IntroductionFootnote 1

This regionalization of Africa modifies and expands upon the division of Africa into eight coastal regions underpinning Philip D. Curtin’s Reference Curtin1969 monograph, The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census. Footnote 2 The subsequent adoption of Curtin’s geographic schema in Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database – developed by David Eltis and collaborating team who have assembled data for over 36,000 voyages – has virtually enshrined Curtin’s regions into the historiography of Africa and the Atlantic world.Footnote 3 Despite criticisms of those coastal regions, scholars and students alike rely on its structure in analyzing and understanding the displacement of over 12.7 million people from some 180 ports of embarkation along the African coast.Footnote 4 Curtin’s and Eltis’s Atlantic-facing regions, however, do not adequately address the relationship with internal African population movements or with other external migrations that went overland into the Middle East, across the Mediterranean and Red Sea, as well as into the Indian Ocean world.Footnote 5 The recent proliferation of digital projects and the biographic turn in the study of African diasporas necessitates re-regionalizing the continent for purposes of database construction and GIS mapping to allow for a deeper analysis of other migratory patterns beyond the Atlantic. Scholars have been amassing data on Africa in new and innovative ways to show complex linkages within Africa and the rest of the world. Due to the uncertainty of ample data related to this particular field of study, a new regionalization could improve methods for archiving oral sources, written accounts, imagery, 3D archeology, and other multimedia objects related to people and periods from before c. 1900.

Developing new African regions requires a methodological approach that must be sensitive to the history of the continent, especially surrounding the partition of Africa during colonization.Footnote 6 Our methods purposefully avoid “digital colonialism,” which suggests the sectioning of Africa for political, or even, academic purposes other than to assist in the organization of data. Rather, we seek to find a more common, neutral ground in which to coordinate building datasets around a more historically considerate geographic framework. In digital humanities terms, regions are simultaneously units of analysis and categories within a controlled vocabulary. They serve as data containers or “buckets” into which data can be allocated for the classification, aggregation, linking, and dissemination of open source information. In computational terms, a “data bucket” refers to data “divided into regions.”Footnote 7 When talking about migrations, however, we prefer to use “regions” rather than put data as the representation of people into containers. As a single value in a dataset, large amounts of other geopolitical data generally apply within a region, as they constitute but one of many layers, levels, and columns in a data hierarchy. Other geographic data include political states, territories, provinces, cities, towns, villages, trade routes, markets, streets, buildings, and perhaps even intersections where people met. Depending on the project, data are usually flexible enough to be assigned into as many “data buckets” as needed.

Attempting to regionalize pre-colonial Africa has proven a challenge, which is why it has become important to revise a map and controlled vocabulary previously published in History in Africa; and subsequently debated at the African Studies Association conference in 2019.Footnote 8 The amended regions being proposed here are meant to be free from the constraints of European slave trading terminologies, colonial borders, and modern-day countries whenever possible.Footnote 9 Our intention is also not to establish a regionally static or timeless map. We have considered and debated the uneven ebb and flow of African polities and ethnicities as they shifted and interacted within changing continental ecosystems, elevations, or along sources of water over time.Footnote 10 Environmental and political events affect geographic landscapes, which for Africa – like the rest of the planet – have undergone historical climate changes through flooding, dams, disease, drought, deforestation, desertification, erosion, agriculture, warfare, and migration. It is worth emphasizing that our intention is specifically intended to establish a controlled vocabulary for database construction. We are not suggesting that terminology commonly used in historical reconstruction be replaced, although careful definition of terms is certainly to be encouraged.

We fully acknowledge our geographic schema might be contentious, perhaps among pan-Africanists opposed to political and ethnic fragmentation; or indeed, others who treat North Africa as an extension of the Middle East; or still others who fail to grasp our purpose in establishing a neutral controlled vocabulary for technical reasons. After all, there are many ways to map a society, while geography and identity are not always coterminous. And inevitably, regional boundaries have a tendency to divide political or ethnographic groupings, meaning they can never be “perfect.” It is imperative to keep in mind, however, that we have theoretically designed these regions to be approximate areas with flexible boundaries, as Patrick Manning has previously done to estimate populations between 1850 and 1960.Footnote 11 We are also aware that linguistic and cultural mapping has a long tradition, perhaps best represented in the work of George Murdock and the foundation of the Human Relations Area Files (https://hraf.yale.edu/) in cultural anthropology at Yale University.Footnote 12 These efforts led to the development of AfricaMap (http://worldmap.harvard.edu/africamap/) by Nathan Nunn and undoubtedly have had an important influence on understanding the cultural and linguistic contours of Africa, although from the perspective of historical reconstruction have the disadvantage of being ahistorical.

