Introduction

This article explores two important elements of the health policy-making environment in Northern Europe in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. The first part of the paper considers the impact of a continued lack of growth in the broader national economy in constraining new public revenues. This shortage of new funding has become the central challenge that policymakers in these health systems now confront, and increasingly constrains their potential range of policy options.

The next sections of the article examine the types of reform strategies that these health systems have implemented in response to the intensified fiscal stringency they face, as well as increasing demands for service from chronically ill elderly. In tax-funded health systems, these reforms have focused, first, on re-structuring public sector administrative arrangements for health providers, particularly public hospitals, and, second, on both streamlining the delivery of, and reducing the volume of demands for, health system services from elderly patients. Through these combined structural efforts, these health systems have sought to respond to the constrained post-2008 fiscal environment with multiple efforts to improve the cost efficiency of public service management and delivery.

The article concludes with several parallels to recent and current decision-making strategies in several of the Canadian provinces.

Part I: The European health sector’s political economy problem

The onset of the 2008 financial crisis signaled a fundamental shift in the economic foundation of European health care systems. Since the 1960s, long-term economic growth, interrupted by the occasional recession, had provided new sources of private sector earnings that could be taxed to provide increased public sector services. Even the longer slowdown that accompanied oil price hikes of 1973 and 1978 gave way to rapid growth in the 1980s and 1990s.

The economic growth problems triggered by the 2008 crisis, however, have proved to be on a different scale. Only in 2017, 9 years later, is there now serious discussion about the beginnings of economic recovery across Europe (Jones, Reference Jones2017; Sylvers, Reference Sylvers2017). Recent numbers about economic growth in Europe, while a bit better in the first quarter of 2017 (Donnan et al., Reference Donnan, Tetlow and Fleming2017), demonstrate the extent to which many European countries still have not returned to the 3% per year level that in the post-World War II period was seen as normal economic growth. Indeed, only in the third quarter of 2013 did the United Kingdom recover to the point of producing the same economic output produced in 2006, while Italy and Portugal still have not returned to their pre-crisis gross domestic product (GDP) levels (Romei, Reference Romei2017). Also, France has yet to reach its 2008 GDP production level (Ip, Reference Ip2017). The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) economic forecast for Europe released on 7 March 2017 emphasized the need for a ‘durable exit from the low-growth trap’ (Giles, Reference Giles2017).

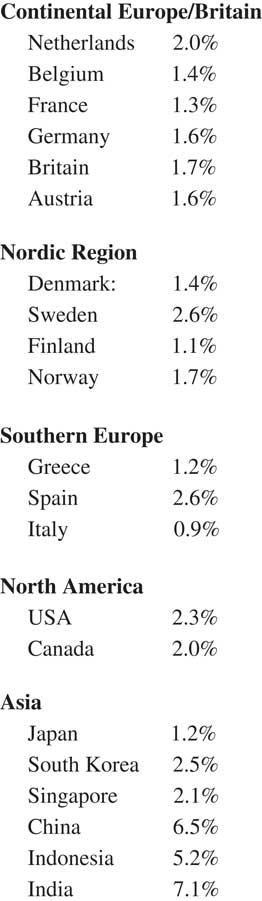

The most recent GDP projections for 2017 (Figure 1) show that even the best performing European countries – such as Germany at 1.6% – remain below the 2% per year economic growth rate that economists consider the bare minimum for a sustainable economic expansion. Most of the rest of the continent will continue to experience 1–2% as the best level of growth it can sustain. Soberingly, UK growth in the first quarter of 2017 was only 0.2% at an annual rate (Jackson, Reference Jackson2017), suggesting recent government projections for the United Kingdom, expecting GDP growth of 1.6% in 2018 and 2019 (Nixon, Reference Nixon2017), may be substantially overstated. Moreover, this continued slow growth is occurring despite ongoing large monetary stimulus from the Bank of England and the European Central Bank, which still maintain artificially low interest rates as well as buying government bonds to add liquidity into the money supply.

Figure 1 Growth in gross domestic product, projected annual rate for 2017. Source: The Economist/Haver Analytics, 29 April 2017; US government/Financial Times/Bank of Finland.

Several credible economic explanations have been offered to explain what has been termed this ‘new normal’ in Western economies (PIMCO, 2009). While none are uncontested, taken together these analyses paint a larger picture of continued slow growth for the foreseeable future which will have major implications for the availability of continued public resources for health systems in Europe (Saltman and Cahn, Reference Saltman, Dubois and Chawla2013).

One key explanation for the persistent growth slowdown in European economies has been the size of the national debt. These numbers varied in early May 2017 from 70% of GDP in Germany to 82% in the United Kingdom, 97% in France and 110% in Belgium to well over 100% of GDP in all Mediterranean European countries. Moreover, these debt levels continue to grow as nearly all EU countries continue to run substantial annual budget deficits (OECD, 2017). Reinhart and Rogoff (Reference Reinhart and Rogoff2010, Reference Reinhart and Rogoff2011), two former International Monetary Fund economists now at Harvard University, have contended in a hotly contested but never controverted analysis that when public national debt levels breach 90%, they crowd out private economic development and dampen overall economic growth.

In addition to the 2008 fiscal crisis, large national debt figures also reflect two further negative economic indicators. One is the low level of productivity growth in most Western industrial economies. As one sentinel example, this critical figure is only 0.6% annually now in the United States, having fallen dramatically since 2000 (Kravis, Reference Kravis2017). A second negative factor for GDP growth has been continued large national welfare state programs. While welfare state proponents point toward the equity benefits of these services (Karanikolos et al., 2013), critics highlight the consequences that paying for these programs have for both high tax levels and the accumulation of additional public debt (Alesina and Giavazzi, Reference Alesina and Giavazzi2008; Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2012).

