Introduction

On February 9, 2022, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) handed down its reparations judgment in the Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Uganda) case.Footnote 1 This followed from its December 19, 2005 merits judgment, which found that Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) had violated international law vis-à-vis each other and were obliged to make reparations to each other.Footnote 2 The ICJ ultimately held that, over five annual instalments of US$65 million from September 1, 2022 until September 1, 2026, Uganda was to pay the DRC a total of US$325 million for damage to persons, damage to property, and damage related to natural resources.Footnote 3

Background

The reparations judgment marked the culmination of protracted litigation that began on June 23, 1999, when the DRC filed suit against Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda seeking to hold them responsible for acts that had been carried out (and that continued to be carried out) by various armed forces on its territory.Footnote 4 On December 19, 2005, the merits judgment found that from August 1998 to June 2003, Uganda—with respect to the DRC—had violated the prohibition on the use of force and the principle of non-intervention; carried out killings, torture, and inhumane treatment against DRC civilians and destroyed their property; failed to distinguish between civilian and military targets and protect civilians; incited ethnic conflict; violated international human rights law and international humanitarian law as the occupying power in Ituri District of the DRC; looted, plundered, and exploited the DRC's natural resources; and failed to prevent such acts during its occupation.Footnote 5 The ICJ also found that the DRC had violated its obligations to Uganda by attacking the Ugandan Embassy in the DRC; mistreating Ugandan diplomats; failing to provide effective protection to Ugandan diplomats; and failing to prevent the seizure of archives and property from said Ugandan Embassy.Footnote 6 In accordance with the merits judgment, the parties were to seek agreement on reparations, failing which the matter would be settled by the ICJ.Footnote 7

The DRC and Uganda conducted reparations negotiations through to March 19, 2015, but could not agree on the applicable principles and modalities. As a result, on May 13, 2015, the DRC instituted ICJ proceedings and ultimately sought US$11,347,958,354 in compensation plus interest; by way of satisfaction, US$100 million for all non-material damage, US$25 million for the establishment of a reconciliation fund, and the criminal investigation/prosecution of culpable Ugandan soldiers; and costs.Footnote 8 Uganda submitted that the ICJ's findings on its responsibility for violating international law were appropriate satisfaction, thereby providing sufficient reparation; denied any other forms of reparation; and argued that each party should bear its own costs.Footnote 9 On October 12, 2020, the ICJ appointed four experts to provide it with an opinion on the heads of damage concerning the loss of human life, loss of natural resources, and damage to property.

The International Court of Justice's Reparations Judgment

The ICJ distinguished between the events that occurred in Ituri District and beyond Ituri District. With respect to Ituri District, it held that, as the occupying power at the time, Uganda had a duty of vigilance over events occurring therein, including those carried out by rebel groups. Because the merits judgment had found that Uganda failed to take measures to ensure respect for human rights and international humanitarian law in Ituri District, it fell on Uganda to demonstrate that the particular injury to the DRC that occurred therein was not caused by its failure to fulfil its occupation obligations. Absent such evidence, Uganda owed the DRC reparations for the injury.Footnote 10 The same was true with respect to the looting, plundering, and exploitation of Ituri District's natural resources.Footnote 11

For events beyond Ituri District, because the merits judgment had found that various rebel groups were not under Uganda's control and that Uganda did not breach any vigilance duty with respect to their conduct, reparations could not be awarded for the damage caused by these groups.Footnote 12 However, because Uganda had supported the Congo Liberation Movement (MLC) and the Congo Liberation Army (ALC) (which had operated beyond Ituri District), and the merits judgment had found that this violated international law, reparations could be owed, provided that the relevant injury to the DRC on a case-by-case basis was sufficiently causally linked to such support.Footnote 13 Importantly, in this context, the ICJ held that the requisite sufficiently direct and certain causal nexus between an internationally wrongful act and the injury suffered could vary depending on the international rule violated, and the nature and extent of the injury.Footnote 14 The ICJ stated that while some of the damage that occurred in the DRC beyond Ituri District resulted from a combination of acts and omissions of rebel groups and other states that had operated therein, this was insufficient to exempt Uganda from an obligation to make reparations.Footnote 15 In such situations, the obligation to make reparations could, depending on the circumstances, be allocated in full to a single actor or be distributed among multiple actors.Footnote 16

Although the ICJ recognized that the exact extent of the damage caused was subject to uncertainty, this did not bar it from determining a compensation amount; it could, exceptionally, award a global sum within the range of possibilities dictated by the evidence in light of equitable considerations.Footnote 17 The ICJ further determined that in cases involving large groups of victims of armed conflict, it was permissible to award a global sum for certain categories of injury even if it did not, in all probability, reflect the totality of the damage actually suffered.Footnote 18 Such cases also called for the adoption of less-rigorous standards of proof, with any compensation award being reduced to account for this lower standard of proof.Footnote 19 Thus, the DRC did not have to prove exact injury suffered by specific persons or precise property at particularized locations at an exact time; the ICJ could award compensation on the basis of its appreciation of the extent of the damage without this information.Footnote 20

The ICJ recalled that although it would normally fall on a claimant state to prove the injury it had suffered, this was not an absolute rule and would depend on the circumstances of the case.Footnote 21 Here, it fell upon Uganda to prove that the injury suffered by the DRC in Ituri District did not result from its failure to fulfill its occupying power obligations.Footnote 22 The DRC retained the burden to prove its injury on its territory beyond Ituri District, even if the armed conflict complicated the establishment of facts.Footnote 23 However, considering the passage of time and the amount of evidence that had been destroyed or was no longer accessible, the ICJ determined that the standard of proof in the reparations phase called for some flexibility.Footnote 24

The ICJ found that while the DRC's evidence could not establish the precise amount of compensation, it could consider investigative reports to assist in this endeavour, including those from United Nations organs and the court-appointed experts where relevant.Footnote 25 In view of the circumstances of the case and the passage of time, the ICJ determined that it would assess the existence and extent of the damage suffered by the DRC within a range of possibilities as per the evidence and based on reasonable estimates, taking into account whether factual findings were supported by more than one evidentiary source.Footnote 26 However, the injury claimed by the DRC had to fall within the scope of the categories of damage established in the merits judgment.Footnote 27

Based on these findings and the evidence on the record, the ICJ assessed the DRC's compensation claims. They were divided into four heads of damages, most with subcategories: (1) damage to persons; (2) damage to property; (3) damage related to natural resources; and (4) macroeconomic damage. While a complete outline of the ICJ's intricate (and long) analysis is beyond the scope of this introductory note, the DRC was successful, to various degrees, with respect to the first three categories, but unsuccessful in its macroeconomic damage claim and was therefore awarded a total of US$325 million, consisting of US$225 million for damage to persons, US$40 million for damage to property, and US$60 million for damage related to natural resources.Footnote 28 Uganda was found to have the capacity to pay this total amount, thereby rendering moot the need to assess the possible financial burden of the amount on, and the economic circumstances of, Uganda.Footnote 29

As for the DRC's satisfaction claims, the ICJ first noted that Uganda had existing obligations under the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949) and the First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions (1977) to investigate, prosecute, and punish violations of international humanitarian law and that, accordingly, there was no need to order the requested satisfaction since this was already encompassed by an existing international obligation.Footnote 30 Second, the claim for monies to create a fund to promote reconciliation between the Hema and Lendu groups in Ituri District was rejected because the material damage caused by the ethnic conflict was encompassed by the compensation awarded for damage to persons and property.Footnote 31 Finally, the DRC's monetary claim for non-material harm was rejected in light of international practice and because it was already included in the global sums awarded for the various heads of damage.Footnote 32

Further, the ICJ saw no reason to depart from the usual practice under Article 64 of the ICJ Statute whereby each party would bear its own costs (unless otherwise decided).Footnote 33 Additionally, the DRC's claim for pre-judgment interest was denied as the amounts it had awarded for the various heads of damage already took into account the passage of time.Footnote 34 But the ICJ determined that if Uganda was late on its payments, post-judgment interest would be payable at an accrued annual rate of 6 percent on any overdue amount.Footnote 35

Commentary

It is not often that violations of international law of the magnitude and scope of those in this case are brought for adjudication. It is also not always the case that, upon a judgment being delivered by an international court for the kind of conduct at issue here, the defendant state actually ends up paying reparations.Footnote 36 One might have expected such an outcome here given that, in the wake of the reparations judgment, Uganda issued a statement calling the judgment “unfair and wrong,” “deeply unclear,” and “an undue interference … in African affairs generally,” and opined that it did “not contribute to peace and security, or the spirit of cooperation between the two countries” or “inspire confidence in the Court as [a] fair and credible arbiter of international disputes.”Footnote 37 But on September 1, 2022, as widely reported, Uganda paid its first annual US$65 million instalment. It should be commended for abiding by the international rule of law.

