Introduction

Korean popular music, or K-pop, flows along two transnational streams of commodified culture. On the one hand, it engages with globally consumed youth genres such as hip hop, R&B, and electronic music (Alim, Ibrahim, & Pennycook Reference Alim, Ibrahim and Pennycook2008), while on the other hand, it participates in hallyu, or the burgeoning ‘Korean wave’ of music, television, and technology consumed across Asia and beyond (Shim Reference Shim2006; Chua & Iwabuchi Reference Chua and Iwabuchi2008). Like cultural objects of both streams, K-pop exhibits properties of arguable novelty, including rapid mobility through social media, broad accessibility across national boundaries, and deep connections to capitalist processes. It is thus unsurprising that this highly mobile genre is tugged by disparate language norms. While marketed as distinctly ‘local’ to South Korea, with most songs performed in Korean, it also displays a salient ‘global’ orientation. Notably, K-pop lyrics are commonly adorned with bits of English (Lee Reference Lee2004), and sometimes even Chinese, French, and Spanish. Likewise, performers sometimes use English stage names—for example, Tiffany, T.O.P., and Rain—and address their audiences in English, Chinese, or Japanese. In short, as a transnational commodity par excellence, K-pop is characterized by a complex semiotics, one that seemingly transcends traditional constructs of race, nation, and language, perhaps even dismantling them in the process (Shim Reference Shim2006; Ryoo Reference Ryoo2009).

In this article, I explore the negotiation of the linguistic tugs between Korean and English, specifically on YouTube, a transnational media space where K-pop fans, many with marginal knowledge of Korean, frequently participate in video-viewing experiences with other fans. My analysis focuses on interactions that emerged in the context of eleven ‘reaction videos’ posted by Cortney and Jasmine, two avid fans who documented their real-time affective responses to K-pop music videos. These women, like K-pop fans on YouTube more generally, depended primarily on spoken English, yet in the course of referring to specific performers, they sometimes came to utter Korean names. I examine the semiotic processes of how these Korean utterances came to be heard as hybrid by their viewers, how viewers invoked various ideological frames when evaluating hybridity, and how local language practices and interpretations were shaped across interdiscursive chains of social action. By analyzing eighty-four metalinguistic comments posted across thirty-three months, alongside spoken discourse in the videos themselves, I show not only how disparate ideologies about hybridity circulated in this community but also how ideological stances traveled across pathways of contextualization (Wortham & Reyes Reference Wortham and Reyes2015) and how transnationally mediatized language (Agha Reference Agha2011) came to be heard as shibboleths of recognizable cultural models of K-pop fandom (cf. Moore Reference Moore2011). I also illustrate how these metalinguistic assignments of value subsequently regimented local language practices.

Central to my analysis is an understanding of hybridity not as an objective fact but as a cultural status that depends on its contextualization in discourse (Hill & Hill Reference Hill and Hill1986). My examination of metalinguistic comments shows how acts of hybridization overwhelmingly depended on, rather than subverted, an ideology of idealized purity, or linguistic absolutism. According to this absolutist view, the ideal K-pop fan in this transnational YouTube space pronounced names according to the phonology of the language to which it belonged: Korean names were to be pronounced as Korean words, and English names as English words. As such, contrary to images of hybridized Korean popular culture as potentially dismantling traditional linguistic constructs, this centripetal ideology oriented members of this K-pop fan community to normative centers of pure Korean and English. I also show how K-pop fans maintained this ideology through various metapragmatic actions, such as prescriptive acts of correction, conditional acts of toleration, and transgressive acts of stylization, despite sometimes challenging this ideology through authorizations (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz, Hall and Duranti2004) of hybridity that invoked competing relativist and pluralist assumptions. Finally, focusing on the specific case of the Korean stage name Taeyang, I examine the trajectory of discourse that emerged once fans contextualized Cortney and Jasmine's pronunciation of this name as undesirably incorrect and hybrid. I argue that acts of hybridization not only complemented absolutist ideologies but also nudged Cortney and Jasmine's language towards its eventual purification.

