Introduction

Between the end of the 3rd c. and the middle of the 7th c. CE, the practice of producing and setting up free-standing statues declined steadily across the Roman Empire, until its near-complete disappearance.Footnote 1 For centuries, communities around the Mediterranean had crowded public and private spaces with marble and bronze representations of emperors, aristocrats, and deities, celebrating social and political hierarchies as well as cultural values. Statues played a crucial role in social life, and the statue habit – the recurring and socially diffuse practice of setting them up – was one of the defining features of ancient cities.Footnote 2 Whereas other types of sculpture like reliefs and miniatures continued to be commissioned and displayed in churches and palaces throughout the Middle Ages, life-sized (or colossal) statue monuments placed on top of inscribed bases became a survival of the past. The decline of this practice was a key aspect in the social, cultural, and material transformations that characterized the history of cities in Late Antiquity.Footnote 3 This was a complex process with broad repercussions that has justifiably attracted much attention in recent years.Footnote 4 And yet, there are fundamental questions that remain open: to what extent was the Late Antique statue habit different from its previous phases? How did it change during its final phase? And, crucially, what was the significance of dedications in such a changed context?

This article analyzes the evolution of the statue habit in Late Antique Rome, charting its quantitative decline as well as the striking changes that redefined the city's population of statues. Rome was home to the richest sculptural collection of the ancient world, a product of centuries of imperial expansion and domination.Footnote 5 For most of Late Antiquity, statues continued to be dedicated on a scale unparalleled in the Empire.Footnote 6 As a result, the once imperial capital provides us with the best-documented case study for the entire Mediterranean. The publication in 2012 of the online database Last Statues of Antiquity (henceforth LSA) has put modern scholars in an ideal position to examine this material, collecting the sculptural, epigraphic, and textual evidence for newly produced and restored statues in Late Antiquity.Footnote 7 Perhaps more importantly, focusing on a specific city allows us to consider the statue habit in its proper historical and physical context.Footnote 8

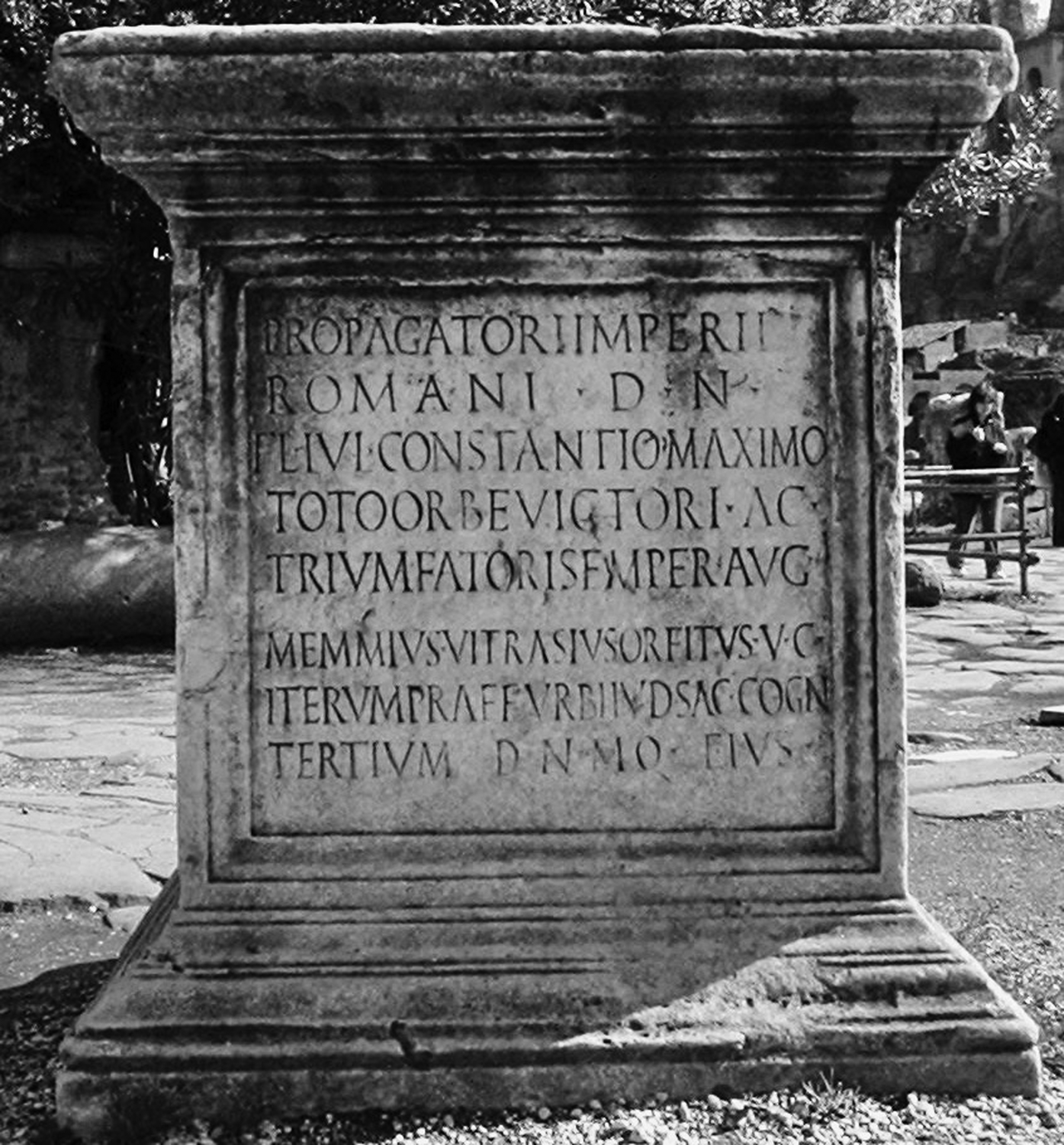

Late Roman statues have been analyzed from different perspectives, from the art historical emphasis on style and iconography to the more explicitly archaeological/historical focus on issues such as placement, function, and preservation.Footnote 9 Rather than the sculpture itself, this article is concerned with the social practice that generated it, focusing on the dedicatory inscriptions that celebrated the erection of each monument. Whereas we remain poorly informed about the provenance and identity of much of the surviving sculpture, the city's exceptionally rich epigraphic record throws a unique light on the dedication of statues.Footnote 10 A good example is the dedication of a statue to the emperor Constantius II by the urban prefect Orfitus (Fig. 1):

To the extender of the Roman empire, our lord Flavius Iulius Constantius the greatest, victorious over the whole world and triumphant, forever Augustus. Memmius Vitrasius Orfitus, of clarissimus rank, prefect of the City for the second time, judge in the imperial court of appeals for the third time, devoted to his divine spirit and majesty [set this up].Footnote 11

Fig. 1. Base of statue celebrating Constantius II, Roman Forum, 357 CE. (Roman Forum, Sopr. For.-Pal. Inv. 12454; photo by C. Machado.)

The statue celebrated Constantius for his victory over Magnentius on the occasion of his visit to Rome in 357 CE. It was set up in the Roman Forum, surrounded by other statues dedicated to mark both his victory and his visit, in an area clearly associated with imperial visits.Footnote 12

Latin inscribed dedications – most often carved into statue bases – usually record the identities of the honorand(s) in the dative case and of the awarder(s) in the nominative. The different categories of agents involved in this practice (such as emperors, officials, and senators) can be identified even in the case of fragmentary texts, information that can be quantified and charted over time.Footnote 13 The spatial context of a monument – whether a prestigious public complex or a domestic structure – might also help identify the agents involved.Footnote 14 In addition, inscriptions recorded restorations and the movement of monuments to new (and more prestigious) locations. Whether honorific or not, these texts frequently stated the reason and circumstances for each dedication, sometimes explicitly recording the date of the dedication.Footnote 15 While it is true that we are better informed about the city's monumental center, the number of excavations and chance finds from other neighborhoods helps us identify general trends for the evolution of this practice.

Scholars have traditionally considered these dedications in terms of their sociopolitical value or as a sign of Late Antique care for the Classical past (evidenced by inscriptions attesting to the restoration and/or movement of statues),Footnote 16 missing important aspects of Late Roman material culture and its sociopolitical implications. As R. R. R. Smith has shown for Aphrodisias, statues must be considered holistically – in their honorific, religious, and artistic dimensions – as part of a specific statue habit and statue culture.Footnote 17 As I will argue below, Rome's Late Antique statue culture was fundamentally different from that of earlier phases, in spite of continuities, and this transformation becomes evident from the middle of the 4th c. onwards. This was due to the city's unique imperial standing, and especially to the role played by the senatorial elite in the use of statues as a sign of distinction. The decline in the number of statue dedications and the redefinition of the Roman elite were intertwined processes that led to a profound change in the meaning and cultural significance of statues. Although atypical, the case of Rome is important not only because it sheds light on crucial aspects of the Late Antique statue habit in different parts of the Empire, but also because of the central role played by the city, its statues, and its elite in the history of urban communities all around the Mediterranean.

