The estuaries of India’s Malabar Coast served as a backdrop for repeated meetings of products and peoples in antiquity, but the exchange of Roman gold coins for Malabar peppercorns was by far the most divisive. Our most detailed textual source regarding ancient trading activities on the Indian Ocean, a first-century ‘handbook’ written in Greek known as the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, mechanically outlines the exchange of Roman coins for black pepper at Malabar ports such as Muziris; yet most contemporary testimonies provide more polarized views.Footnote 1 A poet of the Tamil Caṅkam corpus celebrates the arrival of western traders (yavaṉar) at Muziris (Muciri), who bring gold and depart with pepper in return.Footnote 2 A world away in Rome, the first-century encyclopedist Pliny the Elder bemoans the loss of Roman capital to the East as a result of the spice trade throughout his Natural History, putting forth a questionable deficit figure of 100 million sesterces per annum (with half going to India alone).Footnote 3 The underlying transaction of specie for spice has long stood as a proxy for a wider web of overland and maritime connections between the Mediterranean world and the Indian subcontinent, which scholarly treatments have traditionally labelled ‘Indo-Roman’ trade.

These vignettes betray a fundamental complexity to the study of long-distance trade in antiquity. The larger story of the exchange of gold for pepper must rely on a confluence of evidence drawing from different traditions of the ancient world. Historically, however, the scholarship on this topic has prioritized agenda over evidence. The earliest work on the trade, conducted primarily by British scholars during the Raj, concluded that Rome ruled the waves in antiquity and established trading posts throughout an economically primitive subcontinent to secure luxuries for imperial consumers—a facsimile of empire articulated as Britain’s own waned.Footnote 4 Post-colonial scholarship, reaching an apex after Indian independence, swung the pendulum toward nationalist interpretations: ancient India now served as the centre of commerce in an Afro-Asian world, with the Romans buckling under their supposed trade deficit.Footnote 5 Despite the new discoveries of archaeological, papyrological, and epigraphic evidence over the last three decades,Footnote 6 and the emergence of the Indian Ocean as an area study in the longue durée,Footnote 7 the historical construct of ‘Indo-Roman’ trade for the early first millennium CE has endured, a cleft in perspective which began in antiquity and persists through partisanship. While scholars have attempted to bridge the cultural and scholarly divides plaguing later periods of historical inquiry, only recently have they begun to employ more nuanced theoretical models to better understand the interconnected Indian Ocean in antiquity (a trend discussed further in Matthew Cobb’s introduction to this Special Issue (henceforth SI)).Footnote 8

What goes on behind this curtain of source material and scholarly interpretations? What is the human toll behind a sprinkle of pepper or a gift of gold? The agents of pre-modern commerce operated in the face of several unknown factors when moving gold or pepper across thousands of kilometres.Footnote 9 It was certainly a risky business for both investors and traders: investors bore the financial burden of cargoes lost at sea, while traders onboard could well lose their lives. A rather obvious limitation were the seasonal monsoon winds on which Indian Ocean sailors relied—winds that only enabled ‘contingent movement’ by sail in one direction for months at a time.Footnote 10 As a result, foreign traders had to wait for the winds before embarking on their return journeys across the sea. Besides ocean currents, mercantile agents had to navigate the numerous economic and legal institutions throughout the Indian Ocean world, which, when done correctly, could dramatically lower the costs of their commercial activities. Such considerations are of immense importance for determining the strategies that reduced the risks of maritime travel, facilitated long-distance business transactions, and ultimately made this trade possible.

The sporadic evidence for ancient Indian Ocean trade—ranging from graffiti and archaeobotanical remains to the normative precepts of legal texts, from Greek and Latin sources to those composed in several Indic languages—becomes quite compatible within a broader comparative model based on the human strategies of commerce. Mercantile agents in pre-industrial economies often faced similar considerations and institutional factors when organizing maritime ventures over such vast distances. They shared the same elemental concern when pursuing profit: how to conduct transoceanic commerce in the most expedient, safe, and cost-effective way possible. A broader approach clarifies our understanding beyond those from either side of the scholarly divide, both of which often seek to define political stakes over an ocean no ancient state controlled. In the oceanic in-between, where the monsoon winds held sway, traders from the eastern Mediterranean, Near East, and Indian subcontinent crossed the sea not to plant the flag, but to pursue opportunity.Footnote 11

We can think of this model in terms of the ‘players’ and the ‘game’ of oceanic trade, borrowing a metaphor from New Institutional Economics (see below). Distance, topography, technological limitations, state interference, and institutional factors shape the ‘game’ of Indian Ocean commerce with a set of rules governing fair and profitable play. These parameters helped shape the strategies used by ‘players’, our human agents (and, to a limited extent, state actors), who cooperated to maximize their chances of profit, exploited loopholes, or, when opportune, cheated. A model such as this cannot reveal exactly how every trading operation on the Indian Ocean occurred in antiquity; rather, this deductive model allows us to propose with comparatively few sources of evidence a coherent system of practices that ancient merchants likely employed on the Indian Ocean—a system that is resilient enough to incorporate further discoveries without recourse to debates steeped in cultural competition.

This article explores the strategies of those playing the game of Indian Ocean trade in the early centuries of the Common Era. After a brief survey of some of the players involved, the larger institutional factors that governed economic activity in the Mediterranean and Indian subcontinent will be discussed; such factors, particularly those pertaining to organization and financing, informed the way the ‘game’ was played by private commercial agents. States, though players of the game in as much as they sought to acquire revenue from indirect taxes, also shaped the game, whether deliberately or unconsciously, through top-down initiatives. The following section highlights some of the operational strategies that could lower the transaction costs of maritime ventures, namely how the players could play the game well. Such strategies include diaspora communities built around a shared cultural identity, communication and information sharing, physical outposts sustained through food importation, integration into local support networks, and exploitation of state incentives. By articulating the shared rules of the game and its players, this article offers a new approach beyond the confines of the divisive label ‘Indo-Roman’ and argues that it was a broader set of human choices that enabled the viability of long-distance trade between the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean worlds.

