A large literature revolves around the contrast between voting for parties and voting for individual candidates, examining its consequences for voters, elites and the nature of representation (see, for example, Carey and Shugart Reference Carey and Shugart1995; Colomer Reference Colomer2011). A core argument suggests that intra-party competition induced by open ballot structures boosts non-policy types of representation (see, for example, André, Depauw and Shugart Reference André, Depauw, Shugart, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014; Crisp et al. Reference Crisp2004). Policy-related deviations from the party line, on the other hand, are not regarded as a widespread form of appealing to voters (at least not in parliamentary systems of government). Reasons include preference homogeneity due to the sorting of politicians and voters into parties (Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel1993), party leaders' ex ante screening of candidates or ex post monitoring of representatives (see, for example, Bowler, Farrell and Katz Reference Bowler, Farrell, Katz, Bowler, Farrell and Katz1999; Carroll and Nalepa Reference Carroll and Nalepa2020), and voters' insufficient information about individual candidates.

Blumenau et al. (Reference Blumenau2017) recently introduced an alternative perspective: when an issue cuts across existing party lines and becomes salient to the public, open-list (as compared with closed-list) proportional representation (PR) may electorally favour parties that offer candidates with varying positions on the issue over parties that do not.Footnote 1 Their empirical evidence comes from a survey experiment in the UK, presenting respondents with a fictitious European Parliament election with four experimental groups that differ in the list type (open versus closed list) and information provision (yes versus no) on candidate positions regarding Brexit. Results suggest that the British Conservative Party would, indeed, gain votes at the expense of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) under open rather than closed lists when information on candidate positions is given.

The innovative study by Blumenau et al. (Reference Blumenau2017) points to an important, and so far overlooked, research problem. It has two limitations though. First, the theoretical argument remains vague with regard to the underlying mechanism. The authors suggest that voters may have an expressive motivation, where the ‘attractiveness of the parties’ matters under closed lists but the ‘attractiveness of the candidates’ is decisive when open lists are used (Blumenau et al. Reference Blumenau2017, 811). However, while open-list systems allow individuals to vote for a candidate, it is hardly plausible that they make party-level factors irrelevant for voters' choices. It is questionable that only the ‘attractiveness of the candidate’ matters under open lists.Footnote 2 Our formal model clarifies how voters take into account party-level factors and candidate position, suggesting that the chosen candidate is expected to alter the position of their party. Based on the model, we arrive at more general predictions than did Blumenau et al. (Reference Blumenau2017). At the individual level, they expect ‘voters who have preferences close to a mainstream party on one dimension, but close to the niche party on a cross-cutting dimension, to be most likely to change party when moving from closed to open lists (assuming that the candidates of the mainstream party differentiate)’ (Blumenau et al. Reference Blumenau2017, 821). While both their and our argument generate the same implications regarding advantaged heterogeneous parties, we point out that if voters are more or less indifferent between the two parties, it is voters near the midpoint between the two parties who could be swung under open lists. In addition, if the homogeneous party is preferred on other grounds, switching occurs even for ideal points to the left of the midpoint.

Second, while their argument is compelling, the focus is on a single case: Brexit politics in the UK. This prompts the question as to whether the results can be generalized in empirical terms. Therefore, we replicate the survey experiment in a different context, focusing on immigration policy in Germany. During the European refugee crisis, mainstream parties faced an immigration-sceptic electorate while being internally divided over the appropriate level of immigration. This contributed to the success of a new, populist, right-wing party: the Alternative for Germany (AfD). Under the German mixed-member system with closed lists, the AfD successfully contested mainstream parties on the immigration issue. We argue and present evidence that an open-list system would reduce the electoral threat that the challenger party poses to established competitors. In addition, the same mechanism should, in principle, be at work on the left side of the political spectrum. The Greens, as the cohesive pro-immigration counterpart of the AfD, may lose pro-immigration voters to other parties under an open-list system, though the effect might be – and, in fact, is – weaker. (The Greens' policy position resonates with fewer voters overall, it differs less from the status quo, and the closest competitor parties have very similar stances.)

A Spatial Argument on Voting in Open versus Closed Lists

We use a canonical model of vote choice, where voter utility is a function of the voter's spatial proximity to the party on a single salient issue dimension, and a summary term that encompasses judgements of voters about non-policy characteristics of parties, as well as spatial proximity on other dimensions of the policy space.Footnote 3 Our main interest lies in analysing whether having a choice among individual candidates with distinct policy positions (here, a pro- or anti-immigration stance) affects which party is supported. Let λ and γ be indicators for the contexts we are interested in: λ = 0 refers to a closed-list system where votes are cast only for parties; λ = 1 captures an open-list environment. Policy-based voting for individual candidates requires information on candidates beyond what voters know about the parties these candidates belong to. We therefore contrast a situation where voters know the pro- or anti-immigration stance of candidates (γ = 1) to a situation where no candidate-specific information is available so that the party label is the only cue (γ = 0).Footnote 4 Voter i's utility from casting a vote for choice alternative j, that is – with slight abuse of notation – a party list in a closed-list system or a candidate fielded by a party under open list, then, is:

where x i is the voter position on the relevant issue, here immigration, y j is the position of the party on immigration, and Δj = γλz j is the expected change in the party's position on immigration (as perceived by the voter) when a pro- or anti-immigration candidate gets elected in an open-list system. The term v ij combines both the voter's evaluation of the party/candidate in terms of non-policy attributes and salient positional issues other than immigration.Footnote 5 Parameter β > 0 is the weight of spatial proximity on the immigration dimension.

