Britain's urban centers were radically transformed across the second half of the twentieth century. Physically, their largely nineteenth-century urban fabric was overhauled and remodeled, cut through by striking new building forms and infrastructures. Economically, the postwar explosion of personal consumption combined with a waning of traditional industries to transform the core functions of cites, which emerged decisively recast as centers for the new business of shopping, leisure, and pleasure. The coming of mass affluence also wrought far-reaching cultural transformations, and cities competed to reinvent themselves as modish destinations for an increasingly shopping-centered and image-conscious society. The booming postwar property sector was at the heart of all these transformations, and yet we know remarkably little about the development industry and its operations. Instead, historical treatments of cities and their reorganization in this period are dominated by the rise (and, by some accounts, also the fall) of public planning. There is good reason for this. The 1940s saw the installation in Britain for the first time of a comprehensive system of public-planning controls. The subsequent three decades were the era of reconstruction planning and New Towns, slum clearance and mass public housing, and—in the town centers—modernist urban renewal, all conducted under the aegis of the postwar welfare state.Footnote 1 Yet this was also an era in which the commercial development sector exploded in size and significance, establishing itself as a powerful force shaping cities and society. Commercial property development cohered in this period into a recognizable industry, often by working within state-sponsored redevelopment programs. Property development emerged as a key sphere of wealth creation, an attractive form of investment, and a dynamic sector of the economy with far-reaching impacts on many other areas of social and economic life.

Despite this remarkable trajectory and significance, the property business remains a shadowy and little understood presence within postwar historiography. Business historian Peter Scott's important 1996 study of the commercial property sector is a notable exception, but Scott takes the records of investing institutions as his principal source base, and his focus is correspondingly upon financial dynamics rather than urban transformation in a wider sense.Footnote 2 The journalist Oliver Marriott's 1967 book, The Property Boom, remains the fullest and most authoritative account of the postwar property sector.Footnote 3 Yet Marriott was hardly a disinterested observer (he was financial editor at The Times before entering the business himself as a director of one of the leading development companies), and the fact that after more than half a century, his book remains the standard work only serves to underline the paucity of research in this area.

As a step toward filling this gap, this article tracks the extraordinary impact one of Britain's most prominent commercial developers, the Arndale Company, whose operations transformed the social and economic geography of urban Britain. Arndale is best remembered for the scores of modern shopping complexes it developed in British towns and cities in the postwar decades, many still bearing the company name today. The company was one of the first to introduce the enclosed shopping center—the shopping mall—to the United Kingdom, and it was the most prolific in developing this curious new urban typology. In the 1970s in particular, an Arndale center represented the height of modern retailing, and the name came to serve in British popular parlance as a synonym for the shopping mall. Arndale's new consumer facilities offered much more than shopping; they introduced an unfamiliar British public to a whole suite of new landscapes and experiences of mass leisure, from the total sensory submersion of the mall to glitzy nightclubs, American-style diners, and ten-pin bowling alleys. Much of this borrowed heavily from US cultural forms, and it was Arndale and its small handful of competitor companies that provided the modern commercial landscapes through which “the affluent society” was encountered, accommodated, and made concrete.Footnote 4

The company's developments thus transformed the nature of shopping and leisure in urban Britain, offering new forms of consumer experience in increasingly elaborate facilities for which both shoppers and shop tenants were expected to pay a good deal more than before. The soaring values associated with this sort of redevelopment were also at the heart of commercial property's establishment as an inflation-beating asset class in this period, highly sought after by large institutional investors like pension funds and insurers. These trends permanently transformed the stakes involved in urban rebuilding by entangling local decisions about land use and planning within complex financial systems of investment, debt, and accumulation that operated according to their own internal logics and dynamics. Along with leading the charge of British mall development, Arndale was at the forefront of this financialization of urban property development, forging experimental new relationships with large institutional investors as early as the 1950s.Footnote 5

Arndale played a critical role in reshaping the many towns and cities in which it operated. The company's shopping complexes were part of wider programs of town-center redevelopment that entailed extensive demolition and remodeling of the urban environment. Indeed, Arndale's commercial success in the postwar decades is inseparable from the trajectory of state-sponsored urban renewal that was such a marked feature of the period.Footnote 6 Arndale shopping complexes formed the centerpiece of many towns’ comprehensive urban redevelopment schemes and were integrated with new road schemes and public transport hubs; new municipal facilities such as markets, libraries, and carparks; and a whole range of ancillary developments like office blocks, hotels, and housing. Almost all of the company's major developments were planned in collaboration and partnership with local authorities and depended on the sympathetic deployment of new public planning powers—particularly the use (or threat) of compulsory purchase orders to overcome local opposition and obtain the necessary swathes of central-area land. Arndale's story thus provides important new perspectives on the postwar urban renewal order and the political economy of planning. Although the postwar decades are often remembered as the high moment of reformist, state-led town planning, in the town centers at least, Britain's redevelopment regime was never as state-heavy as is frequently imagined. Instead, it relied, as did much of the rest of the postwar settlement, upon new accommodations between the state and private enterprise. Companies like Arndale were the essential counterparts to public planning authorities in a British system in which state powers were used to facilitate redevelopment while the private sector was expected to finance and carry it out.Footnote 7

Arndale quickly established itself as an early specialist in this field of public-private urban renewal. The company molded its business model around the new priorities and parameters of the postwar planning system and devised new and experimental forms of public-private development partnership decades before this became de rigueur in urban policy from the 1980s.Footnote 8 From its inception in 1950, Arndale deftly positioned itself as an essential partner to local authorities looking to revitalize the physical fabric, image, and economy of their towns by offering waning industrial centers the chance to reinvent themselves as affluent shopping destinations. This was urban regeneration avant la lettre, in which struggling cities were rebranded as modish consumer destinations, fitted out with expensive retail and leisure facilities designed to stimulate the local economy and the tax and employment base. Indeed, I suggest that it was Arndale's postwar experiments in town center renewal that established and finessed the partnership-based, property-led redevelopment techniques that would later come to be labelled urban regeneration and ascribed, much too simplistically, to an ideologically driven, neoliberal policy agenda originating in the 1980s.Footnote 9

I

The Arndale Property Trust was formed in 1950 and floated as a public company on the Leeds Stock Exchange. The firm's listing in Leeds reflected its determinedly provincial origins. Its founders and principal directors were two Yorkshire businessmen, Arnold Hagenbach and Sam Chippindale, the Arndale name an amalgamation of their own. Hagenbach was born in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, and since the 1930s had been expanding his Swiss family's confectionery business into a regional chain of bakeries and cafés. One of his successes was winning a major contract to supply the 1951 Festival of Britain with baked goods. Chippindale was a surveyor, estate agent, and property dealer from Otley, north of Leeds, and was working out of Bradford by the time that Arndale Property Trust was formed.Footnote 10 Both men had dabbled in property dealing and some small-scale retail development before the war when this remained a fairly marginal activity, and Arndale was formed by absorbing a number of small preexisting companies in which the two men, their families, and associates were the principal shareholders. The new company inherited from these subsidiaries sixty-five shop properties “in good retail trading positions in nineteen towns in the North and Midlands.”Footnote 11 Arndale's first office was in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, before the company moved to Bradford in 1964 to occupy Arndale House—a modern, air-conditioned office block with a rooftop garden, which the firm built for itself in the midst of that city's booming renewal program.Footnote 12

Such provinciality was highly unusual in the postwar property sector, which centered almost exclusively upon London and grew for the most part out of the capital's unique property markets and commercial networks.Footnote 13 Where Hagenbach and Chippindale were more representative of new entrants to the property sector was in their middling commercial status—prosperous but by no means captains of industry—and in their professional formation. Estate agency, with its detailed knowledge of property markets, trading, and financing, was a common route into the property development world. Retailing was another, particularly for those involved in managing the multiple stores and retail chains that rose to prominence in the interwar period and whose expansionary programs necessarily brought them into the business of acquiring and redeveloping city center properties.Footnote 14 Indeed, it was precisely this interwar growth in the value of retail businesses and retail property that prompted the formation of a recognizable urban property market in Britain, as the “estates” that estate agents dealt in came increasingly to mean urban commercial premises rather than country land holdings, and shop property emerged as an investment of a “very sound nature.”Footnote 15

