At the age of fourteen, in 1775, Charles Bowles enlisted in the Massachusetts militia during the Siege of Boston. Two years later, Bowles decided “to risk his life in defense of the holy cause of liberty” and joined the Continental army where he would serve until the end of the War of Independence in 1783. After seeing hell during the war, Bowles retired from military life and settled in New Hampshire where he took up “agricultural pursuits”, became a Baptist preacher, and drew a pension, dying at the age of eighty-two in 1843.

Given Bowles's seemingly traditional English name, his patriotic fervor, and his relocating to the frontier, his story echoes that of many Americans in the aftermath of the American Revolution. Yet, Bowles had been born a slave in Boston, his father an African and his mother a creole, or locally born, black woman, and used his service in the army to find freedom. His life was more reflective of an enslaved Bostonian during the American Revolution than a white frontiersman. Born in 1761, Bowles grew up in a world where slavery was under assault, but still common. The slavery Bowles experienced in Boston meant he would have most likely grown up learning a skilled trade, traveled around town with his parents and master, and attended religious services. All of these factors ultimately shaped his freedom as Bowles used his mobility and skills to escape to the army, move to New Hampshire, take up farming, and become a minister. In that sense, the experience of Bowles was like that of so many other enslaved and freed Bostonians. Whether voluntary or involuntary, abolition in Boston coincided with the exodus of a large percentage of the black population.Footnote 1

This article explores the lives of men like Charles Bowles to better understand why Boston's black population, which consisted of more than 1,500 people or more than ten per cent of the town's population in 1750, declined precipitously over the course of the revolutionary era. The town's black population declined by at least fifty per cent between 1760 and 1790 and even in 1850 consisted of only 1,999 people, only 400 more than during its colonial zenith. This disappearing act was the product of four decades of warfare, revolution, economic transformation, and ideological development spanning from roughly the end of the Seven Year's War in 1763 to the early nineteenth century.Footnote 2

Scholars have been studying slavery and emancipation in Boston and New England since the 1860s and the literature tends to fall into two broad camps. The first are works exploring slavery in the region, which explore slavery on its own terms in a specific time period. These works usually only contain a short chapter or epilogue on abolition.Footnote 3 Second are the studies examining abolition and emancipation in New England, which tend to only have a short introductory chapter on slavery. This scholarship also emphasizes change over continuity when dealing with the impact of abolition on black lives.Footnote 4 Thus, there is a disconnect in the literature and little overlap outside of a few citations of one another.Footnote 5 This article bridges that gap by placing how slavery functioned in Boston in conversation with the process and legacy of abolition in the town and how Boston came to fashion itself as an abolitionist city.

It is important to note that the argument put forth here is not without controversy in the historiography of slavery and abolition in New England. The idea that abolition was a process is at odds with an older historical tradition. Beginning in the 1860s, scholars argued that a 1783 court case, Commonwealth v. Jennison, brought an effective end to slavery and that by 1790, there were no slaves in Massachusetts. Upheld as an exceptional decision made by an activist judge looking to destroy slavery, the case appears in triumphalist accounts of the end of slavery in Massachusetts. There are many problems with this analysis, however. The argument made by the judge that slavery was incompatible with the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 were only in his instructions to the jury, never published, and only cited as precedent more than two decades after the decision. Moreover, even though the United States census of 1790 did not enumerate any slaves in Massachusetts, there is evidence that census takers deliberately avoided recording slaves. Meanwhile, probate and notarial records document the persistence of slavery in Boston into the mid-1790s. By embracing 1783 and 1790 as definitive dates, past historians have obfuscated the troubled, ambiguous abolition in Boston, especially the legacies of slavery in that process.Footnote 6

