses to Jewish out-migrants to illustrate the difficulties faced by potential emigres. Then, I move on to several high-profile cases of Moroccan and Iraqi Jewish repatriates from Israel and the discourses surrounding their migration. I make use of government transcripts and reports, annual statistical reports, as well as the three most popular Israeli newspaper sources—Ma'ariv, Ha'aretz, and Davar—to understand the position of the Israeli state elite. To demonstrate the thinking, motivation, and concerns of out-migrants, I make use of interview transcripts from the aforementioned newspapers as well as the Iraqi Jewish Archives.

Rather than truly being concerned with the existential threat posed by the delicate balance between Jews and non-Jews in Israel/Palestine, the state does not operate under a “cult of numbers,” obsessed with Jewish demographic size—as Ruppin once opined.Footnote 7 Instead, Jewish emigres from Israel were seen as a threat to the state and Zionism due to the pathologization of Jewish mobility. Rather than embrace this, Afro-Asian Jewish Israelis who repatriated to the Arab world saw their migration as acting as a powerful statement against discrimination and racism. The discursive impact on the protest statement with leaving the country far outweighs concerns—real or imagined—surrounding the quantity of Israeli Jewish citizens residing in the country.

The article uses the terms out-migration and in-migration to describe Jewish emigrants from and to Israel, respectively. This allows for a broader, inclusive understanding of homeland and reframes questions of migration from a state-based focus to that of the migrant's perspective of home. Scholarship on Ottoman Palestine has provided a space for imagining its Jewish community as a heterogeneous microcosm of overlapping diasporic communities.Footnote 8 This allows us a more nuanced understanding of the diversity of political and societal attachments of the Ottoman Jewish community in Palestine. There is no reason to assume that this aspect changed during the Mandate Period or with the establishment of the State of Israel. Therefore, the vocabulary of migration I employ acknowledges the possibility of attachment to multiple homelands without assuming the limited categories imposed by the state.

Israeli society maintains two distinct politicized notions of migration to and from Israel: Aliyah and yeridah. Aliyah, or spiritual ascent, is derived from religious notions of entering the Holy Land, while yeridah (migration out of Israel) is a distinctly Israeli concoction that places negative value on those who migrate out of the contemporary physical borders of the state. Jewish migration to Israel is imbued with a sense that the physical act of relocation is a historic and spiritual moment for the individual and the collective, as each Jewish migrant brings the collective closer to redemption. Politically, it is assumed to be an explicit realization of the Zionist ideal. Spiritually, it is an Aliyah, a definitive ascension to the Holy Land, the logical culmination of the millennia-long Jewish desire to return to the Land. Yeridah, on the other hand, is a temporary peregrination representing a spiritual descent into—and a return to—the nebulous realm of the Diaspora. Moreover, because Israeli historiography has maintained a stark distinction between “Aliyah” and “hegira,” the immigration of various communities to Israel has been explored within a context of Israeli exceptionalism.Footnote 9 Yet, at least since the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, the Jewish imagining of Diasporic Jewish relations has included the notion of multiple homelands.Footnote 10 Not all who go up must stay.

Scholars diligently chronicle the history of the various waves of Aliyah, but few ask whether the term is appropriate or useful. Curiously, we overlook the significance of yeridah, without acknowledging the role it plays in shaping Israel's history and relationship to the Jewish Diaspora. As Ella Shohat reminds us, Jewish migration to Israel does not necessarily constitute a spiritual ascent or a definitive “immigration.”Footnote 11 Rather, it is more fitting to speak neutrally about the “migration” of Jews to/from Israel. Israeli historiography emphasizes the various waves of aliyot, or in-migration, as a means of establishing the trajectory that led to the creation of the state. However, this ignores how both out-migration and cyclical migration impacted that trajectory, the nature of the resulting societies, and the Jewish migrants themselves. Immigrants do not know in advance the extent to which they will shape, and be shaped by, their new society. Similarly, emigrants are unaware of the implications of their absence from their abandoned residences. Just as the various waves of Jewish in-migration were important in establishing the Yishuv and State of Israel, out-migrants returning to their countries of origin were instrumental in constructing and disseminating the image of the Israeli “New Jew” in the Diaspora.Footnote 12 Although little is written about Moroccan Jewish migrations to and from Mandate Palestine and their relationship to the Yishuv, North African Jewish literary works and testimonies indicate intimate knowledge of Palestine as well as circular patterns of migrations between it and the Maghrib.Footnote 13

By embracing the assumptions that lie behind such nationalistically tied concepts as that of Aliyah and yeridah, scholars are complicit in the political theology of nation-states. Based around a “solar-system model,” scholars of Jewish migration too often view the Diaspora and homeland, or center, as binary.Footnote 14 While more recent work has delved into out-migration within the Yishuv as well as from the 1950s to the 1960s, the bulk of literature takes a quantitative approach in focusing on migration to the United States after the 1980s.Footnote 15 Much of the work lacks a focus on non-European Israeli Jewish emigrants and thus leaves an incomplete picture of the nature of Israeli emigration. For Jews of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, the French colonial metropole acted as a semi-dual homeland while Italy served such a purpose for Libyan Jews. For Iraqi Jews, the homeland was made even more complicated by British citizenship status as some held the Protected Status allowing them access to the global network of Baghdadi Protected Persons regions (Singapore, Burma, UK, and India/Pakistan) while members of the socioeconomically marginalized (Iraq).

Recent scholarship points to the significance of migration in its ability to inform on the character and boundary-making process of a nation-state.Footnote 16 In the case of Israel, out-migration comes in direct conflict with the national project and spirit.Footnote 17 For Zionist institutions, Jewish mobility was emblematic of an eternal pathos of the Jewish people (Judennot) that could only be remedied by the negation of the Diaspora; a process of negation that rendered Jews geographically immobile in the Land of Israel.Footnote 18 Zionist thinkers like Max Nordau viewed the Jewish people as an atrophied body in desperate need of physical and spiritual exercise that only a nation-state could provide. Pathologizing migration, state institutions constantly tried to cure that “infamous Jewish illness known as ‘Travelitis.’”Footnote 19 Maintaining a Jewish existence outside of a Jewish nation-state was deemed indicative of a morbid desire to live in exilic anguish. This perspective was in stark opposition to, while simultaneously drawing upon, anti-Semitic tropes that rendered void the historical Jewish relationship to lands outside of Israel and ties to multiple diasporic identities.Footnote 20 We cannot truly have a scholarly examination of Jewish migration history in the region if we continue to frame our understandings of it in nineteenth- and twentieth-century politicized interpretations of religious historiography of the Jewish people derived from the context of European Jewish secular nationalism.

