Studies have indicated that cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) plus treatment as usual for patients with schizophrenia have significant benefits on relapse and patient functioning (Reference Pilling, Bebbington and KuipersPilling et al, 2002; Reference Cormac, Jones and CampbellCormac et al, 2003). However, the application of CBT to psychotic disorders involving substance use has been evaluated very little, or where evaluations have been reported the findings have been limited by poor methodology (Reference Ley, Jeffery and McLarenLey et al, 2001). The current study evaluated the effectiveness of an individual and family-oriented CBT programme for chronic treatment-resistant psychosis combined with motivational intervention for substance use problems over an 18-month follow-up period. Preliminary findings on patient outcome from the treatment phase of the study have been reported already (Reference Barrowclough, Haddock and TarrierBarrowclough et al, 2001). The aim of the current study was to investigate whether the integrated programme of interventions had a beneficial effect on illness, substance use, carer and health economy outcomes over 18 months.

METHOD

This study was a randomised controlled assessor-blind clinical trial carried out in one centre over three sites, with patient and a nominated carer allocated to either an experimental intervention programme (CBT+motivational intervention) plus routine care or routine care alone. Outcome data were collected over 18 months.

Subjects

Subjects were entered into the trial as patient and carer pairs. Inclusion criteria were: an ICD–10 (World Health Organization, 1992) and DSM–IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or delusional disorder; a DSM–IV diagnosis of substance dependence or misuse; in contact with catchment-area-based mental health services in the north-west of England; aged between 18 and 65 years; and face-to-face contact with a carer for a minimum of 10 h per week. Patients were excluded if there was evidence of organic brain disease or learning disability. Potential subjects were identified by screening hospital records from the mental health units of three UK National Health Service (NHS) hospital trusts (Tameside & Glossop, Stockport and Oldham). Patients were approached first for consent and, after a complete description of the study, the written informed consent of those agreeing to participate was obtained. Carers then were approached and the same procedure followed. Only when both patient and carer consented were the patients accepted into the study. Patients and relatives were assessed on multiple measures (see below) before randomisation to one of the two arms of the trial. Individual patients were allocated by a third party with no affiliation to the study using a computer-generated randomisation list stratified for gender and three types of substance use (alcohol alone, drugs alone or drugs and alcohol).

INTERVENTIONS

Experimental intervention programme

The intervention has been described in detail already (Reference Barrowclough, Haddock and TarrierBarrowclough et al, 2000; Reference Haddock, Barrowclough, Moring and MorrisonHaddock et al, 2002). The intervention period was 9 months and consisted of modified versions of motivational intervention (based on Miller and Rollnick's approach) (Reference Miller and RollnickMiller & Rollnick, 1991), individual CBT (Reference Haddock, Tarrier, Tarrier, Wells and HaddockHaddock & Tarrier, 1998) and a family or carer intervention (Reference Barrowclough and TarrierBarrowclough & Tarrier, 1992). The individual intervention (CBT+motivational intervention) took place over approximately 29 sessions. The family intervention consisted of 10–16 sessions. The three therapeutic interventions were integrated and based on a thorough patient and carer formulation of the key difficulties relating to psychosis and substance use. The rationale for the treatment synthesis was based on the assumptions that: the majority of patients may be unmotivated to change their substance use at the outset; patients’ symptoms may be a factor in the maintenance of substance use but the substance use may exacerbate symptoms; and family stress may have a detrimental effect on patient functioning and outcomes. The aim of therapy was to increase the overall functioning of the patients and carers by reducing the impact and severity of the psychotic symptoms and substance use via cognitive–behavioural and motivational techniques that had been demonstrated previously to be effective for patients with psychosis and substance use problems and for their carers. Treatment was delivered by specially trained therapists meeting the minimum standard for the practice of behavioural and cognitive psychotherapies set by the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP). Treatment fidelity was monitored by experienced therapists and by rating sessions using the Cognitive Therapy Scale for Psychosis (Reference Haddock, Devane and BradshawHaddock et al, 2001). All patients also received routine care throughout the whole of the 18-month follow-up period. No attempt was made to standardise this, which generally consisted of case management and neuroleptic medication. In addition, all patients in the trial received an additional service from a Family Support Worker employed by a UK schizophrenia charitable association (Making Space). Their role was to provide practical support and advice to patients and carers.

Outcome measures

The assessments were conducted by independent assessors (two psychology graduate research assistants, N.S. and J.Q.). The assessors were blind to treatment allocation, with attempts to maintain their blindness by using separate rooms and administrative procedures for project staff, multiple coding of treatment allocation and requesting subjects not to disclose information about their treatment. Because the target patient group had multiple problems related to the symptoms of substance use and psychosis, the primary outcome for patients was change in the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Change in this outcome measure was chosen because we felt that overall improvements in the presenting symptoms and their functioning resulting from the interaction between psychosis and substance use would be reflected in changes on this measure. Secondary outcomes also were used, including measures of patient symptomatology (the Positive and Negative Syndrome Schedule, PANSS; Reference Kay, Fiszbein and OplerKay et al, 1988), social functioning (the Social Functioning Scale, SFS; Reference Birchwood, Smith and CochraneBirchwood et al, 1990) and patient substance use (timeline follow back, TLFB; Reference Sobell, Sobell, Litten and AllenSobell & Sobell, 1992). Patient outcome assessments were administered at four time points: pre-randomisation, immediately, post-intervention (9 months), at 12 months and at follow-up (18 months).