The players: ancient Indian Ocean traders

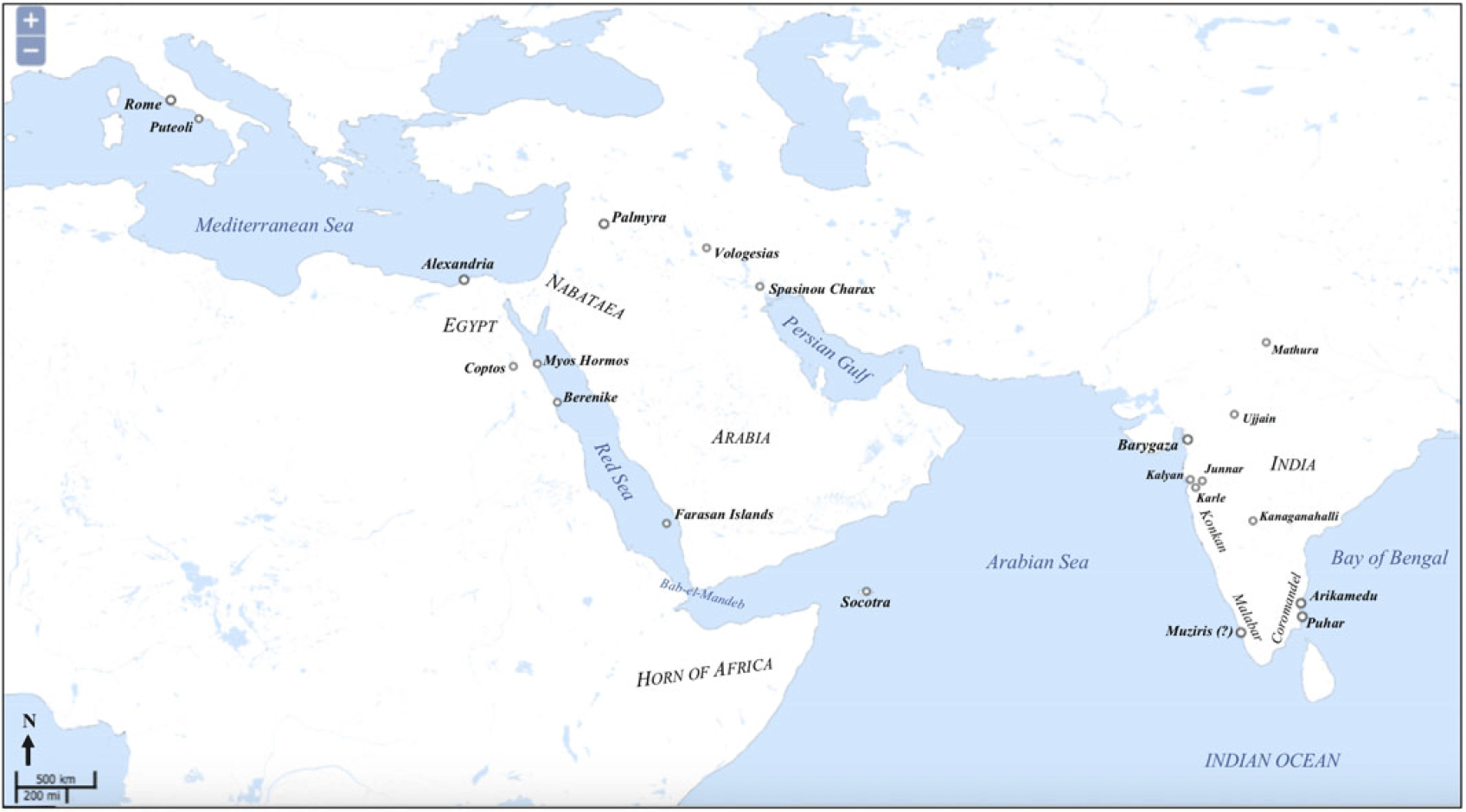

In addressing the primary players of ancient ‘Indo-Mediterranean’ trade, this article focuses on three specific groups: Indian traders in Roman Egypt; Mediterranean traders in India; and the multiethnic community on the island of Socotra. Where illustrative, better-attested communities involved in ancient long-distance commerce, such as those of the Nabateans and Palmyrenes, will also be discussed. The evidence moves rapidly between different geographies, materials, and languages but, when viewed in total, serves as an useful corpus from which we can better understand ancient oceanic trade (see Map 1).

Map 1. Ancient Indian Ocean World (early first millennium CE) [Map: Simmons, AWMC].

Until recently, traders from the Indian subcontinent were thought to have had a limited footprint in the Mediterranean world: as Cobb argues in his contribution to this SI, such an understanding must be reworked. While the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea and numerous ancient Indian texts describe transoceanic crossings by Indian merchants,Footnote 12 corresponding archaeological evidence first came to light through excavations at the Egyptian ports of Berenike and Myos Hormos.Footnote 13 Graffiti evidence found on local pottery at these ports reveal Tamil names, such as Kaṇaṉ, Cātaṉ, and a chieftain Korran (Korra pūmān).Footnote 14 A more extensive Prakrit graffito from Myos Hormos records the provisions of three traders from the Deccan Plateau in India, Hālaka, Viṇhudata, and Nākadata; the brief document contains each trader’s store of perishable goods for consumption while abroad (e.g. meat, oil, and wine).Footnote 15 When combined with finds of Indian cooking ware and fineware along the routes through the Eastern Desert as far as Coptos, and fragments of Indian woven mats and baskets discarded at Berenike, these graffiti give the strong impression that Indian traders resided in Egyptian ports at least seasonally.Footnote 16

For Mediterranean maritime ventures to India, we have various Greek and Latin textual references, as well as epigraphic attestations from the Syrian city of Palmyra (see below); we also have a single contract and cargo list preserved on the ‘Muziris Papyrus,’ which outlines the financing and transportation of a large cargo acquired at Muziris—the Malabar port celebrated in the Caṅkam corpus and loathed by Pliny—from the port of Berenike to the city of Alexandria in Roman Egypt.Footnote 17 Indic sources mention the trading activities of seafaring ‘westerners’, identified by the Sanskrit and Tamil term yavana. Footnote 18 Tamil poetic sources describe a large and lavish yavana enclave in a select quarter of the Coromandel port of Puhar.Footnote 19 Indic texts similarly treat the port of Muziris, which hosts the iconic exchange between gold-bearing yavanas and pepper-rich Tamils in the Caṅkam corpus.Footnote 20 The recipient of the loan outlined in the Muziris Papyrus, likely the owner of a ship transporting numerous south Asian commodities, would have been one of these yavanas forced to remain seasonally at Muziris.Footnote 21 The presence of Roman utilitarian pottery and personal items like gaming pieces in southern ports, including ArikameduFootnote 22 and most recently PattanamFootnote 23—a site very tenuously linked with the Muziris of ancient sources—all point to not only the conduct of trade, but also the habitation of these locales by small populations of Mediterranean merchants.