In the not-too-distant past, the idea that massive monetary claims between states arising from armed conflict would be put by consent to a bench of international judges sitting at a permanent international court—where an uncertain outcome was guaranteed—might have seemed far-fetched or fanciful. As such, this case represents a further step toward the peaceful settlement of international disputes and shows than even the most complex of claims can be adjudicated if the political will exists. It also marks a big step in the ICJ's awarding of monetary reparations, which have been few and far between in its history; this case was the first time it had done so in the context of armed conflict and is by far the largest sum it has ever awarded. The sparse precedent in this area was evident from the ICJ's analysis of the applicable law, where it relied, in key parts, on the principles elucidated in the arbitration award issued by the Eritrea–Ethiopia Claims Commission—the only comparable modern example where reparations were awarded for similar violations of international law as those before the ICJ.

Notwithstanding, given the ICJ's authoritative character in international law, the reparations judgment will likely become the benchmark for how all future cases of this kind will be adjudged. In this respect, the way the ICJ arrived at the compensation figures it awarded when the precise damage inflicted and value of said damage was far from clear, together with its reliance on “global sums” for heads of damage rather than for each identified subcategory, can be criticized. Indeed, when compensation is awarded in this fashion, it is hard to scrutinize the result: the reader has no way to know how much the ICJ individually valued and apportioned, for example, loss of life, injuries to persons, and rape and sexual violence (all subcategories under the overall head of damage to persons). Exacerbating this is the fact that the ICJ did not articulate exactly how the monetary amounts for the global sums were determined. This is not to say that this is an easy task, but simply to note that litigants are entitled to reasons for judicial outcomes. One could question whether adequate reasons have been given when global sums are awarded for various heads of damage without a clear roadmap of how the sums were reached and without an itemized breakdown of their components. In these circumstances, the cynic might suggest that the precise chosen sums were plucked out of thin air, even if they did indeed fall within a range of identified “possibilities.” Regardless, it is notable that the final compensation figure awarded represented only approximately 3 percent of what the DRC had originally claimed in this category.

Similarly, the ICJ's detailed elucidation of various principles on the law of evidence and standard of proof will reverberate far beyond the present case. But perhaps even more importantly, the ICJ appears to have loosened the casual nexus requirement: whereas before it had been understood that a sufficiently direct and certain causal link between a claimed injury and a violation of international law was necessary for the awarding of reparations, now the ICJ has said that this can vary, effectively depending on the case being brought. No doubt most, if not all, subsequent claimants in ICJ reparations cases will seek to test this by arguing that their facts merit a deviation away from the “traditional” understanding of the causal nexus. Time will tell whether such a loosening will only be reserved for cases concerning armed conflict.

9 FÉVRIER 2022

ARRÊT

ACTIVITÉS ARMÉES SUR LE TERRITOIRE DU CONGO (RÉPUBLIQUE DÉMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO c. OUGANDA)

ARMED ACTIVITIES ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CONGO (DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO v. UGANDA)

9 FEBRUARY 2022

JUDGMENT

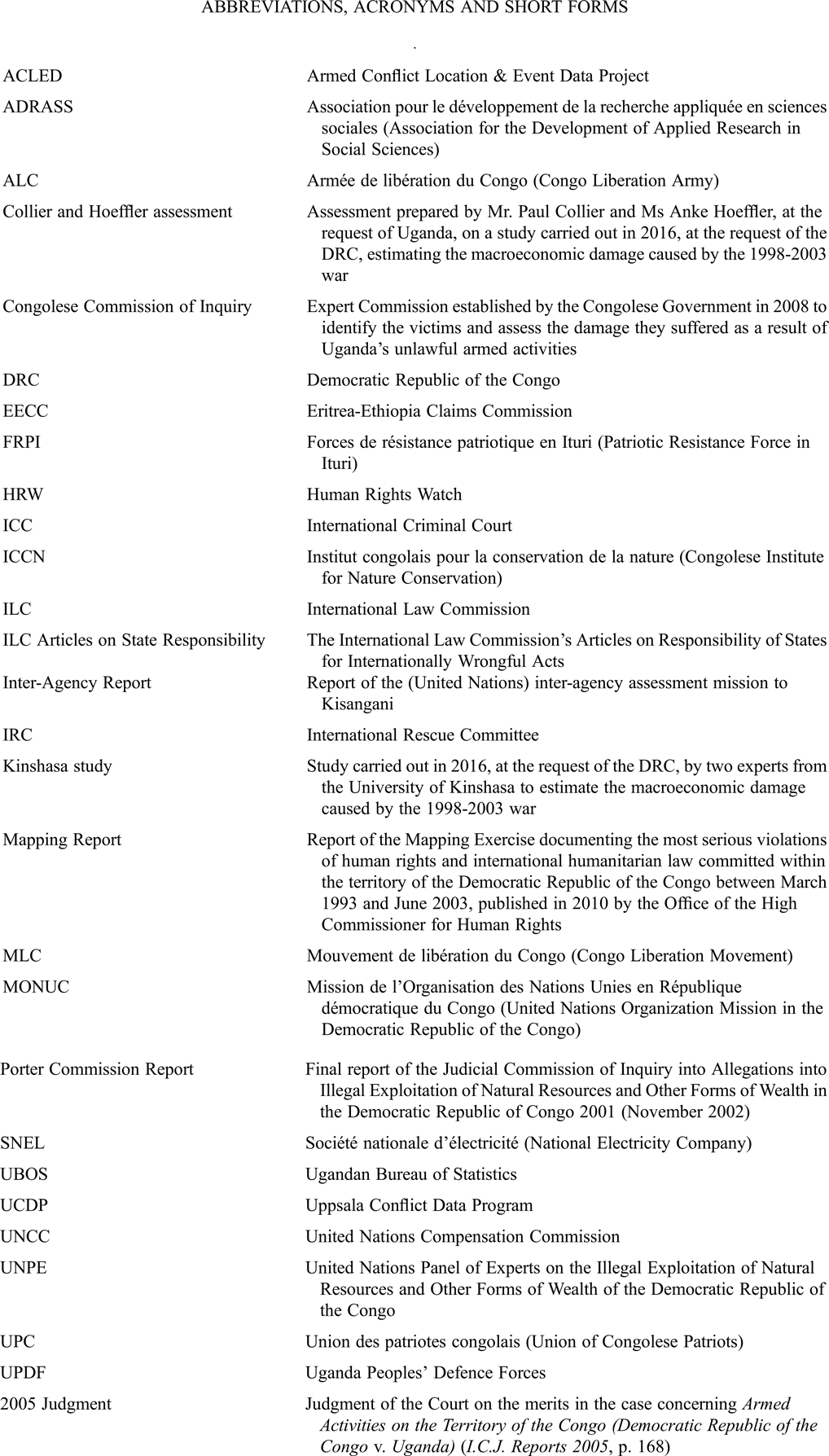

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Paragraphs

CHRONOLOGY OF THE PROCEDURE....................[1-47]

I. INTRODUCTION....................[48-59]

II. GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS....................[60-131]

A. Context....................[61-68]

B. The principles and rules applicable to the assessment of reparations in the present case....................[69-110]

1. The principles and rules applicable to the different situations that arose during the conflict....................[73-84]

(a) In Ituri....................[74-79]

(b) Outside Ituri....................[80-84]

2. The causal nexus between the internationally wrongful acts and the injury suffered....................[85-98]

3. The nature, form and amount of reparation....................[99-110]

C. Questions of proof....................[111-126]

1. The burden of proof....................[115-119]

2. The standard of proof and degree of certainty....................[120-126]

D. The forms of damage subject to reparation....................[127-131]

III. COMPENSATION CLAIMED BY THE DRC....................[132-384]

A. Damage to persons....................[133-226]

1. Loss of life....................[135-166]

2. Injuries to persons....................[167-181]

3. Rape and sexual violence....................[182-193]

4. Recruitment and deployment of child soldiers....................[194-206]

5. Displacement of populations....................[207-225]

6. Conclusion....................[226]

B. Damage to property....................[227-258]

1. General aspects....................[240-242]

2. Ituri....................[243-249]

3. Outside Ituri....................[250-253]

4. Société nationale d’électricité (SNEL)....................[254-255]

5. Military property....................[256]

6. Conclusion....................[257-258]

C. Damage related to natural resources....................[259-366]

1. General aspects....................[273-281]

2. Minerals....................[282-327]

(a) Gold....................[282-298]

