On the opening pages of Frank Norris's The octopus (1901) – one of the most renowned novels of America's ‘first gilded age’ – readers are offered a vision of the entity responsible for all the evil that has befallen the American republic of late: the corporation.Footnote 1 Symbolizing that entity by the infamous Southern Pacific Railroad, which had established operations in Western states in the 1860s and 1870s, Norris begins his novel with an image of the corporation as a demigod – ‘a Leviathan of Iron and Steel’.Footnote 2 As Norris describes the book's protagonist, he writes:

Abruptly he saw again … the galloping monster, the terror of steel and steam, with its single eye, cyclopean, red, shooting from horizon to horizon; but saw it now as the symbol of a vast power, huge, terrible, flinging the echo of its thunder over all the reaches of the valley, leaving blood and destruction in its path; the leviathan, with tentacles of steel clutching into the soil.Footnote 3

The corporation was a ‘soulless Force’, an ‘iron-hearted Power, the monster, the Colossus, the Octopus’, an impersonal entity.Footnote 4

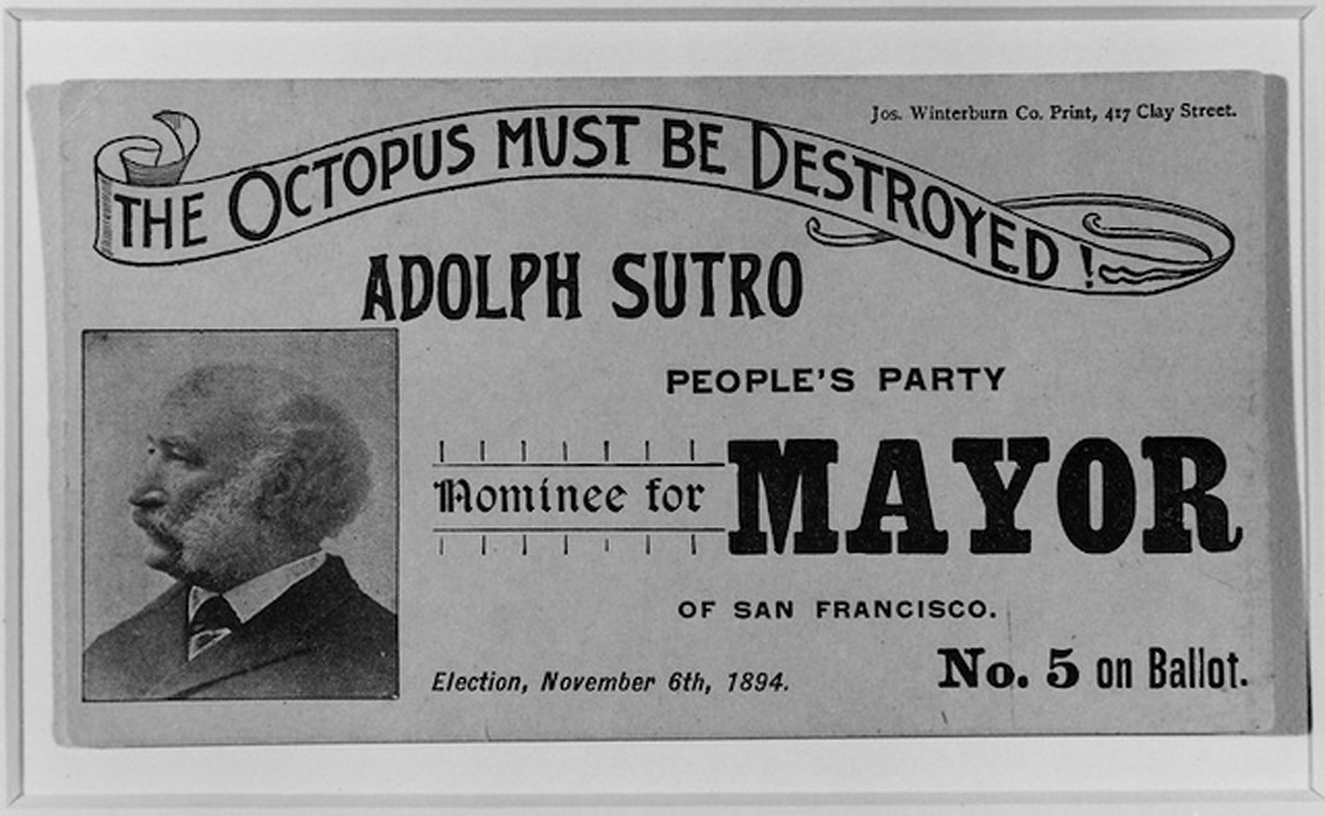

By 1901, the question thrown up by Norris – was the corporation a person or not? – had acquired an importance that was far from exclusively literary. As historians of the gilded-age Midwest have noted, Norris based his novel on a dispute that occurred between farmers and the Pacific Railroad in a California basin known as the 1880 ‘Mussel Slough tragedy’, an incident eagerly reported in the local press.Footnote 5 The company owed its codename, ‘the Octopus’, to its capacity to influence local legislatures, bribe law-makers, and buy up land to lease to small farmers, who had become especially sensitive to corporate malfeasance.Footnote 6 The corporation's activity did not go unnoticed, of course. During the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s, movements such as the Grangers, the Greenbackers, Farmers’ Alliances, and the People's Party resisted the ambitions of new corporations – either legislatively or, in the case of Mussel Slough, with physical force. In 1894, the Jewish Populist Adolph Sutro ran for San Francisco mayor under the slogan ‘The Octopus must be destroyed!’ (Figure 1), while Populist candidates peppered electoral speeches with anti-corporate invective throughout the decade. Together with Ignatius Donnelly's Caesar's column, Henry Demarest Lloyd's journalism, and L. Frank Baum's Wizard of Oz, The octopus steadily became part and parcel of what historians now term ‘the folklore of populism’.Footnote 7

Fig. 1. Campaign pamphlet for San Francisco mayoral race on Populist ticket, 1894.

Source: University of California, Berkeley, Bancroft Library, Adolph Sutro Jr papers, BANC MSS C-B 465.

Historians and political theorists have regularly followed Norris in presenting late nineteenth-century Populist radicals as orthodox opponents of this new corporate ‘octopus’. From 1870 to 1890, corporations emerged as the primary actors in a new capitalist economy, cornering ‘natural’ individuals such as farmers, artisans, and workers, and strengthening the belief that America had drifted away from its status as a yeoman republic.