Recently, some scholars of Israel sought to mark as criminal certain words when describing Israel such as “apartheid,” “occupation,” and “colonial.”Footnote 21 As problematic as this “Word Crimes” issue is, it did highlight a terminological turn towards an investigation of the power our jargon holds, how Israeli exceptionalism plays out in the language we use to inadvertently prevent effective comparative studies, and why certain terms and values are deemed untranslatable to an Anglophone audience. With this in mind, I argue that we either employ the neutral term mehager or refer to Jewish migrants to and from Israel. While mehager is a term currently used for a non-Jewish migrant to Israel, extending it to Jewish migrants more accurately reflects how we do not necessarily know their intention in migrating, whether it be for economic, ideological, or religious reasons, or because of dispossession. The term “Jewish migrant/migration” provides a certain amount of precision in that, when discussing changes in the Israeli population, we are only referring to Jews. Fears of demographic threats regarding yordim are never about Palestinian citizens. Waves of aliyot are rarely concerned with the large percentage of non-Jewish citizens and non-citizens subject to Israeli rule. Making this explicit helps to identify those gaps in literature and perhaps redirect our studies away from state-inspired scholarship. For those of us who abhor the rigid constructions of nation-state boundaries, are we complicit in reifying their significance when we focus solely on the aliyot to Israel and overlook the migrations from it? In other words, are we subtly reinforcing the notion that, once a Jewish person enters the Land of Israel on a permanent or semi-permanent basis, they have undergone an ascent which marks them as forever Israeli and no longer attached to their previous histories and heritages?

Fuzzy Stats: Documenting Jewish Out-migration

At first glance, Israel's official records of Jewish out-migration are deceptively thorough. The State of Israel meticulously documents and boasts of the number of Jewish citizens under its jurisdiction every year. The systematic collection of statistics on migration to and from Palestine by Zionist organizations began in earnest with the establishment of the Jewish Agency's Palestine Office in 1909.Footnote 22

Between 1919 and 1948, nearly 45,000 Jewish migrants to Mandate Palestine were of Afro-Asian origin. From 1948 to 1968, 691,968 Afro-Asian Jews migrated to Israel making up about 55 percent of the Jewish immigrant population. In the following decade (1969–79), this dropped to 78,692 Afro-Asian Jews with European and American Jews constituting nearly 80 percent of the Jewish immigrant population.Footnote 23

In 1948, demographer Roberto Bachi established the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) as the main state-run demographic institution. Throughout its history, the CBS has found it difficult to determine when to mark a Jewish citizen as a yored, the official term it used to mark permanent Jewish migration out of Israel.Footnote 24 Frequently, the bureau revised its definition of a Jewish out-migrant as someone who has departed and not returned to the country for three, four, or five years. The CBS’ difficulty in pinpointing the transition from temporary to permanent migration presents enormous challenges in the study of patterns of migration of its citizens.

Between 1949 and 1977, the CBS’ documentation of emigres’ country of birth and destination are largely inconsistent. A major cause for this is how much statistics on Jewish migration to/from Israel are tied to Zionist ideological practices.Footnote 25 Also at issue was the difficulties found in getting accurate responses from potential emigres. Following the 1948–49 War, Israel enacted austerity measures until 1959 that left a deep impact on residents and potential emigres alike. These measures, taking place during the Histadrut's (national labor union) war on emigration, included a series of bureaucratic and financial hurdles for declared out-migrants, discouraging many from openly stating their intention to permanently relocate and further obscuring the extent of Jewish out-migration. Moreover, it was not until 1961 that Israeli citizens were no longer required to obtain an exit permit allowing them to leave the country.Footnote 26 Moroccan Jews looking to emigrate from Israel would sometimes use a vacation to France as a more palatable—in the eyes of the state—means of returning to Morocco.Footnote 27 The colonial metropoles of France and the UK would have been more attractive for those seeking financial mobility as well as those with affinities with the French and British colonial authorities within Morocco and Iraq. Moreover, there were diplomatic barriers in place for both communities. Prior to its 1956 independence, Jews who left the French Protectorate of Morocco likely had done so by illegal means—such as crossing through Oujda—while Iraqi Jews would be returning to and from enemy states.Footnote 28 Post-independence for Israel (1948) and Morocco (1956), Jews faced difficulty in traveling or immigrating to Israel. French authorities banned such travel and, in the postcolonial period, King Mohammed V, upon the urging of the Arab League, formally prohibited Jewish emigration to Israel from 1959 to 1961. When King Hassan II took the throne, secret negotiations between Israel, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), and Morocco—initiated by King Mohammed V—formed into what would become Operation Yachin (1961–64); leading to tens of thousands of Moroccan Jews emigrating to Israel during the period 1948–60.Footnote 29

Thus, the statistics do not tell the whole story. The CBS provided a tiny window into the extent of Moroccan or Iraqi Israeli out-migration from 1949 to 1976.Footnote 30 Unfortunately, its records are not always reliable for tracing patterns of migration to and from Morocco or Iraq. With Iraq being an enemy state and Morocco (both colonial and independent) greatly restricting Jewish migration to Israel, clandestine emigrations to and/or from Israel were out of the purview of official state statistics. Moreover, statistics from the CBS were largely inconsistent across time and seem to include or exclude pertinent details based on the prevailing social climate in Israeli society. To the great frustration of government officials and politicians, the office would frequently change definitions of Jewish out-migration as a means of obscuring its rate.Footnote 31 In 1953, the CBS simply did not report numbers on out-migrants and, by 1976, the long-standing practice of documenting an emigre's ethnicity ceased. Even state-appointed representatives tasked with investigating Jewish out-migration were rarely given the complete picture. Statistics on Afro-origin Jews were obscured by creating only two categories: one for South Africans and another for “Other” African countries—presumably, the entire Maghrib. Aryeh Leib (Leon) Dulzin, one of the main officials tasked with investigating the emigration of 1976, even admitted that “it is difficult to know the precise details of this topic because we don't have exact numbers and there are no statistics.”Footnote 32 Dulzin's statement was a bit misleading as the CBS and Jewish Agency did maintain exact numbers of Jewish emigres; yet they failed to coordinate and convey their definitions of what constituted a “yored” in their eyes. Given the reticence of any out-migrant to declare their intentions in an Israeli society hostile to Jewish emigration, this gives pause to how precise any government out-migration statistics would be in such an environment.