In closed-list environments, voting for candidates is not feasible so that the relevant reference is the party position, y j. Under open list, building reasonable expectations about how parties change with electing specific candidates into office requires information about candidates' policy stances or other relevant candidate attributes. Therefore, if there is no such information, we expect Δj to be 0. It should be noted that, in addition to impacting on spatial proximity, the mere fact that voters receive information on candidates' stances on immigration policy may also impact on the salience of the immigration dimension (a larger β) or party valence.Footnote 6

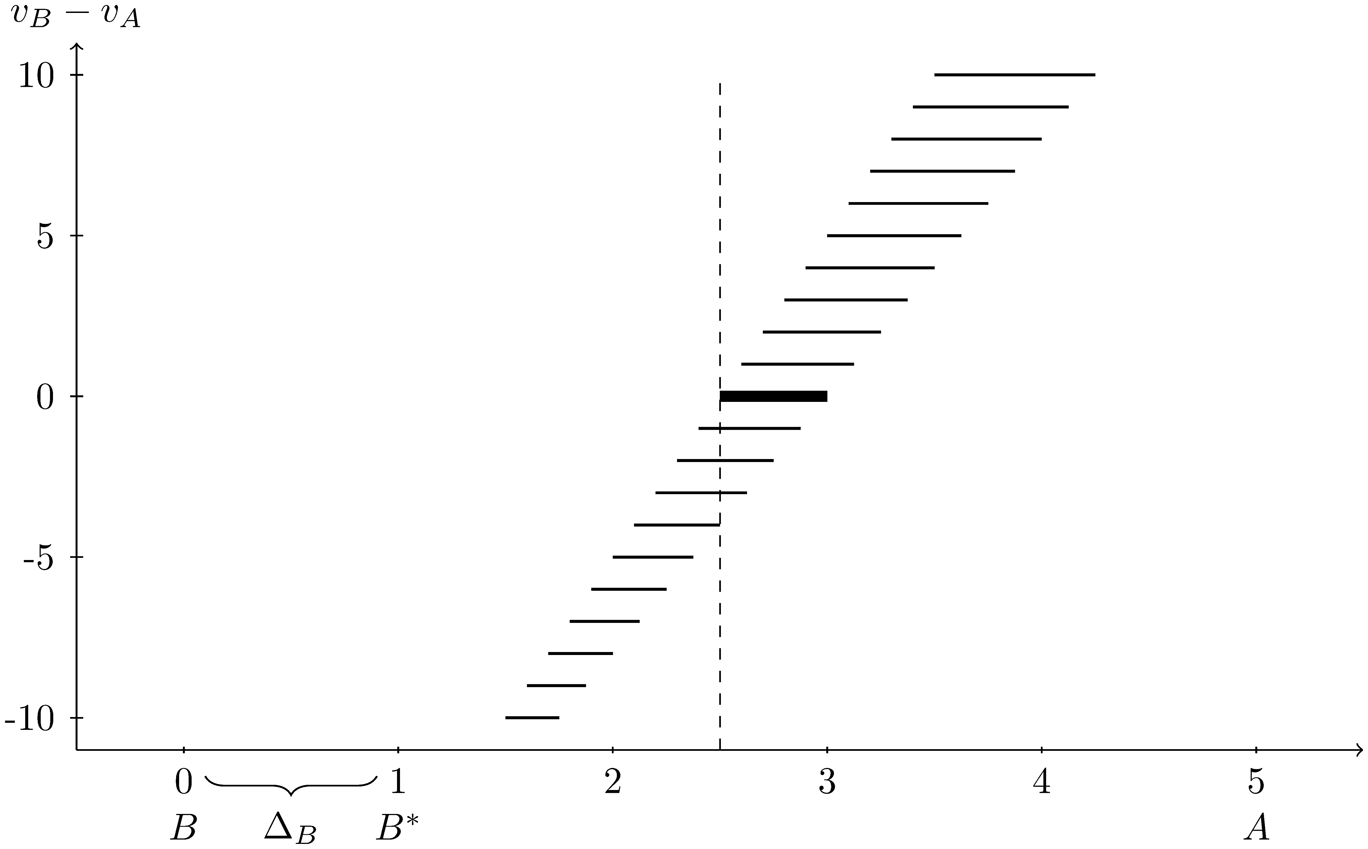

We assume that individuals vote for the party or candidate that maximizes their latent utility. Hence, the sets of ideal points that support a vote for one or another choice option are separated by a single point of indifference on the issue dimension.Footnote 7 Now, what is the effect of moving from a closed-list to an open-list system? Figure 1 shows an example of voters deciding between a cohesive party A and a party B with heterogeneous positions. B* indicates the perceived position of party B, as shifted by ΔB, when a right-leaning (here, anti-immigration) candidate gets elected in an open-list system. The line segments show the range of ideal points of voters with incentives to switch votes from A to B under open-list ballots as a function of the summary evaluation advantage of B. If neither party has an advantage, the cut points are exactly at the midpoint of the choice options (here, at 2.5 for A and B, and at 3 for A and B*). Voters indifferent between the two parties in terms of the summary evaluation v ij will thus cast a vote for A under closed lists but for B under open lists if, and only if, their ideal point is in the range of 2.5–3 (the bold line segment).

Fig. 1. Heterogeneous party B wins votes from cohesive party A when lists are open.

