The jaguar Panthera onca, the largest Neotropical felid, is currently limited to half of its original range and its populations are threatened by habitat loss, poaching and declining prey populations (Swank & Teer, Reference Swank and Teer1989; Sanderson et al., Reference Sanderson, Redford, Chetkiewicz, Medellin, Rabinowitz, Robinson and Taber2002; Quigley et al., Reference Quigley, Foster, Petracca, Payan, Salom and Harmsen2017). In the Atlantic Forest, one of the most threatened tropical forests (Myers et al., Reference Myers, Mittermeier, Mittermeier, da Fonseca and Kent2000), the jaguar has already lost 85% of its habitat, and its population is estimated to be < 300 reproducing individuals distributed in small subpopulations and restricted mainly to the largest forest fragments (> 1,000 km2) (Paviolo et al., Reference Paviolo, De Angelo, Ferraz, Morato, Martinez Pardo and Srbek-Araujo2016). However, jaguars were previously believed to be extinct in the large fragments of the coastal forest of the Serra do Mar in southern Brazil (Paviolo et al., Reference Paviolo, De Angelo, Ferraz, Morato, Martinez Pardo and Srbek-Araujo2016).

The most recent documented records of the species in this region were faecal records from 1997 (Leite & Galvão, Reference Leite, Galvão, Medellín, Equihua, Chetkiewicz, Crawshaw, Rabinowitz and Redford2002) and track and vocalization records from 2006 (Mazzolli & Hammer, Reference Mazzolli and Hammer2008) in the state of Paraná. As these forests lie in one of the largest continuous remnants of the Atlantic Forest (c. 6,500 km2), connecting preserved forest areas across a coastal mountain range (Fig. 1), and are difficult to access, the absence of jaguar records could be a result of the lack of surveys rather than necessarily reflecting the absence of the species. Over 8 years we therefore surveyed a large forest fragment in the Serra do Mar, culminating in the confirmation of the presence of the species in the region and in unique photographic records. We discuss the implications of these findings for jaguar conservation in the Atlantic Forest.