Overall, there is a strong economic case to conclude that the post-2008 growth problem in developed and especially European countries reflects a deep-seated structural problem (King, Reference King2010, Reference King2013; Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2012) that has become semi-permanent in character. The clear consequence is that ‘easy’ new public revenues for European health systems– e.g., derived from piggybacking on general economic growth – are unlikely for the foreseeable future. The alternative source of public revenue – raising already high income, capital, property and value-added taxes – would be economically self-defeating in that such measures would further reduce already low economic growth rates, thus exacerbating the strain on total public revenues created by the post-2008 economic slowdown.

Turning to the impact of slow economic growth on specifically health care, many ‘wealthy’ European countries have found themselves unable to raise sufficient new taxable income to fund continuing needs for new services (precision medicine), new technologies (clinical and informational), newly developed pharmaceuticals (particularly biologics) and newly capitalized provider institutions (especially hospitals). While this shortage of funds is not a new problem, especially in tax-funded health systems like the National Health Service (NHS) in England, it has increased to critical levels and spread more widely now across much of western and central Europe.

As one example of this funding problem, in England at the end of April 2017, the British Pharmaceutical Association (BPA) warned that England’s largest pharmaceutical companies may be forced to leave England entirely, if the NHS does not find adequate new revenues to allow patients to gain access to drugs developed in their British research laboratories (Smyth, Reference Smyth2017). Both the BPA and a respected independent economist, John Appleby of Nuffield Trust, argued that the NHS needed immediately an additional 20 billion pounds per year – that is, a 20% increase in government funding – in order to be able to purchase currently available drugs indicated for proper treatment of their patient population (Smyth, Reference Smyth2017). In a separate, subsequent analysis, Appleby and another Nuffield Trust economist concluded in May 2017 that, regardless of likely reforms and promised increases, adequate additional funding for the NHS will almost certainly not be available through to the end of the next Parliament (Gainsbury and Appleby, Reference Gainsbury and Appleby2017).

This difficulty in funding necessary care at the constantly rising international standard (De Roo, Reference De Roo1995) will be compounded by costs for a new European military buildup to counter expanding Russian military capabilities. Sweden, for example, announced in March 2017 that it would re-introduce military conscription and raise its military expenditures by an additional 6.5 billion Swedish crowns (about $700 million) to a total of 51.5 billion Swedish crowns this year (about $5.5 billion) (Milne, Reference Milne2017).

Beyond constraints on new public revenues, European, like most developed health systems, face increased pressure from a substantial number of quarters:

∙ Demographic (aging, migration)

∙ Technological (digitalization; new pharmaceuticals)

∙ Patient expectations (quality; responsiveness; choice)

∙ Workforce (recruiting; higher wages; burnout)

∙ Capital investment (renovations; capital equipment; information technology)

In brief, the existing structure of European health sector finance and organization has become and is likely to remain seriously strained going forward.

Part II: Patterns in post-2008 European health reforms

The academic literature on the present institutional dilemma in Western developed health systems is rather narrowly framed. The initial response in most countries to the 2008 financial crisis was short-term and superficial (Mladovsky et al., 2012), premised on the assumption that, if expenditures were protected by ring-fencing, the problem would likely go away on its own – e.g., that growth would return to national economies and that increases in health sector revenues would resume. When funding cuts were introduced, these often occurred 2–3 years after the revenue fall-off began, and they triggered only minor increases in alternative private revenues (the three Baltic states were an exception). The plurality of state-led responses concentrated on reductions in peripheral programs rather than tackling more major cost and/or service drivers such as fixed infrastructure.

Reflecting this aversion to institutional change, academic papers dealing with the health policy consequences of the 2008 downturn tend to offer only a compendium of complaints about the unfairness of the downturn, and to emphasize how negative the health sector consequences have been (McKee and Stuckler, 2011; de Belvisa et al., 2012). Those studies that did consider organizational realities have tended to underplay the scale of core structural problems (Pavolini and Guillen, Reference Pavolini and Guillen2013; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Figueras, Evetovits, Jowett, Mladovsky, Cylus, Karanikolos and Kluge2015).

Despite this academic downplaying of the problem, there have been a number of important if narrowly framed reforms to health care institutions across Europe which reflect the effects of the 2008 financial crisis, and/or efforts undertaken just before the crisis’s onset, in seeking to reduce systemic problems of financial and organizational sustainability (Saltman et al., Reference Saltman and Cahn2011; Kuhlmann et al., Reference Kuhlmann, Blank, Bourgeault and Wendt2015). These recent strategic reforms can be characterized in terms of their impact on three core dimensions of health systems generally: (a) funding (how the funds are raised); (b) allocation (how the raised funds are distributed to providers, whether by budget, by contract, by case or service); and (c) provision (how providers are structured and operated) (Saltman, Reference Saltman, Duran and DuBois1994).

There have been substantially different patterns in how tax-funded systems across Europe (essentially Northern European and Southern European) have focused their post-2008 institutional reforms in comparison with how Social Health Insurance (SHI)-funded systems (essentially Continental systems in Western and Central Europe) have responded. The most striking difference is in those parts of the health system where there has been little or no change – that is, no major new strategies or initiatives. In tax-funded systems, there has been no significant change in the specific funding arrangements for publicly provided health care, although the number of private insurance policies that provide private health services have grown considerably since 2008 in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. By contrast, in SHI systems, it has been the institutional and organizational arrangements for the production of health services that have been largely unchanged, with some exceptions concerning long-term care services (see the Netherlands case study below) and pilot projects for chronically ill elderly.

