‘Men (wretched creatures that they are) worry less about doing an injury to one who makes himself loved than to one who makes himself feared’ (The Prince, Niccolo Machiavelli, 1532).

The objective of this article is to familiarise mental health professionals and lay readers with the rather colourful and disdainful history of psychiatry, particularly the political abuses of mental health legislation. The debate about legislative changes (including legislation for ‘dangerous severe personality disorder’ in the UK) often seems arcane and unnecessary until set in the context of these historical abuses of the mental health system.

Some psychiatrists have abused power in general. For example, although the war crimes for which Radovan Karadžić is currently standing trial do not arise from his psychiatric practice, it is salutary to note that he is far from being the first psychiatrist to be accused (or convicted) of crimes against humanity. However, Thomas Szasz controversially argued that there is something inherent in psychiatry, particularly the power to restrict liberty, that tends towards abuse if not regulated by the legal or political system. In the past, there have been abuses of psychiatrists’ powers to detain people, but these have been instigated at the direction of governments such as that in Nazi Germany (leading to genocide of mentally ill people) and the USSR (where political dissidents were detained with a diagnosis of ‘sluggish schizophrenia’).

Psychiatry and eugenics

The science of eugenics emerged during the late Victorian era, with the aim of reducing the rates of physical and mental illness, hereditary diseases and ‘morally deviant behaviours’. It was promoted throughout industrial countries amid fears of ‘degeneration, race suicide, and the threat of disordered sexualities’ (Reference MottierMottier 2008: p. 34). The 1933 Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring (Das Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses) required German doctors to register hereditary illnesses in their patients. In the course of the Nazi regime, over 200 ‘hereditary health courts’ were set up, which authorised over 400 000 sterilisations. Most of the people sterilised between 1934 and 1939 in Nazi Germany were labelled ‘mentally ill’ (Reference CocksCocks 1997; Reference Mottier and GerodettiMottier 2007).

Eugenics and forced sterilisation programmes tend to be associated with Nazi Germany. However, other countries had active forced sterilisation programmes and eugenics laws, among them the USA, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland (Reference WeissWeiss 2010). In 1912, Switzerland introduced laws prohibiting marriage for the ‘mentally deficient’ and ‘legally irresponsible’ (Reference Mottier and GerodettiMottier 2007). Eugenics sterilisation laws were introduced in the US State of Indiana in 1907 (Fig. 1), and in two-thirds of the remaining states by the 1930s. Havelock Ellis was a British physician and psychologist who actively promoted eugenics, although these programmes were never enacted in the UK. Eugenics was supported by many leading psychiatrists, such as Emil Kraepelin, Eugen Bleuler and especially the Swiss psychiatrist Auguste Forel, who pioneered the first sterilisations without consent in German-speaking nations in 1886 (Reference KuechenhoffKuechenhoff 2008).

Psychiatrists were particularly active in the eugenics field and were often directly involved in identifying victims for forced sterilisation. In 1934, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a lengthy report on the German eugenics law and its many expected benefits. In 1936, the authors of Eugenical Sterilization, led by Abraham Myerson, one of America’s most respected psychiatrists, praised Hitler’s eugenics legislation. Indeed, the prosecution at the Nuremberg Trials of 1945–1949 felt unable to classify forced sterilisations as war crimes, because similar laws had been implemented in the USA, where up to 25 000 such sterilisations took place (Reference CocksCocks 1997; Reference Mottier and GerodettiMottier 2007).

Psychiatry and the Holocaust

The Nazi regime considered that life was a matter of survival of the fittest. Concepts such as equality and justice were creations of ‘inferior’ groups designed to weaken the true, pure stock of the ‘master race’. Hence, it became the responsibility of the state and true Aryan people to ensure that racially desirable members of society thrived and that biologically inferior or defective people were extinguished (‘racial hygiene’). Poverty and disease were thought to arise from hereditary defects due to non-Aryans contaminating the gene pool and also to misguided ideals of welfare and equality. Nazi policy recognised that German people had to be trained to extinguish their biological inferiors, to prevent both ‘racial degeneration’ and their continued drain on resources (Reference CocksCocks 1997).

The Nazi regime considered people with incurable mental illness as having a ‘life not worth living’ or ‘life unworthy of life’. German psychiatrists were therefore required to identify people with these forms of ‘hereditary’ mental illness.

