Council Houses and Democratic Institutions

Historians, political scientists, and others generally associate the birth of democracy with the emergence of so-called states and center it geographically in the “West,” where it then diffused to the rest of the world (Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996; Tilly Reference Tilly and Tilly1975). Because these perspectives rely on overly narrow typological definitions, they remain distinctly colonial and Western-centric in their scope. Importantly for our current research, such perspectives, as highlighted by Blanton and Fargher (Reference Blanton and Fargher2016), overlook the importance of institution building in the construction of collective political formations. From perspectives focused on institution building, collective action is intimately tied to the process and maintenance of democratic and collective states of affairs, including such things as civic benefits, commoner voices, and the promotion of egalitarianism, among others. It therefore becomes critical to understand what institutions structure these social relationships. Institutions, here, are the tangible, material ways in which people are organized to “carry out objectives using regularized practices and norms, labor, and resources” (Holland-Lulewicz et al. Reference Holland-Lulewicz, Conger, Birch, Kowalewski and Jones2020:1). We argue that the archaeological record of the American Southeast provides a case to examine the emergence of democratic institutions before the European invasion and to highlight the distinctive ways in which such long-lived institutions were—and continue to be—expressed by Native Americans.

Cooperation, particularly among larger groups, comes with a set of novel circumstances that must be negotiated in order for it to not only endure but bring with it the desired benefits to all those engaging in such acts (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016). Democratic institutions, specifically characterized by their broad engagement and inclusiveness, are particularly complex types of cooperation that require attendant institutions to ensure that the problems inherent in collective action (e.g., free riding, aggrandizers, authoritarians, corruption, uninformed decisions, etc.) do not subvert the public good. What is perhaps underappreciated is the great variability in democratic institutions given that scholars tend to focus on the history of democracy as it relates to Western notions of politics. In doing so, their work continues to hold up an ideal that is in some cases highly exclusionary. For example, the early American formulation of democracy was limited to certain individuals (i.e., land-owning men of Euroamerican descent). Consequently, what results is an ideal of democracy that pervades discourse rather than a consideration of the institutions that promote or limit despotic control of the few over the many (Kowalewski and Birch Reference Kowalewski, Birch, Bondarenko, Kowalewski and Small2020:46).

Specifically, we argue that by focusing on democratic institutions (i.e., not democracy itself), it positions us better to understand not only the history of cooperation and inclusivity of governance within a specific region but also the variability in the ways in which different groups of people instituted such traditions. Furthermore, shifting this focus away from rulers, elite, and chiefs provides a more nuanced approach as to how people govern themselves, because even small-scale democratic institutions and procedures can have reverberating effects within the entire political system (e.g., the choosing of leaders; Bondarenko Reference Bondarenko, Bondarenko, Kowalewski and Small2020:54). We acknowledge that just because there are democratic institutions does not mean that there are no other coercive forces or practices, as Denisova (Reference Denisova2020:371) notes in her discussion of West African political life. Finally, if we can identify the material manifestations of different forms of institutions, then archaeology can play a critical role in tracing shifts in horizontal and vertical dimensions of leadership and collective action over time. This, of course, allows for a more directed exploration of how such varying institutions shift diachronically within a given context (Bondarenko Reference Bondarenko, Bondarenko, Kowalewski and Small2020:84; Feinman Reference Feinman, Levinson and Ember1996:189).

Importantly, as we note, democracy and democratic institutions in particular are not solely the purview of Western societies. And, as we allude to above, because scholars steeped in Western traditions focus on this topic, the narrative is interwoven with Western myths of classical heritage. In recognizing this, we are better able to discuss substantively the contribution of Native Americans to such institutions. Consequently, as Zoe Todd (Reference Todd2016:4) writes in recognizing the contributions of Indigenous thinkers, we are better able to adopt a decolonial perspective on these wider concepts. To us, this includes not only Indigenous scholars but also Indigenous ideas and concepts expressed in landscapes of the past. Such a perspective forefronts the idea that “Indigenous traditions, cultures, and identities are not historical artefacts or museum pieces” but rather are “contemporary” and “critical” to shaping our understanding of the world, academic research, and a host of other issues (Alfred Reference Alfred2015:3). Archaeologists working in collaboration with Indigenous scholars are uniquely positioned to be advocates for such a perspective.