Note: Intervals (x-axis) show ideal points of voters with incentives to switch votes from A to B under open-list ballots as a function of the overall advantage of B (y-axis). The dashed line shows the midpoint of the two party positions. The salience parameter β is set to 1.0.

Heterogeneous parties may not only attract voters in the middle of the space. In fact, if heterogeneous party B has an advantage (disadvantage) in terms of v ij, it can attract voters with ideal points closer to party A (party B). Figure 1 also indicates that the range of ideal points of potential vote switchers gets small when B is not very attractive. Thus, while the exact location of the switching interval generally depends on how salient the issue is (β), voters who are, by and large, indifferent between A and B have incentives to switch from A to B if their ideal points lie near the centre between the two parties (whatever β is). It should also be noted that the range of ideal points gets larger when the expected change ΔB gets larger (not shown in Figure 1). In particular, this would be the case if voters expect a specific candidate to have a strong influence on the policy direction of the party.

To sum up, we provide three observable implications of the argument, the first of which is identical to Blumenau et al.'s (Reference Blumenau2017, 811) core expectation:

Implication 1: Parties with a heterogeneous candidate pool may gain votes from parties with a homogeneous candidate pool in an open-list setting as compared to a closed-list setting.

It is worth emphasizing that we deliberately say ‘may gain’. Whether or not a heterogeneous candidate pool results in shifts in aggregate vote shares also depends on the voter distribution, that is, how densely populated the switching intervals shown in Figure 1 are.

Implication 2: The above effect is stronger if voters associate candidate votes under open-list ballots with larger shifts of party positions.

Implication 3: Individuals who are close to indifferent between their two top-ranked parties A and B are likely to change their vote from homogeneous party A to heterogeneous party B if their policy preferences are near the midpoint between those of A and B.

We next discuss how these implications translate into hypotheses in the specific context of our experiment.

Case-Specific Expectations

The theoretical arguments outlined earlier refer to the general case of an issue that allows (potentially new) competitors with a clear stance to challenge internally divided mainstream parties. Immigration politics in Germany following the recent European migrant crisis is a fitting case. The far-right populist AfD, founded in 2013 as a Eurosceptic party, shifted its focus to immigration and presented itself as the sole alternative to established parties, propagating a clear and unambiguous immigration-sceptic position. At the same time, for electoral and other reasons, most other parties were characterized by substantial internal divisions over the level of immigration, family reunification and related issues. The only exception was the Greens, who were fairly unified in support of asylum-friendly policies.