Language, hybridity, and ideology in transnational space

K-pop may exhibit forms of language often felt to be novel, yet the semiotic analysis I present in this article speaks to an enduring sociolinguistic issue, namely, how speakers make sense of linguistic hybridity, or practices that seemingly straddle language boundaries. An important strand of this research has focused on the juxtaposition of words belonging to different language varieties. This vast scholarship, often classified as studies of ‘code-switching’ (Gumperz Reference Gumperz1977), has tended to examine how such lexical juxtapositions can constitute strategic moments of social action (e.g. Rampton Reference Rampton1995; Zentella Reference Zentella1997; Woolard Reference Woolard1998; Lo Reference Lo1999; Bailey Reference Bailey2000; Jaffe Reference Jaffe2000), particularly in global genres, including hip hop, that may challenge dominant language ideologies (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2003; Lee Reference Lee2004; Low, Sarkar, & Winer Reference Low, Sarkar and Winer2009). Yet a second strand of hybridity research—even if not recognized explicitly as such—has examined how sounds from one language can be embedded within words from another, lending these words a certain ‘flavor’ or even a more robust ‘accent’ (Urciuoli Reference Urciuoli1996; Lippi-Green Reference Lippi-Green1997; Rosa Reference Rosa, Rolón-Dow and Irizarry2014).

A few crucial observations might be made across these studies. First, a single hybrid form can be contextualized in a range of possible ideological frames and interactional footings. In some cases, hybridity can be heard as an unintended ‘error’—a ‘funny foreign accent’—that reveals an indelible remnant of a speaker's personal history and habits (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Thompson1991), while in other cases, it can be heard as a sincere emblem of aspiration (Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz1999; Cutler Reference Cutler1999), a stylized flourish for authentication (Coupland Reference Coupland2001), or a mocking caricature within a comedic frame (Chun Reference Chun, Reyes and Lo2009). Even within a single cultural context, the same hybrid language may invoke divergent cultural personas; the same accent may be heard as a creative, cosmopolitan splash in one instance yet heard as a disorderly, defective vulgarity in the next (Urciuoli Reference Urciuoli1996; Hill Reference Hill1998; Lo & Kim Reference Lo and Chi Kim2012; Flores & Rosa Reference Flores and Rosa2015).

Second, hybridity is never a settled fact—objectively decodable by a language expert—but an ideological product of interpretation (Hill & Hill Reference Hill and Hill1986; Pennycook Reference Pennycook2003) that is shaped by local ideologies and linguistic markets (Park & Wee Reference Park and Wee2008). Community members may largely share ideologies that define certain forms as ‘accented’, ‘mixed’, or simply ‘wrong’, but consensus is not always guaranteed, and language heard as remarkably hybrid by one listener may be heard as plainly pure by another. Importantly, through acts of recognizing certain objects as hybrid, whether in their celebration or condemnation, speakers and listeners necessarily presuppose that certain other objects are pure (Hill & Hill Reference Hill and Hill1986, Latour Reference Latour1993), despite the common hope that hybridity might challenge ideological boundaries and essentializing discourses (Bhabha Reference Bhabha1994). Treatments of hybridity as new, spectacular, and complex—needing to be segmented, labeled, and explained—may merely reflect ideologies that are distinctly modern (Latour Reference Latour1993), rather than the emergence of fundamentally new linguistic realities (Woolard Reference Woolard and Duranti2004).

Third, recognitions of hybridity are rarely ends in themselves but part and parcel of processes of culture and identity—both big and small—whether claiming legitimacy, building solidarity, establishing authenticity (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz, Hall and Duranti2004), or drawing community boundaries. A remaining issue then is not only how hybrid language comes to be recognized and assigned value but also how such evaluative recognitions enter broader cultural processes. How do linguistic forms, such as Korean names heard as pronounced with an American accent, become endowed with particular indexical values in K-pop discourses in the course of cultural projects? How do these evaluations of hybridity regiment the future possibilities of K-pop language, particularly in transnational spaces where linguistic values seem relatively indeterminate?

While language ideologies can circulate across a community in a number of ways, the focus of the present analysis is the role of metalanguage, or talk that explicitly reifies language and assigns it cultural value. Rather than assuming metalanguage to be transparent windows into language ideologies—that is, as expressions of speaker or community beliefs—I treat such discourses as forms of social action. Specifically, I understand moments of metalanguage as part and parcel of interactional stances that speakers take, located in sequential relation to other stances (Du Bois Reference DuBois and Englebretson2007) while also entering longer pathways of discourse (Wortham & Reyes Reference Wortham and Reyes2015). Metalanguage—how it manifests, how it becomes repeated, how it becomes contested, how it shapes future language practice, and how it regiments ideologies—is best understood as social action that lies in relation to other kinds of action. Social media discourses in particular, documented by participants themselves as visible and audible traces, may provide particularly useful sites for examining such interactional and ideological processes (Bonilla & Rosa Reference Bonilla and Rosa2015).