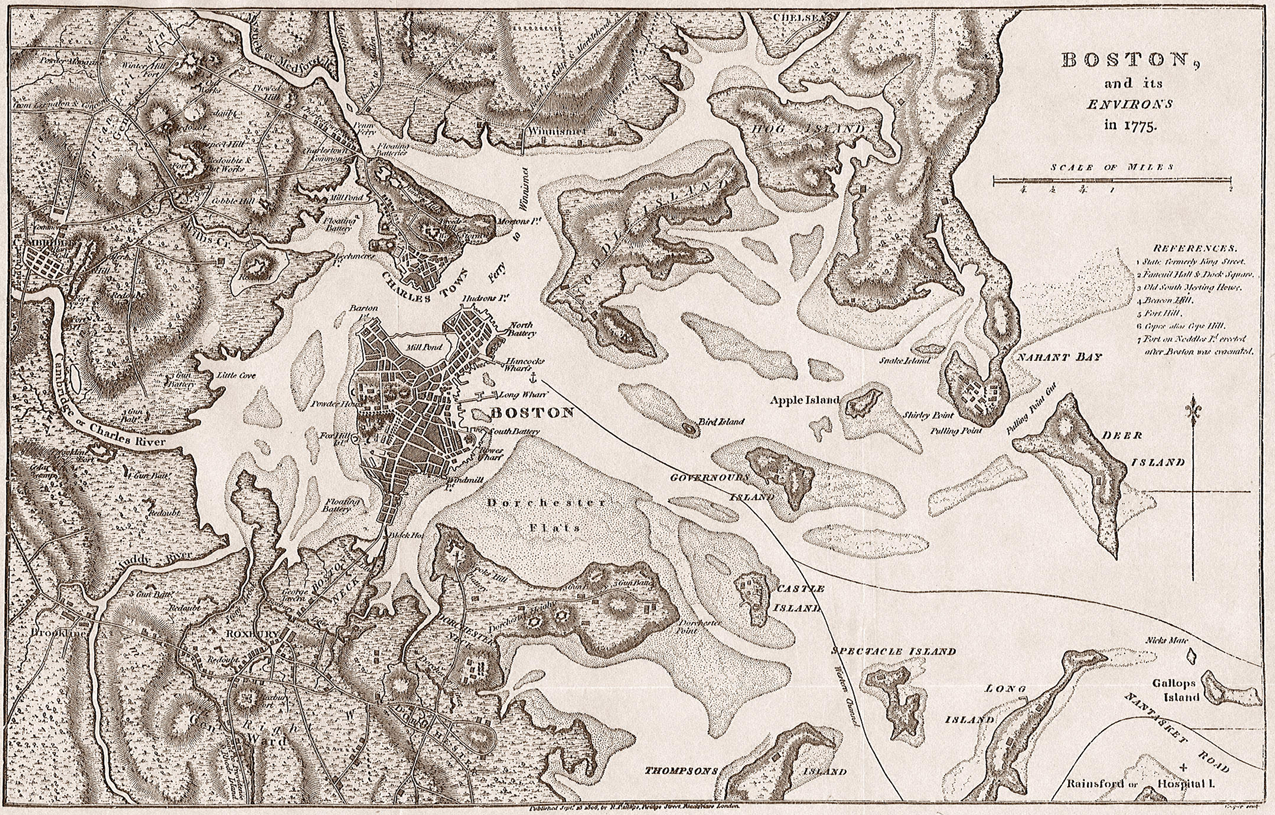

This article is therefore divided into three parts. First, it explores slavery in Boston (Figure 1). Slaves were vital to Boston's economy, filling skilled positions and providing labor for numerous industries. Second, slaves found freedom during the American Revolution using the skills they developed earlier to challenge slavery. They joined the military, absconded, found themselves the target of kidnapping, and were increasingly locked out of Boston's labor market. In short, many former slaves and their descendants left the region entirely. Finally, the legacy of abolition for black Bostonians was that Boston's original enslaved population disappeared, while the city became a hub of abolitionism in the 1820s. No longer having to deal with the living legacies of slavery, abolitionists crafted a narrative of a free Boston, making it an attractive destination for runaway slaves from across the Atlantic world.

Figure 1. Boston and its Environs, 1775.

SLAVERY IN BOSTON

Slavery in Boston laid the foundation for the town's ambivalent abolition. Only by exploring how slavery functioned and the lives of enslaved people can we better understand why slavery ended the way it did. Enslaved Bostonians faced myriad challenges, but during the eighteenth century, they lived in a dynamic urban environment that valued their labor. Although largely male, enslaved people living in Boston were skilled, mobile, and experts at using local institutions to their advantage. These traits meant slaves understood their value, could read, and sometimes write, and had intimate knowledge of geography, law, politics, and larger intellectual trends. Exploring three themes related to the lived experience of enslaved Bostonians – labor, mobility, and institutional appropriation – demonstrates how they had skillsets that allowed them to resist the quotidian dehumanization of slavery. While still human chattel, Boston's slaves eventually used these skills to forge their own freedom.

During the eighteenth century, Boston's economy, while on a nasty boom-and-bust cycle, grew rapidly, often far exceeding the town's labor capacity.Footnote 7 To address the labor shortage, Bostonians of every economic class turned to slave labor. Indeed, by the 1740s, Boston's enslaved population numbered more than 1,500 people or roughly ten per cent of the town's total population. Yet, this number is deceptive as masters often hid slaves – classified as taxable property – from census takers. More likely, African slaves comprised closer to twelve to fifteen per cent of the town's total population. And Bostonians bought these people to work. They served as seamstresses, cooks, and valets in homes and laborers in workshops, distilleries, and shipyards.

What is most striking about enslaved Bostonians, however, is just how many were trained craftsmen. They were carpenters, coopers, bakers, blacksmiths, masons, and printers. Many of them arrived in town as children, became the property of local artisans, and, in addition to living in their masters’ households, served as apprentices, learning a trade as they grew. Viewed as a long-term investment by their masters, enslaved tradesmen were central features of Boston's manufacturing sector, building houses and ships, distilling rum, and making rope. Moreover, Boston's skilled slaves held value for the town at large, providing vital labor that kept the town's economy running. Skilled jobs were not easy to fill given eighteenth-century labor structures, and enslaved people could help make up for those shortages.Footnote 8

Skilled and valued, enslaved Bostonians were able to convert these traits into autonomy and mobility, affording enslaved men and women an incredible degree of independence to define their place in eighteenth-century Boston and beyond. Likewise, Boston's enslaved population was highly mobile both within the town and across the Atlantic world. Many enslaved Bostonians found themselves free to go to the market, hire themselves out around the town and surrounding communities, or ply the sea on oceangoing ships. Others self-hired, negotiating their own contracts and work conditions, often with the explicit permission of their masters. Many slaveholders condoned bondsmen and women working independently, hoping to preserve domestic tranquility while still generating revenue. Enslaved men and women, however, took full advantage of these opportunities and used them to carve out spaces for themselves.

Facilitated by their mobility and skillsets, many slaves acquired knowledge and understanding of the world around them. Most importantly, they were accomplished appropriators, learning how to use and navigate local institutions, namely the law and religion.Footnote 9 They used these institutions to gain tangible and ultimately useful skills such as literacy and legal knowledge. Literacy came mainly from the adoption of Protestant Christianity. While it is impossible to determine if enslaved Bostonians were true believers or just using the town's many churches for their own ends, for slaves, these houses of worship were also educational centers. Given Protestantism's emphasis on the ability to access scripture, teaching reading was central to knowing God. Yet, for the many black faces in Boston's pews, reading meant more than the Bible.Footnote 10

Knowing how to read (and possibly write) opened a world of possibilities to enslaved Bostonians. Even if they could not personally read, most knew someone who could. They had access to books, pamphlets, and newspapers and this access gave slaves leverage and the ability to resist their masters. In Boston's newspapers, for example, slave-for-sale advertisements rarely contained the names of masters or slaves and usually only offered vague physical descriptions. Since so many slaves could read, it would be relatively easy for them to tip each other off about potential sales and being ripped away from family and friends.Footnote 11 Likewise, combined with their informal oral networks and enslaved sailors bringing news from abroad, enslaved men and women in Boston would have had a good sense of what was happening around the world.

Like their use of religion to gain literacy, enslaved Bostonians also used the legal system to their own advantage. Unlike today, eighteenth-century law was not as professionalized and legal knowledge was readily available to most members of society. Books on legal methods, practice, and theory proliferated across the Atlantic and were easily accessible. In addition to this general access – facilitated by literacy – many enslaved Bostonians had experience with the law. Considering the many different statutes targeting them, it should not be surprising that blacks often ran afoul of the law and appeared in court. Through reading, discussions, and experience, slaves learned how to use the law. They learned which justice of the peace would give them the fairest hearing or listen if they were being abused. Likewise, slaves learned how to file petitions or found white allies who could help. The petition was the primary tool for initiating any legal action in Anglo-American courts and multiple petitions from enslaved people exist in the Massachusetts records, demonstrating that enslaved Bostonians understood the law.Footnote 12

Boston's enslaved population was skilled, mobile, and knowledgeable. During the colonial period, they used these attributes to carve out a functional independence for themselves and find creative ways to resist both their masters and colonial authorities. They had leverage in the labor market, moved around relatively freely, and understood how to use local institutions to their advantage. Such characteristics prepared enslaved Bostonians to strike for freedom when the opportunity presented itself in the era of the American Revolution.