Similarly, the significant organizational and institutional changes that have been made in these health systems have also been quite different. In tax-funded systems, major changes in re-configuring service provider organizations on the production side have been introduced in long-term care services (Norway, Denmark), as well as a major re-structuring of the entire service delivery system now underway in Finland (Saltman and Teperi, Reference Saltman, Bankauskaite and Vrangbaek2016). There also have been important pilot projects on decentralization (England) and long-term care alternatives (Sweden). Conversely, in SHI systems, most major structural health system changes have focused on the funding side, on how health care revenue is raised and channeled.

It is of note that, despite the structural divergence just detailed, both types of systems have made important changes to the intermediate category of ‘allocation models’, e.g., the arrangements and incentives by which the money raised (here called ‘funding’) is transferred to the service providers (here called ‘production’). One key allocation element that grew substantially in tax-funded health systems was the number and size of private contractors, extending from specific types of elective surgery to a wide range of social care services including nursing home and other elderly residence-based care. Although this New Public Management strategy (Hood, 1991) was not ‘new’ to Northern European tax-funded health systems, the scope and volume in several countries (Sweden, England) grew substantially during this period.

Similarly, in SHI systems, these allocation model changes focused on a shift from the previous, collective and retrospective model of allocation among its separate sickness funds [e.g. German risk adjustment models before 2009 (Busse, Reference Busse2004)], to – as in the Netherlands post-2006 – new individually based, prospective models of risk adjustment that set a price on each insuree’s head which would pass to their selected insurance fund, including a special bonus for those suffering from one of 80 ‘listed conditions’ (Kroneman et al., Reference Kroneman, Boerma, van den Berg, Groenewegen, de Jong and van Ginnekin2016). Germany also adopted a similar type of central pooling plus individual risk adjustment system in 2009 which, although planned just before the crisis, had to be increased in 2011 – following the crisis – to provide more money. This funding increase was accomplished by an historic shift in the traditional 50–50% allocation of premiums between employer and employee to an arrangement in which the employee had to pay a higher percentage than the employer (rising to 8.2% for the employee, while the employer’s share held firm at the 2005 rate of 7.3%) (Busse and Blumel, Reference Busse and Blumel2014).

These distinctions trace a revealing pattern across the post-2008 health sector landscape in Europe – one that undercuts the recurring propensity of some health policy analysts to suggest that differences between tax and SHI-funded systems are disappearing due to convergence (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Foubisher and Mossialos2009; Greer et al., Reference Greer, Wismar and Figueras2015). In actual practice, these two different types of health care systems are working on quite different assumptions about needed changes to normative, financial, political, regulatory and managerial forms of responsibility. There also appears to be notable differences in the overall performance of these different systems. As one important example, SHI-funded health systems have few (the Netherlands) to no (Germany, France, Switzerland) queues of patients waiting to receive primary or elective services. Tax-funded health systems in Northern Europe – even those with formal ‘care guarantees’ (Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland) and official patient management policies (England, Ireland) – continue, quite the contrary, to have waiting lists often running 6 months or longer for some procedures including cancer therapies (see, e.g. Neville, Reference Neville2017, regarding England), queues which nearly all these systems have had for most of the last 30 years (see Yates, Reference Yates1987 regarding England).

Part III: Innovative post-2008 reform strategies in tax-funded health systems

As the slow economic growth picture has become the ‘new normal’, in combination with population and organizational changes just noted, policymakers in a number of Western European countries have shifted gears and introduced a range of targeted new reform measures. While this process took on different characteristics in tax-funded as against SHI-funded health systems, in both cases the focus of a number of these measures was on reducing existing and expected costs for future infrastructure and particularly for expensive facilities (hospital inpatient and emergency facilities; nursing homes) utilized for caring for chronically ill elderly.

A number of innovative and, potentially, transferrable organizational changes have been introduced on the delivery side of European tax-funded health systems, with ancillary changes in how funding is allocated to producers. Among the interesting (mostly national level) policy strategies adopted by tax-funded systems have been the following:

∙ Consolidating hospitals: district into regional [Norway; Denmark; Finland (proposed); Latvia]

∙ Re-Centralizing administrative/budget controls over health care to national level of government [Norway; Denmark; Veneto/Italy; Finland (proposed)]

∙ De-centralizing administrative/budget controls to municipal level of government (Norway; Denmark)

∙ Fusing health and social (elderly home and residential (LTC)) care within a single public administration [Finland (proposed); England – Greater Manchester; Sheffield]

∙ Shifting chronically ill elderly from nursing homes to home care (the Netherlands)

∙ Creating ‘municipal acute bed units’ (MAUs)/step-down beds (Norway; Denmark)

∙ Embedding ‘municipal primary care units’ inside regional hospitals (Norway; Denmark)

Additionally, there are a growing number of pilot projects and reform trials that as yet have not been disseminated nationally. These include:

∙ Fusing health and social (LTC) care inside a single public administration (‘TioHundra’ project, Norrtalje, Stockholm County, Sweden)

∙ Re-unifying regional health and social budgets: dropping Diagnostic-Related Groups (DRG) case-based payment systems (Central Region, Jutland, Denmark)

There have also been a few organizational changes in tax-funded health care systems that have occurred on the funding side of these systems. These funding side changes are noteworthy for their peripheral (Nordic) or failed (Ireland) character:

∙ Increased private supplemental insurance (Finland; Denmark; Sweden)

∙ New mandatory social insurance (Ireland – canceled)

∙ Increased out-of-pocket payments (Latvia – 37% of total expenditures)

By introducing this range of closely focused reforms, policymakers have sought to reduce the post-2008 fiscal pressure on their health systems by streamlining both service delivery and administrative structures. To the extent that they are successful, these types of reforms can improve access and outcomes, particularly for the chronically ill patients that are both increasing rapidly in number and are adding additional strain to existing staff and facilities. In many cases, these reforms also enable elderly patients to be treated closer to home and in less intensive settings, both of which typically are their preference.

