On June 1, 2020, a little more than two months after the World Health Organization’s COVID-19 pandemic declaration, our editorial team assumed the leadership of the American Political Science Review (APSR). Although this confluence of events makes it difficult to isolate the pandemic’s effect on new submissions and review processes, this article describes submission and review patterns in the two and a half years before and after the onset of the pandemic and the editorial transition. It describes our preliminary observations regarding what the patterns suggest about the pandemic’s impact on the APSR. Footnote 1

NEW SUBMISSIONS

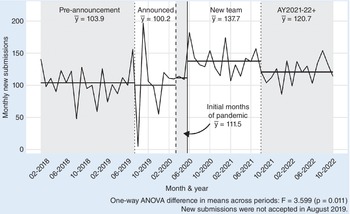

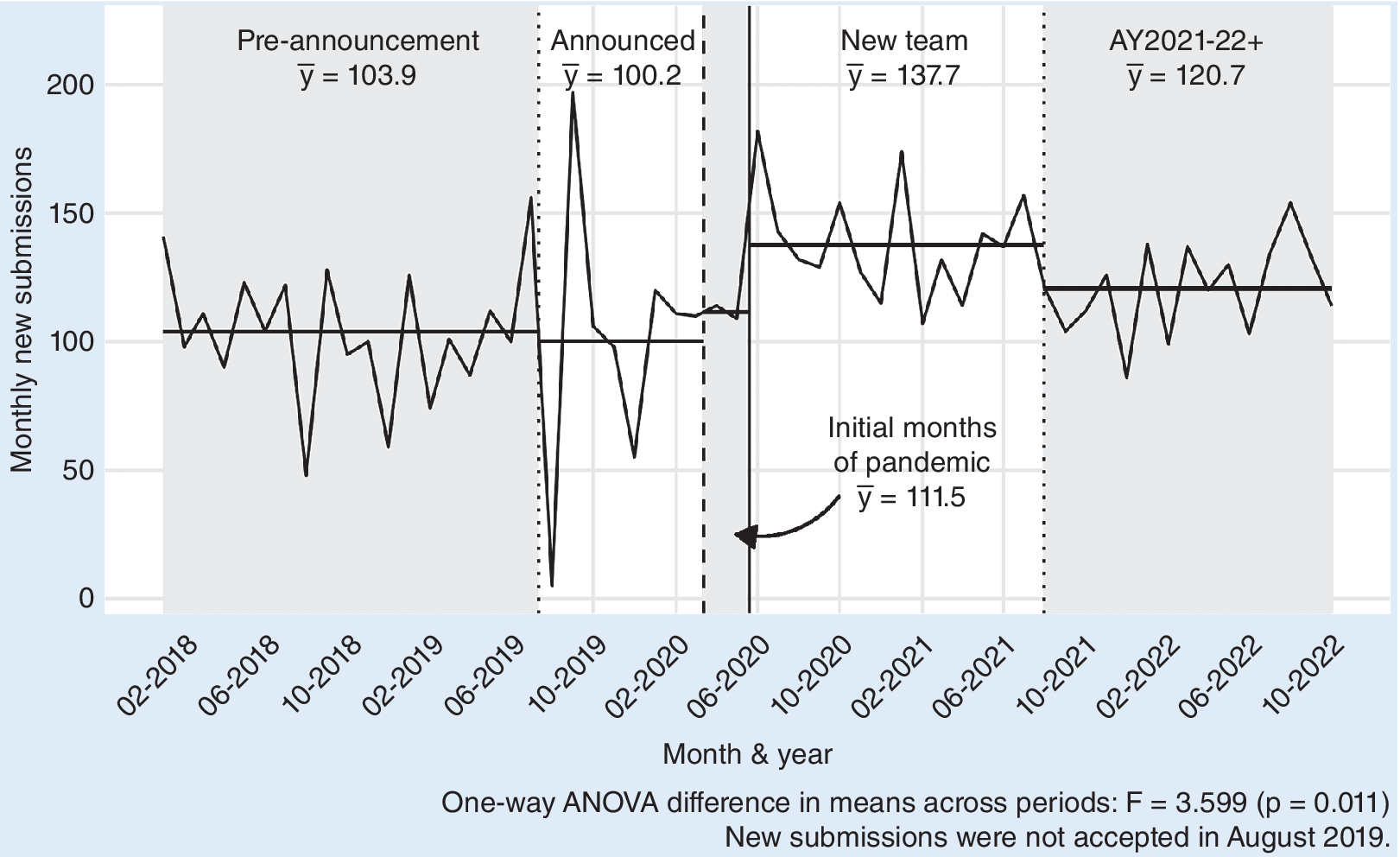

Figure 1 plots the number of new submissions by month with means for five periods related to the COVID-19 pandemic or the editorial transition. The pre-announcement period—from January 2018 through the end of July 2019, when the American Political Science Association (APSA) announced that our team would lead the journal in June 2020 (American Political Science Association 2019)—serves as our pre-pandemic, pre-editorial transition baseline or reference category. The announcement of a new team may change author behavior if some authors believe their research will fare better or worse under the current or a new team. Average monthly submissions were only slightly lower between August 2019 and March 2020 than during the pre-announcement period (i.e., -3.7 fewer manuscripts per month). During the initial months of the pandemic—from the beginning of April through the end of May 2020—average monthly new submissions rebounded, averaging 111.5 per month. Despite widespread concern that the effect of the pandemic and the shift to remote teaching would affect scholarly productivity (Kim and Patterson Reference Kim and Patterson2022; Myers et al. Reference Myers, Tham, Yin, Cohodes, Thursby, Thursby, Schiffer, Walsh, Lakhani and Wang2020; Shalaby, Allam, and Buttorff Reference Shalaby, Allam and Buttorff2020), average monthly new submissions increased to 137.7 during the first year of our editorial leadership (June 1, 2020–July 31, 2021). This also was the same year that K-12 education and childcare were most impacted during the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 2