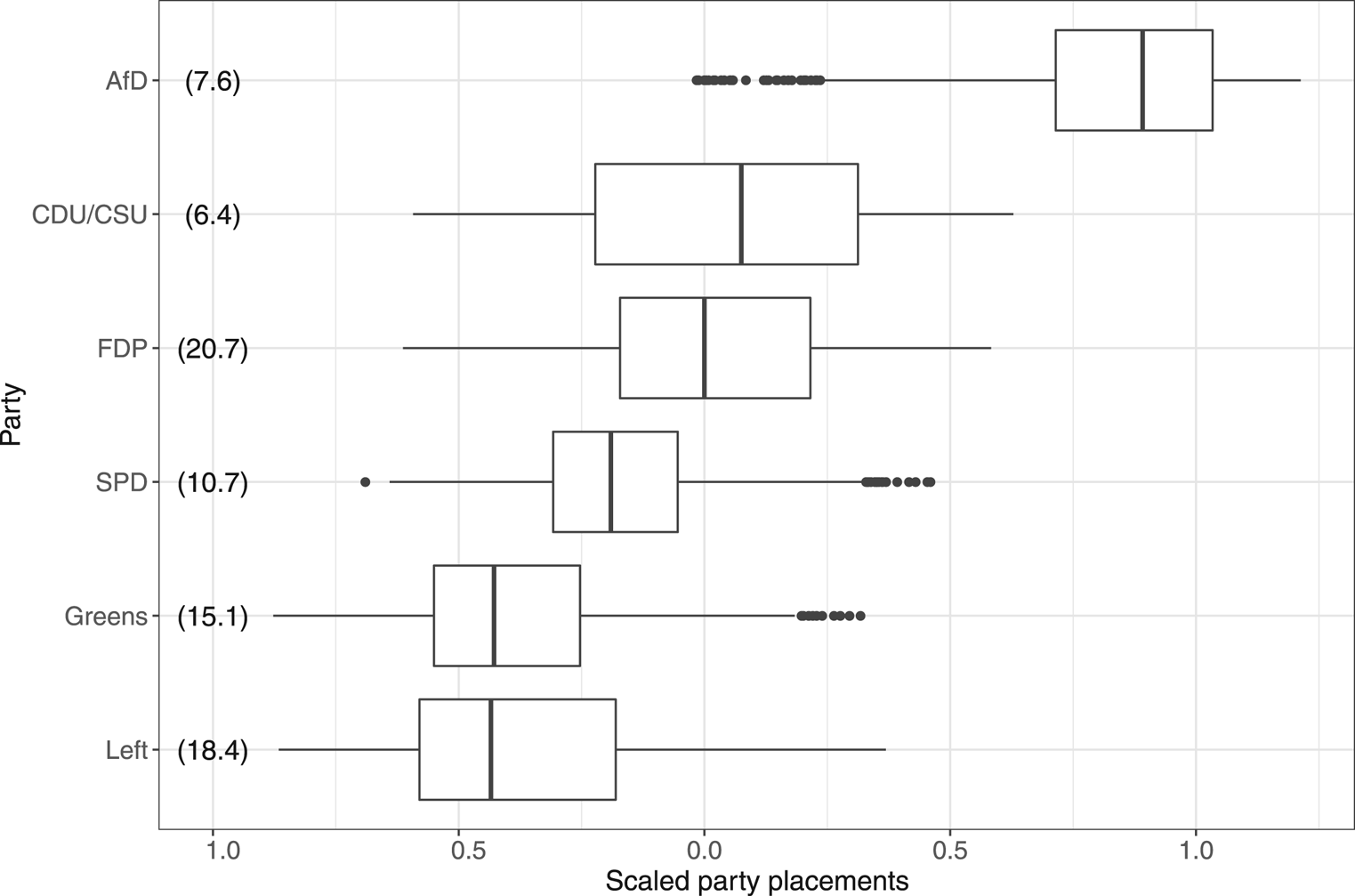

We first consider the prevalence of attitudes towards immigration in the public using data from a 2017 post-election survey that asked respondents to place both themselves and major parties on an eleven-point scale ranging from ‘facilitate immigration’ to ‘restrict immigration’. As Figure 2 shows, the AfD separates itself from the other parties with a decidedly immigration-sceptic view, a perception that is shared by a large part of the respondents. Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) and Liberals (FDP) are perceived as considerably more moderate. However, respondents differ greatly in their perception, hinting to the possible intra-party heterogeneity of views in these parties. On the left-hand side, the far-left party Die Linke (Left) and the Greens occupy the most liberal positions (with almost identical median perception). However, citizens vary somewhat more when it comes to locating the Left than the Greens, possibly because politicians from the Left, including prominent parliamentary party group leader Sahra Wagenknecht, have also expressed concerns about immigration.

Fig. 2. Perceived party positions on immigration.

Note: The figure shows box plots of perceptions, re-scaled using Aldrich-McKelvey scaling. Boxes are based on N = 1,431 respondents (those who place all parties and themselves, and have variation in party placements and positive scaling weights). Figures in parentheses are percentages of missing placements among all N = 2,112 respondents. ‘CDU/CSU’ refers to CSU in Bavaria and to CDU elsewhere.

Source: 2017 German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES 2019).

