Introduction

Since the nineteen-sixties, social policy scholars have sought to understand the ways in which the distribution and allocation of public services both reflects and shapes different forms of inequality. Thus, there has been longstanding concern about the sufficiency of services in relation to socio-economic inequality (Tudor Hart, Reference Tudor Hart1971; Le Grand and Winter, Reference Le Grand and Winter1986; Mercer and Watt, Reference Mercer and Watt2007), about discrimination based on ‘race’ (Lineberry, Reference Lineberry1977; Wacquant, Reference Wacquant and Mingione1996; Levine and Gershenson, Reference Levine and Gershenson2014) and about how the spatial patterning of inequality affects who gets what from public services (Powell and Boyne, Reference Powell and Boyne2001; Hastings, Reference Hastings2007; Feigenbaum and Hall, Reference Feigenbaum and Hall2015). In the UK, interest has grown over the last decade in how a range of inequalities may influence service provision, particularly since the Equality Act (2010) made it illegal for public services to discriminate directly or indirectly against people who share nine ‘protected characteristics’Footnote 1 (Hepple, Reference Hepple2011; King, Reference King2013).

These debates have been amplified by the decade of fiscal austerity (2010–2019) and the resultant drastic reductions in national government funding for a raft of public services, with most attention focused on the uneven impacts of cuts in provision, quality and eligibility. There is evidence on, for example, the disproportionate reductions of welfare services for disabled people (Dodd, Reference Dodd2016) and on cuts to services to support LGBT+ people (Matthews, Reference Matthews2020). There is growing body of evidence on the impacts of austerity on the public services experienced by poorer households and people living in poorer places (e.g. Fitzgerald and Lupton, Reference Fitzgerald and Lupton2015; Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Bailey, Bramley and Gannon2017). Finally, the strengthening focus on women’s experience of austere public services (e.g. Bassel and Emejulu, Reference Bassel and Emejulu2017; Gillibrand, Reference Gillibrand2020) is developing alongside recognition of a ‘gender data gap’ in this respect and, indeed, more broadly in how we understand society (Criado Perez, Reference Criado Perez2019).

This article seeks to contribute new empirical evidence specifically on socio-economic and gendered inequalities and whether these have increased with austerity cuts to services. It does so through a case study of the environmental services of a UK local authority: North Lanarkshire Council in west-central Scotland. We focus on whether austerity cuts to services have widened inequalities, particularly as cuts have reduced planned, programmed aspects of service provision and increased the reliance of services on citizens reporting problems – effectively a shift to ‘co-producing’ services with citizens (O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Offenhuber, Baldwin-Philippi, Sands and Gordon2017). Citizen requests, and the service response, for local environmental service interventions are examined using data covering the first nine years of austerity. In England, spending on these services reduced by over £900m between 2009 and 2016 (Gray and Barford, Reference Gray and Barford2018: 558). While the focus of much UK research has tended to be on the drastic funding cuts experienced by English local government, in Scotland cuts to service spending have also been significant – a reduction of 11.5 per cent between 2009 and 2016 – albeit about half the English rate (Gray and Barford, Reference Gray and Barford2018: 553). The article therefore contributes evidence on the potentially unequal effects of such ‘downloading’ of austerity by national governments onto the local state (Peck, Reference Peck2014).

The focus on neighbourhood environmental services – street cleaning, dumped refuse removal and responsive maintenance – might not seem an obvious subject for social policy. However, an increasing body of evidence points to broad psycho-social benefits of high-quality environments (e.g. Kearns et al., Reference Kearns, Whitley, Bond and Tannahill2012), and there is considerable evidence that perceived and more ‘objective’ measures of environmental quality are persistently lower in less-advantaged neighbourhoods (Keep Britain Tidy, 2015; Keep Scotland Beautiful, 2017). There is also some evidence that women are less likely to be satisfied with the condition of streets and pavements (Criado Perez, Reference Criado Perez2019: 34–35). For these reasons, local neighbourhood environmental and maintenance issues, particularly those that concern the social patterning of citizen reports of problems and the service response to these reports, are an important social justice and policy issue.

The next section of the article sets the context for an examination of socio-economic and gendered patterns of citizen service requests and responses. It focuses first on what is known about the unevenness of socio-economic and gendered impacts of austerity on service users; before turning to outline research on how citizen service requests are shaped by the social gradient and the implications of this. The article then provides background on the case study and details of the data and approach to analysis, before presenting and discussing the findings. The analysis demonstrates that austerity-driven cuts to mainstream, planned services have impacted on the services experienced by people living in more and less affluent areas of the case study, but that these impacts are disproportionately experienced by the least affluent: especially, women. The article raises important concerns about the unequal impact of the shift to co-production as a means of managing austerity.

Setting the context

Austerity, services and inequality

Since the outset of austerity, social policy scholars and practitioners have sought to understand the potentially uneven effects of different aspects of state retrenchment. A significant focus has been on the socially catastrophic impacts of welfare state contraction on incomes, poverty and wellbeing (e.g. Hardie, Reference Hardie2020; Williams, Reference Williams2020) as well as on the uneven regional impacts: de-industrialised regions in northern England and Scotland have been affected far more than elsewhere (Beatty and Fothergill, Reference Beatty and Fothergill2018). Hall (Reference Hall2020) argues that the disproportionate impacts of welfare state contraction on women ensure that austerity is an intrinsically gendered ideology (see also MacLeavy, Reference MacLeavy2011). Thus research on the impact of tax and benefit changes since 2010 found that women lose more than men at all points on the income spectrum (Portes and Reed, Reference Portes and Reed2017), with Patrick (Reference Patrick2014) also noting the heavy cumulative impact of austerity cuts to both welfare and housing provision on female-headed households.

The impacts of the retrenchment of public services in particular have been an important, if less substantial, focus of austerity research, with the evidence of disproportionate effects on already disadvantaged groups becoming more prevalent (Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Roberts and Savage2012; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Newman, John, Theodore, Macleavy and Cochrane2015). The National Audit Office (2018) outlines the extent and uneven impacts of cuts to children’s centres, youth centres, libraries, schools and FE colleges, augmenting evidence from case study research focusing inter alia on the effects of the closure of facilities and paring back of support services on low-income families, vulnerable older people, disabled groups and so on (Young Foundation, 2012; Slay and Penny, Reference Slay and Penny2013; Fitzgerald and Lupton, Reference Fitzgerald and Lupton2015). Hastings et al. (Reference Hastings, Bailey, Bramley and Gannon2017: 2021) identify three mechanisms which lead to disadvantaged groups experiencing disproportionate impacts – often despite the strategic intent of the local authority: the scale of the cuts undermining the financial capacity of councils with the most deprived populations to meet needs; the skew in service expenditure towards poorer groups, effectively ensuring that it is these groups that bear the consequences of austerity; and, finally, higher levels of reliance among poorer people on public services.