K-pop reaction videos on YouTube

My analysis focuses on discourse that emerged within and in response to a series of YouTube reaction videos uploaded by Cortney and Jasmine, two K-pop fans in their early twenties. These self-described best friends, residing in the United States, had been regularly producing videos under the username 2MinJinkJongKey for nearly three years, and despite investing minimally in the production of their videos—filmed with ostensibly no scripting, with a personal computer, from their home in Georgia—they had achieved some degree of transnational celebrity. Their channel had 77,871 subscribers as of February 19, 2015 and their 456 videos had 20,066,380 total views.Footnote 1

The discourse I analyze was shaped in part by the specific new media genre in which Cortney and Jasmine participated, namely the reaction video, a meta-video that documents in real-time individuals watching another video usually for the first time. In the case of the ‘K-pop MV reaction videos’ discussed here, the most visually salient objects on the screen were Cortney and Jasmine, whose affective stances were documented, whether shock, amusement, or excitement. But no less important was the viewed video—in this case a K-pop music video (MV)—usually visible as a small overlay at the bottom of the screen. While baffling for some, the YouTube reaction video genre has grown in prominence.

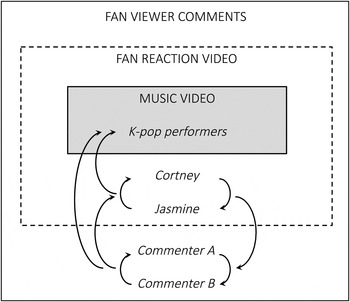

When embedded in the YouTube space, K-pop reaction videos produce a layered participant structure consisting of three nested texts (cf. Wortham Reference Wortham2003): (i) a K-pop music video, created by South Korean entertainment companies and K-pop performers, (ii) a reaction video, produced by K-pop fans, and (iii) the YouTube comments space, where other K-pop fans post comments, visible as a continuous list below the video. Not only do participants interact within each text—that is, interactions between performers, between reaction video creators, and between viewing fans—but participants directly address others across textual boundaries, such as when viewers pose questions of video creators, when video creators respond to these questions, and when both viewers and video creators express their adoration for K-pop performers in the music video (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Participant structure of K-pop fan reaction videos.

The salient ‘cross play’ (Goffman Reference Goffman1981) between participants located in different textual frames may be precisely what permits their productive ‘mediatization’ (Agha Reference Agha2011), as both music videos and reaction videos are commoditized by their creators for broad circulation across consumer audiences. This participant structure suggests that mediatized forms do not move linearly across speech chains, propelled between speakers and hearers (e.g. Agha Reference Agha2007). Rather, pathways are necessarily shaped nonlinearly, as participants continuously comment on and recontextualize prior events, which in turn precontextualize and shape future events (Ochs Reference Ochs, Duranti and Goodwin1992). In this sense, an understanding of mediatizing processes benefits from an interactional approach that attends to how linguistic significance is negotiated in temporally nonlinear ways.

The mediatization of K-pop fans’ reaction videos has broader cultural implications. First, they provide public evidence of the desirability of K-pop performers. In the videos examined here, Cortney and Jasmine frequently uttered dramatic interjections and sexualizing praise, and the vast majority of viewer comments included similar confessions of adoration. The collective visibility of these evaluative comments, scrollable across numerous pages, transforms individual opinions into confirmed facts. Second, these reaction videos produce evidence of K-pop's global consumption. Typically posted by non-Korean fans racialized as ‘black’, ‘white’, or ‘brown’, these videos serve as verification of K-pop's transnational and transracial appeal. In the present case, many viewer comments presupposed Cortney and Jasmine's blackness, based on racial ideologies that associated their language, skin, and hair with African Americans. Third, K-pop reaction videos allow viewers to experience music videos in virtual synchronicity, as they watch them in the apparent company of others. Shared experiences of co-consumption permit K-pop fans to maintain affective connections.

