Introduction

Beginning in the mid-1990s, five species of vultures have declined rapidly throughout South Asia (Prakash et. al. 2003, 2007, Gilbert et al. Reference Gilbert, Virani, Watson, Oaks, Benson, Khan, Ahmed, Chaudhry, Arshad, Mahmood and Shah2002, Reference Gilbert, Watson, Virani, Oaks, Ahmed, Chaudhry, Arshad, Mahmood, Ali and Khan2006, Green et al. Reference Green, Newton, Shultz, Cunningham, Gilbert, Pain and Prakash2004, Cuthbert et al. Reference Cuthbert, Green, Ranada, Saravanan, Pain, Prakash and Cunningham2006, Chaudhary et al. Reference Chaudhary, Subedi, Giri, Baral, Bidari, Subedi, Chaudhary, Chaudhary, Paudel and Cuthbert2012). Between 1992 and 2007, road transect counts in India showed that the Oriental White-backed Vulture Gyps bengalensis declined by > 99.9% and the Long-billed Vulture Gyps indicus and Slender-billed Vulture Gyps tenuirostris combined declined by 96.8% (Prakash et al. Reference Prakash, Green, Pain, Ranade, Saravanan, Prakash, Venkitachalam, Cuthbert, Rahmani and Cunningham2007). Cuthbert et al. (Reference Cuthbert, Green, Ranada, Saravanan, Pain, Prakash and Cunningham2006) found an 80.0% decline in Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus numbers and a 91.0% decline in the Red-headed Vulture Sarcogyps calvus using road transect surveys in and near protected areas in India between 1991 and 2003. Based on these changes, four of these species are listed as ‘Critically Endangered’ on the IUCN Red List and the Egyptian Vulture as ‘Endangered’ (IUCN 2013).

The non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) diclofenac is highly toxic to Gyps vultures (Oaks et al. Reference Oaks, Gilbert, Virani, Watson, Meteyer, Rideout, Shivaprasad, Ahmed, Chaudhry, Arshad, Mahmood, Ali and Khan2004, Swan et al. Reference Swan, Cuthbert, Quevedo, Green, Pain, Bartels, Cunningham, Duncan, Meharg, Oaks, Parry-Jones, Shultz, Taggart, Verdoorn and Wolter2006). Vultures are exposed to diclofenac when they feed upon carcasses of domesticated ungulates that have been treated with the drug shortly before death (Oaks et al. Reference Oaks, Gilbert, Virani, Watson, Meteyer, Rideout, Shivaprasad, Ahmed, Chaudhry, Arshad, Mahmood, Ali and Khan2004, Swan et al. Reference Swan, Cuthbert, Quevedo, Green, Pain, Bartels, Cunningham, Duncan, Meharg, Oaks, Parry-Jones, Shultz, Taggart, Verdoorn and Wolter2006). Green et al. (Reference Green, Newton, Shultz, Cunningham, Gilbert, Pain and Prakash2004) estimated that less than 0.8% of ungulate carcasses available to foraging vultures would need to contain a lethal dose of diclofenac for this to have caused the observed population declines. Sampling tissues from carcasses of domestic ungulates in India between 2004 and 2005 showed that the proportion contaminated with diclofenac and the concentration of the drug in their tissues were sufficient to have caused vulture declines at the observed rates without the involvement of any other factor (Green et al. Reference Green, Taggart, Senacha, Raghavan, Pain, Jhala and Cuthbert2007).