(b) Diamonds....................[299-310]

(c) Coltan....................[311-322]

(d) Tin and tungsten....................[323-327]

3. Flora....................[328-350]

(a) Coffee....................[328-332]

(b) Timber....................[333-344]

(c) Environmental damage resulting from deforestation....................[345-350]

4. Fauna....................[351-363]

5. Conclusion....................[364-366]

D. Macroeconomic damage....................[367-384]

IV. SATISFACTION....................[385-392]

V. OTHER REQUESTS....................[393-404]

A. Costs....................[394-396]

B. Pre-judgment and post-judgment interest....................[397-402]

C. Request that the Court remain seised of the case....................[403-404]

VI. TOTAL SUM AWARDED....................[405-408]

OPERATIVE CLAUSE....................[409]

YEAR 2022

2022

9 February General List No. 116

9 February 2022

ARMED ACTIVITIES ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CONGO (DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO v. UGANDA)

REPARATIONS

Determination of the amount of reparation by the Court following failure by the Parties to settle this question by agreement — 2005 Judgment and elements on which it was based.

*

Context.

Case concerning one of the most complex and deadliest armed conflicts on the African continent — Numerous actors involved in conflict, including armed forces of various States and irregular forces — Violation of fundamental principles and rules of international law — Difficulty of establishing the course of events due to the passage of time.

* *

Principles and rules applicable to the assessment of reparations.

Article 31 of the ILC Articles on State Responsibility — Status of Ituri as an occupied territory and duty of vigilance of Uganda — For Uganda to establish that a particular injury in Ituri was not caused by failure to meet its obligations as an occupying Power — No reparation for damage caused by rebel groups outside Ituri since they were not under Uganda's control — Reparation for damage caused by Uganda's unlawful support of armed groups.

*

Causal nexus.

Must be sufficiently direct and certain — May vary depending on the primary rule violated and nature and extent of the injury — Difficulties of establishing causal nexus in case of damage resulting from war and in case of concurrent causes or multiple actors — Importance of distinguishing between Ituri and other areas when analysing causal nexus.

*

Nature, form and amount of reparation.

Obligation to make full reparation — Compensatory nature of reparation — Intended to benefit all those who suffered injury — Absence of adequate evidence of extent of material damage does not necessarily preclude award of compensation — Court may, on an exceptional basis, award compensation in the form of a global sum where the evidence leaves no doubt that an internationally wrongful act has caused a substantial injury, but does not allow a precise evaluation of the extent or scale of such injury — Less rigorous standards of proof adopted by judicial or other bodies in proceedings with large numbers of victims who have suffered serious injury in situations of armed conflict and, in this context, levels of compensation reduced in order to account for lower standard of proof — Question whether account should be taken of financial burden imposed on responsible State.

*

Questions of proof.

Court may form an appreciation of extent of damage without specific information about each victim or property affected.

Burden of proof — Party alleging a fact generally bears burden of proof — Rule must be applied flexibly in situations where respondent may be in better position to establish certain facts — Burden of proof varies depending on subject-matter and nature of dispute — It is for the Court to evaluate all evidence produced by the Parties — In occupied Ituri, it is for Uganda to establish that a given injury was not caused by its failure to meet its obligations as occupying Power — In other areas, litigant seeking to establish a fact generally bears burden of proof.

Standard of proof — May vary from case to case and may depend on gravity of acts alleged — Question of weight to be given to different kinds of evidence — Practice of international bodies that have addressed reparation for mass violations in context of armed conflict — Standard of proof at merits phase higher than at phase on reparation — Evidence in case file often insufficient to reach precise determination of amount of compensation due — Court must take account of investigative reports, in particular those from United Nations organs — Porter Commission Report — Mapping Report — Reports by Court-appointed experts.

*

Forms of damage subject to reparation.

2005 Judgment determined Uganda's obligation to repair — Court's task at present stage is to rule on nature and amount of reparation owed — Claims for reparation must fall within scope of prior findings on liability.

* *

Compensation claimed be the DRC.

Damage to persons.

Loss of life — On the basis of evidence reviewed, Court's conclusion that neither the materials presented by the DRC, nor the reports provided by the Court-appointed experts or prepared by United Nations bodies are sufficient to determine a precise or even approximate number of civilian deaths for which Uganda owes reparation — Evidence presented to Court suggests number of deaths attributable to Uganda falls in range of 10,000 to 15,000 persons — Valuation — Court will award compensation for loss of civilian lives as part of global sum for all damage to persons.

Injuries to persons — On the basis of evidence, Court is unable to determine an approximate estimate of number of civilians injured — Available evidence confirms occurrence of significant number of injuries in many localities — Valuation — Court will award compensation for personal injuries as part of global sum for all damage to persons.

Rape and sexual violence — Sexual violence is frequently underreported and difficult to document — Impossible to derive even broad estimate of number of victims from the available evidence — Rape and other forms of sexual violence committed on large and widespread scale — Valuation — Court will award compensation for rape and sexual violence as part of global sum for all damage to persons.

Recruitment and deployment of child soldiers — Limited evidence supporting DRC's claims regarding number of child soldiers — Various indications confirm that a significant number of children were recruited or deployed as child soldiers in Ituri — Claim not limited to Ituri — Valuation — Court will award compensation for recruitment and deployment of child soldiers as part of global sum for all damage to persons.

Displacement of populations — Evidence presented does not establish a sufficiently certain number of displaced persons for whom compensation could be awarded separately —Uganda owes reparations in relation to significant number of displaced persons — Displacements in Ituri alone appear to have been in range of 100,000 to 500,000 persons — Valuation — Court will award compensation for displacement of persons as part of global sum for all damage to persons.

Global sum of US$225,000,000 awarded for loss of life and other damage to persons.

*

Damage to property.

Ituri — Evidence presented does not permit even to approximate extent of damage — Report of Court-appointed expert does not provide any relevant additional information — Mapping Report and other United Nations reports establish convincing record of large-scale pillaging in Ituri — Valuation.

Outside Ituri — Insufficient evidence regarding which damage to property was caused by Uganda — Evidence presented does not permit even to approximate extent of damage — Report of Court-appointed expert does not provide any relevant additional information — Valuation — Account taken of available evidence in arriving at global sum for all damage to property.

Société nationale d’électricité (SNEL) — Given Government's close relationship with SNEL, DRC could have been expected to provide evidence substantiating its claim — DRC has not discharged its burden of proof regarding claim for damage to SNEL.

Military property — Given direct authority of Government over its armed forces, DRC can be expected to substantiate its claims more fully — Claim dismissed for lack of evidence.

Global sum of US$40,000,000 awarded for damage to property.

*

Damage related to natural resources.

Outside Ituri, Uganda owes reparation for damage related to natural resources where UPDF involved — In Ituri, Uganda owes reparation for all acts of looting, plundering or exploitation of natural resources — Methodological approach of Court-appointed expert is convincing — Value extracted by civilians from natural resources in Ituri.

Minerals — Uganda responsible for damage resulting from looting, plundering and exploitation of gold, diamonds and coltan — Methodological approach taken by the Court-appointed expert is convincing overall — Court to award compensation for gold, diamonds and coltan as part of global sum for damage to natural resources — Given limited evidence relating to tin and tungsten, these two minerals not taken into account in determining compensation.

Flora — Inclusion of coffee in expert report permissible — Uganda owes reparation for looting, plundering and exploitation of timber — Expert calculations based on rougher estimates than with gold — Amount of compensation at level lower than expert's estimate — Court to award compensation for coffee and timber as part of global sum for damage to natural resources — DRC did not provide Court any basis for assessing damage to environment through deforestation — Claim for damage resulting from deforestation dismissed for lack of evidence.

Fauna — Uganda liable to make reparation for damage in part of Okapi Wildlife Reserve and Virunga National Park in Ituri, where it was occupying Power — Court to take damage to fauna into account when awarding global sum for damage to natural resources.

Global sum of US$60,000,000 awarded for damage to natural resources.

*

Macroeconomic damage.

DRC has not demonstrated sufficiently direct and certain causal nexus between the conduct of Uganda and alleged macroeconomic damage — DRC has not provided a basis for arriving at even rough estimate of possible macroeconomic damage — Claim rejected.

* *

Satisfaction.