While what we attempt might be contested, there are indigenous traditions of map making or representations of space before the colonial period. For instance, Jamie Bruce Lockhart, Paul Lovejoy, and Camille Lefèbvre have presented indigenous maps of political states and trade routes, such as those drawn by officials of Muhammad Bello, the second ruler of Sokoto, and documented by Hugh Clapperton in 1825 and 1827.Footnote 13 Similarly, it is evident that in many circumstances European maps of Africa’s interior geography often derived from testimony of one or several African informants who provided that information. For example, Giacomo Gastaldi created and published the map “Prima Tavola” in 1554 based on the descriptions of al-Ḥasan ibn Muḥammad al-Wazzān al-Fāsī, aka Joannes Leo Africanus; or “Kaart van de Goudkust” from 1629 held in the Algemeen Rijksarchief, Den Hague.Footnote 14

We do not presuppose that all projects, digital or otherwise, should adapt this vocabulary, but we hope to encourage reflection on how data are designed and organized. These regions may have unforeseen ramifications for which we have not entirely allowed. We realize how our attempt might affect pre-established digital projects, such as Voyages. Footnote 15 Ultimately, we are introducing new regional terminologies and adjusting coastal boundaries. Reinterpreting how we talk about Voyages would mostly refine the language of what has already been an evolving quantitative analysis of the transatlantic slave trade.Footnote 16 Beyond Voyages, we equally consider how the proposed regions might help in coordinating overlapping digital projects, such as ones focused on abolition, baptisms, biographies, fugitives, ownerships, and other land and maritime migrations beyond the Atlantic. In the long run, it may also help human genome projects to group data, such as 23andMe.com, Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org, among others, which have designed their own African regional data containers. A recent study on the “genetic consequences” of the slave trade in the Americas “merged contemporary administrative borders to match all major slave trading regions during the transatlantic slave trade except South East Africa,” while also having “split Nigeria into western and eastern states along the Niger River.”Footnote 17 Such attempts not only demonstrate a pressing need to organize data into geographic containers, but also address the complexity of forming regions for pre-colonial Africa. Consequently, we still want to stress how our geographic schema might help better understand demographic developments in pre-colonial Africa, while we specifically seek to avoid reinforcing Africa’s asymmetrical relationship with other parts of the world. After all, maps have the power to capture people’s attention and shape future developments.

Although we may not have the foresight to predict how these regions might impact the field and beyond, we can still imagine other regionalizations unique to the scope of individual research projects. This proposal may simply be a starting point for researchers interested in organizing and archiving historical data related to African peoples, places, events, sources, and even ethnographic classifiers, including documented ethnonyms and toponyms.Footnote 18 As technologies improve, historical datasets linked to digital archives might be searched through interactive maps, which could be filtered using tools such as “select polygon.” Cartographically based, digital archives are being built using geographic information systems (GIS) and statistical software (R), which for example, can illustrate instances of intra-African conflict alongside slave ship departures on an annual basis.Footnote 19 In time, data points, such as ships, caravans, cities, towns, and even people, will link into caches of primary source multimedia for deeper analysis. It is equally possible to map ethnonyms and toponyms on a regional and temporal basis too.Footnote 20 These methods and technologies will continue to come into focus through the steady progression of our current digital age.

