Introduction

Music festivals in general, and Electronic Dance Music Events (EDMEs) in particular, are increasingly common and part of a 4.5 billion US dollar industry annually (Figure 1).Reference Turris and Lund 1 There currently is no standardized definition for what constitutes a music festival.Reference Carmichael 2 Music at EDMEs may have one or more of the following characteristics: (a) often, but not always, played by a DJ rather than being performed by musicians with instruments; (b) the music primarily is rhythmic (ie, repetitive) rather than melodic in nature;Reference Getz 3 (c) vigorous dancing is common;Reference Krul 4 , 5 and (d) recreational drug use often is part of the culture of the event.Reference Reider 6 , Reference Grange, Corbett and Downs 7 Mass-gathering events with these characteristics may be referred to as “EDMEs,” “raves,” “dance parties,” “music festivals,” and/or “house parties.”Reference Getz 3

Figure 1 Music Festivals as Community Events. Photo Credit: Dr. Adam Lund. Note: No fatalities are attributed to the depicted event. The image proved an illustration of the crowd and the context of a music festival.

Compared with other types of events that involve young people gathering in large numbers, music festivals often are portrayed in the media to be higher risk and, in fact, may represent a public health issue.Reference Castro and Foy 8 , Reference Madert 9 Documented non-traumatic risks of music festivals include: alcohol overuse,Reference Weir 10 drug use,Reference Johnson, Voas, Miller and Holder 11 - Reference Johnson, Voas and Miller 13 and drug overdoses related to the use of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine (MDMA) and related compounds, gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB),Reference Van Havere, Vanderpalasschen, Lammertyn, Broekaert and Bellis 14 as well as other drugs such as LSD, mushrooms, ketamine, and stimulants.Reference Box, Prescott and Freestone 15 Trauma-related deaths from driving accidentsReference Johnson, Voas, Miller and Holder 11 and/or mass-casualty incidents (MCIs) also have been reported.Reference Britt and McCance-Katz 16

Fifteen years ago, Weir argued that EDMEs were a significant source of mortality and morbidity and worthy of further attention by researchers and clinicians.Reference Madert 9 Over the last 15 years, mainstream English media sources have reported deaths locally, nationally, and internationally in the context of music festival attendance.Reference Soomaroo and Murray 17 - 50 Health care professionals involved in the provision of on-site care at large music festivals experience first-hand the range of clinical presentations at these events, and researchers are just beginning to systematically document the illness/injury burden and case-mix associated with this category of event.Reference Weir 10 - Reference Van Havere, Vanderpalasschen, Lammertyn, Broekaert and Bellis 14 , Reference Stein 51 - Reference Boles 53

In this manuscript, the authors present an analysis of fatalities associated with music festivals, drawn from both the academic and gray literature. In addition, the authors propose a systematic approach to using retrospective, iterative Internet searches and prospective Google (Google Inc.; Mountain View, California USA) Alerts in popular media as a source of data on mortality.

Research Questions

The questions used in this research were as follows:

-

1. How many and what types of fatalities were reported in the setting of music festivals from 1999 through 2014?

-

a. In the academic literature; and

-

b. In the popular media.

-

-

2. How might music festival-related fatalities be classified and categorized, inductively, for researchers, policy makers, medical directors, and event planners?

-

3. What are the sources and limitations of the evidence available for analysis?

Methods

Case Finding

A search strategy was created in consultation with a reference librarian (PB) and applied to the academic literature (Table 1). The authors also conducted a search of English language articles published in the mainstream media from 1999 through 2014, using academic and non-academic search terms. Retrospective case finding identified articles referencing death at eligible events in the last 15 years. Prospective Internet alerts were set up using Google Alerts through 2014. Search depth was a minimum of 10 pages deep.