Figure 1 Monthly New Submissions, 2018–2022

After this initial uptick, however, average monthly new submissions decreased to 120.7 per month in the second academic year of the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., from August 2021 onward). This number was still higher, however, than the pre-pandemic, pre-transition baseline average. Perhaps researchers were able to submit new manuscripts during the lockdown period in the initial months of the pandemic but, as it continued, online teaching and travel restrictions disrupted research plans, particularly for new projects and early-career researchers (Breuning et al. Reference Breuning, Fattore, Ramos and Scalera2021; Cahusac de Caux Reference Cahusac de Caux, de Caux, Pretorius and Macaulay2022; Douglas et al. Reference Douglas, Settles, Cech, Montgomery, Nadolsky, Hawkins, Ma, Davis, Elliott and Cheruvelil2022; Jamali et al. Reference Jamali, Nicholas, Sims, Watkinson, Herman, Boukacem-Zeghmouri and Rodríguez-Bravo2023; Squazzoni et al. Reference Squazzoni, Bravo, Grimaldo, García-Costa, Farjam and Mehmani2021; Sverdlik, Hall, and Vallerand Reference Sverdlik, Hall and Vallerand2022). Although it is not conclusive, this preliminary descriptive evidence is consistent with a short-term boost in new submissions, with a subsequent lull in the second and third years of the pandemic. That the editorial transition may have boosted new submissions is equally possible. The sharp increase in new submissions in June 2020 compared to May 2020 is consistent with this argument. When we regress monthly new submissions on a set of indicators for time period, the first 15 months of our tenure is the only period with average monthly submissions statistically different from the pre-announcement (i.e., pre-August 2019) baseline.Footnote 3

Substantive, Methodological, and Representational Diversity of New Submissions

Our editorial team’s vision explicitly advocated increasing the substantive, methodological, and representational diversity of the APSR (The Editors 2019). This section explores new submission patterns along these dimensions. If we observe larger increases in submissions that are consistent with our vision relative to traditional submission patterns, it suggests that the editorial transition—rather than the pandemic—explains the overall increase in new submissions during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