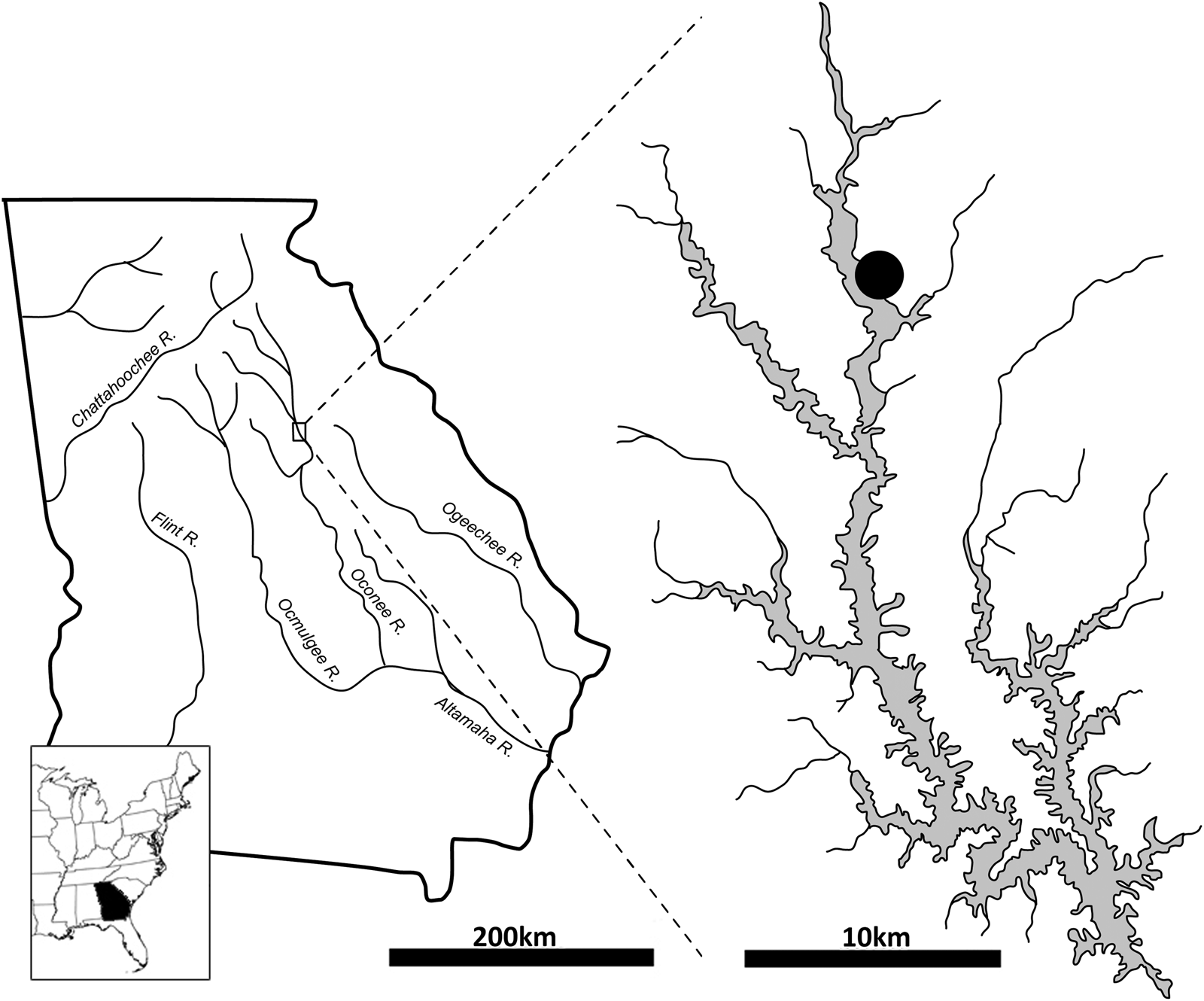

Our research at the Cold Springs site (9GE10), located in the temperate forests of northeastern Georgia, USA (Figure 1), provides important insight into the earliest documented council houses in the American Southeast. Here, we present new radiocarbon dating of these structures along with new dates for the associated early platform mounds at the site that indicate intensive construction and use over a relatively short period between approximately cal AD 500 and 700 or less. Previous research at the site indicates that it likely did not have a large resident population. Instead, it served an outlying population that regularly gathered at the site (Fish and Jefferies Reference Fish and Jefferies1983; Jefferies Reference Jefferies and Hally1994). We argue that the coupling of early platform mounds with council houses, including a likely plaza between them, represents an enduring pattern that lasted through the early periods of European invasion and colonialism and that continues to this day as traditionally maintained “square grounds” among Ancestral Muskogean communities. We use the term “Ancestral Muskogean” to refer collectively to the groups that spoke dialects of this language family (Martin Reference Martin, Fogelson and Sturtevant2004). Specifically, we argue that the emergence of council houses—large circular public buildings called Cukofv Rakko [cok-ó:fa ɬákko] in the Mvskoke [maskó:ki] language—represent the early materialization of democratic institution building and collective action(s) that were important to the overall public good of the community. The institutions linked to the Cukofv Rakko, we argue, represent long-lived traditions of collective governance and democratic institutions to varying degrees. We suggest that the repeated materialization of these institutions, in the form of public architecture and its attendant social relationships, is what made such strategies of collective governance so durable.

Figure 1. Location of the Cold Springs site in the Wallace Reservoir (Lake Oconee) in northern Georgia, USA. (Produced by Jacob Holland-Lulewicz.)

Considering Council Houses and Native American Political Life

Archaeological interpretations of southeastern Native American political systems, particularly those that existed after AD 1000, are predicated on the presence of earthen platform mounds, as well as bioarchaeological patterns, settlement patterns, and other types of evidence. Since the 1970s, platform mounds especially have been viewed as structures linked to a “chiefdom”-type social organization, largely based on an inherited political elite. Cobb (Reference Cobb2003) provides a nice review of this work, and as he notes, more recent research is beginning to challenge and complicate this picture (see also Blitz Reference Blitz2010; Wilson Reference Wilson2008). Platform mounds are portrayed frequently as chiefly residences with the overarching, hierarchically tiered political landscape viewed through this lens. Within this framework, archaeologists have readily drawn on specific historical documents (i.e., the De Soto chronicles) to interpret the various political roles within these societies, assigning terms such as Mekko [mí:kko] (often interpreted by the Spanish as meaning “chief”) and the like to define and emphasize unequal relationships of social, economic, and political power (for a discussion of these points, see Foster Reference Foster2007:4–6).

As Foster (Reference Foster2007:4–5) discusses, the overarching validity of the observations included in the De Soto chronicles have yet to be widely demonstrated. He notes that among the “historic” period Creeks, people worked on collective projects, including the storing of food in centralized structures. He states that if these centralized storage areas had been located next to the mounds in the sixteenth century, then such storehouses could easily have been misinterpreted by Spaniards as tribute to the chief (Muller Reference Muller1997:40–41) rather than as public goods. Consequently, according to Foster, we need to consider a range of biases when reading the De Soto chronicles and what they mean for interpreting sixteenth-century and earlier Native political systems. Traditionally, the archaeological lens used to examine these ethnohistoric accounts has added yet another layer of bias, given that most archaeologists were reading and interpreting these texts from the perspective of 1960s-era neoevolutionary anthropological thought, emphasized chiefdoms—particularly, the power of chiefs. Of course, Foster is not the only one to point this out, and years ago, Muller (Reference Muller1997:72–78) leveled a heavy critique against the untested assumptions of the chiefdom concept as defined by these accounts of Native polities, preferring instead to focus on confederation and the limited power of the individuals who held such roles. Interestingly, in a rather detailed—and somewhat negative—review of this book, Carneiro (Reference Carneiro1998:182–183) asks that if the power of chiefs were so limited, then how did chiefdoms emerge in the first place? Such a statement underscores the nature of typological thinking.

After reading Carneiro's review of Muller, it seems that part of Carneiro's issue is that there is little difference in the political organization from those groups that predate AD 1000 (i.e., tribes) compared to the groups that came after (i.e., chiefdoms). We argue that this may, however, be a key point to consider, because the institutions that governed groups prior to this point likely were more durable and prevalent during later time frames than archaeologists often use in their framing of Native American governing principles. As Pauketat (Reference Pauketat2007:207) observes, the chiefdom concept itself has a way of blinding archaeologists to “complexity and historicity.” In this case, we may be blinded to the deeper institutions of governance because of the inherent limitations imposed by historical accounts and neoevolutionary scholarship.

In contrast, for societies with platform mounds that predate AD 1000, archaeologists tend to favor more communally, ritually oriented interpretations (see Knight Reference Knight1990, Reference Knight, Hayden and Dietler2010; Pluckhahn Reference Pluckhahn2003; Singleton Hyde and Wallis Reference Hyde, Hayley and Wallis2020) as the strong, post–AD 1000 interpretive link based on ethnohistoric observations between hierarchy and platform mounds crumbles. In this way, archaeologically derived categories, with their attendant, often untested and tenuously supported assumptions about sociopolitical relationships, continue to structure discontinuous political histories, preferencing narratives of historical discontinuity and transformation over those that highlight and explore the more enduring patterns encoded in the archaeological and ethnohistoric records. Such categories serve as enduring barriers to theorizing effectively such issues as collective action, governance, or leadership that is relevant across the broader social sciences (Holland-Lulewicz Reference Holland-Lulewicz2021:2).