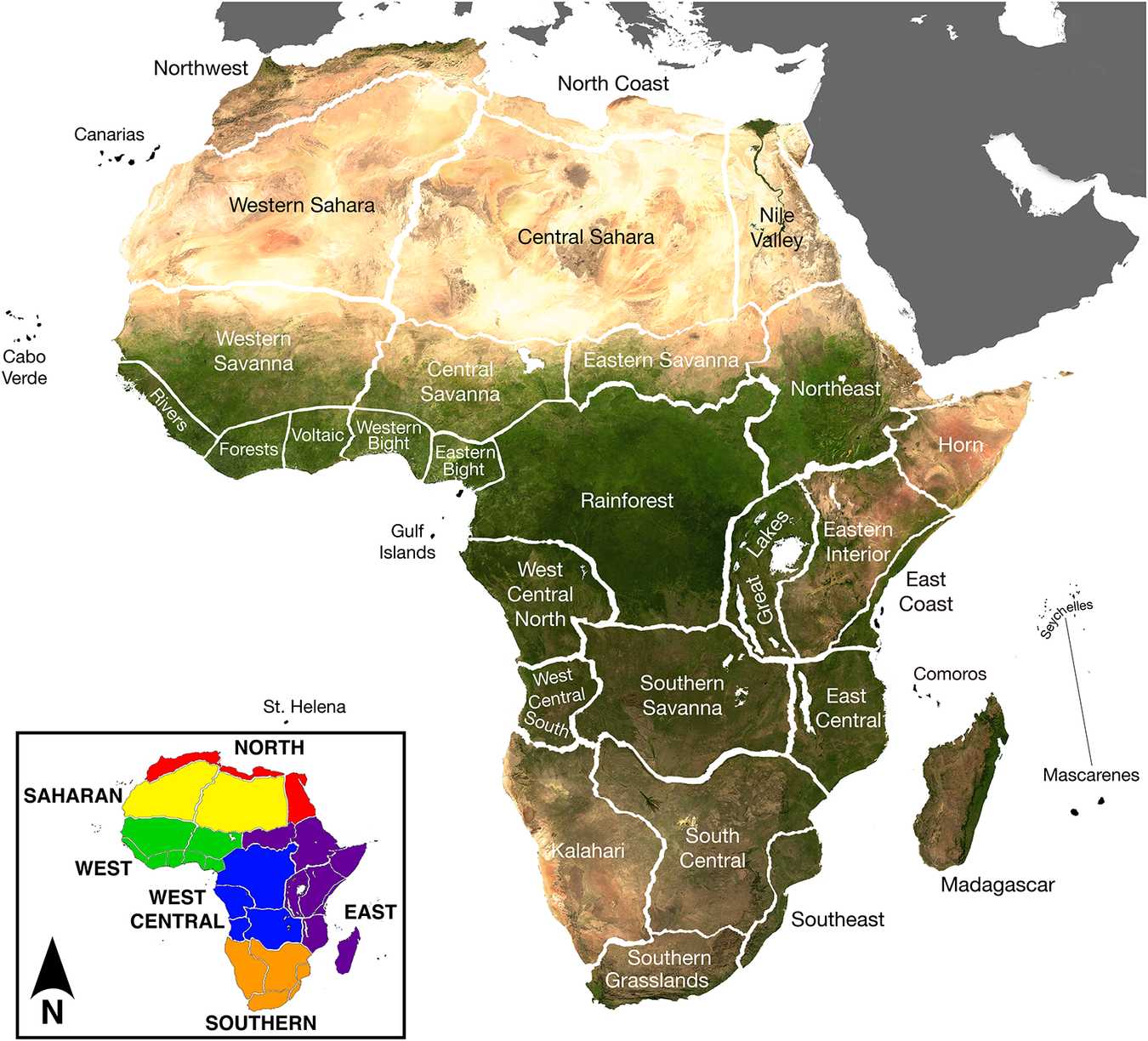

With these points in mind, the remainder of this article provides a rationale to a regional map and controlled vocabulary designed for digital research on pre-colonial African history. This data hierarchy starts with the continent of Africa; and branches into six broad regions: North Africa, Saharan Africa, West Africa, West Central Africa, East Africa, and Southern Africa. Subsequently, these broad divisions separate into another 34 sub-regions, which include clusters of offshore archipelagos and islands. Due to oftentimes laborious data entry processes, we elected to decrease the number of characters for each label as much as possible and use abbreviated terms that are easy to understand and translate (see Map 1. and Table 1). Again, the regional map and controlled vocabulary presented here replaces the previously published version from 2019. However, we reference the earlier article throughout this paper in circumstances wherein the sub-regions remain largely unchanged. It is therefore recommended to readers to use the amended map while cross-referencing the historiography in the initial article.

Map 1. Regional Map of Africa for Linking Open Source Data

Table 1. Controlled Vocabulary Hierarchy for the Regions of Africa

African Regions and Sub-Regions

It is necessary to emphasize again the flexibility of geographic “regions,” which, by definition, have boundaries which generally overlap with one another. In other words, regions have fluid or fuzzy borders, which shift depending on perspectives, beliefs, and opinions. As data in a hierarchy, regions are a value, a category, a container, and a column in a spreadsheet or database. The remainder explains six broad regions and 34 sub-regions:

North Africa

This broad region includes the northern-most territories of the continent from the Atlantic along the shores of the Mediterranean to the Nile Valley.Footnote 21 From our previous attempts, we have made substantial revisions to this broad region based on the separation of the Sahara desert, dividing the northern coast into two areas, adjusting boundaries of the Nile valley; and adding the Sinai Peninsula, and Canary Islands.

The Northwest sub-region overlaps with the Maghreb and extends along the northern coast of Africa to the west of Tripoli.Footnote 22 As the most important destination and transit zone of enslaved Africans via trans-Saharan traffic, it included the High Atlas mountains in modern-day Morocco to the Tell Atlas range, which extend into western Tunisia. The southern border includes the ruins of Sijilmasa located in the large oasis of Tafilalt, which was once a thriving terminus of trans-Saharan caravans. Its numerous ports on the Atlantic include Agadir, Essaouira, Salé; and on the Mediterranean, they extend from Tangiers to Tunis. These ports, which are too numerous to list here, were centers of transit of enslaved Africans across the Mediterranean into Europe. Since the time of Roman occupation, the region has been predominately Amazigh (Berber) including Almoravids, Almohad, and other Muslim states.Footnote 23

North Coast begins to the west of the Mediterranean Island of Djerba, on the boundary between modern-day Tunisia and Libya. To the southwest, it is bordered by the town of Wazin on edge of the Nafusa Mountains; the south-central oasis of Waddan, on the border of the Sirt Desert to the north, and the Black Mountain to the south; the Great Sand Sea to the south; and the Qattara Depression in the east. The region features the port of Tripoli, and on the eastern coast, a region encompassing the Green Mountains known as Cyrenaica and the port of Benghazi. Tripoli was one of the most important centers of the trans-Mediterranean slave trade.Footnote 24

Nile Valley includes modern Egypt, the Sudan, and part of South Sudan. The Sinai Peninsula, which is part of modern-day Egypt, is often considered to be the desert boundary between Africa and Asia. The Mediterranean is the northern border, with its major port of Alexandria, and the eastern Sahara between the Nile and Red Sea. To the west of the Nile lies the Western Desert, also known as the Libyan Desert, with its oases of Abu, Bahariya, Dakhla, Farafra, Kharga, Minqar, Mut, and Selima. It has the oldest trans-Saharan donkey and camel caravans, and riverine routes, including a well-known forty-day trail (darb al-arbaʿīn). The valley extends to the Red Sea, just south of Sawakin, which was a major port to the Arabian Peninsula and beyond.Footnote 25 The Nile runs beyond Dongola in the southwest to around Aswan near the fifth cataract, which has been a political and linguistic border from very ancient times.Footnote 26

Canarias are an archipelago of islands centered at Tenerife, Fuerteventura, and Gran Canaria, among other smaller islands and islets. Long after the Almoravid, Almohad, and other Muslim states occupied parts of the Iberian Peninsula, Spanish kingdoms conquered the islands in 1402. However, indigenous groups, collectively known as Guanches, already inhabited the island and perhaps share a common ancestry with Amazigh groups, and later, with other peoples from Europe, most especially Portugal and Spain.Footnote 27

