Impact statement

Refugees are a large population with special mental health care needs which are nowadays not adequately addressed by most of the host countries. Experiences before, during, and after flight increase psychological distress and contribute to a high prevalence of mental disorders. The resulting high need for mental health care is generally not reflected in the actual mental health care provision for refugees. Potential reasons for low utilization include language difficulties, limited treatment offer, and lack of knowledge about mental health care systems. A possible strategy to close this gap might be to offer smartphone-delivered mental health care. Since most refugees own a smartphone, the smartphone represents a great health care opportunity. The current systematic review gives an overview of the existing stand-alone smartphone-delivered interventions for mental health problems in refugee populations. We identified nine interventions for adults and three for adolescents and young refugees. The review enables the audience to identify treatments in different languages, targeting different mental problems, and offering varying amounts of support. This helps persons affected, persons working with refugee populations, and stakeholders to identify the most fitting interventions for specific persons or populations. In the course of the summarized trials, about 400 refugees were provided with smartphone-delivered mental health care. The results show that the different interventions were able to improve single aspects of mental health and well-being. Still, we identified room for improvement in the efficacy and effectiveness of smartphone-delivered interventions, the involvement of post-migration stressors in the treatment, and data safety. This knowledge helps scientists and stakeholders to decide which steps should be taken next to fully exploit the potential of smartphone-delivered mental health interventions for refugees. For instance, we need more knowledge about effective treatment elements, facilitating characteristics to improve their use, and barriers that hamper the wide use in refugee populations.

Introduction

According to the United Nations, there were an estimated 84 million forcibly displaced people worldwide in 2021 (UNHCR, 2022a). Political developments and armed conflicts, as well as climate change, have recently led even more people to leave their home countries to seek asylum elsewhere (e.g., UNHCR, 2022b,c). Experiences before, during, and after flight increase psychological distress and the risk of various mental disorders, with a recent umbrella review identifying depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as the most common mental disorders among refugees, accounting for up to 40% of all mental disorders in this population (Turrini et al., Reference Turrini, Purgato, Acarturk, Anttila, Au, Ballette, Bird, Carswell, Churchill and Cuijpers2019). Additional post-migration stressors frequently experienced in the host countries (e.g., discrimination, poor living conditions, new cultural context, and language barriers) pose further challenges for refugees and are also associated with worse mental health (Tinghög et al., Reference Tinghög, Malm, Arwidson, Sigvardsdotter, Lundin and Saboonchi2017; Malm et al., Reference Malm, Tinghög, Narusyte and Saboonchi2020). In general, refugees show a low level of well-being (Leiler et al., Reference Leiler, Bjärtå, Ekdahl and Wasteson2019; Beza et al., Reference Beza, Mavrodi, Kyratso and Aletras2022). Despite the correspondingly high need for diverse psychosocial interventions and treatment, the actual mental health care and its use in the host countries is low (Satinsky et al., Reference Satinsky, Fuhr, Woodward, Sondorp and Roberts2019). Potential reasons for low utilization include structural barriers (e.g., language and cultural barriers, and lack of health care options; Kiselev et al., Reference Kiselev, Morina, Schick, Watzke, Schnyder and Pfaltz2020a) and personal barriers such as mental health stigma, avoidance of symptoms, and limited mental health literacy (Shannon et al., Reference Shannon, Wieling, Simmelink-McCleary and Becher2015; Kiselev et al., Reference Kiselev, Pfaltz, Haas, Schick, Kappen, Sijbrandij, De Graaff, Bird, Hansen and Ventevogel2020b). Moreover, at first sight, adequate mental health care for refugees might appear burdensome for the host countries and its practitioners (e.g., due to additional costs for interpreters; Gadon et al., Reference Gadon, Balch and Jacobs2007). Thereby, benefits and lower costs in the long term are frequently not considered (Brandl et al., Reference Brandl, Schreiter and Schouler-Ocak2020). Therefore, there is an urgent demand for innovative treatment options that address both the diverse needs of refugees as well as cost-effectiveness and scalability for the host countries.

Smartphone-delivered mental health interventions

Smartphone-delivered interventions may be a promising approach to close this treatment gap for refugees. Since most people, and especially refugees, own a smartphone rather than other digital devices, the smartphone represents a great health care opportunity (Casswell, Reference Casswell2019). Smartphone-delivered interventions like applications (‘apps’) or internet-based interventions that can be implemented on smartphones have the potential to directly address some of the strongest barriers to help-seeking in refugee populations. Such interventions are flexible in terms of time and place, can be offered in different languages, thus reaching a high number of people, and their anonymous usage might reduce the fear of mental health stigma (Hilty et al., Reference Hilty, Chan, Hwang, Wong and Bauer2018; Burchert et al., Reference Burchert, Alkneme, Bird, Carswell, Cuijpers, Hansen, Heim, Harper Shehadeh, Sijbrandij and Van’t Hof2019; Schmidt-Hantke et al., Reference Schmidt-Hantke, Vollert, Hagner, Beintner, Hütter, Nitsch, Jacobi and Waldherr2021).

While these advantages of smartphone-delivered interventions seem compelling, there is a need to investigate their effectiveness, (cost-)efficiency, usability, and acceptability in refugee populations. Currently available smartphone-delivered interventions differ widely in their cultural and contextual adaptations (Spanhel et al., Reference Spanhel, Balci, Feldhahn, Bengel, Baumeister and Sander2021) and in their treatment approach and range of indications (e.g., targeting one specific problem vs. a transdiagnostic approach). Thus, some interventions target psychopathology while others take a more salutogenic approach, with the aim of improving quality of life. Beyond this, interventions can be unguided, offering treatment without personal contact or individualized feedback, or guided, offering varying amounts of personal support (Andersson, Reference Andersson2018; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Cuijpers, Ebert, McKenzie Smith, Coughtrey, Heyman, Manzotti and Shafran2019). Smartphone-delivered interventions also differ in their design, content presentation (e.g., text- or video-based), usability, and other user experience aspects (cf. Chandrashekar, Reference Chandrashekar2018). Lastly, data security has been identified as an important aspect of refugees’ utilization of internet-based mental health interventions (Burchert et al., Reference Burchert, Alkneme, Bird, Carswell, Cuijpers, Hansen, Heim, Harper Shehadeh, Sijbrandij and Van’t Hof2019) and should therefore be particularly emphasized (Liem et al., Reference Liem, Natari and Jimmy, Hall2021). All of these characteristics of smartphone-delivered interventions might contribute to differences in their effectiveness and efficacy for specific target populations.

