“It [is] not satisfactory, [ . . .] that commercial values are allowed to influence in such a way that the credibility of the quality of the tests—and thereby also the credibility of the protection of life, health and property—is reduced.”Footnote 1

So stated Bertil Löfberg, an expert appointed by the Swedish Social Democratic government, in 1974 before the introduction of official central testing sites for product control. The 1974 bill created a new, holistic structure for testing corporate activities nationwide, with seven state testing sites each having a monopoly for a specified testing area.Footnote 2 Commercial interests were not considered appropriate in these control activities because they risked jeopardizing the credibility of the testing and its aim to protect consumers. Competition and market solutions for testing products would also risk giving citizens less insight, reduce equivalence across the country, and carry the risk that commercial interests would reduce public trust. Business interest in profit was framed as a clear opposition to consumer interest in the quality and safety of products. The suggested regime of control was justified with reference to the need to protect consumers from powerful corporations that would otherwise prioritize profits over consumer safety. In a time of growing mass markets for consumer products, the dominant view in Sweden and elsewhere was thus that consumer interests were conflicting with business interests.Footnote 3

However, only about two decades later, state regulation through testing sites was dismantled and replaced with market solutions. During the 1990s, the testing sites were gradually replaced with a new international model for organizing and regulating markets. This article traces how the business-consumer relationship was reconfigured and interpreted at different levels within the new regime of market control. How were potential credibility risks interpreted in the system once “commercial values” were allowed to influence quality control?

It has been suggested that the new international model for organizing and regulating markets, which in Sweden replaced national testing sites, is part of a neoliberal regulatory turn, not least because market actors are central in controlling compliance. The control model, which has been termed the tripartite standards regime (TSR),Footnote 4 started to expand in many countries by the end of the 1980s in connection to the publication of the first version of the ISO 9001 standard. The issuing of certificates based on this type of international standard, combined with accreditation as a control mechanism of certifiers, constitutes the foundation of the TSR. It is designed to work across national borders to facilitate trade, reduce uncertainty, and build confidence in markets.Footnote 5 Understanding the TSR and the exercise of power it entails are thus key for understanding the foundations of recent business historical developments.

Aim and Scope

By studying the new regime at three levels—the implementation at the state level, the practices of the Swedish accreditation authority (Swedac), and the booming certification market in the Swedish context—we show how the idea of a conflict between business and consumer interests evaporated in the TSR due to a recalibrated notion of the consumer. Instead of being protected from powerful companies, the consumer would rather, not to put too fine a point on it, be protected from the state. The new sovereign consumer, a neoliberal notion that had a major impact on decision making and political ideology from the 1980s onward, was thus seen as having been damaged by government regulations and protected by individual rationality and market efficiency.Footnote 6 We find a paradox here that needs to be developed further: an increased consumer focus in the general debate, but a reduced consumer influence in the actual work of organizing markets.

With this study, we add to but also problematize previous research that has declared the “birth of the consumer” in relation to standardization work. Some researchers have suggested that consumer interests became increasingly important when standards were developed from the 1930s to the 1950s, mainly at the national level, and in the 1960s and 1970s also at the international level, specifically around safety issues.Footnote 7 As already stated, we see a continued emphasis on the consumer in the neoliberal era from the 1980s onward.Footnote 8 In rhetoric, the consumer was definitely given a significant role, specifically through the opportunity to participate in international committees to influence the agenda of standard-setting as well as the contents of standards to fit consumer needs.Footnote 9 This picture is confirmed in our own studies; the Swedish government devoted considerable resources and specific support to consumer interests in the development of international standards, and was from an early stage engaged in building a national accreditation authority to monitor the certification firms with the purpose of safeguarding public interest.Footnote 10

However, the tripartite standards regime consists of three pillars, and when paying specific attention to the pillars of certification and accreditation and the relationships between various market actors involved in them—which have attracted less scholarly attention than the relationships between market actors in standard-setting—the picture looks quite different. The new market organization implied altered distances, interactions, and relationships among the state, businesses, and consumers (which were reconfigured into “customers”). This, in turn, had consequences for the previously institutionalized notion of a conflictual relationship between consumers and businesses that justified state intervention for consumer protection. We use the Swedish case to further explore the implications of the neoliberal shift for consumers by asking the questions: How and why did the notion of business-consumer relations change in the organization of the market of accredited certification?

We address our questions in three interrelated substudies. First, we examine the political context in which the Swedish market for management system certification was established in 1988. More specifically, we investigate public debates about the organization of control that took place in the mid-1980s (Substudy 1). We then examine how the national accreditation authority, Swedac, having the ultimate responsibility for the TSR at the national level, defined the certification that it was tasked to monitor and how it communicated and handled consumer interests from 1990 to 2015 (Substudy 2). Finally, we address the issue of the gradual replacement of the state national control system with a growing market for certification by mapping the Swedish certification companies and placing the market growth in a European context from 1990 to 2020. Against this background, we investigate how certification companies themselves articulated and justified their role in relation to business and consumer interests (Substudy 3).

Neoliberalization in the North

This article follows Jamie Peck and Adam Tickell’s suggestion to see neoliberalization as a process with national and local variations. This perspective allows for an analysis of neoliberalism as a longer process that paved the way for market logics in more and more societal domains, rather than mere implementation of ideological manifests and political reforms. Peck and Tickell have suggested a periodization of phases: first “roll-back” (i.e., de-regulation and dismantlement) and then “roll-out” (cases of re-regulation).Footnote 11 Consumer protection and labor law have been pointed to as two key legislative arenas that began to be dismantled during the roll-back phase.Footnote 12

Although there were also outspoken voices advocating neoliberal reforms in Sweden, many of these reforms—such as de-regulation, privatization, and marketization—occurred within, rather than in opposition to, the welfare state in a relatively quiet manner. Jenny Andersson has shown how neoliberal economic ideas were married with Social Democracy under the label “new economic ideas” already in the 1970s, playing into the party’s historical legacies of productivism and discipline. When new steering tools were introduced, they were interpreted foremost as neutral and pragmatic instruments and not as challenges to the Swedish welfare model: “Such changes in instruments carried ideational change well before the battle of ideas erupted in the political arena.”Footnote 13

The latter half of the 1970s in Sweden saw the beginning of a political change when liberal-conservative ideas increasingly impacted public discourse.Footnote 14 In 1976 a center-Conservative coalition took office, ending a more than forty-year-long Social Democratic governmental dominance. However, it was not until the early 1990s, with a new Conservative government and with Sweden facing a deep recession and budget crisis, a neoliberal roll-back phase intensified. Then, new solutions were considered necessary to reconstruct welfare more sustainably and cost-efficiently, and industrial competition was increasingly emphasized in relation to globalization. Also, economic-structural relations fundamentally changed when Sweden adopted a new macroeconomic policy and entered the European Union (EU).Footnote 15

Previous Research on TSR and the Consumer

The expansion of the TSR since the 1990s has attracted extensive scholarly attention, including analyses of its neoliberal underpinnings and implications in terms of unintended consequences, such as superficial compliance, escalating governance structures, and bureaucratization.Footnote 16 These developments have been analyzed as part of a third “wave” of standardization that differs from the two previous waves in several ways. The first two waves—from around 1880 to 1929 and 1930 to 1979, respectively—were built on a structure of national standard-setters that, over time, became members of international standardization organizations. Standards were justified not only as a means of enabling industrial coordination and growth (first wave) but also as a way of ensuring consumer protection by specifying functionality and safety criteria for consumer products (second wave).Footnote 17 The International Organization for Standardization (ISO), with Swedish engineer Olle Sturén as CEO between 1968 and 1986, reinforced consumer perspectives in the setting and use of standards in the last years of the second wave by establishing the ISO Committee on Consumer Policy in 1978.