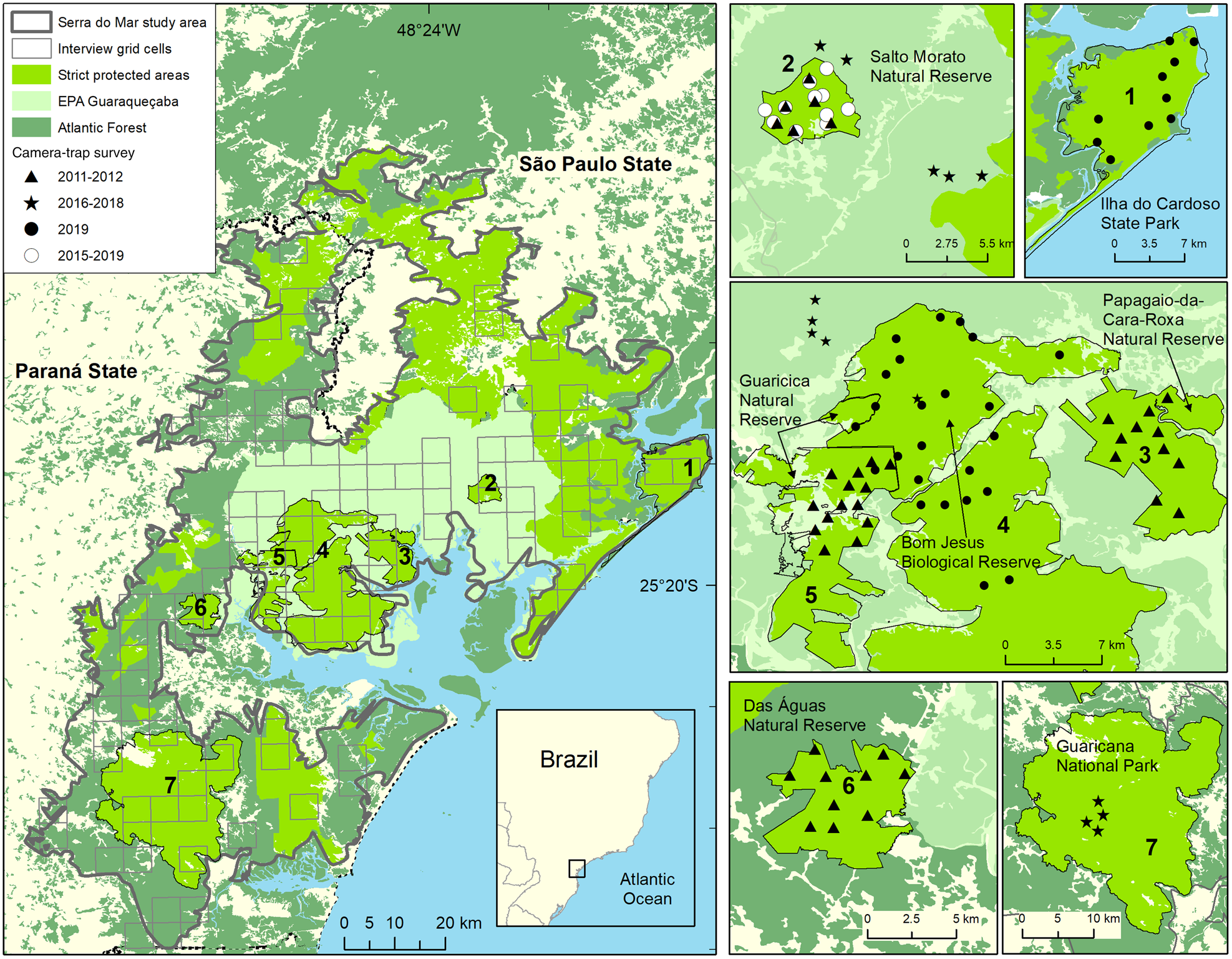

Fig. 1 Serra do Mar study area, with the grid cells where we conducted interviews and the locations of the camera-trap stations in seven protected areas. EPA, Environmental Protected Area.

The coastal forest of Serra do Mar in Paraná State is mostly mountainous and ranges from the coast to the highest peak at 1,877 m (Maack, Reference Maack2012). The region comprises a mosaic of protected areas ranging from restrictive (e.g. Reserves, Parks, ecological stations) to less restrictive protected areas (e.g. Environmental Protected Areas), and small cities and rural villages located mainly along the coastal plain and roads, where a historical process of deforestation and forest degradation took place.

During 2011–2012 we used 41 camera-trap stations to survey four private nature reserves totalling 220 km2 (Fig. 1; Fusco-Costa & Ingberman, Reference Fusco-Costa and Ingberman2013; Fusco-Costa, Reference Fusco-Costa2014). In 3,741 trap-days we recorded 23 species of mammals > 1 kg. The only large mammal expected in this region that we did not record was the jaguar. However, local inhabitants reported to us that the jaguar was present in a mountainous area that was difficult to access.

To collect information on the presence of jaguars and other mammals in the entire Serra do Mar region in Paraná and southern São Paulo states (c. 6,500 km2), we carried out interview surveys during 2012–2017. We divided the area into 5 × 5 km grid cells and randomly selected 102 for surveys (Fig. 1, Supplementary Material 1). In 249 interviews we received at least one report of the potential presence of the jaguar in each of 24 grid cells (23.5% of the total surveyed; Fig. 2b).