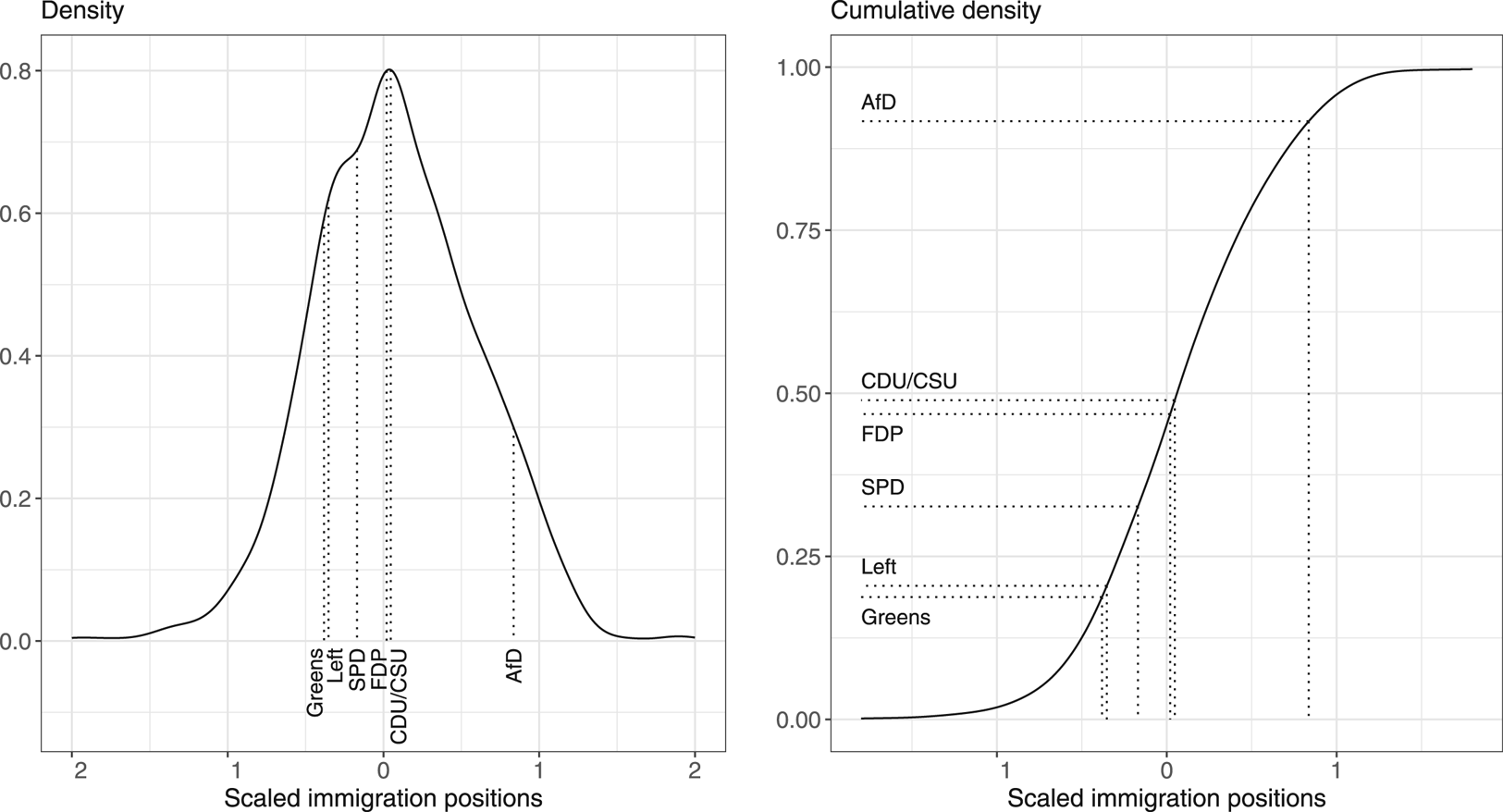

The far-right AfD has the potential to attract votes with its clear anti-immigration platform. Approximately 50 per cent of respondents place themselves to the right of the CDU/CSU position (see Figure 3). The large gap between the CDU/CSU and the AfD suggests that under an open-list ballot, the CDU/CSU might (re)gain votes from the far-right AfD: there is a sizeable segment of the electorate with positions falling between the CDU/CSU and the AfD who – if those are their top two preferred parties – could be inclined to vote for an immigration-sceptic CDU/CSU candidate under an open-list ballot. While vote switching is most likely for the closest party on the immigration dimension, our argument also allows for vote switching from the AfD to other parties, provided that the other party has a heterogeneous candidate pool and, together with the AfD, is one of the two top-ranked parties.

Should we expect a similar pattern on the left-hand side of the political spectrum? While the Greens present themselves, and are perceived as, a party with a fairly unified liberal position on immigration, only a small proportion of the electorate are located between the Greens and the Social Democrats (SPD) or the Left (see Figure 3). Hence, we expect smaller differences in vote shares between closed and open lists on the pro-immigration side.

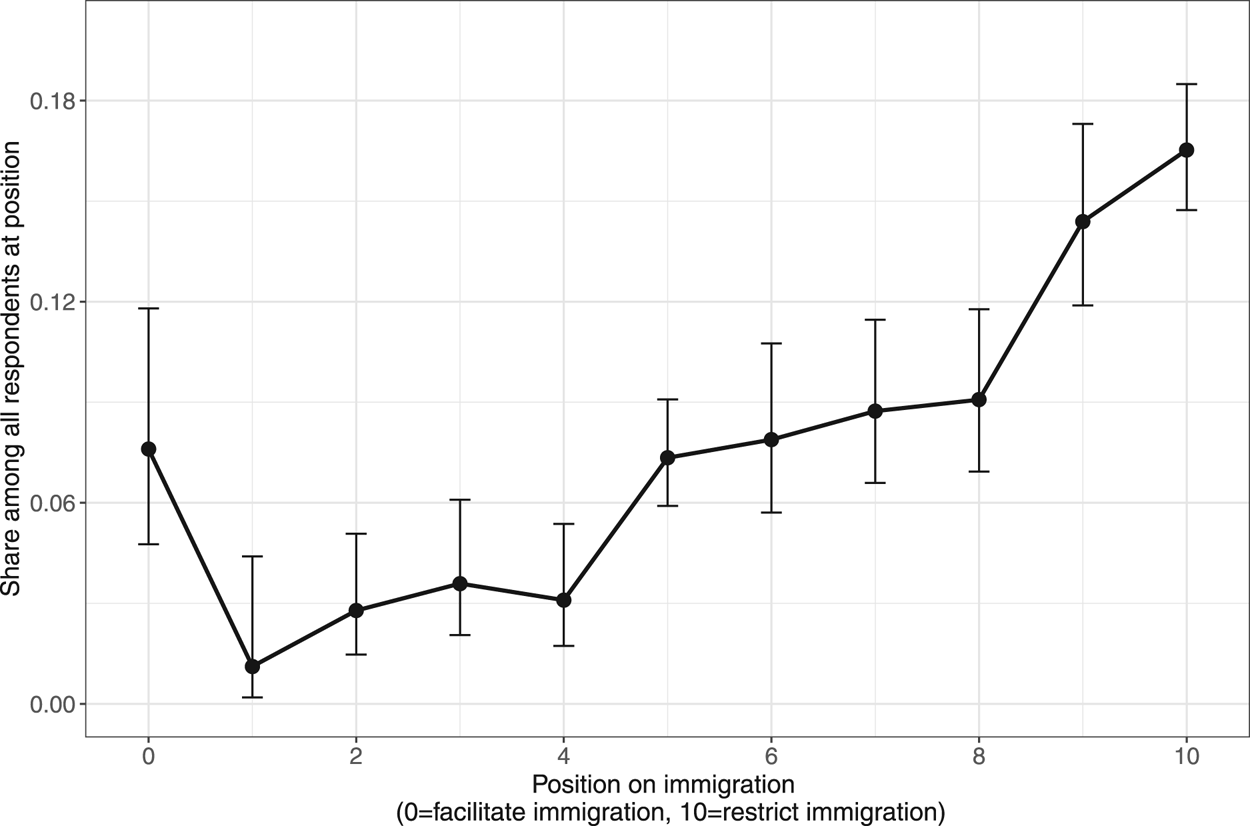

While the AfD also has roots in anti-elite and populist sentiments, this does not contradict our argument as our theoretical model subsumes migration-unrelated motivations under the baseline utility v ij. For instance, a protest appeal of the AfD may contribute to its overall advantage among some voters. We would still expect an effect of the ballot structure as long as there is a sufficient number of voters who do not strongly favour the AfD for non-immigration reasons (that is, v B − v A is not small). In fact, there is a significant number of, by and large, indifferent voters targeted by both the CDU/CSU and the AfD (see Figure 4). In the survey experiment, we asked respondents to provide an overall rating of parties on a standard eleven-point scale. We use these scale values to proxy the summary evaluations v ij. In the sample, approximately one out of ten respondents can be classified as indifferent between the CDU/CSU and the AfD.Footnote 8 More importantly, this share is larger among more immigration-sceptic voters, with about 17 per cent of respondents on the right end of the spectrum rating both parties similarly. For the Greens, even though there is a much smaller pool of pro-immigration respondents in total, about 21 per cent can be classified as indifferent between the Greens and the SPD, and the share of indifferent respondents is higher at the pro-immigration end of the policy space (see Figure A2 in the Online Appendix). Taken together, these analyses suggest that immigration policy is a good test case for the general arguments outlined earlier.