My data are limited to videos featuring Cortney and Jasmine's reactions to songs performed by two highly celebrated male K-pop groups. The first group, Big Bang, working under the label Y.G. Entertainment, had won various awards in Asia and Europe since debuting in 2006. Its five members were typically referred to by their stage names (G-Dragon/G.D., Taeyang, T.O.P., Daesung, and Seungri) and very rarely by their personal names (Kwon Jiyong, Dong Youngbae, Choi Seunghyun, Kang Daesung, and Lee Seunghyun). The second group, EXO, working under the label S.M. Entertainment since 2011, had not only won awards in South Korea and China but had become ranked seventh on the US Billboard's ‘World Albums List’ in 2014. As a large group, EXO sometimes performed as two subgroups of six members: EXO-K, who performed in Korean, included Suho, Baekhyun, Chanyeol, D.O., Kai, and Sehun (Kim Junmyeon, Byun Baekhyun, Park Chanyeol, Do Kyungsoo, Kim Jongin, and Oh Sehun), and EXO-M,Footnote 2 who sang in Mandarin, included Kris, Xiumin, Luhan, Lay, Chen, and Tao (Li Jiaheng, Kim Minseok, Lu Han, Zhang Yixing, Kim Jongdae, and Huang Zitao). Both Big Bang and EXO, like other K-pop groups, performed a range of genres, although the former focused primarily on hip hop and both performed R&B and dance music.

Among over 400 videos that these women had posted by January 23, 2015, I analyzed a subset of eleven, as well as eighty-four of 4,877 viewer comments, selected in the interest of capturing interdiscursive links across the videos and comments, namely metalinguistic discussions about how K-pop names should be pronounced. I limited my analysis primarily to reaction videos with view counts of over 100,000, since comments elicited by these widely viewed videos were potentially significant in the regimentation of fans’ language ideologies.Footnote 3 Table 1 summarizes the eleven videos.Footnote 4 Video 1, despite its view count being under 100,000, was included because it contained the very first utterance of Taeyang, the K-pop name central to the current discussion.

Table 1. K-pop reaction videos by 2MinJinkJongKey.

Hybridizations and their contextualizing ideologies

My analysis illustrates how metalinguistic stances expressed by K-pop fans regimented language ideologies and practices in the K-pop fan community. More specifically, I examine how linguistic forms came to be recognized as hybrid, what cultural value was assigned to such forms, and how language came to be heard and performed as a result. A crucial assumption is that it was not the objective shape of language that guaranteed its status as hybrid but acts of contextualization that treated it as such. In addition, I consider how acts of hybridization were necessarily dialogic, as they emerged sequentially in discourse (Du Bois Reference DuBois and Englebretson2007). In some cases, they reaffirmed a prior contextualization of hybridity, yet in other cases, they recontextualized and reinterpreted a form once contextualized as pure. I represent this process below: a linguistic form x, contextualized in some prior moment of discourse (as unspecified Q) becomes contextualized as belonging to hybrid H, recognizably located between languages A and B.

-

(1) Hybridization

As suggested here, hybridization, as an act of interpretation, is discursively contingent rather than inevitable, and certain forms contextualized as hybrid by some listeners may be contextualizable as pure by others.

One of the hybridized forms I attend to is the name Taeyang, uttered by Cortney in Video 1 and subsequently uttered in Videos 2, 3, and 4 by both Cortney and Jasmine. Cortney's utterance in Video 1 (line 1) precedes Cortney and Jasmine's acts of praise (lines 2, 3) and critique (lines 4, 5).

-

(2) The initial utterance of Taeyang in Video 1

1 Cortney: Taeyang [tʰe:ɪjε:ŋ]

2 Jasmine: ((Click, teeth-sucking))

3 Cortney: I mean he's always fine.

4 Jasmine: It's pretty much the same though.

5 Cortney: But he's just like getting on my nerves with that Mohawk.

Importantly, in this initial utterance, Cortney provides no explicit contextualization of this utterance as either hybrid or pure. Her fluid incorporation of the name Taeyang into the ongoing discourse, without any special framing or hesitation, seems to suggest at least its unmarked linguistic status, despite being a Korean name in an otherwise English conversation.

Yet as I discuss in the remainder of this analysis, fans’ subsequent comments identified Cortney's [tʰeɪ:jε:ŋ] pronunciation as linguistically marked. Specifically, the long mid vowel of the second syllable was heard as diverging from the short low vowel [a] that Koreans typically used when uttering this name, including Taeyang himself. Indeed, Cortney's vowel abided by two rules hearable as distinctively American. First, American English speakers often pronounce syllable rimes orthographically represented as ang (as in bang) with either a low-mid [æ] vowel (as in bat) or a mid [ε] vowel (as in bet). (The latter variant reflects a dialect-specific convention of raising /æ/ to [ε] before nasals.) Second, unlike Korean vowels, English vowels often undergo lengthening before voiced consonants like /ŋ/. As such, while [jε:ŋ] bears no inherently hybrid property, some listeners were apt to hear this syllable as shaped by two languages at once (Woolard Reference Woolard1998).