Table 1 Search Strategies for Primary and Secondary Sources

Academic and media reports were used to locate new cases (eg, researchers [and reporters] sometimes cited previous, similar deaths). Names of victims (when publicly available) were recorded to prevent double counting. After a case was identified and recorded, a retrospective Internet search for the event name and victim name was conducted, and a Google Alert was created to track prospective reports on the incident (eg, if a death was reported but no cause of death identified, information from later media reports, such as a delayed coroner’s report, could be added to the spreadsheet). Additional information gleaned from these reports allowed the search strategy and database to grow and become more specific over time.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Reports were selected for review if: (1) they were published in the English language; (2) the death or deaths occurred from 1999 through 2014; (3) the report described a fatality related to attendance at a music festival; and (4) they included demographic information, such as the name and location (city/town and country) of the music festival, the month/year of the fatality, age of the deceased, and sex and/or name of the deceased.

Reports were excluded from review if the fatality: (1) was not clearly related to attendance at a music festival; (2) occurred in the setting of a permanent night club or dance venue; or (3) was only reported in private blogs or social media sites

Data Extraction and Analysis

An Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft [Microsoft Corp.; Redmond, Washington USA] for Mac [Apple Inc.; Cupertino, California USA] 2011) was created for data extraction (Table 2). Data were reviewed and subsequently entered by research team members (ST, KL, AL). Classification and categories for fatalities were identified inductively as the data were collected and analyzed. Fatality data then were summarized.

Table 2 Excel Data Extraction Fields

Categorizing Cases

Cases were categorized according to proximal cause of death. For example, if an individual imbibed a recreational drug, became paranoid, and then ran into oncoming traffic, the case was categorized as a death resulting from trauma. Due to a general lack of detailed reporting on cause of death, overdose (ie, taking too much of a recreational drug or drugs) and poisoning (ie, death related to contaminated recreational drugs) were classified in the same category. If a death occurred off-site, but clearly was associated with attending a music festival, the case was included (eg, attendee ejected from event and then running into oncoming traffic).

Ethics

Ethics approval was applied for and waived by the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) Research Ethics Board as data were collected from publicly available sources.

Results

Gray Literature

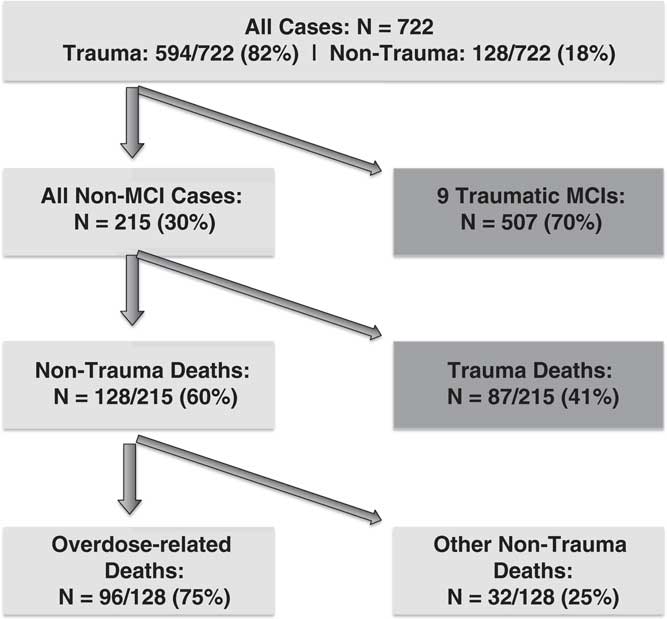

In the context of music festivals, there have been 722 deaths documented in popular media in the last 15 years, up to and including December of 2014 (Figure 2). Excluding the MCIs, for which the ages of the deceased are not recorded, ages of the deceased ranged from 14-82 years (mean=23.8 years).

Figure 2 Media Reports of Music Festival Fatalities.