During the third wave of standardization, which started in the 1980s, several international or global standard-setters were established, challenging the traditional ones. Standards of management systems—such as ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 specifying organizational structures and procedures for quality assurance—had a particularly strong impact. With the addition of the procedural standards focusing on various aspects of the management and organization of firms, lucrative standards-related businesses expanded rapidly during the third wave. These included both certification and accreditation organizations and a large number of meta-organizations (for standard-users, standard-setters, certifiers, accreditors), with the purpose of coordinating and establishing trust in these, often private, regulatory activities. Together, they merged into complex international and global networks of organizations.Footnote 18 With these developments, both the drivers and the language of standardization changed, becoming less about the social movement-like mission of societal improvement of the two first waves and more about commercial branding and customer orientation of a global standardization business.Footnote 19

The organization and history of standard-setters, which represent the first pillar of the TSR, have attracted extensive scholarly attention among social scientists, with analyses of their legitimacy, authority, and power.Footnote 20 There is also a growing literature in economic and business history on the role of standards as a way of organizing markets.Footnote 21 A small number of studies have focused specifically on the role of consumers in standard-setting, which is seen as both strong and weak. On the one hand, consumers were strengthened as a stakeholder group within international standardization during the twentieth century and have succeeded in placing questions and aspects of interest to consumers, such as social responsibility, diversity, sustainability, and fair work conditions, on the standard-setting agenda.Footnote 22 On the other hand, it has proved difficult for the few consumer representatives invited to actually influence the standard-setting work.Footnote 23 Consumers, often with scarce resources, have difficulty making themselves heard among large corporations. Additionally, given the structure of national membership and national votes in standardization organizations such as ISO, individual stakeholder groups, such as consumers and trade unions, are forced to agree to a “one voice” logic based on nationality, and thus tend to give up their own specific interests.Footnote 24

The market for certification, the second pillar of TSR, expanded considerably during the 1990s in what some label a “certification revolution.”Footnote 25 Research on this business is extensive, and certification is generally seen as a way of reinforcing the value of standards.Footnote 26 Many studies have been conducted from a critical perspective with the aim of problematizing certifiers’ neutrality, independence, and business interests.Footnote 27 Several studies on management system certification highlight unintended consequences, such as superficial compliance, “tick boxing,” and the production of mistrust.Footnote 28 Here, we build on the literature that has pointed out a latent tension in the TSR, as certification auditors are for-profit companies tasked to perform objective controls of their own clients.Footnote 29 Certification firms may, in this context, be understood primarily as consultants or business partners of companies that need help in adapting to standards while they also act as watchdogs for public interests.Footnote 30 What, more specifically, is meant by “public interests,” and whether consumer interests are explicitly included, is not clear, however, as studies of specific certification organizations, their historical roots, and legitimizing strategies are rare in the certification literature.Footnote 31

Accreditation, as the third pillar of TSR, is often discussed as a monitoring mechanism that has developed in response to the legitimacy problems in certification markets.Footnote 32 Historical research on accreditation is still in its infancy, with only a small number of studies on the emergence of these types of organizations.Footnote 33 The political side of TSR is most evident in the research on accreditation specifically or research targeting the entire tripartite standards regime. Here, scholars have highlighted TSR’s gradual transformation during the postwar period, with increasing neoliberalization and strengthened political support intended to create confidence in global markets and thereby facilitate world trade.Footnote 34 Although some studies situate accreditation in a historical perspective, noting the roots of accreditation in laboratory testing,Footnote 35 these studies lack analysis of the role and justifications of laboratory organizations—in which states often were involved—in regulating markets. However, the study by Ingrid Gustafsson on the establishment of the Swedish system of seven national testing sites in the 1970s stands out as an exception.Footnote 36 With a specific interest in analyzing the role of the state, she points out that there was, at that time, strong consensus in Sweden about the societal values of independent public testing being the responsibility of the state.Footnote 37 Here, we take Gustafsson’s study of the Swedish historical context and the active role of the state in forming and legitimizing a new global regulatory regime as a starting point to specifically investigate how and why the notion of business-consumer relations changed as the new regime emerged and became institutionalized in Sweden.

The three pillars of the control regime are best studied together because central power dimensions, such as those between consumers and producers, will otherwise be lost. In this article, we therefore examine two of the regime’s three pillars that have received the least attention in previous research: accreditation and certification.

Sources and Methods

Substudy 1, on arguments for and against a shift from state regulation to a private market for certification, is based mainly on analyses of the archives of a Swedish investigating government committee working between 1986 and 1988, with its final report published in 1988 and a complementary report published in 1989.Footnote 38

Substudy 2, on how the Swedish accreditation authority Swedac articulated its role and purpose in relation to both the certification market and the interests of end consumers, is based on statements made on its website and in its annual reports, with a selection of every fifth year between 1990 and 2017. Moreover, this substudy includes a full investigation of preserved documents from Swedac’s handling of complaints between 1991 and 2019 related to management system certification based on ISO 9001 and ISO 14001.

For Substudy 3, we used information on ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 certificates sold in Europe, together with descriptive statistics to illustrate the overall expansion of the market for accredited certification over time as well as to place Sweden in an international context. The accreditation registry from Swedac is also a key source in this substudy for tracing the firms over time.Footnote 39 We selected all certification firms accredited for management system certification between 1990 and 2015. The early certification business of SIS, the Swedish standard-setter, was also included in the selection, because it was identified through Substudy 1 as the first ISO 9001 certification provider in Sweden in 1988 (albeit acquired a few years later by a larger certifier). Annual reports from Bolagsverket (Swedish Companies Registration Office) for all firms have been collected for every fifth year between 1990 and 2015. Annual reports are complemented with ephemera from the firms, archived at the Swedish National Library. All saved ephemera from these firms have been studied for the period 1990 to 2018.

Substudy 1: Dismantling of the Swedish State System and Establishment of a Private Bureaucratic Regime

During the 1980s, both the Swedish state and the national engineering scientific community initiated a number of committees to investigate ongoing work in the EU on the launch of the New Approach in 1985 and developments in relation to quality management. As we analyzed their submitted material, we stayed attentive to discussions, arguments, and decisions not only about the establishment of the new control order but also about the dismantling or redefinitions of existing national control structures.

Replacing or Complementing Existing Testing Structures? Debates in the Mid-1980s

The Swedish governmental investigation into various forms of quality control was conducted between 1986 and 1988.Footnote 40 The purpose was to map the international developments within the control area and to evaluate implications for Sweden. The files we studied include reports, reflections, and conclusions on the use of quality systems and quality system certification as a means of creating trust for all types of market actors, framed as a way to overcome national bureaucratic procedures hindering trade across borders. Here, the New Approach—with standards, certification, and accreditation based on quality system thinking—was framed as a modern, efficient tool for the realization of the internal market of the European Union.Footnote 41

A global quality movement emerged in the 1970s and grew in the 1980s, putting questions about quality assurance high on the agenda. This movement was driven by the structural crisis of the 1970s, combined with increased bureaucracy from national safety regimes that were perceived as protectionist in times of increasing global trade. Inspiration was taken from Japan, where the idea of Total Quality Management (TQM)—a holistic way of thinking about quality—had been successfully implemented during the years of industrial recovery after World War II. One of the core ideas of TQM was that quality should be a basic concern in the design of products, in production processes, and in working organizations. TQM emphasized overall quality in manufacturing systems and processes rather than solely in final products.Footnote 42

The Swedish commission on testing and control also took inspiration from countries such as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. The launch of third-party certification against the British quality system standard BS 5750, an initiative taken by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the early 1980s, was particularly interesting to the Swedish commission. The purpose of the initiative was to improve the international reputation of British corporations, which was suffering from low-quality production.Footnote 43 However, this was not a problem experienced by the Swedish committee, who associated Swedish industrial production with high quality. The need for trust that was legitimizing change in the United Kingdom thus already existed in the national Swedish market as well as in the international one.