The growing literature on the gendered impacts of austerity cuts to public services suggests a disproportionate burden borne by women (Hall, Reference Hall2020). This is explained as being due to the greater use of public services by women and by female-headed households due to caring responsibilities and lower incomes (Bassel and Emejulu, Reference Bassel and Emejulu2017; Greer Murphy, Reference Greer Murphy2017; WBG, 2018). It is also because some of the most severe cuts have been to the services used mostly by women – such as children’s centres and domestic abuse refuges (Jupp, Reference Jupp2017; National Audit Office, 2018; Labour Party, 2019). Specifically in relation to environmental services, Criado Perez (Reference Criado Perez2019) notes that a ‘gender data gap’ has obscured how low incomes and caring responsibilities will lead to an overrepresentation of women in the pedestrian count – rendering invisible the potential gendered impact of environmental service cuts. Moreover, women tend to compensate for the gaps that open up within and between pared-back services with their unpaid domestic labour (Grimshaw, Reference Grimshaw2011; WBG, 2018; Gillibrand, Reference Gillibrand2020). And, finally, there is emerging evidence on women’s activism with respect to austerity. Bassel and Emejulu (Reference Bassel and Emejulu2017) foreground the organised resistances of minority women, while women’s centrality to resisting austere housing policy change is well documented (e.g. McKee, Reference McKee2015; Watt, Reference Watt2016). There is further evidence that austerity cuts to third sector organisations have undermined collective forms of activism (Needham, Reference Needham2014), and that women’s activism in particular has become less visible as it has retreated to the domestic sphere (Jupp, Reference Jupp2017). Such activism has been relied upon historically by local government to support the local delivery of services, particularly within poorer neighbourhoods.

Co-production, environmental services and inequality

In order to understand how harms caused to poorer people and to women by public service cuts might manifest in local government environmental services, it is necessary to describe the shift to co-production in this service arena, and to consider its potential implications.

The period prior to austerity was marked by investment in ‘place-keeping’ services and by the systematic auditing of neighbourhood environmental quality: part of the New Labour Government’s attempt to tackle neighbourhood disadvantage by using mainstream services more effectively (ODPM, 2005). Pre-austere environmental services were provided largely on a planned programmed basis, with operational staff responsible for routinely checking for and reporting problems beyond those met by regular, programmed provision. These checks, alongside citizen reports and complaints, drove the deployment of reactive ‘top up’ services resourced to tackle what were largely residual problems (Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Bailey, Bramley, Croudace and Watkins2009). As indicated, post 2010, austerity led not only to cuts in the budgets of these services but shifted more responsibility to citizens to use call centres, social media platforms and apps to report environmental service needs (Keep Scotland Beautiful, 2017; Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Rae, Nyanzu and Parsons2018). At the same time, across UK councils, budget cuts resulted in reduced routine programmed services and therefore in more unaddressed problems (Keep Scotland Beautiful, 2017).

A shift to the co-production of services may not seem a controversial means of cutting costs and, indeed, has been supported not only as a means by which services can be made more effective and appropriate to varying needs (Boviard, Reference Boviard2007; Durose and Richardson, Reference Durose and Richardson2015), but as a significant advance in developing inclusive citizen participation (Rosen and Painter, Reference Rosen and Painter2019). However, concerns about the social justice implications of co-production in the context of state retrenchment are emerging. Across the global north, austerity has energised neo-liberal processes of citizen responsibilisation, with both universalist, and even social ‘safety net’ modes of service provision across health, welfare as well as environmental services gradually replaced with modes that require co-production of service inputs and outcomes (Boviard et al., Reference Boviard, Van Ryzin, Loeffler and Parrado2015; Vacchelli et al., Reference Vacchelli, Kathrecha and Gyte2015; Kenway and Holden, Reference Kenway and Holden2019). Indeed, Habermehl and Perry (Reference Habermehl and Perry2021: 556) identify the phenomenon of ‘austerity co-production’ – defined as a ‘weak form of collaborative governance reshaped by resource scarcity’ and the requirement to do ‘more with less’. They argue that, in this context, the co-production of services risks amplifying pre-existing inequities and structures of disadvantage. Importantly, audit data on neighbourhood cleanliness suggest unequal effects of this shift in the mode of service provision on neighbourhood cleanliness: outcomes in less-advantaged neighbourhoods have become relatively worse compared to more-advantaged neighbourhoods (Keep Britain Tidy, 2015; Keep Scotland Beautiful, 2017).

The international literature on citizen service requests may provide an explanation for these uneven effects. This identifies a socio-economic gradient in the propensity of citizens to make service requests, especially when objective differences in need are considered (Verplanke et al., Reference Verplanke, Martinez and Miscione2010; Minkoff, Reference Minkoff2015). While it is reasonable to expect citizens to contribute to neighbourhood cleanliness by reporting problems, it is the existence of this gradient, as well as the increased reliance on requests in the austerity context, that makes their social patterning an important research concern. Thus, it is not only important to understand whether austerity cuts have led to a greater burden being placed on citizens, but how this burden is distributed and whether patterns of reporting lead to variations in the provision of services relative to need and therefore impact on environmental quality. The larger project of which this article is part considers the relationship between need and expressed need for service provision as well as disparities in environmental quality in depth. The contribution of this article is that it is the first detailed analysis of administrative data which reveals socio-economic and gendered patterns of citizen service requests, of whether these patterns change over the course of austerity, and of service responsiveness and change in responsiveness in relation to austerity.

While there is a substantial literature on citizen requests and socio-economic inequality, there is very little which explores gendered patterns. Administrative surveys which document public service use tend to be gender blind (WBG, 2018) as do studies of citizen requests. An exception is Grohs et al.’s (Reference Grohs, Adam and Knill2016) field experiment which used names distinguished by gender and ethnicity to make fake requests for German local government services in order to detect potential discrimination in response rates. The study found no independent gender effect when the requests appeared to come from ‘German’ service users, but did identify some gendered patterns – which varied in direction depending on service – when the fake requester had a ‘Turkish’ name.

Citizen service requests can be viewed as a form of political or indeed community activism which is focused on improving neighbourhood conditions. Whereas the broader, generally US, literature on this form of political activism also tends to be gender blind (e.g. Levine and Gershenson, Reference Levine and Gershenson2014; Sjoberg et al., Reference Sjoberg, Mellon and Peixoto2017) there is literature on community activism more broadly which takes a gendered perspective. It suggests unequal burdens between women and men, particularly in poorer communities: women tend to perform more of the low status, low profile tasks; men tending to those with status and influence (Brownill, Reference Brownill, Johnstone and Whitehead2004; Lowndes, Reference Lowndes2004; Beebeejaun and Grimshaw, Reference Beebeejaun and Grimshaw2011; Grimshaw, Reference Grimshaw2011). There is a rich literature on women’s activism in response to austerity (e.g. Jupp, Reference Jupp2014, Reference Jupp2017; Bassel and Emejulu, Reference Bassel and Emejulu2017; England, Reference England2017; Hall, Reference Hall2020). While it explores activisms such as resistance, advocacy and campaigning, a number of studies suggest that women’s austerity activism is increasingly focused on the maintenance of home, community and neighbourhood in the face of service cuts – on the everyday struggles born out of poverty and precarity (Hall, Reference Hall2019). Thus, Hall, Reference Hall2020 highlights the importance of such forms of ‘quiet’ activism, while the ‘low key’, ‘non-confrontational’ and ‘invisible’ nature of women’s austerity activism is identified by Jupp (Reference Jupp2017: 353–354). While Jupp, in particular, is keen to identify the potential of such activisms for transformative change, we can also conceive of the co-production of neighbourhood environmental services via citizen requests as an aspect of such quiet, invisible austerity activism. A gendered analysis of citizen requests would therefore seem important in making the work of citizen requests – increasingly necessary to community wellbeing and quality of life – visible. Understanding the gendered and socio-economic distribution of this work, whether it changes when services reduce, and how services respond are therefore important research concerns.

