1 Introduction

This Element explores early modern English manuscripts and printed travel accounts as efforts to record travellers’ mobile lives, turning our gaze to the ‘inner worlds’ and lives of travellers. It approaches travellers’ writings both as records and expressions of their experiences and as avenues for their descriptions and ‘fashionings’ of the self, investigating the many ways travellers’ texts were both drinking from the autobiographical font and contributing to it. In doing this, the Element recalibrates scholarship on early modern travel and travel writing and offers a change in perspective: rather than exploring a traveller’s gaze towards the foreign, or continuing on the tried and tested paths of studying early modern travel – from pilgrimage to Grand Tour – as a separate and somewhat decontextualised, even esoteric topic, it considers travel writing as a form of life writing, simultaneously turning the gaze both inwards and outwards. It suggests we explore how travellers described their journeys while also writing themselves and their inner lives and embodied experiences into the story. This move, I argue, provides not only new rich evidence about travel in this period but also helps to show how and why mobility mattered deeply to early modern people and should thus be brought back to the mainstream of scholarly discussions of this period (Reference WilliamsWilliams 2019; Reference GallagherGallagher 2017). Paying more attention to travel writing as a form of life writing will also help us read travel and travellers’ experiences in a more nuanced way, equipped with decades of new work on mobility, life writing, and histories of embodied experience (Reference HolmbergHolmberg 2017).

Travel writing has often been dismissed from the fold of ‘ego documents’ or life writing on the grounds that its focus is not, or at least not sufficiently, on the description of lives and ‘the self’ of its authors (Reference SummerfieldSummerfield 2019, pp. 4–5).Footnote 1 However, rather than drawing boundaries between what might have constituted ‘travel writing’ and ‘life writing’ in this period – a useless task, as people did not have a clear idea of such generic boundaries in this period – this Element aims to explore their meeting points and entanglements with the help of three case studies. Early modern genres were fuzzy and constantly overlapping, even when they were interpreted or imposed by later researchers, and there is no real consensus over the meaning of ‘life writing’, ‘ego document’, or autobiographical text in this period (Reference HadfieldHadfield 2009; Reference LegassieLegassie 2017; Reference RubiésRubiés 2000a; Reference StewartStewart 2018). Therefore, in our future studies, it seems essential to explore the shared overlaps, borrowings, citationality, and varied forms of travel and life writings, rather than search for any clear categories. Focusing our efforts only on the printed single-authored accounts of travel prioritises a certain type of traveller (i.e. white, elite, and male, admittedly the types of traveller even this study concentrates on) over others and allows other types (i.e. mobile non-elites, women, and people of colour) to fall through the cracks altogether. Moreover, this kind of fuzziness, or even ‘messiness’ with boundaries, allows early modern mobility to appear as a richer and messier phenomenon, while at the same time interrogating travel accounts with as much nuance as any early modern autobiographical account and reveals them as fascinating sources for histories of experience (Reference HolmbergHolmberg 2019).

Due to and enabled by the aforementioned slippery early modern genre-boundaries, travel themes often cropped up in and were ‘travelling’ between texts that have not previously been investigated as vehicles or receptacles of travel writing. These textual forms included manuscripts, commonplace books, family books, logbooks, diaries, spiritual autobiographies, and miscellaneous notebooks. Some of the texts processed and recorded themes that were eventually published, while some remained in manuscripts (Reference WyattWyatt 2021). These texts offer both new data and material insights into the preservation and recording of travel experiences, and how travellers selected, processed, and decided what to preserve about themselves and their travels for posterity. Investigating a wider variety of texts as not only travel writing but also as life writing allows for the inclusion and investigation of a greater variety of travellers from diverse social backgrounds. In addition, this type of investigation helps us to see how writing and recording itself could ‘travel’ between genres and textual forms into more polished accounts in manuscripts and published travel collections and compilations. Such investigations will also allow the discovery of avenues for life writing and self-recording outside the later ‘dominant templates’ of the diary and the autobiography, as shown by Adam Smyth among others (Reference AmelangAmelang 1998; Reference SmythSmyth 2010). Sources of manuscript travel accounts include textual forms such as almanacs and financial account books and can be approached as rich presentations of the self that were often in motion, similar to their mobile authors.Footnote 2 Investigating these texts requires interdisciplinarity and a broad set of methodological tools that have been developed to capture the richness of human experience, ranging from autobiography, life writing, and material texts to the study of the history of lived and embodied experience, including the history of emotions and senses. All of these will be tackled more fully in the sections that follow (Reference CanningCanning 1994; Reference BoddiceBoddice 2023).

Where can we look for the travellers’ ‘self’, their subjectivity, or even a small part of their often-elusive experiences as travellers? At first glance, it might seem that pilgrimage modes and narratives granted more room to explore the inner spiritual life and pursuits of a pilgrim, whereas secular travel by traders, diplomats, and educational travellers such as the ‘Grand Tourists’ would have focused more on the production of knowledge of foreign lands. However, this kind of division is unhelpful when we want to appreciate the richness of early modern travellers’ experiences and the many contexts and modes of their writing (Reference HolmbergHolmberg 2019). In fact, travellers’ descriptions of their embodied experiences and secular interests cropped up in pilgrimage reports and secular accounts alike, in the descriptions of illness and ailing, efforts to visualise their experiences and persona, and practices of still commemorating and writing about their travels a long time after the travels had ended. In addition to the more ephemeral sources of travel experience, like the often-vanishing materiality and objects related to travels, it is vital we reconsider traditional sources such as logbooks, letters, and travel diaries and also other well-trodden tracks of retrospective travel writing from new angles. As is typical of writers in general, historians tend to gravitate towards individuals and stories that resonate with them; thus, we need to remember that our stories should reflect the diversity of the early modern world. This research practice throws light on the overlap and shared ways of thinking of aristocratic and elite travellers, travellers from the merchant class, and people who tended to fall in between or outside these categories such as women, servants, mariners, or marginalised people.

This introduction aims to take stock of the range of possible approaches to writing about travellers’ mobile lives in auto/biographical, historical, and literary studies – not a small task. It will also suggest and present some new ways to write cultural histories of mobile people, engaging with scholarly approaches such as global microhistories, history of experiences, emotions, and senses; and, perhaps more critically, with the immediate theoretical backgrounds in the study of Renaissance individualism, ‘self-fashioning’, and literary identity formation. All these approaches and some of their tools (if honed and focused onto mobile people) could and should be employed in the study of both more ‘genre-conforming’ travel writing and other miscellaneous texts that were the products of early modern mobility. When we focus our gaze on the central figure of the traveller, equipped with these tools, we gain more insight not only into the process of the production of these varied texts but also their social motivations and ideological aims, without reverting to the old ways of simplistic and anachronistic psychological explanation of the intentions of traveller ‘authors’ and their individual sensibilities. My wider claim is that we are missing the lens through which early modern people themselves saw and described their world; that is, we fundamentally misunderstand these texts unless we look at them through the lens of autobiography and life writing. This Element develops this discussion by making three essential claims and contributions:

1. Embodiment is one of the most direct routes to the self in travel writing.

2. Considering a wider range of travel writing types will acknowledge a greater range of people than the traditional historiography of travel.

3. In our reading, we need to appreciate how most travel writing is retrospective and commemorative, not just of individual travellers but also of their experiences and social relations.