There are numerous examples of earthen platform mounds across the American Southeast that predate AD 1000, and although some date thousands of years prior, these types of mounds become ubiquitous across the landscape by AD 500 (Jefferies Reference Jefferies and Hally1994; Kassabaum Reference Kassabaum2019, Reference Kassabaum2021:87; Lindauer and Blitz Reference Lindauer and Blitz1997; Pluckhahn Reference Pluckhahn1996; Pluckhahn and Thompson Reference Pluckhahn and Thompson2018). As Kassabaum (Reference Kassabaum2019:188, Reference Kassabaum2021:18–22) points out in looking at the total variation in platform mound differences, characteristics differentiating pre– and post–AD 1000 platform mounds are not altogether clear, suggesting that the meaning and use of each mound must be contextualized at the site level. Consequently, the clear breaks and/or shifts in political governance that archaeologists often discuss are based less in the reality of data related to platform mounds and more on arbitrarily defined temporal boundaries that coincide with other shifts in material culture (i.e., pottery types) and subsistence practices (i.e., intensive maize agriculture). Importantly, in attempting to highlight the historical continuity of institutions of governance across Ancestral Muskogean homelands, the documentation alone of pre–AD 1000 platform mound construction in these regions represents strong evidence for an in situ development of this form of architecture and its associated institutions. This would suggest yet another retained local institution rather than a shift in the form of governance externally tied to larger shifts in neighboring or far-flung regions to the west after AD 1000. In fact, some of these traditions may be the result of partial migrations from more southernly groups during an earlier expansion event coalescing in this area of Georgia (see Pluckhahn et al. Reference Pluckhahn, Wallis and Thompson2020).

Given the available evidence, the construction of early mounds points toward integrative communal actions rather than those that promote hierarchical relationships. We question, then, why there should be such a dramatic break in, and abandonment of, the communal nature of mound building after AD 1000. Part of the reason for this is the continued embeddedness of platform mound–centric views, as argued by Kassabaum (Reference Kassabaum2019:188), which ignores—especially of earlier periods—plazas and other forms of the built landscape and the institutions potentially associated with such undertheorized features. As we will show, for Cold Springs, this included large circular structures whose use and construction unequivocally continued across the AD 1000 threshold and into today.

Council Houses in the American Southeast

Prior to the present study, the earliest documented council houses appear to be relegated to the post–AD 1000 era, and are therefore regarded as a late development that increased in popularity during the time of European colonialism (Anderson and Sassaman Reference Anderson and Sassaman2012; Sullivan Reference Sullivan, Birch and Thompson2018). In terms of theoretical discussions of political systems, few archaeologists deal explicitly with these structures, opting instead to continue to view political governance vis-à-vis platform mounds and biased European accounts. In the few examples where researchers do discuss council houses and similar structures, in both the Ancestral Muskogean homeland and adjacent areas, they do so usually in terms of egalitarian, ritual, and collective action, where a greater number of individuals have voice in governance, and the power of an individual “elite” is constrained by the group (see Anderson Reference Anderson1994; Rodning Reference Rodning2009, Reference Rodning, Gougeon and Meyers2015; Thompson Reference Thompson2009; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Marquardt, Walker, Roberts Thompson and Newsom2018). We provide a brief review of the variation of these public structures in the American Southeast here to understand the broader context of these buildings.

Council houses—also sometimes referred to as rotundas or townhouses depending on the region—have several characteristics that distinguish them from domestic architecture. These structures are circular or square with rounded edges, and they range from 12 to 37 m in diameter (Thompson Reference Thompson2009:Table 1). These were not merely large houses, because they likely required specialized knowledge and a large labor pool for their construction, often necessitating maintenance in the form of rebuilding episodes and post replacements, as evidenced by archaeological excavations elsewhere in the Southeast (see Rodning Reference Rodning, Gougeon and Meyers2015:123; Thompson Reference Thompson2009:458; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Marquardt, Walker, Roberts Thompson and Newsom2018). An eighteenth-century description of one of these structures by William Bartram gives a good sense of the intricacies of construction, particularly those that would leave no archaeological signature.

The rotunda is constructed after the following manner, they first fix in the ground a circular range of posts or trunks of trees, about six feet high, at equal distances, which are notched at top, to receive into them, from one to another, a range of beams or wall plates; within this is another circular order of very large and strong pillars, above twelve feet high, notched in like manner at top, to receive another range of wall plates, and within this is yet another or third range of stronger and higher pillars, but fewer in number, and standing at a greater distance from each other; and lastly, in the centre stands a very strong pillar, which forms the pinnacle of the building, and to which the rafters centre at top; these rafters are strengthened and bound together by cross beams and laths, which sustain the roof or covering, which is a layer of bark neatly placed, and tight enough to exclude the rain, and sometimes they cast a thin superficies of earth over all [Bartram Reference Bartram1791:368].

The largest currently known council house, at 37 m in diameter, is at San Luis de Talimali in northern Florida (Figure 2). This structure was said to be able to hold thousands of people (Shapiro and Hann Reference Shapiro, Hann and Thomas1990:520). For the Atlantic coast, Spanish accounts note that these buildings regularly held hundreds or thousands of people, with these figures given by more than one account for varying areas (Hann Reference Hann1996:90). The ability of these structures to house so many people may be one of their defining characteristics and may have been directly correlated to the size of the local community. Descriptions from the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries point to some variation in size dependent on the density of the local population (Hann Reference Hann1996:259, 289). As Hann (Reference Hann1996:91) notes from a Spanish governor's 1602 observation, the “council house symbolized the bond of community for villages where dwellings were often widely scattered.” Furthermore, in another account, Spaniards likened belonging to a council to citizenship and indicated that such places were “where it is the custom to hold the assemblies and hearings [for those] who recognize they are united to the said council houses" (Hann Reference Hann1996:91).

Figure 2. Examples of council house–related layouts: (a) plan layout of the council house at San Luis de Talimali (adapted from Shapiro and Hann Reference Shapiro, Hann and Thomas1990:Figure 32-1); (b) layout of the core architectural elements at the Irene site showing the plan of the rotunda / council house at the bottom (produced by Victor D. Thompson, adapted from Caldwell and McCann Reference Caldwell and McCann1941:Figure 13); (c) photograph of the Copeland site rotunda (adapted from Williams Reference Williams2016:Figure 10); (d) drawing of “Creek” ceremonial ground by Swanton (Reference Swanton1928:176) as compared by Caldwell and McCann (Reference Caldwell and McCann1941:69–73).

Sixteenth-century descriptions indicate that the interiors of these buildings were highly structured, with seating arrangements and histories painted on the walls (Shapiro and Hann Reference Shapiro, Hann and Thomas1990:512). In many of these structures, descriptions indicate that there were often interior supports and smaller posts for seating platforms that were designed to denote rank and status (see below; Worth Reference Worth1998:93). Such designations of seating were likely long traditions, and both sixteenth-century Spaniards and eighteenth-century English colonizers note similar arrangements (Bartram Reference Bartram1791:236). One cannot help but think of and draw comparisons to the “earth lodge” excavated at Ocmulgee near Macon, Georgia, with its raised seating arrangement and alter in the shape of a bird with forked eye (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1946). In addition, some colonial descriptions, especially along the Georgia coast, seem to indicate that some had small rooms or alcoves defined by the seating platforms (Hann Reference Hann1996:90). From the layout of the fourteenth-century council house at the Irene site (36 m in diameter), it would seem that this form of architectural layout was in place prior to the sixteenth century (see Figure 2).