The concerns highlighted by the commission, and by interest groups linked to large Swedish manufacturing companies, tended to be about overcoming national bureaucratic procedures. The quality work in Sweden at the time had too narrow a focus on technical aspects of products, according the Byggforskningsrådet (Swedish Construction Research Council), an early interest group.Footnote 44 The idea of quality management was depicted in more positive terms, with references made to the success of the Japanese industry—“everything organized and ordered in its place”—to obtain good performance regarding both quality and economy.Footnote 45 The advantages of the new way of thinking were highlighted by the interest group, including the increased probability of obtaining a correct quality level at an early stage of a project, better coordination, lower costs, and improved conditions for risk evaluations. Disadvantages were reduced to one point: “the risk of overambition or too formal (bureaucratic) systems.”Footnote 46

Another argument put forward by several proponents of a new system was improved international trade. Sweden’s high industrial quality provided good conditions for international competitiveness.Footnote 47 Nevertheless, as a small country heavily dependent on exports, it was perceived as crucial to adapt to modern ideas about sources of competitiveness, such as TQM. Despite the fact that the United Kingdom had completely different experiences compared to Sweden, the United Kingdom was described as a model country that had managed to compete in the global market, thanks to “quality consciousness.”Footnote 48 Somewhat surprisingly, consumer perspectives were completely absent in the Swedish governmental investigations and in the information and campaign material from interest groups.Footnote 49

“We’re On Our Way Towards a Certification Bureaucracy”

In 1988, the ISO 9001 certification was launched as a pilot by the national standard-setting organization SIS—the first to conduct quality management certification in Sweden. This was done to expand its certification division, established in 1981, which only performed product certification up to this time. The launch followed a seminar given by SIS in 1986, at which central stakeholders were present. These included representatives from the state, quality professionals, and a few mid-sized manufacturers and consultancy firms—but no representatives of the consumer social movement. While consultants and mid-sized firms were clearly pushing for the development of accredited certification, both a few larger and a few smaller companies were resistant or remained hesitant. At the seminar, SIS reported that certification organizations in other countries had already been established in 1987 to perform management system certification, when the first version of ISO 9001 was published, and that these certification companies were planning to establish business units in Sweden as well.Footnote 50

The positives of ISO 9001 were highlighted mainly in relation to business interests, because it would improve the certified firm’s reputation in relation to both other organizations and its employees. And the advantages of third-party certification, when an independent intermediary conducted the audit instead of the clients themselves, were highlighted. The second-party audits, where numerous auditors came from client companies to check against various (often similar) company-specific requirements, had become burdensome for many firms. As argued by some smaller companies and a few consultants at the seminar, it would be much more efficient if certification was conducted by third-party professionals against a single recognized international standard. One government representative, Lars Ettarp, then undersecretary at the Labour Market Ministry, was supportive of the new, modern quality thinking and referenced its role in eliminating technical barriers to trade.Footnote 51

It is somewhat surprising that a few large corporations, including Electrolux, were hesitant about third-party certification. They argued that quality standards could be counter-productive by restricting quality to a certain level, and that third-party certification would risk the positive relationship of personal trust that characterized second-party audits.Footnote 52 The possible bureaucracy linked to third-party certification was also mentioned by other representatives of large companies in particular, as well as the risk that third-party certification would lead to new technical barriers to trade and weakened conditions for personal trust relationships. “It feels,” claimed a quality manager at a large Swedish company, “like we’re on our way towards a certification bureaucracy living a life of its own alongside technology.”Footnote 53

What is striking when going through the committee’s documents and their contact with interest groups is that the existing regulatory regime in Sweden, with state-run testing sites and laboratories, was seldom discussed, or even mentioned. Quality control with a focus on the testing of physical products was, however, often criticized by various actors for being too narrow, and quality system certification and accreditation were presented as promising forms of control. It is, however, not completely clear if the various actors involved in the process considered the new forms of market-based control as a complement to, or a replacement for, existing state control structures. What is clear in the sources is that consumer perspectives were seldom raised. One interviewee working for SIS’s certification business during the 1980s and 1990s made the following reflection about the assumed indirect relationship between quality management certification and end consumers: “One can say that the end customer . . . you know, we assumed that this ‘machinery’ that was provided [with quality system standards, third-party certification, and accreditation] was efficient to guarantee benefits to them.”Footnote 54

As a result of debates that arose within the government after publication of the 1988 government report, a complementary investigation was initiated in 1989 to analyze a few concerns in relation to the reinforced role of international standards and third-party certification in Sweden.Footnote 55 In the assignment for the second investigation, it was noted that private third-party certification had replaced state authority approvals in many countries, which resulted in a new role for the state: to guarantee that certification companies worked in a coherent way. The United Kingdom was held up as an example of state-controlled accreditation.Footnote 56 The second committee was, therefore, appointed by the government to see if something similar could be developed in Sweden. The main concern over the 1988 report was the possibility of various stakeholders to influence the standard-setting taking place at the international level. Here, finally, specific concerns related to the interests of consumers were raised, as well as those of the labor unions. The Swedish Consumer Agency also stressed that accreditation needed to be further investigated in order to assure coherency and quality of certification.Footnote 57

It is clear that the Social Democratic government, which held power in various constellations between 1982 and 1991, had a positive view of the new system for quality control based on accredited certification. However, the fact that they also stressed that consumers and labor unions should participate in standard-setting can be interpreted as a recognition of a potential conflict between business and consumer interests. There was also a potential conflict between two parallel systems—one under public law and one under private law.Footnote 58 In the early 1990s, the new Conservative coalition government terminated the state system, with its seven national testing sites, although a few laboratories continued to operate throughout the decade. The others were closed down, privatized, or acquired by multinational certification companies and entered into the management certification market. Sweden, like many countries worldwide, was thus subjected to a certification revolution, or rather a gradual adaptation to a new control regime.Footnote 59

A Prosperous Market with External Recognition to Serve a Higher Purpose

That the paradigm shift was more or less completed in the early 1990s can be symbolized by the 1992 SIS celebration of its seventy-year anniversary at a large meeting, under the title “Standard Unites Europe,” held at the Grand Hotel in Stockholm. In an archived program, the key to Europe’s internal market was described as implementing the use of international standards. Speakers at the meeting included the director and CEO of SIS; the Swedish Minister for Business, Industry and Innovation, Per Westerberg, from the Conservative Moderate Party; the chair of Ericsson; and the secretary general of the European Committee for Standardization (CEN).Footnote 60

In his speech, Westerberg stressed that standardization was especially important for highly developed countries like Sweden, which had a limited internal market and thus was dependent on international trade to stay competitive. Westerberg declared that he and the Conservative coalition government intended to combat the ongoing economic crisis with de-regulation, privatizations, and tax reductions, which the Moderate Party in the early 1990s framed as den enda vägens politik (the politics of the only way). This framing of the paradigm shift—from centralized state regulation to far-reaching neoliberal reforms—as the only possible way forward might seem drastic, but by 1995 some of these changes, such as the revision of competition law, were also harmonization measures required to enter the European Community.Footnote 61

The regime shift from national public regulation to the TSR in Sweden was heavily dependent on arguments of business interest. If business and international trade were successful, this would benefit both the nation’s competitiveness and the consumer. Even when the Social Democratic government stressed the importance of consumer and labor movement influence on standard-setting, the conflict between business and consumers was never fully articulated. It is also important to stress that the question of consumer interests was raised in relation to the first pillar of the TSR, but not to the second or third. This means that consumer interest was understood mainly in rule making, but not in relation to how auditing of rule compliance was ensured or how potential sanctions were organized. It was assumed that the benefits for consumers would follow once standards were set in a process in which consumers were represented.

