Recent years have seen an increase in the number of volumes Antiquity receives from publishers based in the USA, presenting archaeology in North and South America, as well as farther afield. The range of these publications is testament to the extent and diversity of archaeological research being undertaken in the Americas. This NBC features a selection of books from U.S. publishers as a window on the diversity of approaches in American archaeology. With a focus on North America, the volumes highlight research from the Pre-Columbian period to the Cold War era and through to the present day.

Beginning from the premise that childhood is a cultural construct that varies over time and across societies and cultures, and that the state of childhood is essentially relational to adulthood, Jane Eva Baxter examines how the archaeology of childhood has been treated in studies of the recent past in the USA. Baxter opens The archaeology of American childhood and adolescence with a chapter that considers previous approaches to childhood, many of which take a declensionist view, assuming that childhood has been continually eroded. There are some complex issues at the heart of this topic, including what an American childhood is, or was, categorising identities that are by their very nature diverse and fluid. These are dealt with elegantly and disentangled to allow the identification of five emergent themes in the literature that are used to problematise the discussions in the following chapters. These themes are as follows: risk and opportunity—the balance between children's freedom to choose their own futures vs the increasing limits on that freedom that come with greater parental safeguarding in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; diversity—recognising the plethora of cultures and traditions that sit under the umbrella of ‘American’ including children from, among others, Native American, European immigrant and African (enslaved and freed) communities; consumerism—which relates directly to material culture studies; the spaces that children inhabit in both the domestic and institutional spheres; and the disruption of childhoods as a result of war.

This volume aims to forefront “children as actors, interpret archaeological sites with children present in the past, and consider the relationships between children and adults as dynamic and multifaceted” (p. 17). This aim is met over the following five chapters, which are organised thematically rather than chronologically. These chapters deal with different aspects of childhood, including living spaces, child-focused institutions and children's bodies. The final chapter deals with the material culture of contemporary childhood, because “all scholarship on childhood in the past is situated in the present, infused with present-day ideas and information, and reflective of the concerns and interests of the contemporary world” (p. 152).

Chapter 2 engages with various studies of material and social histories of childhood and adolescence in America that demonstrate the visibility of children in the archaeological record during different times from the colonial period through the early republic, the Industrial Revolution and the twentieth century. These social histories include studies of children in enslaved communities. This chapter charts changes in children's spaces, play, education or employment and family demographics, especially in relation to falling birth rates. Material culture and the evidence for children is also interrogated. The treatment of children's material culture continues in Chapter 3, which relates this to children's spaces in nineteenth- and twentieth-century domestic rural, urban and plantation sites, as well as in industrial and military communities. Baxter notes that many archaeological reports remove agency from children because of “the tyranny of toys” (p. 93), that is, the exclusive focus on bespoke play objects that narrows investigation to only one aspect of children's lives, excluding other facets of play such as imaginative play involving everyday objects. In fact, Baxter argues, the artefacts identified as representing the ideals of childhood were often used as agents to transform and isolate children, so that they are better read as representing “a struggle for the hearts and minds of children” (p. 94).

Chapter 4 considers the archaeology of institutions and ways in which their structure and appearance were used to communicate messages about the norms of society and who does—and who does not—conform to them. Here Baxter considers schools and orphanages, but also takes an unflinching look at Indian boarding schools and Japanese internment camps (the latter used to accommodate Japanese and Japanese-American families after the attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941), demonstrating how supposedly philanthropic policies reflect cultural ideals of what childhood should be. This is particularly apposite as Canada mourns the recent discovery of the bodies of 215 children in a mass grave at the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

The treatment of children's bodies and the commemoration of children are dealt with in Chapter 5, which investigates attitudes to the deaths of children as reflected in mortuary practices and the material culture of memorialisation. Baxter concludes that studies of the commemoration of children simultaneously highlight the diversity of childhood experiences and offer a window on the equality and disparities of life in America's past.