Although it appears that some council houses had architectural elaborations, not all were the same. In fact, based on descriptions by Hitchcock of an 1842 design of the Creek Tuckabatchee council houses on the Muscogee Reservation in Oklahoma, some had a more “open” design that did not include interior supports (Swanton Reference Swanton1922; Williams and Jones Reference Williams and Jones2020). This was no small structure either, and was around 18 m (ca. 60 ft.) in diameter and 9 m (ca. 30 ft.) tall (Williams and Jones Reference Williams and Jones2020). Therefore, we must be careful regarding our interpretation of patterns of post molds without obvious internal supports, given that some of these structures lacking clear evidence for internal posts could indeed be roofed and not have been simply blinds and screens, as archaeologists sometimes logically interpret such patterns. The recent large circular post patterns at Poverty Point in Louisiana come to mind (Hargrave et al. Reference Hargrave, Berle Clay, Dalan and Greenlee2021), and although the very largest of these may not be such a structure, some smaller ones deserve careful consideration as potential council houses as one hypothesis. If this were found to be the case, then it would push this architectural form back thousands of years, which may not be all that surprising given the time depth of mound building in the region.

In terms of material remains, large ceramic vessels associated with several of these structures also indicate that ceremonial foods were consumed during councils—notably, a tea called vsse [ássi] made from yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria) used in ceremonies (i.e., the White Drink, aka the Black Drink) and meetings (Shapiro and Hann Reference Shapiro, Hann and Thomas1990). In fact, during excavation of the large council house at the Irene site along the Georgia coast, a concentration of large vessels were recovered, located just outside the building interpreted as being used in the preparation of the Black Drink (Caldwell and McCann Reference Caldwell and McCann1941:31; see also Williams Reference Williams2016). Large ceramic vessels are still used by the Muscogee people today in the preparation of medicine for traditional gatherings. Smaller features can also be observed in the interior of council houses. In addition to structural supports, some had pits for small fires or cob-filled smudge pits (Shapiro and Hann Reference Shapiro, Hann and Thomas1990:518).

There appears to be some patterning where council houses are located vis-à-vis other community structures and outlying settlements. In several instances, both in historic documents and the archaeological record, we find that council houses are juxtaposed across an open plaza to either an earthen mound or another public building. Two examples of this are from the Irene site, which faces a mound across a plaza, and at Mission San Luis, which faces the mission church across the plaza (McEwan Reference McEwan and McEwan2000:71). For Irene, Caldwell and McCann (Reference Caldwell and McCann1941:69–73) suggest that the layout is similar to “Creek” ceremonial grounds (see Figure 2).

In other instances, people constructed council houses on the tops of mounds. William Bartram (Reference Bartram1791:345) observed a large Cherokee council house that was over 9 m tall (ca. 30 ft.) sitting on top of an earthen mound some 6 m high (ca. 20 ft.). The location of the council houses—or at least large public houses—on the tops of mounds occurred as early as approximately AD 1000 in southern Florida (Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Marquardt, Walker, Roberts Thompson and Newsom2018). At Ancestral Muskogean sites, however, this appears not to have been the usual pattern—or at least not a pattern that has been identified. This absence may be related to the physical limitations of mound summits to accommodate such structures, as Rodning (Reference Rodning, Gougeon and Meyers2015:123) points out for some Cherokee sites.

At both Cherokee and Ancestral Muskogean villages that lack earthen mounds, one of the more common patterns is to have the council, or town house, located nearer to the center of the plaza area than the other domestic structures. Historic documents note this pattern, and excavations at sites such as King in northwestern Georgia (Hally Reference Hally2008) and Coweeta Creek in North Carolina (Rodning Reference Rodning2009, Reference Rodning, Gougeon and Meyers2015) have revealed similar patterns.

In the Oconee Valley of Georgia, where Cold Springs is located, there are a number of sites with council houses (see Figure 2). However, unlike the regions discussed above, during the post–AD 1000 era, the valley was defined by large, dispersed settlement patterns of small extended household settlements throughout the area (Williams Reference Williams2016). Williams (Reference Williams2016) documents at least three separate locations of council houses or rotundas in the valley, which include the Joe Bell, Copeland, and Bullard Bottom sites. The earliest of these is Copeland, which dates sometime between AD 1300 and 1400, but it was likely reoccupied into the sixteenth century (Williams Reference Williams2016:119). All three sites document the use of council houses from at least the 1300s to the 1700s (Williams Reference Williams2016:123). These sites, however—except for the possibility of Copeland—have no clear evidence of year-round occupation. Consequently, Williams interprets these as “Busk” sites, which are ceremonial and social gatherings akin to those described by Swanton for the Muscogee (Williams Reference Williams2016:122). “Busk” is an anglicized term embraced by archaeologists, and its origin is derived from Posketv [posk-itá] (meaning “to fast”), which is a critical part of the Green Corn Ceremony. If the interpretations of these sites is correct, then this would be yet another pattern where the council house plays a major role in the lives of people—and is therefore an enduring institution, as we detail below.

Councils and Ancestral Muskogean Governance

Descriptions by Muskogean scholars and oral histories, as well as accounts by colonial-minded Spaniards and Englishmen, all overlap with one another regarding some of the key characteristics of Ancestral Muskogean governance. Descriptions of Ancestral Muskogean governance suggest two guiding principles, which include “natural laws” and democratic consensus (Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri2001:72–73). The natural laws are the ones that structure the relationship between culture and nature, which is viewed as a circular one—a type of community circle that includes both humans and world spirits (e.g., Grandfather Sun; Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri2001:96). In essence, these natural laws, observed and passed down from generation to generation, are important to understanding the “order of things” and were gifted by the “law-giving spirts” to determine how one treats the world (e.g., plants, animals, astronomical bodies). This, in turn, operationalizes rules for human activities such as hunting, agriculture, and medicine (Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri2001:72). Interwoven with these natural laws, and covering all other aspects of relationships not covered by these natural laws, is the importance of democratic consensus, which is a more involved action than a simple consensus. As Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri (Reference Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri2001:73) note, democratic consensus building involved a “process of consent” that included “interlinked centers of decision-making,” which occurred on multiple levels, including “community councils, regional councils, clan mothers, beloved men and beloved women.” In all of these situations, consensus was achieved through a series of oratory events and open discussions of points and counterpoints (Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri2001:73).

Although politics of inclusivity were the norm of policy making, this does not mean that there were no differences, in status or position, between individuals and groups based on a variety of factors. However, archaeologists have focused on these differences and roles to highlight the agencies of a political elite, often downplaying the collective nature and constraints put on such individuals (for examples and a discussion, see Foster Reference Foster2007; King Reference King2003; Muller Reference Muller1997). Although it is possible that in some instances individuals accrued a certain amount of power, in general, the institutions of Native American governance across much of the Southeast were focused on consensus-based decision making and functioned as “checks and balances” on aspiring elites’ abilities to cement permanent political power (Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri2001:73; see also Muller Reference Muller1997). In many instances, these formal leaders seem more along the lines of a “first among equals” and highly beholden to councils, having been described as executors of policies enacted through council-based decision making (see Muller Reference Muller1997:67). In addition to the rather limited political powers of individuals, these descriptions also suggest that political engagement was open to a wide variety of people, including women, who often played prominent roles in governance, which included sometimes holding the role of Mekko (Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri2001:79; Muller Reference Muller1997; Trocolli Reference Trocolli and O'Donovan2002). Consequently, it seems that, in terms of overall inclusiveness, democratic governance among Ancestral Muskogeans was more inclusive than some of the so-called earliest examples of these kinds of institutions in ancient history (e.g., Athens, Greece). Indeed, in regard to American democratic ideals, we have only recently approached the kind of inclusivity characteristic of Muskogean governance (i.e., the United States since the 1960s).

