Introduction

Studies have identified farmer-herder conflict in West Africa as a perpetual characteristic of livelihood (Tonah Reference Tonah2006) due to the unequal distribution of scarce resources between farmers and herders (Wallensteen & Axell Reference Wallensteen and Axell1994; Tonah Reference Tonah2000). In the West African literature on farmer-herder conflict, the herders are usually the pastoralists who have migrated from the Sahelian and the Sudan Savanna regions due to drought, poor environmental conditions resulting in small crop yields, and/or poor conditions for animal husbandry (Kuusaana & Bukari Reference Kuusaana and Bukari2015). The common causes of farmer-herder conflict include lack of access to land, human sharing of water points with animals, lack of coordination of herding and farming systems within a community, and the absence of demarcated herding zones linking the ranches to herding areas through cattle trails (Kuusaana & Bukari Reference Kuusaana and Bukari2015; Adesoji & Alao Reference Adesoji and Alao2009; Okello et al. Reference Okello, Akello, Tukamuhabwa, Odong, Adriko, Ochwo-Ssemakula and Deom2014). Although these issues highlight the causes of conflict in simple terms, practically, the causes can be very complex; farmer-herder conflict results from a combination of factors that are difficult to disentangle to allow for peacebuilding mechanisms to be applied.

So far, much of the emphasis on farmer-herder conflict resolution measures in Ghana has been on government initiatives. Azeez Olaniyan et al. (Reference Olaniyan, Francis and Okeke-Uzodike2015:1–2) have observed that the phenomenon of farmer-herder conflict across West Africa has prompted management strategies by several governments across the subcontinent. One conflict resolution mechanism has been the policy of expulsion, which the Ghanaian state adopted as a response to incessant conflict between the settled agriculturalists and migrating Fulani herders. Olaniyan (Reference Olaniyan2015:1–2) further discussed the dilemma confronting the Ghanaian state in its assessment of the Fulani case, recognizing the role of local government in resolving the conflict. Sebastian Paalo (Reference Paalo2020:1–3) examined the two most relevant conflict management and resolution approaches adopted by the government of Ghana, namely herder expulsion and mediation. He found that the recurrence of the Agogo conflicts and hence the inefficacious nature of the conflict management and conflict resolution mechanisms can be attributed to a complex web of politics of belonging/autochthony/identity, partisanship and political interference, and a low level of political commitment, coupled with the dilemmas of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) agreements. Beyond Ghana, Tor Benjaminsen and Boubacar Ba (Reference Benjaminsen and Ba2019) blame state institutions and political actors for contributing to the escalation of farmer-herder conflicts in Mali. Mark Moritz (Reference Moritz2006) reveals how state actors favor farmers in conflict resolution processes in Cameroon. Studies have overemphasized the role of government in addressing the farmer-herder conflict and management, with little attention given to the role of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) (see Fatile & Adewale Reference Fatile and Adekanbi2012).