The present review aimed to provide an overview of existing smartphone-delivered mental health interventions, their specific characteristics, and evidence on clinical and nonclinical outcomes explicitly for refugee populations. The latest literature already encompasses some reviews focusing on smartphone-delivered interventions for refugees, but these also included other populations, topics, or internet-based interventions in general. For instance, Wirz et al. (Reference Wirz, Boettcher, Knaevelsrud and Heeke2021) described digital mental health interventions for Arabic- and Persian-speaking persons remaining in their home countries and refugees elsewhere. The authors identified nine app- and web-based mental health interventions for anxiety, depression, and PTSD; two of these were evaluated and one achieved a significant reduction in the primary outcome. Liem et al. (Reference Liem, Natari and Jimmy, Hall2021) summarized 16 digital mental health interventions for immigrants and refugees. These interventions covered both forcibly and voluntarily migrated populations worldwide and were delivered via all digital devices (e.g., computers) rather than primarily via smartphones. The participants reported general satisfaction and positive attitudes toward digital mental health care interventions, but ethical standards were poorly implemented and reported, and the authors identified mental health stigma and lack of technology literacy as the main challenges. Spanhel et al. (Reference Spanhel, Balci, Feldhahn, Bengel, Baumeister and Sander2021) conducted a systematic review on cultural adaptation of internet-based interventions for marginalized groups worldwide, and identified 17 components regarding content, methods, and procedural components eligible for cultural adaptation in the context of internet- and mobile-based mental health interventions.

The aforementioned reviews indicate that refugees can be reached through internet-based and smartphone-delivered interventions. However, to date, no review has included an overview of all existing interventions for refugees that exclusively utilize smartphones.

Aims of the systematic review

The aim of the current systematic review was to provide an overview of existing smartphone-delivered mental health interventions that explicitly address the needs of refugee populations (e.g., dealing with experiences in the home country and during flight, post-migration stressors in the host country). Based on the PICO criteria (Population – Intervention – Comparison – Outcome; McKenzie et al., Reference McKenzie, Brennan, Ryan, Thomson, Johnston and Thomas2019), we identified interventions and study reports targeting forcibly displaced persons of all ages not living in their home countries as the study population. We included published and unpublished information (e.g., peer-reviewed studies, gray literature, and informal communication) on smartphone-delivered mental health interventions. To summarize as much information as possible, we included interventions and research reports on any stage of an intervention’s development (e.g., study protocols, feasibility studies, pilot studies, and usability studies) and evidence testing. Interventions to improve any aspect of mental health or quality of life were included. Specifically, the following research questions were addressed:

-

1. Which smartphone-delivered mental health interventions are available for refugees?

-

2. What are the clinical outcomes and efficacy of these smartphone-delivered mental health interventions?

-

3. What are the nonclinical outcomes of these smartphone-delivered mental health interventions (e.g., feasibility, appropriateness, acceptance, and barriers)?

-

4. What are the dropout rates and reasons for dropout of the different interventions?

-

5. To what extent do the smartphone-delivered interventions consider data security?

Methods

The current systematic review was conducted and reported as recommended by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., Reference Liberati, Altman, Tetzlaff, Mulrow, Gøtzsche, Ioannidis, Clarke, Devereaux, Kleijnen and Moher2009; Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl and Brennan2021; see Online Supplement 1 of the Supplementary Material for PRISMA checklist). The systematic review was not registered and no register protocol exists. During the process, no modifications were made to the initially agreed search procedure or methods as described below.

Eligibility criteria

Data points were included if they (a) reported smartphone-delivered interventions aiming to improve mental health or quality of life (b) in refugee populations not living in their home countries. Regarding the study design, (c) primary studies such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods, feasibility or pilot studies, and peer-reviewed study protocols as well as unpublished information (d) available between 01/2000 and 04/2022 (e) in the English or German language were considered. We explicitly chose not to restrict the countries of origin and resettlement countries or study participants’ age, mental disorders, and symptom severity. Data points were excluded if they (a) did not include smartphone-delivered interventions, for example, tele- or videoconferencing interventions, online assessments and diagnostics, virtual reality (VR), ecological momentary assessments (EMAs), and ecological momentary interventions (EMIs), or were not aimed at improving mental health or quality of life, for example, strengthening social support. Interventions targeting (b) populations like voluntarily migrated persons, second-generation immigrants, internally displaced or indigenous people were excluded. Furthermore, (c) reviews, meta-analyses, commentaries, and (d) data points published or available before 01/2000 or after 04/2022, and only available in (e) languages other than English or German were also excluded.

Search strategy

To identify eligible articles, two researchers (R.E. and L.N.) independently searched PubMed and the results of the search engine EBSCOhost which was used to simultaneously search the databases CINAHL and MEDLINE with Full Text, APA PsycArticles, and APA PsycInfo. The applied search terms (see Online Supplement 2 of the Supplementary Material) were a combination of relevant keywords related to smartphone-delivered mental health interventions, refugee populations, and various mental health outcomes. At the same time, the somatic conditions stroke and cancer were explicitly excluded as keywords due to their high coincidence with the search term ‘survivor’ and a consequently large number of findings not fitting the scope of the review. The search was limited by applying filters on publication date and type of study report. The literature search was realized on April 30, 2022. To further reduce potential bias, additional search strategies were applied, and gray literature not previously peer-reviewed (see Conn et al., Reference Conn, Valentine, Cooper and Rantz2003) and unpublished information were identified. Therefore, we contacted leading experts in the field of digital and smartphone-delivered mental health, psychological treatment for refugee populations, and transcultural clinical psychology. Next, citation searching was applied and the reference lists of all included studies, previous systematic reviews, and systematic reviews on related topics were systematically searched. Finally, additional databases for preprints (PsyArXiV and OSF), clinical registrations (US and European clinical register), and conference volumes of the WCCBT 2019 (Heidenreich and Tata, Reference Heidenreich and Tata2019; Heidenreich et al., Reference Heidenreich, Tata and Blackwell2019) and the Swedish Congress on Internet Interventions 2022 (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Vlaescu and Aminoff2022) were systematically searched. Identified studies and data sources were only included if published or available before April 30, 2022.