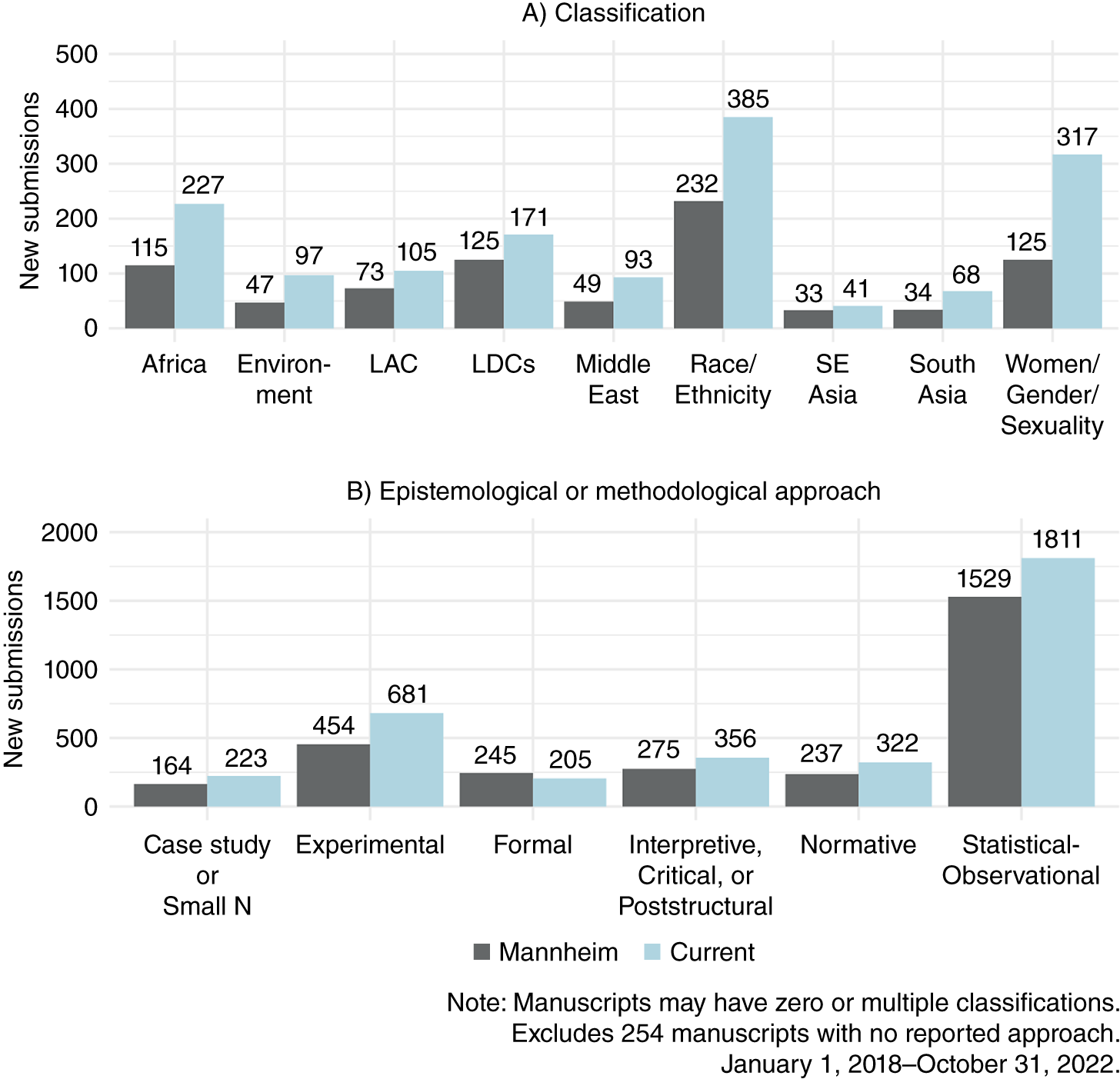

With regard to substantive focus, we expressed an interest in publishing more work on race and ethnicity; women, gender, and sexuality; the environment; and politics in the Global South. As part of the submission process, corresponding authors can (but are not required to) choose multiple classifications for their manuscript. Figure 2 (panel A) plots the number of submissions with substantive classifications identified as priorities for our team.Footnote 4 The large increases across several substantive classifications are consistent with the possibility that the APSR attracted new submissions that otherwise may have been submitted to other political science journals.

Figure 2 New Submissions by Substantive Focus and Epistemology or Methodology, 2018–2022

Corresponding authors also are asked to classify the analytic or methodological approach used in their manuscripts. Our team encouraged new submissions using less common epistemological (e.g., interpretive, critical, postcolonial, or post-structural) or methodological (e.g., case study, ethnographic, or small N) approaches in political science. Since the 2020 editorial transition, the APSR has received 29.5% more submissions that are classified as primarily interpretive, critical, or post-structuralist in their epistemology and 36% more submissions using case-study, ethnographic, or other small-N methodologies (see figure 2, panel B). Although new submissions in each category have increased since June 2020, these increases are outpaced by the absolute increase in the number using quantitative, observational (282, or 18.4%), and experimental (227, or 50%) methods. These latter approaches continue to be the most common primary methodologies reported for submissions to the journal.Footnote 5 Assuming that the pandemic’s early effects on research output did not vary substantially by substantive topic, epistemology, or methodology, then the evidence suggests that some portion of the increase in new submissions after June 2020 may be attributed to authors who responded to our team’s public commitments to diversify the approaches used in the APSR’s published scholarship.

At the same time, we know that global and systemic health inequalities, closure of pre-K childcare facilities and K-12 schools, and the shift to online learning had uneven impacts on political scientists’ productivity (Breuning et al. Reference Breuning, Fattore, Ramos and Scalera2021; Shalaby, Allam, and Buttorff Reference Shalaby, Allam and Buttorff2021; Simien and Wallace Reference Simien and Wallace2022), making it difficult to disentangle the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic from our editorial transition. First, we considered authors’ regional location. Our submissions data have reliable location information only about the corresponding author. Using this indicator, new submissions increased by 19.6% (165 additional new submissions) from Europe, 24.8% (446 new submissions) from North America, and 40.4% (145 new submissions) from other global regions since the June 2020 editorial transition. Although the largest proportional increase in new submissions was from outside of North America and Europe, the absolute number of new submissions from other global regions (504) was still about half that of Europe (1,008) and more than four times fewer than new submissions from North America (2,244). Nonetheless, the increase in new submissions from outside of Europe and North America is consistent with qualitative research that finds that the COVID-19 pandemic provided new opportunities for scholars in the Global South to be part of global research partnerships (Cahusac de Caux Reference Cahusac de Caux, de Caux, Pretorius and Macaulay2022, 368).