The case study

North Lanarkshire Council (NLC) is a useful case study to explore socio-economic and gendered patterns of service distribution partly because it can be considered as a ‘representative case’ (Yin, Reference Yin2003). The unitary authority is in Scotland’s former industrial heartland to the south of Glasgow and covers a range of diverse settlements: large towns such as Motherwell and the new town of Cumbernauld; and smaller towns and villages within more rural areas. It had an estimated population of just over 340,000 people in 2019. In terms of deprivation, NLC has 447 administrative datazones (average population 900) in total, with 144 in the most deprived quintile (32 per cent of its datazones, 31 per cent of its population) and thirty-nine in the least deprived quintile (just under 9 per cent of its datazones; just over 9 per cent of its population) as measured by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation. There are no notable variations in the population breakdown by gender within deprivations quintilesFootnote 2 . Thus, NLC is relatively more deprived than Scotland as a whole, but has a range of deprived and non-deprived neighbourhoods. NLC agreed to share a decade of data with us captured by their Customer Relationship Management system (CRM) detailing neighbourhood environmental service requests and responses. While CRM systems have been in use for some time within local authorities (King and Cotterill, Reference King and Cotterill2007), they are an under-exploited source of data. A key aspect of the article is to demonstrate how such data can be used and to what effect.

NLC’s 2019 high level strategy, continuing a politically-driven trend over the decade, commits the Council to delivering ‘inclusive growth and prosperity…with a shared ambition that aims to ensure the benefits that this brings reach all our communities, and there is a fairer distribution of wealth’ (North Lanarkshire Council, 2019: 3). The council agreed to allow the research team to analyse the CRM data held by the authority’s Environmental Assets department in pursuit of this agenda. The department is responsible for services such as refuse collection, open space maintenance and street cleaning. Services are delivered in a planned way (for example: emptying bins; regular litter picks of busy areas; programmed grass-cutting) and on a reactive basis, responding to problems identified by citizens or operatives. As with local authorities elsewhere in the UK (Gray and Barford, Reference Gray and Barford2018; Kenway and Holden, Reference Kenway and Holden2019), the Environmental Assets department has borne significant austerity-driven cuts. Between 2010/11 and 2018/19, its budget reduced by 35 per cent in real terms, with an overall reduction of 38 per cent in labour costs (detailed in project planning meetings with senior managers). The cuts were particularly severe after 2013 as the result of a savings target of £16.4 million to be achieved over three years, requiring a workforce cut of 377 FTE (North Lanarkshire Council, 2012). To manage this reduction in capacity NLC reorganised the remaining workforce with generic working and more fluid team structures. Since 2016, new mobile technology (Confirm Mobile) has been phased in to some parts of the service allowing operatives to instantly report issues they identify while going about their work. Despite these changes, budget cuts led to a reduction in planned services and to a shift to more reactive provision, a change of strategy and practice identified by managers in project meetings.

Existing research evidence shows that reductions to programmed services will increase demand for reactive services (Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Bailey, Bramley, Croudace and Watkins2009). However, the implications of this have not been fully researched and not at all in the context of austerity. The case study CRM data allows full analysis for the first time to answer two key questions:

-

1. Has the volume of citizen requests for reactive street cleaning services changed as budgets have been cut as a result of austerity and is there a socio-economic and gendered difference within this?

-

2. Has the speed and quality of the response to citizen requests changed as budgets have been cut and how does this change reflect the socio-economic and gendered profile of these requests?

Data description and methods of analysis

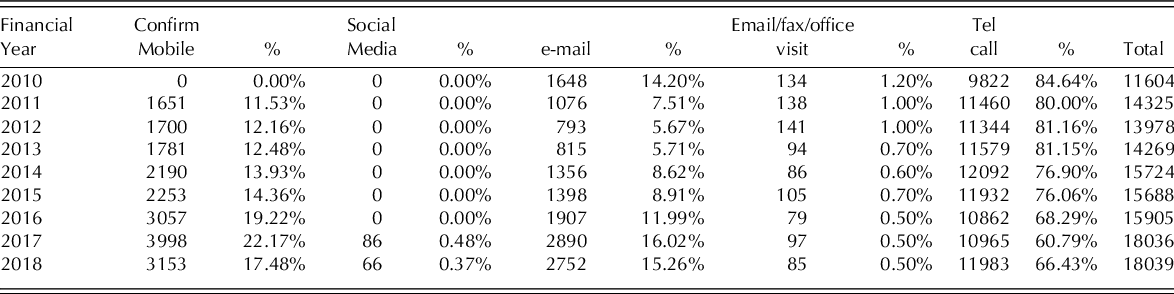

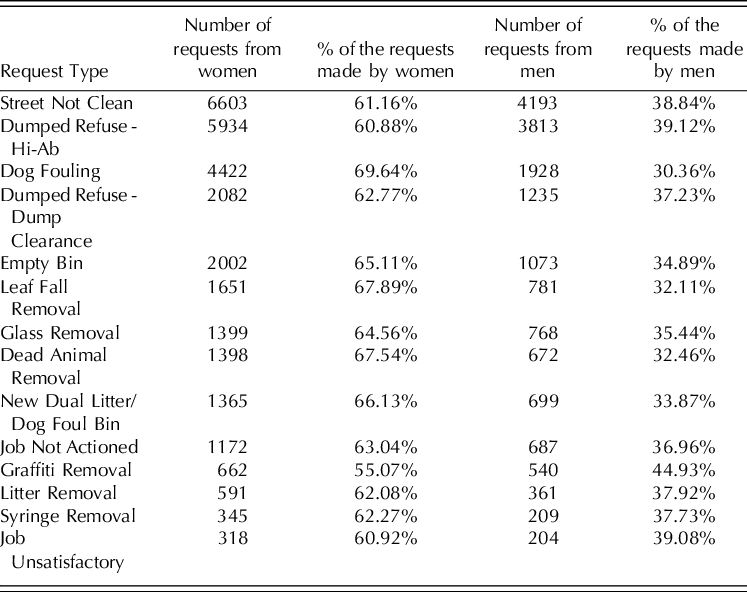

Previous similar analyses have relied on limited datasets of citizen service reports and used ‘open’ or partial datasets, without confidential, identifying data. For example, in the US, such research has relied on the open-source data feed from city authority ‘311’ non-emergency reporting services with just the location and nature of the issue reported (e.g. White and Trump, Reference White and Trump2016). Some analysis has also been done in the UK of the limited data collected through the FixMyStreet smartphone app run by the social enterprise MySociety (Sjoberg et al., Reference Sjoberg, Mellon and Peixoto2017; Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Rae, Nyanzu and Parsons2018). For this project we had full access to the ‘sensitive’ data recorded in NLC’s CRM system over the period of a decadeFootnote 3 . This included: the name and address of the citizen reporting the issue; whether an issue was reported by a citizen, council officer or elected member; the location and nature of the issue reported; the reporting mode, including by council officers using ‘Confirm’ mobile service; how long it took the council to send the request for the service to be delivered; and any reports of dissatisfaction after an issue had been reported and resolved. Overall, 151,271 records were transferred securely to the Urban Big Data Centre at the University of Glasgow following the signing of a data-sharing agreement with NLC, which ensured that there were no data protection or ethical issues arising from the study. Table 1 provides an overall summary of the number of requests in each financial year, and their mode. Table 2 shows the nature of the requests by gender.