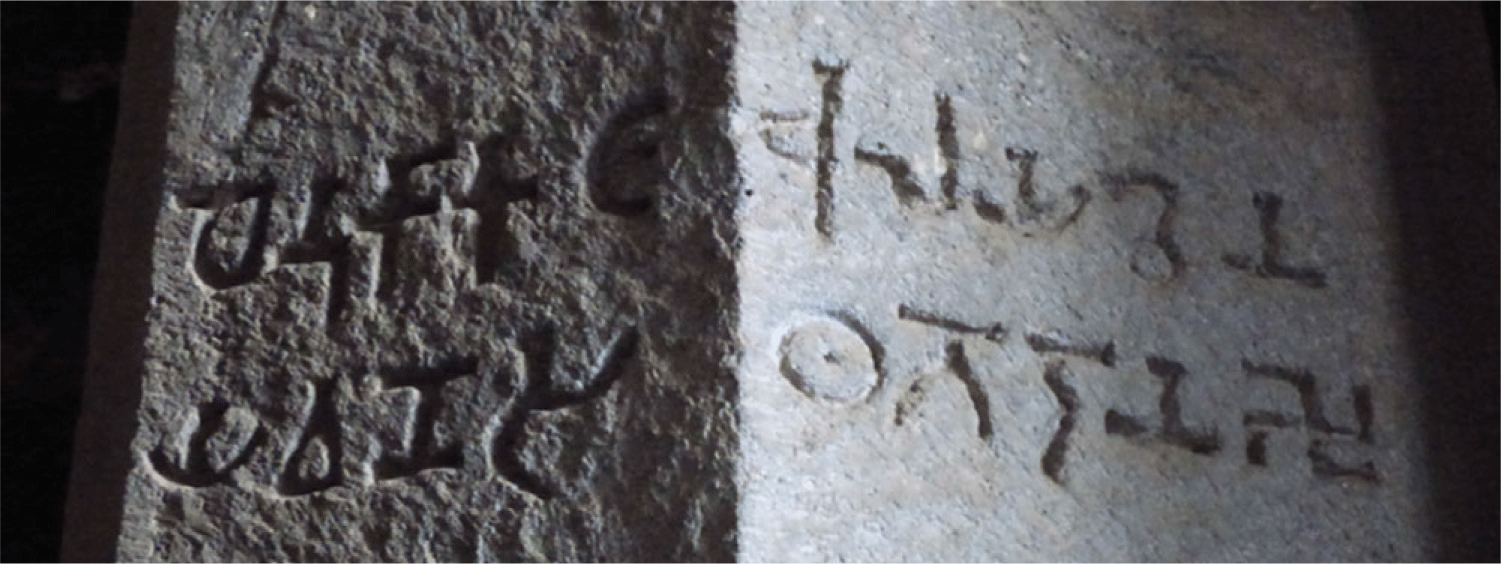

We can also look to several Prakrit dedicatory inscriptions made by yavanas at Buddhist sites in the western Deccan region of India.Footnote 24 The majority of these yavana inscriptions, dated to the first or second century, appear at the sites of Karle and Junnar, with many of the foreign dedicators hailing from the nearby town of Dhenukākaṭa.Footnote 25 While all of the inscriptions are marked with the foreign epithet yavana, many identify members of larger groups, such as ‘Yavana of the Dhamadhayas’ or ‘of the Chulayakhas’, and, in few cases, offer proper names (e.g. Cita, Irila, and Caṃda).Footnote 26 These inscriptions represent larger corporate or familial groups of settled diaspora communities in India and, in addition, mark a way in which foreigners interacted with local support networks, a strategy to which we will return in the following section. Traces of yavanas have been found deeper within the subcontinent as well: the yavana Nandi made a dedication in the northern city of Mathura at roughly the same time as those at Karle and Junnar; Footnote 27 a fragmentary inscription at the Buddhist stūpa at Kanaganahalli mentions a certain ‘Makosama’, which some have cautiously linked to the Roman name Maximus;Footnote 28 a Sanskrit causerie of the fifth century describes the diverse population of the city of Ujjain, among whose denizens numbered yavanas;Footnote 29 and clay sealings ‘of yavana women’ (yavanikanam) have been recovered from Ujjain and Mathura.Footnote 30 The presence of Mediterranean traders in the subcontinent was not merely a coastal affair.

Finally, we can address the island of Socotra, or ancient Dioscourides, which lies in the Arabian Sea just off the Horn of Africa. Testimony from the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea indicates that there was a mixed population of Arabians, Indians, and even some Greeks on the island,Footnote 31 a description that has been confirmed by the recently published Hoq cave inscriptions.Footnote 32 The majority of the graffiti in the cave, written in Prakrit, provides names for dozens of commercial actors arriving from western Indian emporia such as Bharukaccha (Barygaza in Greco-Roman sources), modern Bharuch in Gujarat.Footnote 33 As Cobb has also noted in this SI, onomastic studies of the inscriptions have revealed a diverse group from throughout the subcontinent, and further testimony left by Arabian, Greek, and Palmyrene visitors confirms the site’s multicultural character.Footnote 34 Though limited in quantity and scattered over thousands of kilometres, the evidence surveyed here provides glimpses of a myriad of commercial relationships spanning the ocean in the early centuries of the Common Era.

The game: states, institutions, and organization

Behind this scatter of evidence, we can begin to see the economic institutions underlying long-distance ventures, especially if we keep New Institutional Economic theory (and its successful application to ancient economies) in mind.Footnote 35 Endogenous institutions within given societies (whether formal or informal) and the path dependence they inspire aim in principal to lower transaction costs, or the costs associated with executing business transactions in an informed way. In a world full of unknowns, with capital and life on the line, a human calculus emerges to encourage efficiency while minimizing potential risks for all parties involved. Douglass North, a founding father of this school of economic thinking, sees institutions as providing ‘structure’ and the ‘rules of the game’; in adopting such a way of thinking, this article identifies just how the game of Indo-Mediterranean trade was played, starting first with how the aforementioned actors organized themselves to greatest effect.Footnote 36

Two forms of private organization can be gleaned from ancient source material throughout the Indian Ocean world, the first being the so-called ‘principal-agent’ relationship. In this form of organization, principals delegated resources for use by subordinate agents, who, being either contractually or socially obligated to the principal, represented his or her financial interests at a distance.Footnote 37 In the Roman world, principals were often wealthy Roman citizens looking to diversify their portfolios beyond landed wealth, with agents ranging from hired hands to slaves and freedmen who were intimately tied to their (ex)masters through the social conventions of status and systems of oppression.Footnote 38 Accordingly, we find several freedmen and slaves operating in Egypt on behalf of wealthy Roman families (i.e. principals), such as the Annii, Numidii, and Peticii, in documentary and epigraphic sources of the first century CE.Footnote 39 Our most detailed example is preserved in the contract on the recto of the Muziris Papyrus, wherein an unnamed paralēmptēs—an official in the tax-collecting apparatus in Egypt, i.e. the principal—forwards capital to an agent, who agrees to arrange the transport of a cargo of goods acquired at the Malabar port of Muziris from Berenike in Egypt, through the Eastern Desert to Coptos, and down the Nile to Alexandria.Footnote 40

We also find such relationships among the background noise of Buddhist Jātaka texts, parables regarding the previous lives of the Buddha. In an early example, the Pāli Khadiraṅgāra Jātaka, a wealthy investor, or mahāseṭṭhi, has loaned eighteen gold crores to third parties through an agent, or āyuttaka, who then collects on the debts for his principal.Footnote 41 The use of credit instruments to finance long-distance commercial ventures can also be gleaned from similar sources, which mention the use of promissory notes (iṇapaṇṇa) or investors purchasing cargoes arriving from overseas through the pledge of a security.Footnote 42 What we see here is the development of an organizational principle for financing these ventures throughout the Indian Ocean world, namely the forwarding of capital by wealthy principals to merchant agents through some form of credit operation, to be repaid upon the return of the vessel (whether in cash or cargo). It is a surprisingly flexible arrangement, provided that trust had been established between all parties and the capital involved possessed sufficient liquidity; financial tools, including contracts and credit instruments, helped to guarantee these conditions.