It might seem obvious what business interest entails, but a closer look shows that not all businesses at the time were eager to support this new form of neoliberalized market control. Even though some of the larger firms warned that the enforcement of international ISO standards would risk lower quality and third-party certification could bring more bureaucracy, both governmental officials and SIS representatives claimed that TSR was necessary for the Swedish industry to survive tougher global competition.

Substudy 2: State Agency Legitimation of the Role as National Chief Accreditor in Sweden

In 1991 Statens mät- och provanstalt, the former state institute for measuring and testing, was transformed into Swedac under the leadership of Lars Ettarp, who had left his former position as undersecretary at the Labour Market Ministry and had become highly engaged in promoting the role of standards and accredited certification in Sweden and within the EU. With the change, authority was transferred to Swedac to act as accreditor of certifying bodies. Moreover, in 1994 Swedac was given the responsibility for coordinating market surveillance in Sweden.Footnote 62

A quick visit to Swedac’s website is enough to see that today, it presents itself as a watchdog for the interests of citizens and consumers. In one of Swedac’s promotional videos on its site, the purpose of accreditation is presented as being to instill “trust”:

Trust is what holds a society together. That is our conviction. [. . .] That the mobile phone you bought in Thailand is made to last. That safety tests are carried out at our nuclear power stations. That your broken arm is properly X-rayed at the hospital. [. . .] That the roller coaster stays on the rails. So that people can be daring and safe at the same time. So that we can take things for granted and live our lives as normal. That is our mission. We call it accreditation and quality assurance. But in the end, it’s all about creating a safe society made up of people who can trust each other. Quite simply, it’s about making the world a little better.Footnote 63

The focus on trust and safety for citizens, and consumers in particular, is however not as visible in Swedac’s historical material, such as their annual reports. As with the proponents of TSR in Substudy 1, in its first fifteen years of operation (1991–2005), Swedac highlighted the positive impact and significance of accreditation mainly for international trade. In preparation for Sweden’s accession to the European Union, Swedac prioritized trade policy.Footnote 64 The benefits of accreditation were said to provide “competitive advantages, primarily in new markets,” and Swedac emphasized market gains for companies.Footnote 65 In the mid-1990s, Swedac likewise stated that accreditation probably had “its greatest positive effects in international trade.”Footnote 66 Thus, in its early period, Swedac’s customers—in the form of certification companies—were at the center of its presentations—while citizens and consumers were not articulated as stakeholder groups for which Swedac had a watchdog role.

Over time, however, the emphasis on market values came to be complemented by emphasis on safety as a non-economic value. In addition to “competition on equal terms” and the removal of “technical barriers to trade,” Swedac worked for “safe products,” according to its annual report in 2000.Footnote 67 Here, wording from the old state-run test sites is recognizable, such as working for “safety in terms of life, health and the environment.”Footnote 68 In this respect, a rather abstract social and public interest was written into Swedac’s assignment: as a watchdog for “society.” Swedac’s guiding star, as it noted in 2005, was to “provide Swedish society and Swedish industry with a world-class service.”Footnote 69 “Maintaining credibility among customers [e.g., certification companies] and the general public [e.g., citizens and consumers] is a central part of the assignment.”Footnote 70 However, when Lars Ettarp, Swedac’s first director-general, looked back on twenty years of accreditation in 2005, business policy and foreign trade were always at the center: “During 20 years of legislation according to the New Approach, we have achieved many benefits for the free trade and mobility of goods and services.”Footnote 71

Swedac’s operations were—and still are—focused on companies. However, since 2010, citizens’ lack of awareness about Swedac itself has been formulated as a problem and caused the authority to direct several communication efforts toward the public: “When it comes to accreditation, citizens primarily come into contact with the business through Swedac’s customers or customers’ customers. [. . .] Swedac has the goal to increase public awareness of Swedac.”Footnote 72 Its efforts to inform the public can be seen as their legitimizing its operations in the eyes of the public; Swedac perceives itself also as a watchdog for consumers. A related legitimization effort is to spread the conflict-free worldview that Swedac presents on its current website where everyone is said to benefit from the system, including entrepreneurs, authorities, consumers, and citizens. The system is characterized by positively charged but also abstract values, such as “trust,” “societal benefit,” and “fair competition.” When the quality control systems work, Swedac claims that “conditions are created for trust in everyday life, societal benefits with safe citizens, increased competitiveness in business and global free trade under fair competition.”Footnote 73

Consumers’ Complaints to Swedac

Although Swedac claims to be farthest from end consumers in the hierarchy of quality control, it is still possible to complain to the authority when certifiers fail to live up to expectations. The requirement to have a process for submitting complaints is stated in the ISO standard that accreditors worldwide are expected to follow. There is no articulated restriction as to who may file a complaint, whether it is a certification body being directly affected by decisions made by an accreditor, or indirect stakeholders such as companies certified by an accredited certifier, or end consumers having purchased a product from a manufacturer who holds such a certificate of quality.Footnote 74