Table 1 Service requests in North Lanarkshire Council’s CRM database (2010-2018)

Source. Authors’ analysis of North Lanarkshire Council’s CRM database

Table 2 Nature of service requests made, by gender (2010-2018 aggregated)

Source. Authors’ analysis of North Lanarkshire Council’s CRM database (NB per cents do not sum to 100, as some very small numbers excluded)

The address of the citizen reporting the environmental issue, matched to their SIMD datazone, was used as an estimate of a citizen reporter’s socio-economic status. While not all people who live in socio-economically deprived neighbourhoods experience individual deprivation, a considerable majority do. Gender was inferred from titles recorded on the CRM system (Mr, Ms, Mrs, Miss) and – where these were missing – from the full names of requesters (matched to the national baby name database). It is possible that a very small number of cases of such gender-matching may not be accurate (for example, with ambiguous first names), but we consider that this will not affect the overall analysis.

In discussing and analysing our findings below, for clarity we focus only on comparing datazones in the most and least-advantaged quintile, as well as the average across the NLC area. As noted, NLC has a greater proportion of datazones in the least advantaged quintile. The analyses therefore uses rates of reporting by head of population to ensure comparability. We primarily use descriptive, bivariate analysis as these are suitable for answering our research questions with visualisations of trends over time, with regression analyses used to test these assumptions. (Regression analyses are shown in Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Matthews and Wang2021).

Findings and discussion

Austerity and citizen service requests

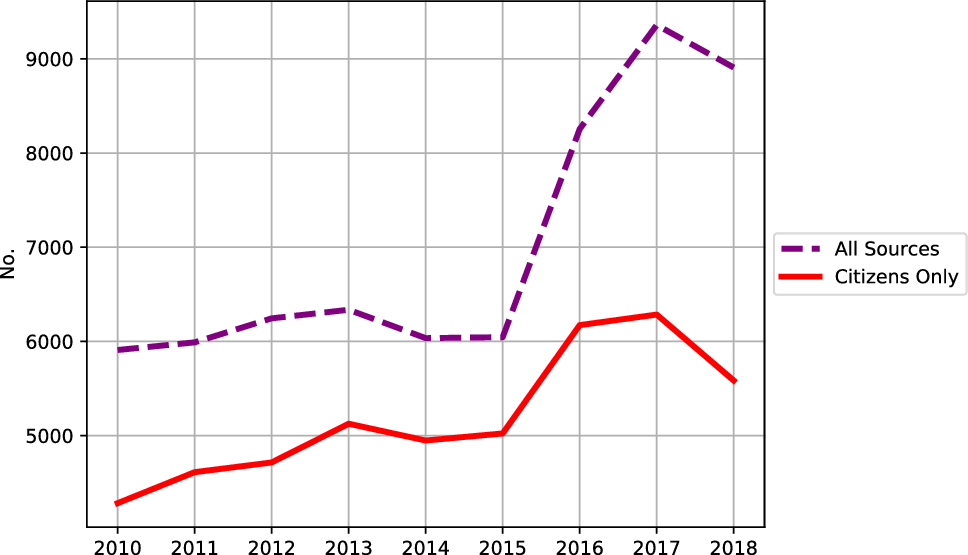

The first research question was whether the budget cuts experienced by the council, which resulted in reduced planned, programmed environmental services, impacted on the volume of citizen requests for reactive services, and any socio-economic and gender patterning within these volumes. Figure 1 shows both the change in overall annual volumes of requests for reactive services from all sources, council officers, councillors and citizens, and those requests from citizens only. Overall requests increased by nearly 60 per cent between 2010 and 2017, while citizen requests increased by 47 per cent in the same period. The slight reduction in reports which can be seen after 2017, with a greater proportionate drop in requests from citizens, is a result of the introduction of the Confirm Mobile service, allowing council operatives to readily report issues.

Figure 1. Volumes of Street Cleansing Service Requests from all sources; and from citizens only (2010-2018).

Source. Authors’ analysis of North Lanarkshire Council’s CRM database

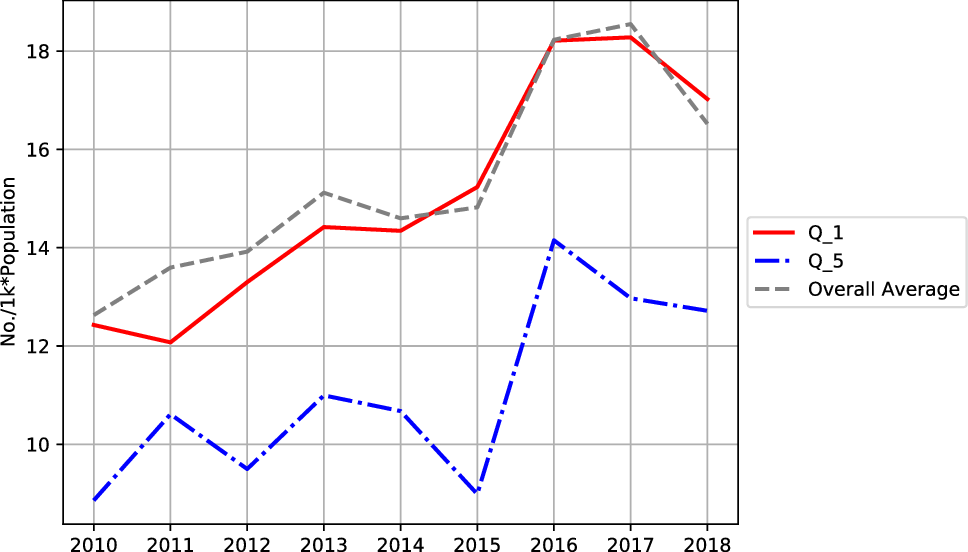

Figure 2 shows the rate of citizen requests by population in the most and least deprived quintiles as well as the average. It shows that at the outset of austerity, reporting rates were higher in the most disadvantaged quintile 1 than they were in the least disadvantaged quintile 5, a trend that has been maintained to the most recent period. Interestingly, this finding runs counter to broader evidence noted earlier that socially and economically disadvantaged citizens tend to contact public agencies to report service needs less often, especially when differentials in actual levels of need are factored in. It may be that a different dynamic is in place in the case study. While we cannot say, based on the data on reporting rates, that environmental conditions in the most deprived quintile are significantly worse than those in the least deprived quintile, this seems the most likely explanation (and will be explored in further work).

Figure 2. Volumes of Street Cleansing Service Requests from Citizens: by SIMD deprivation quintile (2010-2018). (By Head of population).