The years of conflict might be thought to have halted these developments in property markets and trading, but in fact the picture was more complicated. The onset of the war brought about a “precipitous fall in values,”Footnote 16 yet, as ever, disruption spelt economic opportunity for those who were in a position to take advantage of rapidly shifting conditions. Some agents began buying up properties cheaply, acquiring well-located commercial premises in the hope that the market would turn. This it duly did, once the war's end was in sight, and the last years of the conflict saw dramatic rises in property values in which fortunes were made. One government valuation expert noted in 1946 that shop property values were already 40 percent higher than those of 1939 and set for steady and sustained growth over the next decade.Footnote 17 In the immediate aftermath of the war, then, the story was one of rising values and significant business opportunities despite the familiar picture of this era as one of stasis and austerity. Postwar building controls designed to ration limited building materials and labor largely prevented the physical redevelopment of sites, but there were no restrictions on buying and selling property; rising rental levels meant there were substantial economic gains in simply acquiring good commercial property and collecting the buoyant rents. These opportunities were further enhanced by the fact that—unlike in the present day—public awareness of property values and market trends was often poor, so that there were rich pickings to be had for those dealers and estate agents who understood which way the wind was blowing.Footnote 18

It was in this context that the Arndale Property Trust started out, buying up individual shop properties in good trading positions in northern towns and cities and collecting healthy rents while the overall values continued to appreciate. Chippindale was the key figure in this side of the business, with a reputation as a shrewd purchaser and a tough negotiator. At the time of its flotation in 1950, the company's annual rent roll from its sixty-five inherited properties was £34,000 (around £1.2 million in 2020 values) and rising fast.Footnote 19 Arndale was not alone in this activity—other companies were making money in the same way in the decade after the war—but the firm's provincial, northern focus was unusual and became the basis for a unique business model. As soon as the new Conservative administration removed the major regulatory obstacles to redevelopment in the early 1950s, Arndale began pitching its proposals for rebuilding valuable shopping streets to interested local authorities.Footnote 20 Initially the rebuilding took the form of redeveloping stretches of high streets as canopied shopping parades (see figure 1), and the company's activities were focused on small towns across the English North as well as suburban centers within larger conurbations. Arndale carried out early developments along these lines in the towns of Lancaster and Accrington in Lancashire, at Sunderland in the North East, and in the districts of Armley and Headingley in the City of Leeds.

Figure 1 An early Arndale shopping parade in Accrington in the traditional industrial region of Lancashire, mid-1950s. Projects like this represented a significant reorganization of the physical and commercial landscape. Arndale was pleased to have attracted a number of national retail chains to Accrington's “outstandingly successful centre.” Source: Arndale Property Trust, “Arndale in Partnership with Local Authorities,” 1966, RIBA, 711.552.1(41/42)//ARN.

Although relatively modest in scale, such projects involved significant remodeling of existing high streets and shopping infrastructure. Larger, modern shop units—intended to attract successful multiples such as Woolworths and Marks and Spencer—maximized opportunities for alluring window displays and eye-catching shop fronts and introduced provincial populations to the latest retail architectures and the offerings of the leading stores. Improved access and parking provisions enticed customers to shop doors, while retailers’ service and delivery arrangements were made more efficient and discrete, steered safely away from the beautified high street. In an early indication of the public-private collaboration that would become Arndale's hallmark, some of these developments were carried out as part of wider public planning schemes such as new road building (as happened at Headingley) or else were integrated with municipal facilities such as corporation markets (as at Lancaster). Whether or not they relied on such proactive public-private cooperation, the operation of the newly installed postwar planning system meant that all such projects had to secure approval from the local authority in the form of planning permission.

Already by the 1950s, then, Arndale had established a successful model of urban redevelopment that rested on modernizing high-street shopping facilities in conjunction with local authorities. From humble beginnings in small-town shopping parades, Arndale's development projects rapidly grew more ambitious to encompass more expansive pedestrian precincts and, increasingly, the wholesale remodeling of central districts. Yet its efforts remained focused on smaller northern towns in traditional manufacturing regions, whose entrance into the age of affluence continued to feel somewhat tentative and insecure. It is significant, for example, that one of Arndale's first major town center schemes, begun in the mid-1950s and completed by the early 1960s, was at Jarrow—a town still suffering in the postwar decades with its legacy at the center of interwar economic depression. Arndale overhauled what it called Jarrow's semi-derelict town center, installing a new Arndale shopping center, made up of broad, canopied pedestrian precincts housing scores of new shops, a number of national multiple stores, three supermarkets, cafés and restaurants, a twenty-lane bowling alley, and a large carpark. The new pedestrianized shopping landscape was carefully sculpted with fountains, plantings, benches, and other decorative features (figures 2 and 3). Arndale cast all of this in terms of the revitalization and rebirth of the town. Prior to redevelopment, the company claimed, “The extent of decay was unbelievable. It presented such a depressed scene—sufficient to kill any enthusiasm for development . . . The history of Jarrow as a poverty-stricken area was . . . a tremendous challenge.” Now though, there was “hope and new life” in the town, the company claimed; “trees, flower beds and two fountains in the precincts create a new environment for the people” and “the townspeople and many others from the neighbouring communities now enjoy an up-to-date and exciting pedestrian precinct.”Footnote 21

Figure 2 View of the principal access point to Arndale's pedestrianized precinct development at Jarrow. Source: Arndale Property Trust, “Arndale in Partnership with Local Authorities,” 1966, RIBA, 711.552.1(41/42)//ARN.

Figure 3 View along one Jarrow's precincts, showing use of canopies, planting, and benches to “create a new environment” for shoppers. Source: Arndale Property Trust, “Arndale in Partnership with Local Authorities,” 1966, RIBA, 711.552.1(41/42)//ARN.

As a new urban form, Jarrow's “up-to-date and exciting pedestrian precinct” enjoyed a distinguished transnational lineage and the enthusiastic endorsement of many town planning professionals.Footnote 22 The centrally located, fully pedestrianized shopping precinct was beloved of European reconstruction planners. Rotterdam—the reconstruction city par excellence—provided the prototype in the shape of the Lijnbaan shopping center, built between 1949 and 1953 in the heart of the redeveloped city center. This low-rise, modular ensemble replaced the traditional city street pattern with wide pedestrian walkways dedicated to the comfort and delight of the strolling shopper. In the Lijnbaan's precincts, shoppers were sheltered by overhead canopies, seduced by long uninterrupted stretches of alluring shop displays, and entertained by decorative landscaping and other amusements such as aviaries of exotic birds. The professional planner's yearnings for efficiency, safety, and functionality were sated by banishing all vehicular traffic and servicing to a back-street network of carparks and delivery bays.Footnote 23 The Lijnbaan was repeatedly feted by leading figures in British planning, and in the mid-1950s pedestrianized shopping precincts were being installed in the rebuilt centers of blitzed cities like Coventry and Canterbury and as the centerpieces of the first wave of New Towns. (Stevenage, for example, was proudly projected by one British planning consultant to be “the largest all-pedestrian shopping centre in Europe.”Footnote 24) Arndale was not the favored commercial partner for these New Town and blitz reconstruction projects. The market here was cornered by another extremely effective postwar developer, Ravenseft Properties Ltd., whose unparalleled success amid this bonanza of public building contracts molded it into a major commercial force and Arndale's chief competitor.Footnote 25

Although public planners and private developers in Britain may have looked across the North Sea for design ideas, the real inspiration—culturally, commercially, and architecturally—came from across the Atlantic. It was the visions of affluence, mass consumption, and commercial modernity that were being generated in the “consumers’ republic” of the United States that provided the bedrock of ideas and forms on which developments like that at Jarrow were built.Footnote 26 In the 1930s and 1940s, as Europe was tearing itself apart, commercial architects and developers in the United States were devising new urban forms to service the demands of a mass-consuming, motorized, and increasingly suburbanized society. In the wide-open spaces that lay beyond the city limits, new (and exclusive) urban geographies were taking shape—sprawling, spacious, and suburban. It was here that the now instantly recognizable form of the shopping center—clusters of sleek modern shops planned as a carefully choreographed unity—emerged from the experimental efforts of architects and realtors to create new nodes of commercial attraction.Footnote 27 The low-rise, leisured, and languid landscape of the postwar pedestrian precinct came directly from these American experiments in suburban commercial modernism. Rotterdam's planners self-consciously adapted American building types to their purposes, while in Britain leading urbanists also looked intently at American developments and engaged with the design debates and literatures that accompanied them.Footnote 28 The chief architect and planner of Cumbernauld, a designated New Town, was clear that “planners in this country have much to learn from American practice” in the design of shopping centers.Footnote 29 Indeed, the new commercial complexes that began appearing in British towns and cities in the 1950s were commonly referred to as “American-style” shopping centers.Footnote 30