Corporate structures of traders proved an additional form of organization throughout the ancient world. Under Roman law, maritime traders could organize under flexible business contracts called societates or more formalized corporate bodies known as collegia.Footnote 43 Throughout the eastern Mediterranean, Arabians from the region of Nabataea and the Syrian city of Palmyra used collective caravan structures (synodiai), which enabled the safe conveyance of product belonging to multiple individuals under the auspices of a caravan-leader (synodiarchēs).Footnote 44 The Indian subcontinent sustained its fair share of corporate groups, granted sanction in Indian legal codes like the Manusmṛti, which include the śreṇī (seṇi), vaṇig-grāma (vaniya-gāma), and nigama. Footnote 45 We have epigraphic testimony for several corporate groups built around certain professions, as well as other dedicatory inscriptions that record individual tradersFootnote 46 and their larger corporations: for instance, a so-called ‘organization of sea-traders’ made a dedication at the coastal Buddhist monastery at Kanheri, while a vāniya-gāma, literally a ‘merchant village’, from Dhēnukākaṭa dedicated inland at Karle alongside yavanas.Footnote 47 Although these structures differ in the exact nature of their composition—and certainly differ from the early modern European corporation—they nonetheless share important structural characteristics and operational imperatives, such as pooling finances and resources, regulating constituent members, and coordinating commercial activities.Footnote 48

Principal-agent relationships and corporate bodies are not mutually exclusive forms of organization—a principal could in theory finance an agent to be involved in a more collective arrangement (e.g. a societas contract) or even sponsor the activities of an entire corporation. In the context of Indian Ocean commerce, we might place Marcus Ulpius Yarhai, a second-century investor from Palmyra, into this category; he receives numerous honorary inscriptions from corporate groups of Palmyrene traders returning by ship from India, ventures which he financed.Footnote 49 A funerary relief from the monumental tomb of Julius Aurelius Marona (236 CE), another Palmyrene and Roman citizen, depicts the man with a ship in the background and a camel to his right—symbols of the overland caravans and maritime trade ventures in which he was involved, likely as a financier.Footnote 50 Still other subjects of funerary reliefs from the desert city, who remain anonymous due to fragmentary inscriptions, are depicted in death with the camel caravans that made them so wealthy in life.Footnote 51

Both forms of organization relied on the division of labour between investors, shipowners, and the merchants who carried out actual transactions on the ground. Such specialization arose from the realities of wealth disparity—very few had sufficient credit or an ocean-going vessel at their disposal. Epigraphic material from Egypt, Syria, and India clearly distinguishes different roles within trading ventures through a specialized vocabulary, between investors and corporate leadership (whether of caravans or other corporations), shipowners, and traders (see Table 1). For instance, those leaving Prakrit graffiti at Socotra often differentiate themselves as mariners, nāvikas, or individual merchants, vānikas.Footnote 52 While some commercial agents were in charge of their own ships and cargoes, such as the female duo Ailia Isidora and Ailia Olympias of Egypt, who present themselves as both ‘ship-owners and merchants of the Red Sea’ (nauklēroi kai emporoi Erythraikai), such exceptions tend to be expressed through a doubling of specific terminology.Footnote 53 Trading associations throughout the Indian Ocean world undoubtedly contained both, though inscriptions usually specify individuated organizations: for example, two Palmyrene groups—one of emporoi, another of nauklēroi—both of which are attested in Egypt.Footnote 54 Thus, emporoi and nauklēroi were closely aligned or even conflated with one another, but they nonetheless remained distinct categories in the minds of traders when they chose to identify as such. Still others could participate in commercial activities on the Indian Ocean without explicitly self-identifying, much as Tomas Høisæter has demonstrated in this SI for commercial agents in the Taklamakan.

Table 1. Trader Terminology

Regardless of minute differences in organization, these trader-related institutions sought to create viable and sufficient lines of capital for large commercial enterprises and to mitigate an array of associated risks. Such arrangements cut out middlemen, who could misrepresent market conditions to their own advantage over such vast distances; instead, trade was carried out by agents financially or socially obligated to principal investors, or else by representatives of a partnership or corporate group with shared affiliation and interest in the success of the venture. The game of Indo-Mediterranean trade came with a series of necessary conditions, logical rules, and opportunities meant to help players advance and, more importantly, to protect them as they played.

What about ancient states? Were they players or did they shape the game? There are rare instances in which states ‘played the game’ alongside private commercial agents, such as the presence of Tamil ‘chiefs’ in inscriptions and graffiti, who have been deemed examples of Polanyian ‘administered trade’,Footnote 55 or the involvement of Roman imperial freedmen and slaves in trade along the roads of the Eastern Desert in Egypt.Footnote 56 However, the priority of explicit state involvement in Indian Ocean commerce appears to have been revenue extraction through tariffs. High rates of indirect taxation are to be found on either end of the Arabian Sea, including the Roman tetarte tariff of 25%Footnote 57 and the 15–20% recommended in Indian shastric texts.Footnote 58 The potentials for profit were sizeable—if we take the cargo preserved in the Muziris Papyrus as an especially large example, the amount to be collected in tax ranged in the millions of sesterces, a substantial sum in light of Pliny’s deficit concerns. Moreover, states employed their own strategies to achieve their objective. As discused below, they often contracted the levy of these taxes to private individuals or corporate groups in order to obtain this revenue without the cost or logistical hurdles of collection. This may reflect what Andrew Wilson has described as a ‘game theory’ mentality of states, which attempted to find the largest sum they could tax without completely discouraging trade.Footnote 59

Commerce conducted over such vast distances might be hindered by factors that created an environment of risk to maritime ventures (e.g. piracy)—risk which in turn deterred investment. States could counteract this through regional diplomatic efforts or else by providing an armed presence in high-traffic zones. Ancient sources indicate that this two-pronged strategy happened to a certain extent at a regional level: for instance, the Romans attempted to fortify the Red Sea, particularly in the second century, manning a military outpost in the Farasan Islands,Footnote 60 possibly instituting a ‘Red Sea fleet’,Footnote 61 and forging diplomatic ties with several desert tribes bordering the province of Arabia.Footnote 62 Ancient ‘India’ was certainly not a monolithic political entity in antiquity (despite what the first half of ‘Indo-Roman’ implies). Textual and epigraphic sources record conflicts between ancient Indian polities, such as that between Deccani Śātavāhanas and the Western Kṣatrapas of Gujarat;Footnote 63 these dynasties also made regional alliances through marriage in an effort to outflank their rivals.Footnote 64 Infrastructure works—the fortified roads in the Eastern Desert of EgyptFootnote 65 or through the steep passes of the western Ghats (see Figure 1),Footnote 66 warehouses for imported goods,Footnote 67 rest houses and ferry crossings throughout the Deccan (e.g. those sponsored by the Western Kṣatrapa notable Uṣavadāta)Footnote 68—all provided opportunities for the deployment of armed personnel by the state to aid and protect those conducting commerce or, better yet, monitor their activities.