ABOLITION AND DISPLACEMENT

Abolition in Boston coincided with the Imperial Crisis (1763–1775), the War of Independence (1775–1783), and the aftermath of the American Revolution. It was a relatively long-term process lasting from the 1760s until the early 1800s. Largely initiated by enslaved people and their free black and white allies, emancipation did not involve legislation, gradual emancipation laws, or general freedom decrees like in other places. Rather, most enslaved people found other paths to freedom and used the skills, mobility, and knowledge they had gained during their enslavement. Nevertheless, given the extended period of abolition in Boston, it is important to remember that the end of slavery did not happen at a particular moment, but was a process. Under such ambivalent conditions, abolition severely disrupted black life. Indeed, considering the end of slavery in Boston coincided with the chaos of the American Revolution and its aftermath, the process totally upended the colonial order that black Bostonians had grown to know in both positive and negative ways. In both cases, the ultimate result was to displace the town's black population. Many served in the army and settled far away from New England, while masters, seeing the writing on the wall, sold others to Canada, the Caribbean, and the American South.

The irony, however, is that the nature of slave life in Boston shaped this displacement. Highly skilled, masters knew their enslaved men and women would fetch a good price in places where slavery was not under threat. Already mobile, many enslaved people saw service in either the Continental or British armies as an opportunity to strike for freedom. Moreover, the collapse of the New England rural economy during and after the American Revolution caused a flood of poor whites into Boston looking for work, who actively sought to displace enslaved and free black people from the town's workforce and embraced an emerging scientific racism to justify that displacement. Attuned to these larger economic and ideological changes, Afro-Bostonians voted with their feet to leave entirely.

The beginning of the end of slavery in Boston was the Imperial Crisis. As white colonists began protesting their rights and freedom from the “slavery” of arbitrary government, black Bostonians took note. Most important to this process was the rise of natural rights discourse. By the early 1770s, arguments about the traditional rights of Englishmen began to be subsumed into a greater argument about the rights of humanity.Footnote 13 Ever attuned to larger intellectual developments, Boston's black population also began using natural rights language.

This appropriation of natural rights can be seen in a series of petitions that enslaved and free blacks in Boston filed with the Massachusetts government between 1773 and 1777. All told, seven of these documents survive; black Bostonians authored all of them and they provide insight into how blacks attempted to negotiate an end to slavery by appealing to human rights. Most importantly, there is an ever-stronger insistence that freedom was natural and innate. The first petition, written in January 1773 by a free black man named Felix and addressed to the Massachusetts governor and legislature, argued that slavery, their “greatest Unhappiness”, was “not our Fault” and merely asked “for such Relief as is consistent with your Wisdom, justice, and Goodness”.Footnote 14 When that did not work, a petition in April 1773 attempted to shame the government into action, noting that even the “Spaniards, who have not those sublime ideas of freedom that English men have, are conscious that they have no right to all the service of their fellow-men, we mean the Africans […] therefore they […] enable them to earn money to purchase the residue of their time”.Footnote 15 Not only does this demonstrate that black Bostonians understood the Spanish concept of coartación (the right to self-purchase), but they could also weaponize those ideas.

Shame and pity did not work, and the government largely ignored these appeals. Later petitions were much more forceful and deployed new techniques. A third document, from May 1774, opened with a powerful decree that enslaved people “have in common with all other men a naturel right to our freedoms without Being depriv'd of them by our fellow men as we are a freeborn Pepel and have never forfeited this Blessing by aney compact or agreement whatever”.Footnote 16 Even more important, this appeal was not directed at the legislature. Rather, petitioners asked the military governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Gage – sent to quell rebellious Bostonians following the Boston Tea Party in December 1773 – for relief. This move was politically calculated. By appealing to Gage, the petitioners sent the message that although they sought an end to slavery, they were also still loyal British subjects and could possibly be called upon to confront rebellious white colonists. It is unclear how Gage regarded the petition, and, as with the previous ones, there was no movement on the issue.

The final petition, from 1777 and addressed to the revolutionary government in Massachusetts, deployed the same natural rights language as the 1774 document, arguing the petitioners were “detained in a state of Slavery in the Bowels of a free and Christian Country”. It also reflected the exasperation of petitioning six previous times to no avail, noting black Bostonians “have long and patiently waited the event of Petition after Petition by them presented to the legislative Body of this State, and can not but with grief reflect that their success has been but too similar”. Moreover, they also offered practical solutions, such as legislation that would free the children of slaves at the age of twenty-one, as part of the larger appeals to liberty.Footnote 17 Once again, however, the legislature took little action after reading the document on the floor of the assembly.

Although these petitions all failed in their stated purpose, they are still important for understanding slavery and abolition in Boston. They reveal that in an attempt to end slavery, enslaved and free black men relied on the skills and knowledge they had acquired during their time in Boston. Instead of using the petition for legal issues, they transformed it into a tool to forge freedom. Likewise, as white colonists increasingly incorporated the language of natural rights into their own appeals and arguments, black Bostonians appropriated those ideas for their own ends. They combined that knowledge with information gleaned from their own social networks and reading to appeal to local authorities.

While petitioning may have failed, increasing numbers of enslaved Bostonians gained their freedom through a variety of means. Many more enslaved people found freedom using the court system. Often referred to as “freedom suits”, these occurred when enslaved men and women would sue their masters for freedom. Once again demonstrating the access slaves had to the courts and their knowledge of the law, these suits became increasingly common during the 1760s and continued until the 1790s.Footnote 18 Nevertheless, it is important to remember that these cases freed individual slaves using preexisting legal maneuvers such as claims of trespass and back wages. These cases, besides establishing a precedent that enslaved people could sue their masters and win freedom, were relatively ineffective at helping end slavery as an institution. Moreover, there are no records of freedom suits in Boston from that period because the British occupation forces took the Suffolk County (where Boston is located) civil and criminal court records from the 1760s and early 1770s with them when they evacuated in March 1776.