Saharan Africa

In the 2019 article, we had grouped the world’s largest desert into North Africa.Footnote 28 However, the Sahara is a vast region unto itself and represents about a quarter of the entire continent’s total land mass. It can be split in two for organizing data related to trans-Saharan trade.Footnote 29

Western Sahara borders the Atlantic to the west. The northern border encompasses the two large desert plains of the western and eastern Grand Erg; and near the Oued Noun with its market of Guelmim, which is known as the westernmost “door of the Sahara.” This region includes the oases of Ghardaïa, Gourara, Ouargla, Touat, and Tidikelt. Like most Saharan oases, these were centers of date palm cultivation, and significant destinations or transit zones for enslaved Africans originating in the Sahel and savannas. Its eastern border lies just to the west of the Ahaggar Mountain range. The southeastern limits include the city of Kidal and nearby ruins of Essouk-Tadmekka, now in northern Mali. It also included the salt mines of Idjil, Taodenni, and Teghazza, which generated currency for slave transactions.Footnote 30

Central Sahara includes the desert’s mountain ranges of Ahaggar, Aïr, and Tibesti; and extends westward to the Gilf Kebir plateau. The northeastern border holds the oasis of Siwa, an ancient gateway to Egypt, and the markets Awjila and Jalu. The Tuareg heartland included the Fezzan region, a historic desert epicenter of trans-Saharan traffic, circulating in all directions at least since the time of the Garamantes. Oases include, Ghat, Khufra, Murzuk, Ubari, Zawila, and in the north, Ghadames which absorbed enslaved laborers from the Sahel. To the south, key centers of trade are Agadez, Takedda, and the salt and date export region of Kawar, with its main oasis town at Bilma.Footnote 31

West Africa

This broad region incorporates much of Curtin’s coastal distribution for aggregating trans-Atlantic slave trade data from around the Senegal River southward to the Bight of Biafra; and includes Cabo Verde and Gulf islands. Our labels, for the most part, maintain a short character limit for time-consuming data entry processes. It has been difficult to determine neutral terms for sub-regions of West Africa everyone might easily agree upon. In fact, it was far simpler to identify terms we did not want to use, such as “Guinea,” which was of Amazigh origins. Since 1140, az-Zuhri, an Arab historian, used Janawa to refer to a “land of the blacks,” and whose capital was Ghana. In Tamazight, “land of the blacks” translates as akal n-guinamen (sing. aguinaw), which is synonymous with bilad as-sudan. In Sanhaja, the root word gnw means “black”; and in Zenaga, Guinawn (sing. Ignwi) means Serer and Wolof in particular. In Tuareg, iguinawin means a “mass of dark clouds.” Since the fourteenth century when the Iberian peninsula was occupied by Africans, the Portuguese adopted and mapped the term pervasively to refer to the continent; and by the fifteenth century in Rome, al-Ḥasan ibn Muḥammad al-Wazzān al-Fāsī used the words “Jinni” and “Jenne” interchangeably with “Guinea” and “Djenné,” a former kingdom and city located on a tributary of the Niger River, now present-day Mali.Footnote 32 Today, three modern-day countries use the term too. In the Americas, “Guiné” generally identified enslaved people as coming from anywhere in Africa. In a similar vein, we have eliminated usages of “Windward” and “Gold Coast,” which were longstanding slave trading terms describing stretches of coastline; the former being windward of the later and where Europeans built forts for the gold and slave trades. Likewise, “Benin” causes confusion because it was a kingdom at the western end of the Niger delta and now a country to the west of Nigeria with historical roots in Dahomey. “Biafra” was the name given to a territory in Nigeria that attempted to assert its independence in the Nigerian civil war (1967–1970); and modern-day Senegal and the Gambia creates misunderstandings about “Senegambia.” Therefore, amendments of the broad West African sub-regions have required deeper contemplation and finding a more neutral nomenclature, which is difficult. Again, we neither assume everyone will agree on these terms, but we could not easily devise alternatives.

Central Savanna is landlocked and does not connect to the Atlantic. It includes the Sahel and savanna downstream to the east of the great bend in the Niger River, south of Gao to the confluence with the Benue River, and eastward to the Lake Chad basin. We avoid using the historical term “Central Sudan” due to modern-day countries. Areas around Lake Chad include the Yadrem and Yobe rivers, Mandara Mountains, Gongola basin and northern Adamawa plateau. It includes the various Hausa states, which consolidated into the Sokoto Caliphate after 1804; Jos Plateau, Kanem-Borno, Gwari, parts of Nupe and Borgu, among others. Hausa and Kanuri were among the most widely spoken languages, although Fulfulde was also widespread because of nomadic Fulbe pastoralists, known locally as Fulani or Fellata. People from this region reached the Americas via the bights and occasionally classified as Agusa (Jausa), Bornu, Fula, Gwari, Tapa, among others.Footnote 33