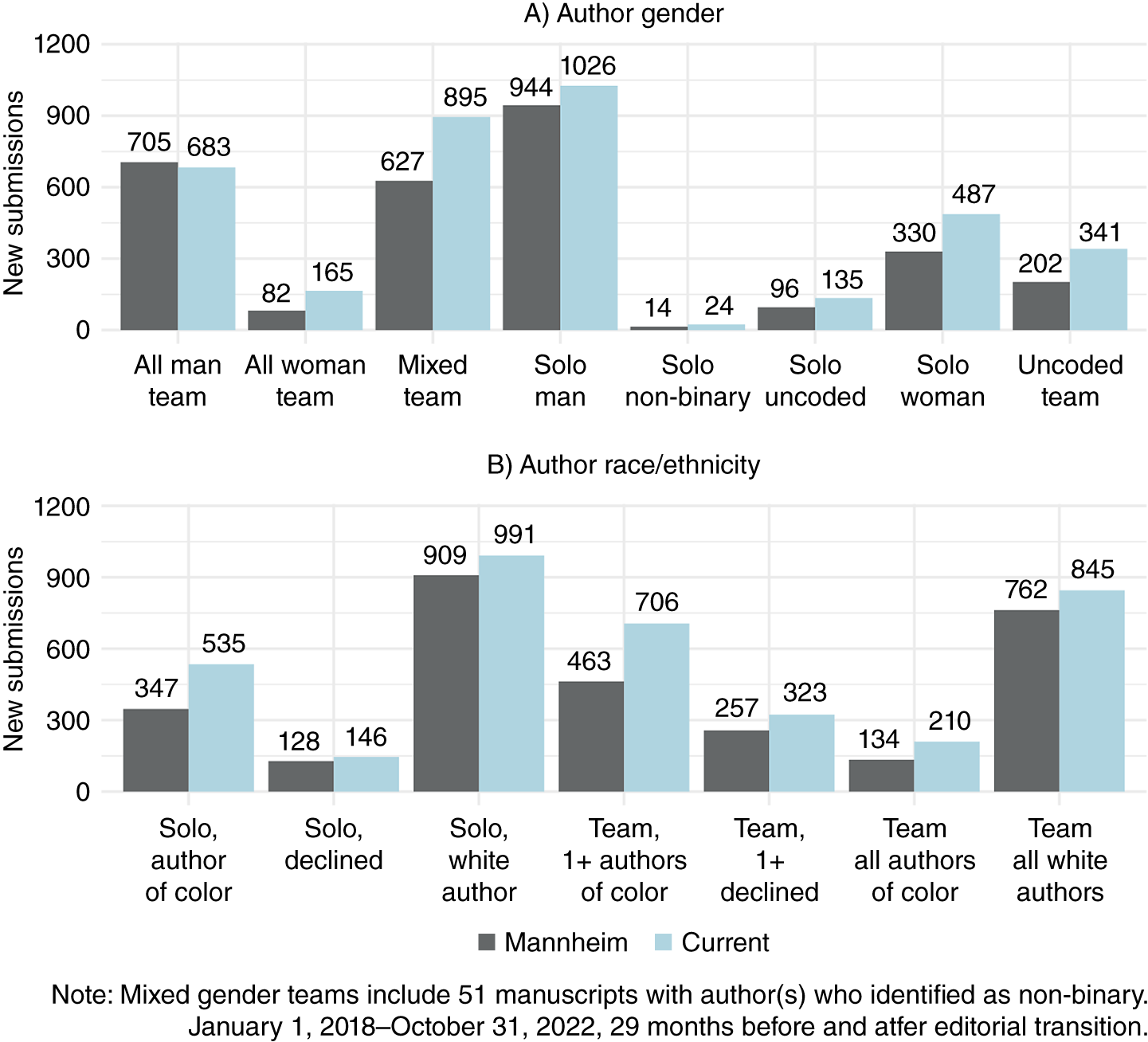

Second, gender may have had conflicting implications for new submissions. On the one hand, during the early months of the pandemic, preliminary evidence suggested that women’s research was more negatively affected than men’s by the health crisis and childcare and school closures (Bender et al. Reference Bender, Brown, Kasitz and Vega2022; Breuning et al. Reference Breuning, Fattore, Ramos and Scalera2021; Deryugina, Shurchkov, and Stearns Reference Deryugina, Shurchkov and Stearns2021; Kwon, Yun, and Kang Reference Kwon, Yun and Kang2023; Squazzoni et al. Reference Squazzoni, Bravo, Grimaldo, García-Costa, Farjam and Mehmani2021). On the other hand, however, women are more likely than men to study gender and politics (Key and Sumner Reference Key and Sumner2019; Maliniak et al. Reference Maliniak, Oakes, Peterson and Tierney2008), and our interest in publishing work on gender may have prompted more women to submit their work to the APSR than under previous editorial teams. Figure 3 (panel A) plots the number of new submissions by authors’ self-reported gender in the 29 months before and after the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic and the editorial transition.Footnote 6 Author gender is listed as “uncoded” when one or more authors decline to self-identify their gender. New submissions increased across all author gender classifications except new submissions by teams of men, which decreased by 3.1%. Nonetheless, teams of men remain the third most common author type of new submissions to the APSR, after solo men and mixed-gender teams. New submissions to the APSR do not seem to reflect narratives about gendered effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 7 Although we cannot know for certain, this suggests that our team’s expressed interest in publishing work on gender may have prompted more women to submit their work to the APSR even as the gendered effects of the pandemic may have made it more difficult for them to do so.

…our team’s expressed interest in publishing work on gender may have prompted more women to submit their work to the APSR even as the gendered effects of the pandemic may have made it more difficult for them to do so.

Figure 3 New Submissions by Author Gender and Race/Ethnicity, 2018–2022

Third, we considered patterns in new submissions by race or ethnicity. The health effects of the pandemic in the United States, where a majority of new APSR submissions originate, were concentrated disproportionately in communities of color (Mude et al. Reference Mude, Oguoma, Nyanhanda, Mwanri and Njue2021). In addition, protests following George Floyd’s murder in May 2020 may have affected the research output of Black scholars and other scholars of color (Simien and Wallace Reference Simien and Wallace2022). Simultaneously, our stated interest in publishing more work on race and ethnicity may have attracted more new submissions by scholars of color, who are more likely to work in this area. Although new submissions by all author groups increased after the editorial transition, the largest proportional increases were from individual authors of color (i.e., 535, a 54.2% increase) and author teams with a least one scholar of color (i.e., 706, a 52.5% increase) (see figure 3, panel B).