Selection process

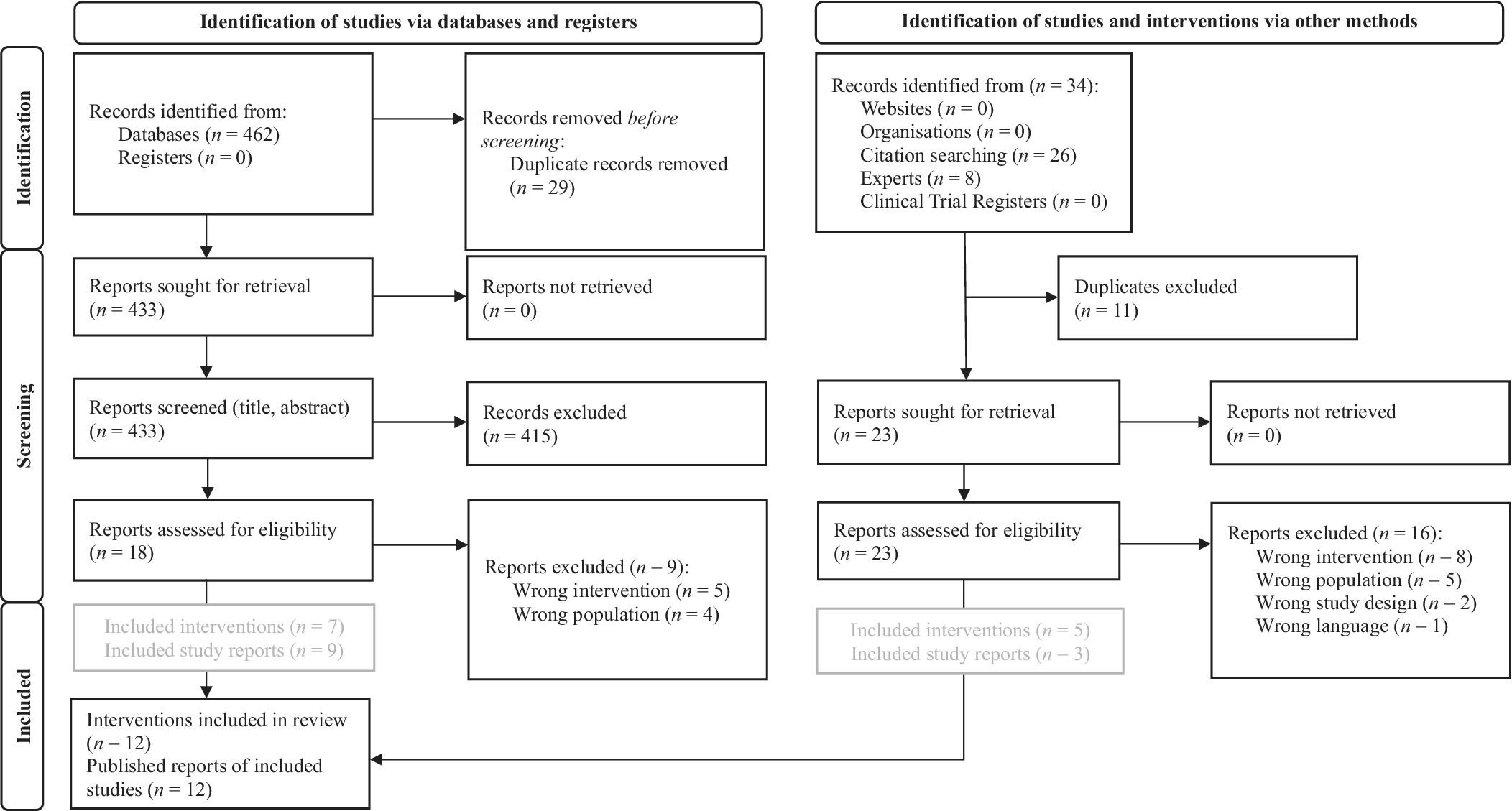

All references from PubMed and EBSCOhost were imported into the online open-source software Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid2016) for initial screening of titles and abstracts. Rayyan automatically identified potential duplicates, which we checked and removed manually where necessary. Subsequently, R.E and L.N. screened titles and abstracts independently. Screening followed a hierarchical approach, applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria as presented in the Online Supplement 3 of the Supplementary Material. Next, initially included articles, gray literature, and unpublished data sources were screened based on their full texts by R.E and L.N. independently, which resulted in the ultimately included data points. Disagreements regarding inclusion were discussed with a third researcher (M.B.) and resolved by consensus. To control for interrater reliability, Cohen’s κ was calculated (Cohen, Reference Cohen1960). For a detailed description of the selection process, see the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1 and Online Supplement 3 of the Supplementary Material.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for the systematic review about the searches of databases, registers, and other sources (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl and Brennan2021).

Quality assessment

For quality assessment, studies were grouped by study type. Only data points offering any type of study report were rated regarding general quality aspects. Unpublished and informal information was not assessed. The quality assessment sought to structure the systematic evaluation of included studies and support the systematic identification of strengths and weaknesses of published studies in this field. To adequately address the diversity of included studies, each study type was evaluated by a well-established and standardized quality assessment tool identified by the Equator network (2021). For RCTs, the CONSORT checklist was applied (Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Altman and Moher2011); for pilot RCTs and feasibility studies, the CONSORT 2010 extension was used (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Chan, Campbell, Bond, Hopewell, Thabane and Lancaster2016); for study protocols, the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for International Trials (SPIRIT) was applied (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Tetzlaff, Altman, Laupacis, Gøtzsche, Krleža-Jerić, Hróbjartsson, Mann, Dickersin and Berlin2013); and for qualitative studies, the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) were used (O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed and Cook2014). All quality assessments were undertaken individually by R.E. and L.N. Observed agreement (P 0) was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the total number for each data extraction item (Cohen, Reference Cohen1960).