These transatlantic transfers went well beyond architecture. With its unprecedented prosperity and burgeoning consumer cultures, the United States was widely viewed as the model of an affluent, commercially and culturally modern society.Footnote 31 Thus, what Arndale was installing in 1950s’ Jarrow was far more than a new urban streetscape: the offerings were as much cultural as commercial. The Daily Mail interpreted “Jarrow's fine shopping centre” as a sign of the town's entry into “the new age” and “the affluent society.”Footnote 32 The twenty-lane bowling alley that Arndale planted in the middle of Jarrow was a direct American import, and something the company replicated in almost all if its early developments. (Arndale owned 20 percent of Excel Bowling Ltd., a company that imported the equipment from America and operated these facilities.Footnote 33) Arndale's new town center also brought self-service supermarkets to Jarrow, with their efficiency-maximizing innovations in store design and retail methods. These were another postwar import from the United States, and their spread in the United Kingdom was encouraged by the Marshall Plan–funded activities of the Anglo-American Council on Productivity.Footnote 34 The largest store in the complex at Jarrow was a branch of the F. W. Woolworths chain, originally another American company and a long-standing pioneer of new retail methods. Other facilities provided as part of the redevelopment made clear the extent of cultural reinvention that was envisioned. A 1962 news item in The Stage gave further details of “Jarrow's New Image” under the subheading “Former Hunger March Town Blossoms into Luxury Living.” Here the focus was on “the Club Franchi,” described as “the most luxurious nightclub in the North of England . . . occupying the two top floors of the magnificent new Arndale House in Jarrow's recently developed Viking Precinct.” This glamorous commercial leisure complex had been fitted out “in true Venetian style, complete with gondolas and mooring posts” by a London-based interior designer at a cost of over £50,000. The Club Franchi also included a seventy-seat restaurant and a casino.Footnote 35 Jarrow's remarkable reincarnation even made it into the international press: a New York Times correspondent informed American readers that the town's new shopping centre “could fit easily in a Long Island suburb.”Footnote 36

Arndale's remodeling of Jarrow was thus bound up with broad, transnational currents of social change and heavily freighted with the new commercial cultures of American-style affluence. Yet it was also a project that relied completely on the proactive support of the public sector, in the shape of the local planning authority. The necessary land for Arndale's affluent makeover was provided by Jarrow and Hebburn District Council and was in fact, the company reported, “largely slum-cleared land,” meaning it had been acquired compulsorily and cheaply by the local authority for the purposes of housing improvement before being leased to Arndale for commercial redevelopment. “What Arndale has done in Jarrow would not have been possible without the full co-operation and enthusiasm of the Local Authority.”Footnote 37 Councilors and officials were enthused by the idea of a social and economic renaissance in their town, and they narrated the endeavor in terms strikingly similar to that of their private sector partner. Representing the local authority at the 1956 public inquiry into the redevelopment scheme, one civic official lambasted the existing town center as “a miserable picture”; it was “drab and depressing,” “extremely unattractive,” and “poor by any standard.” The new plans for the shopping center offered “a glorious chance to revitalise the town.” Space would be made for this exciting reincarnation through the blanket application of slum clearance powers and the decanting of thousands of residents off to new overspill estates on the town peripheries. The council had scheduled three thousand of the four thousand houses in the older part of the town center for demolition.Footnote 38

Also facing dispossession and displacement was much of Jarrow's existing business community. In a pattern repeated up and down the country in the era of reconstruction and renewal, whole swathes of small-scale, independent businesses were wiped out by these town center redevelopment schemes, which were expressly intended to raise property values and attract new, higher-value retail businesses. As a result, opposition to the development at the 1956 inquiry was led by the shopkeepers’ trade association, the Jarrow and Hebburn Chamber of Trade, whose members had spent years making public pleas and private petitions for consideration to the council but were repeatedly rebuffed.Footnote 39 The local authority expected to lose 122 existing shops and 33 public houses as part of the redevelopment, with its representative telling the public inquiry that “most of the small shops would have to go,” and that “inevitably not all the small traders would be able to afford the rents of modern shopping premises.”Footnote 40 For these small-business interests, redevelopment often meant the demise of long-established, intensely local family businesses, and until the end of the 1950s, statutory provisions for compensation were weak.Footnote 41

The visceral anger that such projects provoked was directed at what were seen as unholy alliances between councils and commercial developers, with local business owners understandably aggrieved at the way public planning and compulsory purchase powers were used to drive through what were ostensibly commercial, profit-making schemes. In the Lancashire coastal town of Morecambe, where Arndale was pursuing another town-center development in partnership with the local planning authority, a member of the local Chamber of Trade sent an anguished objection to the Ministry of Housing and Local Government: “The general effect of such development is to create that class of tenant having no direct interest in our town . . . traders who have created this shopping centre in Morecambe and given life and vitality to it and served the public over generations would be swept aside by the powerful Arndale Property Trust—seemingly with the connivance of the Local Authority—and thrust out of business just because Development Companies find shops the most profitable prey in redevelopment schemes.”Footnote 42 The price of progress—at least as local authorities saw it—was a permanent reconfiguration of the business landscape, and many small-scale enterprises fell by the wayside.

II

In 1950s Jarrow and other fading industrial towns across West Yorkshire, Lancashire, Scotland, and the North East, the Arndale Property Trust developed a model of urban renewal that was to prove remarkably enduring. It rested upon the retail-led reinvention of waning industrial towns, replacing their down-at-heel central districts with newly built shopping facilities that were designed to bring a sense of prosperity and offer local populations access to modern shopping in the latest retail environments. It was simultaneously a response to national currents of enthusiasm for the promises of consumer abundance held out by the affluent society and a finely tuned local intervention that was sensitive to the unique challenges faced by towns and cities in traditional industrial regions. Although nationally Britain enjoyed a golden age of economic growth and prosperity in the postwar decades, the regional picture was much more variegated and uncertain. After their dramatic nineteenth-century successes, the country's traditional industrial heartlands in the English North, Scotland, and Wales spent the twentieth century in a state of relative decline vis-à-vis London and the South East, as basic industries contracted while new industries and the booming service sector gravitated strongly around London.Footnote 43

There were significant urban dynamics to these regional trends. Urban councils in England's North were left anxious about their faltering industrial bases and watched employment, population, and economic activity drift steadily southward. As early as 1938, the City of Leeds's Development Committee lamented the fact that “the development of Leeds . . . has been retarded by the concentration of industry in the South.”Footnote 44 In Manchester, the city's 1945 reconstruction plan also railed against the “disastrous drift away from the basic industrial regions” and complained that over half of all the new factories established between 1934 and 1938 had been in or around London.Footnote 45 For smaller urban centers in these regions—the sort of places where Arndale focused its early activities—the picture was considerably bleaker. In the Lancashire town of Bolton, for example, once one of the most important centers for cotton spinning in the world, the middle decades of the twentieth century were a “litany of industrial misery” marked by the collapse of traditional industries, consistently high unemployment, and out-migration.Footnote 46 Already in 1958, Bolton's civic leaders declared that “the time had come for the council to attract new industries by ‘selling’ itself to big business interests.”Footnote 47 The town duly received its Arndale center in 1971, planted right in the civic heart of Bolton, directly opposite the nineteenth-century town hall. In a jointly issued prospectus, Bolton Corporation along with Town & City Properties (Arndale's new parent company) welcomed the arrival of “a town centre equipped to meet the estimated requirements of the 21st century [with] pedestrian precincts, car parks and office and shop developments.” The new shopping center would, it was claimed, return “industrial and commercial prosperity” to the town by making Bolton “the established regional centre for employment, shopping, and cultural and social activities [and] attracting people from surrounding districts.”Footnote 48

Arndale's offer of reinvention as a prosperous shopping destination was thus an extremely attractive prospect for many local authorities facing severe structural challenges around economic activity and employment. Such places were also wrestling with the physical inheritance of their nineteenth-century heydays in the form of an aging, at times dilapidated, urban environment. The conservationist sensibilities with which we might view such urban landscapes today only rose to prominence in the 1970s—partly as a reaction to the destruction of the urban renewal era. In the earlier postwar decades, most councils were only too happy to countenance widespread demolition in the service of fundamental developmental priorities.Footnote 49 Nor did councils relinquish their ambitions for industrial rejuvenation; rather, the retail-led reinvention of central areas was presented as part of a broader process of economic renewal that would include new industrial activity and employment.