The statue habit in Late Antique Rome

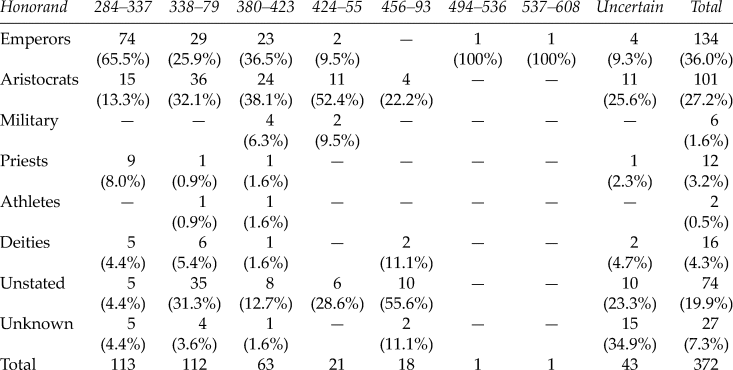

The Late Antique statue habit presented a complex blend of continuity and innovation, and it is worth considering it as a whole if we want to understand it properly. Building on the information available in the LSA database, I have been able to identify 372 inscribed dedications.Footnote 18 One will never be able to claim completeness, and this is certainly a fraction of the actual number of statues dedicated (many without inscriptions). Over 365 years, from 284 to 608 CE, this gives us an average of just 1.02 dedications per year. Although it remains impossible to know with certainty how representative Late Antique numbers are, it is clear that many more statues were dedicated in the Early Empire than in the period that interests us (Smith estimates approximately four times more per year).Footnote 19 We are in a better position to assess how exceptional Rome was in Late Antiquity. The number of statues dedicated by Romans stands out very clearly when compared to other cities, with the possible exception of Constantinople.Footnote 20 Even places like Ephesus and Aphrodisias, which retained a vibrant sculptural tradition and continued to produce statues until approximately 500 CE, never did it on the same scale as the old imperial capital.Footnote 21

Roman dedications can be grouped into four main categories: those made to deities (16 inscriptions, or 4.3% of the total); those dedicated to members of the imperial family, including “usurpers” (134, or 36.0%); honorific statues of non-imperial figures, such as officials, athletes, and priests (121, or 32.5%); and statues whose subject was left unstated, usually treated as dedications made for their aesthetic value (74, or 19.9%).Footnote 22 Classifications like these are always problematic, for in many cases a dedication could be grouped in more than one category, but they suggest that Late Antique dedications followed the same patterns as those of earlier periods.Footnote 23 In a general sense, it is the context in which these dedications took place that made the Late Antique statue habit distinctive. Statues and their dedications were under much closer official control during our period, for example, as attested by the role played by urban prefects in dedications.Footnote 24 The rise of Christianity must also have made traditional types of dedications more problematic: the new religion had an ambiguous attitude toward sculpted likenesses (not only religious ones), and Ine Jacobs has recently shown how even honorific statues acquired new meanings and associations in the case of the East.Footnote 25 In order to appreciate this complex mixture of innovation and continuity, we need to look at statues as part of a broader language of social distinction, before examining the political dynamics that informed the use of this system.

The Late Antique language of honors

Honor played a defining role in ancient city life, and a statue was a clear indication of the esteem, authority, and standing of an individual before his (or, less often, her) peers and inferiors. Size, material, iconography, location, and the inscribed dedication conveyed a variety of messages, expressing different gradations of social distinction and political power.Footnote 26 Due to its unique political position, Rome's language of honors was subject to stricter regulations than that of other parts of the Empire. From the time of Augustus, sculptural monuments were more or less explicitly regulated according to the conceptions and expectations of the emperor and his associates, who exercised a nearly complete monopoly over honorific dedications in public spaces. In fact, it seems that over time a growing variety of monuments became more closely connected to the ruling family, limiting what types of statues could be offered to other members of the elite.Footnote 27

Only emperors were celebrated with monuments on triumphal arches, city gates, and honorific columns, for example. There is nothing in Rome similar to the statue monument in Ephesus dedicated to Stephanus, the proconsul of Asia, above the window of the splendid Nymphaeum adapted from the façade of the earlier Library of Celsus.Footnote 28 Whereas imperial officials and notables were honored with equestrian statues in other parts of the Empire, this honor was restricted to the imperial house in Rome.Footnote 29 Even a simple free-standing monument, however, could express different degrees of social and political distinction. Dress and accessories played an important – and highly regulated – role as markers of status.Footnote 30 Diadems were introduced as a marker of royalty during Constantine's reign, as part of a wider process of differentiation between emperors (with their statues) and their subjects.Footnote 31 The only surviving Late Antique statues in Rome wearing cuirasses were imperial, a choice that was based on the political realities of the time as much as on a political choice: Late Antique senators wore togas.Footnote 32 It is possible that other honorands were also celebrated in military gear, as we know of examples from other parts of the Empire.Footnote 33 This is more likely to have been the case for military leaders such as Stilicho, Merobaudes, and Aetius, who were honored in Rome – but none of their statues survive.Footnote 34 Portraits of empresses show them in traditional dress, wearing a himation and a chiton, for example. In this case, other elements, such as diadems (introduced later than for emperors), inscriptions, and setting, were required to mark their special standing.Footnote 35

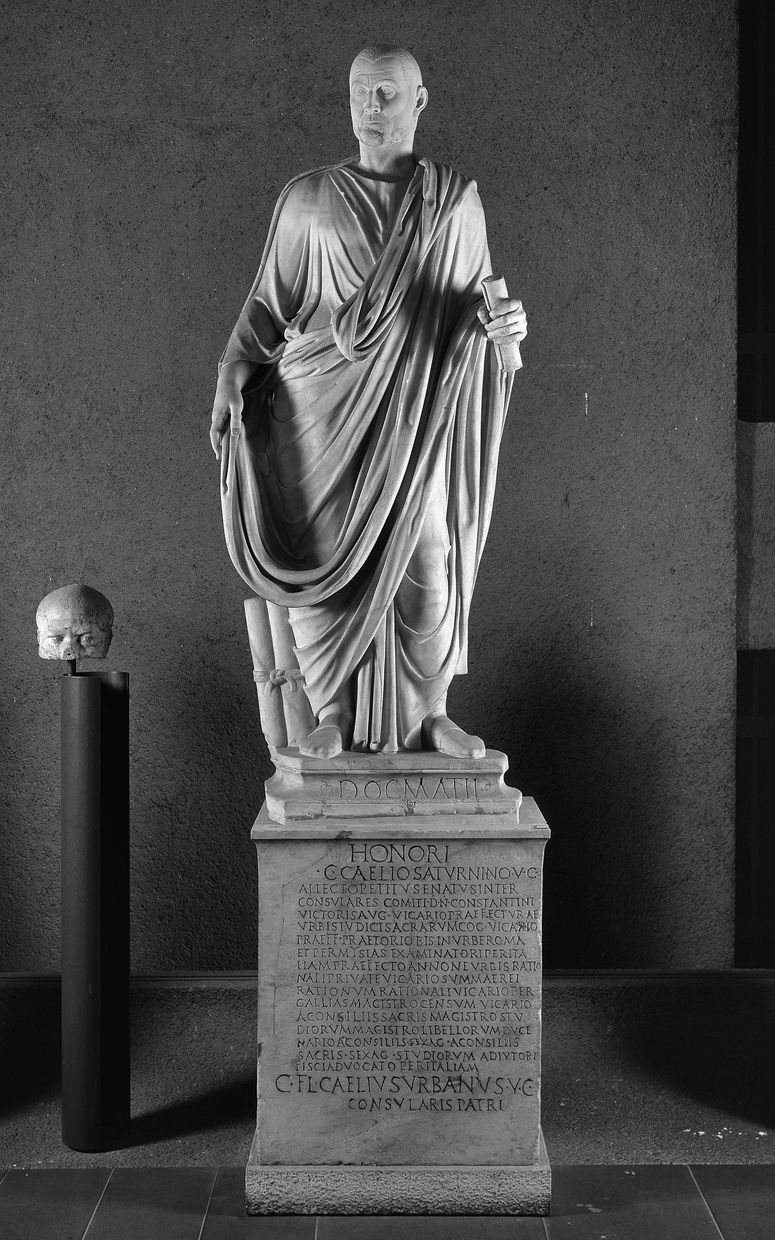

Finer gradations could also be expressed, even for togate statues. At the beginning of the 4th c., C. Caelius Saturninus was honored by his son with a statue in the family home (Fig. 2).Footnote 36 Saturninus was celebrated for his successful career, as we know from the dedicatory inscription, which took him from the rank of equestrian to that of vir clarissimus.Footnote 37 The statue's head was a reused piece, recut and inserted into the body – also reused.Footnote 38 Saturninus was thus shown wearing a traditional toga with tunic and the closed shoes associated with the equestrian order.Footnote 39 The monument thus commemorated a recently promoted senator as an eques, reflecting (whether intentionally or not) his social origins and achievements.