Two variables were computed for evaluating outcome on the TLFB: percentage of days abstinent from the most frequently used substance; and percentage of days abstinent from all substances. The most frequently used substance was identified from the Addiction Severity Index (Reference McLellan, Luborsky and WoodyMcLellan et al, 1980). The TFLB interviews were conducted every 3 months throughout the intervention. The concurrent validity of the TLFB had been established previously (Reference Barrowclough, Haddock and TarrierBarrowclough et al, 2001).

Finally, two methods of assessing the frequency and duration of relapse were used for relapses in the 2 years prior to intervention and during the study period: the number and duration of hospital admissions identified from hospital record systems; and the number and duration of exacerbations of symptoms lasting longer than 2 weeks and requiring a change in patient management (increased observation and/or medication change by clinical team as assessed from chart review). Where symptom exacerbation preceded hospitalisation only one relapse was recorded. For relapses that preceded study entry by more than 2 years, only the number of admissions was assessed. Record systems were searched by the two assessors who were blind to patient study allocation. Interrater reliability for number and duration of exacerbations was checked by comparing ratings for ten randomly selected subjects, and there was 100% agreement.

Interrater reliability of the clinician-rated assessments for this study was good and has been reported previously (Reference Barrowclough, Haddock and TarrierBarrowclough et al, 2001) for the treatment outcome data. Reliability of the GAF and PANSS was assessed also at the 18-month follow-up point. Interrater agreement for the GAF, based on agreement between the two raters on ten independent assessments, was good (interrater correlation coefficient=0.65). Interrater reliability of the PANSS, based on the percentage agreement on exact or one-point different rater scores from five audiotaped interviews, was also good for each PANSS sub-scale (PANSS positive=83.3%; PANSS negative=96.7%; PANSS general=98.7%).

Carer outcomes

Data on carer functioning were collected at baseline and at 9 and 12 months. Expressed emotion was assessed using the Camberwell Family Interview (CFI; Reference Leff and VaughanLeff & Vaughan, 1985) prior to randomisation. These data were only collected at baseline. The 28-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ; Reference Goldberg and WilliamsGoldberg & Williams, 1988) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Reference Beck, Ward and MendelsonBeck et al, 1961) were used to assess general psychopathology in carers, and the psychosocial needs of carers were assessed using the Relatives Cardinal Needs Schedule (RCNS; Reference Barrowclough, Marshall and LockwoodBarrowclough et al, 1998). In addition, the burden and distress scales of the Social Behaviour Assessment Schedule (SBAS; Reference Platt, Weyman and HirschPlatt et al, 1980) were completed by carers.

Economic outcomes

The principal objective of the economic analysis was to assess the relative costeffectiveness of the CBT+motivational intervention in comparison with routine care alone. The analysis was undertaken from a societal perspective to evaluate the impact of the treatment on a number of different parties, including patients, the NHS, other providers of care and the wider economy.

Direct health care costs were obtained by applying an appropriate unit cost to each recorded consultation, contact or episode of care. Data on secondary health care utilisation were obtained from the patient's medical records. Details of primary care and community-based services, direct non-health care costs (e.g. travel, child-care) and indirect costs (productivity losses) were obtained from patient self-report using an adapted version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (Reference Knapp and BeechamKnapp & Beecham, 1990).

Unit cost information was collected from the financial departments of the relevant agencies. Where local data were not available, these costs were supplemented by unit costs from national literature sources (e.g. Reference Netten, Dennet and KnightNetten et al, 1999), drug formularies (e.g. British Medical Association & Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 1999), statistical surveys and similar sources. The additional treatment costs for the treatment intervention were calculated using a cost per minute taken from the mid-point of the relevant 1998–1999 salary scales. The additional costs of non-face-to-face activities (e.g. writing up notes, supervision) were also included in the estimate of therapy costs. Costs are reported in net present value terms by discounting costs by the annual rate of 6%, as recommended by the UK Treasury. All costs are reported in 1998/1999 values of pound sterling.

RESULTS

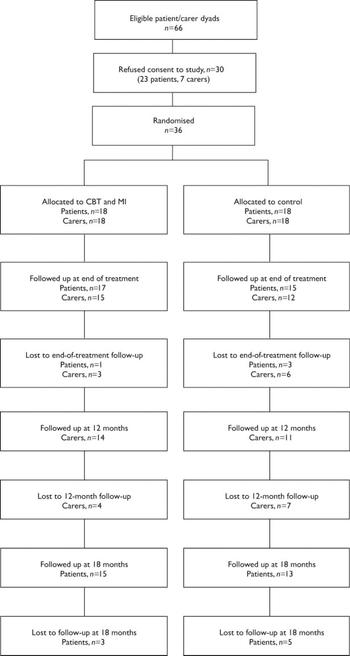

Sixty-six patient–carer pairs were identified as being eligible for the study and were invited to participate. Of these, 23 (35%) patients and 7 (11%) carers refused to take part. Patients who refused were significantly older, had a longer duration of illness dated from their first admission and had had fewer admissions in the past 3 years. Thirty-six patient–carer pairs took part in the study (see Fig. 1 for CONSORT diagram illustrating participant flow through the trial). There were no differences between the intervention and control groups on any measured demographic or illness history variables or in the distribution of drug and alcohol use. Nineteen of the patients used both drugs and alcohol and fifteen used only one substance (eleven used alcohol only, three used cannabis only and one patient used amphetamine only). Ten patients used multiple drugs, ten patients used cannabis with alcohol and one patient used alcohol with heroin. All patients scored above 5 (the cut-off score for clinically significant substance use problems in psychiatric populations) on either the Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (Reference Searles, Alterman and PurtillSearles et al, 1990) or the Drug Abuse Screening Test (Reference Staley and el-GuebalyStaley & el-Guebaly, 1990). Further details of the patient sample are described in Barrowclough et al (Reference Barrowclough, Haddock and Tarrier2001).