The rise of eugenics

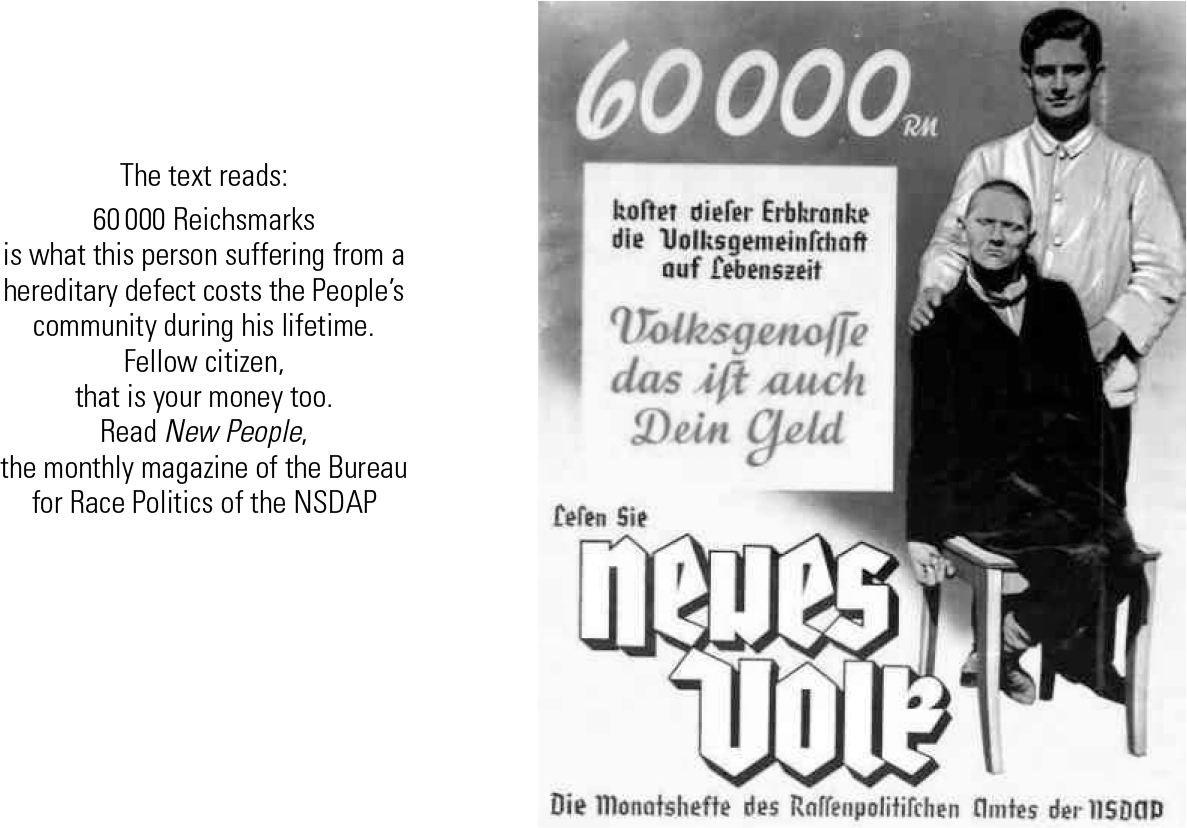

Psychiatrists in Germany and abroad had been enthusiastically promoting eugenics programmes involving sterilisation of the mentally ill decades before Hitler came to power. Many German psychiatrists collaborated eagerly with the Nazis from the very beginning, including enforcement of the 1933 Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring, which required sterilisation of people with many illnesses, including schizophrenia, manic depression (bipolar disorder) and alcoholism. Pre-war propaganda emphasised the financial demands of these patients on the state (Fig. 2).

Aktion T-4

The procedures devised in eugenics programmes, such as psychiatric assessment of competence and disability, were crucial predecessors of the euthanasia programmes for the murder of mentally ill people in Germany. The T-4 ‘euthanasia’ programme Aktion T-4, named after the Berlin address of its coordinating office (Tiergartenstrasse 4), was established in 1939 to ensure the ‘genetic purity of the German population’ by killing or sterilising German and Austrian citizens who were disabled or mentally ill (Reference CocksCocks 1997). Eminent German psychiatrists were actively involved in the T-4 euthanasia programme at all stages, including selection and execution. Again, propaganda was used to promote the programme.

FIG 1 The Indiana eugenics law: this text is reprinted from the laws of the State of Indiana for 1907 (Indianapolis State Assembly 1907: pp. 377–378).