The field of Renaissance studies has a complex history of discussions about individuality and the self as a result of the foundational stones laid by Burckhardt and a vibrant and ongoing interest in autobiographical and biographical studies (Reference MartinMartin 2018; Reference Dragstra, Ottway and WilcoxDragstra, Ottway, and Wilcox 2000). The range of studies has expanded from those of ‘great’ men and women to include studies of ‘exceptional typical’ individuals in microhistories, group biographies, and studies of local communities that explore the contours of their agency/ies (Reference Farr and RuggieroFarr and Ruggiero 2019). Scholarly discussions have likewise moved on from debates about the various ‘births’ of individuality during the European Renaissance to investigating the framings, representations, fashioning, and boundary-making regarding the ‘self’; Greenblatt’s Renaissance Self-Fashioning inspired the most discussion about the limits of performance and individual agency in literary representations of the self (Reference Coleman, Lewis and KowalikColeman, Lewis, and Kowalik 2000; Reference HaydonHaydon 2017; Reference Mayer and WoolfMayer and Woolf eds. 1995; Reference Sharpe and ZwickerSharpe and Zwicker 2008).Footnote 3 The well-worn dictum about ‘travellers lying by authority’ and the suspicions directed at both autobiographies and travellers might cause us to assume that travel writers’ strategic motivations and ‘self-fashioning’ resulted in both their ‘real’ lived experiences and lives becoming ‘hidden’ from view, and that travel developed into a self-reflective practice only later in the eighteenth century (Reference 68HadfieldHadfield 2017). However, the fact that something is ‘fashioned’ or ‘performative’ does not mean it is untrue or that a narrative has no basis in lived experience; this study does not aim to discover all the lies and deceptions of travellers (that would be really boring indeed), but rather attempts to trace the wider contours and meanings they gave to their mobility in the context of their lives.

Currently, individual identity is increasingly seen in the context of the manifold relationships between early modern people and their changing settings and communities, shaped, produced, and represented in intersecting social and cultural formations, occupational roles, and relations (Reference Hailwood and WaddellHailwood and Waddell 2023; Reference PaulPaul 2018; Reference ShepardShepard 2015; Reference Scott-WarrenScott-Warren 2016; Reference WaddellWaddell 2019). Scholars have occasionally chosen to emphasise the structures that restricted early modern people, sometimes viewing the contexts they operated in as accommodating them and giving their lives meaning and purpose, often both. Sometimes ‘the self’ has been approached as more ‘relational’ and ‘social’, while other times as a more isolated ‘interiority’ and entity of an individual experiencing subject (Reference Fulbrook and RublackFullbrook and Rublack 2010). Despite efforts to kill the ‘author’ or ‘agency’ in mid-twentieth and twenty-first century literary criticism (along with the change in focus after the linguistic turn to discourse and representation), questions about the shape of the self and the contours of subjectivity did not disappear from the fields of autobiography and life-writing studies, even if separate schools of thought and rifts occasionally appeared between historians and literary scholars who occupied the scholarly territory.Footnote 4

Microhistory, one of the great historical trends after the linguistic turn, has blossomed since Carlo Ginzburg, Natalie Zemon Davis, and others introduced the benefits to history of the combined micro- and macroscopic gaze (Reference Davis, Thomas, Sosna and DavidN. Davis 1986; N. Reference DavisDavis 1988; L. Reference DavisDavis 2002). Microhistory has provided social and cultural historians an entry to the playing field usually occupied by literary scholars, biographers, and talented storytellers writing for the general public, focusing their historical scholarly gaze not only on famous individuals but also obscure and marginal figures, with the aim of illuminating larger structures and mentalities. The ‘global microhistory’ approach can supply tools for studying the travelling self, provided it does not succumb to the impulse of only investigating global figures who successfully crossed cultural boundaries and provide inspiration and points of identification for our times and ourselves. In addition to Davis’ Leo Africanus, Linda Colley’s Elizabeth Marsh or John-Paul Ghobrial’s Elias of Babylon, we also need studies of travellers whose ‘travails’ were perhaps less inspiring, with duller outcomes and scarcer paper trails, from the labouring poor to the servants who travelled in the entourages of princes and aristocrats, or the sailors and mariners who plundered and struggled around the globe (Reference DavisDavis 2006; Reference ColleyColley 2007; Reference GhobrialGhobrial 2014). Only by widening our lens in this way will we gain a fuller picture of how people understood their mobility in this period (Reference AnsellAnsell 2015; Reference Charmian.Mansell 2021; Reference WilliamsWilliams 2019). Often the paper trails go cold, with exceptional or norm-challenging individuals leaving more traces of both themselves and their travels than those less exceptional, but this should not prevent scholars from setting up wider nets to catch their experiences. It has been argued by scholars in mobility studies that we should also try to follow our subjects throughout their whole lives, capturing their ‘ongoing’ mobilities, returns, and back-and-forth movements, in addition to more direct movements between ‘point A and point B’. In this, a more biographical approach truly helps, showing that the same people often travelled beyond the geographical focuses of scholarship on travels in the Levant or South-East Asia. How these practices and experiences of worldwide mobility shaped traveller’s self-writing should be among the questions we investigate and contexts we consider (Reference RobertsRoberts 2012; Reference Sau and Eissa-BarrosoSau and Eissa-Barroso 2022).

The recent expansion and flourishing of the study of early modern life writing has had a relatively limited effect on the ways of studying travel writing prior to the Grand Tour. In the context of mobility and travel studies, questions of ‘the self’ or life writing have also been of little interest, apart from occasional efforts to excavate the backgrounds of travellers to include a short biography (e.g. ‘X was born in Y to middling sort/gentry parents’) in opening sections. Instead of a traveller’s life and self, scholars of travel writing have more often explored travellers’ authorship and rhetoric: their credibility and authority building, rhetoric of knowledge and race-making, and gaze towards foreignness and otherness, that is key questions of identity, power, and representation (Reference Kuehn and SmethurstKuehn and Smethurst eds. 2015; Reference Kamps and SinghKamps and Singh 2001; Reference SinghSingh ed. 2009). I am not suggesting we turn our gaze away from these important questions, but rather, in addition to seeing travellers as travel writers and ‘knowledge producers’, that we also see them as life writers: writers of a significant, memorable, and curious mobile part of their own life, writing that took several forms from short personal notes to longer efforts to clear one’s name, as authors who were very aware of how they were presenting themselves in their texts.Footnote 5 Usually the two general aims of knowledge production and life writing became entangled and difficult to fully separate; there is neither a need to separate these nor to get rid of advances already made. As I already mentioned, both are needed to understand these texts.

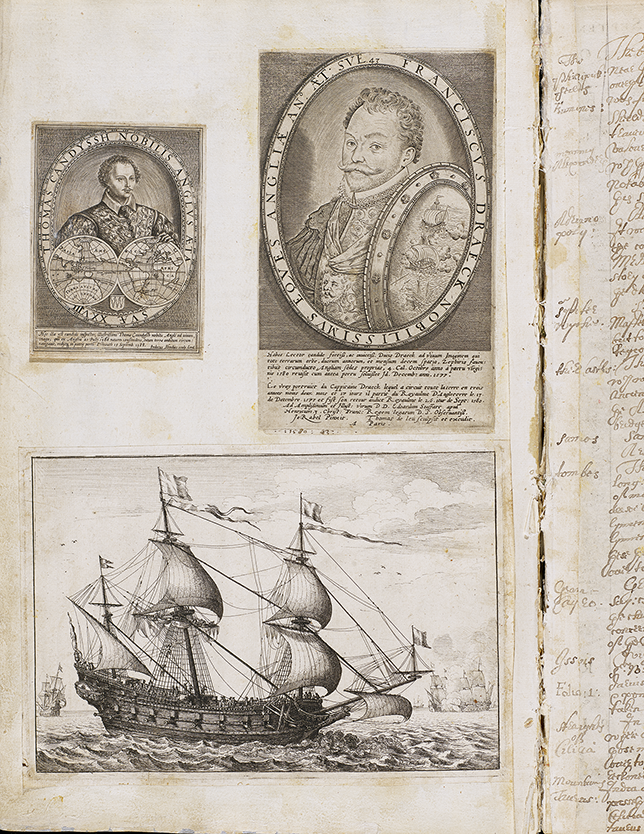

In one rare overview of the field, Simon Cooke presents a trajectory of travel writing beginning with Herodotus’ Histories, which he terms as a search for an ‘autobiographically inflected form of travel writing’ (Reference Cooke and ThompsonCooke 2016). Cooke proceeds quite quickly to his own period of expertise, the eighteenth century, where he places the ‘inward turn’ in travel writing and consequently his own focus. For example, Christopher Columbus, Francis Drake, and Walter Raleigh are quickly dismissed because ‘the first-person self and its transformations through travel are not the focus of the account’ (Reference Cooke and ThompsonCooke 2016, p. 16).