Prescription as strict absolutism

Viewers’ acts of identifying Cortney's [tʰeɪ:jε:ŋ] as hybrid were typically presented as acts of evaluation that reflected specific ideological orientations toward hybrid language. In most cases, these acts were embedded in critiques, or acts of prescription that contextualized hybridity as less desirable than purity, indicated by the asterisk below.

-

(3) Prescription: Hybridization with devaluation

In K-pop fan discourses, such prescriptive hybridizing acts were usually implicit. For example, two fans explained how ‘Taeyang is pronounced’—that is, how it should be pronounced. Their explanation presupposed Cortney's mispronunciation of the name.

Table 2. Viewer comments as acts of prescription (for Video 1).

In many other cases, fans explicitly characterized Cortney's pronunciation as ‘wrong’ or not ‘right’.

Table 3. Viewer comments as acts of prescription (subset of sixty-three comments for eleven videos).

These comments invoked a notion of ‘correctness’ or ‘rightness’, or the degree to which a form abided by the rules of a desirable target language (right or correct) as opposed to not abiding by these rules (wrong or incorrect). While fans did not explicitly label ‘incorrect’ forms as ‘hybrid’, I suggest that these assessments of incorrectness simultaneously implied the form's hybridity, or its abidance by the rules of more than one language (hybrid) as opposed to the rules of only one language (pure). Specifically, Cortney and Jasmine's failure to reach their presumed language target, manifesting as an ‘incorrect’ form, was assumed to result from their lack of access to the target language (Korean) and thus their adherence to the rules of their native language (English), as alluded to by some viewers: ‘These beautiful ladies are American and therefore pronounce idol names the way letters sound in American English’ (comment 3964); ‘a lot of americans say Taeyang the way you do’ (comment 3002); ‘their not korean how do you expect them to say it perfectly’ (comment 2706).Footnote 6

Fans’ prescriptive acts, which constituted sixty-three of the eighty-four comments, reflected an overwhelmingly dominant ideology of strict absolutism, according to which ideal K-pop fans—those who demonstrated their respect for and solidarity with K-pop—ideally pronounced Korean names with Korean phonology, and English names with English phonology. That is, despite the acceptance of the community's multilingualism, language practices were largely idealized as orienting to one language at a time. Fans’ absolutist stances paralleled the assumptions of performers when pronouncing their own names. Performers with stage names recognizably deriving from English names or alphabetic letters (G.D., T.O.P., D.O., Kris) typically pronounced their names with vowel, stress, and phonotactic patterns of American English ([ˈdʒiˈdi:], [tʰɑp], [ˈdiˈoʷ:], [kʰɹɪs]), avoiding phones hearable as Korean ([ˈdʒʰiˈdi], [tʰap], [dʰio], [kʰʊrisʊ]) or Mandarin [kʰəlisəz]), despite primarily using Korean and Chinese pronunciations when uttering their Korean or Chinese names. This ideology also positioned Cortney and Jasmine, presumed to be native speakers of English, as unquestionably legitimate users of correct English: they were never corrected when uttering ‘English’ names (Kris, G.D., T.O.P., D.O., V.I.), yet frequently corrected when they uttered non-English ones: Suho (fourteen corrections), Taeyang (thirteen corrections), Sehun (ten corrections), Youngbae (four corrections), Xiumin (three corrections), Chanyeol (two corrections), Baekhyun (two corrections), and Daesung (one correction).

Yet beyond reflecting an absolutist ideology, prescriptive acts were moments of social action that positioned individuals within the local community. They showcased critics’ expertise and loyalty, differentiating K-pop devotees from mere dabblers. Additionally, fans’ critiques, while sometimes framed as insults, were more commonly acts of alignment that guided Cortney and Jasmine toward pure language. In many cases, acts of linguistic instruction were sandwiched between acts of solidarity, including praise (comments 64, 4440, 5045), well-wishing (comment 4440), and mitigating forms of negative politeness (comment 5045).

Table 4. Viewer comments as acts of instruction and solidarity (subset of twenty-two comments).

In other words, these acts of prescription projected a future trajectory for Cortney and Jasmine, imagined as eventually aligning with K-pop purist norms: they invited an idealized pathway towards purification through the replacement of the problematic (*) hybrid form x with the ideal (+) pure form y.