Arndale was keen to emphasize these dynamics in its overtures to local authorities. Thus, in the depressed mining town of Spennymoor in County Durham, the company suggested that its pedestrian shopping precinct was stimulating new investment in the town: “New factories have been built, and we believe others are likely to come; especially as shopping facilities will be so much improved.”Footnote 50 In a foreshadowing of late-century urban regeneration agendas, Arndale's publicity constantly stressed the capacity of its developments to transform the fortunes of towns, to draw in national retail chains, rejuvenate depressed areas, and reinvigorate local communities and commerce. Such ideas were made explicit at the company's 1963 annual general meeting, where Hagenbach reported on the preponderance of schemes in the north of England “in areas of under-employment where new industries are actively being sought.” “Modern shopping facilities,” he suggested, “make these areas much more attractive to those who are considering the establishment of factories there.”Footnote 51

Arndale's modus operandi reflected its directors’ intuitive understanding of the hard economic challenges faced by many towns in traditional industrial regions even at the height of the postwar boom. Many of the company's early projects in West Yorkshire—such as in Shipley and Wakefield—were very much on the company's home turf, but Sam Chippindale also made a point of traveling widely and developing personal contacts with local councilors and officials across a broad swathe of the English North and Scotland. Edward Erdman, one of the leading commercial estate agents of this era, recalled that Chippindale “impressed many local authorities” with his “strong personality” and “forthright opinions.”Footnote 52 Oliver Marriott, who served as the Times's property correspondent in the 1960s, quotes a Jarrow councilor's comment that Chippindale “impressed some of my councillors who were more than a little difficult to impress. You see, he spoke a language we understood.”Footnote 53 Chippindale's ability to speak the language of provincial civic leaders was central to the success of the firm, with Hagenbach telling his shareholders at the company's 1961 annual general meeting that the company's achievements rested firmly upon “the satisfactory collaboration we have, through our agents [Messrs. S. H. Chippindale & Co.], with so many Local Authorities.”Footnote 54

Chippindale had a good grasp of the mentality and aspirations of local politicians and civic officials, ensuring that councilors’ praises were loudly sung and that opening ceremonies were carried out with as much civic pomp as possible (figure 4). At Jarrow, the company praised the “dedicated men—the elected Councillors and Aldermen and the Officials—who were determined to forge ahead to provide a better town.”Footnote 55 The company was also remarkably astute in sensing the ways in which towns’ local history could be harnessed to the project of successful commercial reinvention. At Jarrow, although redevelopment represented an effort to throw off the town's interwar history of depression and unemployment, other aspects of so-called local heritage were revived and instrumentalized. “The Venerable Bede founded Jarrow and the Vikings made a landing here—all a very long time ago,” Arndale's publicity noted glibly. Thus, “Bede Precinct and the Viking Precinct were logical names for the two main shopping areas.”Footnote 56 Further nods to local history could be found over a cup of tea at the Bede Café, while Arndale also installed a large bronze sculpture of two stylized Vikings standing proudly between Jarrow's nineteenth-century town hall and Chinacraft Crockery.

Figure 4 Arndale director Sam Chippindale (center) posing with Jarrow's mayor and Richard Crossman, minister of housing and local government, at an opening ceremony for the new shopping development. Such events celebrated both the hoped-for rebirth of redeveloped towns and the partnership between council and developer through ritualized performances. They also provided valuable publicity for new centers and an opportunity for local officials to don civic finery. Source: Arndale Property Trust, “Arndale in Partnership with Local Authorities,” 1966, RIBA, 711.552.1(41/42)//ARN.

Chippindale understood the aspirations but also the anxieties of councilors, who could be wary of the rapidly expanding property sector and its somewhat dubious reputation. The prospectuses that the firm produced to market its services to local authorities were designed to reassure hesitant civic officials, offering walk-through explanations of the redevelopment process and affirmations of the firm's sympathy with local aims. Existing developments served as exhibits and testimonials, with the company's new town center at Shipley receiving “over 80 deputations from Local Authorities all over the country [who] visited the town ‘to see for themselves.’”Footnote 57 The firm's head office in Bradford had permanent display space set aside for “the exhibition of plans and models of various projects” to visiting councilors, and Chippindale and his agents stood ready to call on councils anywhere in the country to “give advice . . . and to show films.”Footnote 58 A 1966 promotional film produced to show to councils outlined the many economic, planning, and branding advantages of its “modern shopping centres” and dwelt upon the glamour and ceremonial on offer, as when, for example, the popular TV entertainer Bruce Forsyth conducted the official opening of Shipley's new town center. Other mid-1960s precincts at Walkden, Greater Manchester, and Jarrow were shown being ceremonially opened by the senior Labour ministers George Brown and Richard Crossman respectively.Footnote 59

Through such means councilors and officials were coaxed and reassured, and the energy devoted to these activities reflects the fact that, while they did not pay Arndale directly, local planning authorities had to be courted as though they were customers. Councils’ new planning powers made them gatekeepers in the acquisition and redevelopment of centrally located urban land; they controlled the supply of the essential commodity without which Arndale could not build and prosper from its retail facilities. Local authorities had to be persuaded to invest this valuable resource in the Arndale Property Trust and entrust the future of their town centers to the company. Arndale's town-center renewal schemes required councils to deploy their new planning powers in support of the company's commercial objectives by granting planning permissions and, more importantly, wielding their powers of compulsory purchase to face down local opposition and transform fragmented patchworks of plot ownership into large, profitable sites for redevelopment.Footnote 60 The company's operations in this field were based upon the prescient recognition that the new postwar planning system, far from being an obstacle to development, in fact represented a huge commercial opportunity. The bolstered powers that local councils were granted under the system, in particular around compulsory purchase, presented lucrative opportunities to acquire and redevelop not just individual building plots but entire central districts. Extensive reorganization and rebuilding of central business and shopping districts could now be countenanced, which, in the context of rising property values and a surging consumer economy, promised to be enormously profitable.

III

By 1965, Arndale had completed more than twenty substantial shopping developments in various towns and cities across Yorkshire, Lancashire, the North East, and Scotland. It had twelve further schemes in progress and was negotiating with many more councils. The company had expanded rapidly, and shares in “this most progressive Company” were regularly tipped in the financial columns as a lucrative investment.Footnote 61 Arndale's income almost doubled between 1964 and 1966 as its early developments began to deliver substantial rents and the company paid out healthy dividends of 16 percent to its shareholders.Footnote 62 This bullish performance was based in part on the company's snowballing success in securing development deals with local authorities; in part it reflected more general trends. Property values and rents had risen inexorably since the war, and the burgeoning commercial development industry was rapidly establishing itself as one of the most dynamic sectors of the economy. Such market trends were inseparable from the postwar urban redevelopment regime in full swing in Britain's towns and cities. The early 1960s marked the high point of enthusiasm for comprehensive development and modernist urban renewal. Councils showed themselves willing to deploy their planning and compulsory-purchase powers aggressively in pursuit of expansive redevelopment programs, and a new generation of architects and planners enthusiastically worked up elaborate schemes for remodeling cities.Footnote 63

These conditions fueled a dramatic boom in the property sector: the total value of all the property companies listed on the London Stock Exchange rose meteorically in the four years between 1958 and 1962, from £103 million to £800 million.Footnote 64 Finance for development was readily available, and became even more so in the deregulatory moment of the late 1950s, when the government abandoned postwar controls over new capital issues and eased restrictions on the money markets in general.Footnote 65 Arndale successfully rode this wave of financial enthusiasm for the property sector. The firm secured large-scale investment for its ambitious development program by enlisting the abundant resources of the big financial institutions—the pension funds and insurance companies that became “the primary owners of British capital” in this period.Footnote 66 These financial institutions found themselves in command of vast funds in the decades after the war, driven by a massive growth in occupational pensions, generous tax reliefs, and high returns on investment. Although they had traditionally been wary of the speculative world of property, funds began to invest heavily from the 1950s onward, attracted by rising property values and the dramatic gains to be made by redeveloping valuable central area locations.Footnote 67 Entering the property investment business required forging new alliances with property development companies, and Arndale was at the forefront of this. In December 1954, the company entered into a novel arrangement with the venerable insurer Clerical Medical. The company agreed to provide Arndale with a large loan at a fixed rate of interest in return for an option to purchase a large tranche of Arndale shares at a fixed price in two years’ time.Footnote 68 Essentially this arrangement allowed the lending fund to profit directly from the growth in the value of the property company that its loan would unlock. In his detailed account of the insurance industry's engagement with property, Peter Scott suggests that this deal between Arndale and Clerical Medical “constituted the earliest use of what was to become a very widespread equity participation technique in the early 1960s.”Footnote 69