Chapter 6 charts the shift in modern childhood that moves children from devotees of a patriarchal family unit to the heart of the family as beings of devotion, around whom family life and finances revolve. In this final chapter, Baxter calls for, and indeed begins, a move towards a deeper exploration of the biases that hamper archaeological understandings of childhood in the past. This excellent volume demonstrates how archaeological evidence can be used to understand better the lives of children, and what this can contribute to the history of the USA.

In the eye of the beholder

The cosmos revealed is an impressively produced volume with an equally impressive aim, namely to present the entirety of the rock art at Painted Bluff, Alabama, along with detailed descriptions, so that it is accessible to all. The book seeks to contextualise the art in all aspects of its reception, from its creation by Native Americans to its landscape situation, its treatment in the history of research and in the challenges of its preservation. The volume is nicely structured in ten chapters that detail all aspects of the site and the archaeological and conservation work undertaken there.

Acknowledging that Painted Bluff was known to the Native American community for centuries before Europeans arrived, Chapter 1 details the first European-recorded description of the site, published by John Haywood in the nineteenth century, and follows the literary trail chronologically through the omission of the site from investigations undertaken by the Tennessee Valley Authority in the 1930s, in advance of a dam project, to the work of James Cambron and Spencer Waters in the 1950s, only after which was the site included on maps. This chapter also introduces the work of the authors at Painted Bluff, undertaken over the course of 15 years.

Chapter 2 brings together the geological and topographical nature of Painted Bluff to contextualise the location of pictographs and to understand the character of the ‘place’ that was created by past human activity. Archaeological survey and the collection of finds from the ledges, test pits in targeted areas and investigation of cave 1MS427 are documented together with the selection of finds, which, alongside radiocarbon dates, place the use of the site between 800 BC and AD 1500. Recording methods and quantitative data are detailed in Chapter 3, which presents both a narrative describing the fieldwork and explaining the spatial recording, and a catalogue of the number of images by area and by motif.

The images themselves are the focus of Chapters 4–6, which provide detailed descriptions of the shapes, signs and figures and their colour and position (Chapter 4); the stratigraphy of the images, how this was determined, overlapping sequences of glyphs and evidence for continued interaction with particular images over time (Chapter 5); and the non-invasive scientific analysis undertaken to determine the paint chemistry (Chapter 6). This latter chapter includes a discussion on the techniques for analysing pigments and the methods of making ancient paints. The recipes are revealed to be simple but effective and not dissimilar to those used in other prehistoric paintings, such as those at Lascaux. Measures to conserve the site are reported in Chapter 7, and a project to remove the modern graffiti that compromised the spiritual significance of the site for the descendant Native American groups is detailed in Chapter 8.

The culmination of the research, Chapter 9, offers an interpretation of the imagery at Painted Bluff, including descriptions, production techniques, spatial distributions and discussion of the rock face as a conceptual boundary between the visible natural world and an invisible spiritual realm. The authors conclude that “the structured composition of rock art at Painted Bluff is a depiction of the spiritual universe where its artists lived” (pp. 199–200). While the authors acknowledge that their interpretation is academic and not cultural, the research has been undertaken with cultural sensitivity. From the Foreword by LaDonna Brown of the Chickasaw Nation, to the interpretation of the site as a cosmogram of the Mississippian Native American view of the universe, the book, and indeed the research it presents, is informed by the Native American community for whom the site is a powerful place.

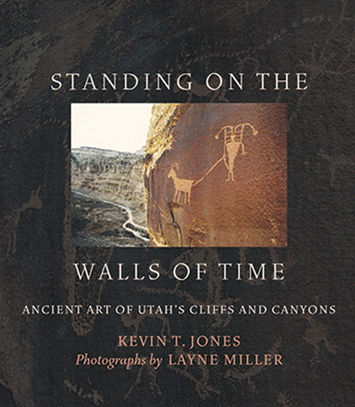

Almost 3000km to the north-west of Painted Bluff lie the Utah cliffs and canyons that provide a canvas for more ancient rock art, presented in Standing on the walls of time by author Kevin Jones and photographer Layne Miller. In a break from traditional approaches and in a very different vein to The cosmos revealed, this volume advocates “a much simpler, more human approach—to view the work of ancient artists purely as art […] on more of an emotional, as opposed to intellectual, level” (p. 3). The book is intended to showcase the humanity of the ancient artists and the range and depth of the imagery. The art is organised broadly chronologically through the chapters. Choosing not to analyse the artwork within an academic framework, the author takes the view that the best way to understand the humanity of the artists is through their expressive art, even if we are unable to decipher the meanings and symbols contained therein. This approach, however, still relies on the modern notion that these images should be conceptualised as ‘art’.