Request relating to conduct of criminal investigations or prosecutions — No need for the Court to order any additional specific measure of satisfaction — Request to order payment for creation of fund to promote reconciliation between Hema and Lendu in Ituri — Material damage caused by ethnic conflicts in Ituri already covered by compensation awarded for damage to persons and property — Request to order payment for non-material harm — No basis for such request as non-material harm is already included in the claims for compensation for different forms of damage.

* *

Other requests.

No sufficient reason that would justify departing from the general rule in Article 64 of the Statute — No need to award pre-judgment interest — Post-judgment interest of 6 per cent will accrue on any overdue amount — No reason for the Court to remain seised of the case.

* *

Total sum of US$325,000,000 awarded — Sum to be paid in five annual instalments of US$65,000,000 — Court satisfied that total sum and terms of payment remain within capacity of Uganda to pay; therefore no need to consider the question whether account should be taken of financial burden imposed on responsible State.

JUDGMENT

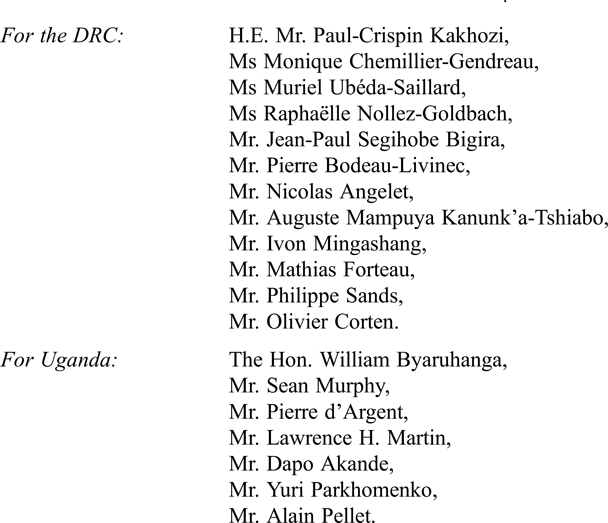

Present: President Donoghue; Vice-President Gevorgian; Judges Tomka, Abraham, Bennouna, Yusuf, Xue, Sebutinde, Bhandari, Robinson, Salam, Iwasawa, Nolte; Judge ad hoc Daudet; Registrar Gautier.

In the case concerning armed activities on the territory of the Congo,

between

the Democratic Republic of the Congo,

represented by

H.E. Mr. Bernard Takaishe Ngumbi, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Justice, Keeper of the Seals a.i.,

as Head of Delegation;

H.E. Mr. Paul-Crispin Kakhozi, Ambassador of the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the Kingdom of Belgium, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and the European Union,

as Agent;

Mr. Ivon Mingashang, member of the Brussels and Kinshasa/Gombe Bars, Professor and Head of the Department of Public International Law and International Relations at the Faculty of Law, University of Kinshasa,

as Co-Agent and Legal Counsel;

Ms Monique Chemillier-Gendreau, Emeritus Professor of Public Law and Political Science at the University Paris Diderot,

Mr. Mathias Forteau, Professor of Public Law at the University Paris Nanterre,

Mr. Pierre Bodeau-Livinec, Professor of Public Law at the University Paris Nanterre,

Ms Muriel Ubéda-Saillard, Professor of Public Law at the University of Lille,

Ms Raphaëlle Nollez-Goldbach, Director of Studies in Law and Public Administration at the Ecole normale supérieure, Paris, in charge of research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS),

Mr. Pierre Klein, Professor of International Law at the Université libre de Bruxelles,

Mr. Nicolas Angelet, member of the Brussels Bar and Professor of International Law at the Université libre de Bruxelles,

Mr. Olivier Corten, Professor of International Law at the Université libre de Bruxelles,

Mr. Auguste Mampuya Kanunk'a-Tshiabo, Emeritus Professor of International Law at the University of Kinshasa,

Mr. Jean-Paul Segihobe Bigira, Professor of International Law at the University of Kinshasa and member of the Kinshasa/Gombe Bar,

Mr. Philippe Sands, QC, Professor of International Law, University College London, Barrister, Matrix Chambers, London,

Ms Michelle Butler, Barrister, Matrix Chambers, London,

as Counsel and Advocates;

Mr. Jacques Mbokani Bateghana, Doctor of Law of the Université catholique de Louvain and Professor of International Law at the University of Goma,

Mr. Paul Clark, Barrister, Garden Court Chambers, London,

as Counsel;

Mr. François Habiyaremye Muhashy Kayagwe, Professor at the University of Goma,

Mr. Justin Okana Nsiawi Lebun, Professor of Economics at the University of Kinshasa,

Mr. Pierre Ebbe Monga, Legal Counsel at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Democratic Republic of the Congo,

Ms Nicole Ntumba Bwatshia, Professor of International Law at the University of Kinshasa and Principal Adviser to the President of the Republic in Legal and Administrative Matters,

Mr. Andrew Maclay, Managing Director, Secretariat International, London,

as Advisers;

Mr. Sylvain Lumu Mbaya, PhD student in international law at the University of Bordeaux and the University of Kinshasa, and member of the Kinshasa/Matete Bar (Eureka Law Firm SCPA),

Mr. Jean-Paul Mwanza Kambongo, Lecturer at the University of Kinshasa and member of the Kinshasa/Gombe Bar (Eureka Law Firm SCPA),

Mr. Jean-Jacques Tshiamala wa Tshiamala, member of the Kongo Central Bar (Eureka Law Firm SCPA) and Lecturer in International Law at the Centre de recherche en sciences humaines in Kinshasa,

Ms Blandine Merveille Mingashang, member of the Kinshasa/Matete Bar (Eureka Law Firm SCPA) and Lecturer in International Law at the Centre de recherche en sciences humaines in Kinshasa,

Mr. Glodie Kinsemi Malambu, member of the Kongo Central Bar and Lecturer in International Law at the Centre de recherche en sciences humaines in Kinshasa,

Ms Espérance Mujinga Mutombo, member of the Kinshasa/Matete Bar (Eureka Law Firm SCPA) and Lecturer in International Law at the Centre de recherche en sciences humaines in Kinshasa,

Mr. Trésor Lungungu Kidimba, PhD student in international law and Lecturer at the University of Kinshasa, member of the Kinshasa/Gombe Bar,

Mr. Amani Cirimwami Ezéchiel, Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute Luxembourg for Procedural Law and PhD student at the Université catholique de Louvain and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel,

Mr. Stefano D'Aloia, PhD student at the Université libre de Bruxelles,

Ms Marta Duch Gimenéz, Lecturer at the Université catholique de Louvain,

as Assistants,

and

the Republic of Uganda,

represented by

The Hon. William Byaruhanga, SC, Attorney General of the Republic of Uganda, as Agent (until 4 February 2022);

The Hon. Kiryowa Kiwanuka, Attorney General of the Republic of Uganda, as Agent (from 4 February 2022);

H.E. Ms Mirjam Blaak Sow, Ambassador of the Republic of Uganda to the Kingdom of Belgium, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and the European Union,

as Deputy Agent;

Mr. Francis Atoke, Solicitor General,

Mr. Christopher Gashirabake, Deputy Solicitor General,

Ms Christine Kaahwa, acting Director Civil Litigation,

Mr. John Bosco Rujagaata Suuza, Commissioner Contracts and Negotiations,

Mr. Jeffrey Ian Atwine, Principal State Attorney,

Mr. Richard Adrole, Principal State Attorney,

Mr. Fadhil Mawanda, Principal State Attorney,

Mr. Geoffrey Wangolo Madete, Senior State Attorney,

Mr. Alex Byaruhanga, Senior State Attorney,

as Counsel;

Mr. Dapo Akande, Professor of Public International Law, University of Oxford, Essex Court Chambers, member of the Bar of England and Wales,

Mr. Pierre d'Argent, Professor of International Law at the Université catholique de Louvain, member of the Institut de droit international, Foley Hoag LLP, member of the Brussels Bar,

Mr. Lawrence H. Martin, Attorney at Law, Foley Hoag LLP, member of the Bars of the United States Supreme Court, the District of Columbia and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

Mr. Sean Murphy, Manatt/Ahn Professor of International Law, The George Washington University Law School, member of the Bar of Virginia,

Mr. Yuri Parkhomenko, Attorney at Law, Foley Hoag LLP, member of the Bar of the District of Columbia,

Mr. Alain Pellet, Emeritus Professor of the University Paris Nanterre, former Chairman of the International Law Commission, member of the Institut de droit international,

as Counsel and Advocates;