The 1954 deal with Clerical Medical secured a loan of £450,000. By 1965, Arndale had access to £19.5 million (£386m in 2020 values) in long-term finance through similar arrangements with the Scottish Widows Life Assurance Society, the Commercial Union Assurance Co. Ltd., and Imperial Chemical Industries’ pension fund. The latter's pension fund, like Clerical Medical's, held a significant chunk of Arndale shares in addition to providing generous, low-interest loans. Imperial Chemical Industries also placed one of its fund managers on Arndale's board of directors.Footnote 70 This was another important step in the entanglement of urban redevelopment with corporate finance, as financial institutions began to take an official, active hand in directing the operations of the property companies in which they invested. In a further circular arrangement, another of Arndale's major shareholders was the Local Authorities’ Mutual Investment Trust. This body was set up in 1961 to manage the overflowing pension funds of local authorities, and by the mid-1960s, 350 councils were signed up.Footnote 71 Given that it was local authorities’ planning decisions that largely determined Arndale's profitability, this relationship was a particularly symbiotic one. The deepening ties between the redevelopment and financial sectors were critical to the trajectory of postwar urban renewal in Britain, and yet they have barely registered within most historical accounts of postwar urbanism and planning. It was the yield-maximizing logics of the financial sector, for example, that dictated the excessive focus upon high-end retail development in Britain's town centers; luxury shopping facilities, along with expensive office space, were favored by developers and their financial backers because they promised the highest returns.Footnote 72

Emboldened by this combination of an enabling planning regime and a flood of private investment, Arndale's directors vigorously began to promote what would become their signature development type: the covered shopping center (or mall, in US terminology). Chippindale was again the driving force here and became something of an evangelist for this new mode of retail development—“uncompromising in his criticism of old-fashioned shopping methods” and able to “expound fluently, and almost indefinitely, on covered shopping centres,” as one contemporary recalled.Footnote 73 The mall, an American invention of the 1950s, has since become a globally ubiquitous urban form, but it was through the agency of commercial actors like Chippindale that the shopping center came to Britain in the 1960s.Footnote 74

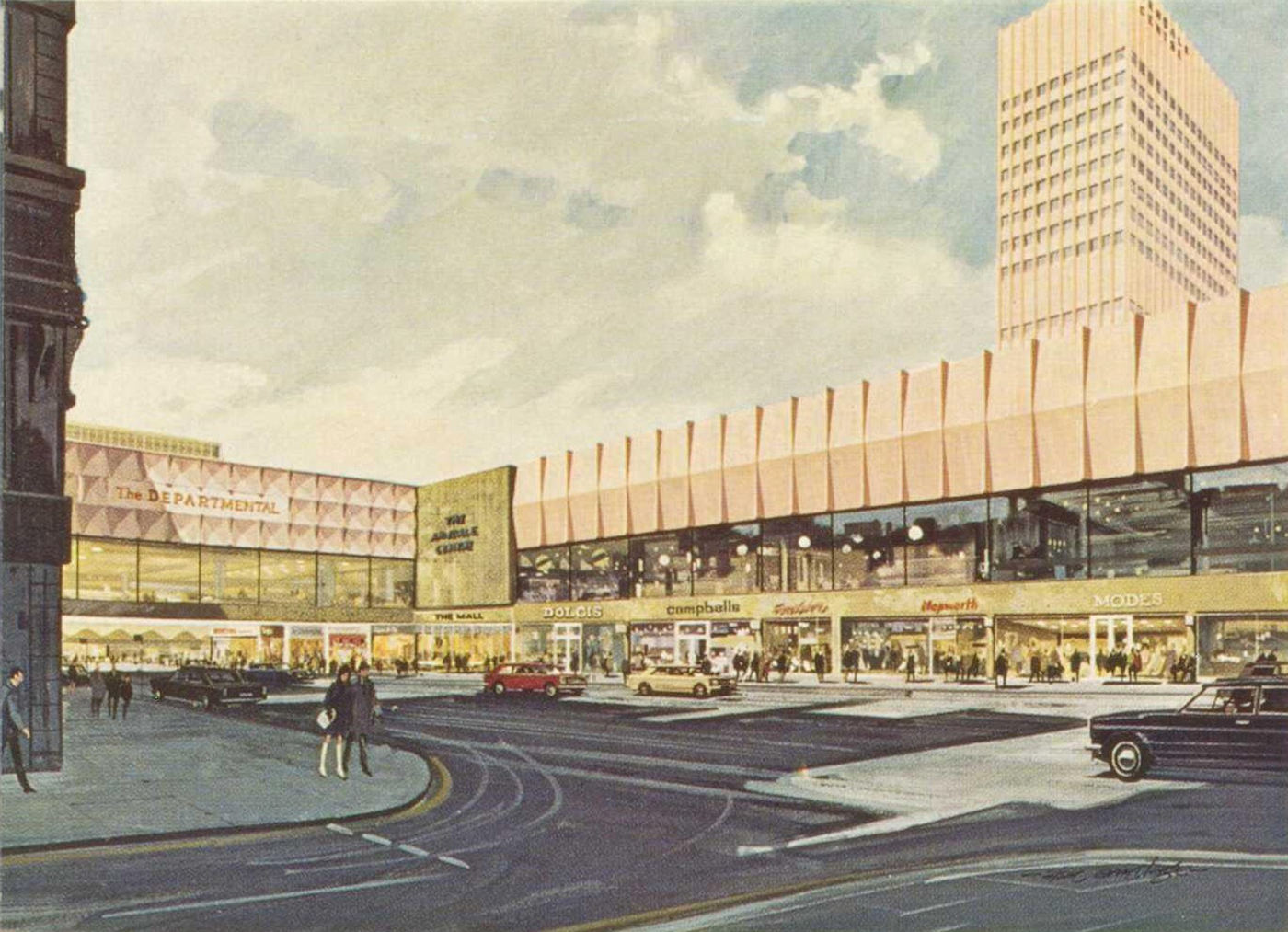

On a return trip from Australia in 1960 (where Arndale was also doing business), Chippindale stopped off in the United States and “met a group of architects who specialised in covering shopping centres.”Footnote 75 He was clearly inspired, and Arndale made a point of hiring consultant architects with experience working on North American malls to add a touch of transatlantic luster to its British projects. This, for example, was how the name of John Graham Jr., of Seattle and New York, came to be attached to the Arndale center in Doncaster, South Yorkshire. Graham was one of the American originators, responsible for designing Seattle's Northgate Centre, one of the earliest American shopping centers, which opened in 1950. His practice also designed Seattle's iconic Space Needle—a spindly, space-age observation tower built for the 1962 World's Fair and topped with a futuristic revolving restaurant. Graham patented the revolving restaurant idea and installed another in the early 1960s as part of the Ala Moana commercial development in Honolulu.Footnote 76 (The Ala Moana shopping center remains one of the largest malls in the United States today.) At the same time that he was engaged on these spectacular commercial projects across the United States, John Graham was also at work on behalf of Arndale, reimagining 1960s Doncaster (figure 5).

Figure 5 Artist's impression of the proposed Arndale center in Doncaster, on which the US architect John Graham, Jr. was engaged. Shops were accessed from street level, with parking facilities overhead. This scheme was tied to a new inner ring road and council bus station and was, Arndale claimed, “perfectly integrated into the overall town centre planning.” Source: Arndale Property Trust, “Arndale in Partnership with Local Authorities,” 1966, RIBA, 711.552.1(41/42)//ARN.

