Introduction: ethnicity, an old-fashioned topic?

From the perspective of Iron Age archaeology, ethnicity has been as much a troublesome as an appealing topic. At the onset of archaeological research, ethnic studies were particularly widespread, probably encouraged by the need to justify a sense of common belonging for several national identities. Such paradigms engendered a profound rejection in later research, especially because of racialization and an ideological essentialism linked to authoritarian governments (Arnold Reference Arnold1992; Rebay-Salisbury Reference Rebay-Salisbury, Roberts and Vander Linden2011). Interest in ethnic identity, however, has never completely left the research agenda, perhaps because it allows archaeology to approach certain ethno-political realities that material studies often do not have the possibility of addressing.

In the 1990s, a revitalized interest in ethnicity burst forth, facing new epistemological strategies that removed completely racial and national-based dimensions. The influence of anthropological (Barth Reference Barth and Barth1969; Comaroff & Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1992) and sociological (De Vos Reference De Vos, Romanucci-Ross and De Vos1996; Jenkins Reference Jenkins1996; Smith Reference Smith2008) approaches, as well as their connection with Pierre Bourdieu's theory of practice (Reference Bourdieu2007), implied a radical change in the perception of ethnicity from an archaeological point of view. Instead of a permanent and monolithic perspective, ethnicity began to be understood as a dynamic and situational process, a ‘continuous becoming’ (Jenkins Reference Jenkins1996, 4) shaped by its own practice. The research focus was placed on the subjectification of ethnicity and its multiple layers, on the entanglement of different identities, and on the influence of colonial discourses in classical texts (Derks & Roymans Reference Roymans, Derks and Roymans2009; Fernández-Götz Reference Fernández-Götz2013; García Fernández Reference García Fernández2007; Roymans Reference Roymans2004). These new approaches not only provided academic functionality to an outdated topic, but also a new framework of study in which materiality was understood as an active part of identity building. Groundbreaking works linking ethnic identity and materiality (Hall Reference Hall1997; Jones Reference Jones1997; Wells Reference Wells1998) paved the way for later approaches that recovered and reappraised the potential of archaeology to identify dynamics of collective self-classification (Díaz-Andreu et al. Reference Díaz-Andreu, Lucy, Babic and Edwards2005; Fernández-Götz Reference Fernández-Götz2014; Mac Sweeney Reference Mac Sweeney2009).

Nevertheless, after a real archaeological boom, interest in ethnicity has started to decline in recent years. Although identity retains a central position in current archaeological research, ethnicity has lost its place in the front line. Several questions will be considered in this regard. In some ways, the evocative value of archaeology with regard to past identities might no longer be as strong as it was a couple of decades ago (Meskell Reference Meskell2002, 289), at least at a political-ideological level, despite some persisting examples from the far right and extreme nationalism (Arnold Reference Arnold2006a; Brophy Reference Brophy2018; Rodríguez-Temiño & Almansa-Sánchez Reference Rodríguez-Temiño and Almansa-Sánchez2021). Indeed, other dimensions of individual and collective identity, such as gender, queer or disability focuses (e.g. Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2023; Voss Reference Voss2021), probably understudied until the present (Mac Sweeney Reference Mac Sweeney2009, 102–3), have picked up the torch of identity studies of the past, probably as a consequence of new current interests. In this sense, and although it is still a matter of interest (Saccoccio & Vecchi Reference Saccoccio and Vecchi2022), ethnicity has taken a back seat, with some scholars even rejecting the term ‘ethnic’ in favour of new concepts (e.g. Steidl Reference Steidl2020), even within contexts and studies similar to those that, 15 years ago, were eagerly raising the banner of ethnicity.

The emergence of new interests can also be related with certain signs of fatigue in the archaeology of ethnicity. Committed to the study of emic perspectives and aware of the dynamism of identities, ethnic studies in archaeology have not always made remarkable progress in identifying strategies of self-classification. In some ways, the prophetic words of Meskell (Reference Meskell2002, 287) may have become true. In my opinion, this issue is not caused (or not as a primary reason) by a methodological or epistemological flaw, but mostly by insurmountable contextual constraints. This ‘new wave’ of archaeological ethnicity, based on post-colonialist and post-modernist claims, has managed to debug many interpretative issues, to avoid certain assumptions, and to present more an accurate approach to ethnicities of the past; still, issues such as the identification of what elements really embodied past ethnicities remain unbridgeable in a lot of archaeological contexts.

In this sense, the epistemological limit of several valuable proposals may already have been reached and, therefore, the focus of interest might have shifted to other questions with a greater research potential. Reher Díez (Reference Reher Díez, Moore and Armada2012, 657) has ironically highlighted that this problematic responds to the ‘introduction to ethnicity syndrome’, a tendency to explain how we should—and how we should not— understand ethnicity by compiling new epistemological advances and, paradoxically, dealing with material changes in a similar way to the classic ethnic studies. In fact, any archaeological study of ethnicity will tend to overestimate the reflection of the ethnic on materiality, as it is impossible to encompass the whole of ethnic expressions by studying objects.

According to these boundaries, the search for new focuses on political centrality and its value as ‘builder of identities’ (Fernández-Götz Reference Fernández-Götz2013; Fernández-Götz & Roymans Reference Fernández-Götz and Roymans2015; Voskos Reference Voskos2019) became very insightful for understanding and assessing the political dimensions of ethnicity. However, their scope is restricted to recognizing the political as a unifying factor of social identities, but it does not always explain which strategies were followed. In this regard, I found that it is much more fruitful to face our limits, put them on the table and be aware of how far we can go than sweeping ethnicity under the carpet. Archaeologists, as Laurent Olivier (Reference Olivier2020, 164) stated, are unable to distinguish any phenomenon other than the one we have been taught to look for. However, the solution is not ignoring these phenomena, but spotting the problem in our methodologies and exploring new ways of identifying them. Otherwise, we will overlook relevant issues in past societies just because we are not able to represent them as accurately as we previously believed.