The present article challenges this opposition between Populists and corporate intermediaries. Instead of pitting Populists against the ‘octopus’, it shows how they deployed theories of incorporation to rethink older republican commitments. In doing so, the article uncovers a complex set of arguments on executive and legislative authority, corporations, and popular agency from an under-examined corpus of Populist texts. Populist theorists began by reclaiming the artificial person of the corporation to combat existing monopolies in railroads, credit provision, and banking in the 1870s and 1880s. In this earlier period, radicals put forward ideals of co-operative association as new safeguards for republican government. When these efforts ground to a halt in the late 1880s, Populists increasingly began to move to the level of the state, where they hoped to expand state and federal capacity without increasing administrative privileges. Speeches, pamphlets, treatises, and election booklets by Populists from 1880 to 1910 demonstrate how Populist theorists sought to rethink a new ‘general incorporation regime’ to their own benefit. While these Populist texts often operate on a different level of abstraction from today's writing on populism, reframing them as works of political theory allows for productive conversations both with political philosophers and with historians of Populism today.

The article's argument is laid out in two stages. A first section focuses on current discussion of populism in political theory and historiography and how these conversations model Populism's relationship to the question of corporate intermediary power. In both history and political theory, Populists are presumed to oppose the very existence of corporate intermediaries, chiefly because of their artificial nature. Such retrospective visions – often indebted to a specific strand of post-war historiography derived from Richard Hofstadter – hardly capture the original Populist movement's engagement with the corporation, however, and how Populists saw their visions of state expansion as responding to corporate concentration.

A second part counters the premises of this literature through an overview of Populist writing on the corporate question in the late nineteenth century. Rather than rejecting the new intermediary instrument of the corporation, Populists reimagined their national republican tradition through the lens of the corporation's co-operative promises, thereby turning ‘the corporation in on itself’.Footnote 8 The article finishes with an overview of the relevance that this material holds for both political philosophy and existing historiography on Populism. By focusing on the writings of Populists such as Georgia's Thomas E. Watson (1856–1922), Kansas's William Peffer (1831–1912), Iowa's James B. Weaver (1833–1912), and Texas's Charles E. Macune (1851–1940), the article thus contests narrow visions of Populism as a reflexively anti-corporate movement.

I

The publication of Norris's The octopus in 1901 marked the crest of a wave of sprawling anti-corporate literature dating back to the 1870s. Omnipresent in the late nineteenth century, the trope of a corporate ‘octopus’ also continues to hold a surprising salience for contemporary political theory. The political bent of Norris's novel – the story of a how a people of ‘natural’ and propertied individuals resist the rise of an abstract entity known as the ‘octopus’ – sits remarkably well with trends in recent populism scholarship. As Jonathan Hunt notes, Norris tried ‘to suture the divided interests of the population into the single hegemonic formation of “the People”’ against the “Octopus”’ – the enemy that split and divided a natural polity.Footnote 9

The corporation's function as an intermediary between state and individual also plays a paramount role in Norris's story. As proponents of a ‘naturalist democracy’, his farmers object to business corporations precisely because of the forms of intermediation they imply, placing themselves between individual and state and concentrating political and economic power.Footnote 10 The corporate question had become a pressing one for farmer radicals in the late nineteenth century. The 1870s and 1880s saw the further consolidation of the so-called ‘general incorporation regime’, in which corporations increasingly gained legal leeway which freed them from state oversight. The results of this new regime were far-reaching. Even more than churches and non-profit organizations – which can also claim legal representation – the new business corporations shaped markets, influenced political affairs, and mediated an individual's relationship to the state. Above all, they put into question the latter's claim to exclusive sovereignty as a rival ‘corporate sovereign’.Footnote 11 In this story, ‘big-p’ Populists opposed corporate personhood precisely because it constituted the recognition of an institution unbeholden to the state's sovereignty.

This critique still bears a striking parallel to contemporary scholarly conversations on ‘small-p’ populism. In an analogous manner to Norris's opposition between ‘natural’ farmer and ‘artificial’ corporation, recent theorists have cast populism as a ‘revolt against intermediary bodies’ (Nadia Urbinati), an ‘institutional simplification directed against intermediary powers’ (Pierre Rosanvallon), or an ideology that ‘avoid[s] intermediary organizations that may distort the popular will’ (Noam Gidron and Bart Bonikowski).Footnote 12 Although not necessarily in agreement over the exact relationship between populism and democracy, all of these scholars share the consensus that populist movements and their leaders are opposed to the group life of liberal democracies where groups can gather freely through their usage of the corporate form.Footnote 13

Contemporary theorists tend to extend this attack on intermediary bodies into a distaste for parliamentary representation in general. Nadia Urbinati argues that populists condemn ‘intermediary institutions like parties and parliaments’, promote ‘personalistic forms of representation’ centred on leaders, and ‘call for strong executive power’.Footnote 14 Such an antipathy to intermediary power is easily traced back to nineteenth-century Populism as well by using an analogous set of oppositions. As Urbinati notes, the People's Party of the late nineteenth century ‘claimed the emancipation of the nation from “money power” (artificial) in the name of property and labor (natural)’, while its preference for ‘directness versus indirectness’ mirrored other populist binaries such as ‘popular movements versus institutional politics’.Footnote 15

Populist sceptics like Urbinati are not alone in positing this opposition between populists and intermediaries, however. Even writers more sympathetic to populist movements, such as the Argentinian theorist Ernesto Laclau, have claimed that American Populism relied on strong leaders to constitute the ‘people’ as ‘having universal-equivalential identifications … over sectorial ones’.Footnote 16 In his On populist reason (2005), for instance, Laclau insists that the people's foundation as an agent was ‘provided by the presence of a leader’.Footnote 17

Urbinati's and Laclau's judgements on Populism find support in older trends in American historiography. Going back to Richard Hofstadter's seminal The age of reform (1955), a previous generation of historians cast Populism as a nostalgic withdrawal into Jeffersonian individualism, opposed to ‘big government’ and corporate gigantism. Once their anti-corporate campaign failed, disgruntled Populist farmers were drawn to forms of ‘leadership democracy’ centred on plebiscites and referendums, shortcutting the mediation which usually takes place between individuals and states. As James Livingston summarizes the Hofstadterian view, the Populist tradition ‘could not acknowledge the legitimacy of the large corporation’ and was therefore incapable of ‘accommodating to … the new possibilities of political community enabled by corporate capitalism’.Footnote 18 Populists thus did ‘not seek to utilize the new forms of industrial organization and managerial expertise for the betterment of society’, instead wanting to restore ‘economic individualism’ through ‘morality and civic purity’.Footnote 19