Similar to Cooke, the pioneering Dutch historian of autobiography and ego-documents, Rudolf Dekker, excluded several travel journals from his study of Dutch travel accounts. For inclusion in the study, ‘the author had to write about his own experiences or provide personal commentary’; materials held in private collections were not taken into account; ‘impersonal accounts’, that is more schematic materials and guidebooks, were not admitted; and only accounts ‘that were written on a personal initiative’ were accepted (Reference DekkerDekker 1995, 278). It is important to recognise the differences in scope and purpose of the varied travel writings. However, sieving them to separate and qualify only the accounts with enough interiority and sensibility often leads to only studying the ‘usual suspects’ of travel writing, thus separating these texts from their contexts – as was the case with guidebooks and earlier printed accounts, which often significantly shaped single-authored travellers accounts by providing them with structure and subject matter alike (Reference Enenkel and de JongEnenkel and de Jong 2019; Reference MacLeanMacLean 2004a; Reference Palmer, Andrea and McJannetPalmer 2011). We need to ensure that we facilitate revealing the specific ways that travel writings present a traveller, and for that we should not categorise too much beforehand.

Although often fluid or fluctuating, genre-boundaries can sometimes help to articulate differences in representations of the travelling and mobile self. Unlike scholars who have dismissed earlier travel writings from the fold of life writing, Zoë Kinsley has argued that travel writing has been too often and too easily conflated with autobiography (Reference KinsleyKinsley 2014). Her analysis of eighteenth-century English women’s accounts of their ‘home tours’ has demonstrated that a writer’s relocation from home often invited more self-reflections than more familiar surroundings, a phenomenon we can still see at work (Reference KinsleyKinsley 2014, p. 72). However, she also warns that if we expect early modern travel writing to always offer very clear ‘autobiographical revelations’, we are bound to be disappointed and should instead be mindful of the ‘complex and varied nature of travelogues’ (Reference KinsleyKinsley 2014, p. 73). It has also been pointed out by Meredith Skura that if we judge early modern (travel) texts according to later conceptions of inwardness and reflexivity, much of it will inevitably fail the test of time and end up being left outside the remits of our studies (Reference SkuraSkura 2008).

Travel accounts, of course, did more than merely describe the deeds of their authors and should not be read as less complex depictions of the ‘travelling self’ than memoirs or autobiographies. The travel accounts depict the alignment of early modern lives with others and with God; ‘others’ refer to intended readers and audiences and also subjects of commemoration in ways that emphasise the individual traveller less than is often expected from autobiographies. In addition, as social and relational texts, travel accounts show, and sometimes show off, the travellers’ connections, contacts, friendships, and family relations due to serving multiple purposes for their authors. Some authors preferred publishing their accounts for a larger audience as an essential way of gaining useful contacts and attracting potential patrons, while other authors preferred circulating their accounts in manuscript form for either smaller coterie audiences or their friends and loved ones. The Elizabethan gentleman John North, illuminatingly studied by John Gallagher, used his manuscript diary to not only record his experiences of travel in Italy but also as a vehicle to maintain and fashion a cosmopolitan and multilingual identity, showing how travellers employed their travel experiences in their self-fashioning after their return (Reference GallagherGallagher 2017).

One of my case studies in this Element concerns seventeenth-century Cornish merchant traveller Peter Mundy (fl. 1597–1667), who wrote in his manuscript travel account Itinerarium Mundii that a large part of his life’s journeys to the East had been performed in the service of others. In contrast, his travels in Britain and the Nordic countries were made to feed his own ‘habituall disposition for travelling’. Stressing the benefits of keeping personal records, writing a travel account enabled Mundy to ‘keepe my owne remembraunce on occasion off Discourse concerning particularities off thes voyages, As allsoe to pleasure such Friends (who might come to the reading thereof) Thatt are Desirous to understand somwhatt off Forraigne Countries’ (Reference MundyMundy 1907, p. 3). For Mundy, account writing, or in his case ‘relation’ writing, also became a lifelong project, which reveals how early modern travellers regarded their voyages as not just necessary to produce knowledge about the world, but also as life-changing personal experiences worthy to be commemorated and pinned down.

By now, I hope to have sufficiently stressed that if we judge early modern (travel) texts according to later conceptions of inwardness and reflexivity, much of it will inevitably fail the test of time and end up being left outside the remits of our studies. Travellers were active shapers of their accounts, recording their associated actions, thoughts, and motivations, aided by vast textual and cultural resources that helped them make sense of their travel experience, very often with hindsight after their travels had ended, and usually through a process of composition in which texts travelled between forms and genres, and were shaped and directed for diverse publics.Footnote 6 One key method of building credibility in travel writing was eyewitnessing by the traveller, who performed and wrote about their own journey, and their other senses, as will be more fully discussed in the next section.

Annoyingly, at least to a nosy and curious researcher of the embodied and emotional experiences of travellers, the early modern traveller’s ‘self’ often manifests itself in very subtle ways, such as through omissions, light editions, and additions, or even strategic vagueness that sought to protect the traveller from harm in sensitive political situations, such as during wartime or when travelling through hostile territories (Reference HolmbergHolmberg 2017). In other circumstances, travellers partook and utilised common autobiographical strategies of presenting and framing themselves, developed further in family books, memoirs, spiritual autobiographies, and vitae of both saints and sinners, apologising for putting their pen to paper, justifying their actions, and dropping both strong and subtle hints at their presence in the events they described. These written mobile lives took many forms, as did their texts, and their occasional fragmentariness should not scare us off.

Travel accounts showed signs of their authors’ autobiographical or ‘life writing’ in both simple and complex ways. In addition to the most well-known textual devices involving the early modern traveller-author being present and framing this presence (the preface, dedicatory epistles, epilogues, side notes, and edits), textual devices particular to travel writing were at their disposal and borrowed from other non-literary modes for the recording and description of the self. These textual devices included (but were not restricted to) financial accounting, logbooks, commonplace books, notes in almanacs, and personal notebooks. Such texts often gave very subtle hints at individual experience and agency and may have included either very short notes about sensory and embodied experiences (that were often placed in side notes or marginalia) or instances where the texts hinted at or revealed the processes of writing and commemoration. These themes will be tackled in the following sections with the help of short case studies and travellers’ texts that lend themselves to examination from these angles.

In the three sections that follow, I aim to apply recent advances in early modern life writing studies to a cultural-historical investigation of early modern travel accounts in order to discover how the variety of modes of autobiographical recording and accounting were used in travel writing. Focusing on three somewhat overlapping themes (embodiment, materiality, and memory), I will show the contexts and themes that invited travellers to describe both their surroundings and their individual experiences.

2 Mediating Experience: The (Ailing) Body, Emotions, and Senses of the Traveller

Descriptions of bodily ailments and suffering were often the clearest markers of travellers’ embodied presence in their writing. They also offered the clearest route to the autobiographical elements of travel writing – in addition to declarations of literary intent, purpose, and apologies for writing badly. These descriptions of very personal and often visceral embodied experiences could range from grief, languishing, and illness to descriptions of torture at the hands of the Inquisition or being beaten by ruffians on the road. They offer us many paths to explore travellers’ autobiographical memory and the writing of their inner worlds during their travels.