Fig. 1 A CONSORT diagram showing participant flow through the study. CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; MI, motivational intervention.

Of the carers, 27 were female and 9 male; the mean age was 51 years (s.d.=12.12). The majority (24, 66.6%) were parents, six (16.6%) were partners and the remainder consisted of one sibling, one grandparent, two landladies and two ex-partners. Thirty-two carers consented to the CFI administration and, of these, 20 (62%) were high-expressed-emotion status. There was no statistical difference (Fisher's exact test) in the distribution of high- and low-expressed-emotion carers between the groups (treatment group: 17 carers assessed, 11 (65%) high expressed emotion, 6 (35%) low expressed emotion; control group: 15 carers assessed, 9 (60%) high expressed emotion, 6 (40%) low expressed emotion). For all assessed carer variables there were no statistical or clinical differences between the groups at baseline.

There were three deaths during the 18-month follow-up period. All occurred during the first 9 months of the study: one was in the experimental group and two were in the control group. None was the result of suicide. At the 18-month follow-up, eight patients did not complete assessments (three from the treatment group and five from the control group). A total of nine carers were not available or refused consent to be assessed at 9 months (three under treatment and six controls, including carers of the deceased patients); and eleven carers were not available or refused consent to be assessed at 12 months (four under treatment and seven controls). Carers were not approached for assessment at 18 months.

Complete secondary medical records for the service outcome evaluation were available for all patients. Complete patient self-reports were available for 100%, 97%, 94%, 88% and 79% of the five follow-up (at 3, 6, 9, 12 and 18 months following entry to the study) assessment periods. Missing patient self-report data were imputed using the mean of the relevant treatment group.

Intervention participation

Carers and patients in the intervention group

Ten sessions were selected as the minimum ‘dose’ required to carry out both an individual and a family intervention of sufficient intensity to have an impact on patient outcomes. Five carers received less than this threshold for family intervention; the median number of sessions was 11, with a range of 1–20. Three patients received less than the threshold for individual CBT interventions; the median number of sessions was 22, with a range of 0–29.

Analyses

All analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. Patient deaths were treated as relapses, and subject attrition did not affect the analyses of relapse or secondary health economy outcomes because they were assessed from service records. Where scores from assessment measures deviated significantly from a normal distribution, log-transformed scores were used, and where distributions remained skewed or there was significant kurtosis, non-parametric statistics were employed.

Patient outcomes

Symptoms and functioning

Table 1 gives the scores for the treatment and control groups on the GAF and PANSS (actual means and standard deviations are given in the tables, but the text reports adjusted means and standard errors). To compare the effects between the groups on the 18-month outcome measures, analyses of covariance were used with the pretreatment scores entered as the covariate. The treatment group had significantly superior GAF scores at the 18-month follow-up (adjusted mean=61.68 and s.e.=3.32 v. adjusted mean=51.77 and s.e.=3.42; F={1,30}=4.26; P=0.048). The treatment group had reduced PANSS positive subscale scores over time, whereas the control group had a slight increase, although this difference was not significant (adjusted mean=12.93, and s.e.=4.23 v. adjusted mean=13.87 and s.e.=4.27; F={1,26}= 0.19, NS). At 18 months there was a significant advantage for the treatment group over the controls on the PANSS negative sub-scale (adjusted mean=10.27 and s.e.=2.25 v. adjusted mean=15.50 and s.e.=5.71; F={1,26}=9.87; P=0.004). There was no difference between the two groups for PANSS general or total sub-scale scores. There was a trend towards a significant difference in favour of the treatment group between SFS total scores at 18 months (adjusted mean=106.64 and s.e.=7.27 v. adjusted mean=100.23 and s.e.=10.02; F{1,25}=3.69; P=0.066).

Table 1 Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) and Positive and Negative Syndrome Schedule (PANSS) scores at baseline and 18 months (mean (s.d.))

| 0 months (n=18) | 18 months (n=17) | F | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAF | ||||

