I discussed above, especially in the Introduction and Chapter 2, some of the important links between Homer’s Odyssey – especially the Apologoi and, even more so, Odyssey 12 – and Parmenides’ poem. That analysis only scratched the surface, however, and in the beginning of this chapter I shall examine the relationship between these two poems at much greater length. Fortunately, we can pick up where earlier studies have left off.Footnote 1 If much of the literary analysis performed by scholars of Parmenides has focused on the Proem, this is partly because there is much to say.Footnote 2 What is important for our purposes at this stage is the manner in which the proem establishes a progressively more Odyssean ambience, creating a dramatic setting that, as it proceeds towards Fragment 2, evokes the relationship between Odysseus and Circe on Aeaea more and more specifically.

Havelock’s comparison begins with the claim that ‘books ten to twelve of the Odyssey (or a section approximating thereto)’ are Parmenides’ ‘central frame of reference’ in his poem.Footnote 3 This case can be made in terms of the proem’s language, imagery, characters, and dramatic scenarios, much of which is reminiscent of these books of the Odyssey.Footnote 4 Odysseus’ description of the land of the Laestrygonians is recycled nearly wholesale;Footnote 5 similarly, the ‘Daughters of the Sun’, the guardians of the Sun’s cattle on Thrinacia (Od. 12.131–36), are ‘converted from herdsmen into outriders’ who lead the chariot bearing the kouros (Fr. 1.9–10).Footnote 6 Collectively these images and intertextual echoes conjure a setting redolent of the ‘world’s end … a mysterious borne far off the beaten track, a region of mystery and peril but also of revelation’.Footnote 7

This in turn figures the kouros as a kind of Odysseus.Footnote 8 As the latter’s voyage in the Apologoi extends ‘beyond normal human latitudes’, so the former’s ‘journey is also an excursion beyond the bounds of accepted experience’ and seems ‘modeled on the bold enterprise of an epic hero, Odysseus’.Footnote 9 Odysseus’ encounters in the Apologoi have been seen to be patterned on the dynamics of the quest, which involves his arrival at an unknown place followed by a meeting with ‘someone who gives information or acts as a guide’ to help him complete the questFootnote 10 – all of which describes Parmenides’ kouros and his situation in Fragment 1 to perfection.

But not just anyone will act as his guide: the ‘foreground of Parmenides’ imagination is occupied by Circe on Aeaea’Footnote 11 – Circe, who is, after all, the Daughter of Helios, and Aeaea which is, after all, where ‘Dawn has her dancing floor and the sun rises’ (Od. 12.3–4).Footnote 12 The links connecting Circe and the unnamed goddess of Parmenides’ poem are rich and multifaceted.Footnote 13 Circe, ‘goddess endowed with dread speech’ (Od. 10.136 = Od. 11.8 = Od. 12.150), has the ability to ‘report verities of the mantic world and thus induce or at least indicate the hero’s’ further travel: ‘her helpful power is to … facilitate for him further stages of his symbolic journey’; Circe helps Odysseus ‘penetrate … to a deeply guarded area of the mythic geography’ where knowledge of incomparable magnitude is to be found.Footnote 14 In short, Circe, a female divinity with exceptionally privileged access to knowledge, guides the mortal male hero Odysseus on a journey which includes travel to a place where he will attain a level of profound knowledge: a description that could hardly better fit the dramatic scenario of fragments 1–8.Footnote 15

What is more, Circe has long been recognized as a vital turning point in Odysseus’ wanderings.Footnote 16 According to one popular analysis, the Nekuia serves as the pivot around which is wrapped the elaborate series of nested ring compositions that form the episodes of the Apologoi;Footnote 17 since it is from Circe’s isle that the trip departs and to Circe’s isle that it returns – and, as we have seen, on Circe’s orders, and only thanks to her guidance, that the trip is successfully undertaken – this makes Circe (in her instruction-giving mode, after her threat to Odysseus has been neutralized) a central figure anchoring the entire Apologoi.Footnote 18 There are a number of different facets to this point, and one can tease out at least four implications for Parmenides’ poem.