In order to face this background, this work does not attempt to present a new methodological approach to material studies on ethnicity, nor to conduct an in-depth historiographical review of ethnic studies. Its purpose is humbler: to reflect on some issues of our current approaches to ethnicity and to offer new challenges and insights. In this sense, two core aspects will guide the analysis: the strategies of ‘otherization’ and classification of barbarian populations from the etic perspective of classical texts (with special emphasis on their perception of the Celtic), and the value of different expressions of political identity as a potential element of classification. In this way, the value of each ethnonym as a symbol of a specific collective identity should not be the main concern, as only a few archaeological records from the European Iron Age permit effective research in these terms. The goal is moving towards the identification and differentiation of general trends, especially regarding cultural, social and political dynamics, and facing an approach that brings together written and material sources. We may have to resign ourselves sometimes to identifying thicker strokes of the past, or even renounce tracing specific ethnicities. However, these thicker strokes will be more reliable, consistent with a phenomenological focus and capable of being further enhanced, if correlated with other archaeological and written evidence.

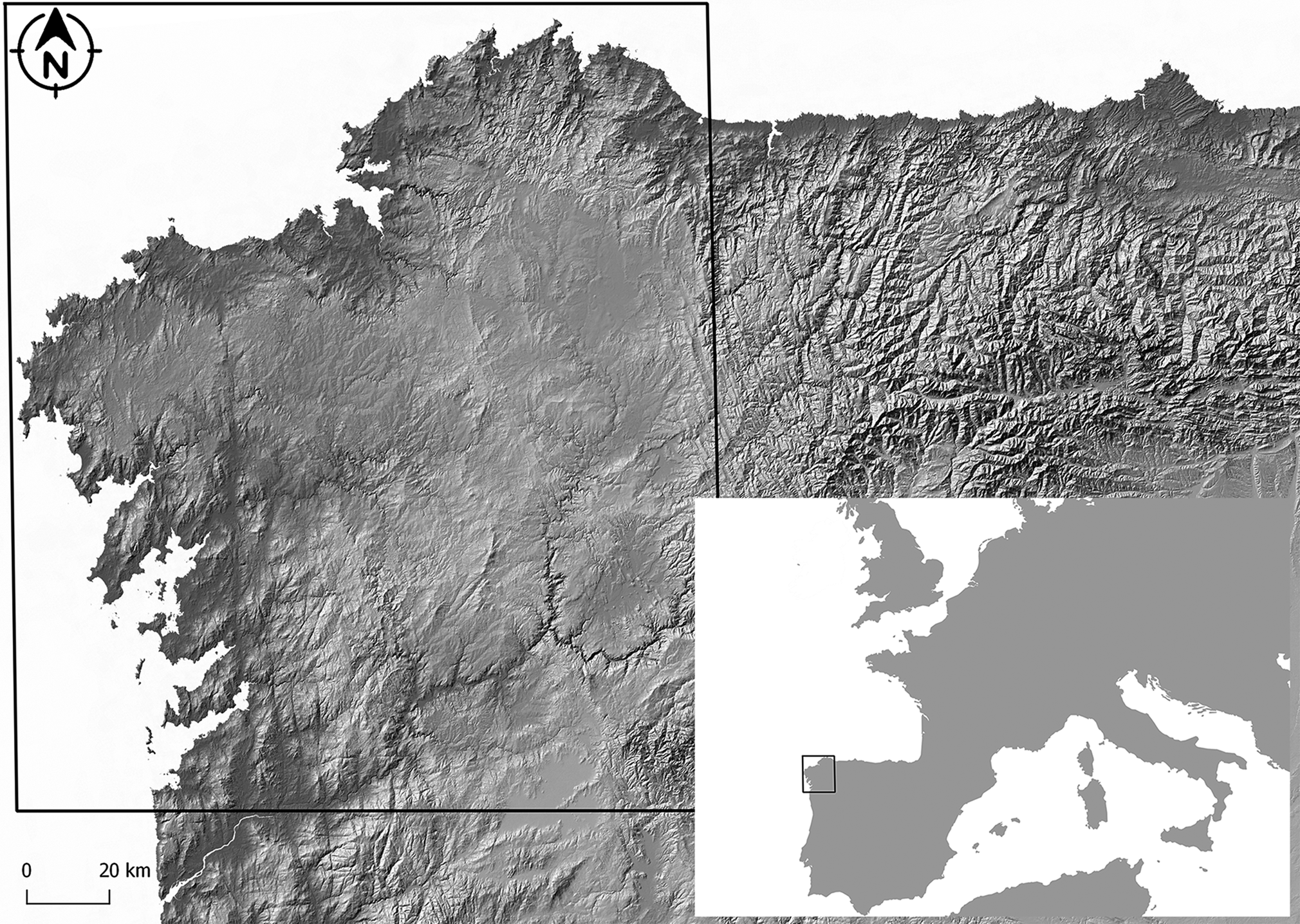

These approaches, under a holistic perspective, will be explored in a case study focused on the northwest of the Iberian peninsula (see Figure 1). Although this region has some examples of interesting works on ethnicity and identity (García Quintela Reference García Quintela2002; González García & Parcero-Oubiña Reference González García, Parcero-Oubiña and Sainero Sánchez2007), most of them have been focused towards the fierce ‘Celtic question’ (an exception may be González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal, Stoddart and Cifani2012). This context is an excellent point to begin to unfold an approach that moves beyond defining what is Celtic and what is not, focusing on exploring the archaeological and textual evidence that show identitarian differences between Iron Age communities. Therefore, based on the results of recent works focused on social and political dynamics (González-Álvarez Reference González-Álvarez2016; Nión-Álvarez Reference Nión-Álvarez2023a), we aim to correlate different phenomena and to explore their intersections in order to assess new insights on ethnicity and prehistoric self-classification.

Figure 1. Region of study.

Reassessing ethnicity: shall we reclaim etic views?

In 2013, Manuel Fernández-Götz (Reference Fernández-Götz2013, 118) suggested that ‘ethnicity can be part of our archaeological agendas, though in many cases we must recognize the limits to our approaches’. With the same ontological spirit, we may need to reflect on the scope of one of the main questions of interest in this new wave of archaeological ethnicity: the shift of the focus on identity analysis. One of its main core approaches stated that etic points of view cannot be understood as a transcription of the local construction of ethnicity. This issue, besides being difficult to refute, has placed archaeology in a relevant position when offering its own views about ethnicity as a means capable of transcending the private sphere of identities (Olivier Reference Olivier2020, 196–7). This interest on emic perspectives is directly related to the rise of post-colonial studies and the necessity to enhance the natives’ point of view, eventually considering etic views as a mere ‘transcription of colonialism’ (sensu Scott Reference Scott1990).