The volume is divided into 14 chapters, all of which are brief in terms of text, privileging the photographs, which are allowed to convey the impact of the images. The first two chapters are by way of an introduction, with Chapters 3–4 following up with a discussion of the ways in which art can project meaning and on the nature of rock art in particular as a medium. Chapters 5–6 briefly discuss the periods that the rock art may represent, given broadly as: Palaeo-Indian 10 000–7000 BC; Archaic 7000 BC– AD 1; Formative or Fremont/Anasazi AD 1–1300; and Later Prehistoric and Historic AD 1300–1900. Chapters 7–12 deal with various motifs used in the rock art, such as ghost figures, anthropomorphs, sheep and hunting scenes. The final two chapters reflect on the connection that art provides between creator and viewer, looking to the future and the issues of preserving the Utah rock art.

The volume is beautifully illustrated by Layne Miller's high-quality photographs, which showcase the rock art in full colour, and, despite the brevity of the text, the author's passion for the images and their conservation is writ large on every page.

Yooks and Zooks

In 1984 Theodore Seuss Geisel published The butter battle book as a parable for children on arms races and mutually assured destruction (Seuss 1984). While the stalemate of the Yooks and the Zooks offers children a window on the futility of nuclear war, Todd Hanson demonstrates what an archaeological approach can reveal about life in the Cold War era. Beginning from the premise that “what we can learn from the Cold War depends upon how we study it” (p. xx), Hanson takes the reader through the three approaches that have dominated its study thus far (Chapter 2). These are: conflict archaeology, which focuses on the material remains of scenes of conflict including battlefields, defensive fortifications and technologies, osteological studies of combatants and, more recently, conflict as a social phenomenon and the multiple and mutable meanings that are embodied in artefacts of conflict; archaeology of the contemporary past, which is concerned with the immediate past and events that are within living memory; and archaeology of science, which despite its apparently narrow classification in fact encompasses the entire process so that, in addition to scientific artefacts, it also engages with landscapes, places, instruments and associated objects.

Driven by a federal government mandate, the archaeology of the Cold War in the USA has, to date, been dominated by processual approaches that were designed to meet a need for cultural resource management. Because of this and despite a certain amount of work on Cold War archaeology, there has traditionally been a lack of theoretical analysis of the archaeological record that could inform the “explorations of the underlying social, psychological, and ideological aspects of Cold War materiality” (p. 27); it is these aspects that Hanson aims to develop. Hanson argues that to understand fully how the Cold War intersected with social, scientific, political and material life in North America, it is necessary to understand the emergence of the Cold War built landscape, which is the subject of Chapters 3ؘ–4. Chapter 3 identifies three discrete periods of the Cold War: evolution—the early Cold War 1945–1957; revolution—the middle Cold War 1958–1975; and resolution—the late Cold War 1976–1989. This is followed in Chapter 4 by ten case studies of Cold War archaeology mostly focused on North America, but also including Soviet missile sites on Cuba and the underwater study of the sunken fleet at the nuclear weapons testing location (and UNESCO World Heritage site) of Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The case studies, which include testing sites, development facilities and peace camps, demonstrate how future studies of Cold War materiality could usefully employ theoretical constructs borrowed from each of the three fields of study detailed in Chapter 2.

In Chapter 5 Hanson turns to the issues that beset the study of Cold War archaeology, not least secrecy and access—an issue that the reader will no doubt have wondered about—but also the safety and the stewardship of the sites. The chapter details the problematic nature of a painfully slow declassification process, the nature of atomic tourism and ‘dark tourism’ (recreational travel to sites associated with significant human tragedy or the desire to experience vicariously the danger and fear of being in an atomic landscape) and the significant knowledge and experience that Cold War veterans and especially atomic veterans have to offer Cold War archaeology. Hanson calls for veterans to be more involved in the study and management of Cold War heritage.