Arndale thus brought modish new shopping experiences and prestigious international architectures to the provincial towns and cities of postwar Britain. Many local authorities were understandably impressed. At a time when the United States seemed to be blazing a trail of affluence and abundance for others to follow, the North American credentials of Arndale's star consultants worked powerfully on city leaders in places like Doncaster. “Doncaster Town Council,” Arndale noted, “contributed in every possible way in helping to bring this scheme to fruition.”Footnote 77 In Stretford, an unspectacular subcenter of the Manchester conurbation, another Arndale center was in gestation in the mid-1960s, and local officials were similarly enthused by the company's American connections. It was Chippindale's agent, a Mr. Ramsay, who pitched the idea of planting an extravagant mall in the center of Stretford, “following a fashion adopted in the United States,” as he explained in a meeting with civic officials.Footnote 78 Before long, Stretford's town clerk was writing to the Ministry of Housing and Local Government to explain, with more than a touch of provincial pride, that another of Arndale's American consultants, a Mr. Gray, “tells me that the scheme is based on one or two he has himself dealt with in Canada and the United States.”Footnote 79 Although local authorities were eager to align their towns with the voguish cultures of affluent consumerism, they often had only limited understanding of the rapidly changing world of shopping and personal consumption, and little practical sense of the prospects and possibilities of retail development. Councils thus relied heavily upon commercial interlocutors like Arndale. The company's publicity placed great emphasis on its understanding of the latest trends in “modern retailing,” its extensive connections with the major retailers, and its “unrivalled knowledge and experience of this type of commercial redevelopment.” It was Arndale, councils were reminded, that had its “finger on the pulse of the market.”Footnote 80

Arndale was not the only company that built enclosed shopping centers in Britain, nor did it build the first—this was Birmingham's Bull Ring Centre, which opened in 1964—but it was the most prolific. Its first enclosed shopping center was built in Australia in the rapidly expanding suburbs of Adelaide, but in 1967, the company opened its first mall in Britain at Crossgates, an affluent suburb of Leeds. (The chief architect here was John Poulson, whose spectacular 1972 corruption trial brought down multiple politicians, including the serving home secretary, Reginald Maudling.Footnote 81) Less than a decade after the Crossgates Arndale opened, the company had fifteen other malls open and trading all over the country. Arndale's original northern, small-town focus was evident in the preponderance of malls in Lancashire towns (Bolton, Middleton, Morecambe, Nelson, and Stretford) and its Yorkshire developments at Doncaster and Bradford. But the firm had also moved successfully into some smaller towns in the south of England, such as Poole in Dorset, Dartford on London's outer fringe, and Wellingborough in Northamptonshire. More significantly, it had begun working on some very large redevelopment schemes in major urban centers: Nottingham, Luton, Manchester, and Wandsworth. These projects varied substantially in size and cost; smaller centers could cost a few million pounds, while the largest, at Manchester, amounted to £100 million by the final reckoning. Whether large or small, though, all required substantial reorganizations of the existing urban fabric and close collaboration with the local authorities concerned. Indeed, this collaboration was now placed explicitly at the heart of the company's strategy, with Hagenbach telling shareholders that “our primary function continues to be to improve by redevelopment the old centres of towns and cities mainly in partnership with Local Authorities.” He went on: “Such schemes are now comprehensive, covering office, commercial, residential and entertainment in addition to normal shopping facilities.”Footnote 82

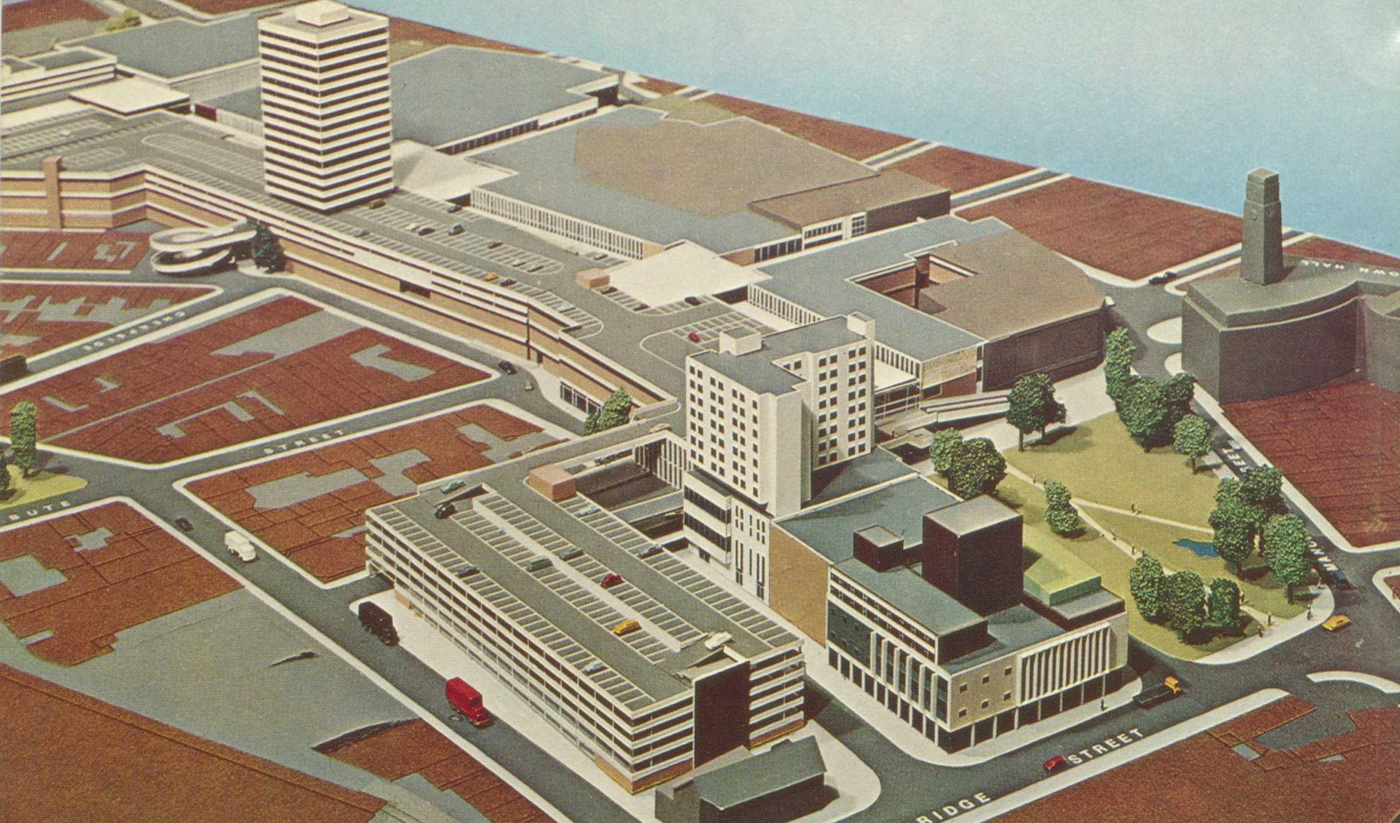

Arndale was now selling local authorities a model of complete town-center renewal, with its shopping center developments linked with new road schemes and multi-story carparks, hotels, and office blocks and wide-ranging ancillary commercial developments such as bowling alleys, dance halls, nightclubs, and restaurants. One of its biggest developments, which overhauled Luton's town center, included a 151-bedroom hotel (figure 6), while at Wandsworth in south London another mammoth scheme incorporated four twenty-story tower blocks containing over five hundred local authority flats.Footnote 83 This comprehensive mix of facilities, and the integration in particular of social housing into some schemes, was a reflection of the hybrid, public-private character of Arndale's work. Both the developer and the local authorities it partnered with were keen to stress the civic character of these projects, which would, it was claimed, generate a range of social benefits for local communities alongside the financial returns for investors. Arndale's malls, the company suggested, provided “a focal point comprising attractive shopping, leisure facilities and public services . . . which forms the commercial heart of the community.” With this in mind, some Arndale complexes incorporated new municipal facilities such as libraries or sports halls, although it should be noted that it was always the local authorities that were required to bear the full cost of any such additions. The company's concerns with the wider life of the local community certainly did not stretch that far.

Figure 6 Architectural model of Luton's new town center development, carried out in partnership with Luton Corporation between 1969 and 1975. The seventeen-acre development encompassed an enclosed Arndale shopping mall with 750,000 square feet of shopping space, 100,000 of office space, multistory parking for 2,500 cars, a large hotel, new Luton Corporation market hall, public house, social club, and petrol station. Such modes of redevelopment completely transformed urban centers. Source: Town & City Properties Ltd., Report and Accounts (1971), P&O/35/940, National Maritime Museum, London.

Despite this somewhat ambiguous, public-private character, the principal offering of these new urban complexes remained the new style of shopping and consumer experience that enclosed centers provided. Promotional materials constantly stressed the novelty, luxury, and comfort of the shopping center, in which shopping became “a delight and a pleasure instead of an obligation and a chore.”Footnote 84 This was shopping decisively recast as a commercial leisure activity, in which visitors were entertained by fountains, sculptures, aviaries, murals, bold colors, and decorative lighting—all intended to invoke “gaiety” and emphasize “the fun in shopping.”Footnote 85 As later theorists of postmodern urban landscapes have stressed, such spectacular spaces became an integral part of the shopping experience in their own right, designed to be consumed visually and experientially alongside the various products available for purchase (figure 7).Footnote 86 Once again, Arndale's postwar operations in provincial English towns firmly prefigured later developments in urban space and experience, which would come to be placed at the heart of broad-based transformations in the culture and economy of cities by the later twentieth century.