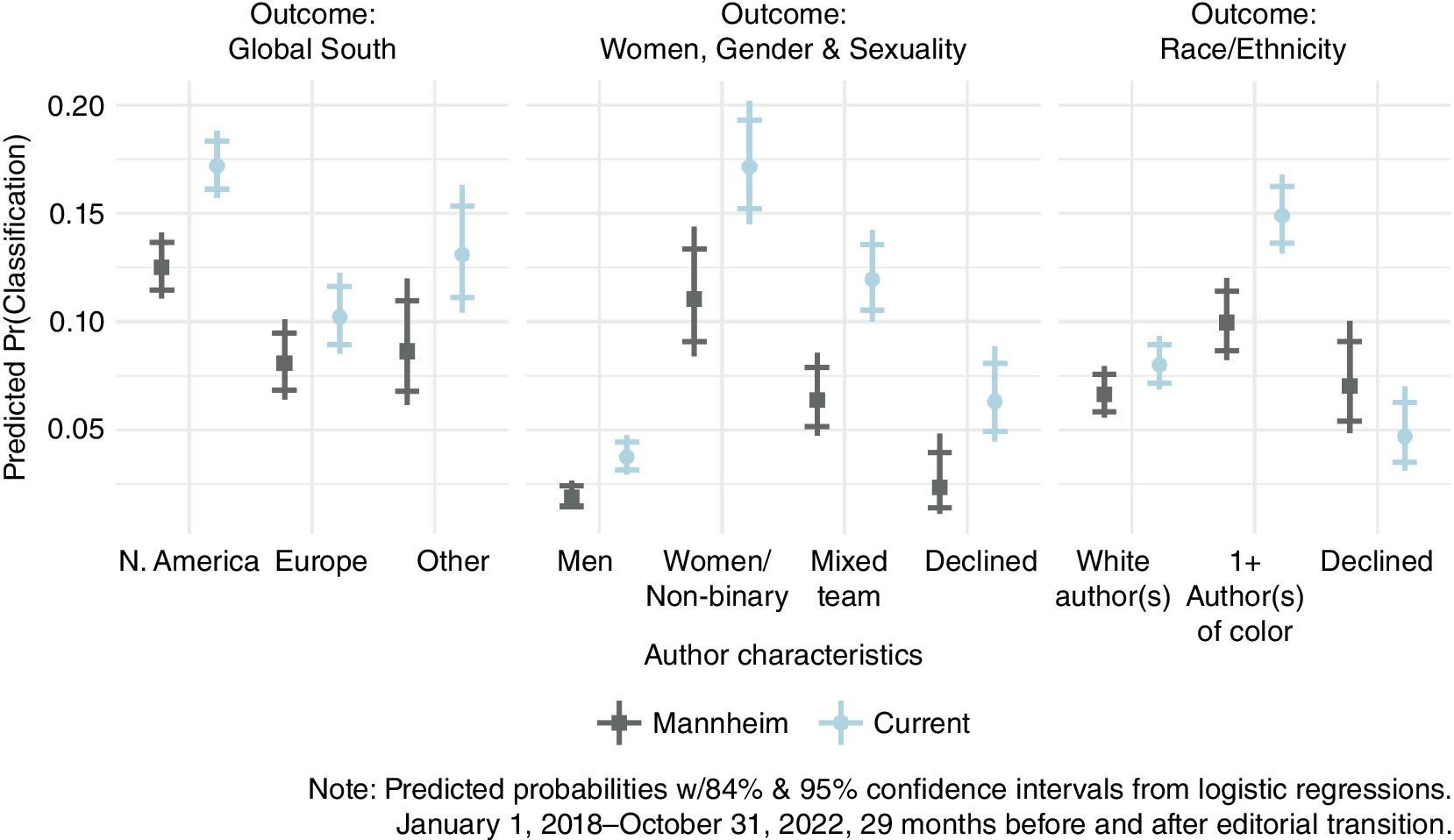

Fourth, we have suggested that our editorial team’s call for greater substantive diversity generally is associated with and may explain increases in representational diversity among submitting authors. To assess this argument, we regressed manuscripts’ substantive classifications (i.e., Global South; Women or Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity; and Race/Ethnicity) on the related author characteristic by editorial team. Figure 4 plots the predicted probabilities based on these logistic regressions.Footnote 8 Across all known author characteristics, new submissions under our team are more likely to fall under one of the substantive topics we encouraged than they were under the previous team. Although manuscripts by corresponding authors outside of North America and Europe are more likely to be about politics in the Global South under our team than the previous team, North American corresponding authors nevertheless are the most likely to classify their manuscripts this way. Women or non-binary authors or mixed-gender teams also were more likely to classify their submissions as being about women, gender, and/or sexuality and politics after June 2020. When at least one author identifies as a scholar of color, manuscripts also are more likely to address race or ethnicity and politics, particularly under our team.