Fig. 2. Statue monument of C. Caelius Saturninus. (Musei Vaticani, Museo Gregoriano Profano, inv. nos. 10493, 10494. Photo © Vatican Museums, all rights reserved.)

Certain types of material remained closely connected with emperors, such as Egyptian porphyry: although only five examples survive from Rome, the pattern is clear throughout the Empire.Footnote 40 A more complex case is the use of gold, or more specifically gilded bronze, which, although not restricted to emperors, was strictly controlled by the court. While I have identified dedicatory inscriptions that record a gilded likeness of a non-imperial honorand, all of them are of very high-profile aristocrats; more importantly, all dedications are related to an imperial initiative or required imperial permission.Footnote 41 Gilded bronzes were also controlled in terms of where they were displayed: almost all documented cases come from very prestigious places such as the Forum of Trajan, the Forum of Caesar, and the Roman Forum.Footnote 42

Bronze seems to have been open to a wider range of users and occasions, as suggested by the large number of surviving bases that have fittings for bronze statues on top. Although many of these were re-employed, possibly with plinths supporting marble monuments, they nevertheless show that the use of bronze was a very real possibility.Footnote 43 The choice of material was important enough to deserve mention in dedicatory inscriptions, probably reflecting the wording of the original decree awarding the distinction. For example, the monument dedicated to Attius Insteius Tertullus by the guild of the wholesale dealers (corpus magnariorum) in the early 4th c. CE is described as a “distinguished statue of bronze.”Footnote 44 Bronze was a form of honor used by different categories of awarders, of varying rank, among them emperors, members of guilds, lower-ranking officers, and even private donors (including a husband to his wife).Footnote 45

Location was another traditional element in this honorific system.Footnote 46 The Forum of Trajan, for example, was a prized setting for senatorial statues, whereas an area like the Roman Forum was usually reserved for the celebration of emperors and only very few associates.Footnote 47 The evidence available for Late Antique Rome suggests that public spaces were carefully controlled by the political authorities. Dedications by the Senate or emperors usually took place in the most prestigious settings, such as the Roman Forum, the Forum of Trajan, and even – in one case – the Capitoline hill.Footnote 48 Prefects dedicated statues in streets, fora, and monumental complexes such as baths and theaters, celebrating either emperors or “unstated” subjects.Footnote 49 It seems clear, furthermore, that public spaces became subject to more intense control with the passing of time. This is indicated by the case of the Roman Forum, an area where a wide variety of officials (urban and imperial) dedicated statues to emperors in the early 4th c., but one that came under the control of urban prefects from approximately 350 CE onwards.Footnote 50

In contrast, domestic spaces were open to a wide range of users. The atria and porticoes of senatorial houses were traditional settings for the display of honorific monuments, from wax portraits of ancestors to patronage tablets and statues.Footnote 51 Almost half of all statue bases dedicated to aristocrats can be reasonably associated with domestic contexts: 48 out of 101 bases (47.5%). Besides those found during the excavation of a domestic structure, this number includes inscribed bases accompanied by other inscriptions related to the same individual, as well as monuments with a strong private character.Footnote 52

Although not as prestigious as the imperial fora, domestic settings were just as important for the functioning of the statue habit, as the monuments on display were physically associated with their intended audience: family, friends, and clients. Senators could thus celebrate their prestigious (and sometimes distant) ancestors, as Crepereius Amantius did for Munatius Plancus Paulinus, a 1st-c. CE senator.Footnote 53 Houses could also be used for the display of political allegiances. Although none of the surviving imperial statue bases were set up in houses (if we exclude palaces), it is likely that at least some of the many unprovenanced imperial busts were originally part of the decor of these structures. This is suggested by a passage in the biography of Marcus Aurelius in the Historia Augusta, in which the biographer remarks that up until his day people kept statues of the emperor next to their penates.Footnote 54

The politics of dedications

The political significance of statue monuments is well illustrated by the inscription recording the award of such an honor to Lucius Aurelius Avianius Symmachus, in 377 CE:

[Statue of] Phosphorius. To Lucius Aurelius Avianius Symmachus, of clarissimus rank, urban prefect, consul, legate of the praetorian prefect in Rome and in the neighbouring provinces, prefect of the annona of the city of Rome, higher pontiff, member of the college of the quindecemviri sacris faciundis, responsible on many occasions for embassies to deified emperors following the wishes of the senatorial order, whose opinion in the Senate was usually the first to be asked, who enriched with authority, prudence, and eloquence the seat of this great order. The gilded statue that the great Senate obtained from our Lords Augusti through frequent petitions, and that our triumphant emperors commanded to be set up in the accompanying oration with a list of his successive merits; and to this honor their [i.e., imperial] judgment also added that a further statue of equal splendour be placed in Constantinople. Dedicated on the III of the Kalends of May, during the fourth consulship of our lord Gratian and Merobaudes.Footnote 55

The inscription follows Symmachus's successful career, which culminated with the urban prefecture in 364–65 CE, highlighting his political services and personal virtues; it then mentions the honor being awarded, as well as the prestigious agents involved in the process: the Senate and the court. Furthermore, the monument was accompanied by an inscribed oration transcribing the imperial decision and a list of the honorand's merits – an element that, in itself, added to Symmachus's honor.Footnote 56 There was much here that was traditional, following models that had their origins in the reign of Augustus and developed over the course of centuries.Footnote 57 However, the political context of the second half of the 4th c. CE plays a major role in the dedication, not only in the fact that Symmachus was praised for his role in senatorial embassies to emperors who never visited Rome, but also by the reference to the unusual honor of having statues dedicated both in Rome and in the new imperial center, Constantinople.

Inscribed dedications frequently stressed the unique character and standing of the individual being honored. This is seen in the case of the elder Symmachus, praised for his authority, prudence, and eloquence, but also in the dedication made to his son, Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, celebrated as a most skillful orator (orator disertissimus). His contemporary, Sextus Petronius Probus, was the “summit of nobility” (nobilitatis culmen).Footnote 58 As Olli Salomies observed, during this period the language of honorific dedications became much more personal, adjectival, and hyperbolic.Footnote 59 Nevertheless, as Géza Alföldy noted, by emphasizing a small group of qualities – culture, learning, justice, ancestry – and making use of the same adjectives, these inscriptions also highlighted the fact that these men (and, less frequently, women) were all members of the same social class.Footnote 60 A similar play between uniqueness and identity is visible in imperial dedications, where successive rulers are praised as most powerful, most pious, or (paradoxically) most invincible.Footnote 61

Statues made an acknowledgment of honor – be it by an imperial decision, a vote in the Senate, or an acclamation in the circus – permanent, something for all to see.Footnote 62 As Ammianus Marcellinus observed, members of the Roman elite competed for this type of distinction: “Some of these men eagerly strive for statues, thinking that by them they can be made immortal, as if they would gain a greater reward from senseless brazen images than from the consciousness of honorable and virtuous conduct.”Footnote 63 The historian's criticism was directed not against the association of statues with immortality, but against senatorial lack of consideration for higher virtues – on which public honors should be based.

It is Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, in a surprisingly ferocious letter, who provides us with the best illustration of the complexities involved in the dedication of a statue. In this case, he complains to a friend about a decision made by the citizens of a North African town (Ep. 9.115). The decision, made public in a decree, was either to not dedicate statues to him, or to remove those that had been previously dedicated.Footnote 64 Having been proconsul of Africa in 373–74 CE, Symmachus considered these the “reproachful acts of the envious” (aemulorum facta inproba) and the “dishonorable decisions of the ungrateful” (ingratorum foeda decreta). What we see at work here is both the expectation of a Roman noble and the political mechanisms that were put in motion for the dedication of a statue: political circumstances, pressures, and commitments were important factors at play.