Western Savanna is anchored in the Fuuta Jalon highlands, which are the source of the Niger, among other rivers extending eastward to the inner Niger River Delta. It is also the source of the Senegal and Gambia Rivers, which flowed toward Gorée, St. Louis, among other key slave trading forts. This expansive territory extends northward to the cities from the ancient kingdom of Wagadu/Ghana; and eastward across the Sahel beyond the Niger River Bend to include Gao, which has been an historically important commercial and political center, especially when the Sahel’s vegetation extended further north before desertification.Footnote 34 The bulk of this territory was formerly the center of Mali and was later incorporated into Songhay, which collapsed in the 1590s, after which the Bambara states of Segu and Kaarta dominated the region.Footnote 35 The area was largely Muslim and witnessed the earliest jihads in West Africa spanning the late seventeenth century through the nineteenth centuries. In the Americas enslaved people identified as Mandingo or Mandinga, that is, Mandinka, although others were referred to as Bambara (Bamana) who were not generally considered to be Muslims but spoke the same language. Other ethnolinguistic groups include Susu, as well as pastoral Fulbe, who are known locally as Ful, Fula, or Peul.Footnote 36

Rivers is an awkward way to refer to an African sub-region since there are rivers everywhere on the continent, but due to a lack of alternative names, we use it to replace “Upper Guinea Coast.” Of the people we consulted, some thought it formed part of the western savanna, but we elected to keep it separate due to its association with the Atlantic slave trade which is arguably distinct from Senegambia networks. Some slave traders referred to this area as the “Rivers of Guinea.” While we seek to avoid using slave trading terms, we felt that “Upper Coast” referred more closely to Africa’s northwest, while “Rivers” was still neutral enough despite its sordid historical connections. In addition, Boubacar Barry defined it as “Southern Senegambia” or “Southern Rivers region,” which relate to the noticeable riverine systems that characterize this area.Footnote 37 At mangrove swamps along the coast, rivers meet tidal incursions, while rapids descend from a plateau rising a few hundred kilometers inland; and the terrain rises further again to the Futa Jallon highlands. Moreover, heavier rains occur in lower elevation areas, which provide a distinctive ecosystem where rice cultivation predominated and whose interior supplied slaves into the savanna and Atlantic world. Before the era of the Atlantic slave trade, the Mali empire likely incorporated large sections of this sub-region into its southern territorial possessions. The coastline spans from the Casamance River to about Cape Mesurado. Key rivers include the Corubal, Geba, Nuñez, Pongo, and Sierra Leone. Embarkation points for the enslaved consisted of the Bissau, Bunce Island, Cacheu, Gallinhas, Îles de Los, Nuñez, Pongo, and Sherbro. Ethnolinguistic groups included Baga, Balanta, Biafada, Bijago, Brame (Bran), Bullom, Diola, Mende, Nalu, Papel, Susu, Temne, and Vai.Footnote 38 By the late eighteenth century, this area was a receiving zone of enslaved Africans, when Freetown absorbed an estimated 100,000 Africans and their descendants, who came from Nova Scotia following the American Revolutionary War, and then directly from West and West Central Africa during the British campaign to abolish slavery after 1807.Footnote 39

Forests refers to an area that comprises a seasonal tropical forest ecosystem, which are protected rainforests in modern-day Liberia and Cote d’Ivoire. Slave traders knew this region as the “Windward Coast,” which included sub-sections they variously called the Grain, Ivory, Kru, and Quaqua coasts. Despite many types of rainforests on the continent, we elected to use this simplified, neutral terminology to distinguish it from the much larger equatorial rainforest in the central interior. This forest is distinguished as a principal source of kola nuts traded into the savanna. Our proposed coastal boundaries stretch from Cape Mesurado to the Bandama River, and beyond Cape Lahou toward Grand Bassam. Key ethnonyms included Bete, Gouro, Kissi, Kru, and others sometimes classified as Mandingo more broadly, or Ganga in Cuba.Footnote 40

For lack of a better term, we use Voltaic to describe the basin encompassing the Black, Red, and White Volta rivers, which extend into the interior as far as modern Burkina Faso. The area also includes the Comoé River valley, which flows into the Atlantic at Grand Bassam through a lagoon system near Abidjan. Due to the gold and slave trade, dozens of fortified castles dotted the coastline, such as at Elmina, Cape Coast, Anomabu, Koromantse, Christiansborg, among others. Besides gold and slaves, the area was important for kola production. In the early eighteenth century, the Asante kingdom emerged, dominated the region, and controlled the slave trade until colonization. Ethnonyms included Akan, Akwamu, Fante, among others; and in the Americas, people consisted of Cormanti, Mina, and Popo.Footnote 41

The bights found in the Gulf of Africa extend northward into two recognizable sub-regions from the Atakora mountains to the Adamawa Plateau and grasslands of Cameroon; and refers to an area to the east and west of the Niger-Benue confluence in the lower Niger valley. Except for their relative location west and east of the confluence, we realize “bight” is more seaward facing than not, but we could not find easy alternates.