Most importantly, scholars have noted that the encounter with Circe divides the Apologoi into two parts. Before encountering Circe, Odysseus and his men wander; after, they sail with the direction and purposefulness that only her supernatural guidance makes possible.Footnote 19 Odysseus’ pre-Circean wanderings are epitomized by the calamitous episode bookended by encounters with Aeolus, king of the winds. Having taken their leave of his harmonious kingdom with all the winds but one held at bay for their convenience, Odysseus and his men have very nearly completed their journey in full (ὁδὸν ἐκτελέσαντες, Od. 10.41) – the hearth fires of home are even in sight! – when Odysseus’ men, mistrustful that the spoils Odysseus has collected along the way will be evenly distributed, open the sack holding the winds; once loosed, these promptly blow the ship all the way back to the shores of Aeolus’ floating island. (As scholars of Parmenides have on occasion noticed, the episode thus embodies the very paradigm of a backward-turning path.)Footnote 20 By contrast, from the moment they depart Circe’s island up until they reach Thrinacia – the full extent of the itinerary for which Circe gives her instructions – Odysseus and his men make clear, unambiguous, linear progress towards their final destination of Ithaca.

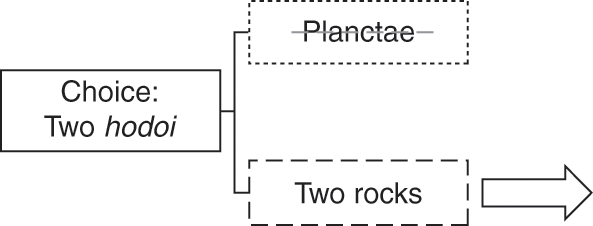

There is another way of putting the matter. Scholars have discerned a number of thematic and compositional patterns characterizing the relationship between different episodes in the Apologoi,Footnote 21 and careful consideration of these analyses suggests that Circe’s island serves as the mirror across which beckons the second, positive, goal-directed reflection of the first, wandering half of the Apologoi. Here, recourse to the graphs of various analysts of the Apologoi’s ring compositions are useful. A slightly modified form of Most’s graph in Figure 5.1 helps make the point vividly.Footnote 22

Figure 5.1 The structure of Odysseus’ Apologoi

By choosing to model his hodos dizēsios on the portion of the Apologoi that begins not at the departure from Troy, but rather from Aeaea – a kind of second point of departure, or a first point of informed departure – Parmenides in effect cuts off half of the Odyssey’s ring composition, thereby rendering linear the circular form of the erstwhile ring;Footnote 23 as we shall see, the effect is compounded by honing in on the first phase of the second half of the trip (the leg spanning Aeaea, Sirens, Scylla/Charybdis, Thrinacia) where the clearest progress is made anywhere in Odysseus’ journey home. Were one looking to shift from a circular, backward-turning mode of discourse in order to create a sequential, goal-directed mode of discourse, beginning from the very centre of the ring would accomplish this elegantly by shearing off a linear discursive pattern.

This observation leads to two further points. As noted, scholars have also discerned in the Circe episode a deeper shift from one kind of story-type to another; Circe’s island, that is, marks the point where a quest type becomes a nostos type – or rather, nostos becomes the mission of the quest.Footnote 24 The narratological correlate of the unguided wandering of the Apologoi before Odysseus ‘tames’ Circe is a kind of indefinite concatenation of quests, one linked to the other apparently without end. On the other hand, with Circe’s instructions in hand, the nostos, with its highly marked sense of destinationality, becomes the goal of the quest. A plot structure revolving around arrival at a single, ultimate destination, rather than in indefinite series of concatenated quests, could hardly have proved more useful to Parmenides’ notion of a hodos dizēsios.Footnote 25

Finally, there is also a geographic dimension to the point. The near miss with Ithaca after the first sojourn on the island of Aeolus only underscores how, from the perspective of the telos of Ithaca, Odysseus’ movement in the first half of the Apologoi is centrifugal. In certain respects, Circe’s island represents the far apogee of this centrifugality; not only is it at the end of the earth, near where the Sun has his dancing field, but it is also the one place where Odysseus himself forgets Ithaca and must be reminded by his crew.Footnote 26 Thanks to the goddess’s instructions, Odysseus’ movement through space, centrifugal up until his arrival on Aeaea, becomes centripetal.Footnote 27 In short, at the thematic, structural, narratological, and geographic levels, Parmenides would have found in the Circe episode elements of enormous value to rework for his own ends.