From 1948 to 1959, over 13,000 Afro-Asian Jews emigrated from Israel. During the same period, 10,687 Israeli Jewish citizens migrated or repatriated to Africa/Asia from Israel, and over 50,000 Jewish citizens migrated to the Americas and Europe.Footnote 33 Given the phrasing and categorization of CBS migration statistics, it is impossible to discern who, among Jewish emigres, were of Afro-Asian origin and migrating to the Americas or Europe nor how many Israeli citizens migrated to Africa or Asia during British or French colonial rule. This is symptomatic of a larger problem in developing reliable tools of analysis for investigating Israeli and Zionist history.Footnote 34

With multiple feelings of belonging and citizenship ties, many of those emigrating to Europe or the Americas were of Afro-Asian origin. Moroccan Jewry migrated to Israel in large numbers during the 1950s and 1960s as a result of a number of political and economic factors surrounding the fight for Moroccan independence.Footnote 35 Prior to 1948, Iraqi Jews, particularly those with British Protected Persons Status, had several options as to where to migrate, either within the UK or its colonies.Footnote 36 The large-scale movement of Iraqi Jews to Israel primarily occurred in 1951–52 with over 100,000 Jews departing. The 1941 farhud—a two-day series of violent attacks against the Jewish community of Baghdad—as well as state-supported conflations of Jewishness and Zionism following the 1948 War led to the departure of over 100,000 Jews from Iraq to Israel between 1950 and 1951. Those who left were denaturalized along with having property rights frozen. The Moroccan Jewish community had ties throughout the Americas, and a large portion of Maghribi Jews of various origins held French or Italian citizenship. Such emigration options, out of Morocco and Iraq, were primarily available to wealthier families until the Zionist movement made concerted efforts to recruit members of the lower socioeconomic rungs. One of the major impediments for Afro-Asian Jews who wanted to return to their countries of origin was that the post-independence countries of Egypt, Iraq, and Algeria had stripped Jews of their citizenship upon their departure. Syria and Lebanon, albeit enemy states bordering Israel, often acquiesced to the repatriation of Israeli citizens who crossed into their territory. Others, such as Morocco, were not economically viable destinations, and in all cases, the societies to which emigres returned had changed drastically as they entered the early postcolonial era. In some cases, Jewish repatriates found themselves subject to surveillance by the Israeli government even within their countries of origin.Footnote 37 Moroccan Jews were subject to surveillance by both Zionist emissaries to Morocco and Moroccan authorities, who suspected repatriates to be active agents of Israel. Following Moroccan independence, members of the conservative monarchist Istiqlal Party raised concerns that Moroccan Jews who returned from Israel were acting as a potential fifth column. While the State of Israel viewed them as defectors, their status and political beliefs were questioned in Morocco as well, leading to the detainment of repatriated Moroccan Jews who continued to hold Israeli passports.Footnote 38

Throughout Israeli state history, the Knesset and Jewish Agency formed committees to address the out-migration of Jews. Named like war operations, yeridah committees, such as the “Unit to Combat the Problem of Yeridah/Yordim,” were formed well into the 1980s. The earliest such committee was headed by Shlomo Shragai (the first mayor of Western Jerusalem and head of immigration for the Jewish Agency), who reported its findings in 1954. Framing his report around concerns about how out-migration reflected upon Israeli society, Shragai—like others after him—focused on the prevalence of institutional discrimination against Afro-Asian Jews as a significant catalyst to emigration. Pointing out that some immigrants were unable to create a new way of life in Israeli society after “being torn from social life in the galut” the Shragai report placed much of the blame for the issue of out-migration upon incoming migrants. Shragai, however, acknowledged that “there is no doubt that there is ethnic prejudice [and] ethnic discrimination” against Afro-Asian Jews, and he also noted the “possibility” of “some prejudice within the division of labor.”Footnote 39 For youth and those of working age, racial prejudices had a significant impact on their social integration. Afro-Asian Jewish migrants accounted for 90 percent of employment-seekers, and age and race discrimination played a significant part in their inability to find work. Those over the age of fifty—many with families to support—found it near impossible to be registered at employment offices and received little to no assistance from welfare offices or the Jewish Agency. Experiencing such institutionalized discrimination, many wanted to emigrate. In response, Shragai suggested that government ministries, the Jewish Agency, Histadrut, and HMO clinics, among others, should be compelled to “take action to serve workers of the [Eastern] extraction.”Footnote 40 Yet, at the same time, Shragai saw it prudent to find ways to prevent their leaving Israel.Footnote 41 He pushed for the police and Aliyah services to implement “drastic measures of supervision over the activities of various entities and the actions of those who assist olim to emigrate from Israel to the lands of the Golah.”Footnote 42 However, Shragai felt such a move would be unpalatable for the general public and thus added a handwritten note that the draconian methods he suggested were to remain confidential and “should be [hidden from] publication.”Footnote 43 It was time to wage war on out-migrants.

Taking a carrot-and-stick approach, the committee pressed the government to institute measures that would both encourage migrant retention and discourage emigration through surveillance and punishment. This would be done by establishing a permanent intra-ministerial committee including Jewish Agency representatives who would be tasked with investigating out-migrants. Absorption departments were to hire additional staff to address it amongst incomers, with special attention paid to Afro-Asian Jews. Youth were to receive stipends for vocational training. Staff were also hired to act as leadership figures in Afro-Asian women's organizations so as to instruct women on how to properly manage a household that would remain in the country. While not all immigrants were considered desirable—Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion celebrated the removal of the “idiots and psychopaths” among young Moroccan Jewish migrants—Israel's selective migration policy focused greatly on retention..Footnote 44 The Histadrut aided in Jewish retention in Israel by first recognizing that at least one third of Jewish out-migrants were heads of households and members of Histadrut, and consequently, the labor union punished any Jewish citizen who left—for vacation or emigration purposes—by freezing their pension funds and social security until they returned to Israel.Footnote 45

A decade after the Shragai Commission, state officials debated on a core issue concerning the nature of Israeli citizenship: the rights extended to those who leave. Using US passport laws as a template, they decided that citizens’ rights did not extend to out-migrants. The committee was tasked with investigating the legal principles that would allow the state to punish yordim by prohibiting any consular service abroad to “citizens who turned into yordim,” including denial of passport renewals, except in order to assist them in returning to Israel.Footnote 46 In essence, the act of permanently—or even semi-permanently—leaving Israel as a Jew became betrayal to the Jewish nation, which the state took a multifaceted approach to punish and deter.

The Israeli War on Jewish Migration

For Israeli Jewish citizens, out-migration in the 1950s and 1960s was no easy feat. Fishermen smuggled migrants off the coast of Ashkelon, teenagers snuck across the Lebanese and Egyptian borders, and hundreds of Israelis were detained in German Displaced Persons (DP) camps after unsuccessful emigration attempts. Groups of immigrants held informal kangaroo trials in absentia against out-migrants, while organized caravans of women and children looked for a sympathetic Arab or European country for resettling.Footnote 47 Potential Afro-Asian Jewish out-migrants struggled hard to manage societal perceptions of their departure, conscious of the fact that the state would label their assumed betrayal of the homeland as due to their inability to acclimate to Western modernity. For example, Jews from India/Pakistan held a series of hunger and sit-down strikes against the Jewish Agency from 1951 to 1955 demanding that Israeli state institutions return them to their homeland due to institutionalized racism directed against them.Footnote 48 These protests drew international attention, including from the South Asian Jewish community, who debated the veracity of the claims as well as the merits of potentially migrating to an unwelcoming Israeli society.Footnote 49 Shlomo Lorentz of the Agudat Israel Party estimated that, from 1948 to 1951, Jews from Asia constituted about 10 percent of Jewish out-migrants.Footnote 50