Each of the country case studies below highlight one or more key dimensions of these new reform strategies. These cases concentrate on specific structural mechanisms for analytic but also policy-making reasons, seeking to illustrate the mix of innovative approaches that individual countries are adopting. As noted above, little formal evaluation of these mechanisms – or of the specific mix of mechanisms employed in individual national contexts – has yet been completed, limiting conclusions about long-term financial and care quality outcomes from these measures. However, discussion of the observed patterns and relevant evaluation criteria among these cases follows in Part V below.

Norway

In 2012, the Norwegian government introduced major structural reforms in the public production of health care services for the chronically ill elderly. These focused on expanding access to intermediate ‘step-down’ services in communities and establishing new hospital-based discharge coordination units, as well as requiring municipalities to reimburse hospitals for several types of chronic-care-related services (Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Saltman and Vrangbaek2015). These reforms reflected growing financial pressure in Norway on health sector services, including lengthening queues, following the onset of the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent fall in the price of Norway’s main export, North Sea oil.

These 2012 reforms were an extension of strong national government intervention in the health sector which had begun in 2002 with the structural reform of public providers. The 2002 reforms had merged Norway’s 19 (elected) county councils into five (then four) unelected regional administrative bodies appointed from Oslo, with the national government now providing 100% of hospital budgets. Also in the 2002 reform, public hospitals had been consolidated into larger organizations, and transformed into ‘state enterprises’ that were expected to be ‘semi-autonomous managerial units’ (Ringard et al., Reference Ringard, Sagan, Saunes and Lindahl2013).

The 2012 reforms established a series of innovative legal obligations for municipal governments regarding the provision of elderly care services (Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Saltman and Vrangbaek2015):

∙ New Municipal-Region Signed Agreements. These formal agreements must be approved by the national government’s ministry of health, using national guidelines, standards and statistical indicators. They cover admission, discharge and rehabilitation procedures, as well as patient communication. These agreements also must incorporate state-approved follow-up and accountability procedures.

∙ New Municipal Financial Responsibilities. The new framework requires 20% municipal co-financing of all patient treatment in hospital’s internal medicine and outpatient departments, to encourage more effective (since 2003 private) primary care (which municipalities supervise). Moreover, the reform establishes a 4000 Norwegian crowns fee per day to be paid to the hospital by a municipality if it is not ready to take back ‘finished patients’ (e.g. bed blockers) into municipally organized long-term care/home care (this last requirement parallels similar regulations creating market-style incentives put in place between parallel public sector budgets in Sweden with its long term care or ADEL Reform in 1992).

∙ Municipal Patient Treatment Responsibilities. Every municipality must set up a MAU, capable of treating stable patients with a known diagnosis, and with observation beds for evaluation. Operating costs for these new step-down units are to be partly funded by regions.

In addition to these MAU, some municipalities also have embedded primary care units into their regional hospitals. Other nationally imposed requirements of the 2012 reform are that:

∙ every municipality must have a home-focused rehabilitation program;

∙ every municipality/region must implement National Pathways Programs, with treatment protocols for cross-sectoral conditions (diabetes, heart, etc.).

Denmark

During a similar time period to Norway, Denmark (2007–2012) introduced a roughly parallel set of new responsibilities for its municipal governments. Also like Norway, the introduction of this strengthened municipal role followed an initial structural reform, in Denmark’s case in 2007, in which the number of both municipal and also regional level governments were substantially consolidated: from over 300 to 98 municipalities, and from 14 counties to five regional councils (Olejaz et al., Reference Olejaz, Nielsen, Rudkjobing, Birk, Krasnik and Hernandez-Quevedo2012).

Subsequent to this administrative consolidation, the health care-related obligations for municipalities included 20% funding of specified hospital services by municipalities, accompanied by state-approved contracts between each municipality and its regional hospital administration for the local supply of a specified set of elderly tied services. Both changes are designed to facilitate prompt hospital discharge of chronically ill elderly and to ensure suitable residential follow-up. The national government also introduced a municipal co-funding requirement for certain ‘reduceable’ categories of hospital-provided elderly treatments (Oljaz et al., Reference Olejaz, Nielsen, Rudkjobing, Birk, Krasnik and Hernandez-Quevedo2012; Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Saltman and Vrangbaek2015). Again, like Norway, these contracts are closely monitored on a tightly specified set of activity variables: in the Danish case, statistics on acute hospital admissions, hospital re-admissions, length of time to hospital discharge after clinical treatment is complete and waiting time for outpatient rehabilitation to begin (Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Saltman and Vrangbaek2015).

One interesting pilot project from 2014 to 2017 in Central Denmark Region has sought to better coordinate hospital and outpatient elderly care by eliminating activity-based payment (DRGs) as the basis for hospital payment. In place of case-based reimbursement, the pilot re-instituted bilaterally negotiated global budgets tied to quality of outcome measures from a patient’s perspective in nine hospital departments (Burau et al., Reference Burau, Dahl, Jensen and Lou2017).

The intention of this pilot is to better link hospital performance incentives to good outcomes for elderly municipality-based and municipality-funded patients (Sogaard et al., 2015). The thinking is that if the hospital department is no longer driven exclusively by short-term financial incentives, the long-term outcomes will be better for both patients and municipal budgets. If this pilot is deemed successful, its approach will likely be mainstreamed to all Danish hospital regions.

Finland

Finland’s economy has hardly grown since the onset of the 2008 financial crisis, and its current coalition government has sought for several years to develop a new health delivery model that could simultaneously improve regional and employment-based equity as well as save public money by reducing unnecessary intensive hospital-based care for the chronically ill elderly. As noted above, after complex negotiations, the national government’s constituent coalition parties agreed in June 2016 to put in place a radical re-structuring of both the service delivery structure and of the governmental arrangements to operate that new structure. Legislation for these changes is scheduled to be presented to Parliament in June 2017.