Under the T-4 programme, hundreds of euthanasia forms, completed by two doctors at the mental institution or hospital in question, were sent to Berlin for approval by one of fifty experts, including several professors of psychiatry. The patients were then collected from the institutions in the now infamous grey buses, and brought to six psychiatric institutions in which gas chambers had been installed (Grafeneck, Brandenburg, Hartheim, Pirna-Sonnenstein, Bernburg and Hadamar). Psychiatrists supervised the transport and the execution of their patients. The presence of physicians and other health professionals in the euthanasia centres gave a false sense of security to the victims, who did not realise their fate until the very end. Faked death certificates were intended to disguise the deaths as natural in order to hide the victim’s fate from their family and the public (Reference StrousStrous 2007).

FIG 2 Nazi propaganda poster supporting the sterilisation or euthanasia of people with mental disabilities.

Between 1939 and 1941, 80 000 to 100 000 mentally ill people in institutions were killed, including 5000 children (Reference LiftonLifton 2000). Figures for murders committed under the T-4 programme outside institutions vary, from estimates of 20 000 (according to Dr Georg Renno, the deputy director of one of the euthanasia centres) to 400 000 (according to Frank Zeireis, the commandant of Mauthausen concentration camp) (Reference CocksCocks 1997). Hitler ordered the cancellation of the T-4 programme in August 1941, following protests from the Catholic and Protestant Churches. Although public opposition ended these quasi-legal killings, they continued in secret in asylums and hospitals until the end of the war. Psychiatrists and doctors often poisoned or starved mentally ill hospital patients to death (Reference BregginBreggin 1993). (Although the 1933 Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring did not require these patients to be killed, it did permit doctors to kill them.) However, equipment, including gas chambers, was moved to the concentration camps and staff from the mental hospitals, including psychiatrists, advised and staffed the camps. Medical observers from the USA and Germany at the Nuremberg Trials concluded that the Holocaust might not have taken place without the involvement of psychiatrists in the T-4 programme (Reference BregginBreggin 1993).

The psychiatrists involved

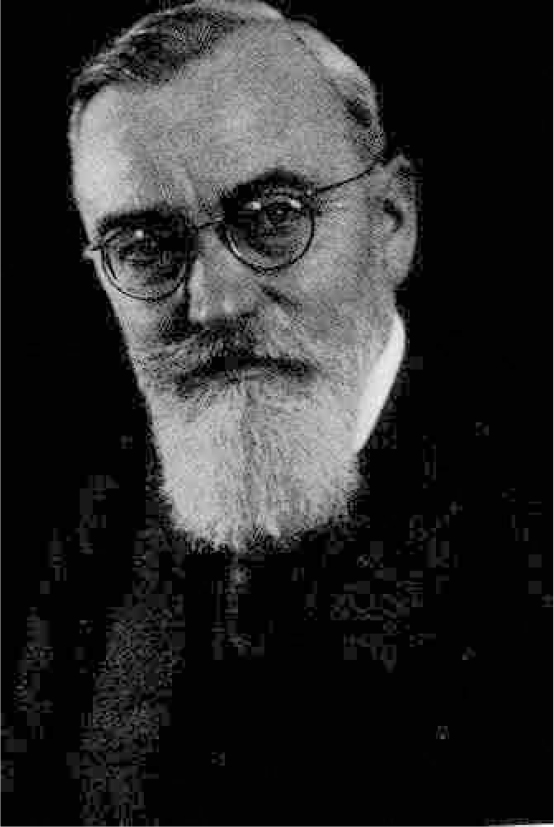

Among the German and Swiss psychiatrists actively and enthusiastically involved in the T-4 programme were four presidents of the German Psychiatric Association: Ernst Rüdin, Werner Villinger, Friedrich Mauz and Friedrich Panse. Although none of these four was subsequently punished for their involvement, at least three other professors of psychiatry were eventually captured. Karl Brandt (Fig. 3), Hitler’s personal physician and Professor of Psychiatry at Würzburg University, and Paul Nitsche, Professor of Psychiatry and Neurology at Heidelberg University, were both executed following the Nuremberg Trials for crimes against humanity (Reference FaithFaith 2010). Professor Werner Heyde of the University of Würzburg hanged himself in prison awaiting trial in 1964, having evaded capture for 20 years. Unfortunately, the German Psychiatric Association and its successor organisation refused to acknowledge the involvement of their members for 65 years (Reference FocusFocus 2010).