We can, however, examine a case close to Boston. In 1769, James, an enslaved man belonging to Richard Lechmere, a merchant in Cambridge, Massachusetts, sued his master in the Middlesex County Court of Common Pleas (civil court). James found a white lawyer, Francis Dana, to represent him and in his suit accused Lechmere of trespass, claiming the merchant “assaulted […] him took & imprisoned & restrained him of his Liberty & hold him in Servitude”. Instead of demanding his freedom outright, however, James wanted to be paid £100 in damages and back wages. That sum was much higher than James's market value and put Lechmere in something of a bind. He could always allow the case to work its way through the courts and possibly win, but if he lost, he would have to pay his already recalcitrant bondsman an exceptional amount of money. In short, freedom would be cheaper than paying back wages. In this case, Lechmere pleaded not guilty in the lower court and won, namely because the court upheld Lechmere's right to hold James as property. When James and Dana appealed, however, the merchant gave up, freeing his bondsman and giving him £2 in return for James dropping the suit.Footnote 19

Perhaps the most important aid to enslaved Bostonians finding freedom was the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. When promulgated, the document laid the groundwork for the end of slavery. Indeed, the very first part of the constitution, Article I, Part 1, declared “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights”. Since the ratification of the constitution, historians have largely agreed that the drafter of the document, future American president John Adams, himself a lifelong opponent of black bondage, meant to undermine the institution of slavery in the Bay State. The first historian of slavery in Massachusetts, Jeremy Belknap, made the explicit connection, noting in a published letter to St. George Tucker of Virginia that Article I, Part 1, was meant to “establish the liberation of the negroes on a general principle, and so it was understood by the people at large”.Footnote 20

Regardless of whether or not the “people at large” interpreted the constitution of 1780 in that way, it did not really matter to enslaved people who saw an opportunity. There was a sharp uptick in the number of freedom suits and important court decisions, most importantly Commonwealth v. Jennison (1783) where Massachusetts Chief Justice William Cushing, in his instructions to the jury, declared slavery was “wholly incompatible and repugnant” to the Massachusetts Constitution.Footnote 21 While the case was not as widely publicized or important as historians once thought, it nonetheless gets us in the minds of leading Massachusetts jurists, who by the mid-1780s believed that the law did not protect the rights of slaveholders.Footnote 22 This transformation opened the door to any enslaved person who could bring a suit to find their freedom. Yet, many slaves did not even bother going to court. In a letter to Jeremy Belknap, Samuel Dexter, a political leader during the revolutionary era, explained that after hearing about the constitution of 1780, “one negro after another deserted from the service of those who had been their owners, till a considerable number had revolted”. A few “were seized and remanded to their former servitude”, Dexter continued, but would then sue and win their freedom. Dexter bluntly explained the consequence of these actions: “Thus ended slavery in Massachusetts”.Footnote 23 Empowered by the constitution of 1780 and using the mobility and legal knowledge they learned as slaves, the 1780s were a moment of self-emancipation.

Yet, this abolition was not without consequences. Most tellingly, the end of slavery in Boston, both because of the effects of the American Revolution and changing attitudes towards race and bondage, seriously disrupted black life in the town and ultimately displaced many of the formerly enslaved. Many found freedom by simply absconding, joining the Patriot army or navy with or without the permission of their masters, or running away to the British and exchanging service to the Crown for freedom. But it was not all positive. The chaos of occupation and war destroyed black families; freedom struggles caused many masters to sell them away to extract one last bit of wealth and changing labor and race relations meant that many enslaved people could not practice artisanal trades and looked elsewhere for work.

One of the leading causes of disruption and displacement of Boston's black population was the British Army's occupation of Boston following the 1773 Boston Tea Party. Between the occupation itself and, after April 1775, the Continental army's siege of the town, large numbers of Bostonians left. Many took their slaves with them, undermining the communities and families created by the black population. A good example of this can be seen in the letters of Josiah Quincy, a merchant and politician from Braintree, Massachusetts. Quincy spent considerable time in Boston and had an enslaved woman, whose name is never revealed, who married a slave, Sharper, belonging to Enoch Brown. Under normal circumstances, Sharper and Quincy's enslaved woman would have had plenty of time to interact and spend time together when Quincy was in Boston. But these were not ordinary times. Writing to James Bowdoin, the leader of the Patriot Massachusetts Provincial Congress that coordinated the Siege of Boston, in December 1775, Quincy, in a “grateful sense of the faithfull service of my black female servant”, enquired after Sharper. According to the politician, the woman had not heard from her husband in over two months, despite “diligent enquiry”. Even worse, despite belonging to Enoch Brown, Sharper was not residing with his master-in-exile, but rather with Colonel Ebenezer Sproat of the Continental army. Bowdoin, in his reply, noted he had met with Colonel Sproat and that Sharper had been for a “considerable time on a trading journey” to southeastern Massachusetts and had returned to the army's camp in Cambridge.Footnote 24

The exchange between Quincy and Bowdoin is important for understanding the effect of war and occupation on black life in Boston. On the one hand, we see the sundering of a black family and an already difficult situation given most enslaved husbands and wives lived apart in Boston – where spouses lost all communication with one another. Moreover, Sharper presents an interesting example. He was very similar to other enslaved Bostonians in that he was highly mobile, seemed to work on his own, and lived away from his master. Yet, his home under occupation, Sharper traveled further than normal, all around eastern Massachusetts to a variety of different towns and army encampments. Nobody found this situation unusual, most likely because it was an extension of the slavery that already existed in Boston. Within this continuity, however, came change. The military shaped Sharper's post-occupation life, providing him a place to live and his trading mission was most likely to procure supplies for the soldiers besieging Boston. It removed the enslaved man further and further from his family and the life he knew before the Revolution. While we do not know the fate of Sharper (or his wife), his association with the military was quite common and would shape black life in the years to come.

As Sharper's story suggests, many enslaved men from Boston served in the military, providing ample opportunity to leave home. While figures for Boston and Massachusetts are not available, in neighboring Connecticut, twenty per cent of the black heads of household listed in the 1790 United States census served in American army.Footnote 25 Again an outgrowth of the mobility they experienced as slaves, the relatively widespread acts of joining a campaign or serving on board a ship brought massive changes to black lives. While many were loyal soldiers, in some cases, service was a way to escape. In January 1778, American Commodore Samuel Tucker wrote to the lieutenant of the Boston-based frigate Boston demanding the officer look for and “Apprehend […] Two Negro Men who belong to the Ship” that absconded, most likely seeing the navy as their chance to run away from servitude.Footnote 26 Whether through loyal service or escape, the military presented slaves an opportunity to throw off the yoke of bondage.