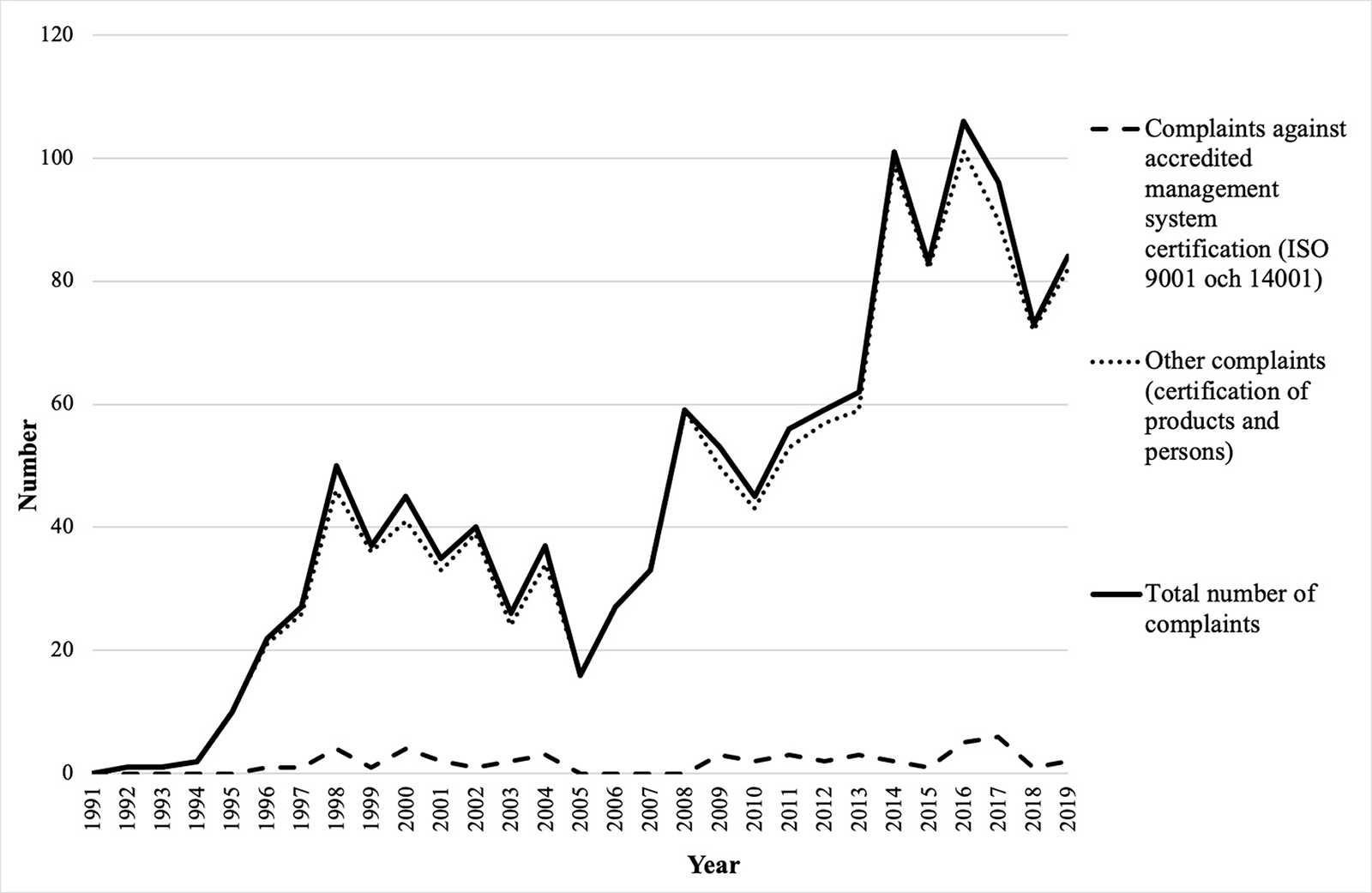

Formal complaints directed to Swedac, in its role as the state authority with the ultimate responsibility for the chain of quality controls that regulate contemporary product markets, is presented in Figure 1, based on an investigation of all complaints to Swedac from 1991 to 2019.

Figure 1. Complaints about accredited management system certifications (ISO 9001 and ISO 14001) and complaints about accredited certifications of products and persons, based on a total investigation of the period 1991–2019.

Source: F1A:154, F1A:184, F1A:227, F1A:275 (1991–1994); legal documents 04 (1995–2012) and legal documents 2.5 (2013–2019), Swedac Archive, Borås.

Our investigation shows that there are relatively few complaints about certifications of products, given the number of certifying companies in the system, but that complaints nonetheless increased over time (see dotted curve in Figure 1). There were considerably fewer complaints about the more abstract management system certifications, a pattern consistent over time despite the “certification revolution” (see the flat dashed curve). Further, of the few complaints that Swedac received, only a small share came from private persons; the majority of those few were from certification firms complaining about unfair competition.

One illustrative example of the abstract character of the system is one of the few individual complaints that was submitted in 2000, here regarding the handling of a ventilation inspection of the apartment building where the person lived. The property management firm responsible for handling the inspection had a valid ISO 9001 certificate issued by an accredited certifier, but, as noted by the complainant, the inspection was approved despite the inspector not performing tests in all of the apartments, as required by the rules of inspection: “It is a mystery how the quality system of the property management firm can meet the requirements set in the SS-EN ISO 9001 standard! Are the requirements so low? If so, it decreases the confidence of both ISO 9001 and Swedac.” Swedac decided to take no further action, explaining to the citizen:

Swedac itself has no direct responsibility at all for any mistakes, as it is not in any direct relationship with the property management firm. Swedac has only accredited the certification firm that has certified the property management firm’s quality management system in accordance with ISO 9001. Any complaints about the certification body’s assessment of the property management firm’s quality system should be submitted to that certification body.Footnote 75

This example illustrates the complexity of a system with a high division of labor and responsibility, with each level only responsible for one part of the chain of quality control. Thus, although Swedac presents itself as a watchdog concerned about individual consumers, with concrete issues such as ensuring that a roller coaster stays on its rails and that the eco-labeled food meets set criteria, it is part of a highly complex and abstract system in which it is difficult to address complaints. Should customers, consumers, or citizens find an organization to address their complaints, they risk being passed to somewhere else.Footnote 76

Substudy 3: The Certification Market

In this section, we examine the management system certification market as it evolved from the end of the 1980s through to today. More specifically, we investigate providers of certifications based on two of the best-selling standards followed by millions of organizations worldwide: the ISO 9001 standard for quality management, and the ISO 14001 standard for environmental management. In certifying firms’ promotional material, ISO 9001 is often labeled the “standard of standards,” and over time described as essential for entering international markets: “Certification according to ISO 9001 is standard and a prerequisite for even being considered as a potential contractor,” stated one firm.Footnote 77 This pinpoints the central historical shift under scrutiny in this section. TSR certification influenced everyday practices of certified firms and connected them to the multilevel bureaucratic market regulations studied in Substudies 1 and 2.