FIG 3 Karl Brandt. Hitler’s personal physician and Professor of Psychiatry at Würzburg University, Brandt promoted the T-4 euthanasia programme. He was sentenced to death at the Nuremberg Trials.

Although psychiatrists were not the only health professionals involved in abuses of mentally ill people in Nazi Germany, many reports indicate it was not a minority activity among them. Indeed, it is likely that a majority of practising psychiatrists in Germany at the time supported the Nazi regime and a large proportion identified their patients for the T-4 euthanasia programme. Similarly, many American psychiatrists and academics, such as Robert Foster Kennedy, supported Hitler’s euthanasia campaigns. In an editorial in the American Journal of Psychiatry (Reference KennedyKennedy 1942), Kennedy warned that American mothers might respond with ‘guilt’ over the killing of their mentally ill children. The editorial suggests a public education campaign to overcome emotional resistance to such euthanasia.

Psychotherapy in the Third Reich

Under the Nazi regime, psychiatric patients were subject to ruthless programmes of sterilisation and eventually murder. By contrast, the regime did not have the same attitude towards patients of psychotherapists. Indeed, ‘Aryans’ were naturally expected to be emotionally sensitive and could reasonably receive psychotherapy. Hence, there was a great incentive for patients, and families of patients, with psychiatric disorders to be treated by psychotherapists to avoid the dreadful consequences of receiving a psychiatric diagnosis.

In 1933, the General Medical Society for Psychotherapy was created in Berlin and it quickly became one of the major organisations in Central Europe for teaching and research in psychotherapy (Reference CocksCocks 1997). At the time, many German doctors and medical students supported National Socialism, not least because its plans to prevent foreigners, Jews and women from practising medicine promised to reduce competition for scarce jobs. Psychotherapy in Germany flourished from 1936 under the auspices of the German Institute for Psychological Research and Psychotherapy and later, the Göring Institute.

The Göring Institute: the sanction of a name

Psychotherapy was surprisingly well tolerated in Nazi Germany. Indeed, it was encouraged by the regime. Psychotherapy was able to expand as a professional discipline and it was subject to much less oppression and restriction than many other disciplines (such as psychiatry, history and even physics). For example, a Luftwaffe officer could take up to 2 years’ leave to study psychotherapy. This was largely because the principle base of German psychotherapy became the Göring Institute, led by the psychiatrist and student of Kraepelin, Matthias Henrich Göring (Fig. 4). Dr Göring was reported to be a shy, gentle man with a stammer. However, he was cousin of Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring (Hitler’s Deputy, Head of the Luftwaffe and founder of the Gestapo), and the Göring name therefore protected the Institute and psychotherapists from excessive interference by Nazi bureaucrats. By 1941, the Göring Institute had 240 members, including 100 doctors (although very few were psychiatrists). However, Jews were banned as patients from 1938.

Psychoanalytic psychotherapy

As the Third Reich expanded, psychoanalysis moved from Vienna and became centralised in Berlin. Of course, psychoanalytic psychotherapy had been established by a Jewish psychiatrist (Sigmund Freud) and had many Jewish practitioners. In an article entitled ‘The Role of the Jew in Medicine’ published in the newspaper Die Stürmer in 1933, Julius Streicher, the ‘Jewbaiter of Nuremberg’, stated: ‘Freud’s aim […] was to strike the Nordic race at its most sensitive spot, its sex life’ (Reference CocksCocks 1997: p. 59). This view was described as a Jewish ‘poisoning of the soul’.

Psychoanalysis was considered a mercenary perversion of the work of the Aryan German creators of ‘depth psychology’, Novalis, Schopenhauer and Goethe. Psychotherapists could do little to protest in this environment and by the mid-1930s Freud’s work was being burned in German universities and Jews were banned from the executives of medical societies (and later from the medical profession altogether). As a ‘Jewish science’, psychoanalytic psychotherapy was aggressively repressed by the Nazi regime. Most Jewish psychoanalysts in Germany emigrated, although 15 who did not were tortured and murdered in Nazi concentration camps. However, other forms of psychotherapy, including Jungian and Adlerian psychotherapy, became well established in Nazi Germany (despite the fact that these variants were based on Freudian psychoanalysis). Psychotherapy was actively practised and supported by the Nazi government throughout the war, but a distinct ‘German psychotherapy’ was never created (Reference CocksCocks 1997).

FIG 4 Matthias Henrich Göring, founder of the Göring Institute for psychotherapy in Berlin and cousin of Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring.