What does this mean for Parmenides? First, that scholars are mistaken when they attempt to draw a contrast between the kouros in Parmenides’ poem and Odysseus. Only if one fails to consider how the encounter with Circe divides the entire Apologoi into two parts – pre-Circean wandering, post-Circean journeying – can one claim, for example, that while ‘both protagonists travel far beyond the familiar track into eschatological locations, their journeys diametrically diverge’.Footnote 28 In fact, exactly the reverse is true. While it is certainly the case that ‘the kouros’ divine guides escort him directly to his goal … and precisely prevent him from undergoing the wandering which the poem associates throughout with error and ignorance’, that ‘Odysseus is repeatedly made to wander astray’ before his encounter with Circe is irrelevant.Footnote 29 What matters is that Odysseus’ divine guide also guides him directly to his goal that he may avoid the wandering which had plagued him earlier in the Apologoi.Footnote 30 Similarly, it is incorrect to assert that in Parmenides’ poem ‘the meandering Odyssean adventure is … reshaped as a linear journey’.Footnote 31 Attending to the structure of the Apologoi and the decisive role Circe plays in this portion of the Odyssey, we see instead that Parmenides leverages with tremendous skill a distinction between wandering and goal-directed journeying that was already clearly demarcated in Homer. By choosing to model his hodos on just the point in the Apologoi where Odysseus receives instructions from his female divinity with privileged access to knowledge (the guided, directed journeying that forms a true hodos, and not the untethered, backward-turning wandering of ignorant mortals), Parmenides plucks the portion of the Apologoi that suits his needs while sanitizing it of Odysseus’ pre-Circean wanderings by relegating them to a separate, distinct hodos he emphasizes must be avoided at all costs.Footnote 32 Instead, it is much more accurate – and much more interesting – to point out that by isolating a portion of the circumference of the Homeric ring composition that forms the Apologoi, the circular movement of the thematic and discursive progression of the Homeric text is refashioned as a linear, goal-directed (or at least non-circular) movement – a movement that is paralleled much more macroscopically by the transition Parmenides effects from a myth of nostos (of a return to a place of origin) to an extended deductive argument that leads to a conclusion.

This takes us to just the moment in Odyssey 12 when Circe promises to give Odysseus the instructions he will need to undertake his journey (Od. 12.25–26):

Before she narrates the hodos to Odysseus, however, she ‘takes him by the hand’ (ἡ δ᾽ ἐμὲ χειρὸς ἑλοῦσα, Od. 12.32) in order to speak to him alone;Footnote 33 then she begins the tale of the hodos. In Parmenides’ poem, having travelled to a distant place of revelation, a place at land’s end far from the usual haunts of men (ἀπ’ ἀνθρώπων ἐκτὸς πάτου, Fr. 1.27),Footnote 34 the male mortal voyager of the proem is greeted by a female divinity with privileged access to knowledge by nothing other than a clasp of the hand – χεῖρα δὲ χειρί | δεξιτερὴν ἕλεν (Fr. 1.22–23).Footnote 35 Then, she, too, begins the tale of the hodos.Footnote 36

5.1 Disjunctions

The tight parallels between Parmenides’ poem and Odyssey 12 extend beyond the dramatic scenario and the dramatis personae, and – what is much less recognizedFootnote 37 – well beyond the proem. When Parmenides’ goddess speaks, her language, too, echoes the Circe of Odyssey 12. So Circe opens her speech (Od. 12.37–38):

and introduces the choice between the two hodoi (Od. 12.56–58):