The Certification Revolution

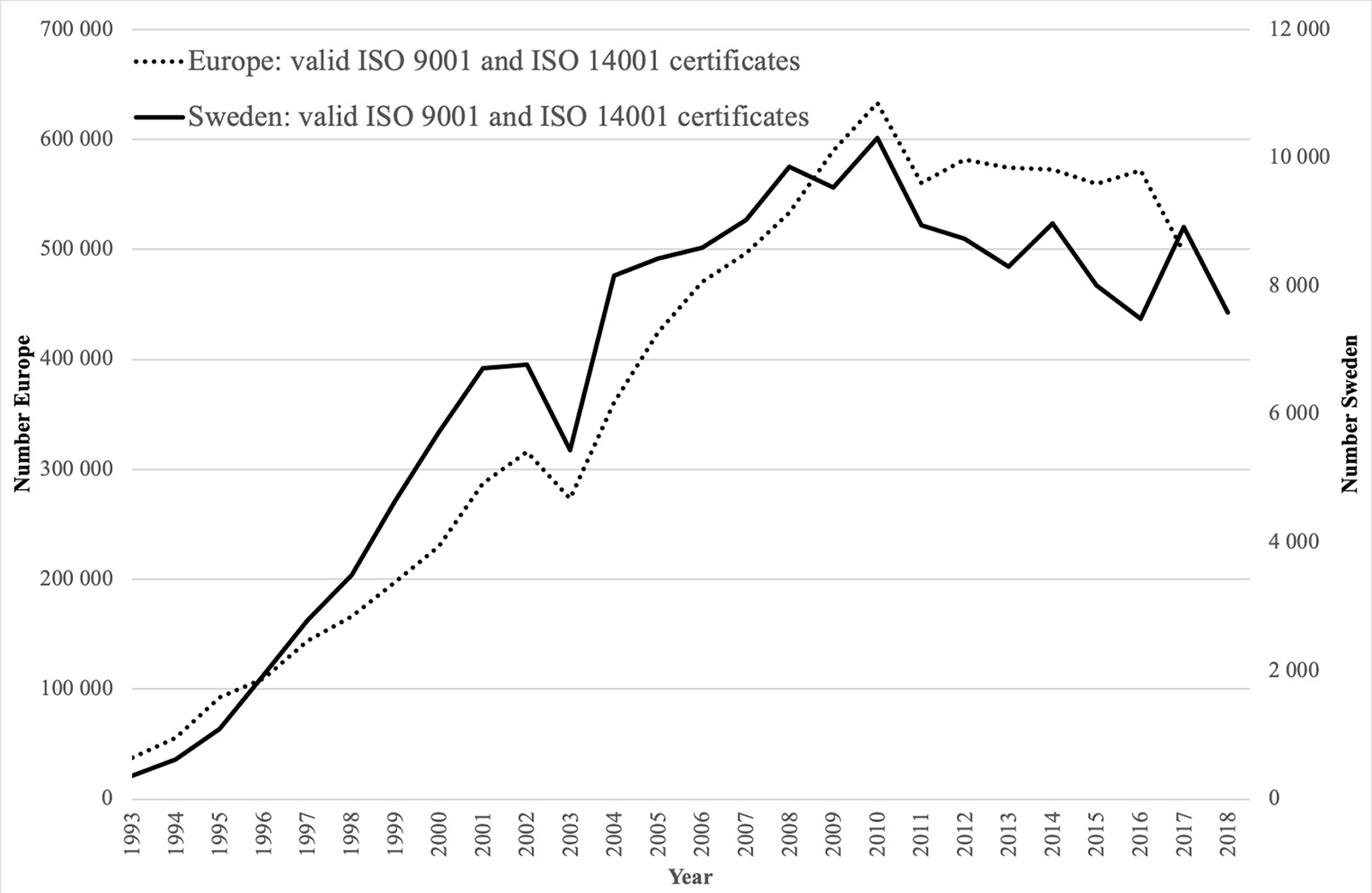

Although certification companies existed before the launch of the ISO 9001 standard in 1987, they initially focused on product certification. This was a small market with only a few certification providers.Footnote 78 Figure 2 shows how certification for quality management (ISO 9001) and environmental management (ISO 14001) expanded rapidly in Sweden (black curve) and Europe (dotted curve) starting in the 1990s and continuing onward. The Swedish development followed that of other countries in Europe, although the number of validated certificates decreased more rapidly in Sweden after the financial crisis of 2008. It is beyond the scope of our study to explain this decrease.Footnote 79

Figure 2. Valid ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 certificates, end of years, in Europe 1993–2017 (left-hand axis) and in Sweden 1993–2018 (right-hand axis).

Source: ISO, “ISO Survey,” https://www.iso.org/the-iso-survey.html (2020-02-04)

It is, however, interesting to note that around the year 2010, Swedac introduced its new goal of increasing the public’s awareness about its work with accredited certification. This led to intensified activities during the years that followed, both at the national level (as we described above) and the global level, through various awareness campaigns, such as that initiated by the International Accreditation Forum.Footnote 80 One example is World Accreditation Day on June 9, launched in 2008, to celebrate accreditation through annually selected themes.Footnote 81 Such activities could be interpreted as attempts, or even struggles, to broaden the base of support for the very foundation of TSR in times of declining interest.

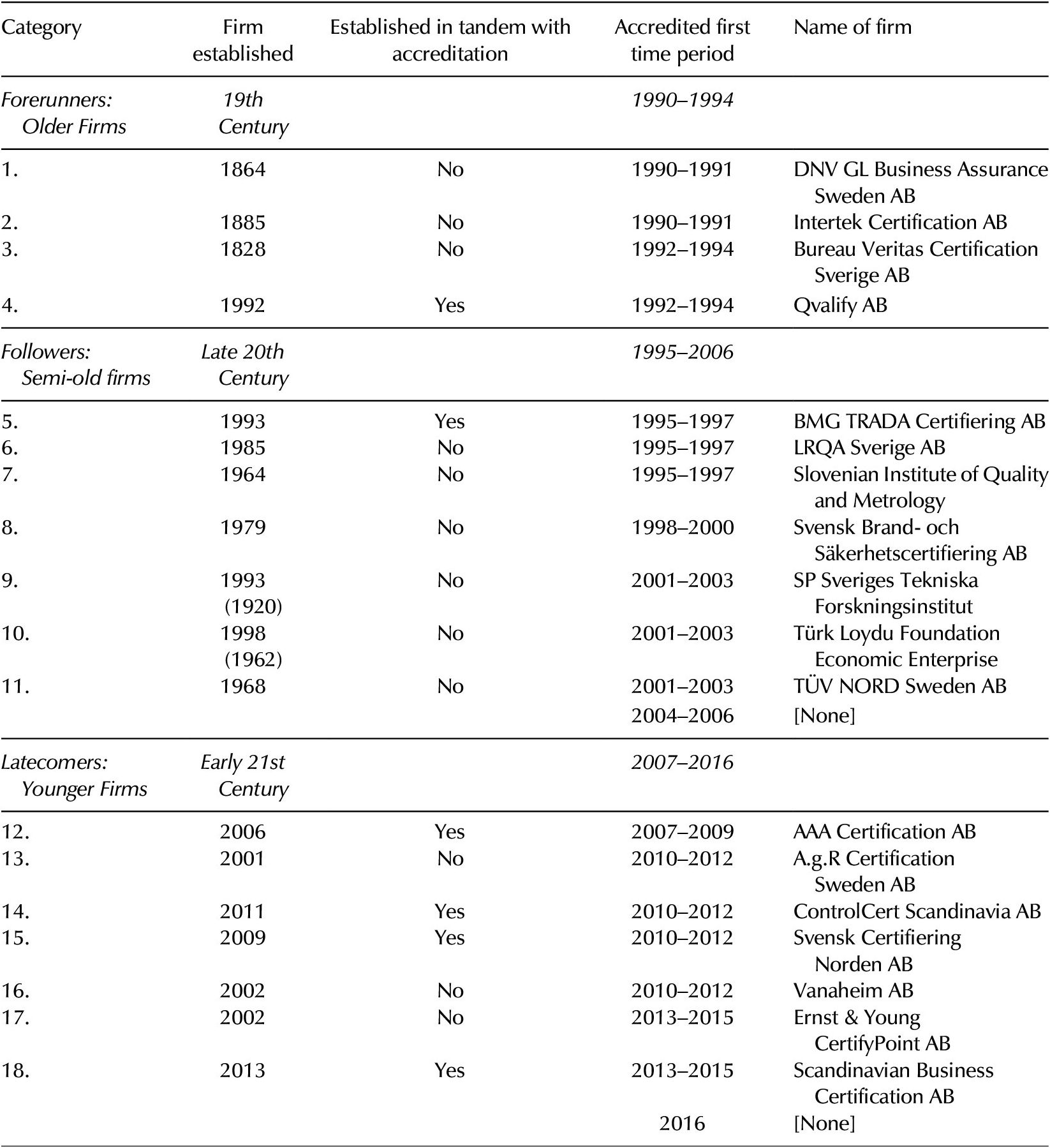

To identify the certification firms behind the numbers in Figure 2, we used Swedac’s register of all eighteen accredited certifiers for management systems that were registered between 1990 and 2016 (Table 1).