| CBT | 49.67 (11.96) | 60.12 (18.96) | 4.26 | 0.048 |

| Control | 53.33 (13.53) | 53.44 (13.00) | ||

| PANSS positive1 | ||||

| CBT | 16.50 (5.74) | 13.87 (4.27) | 0.19 | NS |

| Control | 15.22 (5.12) | 12.93 (4.23) | ||

| PANSS negative1 | ||||

| CBT | 13.22 (3.21) | 10.27 (2.25) | 9.87 | 0.004 |

| Control | 13.72 (3.69) | 15.5 (5.71) | ||

| PANSS general1 | ||||

| CBT | 31.61 (6.90) | 21.13 (6.39) | 0.26 | NS |

| Control | 33.44 (9.61) | 30.07 (8.17) | ||

| PANSS total1 | ||||

| CBT | 61.33 (10.04) | 52.20 (11.12) | 2.52 | NS |

| Control | 62.39 (15.89) | 58.50 (15.04) |

Missing patient symptom and functioning data

In order to assess the influence of missing data on the 18-month patient symptom and functioning results, the data on the GAF, PANSS and SFS were subject to further analysis using STATA version 6 for PC (STATACorp, 1997). This approach assumed that data were missing at random and involved calculation of adjustment weights to compensate for missing values. The probability of providing 18-month follow-up data was predicted using baseline, 9- and 12-month scores in an unweighted logistic regression. The reciprocal of this probability was then used as an adjustment (probability) weight using the logit command in STATA in a weighted logistic regression to estimate the treatment effects in the main analyses (Reference Everitt and PicklesEveritt & Pickles, 1999). This analysis revealed no differences in the overall significant difference between the two groups and hence the missing data are not thought to have caused any threat to the validity of the interpretation of the results.

Relapse

By 18 months, seven patients had had at least one relapse in the CBT group compared with twelve in the control group. There was a total of 11 relapses in the treatment group and 24 relapses in the control group. These differences were not statistically significant.

With regard to the total number of days relapsed between the two groups, there was numerical superiority of the treatment group at all time points, with a trend towards statistical significance at 18 months (median for the treatment group=0 (0–120), total days in exacerbation=424; median for the control group=29 (0–280), total days in exacerbation=1119; U=100.0; P=0.063).

Substance misuse

At all points but one during the trial the treatment group had a greater percentage of days abstinent relative to baseline than did the control group as assessed by the TLFB, although the differences were not statistically significant at any single time point.

Carer outcomes

Measures of carer psychopathology (BDI and GHQ scores) in both groups were fairly stable over the 12-month period and there were no differences between the groups. However, at 12 months there was a trend towards a statistically significant difference in change scores on the carer needs measure (RCNS: U=45.0, P=0.08), with the treatment group showing a reduction in needs while the control group remained stable. There was a similar trend for the SBAS objective burden change scores at 9 months (U=60.0, P=0.09) and both objective and subjective burden at 12 months (objective: U=42.0, P=0.06; subjective: U=44.5, P=0.08).

Economic outcomes

The results of the cost analysis are reported as mean values with standard deviations, and as mean differences in costs with 95% confidence intervals. Because costs were non-normally distributed (positively skewed), the robustness of the parametric assumptions concerning mean differences in costs was tested using non-parametric bootstrapping methods by performing 1000 replications of the original data (Reference Thompson and BarberThompson & Barber, 2000). Both the parametric confidence intervals and the bootstrap confidence intervals are reported. All the service outcome data were analysed using SPSS 10.0 and Microsoft Excel 2000. The bootstrap re-sampling was undertaken using STATA 7.0 (all on PC).

Table 2 provides details of resource use over the 18-month follow-up period. Patients given routine care alone had more in-patient days but fewer day hospital and day centre attendances. Table 3 reports the total costs and mean cost differences (a negative mean difference indicates a cost saving in favour of the intervention) for the treatment programme and routine care alone. Overall there were no significant differences in mean total costs between the treatment programme and routine care alone (–£1260; P=0.65). A further analysis was carried out by excluding the costs of the experimental treatment but there was still no significant difference in costs (–£3248; P=0.25).

Table 2 Resource use and unit cost estimates for treatment programme and routine care

| Service | Use of resources (mean (s.d.)) | Use of resources (median (IQR)) | Unit | Unit cost or range (£) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT (n=18) | TAU (n=18) | CBT (n=18) | TAU (n=18) | |||

| Therapy | ||||||

| Individual CBT | 19 (9.75) | N/A | 22 (11.25-28.25) | N/A | Session | 59/h |

| Family or carer intervention | 10.11 (5.88) | N/A | 11 (4.75-13.5) | N/A | Session | 59/h |

| Family support service, patient contact | 4.17 (2.57) | 8.28 (5.42) | 4 (1.75-6) | 7.5 (5-12.25) | Contact | 24/h |

| Family support service, carer contact | 7.17 (4.88) | 7.56 (6.76) | 5.5 (3-11.25) | 4.5 (2.75-12.25) | Contact | 24/h |

| Family support service non-access visit, patient | 1.06 (1.47) | 1.33 (2.74) | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-1.25) | Contact | 24/h |

| Family support service non-access visit, carer | 0.67 (0.69) | 0.72 (1.13) | 1 (0-1) | 0 (0-1.25) | Contact | 24/h |

| Hospital services | ||||||

| In-patient | 19.67 (37.34) | 45.61 (80.26) | 0 (0-23.25) | 3.5 (0-57) | Day | 92-143 |

| Out-patient | 7.22 (6.81) | 6.61 (7.25) | 4.5 (3-8.25) | 5 (3.25-7.25) | Attendance | 83-145 |

| Day patient | 9.06 (25.54) | 6.67 (20.12) | 0 (0-8.75) | 0 (0-4) | Attendance | 37-59 |

| Accident and emergency | 0.5 (1.04) | 0.5 (1.65) | 0 (0-0.25) | 0 (0-0) | Attendance | 43-45 |

| Primary care services | ||||||

| General practitioner (surgery visit) | 3.75 (4.59) | 3.53 (2.34) | 1.76 (0-6) | 3.55 (1.75-4.69) | Consultation | 13 |