Data extraction

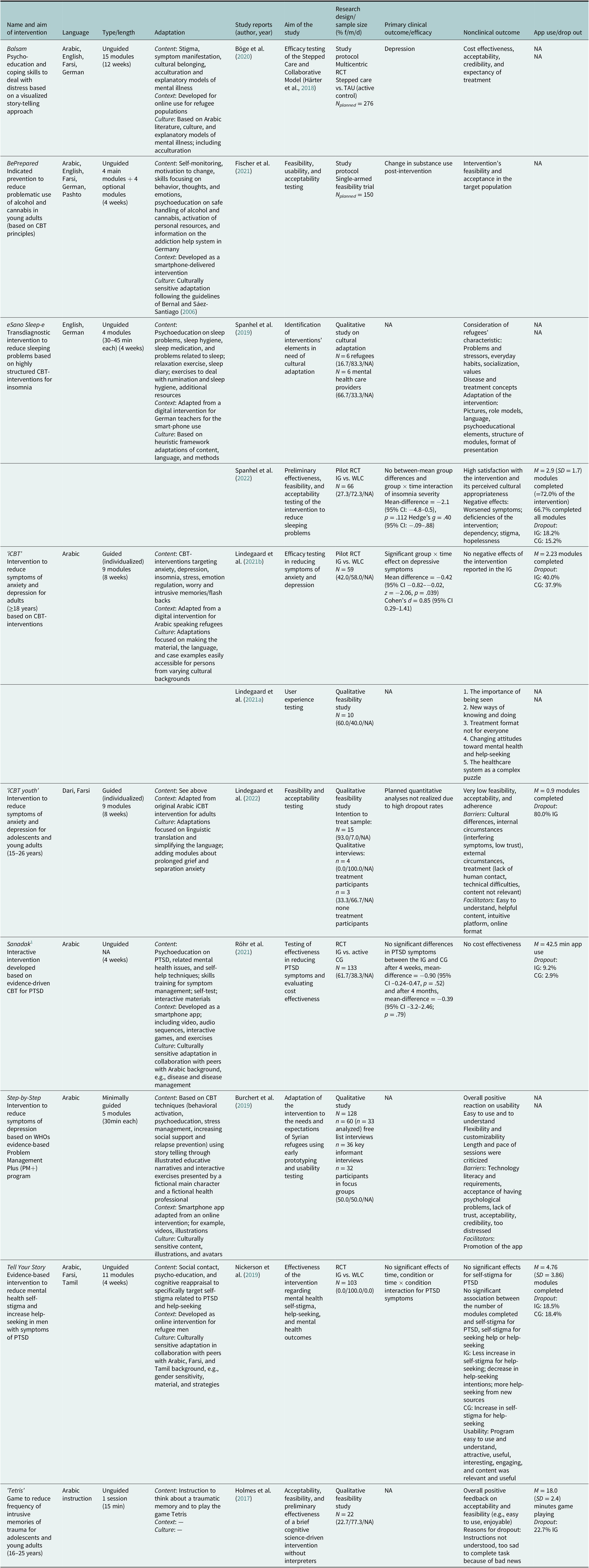

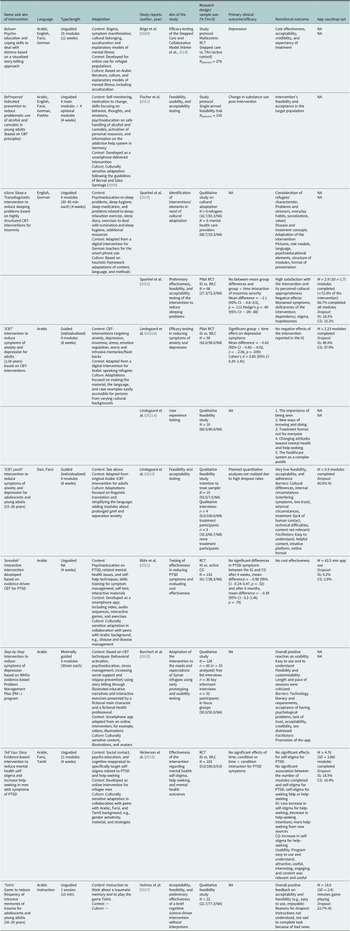

To answer the a priori defined research questions, relevant information was extracted for each intervention and study report (see Table 1). First, characteristics of each intervention were extracted: name and principal aim, language(s), length in modules and planned duration in weeks or months, type (guided vs. unguided), and adaptation (cultural and contextual). Next, respective study reports associated with each intervention were reported with the following information: first author and year of publication, aim of the study, research design used, primary clinical outcome (if available), reported nonclinical outcome, log data, and dropout rates. Data extraction was conducted individually by R.E. and L.N. following a standardized template and observed interrater agreement (P 0) was assessed (Cohen, Reference Cohen1960). Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Table 1. Smartphone-delivered mental health interventions for refugees and characteristics of associated publications

Note: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; CG, control group; IG, intervention group; M, mean; min, minutes; NA, not available; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; TAU, treatment as usual; WLC, wait list control group.

1 The systematic literature search identified a peer-reviewed study protocol of the planned RCT (Golchert et al., Reference Golchert, Roehr, Berg, Grochtdreis, Hoffmann, Jung, Nagl, Plexnies, Renner and König2019). Since the trial has been completed at the time of the systematic review, we decided to not extract information from the study protocol to avoid redundance.

Furthermore, a special emphasis was placed on data security in the context of smartphone-delivered interventions. Given the growing importance of data security (Gaebel et al., Reference Gaebel, Lukies, Kerst, Stricker, Zielasek, Diekmann, Trost, Gouzoulis-Mayfrank, Bonroy and Cullen2021), especially in refugee populations (Burchert et al., Reference Burchert, Alkneme, Bird, Carswell, Cuijpers, Hansen, Heim, Harper Shehadeh, Sijbrandij and Van’t Hof2019), the review aimed, from an exploratory perspective, to extract information on data security characteristics of smartphone-delivered mental health interventions and associated research studies, for example, where and for how long the data are stored, who has access to data, among others.

Results

The literature search yielded a total of 462 records. After removing duplicates, 433 titles and abstracts were screened. Eighteen full texts were considered for full-text analyses. Nine of these full texts describing eight different interventions met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. A further three full texts describing two novel interventions were identified through citation search and additionally included. No gray literature was eligible for inclusion. Three interventions without any published or unpublished reports were found to be eligible to answer the first research question. These interventions were identified by experts and were therefore included. No further information on their use, clinical and nonclinical outcomes, or drop-out rates can be provided. In total, nine smartphone-delivered mental health interventions for adult refugees and three for adolescent and young refugees were identified (see Figure 1). Interrater reliability for the literature search was κ = .68, indicating a substantial interrater agreement (Landis and Koch, Reference Landis and Koch1977).