Source. Authors’ analysis of North Lanarkshire Council’s CRM database

Looking at change in reporting rates over the austerity period in Figure 2, these rose steadily and more rapidly in the most disadvantaged quintile, suggesting that austerity impacted immediately on environmental conditions in these neighbourhoods, and that these impacts intensified over time. In the case of quintile 5, rates were largely similar (around nine to eleven per thousand) for the first few years of austerity before increasing in 2016, suggesting that austerity impacted later in these neighbourhoods. In terms of absolute levels of reporting rates in the two quintiles, it was only in the fifth year of austerity that rates in the least deprived quintile reached those that had been present in the most deprived quintile as austerity began. However, by this time, rates in the most deprived quintile had increased by a further 50 per cent. Overall, the analysis suggests that austerity cuts meant that citizens across the social gradient were more likely over time to report environmental problems, but that the timing and scale of the impact of austerity differed for citizens living in deprived and non-deprived neighbourhoods.

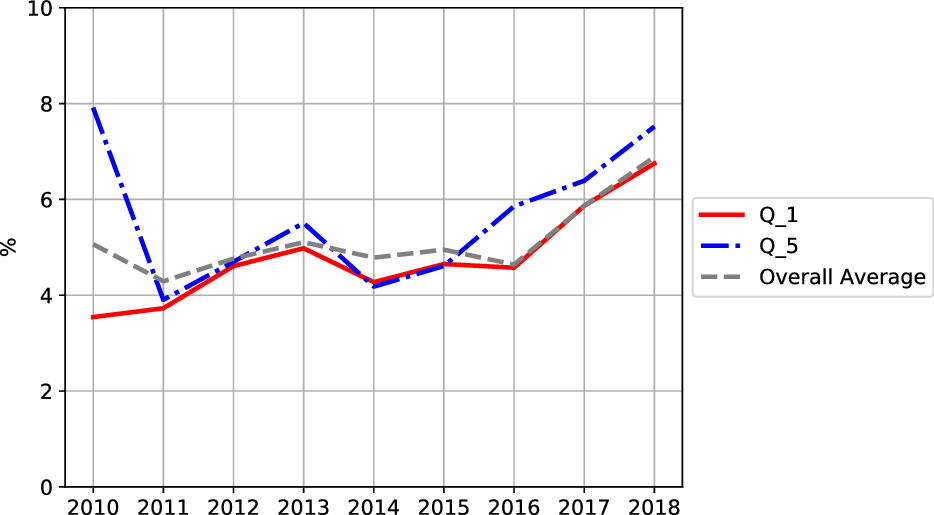

Patterns in citizen reports of dissatisfaction also allow assessment of the differential impacts of austerity (Figure 3), where ‘dissatisfaction’ is a re-report of a request not being met, or a report that the action taken was unsatisfactory, as a proportion of overall reports. An increase in the overall average rate of dissatisfaction is evident in the figure, from around five per cent in 2010 to seven per cent in 2018.

Figure 3. Rates of Reports of Citizen Dissatisfication with Service Request Outcomes: by SIMD deprivation quintile (2010-2018).

Source. Authors’ analysis of North Lanarkshire Council’s CRM database

In the most deprived neighbourhoods, dissatisfaction rates began to rise in the first four years of austerity, plateaued, and then rose again fairly sharply from 2016, with an almost doubling of dissatisfaction rates between 2010 and 2018 (from 3.5 per cent to 6.7 per cent). This suggests a substantial impact of austerity on how citizens in poorer places experience the service. Moreover, an increasing share of the council’s dissatisfaction reports came from its most deprived neighbourhoods as austerity progressed – from 21 per cent in 2010 to 31 per cent in 2018 (See Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Matthews and Wang2021). From 2011 on, the trend in the least deprived neighbourhoods is similar: there is also an almost doubling of the dissatisfaction rate. But in contrast to the service request rate shown in Figure 2, the dissatisfaction rate is much closer to the council’s overall average. Taken together, Figures 2 and 3, suggest that austerity cuts began to impact on service provision in the least deprived areas around 2015/16 – and that, since then, citizens living in such areas have been more motivated to report problems and more dissatisfied with the outcome of such reports. Analysing citizen request and dissatisfaction rates therefore shows that while austerity impacted on citizens in both affluent and deprived neighbourhood contexts, it took five years longer for it to bite in the council’s most affluent areas compared to its least.