Like the black Bostonians who served in the Continental army, many also served the British in their attempt to quell their rebellious colonists. Historians have intensively studied these Black Loyalists in recent years.Footnote 27 Most of them escaped to British lines where they pledged support to the Crown in exchange for liberty. Thousands evacuated with British forces, mostly from New York City, following the war and settled in Nova Scotia, London, and further afield. Unlike American forces, the British accepted – often reluctantly – most people who appeared, meaning women, children, and the elderly in addition to able-bodied men who found freedom with the British. Records, including the Book of Negroes, a register of African Americans who evacuated with the British, demonstrate that many black Bostonians found their way to New York City and pledged their support. Most interesting was Pompey Fleet, a skilled printer. A “Short & Stout” twenty-six-year-old, Fleet escaped his master, Patriot printer Thomas Fleet Jr, or as the clerk euphemistically stated, “left him”, during the “Evacuation of Boston” in March 1776.Footnote 28 Fleet's case indicates that black Bostonians saw the British as offering the opportunity for freedom denied them by American authorities.

Although service in the American or British armies caused many black Bostonians to leave the town altogether, it was largely voluntary, and slaves would have understood the consequences of their service. Other forms of displacement were more insidious. Coinciding with the Imperial Crisis, many masters in Boston began to sell their enslaved men and women out of the colony. This trend continued all the way through the 1780s and early 1790s. Part of it was economic. First the recession following the Seven Years’ War and then the chaos of the Revolution disrupted Boston's economy, slowing manufacturing, driving down wages, and disrupting overseas trade.Footnote 29 Yet, ideological factors also have to be considered. By the mid-1760s, African slavery had come under assault across the British empire, but particularly in Boston, the center of resistance to the post-1763 imperial reforms.Footnote 30 Famed orators such as James Otis made slavery a special target in speeches, while newspapers ran opinion pieces condemning slavery, sometimes by enslaved and free black people.Footnote 31 Such agitation possibly served to shame masters. One way of absolving that guilt was through sale, which would get rid of the problem entirely. For the more unscrupulous, black activism, such as freedom suits and petition campaigns, strongly signaled that slavery was coming to an end. Instead of risking their valuable property in a court case, which by the 1780s masters were guaranteed to lose, many took the initiative to sell their enslaved men and women. Either through shame or greed, the result was the same: a nearly three-decade sell-off that decimated black Boston.

Evidence for selling out is largely circumstantial, but there are a few clues to how it happened and its effect. Bills of sale from merchants provide some clues as to how masters sold their slaves. Some transactions were straightforward, such as when Boston tobacconist Simon Elliot sold his enslaved woman Peggy to Archimedes George of Jamaica in 1769.Footnote 32 Given that many Boston masters were tradesmen or not part of slaving networks, however, merchants with overseas connections seem to have served as intermediaries and facilitated the commerce. We can see this in a 1772 letter of Virginia merchant and planter Benjamin Harrison to Boston merchant William Palfrey. Harrison served as Palfrey's agent in the Old Dominion and the men had long been business partners. As part of their commerce, Harrison agreed to sell a slave belonging to a Mr Crequi of Boston.Footnote 33

Often sent by merchants to Canada, the Caribbean, or the American South, selling out had serious social consequences. Again, solid numbers are hard to find, but qualitative evidence offers some clues. In 1787, Massachusetts minister Peter Thacher told abolitionist Moses Brown that there were “many instances of the negroes being kidnapped & privately conveyed away to Canada where they were sold for slaves”. Neighboring Connecticut, which passed a gradual emancipation law in 1784, faced similar sales. Jonathan Edwards Jr, son of the famous revivalist, remembered after the passage of the act, he knew a man “employed in purchasing Negroes for exportation”. Likewise, Rhode Island banned selling slaves out of the state in 1779, suggesting it was a problem there as well.Footnote 34

These sales had a chilling effect on black life. Evidence of the uneasiness comes from notary books. In 1789, a free black man named Charleston approached Boston notary Ezekiel Price and had the notary record his manumission certificate. Interestingly, however, Charleston was not manumitted in 1789, but rather twelve years earlier in May 1777.Footnote 35 The gap between manumission and recording suggests that Charleston feared being sold away and wanted a copy of his manumission certificate on file, which would also provide Charleston more evidence in case he ever had to engage in the habeas corpus suits used by free blacks to protect themselves from being sold.

Economics and ideology provided plenty of impetus for masters to sell their slaves away, but the very nature of slavery made this practice feasible and facilitated the sale of enslaved Bostonians. As historian Trevor Burnard reminds us, slavery was economically advantageous for three reasons. Not only did enslaved people provide labor free of charge, but they were an investment that generally appreciated in value over time and, in a world of labor shortages, slaves could always be readily sold for cash.Footnote 36 Given the relatively early date of Boston's abolition, there were still plenty of labor-starved economies across the Atlantic looking for enslaved workers. Moreover, many of the skills acquired by enslaved Bostonians proved appealing to potential buyers. These skills are why the records are replete with references to slaves and free blacks being illegally sold to Canada. Mostly sent to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, many black Bostonians would have been employed in the emerging port cities of Annapolis, Halifax, and Saint John. Settled by tens of thousands of Loyalists, both black and white, during and after the War of Independence, these ports were bustling centers of economic and military activity by the mid-1780s. Townspeople, in desperate need of skilled labor, turned to many different sources of slaves, but particularly to New England given that many of the settlers in Atlantic Canada had ties to the region and understood its system of enslavement.Footnote 37 In short, the same skills that helped generate autonomy under slavery helped to create misery and dislocation during emancipation.