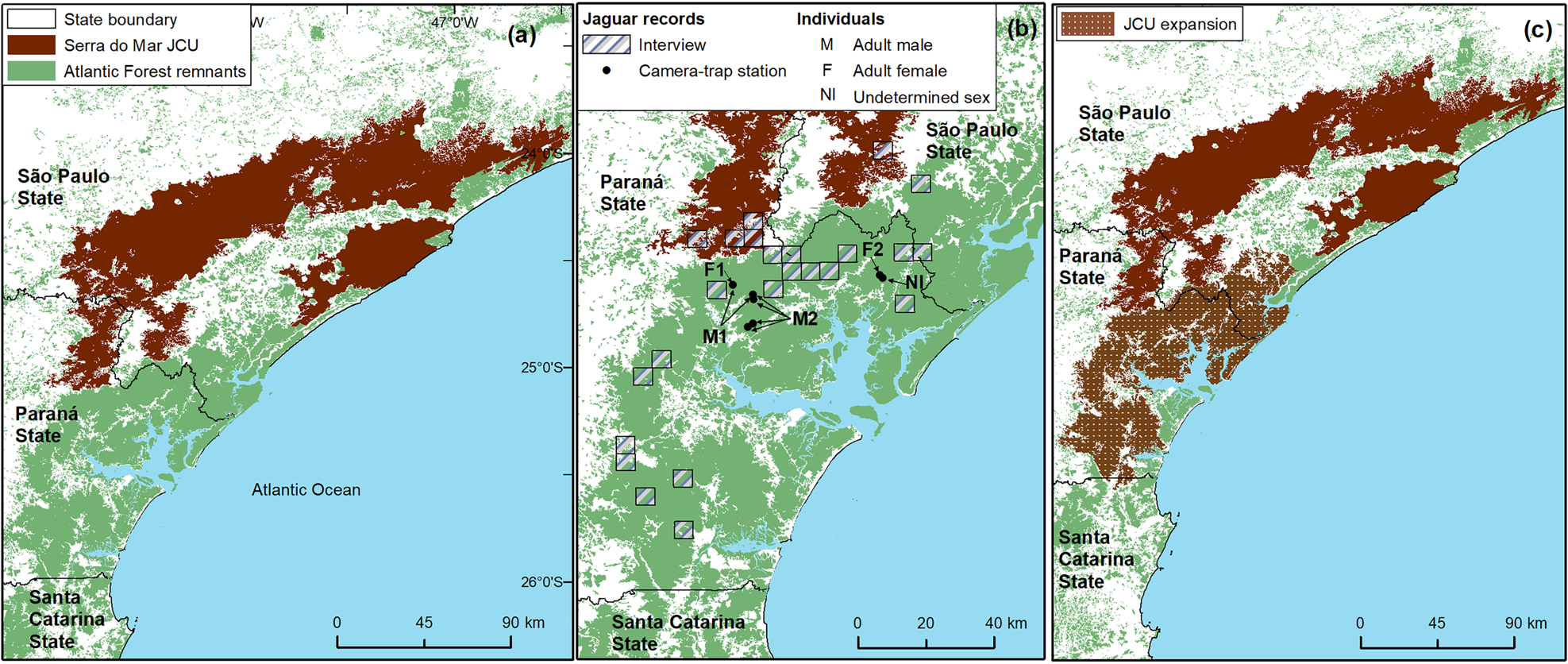

Fig. 2 (a) The jaguar conservation unit (JCU) of the Serra do Mar region (adapted from Paviolo et al., Reference Paviolo, De Angelo, Ferraz, Morato, Martinez Pardo and Srbek-Araujo2016, with a different forest shape file; Supplementary Material 2). (b) New jaguar Panthera onca records in the Serra do Mar (five individual jaguars: two males, two females and one of undetermined sex). (c) Our proposed southern expansion of the Serra do Mar jaguar conservation unit.

During 2016–2018 we established 14 camera-trap stations (Fig. 1) for a total of 705 trap-days in three protected areas (Bom Jesus Biological Reserve, Guaricana National Park and Guaraqueçaba Environmental Protected Area) where informants had reported the occurrence of jaguars. In July 2018, we obtained two independent jaguar records (on different days) at one camera-trap station in a remote and mountainous area of the Guaraqueçaba Environmental Protected Area (Fig. 1). The first record was an adult male, and the second the same adult male together with a female, exhibiting courtship behaviour (Plate 1).

Plate 1 The first photographic record of jaguars Panthera onca in the Serra do Mar region of the Atlantic Forest in Paraná State, Brazil (Fig. 1), showing two adult individuals, one male and one female, exhibiting courtship behaviour.

In 2019 we established 32 camera-trap stations in Bom Jesus Biological Reserve and Ilha do Cardoso State Park (Fig. 1). In a total of 1,130 trap-days we obtained four records of jaguars: a previously unrecorded adult male and the male recorded in 2018, from four camera-trap stations in the northern mountainous portion of the Reserve.

During 2015–2019, the management of Salto Morato Private Nature Reserve carried out an annual mammal monitoring programme using 4–11 camera-trap stations (Fig. 1) for a total of 8,633 trap-days. In September 2018 they provided us with an image of the first record of a jaguar in the Reserve, which we identified as an additional individual of undetermined sex, and in 2019 they recorded a previously unrecorded female jaguar in the Reserve.