Efforts to achieve voluntary withdrawal of use of veterinary diclofenac began in 2004. The licence to manufacture veterinary formulations of diclofenac was withdrawn by the Drug Controller General of India in 2006. The ban was adopted in Pakistan and Nepal in the same year and in Bangladesh in 2010. Domesticated ungulate carcass sampling in India since the 2006 ban has shown a decline in the prevalence and concentration of diclofenac in their tissues (Cuthbert et al. Reference Cuthbert, Taggart, Prakash, Saini, Swarup, Upreti, Mateo, Chakraborty, Deori and Green2011) and road transect surveys indicate stabilisation of the populations of Long-billed and Slender-billed Vultures, and a possible increase in the Oriental White-backed Vulture population in India between 2007 and 2011 (Prakash et al. Reference Prakash, Bishwakarma, Chaudhary, Cuthbert, Dave, Kulkarni, Kumar, Paudel, Ranade, Shringarpure and Green2012). Similar population increases have been observed in Pakistan (Chaudhry et al. Reference Chaudhry, Ogada, Malik, Virani and Giovanni2012) and Nepal (Prakash et al. Reference Prakash, Bishwakarma, Chaudhary, Cuthbert, Dave, Kulkarni, Kumar, Paudel, Ranade, Shringarpure and Green2012).

It is not currently known if Egyptian and Red-headed Vultures are susceptible to diclofenac poisoning. However, both species are likely to show the similar physiological intolerance and exposure risk to diclofenac through a common ancestry and foraging niche with Gyps vultures (see Discussion). In other parts of their range, Egyptian and Red-headed Vultures are threatened by a variety of problems (Ogada et al. Reference Ogada, Keesing and Virani2012), including changes in natural and agricultural systems (Liberatori and Penteriani Reference Liberatori and Penteriani2001, Clements et al. Reference Clements, Gilbert, Rainey, Cuthbert, Eames, Bunnat, Teak, Chansocheat and Setha2012), but mainly targeted and non-targeted poison baiting (Hernández and Margalida Reference Hernández and Margalida2009, Clements et al. Reference Clements, Gilbert, Rainey, Cuthbert, Eames, Bunnat, Teak, Chansocheat and Setha2012) and electrocution on poorly designed power lines (Angelov et al. Reference Angelov, Hashim and Oppel2013). These same problems certainly affect South Asian populations to some extent, but do not explain the rapid and widespread declines observed (Prakash et al. Reference Prakash, Pain, Cunningham, Donald, Prakash, Verma, Gargi, Sivakumar and Rahmani2003, Cuthbert et al. Reference Cuthbert, Green, Ranada, Saravanan, Pain, Prakash and Cunningham2006). Alternatively, Green et al. (Reference Green, Newton, Shultz, Cunningham, Gilbert, Pain and Prakash2004, Reference Green, Taggart, Senacha, Raghavan, Pain, Jhala and Cuthbert2007) demonstrated that diclofenac explained similar rapid and widespread declines in Gyps vultures. Therefore, it is highly likely that the populations of Egyptian and Red-headed Vultures in India have been affected, like Gyps vultures, by the widespread veterinary use of diclofenac and its subsequent ban in 2006.

In this paper, we update a previous analysis of counts of the two species in protected areas in India by Prakash et al. (Reference Prakash, Pain, Cunningham, Donald, Prakash, Verma, Gargi, Sivakumar and Rahmani2003) and Cuthbert et al. (Reference Cuthbert, Green, Ranada, Saravanan, Pain, Prakash and Cunningham2006), using results from two further surveys in 2007 and 2011. We examine if, as reported for the Gyps vultures, the population declines of Egyptian and Red-headed Vultures have slowed flowing the ban on diclofenac.

Methods

Vulture surveys

Vultures were counted along roads within and immediately surrounding protected areas (national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, plus a 25 km-wide buffer zone) in northern India (Table S1). Surveys were first conducted in one of the years between 1991 and 1993, when 14 protected areas were surveyed (Samant et al. Reference Samant, Prakash and Naoroji1995). Following Cuthbert et al. (Reference Cuthbert, Green, Ranada, Saravanan, Pain, Prakash and Cunningham2006) we treat this first survey in the analysis as having occurred in the same year, 1992. Beginning in 2000, we surveyed 18 protected areas, including the original 14 areas. Each of these 18 protected areas was surveyed in at least two of the years 2000, 2002, 2003, 2007 and 2011; however, not all areas were surveyed in all survey years. The results are shown in Table S1 in the online Supplementary Materials. Results for years before 2007 are the same as previously reported in Samant et al. (Reference Samant, Prakash and Naoroji1995), Prakash et al. (Reference Prakash, Pain, Cunningham, Donald, Prakash, Verma, Gargi, Sivakumar and Rahmani2003) and Cuthbert et al. (Reference Cuthbert, Green, Ranada, Saravanan, Pain, Prakash and Cunningham2006).