Characteristics of included interventions

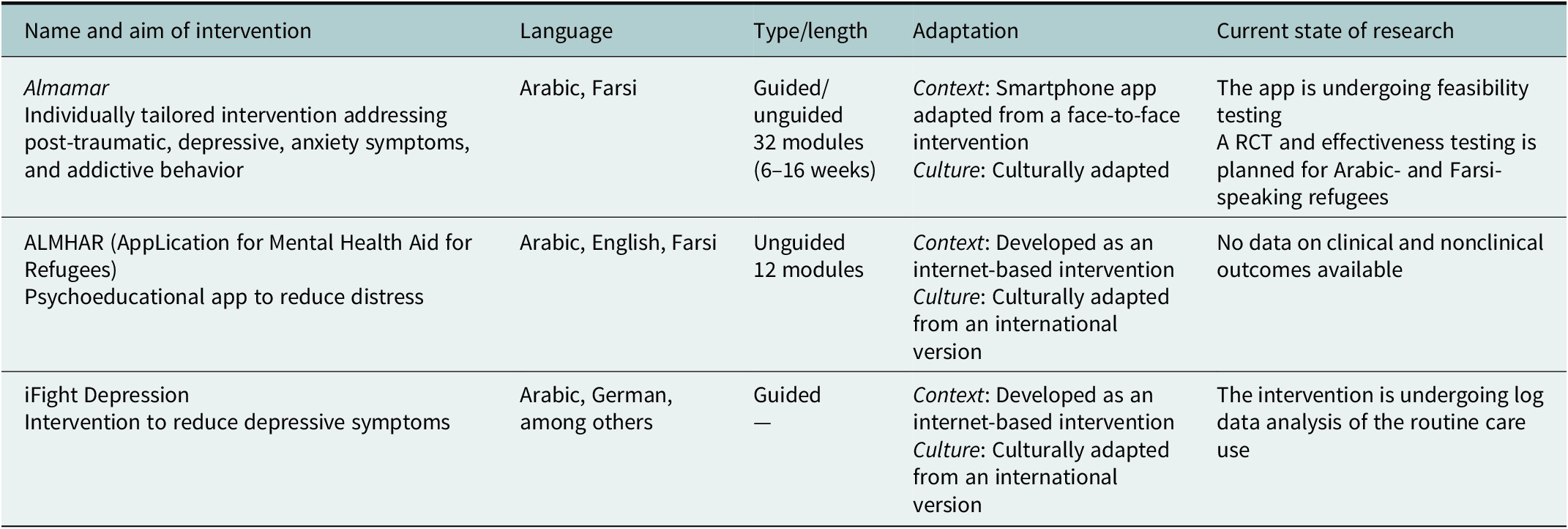

The identified interventions offer a wide variety of different treatment approaches (see Tables 1 and 2). A total of 5/12 interventions explicitly address depressive symptoms (Almamar, ‘iCBT’, ‘iCBT youth’, iFight Depression, and Step-by-Step), 3/12 of which additionally target anxiety symptoms (Almamar, ‘iCBT’, and ‘iCBT youth’). A total of 2/12 interventions explicitly target the treatment of PTSD (Almamar and Sanadak) and 2/12 seek to improve only specific symptoms such as sleep problems and concentration difficulties due to intrusive memories (eSano Sleep-e and ‘Tetris’). A total of 1/12 interventions try to improve mental health outcomes indirectly by addressing mental health care stigma and help-seeking attitudes (Tell Your Story). A total of 2/12 interventions focus on addictive behavior and substance abuse (Almamar and BePrepared). The treatment approaches also differ regarding psychotherapeutic guidance: 7/12 are unguided (ALMHAR, Balsam, BePrepared, eSano Sleep-e, Sanadak, Tell your Story, and ‘Tetris’), 3/12 are guided (‘iCBT’, ‘iCBT youth’, and iFight Depression), 1/12 are minimally guided (Step-by-Step), and 1/12 offer both a guided and an unguided version (Almamar). A total of 1/12 interventions are based on gamification linked to an instruction to remember traumatic events (‘Tetris’). In another intervention (1/12), a short self-test on post-traumatic symptom severity is implemented to allow for automated tailored feedback regarding progress at any time (Sanadak). To maximize usability, Sanadak also provides interactive materials such as animated video and audio as well as games and exercises. No other interventions used gamification. Regarding language, 8/12 interventions are offered in several languages (Almamar, ALMHAR, Balsam, BePrepared, eSano Sleep-e, ‘iCBT youth’, iFight Depression, and Tell Your Story), 10/12 in Arabic (Almamar, ALMHAR, Balsam, BePrepared, ‘iCBT’, iFight Depression, Sanadak, Step-by-Step, Tell Your Story, and ‘Tetris’), 6/12 in Farsi (Almamar, ALMHAR, Balsam, BePrepared, ‘iCBT youth’, and Tell Your Story), 1/12 in Dari (‘iCBT youth’), 1/12 in Pashto (BePrepared), and 1/12 in Tamil (Tell Your Story). Additionally, 1/12 interventions are offered in easily understandable English and German (eSano Sleep-e). Beyond language, all interventions but one (‘Tetris’) were culturally adapted to fit refugee populations or were explicitly developed for this purpose (11/12). Regarding context, 2/12 interventions were originally developed as smartphone-based interventions (BePrepared and Sanadak), 7/12 are internet-based or adapted from internet-based to smartphone-delivered interventions (ALMHAR, Balsam, eSano Sleep-e, ‘iCBT youth’, iFight Depression, Step-by-Step, and Tell Your Story), and 2/12 were based on face-to-face interventions (Almamar) or offline self-help material (‘iCBT’). Although all included interventions explicitly aim at improving mental health for refugee populations, none reported content or interventions on post-migration stressors.

Table 2. Interventions without published information.

Note: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Furthermore, the identified interventions were at different stages of their evaluation process. We included two RCTs (Nickerson et al., Reference Nickerson, Byrow, Pajak, McMahon, Bryant, Christensen and Liddell2019; Röhr et al., Reference Röhr, Jung, Pabst, Grochtdreis, Dams, Nagl, Renner, Hoffmann, König and Kersting2021) and two pilot RCTs (Lindegaard et al., Reference Lindegaard, Seaton, Halaj, Berg, Kashoush, Barchini, Ludvigsson, Sarkohi and Andersson2021b; Spanhel et al., Reference Spanhel, Hovestadt, Lehr, Spiegelhalder, Baumeister, Bengel and Sander2022), three feasibility studies (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Ghaderi, Eriksson, Lauri, Kukacka, Mamish, James and Visser2017; Lindegaard et al., Reference Lindegaard, Kashoush, Holm, Halaj, Berg and Andersson2021a, Reference Lindegaard, Wasteson, Demetry, Andersson, Richards and Shahnavaz2022), two qualitative studies on the development process (Burchert et al., Reference Burchert, Alkneme, Bird, Carswell, Cuijpers, Hansen, Heim, Harper Shehadeh, Sijbrandij and Van’t Hof2019), and the cultural adaptation of interventions (Spanhel et al., Reference Spanhel, Schweizer, Wirsching, Lehr, Baumeister, Bengel and Sander2019). Moreover, two peer-reviewed study protocols (Böge et al., Reference Böge, Karnouk, Hahn, Schneider, Habel, Banaschewski, Meyer-Lindenberg, Salize, Kamp-Becker and Padberg2020; Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Kölligan, Wieland and Klein2021) and three interventions without any published study reports were identified. Of the latter, two were identified by experts (Almamar and iFight Depression) and one by snowballing (ALMHAR).

Clinical and nonclinical outcomes of interventions

According to the respective stage of evaluation, different clinical and nonclinical outcomes were reported: Four of the identified study reports collected data on clinical outcomes and tested efficacy in the context of RCTs (Nickerson et al., Reference Nickerson, Byrow, Pajak, McMahon, Bryant, Christensen and Liddell2019; Röhr et al., Reference Röhr, Jung, Pabst, Grochtdreis, Dams, Nagl, Renner, Hoffmann, König and Kersting2021) or pilot RCTs (Lindegaard et al., Reference Lindegaard, Seaton, Halaj, Berg, Kashoush, Barchini, Ludvigsson, Sarkohi and Andersson2021b; Spanhel et al., Reference Spanhel, Hovestadt, Lehr, Spiegelhalder, Baumeister, Bengel and Sander2022). One of the included study protocols described a planned RCT on the efficacy of a stepped and collaborative care model including the smartphone-delivered intervention as one of several low-threshold stand-alone interventions (Böge et al., Reference Böge, Karnouk, Hahn, Schneider, Habel, Banaschewski, Meyer-Lindenberg, Salize, Kamp-Becker and Padberg2020). The other study protocol described a planned one-armed feasibility and acceptability trial of an app targeting problematic use of alcohol and cannabis (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Kölligan, Wieland and Klein2021). Although one feasibility study also collected data on clinical outcomes, no pre–post comparisons or other inferential statistics were reported (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Ghaderi, Eriksson, Lauri, Kukacka, Mamish, James and Visser2017).