Western Bight typically conflates onto the “Slave Coast,” which in contemporary European sources described the section of coast and lagoons between Little Popo and Lagos, including Ouidah, Porto Novo, among others. In a broader sense, it extends from the Volta River eastward to the western Niger River delta and was bounded by the Atakora Mountains in the west; and in the east by the Niger River below the Benue confluence. This highly populated region included the kingdoms of Allada and later Dahomey, along with Yoruba-speaking states, such as Ife, Ijebu, Oyo, among others. It also includes the southern Borgu and Nupe; and peoples who spoke Gbe, the most widespread being Ewe and Fon. Toward the Niger delta was the kingdom of Benin, among other groups in the Niger Delta, such as Isoko, Warri, among many others. Major ethnonyms across the Atlantic included Lucumi, Nago, Aku, Arará, and Mina.Footnote 42

Eastern Bight refers to the interior of the Bight of Biafra and incorporates the central and eastern Niger Delta and Cross River region northward to the Benue River. Geographically, the coastal boundary extends from Cape Formoso to Cape St. John in modern-day Equatorial Guinea. We, however, limit its extent to a point south of Douala in modern-day Cameroon because it conforms to patterns in slave ship departures. There was little slave-trading activity to the south of Doula, which include peoples associated with Bantu languages of West Central Africa. In terms of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Igbo and Ibibio supplied most of the enslaved to the coast. Other ethnonyms included Fang, Efik, Ijaw, Tiv, Igala, among others; and various people on the interior grasslands north of Mount Cameroon. The three main slave ports were Bonny, Calabar, and Elem Kalabari. In the Americas, people were mostly designated Carabali.Footnote 43

The Cabo Verde islands were uninhabited until their discovery by the Portuguese in 1456. They are divided into two groups: Barlavento or windward islands with Boa Vista, Santo Antão, Santa Luzia, São Vicente, São Nicolau, and Sal; and Sotavento or leeward islands with Brava, Fogo, Maio, and Santiago. They had ties to the mainland through Bissau and Cacheu.Footnote 44

Gulf Islands are part of a line of volcanoes emerging offshore from modern-day Cameroon. They include Anobom, Fernando Po (now Bioko), Príncipe, and São Tomé. As stopping points for slave traders, these islands had connections with both West and West Central Africa.Footnote 45 To maintain cohesion with Voyages, we include these two island clusters in West Africa.

West Central Africa

This broad region is predominately Bantu in terms of linguistic identification. The area covers Angola, Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, southern Gabon and eastward to Zambia. Nearly half of all enslaved people in the transatlantic slave trade, or approximately 5.7 million people, boarded slave ships at ports between the Gabon estuary and north of the Namib Desert.Footnote 46 In most historical data, “Congo” or “Angola” were common, but these designations suggest nothing more than an individual originated somewhere in this broader region and must be treated as such. However, there are a vast array of other ethnonyms and designations associated with the region. Amendments from our earlier map involved amalgamating most of the “Loango Coast” into the equatorial rainforest, eliminating usages of “Kwanza North” and “Kwanza South” which are modern-day provinces in Angola, and dividing the large “Central Interior” into two distinct sub-regions.

West Central North incorporates the stretch of coast from Cape Lopez at the Gabon estuary to the Kwanza River basin, including some areas to the south of the river depending on the time period. This southern border is very fluid. The sub-region is more or less anchored on the Kongo kingdom, but includes the Mayombe region too. Other kingdoms included: Bengo, Bolia, Loango, Kakongo, Loge, Ngoyo, Ndongo, Matamba, Kassanje, among other smaller ones. People from this sub-region mostly spoke Kikongo and Kimbundu, but the degree of cultural and linguistic unity is unclear. Dense rainforest and northern Congo River tributaries characterize this area, and it includes the Malebo Pool. It extends as far east as Lake Mai Ndombe, which was the border with Lunda and a major commercial zone to the lower reaches of the Kasai River. The eastern border is shaky because the Lunda empire expanded westward to incorporate the Yaka kingdom. The eastern border falls along the Kwango River and extends southward along the flat highlands of the Songo and Kuba regions. The southernmost border is at the northern edge of the central Angolan highlands. The main Atlantic ports include: Cape Lopez, Mayumba, Kilongo River, Loango, Cabinda, Congo River, Ambriz, and Luanda. In the Americas, Congo sub-groups included Angola, Hako, Kakongo, Kalandula, Kongo, Libolo, Matamba, Mboma, Muburi, Ndembu, Ndongo, Ngoyo, Njinga, Songo, Dongo, Teke, Vungu, Yaka, among many more. It should be noted that Kasanje, who reside in this sub-region, mostly entered Atlantic network via the eastern side of the central highlands and Benguela.Footnote 47

West Central South includes the region from the central Angolan highlands to the towns of Huila and Moçamedes, formerly Namibe, on the northern fringes of the Kalahari and Namib deserts.Footnote 48 A geographic distinction is the “rough highlands” closer to the coast and “flat highlands” on the broad plains to the east. Kisama, who organized into smaller political units and decentralized societies, resided on the south side of the Kwanza river. In the seventeenth century, Bembe and Mujumbo dominated the region. By the early eighteenth century, centralized and militarized states started to reorganize, such as Bihe, Kakonda, Mbailundu, and Wambu. Sources refer to Khoe and Kung groups in the south, while Ovimbundu emerged by the end of the nineteenth century. The key port was Benguela and key ethnonyms included: Benguela, Bihe (Viye), Ciyaka, Fende, Hanya, Kakonda, Kilengues, Kingolo, Kipeyo, Kitata, Nano, Ndombe, Nganguela, Mocoando, Mocorocas, Mucuancalas, Sokoval, Wambu, among others.Footnote 49

The equatorial Rainforest comprises the enormous watershed of the Congo River and its tributaries. The Ubangi and Uele Rivers frame the north and around the Kasai River in the south. In the east it touches the Atlantic from south of Douala to above Cape Lopez, in modern-day Cameroon and Gabon, respectively. Only small numbers of slaves originating from this sub-region went into Atlantic networks in the early sixteenth century, and when they did, they were usually brought from the middle Congo River by Tio middlemen through the Kongo kingdom. By the eighteenth century, the rainforest became a major source of enslaved people via networks of Bobangi merchants, who transported people from as far as the upper Congo bend. Ethnonyms included Aduma, Bobangi, Nunu, and Okande.Footnote 50