-

(4) Imagined purification

In sum, prescriptive acts of correction reflected a centripetal ideology of strict absolutism, locating devoted experts at its center and shepherding less expert fans towards an idealized purity.

Toleration as conditional absolutism

Prescriptive acts of correction, whether framed as insult or instruction, called into question Cortney and Jasmine's status as exemplary fans. As such, these two fans typically responded to strict absolutist critiques by demanding tolerance for their linguistic imperfections.

Table 5. Cortney and Jasmine's comments as acts of toleration (for Videos 2 and 3).

It is important to observe that despite the framing of these responses as rejecting prescriptive acts (‘its not that serious’, comment 1384), Cortney and Jasmine maintained the absolutist assumption that they had mispronounced K-pop names (‘Sorry we said his name wrong’, comment 165). This ideology of conditional absolutism recognized that linguistic habits of the past constrain subsequent practices (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Thompson1991), such that even devoted fans inevitably produce ‘wrong’ language. In calls for toleration—a form previously characterized as hybrid (H) retains its undesirable status (*) but becomes temporarily bracketed as an acceptable exception ([ ]).

-

(5) Toleration: Hybridization with conditional evaluation

Eight of the eighty-four comments aligned with Cortney and Jasmine's conditional absolutism, agreeing that mispronunciations are common (comment 396). In fact, as one commenter noted, K-pop performers would reject strict absolutist standards given that they themselves ‘still struggle with some english words’ (comment 1390). Conditional absolutists recognized that while names had been ‘mispronounced’, ‘it [didn't] really matter’ (comment 2869).

Table 6. Viewer comments as acts of toleration (subset of eight comments for Videos 2, 3, and 4).

Like Cortney and Jasmine, these eight fans maintained an inclusive transnational spirit while still maintaining an ideology of absolutism.

Stylization as transgressive hybridity

Another way in which K-pop hybridities could escape critique was by their reflexive framing as intentionally transgressive. For example, Cortney and Jasmine sometimes engaged in unproblematized forms of salient hybridization, such as when Taeyang dramatically appears in Video 2, and Cortney utters Taeyay [tʰeɪ:.jei:] as an act of recognition and celebration (line 3).

-

(6) Taeyang utterance in Video 2

1 Jasmine: Oh my god

2 Cortney: THAT IS WHERE WE WERE.

3 Yay Taeyay [tʰeɪ:.jei:]

4 Jasmine: Oh my god

Cortney's poetic partial reduplication was arguably neither wholly Korean nor wholly English, as it creatively combined the first syllable of Taeyang with the celebratory English interjection yay. The acceptable status of this particular hybridity, never critiqued by viewers, seemed in part to depend on its successful contextualization as an artful stylization—as a transgressive hybridization that legitimated an in-between status (Jaffe Reference Jaffe2000)—rather than as an unintentional error that laid bare Cortney's linguistic incompetence.

Assumptions about language ability and awareness contributed to interpretations more generally in the K-pop community; beliefs about which linguistic elements speakers could perform if they so desired, elements they intended to perform, and elements they did perform, underlay the distinction between hybridities valued as intentional transgressions and those vulnerable to being heard as unintentional errors. These assumptions manifested in an important linguistic asymmetry among K-pop performers, typically assumed to be fluent in Korean, if not native speakers. On the one hand, performers with Korean stage names sometimes used English flourishes; for instance, Taeyang and Seungri often pronounced their own Korean stage names as /tʰe:ɪja:ŋ/ and /sʊ:ŋni/, containing recognizable transgressive splashes of English sounds: prenasal vowel lengthening, upgliding, and de-aspirated /s/. Yet G.D. and T.O.P avoided uttering their English names with Korean sounds, audible as unintentional ‘remnants’ of their native language. Likewise, unless Cortney and Jasmine's hybrid flourishes were unambiguously contextualized as purposefully poetic language play, as in their stylized Taeyay in (6) above, English sounds on Korean names risked being heard as undesirable remnants of Cortney and Jasmine's native English.Footnote 7

While transgressive hybridities may appear to challenge absolutist norms of language, their effectiveness as a lasting challenge to K-pop absolutism is questionable. Specifically, these stylized forms, felicitously performable by only certain speakers, depend on a marked frame (Goffman Reference Goffman1974), deriving their value as playful or artful precisely because of their ‘bracketed’ ephemerality. As represented below, stylizations may be celebrated, but they entail prior and future contextualizations of normative purity.