One study reported a significant difference between the intervention and control group in the pre–post comparison (Lindegaard et al., Reference Lindegaard, Seaton, Halaj, Berg, Kashoush, Barchini, Ludvigsson, Sarkohi and Andersson2021b). Three studies did not report significant results regarding their primary outcomes (Nickerson et al., Reference Nickerson, Byrow, Pajak, McMahon, Bryant, Christensen and Liddell2019; Röhr et al., Reference Röhr, Jung, Pabst, Grochtdreis, Dams, Nagl, Renner, Hoffmann, König and Kersting2021; Spanhel et al., Reference Spanhel, Hovestadt, Lehr, Spiegelhalder, Baumeister, Bengel and Sander2022). Additionally, most of the studies reported several secondary clinical outcomes, with only few significant results. At the same time, the control conditions in the studies differed greatly: Three studies applied waitlist control conditions (Nickerson et al., Reference Nickerson, Byrow, Pajak, McMahon, Bryant, Christensen and Liddell2019; Lindegaard et al., Reference Lindegaard, Seaton, Halaj, Berg, Kashoush, Barchini, Ludvigsson, Sarkohi and Andersson2021b; Spanhel et al., Reference Spanhel, Hovestadt, Lehr, Spiegelhalder, Baumeister, Bengel and Sander2022), one used an active control condition (Röhr et al., Reference Röhr, Jung, Pabst, Grochtdreis, Dams, Nagl, Renner, Hoffmann, König and Kersting2021), and the study protocol reported a planned treatment-as-usual control condition (Böge et al., Reference Böge, Karnouk, Hahn, Schneider, Habel, Banaschewski, Meyer-Lindenberg, Salize, Kamp-Becker and Padberg2020).

Dropout rates also varied widely between studies. While most reported low dropout rates (2.9–18.5%; Nickerson et al., Reference Nickerson, Byrow, Pajak, McMahon, Bryant, Christensen and Liddell2019; Röhr et al., Reference Röhr, Jung, Pabst, Grochtdreis, Dams, Nagl, Renner, Hoffmann, König and Kersting2021; Spanhel et al., Reference Spanhel, Hovestadt, Lehr, Spiegelhalder, Baumeister, Bengel and Sander2022), some reported high rates (37.9–80%; Lindegaard et al., Reference Lindegaard, Seaton, Halaj, Berg, Kashoush, Barchini, Ludvigsson, Sarkohi and Andersson2021b, Reference Lindegaard, Wasteson, Demetry, Andersson, Richards and Shahnavaz2022). Lastly, few participants worked on all modules offered throughout the interventions or used the interventions as recommended. On average, participants completed 37.51% of the respective intervention (10–72%; Lindegaard et al., Reference Lindegaard, Wasteson, Demetry, Andersson, Richards and Shahnavaz2022; Spanhel et al., Reference Spanhel, Hovestadt, Lehr, Spiegelhalder, Baumeister, Bengel and Sander2022). Overall, most study reports lack clear information about the recommended dose of intervention.

The included studies reported a broad variety of nonclinical outcomes. In particular, the qualitative studies identified relevant themes regarding feasibility, usability, treatment barriers, and content. Six study reports included statements about the acceptance of the respective intervention (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Ghaderi, Eriksson, Lauri, Kukacka, Mamish, James and Visser2017; Burchert et al., Reference Burchert, Alkneme, Bird, Carswell, Cuijpers, Hansen, Heim, Harper Shehadeh, Sijbrandij and Van’t Hof2019; Nickerson et al., Reference Nickerson, Byrow, Pajak, McMahon, Bryant, Christensen and Liddell2019; Lindegaard et al., Reference Lindegaard, Seaton, Halaj, Berg, Kashoush, Barchini, Ludvigsson, Sarkohi and Andersson2021b, Reference Lindegaard, Wasteson, Demetry, Andersson, Richards and Shahnavaz2022; Spanhel et al., Reference Spanhel, Hovestadt, Lehr, Spiegelhalder, Baumeister, Bengel and Sander2022). With the exception of one study (Lindegaard et al., Reference Lindegaard, Wasteson, Demetry, Andersson, Richards and Shahnavaz2022), the findings indicated a general acceptance of the interventions by refugees. Nevertheless, some aspects were identified as conflicting. For instance, some participants mentioned anonymous participation as a major benefit of smartphone-delivered interventions, while at the same time, participants wished for more personal contact like regular telephone calls or face-to-face meetings with their therapist (Burchert et al., Reference Burchert, Alkneme, Bird, Carswell, Cuijpers, Hansen, Heim, Harper Shehadeh, Sijbrandij and Van’t Hof2019). Identified treatment barriers included lack of technological literacy and respective difficulties, cultural differences, lack of trust in data security, and written-based treatment. One study summarized that participants dropped out because they did not understand the instructions or were too sad to complete the task (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Ghaderi, Eriksson, Lauri, Kukacka, Mamish, James and Visser2017).

Data security

Although lack of data security and a consequent lack of trust in smartphone-delivered interventions was identified as an important barrier, only some of the identified reports addressed this topic. Therefore, we excluded this information from our data extraction table. Five study reports provided information on the topic of data security: one RCT (Röhr et al., Reference Röhr, Jung, Pabst, Grochtdreis, Dams, Nagl, Renner, Hoffmann, König and Kersting2021), one pilot RCT (Lindegaard et al., Reference Lindegaard, Seaton, Halaj, Berg, Kashoush, Barchini, Ludvigsson, Sarkohi and Andersson2021b), one qualitative usability study (Burchert et al., Reference Burchert, Alkneme, Bird, Carswell, Cuijpers, Hansen, Heim, Harper Shehadeh, Sijbrandij and Van’t Hof2019), and the study protocols (Böge et al., Reference Böge, Karnouk, Hahn, Schneider, Habel, Banaschewski, Meyer-Lindenberg, Salize, Kamp-Becker and Padberg2020; Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Kölligan, Wieland and Klein2021). The qualitative study identified data security as important for the target group. The RCT fulfilled high standards regarding European data security policies, while the study protocols described an overall elaborated data security concept involving specialist lawyers. Finally, the pilot RCT referred to an external webpage called Iterapi, which guarantees data security (Vlaescu et al., Reference Vlaescu, Alasjö, Miloff, Carlbring and Andersson2016). All other reports did not mention data security measures at all. Interrater agreement for data extraction ranged from 75 to 100% (see Online Supplement 4 of the Supplementary Material). Lower agreement might have resulted from a less detailed description of some aspects in single study reports.