We argue that council houses were the early manifestations of a form of collective governance that can be confidently documented in one form or another over the last 1,500 years among Ancestral Muskogean societies. Sources indicate that council houses were the hub of political life within communities and often across regions. And although council houses were, in part, a bridge to ceremonial worlds, they were key forums in which to discuss and debate the collective good and governance (Historic and Cultural Preservation Department–Muscogee [Creek] Nation, personal communication 2021; Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri2001:90–91). In the archaeological record, there are many variants that could be included under the rubric of council houses, including “earth lodges,” named so because of their earthen covering or circular embankments—or “town houses” among the Cherokee (Fairbanks Reference Fairbanks1946; Rodning Reference Rodning, Gougeon and Meyers2015). Our purpose here is not to delve into the details regarding the differences of these structures but rather to point out that despite the difficulty in finding these buildings archaeologically, they show up on a number of sites, often associated with platform mounds. Importantly, however, they were also constructed at sites and in regions where platform mounds were either rare or abandoned as a practice (e.g., Georgia coast; Thompson Reference Thompson2009), indicating their elevated importance in governance, perhaps more so than that of the platform mounds that have largely captured the attention of archaeologists.

Not many researchers have attempted to place council houses in their overall context; however, the few studies that have demonstrate a variety of relationships to other forms of architecture (e.g., plazas, mounds; for an exception, see Rodning Reference Rodning, Gougeon and Meyers2015). Sometimes these structures are in the center of villages; others appear to be centers where regional populations gathered. As described above, some were located across from platform mounds or other important buildings across an open plaza and bounded by a palisade wall on all sides, suggesting the resemblance to the contemporary Creek Square Ground. This is not unlike the layout of the architecture at Cold Springs (see below), which is much older than Irene, by approximately 800 years.

When one considers the sum of the oral, historic, ethnographic, and archaeological records, it becomes apparent that far from isolated structures, council houses were more ubiquitous than we likely have evidence for currently and, as we will demonstrate, have deeper histories than archaeologists currently appreciate. The new chronology we present for these structures at Cold Springs has implications for the persistence of democratic institutions in Native American societies. For this reason, it forces us to rethink Western scholarly portrayals of the nature of power and authority among the Native American societies of the Southeast prior to, and enduring through, European colonization.

Research Objectives and Excavations

The University of Georgia conducted excavations at the Cold Springs site over 40 years ago as part of the archaeological salvage work for the Wallace Reservoir Project (1971, 1973–1975, 1977–1978) that preceded the inundation of the valley as Lake Oconee in Georgia (see Figure 1). As part of this project, archaeologists identified scores of sites, and large excavations occurred at a number of the larger ones, particularly those that had large Native American architecture (i.e., earth mounds) or were thought to be substantial villages. The research design for the overall Wallace project was to “direct project activities toward identifying the nature of human institutions” within the Oconee River valley, with institutions defined as “configurations of social organizations which pattern life within human groups” (Fish and Hally Reference Fish and Hally1983:6–7). In this sense, our research continues with this line of thinking, albeit from a view that does not rely on the neoevolutionary thinking and typologies that have overly influenced our understanding of Native American governance. Our research with the collections from Cold Springs began with digitizing and examining the extant, unpublished records and artifacts to understand the timing and tempo of the development and use of the site.

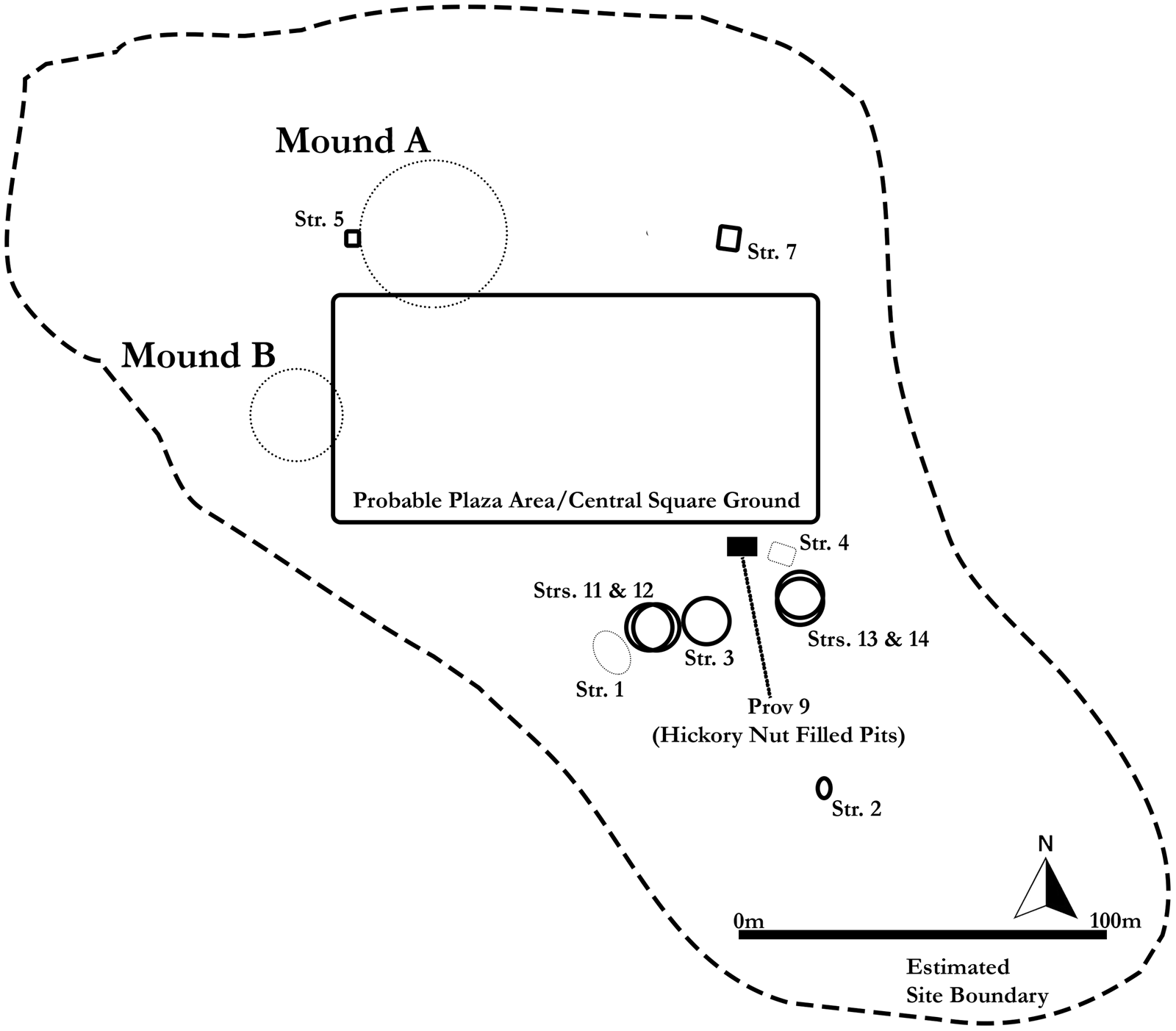

The 1970s excavations at Cold Springs focused on understanding site layout (covering ca. 4.4 ha) and the interior form and construction of the two earthen mounds: Mound A (50 m in diameter; 2.8 m tall) and Mound B (40 m in diameter; 1.6 m tall; Fish and Jefferies Reference Fish and Jefferies1983). Stripping of approximately 4,700 m2 of the “off mound” area and excavations of both mounds (Supplemental Figure 1) produced thousands of post molds, indicating numerous structures that the inhabitants built both on and off the mounds (Fish and Jefferies Reference Fish and Jefferies1983).