Despite being ubiquitous, travellers’ embodiment (and their non-ocular senses) has gained far less attention than travellers’ eyewitnessing and gaze on foreign lands, making the travellers often somewhat disembodied witnesses to foreign lands and peoples. Consequently, eyewitnessing has also taken centre stage over travellers’ other sensory experiences in histories of travel, knowledge, and science.Footnote 7 The focus has long been on the autoptic verification, knowledge-building, and credibility-enhancing aspects of travel writing, investigating its connections with the histories of science and scholarship, and the construction of geographic and ethnographic knowledge (Reference Surekha and WhiteheadDavies and Whitehead 2012; Reference Hacke, Jarzebowski and ZieglerHacke, Jarzebowski, and Ziegler 2021; Reference OrdOrd 2008; Reference RubiésRubiés 2000b; Reference Tarantino and ZikaTarantino and Zika 2019). Accordingly, emotional, sensory, or indeed multisensory experiences of mobility, such as ailing and illness or hallucination, have been seen as distortions or obstacles: they disrupt the gathering of travel knowledge or prevent the traveller from travelling, observing, and witnessing new worlds and have not been the focus of scholarship so far. There are notable exceptions to this, but there is definitely room for more work on travellers’ inner worlds and experiences.Footnote 8

The quintessential knowledge-building strategy we know to expect from early modern travel writing concerns eyewitnessing; but having it as the main focus has led us to pay insufficient attention to the rest of the sensorium – touch, taste, hearing, smell, and their multisensory and synaesthetic combinations – despite the existence of both direct and subtle references to these in archives (Reference JennerJenner 2011). Suffering, illness, and travellers’ descriptions of their embodied experiences can, however, be approached as an integral part of the traveller’s self-writing and not just a method of verification or giving evidence that the traveller wrote about the things he or she had witnessed or felt (Reference SellSell 2012; Reference ThompsonThompson 2007). In fact, I argue here that we cannot fully understand travel writing if we ignore traveller-writers in all their often messy, even gory embodiment by either skipping over these episodes or only mining them for juicy anecdotes. In many cases, especially when corrupted by foreign air or food, following Annemarie Mol’s ideas, the traveller’s stomach arguably participated in making knowledge just as much as their eyes, and we need to examine these moments more carefully, also paying more attention to their ‘fashioning’ of the traveller’s suffering self (Reference MolMol 2021). As an example that will be explored further, illness descriptions were folded with other layers of the traveller’s story: they allowed travellers to not only show fellow feeling for their ailing companions, gratitude for received hospitality at their own time of need, and an occasion to explain the extra costs and troubles their journeys had brought them, but also sometimes offered an occasion to drop hints to future patrons of much-needed support. Ailments also helped in keeping time; these personal embodied experiences of continuous threats to health and cyclical returns of illness helped to mark time (Reference NewtonNewton 2018; Reference ThorleyThorley 2016).

This section explores how travel and mobility invited the recording of the embodied experiences of the traveller, and how these experiences can be approached with the tools of life writing studies to inform our readings of embodiment and its functions in travel writing. Throughout the section, my readings of manuscripts and printed travel writings, concentrating mainly on the manuscript commonplace book and its published sections by Levant Company clerk John Sanderson (fl. 1584–1602), will be in dialogue with new histories of the senses, emotions, and medicine.Footnote 9 My aim is to consider travellers’ embodied experiences as simultaneously affective, intimately entangled, and multisensory and explore how these experiences participated in the writing of the travelling self (Reference SmithSmith 2015).

Embodied experiences of illness and grief were often both sensory and emotional, and in this way, were tied to the commemorative impulses and aims of self-description and life writing: if sufficiently visceral and memorable, they became events. Purpose, context, and form shaped their expression and recording, not only at home but also abroad. My explorations of the representations of bodily experiences of illness and ailing are tied to the construction and fashioning of the ailing and (usually) heroic self of the traveller. Travellers, if they lived to tell the tale, usually survived their illness as a result of connections, providence, and resourcefulness and were consequently compelled to acts of commemoration and gratitude. Experiences of illness, death, and survival during travels, and the ways in which travellers sought to preserve and express their embodied experiences, ranged from subtle hints at not only sight and hearing, that is eye- and ear-witnessing, but also to taste, touch, and smell, which combined in descriptions of ailing and illness. Their embodied nature caused them to become evocative, dramatic, and effective warnings to future travellers, fulfilling the needs of both didacticism and self-fashioning (Holmberg 2021).

Illness abroad could be a life-threatening (just as much as it was life-changing) event, which not only complicated foreign travels but also gave cause to recording the illness for posterity. Whether life-threatening or just annoying, it added to the hardship and costs of travel and required explanations for lost goods or rerouting, and called for both hospitality and gratefulness towards generous hosts and interlocutors who saved the day. Similar to pain, illness qualifies as an event that required comprehension, justification, explanation, and gratitude in the case of recovery (Reference BourkeBourke 2017). Like any other life-changing events, illnesses were worth noting down for the benefit of the (past and future) traveller, their families and relations, and readers further afield. This type of recording for the benefit of self and others explains why serious illnesses were written down, not only in travel writings but also in early modern life writings of all kinds, ranging from travel texts to family books, from commonplace books to memoirs and recipe books, where cures and recipes were both recorded for those who stayed at home and slipped into records that were meant to accompany the traveller (Reference LeongLeong 2013; Reference RankinRankin 2016). Travelling was a dangerous business in this period, not entered into lightly and without thorough preparation. In fact, many authors mention that before setting off on their travel, they had wagered upon their return as a form of financing their travel, a common custom at the time, or only after making a will (Reference ParrParr 2012).

Literature on medical advice to travellers was relatively scarce, which resulted in dedicated health advice to travellers often being scattered in the medical literature from antiquity to the Renaissance (Reference Horden and HarrisHorden 2005). The alchemist, physician, and itinerant scholar Guglielmo Gratarolo’s (1516–1568) Iter Agentium was one of the few pieces of advice available during this time. However, this advice was never translated into English, probably because the market was already saturated by more general advice, and travellers already knew where to seek it: travel books or their own associates for face-to-face or epistolary or ‘guidance’, which required adaptation to specific climates and persons (Reference Cavallo and StoreyCavallo and Storey 2017). Travel writings in both manuscript and print included not only descriptions of symptoms and guesses at causes but also some advice on how to both prevent and cure illness when far from home. In these episodes, foreign lands attack the body of the traveller – making it imperative for the traveller to adapt to foreign airs, waters, and places. They also had to pay more attention to the building blocks of early modern health known as the ‘six non-natural things’, that is air, food and drink, rest and exercise, sleep and waking, excretions and retentions (coitus), and mental affections, all more difficult to control while on the move and away from home, familiar foods, and loved ones (Reference EarleEarle 2014). Quite often, as in the case of John Sanderson, illnesses were significant milestones on the journey through life, which were recorded as life events, among the many other annoyances, obstacles, and hardships of life abroad.

John Sanderson’s Life’s Ailments and Censures

The early modern archive of travels in the Levant is rich in sensory and embodied experiences of travellers, and this is true especially of their varied illnesses and ailments that were rife in the near and far East alike. Most English travellers and traders of the early modern period knew about the potential risks to life and limb, ranging from dysentery to plague and fevers, and John Sanderson – a ‘factor’ (i.e. representative) and clerk of the Levant Company between the years 1584 and 1602 – was no exception. We will encounter Sanderson and his travels in the Levant later in this Element as well, but for now, we will focus on the contribution of illnesses to accidents, calamities, and ill fortunes that Sanderson recorded not only for posterity but possibly first and foremost for himself.

Sanderson first travelled to Istanbul in 1584 as a young man of twenty-four. This was a time when the English trade and diplomatic relations with the Ottoman sultan were still in their infancy – syndicate trading with the Ottomans was chartered on 11 September 1581 (Reference MatherMather 2009; Reference WoodWood 1964). Sanderson has left us an unusually strong paper trail of personal writings and documents, all rich sources for the social and cultural historian of mobility and travel writing alike. His writings comprise not only letters and correspondence but also some accounts and notes in a commonplace book fashion. In addition to this material and within the pages of this same ‘commonplace book’, Sanderson wrote both a short autobiography and a manuscript account of his travels and dealings in the Levant; long extracts of the manuscript were later published in Samuel Purchas’ famous collection of travel narratives, the monumental Purchas His Pilgrimes in 1625. Unusually for Purchas’ sources, we can compare the versions of Sanderson’s accounts in manuscript and print and interpret the varied meanings of what was edited, what was excised, and what was left for the eyes of not the many but the few (Reference Holmberg, Gelléri and WillieHolmberg 2021c).