Ms Rebecca Gerome, Attorney at Law, Foley Hoag LLP, member of the Bars of the District of Columbia and New York,

Mr. Peter Tzeng, Attorney at Law, Foley Hoag LLP, member of the Bars of the District of Columbia and New York,

Mr. Benjamin Salas Kantor, Attorney at Law, Foley Hoag LLP, member of the Bar of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Chile,

Mr. Ysam Soualhi, Researcher, Centre Jean Bodin, University of Angers,

as Counsel;

H.E. Mr. Arthur Sewankambo Kafeero, acting Director, Regional and International Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

Col. Timothy Nabaasa Kanyogonya, Director of Legal Affairs, Chieftaincy of Military Intelligence — Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces, Ministry of Defence, as Advisers,

THE COURT,

composed as above,

after deliberation,

delivers the following Judgment:

1. On 23 June 1999, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (hereinafter the “DRC”) filed in the Registry of the Court an Application instituting proceedings against the Republic of Uganda (hereinafter “Uganda”) in respect of a dispute concerning “acts of armed aggression perpetrated by Uganda on the territory of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in flagrant violation of the United Nations Charter and of the Charter of the Organization of African Unity” (emphasis in the original). In order to found the jurisdiction of the Court, the Application relied on the declarations made by the two Parties accepting the Court's compulsory jurisdiction under Article 36, paragraph 2, of the Statute of the Court.

2. Since the Court included upon the Bench no judge of the nationality of the Parties at the time of the filing of the Application, each Party availed itself of its right under Article 31 of the Statute to choose a judge ad hoc to sit in the case. The DRC first chose Mr. Joe Verhoeven, who resigned on 15 May 2019, and then Mr. Yves Daudet. Uganda chose Mr. James L. Kateka. Following the election to the Court, with effect from 6 February 2012, of Ms Julia Sebutinde, a Ugandan national, Mr. Kateka ceased to sit as judge ad hoc in the case, in accordance with Article 35, paragraph 6, of the Rules of Court.

3. By an Order of 21 October 1999, the Court fixed 21 July 2000 and 21 April 2001, respectively, as the time-limits for the filing of the Memorial of the DRC and the Counter-Memorial of Uganda. Those pleadings were filed within the time-limits thus prescribed.

4. Uganda's Counter-Memorial included counter-claims. By an Order of 29 November 2001, the Court found that two of the three counter-claims submitted by Uganda were admissible as such and formed part of the proceedings on the merits. By the same Order, the Court directed the submission of a Reply by the DRC and a Rejoinder by Uganda. By an Order of 29 January 2003, it authorized the submission of an additional pleading by the DRC relating solely to the counter-claims. Those pleadings were filed within the time-limits fixed by the Court.

5. Public hearings were held on the merits of the case from 11 to 29 April 2005.

6. In its Judgment dated 19 December 2005 (hereinafter the “2005 Judgment”), the Court found, inter alia, with respect to the claims brought by the DRC, that

“the Republic of Uganda, by engaging in military activities against the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the latter's territory, by occupying Ituri and by actively extending military, logistic, economic and financial support to irregular forces having operated on the territory of the DRC, violated the principle of non-use of force in international relations and the principle of non-intervention” (Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Uganda), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2005, p. 280, para. 345, subpara. (1) of the operative part);

“the Republic of Uganda, by the conduct of its armed forces, which committed acts of killing, torture and other forms of inhumane treatment of the Congolese civilian population, destroyed villages and civilian buildings, failed to distinguish between civilian and military targets and to protect the civilian population in fighting with other combatants, trained child soldiers, incited ethnic conflict and failed to take measures to put an end to such conflict; as well as by its failure, as an occupying Power, to take measures to respect and ensure respect for human rights and international humanitarian law in Ituri district, violated its obligations under international human rights law and international humanitarian law” (ibid., p. 280, para. 345, subpara. (3) of the operative part); and

“the Republic of Uganda, by acts of looting, plundering and exploitation of Congolese natural resources committed by members of the Ugandan armed forces in the territory of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and by its failure to comply with its obligations as an occupying Power in Ituri district to prevent acts of looting, plundering and exploitation of Congolese natural resources, violated obligations owed to the Democratic Republic of the Congo under international law” (ibid., pp. 280-281, para. 345, subpara. (4) of the operative part).

With respect to these violations, the Court found that Uganda was under an obligation to make reparation to the DRC for the injury caused (ibid., p. 281, para. 345, subpara. (5) of the operative part).

7. In relation to the counter-claims presented by Uganda, the Court found that

“the Democratic Republic of the Congo, by the conduct of its armed forces, which attacked the Ugandan Embassy in Kinshasa, maltreated Ugandan diplomats and other individuals on the Embassy premises, maltreated Ugandan diplomats at Ndjili International Airport, as well as by its failure to provide the Ugandan Embassy and Ugandan diplomats with effective protection and by its failure to prevent archives and Ugandan property from being seized from the premises of the Ugandan Embassy, violated obligations owed to the Republic of Uganda under the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961” (2005 Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2005, p. 282, para. 345, subpara. (12) of the operative part).

With respect to these violations, the Court found that the DRC was under an obligation to make reparation to Uganda for the injury caused (ibid., p. 282, para. 345, subpara. (13) of the operative part).

8. The Court further decided in its 2005 Judgment that, failing agreement between the Parties, the question of reparations due would be settled by the Court (ibid., pp. 281-282, para. 345, subparas. (6) and (14) of the operative part).

9. By letters dated 26 January and 3 July 2009, the Registrar asked the Parties to provide information concerning any negotiations they might be holding for the purpose of settling the question of reparations. Information was received from the DRC by a letter dated 6 July 2009 and from Uganda by a letter dated 18 July 2009. In particular, Uganda referred to an agreement concluded by the Parties at Ngurdoto (Tanzania) on 8 September 2007, which established a framework for an amicable settlement of the question of reparations.

10. Between 2009 and 2015, the Parties continued to keep the Court informed about the status of their negotiations. They held various meetings, including four at the ministerial level. At the end of the fourth and final ministerial meeting, held in Pretoria, South Africa, from 17 to 19 March 2015, the Parties acknowledged that they had been unable to agree on the principles and modalities to be applied in order to determine the amount of reparation due. Given the lack of consensus at the ministerial level, the matter was referred to the Heads of State for further guidance, within the framework of the Ngurdoto Agreement.

11. On 13 May 2015, the DRC submitted to the Court a document dated 8 May 2015 and entitled “New Application to the International Court of Justice”, in which its Government stated in particular that

“the negotiations on the question of reparation owed to the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Uganda must now be deemed to have failed, as is made clear in the joint communiqué signed by both Parties in Pretoria, South Africa, on 19 March 2015; it therefore behoves the Court, as provided for in paragraph 345 (6) of the Judgment of 19 December 2005, to reopen the proceedings that it suspended in the case, in order to determine the amount of reparation owed by Uganda to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the basis of the evidence already transmitted to Uganda and which will be made available to the Court”.

12. At a meeting held by the President of the Court with the representatives of the Parties on 9 June 2015, pursuant to Article 31 of the Rules, the Co-Agent of the DRC, after outlining the history of the negotiations held by the Parties with a view to reaching an amicable settlement on the question of reparations, stated that his Government was of the view that the said negotiations had failed and that it was because of that failure that the DRC had decided to seise the Court again. At the same meeting, the Agent of Uganda indicated that his Government was of the view that the conditions for referring the question of reparations to the Court had not been met and that the request made by the DRC in the Application filed on 13 May 2015 was therefore premature.

13. During the meeting of 9 June 2015, the President ascertained the views of the Parties on how much time they would need for the preparation of the written pleadings on the question of reparations, should the Court decide to authorize such pleadings. The Co-Agent of the DRC stated that a time-limit of three and a half to four months would be sufficient for his Government to prepare its Memorial. The Agent of Uganda, citing the highly complex nature of the questions to be decided, mentioned a time-limit of 18 months from the filing of the DRC's Memorial for the preparation of a Counter-Memorial by his Government.

14. By an Order of 1 July 2015, the Court decided to resume the proceedings in the case with respect to the question of reparations. It fixed 6 January 2016 as the time-limit for the filing of a Memorial by the DRC on the reparations which it considers to be owed to it by Uganda, and for the filing of a Memorial by Uganda on the reparations which it considers to be owed to it by the DRC.