The two fundamental changes are that, first, separate health and social care administrations are now to be fused together into a single entity, and, second, that the longstanding, highly decentralized structure of municipally operated health service providers is to be abolished, replaced instead with a new configuration made up of 18 new regional entities (Saltman and Teperi, Reference Saltman, Bankauskaite and Vrangbaek2016).

Finland’s adopted but as yet not implemented reform will incorporate the following organizational strategies:

∙ Consolidating and centralizing the administrative structure of public health providers. The adopted reform proposal will combine hospital, primary care and long-term care service providers within regional integrated bodies. To accomplish this objective, it will shift the main responsibility for operating this newly combined primary/long-term care administrative structure from 319 municipal governments (reduced from 450 until just recently) to a (somewhat formulaic) 12+3+3 set of Regional Health and Social Organizations (termed SOTE). These new SOTE administrative structures, in turn, will have varied service production rights: 12 SOTE will be entitled to produce their own services; 3 SOTE will be required to share service production with those 12 SOTE; while 3 small/rural SOTE will not be allowed to produce their own services at all, but will be required to contract all services from the other 15 SOTE (Saltman and Teperi, Reference Saltman, Bankauskaite and Vrangbaek2016).

∙ Centralizing financial/operational measures; introducing some competition for public hospital services. Under the new framework, 100% of health care funding will come directly from the national government. This represents a major centralization of control, in that municipal governments will no longer share in financing health and particularly social care services. This centralization of funding, in conjunction with the consolidation of administrative control just noted, is seen by Finnish authorities as increasing accountability and performance by dramatically reducing the number of governmental actors supervising health system decision-making. A related strategic element in this new governance structure is the expectation that competition between public hospitals to obtain SOTE contracts will introduce a dimension of competition – and thus better performance – into the heretofore fixed-catchment-area-based public system of hospital services.

One important strategic issue that as of the June 2016 official announcement had not been resolved was whether to consolidate the separate public revenue stream that the National Health Insurance System (KELA) deploys as subsidies to private health services (typically a 23% subsidy) and especially for employer-provided occupational health services (a 60% subsidy). These two separate public-funding streams, while they provide alternative routes to services for citizens who otherwise face long waiting times, especially to see a public primary care physician, are however seen by public health advocates as providing unequal access to health services overall, benefiting, respectively, the middle classes and the employed. Whether the ongoing reform strategies of consolidation and centralization will be applied to KELA is, however, a highly political topic. There is also the practical dimension that KELA-subsidized services reduce the pressure on already over-stressed public sector primary care providers, and adding those additional patients into the public system could negate any benefit achieved by re-purposing KELA’s existing public revenue streams.

England

Faced with serious financing problems as noted in Part I above, the English NHS has developed a wide range of different (sometimes internally contradictory) strategies to generate services less expensively. Over the last two decades, these have included: different strategies to encourage NHS hospitals to be managed more efficiently (Edwards, 2011); the development of the Private Finance Initiative which has enabled the NHS to commission over 100 hospitals built and owned by privately capitalized companies from whom the NHS rents the institution (Boyle, Reference Boyle2011); strategies to improve the performance and speed of patient throughput in hospital accident and emergency facilities; and to better coordinate/integrate hospital and social care services (Stubbs, Reference Stubbs2016). Despite these efforts, however, the general perspective is that the NHS has continued to sink into an increasingly serious financial and operational crisis (Stubbs, Reference Stubbs2016; Gainsbury and Appelby, 2017; Neville, Reference Neville2017).

One innovative strategy to tackle these NHS dilemmas has been to – simultaneously – introduce new forms of consolidation of service providers with decentralization of managerial responsibility. In April 2016, a pilot project was begun in Greater Manchester, for its population of 2.8 million. Under the new arrangement, overall political supervision has been delegated to a new regional council made up of 37 public health and social care organizations, including 10 Local Authorities, 12 Clinical Commissioning Groups and 15 NHS Providers (hospital groups). The total NHS budget being devolved is six billion pounds per year (Walshe et al., Reference Walshe, Coleman, McDonald, Lorne and Munford2016). This new structure is chaired by the Mayor of the Greater Manchester Council, who is himself elected by the constituent local authority councils. The concept is that this new regional body will coordinate the health-related activities of its member organizations so as to better fit the service needs of local inhabitants, and lessen spending on unnecessarily intensive hospital services.

Critics have noted that the coordination powers of the new regional body are voluntary, since each of the existing 37 organizations retains its own separate budget. However, the national NHS has given the new council 450 million pounds for ‘start-up innovative projects’ that work across existing organizational boundaries, and an inducement to develop new arrangements (Walshe et al., Reference Walshe, Coleman, McDonald, Lorne and Munford2016). In turn, whether these funds will be used effectively to improve care delivery, or whether they will be siphoned off by Manchester’s heavily politicized local authorities for preferred client groups, remains to be seen.

Ireland

Ireland’s economy was severely affected by the 2008 fiscal crisis, and its health care system’s reform strategies have followed much the same pattern of administrative consolidation that has occurred in several Nordic countries. Like these other countries with relatively small populations (three to five millions), Ireland in 2005 – much like Norway in 2002 and Denmark in 2007 – had already shifted away from the previous decentralized structure toward a more centralized arrangement. Like Norway, that new arrangement in Ireland pulled back the governance of health providers directly into the hands of the national government. Unlike these two Nordic countries, however, the last conclusive stage in Ireland’s process of provider-side consolidation occurred after the onset of the 2008 financial crisis. Moreover, the Irish approach incorporated strong references back to English provider-side measures.