Table 1. The log-likelihood (L), number of parameters (K), Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), AIC difference (Δi) and AIC weight (wi) for different models fitted to count data of Egyptian Vulture and Red-headed Vulture. The largest w i for each species is shown in bold. The three different types of zero-inflated Poisson models have different predictors in a binary component that are shown in brackets.

Surveys were made between March and June, coinciding with the post-fledging period for both species (Naoriji Reference Naoroji2006). Transects were surveyed from a motor vehicle with a driver and an experienced observer. The vehicle was driven at 10–20 km/h within protected areas and at ∼50 km/h in the buffer zones surrounding the protected areas. Across repeated surveys, routes and survey effort were the same. All vultures observed soaring and roosting within 500 m on each side of roads were recorded. The length of road surveyed in each protected area depended on the size of that protected area. The 1992 survey covered 5,800 km of transects, whilst the later surveys covered 6,800 km.

Statistical analysis

Population changes have been usually estimated from count records by fitting a generalised linear model (GLM) with a log link and a Poisson error distribution (Gregory and van Strien Reference Gregory and van Strien2010). However, the data used in this study include many zero counts as well as a few large values (Table S1). Ignoring such over-dispersion can lead to underestimation of standard errors and misleading inference for the parameters of interest (Okamura et al. Reference Okamura, Punt and Amano2012). For this reason, we fitted three types of models to each dataset (see below) and compared their performance based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (Burnham and Anderson Reference Burnham and Anderson2002). Despite a small ratio between sample size and the number of parameters (< 40) for both species, we did not use the second-order AIC (AICc) as this is normally derived assuming Gaussian error distributions and is difficult to compute for other error distributions (Burnham and Anderson Reference Burnham and Anderson2002). We subsequently calculated AIC difference (Δi) and Akaike weight (w i) for each model, where Δi is the difference between the AIC of the ith model and the smallest AIC value in the model set. The ratio of the Δi of each model relative to the model set, w i , thereby provides a measure of the strength of evidence for each model being the best model. The model with the smallest AIC was defined as the single best model if that model had a w i≥ 0.9, and was used to develop population indices. If this was not the case, model averaging was performed by summing parameter estimates weighted by respective w i values across all models.

The first model was a GLM with a log link and a Poisson error distribution (P). In this model, site and year were treated as factors to allow for sites that were not surveyed in every year, the model being loge(c ij) = g i+ h j, where c ij is the expected value of the count at the ith site in the jth year, g i is the site effect for the ith site, and h j is the year effect for the jth year. Population indices in the jth year, scaled relative to the first year of the series, were calculated as index j = exp(h j)/exp(h 1).

