Clinical characteristics of major depressive disorder aggregate in families. Reference Schreier, Höfler, Wittchen and Lieb1 There are relatively few studies of vulnerability to anxiety disorders – especially when excluding panic disorder. Reference Merikangas2 Important but unanswered questions are whether the familial aggregation differs with respect to the type and clinical characteristics of anxiety. Reference Biederman, Petty, Faraone, Hirshfeld-Becker, Henin, Dougherty, Lebel, Pollack and Rosenbaum3 The aim of this study is to examine the familial aggregation of anxiety disorders in mothers and their children by differentiating various clinical characteristics as well as examining specific DSM–IV 4 anxiety disorders in a community sample.

Method

Data presented are based on a cohort of the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology (EDSP) study (a longitudinal survey of a representative community sample) of 933 mother–child pairs. The offspring of this report were aged 14–17 years at baseline and followed up twice. In a separate parent survey their biological mothers were also interviewed. Anxiety disorders according to DSM-IV were assessed. Details of the design, methods and assessment of the EDSP study have been previously reported. Reference Schreier, Höfler, Wittchen and Lieb1,Reference Lieb, Isensee, von Sydow and Wittchen5,Reference Wittchen, Perkonigg, Lachner and Nelson6

Maternal diagnostic status refers to the lifetime status of DSM–IV anxiety disorders reported by the mother up to the date of the interview. For offspring, diagnostic information from baseline (lifetime status) and the two follow-ups (interval status) was considered. Three clinical characteristics in mothers were defined as follows: (a) impairment in daily life during the worst episode, comparing the answers ‘very much’/‘a lot’ with ‘not at all’/‘somewhat’; (b) early onset (before age 20); (c) at least two anxiety disorders based on the DSM–IV diagnostic criteria (lifetime). Reference Schreier, Höfler, Wittchen and Lieb1

Age-specific cumulative lifetime incidences were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method. Reference Andersen, Keiding, Armitage and David7 Differences between curves for children of mothers without any anxiety disorder, as a reference group, were assessed with hazard ratios (HRs) from the stratified Cox model for discrete time. The proportional hazards assumption was tested with Schoenfeld residuals. Multinomial logistic regressions with odds ratios (ORs) were used to estimate the associations between specific anxiety disorders in mothers and their children, and between clinical characteristics of maternal anxiety and overall rates of anxiety disorders in the offspring. Reference McCullagh and Nelder8 In all analyses, gender and age of offspring were controlled for. To examine possible gender heterogeneity in the ORs we additionally assessed interactions with gender of offspring. Reference Schreier, Höfler, Wittchen and Lieb1,Reference Lieb, Isensee, Höfler, Pfister and Wittchen9

Results

In the mothers, the prevalence of any anxiety disorder was 27.4% and in offspring 33.0%. Mothers with and without anxiety differed with respect to current living situation (with partner: 76.5% v. 83.8% respectively) and educational level (higher education: 20.5% v. 29.1% respectively).

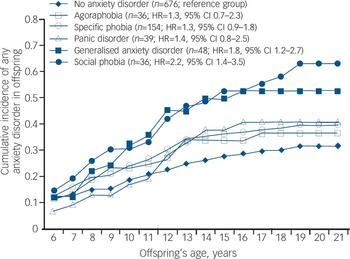

Figure 1 shows the cumulative probability for offspring of developing any type of anxiety disorder by maternal anxiety status. Hazard ratios for the children of mothers with social phobia or generalised anxiety disorder and of mothers with any anxiety disorder (HR=1.3; 95% CI 1.1–1.7) were different from those of children of mothers with no anxiety disorder. In none of the analyses was the proportional hazards assumption violated, indicating that anxiety disorders do not begin earlier in children of mothers with a specific anxiety disorder compared with children of mothers with no anxiety disorder. Also, no interactions with gender of offspring were found. When additional analyses were conducted controlling for maternal comorbid anxiety disorders and sociodemographic variables, the results remained robust.

Fig. 1 Age at onset of any anxiety disorder in offspring according to maternal anxiety status.