In Ireland’s case, in January 2005 the four regional health and service boards were replaced by a single Health Service Executive (McDaid et al., Reference McDaid, Wiley, Maresso and Mossialos2009). Further, in April 2007, 19 Social and Health Service Trusts merged into six Health and Social Care Trusts. Following the onset of the 2008 crisis, in April 2009 these separate health and social care entities were quickly merged into a single national Health and Social Care Board in an effort to tightly control overall health and social spending, with five regional Health and Social Care Trusts and five (parallel) regional Local Commissioning Groups.

This process of full provider-side centralization stands in sharp contrast to a proposed but never concluded effort to make fundamental strategic change on the funding side of Irish health care. As part of the post-2008 effort to make health services more efficient and less expensive, Ireland from 2011 through to 2015 seriously considered replacing the existing tax-based funding structure with a social insurance-based system based on private insurance companies, similar in many ways to the post-2006 funding structure in the Netherlands (Kroneman et al., Reference Kroneman, Boerma, van den Berg, Groenewegen, de Jong and van Ginnekin2016).

The proposed Irish funding reform was to shift from 77% tax-funding to 100% SHI-funding (Burke et al., Reference Burke, Normand, Barry and Thomas2016; Connolly and Wren, Reference Connolly and Wren2016).

In 2011, the government proposed a shift to Universal Health Insurance (UHI), to start in 2016. Subsequently, in April 2014, the government set out a ‘multi-payer model’ of compulsory private health insurance, in which for-profit private companies would operate in competition with each other; however, some socially sensitive health care services would remain tax-funded (these were, however, unspecified). This new model was proposed to start in 2019.

In July 2014, a new Health Minister was appointed, who ordered a report on the potential cost implications of the proposed funding shift. Issued in November 2015, that report concluded that UHI would increase costs between 3.5 and 10.7% per annum, and that the main cost-increaser, citing experience from the Netherlands, was ‘multiple, competing insurers’. In response to this report, the Minister declared that the proposed shift to an SHI-based funding structure was ‘not affordable now or ever’, ending Ireland’s interest in this line of funding reform (Burke et al., Reference Burke, Normand, Barry and Thomas2016).

The importance of this ultimately unsuccessful process extends beyond Ireland, in that this was the only tax-funded health care system in Northern Europe post-2008 to seriously consider major reform on the funding side of its health care system. Ireland was also the first country to seriously consider shifting from a tax to an SHI-based funding structure since UK Prime Minister Thatcher in 1989 briefly considered a similar shift. Ultimately Thatcher also rejected the proposed funding conversion for the same reason as did Ireland in 2015: in both instances, the government’s fear was that an SHI-based system would turn out to be less tightly controlled than a national tax and budgeting system, and thus would ultimately become more expensive to the national treasury (Connolly and Wren, Reference Connolly and Wren2016).

Here it also may be worth noting that the only Northern European country that actually did shift its core funding framework for hospital payment in the past 50 years was Denmark in 1973, moving in the opposite direction from Ireland’s proposed path. Denmark shifted from its prior quasi-German SHI arrangement to a Swedish-influenced regional–government-operated tax-based funding structure (Oljaz et al., Reference Olejaz, Nielsen, Rudkjobing, Birk, Krasnik and Hernandez-Quevedo2012).

Overall, Ireland’s health reform process speaks directly to two important dimensions of the search for new health system strategies in the post-2008 environment. The first is the continued interest in the consolidation of public providers into larger and more tightly – typically nationally – managed units.

The second reform dimension is, simply, the difficulty of shifting fundamental funding structures in tax-funded health systems. Much like Sherlock Holmes’ famous dog that did not bark, existing patterns of successfully implemented post-2008 reform strategies suggest that in these health systems, major funding shifts would disrupt too many settled organizational and political patterns and therefore are unlikely to be attempted.

Part IV: Innovative post-2008 reform strategies in SHI systems

SHI-funded health systems have had several examples of interesting post-2008 crisis reforms, focusing mainly on the funding side, along with the (allocation) methodology for paying providers. The more noteworthy national initiatives have included the following:

∙ Replacing long-term care insurance with municipally led home-based care (the Netherlands)

∙ Shifting premium increases away from employers onto employees (Germany)

There also have been a range of pilot projects pursued at the regional level, often seeking to reduce the cost of long-term and chronic elderly care. While some of these began just before the onset of the 2008 financial crisis, they gained growing importance and attention as events in 2007 and 2008 unfolded. Among the more notable trial projects in this arena have been:

∙ Integrating home care, primary care and hospital outpatient services for chronically ill elderly care in Germany, the Netherlands and Austria (Nolte et al., Reference Nolte, Knai and Saltman2015): (Gesundes Kinzigtal, Southwest Germany); (Matador disease management program, Maastricht, NL); (Diabetes Management Program, Salzburg, Austria).

∙ Developing innovative multi-level programs of individually tailored elderly care services in the Netherlands such as Residentie de Saafir in Den Haag and Cordaan in Greater Amsterdam.

The Netherlands

In the Netherlands, long-term care insurance was radically re-structured in 2015. The longstanding (since 1967) universal insurance structure for long-term care – the AWBZ – was discontinued at the end of 2014. Its funding functions were folded as of January 2015 into a new municipality-based structure (mandated by the 2015 Wlz or Long-term Care Act (Wlz)) that places responsibility for caring for home-bound elderly on, sequentially, the individual’s immediate family, the community (especially churches and social groups), primary care, intermediate health facilities (such as municipally based observation beds) and, only as a last resort, hospital-based staff and/or facilities (Kroneman et al., Reference Kroneman, Boerma, van den Berg, Groenewegen, de Jong and van Ginnekin2016).