Aristocratic interest in statues was not new; and yet, the frequency with which this is stated in Late Antique sources suggests that Symmachus and his peers were now keener than ever for such honors. This was probably due to the changed nature of the Roman elite, following the creation of an unprecedented number of new senators in the Constantinian expansion of the senatorial order: permanent and conspicuous signs of social distinction became more valuable at a time of social change.Footnote 65 As will be shown in the next section, the senatorial eagerness for statues became more visible in the epigraphic and archaeological records around the middle of the 4th c. CE, when a new hierarchy of official titles and honors capable of expressing distinction (while reinforcing cohesion) in the face of growing social diversity took shape.Footnote 66 It was the great senatorial appetite for statues that led the emperors Arcadius and Honorius to address a law in 398 to the praetorian prefect of Italy, Flavius Mallius Theodorus, trying to control this practice:

If any governor has accepted bronze, silver, or marble statues dedicated during his term of office without imperial permission, he shall pay back to our treasury four times the emoluments he received while in the office polluted with such extortion and presumptuousness, suffering at the same time the punishment of losing his standing. For we do not want those who, eager for flattery or through fear of being considered idle, have attempted to do what is prohibited, to be immune from the risk of shame.Footnote 67

In demanding statues from those who were subject to their authority, Late Roman officials were subverting the very principle that established that such honors should be an acknowledgment and reward for their virtues and deeds. In this context, the dedication of statues had become an act of submission rather than gratitude. The court – always mindful of the distribution of honors – tried to curb this development.

Not only honorands benefited from the honor of having a statue, however. Awarders, too, could derive great prestige from setting up these monuments. Writing in the Early Imperial period, Pliny the Younger explained how this was possible in a letter to his friend Cornelius Titianus (Ep. 1.17.4). He wrote that Titinius Capito had obtained imperial permission to dedicate a statue in the Forum to Lucius Silanus, who had been executed during the reign of Nero. Such a good deed would have been enough to win Capito the highest praises but, as Pliny observed, he also won immortality, for setting up a statue in the Forum was as honorific as having a statue there.

So it is that, as a 5th-c. CE fragmentary inscription found in the Forum of Trajan records, “the lofty council and Roman people asked, with decrees contending among themselves, for another statue for him which was brought about with such great speed by the most provident and clement princes that the petition was believed to have been anticipated by the imperial distinction itself.”Footnote 68 Senate, people, and emperor arrived together in the race to celebrate this unnamed aristocrat. In the case of Cheionius Contucius, however, the city of Forum Novum openly boasted of having beaten their neighbors in the province of Flaminia et Picenum in dedicating a statue to their former governor.Footnote 69 This logic is particularly clear in the case of urban prefects, who were directly responsible for dedications to emperors and of restored works of art. In this instance, their institutional power (as imperial representatives and as managers of Rome's urban fabric) put them in a favorable position to gain distinction by setting up monuments in different spaces of the city.

Statues were thus able to express honor and power in the urban space, advertising to Roman citizens, imperial officials, and visitors the social realities and cultural values of their awarders. In spite of important continuities with the Early Empire, this system experienced important changes in Late Antiquity, changes that included a greater control by authorities like the court and the urban prefecture, and new iconographic elements. The most important evolution was not a matter of form, however, but a revolution in the very social mechanisms that animated the dedication of statues, a development directly related to the senatorial appetite for these same monuments. It is to this process that we must now turn.

The new demography of statues

The Roman statue habit experienced crucial changes in response to the social, cultural, and political developments that marked Late Antiquity. The most visible evolution was the significant decline in the overall number of statues dedicated every year – until these monuments practically ceased to be set up in the 5th c. CE. Although it is impossible to form a precise picture of this process, the epigraphic evidence is useful for highlighting its main trends. The histogram in Figure 3 charts the 329 datable inscriptions identified.Footnote 70 The periods considered vary in length because the dating of an inscription is sometimes very uncertain, but also because some periods that might be seen as coherent (such as the “Tetrarchic period,” or the “Theodosian dynasty”) would have to be divided otherwise. The chart also shows changes in the average number of statues dedicated each year for all periods, providing a clearer sense of the evolution of the habit.

Fig. 3. Distribution of dedications per period (with annual average).

We have no clear picture of how these numbers compare with the 3rd c. CE in Rome. Silja Spranger showed that the traditional image of a dramatic Empire-wide decline after the Severan dynasty is misleading, and we should be careful in assuming a strong contrast between the two periods.Footnote 71 Nevertheless, it seems clear that the beginning of the Tetrarchic regime was marked by a significant spike in this practice in the urbs, and the average number of statues erected each year actually rose during the period between the death of Constantine (337 CE) and the accession of Theodosius in 379 CE (from 2.09 to 2.66 per year).Footnote 72 The number of dedications declined sharply after that, eventually disappearing in the later part of the 5th c. This is a process that took place in other parts of the Roman world as well.Footnote 73 What makes Rome stand out is both the duration and scale of the habit into this later phase. We should also bear in mind that the areas of the city for which we are better informed, such as the Roman Forum and the Forum of Trajan, are also areas that retained some of their ceremonial use for longer (and whose statue collection continued to be updated until the end of our period). In other words, if anything, the evidence available underplays the importance of the break between the 4th and 5th c. CE.

Any picture of the evolution of the statue habit should take into account the fact that, rather than evenly distributed, the erection of dedications was concentrated in particular moments in the history of the city. The imperial visit of 303 CE, military triumphs, and the inauguration of major building works like the restoration of the Forum probably accounted for a large number of the Tetrarchic dedications. Later imperial visits were similarly the context for important campaigns of dedication, such as when Constantius II sojourned in Rome in 357 CE.Footnote 74 Prefects and other officials could also follow a systematic policy of dedicating statues as a form of celebrating the city's sculptural heritage and spaces.Footnote 75 The urban prefect Fabius Titianus (in office from 339 to 341 CE) dedicated seven statues with unstated subjects in the area of the Forum.Footnote 76 A few years later, the former prefect and consul Naeratius Cerealis celebrated the inauguration of his baths on the Esquiline with another series of dedications, 10 of which survive.Footnote 77 In 377 CE the prefect Gabinius Vettius Probianus then dedicated nine statues (also to unstated subjects) in the Forum.Footnote 78 As a result, just three officials were responsible for 26 out of the 112 dedications made between 338 and 379 CE; roughly 23% of the dedications made during this period took place in three years. These relatively large-scale campaigns of dedications continued into the 5th c. CE: the urban prefect Petronius Maximus set up three statues to unstated subjects in 420–21 CE, and Fabius Felix Passifilus Paulinus, also a prefect, was responsible for five dedications between 450 and 476 CE.Footnote 79

The chronological distribution of statue dedications made in Rome reveals a fundamental departure from Early Imperial practice. As the number of dedications made per year declined, the setting up of statues became an increasingly extraordinary occasion. This development had two consequences. In the first place, the statue habit can be said to have ended in the last quarter of the 4th c. CE, when the number of statues dedicated per year became too small to be considered a recurring practice. At the same time, as dedications became rarer, so did the honor of having a statue erected in Rome. Being represented in marble or bronze, whether in the Forum of Trajan or in the atrium of an aristocratic domus, was now a more exclusive distinction than it had been in previous periods. Before offering a proper explanation for these changes, however, it is necessary to consider how the identity of honorands and awarders evolved in Late Antique Rome, as a way of understanding the social dynamics behind them.