Figure 1. Naneghat Pass through the western Ghats, Maharashtra, India [Photo: Simmons].

We could view all the initiatives of states, from regional diplomacy and skirmishes to fortification and infrastructure, as creating a monitoring system that ensured the inflow of capital with the least amount of direct involvement possible. Even if states were more concerned with promoting security or benefaction as opposed to commerce, their actions did provide some baseline structure to private commercial transactions. Ancient states afforded stability to economic actors through the promotion of certain economic and legal institutions, such as the enforcement of contracts and loans; the longevity of these institutions inspired confidence in the system and resulted in the formation of fixed procedures, thereby lowering transaction costs.Footnote 69 The construction of ports and roads—literal paths on which traders depended—together with the cessation or eruption of hostilities between states, dictated the direction, speed, and volume of commercial activities, fundamental elements of the game.

Such an assessment comes with ready caveats. For one, no singular political economy or type of ‘state’ was shared throughout the ancient Indian Ocean world. For instance, the Tamil ‘chiefdoms’ of southern India, differing in many respects to the polities further north in the subcontinent, essentially monopolized pepper production and thus had particular motivations in developing ports during moments of intensified external trade.Footnote 70 Moreover, diplomacy between state actors was far more effective on a regional scale. Suggestions of tangible amicitia or diplomatic relations spanning the Arabian Sea, with Rome as the primary impetus for rulers in the subcontinent to engage in security operations to protect foreign merchants, seem like thin veils for primitivism tied to labels such as ‘Indo-Roman’.Footnote 71 In fact, despite the oft-discussed references to Roman diplomatic encounters with Indians, Scythians, and Bactrians, it is hard to find any tangible policy outcomes of such meetings beyond pageantry. For example, the information about Taprobane (modern Sri Lanka) supposedly communicated to the Romans through a Singhalese embassy reeks of Greco-Roman ethnographic tropes rather than substantial diplomatic intelligence.Footnote 72 As we will see, mercantile networks often proved more useful for the rapid dissemination of up-to-date information about market conditions.

Moreover, security efforts, infrastructure initiatives, and normative precepts against piracyFootnote 73 prevalent in states throughout the ancient world could not eliminate all dangers to sailors or facilitate all of the terrestrial logistics. Private transportation and security personnel often filled gaps in the system, whether it be Nikanor’s transportation company operating in first-century Egypt,Footnote 74 or Palmyrene camel caravans of the second and third centuries coordinating goods through Mesopotamia (see Figure 2).Footnote 75 As mentioned above, the borrower in the contract preserved on the Muziris Papyrus promises to arrange transportation for the cargo once it arrived in Egypt, including cameleers to transport goods from the Red Sea coast to the Nile and riverine transport on to Alexandria. Buddhist Jātakas repeatedly describe how donkeys and bullock cart services (together with security personnel) could be contracted for journeys from the coastal strip to the interior of peninsular India.Footnote 76 Despite the Roman outpost at Farasan or the anti-piracy fleet along the Konkan (mentioned in the Periplus),Footnote 77 multiple textual sources recommend that private trading vessels equip archers just in case.Footnote 78

Figure 2. Terracotta camel carrying transport amphorae, 2nd–3rd c. CE, Egypt (Metropolitan Museum of Art 89.2.2093) [Photo: MMA (public domain)].

Thus, states shaped certain aspects of the game, even if unintentionally. They fostered institutional frameworks and path dependencies used by private agents, which, together with climatological and technological limitations, governed the course of safe and expedient commerce. However, as much as they provided path dependencies, they left potholes along the way in the form of unmitigated risks and additional transaction costs to be managed by private trading ventures. Of course, traders seeking to avoid taxes and state controls could always try their luck by circumventing watchdogs in the desert or on the seas, thereby eschewing the incidental benefits they offered—a roll of the dice that could spell disaster or yield advantage.Footnote 79

The strategies

With ancient states, institutions, and organizational factors setting the rules of the game, we can now explore possible strategies used by our players to lower the transaction costs of their trading activities. Four targeted questions of the evidence and institutions encountered thus far will help to identify these strategies. In addressing these questions, this section will appeal not only to the evidence for the trading communities outlined above, but also to later medieval source material as comparanda, since they preserve common strategies of pre-modern commerce.

Question 1: How did agents within a trading venture establish trust with their business partners? As we have seen, the implicit trust of members within ancient economic institutions, secured through social relationships or legally-binding contracts, minimized risk, thereby lowering transaction costs. However, these bonds were all the stronger when members of these groups shared other aspects of identity, such as ethnicity or creed. These associations encouraged the formation of what theorists call ‘multiplex relationships’—individuals possessing shared heritage, beliefs, and financial motivations are all the more likely to provide one another with support and protection when facing the adversity of an unknown environment.Footnote 80 As Avner Greif has noted for Maghrebi traders of the eleventh century, such groups also allowed for collective supervision and self-regulation, which were necessary factors for maintaining the good standing of the community and, as a result, the success of their business ventures.Footnote 81 Self-professed multiplex relationships of corporate bodies can be found throughout the ancient world, from the groups of Palmyrene traders and shipowners attested in Egypt, to the Nabatean traders in the Italian port of Puteoli and the yavanas of Dhēnukākaṭa.Footnote 82

These multiplex relationships fostered another division of labour little discussed for the ancient period, namely that between groups of merchants residing in diaspora and seasonal or itinerate shippers.Footnote 83 While itinerant or seasonal merchants carried out the transoceanic crossings at the appropriate times of year, long-term resident alien communities maintained commercial relationships with their buyers and suppliers in foreign lands, acquired familiarity with local institutions, and could facilitate the resolution of any business conflicts abroad. This kind of arrangement would dramatically lower transaction costs, since the formation of new relationships with local suppliers and community leaders did not have to be reestablished with each new transoceanic crossing, and seasonal traders could deal with trusted entities.Footnote 84 Moreover, such communities could disseminate knowledge of how best to conduct business in new environments and how to navigate local institutions to their commercial advantage.

This procedure has been suggested for many pre-modern trading groups, such as those involved in the Austronesian maritime routes analyzed in Jiun-Yu Liu’s contribution to this SI; they also apply to the trading groups surveyed in this article. Katia Schörle has recently argued that Palmyrene caravans could make use of fluvial transport on the Euphrates and organize transfers to seagoing vessels via the site of Spasinou Charax near the Persian Gulf in almost ‘vertically integrated’ structures, all without having to contract merchants outside the community.Footnote 85 Similar arguments are to be found for yavanas in the south of the subcontinent. For instance, communities in Coromandel ports (e.g. Puhar and Arikamedu) and Malabar ones (Muziris) could coordinate the movement of products across or around the tip of the subcontinent.Footnote 86 Scholars including André Tchernia and Kasper Evers have argued that yavanas throughout the subcontinent could have served as intermediaries between local suppliers or investors and foreign traders at Indian ports;Footnote 87 Romila Thapar and Federico De Romanis among others call for more nuanced dynamics between extra- and intra-regional exchange systems, especially in south India.Footnote 88 The common prerequisite behind these theoretical arrangements, which all point to some form of deterritorialization (see Cobb’s introductory article in this SI), is the multiplex relationship, which lowered transaction costs by reinforcing a sense of trust between business partners of shared heritage situated thousands of kilometres apart.