Fig. 4. Share of respondents indifferent between the CDU/CSU and the AfD, by self-reported immigration position.

We can now restate the model implications from earlier, tailored to the context of our empirical case:

Hypothesis 1: On aggregate, the AfD will receive fewer votes and the CDU/CSU more votes under open lists than under closed lists.

Hypothesis 2: The effect stated in Hypothesis 1 is stronger when attention is drawn to the notion that parties take into account the electoral support of candidates when deciding about policy direction.

Hypothesis 3: From among the voters who are indifferent between the AfD and the CDU/CSU, vote losses by the AfD, and vote gains by the CDU/CSU, are largely due to voters whose immigration positions lie near the midpoint of the two parties.

We expect weaker effects at the pro-immigration end of the scale, where immigration-friendly voters may be drawn away from the unified, immigration-liberal Greens when they are offered the option to vote for a pro-immigration candidate of some other party:

Hypothesis 4: The aforementioned effects are weaker for the case of the Greens losing votes to the SPD or to the Left under open lists.

Research Design

We embedded the experiment in an original survey. The survey was fielded between 11 January and 19 February 2019, with 6,600 respondents recruited from an online panel, applying quotas on age, gender, education and region.Footnote 9 Comparing the distribution of respondents' party preferences in our study to the distribution in surveys using random sampling shows that our quota sample matches the German population (see Online Appendix B1; also see descriptive statistics in Online Appendix A1).

In the experimental design, we randomly assigned respondents to one of five treatment conditions before eliciting their vote in a hypothetical German federal election (list-tier vote).Footnote 10 The first four treatment conditions constitute a 2 × 2 design crossing over closed- versus open-list ballot and information versus no information on a candidate's position on the immigration issue. All respondents were presented with lists of four candidates for each of the six major German parties. We varied whether respondents select party lists only as such (closed-list ballot treatment) or a specific candidate within party lists (open-list ballot treatment). In the information treatment, we exposed respondents to an introductory screen with information about the policy issue of family reunification of asylum seekers.Footnote 11 Respondents received candidate positions on family reunification printed on the ballot (information treatment) or not (no information treatment). Candidates either held more lenient or more strict positions. The AfD and Greens were presented as homogeneous, with four strict or four lenient candidates. All other parties were shown as internally divided (for more detail, see Online Appendix B2).

A fifth treatment condition mirrored the open-list-with-information setting but with an added emphasis frame on the policy consequences of a candidate vote. It highlighted that political parties will consider the electoral performance of specific candidates in their future policy decisions.

To increase context validity, respondents were shown a ballot that resembled the actual election ballot regarding title and introduction, the vertical ordering of parties, and the listing of four candidates of each party. We randomly ordered parties to avoid systematic order effects; we showed four candidates to balance policy positions in parties; and we listed candidates vertically such that ballots resembled an open-list design, minimizing ballot design effects. The 24 candidate names were randomly combined from garden-variety first and family names, while ensuring that they did not refer to persons of public interest. We used twelve female and twelve male names, and we restricted randomization so that no list exclusively comprised male or female candidates. To conduct within-respondent analyses, we asked respondents to voice their electoral preferences for a second time, keeping information levels constant but changing ballot design. Figure 5 shows how the closed lists without information and the open lists with information were displayed to respondents.

Fig. 5. Screenshots of the treatment conditions ‘closed list/no candidate information’ (top) and ‘open list/candidate information’ (bottom) as displayed to survey respondents (excerpts with two of the six parties shown only).

The Effect of List Type and Information on Vote Choice

We evaluate the effects of ballot type and information on vote choice using ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions. Using linear probability models seems plausible in this case and comes with the advantage that coefficient estimates can be interpreted as changes in percentage points. Closed lists without information are the baseline.

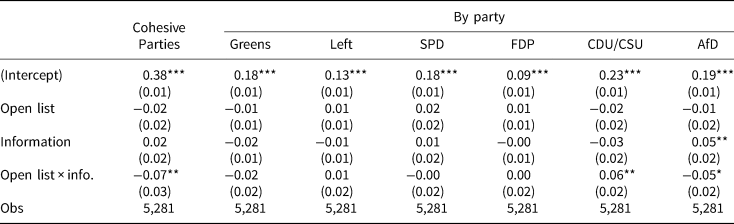

We first assess treatment effects in the first round of the experiment. Table 1 provides supporting evidence that open-list ballots have a negative effect on the vote shares of cohesive parties. Considering cohesive versus incohesive parties first (column 1), the interaction effect indicates that for cohesive parties, the adverse effect of open lists is stronger for informed, as compared to uninformed, respondents (−0.07 [p = 0.006]). A second question is whether the vote shares of (in)cohesive parties are smaller (larger) under open lists when voters are aware of parties' (in)coherence. For cohesive parties, the effect is sizeable (−0.02−0.07=−0.09 [p = 0.001]). When looking at results by parties, we observe a similar effect for the AfD. For the Greens, the effect is negative but weak.Footnote 12