Political abuse of psychiatry in the USSR

Political abuse of psychiatry has been defined as the misuse of psychiatric diagnosis, detention and treatment for the purposes of obstructing the fundamental human rights of certain groups and individuals in a society, especially political dissidents (Reference Van Vorenvan Voren 2010).

From the 1960s, Soviet psychiatric hospitals were used by the authorities as prisons in order to isolate thousands of political prisoners from the rest of society, discredit their ideas and punish them both physically and mentally (Reference Van Vorenvan Voren 2010). Psychiatry, unlike many areas of medicine, allows doctors to deprive people of their liberty to protect them from coming to harm themselves or to protect society. Although this form of detention is carried out on the basis that these individuals are mentally ill and unable to reason, the power that detention gives psychiatry can be perverted into a form of social control. Psychiatric detention often allows society to by-pass cumbersome legal procedures such as proof of guilt in public courts. This became particularly popular in the USSR from the late 1940s as a more convenient alternative to sending dissidents to the Gulag (the system of Soviet prison camps in Siberia).

One of the first Soviet psychiatric hospitals to imprison political dissidents was in the city of Kazan (Reference Van Vorenvan Voren 2010). It came under control of the Soviet secret police in 1939. The psychiatric detention of dissidents became much more common from 1950 and the practice gradually expanded to involve hundreds of mental hospitals throughout the Soviet bloc.

‘Sluggish schizophrenia’

Throughout this period, Soviet psychiatrists diagnosed ‘sluggish schizophrenia’ in political dissidents (Reference MetzlMetzl 2010). This disorder was based on ideas developed by Andrei Snezhnevsky (1904–1987), director of the Institute of Psychiatry of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences and, until his resignation was requested, a Corresponding Fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in London. Snezhnevsky was actively involved in the detention of political dissidents.

The diagnosis of sluggish schizophrenia was based on the idea that people who opposed Communism were mentally ill since there was no other logical reason why anyone would oppose the Soviet system. Although psychiatric detention of dissidents was instigated by the Soviet secret police, many Soviet psychiatrists sympathised with the idea that dissidents may be deluded: why else would someone abandon their happiness, family and career for a belief that contradicted what most Soviet people claimed to believe? The concept of sluggish schizophrenia obviated the need to diagnose on the basis of such ‘delusions’. Antisocial behaviour, anxiety, poor social adaptation, ideas about reforming society, religious convictions and confrontation with the authorities could be used as diagnostic features of sluggish schizophrenia. Clinical features also included the capacity to behave normally for considerable periods, thereby allowing the diagnosis to be made in people who showed no overt signs of mental illness or people who did not express politically dissenting opinions at the time of examination. Patients with sluggish schizophrenia were considered to be able to function almost normally in social circumstances.

Anti-Marxist reactionary science

In October 1951, several leading Soviet neuro-scientists and psychiatrists were charged with practising ‘anti-Pavlovian, anti-Marxist, idealistic, reactionary’ science (Reference LavretskyLavretsky 1998). The defendants had to admit in public to their wrongdoing and several were dismissed from their posts. Some were also imprisoned and tortured. Many of their accusers were scientists themselves and several were subsequently promoted.

On 29 April 1969, Yuri Andropov, head of the Committee for State Security (the KGB), began the creation of a network of mental hospitals to defend the ‘Soviet Government and socialist order’ from dissenters. This involved ‘measures for preventing dangerous behaviour (acts) on the part of mentally ill persons’. Under this policy, psychiatrists could fabricate a diagnosis and detain political dissenters indefinitely without any court proceedings (Reference Possony, Veenhoven, Ewing and SamenlevingenPossony 1975: pp. 28–30). The majority of dissenters who were detained were examined at the Serbsky Central Research Institute for Forensic Psychiatry in Moscow.

Some victims of the Serbsky Institute

Between 1954 and 1987, Viktor Rafalsky was three times committed to psychiatric hospitals, for belonging to a Marxist group, for writing anti-Soviet prose and for possessing anti-Soviet literature. By the time of his final release he had spent a total of 24 years in detention. Between 1957 and 1963 Alexander Esenin-Volpin, later a Professor of Mathematics at Boston University, was also detained in mental hospitals on three occasions, for writing anti-Soviet poems. He was detained on a fourth occasion in 1969 but released and permitted to emigrate to the USA following protests by mathematicians and other Soviet scientists. Vladimir Borisov was detained in mental hospitals for a total of 9 years in the 1960s and 1970s as a human rights activist and leader of the Free Interprofessional Association of Workers.