Even if someone successfully crossed the border, there was no guarantee that they could remain out of the country. Some Afro-Asian Jewish immigrants who crossed into neighboring countries were forcibly returned to Israel, yet continued their efforts to leave. Baghdadi Jewish novelist Samir Naqqash, for instance, attempted to flee Israel repeatedly, with his initial attempt taking place at age fifteen. He and his brother crossed into Lebanon in order to return to Iraq but were detained and returned by the Lebanese military.Footnote 51 Israeli emissaries, particularly those in the Moroccan Protectorate, sent investigative delegations to search for and return emigres. At other times, policing societal norms around religious behavior prevented Jewish citizens’ mobility. In one instance, a woman ordered the rabbinic courts of Ramat Gan to impose an exit ban on her husband who had already embarked on the “Theodor Herzl” ship sailing to Marseilles. The religious court telegrammed the captain after it was revealed that the couple were involved in “arguments and an improper way of life.” Just two days later, the twenty-two-year-old husband was forced to return to Israel on the same ship upon which he departed.Footnote 52

Unless explicitly stated, it is difficult to decipher the intentions of emigrants. Even if economic reasons seem likely, we cannot dismiss the possibility that the political and social environment, too, lay behind decisions to leave.Footnote 53 In the same vein, we should not assume that all Israeli citizens who remain in the country did not, at one point, seriously make attempts to emigrate. This is truer considering the conditions prevalent during the period of austerity. The seemingly inescapable horrific conditions of the ma'abarot—temporary residences comprised of tent encampments and tin shacks—still haunted those who survived them with their lives, psyche, and sense of self intact. Scholars have only recently begun to uncover the extent of the tragedies faced by incoming Jewish migrants at these camps, some of which—unbeknownst to many—existed well into the late 1980s.Footnote 54 Upon arrival in Israel, migrants were placed under quarantine in the Sha'ar Ha'Aliyah camp, on the western side of coastal Haifa, for indeterminate amounts of time. From there, they were assigned to ma'abarot where they would be isolated from employment opportunities and subject to daily curfews and police surveillance.Footnote 55 With unsanitary living conditions, no access to healthcare, and little to no communication with the outside world, life in the ma'abarot disproportionately reduced Afro-Asian Jewish Israelis to a poverty and isolation akin to social death. Many were unable to leave unless in possession of a European passport. Repatriate Jews from Morocco fared better than those from the Levant as they were not from an “enemy state” like Iraq. With the end of French rule over the Maghrib, many North African Jews were able to apply for French citizenship. Iraqi Jews were left with few options unless they maintained a protected British subject status.

A letter to then prime minister Levi Eshkol (r. 1963–69) acknowledged that keeping migrants’ socioeconomically immobile was an ongoing absorption policy to increase and retain the Jewish population. To ensure favorable retention rates, Zionist leaders implemented recruitment plans that favored Jewish in-migrants who were unskilled laborers; a human material unsuitable for leadership in nation-building, yet useful as cannon fodder and menial tasks. Such plans explicitly targeted those without means to return and so encouraged demographic increases in the Israeli Jewish population. Preventing out-migration by disenfranchised Jewish migrants also guaranteed that the state controlled the narrative about conditions in the country. As one Zionist leader remarked, Jewish out-migrants were effective in discouraging potential in-migrants since “one Yored can do infinitely more damage than 20 people successfully absorbed.”Footnote 56 This was particularly true for Moroccan and Iraqi out-migrants to Europe where large populations of North African and Arab Jewish communities resided who were well attuned to the nature of anti-Afro-Asian prejudices.

Even migration to Europe proved difficult. Despite the postwar taboo of migration to Germany, many Israelis emigrated there to pursue social mobility. By 1953, Germany required all Israelis residing in the country to register with the state. In one case, over a dozen Israeli out-migrants were about to be deported from Germany until the American Joint Distribution and Jewish Agency intervened and expressed their concern.Footnote 57 Those without papers were called “infiltrators” to Germany by Israeli newspapers, who noted that hundreds of Israeli out-migrants were present in the country and over 600 were detained in the Föhrenwald DP camp.Footnote 58 At the same time, a caravan of forty-four Israelis organized their emigration to Europe but were forced into the Salzburg DP camp—in preparation for deportation—after Italy and Austria refused to permit their stay.Footnote 59 Nevertheless, by the 1960s, there was “a ‘colony’ of [Mizrahim] that emigrated from Israel” to Frankfurt, Germany, where they were building successful small businesses throughout the city.Footnote 60

The policing of Jewish mobility extended beyond the borders of the state. One German-Jewish Israeli, Walter Fuss, fled Israel to Damascus along with eight others in November 1954. After appearing on Radio Damascus, where he criticized the State of Israel, he emigrated to Berlin, where his father worked as an official in the Berlin Municipality's Sanitation Department. While there, he, the others who traveled with him, and even some of their close family members were excommunicated from the Berlin Jewish community.Footnote 61 This incident demonstrates the blurring boundaries of Israel and the Jewish Diaspora—how the punitive nature of leaving Israel bled into how Jews in the Diaspora perceived themselves and their relation to the State of Israel.

Israeli newspapers aligned with the ruling Mapai Party circulated tales of out-migrations, invariably serving to induce fear and disparage the Jews who emigrated, as tricksters and layabouts. Various measures were put in place to address Jewish out-migration including publicizing letters and testimonies about the hardships faced by emigres within their destination countries. These were distributed in newspapers and on the radio station Kol Zion LaGolah (The Voice of Zion to the Diaspora). In announcing the Histadrut's aggressive “war,” Ma'ariv presented a few cases, including that of a Holocaust survivor whom the newspaper depicted as an alcoholic gambler unable to find work for years until he left with his wife to South America. One recent migrant from Brazil, upon hearing rumors that the Histadrut would help those intending to emigrate to find work, tried to use it as an opportunity to gain employment. In Ma'ariv's treatment of his case, however, he attempted to extort the Histadrut by threatening to emigrate and return to Brazil unless they provided him employment in the Solel Boneh construction company.Footnote 62

“That's Enough. We're Going Back to Morocco”: Out-migration as Protest

In the wake of the 1967 War, the number of Palestinians living under Israeli jurisdiction increased dramatically consequent to the occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, and Sinai Peninsula. Ever cognizant of the supposed “demographic threat” posed by a Jewish minority, Jewish out-migrants presented a direct existential threat to the state. Yet, Jewish out-migration from Israel reached a peak in the 1970s. Vast changes had begun to sweep through Israeli society toward the end of the previous decade. Televisions appeared in more homes and international events gave the impoverished a new sense of hope. The May ’68 revolts in France and the global Black Panther Movement originating in the US inspired a new generation of Afro-Asian Jewish youth. In this context of global dissent, many Jews felt emboldened to leave Israel. In 1972 alone, about 18,000 Israeli Jews permanently emigrated from the country, the largest recorded number since the state's founding.