| General practitioner (home visit) | 0 (0) | 0.48 (0.05) | 0 (0-0) | 0.05 (0-0.02) | Consultation | 39 |

| Practice nurse | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.07 (0.23) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0.02) | Consultation | 0 |

| Community/domiciliary services | ||||||

| Community psychiatric nurse | 20.97 (15.91) | 24.49 (14.03) | 21 (7.38-28.5) | 25.5 (14.03-33.66) | Contact | 21 |

| Social worker | 13.75 (17.20) | 9.14 (13.84) | 9 (0-23) | 3.87 (0-11.78) | Contact | 43 |

| Occupational therapist | 0.06 (0.24) | 0 (0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | Contact | 24 |

| Advocate | 0.17 (0.51) | 4.93 (12.31) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-6) | Contact | 43 |

| Home care worker | 0.17 (0.51) | 1.38 (5.65) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | Contact | 29 |

| Day services | ||||||

| Day centre/drop-in centre | 21.93 (29.61) | 15.39 (29.93) | 9.43 (0-37.25) | 5.5 (0-11.41) | Session | 17-21 |

| Drug and alcohol services | 0 (0) | 0.83 (2.57) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0.81) | Attendance | 56 |

| Medication | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Various | Various |

| Travel costs | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Various | Various |

Table 3 Mean costs (£) from baseline to 18-month follow-up for treatment programme and routine care

| Service | CBT (n=18) | TAU (n=18) | Mean difference (95% CI) CBT—TAU | Bias-corrected bootstrap (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (s.d.) | % of total cost | Mean (s.d.) | % of total cost | |||

| Therapy costs | ||||||

| Individual CBT | 1064(565) | 12.16 | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Family or carer intervention (FI) | 1114(692) | 12.73 | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Total therapy (CBT+FI) | 2178(1173) | 24.88 | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Family support costs | 370(147) | 4.23 | 560(444) | 5.59 | -190(-419 to 40) | (-445 to -3) |

| Hospital services | ||||||

| In-patient | 2227(4109) | 25.44 | 5605(10362) | 55.98 | -3378(-8824 to 2068) | (-8795 to 1124) |

| Out-patient | 969(907) | 11.07 | 853(1003) | 10.02 | 116(-532 to 764) | (-574 to 640) |

| Day hospital | 518(1466) | 5.92 | 380(1161) | 3.80 | 138(-758 to 1034) | (-580 to 1118) |

| Accident and emergency | 22(46) | 0.25 | 22(74) | 0.22 | 0(-42 to 41) | (-47 to 32) |

| Primary care services | ||||||

| General practitioner (surgery visit) | 48(59) | 0.55 | 45(30) | 0.45 | 3(-29 to 36) | (-24 to 38) |

| General practitioner (home visit) | 0(0) | 0.00 | 18(35) | 0.18 | -18(-36 to -1) | (-37 to -5) |

| Practice nurse | 0(2) | 0.00 | 1(2) | 0.01 | 0(-1 to 1) | (-1 to 1) |

| Community/domiciliary services | ||||||

| Community psychiatric nurses | 431(327) | 4.92 | 504(289) | 5.03 | -73(-282 to 136) | (-270 to 126) |

| Social worker | 545(722) | 6.23 | 384(586) | 3.84 | 161(-284 to 607) | (-261 to 603) |

| Occupational therapist | 1(6) | 0.01 | 0(0) | 0.00 | 1(-1 to 4) | (0 to 5) |

| Advocate | 5(15) | 0.06 | 143(357) | 1.43 | -138(-316 to 40) | (-367 to -28) |

| Home care worker | 0(0) | 0.00 | 40(164) | 0.40 | -40(-121 to 42) | (-134 to 0) |

| Day services | ||||||

| Day centre/drop-in centre | 384(486) | 4.16 | 256(496) | 2.56 | 108(-224 to 441) | (-201 to 392) |

| Drug and alcohol services | 0(0) | 0.00 | 44(138) | 0.44 | -44(-113 to 24) | (-132 to -6) |

| Medication | ||||||

| Prescribed medication | 941(1357) | 10.75 | 968(895) | 9.67 | -27(-806 to 752) | (-680 to 842) |

| Non-health care costs | ||||||

| Travel costs | 87(145) | 0.99 | 63(88) | 0.63 | 25(-57 to 106) | (-40 to 105) |

| Patient out-of-pocket expenditure | 0(0) | 0.00 | 15(49) | 0.15 | -15(-40 to 9) | (-44 to 0) |

| Productivity costs | 44(189) | 0.50 | 111(472) | 1.11 | -67(-310 to 177) | (-356 to 100) |

| Total costs (including therapy costs) | 8753(4804) | 10013(10717) | -1260(-6978 to 4459) | (-6957 to 3651) | ||

| Total costs (excluding therapy costs) | 6205(4580) | 9453(10773) | -3248(-8957 to 2460) | (-8846 to 1629) | ||

A series of one-way sensitivity analyses were undertaken to explore the impact on the base-case results of changing several of the underlying assumptions of the costing exercise (e.g. changing the discount rate; excluding the cost of appointments where the patient was not at home for family support; and including the cost of in-patient days’ leave arising during the overall duration of a patient's hospital). The results demonstrated that the base-case analysis was robust to the different assumptions employed in the costing analysis and the differences in costs remained non-significant.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Cost-effectiveness was evaluated by relating the differential cost per patient receiving each treatment to their differential effectiveness in terms of the primary clinical outcome (GAF). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated as the difference in mean cost divided by the difference in the mean GAF scores at the end of follow-up. A cost–acceptability curve was used to incorporate the uncertainty around the sample estimates of mean costs and outcomes and the uncertainty about the maximum or ceiling ICER that the decision-maker would consider acceptable (Reference Van Hout, Al and GordonVan Hout et al, 1994). The curve shows the probability that the data are consistent with a true cost-effectiveness ratio falling below any particular ceiling ratio, based on the observed size and variance of the differences in both the costs and effects in the trial (UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group, 1998; Reference Delaney, Wilson and RobertsDelaney et al, 2000).