In the short autobiographical section of his manuscript (entitled ‘a record of the birthe and fortunes of John Sanderson, alias Bedic’), Sanderson recorded both his ‘censures’ and the many trials of his life, a practice familiar to many a Puritan and Presbyterian author (Reference Capp, Berner and UnderwoodCapp 2019; Reference LynchLynch 2012). However, at least at face value, Sanderson’s ‘record’ was more focused on life-threatening illnesses and escapes from the claws of death than on spiritual trials, with self-chastisement and efforts at reform added only later as comments. Sanderson writes that he was a sickly child from infancy, whose schoolmasters beat him up regularly, leaving both visible and invisible scars (Reference SandersonSanderson 1931, pp. 1–2). Sanderson’s practice of naming his ill-behaved family members, supposedly badly behaved apprentices, and other wrongdoers hints that his account was not intended for print publication and that it was written from a very particular yet often elusive perspective. The practice of restricted manuscript publication and recording was not unheard of: authors often circulated their writings in manuscript to keep records of family events, accidents, births, and deaths, or to ensure their version of events was heard (Reference Marschke, Farr and RuggieroMarschke 2022).Footnote 10 Other people, be they family or colleagues, became foils for Sanderson. Like his many illnesses, they disrupted the flow of his life, some causing longer suffering and pain than others. One of the few positive descriptions of a living being in Sanderson’s text was of his horse, a ‘Babilonian’, which he remembers ‘would walke by me, licking my hand; stand still when I backed him; and kneele at my pleasure’ (Reference SandersonSanderson 1931, pp. 14–15).

After his arrival in the Levant, Sanderson’s illnesses punctuated the daily rhythms of trade and diplomacy that he probably considered too mundane or unnecessary to record in greater detail. Arriving in Istanbul in 1584, the ambassador William Harborne had made Sanderson the ‘maister of his howse’, where he, to his great grief, ‘remained in that sort six monethes’ and reported that during this time he ‘was daingerously sicke at one time, but sone recovered’ (3). More dangerously still, for the next eighteen months, Sanderson was sent to plague-ridden Cairo to manage the Turkey Company business. There he claims to have counted the deaths of at least ‘two hundred in a day at Cairo’, in addition to the many others who died at ‘Alexandria and at Rossetto’, which served the purpose of both reporting on the dangers of foreign lands, and perhaps his own bravery and providence guarding him against illness (4–5).Footnote 11 This kind of intelligence gathering about illness in foreign lands was expected from travellers, but in Sanderson’s life story, they take on the additional function of aiding his time-keeping by noting all memorable events and accidents during his stay. When separated by time and distance from home, travellers employed a great variety of methods of keeping and measuring time (Reference WilliamsWilliams 2022).

With all the risks involved in foreign travel, it was not uncommon for travel texts to paint the traveller as either exceptionally lucky, blessed, or tenacious to have escaped illness and epidemics throughout their travels, especially if these were long and took them far away from their homeland. Public-facing texts could also boast of such feats. Traveller Thomas Coryate wrote about his invincible health from India, where he would later die, saying that ‘in all my travels since I came out of England, I have enjoyed as sound a constitution of body, and firme health, as ever I did since I first drew this vitall ayre libertie, strength of limbs, agilitie of foot-manship’, not a mean feat trundling around the Levant, Persia, and India, which were considered notoriously unhealthy and dangerous for Western visitors (Coryate 1616, p. 4).Footnote 12

For Sanderson, the plagues of Cairo served to show his own fearlessness, allowing him to fashion himself as a Levant traveller of true grit and courage, and most of all, perhaps, being a man of experience and expertise to whom the less experienced could turn to for advice, also later in life. Sanderson reported seeing dead bodies daily, both lying on the streets and washing up on land, writing that nonetheless, he did not fear for his life, and that he ‘had no want of health, though the country is tediouse in respect of heate, dust, and flies’ (Reference SandersonSanderson 1931, p. 4). Such complaints were common among the early modern travellers, who feared that their bodies would struggle to acclimatise (Reference KuppermanKupperman 1984). Early modern health regimens strived for the stability and balance of ‘humours’, temperatures, and diets. Also of importance was the knowledgeable management of the six non-natural things, this is a specic early modern concept, not an element – air, food and drink, exercise and rest, sleep and wakefulness, excretion and retention, and passions of the mind – the foremost determinants of health and well-being that influenced human bodies from the outside. Complications of this management involved the adjustment and adaptation of all six elements to travellers’ individual complexions, their unique combinations of elemental and humoral qualities, and maintenance of their healthy balance (Reference GentilcoreGentilcore 2016; Reference StolbergStolberg 2011).

To document not only his tenacity but also his loyalty and trustworthiness, Sanderson remarked that neither pestilence nor shipwreck had prevented him from fully carrying out his duties, and that he had managed to avoid any extra losses to the Levant Company beyond some ‘provition of wood, wine, and houshold stufe’. It seems that one of the purposes of Sanderson’s text was to safeguard himself against accusations of corporate losses and perhaps prevent later lawsuits against him. If calamities such as the plague affected the Company’s trade, it was better to keep a record to which Sanderson could turn if needed. He also kept tally of other things: a list of the many troubles his apprentice caused him and a record of the (often sorry) fates of his enemies.Footnote 13 Similarities can be found in printed travel writing, albeit often in more candid and shrouded form: to defend, attack enemies, or seek compensation and retaliation. In the case of suffering and loss of life, a traveller naturally wanted to attract pity, compassion, and potential new patrons if illness struck them down.Footnote 14

Upon his arrival in Tripoli in present-day Lebanon, another life-threatening ‘illness event’ caught up with Sanderson, which he described as ‘beinge safely and in perfect health arived, after a while I fell greviously sick,’ a line very similar to other contemporary markings in diaries of ailing people. Sanderson also notes that he had been ‘sowinge a little gould in my doblett (for the next day I should have gone for Alepo, my horse hire paid for and aparell sent)’ (Reference ThorleySanderson, 1931, p. 5). Eerily, Sanderson had felt a ‘paulpable blowe one the left shoulder, which staied me [on] my asse’, when he had been riding one evening at the waterside together with a janissary, despite neither of them having seen where the blow had come from. Sanderson here paints a vivid scene where his illness strikes him down dramatically and out of the blue – as illnesses were often thought to do to their helpless sufferers, corresponding to the hand of God, striking down sinners or Saul on his way to Damascus.Footnote 15 The only difference concerns the lack of consequent spiritual transformation or conversion, and the eerie ambiguity about the supernatural nature of the event.

Upon arriving in his chambers, Sanderson ‘soncke downe’ on his lute, breaking it into pieces, informing us at the same time of his musical pursuits (Reference SandersonSanderson 1931, pp. 4–5). After recovering a little and creeping to the door, he managed to shout for help and some ‘aqua-vita’, after which he ‘threwe’ himself ‘thawart the bed’ (Reference SandersonSanderson 1931, pp. 4–5). The course and identity of Sanderson’s illness remains vague, but he describes being bedridden for quite some time. Like many of his fellow English travellers in the Levant, Sanderson suspected the cause might have been the ‘corrupted’ air of Tripoli that had infected not just himself but the forty to fifty Englishmen residing there at the time. The noxious and ‘miasmatic’ air was feared by many Levant Company men conducting trade in Syria and Aleppo, the trading hub connecting the overland routes between the Levant and India (Reference Linte and JonesLinte 2022; Reference PannellPannel 2017). Discussions of diseases having various causes, corrupting their stomachs or striking them down with fevers, lurked in the middle of their accounts.Footnote 16

Sanderson’s illness at this time was so severe that he claimed ‘everyone’ was convinced of his imminent death; indeed, a coffin had been made for him.Footnote 17 These kinds of claims are common in illness narratives: sometimes letters are sent back home to worried relatives before news arrives about the patients’ recovery, or the traveller arrives home much altered, correcting premature news of their death (Reference FrankFrank 1995).