Figure 7 Artist's impression of the interior of the Doncaster Arndale Centre, illustrating the emphasis upon spectacle, novelty, and display. Lavish and intricate decor, exhibition, variety, and an assault of brand advertising dominate an environment that postmodern theorists would later dub hyperreal. Source: Arndale Property Trust, “Arndale in Partnership with Local Authorities,” 1966, RIBA, 711.552.1(41/42)//ARN.

Arndale's shopping centers were, in the words of one enthusiastic journalist, “unashamedly luxurious,” and Chippindale was clear that he was selling the postwar shopper an experience and in many respects an escape.Footnote 87 In a paper given to an industry colloquium in the mid-1970s, Chippindale proselytized at length on the detailed internal arrangements and design features “necessary to create the exclusive atmosphere which one expects to find within covered shopping centres.” He argued, “The daily lives of many who support these centres are by and large routine—not necessarily drab, but responsibilities of shopping are generally placed on one section of the community. The already harassed housewife has a routine to follow, and when she leaves her home on a shopping expedition I am sure she does not want to go into dull and colourless surroundings. Surely she is going to prefer an uplifting experience brought about by exciting lighting, fountains, sculpture and other features.”Footnote 88

As is clear from this commentary, the assumption remained in the 1970s that the shopper was generally a housewife. Arndale made much of its offering of comfort, luxury, and convenience to the “harassed housewife,” taking care to incorporate attractions and equipment in its malls “to provide safe play for children,” for example.Footnote 89 Facilities for children were part of the malls’ appeal to busy mothers, but also part of their wider casting as exciting leisure destinations for all the family—even husbands. The new mix of facilities on offer within shopping centers was crucial here, as bowling alleys, pubs, and cafés transformed the shopping trip into a broader commercial leisure experience. Husbands, the Guardian's property correspondent opined, “can become almost enthusiastic about shopping when they can slip into the centre's pub for a quick beer when wives are in the dress shops.” The correspondent suggested, “Visits to the centres are more and more becoming family outings,” and “the company [Arndale] and the local authorities with which they have linked to develop the centres have dramatically advanced the ever-changing styles of retailing in this country.”Footnote 90 By 1978, once Arndale's largest and most ambitious center was open for business in central Manchester, one journalist encountered an “elderly gent” reposing “on an Arndale bench with a leaf or two of luxuriant Arndale greenery whispering in his ear.” “Magnificent,” was this man's assessment, while his companion, also an older male, explained; “It's a good place for a day out . . . I was going to Llandudno till I saw the weather. So I came here.”Footnote 91 The installation of the Arndale shopping experience at the center of British leisure was complete.Footnote 92

Arndale was thus at the forefront of shaping the new leisure habits and consumer experiences of the affluent society. The company furnished towns and cities with elaborate new facilities to service an increasingly affluent, leisured, and shopping-centered society. In doing so, Arndale provided the settings through which ordinary Britons were introduced and accustomed to new forms of consumption. The new vistas of experience opened up by postwar consumer expansion—new horizons of leisure and pleasure, and expanded opportunities for self-cultivation and identity crafting—had to be propagated and pursued somewhere, and the new shopping centers were a key locus.Footnote 93 As well as shaping the cultural forms and psychosocial experience of shopping, Arndale's centers also materially transformed the structure of the retail trade in Britain's towns and cities. Such facilities were expensive, with rental levels and shop layouts geared firmly toward large, nationally organized and more profitable retail chains. As a result, local opposition to these central area redevelopments was almost always led by local retailers facing dispossession and displacement and unlikely to reestablish themselves in the more expensive urban property market that redevelopment invariably produced.Footnote 94 In addition to reshaping the physical environment, then, Arndale centers also remodeled the economic geography and business profile of towns, raising property values and rents and deepening the large retailers’ grip on town centers. Indeed, this was the explicit intent of such redevelopment from the perspective of both local authorities and developers, who sought to raise local property values and install more profitable businesses in central areas.

These political and financial partnerships between public planning authorities and private property developers were not just at the center of Arndale's business model: they were a foundational principle of British urban renewal that was reaffirmed time and again within local plans, central policy directives, journalistic commentary, planning treatises, and parliamentary debates.Footnote 95 Both the rhetoric and the practice of partnership occupied such a prominent place within British urban renewal in the postwar decades that it is surprising how often it has been overlooked in the voluminous literatures on late-century urban entrepreneurialism. Here, public-private partnerships in urban redevelopment are invariably held up as a hallmark of the transformed political economy of the post-1970s era—a product of the neoliberalization of urban policy to be viewed in stark contrast with the state-led planning of the postwar period.Footnote 96 The very existence of the Arndale company and its extensive program of partnership-based, town-center redevelopment stretching back to the reconstruction era undermines this narrative. Indeed, it was Arndale's experiments and engagements with local authorities that staked out what partnership in urban redevelopment actually meant and how it could work in practice. In its 1966 prospectus, Arndale in Partnership with Local Authorities, the company set out in detail what it viewed as the parameters and possibilities of “The Partnership,” outlining the respective roles both parties could expect to play and guiding local officials through the likely procedures.Footnote 97

In 1962, Arndale's activities in this field were discussed in Parliament, where they were held up as a model of best practice. This was a year in which the government issued a key policy directive on urban renewal, which mandated local authorities to work “in partnership” with commercial property developers. In Parliament, the minister of housing and local government pointed to Arndale's developments in Shipley, Jarrow, and Bradford as “examples of partnership between local authorities and private enterprise” that demonstrated “a reasonable and sensible collaboration between public authority and private developer in the area of central renewal.”Footnote 98 Arndale's deep involvement in the transformation of urban space and society thus went to the heart of the political economy of postwar Britain, in which a straitened and tentative embrace of planning and state intervention had to find some accommodation with the burgeoning domain of affluent consumerism and the continued strength of market rationalities and private enterprise. It was the precise nature of the balance among these forces—rather than simply the rise of public planning—that determined the character of Britain's urban renewal regime and the shape of the town center. The fact that redevelopment programs, and redeveloped towns, were dominated by brash and expensive shopping centers, conceived, developed and operated by private property companies with the support of compliant planning authorities, tells us much about the play of these forces as they reshaped postwar cities and social life.

IV

At the moment in which Arndale centers were proliferating throughout the country and entering the public consciousness as a byword for shopping centers in general, the company was experiencing financial difficulties. The relative free-for-all of the property and lending boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s attracted concern within government, which spent much of the 1960s attempting to reassert some of its regulatory authority over the increasingly freewheeling and international City.Footnote 99 Such concerns were by no means confined to Labour, but after 1964, Harold Wilson's government in particular tightened controls on lending and made a number of moves to rein in the property sector. These included the introduction of a new licensing regime for office development—the so-called Brown Ban—and the establishment of a Land Commission that aimed (unsuccessfully, in the end) to “replace the free market in land . . . by a system fairer to the community as a whole.”Footnote 100 Both of these measures were responses to rumbling discontent about the scale and profitability of commercial redevelopment at a time of acute housing shortage, particularly in the capital. Labour's new corporation tax, introduced in 1965, also “hit property companies especially severely” due to their practice of distributing all of their income to shareholders rather than reinvesting it in their business as the tax was designed to encourage.Footnote 101 Property shares thus lost much of their former appeal as easy routes to generous dividends, and company share prices tended to fall across the mid-1960s.Footnote 102

Arndale was caught up in these uncertainties and upheavals and fell foul in particular of the credit squeeze that followed the devaluation of the pound toward the end of 1967. The property development sector was peculiarly dependent on borrowing. It operated according to speculative and extractive logics in which borrowed funds were used to pursue building projects that, if carried off successfully, should provide enough money to pay off the debts and draw out a decent profit on top, which was then quickly extracted and paid out to shareholders. But planning, building, and selling developments was a slow process, and the development business thus entailed taking on enormous debt for long periods, on the strength of those sporadic moments in the future when profits would eventually materialize. This was a risky model that involved arranging multiple loans over varying timescales, and it was further complicated when, for companies like Arndale, many different projects were being pursued at once. In Arndale's case, the company also went on to operate its shopping centers after construction, making the business dependent upon the commercial performance of the new retail facilities and further extending the process of recouping any funds invested. In the credit squeeze at the end of 1967, Arndale was caught without a chair when the music stopped and the company found itself in need of a bailout. This came in the form of a takeover by one of the biggest beasts in the property sector, Town & City Properties, which took control of Arndale early in 1968. Town & City was another young company, formed in 1956, but it had risen fast in the favorable postwar development climate and had wide-ranging interests in town-center redevelopment, shops, industrial sites, and, principally, offices.Footnote 103 When Town & City took over Arndale, the new company became the third-largest property development company in the country, a move that reflected wider trends toward concentration in the sector.