In the 1950s, this view of ‘small-p’ populism garnered considerable support in political science as well. Figures such as Edward Shils, Seymour Martin Lipset, and Daniel Bell in particular set up a rigid binary between pluralist and populist regimes in the field, with the first respectful of civil liberties and the rights to association and the second suffocating association in the name of a Bonapartist leader.Footnote 20 Although this binary between populism and pluralism underwent a sustained attack in the course of 1970s – most notably in the work of historians such as Lawrence Goodwyn, Robert McMath, Norman Pollack, Walter Nugent, and, earlier, C. Vann Woodward – it is only recently that historians of Populism have explicitly begun to contest the idea that the movement's political philosophy supports a Hofstadterian interpretation.Footnote 21 As Charles Postel (the most prominent of these critics) notes, the true experience of the Populist coalition was one in which there was intense usage of intermediary bodies such as co-operatives, unions, and brotherhoods, not an evacuation into frontier individualism coupled with powerful executives. Thus far, however, this pushback has remained within the discipline of history: as Postel claims, ‘mainly outside of the historical profession’, the ‘Hofstadter thesis has maintained its influence on political analysis’.Footnote 22

Hofstadter's reading has also left subtle traces in Populist historiography itself, but mainly when it comes to Populism's view of the corporate intermediary. For example, Charles Postel's own 2007 The Populist vision offers a portrait of Populists as confident and open modernists, characterized by a ‘preoccupation with “scientific government”’ and ‘a nonpartisan, managerial, and government-as-business vision of politics’.Footnote 23 Naturally, Postel extends this interpretation to Populism's vision of the new industrial corporation. As Robert McMath notes, Postel's account rightly ‘highlights that farmers act[ed] in national markets dominated by giant corporations’ with ‘their energies’ focused ‘on national solutions involving countervailing federal bureaucracies’.Footnote 24 Coupled with their ‘strong antiparty sentiment and the beginnings of interest group politics’, however, such a vision ‘yields a definition of Populism as a kind of proto-corporatist phenomenon, a precursor to early-twentieth-century business progressivism, of which the agribusiness-farm bloc-land grant college complex was an integral part’.Footnote 25

Although a useful corrective to previous Hofstadterian and counter-revisionist readings, Postel's exploration of Populism's corporate engagement also does not move fully beyond the anti- or pro-corporate frame set up by Hofstadter. Postel has contested Elizabeth Sanders's reading of Populism, stating that programmes such as the sub-treasury loan system (a scheme which allowed American farmers to store their grain and other commodities in government-tended warehouses) put forward by Populists constituted considerable enlargements of federal discretionary bureaucracy. And although Postel is right in emphasizing Populism's statist bent, his reading places Populism in a discretionary corner and obscures the Populists’ genuine fears about executive expansion – as many later phrases in their Omaha programme exemplify. Two modes of state expansion are usually contrasted here: on the one hand, statutory reform based on parliamentary law-making and, on the other, discretionary reforms focused on administrative agencies. Populists preferred statutory expansion in principle but supported discretionary expansion in practice, recoiling from some of its results. In Postel's case, a one-sided notion of a pro-corporate ‘modernity’ thus tends to blur the specificity of the Populist reform programme, its ‘associational form’, and how it distinguished itself from ideological competitors on the corporate question.Footnote 26 As Noam Maggor adds, Postel's vision still leaves scholars with the question of ‘what precisely set the populist agenda apart from the reigning liberal orthodoxy’, and why several later Populists found themselves out of tune with the reforms of the Progressive era. These reforms were weighted more heavily towards bureaucratic agencies and less anchored on parliaments.Footnote 27

This interpretative difficulty extends to Populism's engagement with the corporation. To Postel, Populists’ co-operatives were uneasy imitations of corporate ventures and ultimately strove for the same political economy as their corporate competitors. Postel's schema thus suppresses the possibility that Populists did not simply seek integration into the new corporate economy. Rather, their plans aimed to alter the very terms on which that economy was to operate, preserving smallholder democracy in an age of increasing complexity and mediation. While Hofstadter's empirical claims have been successfully marginalized, his conceptual grid seems to have survived intact.

The remainder of this article argues against the Hofstadterian legacy manifest in both contemporary populist theory and sections of Populist historiography (the Populist Party is here taken as paradigmatic for an original ‘populism’, since this was the movement that launched the very word itself).Footnote 28 The article shows how, rather than seeing it as an entity which needed to be rejected, Populists recuperated the corporation as a way of transcending the limits of an individualist producerism and grouping farmers in larger co-operative units. To this end, the next section focuses on Populist co-operative farming efforts and how these adapted notions of corporate personality, while the succeeding part looks at two different Populist projects for legislative reform (the sub-treasury loan system and anti-trust action), both pursued when action centred on associations and co-operatives became insufficient.

II

In an 1891 speech later included in his People's Party campaign book (1892), the leading Populist politician (and later vice-presidential nominee) Thomas E. Watson informed a group of Southern farmers of the greatest danger facing the American republic: ‘In the tremendous oppressiveness of the System, the chief factor of cruelty, greed, corruption and robbery, is the Corporation.’ He continued, ‘whenever half a dozen men made up their minds to swindle somebody, they always went and incorporated themselves’.Footnote 29

Like Norris, Watson thought that corporate personhood (the representation of corporations in a court of law, including its ability to hold property separate from managers and directors) was little more than a veil for brigandage. In such a system, he claimed, individual actors could conceal their avarice under a layer of legal abstraction and evade individual accountability: ‘When Jones steals a horse, Jones must face the music. But when a corporation composed of Jones and thirty-nine other thieves steal a Railroad, the Corporation gets the money.’Footnote 30 He argued that the ‘natural person takes his place in the community with the understanding that his status may be altered by the community at any time’.Footnote 31 However, ‘A corporation occupies a higher and better position than a natural person. The status of the latter may be changed by law; that of the former cannot.’Footnote 32 Subsequently, Watson made an unabashed call for the re-establishment of state supremacy over corporate derivatives. ‘The State granted every one of the charters’, and, ‘what the State gave, the State can take away’.Footnote 33

Watson's words hinted at the new incorporation regime which had solidified in the second half of the nineteenth century. From the 1810s onwards, American lawyers, law-makers, and judges had steadily eased restrictions on corporate formation, whittling away at the stricter power to create corporations that characterized the post-Revolutionary eras.Footnote 34 As noted by Katharine Jackson, prior to the ‘general incorporation regime’, corporations were created on the initiative of the state in a system which privileged ‘government’ over ‘society’ for corporate rights.Footnote 35 Such an order set out a clear chain of command between grantees and governments. Corporations were dispatched for tasks that private sectors were ill-equipped to handle, burdened by transaction costs and excessive risk-taking.