Nonetheless, neglecting etic perspectives may raise several problems when facing ethnicity. It is true that some classical writings may cause uncertainties in ethnic studies, not only when understanding the strategies of self-classification, but also in chronological terms: as Tom Moore (Reference Moore2011, 352–3) argues in the British case, not all the ethnicities mentioned in the texts represent a social context prior to the conquest, especially in late written sources. The Roman Empire, in fact, is an active agent in the modification of ethnic identity and its influence is not reduced to the written sphere. The case of the Lower Rhine Batavians is particularly illustrative: their collective identity is constructed after a process of ethnogenesis, in which local ethnicities (such as Eburones, Tencteri or Usipetes) were completely destroyed and dissolved as communities after the conquest (Roymans Reference Roymans, Fernández-Götz and Roymans2018). Then, the Roman Empire fuelled new regional identities through the reappropriation and restructuration of some cultural schemes, such as warrior ideals (Roymans Reference Roymans2004, 221). This is a relatively common processes in colonial contexts: old identities were erased if they resisted or did not fit into the new territorial scheme (Mamdami Reference Mamdami2001, 75) as well as eventually restructured based on certain old ethnic values… and, in the case of classical sources, these ‘new identities’ could have been recorded as ‘own expressions of identity’ in some cases.

In any case, this issue points more to the chronological vagueness of classical writings than to their value in differentiating social forms of the past. Ethnicity, whatever the context, is a phenomenon constructed from and for its social environment (Barth Reference Barth and Barth1969, 10–11). According to this situational approach of ethnicity (see Brumfield Reference Brumfield, Brumfield and Fox1994; Hodder Reference Hodder1982, 13–35), Nico Roymans (Reference Roymans2004, 1–5), regarding social constructions of ethnic identity, has suggested the influence of three different forms of expressions: those that define who you are, those that define how you show yourself, and those that others perceive about you. Accordingly, an etic perception of identity is an active and relevant part of the strategies of collective self-classification, since others will perceive you as a differentiated element when constructing group identities. Even if we acknowledge ethnicity as a multivocal phenomenon, intertwined with other identities (Jenkins Reference Jenkins1996, 5–6) or sheltered under different layers (James Reference James1999), ethnicity always has a relationship with a logic of opposition and differentiation.

In this sense, classical sources prove to be valuable for the study of ethnicity, even from critical positions (e.g. Moore Reference Moore2011, 344–5). Indeed, it is hard to think of an archaeology of protohistoric ethnicities without considering ancient authors, as we would have hardly any basis for differentiation (Hall Reference Hall2002, 24). However, literary evidence must not retain the same place that it held in the narratives prior to the post-colonial turn. Many uncertainties need to be considered, such as knowledge of world geography, the historical and socio-political dynamics, the background of each author, or their ideological prejudices (Fernández-Götz Reference Fernández-Götz2014, 18), in addition to the aforementioned chronological factor. Again, from a decolonial point of view, texts should also be reassessed as a source developed from a moral vantage point that subhumanizes and infantilizes the barbarian. The narrative of populations with different values from those of the classical world was constructed according to the ethos of Roman and Greek humanitas (Hingley Reference Hingley2005). The classical world is defined as the host of a universal morality (Kaminski-Jones & Kaminski-Jones Reference Kaminski-Jones and Kaminski-Jones2020, 8), claiming for itself the right to classify different practices in the spectrum of ‘inhuman’ and ‘civilized’ (Lampinen Reference Lampinen and Addey2021, 218–20) in order to justify its own ‘civilizing actions’ (see Strabo III.3.5 as a very enlightening example) and to exclude those who do not adopt Roman culture (Hingley Reference Hingley, Moore and Armada2012, 624). This is particularly obvious when describing Britons, Germans or Celts (Rankin Reference Rankin and Green2012, 30). These ethnicities were ‘othered’ from the set of values embodied by Roman humanitas, transmiting an idea of cultural superiority as a proselytizing strategy. It is worth remembering how Batavian auxilia branded the Britons who surrounded the Roman camps in northern Britain as ‘uncivilized’ (Derks Reference Derks, Derks and Roymans2009, 253).

Nevertheless, exposing the strategies of otherization of the barbarian should not diminish the value of classical sources (Woolf Reference Woolf, Derks and Roymans2009, 211), even though they were embedded in our current discourses (Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen, Graves-Brown, Jones and Gamble1996, 138–9). Being aware of these issues and exposing them may help to reflect about what kind of information we can extract from sources: a particularly pristine set of data about the etic perception of different Roman citizens regarding unconquered European peoples. Classical sources do not assess how barbarian people saw themselves as a collective, but how they should be classified according to the cultural context of the observer. Framed by clichés, stereotypes and preconceived ideas (elements that, on the other hand, nourish any ethnic classification, especially those assigned by colonial visions: Comaroff & Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1992, 56–8), classical sources may outline a rough and imprecise vision about barbarian communities. It is not my intention to explore how colonial dynamics transform the self-perception of subordinate communities, but to retrieve these data, even with their inherent flaws, as a potential source to differentiate past communities. It seems evident that classical sources should not be considered as a valid portrait of how barbarian societies saw themselves: the moral superiority of a colonial perspective pervades any attempt to offer a comprehensive vision of any kind of barbarian. However, classical sources hold a plethora of nuances which, when integrated into a global contextualization of relation between different phenomena, can help to refine this rough portrayal, and turn them into a useful source for the study of collective identities.

Celts in classical sources: archaeological debate, textual proxy?

Tackling the analysis of classical sources, I have considered refocusing a concept embroiled in controversy (Morse Reference Morse2005, 9): the Celts. Although ‘archaeological Celtism’ currently remains dormant—or, rather, latent—the Celtic question has generated a relentless debate during the twentieth century. However, in terms of ethnicity studies, the Celtic, among other major ethnic categories (in terms of Smith Reference Smith2008, 30–32), has been gradually abandoned, given its reduced value as an element of collective self-classification. This is not only a consequence of its ‘indiscriminate’ use, but also for its undefined value as an ethnonym, which can be traced back to its terminological genesis (Collis Reference Collis, Karl, Leskovar and Moser2012, 68–70).