Question 2: How did these ventures communicate over such vast distances? Up-to-date information about market conditions or the progress of a business venture is one of the principal ways of lowering commercial transaction costs, but it was a rare commodity in an age before extensive telecommunication. Group formations, such as the organizations of foreign traders mentioned above, inherently enabled a more efficient means of accumulating knowledge through experience and communicating that information between constituent members. Beyond face-to-face conversations, institutional knowledge could be disseminated in a few ways. Specialized textual sources, most notably the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, synthesized relevant information, whether it be the best items for trade at specific ports, potential coastal hazards, and areas where piracy was prominent; pilots with intimate knowledge of dangerous waterways were crucial in this regard as well.Footnote 89 Communication between traders and their investors could also occur via letter, as we see in the later Cairo Geniza Archive, a repository of documents including those written by Jewish merchants from the tenth to thirteenth centuries.Footnote 90 Personal letters between inhabitants of Greco-Roman Egypt proved essential for communicating market conditions and circulating products within exchange networks.Footnote 91 Unfortunately, not many explicitly ‘mercantile’ letters survive from the early centuries of the Common Era, or else they were written through media that would have ensured their erasure upon completion of the venture (e.g. wax tablets).Footnote 92 In any case, letters could only come and go with the seasonal winds, along with traders themselves.

One way to work around the seasonal limitations of information sharing was to specify exact ports of call and return-by dates. In a Mediterranean context, such an arrangement is preserved in an opinion of the second-century Roman jurist Scaevola, wherein a firm leave-by date for a trading venture from Syria to Italy was included in the wording of a bottomry loan.Footnote 93 As we saw, the loan preserved in the Muziris Papyrus specifies the exact route that the financed cargo would travel. Such fixed itineraries and deadlines gave investors some protection on their investments; deviation from the agreed-upon dates, when formalized in contracts, resulted in forfeiture in their favour. The reliable schedule of the monsoon winds made fixing deadlines in Indian Ocean commerce a simple affair: e.g. ships could pass through the Bab-el-Mandeb no later than August and could depart from southwestern India between December and January; if all went according to plan, a roundtrip journey between Egypt and western India could be completed within a single calendar year.Footnote 94

We can look to other forms of communication that enabled the dissemination of information more effectively among trader communities. Word of mouth or rumour could often communicate information with a surprising level of accuracy, especially when the veracity of the information was of direct relevance to a financial operation.Footnote 95 Word of mouth channels, particularly those relayed from well-established ‘ports of trade’, would have been pertinent for learning about the situation across the sea during the previous year.Footnote 96 In fact, the second-century Greek geographer Ptolemy notes that his work benefited from the testimony of traders, who relayed updated coordinate points and topographic descriptions of the subcontinent—a way in which the first-hand and orally-transmitted experience of a trading network entered into academic compilations of knowledge.Footnote 97

Graffiti could also serve important communicative roles, as recent studies have shown.Footnote 98 Inscriptions at key locations frequented by traders, such as roads in the Eastern Desert of Egypt, the Darb al-Bakrah of northwestern Arabia, or the Hoq cave on Socotra, suggest both imitative and dialogic tendencies of their inscribers.Footnote 99 The repetition of formulae and the conscious reaction to what has already been written reveal that such traders actually read or acknowledged the graffiti of their predecessors, and thus, that these writings were effective forms of communication. This may explain the proliferation of named inscriptions with the phrase ‘has arrived.’ Thirty-four of the Indic inscriptions of Socotra add the participle prāptaḥ or āgataḥ following the name of the inscriber, marking his ‘arrival’ to the cave; Footnote 100 this is similar to the practice of the Nabatean caravanner Nussaigu, who left ‘arrival’ inscriptions at points along the roads of the Sinai Desert.Footnote 101 These could serve as markers for subsequent traders in the same outfit or record the completion of transactions on-schedule. In the context of the Hoq cave, we should also consider these messages in light of an ‘arrival’ in a religiously charged space—as we shall see, traders could communicate as they practiced their faith.

Such forms of communication required some standard of literacy among these operators, and, in some cases, multilingualism.Footnote 102 Stories recorded in Greco-Roman sources attest to traders learning the language of their host country while abroad in order to find success, such as a freedman-agent of Annius Plocamus in Sri Lanka or a shipwrecked Indian in Ptolemaic Egypt.Footnote 103 Rather than dismissing these incidents as apocryphal, we should read them as reflecting a real trader strategy of multilingualism that can be gleaned from surviving instances of bilingual writing by the same individual. Palmyrene traders regularly engaged in bilingualism, as embodied by the sailor Abgar on Socotra, who left both an Aramaic tablet and a Greek graffito in the Hoq cave.Footnote 104 A further example is Lysas, another agent of the principal Annius Plocamus, who announces his operations in both Greek and Latin on the road from Berenike to Coptos in Egypt; a certain Gaius Peticius also leaves his name in both languages.Footnote 105 Although yavana dedications at Buddhist sites were written in Prakrit—and dedicators occasionally assume generic Indic names—references to the harsh yavana language in Indian textual sources imply the potential for the continued use of native tongues while abroad.Footnote 106 Members of foreign merchant groups could still use their primary language for internal interactions, but knowledge of additional languages for different domains of usage, code-switching, and even limited literacy facilitated global operations.

Question 3: How did these traders sustain themselves while abroad? Built environments supported traders in ways that reinforced their multiplex relationships. We have seen suggestive evidence of specific urban quarters inhabited by foreign traders (e.g. the descriptions of yavana traders in Puhar), as well as concentration patterns of foreign utilitarian pottery in ports ranging from Myos Hormos to Arikamedu. There were also larger communities of foreigners, as was the case with the numerous yavanas from Dhēnukākaṭa.Footnote 107 The lease of Socotra to Arabian and Indian settlers granted by a south Arabian king is recorded in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, an arrangement that included the king’s protection.Footnote 108 We can understand these outposts as mutually beneficial, since traders received real estate for their business ventures and political bodies could better monitor their activities.