In logistic regression analyses assessing associations between specific anxiety disorders in mothers and in offspring, higher rates of panic disorder (7.4% v. 1.3%, OR=5.0, 95% CI 1.5–16.9) and phobia not otherwise specified (20.2% v. 9.1%, OR=2.5, 95% CI 1.1–5.5) in children of mothers with v. without generalised anxiety disorder were found. Also, an elevated risk for separation anxiety was demonstrated in children of mothers with v. without panic disorder (89.2% v. 1.7% respectively, OR=6.3, 95% CI 1.2–33.5).

We examined whether mothers' degree of impairment, early onset and number of anxiety disorders were associated with the rate of anxiety disorders in offspring. Offspring anxiety rates were raised only when mothers met criteria for anxiety disorder with the three clinical characteristics. The rate of anxiety disorders in children of mothers with no anxiety disorder was 30.7% (reference group), the rates in the children of mothers with anxiety disorder and the indicated clinical characteristics were 43.5% for strong impairment (OR=1.6, 95% CI 1.02–2.6), 41.0% for early onset (OR=1.6, 95% CI 1.03–2.4) and 45.6% for at least two anxiety disorders (OR=1.9, 95% CI 1.1–3.2). The respective rates for offspring of mothers with an anxiety disorder but without the indicated clinical characteristics were 35.8% for no maternal impairment (OR=1.3, 95% CI 0.8–1.9), 36.4% for late onset (OR=1.2, 95% CI 0.7–2.0) and 35.6% for only one maternal anxiety disorder (OR=1.2, 95% CI 0.8–1.8). There were no differences between children of mothers with anxiety disorder with and without the examined clinical characteristics. There was also some indication for a dose–response relationship regarding the number of maternal characteristics and offspring anxiety risk (details available on request).

Discussion

We demonstrated that there was a higher rate of anxiety disorders in children of mothers with an anxiety disorder than in children of mothers with no anxiety disorder, confirming and extending previous findings in the literature. Reference Beidel and Turner10,Reference Bijl, Cuijpers and Smit11 A particular strength of our study is that it differentiated specific anxiety disorders in the mothers. The results suggest that maternal social phobia and generalised anxiety disorder especially increase the risk of anxiety disorders in the offspring, which indicates that in these disorders a diathesis to anxiety in general may be transmitted. Regarding specific anxiety disorders in offspring, it is noteworthy that separation anxiety in children was only associated with maternal panic disorder. Reference Unnewehr, Schneider, Florin and Margraf12 Thus, it could be an early manifestation of panic disorder that is particularly observable in children with a familial vulnerability for panic disorder. Reference Biederman, Petty, Hirshfeld-Becker, Henin, Faraone, Dang, Jakubowski and Rosenbaum13 However, from a longitudinal perspective, Brückl et al Reference Brückl, Wittchen, Höfler, Pfister, Schneider and Lieb14 report less pronounced results.

Another strength of this study is that clinical characteristics of anxiety could be examined with respect to their role in the familial aggregation of anxiety. To our knowledge, such analyses have only rarely been presented. Reference Biederman, Petty, Faraone, Hirshfeld-Becker, Henin, Dougherty, Lebel, Pollack and Rosenbaum3,Reference Goldstein, Wickramaratne, Horwath and Weissman15 Interestingly, offspring differing in maternal anxiety status did not differ in age at first onset of anxiety, possibly because phobias in particular develop relatively early in life, irrespective of family history. Elevated rates of anxiety disorders in the children were observed only when the mother met the diagnostic criteria for anxiety disorders with the three clinical characteristics. Thus, only more severe maternal anxiety disorder is associated with an elevated rate of anxiety disorders in children. However, when interpreting the results, it is important to consider that lifetime assessments were retrospective and that children had not exited the risk period for onset of all of the anxiety disorders.

In conclusion, our results suggest that maternal anxiety disorders are associated with anxiety disorders in offspring. Furthermore, the type of maternal anxiety disorder (especially social phobia and generalised anxiety disorder) and its severity appear to contribute to mother–offspring aggregation of anxiety.

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology (EDSP) study and is funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research. For funding details and a list of principal investigators see online supplement. Parts of this paper have been reported previously in a PhD thesis: Schreier A. (2005) Psychopathologie bei Kindern von Müttern mit einer Major Depression oder Angststörung (Psychopathology in the children of mothers with major depression and anxiety disorders). Technical University of Dresden, Germany.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.