Whistle-blowers

In January 1971, the Soviet psychiatrist Semyon Gluzman wrote a psychiatric report that refused to diagnose a political dissident as having a mental illness. For this he was eventually sentenced to serve 7 years in a labour camp. Later that spring, Gluzman was instrumental in the smuggling to the West of case reports on the use of psychiatric hospitals in the USSR to detain political dissidents. But when the practice was exposed at the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) meeting in Mexico in November 1971, members of the Soviet delegation were said to have outmanoeuvered the leaders of the WPA and no action was taken, possibly owing to a reluctance to alienate Soviet members. However, the first voices had been heard and by the late 1970s protests were more widespread among psychiatrists in the USSR.

In 1977, the Russian journalist Alexandr Podrabinek completed a book titled Punitive Medicine (Karatel’naya Meditsina). Circulated unofficially in the USSR, it contained lists of people detained in Soviet mental hospitals and the names of over 100 medical staff and doctors who took part in detaining political dissenters. The work appeared in English translation in the USA a few years later (Reference PodrabinekPodrabinek 1980). Podrabinek had also been instrumental in setting up the Working Commission to Investigate the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes. Between 1977, the year of its establishment, and 1983 the Commission reported details of 50 dissidents and non-conformists who were wrongly given a psychiatric diagnosis. This information was instrumental in convincing psychiatric associations in the West of political abuses in the Soviet psychiatric system. However, senior members of the Commission were sentenced to periods of up to 8 years’ imprisonment and/or internal exile by the Soviet authorities.

Reaction in the West

Opposition in Britain (including the creation of the Campaign Against Psychiatric Abuse) led the Royal College of Psychiatrists to establish the Special Committee on the Political Abuse of Psychiatry in 1978. These activities were denounced by Communist governments. During its 1977 World Congress, the WPA made a declaration that a psychiatrist must not take part in compulsory psychiatric treatment in the absence of mental disease (Declaration of Hawaii). The declaration did not specifically identify detention of political dissidents as its primary objective. Similarly, the terms of a WPA Review Committee, created at the Congress, were subsequently widened to include any unethical practice by psychiatrists – not just detention of political dissidents. Furthermore, the Committee was to examine only specific abuses by individual psychiatrists, not systematic abuses by governments. A British resolution put to the WPA Committee condemning the abuse of psychiatry in the USSR was passed by only the narrowest of margins (90 to 88 votes). The USSR’s All-Union Society of Neurologists and Psychiatrists resigned from the WPA, along with other Soviet bloc members, prior to a threat of expulsion in 1983.

Thankfully, the ascent of Mikhail Gorbachev in the USSR in 1985 and the political freedoms that followed ended the period of widespread political abuses of Soviet psychiatry. Still, it was not until 1989 that a delegation of US psychiatrists was allowed to interview victims of alleged political abuses of psychiatry. The All-Union Society of Neurologists and Psychiatrists was controversially readmitted to the WPA in 1989, on the understanding that it cooperated sincerely with investigations of political abuse of Soviet psychiatry. The USSR (and the Society) dissolved in 1993.

Psychoanalysis in the USSRFootnote a

Psychoanalysis shares several common themes with Marxist theory. Marxists suggest that there are no economic accidents or coincidences and that all social and political events are deliberately determined to oppress and exploit the worker. This mirrors Freud’s views of the ‘illusion of psychical free will’ – the illusion that our random thoughts and impulses arise from free will rather than being the expression of clearly defined subconscious rules. ‘Class consciousness’ and ‘revolutionary will’ are popular Marxist themes which have common ground with Freudian psychoanalytic theory. Similarly, the idea that everything should be conscious, planned and intellectually controlled is similar to Marxist ideas that behaviour and belief are socially determined (primarily so that the bourgeoisie could control and exploit the worker). Nothing should be spontaneous, random or unconscious. Marxists in Russia recognised that psychoanalysis was a tool that could be used to address this. In 1912 Freud wrote to Jung: ‘In Russia [Odessa] there seems to be a local epidemic of psychoanalysis’.