Additional evidence attests to physical structures for exclusive use by seasonal or diaspora traders. These were used to coordinate trading activities or else served as places of congregation for institutional support. These types of structures for Mediterranean-based foreign traders in Roman Italy include the so-called ‘house of the Alexandrians’ and the Tyrian trading-stations in Rome and Puteoli.Footnote 109 Another example is a communal space for the association of Palmyrene Red Sea shipowners (nauklēroi) set up in the Nilotic city of Coptos—one of many established for the benefit of the Palmyrene diaspora throughout the ancient world.Footnote 110 In the subcontinent, royals sponsored rest houses for itinerant traders alongside other infrastructure initiatives, such as the ferry-landings created by Uṣavadāta mentioned above; yet others appear to have been built on private initiative, such as those described in passing in the fictional Bṛhatkathāślokasaṃgraha.Footnote 111 Gatherings of traders within these communal structures undoubtedly aided the rapid dissemination of oral information far more efficiently than individual conversations or written communications.Footnote 112

Many diaspora communities also had shared religious spaces, which served not only as places to ensure divine sanction for commercial activities and agreements, but also as nodal points for socialization. These include the Nabatean temple of Dushara in Puteoli (of which inscriptional evidence survives)Footnote 113 and the so-called ‘shrine of the Palmyrenes’ excavated at Berenike, which accommodated the worship of the Roman imperial cult, the Palmyrene god Yarhibol, and the Egyptian god Harpokrates;Footnote 114 in fact, continued excavations at the port have yielded even more tantalizing evidence of foreign religious activity there, including material finds of south Asian character (e.g. images of the Buddha and a Sanskrit dedicatory inscription).Footnote 115 Although the notion of a temple to the Roman emperor Augustus in Muziris, as shown on the late antique Peutinger Table, is hotly debated—and suggestions of a Roman military outpost in MalabarFootnote 116 are based on misinterpretations of this source—its presence nevertheless alludes to a much larger phenomenon throughout the Indian Ocean network.Footnote 117 As Taco Terpstra has argued, the presence of these safe spaces marked the ‘collective separateness’ of foreign residents from their host community and could serve to reinforce critical multiplex relationships.Footnote 118

In some cases, such religious spaces fostered a direct dialogue between traders of different backgrounds, as we find on Socotra. The Hoq cave, with its spectacular rock formations, provided what has been called a ‘neutral religious space’ for the multicultural inhabitants; we find the presence of incense burners throughout the cave complex, as well as inscribed religious symbols, ranging from those of broader significance (e.g. tridents) to specifically Buddhist stūpas and dharmacakras.Footnote 119 In fact, both the Palmyrene tablet of Abgar and the Greek inscription of a shipowner named Septimius Paniskus refer to the religious nature of their visit to the cave.Footnote 120 More established Buddhist sites in the Indian subcontinent also welcomed dedications from numerous individuals, whether practicing Buddhists or not, including the local yavana community there (see Figure 3). In these religious accommodations, which facilitated the development of ‘social world systems’ (as Signe Cohen has discussed in her contribution to this SI), diverse traders could find a shared religious experience—another fold of their multiplex relationships.

Figure 3. Dedicatory inscription on pillar by ‘Yavana of the Chulakayas’ from Dhenukākaṭa, Karle caitya (EI 18.36.6) [Photo: Simmons].

If we look back to one of our Indian graffiti from Myos Hormos, three Indian traders list perishable food items they acquired in Egypt; traders needed to obtain foodstuffs from local suppliers while abroad. Further records of the transportation of commodities through the Eastern Desert and customs forms at Berenike reveal that Egyptian grain arrived to the Red Sea ports between May and June—precisely in time for the outfitting of ships and the massive outflow of traders before July; wine arrived in port between October and January, in time for purchase and consumption by visiting traders much like our Indian trio.Footnote 121 However, archaeobotanical evidence from systematic excavation at these Egyptian ports reveals several imported food items from the subcontinent including coconut and rice; these were probably meant for consumption by Indian traders, since little record of these products is to be found in Mediterranean sources.Footnote 122 Such finds often lie in the shadow of more sensational discoveries, such as a large hoard of Malabar peppercorns uncovered at Berenike.Footnote 123

Seasonal yavanas may also have brought provisions with them for their stay in India, as suggested by Spanish amphorae found in Arikamedu which once contained Roman fish sauce, a product with little known market in the subcontinent.Footnote 124 The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea also mentions the importation of staple commodities across the Indian Ocean to feed mercantile communities. Grain reached Malabar ports like Muziris specifically ‘for those involved with shipping’ (tois peri to nauklērion), i.e. for the seasonal yavana community.Footnote 125 Similarly, the island of Socotra received both grain and rice from those sailing out of Barygaza and the Malabar Coast due to the shortage of these commodities on the island.Footnote 126 Food imported to the island was meant to supply a community of traders from throughout the Indian Ocean network.

Finally, Question 4: How did traders achieve a strategic advantage over their competitors? Incentives from the state, whether intentional policies or unintended byproducts of its actions, served as one means for players to achieve an advantageous position.Footnote 127 One such incentive came from the prevalent use of tax-farming by ancient states to collect high tariffs on Indian Ocean products, a phenomenon briefly addressed above.Footnote 128 Much like states setting the rates of tariffs to ensure the optimal stream of revenue, the contracted tax-farmers undoubtedly engaged in a similar ‘game theory’ calculation to determine how much revenue they could pledge to states in a contractual bid (with the promise of keeping any extra sums for themselves) without discouraging commerce in areas of tariff collection.

In the Mediterranean, individuals from Italy, Egypt, and Syria involved in financing the trade could also operate in the collection of indirect taxes on behalf of the Roman Empire; such tax-farmers were often called arabarchai or paralēmptai.Footnote 129 Annius Plocamus, whom we encountered above as a principal financing agents, and the unnamed paralēmptēs of the Muziris Papyrus financed elements of the very trading ventures they were charged to tax.Footnote 130 The sheer wealth gained from this practice could be harnessed by individual families, which both carried out state contracts and made their own commercial investments. For example, Alexander the Arabarch’s son, Marcus Julius Alexander, appears in the Nikanor Archive as someone personally involved in trade activity at Berenike between 37 and 44 CE.Footnote 131 In these instances of what we might now term ‘collusion’ or ‘ambient corruption’, we find agents of commerce not only exploiting the system to their advantage, but also lowering the transaction costs of commerce. Tax-farming principals could easily deduct taxes from profits on maritime investments rather than hunt down renegade traders; moreover, they could use any profits from tax-collection to finance subsequent ventures. All the while, the state received its cut.

We unfortunately do not have contemporary records of individual tax-collectors from the Indian subcontinent. Starting in the mid-first millennium CE, corporate groups throughout the subcontinent become responsible for tariff collection, much as in the Mediterranean world centuries earlier.Footnote 132 However, a tantalizing and overlooked passage in the Milindapañha, a first- or second-century Pāli Buddhist dialogue, suggests the practice occurred much earlier. In the course of the text, the Buddhist monk Nāgasena introduces a simile regarding the attainment of nirvāṇa: just as a nāvika, wealthy through constantly levying tariffs in a seaport (paṭṭane suṭṭhu katasuṅko mahāsamuddaṁ pavisitvā), will be able to sail across the great sea to destinations including China, southeast Asia, and ‘Alexandria’ (exactly which one is debated), so too will one who conducted his life according Buddhist doctrine in former births obtain all the benefits of nirvāṇa. Footnote 133 We find something quite significant in this simile: that an Indian merchant involved in oceanic trade was also involved in the collection of tariffs, much like investors tapped by the Roman state in the Mediterranean world; and, much like their western counterparts, this individual could use the wealth gained through tax-collection to finance future overseas endeavours. Exploitation of incentives, alongside the many other strategies we have explored, is not a practice confined to a single culture, but rather represents another instance of an economic calculus shared by those involved in transoceanic trade.