Figure 4 Predicted Classification by Author Characteristics

THE REVIEW PROCESS

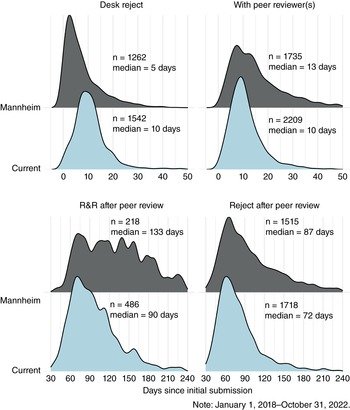

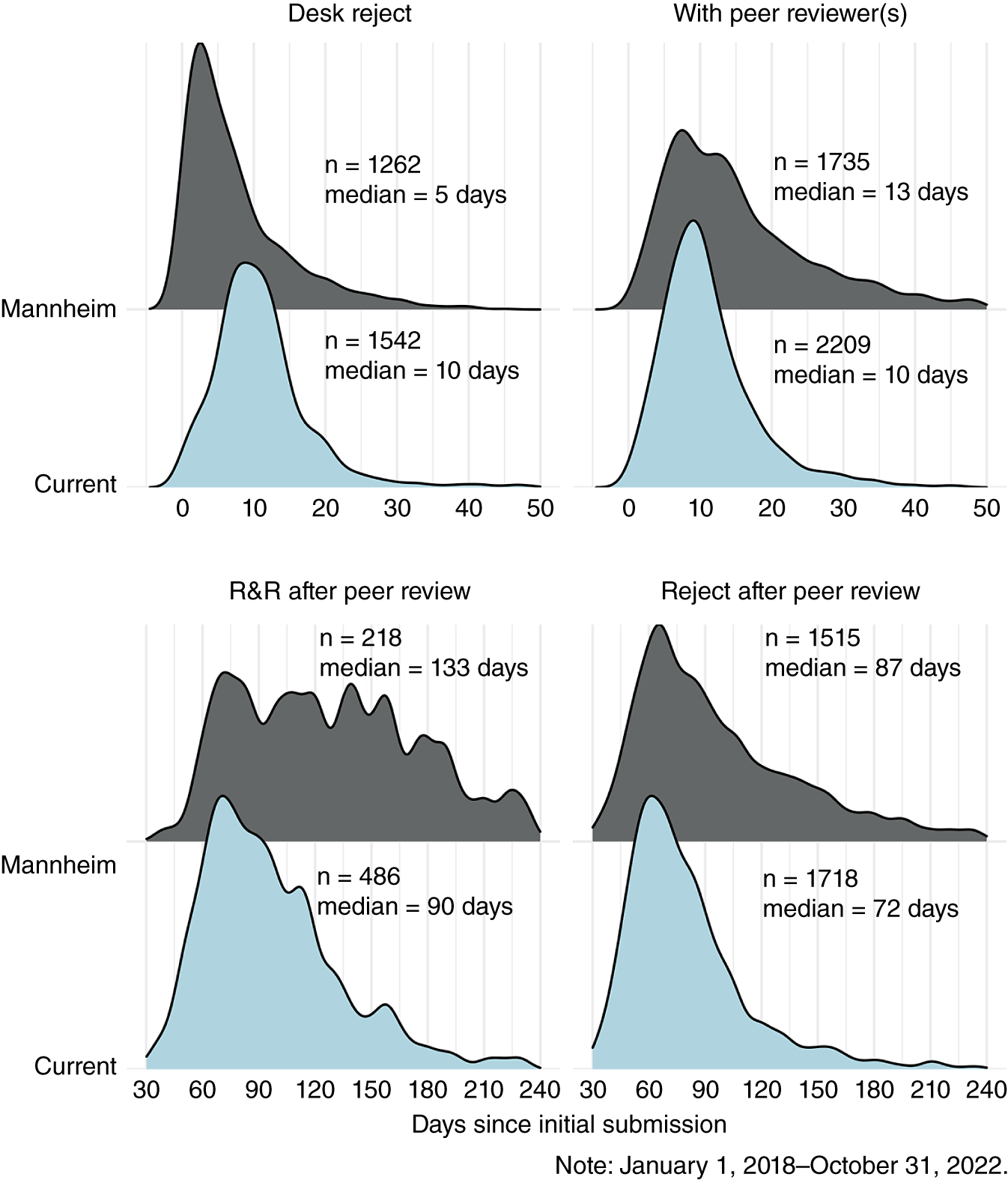

The COVID-19 pandemic affected not only scholarly output and journal submissions but also peer-review processes (Goodman Reference Goodman2022). Like authors, editors and peer reviewers also experienced pandemic-related disruptions. We disaggregate turnaround times to provide insight into the pandemic’s impact on peer review at the APSR (figure 5). Editorial team practices determine the time from submission to when a new manuscript is desk rejected or sent out for peer review. Our median time to desk reject (10 days) is double that of the previous team’s (5 days), in part because we require at least two editors to agree on all desk-reject decisions. Our team needs a similar median number of days to invite peer reviewers. Our team’s median turnaround times for decisions on new manuscripts after peer review were about two weeks sooner for rejections and about six weeks sooner for invitations to revise and resubmit compared to the previous team’s. Our team is unusual in that it is relatively large and uses a collaborative, non-hierarchical model (The Editors 2021). Although we might expect such a model would slow down the editorial process, the evidence suggests that our large team and collaborative and collective approach may have helped us maintain timely decision times and manage pandemic disruptions experienced by members of our team.