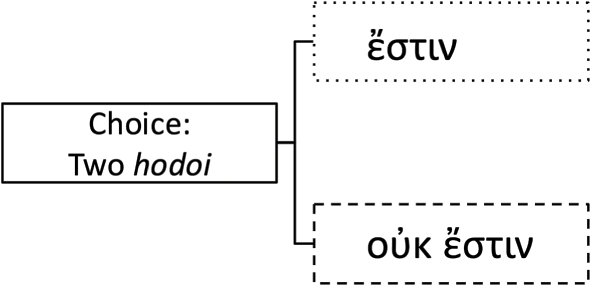

Parmenides’ goddess, meanwhile, begins (Fr. 2.1–2):

The linguistic overlap is striking: the goddess in question declares that she will tell her mortal charge (ἐγὼν ἐρέω, Od. 12.38; ἐρέω, Od. 12.58; ἐγὼν ἐρέω, Fr. 2.1) what comes next;Footnote 39 underscores the importance of listening to her (σὺ … ἄκουσον, Od. 12.37; σὺ … ἀκούσας, Fr. 2.1); mentions a closed set of hodoi that she will present (ὁπποτέρη … ὁδὸς … ἀμφοτέρωθεν, Od. 12.57–58; αἵπερ ὁδοὶ μοῦναι, Fr. 2.2);Footnote 40 and invokes the being of these roads, be it possible or actual, present or future (ὁδὸς ἔσσεται, Od. 12.57; ὁδοὶ … εἰσι, Fr. 2.2).

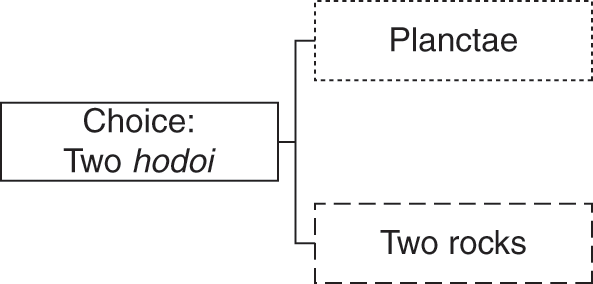

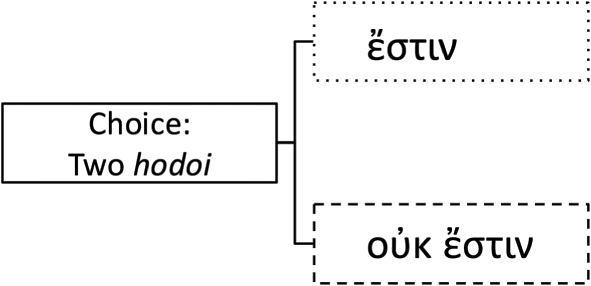

Continuing with these two passages, we find yet another similarity in the use of men … de … clauses to introduce the alternatives. In Circe’s hodos telling, men … de … clauses play an important role in articulating both pairs of alternatives one finds in the ‘Choice’ discourse-unit of the hodos (Od. 12.55–81, 12.73–110; see Section 4.2.2 above). So, too, Parmenides’ goddess presents the two hodoi as follows (Fr. 2.3–5):

Furthermore, in both Od. 12.59–81 and Fragment 2 lines 3 and 5, the goddess who expresses the krisis or fork in the road takes great care to present the two alternatives in a highly symmetrical manner. Circe correlates the same words (πέτραι, 12.59; λὶς πέτρη, 12.64 [Planctae]; πέτρη…λὶς, 12.79 [Scylla]), the same characters (e.g. Amphitrite (12.60 and 12.97)), and the same technique of ‘description-by-negation’ (12.62–4 and 12.83–84).Footnote 42 Likewise, the scrupulous congruities defining the phrasing of Parmenides’ Fragment 2 lines 3 and 5 have been illustrated by the close symmetry marking the pair rendered in propositional form (e.g. ‘to think that A and that B’ and ‘to think that not-A and that not-B’) and in rudimentary logical notation – e.g. ‘A and necessarily ¬(¬A)’ and ‘¬A and necessarily ¬A’.Footnote 43