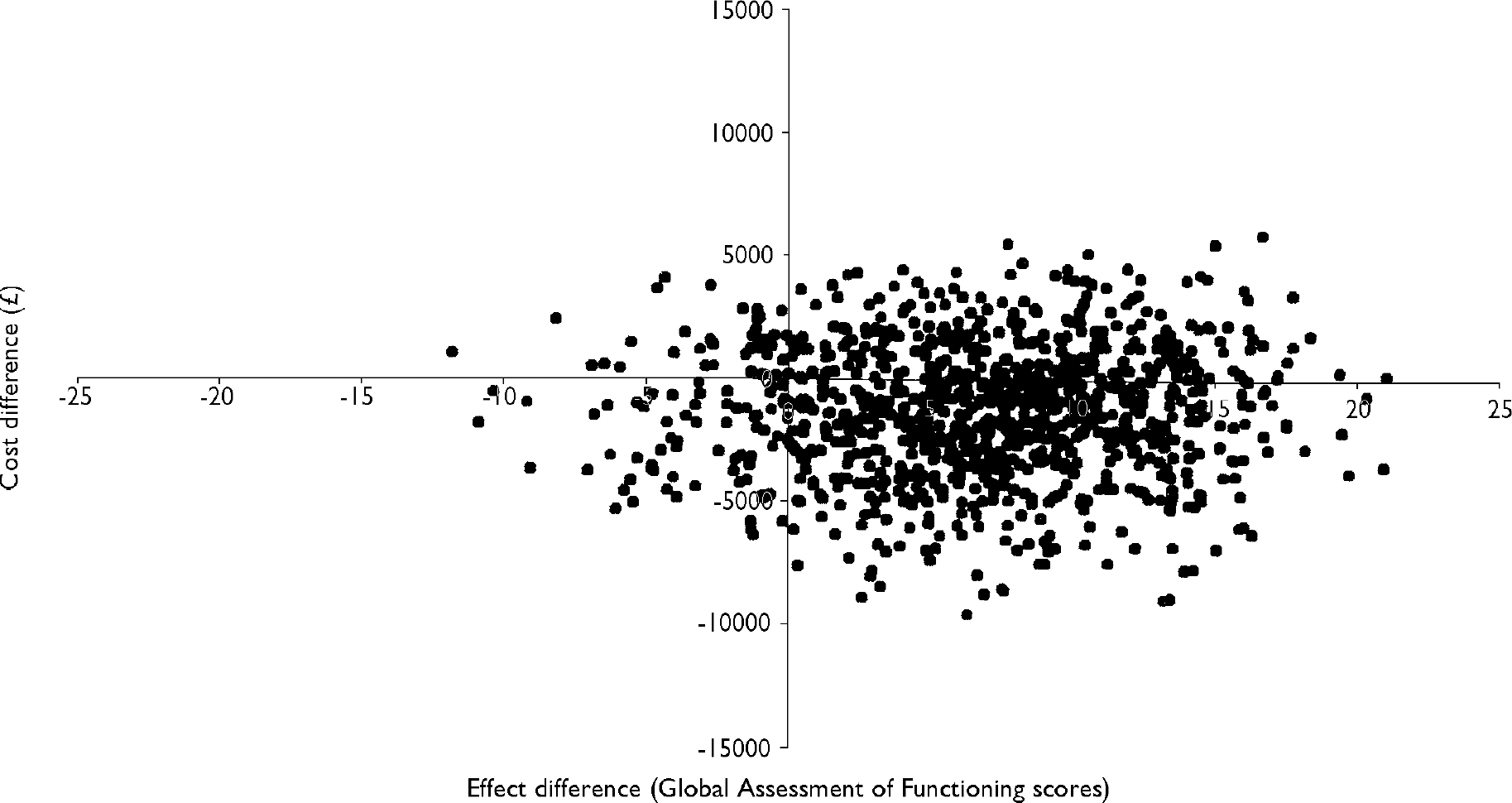

To reflect the uncertainty in the estimates of mean costs and effects, Fig. 2 presents a scatter plot of the mean differences in cost and GAF scores between the groups, estimated by repeated sampling as part of the bootstrapping exercise. The x-axis and y-axis divide the graph into four quadrants that represent the following scenarios for the treatment programme in comparison with routine care (clockwise from top right): (i) more effective and more costly; (ii) more effective and less costly; (iii) less effective and less costly; and (iv) less effective and more costly. The high concentration of points in quadrants (i) and (ii) indicates that the treatment programme appears more effective than routine care alone (although the scatter of points indicates that, in a small percentage of cases, there is a possibility that CBT will be more expensive and less effective than routine care alone). The wide dispersion of points above and below the x-axis, however, indicates that there is uncertainty about whether this apparent gain in outcome is achieved at a lower or higher cost. Clearly, if a gain in outcome is achieved at a higher cost, then the critical issue that determines whether the intervention is deemed cost-effective is how much (if any) the decision-maker is prepared to pay for an additional unit gain in health outcome.