The founders of psychoanalysis had been intimately concerned with discussions of Bolshevism and Marxist politics. Freud’s parents spent several years in Russia and Freud had a number of Russian friends and acquaintances, many of whom were Jewish exiles. In 1909, the first Russian translations of Freud’s books appeared. Alfred Adler’s wife, Raisa Epstein-Adler, was a Russian Jew with radical socialist views who published frequent articles in the Russian journal Psychotherapy in the 1920s. The Russian Ministry of Education officially established the Russian Psychoanalytical Society in 1922 under the leadership of Otto Schmidt, who ensured that Freud’s books were published by the State Publishing House. His wife, Vera Schmidt, became head of the Detski Dom, which was also known as the Solidarity International Experimental Home. Attached to Moscow’s recently founded Psychoanalytic Institute, the purpose of this residential school/home was to ‘help model the future “new man”, the builder of communism’ (Reference de Mijollade Mijolla 2005). Stalin’s youngest son Vasilii was a pupil. The Psychoanalytic Institute was founded and financed directly by the Ministry of Education.

The rise and fall of psychoanalysis

Psychoanalysis had a major influence on medical practice in Russia following the revolution due to the influence of Leon Trotsky. Trotsky had personal experience of psychoanalysis while in Vienna in 1908 and he was friends with Adler. In 1931, Trotsky sent his own daughter to a Berlin psychoanalyst. Unfortunately, psychoanalysis became increasingly unpopular as Trotsky’s influence declined in the newly formed USSR from 1924 to 1927 and the Russian Psychoanalytical Society collapsed.

One of the most famous figures in early Russian psychoanalysis was Sabina Spielrein (Fig. 5). She was treated for psychosis in Austria and became the lover of Carl Jung before becoming an analyst herself and treating Jean Piaget. She devised the concept of the death instinct. She returned to Russia in 1923 and became a staff member of the Psychoanalytic Institute in Moscow. Her work, like that of all psychoanalysts in the USSR, was gradually suppressed and she and her daughters were murdered in a massacre of Russian Jews following the Nazi invasion in 1941.

As psychoanalysis declined in Russia with Trotsky’s fall, it was replaced by ‘paedology’, a school of psychological theory based on the ‘Construction of the New Mass Man’, although this was led by ex-psychoanalysts (Reference EtkindEtkind 2012). There was little psychoanalytic research published in the USSR in the 1930s as the Stalinist regime became increasingly rigid. Pavlovian ideas became dominant and psychoanalysis was regarded as an elitist Western practice. Paedology was prohibited in 1936 and replaced by ‘collectivist pedagogy’ which reinforced obedience to the leader and aggression to outsiders. Marxist psychology became heavily influenced by theories developed by Karl Kautsky. In 1906, Kautsky had suggested that human beings have a ‘social instinct’, with a natural tendency for altruism and self-sacrifice, submission to the will of society, fidelity to the community, obedience and truthfulness to protect the collective. Clearly, these ideas had great value in a totalitarian regime such as Stalin’s Russia and they were actively promoted. Furthermore, according to Marxist theories, illness without physical cause could only have a social cause. Hence, psychiatry in Russia gradually adopted social and moral norms as criteria of sanity, and political dissent became a symptom of psychiatric illness. Despite its great initial influence, psychoanalysis disappeared from Russia from the 1930s until collapse of the totalitarian regime in the 1980s.

Thomas Szasz

The controversial psychiatrist Thomas Szasz was born in 1920 in the Hungarian city of Budapest, son of a Jewish businessman (Reference StadlenStadlen 2012). By 1938, Hungary had sided with Nazi Germany, and the Szasz family moved to the USA. Szasz died on 8 September 2012.

FIG 5 Sabina Spielrein. A founding figure in early Russia psychoanalysis, Spielrein trained in Vienna before moving back to Russia in 1923.

A prominent and outspoken adversary of coercion (compulsory detention), Szasz denied that mental illness exists. In his books The Myth of Mental Illness (1961) and The Manufacture of Madness (1970) he criticised the ‘Free World’ as well as the Communist states for their use of psychiatric diagnosis to deprive people of their liberty. Szasz argued that there are no objective methods for detecting the presence or absence of mental disease and that so-called ‘mental illness’ is simply voted into existence by members of organisations such as the American Psychiatric Association. Szasz regarded psychiatric diagnosis as a way of controlling people whose behaviour does not conform to existing social norms. He dismissed psychiatric diagnoses as moral judgements rather than scientific categories. He believed that mental health legislation is used by the state and psychiatrists as a form of social control supported by the fraudulent claim that psychiatry is based on science. In Ceremonial Chemistry (1974), he posited that mental health legislation is used to target social scapegoats (such as drug addicts and ‘insane’ people) in the same way that witches, Jews, Gypsies and homosexuals have been persecuted. Contrary to popular belief, Szasz was not opposed to the practice of psychiatry if it is non-coercive.