In the course of the nineteenth century, this old corporate order underwent a steady reversal. Corporations were able to gain and sustain legal privileges such as legal immortality, a lessening of ultra vires rules (rules by which corporations had to abide and which set standards for their behaviour), options of limited liability for shareholders and directors, and a swathe of subsidies to corporate contractors.Footnote 36 Courts were paramount actors in these developments. In a series of landmark Supreme Court cases throughout the 1800s, for instance, judges ruled that corporations were private entities (Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 1819), that they counted as ‘citizens’ entitled to representation in courts (Marshall v. Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, 1853), and that they enjoyed full constitutional rights as citizens in accordance with the Fourteenth Amendment, which first stipulated voting rights for freedmen in former Confederate states (Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Co., 1886).Footnote 37 Again, none of these cases implied that corporations were cast as natural persons who pre-existed their charters; their justification remained one of ‘private artificial entity’, to use Morton Horwitz's phrase.Footnote 38 Nonetheless, general incorporation severely reconfigured the relationship between American states and corporations, with the latter now conceived as ‘pre-State and pre-law … persons’, spontaneously created by ‘the mere association of individuals’ through contracts and not through approvals from governments.Footnote 39

Economically, general incorporation brought significant benefits. It allowed businessmen to navigate complex legal systems, reduce transaction costs, innovate management techniques, and raise formidable amounts of capital stock. Most importantly, however, the granting of state charters meant that corporations often acquired inordinate market power. This development was felt acutely by Southern and Midwestern farmers, as corporations controlled the distribution and circulation of their crops in both national and international markets. Such practical monopolies often meant a turn to exclusive pricing practices, in which market access for smaller producers (mostly cash-crop farmers) was severely restricted, and price-gouging was common practice. As intermediaries, corporations began to appear as undeniable scourges on agrarian development.

A recurrent response by early Populists to this shift from a ‘special’ to a ‘general’ incorporation regime was to resort to an older, more state-centred theory of incorporation. Radicals here reached back to a previous ‘grant theory’, which stipulated the corporation's dependence on state power and its invalidity as a political unit.Footnote 40 The Populist presidential candidate James B. Weaver claimed in his 1892 election booklet, ‘Of our fundamental law the individual is the only rendering which should be tolerated. Men and women – not corporations – are the glory of the state.’Footnote 41 The North Carolina Populist James Davis used a similar turn of phrase in an 1894 pamphlet, claiming that the American state's decision to create corporations ‘blew the breath of perpetual life’ and ‘personal identity in a mere ideal being’ which was

more independent of State control than the citizen, and of greater vitality, to move among natural persons without further control. … Surely we should expect strong reasons to authorize the continuance … of such a gigantic man power, with soulless existence, moving, acting and dealing in the walks of men.Footnote 42

It was to this precise problem of how corporations acted as intermediaries between individual farmers, markets, and states that Populism saw itself providing an answer.

Two deeper questions were at stake here for Populist theorists. The first concerned the status of corporations as organizational forms. Despite their trenchant critique, Populists were also inspired by the political and economic power of the corporation and had contemplated organizations that could emulate some of their characteristics (although to different ends). As the Populist newspaper editor Benjamin O. Flower put it in the late 1890s, the modern corporation proved ‘the superiority of the modern combination over the wasteful and warring competitive system of the past’ and could realize ‘the dream of brotherhood in America’.Footnote 43 Populists openly wondered whether the corporation's logistical features could be recuperated, even though they themselves were unreliable, ‘soulless monsters’.

The second issue concerned the relation between corporations and states and how the former constrained the latter. Could corporate bodies count as valid bodies next to the state, and what precise role were states to fulfil vis-à-vis corporations? Instead of abolishing corporations altogether, this second option would require the shaping of an environment in which specific types of corporations could flourish, and others would be subdued into responsibility. These questions also remained visible in the double trajectory that Populist organizers undertook in the 1880s and 1890s: from society to state, from association to legislation, or, as they themselves put it, from a ‘corporate’ to a ‘co-operative commonwealth’.

III

Since the early 1880s at the latest, figures within the orbit of the Southern Populist movement had sought to counter the corporate problem with greater institutional specificity. For instance, the Texas autodidact economist and lawyer Charles E. Macune – himself president of the Southern Farmers’ Alliance – hoped to construct a system of distribution and circulation parallel to the corporate circuit. Its aim was to liberate agrarian producers from the cycle of debt peonage and price depression which ailed them in the 1880s and 1890s, mediated mainly through local merchants and larger planters. In the course of the 1880s, Macune became a renowned pedagogue within the alliance, known as an ‘organization man par excellence’.Footnote 44 After spending time on the Texas frontier in the 1870s, Macune had emerged as a figure in Populist politics in the early 1880s, elected to his state's executive alliance in 1886, only to serve as organizer of a series of state exchanges later. In 1889, he became editor of the Populist weekly the National Economist, pushing the movement's proposals in Washington.

Although Macune has figured in previous Populist histories, the intellectual sources of his co-operative approach have been left comparatively under-researched. His popular economy was a heterodox attempt to grapple with the corporate revolution that had taken place in the second half of the nineteenth century. Accordingly, his vision of the alliance movement was a ‘business organization for business purposes’.Footnote 45 As he saw it, alliances should stay out of party politics and instead focus on fighting corporate actors on their own terrain, using the opportunities of a new incorporation regime. The farmers’ main task, in Macune's view, was to form their own ‘combinations’ – new intermediary bodies that could take on the malevolent corporate ones which had taken over America's markets. There was a deeper philosophical relief to this claim. As Jeffrey Sklansky has noted, Macune placed the alliance's ‘agricultural collectivism’ in opposition to the ‘fiduciary trusteeship’ of corporate administrators, in which producers were separated from their product and absentee landlords could skim off the fruits of agricultural labour.Footnote 46 Stock-ownership and bondholding implied that owners had little practical acquaintance with agriculture. Co-operatives might gather funds in similar ways to corporations, but they could not adhere to the same shareholder philosophy. Yet they had to remain interest-based organizations at heart; as the Midwestern Populist William Peffer put it in the early 1890s, ‘the farmers and their co-workers’ ought to ‘organize, not only for social purposes … but for business’.Footnote 47