Honorands

The choice of whom to honor with a statue became more significant in a context of fewer dedications. In this sense, the evolution of Rome's statue habit in terms of the identity of the honorands is particularly revealing. As Table 1 shows, although imperial monuments accounted for the largest number of dedications overall, the frequency with which the ruling power was honored declined significantly after the death of Constantine. As mentioned above, emperors had accounted for the largest share of honors in Rome since the time of Augustus.Footnote 80 The imperial house continued to be an important focus of loyalty until the beginning of the 5th c. CE, a position that was confirmed in the overblown language of these dedications. However, imperial dedications almost disappear from the record after that – paradoxically, at a time when the court was more present in Rome than any time in the previous century.Footnote 81 There are only two dedications datable to the period between 424 and 455 CE (9.4% of the total dedicated in this period) and none for the years between 456 and 493 CE. Although there were certainly more statues than this – as suggested by the three surviving portraits of the so-called Ariadne (early 6th c. CE), for example – the declining trend is clear.Footnote 82 It is likely that such an early reduction of imperial statues was related to broader developments in the nature and presentation of the imperial office, a process that involved the establishment of new sources of legitimacy and new forms of political celebration.Footnote 83 The decline of imperial images is more striking because statues continued to be used to express the political realities of the time: as the dedications to Stilicho, Aetius, and Merobaudes show, this honorific language was flexible enough to incorporate new types of leadership.Footnote 84

Table 1. Statue dedications per category of honorand by period

If the impact of political changes seems straightforward, that of Christianity is more complex. There is a decline in the number of statues dedicated to priests as priests – that is, those that focus on the holding of a priesthood as the main reason for the honor. This decline took place in the first decades of the 4th c. CE, however, before the spread of Christianity could have had any influence in the making of these awards. Statues of Classical deities, on the other hand, were still set up in the 5th c. CE, and it is likely that at least some of the statues moved to new places or restored represented religious subjects.Footnote 85 Although statues of gods acquired an increasingly ambiguous standing in Christian circles, officials all over the Empire remained committed to preserving these objects, whether for purely aesthetic or historical reasons.Footnote 86

There is a very clear change, however, in the number of dedications to aristocrats (101 out of 372, totaling 27.2%). Although I have included here courtiers like Claudian, the majority of these statues celebrated members of the senatorial order who were permanently or temporarily resident in Rome.Footnote 87 The importance of these dedications grew in the years that followed the reign of Constantine, reaching 32.1% of all dedications made between 338 and 379 CE (more than imperial dedications), and continued to grow in the following periods, until the end of the 5th c. CE. Many of these were placed in domestic contexts,Footnote 88 leaving public spaces dominated by imperial images, but it is significant that – at a time when the number of dedications started to decline – the political decision to award these monuments was more often directed at members of the powerful local senatorial elite than at the imperial court.

The rise in the number of aristocratic monuments should be treated with caution. Emperors were involved in a number of these initiatives and especially in the most prestigious ones in the Forum of Trajan; although they did not act in isolation, the preeminence of the court was very clear to all agents involved.Footnote 89 Nevertheless, it is also clear that the combination of statue monument with an inscribed base (detailing who dedicated it and to whom) was increasingly seen as an honorific language appropriate to speak of and to members of the aristocracy. Members of this social group were particularly fond of these monuments, as we saw in the previous section, and their involvement in city life ensured that local awarders concentrated their attention on them. The role played by members of the senatorial aristocracy is clear, especially when we consider their increasing presence in the dedications made in cities across Italy, where they came to replace emperors and members of the local elite as the main honorands.Footnote 90 This was in clear contrast to Early Imperial practice, when a much larger number of statues was dedicated to emperors than to senatorial aristocrats.Footnote 91

We might ask how peculiar Rome was, in this sense, when compared to other cities and parts of the Empire. Constantinople would be an interesting place to start this comparison, as aristocratic monuments probably also played an important role in the city's rich statuary corpus.Footnote 92 Unfortunately, our knowledge about dedications is almost entirely based on written sources such as the Parastaseis and the Patria, and is therefore of an entirely different nature, making comparisons of very limited use. The LSA database records only 20 dedications to imperial and senatorial office-holders in the eastern capital, but 132 for emperors and members of their family. Imperial dedications dominate the evidence in North Africa, too, and are also widely spread through different types of settlements (from provincial capitals to minor towns). The only exception seems to be Lepcis Magna, where the number of dedications to governors, senior officials, and members of the local elite was also very high, 39 out of a total of 76 dedicatory inscriptions – a pattern that was closer to Rome's.Footnote 93 The evidence from Aphrodisias also provides us with elements for comparison: as a provincial capital, the city was an important political center in Late Antiquity, and urban life there shows important signs of vitality well into our period.Footnote 94 More significantly, it remained an important center for the production of new sculpture. Here, of 40 Late Antique bases found, 8 are imperial dedications. Local notables were honored on 9 occasions, and high imperial officials were celebrated in 15 monuments.Footnote 95 In other words, although the local elite remained an important element in city life, representatives of imperial power attracted most of the attention.

This brief and unsystematic comparison highlights the peculiarities of the Roman case. The enormous disparity in numbers is perhaps the most striking difference: many more statue bases were dedicated in Rome than in any other city of the Empire. This does not necessarily mean that Rome's Late Antique sculptural collection was richer than that of 6th-c. CE Constantinople, for example, but it shows that Romans were particularly active in recording their dedications in a very traditional way (as well as the scale of archaeological work in the city). Rome was similar to other cities, however, in the sense that a large proportion of statues commemorated imperial power. This is easy to understand: the city was an important political center, had immense symbolic value, and was visited by different emperors during the period. What makes Rome especially interesting for us is the number and nature of aristocratic dedications. In places like Aphrodisias and Lepcis Magna, where many non-imperial dedications were made, these were primarily honoring imperial officials, and not the local elite. In Rome, the senatorial aristocracy was in the unique position of being both representative of the imperial government and the local elite, receiving a large, and increasing, proportion of statues.

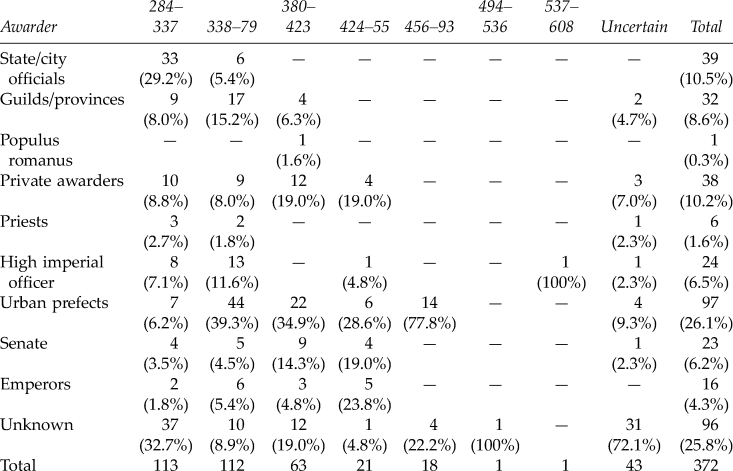

Awarders

The evolution of Rome's statue habit can also be seen in terms of who was responsible for setting up these monuments. As we can see in Table 2, a wide range of awarders is recorded between the end of the 3rd c. and the last quarter of the 4th c. CE. These included city and state officials of senatorial and equestrian rank, who honored emperors and members of their families; guilds and provincial groups, primarily concerned with their aristocratic patrons; and priests and private awarders, including relatives, clients, and even a slave.Footnote 96 One striking illustration of the openness of the statue habit in this earlier phase is the large number of dedications made by state and city officials (33 in total), especially in the Roman Forum – probably the most prestigious venue for such initiatives.Footnote 97 Members of the elite were also involved, such as high imperial officials, the Senate, and emperors.

Table 2. Statue dedications per category of awarder by period

This remarkably open degree of participation declined during the middle decades of the 4th c. CE: guilds and provincial groups remained active until approximately 380 CE, but priests and officials (city and state) disappeared from the record earlier. Private awarders remained important; in fact, their relative presence increased between the 4th and 5th c. CE (from 8.8% to 19.0%). However, the actual social composition of this group changed, becoming restricted to members of aristocratic families honoring their relatives. This is the case for the statues set up by the former urban prefect and consul Anicius Acilius Glabrio Faustus to his ancestors in the forum built by his father in the northern Campus Martius.Footnote 98 Another striking example is the monument set up to Iunius Quartus Palladius by his brother in their house (probably on the Aventine), sometime between 416 and 421 CE: “Because of the strong affection of their kinship, and for the adornment of his house, his brother considered it fair to place and set up a statue of him among himself and his family.”Footnote 99 The monument was primarily a family affair: dedicated by an unnamed brother, in the family home, surrounded by likenesses of important ancestors, the statue celebrated the formidable career of Palladius and the standing of his family (including the brother who dedicated it, by association). It is an example of family promotion, rather than just an expression of gratitude or loyalty.

Emperors and the Senate awarded monuments to generals and important aristocrats in the most prestigious spaces of the city, such as the Roman Forum and the Forum of Trajan.Footnote 100 It is clear, however, that ultimately Rome's Late Antique statue habit was dominated by the figure of the urban prefect. Although responsible for a relatively small number of dedications in the late 3rd to early 4th c. CE (with just over 6% of all dedications), the role of prefect was dramatically changed as his remit was reformed and different offices came under his authority. Prefects played a crucial part in shaping the city's population of statues after that.Footnote 101 Even the office of curator statuarum, directly related to this practice, only appears in a single dedication from this period.Footnote 102 Benjamin Anderson recently observed that the dedication of imperial statues in other parts of the Empire was monopolized by the highest imperial officials by the 6th and 7th c. CE.Footnote 103 The case of Rome confirms this trend, while showing that it started earlier – in the 4th c. CE – and that other types of dedication were progressively controlled by the most prestigious awarders: the court, the Senate, and (most conspicuously) the urban prefect. It is this process of increased aristocratic eagerness for statues and official control over dedications that we must now consider, if we want to understand the end of the statue habit in Rome.