The similarities between Parmenides’ Fragment 2 and Od. 12.55–126 extend to the level of discourse modes and the types of dependence that define their relationship (Figure 5.2). Recall that the normal discourse-unit in Odyssey 10 and 12 involves a narration portion, followed by description, which in turn provides the raw material for the instruction and/or argument that follows (Section 3.2, Section 4.2); the ‘either-or’ disjunction of the krisis was associated with its own variant of this pattern, with two distinct levels of description used to advocate rejecting and/or selecting one alternative (Section 4.2). The key features of this pattern are replicated in Parmenides’ Fragment 2. A narration section gives a choice between two hodoi (Od. 12.55–58; Parmenides Fr. 2.1–2), introduced via a men … de … clause, with close symmetry between the two terms. In the Odyssey, these terms are immediately subjected to a further qualification; so, of the πέτραι ἐπηρεφέες introduced by men …, Circe says (Od. 12.61):

While of οἱ … δύω σκόπελοι, introduced by de …, Circe says of the first (Od. 12.80):

In Parmenides, meanwhile, the following qualities are attributed in the men … de … clause (Fr. 2.4, 2.6):

All four lines just presented are classic description, with verbs in the third person present (καλέουσι, ὀπηδεῖ) and predicative uses of einai (Πειθοῦς ἐστι κέλευθος, and, in indirect speech, παναπευθέα ἔμμεν ἀταρπόν). If description is ‘oriented to the statics of the world’, then lines 4 and 6 of Parmenides’ Fragment 2 are perfect examples of it, attributing qualities to the two hodoi in question.

Figure 5.2 Levels of dependence, Od. 12.55–81 and Fr. 2.1–6

Fragment 2 then proceeds as follows (Fr. 2.6–8):

For their part, lines 7–8 display an ‘argument’ discourse mode comparable to Circe’s instructions at Od. 12.106–10:

In both cases we find a conclusion (Fr. 2.6, Od. 12.106) justified (gar)Footnote 49 by a modally charged (an/ken) negation (ou[te]) (Od. 12.107a, Fr. 2.7a, 8).Footnote 50 If Fr. 2.1–6 resembles the first fork in the hodos presented by Circe (Od. 12.55–81), at the upper levels of dependence – narration followed by description – Fr. 2.6–8 resembles the second (12.82–126) at the lower part of the level of dependence – description followed by argument.