Similar to other illness narratives, which punctuated the authors’ account of their lives, survival from illness abroad was not only a testament to a traveller’s tenacity but, especially when explained by providence, comparable to illnesses in other forms of life writing such as the spiritual autobiography, diary, family book, or memoir (Reference ThorleyThorley 2016, pp. 42–3). The providentialism of much of early modern life-writing provided a shared language in which to wrap stories of illness abroad and warn future travellers about all the possible dangers threatening unprepared novices and seasoned traders alike. These moments of ailing, death, and survival depicted in travellers’ writings illustrate their purpose not just as concerning their travels and pursuits of knowledge but also themselves, in all their humoral and emotional messiness. Hardship made life events memorable and not just profitable.Footnote 18

When explaining his slow recovery, jaundice, and constant swooning if forced to sit upright, Sanderson noted that he was eventually cured after being ill for four months. During his illness, he consumed barley porridge, chicken broth, and ‘stewed’ (boiled) prunes and apricots with their juice. These were common medications for ailments of the stomach, including dysentery or so-called ‘fluxes’, considered sufficiently gentle foods to be recommended to ailing patients, regardless of where in the world they were (Reference SandersonSanderson 1931, p. 5).Footnote 19 More well-known places for such notes were recipe books, in which (mostly) women recorded their own changing diets and cures and those of their loved ones, sometimes also noting changes in their scenery and cooking.Footnote 20 Travel writings rarely resemble recipe books, although it is not unheard of, as we can see here as well as in Fynes Moryson’s Itinerary, where the formerly ailing traveller recommends his own failed regimen to stay healthy during travels. Noticing connections between other forms like these helps us appreciate the richness of travel writing even more, and how it relied on the experience, expertise, and self-presentation of the traveller (Reference LeongLeong 2013; Reference RankinRankin 2016).

A final illness Sanderson suffered from in the Levant, during his stay in Aleppo, for which he recommended neither a simple cure nor a recipe, was ‘tenasmose’, a form of constipation which John Florio’s ‘Vocabolario Italiano and Ingelese’ defines as ‘a great desire to go often to the stool, and be able to do nothing’ (Reference FlorioFlorio 1611, p. 416). Using the opportunity to note some experiential knowledge, Sanderson interpreted his ‘tenasmose’ as being caused by his own refusal to take ‘phisique’, here probably meaning a light purgative, ‘according to the costome, to prevent sicknes’, perhaps unwisely going against received wisdom and health advice he had received.Footnote 21 He also mentioned that ambassador Edward Barton was at this time ‘sicke of a flux,’ perhaps connecting his own illness to the ambassador’s more serious dysentery. Sanderson seems to have thought that his ‘tenasmose’ was caused by something else entirely, which explained his refusal to accept the most common cure. Writing it down in his commonplace book might have served the purpose of warning both future travellers Sanderson might advise or show it to and, as my hunch is, keeping a record of his own ailments, perhaps anticipating their return one day.

Problems with the stomach such as Sanderson’s constipation, diarrhoeas, and especially the feared dysentery or ‘bloody flux’, were all well-known diseases for the English Levant travellers, with dysentery probably being the most feared and dangerous of them all. By the time Sanderson was writing his account, after his return to England, dysentery had claimed the life of Sanderson’s boss, ambassador Edward Barton, on 28 February 1598. It had also seriously plagued Thomas Roe’s residence in India, making several returns (Reference DasDas 2023). Several other unnamed men who left their homeland for the riches and opportunities offered by trade and colonisation were recorded in ship’s logs, trading company correspondence, and the margins of travel accounts, either according to their death or suffering from similar diseases (Reference HubbardHubbard 2021, pp. 172–3).

Other mobile English lives cut short by dysentery included traveller-author Fynes Moryson’s younger brother Henry Moryson in 1597, and traveller-author Thomas Coryate, who had earlier boasted of his invincible health but finally succumbed to the ‘flux’ during his travels in India in 1617. Sanderson might have feared the same fate as these men when he refused to be purged by the Venetian consul’s doctor, insisting that his problems were caused by something else than ‘the evell aire and change of waters, with the Turks spongie sower bread and rawe frutes’, showing his familiarity with contemporary fears about food, although he refused to believe they were the causes of his own illness:

But I ether toke it in a cupp of rosasolas the night before I departed frome the ambassiator, or else it was 400 d[uca]ts gould which I caried quilted in my purple velvett doblett, that all the way in ridinge beat uppon the raines of my backe. Be it howsoever, both strange, very painefull, and daingierouse the deseace was to me. Yet, I thanke God, in three monthes I was well recovered, and went to Siprus in the Navi Ragazona, John Douglas pilot, myselfe, G. Dorry[ng]ton, Alex. Harris, and Antony Marlo passingers.

Sanderson tried to make sense of his illness with the help of both prevailing medical knowledge and his own experience, claiming that he had contracted the disease from a glass of ‘rosasolas’ – or from his own money purse hitting him on the back.Footnote 22 As we have already seen elsewhere, with the incident on horseback, Sanderson was prone to magical thinking and thus could have also connected his illness to avarice. Be that as it may, Sanderson demonstrated in many passages how his obstinate views and sharp tongue got him into trouble with his closest colleagues and might thus have resisted listening to their advice as well (Reference Holmberg, Brock, van Meersbergen and SmithHolmberg 2021b; Reference HolmbergHolmberg 2022).

Reporting on contagious and dangerous illnesses was expected from travel writers of both public-facing and more privately circulating accounts. Travel books and manuscripts were supposed to gather intelligence, construct knowledge from many angles, and give aid to all those who sought to ‘plant’ themselves in newly established colonies and trading centres abroad. Instead of scaring off their readers, a public-facing traveller-author was expected to describe ‘the generall well-faring of the inhabitants’, counting the absence of endemic diseases among the natural resources and commodities of lands (Reference PalmerPalmer 1606, pp. 82–3). The more personal this knowledge was, the more useful it was considered, and here lies the wider cultural relevance of many such descriptions. More personally, Sanderson continued to advise and report on illness to his friends via his correspondence, while his autobiography had kept a more personal tally and record of the calamitous illnesses of his own life.Footnote 23 Due to the rarity of such embodied experiences among the vast majority of Englishmen of his times, Sanderson’s experience was of value not only to himself, helping to avoid and cure future ailments, but also to prevent and warn those without similar experiences.

Throughout his short autobiography, Sanderson threaded his life’s illnesses into his travels in the Levant and to all the other mischiefs and annoyances of his life. In his manuscript commonplace book, Sanderson’s perspective on both his own life and his illnesses was autobiographical, commemorative, and retrospective: he noted down his experiences after returning to England as further reference and a record of his life events. Back home, he attributed his recoveries to both God’s mercy and miraculous cures, but he left vague the causes of his illnesses, probably expecting to fill in some blanks later on when he had more access to expert knowledge and books. Even if Sanderson sometimes seemed to eschew prevailing medical knowledge, he also recorded recipes and remedies in his manuscript, even adding to an index to the end of his manuscript to help him recover information when needed. We have recently come to appreciate recipe books and family books as rich repositories of both biographical and autobiographical information and elements familiar from life writing elsewhere, and this appreciation also applies to Sanderson’s writings. The richness of Sanderson’s own travel archive is a testament to both his travels and how he wrote his life around his embodied experiences of mobility and the many sufferings these had caused him. In his account of his mobile life, his body literally took centre stage, expressing tenacity, providence, and bravery, and his hard-earned travel knowledge and experiences throughout, documenting both ailing and recovery along the way.

Suffering Heat, Cold, Hunger, and Thirst: Environment, the Senses, and the Traveller

Travellers were physically present in their texts, not only when their bodies were unwell, although these situations were the most dramatic and visible instances of their ‘embodiedness’ being on show. Travellers’ senses and emotions participated in recording their travel experiences, and as I argue here, contributed to the writing and fashioning of themselves in their texts, whether ailing or healthy. In situations when feeling hunger, thirst, or heat and cold, travellers were able to show (and even show off) their embodied experiences and hard-earned knowledge on how to survive. In this process, they used their own bodies both to construct and demonstrate their knowledge and express themselves as knowledge-builders; a process that often resembled later constructions of scholarly personae, a practice amongst scholars that has never really ceased but only changed shape and methods to become less embodied (Reference FeatherstoneFeatherstone 2019, pp. 1–19).