Overall during 2011–2019, 98 camera-trap stations operated for a total of 14,239 trap-days, with 76% in lowland forests at 0–200 m and 24% in montane forests at 200–700 m. We obtained eight records of five individual jaguars (two males, two females and one of undetermined sex) at seven camera-trap stations (Fig. 2b) in montane forests. The presence of females and nearby males indicates the use of this area by jaguars is not occasional and that males are monitoring the area in search of females. The low number of records relative to the high survey effort suggests a low abundance of jaguars, presumably taking refuge in these difficult-to-access montane areas as a result of historical and current hunting pressures in the region (Leite & Galvão, Reference Leite, Galvão, Medellín, Equihua, Chetkiewicz, Crawshaw, Rabinowitz and Redford2002; Mazzolli, Reference Mazzolli2009).

Our results have implications for jaguar conservation in the Atlantic Forest, because they modify the status of the area from unoccupied to occupied by the jaguar (Fig. 2a, c). Using an adaptation of previous methodology (Paviolo et al., Reference Paviolo, De Angelo, Ferraz, Morato, Martinez Pardo and Srbek-Araujo2016), the new jaguar records from camera traps result in an increase in the area of jaguar occupancy and area of jaguar potential occupancy (Supplementary Material 2) of 3,434 km2 and 2,281 km2, respectively. This is a 9% increase in the area of jaguar occupancy in the Atlantic Forest and a 46.9% increase of jaguar occupancy in the Serra do Mar compared to the previously estimated areas of 37,825 km2 and 7,315 km2 (Paviolo et al., Reference Paviolo, De Angelo, Ferraz, Morato, Martinez Pardo and Srbek-Araujo2016), respectively. Inclusion of the information from interviews increases the area of occupancy by an additional 1,208 km2. The presence of males and females in the fragment, including evidence that individuals are breeding, makes it a priority area for jaguar conservation (i.e. a jaguar conservation unit; Supplementary Material 2). As this area is contiguous with the existing Serra do Mar jaguar conservation unit (Paviolo et al., Reference Paviolo, De Angelo, Ferraz, Morato, Martinez Pardo and Srbek-Araujo2016), we propose a southwards expansion of this unit by 5,715 km2 (i.e. the areas of occupancy and potential occupancy; Supplementary Material 2), increasing the previously existing jaguar conservation unit of 13,547 km2 to 19,262 km2 and thus making it the largest priority area for jaguar conservation in the Atlantic Forest biome.

Our findings reinforce the importance of protected areas for jaguar conservation, including the need for investments to curb poaching and to monitor the jaguar population throughout this region. With large-scale monitoring we would be better able to understand the patterns and process of jaguar population expansion/retraction over time and identify any potential human–jaguar conflicts that lead to jaguar deaths because of retaliation (Palmeira & Barrella, Reference Palmeira and Barrella2007). Such data are crucial for the identification of corridors and source population areas that require protection, and for conflict mitigation and conservation planning.

This enlarged jaguar conservation unit could serve as a vital source of individuals for the coastal forests further south. Although jaguars seem to be extinct in Santa Catarina state to the south (Mazzolli, Reference Mazzolli2009), our interview data suggest that the forested regions of this state, which are contiguous with those of Paraná state (Fig. 2), could be classified as an area of potential jaguar occupancy (Supplementary Material 2). We recommend that surveys are extended to Santa Catarina state to determine whether the presumed extinction of jaguars there represents another case of a false absence.

Acknowledgements

We thank the institutions that supported this work (Fundação Florestal, Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade, Sociedade de Pesquisa da Vida Selvagem, Fundação Grupo Boticário, Instituto de Água e Terra do Paraná); all protected area staff; local residents who helped us access areas to install camera traps (the Lamberg family and Genivaldo); all interviewees; and Marion L.B. Silva, Samuel Duleba and Ginessa Lemos for sharing the data from Reserva Natural Salto Morato. We received financial support from Fundação Grupo Boticário, The Rufford Foundation, WWF-Brazil and ABN-AMRO Bank. RF-C received a postdoctoral fellowship from Programa Nacional de Pós-Doutorado da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior.

Author contributions

Study design and fieldwork: RF-C, BI, GSM; data analysis: RF-C, BI; writing: RF-C, BI, GSM, ELdAM-F.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.