Figure 5 Initial Review Decision Turnaround Times

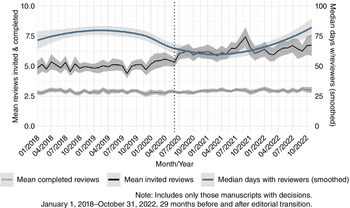

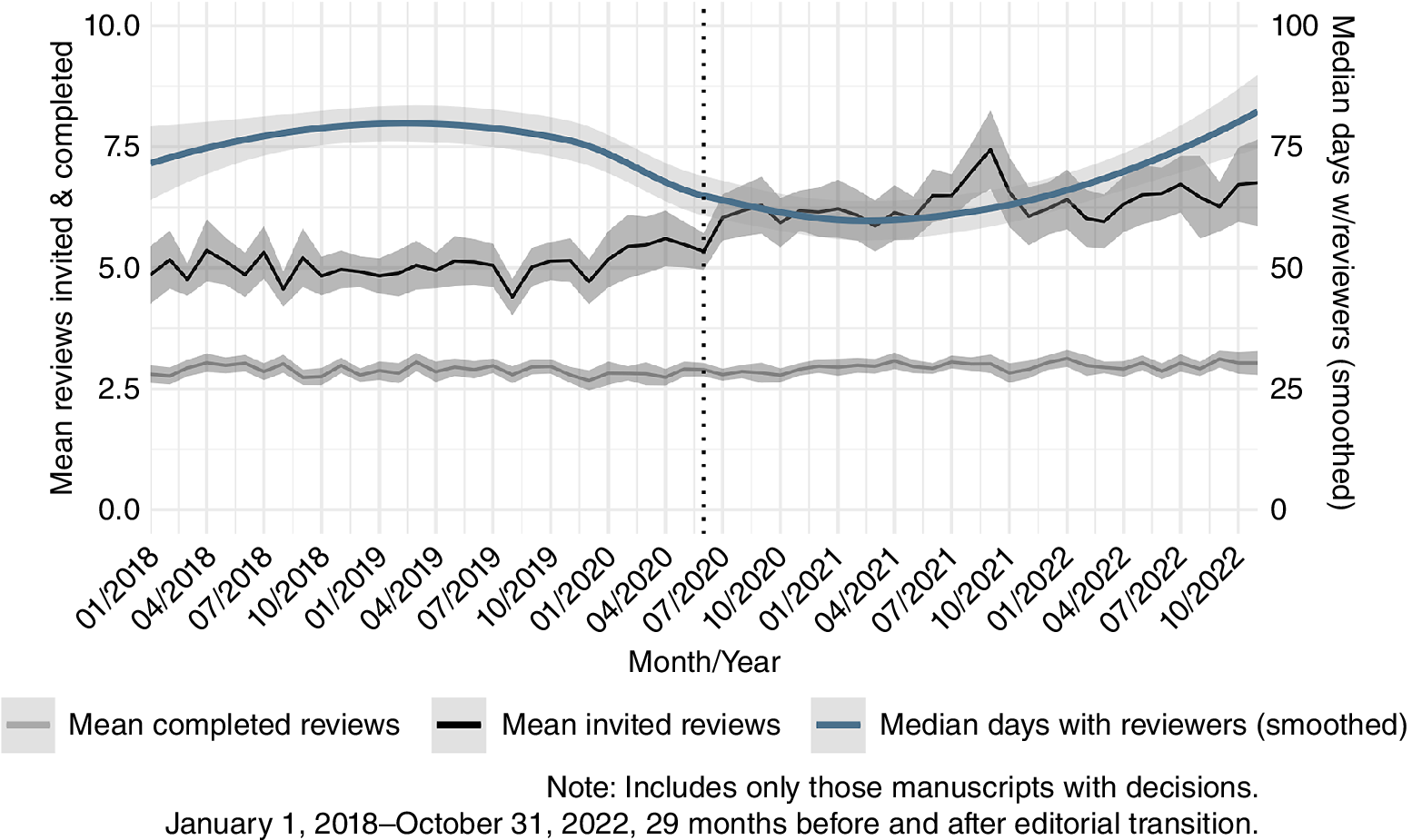

In addition to our team’s size and collaborative model, we differ in our approach to reviewer invitations, which also may explain the relative quickness of our decision times after review. During the period analyzed herein, both teams based their decisions on a similar average number of reviews (i.e., Mannheim=2.9, Current=3 reviews/decision). Our team was not faster because we relied on fewer reviewer reports per manuscript. Instead, our team invited, on average, 6.3 reviewers per manuscript, whereas the Mannheim team invited an average of 5.1. This difference could be due to initially inviting more reviewers or inviting additional reviewers sooner when existing invitations are declined or reviews are overdue. As a result, under our team, reviewers took a median of 64 days to complete their reviews, compared to 75 days in the final two and a half years of the Mannheim team (figure 6).Footnote 9

Figure 6 Invited Reviewers and Reviews per Manuscript and Days with Reviewers, 2018–2022