Southern Savanna extends from the rainforests southward as far as the Zambezi River. The Kwango and upper Kwanza rivers form its western border, while the east extends to around Lake Malawi. Its northern border resides along the rainforest and eastward as far as the Great Lakes. This sub-region includes lakes Bangwela, Kisale, and Mweru. The southern end lies around the copper belt, which spans the modern-day border between northern Zambia and Democratic Republic of Congo. Kingdoms include Kazembe, Luba, Lunda, and Luyana/Lozi. Captives acquired in war or tribute were sold to Imbangala and Yaka intermediaries supplying the northern ports of West Central Africa, while Luba sent captives to Atlantic ports and to the Indian Ocean. Ethnonyms included Bisa, Bemba, Imbangala, Soso, Vili, Yaka, and Zombo.Footnote 51

St. Helena, which is over 3,000 kilometers from the mainland in the southern Atlantic, had historical connections with South Atlantic trade, especially following British abolition after 1807.Footnote 52 To maintain cohesion with Voyages, we include St. Helena in West Central Africa, although there are equally deep connections to southern Africa and the Indian Ocean world.

East Africa

This broad region is interconnected with the cyclical monsoons of the Indian Ocean world, as well as Atlantic networks. Voyages datasets oversimplify this broad region as “Southeast Africa and Indian Ocean Islands.” It relates to the modern-day countries of Burundi, Djibouti, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda, as well as parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Mozambique, and Zambia. The coastal belt begins approximately at the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait in the Horn and stretches to the Zambezi River. Revisions from 2019 include dividing the horn into two, shrinking boundaries around the Great Lakes, and including Madagascar and the southwest Indian Ocean islands and archipelagos.

Due to its distinct geographic shape, the Horn sub-region contains the Somali desert and environs. It borders the Ethiopian highlands and Rift valley. Its sparse population was primarily Somali.Footnote 53

The Northeast sub-region encompasses most of modern-day Eritrea, Ethiopia, Djibouti, and most of Somalia. In a certain sense, this region is among the more difficult to define due to its connection to the Nile valley, Great Lakes, eastern savanna, Somali desert, and Indian Ocean world. Since pre-Aksumite times, people from this sub-region engaged in far-flung commercial exchanges with the Nile valley, Red Sea, Persian Gulf, and Indian Ocean. The northern border sits around the Aswan line, and extends toward the Great Lakes. South of Aswan, various kingdoms flourished, such as Dinka, Meroe-Kush, Funj, Nubia, Nuer, and Shilluk. At different points in time, commercial hubs included Adulis, Berbera, Dahlak al-Kabīr, Massawa, Tajura, and Zeila.Footnote 54 Enslaved Africans from this region were collectively labeled habasha. Footnote 55

Eastern Interior includes the plains and mountains of eastern Africa that dominate the eastern hinterland as far as the Great Lakes.Footnote 56 To the north it abuts with the Ethiopian highlands and blends into the semi-desert of the Horn. Different pastoral societies populated the sub-region’s northern reaches, while the south was a source of slaves at Zanzibar. Ethnonyms included Kamba, Nyamwezi, Maasai, and Turkana.Footnote 57

Eastern Savanna incorporates Wadai, Darfur, and Kordofan west of the Nile valley. It includes the Sudd region and sources of the Congo River’s northern tributaries. Besides the inhabitants of Wadai and Darfur, it included nomadic Arabs as well as Dinka, Nuer, Sara, and Shilluk.Footnote 58

Great Lakes form around the large lakes of Albert, Kivu, Kyoga, Edward, Rukwa, Victoria, Tanganyika, but not Bangwela, Bangweulu, Kisale, Mweru, and Malawi. This sub-region was a source of enslaved people into the northeast, eastern savanna, and Nile valley. Most arrived at the east coast opposite Zanzibar. Ethnonyms included Baganda, Banyarwanda, Banyoro, Barundi, Bashi, and Manyema.Footnote 59

East Coast, or Swahili coast, is a relatively thin strip of territory stretching from the Shabelle River and extending to the Rufiji River and Mafia Island to the south of Zanzibar. It extends no more than about 200 kilometers inland; beyond which is a low population, except in highland areas of the eastern interior. Numerous trading towns did not develop strong territorial empires, but rather ports and places, such as Mogadishu and Mombasa, which participated in the monsoons of the trans-Indian Ocean trade. It includes the Zanzibar archipelago, and especially the main islands of Pemba and Unguja (Zanzibar). Ethnonyms included Bagamoyo, Nyika, Somali, Swahili, Zaramo, and Zigula.Footnote 60

East Central lies between the Rufiji and Zambezi Rivers, including the Kilwa coast. Inland boundaries run along the Rufiji River to the Luwegu confluence, after which it extends westward along the southern shores of Lake Tanganyika and then the Luapula River southward until Zumbo. It includes Lake Nyasa (Malawi) and the Zambezi valley. For the most part captives boarded slave ships through Angoche, Kilwa Kivinje, Mozambique Island, and Quelimane, which mostly engaged in trade to Brazil in the early nineteenth century. Ethnonyms included Makonde, Makua, Manganja, Ngindo, Nyasa, Sena, and Yao. It was also the location of Portuguese land grants (prazos).Footnote 61

Madagascar was both a source and destination for enslaved captives of diverse cultures. It is grouped into East Africa due to the nature of trade across the Mozambique Channel and into the Indian Ocean world.Footnote 62 Malagasy ethnonyms consisted of Merina, also called Hova by slave traders, and Sakalava.