-

(7) Stylization: Hybridization as temporary celebration

It should be noted that stylized hybridities by K-pop performers sometimes managed to enter relatively enduring pathways of conventionalized practice, such as the regular stylization of Korean monophthongs [o] and [e] as English-sounding diphthongs [ow] and [eɪ]. However, I suggest that even these conventionalized cases failed to challenge absolutist assumptions. Importantly, these stylized diphthongs were valued specifically because of their presumed momentariness, deviating in their marked hybridity from an unmarked version of monophthongal, pure Korean. Even here, an imagined linguistic purity served as the necessary backdrop for these transgressive stylizations.

Authorization as relativism and pluralism

A final discursive possibility emerged among a small subset of six fans who challenged the absolutist assumptions described above. These fans adopted a relativist perspective, recognizing that different language systems have different norms, as well as a pluralist perspective, acknowledging that multiple forms, both pure and hybrid, can be acceptable. By treating correctness as relative and plural rather than absolute and singular, this perspective accommodated the disparate linguistic histories of K-pop fans.

Through this process of authorizing (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz, Hall and Duranti2004) hybrid forms, K-pop fans recuperated the value of hybrid forms (+) by linking them to the legitimate multilingual histories of K-pop fans.

-

(8) Authorization via relativism and pluralism

This relativist view emerged when defending Cortney and Jasmine. In one case, a commenter questioned the prescriptive assumption that only one correct form existed: ‘theres no correct way or incorrect way. in korea they write the member's names in korean unless its D.O. even Kris is in korean. Xiumin would be in korean as well. but its not korean they are reading, its english letters so the accurate way to pronounce it with the english letters’ (comment 3829). According to this fan, the same name could be acceptably pronounced in different ways, reflecting how words were transliterated in different writing systems, with phonology and orthography mediating one another (Jaffe Reference Jaffe2013).

Another commenter defended Cortney and Jasmine, noting that pronunciations were understandably dependent on the respective ‘letters’ of ‘American English’, the language considered native to these women: ‘These beautiful ladies are American and therefore pronounce idol names the way letters sound in American English. It's the same way Koreans call Tiffany TIPPANY and my French speaking grandmother pronounces my name Nicole like Knee-Coll’ (comment 3964). This commenter not only analogized Cortney and Jasmine's pronunciation with the practices of both French and Korean speakers of English but also highlighted the realities of transnational, multilingual encounters that produce newly acceptable language norms. Similarly, others viewers commented, ‘if I was you I would stick with Taeyang, cause a lot of americans say Taeyang the way you do’ (comment 3002) and ‘I love how you say Taeyang's name’ (comment 302). These fans regarded an English pronunciation of a Korean name—a hybrid form—as acceptable as any other.

Pathway to purification: Avoidance and replacement

The preceding analysis has shown that prescriptive critiques of Cortney and Jasmine's language reflected ideological stances that were more typically absolutist than relativist and pluralist. I turn now to the consequences of these stances along a broader trajectory, namely, how evaluations of Cortney and Jasmine's language nudged it towards its purification. Specifically, I argue that it was a result of the overarching linguistic absolutism of K-pop that Cortney and Jasmine engaged in linguistic avoidance, erasing an undesirable hybrid form x, and eventually replacing it with a form y contextualized as pure.

-

(9) Avoidance and replacement

Despite their calls for toleration, as described above, Cortney and Jasmine responded to prescriptive critiques by avoiding the name Taeyang, opting instead for the performer's Korean personal name Youngbae. In (10) below, after Cortney utters ‘Taeyang’ (line 6), Jasmine introduces Taeyang's personal name ‘Dong Youngbae’ (line 9). Without skipping a beat, Cortney aligns with this newly introduced name through its repetition (line 10). The unmarked shift suggests lexical interchangeability between these names despite the rare use of Dong Youngbae among K-pop fans generally.

-

(10) Initial switch to Youngbae in Video 2

1 Cortney: I love?

2 Jasmine: love that?

3 Cortney: the song.

4 {Shit} ((whispered))

5 The reason that we paused it?

6 when Taeyang [tʰe:ɪjε:ŋ]

7 Jasmine: m::

8 Cortney: Dropped down.

9 Jasmine: Dong Youngbae. [dʌŋjʌŋbe:ɪ]

10 Cortney: {Dong Youngbae} ((breathy)) [dʰɑŋjʌŋbʰe:ɪ]

11 Jasmine: When he popped up on the screen

12 just ((sigh))

In Video 3, responding to a fan's inquiry (‘why do you keep calling taeyang youngbae??’, comment 1558), they explain their decision to use the name Youngbae. As they admit their inability to pronounce Taeyang ‘right’, they imply their ability to pronounce Youngbae correctly.