For most Greek authors, the keltoi were not a uniform collective, but a label that might be applied to any barbarian, usually—but not always—located in northwest Europe (Dietler Reference Dietler1994, 586). In Roman times, Julius Caesar (Bellum Gallicum I.1) defined an accurate region from the Celts (in Latin, Gauls) in the area bounded by the rivers Garonne, Marne and Seine, noting their ethnic and geographic differences from the Aquitani and the Belgae. This description, however, dissolved in a mishmash of definitions that reflect a political and cultural bias (Pope Reference Pope2022, 22) and that do not represent a true uniform collective identity (Donnelly Reference Donnelly2015, 4). It is a logical narrative process, as most classical authors are not interested in setting a precise account of the true origin of the Celts, but rather in providing a piece of information in a broader narrative. Barbarian accounts are not the goal of authors such as Strabo, and his descriptions of these populations are often much briefer than others, like those of the Mediterranean peoples (Thollard Reference Thollard1987). In fact, the figure of barbarians is defined by several works of reference (in the case of the Celts, it relies mostly on the texts of Posidonius of Apamea: Freeman Reference Freeman2000, 24), as well as by a cluster of ideas and common places in narrative terms. Once established, narratives pivoted on this set of preconceived rough ideas (Rankin Reference Rankin and Green2012, 32). In the case of the Celts, the most common attributes used to define their characteristics usually allude to their potential as warriors, their physical impetus and their volatile, heroic and terrifying character (Rankin Reference Rankin and Green2012, 32). They were considered archaic and disorganized communities, structured in hierarchical societies with monarchies or warlords and on a regional basis, far away from the statalized societies of the Mediterranean (Rankin Reference Rankin1996, 298). In this sense, the texts seem to offer more a set of etic perceptions and preconceived ideas rather than an ethnic characterization.

As Rachel Pope stated (Reference Pope2022, 57), it is nonsensical to define the Celts as a cultural entity, as they have been depicted under very different attributes and social expressions. Leaving aside the possible existence of an earlier common root (an issue that exceeds our goals), its use as a common ethnonym is rather a footprint of cultural history (Feinman & Neitzel Reference Feinman and Neitzel2020) that should not be considered in contemporary ethnic studies. Indeed, its use tend to confuse rather than clarify, especially if it is applied to different regional identities with different and even contradictory attributes (Donnelly Reference Donnelly2015; Karl Reference Karl2012). In terms of self-classification, the Celtic identity is closer to J.D. Hill's ‘myth’ (Reference Hill, Hill and Cumberpatch1995, 45) than from a real common sense of belonging for European Iron Age peoples.

In this sense, Celt is not a valid ethnonym to represent Iron Age ethnicities, or not as we usually understand them, since it does not represent a specific ethnonym or any kind of shared identity. However, we shall not forget that this concept has a meaning for classical authors, and it is possible that this meaning could be useful for contemporary research. In essence, the term Celtic was used to define a specific way of being barbarian: whatever their origin or common sense of belonging, some people were labelled as Celt while many others were not. This not only means that they were different ways of being barbarian, but also that being a ‘barbarian Celt’ implied fulfilling a set of attitudes (some of them described above) that, in the eyes of classical authors, should receive a specific name. The Celts, in this sense, may not be a valid subject for studying ethnicities, but they are an interesting tool for hermeneutical analysis. Furthermore, if these data can be mapped and correlated with other phenomena, such as political identities (especially if they are consistent with the set of attitudes and meanings attached to the Celts), they may provide an interesting starting point for understanding different strategies of collective classification.

Objects and a holistic ethnicity

Irrespective of any epistemological focus, any material approach to ethnicity will face the same challenge: how to extract abstract, subjective and qualitative information from a ‘specific and quantitative’ material record. The ‘new wave’ of the archaeology of the ethnicity has bypassed such hurdles by breaking old historiographical dogmas, such as the equation ‘archaeological culture = ethnic group’ (Jones Reference Jones1997; Wells Reference Wells1998), following new approaches from different fields of study (e.g. Cohen Reference Cohen and Cohen1974; Hodder Reference Hodder1982; Shennan Reference Shennan and Shennan1989; Wiessner Reference Wiessner1983). According to that, a dispersion of objects should not be understood as a symptomatic element of collective identity (Fernández-Götz Reference Fernández-Götz2013, 120), shifting the focus to the identification of representative ‘ethnic markers’ that might be contextually changing according to collective practices (Fernández-Götz Reference Fernández-Götz2014, 42). Still, I find it as relevant to break with this old cultural-historical equation as to move the ethnic markers epistemologically from the object to the phenomenon. As their respective authors have suggested, the glass bracelets of the Batavians (Roymans & Verniers Reference Roymans and Verniers2010) or the stone boars of the Vettones (Ruiz Zapatero & Álvarez-Sanchís Reference Ruiz Zapatero and Álvarez-Sanchís2002) do not become ethnic markers because of their mere existence, but rather for their representative value linked with other cultural forms of expression that identify them as evocative elements of specific collective identities. This assertion, however, does not solve the challenges of extracting ethnic information from phenomena and archaeological data (Ruby Reference Ruby2006, 47). Can the location of a cultural pattern in a region be unrelated to ethnic identity? To what extent can we claim that one expression defines an ethnic identity in a deeper sense than another? And, if it does, is it possible to trace its reflection in materiality? Regarding ethnicity, material studies should assume deep uncertainties about the ambivalent nature of objects according to each context.

As Siân Jones (Reference Jones1997, 106–8) argued, there is no cultural equivalence between archaeological culture and ethnic identity, and, in case it arises, what is really relevant is weighing the representativeness of each set of objects in terms of structure and identity (Jones Reference Jones1997, 120). Let us give a trivial example: a wind instrument such as the bagpipe may be particularly representative of Scottish identity, but not all ethnic identities have a wind instrument that expresses their identity. However, it may be argued that bagpipes are also representative of Irish, Breton, Galician or Asturian people. In fact, the multivocal character of ethnicity makes it essential to avoid conclusions based on a single pattern and to turn to broader perspectives relating a multiplicity of phenomena.