The second model was a GLM with a log link and a negative binomial error distribution (NB). This model is essentially the same as the P model above, apart from assuming a negative binomial error distribution instead of a Poisson error distribution. The third model was a zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) model that has two components that correspond to two sources of zeros: the first is based on a binary error distribution that generates excess zeros; and the second component is based on a Poisson error distribution that generates counts, some of which may be zeros. In this study, the first binary component was modelled with a logit link and three different predictors: intercept only, year effect only, and site effect only. Here both site and year effects were not considered together in the binary component as the probability of an excess zero (π, see below) is dependent on both sites and years in such a model, making it impossible to estimate population indices that are independent of sites. The second Poisson error component was modelled with the same structure as the Poisson GLMs. Consequently, the model equation is c ij = π·0 + (1 - π)·exp(α i + β j), where π is the probability of an excess zero from the binary error component, and α i and β j are the site effect for the ith site and the year effect for the jth year, respectively, from the Poisson error component. Note here that π is modelled using any of the three different sets of predictors above. For ZIP models, population indices were calculated as index j = c ij / c i1 = exp(β j)/exp(β 1) if the binary component was modelled with intercept only or site effect only, and index j = c ij / c i1 = (1 - π j)·exp(β j)/ (1 – π 1)·exp(β 1) if it was modelled with year effect only. Since the ZIP model with the smallest AIC did not include the site effect in the binary error component (see Results and Table 1), population indices were not affected by the choice of a site in the calculation. Following Fewster et al. (Reference Fewster, Buckland, Siriwardena, Baillie and Wilson2000), 95% confidence intervals for the indices were estimated by 999 bootstrap iterations, based on the best model or all models if estimates were obtained through model averaging. For the latter, a proportion of the total bootstrapped samples were obtained for each model based on its w i.

We estimated the average annual rate of population change, as a percentage, in the period between two consecutive surveys at times i and j, as 100·((index j/ index i)1/(j-i) - 1) and obtained 95% confidence limits of these rates by the bootstrap samples. To test whether the annual rate of population change had altered over time, we also calculated a difference in the two successive estimates of the annual rate of population change and its 95% confidence limits, using the same bootstrap samples. This calculation was performed only for data after 2000 as population declines may have started part way through the period between 1992 and 2000, potentially causing the estimated annual rate for this period to be biased low.

All models were implemented using R (R Development Core Team 2013) using the packages ‘MASS’ (Ripley et al. Reference Ripley, Venables, Hornik, Gebhardt and Firth2013) for NB and GLMs, and ‘pscl’ (Jackman et al. Reference Jackman, Tahk, Zeileis, Maimone and Fearon2012) for ZIP models.

Results

The proportion of protected areas (and surrounding buffer zone) in which each species was counted decreased from 57% in 1992 to 17% in 2011 for both species (Table S1).

ZIP models gave smaller AIC values and consequently larger w i values than the Poisson and NB GLMs for both Egyptian and Red-headed Vultures (Table 1). Regarding the structure of the binary component in the ZIP models, the model with intercept only and year only had the largest w i values for Egyptian Vultures and Red-headed Vultures, respectively (Table 1). The ZIP (year) model for Red-headed Vultures had a w i > 0.9; hence, we estimated population indices and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals from this single best model. The ZIP (intercept) model for Egyptian Vultures had a w i < 0.9; hence, we model averaged estimates and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals across all five models.

For both Egyptian and Red-headed Vultures the survey results indicated a substantial population decline between the early 1990s and the early to mid-2000s, with the Egyptian and Red-headed Vulture declining by 91% (from 1992 to 2007; Figure 1) and 94% (from 1992 to 2003 Figure 2), respectively. However, there was evidence of a partial recovery in populations of both species in the late 2000s (Figures 1-2). In the 2011 survey, the population indices for Egyptian and Red-headed Vultures were 46% and 25% of those in the 1992 survey, respectively; and 75% and 62% of those in 2000, respectively. For both species, the population index in 2011 was significantly lower than that in 1992 (percentage change in indices [95% confidence interval]: -54.11[-100.00, -37.82] for Egyptian Vulture; -75.13 [-98.08, -18.54] for Red-headed Vulture). This was higher than the three previous surveys from 2002 to 2007, although wide confidence intervals led to these differences being non-significant.

Figure 1. Population index values for Egyptian Vulture surveyed in 18 protected areas in India between 1992 and 2011. Indices are population densities relative to that in 1992, estimated by a zero-inflated Poisson model with only the intercept in the binary component (see Methods for more detail). Vertical lines show estimated 95% confidence limits.