-

(11) Metalinguistic explanation of the switch to Youngbae in Video 3

1 Cortney: Even though@ I lo:ve me

2 some Taeyang

3 Sorry.

4 Jasmine: Taeyang

5 Youngbae

6 Cortney: Sorry.

7 Youngbae

8 Jasmine: However you say it

9 Cortney: I'm sorry.

10 we can't-

11 I'm sorry

12 we're not saying the name right

13 so we're just gonna say Youngbae

14 Jasmine: We do apologize

15 Cortney: We're just gonna try to @say Youngbae

16 to make it

17 to make it universal@

18 Jasmine: Yeah.

Indeed, in contrast to Cortney and Jasmine's utterances of Taeyang, corrected thirteen times, their utterances of Youngbae in Videos 3, 4, 5, and 6 were corrected only once (‘But you're also saying Youngbae wrong’, comment 3002), suggesting that viewers largely accepted Cortney and Jasmine's contextualization of Youngbae as pronounced ‘correctly’.Footnote 8 The initial avoidance of the name Taeyang in Video 2, initiated a pathway of social action across subsequent videos. After toggling between the two names in Videos 3 and 4, they eventually completed the shift to Youngbae by Videos 5 and 6, posted over a year later. The following table displays the number of times Taeyang and Youngbae were uttered in each of the six videos featuring Taeyang.

Table 7. Cortney and Jasmine's utterances of Taeyang and Youngbae.

In fact, Cortney and Jasmine generally avoided names that risked criticism as ‘incorrect’. For example, they never referred to the performer Seungri by his common stage name, using instead his lesser-known English stage name V.I., which fans never critiqued as mispronounced. In another case, Cortney and Jasmine avoided the Chinese name Xiumin in Video 9, referring to the performer instead as ‘one that’s name starts with an X’ and contextualizing their avoidance with playful self-deprecation in an accompanying subtitle: ‘Xiumin sorry can't pronounce that lol.’ Responding to this video, twenty viewers offered the ‘correct’ pronunciation (‘Xiumin is pronounced like shu-min xD it's Chinese so the Xiu is like saying shhh’, comment 4077), and so dutifully following this guidance, Cortney and Jasmine later approximated Xiumin's name as /ʃumɪn/ in Videos 10 and 11. Their pronunciation, never openly critiqued, became contextualized in this space as a sufficiently correct enunciation of Chinese.

Conclusion

Linguistic hybridities are salient in K-pop, as a genre that orients both ‘locally’ and ‘globally’ and that circulates as a highly mediatized commodity across national boundaries. Yet whether tokens of K-pop language can be heard as hybrid, as well as whether hybridities are desirable, is the outcome of contextualizing metapragmatic actions. Among K-pop fans, a single linguistic form might be framed as an undesirable hybrid error in one moment, and then in the next, recontextualized as a tolerable accent or as a legitimate hybrid alternative. Likewise, this same form might have entered other pathways, contextualized as a purposefully transgressive stylization or even as a pure rendition of Korean, English, or Chinese.

Among the YouTube K-pop fans discussed above, naming practices in particular served as important forms of social action (Rymes Reference Rymes1996; Reyes Reference Reyes2013), positioning social actors—those named and those who named—within a landscape of relevant cultural distinctions. The way K-pop fans ‘dropped a name’—how it was pronounced—as well as acts that policed and defended these pronunciations, drew distinctions between devoted fans and mere novices. Additionally, in a context of widely disparate competences and language ideologies, naming practices constituted a key cultural mechanism for regimenting fans’ language practices.

Crucially, despite the prevalence of hybridities in K-pop, I have shown that fan pronunciations were overwhelmingly evaluated according to the absolutist belief that pure forms were preferable to hybrid ones. The outcome was the nudging of two fans’ hybridities along pathways toward their purification. Hybridities may proliferate in K-pop, sometimes even fetishized for their novelty, but absolutist ideals of linguistic purity are hardly open to being dismantled.

APPENDIX: TRANSCRIPTION CONVENTIONS

- ?

-

rising intonation

- .

-

falling intonation

- @

-

laughter

- WORD

-

increased volume

- word

-

emphasis (pitch, amplitude, or length)

- WOR-

-

break in the word

- ((details))

-

relevant transcription comments

- {WORD}

-

text described by comments