Markers can indeed reach everyday activities that are not usually addressed: issues such as the choice of food or the cultural taboo of certain products may often be forgotten, but they are essential to represent individual and collective identities (Twiss Reference Twiss2012, 358). Even (unexpected) aspects such as genital mutilation were used as differentiating elements between very close ethnic groups, as between the Loikop and the Turkana from the Samburu District, Kenya (Larick Reference Larick1986, 278–9) or between the Philistines and the Canaanite of the Near Eastern Iron Age (Faust Reference Faust2015, 185).

In this sense, the problem is not whether ethnic markers are worthy, but to know which ones are truly representative or, as Clifford Geertz (Reference Geertz1973, 16) said, to differentiate between winks and twitches. From the archaeological point of view, Julian Thomas (Reference Thomas1999, 159) suggests the existence of ‘complex artifacts’ whose networks of significance are capable of offering more relevant information about collective identity. In this sense, the ethnic identity may have been better expressed in the way a group worship and bury their dead than in the distinctive decorative patterns of their pottery, even if the latter provides more convenient evidence from an archaeological perspective. This fact, however, adds a further problem to studying ethnicity from materiality: it is no longer a matter of knowing whether the objects preserve information about the ethnic identities of the past, but rather of recognizing which ones are truly representative in each context (Jones Reference Jones1997, 125–6). Accordingly, if ethnicity is a cross-cutting phenomenon that affects most social expressions, it can only be identified from a holistic approach, assessing which pieces of evidence may be representative of classification and distinction in each cultural context. To put it simply: if we consider the typological details that define a Scottish bagpipe, in combination with other representative iconographic elements (e.g. the thistle), symbolic local activities (e.g. rugby) or other consumption habits and strategies (e.g. the production and consumption of whiskey), it is possible to obtain a somewhat representative portrait that encompasses part of a collective identity. But, in any case, a representative portrait will be incomplete: much of the evidence is eminently non-material and other parts may be ambiguous on the record (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2003, 137). In this regard, I believe that we should take a step back: it may not be necessary to strive for an in-depth knowledge of a given ethnic group, but it is possible to map regional differences according to a certain set of phenomena.

These reflections are useful to reinforce the value of the etic perspective when analysing identities. Stereotypes and clichés, although vague, can help to trace distinctive patterns of ethnic identities (Comaroff & Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1992, 198). Indeed, ethnic identities can be particularly evident to the foreign; the problem arises when facing a strictly material-based focus. In this sense, we might need to recognize the value of etic views in order to differentiate collectives and use them as a milestone to be linked with material studies, even if we should assume that we have to give smaller steps forward or that part of our analysis will not be focused on truly emic expressions. In this sense, I found it more interesting to take a step back in terms of precision and to embrace ethnicity as a means to differentiate the populations of the past. A holistic approach, therefore, is essential: it is not a matter of collecting potential ethnic markers, but of differentiating key phenomena for collective identities on a supra-regional scale, tracing cultural intersections in issues such as cult expressions, burial patterns or, as will be explored in the following section, strategies of social organization and political identity.

Politics as an ethnic marker

The influence of politics on archaeologies of ethnicity has been particularly weak, even during the last decades. This might be due to the influence of multiculturalism or to the rise of studies focused on individual agency (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal, Stoddart and Cifani2012, 247), but I find it to be rooted in the traditional understanding of ethnicity. The first approach to ethnic and tribal identities was interpreted from a perspective of nineteenth-century colonial nationalism (Arnold Reference Assmann2006b) generating a ‘tribalized’ vision that does not accurately represent the ethnicities of the past (Moore Reference Moore2011, 354). Some approaches have often perceived ethnicity as a set of regional ornamentations, rites and symbols, but it is a phenomenon with a strong influence on a social and political scale (Brumfield Reference Brumfield, Brumfield and Fox1994), even if it is materialized through more ‘neutral’ expressions. Many approaches have focused on ‘identity negotiation’ from a multiculturalist perspective, undermining the influence of politics and power dynamics, but it is fair to mention that recent approaches have already considered these issues as structural elements of collective identities (e.g. Fernández-Götz & Roymans Reference Fernández-Götz and Roymans2015), following a trend that tries to re-engage politics and archaeology (Gardner Reference Gardner2018; Popa & Hanscam Reference Popa and Hanscam2019).

The link between ethnic identity and politics should not be surprising. As mentioned above, ethnicity requires an identification by opposition between one's own collective and the others, and its intersection with political identities shows its potential to be manipulated as a socio-political tool (Meskell Reference Meskell2002, 287). Indeed, several anthropological studies have pointed out that dynamics of ethnic classification are often raised after political actions: cases such as Southeast Asia (Scott Reference Scott2009, 243–4), the border areas of Ethiopia (Jedrej Reference Jedrej2004, 720) or the Highlands of Cameroon (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal, Stoddart and Cifani2012, 248) may provide insights in this regard. Of course, ethnicity is not exclusively built on social hierarchization or fragmentation processes, but socio-political dynamics often fuel strategies of self-classification, particularly in contexts involved in profound transformations. In this sense, bridging the gap between anthropological and archaeological ethnicity may be useful to understand how power relations, as multifaceted phenomena (Miller Reference Miller, Miller, Rowlands and Tilley1995, 68), have a critical influence on how culture is shaped and expressed. Although some ‘neutral’ or ‘ornamental’ expressions may be relevant to trace ethnic identities, elements such as religion (Assmann Reference Assmann2011) or politics (Leach Reference Leach1975), which are key in social-political terms, are decisive to differentiate social groups and ethnic identities.

Bringing the political factor into ethnic studies also allows understanding of how ethnicity changes at a spatial and chronological level. Ethnic dynamics, such as the Batavian case, would be impossible to understand without politics: not only the annihilation of the Eburones as an ethnic group, but also the ethnogenesis of the Batavian identity and its end after the lack of territorial control (Roymans Reference Roymans, Derks and Roymans2009). Recovering politics is essential to understand how ethnic identities are constructed and to acknowledge their dynamism, taking into account this close relationship between the ethnic and politics.