In this sense, the anti-corporate ethos of the Populists was shot through with ambiguity. In speeches, Populists such as Peffer, Weaver, and Watson openly denounced corporations as artificial and dangerous entities. This public critique, however, was almost exclusively rhetorical. It was also rarely, if ever, applied to the alliances’ own organizing efforts. Such a combination implied a careful balancing act. Alliance exchanges and other co-operatives, although technically registered as corporations, could not appear as pure business cartels bent on making a profit. Since corporations were ‘soulless’, so the story ran, they were unable to take oaths and were unreliable as agents. The alliances, in turn, were first cast as ‘brotherhoods’ – communities more akin to unions and churches than business syndicates. Initiation into an alliance, for example, was often a ritualized process, with members taking oaths in a ceremonial setting to create a cohesion beyond the simply contractual (which went against the corporation's status as a mere ‘nexus of contracts’Footnote 48). In early years, joining an alliance was also a strictly codified process close to the initiation rites of freemasonry or a church, strengthened by the fact that some Methodist groups provided the bases for rural organizing.Footnote 49

At the same time, alliances and co-operative ventures could not function as purely voluntary associations, chiefly because of their economic function. They remained ‘business organizations’, as Macune had it, and were forced to use the corporate form.Footnote 50 This form included devices such as legal personality, the joint-stock company, delegated appointees, and trusted stewardship. The redeployment of corporate principles that this implied is illustrated by a conversation between a lawyer and a Populist proponent in the late 1880s, reported by Charles Postel:

Mary B. Lesesne of Llano County, Texas, an ardent supporter of the Farmers’ Alliance, had a discussion with a prominent lawyer about the organization's business principles. The lawyer asked her, ‘What is the platform of the Farmers’ Alliances?’ She responded, ‘They are opposed to monopolies.’ To which the lawyer tellingly observed that the Alliances ‘are forming one of the grandest monopolies that the world ever saw.’ Lesesne conceded the charge. ‘It may become a great monopoly’, she replied, ‘but we predict it will use its power wisely.’Footnote 51

Populists also acknowledged that Lesesne's plan was fraught with dangers, mainly when it came to the potential mutual stock-buying or pooling. ‘God forbid that the Farmers’ Alliance should ever be a similar organization to a Trust’, Macune stated in an editorial from the National Economist in 1890. ‘Instead of pooling the wealth of its members, it pools their heads and hearts, their strong right arms, and leaves the property of each undisturbed.’Footnote 52

Macune here referred to the fact that alliances themselves did not force members to commit productive property into the hands of alliance delegates – the co-operative farmer owned his or her lands or continued to lease them from merchants or planters. It thereby sought to prevent the socialization of property in the corporate stockholder, in which ownership (dominium) and control (imperium) were separated, and the republican connection between property and independence was destabilized. Macune's reading of incorporation thus required a careful reframing of its conventional role. As Jeffrey Sklansky noted, Macune's Populism sought to ‘seize the reins of the new corporate order not just by reorganizing the business of farming’, but also ‘by modelling a different kind of large-scale commercial enterprise … when the basic structure of corporate consolidation appeared up for grabs’.Footnote 53 In Macune's view, the popular intermediary of the alliance could resist and eventually marginalize the new corporate ‘octopus’.

In a previous, anti-corporate sense, the co-operative's set-up also had to be cartel-like and monopolistic. Macune wrote in the National Economist that ‘Organization could render farming profitable by the introduction of better business methods, in which all would unite and cooperate for the purpose of selling our products higher, and purchasing such commodities as we are compelled to buy, cheaper.’Footnote 54 As Macune's colleague Julius Wayland put it, ‘every monopoly [had] to be met with a counter-monopoly of the people’, in which the Populists’ ‘good monopolies’ would be the ‘outgrowth of a beautiful principle of combination’.Footnote 55 Macune and Wayland's vision of ‘combination’ was therefore far from an individualist idyll. Rather than harking back to a nostalgic vision of independent homesteaders, they supported scaling up production and ‘believed that bigger was better’.Footnote 56

Nugent, Macune, and Watson were only some of the Populist theorists who registered the shift that the corporation caused in late nineteenth-century republican thinking. Most of all, Populism's engagement with ‘combination’ implied a departure from the latter's settler individualism, which had hoped to organize farming without larger intermediaries. Yet it was ‘idle’, the Populist writer Estelle Bachman claimed in the 1890s, ‘to inveigh against cooperation, as if it did not already exist … only the hermit or the most primitive savage is or can be an absolute individualist, economically speaking’ and ‘human life … was possible only by incorporation and cooperation with society as a whole’.Footnote 57 In 1894, the North Carolina Populist Marion Butler similarly proclaimed that ‘we have reached that point in our civilization, even under a republican form of government, where organization is not only beneficial, but also necessary’.Footnote 58

This ambition had an evident practical counterpart. In the 1880s, Macune's organizations began lobbying state legislatures to issue new charters and allow for lower capitalization rates for their joint-stock companies. Across southern states, for instance, these capitalization rates were usually set at a stark $25,000, which set steep requirements for those eager to enter the corporate terrain. Macune's first exchange was capitalized at $20,000, with each alliance member contributing a $2 ‘exchange assessment’.Footnote 59 In Dakota, the Territorial Alliance was similarly incorporated as a joint-stock company, while several Colored farmers’ alliances applied for corporate charters throughout the decade.Footnote 60 In Alabama, the alliance even became the only corporation whose shareholders were ‘limited to the members of an oath-bound association’, shutting out lawyers, corporate employees, and bankers.Footnote 61 Organizationally, Populist action yielded promising results: by early 1887, alliances counted a total of 200,000 farmers among their ranks; by 1892, Black Populist organizations were estimated to have no fewer than 1.2 million members and White equivalents an impressive 3 million.Footnote 62

Macune's co-operative tactic also quickly revealed its limits, however. First, it did not account for the overwhelming hostility that corporate actors would soon show towards producers involved in the alliance experiment. Many farmers’ alliance members were blacklisted by train companies and banks and faced discriminatory rates when restocking supplies.Footnote 63 Another problem concerned the co-operatives’ lower capitalization rates, which shortened their lifespan as bodies and strained relationships with banks. As Macune reported to his Texas Alliance as early as 1888, all the exchange's attempts at securing bank loans ‘were unsuccessful’ and brought ‘the conviction that those who controlled the moneyed institutions’ of the state ‘did not choose to do business with us’.Footnote 64 Macune had started by exploiting the possibilities of the new general incorporation regime, using his co-operative ventures as corporations ‘turned inside-out’. Once the existing corporate actors showed themselves too strong, more ambitious state action had to be explored.