Southwest Indian Ocean island clusters have always been connected to the broad East Africa region, and served both as a destination and departure point for enslaved people, especially in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Comoros are located in the Mozambique Channel and consist of Grande Comore (Ngazidja), Anjouan (Ndzuwani or Nzwani), Mohéli (Mwali) and Mayotte (Maore or Mahori). The Mascarenes are centered around Mauritius, in particular, and Réunion, which different Europeans variously occupied, were connected in the East India trade, and were the geo-political-economic center of the southwest Indian Ocean islands. It is worthwhile to lump into the Mascarenes archipelagos, including the Seychelles, which contain over one hundred islands such as, Mahé, Praslin, and La Digue. We also include Agalega, Chagos, Rodrigues, and Tromelin because a slave trade went to those small, mostly isolated islands.Footnote 63

Southern Africa

The southern continental cone begins at the northern Kalahari Desert around the Cape of Good Hope until the Zambezi River. It relates to modern-day Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe, as well as parts of Angola, Mozambique, and Zambia. Except for Cape Town and around Maputo Bay, most of the coast was sparsely populated until Inhambane, which sent captives to the Mascarenes and the Americas in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.Footnote 64 The Kalahari and Namib deserts had low populations. Amendments to the map include dividing the grasslands into two sub-regions and shifting the northern section of the southeast coast into a new, southcentral region.

Southern Grasslands extends from the Cape of Good Hope, along the coast and inland east of the Kalahari Desert. It included many of the Khoisan speaking areas from the Cape to the Nguni region, and Mpondo. The Xhosa used to be called the “Southern Nguni.” Nguni-speakers, specifically the Xhosa, predominate in the southern areas, including in the present-day province of Eastern Cape in South Africa, and cities of East London and Port Elizabeth. Other ethnolinguistic groups included European descendants at Cape Town, who became known as Boers.Footnote 65

South Central is the Zimbabwe plateau and mostly consists of wide-open grasslands. The Highveld constitutes the other major geographic feature of this area and is separated from the southeast by the Drakensberg Mountains. The area around the so-called copper belt forms the northern border. The major ethnic group was identified as Shona after c.1800, and includes the sub-groups of Karanga, Korekore, Manyika, Ndau, and Zezuru. Given the historic connections between Mapungubwe, Tswana and Sotho areas, it included the Mutapa kingdom, and its earlier Zimbabwe kingdom; and Swazi. Venda inhabited both sides of the Limpopo River; and the Tonga on both sides of the Zambezi. It connects directly to the Mozambique Channel via Kiteve, Manica, and Mutapa with a coastal outlet for the interior at Sofala. It was an area with pockets of Nguni speakers, including Ndebele who moved from the Highveld northward after the 1830s, and it was a destination of Boer expansion from Cape Town, among other peoples.Footnote 66

Southeast refers to the coastal belt from Sofala Bay south to Maputo Bay, formerly known as Delagoa Bay or Lourenço Marques, and separated from the Highveld in the interior by the Drakensberg Mountains. Inhabitants included Bitonga, Chope, Ronga, and Tsonga. The principal slaving port was Inhambane, while Delagoa Bay had Austrian, Dutch, and Portuguese establishments from the eighteenth century onward. The area south of Maputo represents the historic and current heartland of Nguni-speaking people with most of them in that area speaking IsiZulu. The Zulu once were referred to as the “Northern Nguni” to distinguish them from the Xhosa, or “Southern Nguni,” but these terms have fallen away.Footnote 67

The Kalahari sub-region includes both the Kalahari and Namib deserts, which had low populations of hunter-gatherers, such as Gǁana, Haiǁom, ǃKung, Khoekhoe, Naro, and Tshu–Khwe.Footnote 68

Conclusion

The eight coastal regions Curtin initially developed in 1969 – which Voyages adopted and modified – have undoubtedly revolutionized our understanding of Africa and its incorporation into the Atlantic world. Their approach has affected methodologies on research about Africa and the African diaspora, which did not necessarily involve the transatlantic slave trade. Establishing a new regional terminology for the purpose of historical interpretation, database construction, and digital project development has required amending the regionalization of the entire continent for purposes of constructing a major historical Africa GIS project, which could unravel shifts in meanings of ethnonyms, instances of conflict, commercial networks, migratory patterns, and other factors both geographically and temporally. Due to the pioneering efforts of Curtin and Voyages, this new regionalization has the potential to influence how scholars might organize archives, digital resources, and other multimedia. Our goal is to recast African history not just in terms of its Atlantic connections, but more broadly in terms of its global connections across the Sahara, the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean. It is conceivable that this controlled vocabulary will also affect how primary open source data are clustered, re-interpreted, organized, linked, and disseminated online. Our regionalization is meant to guide researchers to reframe and contextualize geo-historical data during the building of datasets on pre-colonial Africa and the reconstruction of African history. It may also be used as a teaching tool for courses on pre-colonial African history. We have attempted to apply shortened terminologies that avoid confusion with colonial and modern boundaries, while trying to be sensitive to the peoples residing within the different parts of Africa today.