Bringing together archaeology, texts and politics in northwest Iberian ethnicities

Aiming to explore the relationship between ethnic identity, politics, classical sources and archaeology, we have chosen a case study in the northwest of the Iberian peninsula. This region has scarce references in classical texts, and it was considered as the finis terrae of the known world, far away from the main centres of classical culture (González García Reference González García2003, 23–4). Hence, we should not expect written sources, mostly focused on geographical data, to provide a wide variety of ethnic information.

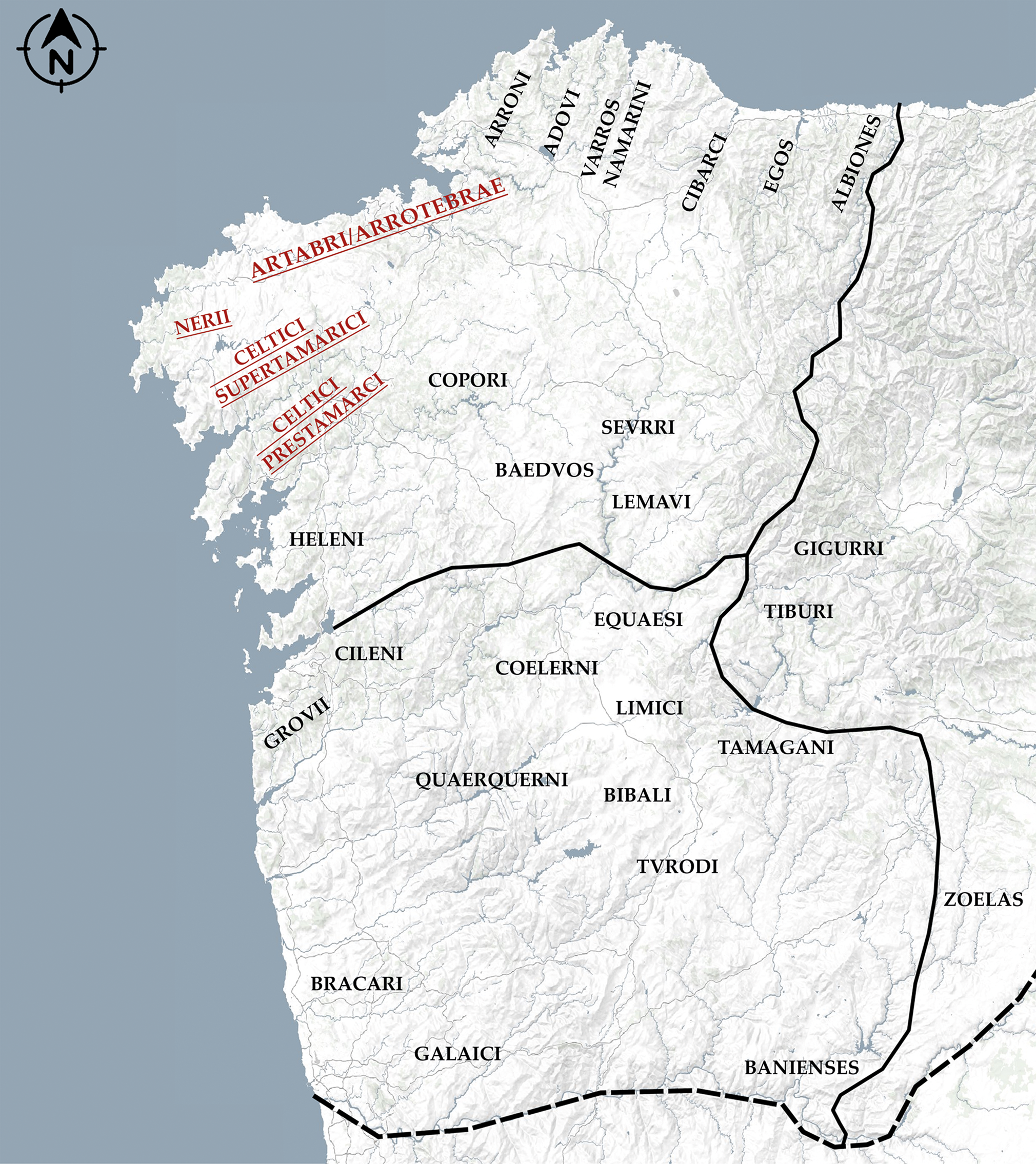

However, in this case, the volume of information is not as relevant as the subtle details that set differences at a regional scale. In the Naturalis historia, Pliny the Elder reported the existence of 62 populi and civitates across the three conventus in Gallaecia (HN III.28). It seems to be a particularly high number of populi (see Figure 2), especially considering the reduced area of Gallaecia in comparison with other regions: Gaul, which is 15 or 20 times larger, has a similar number of populi and civitates (Fernández-Götz Reference Fernández-Götz2014, 67). It is true that the use of the terms populi and civitates is not standardized in geopolitical terms (cf. Fernández-Götz Reference Fernández-Götz2014, 59–63) and it could be a loose use by Pliny in this context; in any case, this subject seems to emphasize an archaeologically acknowledged social and cultural fragmentation (González-Álvarez Reference González-Álvarez2011; González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal, Stoddart and Cifani2012; Nión-Álvarez Reference Olivier2023b). According to this context, Pliny (HN IV.111–112) identified several populi as Celtic (Prestamarci, Supertamarci and Nerii), consciously excluding the Copori and pointing out the Hellenic origin of Heleni and Grovii. Pomponius Mela (Chorographia III.12–13) also included the Artabrii as a Celtic collective, as Strabo also noted. The Greek geographer, in fact, hinted at the existence of Celtic peoples both in Artabrian and Nerian territories (Geographica III.3.5), reporting that their roots might come from the Celtic populations of the Turduli area (in the southwest of the Iberian peninsula).

Figure 2. Populi from northwest Iberia (those labelled as Celtic underlined and coloured).