IV

Macune decided to change strategy vis-à-vis the state. At a December 1889 convention in St Louis, he informed his audience that it ‘was time to pressure the federal government to pass legislation to address the current crisis’.Footnote 65 Macune's shift was not only premised on the failure of the intermediary path. It also ran parallel with his changing explanation for agricultural decline. In his view, the alliance system had failed to strike at the real root of the agrarian crisis, focusing too one-sidedly on questions of transportation and storage and neglecting private control over the money supply. He argued that ‘low crop prices and economic hard times’ were not solely the result of monopolies in communication and information, but also the inevitable outcome of an ‘insufficient national supply of money’.Footnote 66 This option demanded pressure on states to seize local monetary hubs (local banks, most of all) that had to begin issuing currency themselves. It also meant installing oneself on a state level, a possibility of which Macune had remained wary of before. In an 1889 entry in his magazine, he inched towards a replacement of the co-operative system with state-tended warehouses, still typifying the former as ‘temporary’, but keeping the gate open for further reform, mainly in the monetary area.Footnote 67 The plan was to distinguish itself from the shepherding of capital into the hands of the state, an option which had gained currency on Populism's left flank. As Macune had noted in April 1889:

[T]he farmers’ and labor organizations are temporary combinations for self-protection and should not be regarded as permanent combinations based upon, and calculated to carry out, the principles of socialism. This is why the Alliance is not a monopoly. Still, it and like organizations must continue to exist till government shall so faithfully perform its functions as to make their operations no longer necessary or desirable.Footnote 68

Attempts to crowd out corporations through co-operative action had been revealed as insufficient: the farmer's ‘benevolent trusts’, as Victoria Woeste has called them, were no match for the actual malevolent ones.Footnote 69 Macune concluded that alliances could not merely imitate the trusts as rival intermediaries but should seek their own alliances with the state, which Populists had so desperately shunned before. ‘Let the government’, he argued in the early 1890s, ‘be the embodiment of all the combined action society finds necessary by saying that all kinds of business or effort susceptible of being monopolized shall be conducted by the whole society and not by a favored few.’Footnote 70 Rather than seeking to crush corporations through a strong executive, Populism's aim was to deploy a capacious state to level the playing field for co-operatives and thereby foster rural organization across society.

Macune's most ambitious response to failure of the exchange system was a proposal that also worked as a catalyst for third-party formation: the sub-treasury loan system. The scheme's design was as simple as it was radical. It would allow farmers to store grain in times of market glut and take low-interest loans to purchase inexpensive farming equipment, while receiving vouchers which denoted the value of the crop and other commodities deposited by the farmers in state-tended warehouses. The plan was first put forward by Macune and the North Carolina Populist Harry Skinner, and its proponents again took themselves to be constructing a ‘counter-monopoly of the people’ against corporate monopolies in transportation and currency, but now explicitly with the help of state action.Footnote 71 It would have to be enacted on a federal level (through congressional action, overall), although counties would control local implementation. As Macune argued:

That the system of using certain banks as United States depositories be abolished, and in place of said system … it should be the duty of such sub-treasury department to receive such agricultural products as are offered for storage and make a careful examination of such products and class same as to quality and give a certificate of the deposit showing the amount and quality.Footnote 72

Macune's sub-treasury had a rich historical pedigree. Historians have traced his proposal back to Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's 1848 plans for a ‘people's bank’ and the American political economist Edward Kellogg's 1849 scheme for a government-issued fiat currency (Macune himself was an admirer of Proudhon's ‘scientific anarchy’ and circulated several of Kellogg's tracts in his magazine in the 1880s).Footnote 73 The first American study of Proudhon's work – Charles A. Dana's Proudhon and his ‘bank of the people’ – appeared in 1849, followed by William B. Greene's translations of the ‘Organisation du crédit’ in 1850.Footnote 74 Macune most likely encountered Proudhon's writings in the late 1870s, circulating in a Greenbacker orbit and the political economy of Henry Carey.

Macune's attraction to the two theorists was unsurprising. Both Kellogg and Proudhon were preoccupied with the question of how ‘industrial servitude’ could be averted in a world of intensified commerce, and Macune shared their concerns about the impossibility of what Proudhon called ‘direct exchange’ between producers in growing market societies.Footnote 75 In the late 1880s, Macune's National Economist diagnosed that Texan farmers no longer had a direct link to their consumers. Instead, they ‘sold to the carriers, the carriers sold to the manufacturers or processers, and they sold to the consumer’. This long chain of intermediate stages meant that nearly ‘three times as much money as the old system’ was required for farmers.Footnote 76 If a financial class was able to curtail the money supply, however, and keep it in a state of artificial scarcity, agricultural prices would drop and credit would become scarce. Macune's response was that the state itself would adapt to the imperatives of co-operation and level the playing field through state action. His initiative tracked a broader Populist movement onto state levels. ‘When capitalists combine irresistibly against the people,’ Henry Demarest Lloyd announced in 1894, ‘the people, the government, which is the people's combination, must take them in hand.’Footnote 77

In May 1892, however, the sub-treasury stalled in its congressional committee and went into a ‘long legislative sleep’.Footnote 78 Democratic resistance to the plan had spurred the first calls for third-party formation in 1889.Footnote 79 Macune himself refused to follow the alliance into the People's Party, being worried about his base's Democratic leanings.Footnote 80 Instead, he promptly switched to a more modest cotton-marketing programme.

Others, however, followed up on his plan while investigating additional avenues for anti-corporate politics. This expansion had always been a vexatious issue. Given their attachment to an older Jeffersonian anti-federalism, wariness for big government and love of localism remained rhetorical traits of the Populist project. This was most visible in Populists’ distaste for executive state power. Leaders such as Macune, Watson, and Weaver preferred a ‘government of laws’ over a ‘government of men’, in which the people could be actively represented on a state level, yet without that government (mostly federal, in Southern cases) undertaking economic management.Footnote 81 However, Populists’ endorsement of the sub-treasury system indicated that they now sought out active federal interventionism. ‘All this racket about paternalism’, an Alabama Populist declared in 1892, ‘is bosh.’ All government-supported enterprises were ‘necessary, advantageous and beneficial, and have not and will not destroy the government; but make it better, stronger and more advantageous to the people who pay taxes to support it’.Footnote 82

This strengthening of the state could not take place by distancing governments from popular power, however, which was a republican sine qua non. The American government was already well suited for this purpose. A Texas Populist journal proclaimed: ‘We … recognize the fact that the government is not something separate from the people but, when properly administered, is simply the people governing themselves.’Footnote 83 James H. Davis used a similar understanding of state power in his 1894 book A political revelation, which sought to sell Populist proposals to a sceptical voting public. He stated, ‘let us agree that the government of the United States is not a separate thing from the people, geared up and held in the hands of a royal family or aristocracy’; rather, ‘the people … constitute their royal family’, and ‘every man is just as much a sovereign … as any other man’.Footnote 84