Table 1. Effects of ballot type and information on vote choice (OLS)

Notes: Unstandardized regression coefficients and standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

We have insufficient statistical power to differentiate the effects for the AfD and for the Greens. Whether to expect identical effects for different parties (parties that differ in their government status, intra-party organization and so on) in the first place is a theoretical question beyond the scope of this letter. From among incohesive parties, the CDU/CSU profits substantially. It should be noted that, as expected, we find no effect of open lists per se (that is, without information), and information per se has a statistically discernible effect only for AfD vote shares. This is plausible, as providing respondents with information on family reunification may have increased the salience of the immigration dimension in vote choice (β in equation 1; see also Online Appendix C1).

An analysis of within-individual voter transition patterns provides additional support for our arguments. We capitalize on having asked survey respondents twice which party they would vote for, varying the electoral system and keeping information levels constant. Figure 6 shows how respondents who opted for the AfD (left panel) and the Greens (right panel) in the first round (with a closed-list setting) voted in the second round (with an open-list setting). While transitions are rare in the no-information setting, they are frequent when candidate positions are revealed. In the latter case, only 72 (77) per cent of voters remain with their first-round AfD (Green) party choice in the second round. For the AfD, a substantial share of voters shifts to the CDU/CSU (ten percentage points) but also to the Left, FDP and SPD (five to six percentage points each). For the Greens, we observe a shift of approximately nine percentage points to the Left and of six percentage points to both the CDU/CSU and the SPD.Footnote 13 Online Appendix C2 provides evidence that experimenter demand effects are unlikely to represent an alternative explanation of this pattern.

Fig. 6. Within-respondent analysis.

Notes: The figure shows the share of cohesive party supporters (AfD/Greens) under closed lists (first round) who transition to another party under open lists (second round).

In summary, both aggregate and individual-level evidence clearly supports the argument that closed-list voters of cohesive parties switch to candidates from heterogeneous parties who share their policy preferences in an open-list setting with candidate information. This provides strong support for Hypothesis 1 and weaker support for Hypothesis 4.

Finally, we report that the emphasis frame – telling survey respondents that the electoral performance of candidates will influence policy making – does not change aggregate voting behaviour compared to open-list PR under information as such (for details, see Online Appendix C3). That is, we find no support for Hypothesis 2.

The Effect of List Type and Information by Voters' Immigration Position

We next evaluate the third implication of the model. We proposed that among voters who are largely indifferent between a cohesive and an incohesive party (ranked in the top two), we see the largest shift in vote choice among respondents who are close to the midpoint of the immigration positions of these parties. To test this empirically, we focus on voters who rank the AfD (Greens) and any other party as their top two preferred parties.