Quality appraisal

The quality of studies was rated using the instruments described in the ‘Methods’ section. These enable the rating of the availability of quality criteria regarding title and abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and other information like funding or competing interests. Due to small numbers of each study type, RCT and pilot RCT quality assessments were summarized based on the similarity of ratings. Most of the studies fulfilled the proposed quality criteria of the CONSORT checklists (Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Altman and Moher2011; Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Chan, Campbell, Bond, Hopewell, Thabane and Lancaster2016). However, single aspects were not addressed with sufficient detail to allow future researchers to replicate the study design, for example, recruitment strategies were reported only superficially. Moreover, sample sizes were overall small, ranging from N = 59–133, which does not allow for a generalization of findings and conclusions. Additionally, the samples were only partly representative. In most samples, male refugees aged 28–41 years were overrepresented, so that these results cannot be generalized to female or gender-diverse refugees or other cultural refugee groups.

Quality assessment of qualitative studies revealed deficits in the method section of all included studies. Some quality criteria were not reported, for instance, researchers’ characteristics and their influence on the findings. Furthermore, barely any explicit effort to ensure trustworthiness of the qualitative data and the derived insights was reported (cf. SRQR; O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed and Cook2014). Overall, the quality of study reports and protocols was satisfactory. A detailed description of the quality of each study is provided in the Online Supplement 5 of the Supplementary Material.

Discussion

The current systematic review aimed to identify and describe smartphone-delivered mental health interventions for refugee populations, thus targeting an existing knowledge gap. The review addressed the different characteristics of these interventions for refugee populations and summarized their effectiveness regarding clinical outcomes and important insights into nonclinical outcomes. The review was faced with considerable heterogeneity between interventions and study designs. It was not possible to reduce heterogeneity since the current evidence base is still sparse. Nevertheless, we were able to identify very recent literature, with all studies except one being published between 2019 and 2022. The systematic review clearly shows that various interventions have recently been developed. Currently, no smartphone-delivered intervention seems to meet the needs of the respective population comprehensively. Moreover, the specific needs of these populations might not yet be fully understood. This is reflected in ambiguous findings in qualitative interviews (e.g., regarding the advantages and disadvantages of personal contact during treatment), low utilization of apps, high dropout rates, and a lack of reliable evidence on effectiveness and efficacy.

The efficacy of smartphone-delivered interventions has been shown to be less convincing than more complex browser-based interventions, but the evidence is primarily based on Western populations (Weisel et al., Reference Weisel, Fuhrmann, Berking, Baumeister, Cuijpers and Ebert2019). The results from (pilot) RCTs included in this review reveal limited efficacy for refugee populations (Nickerson et al., Reference Nickerson, Byrow, Pajak, McMahon, Bryant, Christensen and Liddell2019; Röhr et al., Reference Röhr, Jung, Pabst, Grochtdreis, Dams, Nagl, Renner, Hoffmann, König and Kersting2021; Lindegaard et al., Reference Lindegaard, Seaton, Halaj, Berg, Kashoush, Barchini, Ludvigsson, Sarkohi and Andersson2021b; Spanhel et al., Reference Spanhel, Hovestadt, Lehr, Spiegelhalder, Baumeister, Bengel and Sander2022), potentially for different reasons (e.g., utilization and adherence to interventions were often reported to be low). Contextual and/or cultural adaptations might be necessary. Furthermore, first evidence from non-refugee samples hint to slightly better efficacy for guided versus unguided digital interventions with at least minimal personal contact (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Noma, Karyotaki, Cipriani and Furukawa2019). Although we could not find this effect clearly in the studies included, different scalable interventions for refugees from the World Health Organization (WHO) like Step-by-Step and Problem Management Plus are currently investigated in RCTs thus providing results on this question in the future (cf., Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Tip and Cavanagh2021). Recently published data on guided versions are promising (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Heim, Abi Ramia, Burchert, Carswell, Cornelisz, Knaevelsrud, Noun, van Klaveren and van’t Hof2022).

In addition, the systematic review did not identify any study or intervention explicitly addressing post-migration stressors. As research has indicated associations between post-migration stressors and mental health outcomes (Jannesari et al., Reference Jannesari, Hatch, Prina and Oram2020), and suggests that mental health symptoms can be effectively reduced by changing post-migration stressors (Schick et al., Reference Schick, Morina, Mistridis, Schnyder, Bryant and Nickerson2018), these should be addressed in future treatment approaches for refugee populations (cf., Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Tip and Cavanagh2021).

Trustworthiness and data security were only addressed in qualitative studies (Burchert et al., Reference Burchert, Alkneme, Bird, Carswell, Cuijpers, Hansen, Heim, Harper Shehadeh, Sijbrandij and Van’t Hof2019) and were not mentioned in most of the study reports. Moreover, the review did not identify any data points reporting or addressing non-binary gender (with the exception of one intervention targeting only male refugees; Nickerson et al., Reference Nickerson, Byrow, Pajak, McMahon, Bryant, Christensen and Liddell2019). Furthermore, while the development and adaptation of smartphone-delivered interventions are highly resource-consuming, most of the interventions were no longer available after the respective trial. The majority of data points did not report any information on availability and possible use of the respective interventions.

One strategy to address some of these deficits might be to avoid using smartphone-delivered interventions as stand-alone interventions. Several possibilities exist to implement smartphone-delivered interventions into existing mental health care systems or in contexts where no reliable mental health care system exists. For instance, smartphone-delivered interventions could be implemented as part of a stepped-care approach where they represent a low threshold intervention in a hierarchy of differently intensive interventions. Such an approach is followed by the Sanadak intervention, where results have to be awaited for future implications (Böge et al., Reference Böge, Karnouk, Hahn, Schneider, Habel, Banaschewski, Meyer-Lindenberg, Salize, Kamp-Becker and Padberg2020, Reference Böge, Karnouk, Hoell, Tschorn, Kamp-Becker, Padberg, Übleis, Hasan, Falkai, Salize, Meyer-Lindenberg, Banaschewski, Schneider, Habel, Plener, Hahn, Wiechers, Strupf, Jobst, Millenet, Hoehne, Sukale, Dinauer, Schuster, Mehran, Kaiser, Bröcheler, Lieb, Heinz, Rapp and Bajbouj2022). Other smartphone-delivered interventions are used as blended-care interventions to complement group interventions (an exclusion criterion in this review; e.g., NESTT and The Happy Helping Hand) or in inpatient mental health care (e.g., Almamar), revealing promising initial findings (e.g., Raknes et al., Reference Raknes, Dyregrov, Pallesen, Hoffart, Stormyren and Haugland2017; Mazzulla et al., Reference Mazzulla, Fondacaro, Weldon, Dibble and Price2021). The above-mentioned scalable interventions of the WHO Step-by-Step and Problem Management Plus might offer further possibilities to combine smartphone-delivered interventions with already existing effective and scalable group interventions (e.g., Tol et al., Reference Tol, Leku, Lakin, Carswell, Augustinavicius, Adaku, Au, Brown, Bryant, Garcia-Moreno, Musci, Ventevogel, White and van Ommeren2020; Acarturk et al., Reference Acarturk, Uygun, Ilkkursun, Yurtbakan, Kurt, Adam-Troian, Senay, Bryant, Cuijpers, Kiselev, McDaid, Morina, Nisanci, Park, Sijbrandij, Ventevogel and Fuhr2022).