Table 1. Accredited management system certification bodies 1990–2016, categorized

Source: Categorization of data from Swedac’s accreditation register (provided by registrar Susanne Skogman, January 26, 2017).

Note: In addition to the eighteen organizations in Table 1, the certification business of the Swedish standard-setter SIS is also included in our study.

Management System Certification: A Key to Europe

In the early promotional material, certification firms defended the new management system certifications in relation to the old regime. Former oversight traditionally controlled only the actual product, which did not automatically render higher quality—only that problems were discovered and defective products were discarded, they argued. The safest way to achieve higher quality was instead to “do it right from the start.” ISO 9000 was described as having been adopted in nearly all EU/European Free Trade Association member-states and increasingly in Sweden.Footnote 82 In the late 1990s, SIS claimed that ISO 9000 was beneficial for all kind of organizations: “[F]or example manufacturing firms, service and auxiliary firms, municipalities, country councils, state authorities, exporting as well as importing firms, sole proprietor firms as well as subsidiaries etc.”Footnote 83

From the start, the push for certification as a tool for competitiveness in the context of increasing global trade was strong. In the early 1990s, when SIS ran its own certification business, they rhetorically asked on one of its many information folders, “How does your firm tackle the great challenge of the 1990s?”Footnote 84 In this type of material, some of which was given away free of charge, others for sale, ISO 9000 was continually described as the “key to Europe.”

In our study of the annual reports of certifying firms, the overall picture—irrespective of whether the firms were forerunners, followers, or latecomers, and irrespective of their size (see Table 1)—is that management system certification was framed as a tool for companies to increase their competitiveness. The 1995 annual report of SIS Certifiering AB stated:

The business has a customer orientation and is oriented towards different industries in order to meet the requirements and demands from the customers. [ . . .] A certification conducted by SIS Certifiering AB should not only lead to a certificate but also provide the customer with a feeling of development of his business, competitiveness and profitability, and thereby lead to added value.Footnote 85

According to this annual report, the main purpose of an ISO 9001 certificate was hence to create added value for the client companies. DNV, which acquired SIS Certifiering AB a few years later, articulated its purpose similarly, and mentioned a broader range of indirect beneficiaries, such as “customers,” “society at large,” and “others.”

Our purpose is to help Swedish businesses and the public sector to assure that the interests of customers, the society at large and others are considered in regards to quality, environment and safety. We are to help the business society and the public sector to strengthen their capability to take responsibility for aspects that influence the quality of a product or a service, external and internal environment, health and aspects with an impact on safety.Footnote 86

The focus was thus described as helping client organizations—Swedish businesses and public sector organizations—strengthen their capabilities to become responsible, customer-oriented actors; this, in turn was assumed to benefit a number of interested parties. For the certifier, however, such beneficiaries were kept at a distance—they were only indirect—while the direct beneficiaries were manufacturers and providers of products and services seeking to become competitive, profitable, and responsible through certification.

The argument that certificates were required in order to survive in the market was even more pronounced in the promotional material. For example, a 2001 marketing folder had the headline “Become a winner!” and described how quality certificates had become a “survival requirement” for guaranteeing “continuous improvements.”Footnote 87 These improvements were made in the interest of the clients. In a brochure from 2004, another certifier claimed that ISO 9001 “stresses the customer’s position and creates an environment for the maximum satisfaction of the customer, something that will render apparent improvement to the financial results in the firm.”Footnote 88 Here, customer satisfaction through higher quality was linked to better financial results. This was also the case when the definition of “customer” widened to society as a whole: “Regardless, if we are working with a management system for quality, working environment, safety or the environment, we all contribute, in one way or the other, to sustainability in society and to future progress for our organizations.”Footnote 89 These statements show how the need for certifications was, at least occasionally, framed as public interest combined with business success.Footnote 90

Several of the certifying companies also had a division or subsidiary selling consultancy and educational services to client companies. In such cases, it was important to show that these business activities were separate from the act of certification to prove that they were upholding their impartiality as third-party auditors. Although independence was highlighted as being a crucial value for certifiers to consider and respect in such cases, end consumers were not mentioned as beneficiaries in relation to the independent role of certifiers. Consumers were virtually absent in descriptions of certifiers’ purpose; rather, the client companies of the certifiers, and indirectly the more generic category of customers, that is, the client companies’ clients, were the main beneficiaries highlighted. This conclusion is valid over time for both large and small companies. The 2015 annual report of one certifying firm gives a good illustration of how the client organizations were described as the main beneficiaries: “In order to be able to continue as the leading provider of services within consultancy, testing and certification, our company will further develop new services in order to help our customers towards a global market society.”Footnote 91

Several of the larger certification firms produced their own trade magazines that they sent to their customers, with news about standards and various positive customer experiences. This further strengthened the notion of a nonconflict between financial gain and customer interest, and even that customer satisfaction per se would render profits for the certified firm.

The Certification Auditor as Business Partner

Since the beginning of the 1990s, the relationship between auditor and auditee was addressed in the promotional material. On several occasions, preconceptions of audits were met with assurances of a more businesslike relation between the two parties. An information leaflet in 1992, for an early version of a certification standard (ISO 10011), for example, suggested that audits were a tool for enhancing the management system. Even if the management group was in charge, every coworker could be seen as a quality auditor for their company. When everyone took responsibility for the quality of their own work, they were practicing continuous improvement of the quality system, the leaflet suggested. A consultant argued that the auditor’s assignment was to “untie knots.” This would become good PR for auditing services: “An audit in positive spirit!”Footnote 92 Auditors had ethical codes of behavior to follow. For example, it was described as unethical to “save” detected noncompliances for the final report without discussing these first at the workplace or presenting them in a meeting. A Swedac official claimed auditors needed to be tough and not back away from delivering unpleasant truths, both orally and in reports.Footnote 93

In 2001, one firm described its auditors as “extroverted, responsive and knowledgeable of the local environment.” The audits were conducted “totally independently without self-interest but with great engagement and with the ability to give support to the clients.”Footnote 94 Here, too, independence was not formulated in terms of distance to the audited firm, but rather in relation to self-interest. Statements from satisfied clients of the certification firms were given as testimonials, as here from 2001: “We are also spurred on when the external auditors from Semko Dekra come. They not only find the noncompliances, [but] we can have conversations with them about how to move forward. They have ‘cheered’ us on.”Footnote 95 Neither “cheering on” their clients nor acting like partners were considered obstacles for impartiality or hurt the credibility of the certification firms. The audit was even sometimes described as a service, as in 2006: “SP’s extensive coverage and in-depth experience in many areas means that we can, in our capacity as a certification body for quality management systems, provide our customers with valuable quality audits and discussions to assist further development.”Footnote 96

A common misunderstanding, according to several statements over time, was that auditors were wrongly compared to controlling policemen who wrote deviation reports that could lead to possible withdrawal of a certification until requirements were met. However, one auditor stated in 1992 that nothing could be further from the truth. The auditor was expected to be interested in and curious about the management system and how it was employed by the firm: “That he asks questions when he is not familiar with the circumstances must be forgiven.”Footnote 97 This type of description was also present in 2015 in a promotional magazine: “The image of an auditor is often a gentleman with a checklist at the ready who audits an organization with a magnifying glass, while representatives from the audited firm are nervously watching. In reality, the auditor is someone quite different.”Footnote 98 The audit had no similarities with a catechetical meeting, according to the article.