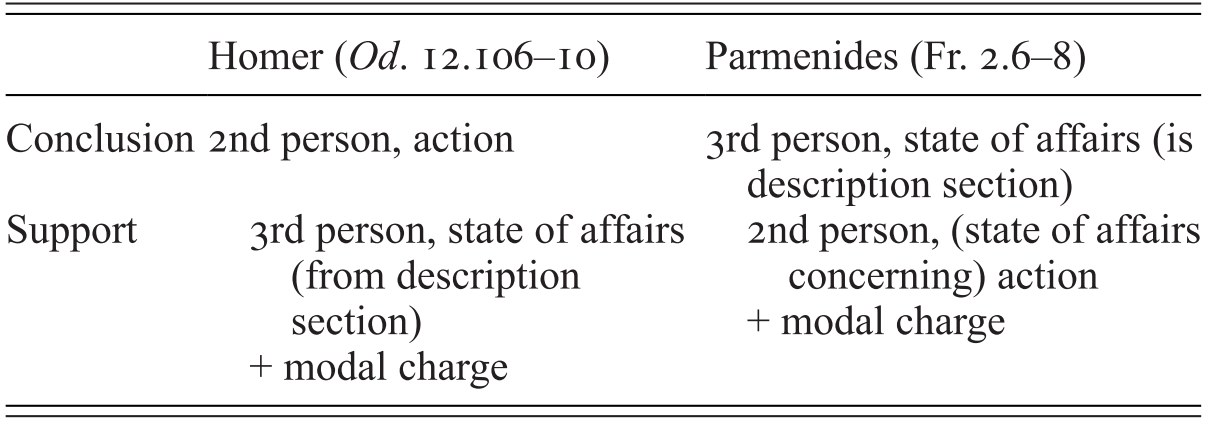

The major continuities between Parmenides’ Fragment 2 and Od. 12.55–126 thus obtain not only at the level of diction, but also in terms of the discourse modes used and the order of their sequencing: first narration, then description, and finally instruction/argument. But two very striking differences must also be noted. The first is verbal form. The two ‘conclusions’ of the ‘argument’ sections in the Odyssey take the form of second person imperative optatives (or infinitives) – μὴ σύ … κεῖθι τύχοις (Od. 12.106) and Σκύλλης σκοπέλῳ πεπλημένος ὦκα | νῆα παρὲξ ἐλάαν (Od. 12.108–09) – while the justifying support takes the form of the third person – οὐ … κεν ῥύσαιτό (Od. 12.107) and πολὺ φέρτερόν ἐστιν (Od. 12.109). In Parmenides, by contrast, the justifying support takes the form of the second person – οὔτε … ἂν γνοίης … οὔτε φράσαις (Fr. 2.7–8) – while the conclusion takes the form of a third person indicative (in indirect speech) – τὴν … παναπευθέα ἔμμεν ἀταρπόν (Fr. 2.6).

Second, in Homer the ‘argument’ sections are, as discussed, examples of practical reasoning and arguments insofar as they conclude in an imperative to a particular action. In Parmenides’ Fragment 2, by contrast, the conclusion is a proposition asserting a state of affairs, namely, that a certain object (the second route) has a particular quality (viz., being panapeuthēs). And, strikingly, the support for this claim now encompasses two actions – gignōskein and phrazein (Fr. 2.7–8) – as opposed to the Homeric patterns of deliberation, where the argumentative support is often anchored in basic facts about the world (e.g. the evil that Scylla is, is immortal – ἀλλ᾽ ἀθάνατον κακόν ἐστι [Od. 12.118] – because of the six heads that she has – τῆς ἦ τοι πόδες εἰσὶ δυώδεκα πάντες ἄωροι | ἓξ δέ τέ οἱ δειραὶ περιμήκεες [Od. 12.89–90]).

These transformations bring to the fore two developments of major import. In Homer, facts about the world, expressed in the third person indicative (sometimes negated with a modal charge) serve as the basis for (or provide the raw material for premises of) a kind of practical argument yielding a second person imperative pertaining to some action. In Parmenides, by contrast, second person actions (now negated with the modal charge of the Homeric description sections)Footnote 51 serve as the basis supporting and justifying the assertions that play the role of description, stating facts about the world and attributing qualities to entities that have been introduced (in this case, via the predicative esti, the fact that the second route is ‘entirely without report’, Fr. 2.6). The underlying relationship or ‘type of dependence’ between these two discourse modes has been reversed: the ‘argument’, in both cases centring on actions that can or cannot be taken by the interlocutor, in Parmenides’ poem ultimately supports the assertions made about the world (i.e. descriptions). If Parmenides is one of the first to defend, justify, or argue for his conclusions about the nature of the world, identifying the manner in which he adopts this traditional form of deliberation but reverses the relationship between description and action is of decisive importance (see Table 5.1, Figure 5.3).

Table 5.1 Verbal person and type of ‘situation’Footnote 56 in ‘description’ and ‘argument’ sections, Od. 12 and Fr. 2

Figure 5.3 Types of dependence, Od. 12.83–110 and Fr. 2.3–8

Second, the reversal of person between the verbs of conclusion and premise in Homer and Parmenides spotlights the crucial importance of one of Parmenides’ argumentative strategies: his argument’s dialectical nature.Footnote 52 This dialectical nature is invaluable for securing the foundations of his argument because Parmenides’ assertion at Fr. 2.7–8 ‘is axiomatic within a dialectical context’.Footnote 53 This manoeuvre responds to the problem of what strategy a thinker whose goal is to ‘cut free from inherited premises’ can devise to accomplish this goal.Footnote 54 If one can no longer make arguments on the basis of facts established by description (and even if one wants to do just the reverse, and establish facts through the arguments one presents) how should one proceed? What else could one do other than ‘start from an assumption whose denial is particularly self-refuting’?Footnote 55