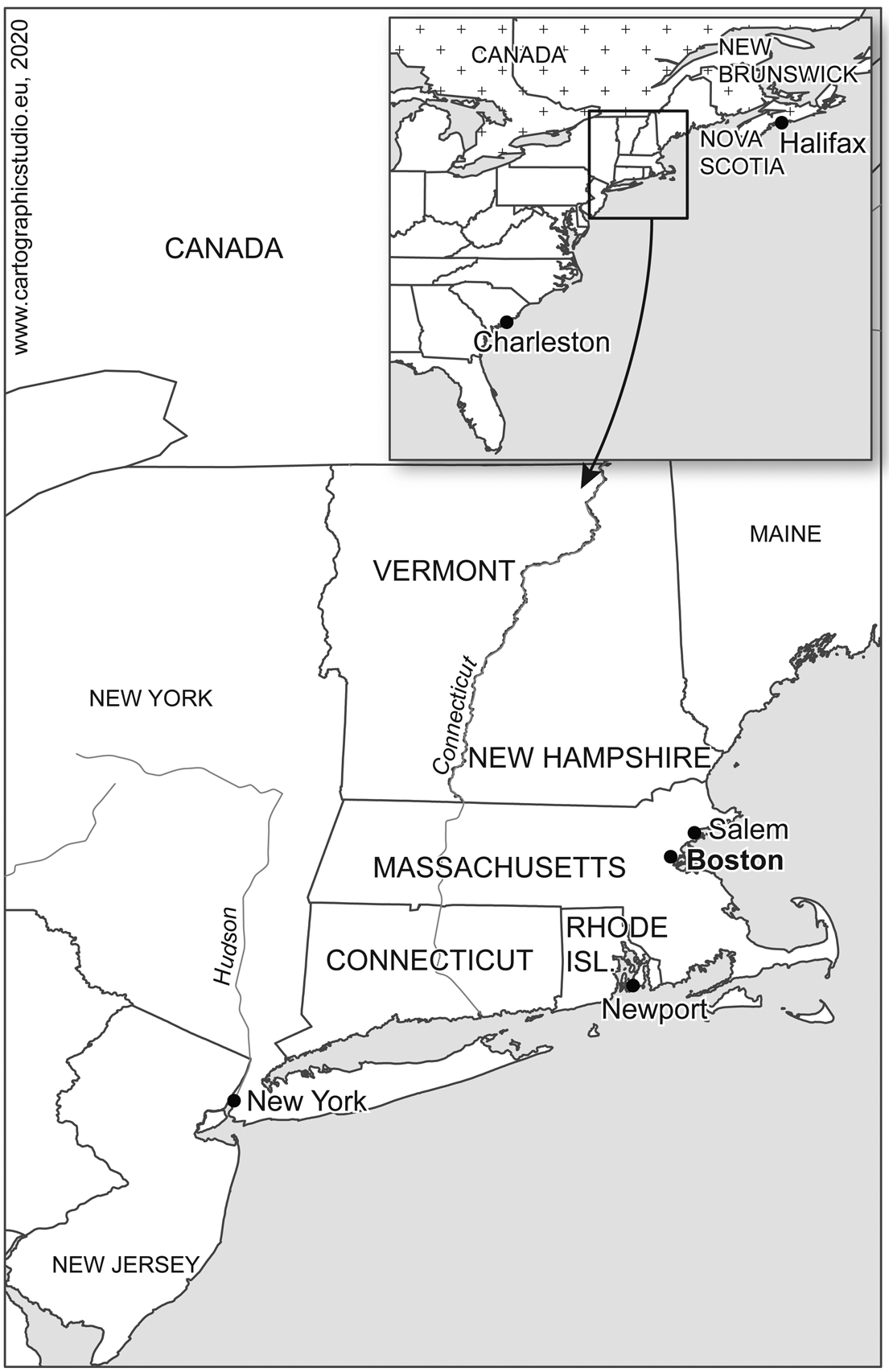

For those not relocated by war or sold away, the changing nature of Boston and New England's economy after the American Revolution further decimated the town's black population. The same skills that aided enslaved people in resisting slavery made them a target for changing notions of race and class. Much of this economic change can be linked to the collapse of New England's rural economy (Figure 2). By the 1750s and 1760s, in long-settled parts of the region such as eastern Massachusetts, the land began to give out, but the population continued to grow. Too little good land and too many people ultimately caused the agrarian economy to suffer as crop yields declined and the farmers who remained turned their land over to livestock on tiny plots that often did not provide for their subsistence. Young farmers faced two options. First, they could head to the frontier, both north and west, to build new farms on fresh land. Others began moving to larger towns and cities, especially Boston, looking for employment.Footnote 38 This mass movement into urban areas created, for the first time in American history, a surplus of unskilled white working people, or in other words, solved the labor shortages that drove the expansion of slavery in Boston.Footnote 39

Figure 2. Map of Southern New England, ca. 1777.

As poor whites flooded into Boston during the last quarter of the eighteenth century, they began to lay claim to the skilled and semiskilled jobs that had been performed by slaves. Indeed, they demanded them as a sort of right and were willing to use political pressure and threats of violence to achieve their ends. In a letter about the end of slavery in Massachusetts, then Vice President John Adams, rarely one to discuss class issues, described his take on emancipation. Adams blamed the end of slavery on the “multiplication of labouring white people” who believed that they should not have to compete with slaves for work. “Common people”, Adams continued, “would not suffer the labour, by which alone they could obtain a subsistence, to be done by slaves”. Had the labor market not changed to favor them, Adams predicted “the common white people would have put the negroes to death, and their masters, too, perhaps”.Footnote 40

Coinciding with the rise of a politicized and racialized white working class, racial attitudes towards enslaved Africans and free blacks, especially regarding their labor, began to change. If slavery made people of African descent “natural” workers, then freedom rendered them worthless and “unnatural”. Without legal bondage and the disciplinary violence of their masters, blacks could not expect to be productive and were thought to be lazy, idle, and shiftless. By the 1780s, you could still find Boston's few remaining slaves working in various industries, but, given these attitudes and the violent competition from white workers, free blacks performed the most menial of tasks and usually under coercive conditions. Moreover, outside of a few activist judges, neither the town of Boston nor the state of Massachusetts offered much protection from these attitudes as they capitulated to the white working class and many of those in power believed these ideas themselves.Footnote 41

LEGACIES

Ultimately, the legacy of abolition in Boston was the disappearance of black Bostonians over the course of a generation. Between the chaos of war, kidnapping, and changing labor markets, freed people disappeared from the town altogether. This disappearing act raises two important questions that will be the focus of this section. First, what happened to Afro-Bostonians? An analysis of both demographic data and the experiences of the town's former black residents help to better address this question. Second, how do we reconcile this legacy with the fact that Boston became a center of the American abolitionist movement in the 1820s? As we will see, these two factors went hand-in-hand as the black exodus allowed white Bostonians, many the descendants of slave owners, to wash their hands of Boston's slavery. Most importantly, much like abolition, the town's unique brand of slavery shaped the legacies of emancipation in Boston and the post-slavery lives of black Bostonians.