These assessments of northwest Iberian populi do not seem to have considered the historical genesis or the collective self-classification of the peoples depicted. As mentioned above, these kinds of classifications were mostly based on a set of ideas and commonplaces about barbarian people. In this sense, the origin and ethnicity of the northwest Iberian populi were classified according to their own experience. The linguistic influence of two simultaneous language dynamics (both Lusitanian and Celtic: García Alonso Reference García Alonso2009, 164–5) may also have played a role in classifying these ethnic dynamics. In any case, the fact is that classical authors agreed on setting an ethnic differentiation that can be geographically and archaeologically contrasted with other phenomena.

Regarding the social and political dynamics of the northwest Iberian peninsula, a regional divergence has been recently noted, especially between coastal and inland communities (González García Reference González García2017, 302). On the coast, data show a social model oriented towards internal hierarchization and inequality between family units, collectives or groups. Among other aspects, this trend has been pointed out by the study of the domestic space, tracing the coexistence of large domestic compounds with single units (Nión-Álvarez Reference Nión-Álvarez2023a, 263–4) or the use and display of prestige goods (such as torques: Armada Pita & García-Vuelta Reference Armada Pita, García-Vuelta, Schwab, Milcent, Armbruster and Pernicka2018, 329). These dynamics have resulted in a fragmented landscape, with different socio-political small or medium units (Fábrega Álvarez Reference Fábrega Álvarez2005), but lacking entities capable of controlling the territory at a supra-local level (Nión-Álvarez Reference Nión-Álvarez2021, 369). This case may be similar to early medieval Ireland, with different clans and groups with varying degrees of power that struggled for territorial dominance in an unstable and competitive context (Woolf Reference Woolf, Berry and Laurence1998, 113–14).

In some specific areas, though, an advance in the dynamics of internal hierarchization has been hinted at. Dynamics of control of urban structuring have been identified with top-down processes and with the appearance of real oppida (Nión-Álvarez Reference Nión-Álvarez2023a, 267) or with active interaction in long-distance trade networks (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2006), creating a context in which greater socio-political entities may have developed.