Ceramics and radiocarbon dates (discussed below) from both of the mounds place them as being constructed prior to AD 1000. The occupants of Cold Springs constructed both of these mounds in stages, building structures atop their successive summits (Jefferies Reference Jefferies and Hally1994). Excavations also identified larger posts (ca. 50 cm in diameter) that were not part of structures; these were likely marker posts, perhaps carved with intricate designs or effigies, much like wooden paddles used to stamp designs on pottery found at Cold Springs. Such large posts have also been found at later post–AD 1000 mounds (Jefferies Reference Jefferies and Hally1994). The inhabitants constructed both mounds with sediments of different colors, much like the later platform mounds that become ubiquitous across the landscape (Sherwood and Kidder Reference Sherwood and Kidder2011).

Archaeological surface collections and testing recovered both pre– and post–AD 1000 ceramics. Stripping of the site revealed at least eight structures in an area just southeast of the two mounds (Figure 3). Two of these are distinctive subrectangular wall-trench-type structures that date to the post–AD 1000 period. The other six remained undated up to the new radiocarbon dates we present in this study. Of the six structures, three are small, and they are less than 5 m in diameter. The other three are massive circular structures that are approximately 12–15 m in diameter. Each of these structures has large associated pits, some filled with hickory nuts, and what appear to be interior support posts and other smaller posts that could have supported benches, much like those identified at sixteenth-century council houses (Shapiro and Hann Reference Shapiro, Hann and Thomas1990; Figure 4). This is especially apparent in Structure 12, which has what appears to be a smaller semicircular row of post against the wall facing a “V”-shaped line of posts that point toward the interior. This could have been an opening for outside viewers. Interestingly, this possible opening and the “bench” seating face Mound B at the site. There are also two small squarish patterns of posts on the roughly northeastern and southwestern sides that may be special seating of some sort. There also appears to be a possible bench post mold line in Structure 3, but this is less clear (Figure 4). It is possible that some of these posts represent rebuilding episodes or repair—again, a pattern observed in the construction of other documented council houses (Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Marquardt, Walker, Roberts Thompson and Newsom2018); however, given the discreet patterning and the fact that these structures were rebuilt in adjacent areas, we think this is unlikely for Structure 12. Consequently, given their form, location in relation to other settlement features, and other similarities in construction to council houses recorded in the southeastern United States, we argue that these large structures at Cold Springs represent this specific inclusive form of Native American architecture.

Figure 3. Plan of excavations and proveniences at the Cold Springs and architectural features identified through these investigations. (Produced by Jacob Holland-Lulewicz.)

Figure 4. Plan of council-house structures and associated features at Cold Springs with associated radiocarbon determinations also indicated. Structures 12 and 3 have interior post molds that are possible bench supports (gray-colored posts). (Produced by Jacob Holland-Lulewicz.)

The overarching site plan, excluding the post–AD 1000 houses, includes two adjacent platform mounds with attendant summit structures and a series of large council house(s) located some 70 m away, likely separated from the mounds by an open plaza area, with a few smaller outlying structures adjacent to the mounds and the open area (see Figure 3). As detailed in the introduction, such an arrangement is seen not only in post–AD 1000 mound-plaza complexes but also among seventeenth- and eighteenth-century—and modern—Muscogee ceremonial grounds (see Figure 2).

Radiocarbon Dating

Prior to our new dating project and reanalysis of the Cold Springs collections, little information existed regarding the absolute chronology for the mounds and nonmound structures. Previously, archaeologists obtained six conventional radiocarbon dates that we include here in our analysis. We exclude one date that was obtained on an ancestor (i.e., human remains), because this is not in keeping with ethical standards. To better understand the chronology of both the mounds and the structures, we ran a total of 44 new AMS radiocarbon dates from across the site, which makes it one of the best dated early mound centers in the southeastern United States (Supplemental Tables 1–2). Dates were then assessed within a Bayesian interpretive framework using OxCal 4.4 and IntCal20 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Ramsey, Butzin, Cheng, Lawrence Edwards and Friedrich2020) to establish the exact chronology of construction for both mound and nonmound architecture. Modeled dates and ranges are presented in italics and rounded to the nearest 10.

The primary model incorporates all archaeological information (e.g., contextual, stratigraphic) into the Bayesian interpretation of the Woodland component radiocarbon dataset. Of the 50 available radiocarbon dates, six are from the later twelfth- to thirteenth-century component, four are identified formally as outliers, and one yielded from human remains has been excluded, resulting in 40 dates used to model the primary component at Cold Springs Supplemental Codes 1–5). Four dates that were identified as outliers via general outlier analysis (Alternative Model C, Supplemental Code 4) have been removed. After removal of outliers, a charcoal outlier model was applied to account for minor variances in dates yielded from charcoal samples. In total, four alternative models were built using varying applications of outlier analyses and the removal or inclusion of particular dates statistically identified as outliers. Across all five models, modeled starts, ends, and spans for the overall occupation, as well as each of the modeled settlement features (e.g., council houses, mounds, etc.) experience no substantive changes. All models yield modeled date ranges that fall within one or two decades of one another (see Supplemental Codes 1–5 for alternative model descriptions, results, and OxCal code).

The primary model exhibits an Amodel of 73.6 and an Aoverall of 70.2, both above the accepted threshold of 60. Modeled start and end boundaries for the overall occupation as well as mound and nonmound features are presented in Figure 5 and Supplemental Table 3. The modeled start boundary for the occupation, at the 68% confidence interval (or the 1σ range) is cal AD 500–550, with a modeled end boundary of cal AD 650–700 and a modeled span of 110–160 years. The model places the start of the Mound A construction at cal AD 520–560 and the end at cal AD 570–600, with a span of 20–60 years. Similarly, the model places the start of the Mound B construction at cal AD 520–560 and the end date range of mound construction at cal AD 600–650, with a span of 50–100 years. There is considerable overlap in both construction and use of Mound A and B, and they are likely contemporaneous.

Figure 5. OxCal plot of modeled start and end boundaries for pre–AD 1000 mound and nonmound settlement features at Cold Springs. (Produced by Jacob Holland-Lulewicz.)