Fig. 2 Scatter plot showing the mean differences in costs and in the primary outcome measure (Global Assessment of Functioning) from the trial data using 1000 bootstrap replicates (differences based on cognitive–behavioural therapy minus control).

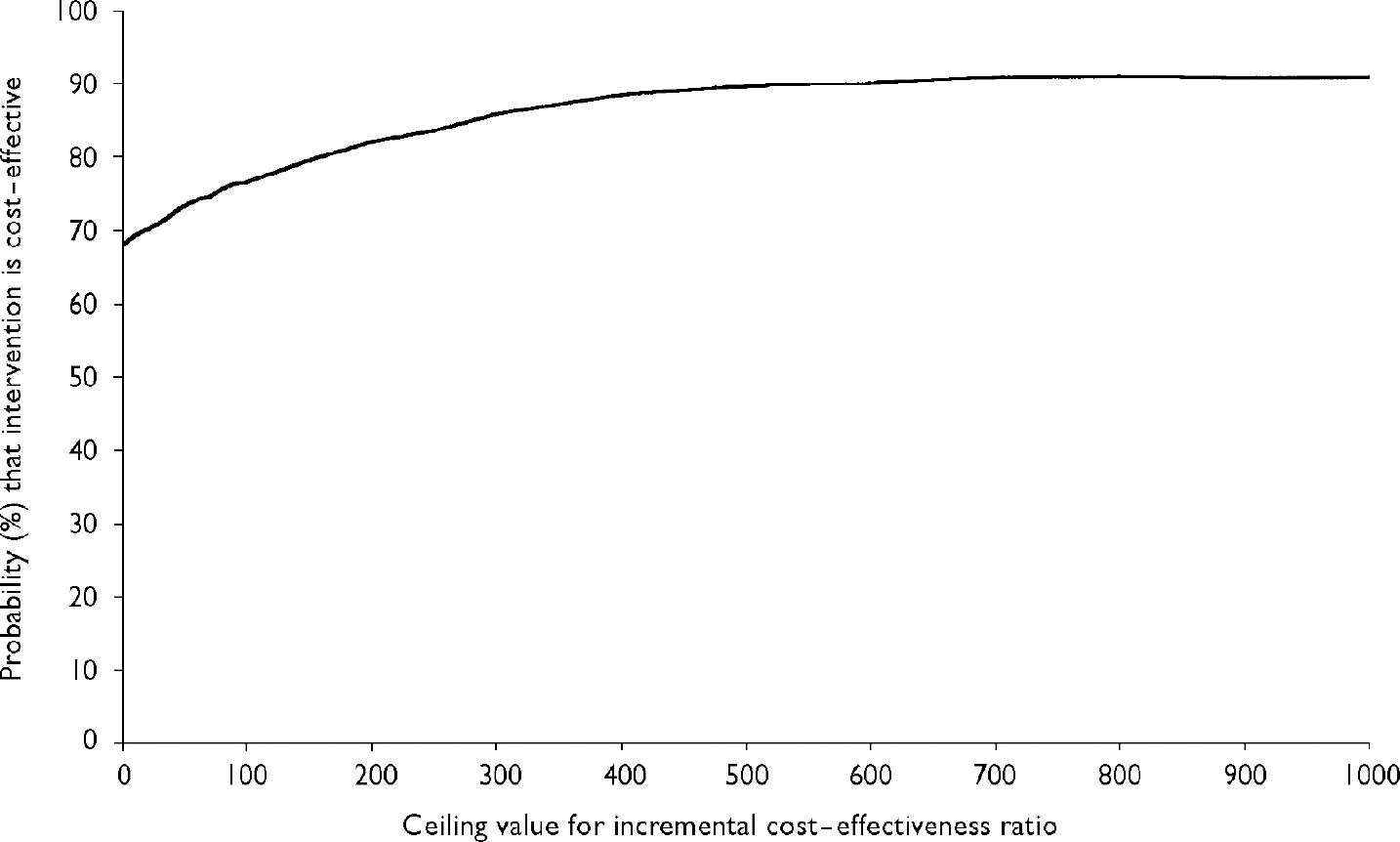

Using the bootstrapped data presented in Fig. 2, Fig. 3 presents the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve of the intervention. The curve indicates the probability of treatment being more cost-effective than the control for a range of potential maximum amounts (ceiling ratio) that a decision-maker is willing to pay for an additional point increase in the GAF. The x-axis shows a range of values for the ceiling ratio and the y-axis shows the probability that the data are consistent with a true cost-effectiveness ratio falling below these ceiling amounts.

Fig. 3 Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve showing the probability that the treatment programme is cost-effective in comparison with routine care (y-axis), as a function of a decision-maker's ceiling cost-effectiveness ratio (x-axis).