For Afro-Asian Jews, feelings of alienation and discrimination undergirded their desire to emigrate. While the first two decades of the state saw near-daily protests against government institutions, Mizrahi protests in the 1970s critiqued the character of the state itself with the emergence of the Israeli Black Panthers in 1971. Established by a group of Moroccan and Iraqi male youth, the Black Panthers hold an important place in Israeli history as they put the Ashkenazi-Mizrahi divide on the forefront of discussions about the character of Israeli society. Subject to police brutality, the Israeli Black Panthers shaped the minds of Mizrahi youth nationwide, organizing protests to hold the government accountable for racial inequalities.Footnote 63 The linkages between Mizrahi out-migration and racial inequality are most apparent as one of the Black Panthers’ major grievances involved Prime Minister Golda Me'ir's (r. 1969–74) push for Jews living within the Soviet Union to immigrate to Israel. For Mizrahi youth who inherited a generation of impoverishment, the push for Russian in-migration appeared to be a tactic to offset the population of Mizrahim, who constituted the majority of Israeli Jews. Shalom Cohen, one of the leaders of the Israeli Black Panthers, visited France and called upon French Jews to help fight against discrimination in Israel. He, along with other Israeli emigres and leftist French intellectuals, appealed to the North African French Jewish community to join them in their struggle against what he described as a “cultural genocide.”Footnote 64 After decades of discriminatory practices in housing, employment, and cultural and governmental institutions, for some it seemed unlikely the ethnic divide between Jews would ever be bridged. There was a growing feeling that Mizrahim had been used by the state but were granted little to no recognition for their contributions to its development. Part of this had to do with a renewed sense of empowerment sparked by the emergence of the Israeli Black Panthers in 1971, disappointment with Mapai leadership following the 1973 October War, and the shifting tone of Arab states toward Mizrahim in Israel. Golda Meir's cabinet received the brunt of criticism for perceived intelligence failures in its handling of the 1973 War.Footnote 65 Listening to the pleas of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), members of the Arab League as well as revolutionary Arab militias began to take seriously the PLO's cautionary appeals to protect the remaining Jewish populations in the Arab world.Footnote 66 In 1976, this came to a head when international newspapers reported on “defections” to the Arab world by Moroccan- and Iraqi-Israeli Jews. With reports of 1,000 Moroccan Israeli repatriates and hundreds more expected, the Israeli government took this seriously. This anxiety over emigration helps explain the 1977 Israeli elections, which saw the rise of the right-wing Likud Party. Known as the “mahapakh” (revolution), the 1977 elections are widely thought to be a result of the complete lack of confidence, primarily amongst Mizrahi voters, in the Labor Party that had ruled the country from its founding.Footnote 67

Arab leaders encouraged Afro-Asian Jewish repatriation to the Arab world throughout the 1970s. During the 1974 Arab League Summit in Rabat, the participating countries agreed to recognize the PLO as the sole representative of the Palestinian people. At the same time, countries with historically Jewish populations were encouraged to facilitate Afro-Asian Jewish repatriation, particularly from Israel. To support this offer, a number of Arab states, including Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the Sudan, and Morocco, created a fund totaling five million dollars as a means of easing the transition of Jews back to the Arab world.Footnote 68 The Beirut-based PLO's Political Department led this campaign in order to underscore strategic interests: namely, to emphasize that Zionism was racist against Arabs—irrespective of their religious identity as Jews, Christians, or Muslims—and to dissuade further Jewish emigration from the Arab world to Israel.Footnote 69 The funding for the proposal was a cynical means of creating a catalyst for the ʿawda, or the return of Palestinian refugees to their own homeland, pitting Arab (Jew) against Arab (non-Jew). In 1975, the Revolutionary Command Council of Iraq invited all Iraqi Jews who were not Zionist to return to their homeland. Other Arab League members, such as the Sudan and the Arab Republic of Yemen, joined in the appeal to non-Zionist Arab Jews.Footnote 70 The following year, King Hassan II urged Moroccan Jewry to “return to their homeland from wherever they may be, even those who are in Israel.”Footnote 71 As a publicity stunt, Iraq purchased a half-page advertisement in the New York Times welcoming Jews back to their homeland.Footnote 72 There was some opposition to the funding of this project within Morocco, since the country had suffered a large economic crisis and had recently annexed the Western Sahara. However, King Hassan II was adamant in funding the repatriation efforts and planned to provide for an enclave of some 200 Moroccan Israelis in the city of Rabat. The king's invitation prompted suspicions that large waves of out-migration by North African Jewry would continue. Headlines in Israel warned of an organized emigration movement formed in Ashdod and Kiryat Gat, cities with large Moroccan populations. The organizers had already convinced nearly a dozen families to attempt to leave the country out of protest.

Individual acts of out-migration in the 1970s emphasized the transgressive nature of leaving Israel as a Jewish person. One of the most publicized instances of migration as dissent involved Nissim Saroussi, a Jewish singer of Tunisian origin. During a 1975 interview on the popular Tandu television program, TV presenter Yaron London ridiculed Saroussi and Mizrahi culture in general. He expressed shock that someone of Saroussi's appearance and stature could become a popular celebrity. While showing Saroussi's heels to demonstrate his short height, London asked: “Who are you at all? Lil’ tiny Nissim. You're not tall…Who are you that you are an artist? You are, at best, a little bitty Sephardi. An irrelevant person.”Footnote 73 The original tapes of this particular episode are assumed to be lost and irretrievable. However, the memory of the occurrence still lingers in the minds of Israelis. Despite London's claims that the comments were made innocently and without prejudice, he later admitted to receiving thousands of letters praising him for putting “the Frenks”—a derogatory term for Mizrahim—in their place. In the documentary film Yam Shel Dema'ot (Sea of Tears) Saroussi revisited his feelings about the interview. He recalled that he felt like he was “being interrogated or on trial” and that he had to defend Mizrahi Israelis who enjoyed his music or, as the newspapers called it, “trash songs.”Footnote 74

While Saroussi focused on the personal humiliation the incident was for him, others such as activist and educator Tikvah Levi emphasized what the public nature of the interview did for Mizrahim across the country: “This wasn't a humiliation of Nissim Saroussi…Yaron London, in one blow, trampled upon all of us (Mizrahim)…”Footnote 75 After the London interview, Saroussi attempted to leave Israel in search of a more embracing society. This proved initially difficult. In October 1975, he was subject to a stop-exit permit preventing him from leaving the country without paying a debt of 2,000 lirot.Footnote 76 In 1976, however, Saroussi left Israel for France in protest against London's—and more substantially, the Israeli entertainment industry's—treatment of Mizrahim. In a telephone conversation from Paris, he announced that he was emigrating from Israel “because they are chasing him.”Footnote 77

Saroussi was not alone in his reasoning for emigration. The issue of racism as a catalyst for emigration came to a head later that very year. This was 1976, the year Israel released the disheartening demographic report that prompted Rabin's brash dismissal of emigrants. Rabin went on to call for saving “the remnants of [Jewish] communities in Arab countries where they are held hostage,” thus invoking the rescue narrative that scholars have since deconstructed.Footnote 78 Following Rabin's comments, a writer to the Davar editor recalled the Saroussi incident. He noted a clear double standard in how Israelis related to yordim based on their ethnicity and social class. If a young, homeless, and unemployed Israeli emigrated, the person would be condemned as weak and suffering from Diasporic mentality. Yet, if a wealthy person emigrated in order to accumulate wealth or for professional opportunities, it would be seen as a temporary migration and not worthy of condemnation.Footnote 79 Here, the letter writer points out that Israelis only refer to an emigrant as weak or betraying the homeland—even when the intentions are the same—when they are of lesser social standing.