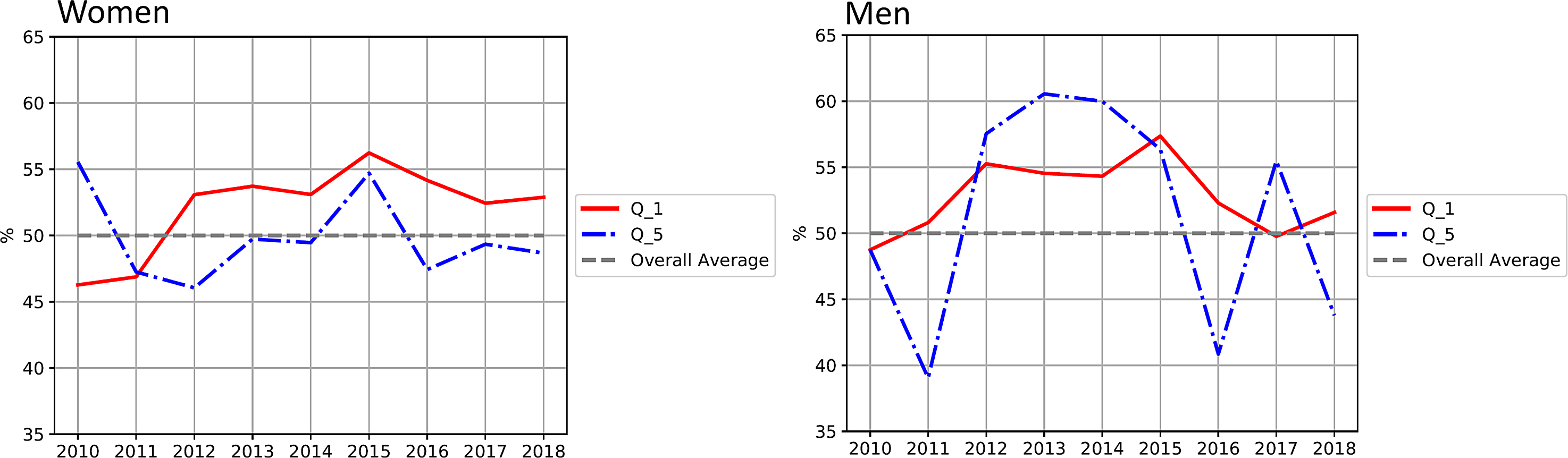

Gendered patterns

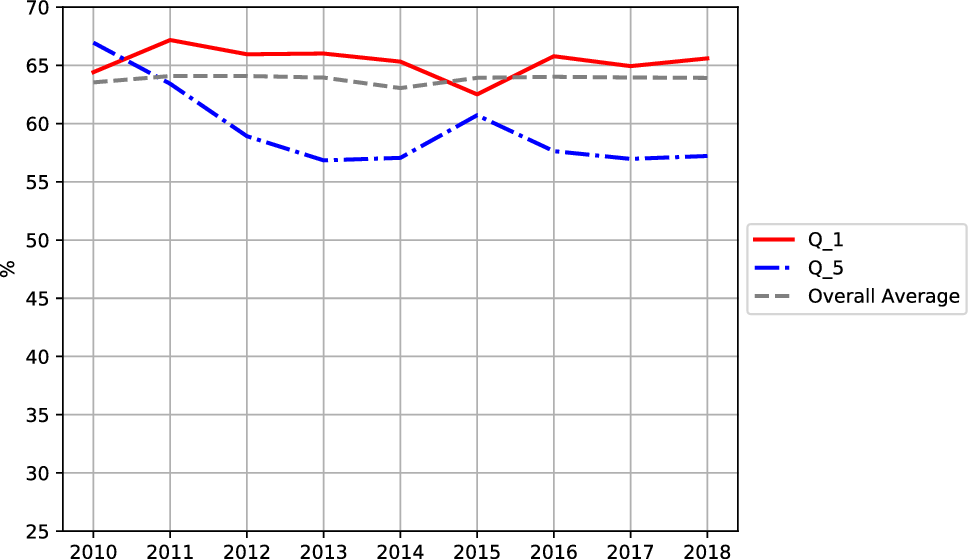

Turning now to explore gendered patterns in service requests and dissatisfaction, Figure 4 shows that overall, around 64 per cent of all gender-matched service requests are made by women, 36 per cent by men – a pattern which, as noted earlier, cannot be explained by population differences. Table 2 – shown previously – demonstrates that this pattern broadly holds for the majority of the different kinds of service requests made. Gender disparities are greatest with respect to dog fouling – in fact, women make more than double the number of complaints that men make about this issue. This may reflect women’s disproportionate childcare responsibilities, the use of pavements in discharging these and the consequential health risks to those in their care (Criado Perez, Reference Criado Perez2019). The constant ratio over the period shown in Figure 4 suggests that austerity cuts to programmed services did not impact on gendered differences in the propensity to request services. When we analyse women’s share of the reporting burden in the most and least deprived areas, there is more variation over the period, but again no notable change as a result of austerity.

Figure 4. Women’s share of Citizen Street Cleansing Service Requests: by SIMD deprivation quintile. (2010-2018).

Source. Authors’ analysis of North Lanarkshire Council’s CRM database

There are, however, gendered differences in reporting rates between and within neighbourhood deprivation quintiles. Looking first at the most deprived neighbourhoods: the proportion of reports made by women is consistently higher than the proportion of reports made by women on average and in the most advantaged neighbourhoods. As men’s rates of reporting are the mirror of women’s rates – we can see that men in deprived areas are less likely to report street cleaning problems than men on average. We tested this using a regression analysis which showed this gendered trend was present even when controlling for neighbourhood deprivation and gendered population of datazones (reported in Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Matthews and Wang2021). These patterns suggest not only that women in deprived areas bear more of the burden of reporting street cleaning issues than men in these neighbourhoods, but that they also bear more of this burden relative to men, when compared with women in less deprived areas. In the most advantaged neighbourhoods, it is striking that while women make the majority of requests, the burden of reporting is shared more equally here than in deprived neighbourhoods.

We have also analysed gendered, socio-economic patterns in the tendency of an individual citizen reporter to make multiple service requests (Not shown. See Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Matthews and Wang2021). This shows that there are higher numbers of citizens who make multiple requests for services in deprived neighbourhoods, and that these ‘super reporters’ are almost always women: there are ten women who have made between twenty to sixty reports over the nine years, and one who made 144. This volume of reporting by single citizens does not occur in other quintiles, except in quintile 2 where again there are some women who have made multiple reports and a man who has made circa 100 reports. These findings confirm that women do more of this aspect of community-building and quiet activism than men, particularly in more disadvantaged communities. Co-production is not evenly experienced and may be a burden borne disproportionately by women.

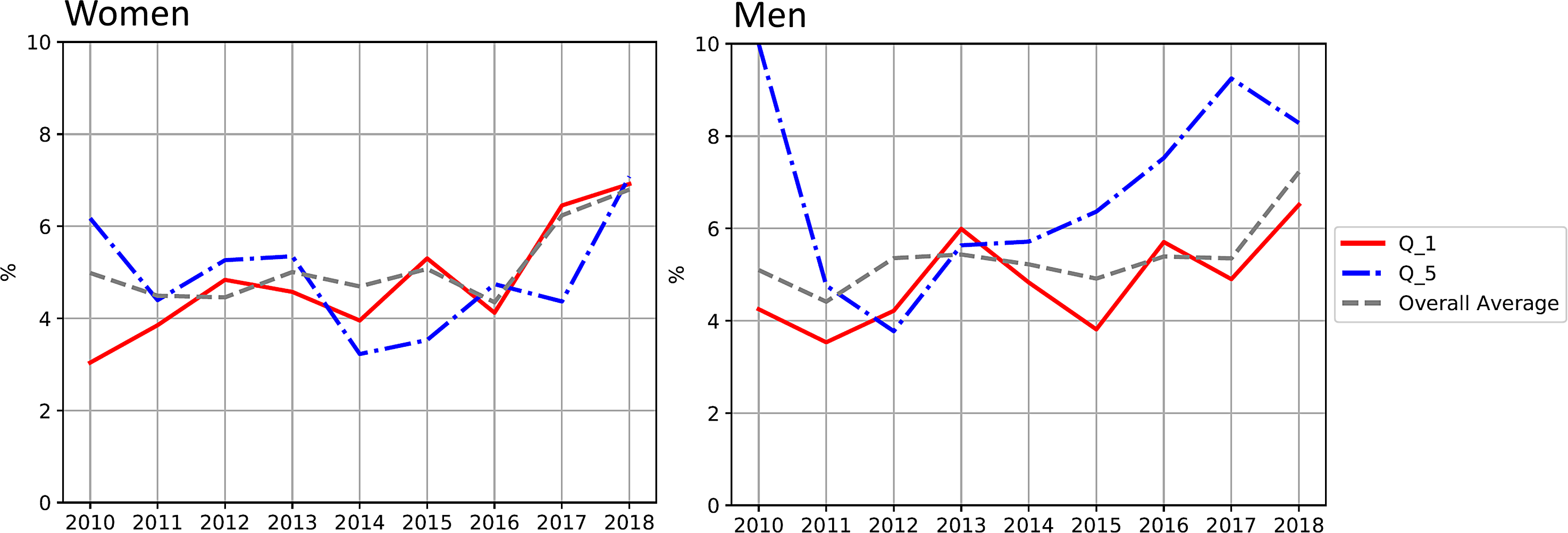

Turning to examine gendered patterns of dissatisfaction (Figure 5): overall, both women and men experienced growing dissatisfaction in the later stages of austerity, with the rate for women increasing a year earlier than for men. As with citizen requests, gender patterns become more visible when viewed in their neighbourhood deprivation context. It is notable that the rate at which women in the most deprived areas reported their dissatisfaction more than doubled between 2010 and 2018 (from 3 per cent to 6.8 per cent) whereas men’s dissatisfaction did not increase to the same degree. Our gendered analysis thus suggests that the increase in overall dissatisfaction with services in deprived neighbourhoods identified above was driven by the increased dissatisfaction experienced by women.