This task was easier said than done. Populists not only faced opposition from conservative writers on their plans for an ‘octopus state’, which recalled Norris's vision of corporate corpulence. These critics claimed that transferring economic sovereignty back from corporations to states would simply mean the creation of a ‘damnable Democracy … like an octopus with a million tentacles’.Footnote 85 Similar complaints were also voiced in radical quarters. The trade unionist Arthur H. Dodge of the San Francisco Typographical Union, for instance, opened his 1894 tract Socialist-populist errors with the admonition that ‘complete centralization of all activities of society will … render the working classes more dependent’, and ‘make it more and more impossible for the workingmen to control their own conditions’.Footnote 86

Populists’ reply to this charge was that their state would simply respond to the centralization that had already taken place in corporate sectors. As an anonymous Populist author put it in 1891, ‘those who express so much horror in the paternalism involved in the proposition of government ownership of the means of transportation and communication’ in turn had ‘no fears of the centralization of power in the hands of a few irresponsible men resulting from corporate control of the same franchises’.Footnote 87 Populism's mission, therefore, was not to thwart the centralizing power of states, mainly in their legislative branch, but to assure that they reclaimed the sovereignty they had ceded to private entities.

Elizabeth Sanders has sharpened this argument for centralization by showing how Populists sought to deflect criticism that their plans constituted unwarranted expansions of state power by relying on a language of exclusively legislative reform. The Populist project, as she notes, implied a ‘statutory’ rather than a ‘discretionary’ state, in which legislatures would remain the most powerful entities.Footnote 88 Legislatures would write statutes which would allow farmers to take specific action against corporations, rather than handing control to administrators. This option meant focusing on the role of states and Congress in both revoking and reshaping corporate organizations and reclaiming their legislative might.

This preference for a parliamentary road to reform was expressed across the Populist literature throughout the 1880s and 1890s. The Populist newspaper The Arena noted: ‘It is lamentable to contemplate the extent to which the average Congressman has declined from the standard of his predecessors … the old representative glory.’Footnote 89 Other Populists expressed their preference for a British parliamentary set-up, in which a unicameral legislature could rule without constitutional restrictions.Footnote 90 Similarly, Congress was seen as the ‘most dignified body of law-makers on earth’, despite its current status as a ‘disgrace to the Republic’.Footnote 91 At the same time, Populists resisted attempts to curtail corporate excess through regulatory commissions (exemplified by the case of the 1887 Interstate Commerce Act), which they thought would be filled with the same corporate lawyers they had warred against before.

Populist wariness towards discretionary state power was most openly voiced in the debate surrounding the very same Interstate Commerce Act, which passed before Macune's work on the sub-treasury proposal. The act constituted a high point of late nineteenth-century anti-trust politics. It was framed as a remedy for the railroads’ discrimination against farmers who sought short-haul transportation for crops. Instead of the long-haul corporate commerce favoured by railroads, Populist legislators hoped to implement a more regional vision that tied farmers to international markets without interference from corporate middlemen.Footnote 92

A prominent target for Populists again was a close relationship between governments and corporations. The Texas congressman John Reagan – like Macune, an early ally of the alliances, but later an opponent of the People's Party – argued in a congressional debate in 1882 that, if corporations were

allowed thus to go on unrestrained and uncontrolled, and if Congress shall continue to disregard the rights and interests of the people through either imbecility, corruption, or the fear of offending the managers of these corporations, how long will it be until they complete mastery of our … material interests of our governments?Footnote 93

In contrast to an expert commission presiding over anti-trust policy (which was finally legislated into existence in the Interstate Commerce Commission), Reagan preferred to stipulate on a purely legislative basis ‘what shall be done and what shall not be done’. He stated: ‘We do not propose to do anything in this Congress which requires … the assistance of any railroad expert.’Footnote 94 Even if a commission had to be ‘clothed with limited discretion’, Reagan thought that the ‘American people … [were] not accustomed to the administration of the civil law through bureau orders’, claiming that ‘this system belongs in fact to despotic governments’ and ‘not to free republics’.Footnote 95 This sentiment was later echoed in the 1892 Omaha Platform's declaration that America's ‘government service’ was to be ‘placed under a civil-service regulation of the most rigid character, so as to prevent the increase of the power of the national administration’.Footnote 96

What was a valid anti-trust alternative? Here, Reagan preferred deliberation on trusts in legislatures, who would subsequently codify into law. This would allow farmers to bring suits against corporate actors in local and state courts based on strict statute, rather than handing power over to a price-setting agency. (Interestingly, this option also accepted the fait accompli of corporate personality in the prosecution of railroads qua persons, and not as mere aggregations of individuals.) As Reagan warned, railroads’ vast resources would allow them ‘to control the best legal and business talent of the country, and … enable them to procure influential men in their interest’. He concluded that railroad regulation was a task that lay wholly within the remit of legislatures, not executive agencies – a vision of a statutory, not discretionary, state in which Congress was the prime ‘commission created by the people for the enactment of laws’.Footnote 97

In the course of the 1890s, these Populist calls for a statutory state were increasingly coupled with more open support for plebiscitary measures. These included 1892 pleas for referendums, popular initiative, and a direct election of federal judges and senators.Footnote 98 As historians of Populism have repeatedly stressed, however, these proposals sit uneasily with the wider strain of Populist thought. Mainstream Populists thought that, given the failure of their intermediary effort, the creation of their ‘co-operative commonwealth’ had to pass through legislative routes. This was also visible in Populist leaders’ disapproval of direct action such as the Coxey's Army marches of 1894. In this sense, they looked on initiatives and referendums as last-ditch efforts to safeguard a programme.Footnote 99

Populist theorists thus expounded a vision of association and state centralization that remained thoroughly ‘pluralist’ and open to voluntary association by contemporary standards. They embraced parliamentary representation, recognized the need for bureaucratic expansion, and affirmed the basic tripartite structure of American government. Although Populists did advocate the democratization of some federal organs (visible, for example, in their 1890s proposals to make Supreme Court judges subject to popular recall) and occasionally toyed with notions of unicameral governance, they never questioned the legitimacy of checks and balances itself. This reticence became most visible in their preference for legislatures as the ultimate sites for popular power. Rather than seeking to curtail those legislatures in favour of personalistic leadership, Populists believed that parliaments needed to regain the sovereignty they had ceded to private actors. In this way, as Gerald Berk notes, ‘smallholders were to be supported by a regime of cooperation’ and ‘not by a self-regulating market’ as in the Jacksonian era.Footnote 100 On the level of both association and state formation, therefore, Populism defies the current typology.