Attributed causes initially were divided into trauma- (594/722; 82%) and non-trauma-related (128/722; 18%) categories. Trauma-related deaths included nine MCIs (ie, 10 or more fatalities; n=507). The majority of MCI deaths were the result of stampedes/trampling (eg, Emeneya Music Festival in 2014, Democratic Republic of Congo [n=21]; Love Parade in 2010, Germany [n=21]; Mawaxine Festival in 2009, Morocco [n=11]; Cambodian Music Festival in 2008 [n=347]; South Korea in 2005 [n=11]; and Sports Palace Festival in 1999, Belarus [n=54]). One structural failure resulted in 16 fatalities (K-Pop Festival in South Korea, 2014). Two music festivals were the targets of acts of terror, including two bombings causing trauma-related deaths (Wings Festival in 2003, Moscow [n=16]; and Bangladesh New Year’s Festival in 2001 [n=10]). Removing all nine MCIs from the analysis reduced the total number of all-cause fatalities substantially (n=215).

Non-traumatic deaths included overdoses (n=96/722; 13%), environmental causes (n=8/722; 1%), natural causes (n=10/722; 1%), and unknown/not reported (n=14/722; 2%). The majority of non-trauma-related deaths were related to overdose (96/128; 75%; Table 3).

Table 3 Total Deaths at Music Festivals Per Media Reports (1999-2014)

A total of 156 separate incidents resulting in deaths during music festivals were identified. Media reports of fatalities increased in frequency over the study period. For example, just over one-half of the incidents (n=84; 55%) occurred between 2012-2014 and only six incidents (less than four percent) were documented for the first three years of the study period (1999-2001).

Academic Literature

The majority of deaths documented in the academic literature were captured in the gray literature (n=368). Conversely, only 51% (368/722) of the total number of music festival deaths identified were documented in the academic literature. The academic literature documented both trauma-related deaths (n=368) and overdose-related deaths (n=12) at music festivals.

Discussion

Epidemiology of Fatalities at Music Festivals

Both academic and media reports confirm that the majority of deaths that occurred in the setting of music festivals were due to traumatic causes such as trampling, structural failures, and acts of terror. The majority of deaths occurred in the context of MCIs.

Recommendation #1: Plan for Traumatic Injuries and Mass-Casualty Incidents

Given that 82% of deaths (n=594) at music festivals are due to trauma, many of which were MCIs, event pre-planning should include:

-

∙ disaster and emergency risk assessment and management planning;

-

∙ on-site ability for first response to trauma and orientation to responding to a MCI;

-

∙ pre-engagement with local emergency response agencies with responsibility to attend in the event of a disaster or MCI; and

-

∙ crowd management planning and crowd control procedures.

Recommendation #2: Fund Research that may Decrease Alcohol and/or Drug-Related Harms in the Context of Mass Gatherings

Non-traumatic fatalities related to music festival attendance were difficult to locate in the academic literature. The toxicology literature, for example, identified deaths related to overdose with recreational drugs in general, but typically provided no information about the setting in which an overdose or poisoning took place.Reference Dutch and Austin 54 , Reference Gill, Hayes and de Souza 55 Twelve overdose fatalities specifically related to music festival attendance were found in the academic literature (1996-2014)Reference Milroy 56 - Reference Walterscheid, Phillips, Lopez, Gonsoulin, Chen and Sanchez 62 compared to 96 similar deaths in media reports. This finding confirms that there is currently a gap in the academic literature with regard to reporting of deaths associated with music festival attendance.

Given that 75% of non-traumatic fatalities at music festivals are associated with alcohol and/or drug-related factors, research is needed to understand the incidence, role, and risks of alcohol and drug-related harms and deaths at music festivals. Better characterization of attendee behavior, motivation, and culture may permit improved strategies for health promotion, injury/illness prevention, and harm reduction.

Mortality and Morbidity

Media sources seem much more likely to report on mortality than morbidity. Reports reviewed for this study rarely provided information regarding the number of patients seen and treated on site, and seldom provided information about the number of patients transferred by ambulance to an emergency department (ED). Further, increased workload at local EDs was not typically the subject of media reports. One exception was the media report for the Boonstock Festival, held in British Columbia in 2014, during which one death occurred and 80 people were transferred to hospital.Reference Ridpath, Driver and Nolan 63

In contrast, in the academic literature, three music festival case series and several case reports have been published, detailing the morbidity associated with such events. 47 , Reference Chan 64 - Reference Molloy, Brady and Maleady 68 Existing academic reports support the hypothesis that music festivals have not only a mortality burden, but also a morbidity burden, which may be minimized by public health initiatives such as harm reduction strategies and by the integration of a medical team on site.