Figure 5. Gendered Rates of Reports of Citizen Dissatisfication with Service Request Outcomes: by SIMD deprivation quintile (2010-2018).

Source. Authors’ analysis of North Lanarkshire Council’s CRM database

In the least deprived neighbourhoods, the most notable trends were the increase in men’s dissatisfaction and the finding that men’s rate of dissatisfaction is higher than women’s. This may suggest differences in gender relations in these neighbourhoods, where men bear a more equal share of reporting environmental problems, and are apparently more readily dissatisfied when they do. Interestingly, rates of dissatisfaction are greater for men in advantaged neighbourhoods than for all groups regardless of gender and deprivation. As austerity progressed, their dissatisfaction reports became an increasingly substantial share of the total dissatisfaction reports (Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Matthews and Wang2021). This suggests that, whereas making a service request may be a low status activity, and therefore more likely to be borne by women, expressing dissatisfaction may be perceived as more formal and of higher status and thus taken on by advantaged men. Expressing dissatisfaction requires more confidence than requesting service and implies having clear expectations of service providers. These data therefore make visible the differences in the quiet dynamics between women and men living in different socio-economic circumstances, suggesting gendered differences which vary between different social contexts.

Austerity and council service responses

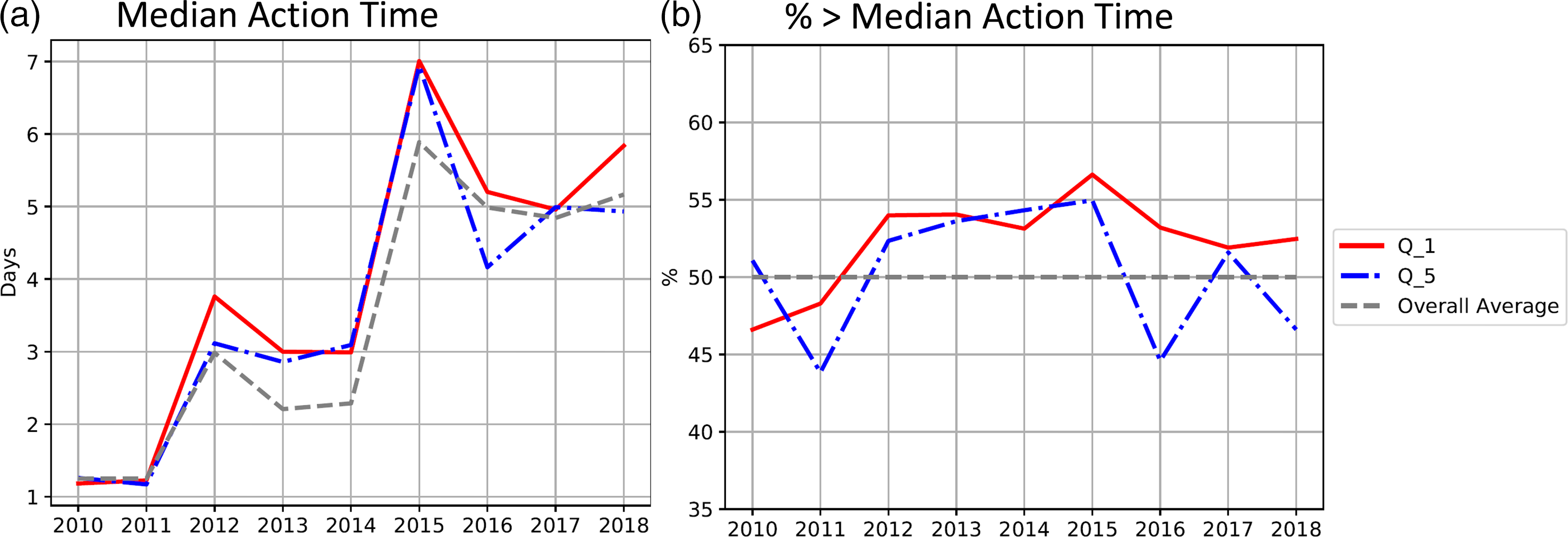

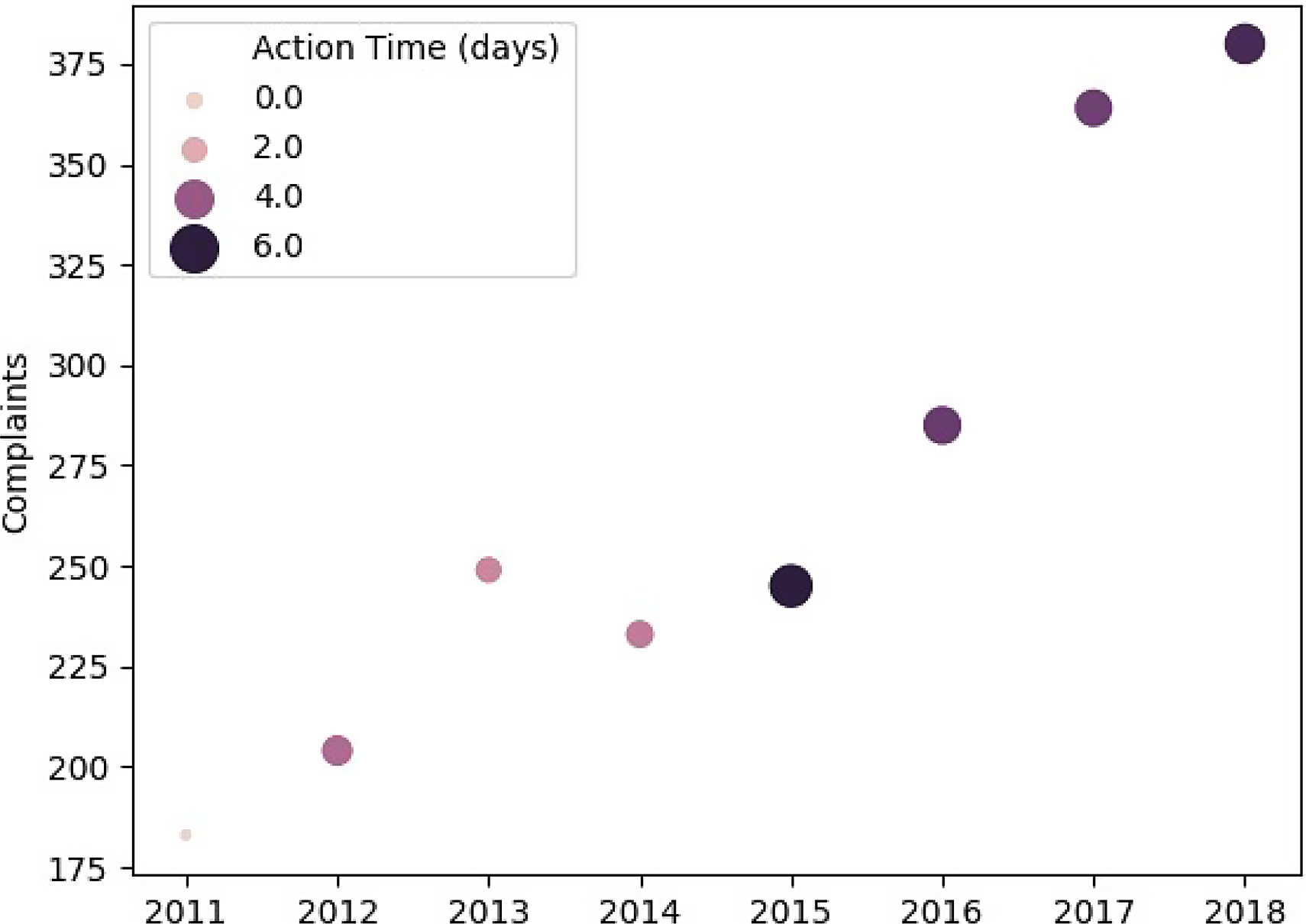

Our second research question is whether the response of the case study council to citizen reports of environmental problems changed over the austerity period, and whether any change has a gendered or socio-economic dynamic. As indicated, the CRM database captures how long it takes the council to respond to citizen reports. Figure 6a shows that the overall average time taken by the council to resolve a service request increased substantially over the austerity period – from less than a day in 2010 to between five and six days by 2015–2018. This significant increase in median action times will reflect the increase in citizen reports and NLC’s capacity to respond promptly. In Figure 7, the strong positive correlation between the increase in time taken to action requests and the rise in citizen dissatisfaction rates is shown. Causation cannot of course be assumed and the rise in citizen dissatisfaction is likely driven by a range of factors.

Figure 6. (a) Median time taken to action a Street Cleansing Service Requests from Citizens: by SIMD deprivation quintile (2010-2018). (b) Per cent of Street Cleansing Service Requests from Citizens that take longer than median action times: by SIMD deprivation quintile (2010-2018).

Source. Authors’ analysis of North Lanarkshire Council’s CRM database

Looking again at Figure 6a, as well as the overall average, the Figure also shows differences in average response times between the most and least deprived neighbourhoods over the period of austerity. Notably, it suggests that there was no difference in median action times at the outset of austerity, but that a difference emerged over time. Figure 6b shows the percentage of service requests made by citizens in the most and least deprived neighbourhoods that were above and below the overall median to highlight how median action times vary with deprivation. From this, it is clear that, since 2011, reports made by citizens living in the most deprived neighbourhoods have taken longer to action than average. The figure also shows, however, that between 2012 and 2015 delayed action times were also more likely in the least deprived neighbourhoods. By analysing the distribution of delayed action times in this way, we can see that there have been impacts of austerity on neighbourhoods at the opposite ends of the deprivation spectrum, but that the impact was felt earlier and more consistently in the most disadvantaged areas.

There is no difference in the overall average action times taken by the council to requests from women and men and the timing and scale of the increase in action time noted above is similar for women and men (Not shown. See Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Matthews and Wang2021). However, as Figure 8 demonstrates, there are some gendered differences when socio-economic status is also in view. The figure shows the proportion of requests in each quintile that are above or below the overall average at different points in time. It shows that deprived women experience delayed action times consistently from 2011, and much more so than better off women. In the later part of austerity, they also experience a greater delay than their deprived male counterparts. Indeed, women in deprived areas experience more delay than any other group distinguishable by gender or deprivation. This may explain the doubling in their dissatisfaction rate during austerity, as well as the existence of women ‘super reporters’ in deprived neighbourhoods.