The end of the statue habit

Although an Empire-wide phenomenon, the decline of the statue habit was marked by fundamental regional differences, each with its own history.Footnote 104 In Rome, the practice of setting up statues lost its “recurring, socially diffuse” character in the last quarter of the 4th c. CE, when it declined quickly and abruptly. Already visible after 380 CE, this process became evident from the death of Honorius (423 CE) onward, when less than one statue (0.65) was dedicated per year on average. Decline was accompanied by a different set of priorities on the part of awarders, with a renewed focus on the city's heritage and elite. Most importantly, as the diversity of agents involved in the setting up of statues declined, the social mechanism that had been responsible for the Classical statue habit disappeared.Footnote 105 This was a revolution in the social practice of acknowledging honors through statues, now limited to a very narrow social group. This is suggested by a law of Theodosius II and Valentinian III, which, although referring to Constantinople, highlights developments that were also taking place in the West:

It is both fitting that prizes for virtue should be granted to those deserving them, and that the honors of some should not lead to damage to others. Therefore, whenever a statue is offered by any collegium or office in this most sacred city [Constantinople] or in the provinces to one of our judges or to someone else, we do not allow the expenses to be collected from apportionment, but from him for whom the honor was requested, and with whose own funds we order the statue to be dedicated.Footnote 106

The idea that honorific statues, even when offered by a guild or a provincial city, should necessarily be paid for by the aristocrat and/or official being honored represented a dramatic shift in the Classical economy of honors. It was common for generous benefactors, in earlier periods, to cover the cost of honors voted on their behalf.Footnote 107 The law of Theodosius II and Valentinian III, however, made this transaction an obligatory element in the dedication of a statue, acknowledging the pressure represented by such monuments on the financial realities of non-elite awarders. The Classical statue habit ended when statues ceased to function as an element in the exchanges between subjects and rulers, or between clients and patrons. Instead, they were now set up by members of the topmost elite to their associates and peers. The end of the statue habit was therefore an aspect of broader changes in Roman political life, as power and honor became more associated with the imperial court, and senators asserted their dominance over Rome and its spaces.Footnote 108 The statues set up from the late 4th c. CE onwards reveal new priorities, expressed through different social mechanisms, and fulfilled new functions in Roman society – and this is what we need to explore next.

The Late Antique culture of statues

The end of the statue habit did not entail the end of statue dedications, and sculpted monuments remained an important feature in the cityscape. In the Roman Forum, for example, the restoration and rededication of older monuments contributed to the recreation of Rome's past, emphasizing civic identity and the city's unique cultural and political standing.Footnote 109 As Robert Coates-Stephens has shown, statues were preserved, moved, and rededicated in new settings, creating new sculptural ensembles and adding meaning to different parts of the city.Footnote 110 Prestigious monuments were removed from view and stored, presumably during times of military or civil troubles that disturbed the city in the 5th c. CE.Footnote 111 Describing Rome's splendors, the chronicle of Pseudo-Zachariah Rhetor records 80 statues of gods in gold, 64 in ivory, 31 large pedestals of marble, 3,785 statues of emperors and commanders, 25 bronze statues of kings of the house of David and other figures in ancient Jewish history brought from Jerusalem by Vespasian, and two colossal statues – a list that is as impressive as it is (presumably) incomplete.Footnote 112 The Ostrogothic court, in the 6th c. CE, still appointed an official explicitly in charge of looking after Rome's statues.Footnote 113 Procopius of Caesarea, who visited the city toward the middle of the 6th c. CE, thought it worthwhile registering the statues by famous Greek sculptors that he had seen in the Temple of Peace.Footnote 114 More importantly, statues were still considered suitable monuments to honor important senators, the Ostrogothic king Theoderic, and even (by the end of our period) the Byzantine ruler Phocas. The continued significance of statues in spite of the end of the statue habit raises the issue of how we should see these monuments and how can we characterize Late Antique Rome's culture of statues.

As mentioned in the introduction, scholars have traditionally focused either on honorific monuments as evidence for political change or on restored statues as an indication of civic pride and care for the city's heritage.Footnote 115 However, in order to understand the role and meaning of statues in Late Antique Rome, it is necessary to consider these two types of dedication as part of the same culture.Footnote 116 Urban prefects played a key role in this area. In the middle of the 5th c. CE, Rufius Valerius Messala dedicated a statue of Victoria as an ornament in the Vicus Patricius.Footnote 117 A few decades later, Anicius Acilius Aginatius Faustus dedicated a simulacrum of Minerva “for the happiness of the times” as part of the restoration of the Atrium Minervae, a structure founded by Augustus at the entrance of the Senate House in the Forum.Footnote 118 At a time when Christianity played a major role in urban life, these prefects chose to emphasize the pagan identity of the statues, rather than leaving the subject unstated. Victoria and Minerva were deities who played an important role in Rome's history and identity, and these prefects explicitly acknowledged their importance.Footnote 119 In the second half of the 5th c. CE, the urban prefect Fabius Felix Passifilus Paulinus dedicated two statues with unstated subjects in the Athenaeum, a space of learning and culture, “with his special care” (studiis suis).Footnote 120