Figure 3 demonstrates that the probability of treatment being less costly than routine care (i.e. the probability of it being cost-effective when the decision-maker is unwilling to pay anything additional for an extra point increase in the GAF) is 69.3%. This exceeds the 50% decision rule, which is consistent with maximising expected health gain from limited resources (Reference ClaxtonClaxton, 1999). If the decision-maker is prepared to pay at least a £20 per point increase in the GAF, then the probability of the treatment programme being cost-effective increases to 70%. At a figure of £655 per point increase in the GAF, the probability rises to 90%.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge this is the first long-term follow-up of a randomised controlled evaluation of a specific and specifiable individual (as opposed to service-level) intervention for patients with dual diagnosis. The study demonstrated that a CBT-oriented, integrated psychosis and substance use intervention resulted in significant improvements in patient functioning when compared with routine treatment, and that these benefits persisted for treated patients up to an 18-month follow-up.

Global functioning and symptom outcomes

Specific benefits were found on global functioning and this was consistent with findings at the end of the treatment phase (9 months). Average improvement on GAF scores for the intervention group was 22.5%, compared with no change for the control group. Advantages for negative symptoms also were found for the experimental group at 18 months, consistent with those found at the end of treatment, suggesting a potentially robust outcome for these symptoms. Traditionally, carer interventions have emphasised increasing patient functioning and it is possible that integrating this with individual CBT had a specific impact on negative symptoms as carers were helped to reinforce and assist with patients’ strategies to increase functioning. However, the benefits found at 12 months for the experimental group for positive symptoms were not maintained at the 18-month follow-up. This is inconsistent with previous CBT trials where gains on positive symptoms generally have been maintained (see Reference Pilling, Bebbington and KuipersPilling et al, 2002). However, this trial differed from previous CBT trials in that the treatment integrated the positive symptom, carer and substance use approaches rather than focusing on positive symptom management alone. It is possible that positive symptoms in this group may need more prolonged intervention strategies to increase generalisation over time. However, it is also likely that the interaction between substance use and psychotic symptoms is an important consideration.

Although the treatment programme paid particular attention to integrating CBT for psychosis and substance use interventions, further development work is needed to clarify the nature of the interaction between psychosis and substance use in order to develop more refined treatment approaches. Anecdotal accounts by clinicians when conducting therapy indicated that this group had extremely complex and systematised psychotic symptoms that were clearly exacerbated by substance misuse. It is possible that the interaction between substance use and positive symptoms produces a type of psychopathology that is unique to this patient group and confirms earlier observations that specialist treatments are required that are designed to tackle both substance use and symptom outcomes. Larger sample sizes and more understanding of the psychopathology surrounding this interaction are warranted.

Carer outcomes

Although there were trends towards better personal outcomes for the carers in the experimental group, the integrated programme did not show statistical superiority on these measures. High rates of expressed emotion and general psychopathology in carers were observed, and more specific interventions may be necessary to bring about carer change. It should be noted that the carer intervention was relatively short and it is possible that a more intensive intervention is necessary.

Economic outcomes

The economic outcome analysis revealed that the experimental intervention was no more costly than routine treatment and that there was a high probability of it being cost-effective despite the high intensity of therapist contact. The control group had a much larger (although statistically non-significant) number of in-patient days in hospital, which is likely to have offset the higher therapy costs in the experimental group.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to the study that merit discussion. First, although based on catchment area, the sample size was small. However, the characteristics of the sample suggest that they are similar to other substance-misusing psychosis groups cited in the literature (Reference Mueser, Yarnold and LevinsonMueser et al, 1992). Second, our sample only included those patients who had at least 10 h of contact with a carer. It is difficult to know whether these results would generalise to patients living alone and without contact with their families. Furthermore, it is uncertain whether the treatment would be less or more effective when family stress is removed from the patient's immediate environment. It is possible that those patients who have maintained close family contact may have less severe problems than those who have not maintained contact. However, a comparison of the characteristics of our group with a matched sample of patients with schizophrenia and substance use who did not have significant carer contact showed that the groups did not differ on a range of variables (including symptom and illness severity and substance use variables), although they were significantly older than our sample (Reference Schofield, Quinn and HaddockSchofield et al, 2001). It is possible that this indicates that carer relationships of those patients who have psychosis and substance use problems may deteriorate over time and carer contact may become reduced. Third, the small sample size may have led to some potentially clinically significant results not reaching statistical significance. Finally, because the study design did not control for the additional staff time allocated to the experimental group we cannot conclude that the benefits attributed to therapy did not arise from additional contact per se. Clearly, further trials are required to identify the active and most important ingredients of successful therapy with this challenging client group.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ It is possible to integrate motivational intervention and cognitive–behavioural treatment (CBT) programmes for people with psychosis and substance use problems and their carers.

-

▪ People with schizophrenia and co-existing substance use show improved functioning from integrated CBT-oriented treatment programmes.

-

▪ The implementation of such programmes may not be significantly more expensive for services over the longer term than treatment as usual.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Small sample size.

-

▪ Intervention may be generalisable only to patients with dual diagnosis who have families.

-

▪ There was no control for the effect of extra therapeutic time.

Acknowledgements

Supported by West Pennine, Manchester and Stockport Health Authorities and. Tameside & Glossop NHS Trust R&D support funds; and Making Space, the. organisation for supporting carers and sufferers of mental illness. The. authors acknowledge the help of Sheila Dudley, Louise Burgess and Gina Evans. Professor Graham Dunn, of the Biostatistics Group, Manchester University, UK, is thanked for his assistance with the statistical analysis.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.