15. By an Order of 10 December 2015, the President of the Court, at the request of the DRC, extended to 28 April 2016 the time-limit for the filing of the Parties’ Memorials on the question of reparations. Following an additional request from the DRC, by an Order of 11 April 2016, the Court extended that time-limit to 28 September 2016. The Memorials were filed within the time-limit thus extended.

16. By an Order of 6 December 2016, the Court fixed 6 February 2018 as the time-limit for the filing, by each Party, of a Counter-Memorial responding to the claims presented by the other Party in its Memorial. The Counter-Memorials of the Parties were filed within the time-limit thus fixed.

17. By letters dated 11 June 2018, the Registrar informed the Parties that, pursuant to Article 62, paragraph 1, of its Rules, the Court wished to obtain further information on certain issues it had identified. A list of questions was attached to the Registrar's letter and the Parties were asked to provide their responses to those questions by 11 September 2018 at the latest. The Parties were further informed that they would then each have until 11 October 2018 to communicate any comments they might wish to make on the responses of the other Party. Those time-limits were subsequently extended at the request of the Parties. Both Parties filed their responses on 1 November 2018. The DRC, however, transmitted reorganized versions of its responses on 12 and 20 November 2018, in view of certain problems with the annexes that had been submitted. By a letter dated 24 November 2018, the DRC indicated that the document filed on 20 November 2018 constituted the “final version” of its responses. The DRC then submitted comments on Uganda's responses on 4 January 2019, and Uganda submitted comments on the DRC's responses on 7 January 2019.

18. By letters dated 4 September 2018, the Parties were informed that the hearings on the question of reparations would take place from 18 to 22 March 2019. By a letter dated 11 February 2019, the DRC asked the Court to postpone the hearings by some six months. By a letter dated 12 February 2019, Uganda indicated that it neither opposed nor consented to the DRC's request, and that it was content to commit the matter to the Court's judgment. By letters dated 27 February 2019, the Parties were notified that the Court had decided to postpone the opening of the hearings to 18 November 2019.

19. By a joint letter dated 9 November 2019 and filed in the Registry on 12 November 2019, the Parties requested that the hearings due to open on 18 November 2019 be postponed for a period of four months “in order to afford [their] countries a further opportunity to attempt to amicably settle the question of reparations by bilateral agreement”. By letters dated 12 November 2019, the Parties were informed that the Court had decided to postpone the opening of the oral proceedings and that it would determine, at the appropriate time, new dates for the hearings, taking into account the Parties’ request and its own schedule of work for 2020.

20. By letters dated 9 January 2020, the Registrar indicated to the Parties that the Court would appreciate receiving information from either or both of them on the status of their negotiations. The Court subsequently received several communications from the Parties providing such information. Having regard to those communications and taking into account the fact that the four-month period of negotiations requested by the Parties had lapsed, the Parties were informed, by letters dated 23 April 2020, that the Court intended to hold hearings in the case during the first trimester of 2021.

21. By letters dated 8 July 2020, the Registrar informed the Parties that, while continuing to examine the full range of heads of damage claimed by the Applicant and the defences invoked by the Respondent, the Court considered it necessary to arrange for an expert opinion, pursuant to Article 67, paragraph 1, of its Rules, with respect to the following three heads of damage for the period between 6 August 1998 and 2 June 2003: loss of human life, loss of natural resources and property damage. The Parties were also informed that the Court had fixed 29 July 2020 as the time-limit within which they could present, in accordance with Article 67, paragraph 1, of the Rules of Court, their respective positions regarding any such appointment, in particular their views on the subject of the expert opinion, the number and mode of appointment of the experts and the procedure to be followed. By the same letter, the Registrar indicated that any comments that either Party might wish to make on the response of the other Party should be communicated by 12 August 2020 at the latest.

22. By a letter dated 15 July 2020, Uganda observed that “the questions before the Court are not of the sort contemplated” under Article 50 of the Statute of the Court and Article 67, paragraph 1, of the Rules relating to the appointment of experts. Therefore, it

“strongly object[ed] to the proposal to appoint an expert or experts for the stated purpose because it amounts to relieving the DRC of the primary responsibility to prove her claim (or any particular heads of claim), and assigning that responsibility to third parties, to the prejudice of Uganda and in violation of the relevant principles of international law”.

23. By a letter dated 24 July 2020, the DRC stated that it was “favourably disposed towards the Court's proposal that, for the three heads of damage referred to [in the Registrar's letter of 8 July 2020], there should be recourse to an expert opinion”. It added that recourse to an expert opinion was “without prejudice to the judicial role of the Court” and that it was “ultimately for the Court, and not the experts, to decide on the compensation owed by Uganda to the Democratic Republic of the Congo”. The DRC also transmitted its views on the mode of appointment of the experts and expressed the opinion that the procedure to be followed should correspond to the established practice of the Court.

24. By a letter dated 12 August 2020, Uganda provided its comments on the views expressed by the DRC regarding the expert opinion envisaged by the Court in the case, reiterating its objections to the appointment of experts. It stated that “there is no evidence for the experts to assess or opine on. What remains is for the Court to make the determination as to whether the evidence submitted by the DRC meets the required standard based on its own assessment of the evidence vis-à-vis the applicable principles of international law”.

25. By an Order dated 8 September 2020, having duly taken into account the views of the Parties, the Court decided to arrange for an expert opinion, pursuant to Article 67 of its Rules, regarding certain heads of damage alleged by the Applicant, namely, loss of human life, loss of natural resources and property damage. The Order set out the following terms of reference for the experts:

“I. Loss of human life

(a) Based on the evidence available in the case file and documents publicly available, particularly the United Nations Reports mentioned in the 2005 Judgment, what is the global estimate of the lives lost among the civilian population (broken down by manner of death) due to the armed conflict on the territory of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the relevant period?

(b) What was, according to the prevailing practice in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in terms of loss of human life during the period in question, the scale of compensation due for the loss of individual human life?

II. Loss of natural resources

(a) Based on the evidence available in the case file and documents publicly available, particularly the United Nations Reports mentioned in the 2005 Judgment, what is the approximate quantity of natural resources, such as gold, diamond, coltan and timber, unlawfully exploited during the occupation by Ugandan armed forces of the district of Ituri in the relevant period?

(b) Based on the answer to the question above, what is the valuation of the damage suffered by the Democratic Republic of the Congo for the unlawful exploitation of natural resources, such as gold, diamond, coltan and timber, during the occupation by Ugandan armed forces of the district of Ituri?

(c) Based on the evidence available in the case file and documents publicly available, particularly the United Nations Reports mentioned in the 2005 Judgment, what is the approximate quantity of natural resources, such as gold, diamond, coltan and timber, plundered and exploited by Ugandan armed forces in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, except for the district of Ituri, and what is the valuation of those resources?

III. Property damage

(a) Based on the evidence available in the case file and documents publicly available, particularly the United Nations Reports mentioned in the 2005 Judgment, what is the approximate number and type of properties damaged or destroyed by Ugandan armed forces in the relevant period in the district of Ituri and in June 2000 in.Kisangani?

(b) What is the approximate cost of rebuilding the kind of schools, hospitals and private dwellings destroyed in the district of Ituri and in Kisangani?”

26. By the same Order, the Court decided that the expert opinion would be “entrusted to four independent experts appointed by Order of the Court after hearing the Parties”. It was also noted that, before taking up their duties, the experts would make the following declaration:

“I solemnly declare, upon my honour and conscience, that I will perform my duties as expert honourably and faithfully, impartially and conscientiously, and will refrain from divulging or using, outside the Court, any documents or information of a confidential character which may come to my knowledge in the course of the performance of my task.”

27. By letters dated 10 September 2020, the Registrar informed the Parties of the Court's decision and of the fact that the Court had identified four potential experts to carry out the expert mission, namely, in alphabetical order, Ms Debarati Guha-Sapir, Mr. Michael Nest, Mr. Geoffrey Senogles and Mr. Henrik Urdal, whose curricula vitae were appended to those letters. The Registrar invited the Parties to communicate to the Court any observations they might wish to make on the choice of experts by 18 September 2020 at the latest.

28. By a letter dated 17 September 2020, the DRC indicated that it had no objection to the four experts proposed by the Court.

29. By a letter dated 18 September 2020, Uganda asked the Court, inter alia, to extend the time-limit for its observations on the potential experts identified by the Court. The President of the Court decided to extend that time-limit to 25 September 2020.

30. By a letter dated 25 September 2020, Uganda presented its observations on the experts proposed by the Court, stating that it objected to the selection of three of them on various grounds.