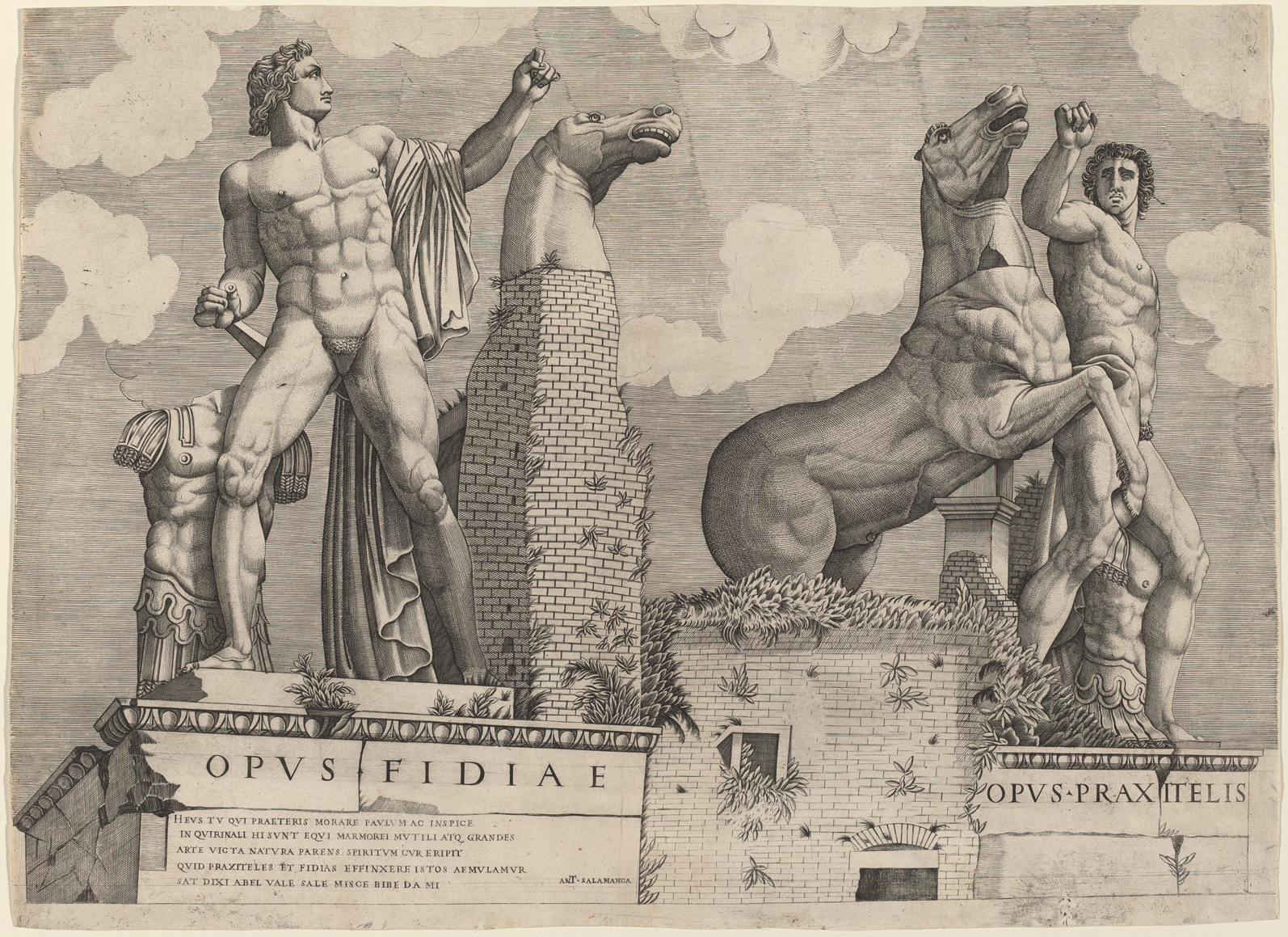

As these examples indicate, antiquity was one of the primary reasons why statues were treasured in Late Antique Rome.Footnote 121 Identifying the sculptor of a particular work as a prestigious artist from the past was a favored way of highlighting this aspect. In the early 4th c. CE, for example, the consul Gallus dedicated a statue of Bacchus by Euphranor, a 4th-c. BCE sculptor, who according to Pliny had statues on display in various prestigious venues in Rome.Footnote 122 It is in this context that we should see a group of inscribed bases (or, more properly, plinths) that offer no other information than the name of the sculptor, such as Opus Polyclit[i], Opus Praxitelis, [O]pus Tim[a]rchi, found in the Roman Forum near the Basilica Iulia.Footnote 123 Although the inscriptions record no precise indication about the date of these dedications, scholars agree that the style of the letters belongs to the Late Antique period, with suggestions varying from the end of the 3rd to the 5th c. CE.Footnote 124

The most probable date for the Forum plinths is the late 4th–early 5th c. CE: that is, either contemporary with or soon after Probianus's campaign of dedications in that same area. This is further suggested by the context of dedication of two such bases that support colossal statues of the Dioscuri in Piazza del Quirinale, on the Quirinal hill (Fig. 4). Although the statues are datable to the late 2nd–early 3rd c. CE (possibly commissioned under Caracalla for the nearby temple of Serapis), the inscriptions identify them as works of the Greek sculptors Praxiteles and Phidias.Footnote 125 Before being moved to their current spot in 1589, the statues and their bases were part of a monumental structure that sat in that same area, as we know from two contemporary drawings.Footnote 126 The Italian sculptor Flaminio Vacca, who witnessed the destruction of the ensemble and the removal of the statues, observed that the basement on top of which they were located was entirely built of spoliated material, most likely from the Severan temple of Serapis (identified by him as frontespizio di Nerone).Footnote 127 Although we should be careful in accepting the identification of a monument whose position still eludes scholars, the use of spolia is relevant. As Coates-Stephens observed, the most likely date for the construction of a monument built with reused material taken from any temple would be the middle of the 5th c. CE, when the urban prefect Petronius Perpenna Magnus Quadratianus restored the adjacent Baths of Constantine, probably when the inscribed bases were themselves produced.Footnote 128

Fig. 4. The statues of the Dioscuri on the Quirinal, engraving by Antonio de Salamanca, before 1546. (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum. Source: http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.169702 Creative Commons CC0 1.0.)

The Late Antique process of restoring and embellishing the spaces of the city involved the creation of new associations with the past, emphasizing the splendor of Rome's heritage – and statues were a key component in this. The process has also been observed for other cities in the Empire, such as Athens.Footnote 129 What was specific to the urbs – and Athens was one of the very few comparable sites – was the wealth of associations offered by the city's history and monumental heritage. This is highlighted by the base of a statue discovered in the 19th c. near the church of S. Angelo in Pescheria, in the area of the ancient Porticus Octaviae (now in the Capitoline Museums).Footnote 130 The statue on this base was originally dedicated in 146 BCE in honor of Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi and daughter of Scipio Aemilianus. The surviving base is of Early Imperial date, and it records a rededication of the statue in the Augustan porticus at the time of its inauguration. It is very likely that the statue itself, described by Pliny the Elder as in a sitting position (HN 34.31), was damaged by one of the fires that affected the area, especially in 80 and 191 CE; another inscription was added to the base at a much later date, identifying it as an Opus Tisicratis.Footnote 131 The attribution of a Republican portrait (or perhaps a much restored version of it) to a Hellenistic sculptor is a fascinating example of Late Roman antiquarianism and how new “ancient” identities could be ascribed to old monuments. Educated aristocrats showed great interest in the antiquities and history of the city, and Rome's magnificent collection of statues played an important part in this.

Whether real or imagined, antiquity was a defining element through which Late Antique Romans conceived and approached statuary. It is in this perspective that the continued importance of honorific statues can be best understood. Sculpted portraits traditionally played an important part in the creation and preservation of different types of memories, according to their setting. Likenesses of old and recent emperors occupied the Roman and imperial fora, side by side with images of deities and aristocrats that celebrated past events, becoming themselves prized for their old age, while images of ancestors and living relatives decorated the houses of powerful families, as we saw above.Footnote 132 The trans-historical character of these dedications is acknowledged in the very language of epigraphic texts. In the early 4th c. CE, the people of Sicily honored their governor Betitius Perpetuus Arzygius with “the eternal monument of a statue, to serve as a record for future generations.”Footnote 133 In the Forum of Trajan, a statue of Flavius Taurus was probably awarded by Constantius II, removed during his exile under Julian, and rededicated during the reign of Valentinian I and Valens, “for the perpetual memory of this man worthy of praise.”Footnote 134

Combining a dedicatory inscription with a physical likeness, statues established a specific relationship with the past by virtue of their own presence in the different spaces of the city. Imperial monuments might have looked more or less similar to those of their predecessors nearby, while the actual inscriptions emphasized specific terms of comparison: Maximian was praised as “superior to all previous emperors” in the Forum (a bold claim for Diocletian's colleague in the Tetrarchy), while Theodosius surpassed “the clemency, blessedness, [and] munificence of earlier emperors,” according to a dedication by the prefect Sextus Aurelius Victor in the Forum of Trajan.Footnote 135 Non-imperial subjects could also be praised in comparison with the past, as in the case of Coelia Claudiana, chief Vestal Virgin, who was celebrated as “most blessed, most scrupulous, and most pious above all previous” holders of the same office.Footnote 136 Palladius, consul in 416 CE and praetorian prefect between 416 and 421 CE, was said to have “surpassed the honors of his ancestors” in the dedication of the statue set up by his brother in the family home.Footnote 137

More often than competing with the past, statues worked by associating their subjects with them. The emperor Maxentius was praised in the vicinity of the Basilica Iulia as a man “of old-fashioned morals” by an unknown awarder.Footnote 138 In 400 CE, Cheionius Contucius was honored in his house for being “an illustration of his ancestry both through his outstanding deeds and rare example of old-fashioned sanctity.”Footnote 139 He was not only a representative of his ancestors but also embodied their values. Two decades later, the even more distinguished (and future emperor) Petronius Maximus was celebrated by the court at the request of the Senate with a statue in the Forum of Trajan, because he was “embellished by the equally distinguished titles of his grandparents and ancestors.”Footnote 140

Statues articulated past and present, marking a man's (or, less often, a woman's) glory by associating them in appearance, words, and setting with the heroes of old – the characters who peopled the accounts of historians, the verses of poets, and the porticoes of public squares and houses. This explains why the prefect Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, when announcing to the court that the Senate had decided to dedicate equestrian statues to Theodosius the Elder (the father of the ruling emperor) in 384 CE, described it as consecrating him “among the names of ancient times.”Footnote 141 As Peter Stewart observed, the dedicatory inscription of the statue awarded to Flavius Merobaudes in the Forum of Trajan highlights this historical character, recording that it was “a statue made of bronze, by which times of old used to honor men of rare example, who had been tested in military service, or were the best of poets.”Footnote 142

It is in this context that we should read Ammianus's criticism of senators and their appetite for statues, when he observes:

And they take pains to have [statues] overlaid with gold, a fashion first introduced by Acilius Glabrio, after his skill and his arms had overcome King Antiochus. But how noble it is, scorning these slight and trivial honors, to aim to tread the long and steep ascent to true glory, as the bard of Ascra expresses it, is made clear by Cato the Censor. For when he was asked why he alone among many did not have a statue, he replied: “I would rather that good men should wonder why I did not deserve one than (which is much worse) should mutter ‘Why was he given one?’”Footnote 143

It is with the likes of Acilius Glabrio and Cato that Roman senators desiring a statue should be compared, because these were the people who were honored in this way (or, in the case of Cato, who chose not to be). Stewart pointed out that, by the early 4th c. CE, the dedication of honorific statues had become a less familiar practice, being associated with ancient times.Footnote 144 In the case of Rome, this process only took place decades later, as the statue habit declined; more importantly, it shows how, in spite of being dedicated in fewer numbers, statues continued to play a meaningful role in Late Antique cultural and political life.