A week after Rabin's interview, rumors continued that waves of Moroccan Jews were readying their departure. Israeli newspapers began to pay more attention to these supposed “large-scale defections of Jews from Israel.”Footnote 80 The papers reported that Moroccans were fleeing the country en masse and that other “rabble rousers,” such as union leader Yehoshua Peretz, were threatening to organize a mass exodus. Davar reported on hundreds of Moroccan families selling their possessions and packing their suitcases in anticipation of an organized mass migration back to Africa. Iraqi Jewish Israelis could be heard on Baghdadi national radio encouraging Iraqi Jews to follow suit and “return to the homeland.”Footnote 81 If Israel was the savior of Afro-Asian Jews, as Rabin asserted, why would they return to countries holding them hostage?

Officials struggled to find root causes. Mapai politicians formed emergency committees; mayors of predominately Mizrahi towns scrambled to uncover who or what was behind these sudden departures. Some thought that Dani Sa'il, an Israeli Black Panther who later disappeared under mysterious circumstances, was working with Palestinian militants to fund and encourage repatriation.Footnote 82 But a range of Mizrahi public figures, from Mapai politician Asher Hassin to labor union champion Yehoshua Peretz, pointed to another catalyst: anti-Mizrahi prejudice and social inequality.

Afro-Asian Jewish Israelis, facing years of anti-Black/Brown prejudice, inequalities in the labor and educational markets, and housing segregation spent the previous decades fighting a civil rights struggle from within and, now, many were prepared to vote with their feet. Yehoshua Peretz pointed out that widespread discrimination was the main reason for unfounded reports claiming that he would stage a mass repatriation effort to Morocco if his union's demands were not met. In response to increased out-migration from Israel, Minister of Education Aharon Yadlin proclaimed that Israel “do[es] not have a racial problem…Our problem is fundamentally one of bringing up to modern standards…the children from the Oriental countries, whose families are far behind those from the Western countries.”Footnote 83 In stating that “there was no parallel in Israel for the goal of racial integration,” Yadlin missed an opportunity to engage in productive exchanges of ideas about methods to promote racial equality.Footnote 84 At the same time, he presupposed Mizrahi primitivism and the inability of Israel-born Afro-Asian Jewish children to acquire a proper education, purely based on their ethnic origins.

The state's response to increased rates of out-migration was to publicly deny the phenomenon's existence while privately raising alarms about it. Yet, at the same, in order to determine the extent of these emigrations, three representatives from the World Federation of Moroccan Jewry traveled to Morocco to investigate. Sha'ul Ben-Simhon, heading the delegation, concluded that there was no basis to the claims of mass emigration after they found no Israeli Moroccans present. He also went on to highlight that few Mizrahim repatriated back to the Arab world, with the majority living in France and North America.Footnote 85 However, Ben-Simhon (in his capacity as the chair of the World Union of North African Jews) stated, “The information in the government's hands regarding yeridah to Morocco is far more serious than publicly acknowledged. But I prefer for the present to deal with this matter quietly and without publicity.”Footnote 86 Ben-Simhon's official report provided the Israeli government with what it wanted to hear: “not one yored was found in Morocco.”Footnote 87 Yet, informally, he hinted—via an interview on Israeli army radio station Galei Tsahal—that there may have been some truth to the rumors.Footnote 88 Pointing out that racial prejudice rather than poor socioeconomic conditions lay behind the phenomenon, Ben-Simhon maintained that those who were contemplating leaving Israel included those with socioeconomic stability.

Labor Party representatives held an emergency meeting in the Western Negev development town of Sderot following televised interviews with North Africans who had already sold all their property in preparation for return. Asher Hassin, former Knesset representative for Mapai and then president of the Union of North African Immigrants, held a press conference to assuage fears that the stability of the Jewish state was undermined. Hassin acknowledged that amongst many of the out-migrants were army-aged youth as well as established businessmen whose names remained unpublished.Footnote 89 Hassin minimized the significance of the emigration rates, characterizing them as natural and ordinary, the result of individual decisions rather than systemic problems.Footnote 90

Aryeh Dulzin, treasurer of the Jewish Agency and the Histadrut, publicly condemned the rumors as gossip and “poisonous propaganda of the PLO and Arab leaders.” Yet, at the same time, Dulzin recognized that the phenomenon was connected to discrimination and social gaps between Ashkenazi and Afro-Asian Jewish Israelis. He hosted a delegation of European Sephardic leaders in order to explore solutions to these issues. In addition to suggesting improved educational opportunities, the French delegation made promises to do everything they could to “prevent emigration and repatriation of Jews of Arab origin to return to their countries.”Footnote 91 Although Dulzin initially cast doubt on whether Israeli Jews in fact repatriated to the Arab world, statistics released by the Jewish Agency convinced the public otherwise. By June 1976, the agency reported that at least 300 Moroccan Jewish families a month were emigrating from Israel.Footnote 92 Hassin presented a letter to the government that contained the formal request of over 2,000 Moroccan Israeli Jews to Morocco's King Hassan II for repatriation.Footnote 93 City officials in towns throughout Israel's southern region—largely populated by Moroccan Jews—found hundreds of families with their suitcases “packed and ready to leave.”Footnote 94 Hassin claimed he was able to convince the families to stay. He placed the blame on the “disgruntled” and anti-Zionist “leftists” in Israel and France. In his capacity as chairman of the Jewish Agency, Yosef Almogi called those who left “weak human beings” who were worthy of condemnation unless they returned to Israel.Footnote 95