The new, complex and socially differentiated structure for home care co-payments illustrates the focus of the new regime. Under the Wlz, after the first 6months of care, those home care recipients who live alone must pay the ‘high co-insurance rate’, consisting of ‘the patient’s total taxable income and part of their assets with a maximum of 2285 euro per year in 2015’. Those recipients who live with a ‘partner and/or dependent children’ pays the ‘low co-insurance rate’ which is ‘12.5% of income … with a 159 euro minimum and a 833 euro ceiling per month in 2015’ (Kroneman et al., Reference Kroneman, Boerma, van den Berg, Groenewegen, de Jong and van Ginnekin2016: 89). This co-payment structure represents a dramatic shift from the previous AWBZ insurance-based payment structure to providers. It also creates a strong incentive for elderly recipients to move in with their children, thereby enabling at least some informal caregiving.

Formally, the 2015 Dutch home care reform consists of three linked legislative acts:

1. Long-Term Care Act. This provides institutional care and/or 24-hour home care. It is funded by mandatory, individually paid premiums of 9.5% of salary up to an annual ceiling of 33,000 Euros. These premiums are paid directly to either the Netherlands’ private for-profit health insurance companies or its private not-for-profit SHI funds.

2. Health Insurance Act. This legislation provides home care nursing services and personal care for individuals, provided by medically trained or supervised staff, who require less than comprehensive services. It is also paid for by the mandatory individual premiums paid to private insurers by each Dutch adult, as in (1) above.

3. Social Support Act. This legislation covers the provision of non-medical domestic care and social support in the individual’s home. Under this new legislation, these support services are paid for by municipal governments.

An important element of these 2015 legal changes concerns the determination of eligibility for services. Eligibility for (1) and (2) above is determined by a newly established independent national agency, the Centre for Needs Assessment, which uses fixed national protocols tied to an individual’s Independent Activities of Daily Living assessment. Eligibility for (3) above is determined by municipal government teams, who first hold a discussion with the patient – termed a ‘kitchen table dialogue’ – to establish whether the needed domestic support can be obtained from family, neighbors or private associations (e.g. church groups), before committing to providing these services from the public tax-funded budget (Maarse and Jeurissen, Reference Maarse and Jeurissen2016).

In sum, the overall approach of the 2015 elderly care reforms is to find all possible alternatives before committing to publicly funded support.

The key premises of the new Dutch elderly care strategy include:

∙ A substantial shift of clients from residential to non-residential settings

∙ Decentralize home care clients from (prior) National SHI Fund (ABWZ) to Municipalities

∙ Some social services to be provided by family members and local community networks (Maarse and Jeurissen, Reference Maarse and Jeurissen2016).

Among the alternative measures that the 2015 reform has set in place are:

∙ Emphasis first on social network: family and friends (informal caregivers)

∙ Option of a ‘personal budget’ (currently 9% of LTC total expenditure in the Netherlands)

∙ Municipalities may introduce co-payments

∙ Municipalities have created ‘social district teams’

o To help citizens solve problems through their informal network

o To help solve social problems, especially in deprived neighborhoods

Since 2015, domestic care funding for long-term care has been cut by 30%, which has served to create strong fiscal pressure to implement the new arrangements (Maarse and Jeurissen, Reference Maarse and Jeurissen2016).

Taken overall, the new long-term care reform arrangements in the Netherlands seek to establish a framework for domestic support and/or social services that can in various ways reduce fixed public cash expenditures and involve more family, community, and other non-publicly funded actors and resources:

∙ Reduce institutionalization costs inherited from former SHI/LTC fund (ABWZ).

∙ Shift financial responsibility for home care to municipalities/taxes.

∙ Require local social teams to divert potential recipients if possible.

∙ Give clients ‘personal budgets’ to purchase/combine in community networks.

∙ Increase donated/informal caregiving (family/community).

Germany

Germany has made a series of reform changes to its funding and delivery structure for health care services since 1989 (Busse and Blumel, Reference Busse and Blumel2014), however, most of these reforms introduced incremental, stepwise changes. The 2009 funding reform, quite differently, was of a more fundamental structural character. This national legislation replaced the sickness-fund-based funding of health care (a model in place since 1883 in which contribution rates were set by each individual fund), with a new, nationally structured pool that collected a fixed national contribution rate paid by all covered citizens (Göpffartha and Henke, Reference Göpffartha and Henke2013). Moreover, this new structure also broke with the traditional 50% employer–50% employee premium assessment model. Instead, seeking to respond to the serious economic aftermath of the 2008 crisis and worrying about the international competitiveness of German exports, the 2009 German reform leveled a higher premium – 7.5% of salary up to a ceiling of 48,000 euros – on employees than the 7.2% of salary levied on employers. Further, the amount paid by employers was frozen, which in turn meant that the increase in premium revenue required in 2011 (due to continued high unemployment) was paid by employees, who saw their premium payments raised to 8.2% while the employer portion remained steady at 7.3% (Göpffartha and Henke, Reference Göpffartha and Henke2013).

The overall impact of this change in health funding strategy has been to shift what had been a shared responsibility in the private sector, between employers and employees (admittedly under national statutory requirements), into what became by 2012 both a nationally tax-based structure that was federally controlled, and a funding framework which financially favored employers over employees. The political intentions in making this long-discussed but only post-financial crisis-implemented reform were fourfold:

a. equalize social insurance contributions across the more than 100 separate social insurance funds;

b. apply risk-rated payments to each insuree, to encourage insurers to compete for new enrollees;

c. restrain overall health sector expenditures through one national channel;

d. improve the international competitive position of German industry, by capping its share of health insurance premiums.

While all four objectives had been important before 2008, they became even more so once economic growth slowed over the longer term.