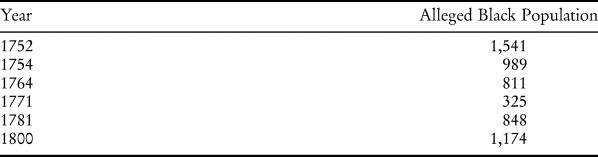

Tracking the number of black Bostonians in the colonial period is near impossible. In 1752, for example, town selectmen counted 1,541 enslaved people, but just two years later, the colony of Massachusetts's “slave census” enumerated only 989 slaves.Footnote 42 Later colonial censuses and assessments are even worse, with one from 1764 noting there were only 811 slaves in Boston and another from 1771 listing only 325.Footnote 43 These numbers are not accurate. The purpose of the censuses of 1754 and 1764 and the assessment of 1771 was to figure out tax rates for households in Massachusetts. Since slaves were taxable property, masters hid them from census takers or lied about the number that lived in their households. Nevertheless, a general downward trend in the black population is apparent by the 1770s, although not as dramatic, as shown by these census returns.

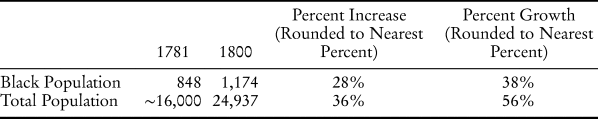

Post-independence demography also shows the downward spiral and the beginnings of recovery. The two most important figures are in 1781 and 1800. In the former, town records indicate that 848 blacks lived in Boston, nearly half the number that lived there during the 1750s. By 1800, the black population had grown by twenty-eight per cent or 326 people to 1174. Yet, this figure is deceptive for two reasons. First, much like poor whites, in the 1790s and 1800s, there were many free blacks wandering around looking for work. Census takers in 1800, then, captured a static picture of a large-scale population movement through the town. Confirming this fact is that between 1800 and 1850, Boston's black population grew at a slower pace (nine per cent per decade rather than fourteen per cent) from 1,174 to 1,999. Second, the black population grew at a much slower rate than the white. In 1781, Boston's total population was roughly 16,000, but it grew to nearly 25,000 by 1800, a fifty-six percent increase compared with thirty-eight per cent for the black population. Indeed, although the black population grew between 1781 and 1800, its percentage of the population fell from about six per cent to four per cent (see Tables 1 and 2).Footnote 44

Table 1. Black population of Boston based on official census and tax records, 1752–1800.

Sources: see notes 42, 43, and 44.

Table 2. Black population growth vs. total population growth in Boston, 1781–1800.

Sources: see notes 42, 43, and 44.

Colony/statewide and regional data also show an interesting trend. During the middle decades of the eighteenth century, Massachusetts's black population almost doubled, from 2,150 in 1720 to 4,075 in 1750. Yet, over the next three decades, the population only grew from 4,075 to 4,822 in 1780. Although there was a net increase in the black population of Boston, the anemic growth – only increasing by sixty-eight people between 1770 and 1780 – suggests disruption.Footnote 45 Indeed, birth rates among blacks remained relatively high and there were few epidemics during this period. Likewise, New England as a whole witnessed similarly low increases in the black population. Connecticut's black population only grew at 0.6 per cent between 1790 and 1850.Footnote 46

Perhaps the most telling population figures come from nearly two generations after the abolition of slavery in 1850. The 1850 federal census was the first to collect information on every member of households and enumerate birthplace. For that reason, we can glean the decline of Boston's black population during the era of abolition. In 1850, there were 1,999 blacks living in the town, only 458 greater than its colonial population zenith in the 1750s. Moreover, according to the census, only 44.8 per cent were from Massachusetts.Footnote 47 Unfortunately, the census did not break down origins by locality, but even if we accept that all those listed as being born in Massachusetts were from Boston, only 896 would have been native to the city. While the majority of the colonial black population was also foreign and not native-born, this number still suggests the demographic devastation wrought by abolition. In the aftermath of emancipation, the black population in Boston was so small that even after two generations of reproduction and immigration, it was only slightly larger than during the colonial era and numbered less than 2,000 souls. All these figures suggest is that between 1760 and 1800, Boston's black population declined between fifty and seventy-five per cent, only to very slowly recover over the next five decades.

While population figures give us a better idea of the total effect of abolition on black Bostonians, individual stories of post-emancipation life provide more concrete details about what happened to them after they left Boston. We can also see that even after leaving Boston, the experience of slavery in the town shaped post-emancipation lives. Pension and other records detailing service in the American army speak to this. Jamaica James, a slave from Boston who found his freedom serving in the 10th Massachusetts Regiment during the Revolutionary War, fought for nearly the entire duration of the conflict. Wounded at Bunker Hill in 1775, he then reenlisted in 1777 and stayed with the Continental army until George Washington disbanded it at Newburgh, New York, in 1783. Yet, James did not return home. Rather, he stayed in Orange County, where Newburgh is located, and lived there until he died. It is unclear what he did for the rest of his life, but when James applied for a pension in 1819, there were frequent references to his poverty and that he was unable to support himself in his old age, which was either sixty-two or seventy-seven depending on who testified. Combined with the men who testified on his behalf, many of whom were merchants engaged in commerce on the Hudson River, James's poverty suggests that he worked as a longshoreman on the riverfront until his body could no longer support physical labor. James, then, would have most likely pursued the same type of waterfront work he would have in Boston.Footnote 48 Despite deep differences of experience and the dislike that poor whites had of men like James, he, like the growing mass of rural landless men and women in New England, left the region and settled on the western frontiers of the growing nation.