These are not the only elements from Od. 12.55–126 to feature prominently in Parmenides’ Fr. 2. Of course, third person singular indicative forms of einai continue to be very important beyond the beguiling but portentous names given to the hodoi at Fragment 2 lines 3 and 5. Similarly, predicative uses of esti attribute qualities to these hodoi, as at Fragment 2 lines 4 and 6. Finally, the particle gar links the conclusion (stated first) to its argumentative support. Finally, the modally charged negations important in Od. 12.55–126 remain fundamental to Parmenides’ Fr. 2, serving as the essential premises for major conclusions (Od. 12.107 for conclusion at Od. 12.106; Fr. 2.7–8 for conclusion at Fr. 2.6) – and if one accepts the view that the force of Fragment 2.6–8 springs from the self-defeating nature of any attempt to refute it, the persistence of the modally charged negation (combined with the switch from third to second person) acquires momentous significance for the history of thought.Footnote 57

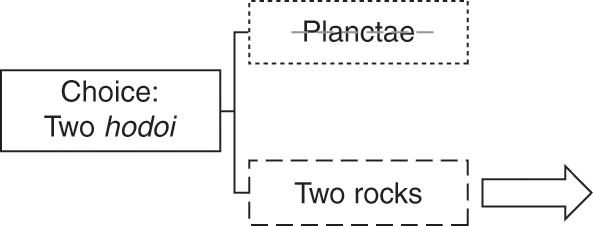

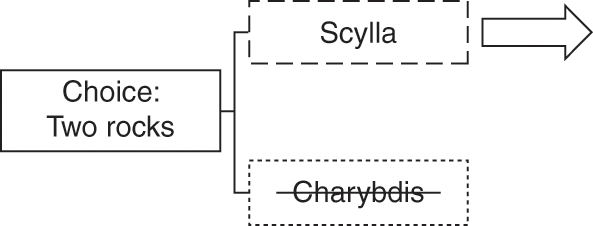

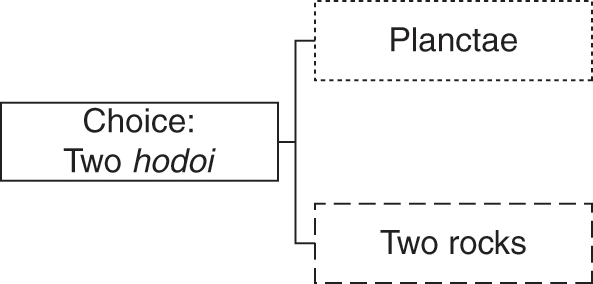

We have already discussed at great length the arresting confluence of features found where Gill’s Homeric pattern of deliberation – consideration of different courses of action, rejection of one course, conclusion – intersects with a forking of a hodos. In this special case, ‘course of action’ and ‘course’ – viz. a cursus, part of the itinerary of a journey through physical space – are perfectly coextensive (Section 4.2.3, ‘Assessments and Cautions’); accordingly, basic dynamics of the use of space, namely, the impossibility of travelling two routes at the same time (a crystalline way of imaging – or indeed imagining, thematizing – the abstract notion of mutually exclusive, exhaustive alternatives), or the impossibility of getting from point A to point C except by way of some point B, shapes the nature of the choice. As a result, when Homeric deliberation about what courses of action to take is deliberation about courses, the matrix of possible decisions is concretized in the form of two mutually incompatible, exhaustive alternatives: in other words, a krisis, or exclusive disjunction (see Figures 5.4a, b, c).Footnote 58

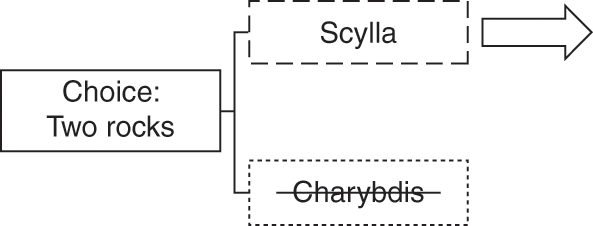

Figure 5.4b Circe’s exclusive disjunction (rocks), Od. 12.73–126

In the ‘Choice’ hodos-units of Odyssey 12, we saw that the rejection of one option as a crucial preliminary to a conclusion can take various forms (see Figure 5.5a, b, c). In the case of the Two Roads, the rejection is merely implicit, and emerges from an extended series of ‘descriptions-by-negation’ which are in fact tantamount to a ‘proscription-by-negation’ (Section 4.2.2). In the case of the Two Rocks, the rejection and selection of the other alternative are explicit (Od. 12.106–08). This rejection takes on a special kind of potency within the framework of the mutually exclusive, exhaustive alternatives of the forking hodos. Circe lays bare the power of the either/or choice when noting that Scylla is to be selected not because she represents a desirable option (six men will die); rather, given that nobody would survive the alternative, she is in practice the only option (Od. 12.106–10).Footnote 59