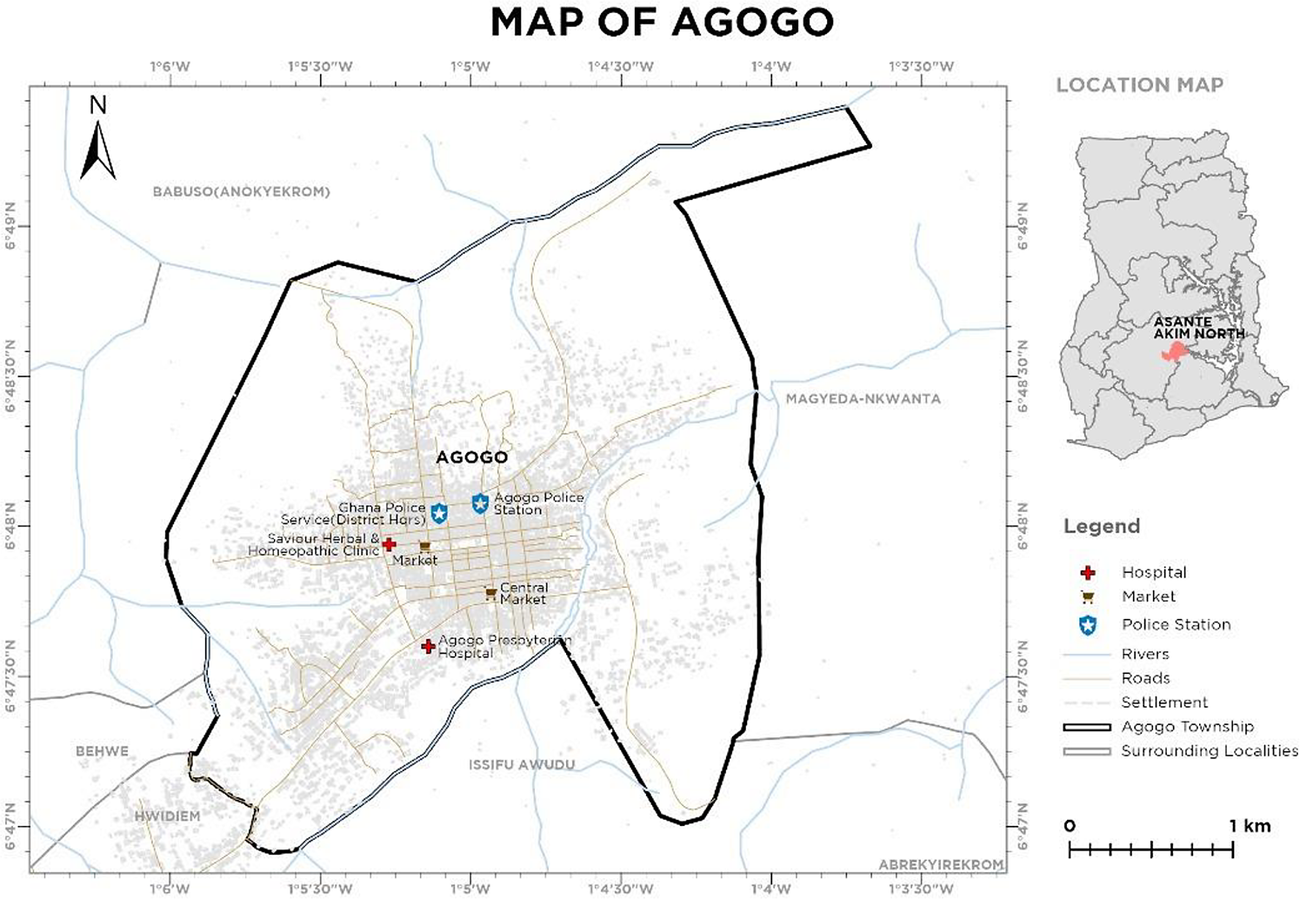

This article fills this gap by examining the role of Agogo and Fulani associations, which are community-based organizations, in addressing and managing farmer-herder conflict in the Agogo Traditional Area (ATA) in the Ashanti Region of Ghana (see Figure 1). Using the resource mobilization theory, the article unravels the functions and mobilization strategies of five associations that have engaged to a significant degree in the farmer-herder conflict and peace processes in Agogo. I draw on a triangulation of qualitative methods, including in-depth interviews, observations, and focus group discussions. This article simultaneously contributes to the ongoing debate on the involvement of CSOs in managing conflict and resource mobilization as well as farmer-herder conflict studies. Owing to the unique characteristics of the causes of the farmer-herder conflict in Agogo, the article argues for the formation and/or revitalization of community-based groups with in-depth knowledge of the cultural context. Such groups are often able to change the dominant narrative, namely, the claiming of land by both farmers and herders, as they mobilize support and power against each other on one hand and against the traditional authorities on the other. I have organized the article into the following sections: a review of literature on the role of CSOs in conflict and peace processes; the methods used; causes of the conflict; the background and role of the associations in managing the conflict in Agogo Traditional Area; and a concluding section.