31. By an Order dated 12 October 2020, having duly considered the views of the Parties, the Court decided to appoint the following four experts:

– Ms Debarati Guha-Sapir, of Belgian nationality, Professor of Public Health at the University of Louvain (Belgium), Director of the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, Brussels (Belgium), member of the Belgian Royal Academy of Medicine;

– Mr. Michael Nest, of Australian nationality, Environmental Governance Advisor for the European Union's Accountability, Rule of Law and Anti-corruption Programme in Ghana and former conflict minerals analyst for United States Agency for International Development and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit projects in the Great Lakes Region of Africa;

– Mr. Geoffrey Senogles, of British nationality, Partner at Senogles & Co, Chartered Accountants, Nyon (Switzerland); and

– Mr. Henrik Urdal, of Norwegian nationality, Research Professor and Director of the Peace Research Institute Oslo (Norway).

The experts subsequently made the solemn declaration provided for in the Order of 8 September 2020 (see paragraph 26 above).

32. By letters dated 1 December 2020, the Parties were informed that the Court had fixed 22 February 2021 as the date for the opening of the hearings on the question of reparations.

33. By letters dated 21 December 2020, the Registrar communicated to the Parties copies of the report filed by the experts appointed in the case. Each Party was given until 21 January 2021 to submit any written observations it might wish to make on that report.

34. By letters dated 24 December 2020, the Registrar transmitted to the Parties corrigenda received from the Court-appointed experts to their report.

35. By a letter dated 23 December 2020, Uganda requested that the hearings due to open on 22 February 2021 be postponed to “after 17 March 2021”. By a letter dated 7 January 2021, the DRC indicated that its Government had no objection to the postponement. Taking into account the above-mentioned request and the views expressed by the DRC on this question, the Court decided to postpone to 20 April 2021 the opening of the hearings in the case.

36. By a letter dated 13 January 2021, Uganda requested that the time-limit for the submission to the Court of any observations the Parties might wish to make on the experts’ report, originally fixed for 21 January 2021, be extended to 14 February 2021. By a letter dated 17 January 2021, the DRC indicated that it “c[ould] see no justification for extending the time-limit for the submission by each Party of its written observations on the experts’ report”. By letters dated 18 January 2021, the Registrar informed the Parties that, in view of the fact that, with the agreement of the Parties, the hearings had been postponed to April 2021, the President of the Court had decided to extend to 15 February 2021 the time-limit for the submission, by the Parties, of their observations on the said report.

37. Under cover of a letter dated 14 February 2021, the Co-Agent of the DRC communicated to the Court his Government's written observations on the experts’ report. Uganda furnished its written observations on the said report on 15 February 2021. Each Party's observations were communicated to the experts, who responded to them in writing on 1 March 2021; their response was immediately transmitted to the Parties. The latter were asked to indicate to the Registry, by 15 March 2021 at the latest, whether they wished to put questions to the experts at the hearings.

38. By a letter dated 6 March 2021, the Co-Agent of the DRC indicated that his Government wished to put questions to the experts at the hearings.

39. By a letter dated 16 March 2021, the Agent of Uganda stated that his Government reserved the right to put questions to the experts at the hearings. By a letter dated 6 April 2021, he indicated that his Government wished to put questions to the experts during the hearings.

40. Pursuant to Article 53, paragraph 2, of its Rules, the Court, after ascertaining the views of the Parties, decided that copies of the written pleadings on reparations and the documents annexed thereto, the responses of the Parties to the questions put by the Court and the comments on those responses would be made accessible to the public on the opening of the oral proceedings. It subsequently decided to make the experts’ report and related documents accessible to the public.

41. Public hearings on the question of reparations were held from 20 to 30 April 2021. The oral proceedings were conducted in a hybrid format, in accordance with Article 59, paragraph 2, of the Rules of Court and on the basis of the Court's Guidelines for the Parties on the Organization of Hearings by Video Link, adopted on 13 July 2020 and communicated to the Parties on 23 December 2020. Prior to the opening of the hybrid hearings, the Parties were invited to participate in comprehensive technical tests. During the oral proceedings, a number of judges were present in the Great Hall of Justice, while others joined the proceedings via video link, allowing them to view and hear the speaker and see any demonstrative exhibits displayed. Each Party was permitted to have up to four representatives present in the Great Hall of Justice at any one time and was offered the use of an additional room in the Peace Palace from which members of the delegation were able to participate via video link. Members of the delegations were also given the opportunity to participate via video link from other locations of their choice.

42. During the above-mentioned hearings, the Court heard the oral arguments and replies of:

43. The experts appointed in the case (see paragraph 31 above) were heard at two public hearings, in accordance with Article 65 of the Rules of Court. Questions were put by counsel of the Parties to each of the experts. Members of the Court put questions to Mr. Urdal and Ms Guha-Sapir.

44. At the hearings, a Member of the Court put a question to the Parties, to which replies were given orally, in accordance with Article 61, paragraph 4, of the Rules of Court.

*

45. In the written proceedings on the question of reparations, the following submissions were presented by the Parties:

On behalf of the Government of the DRC,

in the Memorial:

“For the reasons set out above, and subject to any changes made to its claims in the course of the proceedings, the Democratic Republic of the Congo requests the Court to adjudge and declare that:

(a) Uganda is required to pay the DRC the sum of US$13,478,122,950 (thirteen billion four hundred and seventy-eight million one hundred and twenty-two thousand nine hundred and fifty United States dollars) in compensation for the damage resulting from the violations of international law found by the Court in its Judgment of 19 December 2005;

(b) compensatory interest will be due on that amount at a rate of 6 per cent, payable from the date on which the present Memorial was filed;

(c) Uganda is required to pay the DRC the sum of US$125 million by way of giving satisfaction for all non-material damage resulting from the violations of international law found by the Court in its Judgment of 19 December 2005;

(d) Uganda is required, by way of giving satisfaction, to conduct criminal investigations and prosecutions of the officers and soldiers of the UPDF involved in the violations of international humanitarian law or international human rights norms committed in Congolese territory between 1998 and 2003;

(e) in the event of non-payment of the compensation awarded by the Court on the date of the judgment, moratory interest will accrue on the principal sum at a rate to be determined by the Court;

(f) Uganda is required to reimburse the DRC for all the costs incurred by the latter in the context of the present case.”

in the Counter-Memorial:

“For the reasons set out above, the Democratic Republic of the Congo requests the Court, without any prejudicial recognition by the Democratic Republic of the Congo of the legal principles set out in the Memorial of Uganda, to adjudge and declare that:

(a) the Court's finding of the DRC's international responsibility in its Judgment of 19 December 2005 constitutes an appropriate form of reparation for the injury arising from the following wrongful acts as found in that same Judgment: (a) the maltreatment by Congolese forces of individuals on Uganda's diplomatic premises and of Ugandan diplomats at Ndjili International Airport; (b) the invasion, seizure and long-term occupation of the official residence of the Ambassador of Uganda in Kinshasa; and (c) the seizure of public and personal property from Uganda's diplomatic premises in Kinshasa;

(b) Uganda is entitled to payment of a sum of US$982,797.73 by the DRC, an amount not contested by the DRC in the context of the proceedings before the Court, in compensation for the injury resulting from the invasion, seizure and long-term occupation of Uganda's Chancery compound in Kinshasa;

(c) the compensation thus awarded to Uganda will be offset against that awarded to the DRC on the basis of its principal claims in the present case.”

On behalf of the Government of Uganda,

in the Memorial:

“On the basis of the facts and law set forth in this Memorial, Uganda respectfully requests the Court to adjudge and declare that:

(1) With respect to the loss, damage or injury arising from (a) the maltreatment of persons by Congolese forces on Uganda's diplomatic premises and of Ugandan diplomats at Ndjili Airport; (b) the invasion, seizure and long-term occupation of the residence of the Ambassador of Uganda in Kinshasa; and (c) the seizure of public and personal property from Uganda's diplomatic premises in Kinshasa, the Court's formal findings of the DRC's international responsibility in the 2005 Judgment constitute an appropriate form of satisfaction, providing reparation for the injury suffered.

(2) With respect to the loss, damage or injury arising from the invasion, seizure and long-term occupation of Uganda's Chancery compound in Kinshasa, the DRC is obligated to make monetary compensation to the Republic of Uganda in the total amount of US$982,797.73.”

in the Counter-Memorial:

“On the basis of the facts and law set forth in this Counter-Memorial, Uganda respectfully requests the Court to adjudge and declare that:

(1) the Court's formal findings of Uganda's international responsibility in the 2005 Judgment constitute an appropriate form of satisfaction, providing reparation for the injury suffered;

(2) all other reparation sought by the DRC is denied; and

(3) each Party shall bear its own costs of these proceedings.”