We can also notice the presence of the sensing and emoting traveller in several contexts, such as touching stones, smelling the air, and making judgments about foreign foods. The history of the senses and emotions has offered more tools for us to approach these episodes, but I argue that these tools work even better when combined with both social and cultural historical readings of the meanings such descriptions had in these accounts and, again, viewing them as writing the full (embodied) lives of the traveller (Reference SwannSwann 2018).

Until very recently, emotions and senses in travel writing were mainly explored for their ‘ethnographic’ functions: analysing the traveller’s representation and (eye-) witnessing of foreign lands, foreigners, and their emotional composition as part of their otherness or uncivility, or the sensory experiences of alterity produced by sounds, sights, and interpretations of the lower sensorium, the uncivility of foodways, or biting hostility of harsh climates (Reference BroomhallBroomhall 2016; Reference Ballantyne and BurtonBallantyne and Burton 2005; Reference DavisDavis 2002; Reference MurphyMurphy 2021). Contrastingly, my focus is on the travelling and mobile sensing and emoting persona of the traveller; the travellers’ ‘subjective’, yet very much cultural, experience of mobility. This type of experience is something that has often been claimed as either inaccessible to the historian, at least in any authentic or unfashioned form, or very rarely represented in the first place (Reference HolmbergHolmberg 2019; Reference OrdOrd 2008).

However, as with many phenomena studied in detail, the more a lens is focused, the more material is found. With more focus placed directly on their sensory experiences, early modern travellers suddenly appear in more sensory and emotional fullness than before, revealing themselves as not only eyewitnesses but also as ear-witnesses to sounds, as tasters of foods, as touchers of bodies and objects, and as smellers of both aromas and pungent smells, with diverse motives for writing such experiences down (Reference AgnewAgnew 2012; Reference MurphyMurphy 2021). Travellers come to the fore, touching, tasting, and otherwise feeling and sensing their surroundings and people and things they come across. This change can be explained not only as part of a move towards empirical witnessing in the early modern period and reporting on foreign lands in more systematic ways but also as having a long-standing tradition in classical rhetoric and narratives of pilgrimage, inviting emotional reactions from their readers and evoking their presence in the places they describe. Christian pilgrims sought to experience holy places both materially and virtually, imagining themselves partaking in the passion of Christ, visiting the Holy Sepulchre or faraway important sites and shrines, trying to taste the bitterness he had tasted and feel the sufferings he had felt.Footnote 24 Protestant travellers often struggled in trying to find a middle way, where they could visit the same sites though at the same time distancing themselves from Catholic practices (Reference O’DonnellO’Donnell 2009).

Sensory experiences often intersected with descriptions of illness, but also the daily practices of feeding and taking care of the body. Travellers such as Henry Blount and Fynes Moryson reported on their sensory experiences entangled with their withered bodies and corrupted stomachs. They tasted the waters of the Danube and perhaps the Nile, and failed to eat and consume anything else than dried meat because their bodies had been ravaged by grief and corrupted by foreign airs, waters, and places (Reference Din-KariukiDin-Kariuki 2023). Others, such as William Lithgow, viscerally reported how their bodies were assaulted by foreign bandits, unsuitable or unwholesome foods, or the sheer lack of victuals – the stress of such descriptions of sensory phenomena was more often on things that went wrong than experiences that were smooth and untroubled.Footnote 25 A recurring theme was the struggle with the change in climate and foods, and the missing of usual customs and routines, at least after the novelty of travelling had worn off. Underlying all this was the worry that residing in foreign lands could inevitably and unalterably change the traveller, or quite simply kill him.

As if trying to convince himself that the Levant had not changed him, the travelling Levant Company chaplain William Biddulph wrote to a friend that he was ‘weary of this uncomfortable Country’ but that

… although I am now many thousand miles distant from you, yet I have changed but the aire, I remaine still the same man, and of the same minde, according to that old verse, though spoken in another sense, Coelum, non animos mutant qui trans mare currant. That is, They that over the sea from place to place doe passe, Change but the aire, their minde is as it was.

Hiding beneath the surface of this wish was the troubling idea that residing for a long time in a foreign country could indeed change a man, both inside and out, both through a change in climate and through the new foods he was forced to consume (Reference EarleEarle 2014). It was feared that this might interfere not only with travellers’ sensory and emotional makeup but also change something deeper within.

Historians used to struggle with the ephemerality of sensory experience, worrying about emotions and senses in history (Reference RosenweinRosenwein 2002), and the ways they used to be studied either ahistorically or rigidly, or perhaps just too carelessly. However, nowadays we have a rich toolbox available to tease out the emotional and sensory experiences of the past, including the meanings of the whiffs of its smells (Reference DuganDugan 2011; Reference TullettTullett 2023). When studying the embodied and sensory experiences of travellers, employing these tools requires additional sensitivity to both mobility and the surrounding ephemerality of evidence: the awareness of the inescapable losses that have occurred regarding the props and paraphernalia of travel, and the difficulties of tying the experiences of singular travellers to the changing material contexts and objects, sceneries and landscapes, ships, roads, and inns, employing interdisciplinary approaches of not only sensory history but of material culture studies as well.Footnote 26 Exciting avenues are being explored via studies of the spatiality of travel, the practices of mobility on early modern waterways and roads, and logistics. The destinations and locales of mobility and cultural encounters have also been explored, extending the range of protagonists of travel from the elites to those who moved due to their profession, war, or exile (Reference MiduraMidura 2021). The next step should be to consider the experience of all this movement and the subsequent effects on culture, both to the people who moved and those who did not, and to read the discursive evidence in light of the surrounding materialities of travel. However, this does not mean forgetting about the intertextualities and self-fashioning functions of travel writing. The many rhetorical layers and mediations of sensory experiences continue to require sensitivity and nuance from readers, along with knowledgeability of genre and processes of writing; however, these are required for all writing in this period and should not prevent us from trying to explore these questions (Reference Din-KariukiDin-Kariuki 2023).

As in illness, the sensing body of the traveller most often emerges when either put in the ‘wrong’ climate for their humoral complexion or in a radically different environment, the effects of which were an enduring worry for early modern travellers, pilgrims, and colonisers alike (Reference KuppermanKupperman 1984). Senses seemed to be heightened and observations sharpened by being in a strange and unfamiliar environment (Reference Pettinger and YoungsPettinger and Youngs 2020). It was usually the crossing of (bodily) boundaries, the need to control and cure the body, or the added cost that put both bodies and their embodied experiences in starker relief in travel writings of the time. When put in a climate that was not thought to be amenable to health – unlike, say, a spa (Reference CorensCorens 2022) – where the climate was considered either too cold or too hot, the air too unhealthy and miasmatic to an individual traveller’s complexion, travellers had to ask themselves how they would need to conduct themselves to survive.

As a sign of these worries, early modern travellers collected and wrote down recipes to cure and rebalance their bodies, read suitable health advice in advance, and noted warning examples of people who had been startled or surprised by such sudden changes. Rumours spread that some people had even died due to extreme heat or cold, with their bodily fat melting in the burning sun or their noses falling off in the extreme cold (Reference KuppermanKupperman 1984). Merchant-traveller Peter Mundy, who we shall encounter again in the next section, recounted a story of being dangerously close to losing his fingers and nose due to extreme cold he suffered in Poland. This situation was all due to Mundy’s own behaviour: he had decided to try how little clothing one needed in a snowstorm – similar experiences abound of other travellers in the North, ranging from Italian priests to French doctors exploring Scandinavia, or from the well-documented and researched Britons tragically failing in their search for the North-West passage (Reference FullerFuller 2008; Reference MundyMundy 2010, pp. 97–8; Reference RaunioRaunio 2019). Travellers such as Mundy, Blount, and others used their own bodies to measure and test foreign lands, which resulted in more exciting narratives as well, unless things went wrong.