Maverick, crank or pioneer?

Although Szasz was often dismissed as a crank by other psychiatrists, a variety of sources have supported his beliefs, especially following publicity of the misuse of psychiatric detention against political dissidents in the former USSR. Furthermore, seminal research on literary sources by Reference Fulford, Smirnoff and SnowFulford et al (1993) has suggested that the concept of disease employed in the USSR was similar to that still used in the UK and USA. Indeed, the case that psychiatric diagnosis is strongly supported by objective scientific research was promoted in each jurisdiction (in the Communist East and free Western democracies) despite the rather arbitrary nature of psychiatric classification. Szasz himself stated that the activities of the Western psychiatrists condemning their colleagues in the USSR for their abuse of mental health legislation was ‘an exercise in hypocrisy’ (Reference SzaszSzasz 1970).

Discussion

Does the past offer any solutions to prevent abuses of mental health legislation and diagnosis of mental illness for political purposes? In reality, few professionals in a dictatorship would dispute instructions to detain an individual from a senior state official. Soviet psychiatrists were coerced with the threat of imprisonment themselves if they failed to follow the repressive orders of the state. However, a lamentable lack of coercion appears to have been a feature in Nazi Germany, where many psychiatrists enthusiastically complied with their role in the eugenics programme.

In the analysis of abuses of mentally well political dissidents by totalitarian regimes there is a certain degree of naivety. Although life in a Soviet psychiatric hospital would be most unpleasant for all inmates by current standards, before the 1950s many Soviet political dissidents would have been shot or died of starvation in Siberian work camps.

The WPA could be criticised for its lethargy in failing to take punitive action against the All-Union Society of Neurologists and Psychiatrists and its individual members. However, it is prudent to observe that the WPA could not have had any significant influence on these totalitarian regimes by expelling their associations or trying individual psychiatrists for political abuses.

Thomas Szasz argued that a diagnosis should not be simply voted into existence, especially as it may then be used to deprive people of their liberty. In light of this, political and legal restraints need to be placed on psychiatrists’ powers to detain people on the grounds of mental illness, not least of which is multidisciplinary consensus that a person has a mental illness and should be detained and the right to demand judicial review in open court. Although legal challenge is unlikely to prevent state-sponsored abuses of mental health legislation, secrecy and the lack of transparency in these proceedings could draw international attention to potential abuses.

Activities which are now discredited, such as the detention of political dissidents and forced sterilisation, had vocal adherents who could produce apparently plausible scientific reports to show their effectiveness. There was highly visible support in the media from respected medical and political leaders. This raises concerns about the ability to detain people under the Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder Programme in the UK, by which patients are not required to have been convicted of any offence, nor do the proceedings require any public hearings in court (although in practice most of the 200 or so patients subject to these proceedings are likely to have been diverted from the courts) (Reference Buchanan and GroundsBuchanan 2011). Regrettably, detention of people with ‘dangerous severe personality disorders’ was politically inspired (Reference FeeneyFeeney 2003). Although it is unlikely that there is currently abuse of the system for detaining such people, there remains a worrying potential for this within the system.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 The number of mentally ill adults in German institutions killed under the T-4 eugenics programme between 1939 and 1941 is estimated at:

-

a 10 000–20 000

-

b 20 000–50 000

-

c 50 000–80 000

-

d 80 000–100 000

-

e 100 000–150 000.

-

-

2 In the first half of the 20th century, active forced sterilisation programmes for mentally ill people were in place in:

-

a Germany and Sweden

-

b the USA

-

c Norway and Denmark

-

d Switzerland

-

e all of the above.

-

-

3 How many German Jewish psychoanalysts are thought to have been murdered in the concentration camps?

-

a 5

-

b 8

-

c 10

-

d 15

-

e 30.

-

-

4 The Russian psychiatrist Andrei Snezhnevsky:

-

a was a Corresponding Fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in London

-

b eventually defected to America

-

c spent several years in prison for refusing to detain a political dissident

-

d was married to a Jewish psychotherapist

-

e was tried in The Hague for human rights abuses.

-

-

5 Sabina Spielrein:

-

a was an active member of the Nazi Party before moving back to Russia

-

b was the wife of Carl Jung

-

c a Jewish psychoanalyst and a founder of Russian psychoanalysis, was murdered following the Nazi invasion of Russia

-

d further refined the concept of sluggish schizophrenia

-

e received a posthumous Nobel Prize.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | d | 2 | e | 3 | d | 4 | a | 5 | c |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.