It is not just that the practice of setting up statues was seen as an ancient and therefore worthy practice: through their very material form, statues provided a veneer of ancient respectability to honorands, removing them from the present and associating them with the leaders that were on display in that same area. This is suggested by the sculptural evidence for non-imperial statues that survives from Late Antique Rome. Whereas in places like Aphrodisias new statues continued to be produced, the standard practice in Rome was to combine a reworked portrait head with a 2nd- or 3rd-c. CE statue wearing the traditional toga, with sinus (the descending lower edge) and umbo (see Fig. 2).Footnote 145 Unlike the situation in Eastern cities and the evidence provided by other media in the West, the Late Antique toga seems not to have been common in Roman portraits, with only two surviving statues attesting to its adoption in Rome (Fig. 5).Footnote 146 For members of the Roman elite, it was more important to be seen in a traditional costume than as embracing the new, probably court-oriented fashion.

Fig. 5. Aristocrat wearing the “new-style toga” (s.c. “The old magistrate”), c. 400 CE. (Rome, Musei Capitolini, Centrale Montemartini, MC896. Photo © Roma – Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Comunali.)

The combination of older statues and Late Antique heads was certainly not limited to Rome.Footnote 147 The new heads expressed personal virtues and values through changes to the eyes, facial features, and hairstyle.Footnote 148 The older bodies operated in a different way, activating old notions of Roman-ness and senatorial identity through the use of the traditional toga.Footnote 149 Statue monuments were thus able to express the political and social values of the age while at the same time associating the individuals honored with the Early Imperial elite. Late Antique Romans who looked at the collection of statues on display at the Forum of Trajan were thus presented with the image of an elite that was not only politically unified, but that – by “wearing” the same bodies – inhabited a single temporality, a transhistorical dialogue that continued in the inscriptions.

That the decision to reuse Early Imperial statues to honor late 4th- and early 5th-c. CE aristocrats was a choice is suggested by the fact that members of the Roman elite were well aware of the changes in fashion taking place in this period. Scholars have written of the Late Antique style of toga, and its quick spread among members of the imperial and senatorial elite in the East.Footnote 150 These developments were known in Rome too, as demonstrated by other media and by the statues of the older and younger magistrates (Fig. 5). Although the reuse of earlier statues was not a new development, being celebrated in the way “by which times of old used to honor men of rare example” (to quote Merobaudes's inscription) became a more poignant statement as the dedication of statues became rarer.

Conclusion

Sometime between 534 and 536 CE, the Ostrogothic king Theodahad addressed a letter to the urban prefect Honorius, instructing him to restore the bronze statues of elephants that threatened to collapse in the Via Sacra. The letter, written by Cassiodorus, describes in great detail the wonderful character of these animals, including their long lives, prodigious memory, and invulnerability.Footnote 151 Cristina La Rocca and Yuri Marano recently suggested that these elephants might have been moved from the ancient Porta Triumphalis, located in the modern area of S. Omobono, a monumental archway or gate topped by two bronze quadrigae pulled by elephants.Footnote 152 This cannot be proved, but the association between statues of elephants and the celebration of triumph in a Late Antique context is highly plausible: the late 4th-c. CE Historia Augusta mentions the dedication of statuas cum elephantis by the Senate to Maximus, Balbinus, and Gordian III, celebrating their victory over the tyrant Maximinus Thrax.Footnote 153 Although this is probably a fabrication in a notoriously unreliable work, it shows that this type of monument was associated with military victories. In spite of these associations, however, Cassiodorus's letter overlooks this tradition, concluding that the loss of these monuments should not be accepted, since “it is proper of the dignity of Rome to store, through the ability of artists, what nature's wealth has created in the different parts of the world.”Footnote 154

The decline in the number of honorific monuments dedicated in Rome during Late Antiquity meant that most of the statues visible in the city, whether honorific or not, referred to events and heroes from a distant past. These monuments therefore became open to new interpretations, sometimes based on antiquarian knowledge (as in Symmachus's reference to the statue dedicated inter prisca nomina), but sometimes based on pure speculation.Footnote 155 Cassiodorus's interpretation of the elephants on the Sacra Via was probably related to these developments: the statues were still worthy of attention and care, even when perceived in different cultural terms. Procopius provides a fascinating example of this process, when he observes that a statue of Domitian on the Clivus Capitolinus – where a temple had been dedicated to Vespasian, the emperor's father – was an accurate copy of a model made from the reassembled pieces of the emperor's flesh.Footnote 156 It is worth asking, in this context, to what extent the awarders of a statue to the Ostrogothic king Theoderic or (even later) the emperor Phocas in the Forum (in this case by an Eastern official, but certainly with the support of locals) understood a system of honors developed during the Late Republic in the same terms as their ancestors.

As the discussion in the preceding pages has shown, the evolution of the statue habit can only be understood when considered in its broader social and cultural context. Romans continued to dedicate statues in a systematic way well into the 4th c. CE. Through their material, iconography, and setting, statue monuments offered a rich and sophisticated language that allowed the expression of new social and political realities in a traditional fashion. Roman senators, with their clients, offices, and political ambitions, were the great movers of the Late Antique statue habit, whether as honorands or as awarders. As the language of statues became more associated with the priorities and self-perception of Roman aristocrats, groups that until the reign of Constantine had remained active in using them as part of a wider social and political dialogue seem to have grown increasingly silent. These interrelated processes are at the root of the abandonment of the statue habit in the last quarter of the 4th c. CE.

As fewer social groups were involved in the award and dedication of these monuments, their traditional function as “lubricators” of sociopolitical relations lost relevance, whereas their role as “exemplars of noble behaviour and statements of historical identity” gained increased prominence.Footnote 157 In this process, new identifications were attributed to old works of art that had been moved to new locations within the city; statues were still cataloged and counted by concerned authorities and continued to bedazzle visitors. These developments were not exclusive to Rome: in late 4th-c. CE Verona, the governor Valerius Palladius moved a statue that had lain neglected in the Capitol to the Forum, a “most frequented place.”Footnote 158 In Catina (modern Catania), in Sicily, the statue of the mythical “pious brothers” was moved in the 5th c. CE from its original location to the theater by the provincial governor.Footnote 159 In Constantinople, where statues were amassed from different parts of the Empire, statue monuments were listed and praised by different authors, generating an entire body of literature.Footnote 160 It has been observed that 8th-c. CE Byzantine writers (such as the author of the Parastaseis syntomoi chronikai) reveal a profound lack of knowledge of the visual vocabulary of ancient statues, a “matter for study and (often erroneous) interpretation.”Footnote 161 Rather than mistakes, however, these cases are revealing of a creative process of reinterpretation that began much earlier, and must have affected Rome as well as Constantinople.

In the old capital of the Empire, the antiquarian dimension of statues and statue dedications had important implications for the way in which the city's hierarchy of honors worked, for as long as honorific statues continued in use. In the political context of the late 4th and early 5th c. CE, when an increasingly limited number of senators was celebrated in this way, this represented a very special distinction indeed. Although the language of inscriptions and the iconography of these monuments reiterated the traditional values of the senatorial class as a whole, statue monuments singled out the most extraordinary individuals within this group, removing them from the political vicissitudes and competition of their own time and making them comparable to the nobility of the past. To be honored with a marble or bronze effigy at home or in the Forum showed that members of the Roman aristocracy were not just distant heirs, but actual members of a timeless elite that stretched back for hundreds of years. By the end of the 5th c. CE, when they virtually ceased to be dedicated in Rome, statues had been turned into cultural icons. Before this happened, however, as the statue habit died and this practice was finally abandoned, they acquired a new importance in Roman culture and society.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Robert Coates-Stephens, Ulrich Gehn, Paolo Liverani, Silvia Orlandi, Bert Smith, Ignazio Tantillo, and Bryan Ward-Perkins, as well as the reviewers for JRA, for observations and suggestions. This article was originally presented as a lecture at the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut in Berlin in June 2018, and I would like to thank Philipp von Rummel and all his colleagues at the institute for the invitation and hospitality.