Final thoughts

A great game was played in the shadow of gold for pepper. Not much could be done by human agents to change the pattern of the monsoon winds and the path dependencies of ancient economies, but our players adapted in innovative ways. Private organization in the form of principal-agent relationships, corporate bodies, diaspora communities, and temporary contracts enabled successful transoceanic movement. Corporate structures or long-term resident alien groups built around multiplex relationships could lower transaction costs by serving as sources of institutional support for seasonal visitors. Trading groups could attain competitive advantages by exploiting the incentives and loopholes of local support networks and top-down state initiatives.

The most sophisticated players, such as Annius Plocamus or the anonymous nāvika of the Milindapañha we have just seen, could reap with one hand and sow with the other, manipulating the rules of game to their advantage. In other instances, ‘micro-strategies’, including the communicative ones explored in this article and code-switching used by yavanas in India, some of whom take indigenous names much like Nabatean and Palmyrene traders in the Mediterranean world, make the game happen one transaction or community at a time.Footnote 134 However, through a comparative framework, we can find a sense of balance to the trade, in which players from numerous cultural backgrounds formulated common stratagems grounded in shared human experience. Their successes in turn provided a steady supply of commodities to meet consumer demand throughout the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean worlds.

From the approach adopted in this article, it becomes clear that ‘Indo-Roman’ is a misnomer: no one ‘Rome’ traded with one ‘India’; rather, exchange between them involved an intricate patchwork of individuals, trading ventures, and organized communities which become inextricably linked with the products of their trade. The designation ‘Indo-Roman’ is haunted by the spectre of scholarly approaches, whether colonial or nationalist; it unduly conflates polity and geography and excludes actors who regularly participated in the Indian Ocean network. Romans participated, yes, but more specifically Italians, Greeks, Egyptians, Nabateans, Palmyrenes, and many others whose exact ethnic and cultural identity remains beyond our grasp. The subcontinent contributed its fair share of diversity to the trade, as did other regions beyond the scope of this article, such as south Arabia, east Africa, central Asia, and the littoral of the Red Sea and Persian Gulf.Footnote 135 Several player typologies emerge beyond principal investors and their agents, beyond shipowners and merchants—contracted transportation and security personnel, processors and craftsmen, free and enslaved individuals filled in the gaps and mitigated additional risks unmet by institutional solutions.Footnote 136 The eligible players well-exceed the singular class of ‘Alexandrian merchants’, whom Michael Rostovtzeff once regarded as the true governing force of the trade between Rome and regions further east.Footnote 137

As repeatedly argued above, the label ‘Indo-Roman’, an uneven hyphenation between the Roman Empire and an Indian subcontinent controlled by various polities, is by no means innocuous. ‘Indo-Mediterranean’ stands as a more accurate label for the series of trade connections explored in this article; it emphasizes a convergence between the distinct maritime worlds of the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean, rather than a mismatch of political and geographical terminology. The human agents of commerce go beyond terrestrial categories; forcing them under a label such as ‘Indo-Roman’ for heuristic convenience does little good, given how easily such nomenclature has been used to designate ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ on an civilizational level.Footnote 138 Indeed, there are ‘winners’ and ‘loser’ in every game, but players ought to be measured by their success within a globalized, Indo-Mediterranean ‘arena’, not with regard to the Indian or Roman ‘teams’ to which they allegedly belonged. When the stakes of academic agonism disappear, we can better understand the exact role of polity in the game—how individuals associated with ancient states shaped some of the rules and played in a limited capacity.

This model of ‘Indo-Mediterranean’ trade also allows us to consider whether transoceanic links of the early first millennium CE were especially unique. In the longue durée of the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean, the game oscillates between moments of concerted engagement and abatement. Trade spanning both waterways occurred before the centuries covered in this article and with similar intensity in subsequent periods of antiquity that do not equate with the ‘Roman’ period; accordingly, the use of ‘Indo-Roman’ as a marker of relative temporality is easily replaced by more targeted date ranges denoting the ebbs and flows of connectivity.Footnote 139 Recent Indian Ocean scholarship has emphasized the early centuries of the Common Era (rather than the conventional dates of the Roman Empire), a period that Philippe Beaujard has described as heralding the integration of distinct world systems into the first large-scale ‘Afro-Eurasian’ one.Footnote 140 However, rather than privileging political economy and commercial revolutions as the main impetuses for connectivity—this might unwittingly lead us to a very ‘Indo-Roman’ conclusion that Roman imperialism or the consumer demand of its empire alone dictated global commerce—this article has provided a much needed reorientation towards the human beings that made this trade possible, in addition to the circulation of goods and ideas.

Framing the evidence in terms of ‘players’ and the ‘game’ allows us to evaluate both quantitative (i.e. the number of players) and qualitative (their strategies) changes in the longue durée. Institutions and path dependencies promoted and enforced by several ancient polities, as well as those developed by mercantile agents themselves, provided rules by which to win the game. The more people played the game by these rules, the safer the game became for everyone. External factors (e.g. climatological or demographic shifts) or the degradation of institutions and social relationships, which made the game an enticing prospect, could disrupt the pace of play; but the tempo might accelerate once more with the proliferation of institutions, players, and strategies.Footnote 141 The expansion of the game to a critical mass of players hitherto unseen in the ancient world best characterizes ancient Indo-Mediterranean trade. While later periods encouraged the use of similar strategies by human agents, the initial centuries of the Common Era represent an early peak of economic intensity on the Indian Ocean. It is a testament to ancient commercial organization that so many of its strategies remain in use over time.

By depoliticizing the trade, this article has argued that traders from differing cultural backgrounds employed similar structures and strategies, a development that stemmed from a calculus of economic behaviour shared by the players of the game. Despite the paucity of data from antiquity when compared to later periods—ancient historians would be thrilled to have detailed documentary sources like the Cairo Geniza Archive or the records of Portuguese pepper-ships in Malabar—the plurality of moving parts points to some form of self-regulating economic activity.Footnote 142 These factors should guide us as we continue to refine this model of the trade relations between sub-regions of the wider Afro-Eurasian world. Without recourse to an outdated conception of ‘Indo-Roman’ trade, the many iterations of this game and the changing roster of its players extend from antiquity until the early modern period—perhaps a daunting prospect, but one that promises to enrich global history.

Jeremy A. Simmons is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Maryland, College Park. His research addresses the consumption of commodities traded across the Indian Ocean in antiquity, as well as the human agents who made global connections possible.