As Jamaica James settled in the west, a slower process, one with roots dating back two generations, was playing out in the background. Ever since the 1740s, black men from Boston and surrounding towns had been marrying into local Indian communities. Not that demographics was destiny, but black Bostonians and local native groups seemed a perfect match for one another. More than sixty per cent of enslaved Bostonians were men, leaving many in search of mates. Allowed to marry by law, but only other people of color, they turned to Indian communities in eastern Massachusetts. These communities were disproportionally female as many of the men, obligated to serve the colony in its wars and also employed as fishermen and whalers, died during the eighteenth century. It was not foreordained, however. Already mobile, many black men sought out native brides for a variety of reasons. Most importantly, it was a calculation on behalf of the men. Certainly, love played a part in these matches, but for an enslaved man to marry an Indian woman meant his children would be born free with a claim to tribal land. Intermarriage accelerated in the post-Revolutionary years as many black Bostonians left the city for good.Footnote 49 Indeed, by the 1790s, many Indian communities in eastern Massachusetts were thoroughly mixed, leaving Reverend Stephen Badger of Natick, a town founded for Christian Indians in the seventeenth century and still containing a number of native inhabitants, to say that Indians “intermarried with blacks, and some with whites; and the various shades between these, and those that are descended from them”. This made it near impossible to distinguish who was black and who was Indian, causing consternation for white authorities seeking to quantify and delineate the races, which is exactly what blacks wanted.Footnote 50 For black Bostonians, Indian communities offered access to land, protection from slave traders, and, given native nations tended to welcome them, some semblance of stability. In short, escaping to Indian country offered them a chance to resist the degradation of post-emancipation life and should be seen as an extension of the appropriation of local institutions that occurred under slavery.

Whether they settled in Indian communities, led uprooted lives, settled on the frontier, or left the United States altogether, the result was ultimately the same: Boston's black population precipitously declined. Importantly, this disappearance influenced the budding antislavery movement in Boston. Effectively, it gave politicians and antislavery activists a blank slate on which to write their own history of slavery – and freedom – to better suit their ideological needs. Two legislative actions, less than forty years apart, help to illustrate this change. In 1788, as slavery was ending in Massachusetts, the legislature passed a ban on free black immigration into the state, fearing that large numbers of southern and West Indian freed people, looking for “free soil”, would settle in a place already dealing with growing poverty. By 1822, these attitudes had changed. In that year and in response to the Missouri Crisis, the Massachusetts assembly appointed Theodore Lyman, a legislator from Boston, to head a committee to examine the condition of free blacks in the state. In issuing his report, Lyman rewrote history, suggesting, unlike in 1788, just how removed he and other policymakers were from the experience of slavery. Lyman argued that since its founding in the seventeenth century, Massachusetts had been against slavery. As one historian describes it, Lyman believed antislavery was “endemic” to the people of Massachusetts. The existence of slavery there was more of a historical accident that the Revolution quickly rectified, making Massachusetts the “cradle of liberty”. Arguing in favor of a long tradition of liberty, the Lyman report overturned the legislation of 1788 and opened the door to large-scale free black immigration into Massachusetts, where they would be treated as equals (at least according to Lyman).Footnote 51

Central to sanitizing the history of slavery in Boston and Massachusetts was the nature of slavery itself. If the people of the Commonwealth had long favored liberty, then the slavery they had enacted could not have been that bad or that important. These tropes were especially common in the popular local histories of the early nineteenth century where antiquarians, digging around in their towns’ records, found much evidence of slavery. Rather than coming to terms with the fact that their forebears owned human beings, it was often written off as being a mild and benevolent bondage. Indeed, these histories depicted enslaved people as dutifully working beside their masters, performing skilled jobs in workshops, moving around town, and even going to church, i.e. the unique characteristics of slavery in Boston.Footnote 52 Antiquarians also sought to downplay the actual numbers of enslaved people, often noting that slavery was incompatible with the economy of the colony. In one history of Boston, for example, the author dismissed an account of the town's relatively large slave population, explaining its author had “written with but a shadow of regard for the truth”.Footnote 53 While it is easy to dismiss these local histories, they mattered for shaping how white people in Boston and Massachusetts perceived themselves and society. Unlike those in the South, Massachusetts had long been a place of freedom and against slavery. And the few slaves they did hold were treated well and even allowed to go to church. Never on firm footing, slavery died during the American Revolution. Such histories and the disappearance of black Bostonians allowed whites to paint themselves as the “good guys” in the struggle against the evil of slavery. In short, while enslaved people had to live with the experiences and legacies of slavery, whites were able to absolve themselves of the activities of their ancestors.

As the antislavery attitudes in early-nineteenth-century Massachusetts suggest, the legacy of slavery in Boston was a tragic one. Uprooted by war, racism, and a lack of work, many freed Bostonians left altogether. Available demographic data tell us that this caused a precipitous decline in the black population, while anecdotal evidence suggests just how severe and complete this disappearing act was. Deliberate or not, whites in Boston used this disappearance to rewrite history, promoting Massachusetts as a place of eternal liberty and dismissing slavery as little more than a blip in a long history of freedom. From the misremembrance to the post-Revolutionary labor markets that drove so many blacks out of the region, Boston's slavery influenced all of these processes. Envious of skilled black labor, many whites forced blacks into menial work or forced them to find work elsewhere. Already mobile, leaving for the frontier or roaming the countryside was an easy path forward. Finally, as settling in Indian communities suggests, freed blacks continued to appropriate local institutions to resist the degradation that came with their race.

The nature of slavery profoundly shaped abolition and its legacy in Boston. In this urban context, slaves were highly skilled in trades, mobile, and had knowledge of local institutions, namely the law and religion, which they appropriated. Such a system of enslavement allowed slaves to carve out a space for themselves and find autonomy from the master class. It also equipped enslaved Bostonians to forge their freedom during the era of the American Revolution. Slaves petitioned the government, sued their masters, or simply absconded. Yet, this freedom came at a price. It decimated Boston's black population by displacing them. Intricately linked with the War of Independence, many slaves and free blacks joined the Continental army or the British never to return home. Masters saw the writing on the wall and sold their slaves away, while the rise of racism and a changing labor market devalued black labor and drove many from Boston in search of employment. All told, at least half of Boston's pre-Revolutionary black population disappeared, scattered to the far corners of the new United States and Atlantic world. Ironically, the skills, mobility, and knowledge of the pre-Revolutionary slave population laid the groundwork for the post-Revolutionary diaspora. At the same time that Boston's black population reached its nadir in the 1790s, whites began crafting an image of an eternally free Boston, the cradle of American liberty. Making slavery an insignificant part of Boston's history, by the 1820s they transformed the town into a center of American abolition and welcomed a new generation of runaway slaves and freed blacks from the South and West Indies.

While Boston's slave population was relatively small compared with the centers of plantation agriculture in the Americas, this post-emancipation disappearing act is important for understanding abolition across the Atlantic world. Even in a place where enslaved people were skilled laborers and, for premodern people, well-educated, they still faced racial animus following their freedom. Black Bostonians, as in so many other places, were only valuable when their labor and productivity was the property of another. It was only when they voted with their feet and disappeared, removing the reminders of chattel bondage, that whites could envision a place of liberty and equality for all.