The model places the start for the construction of the large round structures (see Figure 4) at cal AD 520–560—the same start range as each of the two mounds. The modeled end boundary for the use of the round structures is cal AD 650–680, which is slightly later than each of the mounds. The model indicates that the series of large round structures was used for approximately 90–130 years, likely throughout the majority of the occupation. It remains unclear whether or not each set of roundhouses was used contemporaneously or sequentially, given that Structures 13 and 14 yield modeled dates that fall between cal AD 530 at the earliest and cal AD 640 at the latest, whereas Structures 11 and 12 yield modeled date ranges from cal AD 610 and cal AD 670. Furthermore, structure identifications were made in the field and remain difficult to reexamine. Although it is possible that Structures 13 and 14 represent roundhouses rebuilt or repaired, Structures 13 and 14 may actually represent a single structure with complex interior supports or benches. Consequently, in reevaluating original identifications, there were at most five large round structures, and at minimum three. These structures may have been sequentially rebuilt or used contemporaneously. A more robust dating effort aimed at these structures alone may help to unravel these histories.

Finally, for a series of large pit features and a single structure (Structure 2, Provenience 10) located south of the large round structures (see Figure 3), the model yields a start range of cal AD 550–620 and an end range of cal AD 610–660, coeval with all other architectural features. It is possible that these structures—and other structures like it located near the mounds (see Figure 3)—were temporary housing for groups gathering for ceremonies and councils at the site, much like the outlying occupation found at Kolomoki, another contemporaneous mound center in Georgia (Pluckhahn Reference Pluckhahn2003). In addition, two dates from a series of large, hickory-nut-filled pits located just north of the large round structures (see Figure 3) yield modeled ranges of cal AD 600–660 (UGAMS-48292) and cal AD 600–650 (UGAMS-48290).

Discussion and Interpretation

In sum, the Cold Springs site is important in three key dimensions. First, our new dating of the site firmly places both of the platform mounds in use between cal AD 550 and 650. Their continued rebuilding, along with multiple associated summit and submound structures and large “marker” posts, indicates core traditions that are observed much later on in the region. Second, our identification of multiple council houses indicates that, like platform mounds, these too have their roots in the pre–AD 1000 era. Finally, the overarching layout of the architecture, with its two platforms and large council houses with an intervening plaza area, is similar not only to later pre-European Native American sites but to “historic” Creek ceremonial grounds, and, indeed, to contemporary Muskogean communities, such as the people of the Muscogee Nation in Oklahoma today. If such similarities in architecture and settlement indicate considerable continuity in governance, then we argue that archaeologists have relied too heavily on fragmented colonial documents regarding chiefly authority that privilege the role of individuals (i.e., the elite) and their connections to platform mounds over the group collective in Native American institutions of governance. Although likely expressed in a wide variety of ways, Native Americans of the Oconee Valley established institutions of collective governance by at least AD 500, specifically the institution of the council, which continued not only in the region but in the valley itself into the 1700s at multiple sites with similarly documented large circular structures (Williams Reference Williams2016).

As Kowalewski and Birch (Reference Kowalewski, Birch, Bondarenko, Kowalewski and Small2020:33) state, although “council meetings cannot be excavated,” structures for hosting such meetings that represent the materialization of the institution of the council can be. Councils, like many institutions, are explicitly social institutions by their very nature in that they require roles and labor, they are generational, and they rise to meet the specific needs of the group (Bondarenko Reference Bondarenko, Bondarenko, Kowalewski and Small2020:10). Given these characteristics, we argue that council-based institutions were a key part of governance in the region, emphasizing consensus building and collective action. Furthermore, we argue that, given that such institutions functioned throughout the post–AD 1000 period and well into the “historic” era, the roles within these institutions—such as Mekko and other leadership roles—likely also have long histories. The implication of tying the emergence of chiefly roles to the emergence of communal institutions of governance is that the individuals occupying such roles were borne from institutions that granted them very limited personal power, a perspective that runs counter to many views of post–AD 1000 chiefly dynamics (for a summary, see Muller Reference Muller1997), but one that is in keeping with Muskogean scholarship (Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri2001; Howe Reference Howe1999). Consequently, in our view, there are more similarities and continuity in governance that reflect communality and collective processes in the region, beginning by at least AD 500 and continuing through today, than there are differences.

That collective institutions of governance emerged in the millennium prior to AD 1000 is not a new idea, and a variety of ideas have been put forth to explain how these operated (e.g., sodalities, clans, etc.; see Pluckhahn Reference Pluckhahn and Alt2010). Clan and lineage systems are especially important to note here because they likely form some of the longest-lived institutions of the Southeast, which articulated with other key institutions (Holland-Lulewicz et al. Reference Holland-Lulewicz, Conger, Birch, Kowalewski and Jones2020:8), such as the council houses. Clan systems among the Creek Confederacy were nonlocalized, and members lived among various towns (Swanton Reference Swanton1928:114–120). Clans (em vliketv [im-a-leyk-itá]) also helped determine roles and responsibilities within communities, as well as where one sits (enliketv [in-leyk-itá]) in council (Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri2001:76; Historic and Cultural Preservation Department, Muscogee [Creek] Nation, personal communication 2021). Therefore, in a dispersed settlement system such as the Oconee Valley, clans would be extremely important institutions, particularly during council gatherings and, for this reason, clan affiliation would have helped to structure the roles and participants during councils. And, although we cannot excavate a “clan” system, we argue that such institutions were likely part and parcel of regularized councils. In fact, some of the larger posts erected on the mound at Cold Spring could be interpreted as clan markers, like those excavated elsewhere in the Southeast, such as the large owl effigy post recovered from Hontoon Island, Florida (Ostapkowicz et al. Reference Ostapkowicz, Schulting, Wheeler, Newsom, Brock, Bull and Snoeck2017). More broadly, the regional spread of some of the institutions associated with platform mound construction, and possibly council houses as well, may have been engendered by social institutions such as clans or subclans. Pluckhahn and colleagues (Reference Pluckhahn, Wallis and Thompson2020:39) model the northern expansion and spread of platform mounds and villages throughout the region beginning around cal AD 535 and 640 and ending around 660 and 730, which is the exact time that Oconee Valley populations occupied Cold Springs.

Of course, it is likely that collective governance existed prior to the time of the occupation at Cold Springs; however, we suggest that, by AD 500, council-based institutions that focused on consensus and democratic ideals emerged in the Oconee Valley and became regularized. People of the valley materialized these ideals and institutions through the construction of council houses. Although such processes of communal decision making and collective action certainly existed prior to such materialization, likely as situational arrangements, the appearance of the council house suggests an institutionalization of these arrangements that would have cross-cut and integrated the decision-making processes nested in other various institutions (i.e., clans, lineages, households). And, although we suggest that key roles—such as the Mekko—also likely were present, the overarching theme of governance and of such roles was inclusivity and collective choice. This perspective is not far from the arguments posed by King (Reference King2003:60, 112–113) for the Etowah polity, where the founding principles were thought to be more communal and integrative rather than individualizing.