At the other end of the spectrum, hot climes were feared just as much as cold ones, even if English people of the time considered themselves as coming from the ‘north’ (Reference Rubiés, Morris-Reich and RupnowRubiés 2017). The long-suffering professional writer William Lithgow, the author of The Totall Discourse of Rare Adventures (1632 and its many previous editions) had truly travelled with his stomach empty, and his travels made him suffer even more for his art. Lithgow’s body not only had to endure gruelling torture at the hands of the Spanish Inquisition, but also other calamities and violations. He had a lot to say also about the dangerous foods, surroundings, and hot air of the Levant, which threatened the balance of his body so much that he kept himself emaciated to fight off corruptions and imbalance. At one point, Lithgow reports suffering so much from the heat in Alexandria that during the day, he and his French companions ‘did nought but in a low roome, besprinckle the water vpon our selues, and all the night lye on the top or platforme of the house, to haue the ayre,’ feelings familiar from contemporary summers scorched by climate change (Reference LithgowLithgow 1632, pp. 324–5).

Lithgow’s fear did not come out of nowhere: he had adopted Renaissance cultural fears about strange foods and diets along with climate theories that delineated the benefits of temperate climes. He claimed to have seen how his fellow travellers dropped like flies in the heat. Their misfortune related to their other poor life choices, with an undercurrent of social and moral commentary tainting his prose, warning his readers against excessive eating and drinking in foreign lands, lest they succumbed to ‘surfeiting’ and overheating their stomachs. Such was the terrible fate his German travel companions suffered on their journey from Jerusalem to Cairo, where they began drinking too much alcohol (Reference LithgowLithgow 1632, pp. 301–5).

The hot climate and the tropics were much feared and still little-known during the early age of European expansion: there were rumours about people who had died because, in their heat-induced delirium, also known as ‘calenture’, they had jumped off ships thinking that the vast seas were inviting green fields (Reference KuppermanKupperman 1984, pp. 172–3). The fear of heat was common in all parts of the world in which travellers ended up: it affected plans of colonisation, made colonisers worry about their failing crops, and caused travellers to fear literally melting away in the sun. The heat also made common diseases more dangerous and harder to cure, and the balancing act of maintaining the equilibrium of bodily fluids more vital: the wrong equilibrium might result in perishing or, at least, languishing.

The act of eating and drinking was another vital moment when the traveller’s sensing body participated in constructing their mobile self. Bodies involved in tasting, feeling, eating, and drinking were in intimate contact with foreign lands and customs in very corporeal ways and offered opportunities to manifest cultural preferences, civility, and good manners, and also to fashion the traveller as having accumulated such knowledge and experiences the hard way (Reference ForsdickForsdick 2019). Descriptions of food and drink drew boundaries between travellers and foreign phenomena, delineating danger and safety, and purity and danger, while also producing vital travel knowledge about what foods were safe to consume abroad, and how these differed from or bore similarities to those available at home (Reference WinchcombeWinchcombe 2022). In different climes, eating and drinking became a question of not only the themes we have already encountered in the context of illness: affordability, politeness, and hospitality; but they could also mean the difference between life and death. These issues were tied tangibly and viscerally to the body of the traveller, along with their morality, tenacity, class, and diverse tastes. Some travellers clung onto what they had been taught suited their bodies, lugging homely foods long distances, or trying to accommodate their tastes to the foods and diets abroad, while simultaneously being appropriately disgusted or horrified or complimentary towards local customs and foodways.

However, well-prepared in the beginning, travellers often had to eat what was available – no matter how rotten, hot, or dry, or even if the food was completely unsuited for their own humoral constitution and sensibility. Likewise, travellers often had to forego favourite drinks according to what was available or alternatively refrain from drinking altogether. Additionally, cultural prohibitions and health advice in the Levant were often in tension, as we saw in the account of Lithgow and his drinking travel companions, a fact that helped to accentuate Lithgow’s own moderate ways, saving him from both robbery and disease.

In addition to their direct connection to health and diet, descriptions of food and extra provisions (especially in the context of illness) carried with them more opportunities to express gratitude to benefactors encountered on the road. These instances can be read as writings of the self, especially the travelling ‘social’ self and its connections to others. Travellers thanked others in their texts for having provided money or loans, places to stay and recover, and for offering them nutritious and restorative substances. These details enable the texts to reach out beyond travels in the past, making efforts to shape the future, just as we have come to expect from diaries and memoirs that aimed to record their author’s perspective and viewpoint. The instances also offer information on travellers’ sensory experiences, along with their sociability and connections during travels, which went beyond the verification of their accounts. These included instances where foods and waters were tasted, scents and miasmas were smelled, and beds and other commodities were touched. Vision and hearing were also present.

Due to their suffering finances, travellers often had to compromise on either the quality or quantity of their food. Often, travellers described jumping on the chance of getting good, fresh food or recommending that successive travellers acquire provisions before certain stretches of their journey – as when entering hot territories such as the desert. Such episodes gave traveller-authors the opportunity not only to give cost-estimates of these provisions, recommendations, and warnings against certain foods or their poor quality, but also to thank especially hospitable hosts. Such an attitude also worked in their favour, fashioning themselves as courteous, grateful, and appreciative guests, with good connections to the English safety nets abroad. On the other side of the coin were laments about inadequate inns – or as was the case in the Levant, complaints about barely liveable Ottoman khans and rocky terrains, which had the capacity to disrupt sleep or irritate the stomachs of the most well-worn traveller – naturally risking one’s reputation as a sturdy and intrepid traveller who could endure almost anything. As we already know, travel made the diet and the air harder to balance; in addition, travel disrupted sleep and, whether due to constant travel or heat, could make the body of the traveller even more permeable to disease, and allow it to absorb noxious humours, pestilential air, and sub-par victuals (Reference EarleEarle 2014). Recording edibles, curatives, drinks, and other sustenance available served the purpose of not only knowledge-building, but these representations also constructed a story of the travellers’ adaptability, tenacity, and sometimes courage when confronted with strangeness, deficiency, or scarcity, all the while recording their sensory engagements with foreign lands.

Touching and Tasting the Holy Land: John Sanderson’s Journey to Jerusalem

Nested in John Sanderson’s already-mentioned commonplace book was a travel account about his years in the Levant, where he admitted he had once gotten so drunk with ‘rachie’ [raki] that a travel companion had to push his fingers down his throat to cause him to vomit. This incident forced Sanderson to thank his companion for saving his life in this way – and for his decision to never drink again, at least in such quantities. The crafty Sanderson also noted the names of everyone who became drunk that night, showing how closely drunkenness was tied to morality and masculinity, but kept this story to himself when he offered his writings to Samuel Purchas for wider publication in his famous Pilgrimes collection.

Sanderson’s material and sensory contact with the Levant did not end with illness, food, or drinking. He seemed to be an exceptionally sensory and tactile traveller, feeling his way through the Ottoman domains in the Holy Land, Greek islands, and the capital with its annoying Levant Company men. Protestants such as Sanderson (and Fynes Moryson before him) seemed to be both culturally and religiously drawn to the sights, sites, and sounds of the Levant, although they often sought to find new ways to engage with the places that had been earlier destinations of Christian pilgrimages.

Sanderson’s manuscript gives a sense that before his journey back to England in 1601, he had but one more thing to cross off his to-do list: a visit to Jerusalem. Sanderson departed from Istanbul on 14 May 1601 and arrived in Sidon on 3 June, where he joined a caravan of Jews heading to Jerusalem. Samuel Purchas later mentioned that his main reason for including Sanderson’s travel account in his Pilgrimes was ‘his pilgrim’s’ association with the Jews, something that would have been unusual and exotic in the contemporary climate of anti-Jewish sentiment in England. In Sidon, Sanderson struck up a deal with Jewish merchants and joined their caravan that was due to pass through the Holy Land to Jerusalem and back towards Aleppo. The generous Jews promised to make extra stops on the way to enable their Christian companion to visit the most revered places of his religion. On the journey, Sanderson mentions seeing Christians touching holy places, carving their names in stone. Seeming unsure of the correct way to conduct himself, Sanderson writes that he carved his own name only once, in a cave where Lazarus was supposed to have been buried, and that he also ‘washed [his] hands and head and dranke of the river [Jordan] in divers places’ (Reference SandersonSanderson 1931, p. 105, 113).