Most of the studies reported difficulties in recruiting the target population and high rates of dropout. Greater knowledge is required on how to attract refugees in need and how to engage them with treatment to improve their mental health and quality of life. An exception was the transdiagnostic sleep intervention, which included more participants in the pilot RCT than intended due to high demand (Spanhel et al., Reference Spanhel, Hovestadt, Lehr, Spiegelhalder, Baumeister, Bengel and Sander2022). This might hint at the need for different approaches and a greater focus on individual symptoms rather than on general mental health.

In general, when offering smartphone-delivered interventions, it is important to consider that not all refugees in all contexts have access and conditions to use respective interventions. Beyond clinical trials, practical barriers in more naturalistic settings need to be considered when implementing these interventions. For instance, their use should be possible without a SIM card since access to SIM cards is legally limited in many countries (e.g., requirement of a valid and acknowledged identification document; GSMA, 2017). Comparably, shared mobile phones, limited access to the internet, and crowded living conditions lacking privacy need to be considered on the long term (cf., Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Tip and Cavanagh2021).

Limitations

The findings of the current systematic review need to be considered in the light of several limitations. First, due to the broad aims of the review, the included study reports and interventions vary widely regarding several characteristics, impeding a concise summary and comparison of results. This is partly also reflected in the interrater reliability. Second, although search terms and inclusion criteria were carefully selected by several experienced researchers in the field of study, we cannot completely rule out having missed single interventions or research reports. Furthermore, since the field of study is constantly growing, new evidence is published frequently. For instance, new evidence on the intervention Step-by-Step and Sanadak has recently been published and could not be included in the systematic review (Böge et al., Reference Böge, Karnouk, Hoell, Tschorn, Kamp-Becker, Padberg, Übleis, Hasan, Falkai, Salize, Meyer-Lindenberg, Banaschewski, Schneider, Habel, Plener, Hahn, Wiechers, Strupf, Jobst, Millenet, Hoehne, Sukale, Dinauer, Schuster, Mehran, Kaiser, Bröcheler, Lieb, Heinz, Rapp and Bajbouj2022; Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Heim, Abi Ramia, Burchert, Carswell, Cornelisz, Knaevelsrud, Noun, van Klaveren and van’t Hof2022). Third, based on the current state of research, we were unable to look more closely at subgroups of refugees, for example, according to language, home country, or resettlement country. This might be an important topic for future research. Finally, the current systematic review does not allow for far-reaching conclusions and cannot inform future health care decisions for refugee populations, as sufficient evidence is not yet available.

Conclusions

This systematic review provided an overview of existing smartphone-delivered mental health interventions for refugee populations. All of the identified publications stress the importance of adequate mental health care for this highly vulnerable group. However, much more research is required on different aspects of interventions, for example, how to successfully access the target population and how to improve their treatment adherence. The benefits of smartphone-delivered interventions for this target population remain compelling, and to achieve high acceptance and utilization among refugees, it is necessary to carefully develop culturally and contextually adapted interventions with high attractiveness and trustworthiness. Moreover, to address the heterogeneity of the target population, future interventions and treatment approaches should also be as diverse as possible in order to fit the needs of more homogeneous subgroups.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.61.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.61.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the systematic review is available within the published review and its online supplements.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Julia Lengen for her assistance with the preparation of the study report and Sarah Mannion for the language editing of the manuscript.

Author contributions

All authors were equally involved in the conceptualization of the systematic review. Project administration was the responsibility of R.E. and L.N. Data curation and data analyses consisting of database search, identifying gray and unpublished literature, inclusion and exclusion of data points, data extraction, and calculating interrater agreement were equally conducted by R.E. and L.N. The whole process was methodologically supervised by H.N. M.B. supervised content-related aspects and rated data points which resulted in disagreement regarding inclusion or exclusion and discussed them with R.E. and L.N. to reach a final decision. All findings were validated by M.B., C.K., and H.N. The original draft of the manuscript was written by R.E.- and L.N. It was reviewed and edited by M.B., C.K., and H.N. R.E. and L.N. shared first authorship.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest

M.B. and R.E. also work at Zentrum ÜBERLEBEN gGmbH which developed and provides the intervention ALMHAR. C.K. is principal investigator and L.N. is coordinator of the research project I-REACH which develops and validates the intervention Almamar. C.K. is also principal investigator of the STRENGTHS project which develops and validates the Step-by-Step intervention. H.N. declares no conflict of interest.

Ethics standards

All authors declare to adhere to the publishing ethics of Global Mental Health.

Comments

Dear Editor,

Hereby we submit the invited systematic review titled "Smartphone-delivered mental health care interventions for refugees: A systematic review". The current systematic review gives an overview of the existing stand-alone smartphone-delivered interventions for mental health problems in refugee populations. We identified nine mental health smartphone-delivered interventions for adult and three for adolescent and young refugees. The review enables the audience to identify treatments in different languages, targeting different mental problems, and offering varying amounts of support. This helps persons affected, persons working with refugee populations, and stake holders to identify the most fitting interventions for specific persons or populations. In the course of the summarized trials, about 400 refugees were provided with smartphone-delivered mental health care. The results show that the different interventions were able to improve single aspects of mental health and well-being. Still, we identified room for improvement in the efficacy and effectiveness of smartphone-delivered interventions, the involvement of post-migration stressors in the treatment, and data safety. This knowledge helps scientists and stakeholders to decide which steps should be taken next to fully exploit the potential of smartphone-delivered mental health interventions for refugees. For instance, we need more knowledge about effective treatment elements, facilitating characteristics to improve their use, and barriers which hamper the wide use in refugee populations.

In the submission process, we had to face several difficulties:

(1) In step 1, we were not able to select a specific issue for the invited systematic review.

(2) In step 4, we were not able to designate Rayan El-Haj-Mohamad and Laura Nohr as shared first authors.

(3) In general, Christine Knaevelsrud was invited to submit the systematic review. Therefore, she is logged in to the submission system. But, Laura Nohr in her role as corresponding author was submitting the manuscript. Therefore, she entered her ORCID wrongly to the name of Christine Knaevelsrud. Now, the name of Christine Knaevelsrud is linked to Laura Nohr's ORCID (= 0000-0002-3798-0909).

(4) Also we would like to add the ORCIDs of the co-authors as well. Is there any possibility to do so?

We appreciate the opportunity of submitting the systematic review to Global Mental Health and thank you for the collaboration.

Sincerely,

Rayan El-Haj-Mohamad & Laura Nohr