Recommendation #3: Require Standardized, Centralized Reporting of Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities by All Health Stakeholders as Part of a Planned After-Action Debrief

Given the dearth of information in media reports about the number and impact of illnesses/injuries presenting to on-site medical teams and to local EDs and health infrastructure, make such deaths reportable to public health authorities. Such information might support evidence-based permitting, by-laws, licensing, and policies to support safe, enjoyable events. Quantifying the patient numbers and acuity will permit improved planning for on-site first aid and higher level of care emergency response, as well as planning for ambulance transports for off-site care.

Limitations

Gray Literature

Hsieh, Ngai, Burkie, and Hsu argued that non-traditional sources must be used in developing an understanding of the epidemiology related to illness and injury at mass gatherings.Reference Stagelund, Jans and Nielsen 69 Grey literature is defined as work not published via traditional academic sources, and as such, not always widely disseminated or indexed.Reference Hsieh, Ngai and Burkle 70 , 71 Increasingly, grey literature is becoming part of the mainstream flow of knowledge. 72 - 75 Although use of grey literature may focus attention on a clinical issue well before it has been described clearly in the scientific literature, thereby shortening the average 17 year gap for translation into practice changes, 76 there are both strengths and weaknesses to this approach.

A lack of indexingReference Hsieh, Ngai and Burkle 70 , Reference Morris, Wooding and Grant 77 and no systematic retrieval system means that it is possible that many additional reports exist that were not located in this search, particularly going back in time. As well, the permanence of news articles on Internet-hosted sites is uncertain, so older cases may be lost to contemporary searches. The fact that the authors found relatively few online media reports in the early years of the study may be due to the fact that media links “go dark” after a certain period of time.

Academic Literature

The limitations of case finding in the academic literature were sobering. Because deaths from overdoses of recreational drugs are not uncommon, researchers seldom publish case studies on these deaths. Documentation of these deaths do not add to the scientific knowledge about reducing mortality and morbidity and therefore are unlikely to be accepted for publication. Comparing the number substance-use-related deaths reported in the gray literature with the number of deaths reported in the academic literature, the number of deaths related to attendance at music festivals is likely grossly under-reported in the academic literature.

Interpreting the Data

Because data are not systematically collected and publicly reported post-event, the actual number of deaths related to music festival attendance is difficult to determine, but the number of incidents causing fatalities appears to be rising. This may be due to several factors. The number of music festivals being produced is increasing. It may be that the increasing number of deaths reported in this current study is an artifact of the absolute increase in the number of events rather than being attributable to events becoming “more unsafe.” As well, media reports may have a short life cycleReference Hsieh, Ngai and Burkle 70 and are influenced by what is considered newsworthy at a given point in time (ie, more drug-related deaths at music festivals may lead to more attention being focused on music festivals and so more cases brought to the attention of the public).

Recommendation #4: Develop a Prospective, Centralized Database to Track Music Festival Mortality and Morbidity and to Collect Event-Specific Data

As such, prospective monitoring likely will yield a more complete picture of the mortality reported in the media.

Conclusion

The results of this study begin to document the health impact of music festivals, confirming that there is a mortality burden associated with music festival attendance. The methodology presented here represents a necessary first step to quantifying the risks involved. Ongoing surveillance of music festival-related deaths will support the development of a data set upon which to test hypotheses and measure the effects of hazard and risk assessment, emergency pre-planning, health promotion, injury/illness prevention, and harm reduction efforts, as well as on-site emergency response interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Ms. Kerrie Lewis for her superb work and meticulous organizational skills on this project; Dr. Brendan Munn for his ongoing collaborations with regard to music festival safety and emergency response; Ms. Pat Boileau, our reference librarian; and Dr. Alison Hutton for her comments on a draft version of this manuscript.