Although it is difficult to point to one driving reason why people began constructing council houses, we can nevertheless discuss the nature of the social context and some of the operational reasons for the development of such institutions. First, based on the nature of social networks from AD 500 on, it appears that clan affiliations were part of the underlying social fabric that connected various communities (Lulewicz Reference Lulewicz2019). Second, across the valley from AD 500 through the 1700s and before, communities were dispersed across the landscape with relatively few large villages but with many small settlements in close proximity to one another. Given that the valley held dispersed, but connected, families across the landscape, there certainly would have been communally held lands (e.g., common pool resources) because households could not produce everything that they needed from small plots adjacent to a house. They would have needed to hunt, forage, and harvest across the landscape, encountering, cooperating, and interacting with others on a number of social levels. Disputes and disagreements are inherent in such systems and require some sort of decision-making process regarding not just dispute resolution but the future of use rights and collective choices related to the management and stewardship of the landscape and attendant social relationships (see Schlager and Ostrom Reference Schlager and Ostrom1992). Such decisions would extend beyond the interest of a small group of individuals, or singular or infrequent moments in time. Consequently, governance would necessitate generational knowledge (i.e., elders), and rules of choice and use rights so that enduring interests of the group would be protected from any threats to cooperation (see Roscoe Reference Roscoe and Carballo2013).

Council-based institutions would have provided the forum to discuss, debate, and build consensus, and the broad participation in such institutions would also mean that oral histories concerning resources, land rights, use rights, and the like often held by elders could be shared in an open forum. The active sharing of knowledge and its enactment in a highly structured public space would serve to dampen individual attempts to garner benefits at the exclusion or cost to the group as a whole (see Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016). In addition, because councils were an open forum where there was broad participation, they also would have served to instill confidence in the institution itself, which is critical to the success of cooperation and its overall endurance (see Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016). Feasting and ceremonies, such as the “Busk” ceremonies of the 1700s held at council houses (Williams Reference Williams2016), likely intensified, reified, and solidified these cooperative relationships, similar to processes observed in other areas of the Americas (Stanish Reference Stanish2017; Stanish et al. Reference Stanish, Tantaleán and Knudson2018).

Some researchers may take exception to our use of democratic institutions over the favored anthropological term “egalitarianism.” We argue that in addition to not fully capturing the complex relationships we document here, this term also downplays the sophistication of Native American governance by linking it to neoevolutionary terms and typological categories that lessen the significance of Native American histories in the development of these forms of governance globally. Democratic institutions, in general, provide an avenue for broad engagement with its citizens in governance; decision making is accorded transparency in terms of how it operates; and it is a process that all participants can understand and that allows, to varying degrees, participants to have a voice in governance (see Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016). Institutions with these characteristics are powerful “counterweights” to individuals who are either in positions of power or seeking it out for their own gain (Blanton and Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016:156). In sum, we argue that council houses represent, very explicitly, collective democratic decision making, as we detail above. And although democratic institutions represent some of the most difficult cooperative endeavors to maintain, we suggest that the particular problems that often crop up in such situations were solved by Indigenous groups relatively early in the region, allowing them to persist for over 1,500 years, with modern analogs still constructed today in Oklahoma and elsewhere (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Photograph of the Phillip Deere Roundhouse in Okemah, Oklahoma. (Photo courtesy of Historic and Cultural Preservation Department–Muscogee [Creek] Nation.)

Although we do not have the space to fully consider the implications of this study on ideas regarding the nature of colonial invasions, entanglements, shatter zones and the like, we point to some implications that suggest future consideration by researchers (see discussions in Ethridge and Shuck-Hall Reference Ethridge and Shuck-Hall2009; Foster Reference Foster2007). Specifically, we emphasize here the continuity of specific institutions over time, and we argue that such endurance requires a rethinking of the way we traditionally consider Native American political life in the American Southeast—a view that offers a more complicated perspective. Specifically, our perspective is that the institutions of councils have a long history of integrating people of dispersed populations across both extensive regions and local communities. In fact, the council as an institution may have been particularly resilient in mediating the challenges faced by the movements and upheavals that the Muscogee people, and others, experienced from the sixteenth century onward. This does not mean that we think change did not occur. Rather, we believe that emphasizing change as envisioned by some (e.g., collapse, shatter) misses and downplays internal histories as simply reactions to or against external forces.

Although these external forces (especially colonialism) were critical, they by no means determined outright the course of Indigenous histories. Consequently, we argue that we need to engage with the histories of such institutions on their own terms and not over-reify particular inflection points to the detriment of understanding the continuity and endurance of these supposedly shattered societies, traditions, and histories. In other words, what is often left out in such debates are the internal decisions, choices, and actions of the people who created and experienced these institutions. In our view, continuity does not mean an unchanging institution, but a flexible one with historic ebbs and flows. As Panich (Reference Panich2020:10) notes, to move beyond the simple “catastrophic colonialism” viewpoint “requires moving beyond a narrow focus on demographic and cultural loss.” And, as we note below, a rethinking of how we trace continuity has direct impacts for contemporary communities. Indeed, “continuity does not require stasis” (Panich Reference Panich2020:5).

On a final note, our research at Cold Springs has implications for modern tribal concerns and issues. Specifically, our research brings up the issue of what exactly continuity constitutes. Land claims, resource use rights, the cultural affiliation of ancestors and funerary belongings under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), and other similar issues between Tribal and national governments rely on the establishment of cultural connections from a wide variety of information sources, including oral histories, treaties, and the like (Martindale and Armstrong Reference Martindale and Armstrong2019). Archaeological information, particularly with recent changes to NAGPRA laws, plays an increasingly critical role in these debates around issues of affiliation. Traditionally, archaeological thinking on continuity, especially in the southeastern United States, has relied heavily on material culture styles (e.g., pottery decorations) and historic records. We argue that archaeological information that focuses on institutional traditions provides key information on cultural continuity—likely more so than simple histories of material culture styles. Our logic is that institutional traditions (e.g., council houses) are part of lived experiences of past peoples and were important to structuring their lives. Therefore, they can be more durable measures of cultural continuity than artifact styles, especially when we are considering cases that involve deeper time frames. We argue that this is especially true for such institutions that continue to have modern expressions among descendent communities. If archaeologists are willing to use oral histories, stories, tribal histories, and other such sources to interpret the past, then they must also be willing to acknowledge—in a real way—living peoples’ connections to the archaeological record. Archaeology cannot have one without the other.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Anthropology, the Laboratory of Archaeology, and the Center for Applied Isotope Studies at the University of Georgia (UGA). We also thank Stephen Kowalewski, Gary Feinman, and Amanda Roberts Thompson for their previous reading and thoughts on this article. Research at Cold Springs was supported in part by USDA Forest Service. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA Forest Service. We thank American Antiquity editor Debra Martin, the three anonymous reviewers, and Maggie Spivey-Faulkner for their comments, which improved the overall quality of this article.

Data Availability Statement

All physical archaeological materials (i.e., artifacts, samples, paperwork, digital data, photographs, drawings) are curated at the University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology for future reference. These data are available upon request from this laboratory. Any research request should also be done in conjunction with descendant community consultation. All data relevant to the arguments presented in this study can be found in the manuscript and supplemental materials.

Supplemental Material

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2022.31.

Supplemental Figure 1. Locations of all excavations and proveniences at Cold Springs.

Supplemental Table 1. Radiocarbon data from Cold Springs.

Supplemental Table 2. Modeled ranges for Cold Springs dates.

Supplemental Table 3. Modeled start and end boundaries for the Cold Springs occupation and settlement features.

Supplemental Code 1. Primary Model.

Supplemental Code 2. Alternative Model A.

Supplemental Code 3. Alternative Model B.

Supplemental Code 4. Alternative Model C.

Supplemental Code 5. Alternative Model D.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.