Part V: Concluding observations about reform policy patterns

The broad post-2008 pattern of health sector reform in Europe presents a complex landscape of new and previously existing strategies, in response to the different focus of policy concerns found within tax-funded as against social health insurance-funded health systems. The central concern for all European health systems, however, continues to be responding more effectively to the challenges raised by the down-shifting of economic growth to levels that pressure revenues for all publicly supported services, and especially for health care services. This additional fiscal pressure comes, as many have noted, at the same time that numerous other challenges already are placing substantial strains on public-funding levels for these health care systems.

Two strategic axes of organizational change within these different reform patterns can be charted:

1. a shifting set of balances between decentralization and re-centralization on various administrative and governance dimensions; and

2. wide-ranging consolidation among public sector producer organizations, both horizontally (e.g. combining hospitals into fewer multi-site organizations as well as hospital-primary care-home/social care services under one administrative roof) and vertically (contracting direct governmental supervision into fewer regional administrative bodies).

These two main reform threads interact with each other in a series of inter-relationships that shift depending upon funding structure type, social norms and values of national culture, and near-term political objectives of sitting governments (Saltman, Reference Saltman and Teperi2015). Most notably, both reform threads have been deployed in a number of country cases detailed above seeking to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of caring for chronically ill elderly, and re-structuring the mix and delivery of various types of long-term care services.

One intriguing reform strategy discussed above combines decentralization of clinical and financial responsibility for many aspects of care for chronically ill elderly to the municipal level of government, simultaneously with the consolidation and centralization of public governance to larger units at the regional level. Thus, decision-making authority is re-configured in a split manner, simultaneously de-centralizing and centralizing different types of public sector responsibility and controls. Both Norway and Denmark serve as examples of this multi-directional new governance strategy. Somewhat similarly, the Netherlands provides a model of a SHI system that also has pushed substantial parts of the care and maintenance of chronically ill elderly down to municipal and, below that, to the private sector community and household level.

As initial responses to the combined fiscal and service delivery pressures that European health systems have faced, these reforms appear well targeted and focused. Particularly on the service consolidation dimension, they appear to hold the potential to stretch available public health care funds while at the same time achieving a more clinically and socially successful set of outcomes. In this regard, they represent what could be viewed as a positive result from the negative funding consequences of the 2008 financial crisis, in effect forcing policymakers to adopt needed structural reforms. Some might argue that this outcome may be more in the category of picking potential winners and losers, e.g., streamlining care and procedures in one sector while other sectors (hospitals in particular) continue to face increasing financial pressures. Opponents of the restructurings sometimes contend that these changes shrink the welfare state’s footprint and thus damage overall service availability for certain groups of citizens (see especially debates in Ireland and in the Netherlands).

Viewed analytically, how effective these new reform strategies will be in reducing the fiscal pressure on Northern European health systems, and their overall impact on the quality and safety of necessary long-term care services, will need to be carefully considered once comprehensive evaluations of these reforms become available. In particular, how much of the needed new funding to meet technological, informational and staffing needs particularly in hospitals will be freed up by more effective extramural services for the chronically ill elderly has not yet been documented.

Past experience highlights the difficulties in achieving real savings. The literature on decentralization as against centralization (or re-centralization) strongly suggests that the advantages of economic (competition between local units) and democratic (closer to the citizen) decentralization are often in a rough balance with each of these strategies’ disadvantages (e.g., economic duplication and, politically, unequal outcomes across districts) (Saltman et al., Reference Saltman2007). Similarly, previous efforts to combine or consolidate publicly operated providers – especially hospitals – have suggested that the fiscal advantage may be small given fixed costs tied to public sector employment guarantees, resistant employee unions and political tendencies to not close (and reduce employment) but rather re-purpose surplus public buildings for other equally publicly funded purposes (day facilities, walk-in clinics, etc.) (Saltman, Reference Saltman2008). Further, past experience in countries like Sweden has demonstrated that additional public costs are incurred to adequately fund support programs used to assist and sustain informal caregiving in the home, e.g., telephone hotlines, respite care, day-care programs and pension points toward state pensions for family members who provide home delivered care (Johansson, Reference Johansson1997; Saltman et al., Reference Saltman2006).

There are also concerns about pushing more residential elderly care services back to the community and the family. One key question is whether this more traditional family-based care framework can be made to fit with current work, housing and social patterns (Boerma et al., 2012), suggesting that the success of this strategy may well vary depending upon the individual country culture and context. A second concern can be the potential equity-related issues in obligating families to take a larger role in elderly care delivery, especially with regard to forgone income.

These counterbalancing factors influence the degree to which similar efforts in Canadian provincial health systems could be successful. Consolidating hospitals and integrating hospital, primary and social care arrangements continue to be discussed and pursued. However, these debates take on a different character in the much larger geography of, say, the western Canadian prairie provinces from settlement patterns in much physically smaller Northern European countries. Similarly, the continuing debate over centralizing (Alberta and Saskatchewan) or de-centralizing (Quebec) provincial health administrations suggests the institutional path to greater fiscal efficiency in Canadian health care is not yet clear.

However, Canada too suffers from the disjunction between the slow-growth fiscal consequences of the 2008 financial crisis and the expansive health sector fiscal needs created by technology, demography and information science. Much like recent rates in Europe and also the United States, Canada’s GDP grew 1.9% in the fourth quarter of 2017, and it carries a public debt to GDP ratio in 2017 of 104%. Given its similar macroeconomic picture, then, the demand on available public funds for health care in Canada is also likely to remain greater than the likely supply. Thus, for Canada too, the central lesson here may be that European reform approaches should be adapted and pursued, and that they have a valuable contribution to make to the overall quality and efficiency of health services, however, the funds freed up by these consolidation and integration reforms will not themselves alone be sufficient to meet current and future demands for services.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank participants at the AMS 80th Anniversary Symposium at the University of Toronto and two external reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this paper.