Figure 7. Citizen Dissatisfaction with Service Request Outcomes by Median time taken to action a Service Request (2010-2018).

Source. Authors’ analysis of North Lanarkshire Council’s CRM database

Figure 8. Per cent by Gender of Citizen Street Cleansing Service Requests that take longer than median action times: by SIMD deprivation quintile (2010-2018).

Source. Authors’ analysis of North Lanarkshire Council’s CRM database

Overall though, there is no indication of direct gender bias in service response. In order for bias – conscious or unconscious – to occur, staff need to know the gender of the citizen making the service request. While call centre staff are likely to make assumptions about gender, gendered information is not passed to operatives, reducing the possibility that gender-based prioritisation could take place. The existence of a wider ‘gender data gap’ means that the question should nonetheless be explored. In contrast, the potential for socio-economic and spatial bias is clearer: staff, particularly operational staff in the field, will have an awareness of the socio-economic status of the neighbourhoods they work in, presenting the possibility that work can be prioritised accordingly. However, our analysis indicates that – even in the absence of direct gender bias – that the interaction between the societal burden which women have taken on disproportionately (in managing their neighbourhoods’ environmental needs and socio-economically skewed service distributions) leads to gender inequality. In this case study the lived experience of women in deprived neighbourhoods of austerity cuts is that they both bear a disproportionate burden of reporting service needs and of delay in having them resolved.

Conclusion

Concern over how public service provision relates to societal inequality was reignited by a decade of austerity. While discussion of disproportionate impacts is plentiful, it is also clear that the detailed data on service use and provision needed for robust conclusions is often lacking. The analysis in this article is, however, based on an under-exploited source of administrative data – a council’s CRM database. This allowed fine-grained analysis of the specific impacts of austerity cuts. Thus, our analysis demonstrates the deleterious impact of austerity on the quality of environmental services experienced by people living in the most and the least deprived neighbourhood contexts, increasing their need to report problems, delaying response times and amplifying dissatisfaction rates. While this suggests that the pain of austerity is to an extent a shared experience, the analysis also shows that the pain has not been shared equally. People in deprived areas have suffered worse effects, and when we make gender patterns visible, it is also clear that women in deprived areas are the worst affected. Detailed empirical evidence such as this is valuable not only in informing scholarly debate: by making visible underlying structures, policy and strategy can be developed which is capable of tackling very specific inequalities.

By making women visible, the article adds to our understanding of the potential downsides of the shift to co-production in service provision in the context of austerity. We know that women, particularly those living in deprived neighbourhoods, have historically borne a greater burden of the everyday work of maintaining their immediate neighbourhood, adding to already significant first and second shifts of paid employment and unpaid domestic labour. In this article we have seen that ‘austerity co-production’ highlighted by Habermehl and Perry (Reference Habermehl and Perry2021) has shifted some of the work previously funded from collective taxation onto women – especially, disadvantaged women. Indeed, we might think of forms of activism which involve filling the service gaps left by austerity service cuts, as a hidden ‘third shift’ borne quietly by women. Citizen requests take time, effort and, in this case, require the prioritisation of reporting neighbourhood environmental problems over other activities. As such, they are an unrecognised, overlooked, but increasingly essential element of ‘invisibilised’ lower status community building women’s work.

Finally, it is worth noting that NLC agreed to this research as part of its strategy to tackle inequality and promote fairness. The relatively small deprivation and gender effects identified in the article are likely to be magnified in councils which have been subject to even more severe budget cuts and with less of a focus on inequality. Despite this caveat, it is important to recognise the cumulative impact of ‘small’ everyday experiences of austerity on those who are already disadvantaged.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this article was made possible by the Economic and Social Research Council’s support for the Urban Big Data Centre (ES/L011921/1 and ES/S007105/1). The authors are grateful to the two anonymous referees for their constructive feedback on this article.