V

Populism's intellectual contest with the corporation ran parallel to the unstable party politics of the 1890s. In the opening years of the decade, American history seemed to be moving in a Populist direction: James B. Weaver achieved a respectable 14 per cent in the 1892 presidential election, and Populists captured a sizeable number of seats in western and southern states in 1894. In the South, however, Democratic Party elites fought Populist insurgency with physical intimidation and stuffed ballot boxes. In desperation, Populists started looking for help within the established parties themselves. In 1896, the Democratic Party co-opted the Populists’ platform by nominating the bimetallist William Jennings Bryan as a proponent of a moderately inflationary policy. After bitter debate, the Populists decided to accept Bryan's name on their own ticket. Bryan lost the subsequent election, and by 1897 the People's Party's members were moving across the spectrum. With them went the last hopes of enacting the 1892 anti-trust and sub-treasury plans in original form.

However, 1896 did not herald the end of the ‘Populist vision’. The organizational efforts of the farmers’ alliances continued to weigh on the legislative activity in the Progressive era, with farmer radicals making up constituencies for the 1913 Federal Reserve Act, the 1914 Clayton Antitrust Act, and the 1914 Federal Trade Commission Act.Footnote 101 In all these cases, echoes of the Populist movement set out contours for state action and informed policy-making. Nonetheless, the ambitious scope of the original co-operative effort and reform programme faded away. While Populist politicians continued to hold office (such as the Kansas chief justice Frank Doster and Senator Marion Butler), the fierce anti-corporate energy of the 1880s and 1890s fizzled out, giving way to more top-down variants of agrarian reform.

Two cautionary notes on the status of Populist theory are in place here. First, the assessment offered in this article should not lead us to overlook anti-intermediary tenets in original Populist thinking. Populist objections to corporate personality often betrayed a certain naturalist nostalgia, in which the prime ‘rights-and-duties-bearing units’ of a polity would remain natural citizens (possessing, preferably, landed independence) and intermediary bodies would cease to be necessary altogether. This naturalism, however, does not do full justice to their theory or political programme, or to how both advocated the usage of intermediaries such as co-operatives and, later, political parties.

Secondly, a focus on co-operatives should not obscure the prevalence of other units within Populism's collection of organizations, or the occasionally exclusive characteristics of these organizations themselves. Temperance societies, Methodist churches, land-grant colleges, and state parties were equal partners of the Populist coalition and demonstrated the depths of its organizing effort.Footnote 102 The co-operative effort was also lost on members of the Populist coalition subject to forms of market dependence different from its tenant or yeoman constituency, such as (predominantly African American) sharecroppers or new rural waged workers, who inhabited a different alliance culture altogether.

Nonetheless, these findings might encourage reflection among current theorists of populism. More often than not, pro-populist accounts have insisted on the need for every populism to solidify itself in the figure of a leader, often placed in an executive position, rather than through the slow and steady formation of interest in intermediary bodies and parliaments.Footnote 103 Jan-Werner Müller's work stands out by its admission that late nineteenth-century American Populism does not conform to the criteria set out for his contemporary ‘small-p’ variant.Footnote 104 Müller's problem is also visible in Ernesto Laclau's rejection of ‘intermediary bodies’ as a necessary part of a populist moment. As Benjamin Arditi notes, Laclau's ‘left-populism’ offers a mode of political representation of ‘virtual immediacy’ in which an ‘imaginary identification … suspends the distance between the people and their representatives’.Footnote 105 Since the populist ‘people’ cannot conceive its identity or interests before a representative claim is posited, intermediary bodies will invariably vaporize in the face of the populist coalition, while parliaments will remain unsuitable conduits for its types of popular action. Perhaps unsurprisingly, left-populist theorists such as Laclau and Chantal Mouffe are happy to combat liberal critics on their own terrain and accept populism's opposition to intermediary institutions.

The factual foundations for this claim, however, are not always as clear-cut. This problem becomes most acute in Laclau's own treatment of the late nineteenth-century Populist movement in On populist reason (2005). Laclau claims that the People's Party's 1896 campaign was ‘the culmination of a long process going back to the Farmers’ Alliance of the 1870s’, in which ‘several mobilizations and co-operative projects had been initiated’, yet ‘without any lasting success’. Only when William Jennings Bryan – the 1896 presidential candidate on the ‘Demo-Pop’ ticket – was able to unite this string of demands into a ‘chain of equivalence’ was a coherent coalition constructed and Populism achieved ‘paradigmatic value’. By achieving an identity between ‘leader’ and ‘people’ – here realized in the figure of Bryan – Populists could finally build their own version of the ‘people’.Footnote 106

Seen within the milieu of the late nineteenth century, Laclau's account overlooks a large part of the Populist story. Rather than a diffuse set of actors looking for guidance, Populism achieved organizational consistency long before the arrival of Bryan as its nominal leader. Indeed, it was only through the usage of intermediary bodies such as co-operatives, parties, and brotherhoods that a coherent notion of a populist ‘people’ was able to crystallize and Populists became aware of their interests as agricultural producers. Such consciousness-raising happened when Macune's exchanges applied for corporate charters from state governments. Pace Laclau and Urbinati, then, it was only because of the weakening of the coalition in the face of Democratic intimidation and voter fraud that the Populists turned to a presidential unifier in Bryan.Footnote 107

The Populists of the nineteenth century thereby stand in interesting tension with the portrait painted by today's populist theory. While openly Tocquevillian in their preference for voluntary association, Populists did not end as anti-statist romantics. Instead, they were open about their preference for strong governments, mainly in matters of economic redistribution and credit provision, although usually confined to parliamentary contexts. This feature might put them at odds both with liberal pluralists, who prefer associations for their capacity for civic education or elite formation, and with later syndicalist and communist currents, which sought to replace parliaments with more ‘authentic’ units of decision-making such as councils, parties, or unions.Footnote 108 What becomes equally clear from this account is that a Populist distaste for ‘malevolent’ intermediaries was balanced by a preference for empowering ‘benevolent’ intermediaries: a plea for ‘indirect democracy’, albeit with strong provisos on how such ‘indirectness’ was to be organized.

This article has offered a distinctly different portrait of Populism from the one painted by contemporary writers and historians. In historiography, this portrait can allow scholars to think harder about the difference between Populism and pro-corporate models put forward by liberal thinkers, moving beyond mere responses to feasibility constraints or organizational imitation. As shown, Populists sought more than assimilation in the corporate economy while eagerly deploying its devices. None of these arguments should force scholars to regard Populism as either a theoretical oracle or an activist exemplar. Rather, a nuanced, historically grounded understanding of the original nineteenth-century Populists might readjust the lens of our current populism debates and our historiographical conversations, pushing theorists to reconsider whether all populisms glorify immediacy, loathe intermediary bodies, and venerate direct democracy.