Figure 5.5c Fr. 2: Rejection explicit, selection implicit

Finally, modally charged negation plays the crucial role in eliminating one of the alternatives in the case of the Two Rocks choice (12.107), in effect forcing Odysseus to choose the other term, no matter how grim the prospect (Section 4.2.2.1, ‘Three Features’). Framed in terms of modally inflected impossibility – nobody would be able to save Odysseus, not even Poseidon, master of the sea (Od. 12.107) – this rejection takes on a kind of general, theoretical force, expressing something like a categorical claim. What we see in Fragment 2, then, is a very powerful synthesis of features common in Homeric language and thought – the pattern of Homeric deliberation deemed typical by Gill, a modified ‘description-by-negation’ technique (with a modal charge) – that, when applied to a specific kind of choice (between bifurcating paths denoting physical movement through space), combine to require the selection of one possibility by virtue of the necessary rejection of the other.Footnote 60 This is the moment to cash out the observations in Section 4.2.3 of the previous chapter. Seen from this perspective, Parmenides’ krisis, or ‘exclusive disjunction’, at Fr. 2 loses its novelty and becomes an argumentative device taken over ready-made; it is the use to which this argumentative strategy is put that is transformative and revolutionary.

5.2 Opening Moves

The majority of the transformations effected by Parmenides that we have examined so far come at the level of ‘types of dependence’; there is also, however, one vitally important change undertaken by Parmenides at the level of rhetorical schemata. In Homer, the ‘Choice’ hodos-unit comes in the middle of the journey, after the meadow of the Sirens and before Thrinacia. In Parmenides, by contrast, the krisis portion forms the very first hodos-unit we encounter (see Figure 5.6).

Figure 5.6 Shift: Krisis placed at the beginning of the hodos

Why is this significant? Lloyd noted that ‘the aims of The Way of Truth are clear: Parmenides sets out to establish a set of inescapable conclusions by strict deductive arguments from a starting point that itself has to be accepted. Those are features it shares with later demonstrations.’Footnote 61 The development of interconnected deductive arguments we shall explore in the next chapter; what is at stake here is the notion that, as Parmenides’ successor Diogenes of Apollonia would put it some decades later, ‘anyone beginning an account ought to make the starting point [or principle] indisputable’ (64B1).Footnote 62 Fragment 2 plays the definitive role in securing this.Footnote 63

To put everything together: Parmenides accomplishes this ground-breaking leap in the structure of rigorous argumentation by reconfiguring and recombining discursive elements found in Homer. At the level of ‘types of dependence’, he reverses the roles between description and argumentation, using the argument section to support an assertion advanced in the description section. This argument in turn can be decoupled from previously established facts and remain free-standing: it is self-supporting or self-verifying,Footnote 64 partly as a result of the use of the second person, which gives the argument its dialectical dynamics and force.Footnote 65 And this argument section, insofar as it works in the service of a claim that, in typical Homeric fashion, rules out one alternative – and does so, following Od. 12.55–126, in the context of an exclusive disjunctionFootnote 66 – therefore demands the selection of the other alternative.Footnote 67 Moreover, the modal charge attached to the rejection of the one possibility generates a kind of symmetrical modal valence that is projected onto the other route, which must necessarily be selected if one is to proceed further down any path at all.Footnote 68 All this takes place within one hodos-unit on the journey spelled out by the female goddess to her male mortal charge. Moving this unit to the front of the itinerary, meanwhile, not only forces the mortal voyager down a particular path, ruling the alternative out, but does so from the very beginning of the voyage– before there is any chance of selecting a different starting point, before there is any alternative but to confront this decisive initial krisis.Footnote 69