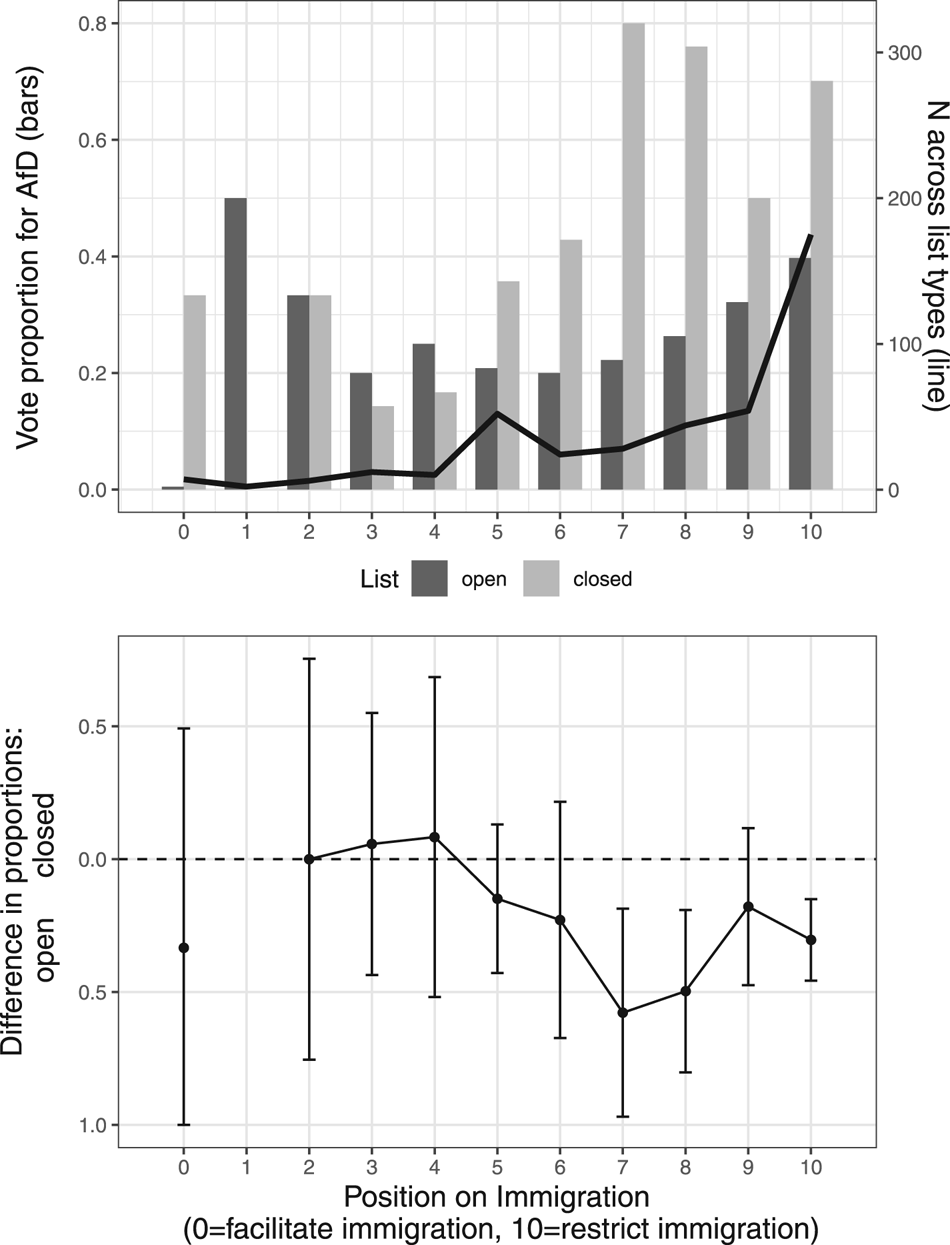

Figure 7 shows this analysis for voters indifferent between the AfD and any other party. First, as expected, the majority of these respondents are immigration-sceptics (with self-placements above 7 on the 0–10 scale; see the line in the upper panel). Secondly, grey and black bars represent the proportion of the AfD vote by immigration position in this group (upper panel). The open-list treatment makes a difference for respondents between immigration position 5 and 10. Notably, this difference is strongest for the moderately restrictive immigration positions of 7 and 8, as expected (lower panel).

Fig. 7. Treatment effects for individuals who are indifferent between the AfD and some other party, by immigration position (experimental groups with information, only).

Notes: In the upper panel, bars show the proportion of indifferent individuals voting for the AfD by list type (there are no cases at 1.0 in the closed condition); the line represents the total number of indifferent individuals at each scale point. The lower panel displays differences in proportions between open and closed lists, with 95 per cent confidence intervals (χ 2 test).

We mirror this analysis for respondents who are indifferent between the Greens and some other party. Online Appendix C4 presents tentative evidence that similar effects apply to pro-immigration respondents. However, the difference between the treatments fails to reach conventional levels of statistical significance. Whether the same mechanism holds on the left side of the political spectrum would have to be tested with more statistical power and/or an issue that resonates more strongly with such voters. Overall, the finding that near-indifferent voters switch parties, especially when they hold moderately extreme immigration views, provides support for Hypothesis 3.

Conclusion

This letter makes two contributions to the analysis of spatial voting under open-list compared to closed-list PR. First, we introduced a simple spatial model to reveal voter incentives to switch parties when candidate choice affects future party positions under open-list PR. Secondly, focusing on immigration politics in Germany and support for the AfD, we find strong empirical support for two of three model implications.

There are several worthwhile avenues for further research. For example, the formal model could allow for individual voters having varying perceptions of candidate influence on the party position. It is possible that these beliefs systematically vary with their own ideal point or that citizens consider which candidates within a party other voters will support. In empirical terms, it would be interesting to examine whether post-electoral party positioning in open-list systems reflects the views of politicians with strong personal vote results (for effects of electoral performance on intra-party careers, see André et al. Reference André2017; Folke, Persson and Rickne Reference Folke, Persson and Rickne2016).

The findings have practical implications for institutional design. With societies becoming more differentiated, issues cutting across traditional party lines are likely to appear more frequently. In an open-list system, parties can react by offering a range of policy options on such issues through different candidates, whereas in a closed-list system this can happen at best indirectly. List type may have an impact on party choice when voters are confronted with a heterogeneous mainstream party and a homogeneous challenger. Prominent examples, like the True Finns, Flemish Interest or Swiss People's Party, demonstrate that this constellation frequently occurs in electoral systems with candidate voting.Footnote 14 It would be interesting to study how variation in mainstream parties' renomination strategies affects the electoral performance of challengers.

Our study also informs the more specific debate on how mainstream parties may deal with anti-immigration, populist challenges (Dahlström and Sundell Reference Dahlström and Sundell2012). Does becoming tougher on immigration impede (Bale Reference Bale2003; Van Der Brug, Fennema and Tillie Reference Van Der Brug, Fennema and Tillie2005) or facilitate (Arzheimer and Carter Reference Arzheimer and Carter2006) the success of populist right-wing parties? Our findings reinforce the idea that mainstream parties face a difficult trade-off. Moving rightwards, for example, by offering candidates with immigration-sceptic positions, can attract voters. However, if this also increases the salience of the cross-cutting dimension, others may be lost to the challenger party.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000417

Data Availability Statement

The data, replication instructions, and the data's codebook can be found in the Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WUTLH8

Author contribution

The authors contributed equally to this letter and are listed in alphabetical order.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions. Liam F. Beiser-McGrath, Jack Blumenau, Gracia Brückmann, Andrew Eggers, Dominik Hangartner, Dennis Kolcava, Denise Laroze and Michael L. Wicki provided excellent feedback on an earlier version of this letter. We also thank audiences at Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zurich and the European Political Science Association 2019 Annual Conference for their thoughtful comments. Jan Menzner provided valuable research assistance.

Financial Support

Thomas Däubler acknowledges funding from the German Research Foundation (grant DA 1692/1-1).

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.