We report a 78-year-old white male with a history of non-melanoma skin cancer who presented with a 2-month history of fatigue, worsening right-sided weakness and paresthesia, and urinary incontinence. Examination revealed weakness in the right hand and lower extremity (MRC 0/5), decreased sensation in the latter, and a T4 sensory level. Reflexes were absent in the right lower extremity, Babinski sign was present on the left, and rectal tone was absent.

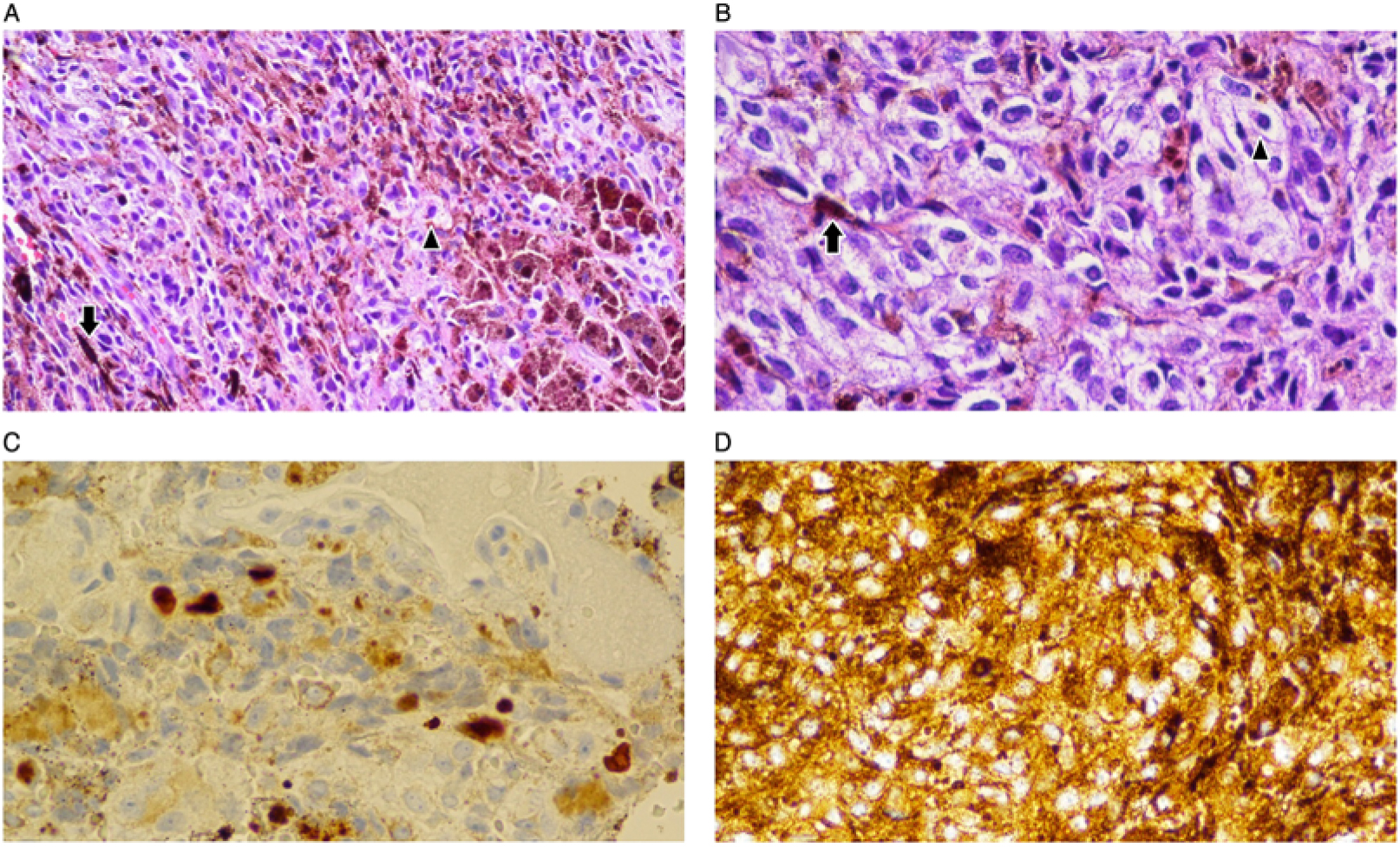

Neuroimaging showed a contrast-enhancing C7 intramedullary lesion with associated hemorrhage and surrounding edema (Figure 1). Preliminary differential diagnoses included metastatic versus primary spinal cord melanoma, melanocytoma, intermediate-grade melanocytic tumor, melanotic schwannoma, and common intramedullary tumors such as ependymoma and astrocytoma. The patient underwent an intradural tumor resection via C6–T1 laminectomy. Intraoperatively, the lesion was soft and black with an intratumoral hematoma. Histologic examination revealed diffuse proliferation of poorly nested epithelioid cells with severe anisonucleosis, prominent nucleoli, and occasional mitoses (Figure 2). Additional work-up with whole-body positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT), skin/ocular examinations, and upper/lower GI endoscopies were unremarkable, leading to diagnosis of primary spinal cord melanoma. He did not receive adjuvant radiation or systemic therapy. At 18-month follow-up, he has remained without any clinical evidence of disease.

Figure 1: Spine MRI. Sagittal T1 (A), post-contrast sagittal T1 (B), sagittal T2 (C), and axial T2-FFE (D) show an enhancing intramedullary lesion located at the C7 level associated with cord hemorrhage and surrounding non-enhancing signal changes extending from C3 to T3. Sagittal DWI (E) and sagittal ADC (F) reveal intralesional diffusion restriction suggestive of hypercellularity.

Figure 2: Variable histology of the lesion. (A and B) Hematoxylin and eosin stain (50X and 100X magnification, respectively) showing neoplastic epithelioid cells (arrowheads) with frequent melanin pigmentation (full arrows). (C) Ki-67 immunoperoxidase technique confirms a proliferation index of 10% or more in the tumor (nuclear immunopositivity), strongly supporting diagnosis of melanoma over melanocytoma. (D) Tumor cells expressing HMB-45, a cytoplasmic melanoma marker (immunoperoxidase, DAB).