The alliance with Town & City saved Arndale and ushered in the period of its greatest activity in building shopping centers, many now financed with funds from Town & City's principal financial backer, the Prudential Insurance Company. The Arndale Centre brand was now widely known and respected, and the firm's financing difficulties had not altered the continued strength and potential of its retail-led urban redevelopment model. But the involvement with Town & City also embroiled Arndale in tumultuous events in the 1970s that underscored the connections between Britain's property and urban redevelopment regime, the financial sector, and national economic management. The early 1970s witnessed a spectacular property boom in Britain, as Edward Heath's Conservative administration stoked up the economy through tax reductions, public spending, and an extraordinary liberalization of credit and deregulation of banking. Heath's government also rolled back Labour's tentative efforts to create a more regulated and less marketized urban property regime. The thinking behind the so-called Barber Boom was that this free-flowing credit would find its way into sensible industrial investments and generate long-term growth. Given the history and proclivities of the British financial sector, this was somewhat optimistic. Instead, there was an enormous expansion of so-called secondary banking as a plethora of new financial institutions entered the deregulated money markets, borrowing funds from other banks on a short-term basis to lend or invest in sectors that promised the highest returns—principally, property.Footnote 104

Anthony Barber's overflowing credit thus fueled an extraordinary property boom in the early 1970s as the new banking businesses poured money into property. Bank advances to the property sector rose sevenfold between 1971 and 1974, from £360 million to £2,600 million, and the value of property company shares almost doubled in one year between 1971 and 1972.Footnote 105 The Economist concluded in 1972, “The property market has gone somewhat mad.”Footnote 106 Naturally this boom was followed by a bust, which came at the end of 1973 with the oil price shock and the Heath government's abandonment of its “dash for growth.”Footnote 107 Demand and credit dried up, and the frantic property business—completely dependent upon easy money—was particularly hard hit. Arndale's parent company was the biggest casualty in the property sector; after embarking on an ambitious global program of expansion and development, Town & City came crashing to earth and had to be bailed out and refinanced repeatedly across the rest of the decade. Personal fortunes were also lost. The estate agent Edward Erdman suggests that Town & City's chairman saw the value of his shares decline from £3 million to £800,000, while Sam Chippindale reportedly “found his fortune on paper had almost disappeared.”Footnote 108

Despite these tumultuous economic events, the Arndale development model rumbled steadily on. The long timelines for planning and construction on individual projects meant that, despite the crash, many ongoing developments had to carry on regardless. In Manchester, where the largest Arndale center was under construction in the early 1970s (figure 8), Chippindale had first begun buying up properties in the area in the mid-1950s, and the prolonged planning process had taken up most of the 1960s. By the time of the crash in 1973, a vast swathe of Manchester's central shopping district had already been demolished in anticipation of the new center. The show simply had to go on. The mammoth new complex was opened in stages from 1976, culminating in a prestigious royal opening in 1979. As part of this ceremony, Princess Anne spent “more than an hour in the Centre meeting local dignitaries and people involved with the Centre” and was directed in particular to the new Boots and W. H. Smith stores, which were the largest in the country.Footnote 109

Figure 8 Artist's impression of the mammoth Manchester Arndale Centre, which overhauled a fifteen-acre expanse of the extant city center in the 1970s. Source: Town & City Properties Limited, Report and Accounts (1971), P&O/35/940, National Maritime Museum, London.

Although shifting economic and political conditions and a general loss of faith in large-scale planning projects meant the tide had turned away from city-center redevelopment on this scale, for the city of Manchester the Arndale development was there to stay. Occupying fifteen acres, the physical footprint alone of this new complex was very substantial indeed. The shopping center was the largest in Europe, with over two hundred new shops, a nineteen-story office block towering over the city, a large new market, and “a bus station that will disgorge 40,000 passengers into the marble malls.” It was a sprawling and sophisticated piece of commercial infrastructure, with “miles of delivery and service areas under the main shopping level,” “armies of cleaners,” “a labyrinth of corridors and lifts,” “a 24-hour security system involving closed circuit television,” and “a team of security guards in radio contact with the main security room.” The operation of such a center was no simple task; it required sophisticated new management techniques and left large portions of the city's central areas to be overseen and policed by commercial actors. One of the Manchester Arndale's new managers described it as “a town within a city.”Footnote 110

While the sheer scale of Manchester's Arndale center made it unusual, the introduction of similar commercial facilities into the heart of Britain's town and city centers continued. As in the postwar period, Arndale's projects benefited hugely from the sympathetic deployment of planning powers and from integration within state-sponsored programs of development. In 1978, a new Arndale center opened in Wellingborough, a London overspill town in Northamptonshire, “planned and . . . built in partnership with the Local Authority.”Footnote 111 Wellingborough had been selected as an expansion town by central government, with a program for major population expansion across the 1980s and 1990s. Town & City was accordingly turned to for an Arndale center, with the necessary finance coming from the National Coal Board Pension Fund. “In true Arndale tradition,” the company reported, “the centre provides cool, light, safe, shopping facilities for families in an environment of terrazzo floors, clusters of modern lights and containers of plants.”Footnote 112 Just as in Jarrow in the 1960s, place names and decorative motifs made frequent nods to local history and commercially instrumentalized heritage. And in a further royal flourish, the Duke of Gloucester opened Wellingborough's new center, accompanied by Town & City's chairman and various local dignitaries. In Eastbourne, on the south coast, Town & City was selected again in the late 1970s to carry out a £24 million overhaul of the central shopping district and install an Arndale center in “the finest retail position in the town centre.” In a now tried and tested model, this scheme relied on Eastbourne Corporation providing the necessary land to Arndale, while an insurer—in this case Legal & General—put up the money. The Eastbourne Arndale opened in 1981, and Arndale's managing director claimed it offered “a chance to show that the Arndale shopping centres will be the best in England for shoppers and traders alike in the next decade as they have been in the last.”Footnote 113

V

Arndale thus weathered the economic storms of the 1970s surprisingly well, aided by a compliant planning regime and lucrative public contracts, and its centers continued to transform the public space and public culture of urban Britain. Carefully choreographed royal openings were just the beginning, as the centers became sites in which a demotic new culture of shopping and commercial entertainment was cultivated. Rolling programs of attractions, exhibitions, and events were instigated to promote the centers and draw in a hesitant and unfamiliar British shopping public. Christmas shopping in the centers was vigorously promoted as a cultural institution, with carol concerts, festive decor, and outsize Christmas trees.Footnote 114 Fashion parades showcased the latest high-street clothing lines (and were euphemistically described by Town & City as “appealing to both sexes”). Celebrity appearances and endorsements were also welcomed. A crowd of one thousand turned up at the Stretford Arndale on 12 October 1971 to hear Muhammad Ali stand in Tesco's and say, “I am the greatest . . . and so is Ovaltine.” Footnote 115 Crass “Miss Arndale” contests were another attraction in many centers, where local young women traded their vital statistics for a chance to win £100. The populist politics of these cultural and commercial projects was evident at Poole, where a mid-1980s extension to the Arndale center was christened “Falklands Square,” apparently “due to the Royal Marines connection with Poole.”Footnote 116 The chairman of Town & City by this time was Sir Jeffrey Sterling, who served as a special advisor to the Conservative governments of the 1980s and was ennobled by Margaret Thatcher in her retirement honors. Sterling had been a key organizer of the queen's 1977 Silver Jubilee celebrations and was also head of the P&O shipping line (which Thatcher described to him fondly as “the very fabric of the Empire”).Footnote 117 In a further touch of populist monarchism in the Jubilee year, £1,000 was spent at the Wandsworth Arndale on a nine-foot-high “crown” decorated with five thousand chrysanthemums, which was hoisted onto the roof of the center, “floodlit on a revolving turntable to welcome the Queen on her visit to Wandsworth.”Footnote 118