46. At the oral proceedings, the following submissions were presented by the Parties:

On behalf of the Government of the DRC,

“For the reasons set out in its written pleadings and oral arguments, the Democratic Republic of the Congo requests the Court to adjudge and declare that:

(1) With regard to the claims of the Democratic Republic of the Congo:

(a) Uganda is required to pay the Democratic Republic of the Congo in compensation for the damage resulting from the violations of international law found by the Court in its Judgment of 19 December 2005:

– no less than four billion three hundred and fifty million four hundred and twenty-one thousand eight hundred United States dollars (US$4,350,421,800) for personal injury;

– no less than two hundred and thirty-nine million nine hundred and seventy-one thousand nine hundred and seventy United States dollars (US$239,971,970) for damage to property;

– no less than one billion forty-three million five hundred and sixty-three thousand eight hundred and nine United States dollars (US$1,043,563,809) for damage to natural resources;

– no less than five billion seven hundred and fourteen million seven hundred and seventy-five United States dollars (US$5,714,000,775) for macroeconomic damage.

(b) compensatory interest will be due on heads of claim other than those for which the amount of compensation awarded by the Court, based on an overall assessment, already takes account of the passage of time, at a rate of 4 per cent, payable from the date of the filing of the Memorial on reparation;

(c) Uganda is required, by way of giving satisfaction, to pay the Democratic Republic of the Congo the sum of US$25 million for the creation of a fund to promote reconciliation between the Hema and Lendu in Ituri, and the sum of US$100 million for the non-material harm suffered by the Congolese State as a result of the violations of international law found by the Court in its Judgment of 19 December 2005;

(d) Uganda is required, by way of giving satisfaction, to conduct criminal investigations and prosecutions of the individuals involved in the violations of international humanitarian law or international human rights norms committed in Congolese territory between 1998 and 2003 for which Uganda has been found responsible;

(e) in the event of non-payment of the compensation awarded by the Court on the date of the judgment, moratory interest will accrue on the principal sum at a rate of 6 per cent;

(f) Uganda is required to reimburse the Democratic Republic of the Congo for all the costs incurred by the latter in the context of the present case.

(2) With regard to Uganda's counter-claim, and without any prejudicial recognition by the Democratic Republic of the Congo of the legal principles set out in the Memorial of Uganda:

(a) the Court's finding of the Democratic Republic of the Congo's international responsibility in its Judgment of 19 December 2005 constitutes an appropriate form of reparation for the injury arising from the wrongful acts as found in the same Judgment;

(b) Uganda is otherwise entitled to payment of the sum of US$982,797.73 (nine hundred and eighty-two thousand seven hundred and ninety-seven United States dollars and seventy-three cents) by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, an amount not contested by the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the context of the proceedings before the Court, in compensation for the injury resulting from the invasion, seizure and long-term occupation of Uganda's Chancery compound in Kinshasa;

(c) the compensation thus awarded to Uganda will be offset against that awarded to the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the basis of its principal claims in the present case.

(3) The Court is further requested to declare that the present dispute will not be fully and finally resolved until Uganda has actually paid the reparations and compensation ordered by the Court. Until that time, the Court will remain seised of the present case.”

On behalf of the Government of Uganda,

“The Republic of Uganda respectfully requests that the Court:

(1) Adjudge and declare that:

(a) The DRC is entitled to reparation in the form of compensation only to the extent it has discharged the burden the Court placed on it in paragraph 260 of the 2005 Judgment ‘to demonstrate and prove the exact injury that was suffered as a result of specific actions of Uganda constituting internationally wrongful acts for which it is responsible’;

(b) The Court's finding of Uganda's international responsibility in the 2005 Judgment otherwise constitutes an appropriate form of satisfaction; and

(c) Each Party shall bear its own costs of these proceedings; and

(2) Reject all other submissions of the DRC.”

*

47. At the end of the hearings, the Agent of Uganda informed the Court that his Government “officially waive[d] its counter-claim for reparation for the injury caused by the conduct of the DRC's armed forces, including attacks on the Ugandan diplomatic premises in Kinshasa and the maltreatment of Ugandan diplomats”.

*

* *

I. INTRODUCTION

48. In view of the failure by the Parties to settle the question of reparations by agreement, it now falls to the Court to determine the nature and amount of reparations to be awarded to the DRC for injury caused by Uganda's violations of its international obligations, pursuant to the findings of the Court set out in the 2005 Judgment. The Court begins by recalling certain elements on which it based that Judgment.

49. In its 2005 Judgment, the Court first pointed to the “complex and tragic situation which ha[d] long prevailed in the Great Lakes region” and also noted that there had been “much suffering by the local population and destabilization of much of the region”. The Court explained, however, that its task was “to respond, on the basis of international law, to the particular legal dispute brought before it” and that, “[a]s it interpret[ed] and applie[d] the law, it w[ould] be mindful of context, but its task [could] not go beyond that” (I.C.J. Reports 2005, p. 190, para. 26).

50. The Court found, in that Judgment, that Uganda had violated several obligations incumbent on it under international law and that it was therefore under an obligation to make reparation to the DRC for the injury caused (see paragraph 6 above). The Court will recall here only the basic facts and conclusions that led it to hold Uganda internationally responsible. The Court will recall the context and other relevant facts of the case in more detail when setting out certain general considerations with respect to the question of reparations (Part II, Section A, paragraphs 61-68 below) and when addressing the DRC's claims for various forms of damage (Parts III and IV, paragraphs 132-392 below).

51. In its 2005 Judgment, the Court found that, from mid-1997 to the first half of 1998, Uganda was allowed by the Government of the DRC to engage in military action against anti-Ugandan rebels in the eastern part of Congolese territory. However, the Court concluded that any consent by the DRC to the presence of Ugandan troops on its territory had been withdrawn by 8 August 1998 at the latest. From August 1998 until June 2003, Uganda conducted unlawful military operations in the east of the DRC, as well as in other parts of the country. In so doing, it took control of several locations in the provinces of North Kivu, Orientale and Equateur (I.C.J. Reports 2005, pp. 206-207, paras. 78-81). The Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces (hereinafter the “UPDF”) conducted military operations in a large number of locations (ibid., p. 224, para. 153), including in Kisangani, where it engaged in large-scale fighting against Rwandan forces, particularly in August 1999 and in May and June 2000 (ibid., p. 207, para. 80). From August 1998 until June 2003, the forces of other States were also present on the DRC's territory, as were irregular forces, some of which were supported by Uganda.

52. The Court concluded that Uganda was an “occupying Power”, within the meaning of the term as understood in the jus in bello, in Ituri district at the relevant time (ibid., p. 231, para. 178). It found that Uganda's responsibility was thus engaged both for any acts of its military that violated its international obligations and for any lack of vigilance in preventing violations of human rights and international humanitarian law by other actors present in the occupied territory, including rebel groups acting on their own account (ibid., p. 231, para. 179). The Court also found that Uganda was internationally responsible for acts of looting, plundering and exploitation of the DRC's natural resources committed by members of the UPDF in the territory of the DRC, including in Ituri, and for failing to comply with its obligations as an occupying Power in Ituri in respect of all acts of looting, plundering and exploitation of natural resources in the occupied territory (ibid., p. 231, para. 250).

53. The Court further concluded that Uganda,

“by engaging in military activities against the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the latter's territory, by occupying Ituri and by actively extending military, logistic, economic and financial support to irregular forces having operated on the territory of the DRC, violated the principle of non-use of force in international relations and the principle of non-intervention” (ibid., p. 280, para. 345, subpara. (1) of the operative part).

54. The Court found that “massive human rights violations and grave breaches of international humanitarian law were committed by the UPDF on the territory of the DRC” during the conflict (ibid., p. 239, para. 207). The Court further found that the UPDF had failed to protect the civilian population and to distinguish between combatants and non-combatants in the course of fighting against other troops (ibid., p. 240, para. 208). It considered that there was persuasive evidence that, in Ituri district, the UPDF had incited ethnic conflicts and taken no action to prevent such conflicts (ibid., p. 240, para. 209). Moreover, the Court found that there was convincing evidence that child soldiers had been trained in UPDF training camps and that the UPDF had failed to prevent the recruitment of child soldiers in areas under its control (ibid., p. 241, para. 210).

55. The Court concluded on the basis of these findings that Uganda,