One interviewed auditor said that his job was not to chase deviations but to help firms to find areas of possible improvement. After three days of auditing a firm, he presented his findings, positive and negative, at a meeting with the management group:

Not all the possible areas for improvement show up as noncompliances in the report, but are presented as areas for improvement. [. . .] In order for a noncompliance to show up in the report, there needs to be clear requirements in the standard or in the internal management system that are not met. As an auditor, I also believe that it is important to assess if the firm has any benefits from the deficiency, meaning if they can learn something from it and if a correction will result in a real improvement of quality and environmental performance.Footnote 99

To compete on the certification market, certification firms actively downplayed their watchdog roles to appear as “cheerful” business partners, or even coaches. The relationship between certification auditors and their customers, moreover, often included more than simply the auditing. One certification firm stated in a brochure from 1999 that they helped their clients to understand and interpret the standards by means of informational meetings, discussions, and pre-auditing before the actual certification. And afterward, the firm offered continued help to meet client demands and expectations.Footnote 100 In 2001, another firm described the relationship between their auditors and their clients similarly: “We want you to see us as a partner who helps your firm to move forward not just with audits, but also with tailored training and seminars. A certification means that the whole staff knows [. . .] the goals for the future that all have agreed to strive for.”Footnote 101 As the quote illustrates, training was also part of what certifiers offered to their clients and their staff. After analyzing the ephemera, it is clear that much of the printed materials produced by certification firms included educational catalogues and pamphlets. This means that, along with the certification and auditing assignments, certification firms educated potential and current clients in the different standards and related issues. All the certification firms with archived materials, had training departments that offered courses on how to behave in accordance with the standards. Courses covered specific standards, risk management, legislation, and EU directives. They were in all probability a means to bring in extra income as well as a way to recruit new clients.

The certification revolution and the TSR regime were carefully prepared, as we have seen in the previous sections. Actors such as SIS and the certification firms tapped into a well-established narrative of quality systems certification as a tool for strengthening competitiveness on the international market. The adoption of ISO 9001 was framed as the key to the European market, and thus inevitable for Swedish industry. The market for certification expanded quickly in the 1990s and early 2000s, and several certifying firms developed into full-service companies offering assorted services, including training departments that led seminar series on how to behave according to various standards. Professionalization occurred in this process, but in contrast to similar professions, the requirements for becoming a certification auditor were never formalized.

The end consumers were seldom described in the material studied, as noted earlier, although customers, in the meaning clients, were framed in direct or general terms as central to achieving a more profitable business. On the one hand, this nonconflict between customer satisfaction and profitability might be seen as putting the consumer at the very heart of the system. If customers, and by extension the end consumers, were satisfied, the central goal of the quality system was fulfilled. If firms saw customer satisfaction as a ticket to profitability, and during auditing were working in that direction, there would be no need to protect end consumers from the profit-seeking of capitalist production. On the other hand, certification firms’ framing themselves as cheerful business partners rather than as watchdogs safeguarding consumer interest points to the opposite direction. Certification firms sold their services with the argument of nonformalistic audits and the end goal of increasing profits for the clients. Satisfied customers were only framed as a stepping-stone to get there.

Concluding Discussion

The neoliberalization of market control—from the ending of the national testing sites to the establishment of the tripartite standards regimes—was to a large extent a protracted, silent revolution. Although the TSR was not communicated as an alternative to the existing national regime of control, it was nonetheless gradually becoming a replacement as the former regime was losing legitimacy. As with other neoliberalizing reforms in Sweden, the TSR was not framed in opposition to the former system but as a necessity to strengthen or pragmatically adjust to the current state of affairs. Lars Ettarp, the former CEO of Swedac, explained in an interview with Ingrid Gustafsson that the dismantling of the former regime took place without any real political debate: “I consider it the largest de-monopolizing of the 1990s, but we never talked about it.”Footnote 102 This means that although the focus of the Conservative coalition government’s policy included clearly stated neoliberalizing missions, TSR was not implemented with strong ideological motives.

Certification firms became key players in the practical implementation of the new market regulatory regime. However, they framed their clients as mere business partners. They also clearly tapped into the rhetoric of increased competition as a way to achieve higher societal goals, not only in relation to the prosperity of Swedish industry on the global market but also in relation to efficiency and safety. This was further legitimized by government representatives. In this way, certification firms were seen as central actors on the road to national progress.

Today, Swedac frames consumers as their ultimate beneficiaries, and the role of acting watchdogs for consumers legitimizes the regulatory regime. However, this narrative is quite recent. In its beginning, when the two regimes ran in tandem, Swedac instead stressed world trade and competition. This change in rhetoric can be seen as an acknowledgment that consumer protection is still necessary, even in neoliberal market regulatory settings. Even so, our study of Swedac’s practice shows that few consumers seem to know how to navigate in this complex structure of certification and accreditation.

The abstract character and the strict division of labor in the TSR mean that there are multiple levels and actors, each responsible for their own small piece of the much larger system of quality control. As our study shows, in line with the arguments put forward by Béatrice Hibou, the de-regulation also resulted in a re-regulation that included heavy bureaucracy.Footnote 103 Somewhat paradoxically, in the hierarchy of the current regime, certification firms—the actors closer to the consumers—rarely, if ever, mention them, while Swedac, the more distant authority, justifies its existence by protecting end consumers. However, when consumers have complained about businesses, Swedac is often unable or unwilling to help because of these same strict divisions of labor and responsibility. This means that the consumer remains an abstract rhetorical beneficiary within the TSR. Instead of being positioned in an opposing stance to business interests, consumers were rhetorically recalibrated into the larger group of clients or customers whose satisfaction was seen as the basis for the profitability of firms. In this way, any opposition between consumer interests and business interests have largely (at least rhetorically) evaporated. This spills over to the question of public interest as an abstract category with unclear significance. The producers, once certified, were no longer viewed as potential cheats in quality and safety—they were directly controlled only by the certification firms viewing them as business partners and not by the state authority, Swedac, that claimed to be the ultimate responsibility for guaranteeing the safety of consumers and the quality of products.

The abstract nature of the TSR includes a notion that steering and auditing can be done at a distance, with a focus only on the discursive construction of the quality management system. There is an underlying logic that when the right formal system is in place, the quality of products will follow. This, in turn, implies that corporations are not time-serving opportunists. Also, this logic suggests that the risk of a damaged reputation from cheating, which causes consumer boycotts or media scandals, will push them to work according to their formalized quality system. The conflict between corporations and consumers that the former regime built on dissolved in a system in which everyone is considered a winner.

In contrast to previous research, our study suggests that even if the consumer was born during the second wave of standardization, the third wave (1980–2015) instead saw a revival of trade and commercial interests at the expense of the end consumer. The Swedish case shows weakening consumer influence in the TSR.Footnote 104 The golden age of consumer interest had already passed. The consumer remained as a figure of thought—in the work of constructing standards, consumer organizations were experiencing an upsurge—but the state organizations that used to ensure that standards were followed were dismantled, and the certification businesses that replaced them did not see end consumers as their main or direct beneficiaries. This was in line with the market liberal ideology that acknowledged no conflict between consumer and corporate interests. If conditions for business improved and global markets became more synchronized, this would, in theory, benefit the sovereign consumer who—in the end—constituted the demand-side of the economy and, as such, was seen as the real employer of corporations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Handelsbankens forskningsstiftelser projects P17–0140 and P20–0142 for financial assistance to conduct this research.