Figure 2. Population index values for Red-headed Vulture surveyed in 18 protected areas in India between 1992 and 2011. Indices are population densities relative to that in the 1992, estimated by a zero-inflated Poisson model with the year effect in the binary component (see Methods for more detail). Vertical lines show estimated 95% confidence limits.

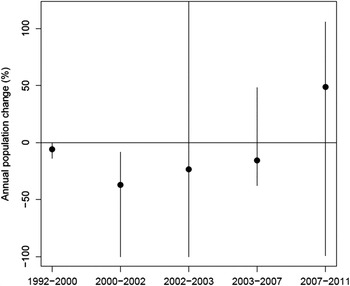

The estimated annual rates of population change showed that the population trend was significantly negative between 1992 and 2002 for both the species, but has turned to positive since 2007 for Egyptian Vulture (Figure 3) and since 2003 for Red-headed Vulture (Figure 4), although for both the species, the 95% confidence interval overlapped zero, leading to statistically non-significant increases. However, for Egyptian Vulture the proportion of bootstrapped samples that showed a positive increase after 2007 (the year the population trend appeared to reverse for this species; Figure 1) was 73%. Similarly, for the Red-headed Vulture the proportion of bootstrapped samples that showed a positive increase after 2003 (the year the population trend appeared to reverse for this species; Figure 2) was 87%.

Figure 3. The rate of population change (% per year) of Egyptian Vulture. Circles show average annual rates between each pair of consecutive surveys with their 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (vertical lines). Note that the upper confidence limits for 2002–2003 (130.05) go beyond the range of the figure.

Figure 4. The rate of population change (% per year) of Red-headed Vulture. Circles show average annual rates between each pair of consecutive surveys with their 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (vertical lines). Note that the upper confidence limits for 2002–2003 (5.66·109) goes beyond the range of the figure.

Changes in the annual rates of population change after 2000 were mostly positive, except the most recent period for Red-headed Vulture (Egyptian Vulture: 2000–2002 to 2002–2003 = 13.7; 2002–2003 to 2003–2007 =7.6; and 2003–2007 to 2007–2011 = 64.3. Red-headed Vulture: 2000–2002 to 2002–2003 = 13.6; 2002–2003 to 2003–2007 = 65.3; and 2003–2007 to 2007–2011 = -11.7). However, the 95% confidence interval overlapped zero in all cases.

Discussion

The declines in Egyptian and Red-headed Vulture populations in India between the 1990s and early to mid-2000s appear to have slowed. Specifically, our results suggest that for both species the probability of population increases, based on the proportion of bootstrapped samples that showed a positive population increase, is higher than the probability of population declines.

Our estimates of population trends are imprecise because the numbers of each species encountered on each survey and the numbers of sites surveyed were small, particularly in later years; reinforcing the point that while the declines appear to have slowed, populations remain small. In addition, vulture observations were increasingly concentrated in a small number of sites. For example, 33 of the 42 Egyptian and 27 of the 30 Red-headed Vultures counted in 2011 were counted in a single, but different, protected area (Desert and Bandhavgarh National Parks, respectively; Table S1). These considerations resulted in wide confidence intervals for the estimated population indices and annual rates of change, preventing us from concluding with certainty that both the species have indeed begun to increase. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that populations of these two vulture species in the whole of India are continuing to decline. Further, the apparent annual rate of population increase should be treated with caution due to the point estimate for the rate of increase in Egyptian Vultures from 2007 to 2011 (Figure 1) is beyond the maximum growth that is likely for a long-lived raptor species (∼10% per year; Niel and Lebreton Reference Niel and Lebreton2005). Despite these caveats, the available evidence indicates that populations of both species are no longer declining as rapidly as they were in the early 2000s.