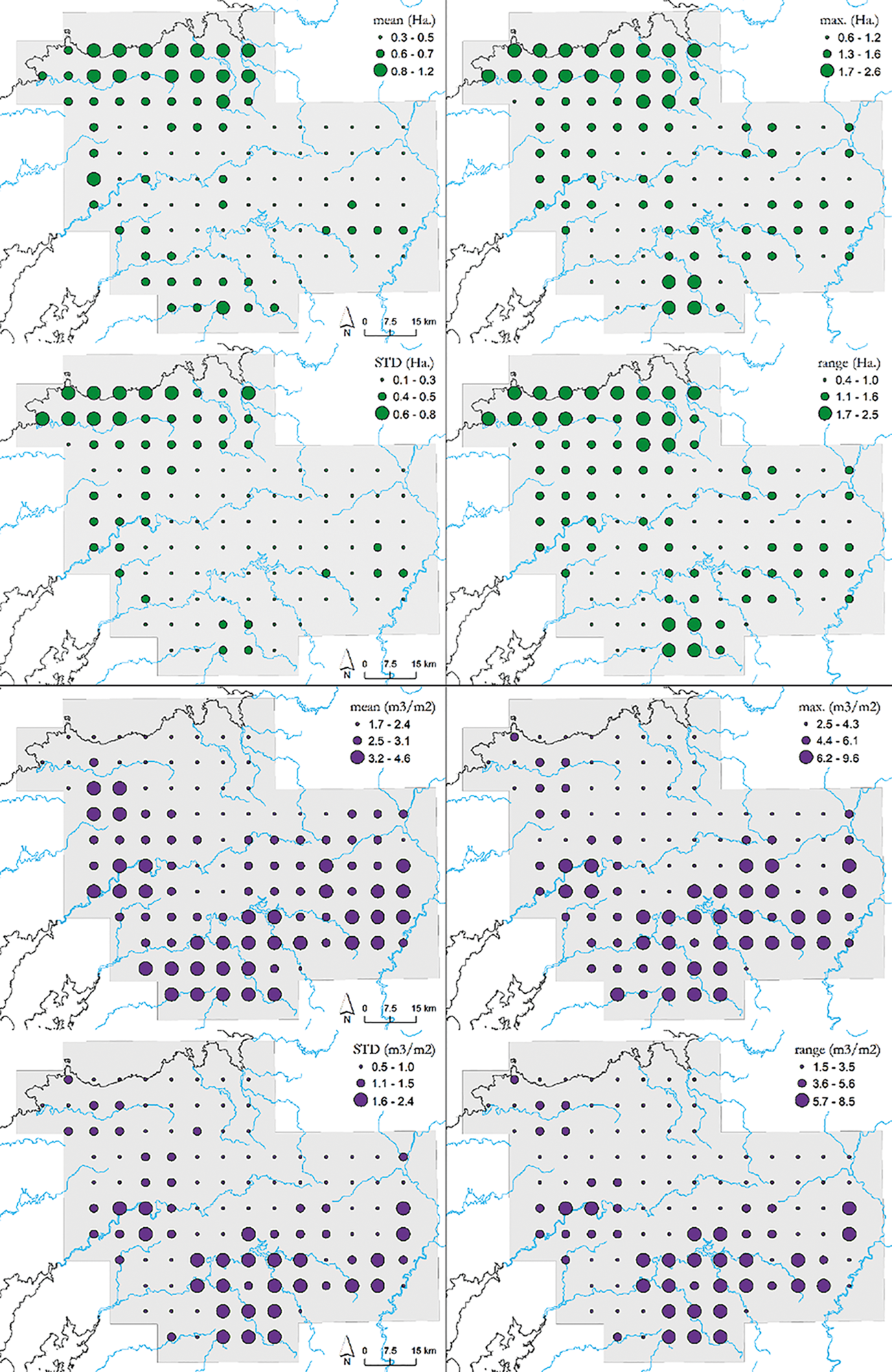

In contrast to these hierarchical and unequal dynamics, inland communities have been defined by a remarkable persistence of traditionalism and a high reluctance to social change, which has led them to be labelled as ‘deep rurals’ (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal, Stoddart and Cifani2012, 260–62; see also Figure 3), heterarchical (Moore & González-Álvarez Reference Moore, González-Álvarez, Thurston and Fernández-Götz2021) or undivided (Nión-Álvarez Reference Olivier2023b). Inland communities are characterized by significantly smaller hillforts (Parcero-Oubiña & Nión-Álvarez Reference Parcero-Oubiña and Nión-Álvarez2021, 10), multifunctional and with a remarkable homogeneity between different units within an unstructured settlement layout (Nión-Álvarez Reference Olivier2023b, 11). A profound reluctance to exchange networks and alien technologies (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal, Stoddart and Cifani2012, 261) is also noteworthy. These communities emphasize their conservative ethos, reject foreign practices and establish social dynamics based on contexts that ‘ignore inequality’ (González García et al. Reference González García, Parcero-Oubiña, Ayán-Vila, Moore and Armada2011), in which rulers see their power subjected to a perpetual social debt (Clastres Reference Clastres1981, 139). The scarce evidence of mobilization of workforce is exclusively oriented towards collective elements, such as the walls. Defensive systems were not only defensive, but also embodied collective identity (González-Álvarez Reference González-Álvarez2016, 355), and became a community monument (Haber Reference Haber2011, 26–7).

Figure 3. Northwest Iberian political identities. (Based on González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal, Stoddart and Cifani2012, 261).

Comparing these data with the classical sources, firstly, these different political identities show some consistent regional patterns. Dynamics of social inequality are mostly found in coastal areas, while inland regions show a greater resistance to change and the absence of hierarchies. Refining this issue a little more, a recent study, based on the strategies of monumentalization of the inhabited space (Parcero-Oubiña & Nión-Álvarez Reference Parcero-Oubiña and Nión-Álvarez2021), has both underlined social trends and mapped areas of influence (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Differences in social architecture. Area in sq. m, above; labour in earthworks and defences in sq. m/cu. m, below. (After Parcero-Oubiña & Nión-Álvarez Reference Parcero-Oubiña and Nión-Álvarez2021, 10–13).

Geographically, it is possible to trace a spatial correlation between coastal inequality dynamics and the populi labelled as Celtic (Artabri, Nerii, Prestamarci, Supertamarici). At the same time, inland populi (Copori) were not considered Celtic, which shows an ethnic differentiation that does not seem to be coincidental, but a conscious decision with robust support within the study of social dynamics and political identities. Classical sources pointed out a subtle difference between communities that corresponds, precisely, with the political identities previously discussed.

At this point, it is worth mentioning that the political identities found on the region of the Neri, Artabri, Prestamarci or Supertamarici express some common points with most of the values that classical texts associate with the Celtic world (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal, Stoddart and Cifani2012, 261): hierarchical social model, but disorganized and without states, social relations structured according to clientelist networks, warlike communities in which warfare and the ostentation of certain goods (and livestock) are key to obtaining prestige, etc. At the same time, those that are not labelled as Celtic did not replicate many of these values (less presence of prestige goods, rejection of unequal dynamics, etc.) that were usually linked to the Celts. In other words: the subtle nuances of past ethnicities outlined in classical sources are reflected in the study of political identities, and conclusions seem consistent with the latest archaeological research.

To what extent these phenomena are truly representative about ethnic identity could be discussed. As suggested above, political identity and social organization strategies are essential to define the boundaries of a specific community. Fragmentations, divisions or conquests (that is, politics) define what belongs to a community and develop a set of self-classification tools through many different elements (Assmann Reference Assmann2011). On the other hand, it is true that, from a quantitative perspective, there are only a few ‘markers’, even if they all stand on different intertwined phenomena, contexts and material evidence. This statement refers back to an earlier argument: it is not possible to dig deeper in terms of a specific ethnicity (our approach, indeed, encompasses a total of four different populi), but it could be possible to unveil different self-classification strategies. Both archaeological studies and classical sources pointed to a coincidence in the origin and location of those differences, which are representative of how a political community could have been defined. It may be only a few broad strokes now, but this methodology has the potential to provide a more comprehensive view if other representative phenomena of ethnic identity are added. Elements such as religious expressions, the consumption of particular goods, social decisions or power symbolization strategies may help to refine those strokes and to provide a more accurate portrait.

Conclusion

This paper has addressed an approach to the archaeology of ethnicity, exploring the potential of some under-studied phenomena for the study of collective identities. We have chosen to take a step back and focus on more general approaches, avoiding a detailed ethnic depiction, in order to provide a portrait perhaps less detailed, but that can be modelled with our current methods. In line with this, the relevance of political identity as a key element for defining the strategies of self-classification has been raised, stressing the critical role of the political in the structuring of ethnicity. At the same time, the value of the etic accounts (in the case of European Iron Age, based on classical sources) has been noted as a useful element for providing ethnic information. Although it cannot be understood as a valid criterion for acknowledging self-identification, the foreign perception of ethnic dynamics is relevant to construct and perceive some expressions of ethnic identities. Clichés and stereotypes are not a transcription of past realities, but they should not be ruled out either: they may provide key data to understand differences between barbarian communities and their ways of expressing social differences. It is crucial to face a holistic vision and to bridge the gap between different disciplines to provide more thorough visions of the dynamics of identity differences of past collectives.

This paper has explored these approaches in a case study in northwest Iberia, combining the study of political identities with written sources. In this case, the relevance of the etic perception in the sense of the ‘northwest Iberian Celticity’ has been explored, understanding it as an element of classification of different populi. In this case, the communities defined as Celtic were related to those with social dynamics of inequality and hierarchization, addressing different elements that meet some common attributes linked to the classical perception of the Celtic. At the same time, inland communities, reluctant to social change and prone to a more egalitarian ethos, are not labelled as Celtic, perhaps because their social expressions do not match the common values that classic authors usually link to Celtic peoples. It may be necessary to highlight that this study is not interested in tackling the Celtic question in terms of self-classification, but rather to use Celtic as a hermeneutic tool for analysing its classic perception and for exploring its potential for classifying ethnic groups from written sources.

In short, this paper has suggested new approaches to the study of ethnicities of the past, proposing and encouraging new elements that may help to revitalize the discipline. Introducing etic perception as a criterion for tracing differences between identities, as well as politics as a marker of self-classification strategy, can cross data that were hardly related before and offer new insights about the archaeology of ethnicity.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Tamara Barreiro Neira for reviewing and proofreading the text, and also the Editorial Board and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful and helpful comments.