Mathilda Guez, a Tunisian-origin parliamentary representative of the Rafi Party, expressed even stronger condemnation of Moroccan emigrants: “Thank God that Tunisian Jews are not emigrating…Let them go to Morocco. Within six months they will regret it until the day they die, and they will never be forgiven. Not in this world and not in the next.”Footnote 96 Guez's castigation underscores the religious rhetoric underlying distaste for Jewish migration from Israel. Carrying out an act of emigration was not just a betrayal of the nation-state homeland; it was an unforgiveable cardinal sin that would have a detrimental impact on the emigrant's afterlife. While Guez's reaction was quite extreme, the cooptation of religious history in framing Jewish emigration peppered the discourse of those sympathetic and antagonistic toward those who left. Quite common in the pre- and post-state period of Israel, Zionist leaders often framed both immigration and emigration within a religious context—despite its secular nationalist drive—with all of its rewards and punishments.Footnote 97 Through a carefully curated usage of Jewish historiography, Zionists framed the State of Israel as the “Third Jewish Commonwealth,” demonstrating that myth-making for nation-states involves a process of selective memory, or more accurately, active forgetting.Footnote 98 Similarly, in his work on the Israeli emigration crisis in the 1980s, Zvi Sobel points to yeridah as potentially the major problem burdening the “Third Jewish Commonwealth.”Footnote 99 As the third Jewish state, issues of migration are intimately tied to religiously based notions of Jewish migration and relation to Israel and the Diaspora making for a very powerful, near-infallible rhetorical and legitimizing tool for enticing newcomers and deterring potential out-migrants.

In light of growing concern over the persistence of inequalities between Mizrahim and Ashkenazim, Afro-Asian Jewish out-migrants—and those who merely threatened to emigrate—used their migration as a method of protest. Threats of repatriation helped to direct media and government attention to the social ills plaguing the Afro-Asian Jewish community, such as poverty and lack of adequate education. Yet, some Israelis felt that this was a form of blackmail. For example, one writer to Ha'aretz maintained that the use of emigration to highlight social ills constituted not a legitimate protest tactic but “the most dangerous and shameful” form of extortion that is used by many Israeli Jews.Footnote 100

Reporters who interviewed North African Israeli Jews found them to be quite explicit about their reasons for emigration. Jacques, a Moroccan Israeli, maintained that “the main point is that we are thought of as third-class citizens [ezraḥim sug gimmel]…The Ashkenazim established against us a regime of harassment and persecution, of arrests without reason, a regime of white and wealthy rule over the black and poor [shilton halavan uhe'ashir al hashachor ve'oni].” Jacques continued by explaining the lack of resources available to Mizrahi Jews: “You are a white Ashkenazi…all you have to do is pick up the phone and you'll receive everything.” For some Israeli Jews, it was only outside of Israel that they understood themselves and were interpellated as Israelis. Within Israel, the Jewishness of Afro-Asian Jews was muted and silenced as they became a person from their country of origin (e.g., another Moroccan, Iraqi, or Yemenite). But, upon their departure, some Afro-Asian Israelis were able to live freely as Jews, Moroccan Jews, or even Israelis: “Here [in Israel] no matter how much I earn I will always be a Moroccan while [abroad] I'm just another Jew.”Footnote 101 In Israel, the Jewishness of Afro-Asians is undermined by their ethnic origins; abroad, their Jewishness as Israelis is overdetermined and taken for granted.

When asked why his family were choosing Morocco in particular, Jacques responded with a question to the Ashkenazi Israeli community: “Why do you Ashkenazim make such a commotion when we return to Morocco? There was never a Shoah there, au contraire, there they treated Jews with respect.”Footnote 102 More pragmatically, he also voiced his fears that the Israeli government would “chase after” them if they migrated to a country with an Israeli embassy. This has some bearing in truth in that Israeli delegations often conducted search operations for dissident Israeli Moroccans who repatriated. Jacques's uncle Albert added that, historically, Jews in Morocco were treated with respect until the emergence of French colonialism: “We never suffered in Morocco. If there were ever oppression there, it was done by the French government. The Arab authorities treated us always with great respect.”Footnote 103 Warning that soon thousands of Israelis would repatriate to Morocco, Jacques summed up the frustrations of his generation:

We've had enough of this country…twenty-eight years we put up with you Ashkenazim and we didn't become affluent from the [Wadi Salib and Black Panthers] riots that the Blacks did against the whites. So now we're saying: Thanks. That's enough. We're going back to Morocco.Footnote 104

Jacques’ statement points not only to the usage of migration as a tool for protest but also to the legacy of the racialization of Afro-Asian Jews and the place that the Wadi Salib Rebellion and the Israeli Black Panthers hold in the history of intra-Jewish race relations in Israel. Jacques’ question to “you Ashkenazim”—a moniker for the state—was warranted since only around 20 percent of Jewish out-migrants were newcomers from Afro-Asian countries.Footnote 105

Whether or not there were large-scale out-migrations from Israel during this time, the mere threat of voting with their feet brought the issue of racially based socioeconomic inequalities to the forefront, with Zionist institutions making it their top priority to improve the socioeconomic conditions of Mizrahim.Footnote 106 In response to these transgressive migrations, the Jewish Agency budgeted over 200 million dollars to “close the social gaps” between European and Afro-Asian Jews.Footnote 107 But the World Sephardi Federation noted that Israel could not compete with the Arab world with regard to Middle Eastern Jewry since “Arab countries are becoming stronger, not just in the sense of military strength, but also with regard to raising a new generation of highly skilled and educated people” while Israel lacked the appropriate motivation to cultivate such a generation.Footnote 108

The repatriation of Iraqi Israelis provides some of the more fascinating examples of this type of protest. Kiryat Atta resident Yosef Salah Nawi, for one, was drawn to the possibility of returning to an idyllic past and to escape the deprivation of development towns. Nawi emigrated to Israel in 1951 at the age of twenty-two where he was placed in the Kiryat Nahum ma'abara.Footnote 109 In 1975, the Nawi family, twenty-year residents of Israel, journeyed to Baghdad from Israel via Cyprus. While there, he held press conferences and appeared on Iraqi national radio, bringing further international attention to anti-Mizrahi discrimination in Israel. During his initial press conference, Nawi explained his decision to traverse the boundaries of enemy states: “I did not feel that I belonged—not to the government, not to the people, not to the land [of Israel].” Iraq, not Israel, was his Jewish homeland. His migration was an Aliyah to Iraq, an escape from an Israeli society he thought to be full of “enough hate [to fill] all the earth.”Footnote 110 Nawi expressed indignation that Baghdad's remaining Jewish community were acting “like inmates in a sanitarium…living at the end of their lives dreaming of Israel and hating the Iraqi government.”Footnote 111 His wife, Saʿida, waxed nostalgic over Iraq's Hashemite era and gushed over her visit to her hometown of Miqdadiya.Footnote 112 She explained to reporters in Hebrew that, “Here [in Iraq], people loved the regime and not like in Israel where everyone waits for [its] downfall.” With her Arabic-accented Hebrew, Saʿida's curious usage of the past tense (“loved the [Iraqi] regime”) betrayed her waning affection for Iraq. The cosmopolitan, diverse Iraq that she longed for in Israel was no more (Fig. 2).Footnote 113