Two areas of high vulture numbers (Desert and Bandhavgarh National Parks) no doubt contributed greatly to our estimates of population increases in 2011. However, we have no reason to think that counts in these areas, in that year, were anomalies. In fact, comparable numbers of Egyptian Vulture have been counted in the Desert National Park in past surveys (see Table S1); and Bandhavgarh National Park was known to support large numbers of Red-headed Vultures prior to the species’ decline (V. Prakash unpubl. obs). Unfortunately we first surveyed the latter park after the decline in the species had begun (2000). These parks appear to contain good habitat for the respective species and therefore it is reasonable to assume, if populations are increasing, that we would see increases in these parks first. We are unaware of supplementary interventions for recovery of either species at these sites. However, we do know that the extent of diclofenac use differs geographically (Cuthbert et al. Reference Cuthbert, Taggart, Prakash, Saini, Swarup, Upreti, Mateo, Chakraborty, Deori and Green2011); hence, its use in these particular sites might be lower than in elsewhere.

Our results for Egyptian Vulture and Red-headed Vulture resemble recent changes in population trends of Oriental White-backed, Long-billed and Slender-billed Vultures in India and Nepal (Prakash et al. Reference Prakash, Bishwakarma, Chaudhary, Cuthbert, Dave, Kulkarni, Kumar, Paudel, Ranade, Shringarpure and Green2012). The slowing of the declines in these three species of Gyps vultures in India coincided with the introduction in 2006, and increasing effectiveness, of a ban on the veterinary use of diclofenac. The magnitude of the observed, recent, positive change in population trend in India of the Oriental White-backed Vulture is consistent with that predicted from reductions in the level of diclofenac contamination of domesticated ungulate carcasses observed after the ban (Cuthbert et al. Reference Cuthbert, Taggart, Prakash, Saini, Swarup, Upreti, Mateo, Chakraborty, Deori and Green2011, Prakash et al. Reference Prakash, Bishwakarma, Chaudhary, Cuthbert, Dave, Kulkarni, Kumar, Paudel, Ranade, Shringarpure and Green2012). Although there is no direct evidence that either Egyptian or Red-headed Vultures are sensitive to diclofenac toxicity, the reduction in diclofenac contamination of domesticated ungulate carcasses in India may have also benefitted these species. There are two forms of evidence that support the idea that diclofenac poisoning has caused the observed declines in Egyptian and Red-headed Vultures: 1) a common ancestry with Gyps vultures (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Barrowclough, Groth and Mertz2007); and 2) an overlapping diet with Gyps vultures (Naoroji Reference Naoroji2006). Recent evidence of diclofenac residue and visceral gout in non-Gyps scavenging raptor species found dead in Indian carcass dumps suggest that a greater diversity of Accipitridae species may be susceptible to diclofenac poisoning than earlier thought (Sharma et al. in this issue). Further, despite having wider foraging niches than Gyps vultures (which specialise on large ungulates), both the Egyptian and Red-headed Vultures certainly feed on domesticated ungulate carcasses and may have increased this source of food in their diet in the wake of the Gyps vulture declines (Cuthbert et al. Reference Cuthbert, Green, Ranada, Saravanan, Pain, Prakash and Cunningham2006). We have no data on causes of individual mortality for either Egyptian or Red-headed Vultures, and acknowledge that vulture species worldwide face numerous threats, but know of no threat, other than diclofenac poisoning, that could have caused such large and widespread declines as those observed in these species during the 1990s to early 2000s (see Green at al. 2004, 2007).

Confirmation of the sensitivity to diclofenac of both Egyptian and Red-headed Vultures is needed in order to verify that the nationwide reduction in diclofenac contamination is indeed responsible for the slowing of population declines in these species. Nonetheless, our results show more encouraging population trends for two more threatened vulture species in India, after the 2006 ban on veterinary diclofenac.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary materials for this article can be found at journals.cambridge.org/bci

Acknowledgements

We thank the Ministry of the Environment and Forests (Government of India) for their support in conducting this research. Financial support: The UK Government Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs’ Darwin Initiative (18-008) and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.