Hanson describes The archaeology of the Cold War as “a book about what archaeologists have learned about the Cold War from Cold War sites and artifacts” (p. xx); in reality it is much more. It synthesises research on Cold War archaeology, resituates it within a humanised theoretical framework and broadens discussion of the subject to demonstrate how the Cold War and its material remains have shaped contemporary North America and how America chooses to deal with its atomic past.

Leaving North America behind to consider how another nation deals with its past is Brent Maner's Germany's ancient pasts, which considers interpretations of Germany's domestic archaeology from the eighteenth to twentieth centuries. Maner challenges the narrative that archaeological interpretation in Germany was driven predominantly by nationalist ideology and takes a broader view of the development of archaeology—particularly of prehistory and early history in the region—to consider the longer chronological trajectory and socio-political context. This approach reveals that other motivations were at work apart from nationalism. The volume comprises an Introduction followed by eight chapters divided into three parts, dealing respectively with ‘The Discovery of Germany's Ancient Pasts’, ‘The New Empire and the Ancient Past’, and ‘Between Science and Ideology’. Part I opens with a synthesis of the ways in which ancient sources were used before the eighteenth century in Germany to understand the country's prehistory (Chapter 1). The chapter goes on to discuss the beginnings of archaeology in the eighteenth century and how this altered the approach to prehistory. Chapters 2–3 document early archaeological work and how it led antiquarians to begin to link time and place through their discoveries.

In Part II, Maner considers three approaches to the past that existed in parallel in nineteenth-century Germany. The beginnings of anthropology challenged the nationalist narratives in the vaterländische Altertsumskunde (study of the fatherland's antiquities) movement, as ideas began to develop about patterns of migration and the mixing of populations (Chapter 4). This chapter also considers the role of the time revolution, the work of Rudolf Virchow and the foundation of the Deutsche Anthropoligische Gesellschaft in the orientation of prehistory. Chapter 5 charts the second approach—the rise of regionalism and local archaeology in the later nineteenth century. This led to local museums and a focus on regional rather than national interpretations. The nationalist interpretation is considered in Chapter 6, which explores the use of historical fiction to create a coherent linear past that accounted for contemporaneous cultural traits.

In Part III, Maner turns to the twentieth century and highlights the achievements in prehistoric archaeology in Germany that were concurrent with the better-known radical racist and nationalist agenda during the Weimar Republic and the Third Reich. These alternatives to nationalism provided a more positive framework for archaeology in the post-war period.

Maner arrives at three broad conclusions: these are that antiquarians were not focused on national traits and, in fact, more often argued for the emergence of local and regional identities; that it was the frustrations of certain scholars at the lack of a full chronology linking the ancient past with the modern nation that drove them to paint the archaeological past as the prehistory of the German people and that these scholars were a minority; and that the decentralised nature of archaeological research in Central Europe stands in opposition to the völkisch nationalism, which idealised the myth of a pure original German nation, and Nazi ideology that has received so much attention. Museums in Germany are testament to the focus on local and regional identity. Maner's volume offers a thorough and eminently readable historiography of Germany's domestic archaeology from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries.

Although a small and highly varied snapshot of archaeological research in and on America, these volumes demonstrate its vibrancy and its chronological and geographic breadth, framing not only ancient and modern societies, but also revealing how the latter have dealt with the former. Maner's book, as the only volume dealing with archaeology outside of the USA, offers a useful comparative view of how nationalism in archaeology played out in a European context, compared with that of the USA. While the volumes in this NBC deal with sites that are predominantly in the USA, their themes—childhood, the Cold War, rock art—are universal. Even if the focus of the studies is solely U.S.-based, these volumes present insightful North American perspectives on global phenomena.

This list includes all books received between 1 March 2021 and 30 April 2021. Those featuring at the beginning of New Book Chronicle have, however, not been duplicated in this list. The listing of a book in this chronicle does not preclude its subsequent review in Antiquity.