Figure 2. Jordanian newspaper interview with the Nawi family [Pictured: “The fugitive Israeli family [coming from] hell along with the founder of al-Destour" (center top); Saʿida Naḥum [Nawi] (bottom left) and Yosef Nawi (bottom right)]

Despite his contempt for Israeli society, Nawi's family appears to have been torn between an Iraqi homeland of the past and its contemporaneous realities. Hundreds of thousands of Jews left the country between 1951 and 1952, leaving a small Jewish population. The country underwent numerous coups in the 1960s, concluding with the brutal consolidation of power by Saddam Hussein. Jewish life under Hussein was far less rosy than the Nawi family suggested. Several years prior to their return, the Baʿth government executed nine Jews—purported spies for Israel—in a grotesque public hanging celebrated by a crowd of thousands. In response to international condemnation, Baʿth Party spokesmen argued that it was Israel, not Iraq, who oppressed Jews. Nevertheless, flight from Hussein's brutality had reduced the once thriving Baghdadi Jewish quarter of al-Batawin to a few synagogues and schools. After a year in Baghdad, Yosef Nawi's voice grew increasingly weary during radio broadcasts. Eventually, Nawi and his family returned to Israel, where he was promptly arrested for entering enemy territory.Footnote 114 His pregnant wife and children moved to Petah Tikvah, where—homeless and on the brink of starvation—they applied for housing benefits with little success due to the stigma attached to their migration story. Eventually, after much debate, the Nawi family received assistance from the state “on humanitarian grounds.”Footnote 115 After serving three years of a five-year sentence, Nawi was released from prison in 1980. By then, his wife and children had allegedly cut ties with him.Footnote 116

In a case like Nawi's, Ramat Gan resident Ya'akov Oved returned to Iraq in 1976 and remained there until April 1978.Footnote 117 Oved would broadcast radio appeals for Iraqi Israelis to return to their homeland due to discrimination in Israel. Yet, two years later, he left Baghdad for Europe. With stalwart resolve, Oved used his migration story to decry discrimination in Israel. Upon arriving in Vienna, he made several unsuccessful attempts to seek asylum with American and European embassies.Footnote 118 Forced to return to Israel, he was arrested for broadcasting anti-Israeli sentiments and divulging classified information to an enemy state.Footnote 119 In defense of his actions, he stated that he was not Israeli but was stateless. Thus, “according to the laws of the United Nations,” he could not commit any crime involving an enemy state.Footnote 120 Nevertheless, Oved was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment. His return allowed his transgressive migration to be more politically effective; his arrest and trial publicized his act of protest.

Less than a month after Oved returned to Israel, another Iraqi-Israeli repatriate appeared on Iraqi radio. Dawud Yamin Mordukh, interviewed eighteen months after his repatriation, explained that he repatriated from Israel in direct response to the Arab League's invitation.Footnote 121 Unfortunately, much of the transcript had deteriorated by the time the American occupation forces uncovered and restored it. What can be discerned from the text is that Mordukh lived in Or Yehuda and still had close friends and family who remained in Salma and Kfar Shalem. Mordukh began his interview by recalling the story of Oved and the “inhumane treatment” given to him by the “rulers of Tel Aviv.” The interview, of course, was propaganda for Saddam Hussein's burgeoning regime, as Mordukh spoke of how the state offices of the Jewish religious community were like towers and palaces. According to Mordukh, life for Jews who “were not displaced from Iraq” was such that the Jewish community thrived as a “nation within in a nation” and “the Iraqi Jewish leadership live the lives of princes precisely as narrated in the 1001 Nights.”Footnote 122 Mordukh pointed out that his decision to return to Iraq was motivated by the “overwhelming joy” he felt when the Iraqi Revolutionary Command Council encouraged Iraqi Jews, provided they were not Zionists, to return to their country of origin.

Revealingly, Mordukh's main critique of Israel was the feeling that Afro-Asian Israelis were not treated as “Israeli Jews” or even just Israelis but as “an Israeli Jew from…Egypt, Iraq, Tunis, etc.” This, he noted, was most noticeable in the identity cards carried by Israeli citizens that indicated their ethnic origin: “If the Zionists claim that all Jews who immigrate to Israel are Israeli, then why and how can they logically call this Jew an Iraqi Jew?…they should say that this Jew is an Israeli Jew.” This feeling of alienation, of being treated as an Arab foreigner among brethren, caused one to repatriate. These were not opportunistic migrations or attempts at social mobility; they were protests to raise awareness about social inequality. In Iraq, Mordukh claimed, he could live freely as a citizen like all others. Using the Arabic term “waṭan” (homeland) to describe Iraq, Mordukh spent much of the interview comparing his time there with life in the “Zionist state.” He observed that he had achieved more with his life in a year and a half in Iraq than he ever could have in Israel, even if he had remained in “the Zionist hell” for another twenty years.Footnote 123

Conclusion

While Jewish repatriation to the Arab world was episodic and numerically small, a common theme among the emigres is that they left due to discrimination and urged others to do the same. What is more, they seem to have had an effect; Israeli newspapers and government officials began to pay more attention to social inequalities. Repatriation deconstructs the master narrative that places the nation-state of Israel as the Westernized savior and sole homeland for the Jewish people and leaves open the question of the state's raison d’être as well as who has ownership over historiographical narrative of Afro-Asian Jewish history. In these cases, Israelis living outside its borders had more influence over the government than they would have while residing in it.

By looking at a migrant's history not as a culmination but as a process of negotiating one's identity, we engage with a more nuanced, complex understanding of migrant and Diasporic Jewish identity. Research into discrimination against Mizrahim and their responses to such practices restores a sense of agency for Mizrahi migrants and reveals their position as key mediators between Zionist and Arab nationalist claims concerning the nature of Diaspora and homeland for Jews. The stories of Moroccan and Iraqi Jews— struggling with the meaning of Diasporic belonging and torn between the realities of the contemporaneous and the memories of their former communal lives—asserted and made room for an alternative, liminal space. This alternative space, in which the State of Israel does not stand apart from but rather is part of the Jewish Diaspora, upends the binary paradigm of diaspora/homeland. It highlights the experience of transnational migration as a process involving the reality of belonging to two or more nation-states, thus requiring a reworking of concepts of the homeland. The repatriation of these individuals—from Israel to Iraq and back—encourages us to look toward the multiplicity of the meaning of Jewish belonging beyond the boundaries of the nation-state. These transgressive migrations, however small, threatened the raison d’être of the Jewish state: providing a homeland for the Jewish people tied to territorial nationalist claims. Out-migrants reworked and subverted the concept of yeridah by flipping its meaning to an emotional descent into Israel rather than away from it. Their migration out of Israel tells us just as much about the relationship of Israel to the Diaspora as an Aliyah does. It complicates the notion of the “negation of the Diaspora” and forces us to reimagine Israel as a transnational Jewish homeland that encompasses numerous Jewish Diasporas.