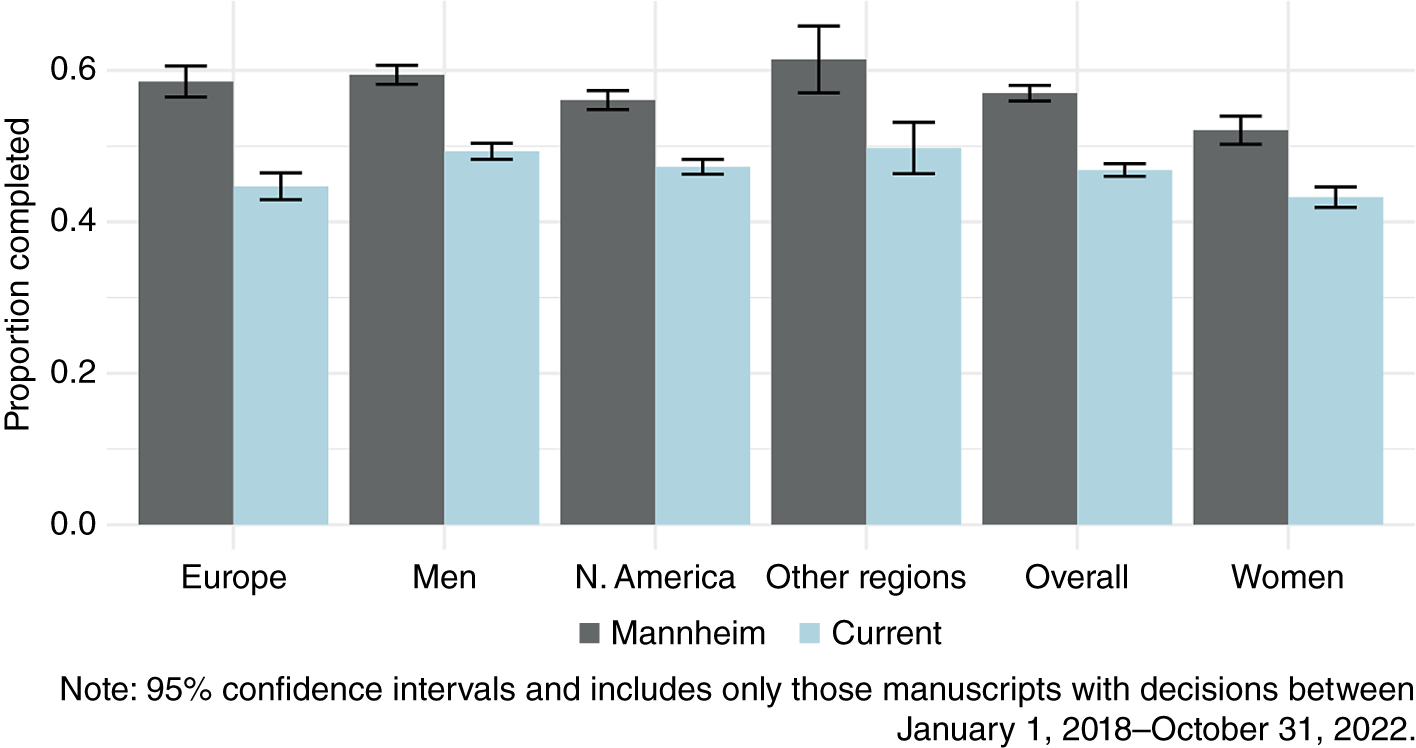

Finally, Goodman (Reference Goodman2022) observed that the gendered effects of the COVID-19 pandemic also extend to peer review, and we provide modest insights into reviewer experiences by gender and global region of residence. We used a tool that assigns probable binary gender based on first names and their association with gender identities in millions of social media profiles to code the probable binary gender of reviewers (Demografix ApS 2022).Footnote 10 Our reviewer database also includes the reviewer’s country of residence. The proportion of invited reviewers who ultimately completed a review by the time of an editorial decision decreased across the board and in similar magnitudes for all reviewers and reviewer characteristics in the 29 months after June 2020 compared to the previous 29 months (figure 7). Our reviewers were less likely to complete an invited review during our tenure than before and we needed to invite more reviewers to have the same number of reviews per manuscript for our decisions. However, we suspect that editors at smaller journals, which tend to have more difficulty securing reviewers in general, may have had different experiences.

Figure 7 Proportion of Invited Reviews Completed, 2018–2022

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Based on these patterns, we offer tentative conclusions. The timing of the editorial transition and our public commitments to broaden the reach of the journal may help to explain why new submissions to the APSR increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our commitment to substantive diversity may have incentivized the submission of articles about race and ethnicity and gender and sexuality in ways that moderated—or even worked against—some of the pandemic-related challenges to productivity faced by women and people of color, thus contributing to greater representational diversity among submitting authors. In our experience, reviewers were less likely to complete reviews during the first years of the pandemic, but by inviting more reviewers per manuscript, our team was able to reduce overall review times. This strategy may not work as well for smaller journals that already struggle to secure reviews.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our co-editors for feedback as well as APSR managing editor, Dragana Svraka, for her contributions to our team’s work. Thomas Vargas contributed to the data-cleaning code.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MYPI19.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096523001099.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.