Primary CNS melanocytic neoplasms such as melanotic schwannoma, meningeal melanocytoma, and blue nevus of the CNS comprise 1% of all melanoma cases.Reference Farrokh, Fransen and Faverly1 Primary spinal cord melanomas are even rarer; to our knowledge, fewer than 70 cases have been reported. Most spinal melanomas are metastatic from the skin, uvea, or vaginal or gastrointestinal mucosa; primary lesions can originate in the meninges or spinal parenchyma.Reference Ganiüsmen, Özer, Mete, Özdemir and Bayol2 They occur most often in the fifth decade of life and appear most commonly in the thoracic region of the spinal cord.Reference Kim, Yoon and Shin3 A presenting symptom is typically back or neck pain accompanied by progressive, asymmetric myelopathy. Diagnosis requires absence of other CNS tumors, lack of extra-CNS lesions, and pathological confirmation.Reference Hayward4 Histologically, melanoma is characterized by large, pleomorphic epithelioid or spindled cells with irregular nuclei, necrosis, and high mitotic index. Positive staining for HMB-45 and S100 protein is supportive, and markers such as vimentin, neuroendocrine markers, or EMA can help rule out other pigmented tumors.Reference Ruelle, Tunesi and Andrioli5 MRI imaging features T1 hyperintensity and T2 iso/hypointensity with subtle contrast enhancement.Reference Farrokh, Fransen and Faverly1

There is little data on management and prognosis of primary spinal cord melanoma. Generally, surgical treatment with resection is elected. The benefits of adjuvant chemo and/or radiotherapy are unclear. Some studies credit a multidisciplinary approach involving chemo and radiotherapy, Reference Ganiüsmen, Özer, Mete, Özdemir and Bayol2 whereas others demonstrate no survival benefit, but possible decrease in risk of metastasis.Reference Zhang, Liu and Xiang6 Survival outcomes vary dramatically from 3 months to 21 years, and late recurrences have been reported.Reference Fuld, Speck and Harris7 According to a retrospective study, the 12-month survival was 89.6% and the 72-month survival was 39.6%.Reference Zhang, Liu and Xiang6

This report underlines the importance of a comprehensive diagnostic approach involving imaging with spine MRI, whole-body CT and PET, detailed histopathological examination, and thorough gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic, dermatologic, and gynecologic evaluation to determine whether the melanoma is metastatic to the spine or primary spinal melanoma. This distinction is of paramount importance as primary lesions are associated with better outcomes following early surgical intervention and, controversially, adjuvant chemoradiotherapy.

Disclosure

AER reports personal fees from Globus Medical, Inc. and Stryker Corporation outside the submitted work. All other authors report no disclosures.

Statement of authorship

RC: chart and literature review, and drafting manuscript.

FAN: content design, drafting, and revising manuscript.

KAH: case report supervision and revising manuscript.

AER: case report supervision and revising manuscript.

ALS: case report supervision and revising manuscript.