Figure 1. Map of Agogo

The Agogo Traditional Area is somewhat independent, or quasi-autonomous, with the paramount chief and the traditional council controlling the affairs of the district and wielding power over traditional lands, but it is still subject to the sovereign power of the nation state. This area was selected for this study because of the major incidence of conflict, recording more than twelve deaths, sixteen injuries, and three hundred reported incidents of crop damage between 2009 and 2013 (Bukari et al. Reference Bukari, Sow and Scheffran2018). Farmer-herder conflicts, which are a common feature of this community, tend to come to a head between the months of December and March when the weather is dry. The cattle thrive well in ATA, and that explains the influx of herders and their animals. The chief farmer described the fertile nature of the Agogo land:

The Agogo land is very fertile for producing food crops; and a cow produces more offspring because of the particular breed of grass that the land produces. Because the land is fertile, when they bring their cattle, they do not want to go to any other community; they prefer Agogo. Over here in Agogo, it is always green because of the river Afram, Kowre and Egya among others. These rivers also act as a source of drinking water for the cattle.Footnote 1

The Role of Civil Society Organizations in Conflict and Peace Processes

Conflicts may arise internally between various identity groups or regionally across borders, caused by factors such as ethnicity, lack of or inadequate resources, economics, religious or political marginalization, and injustice (Waldman Reference Waldman2009:3). Robert and Jeanette Lauer (Reference Lauer and Lauer2013) have posited that conflicts arise from the “division among people over class, religious, language or gender issues.” Eno Ekong (Reference Ekong2003) explained conflict as a “social interaction” resulting from competition over “scarce reward,” which informs the decision to overpower and annihilate competitors (Oyeniyi Reference Oyeniyi2011). John McEnery (Reference McEnery1985) views conflict as overt coercive interactions of contending collectivities. The simple underpinnings of these causes of conflict ignore the complexities of conflicts which usually appear when conflict processes are studied qualitatively. This article goes beyond the enumeration of factors causing conflict to delve into the complex causes that have led to farmer-herder conflict in Agogo. The case of the Agogo conflict is unique in the sense that: there are five community-based organizations, namely, the Agogo Community Association (hereafter ACA), the Agogo Worldwide Association (AWA), the Agogo Youth Association (AYA), the Suudu-baaba Association of Fulani in Ghana (used interchangeably with Fulani Association, or FAG) and the Fulani Youth Association known as the Better For Fulbe In Ghana (used interchangeably with Fulani Youth Association, FYA), mobilized along ethnic lines that seek to further the interests of their members, while hoping that their actions might also bring peace.

There is no unanimous agreement on what constitutes a CSO. An attempt to shift the CSO discussions from the typical European concept to a more flexible concept to describe the Agogo context makes the term even more complicated. Here I adopt the Economic, Social and Cultural Council (ECOSOCC) of the African Union’s description of CSOs:

[CSOs may be] social groups, professional groups, NGOs, community-based organizations (CBOs), voluntary organizations; cultural organizations as well as social and professional organizations in the African Diaspora and cultural groups.Footnote 2

This definition is more comprehensive and accommodates the dominant associational life of West African migrants. These could include ethnic-based associations, faith-based organizations that could be private, voluntary, non-profit oriented, at least partly independent, or autonomous of the state; they might be pursuing a common interest, protecting a common value, or advocating a common cause (Nasr Reference Nasr2005:9; Ekiyor Reference Ekiyor2008:1). Although not all CSOs have an interest in peacebuilding, it is important to also recognize that some do have conflict resolution and peacebuilding as their core mandates. Examples from other conflict zones in Ghana demonstrate that the role of CSOs is often critical in resolving conflict. Abdul Karim Issifu (Reference Issifu2017:6) summarizes:

Many of the conflicts in Ghana have often had to involve the mediation efforts of locally based CSOs to end them since factions often perceive the government as bias. In cases where the CSOs intervened, stability prevailed. Parties in a conflict often see CSOs as neutral and trustworthy compared to the government.

Trust is a key element in mobilizing grassroot support. According to Emmanuel Bombande (Reference Bombande and Heemskerk2005:35), CSOs have the distinctive ability to build trust among community members through dialogue. The CSOs have this trust-building advantage because governments usually are not trusted by the community (Issifu Reference Issifu2017:6). The trust CSOs build within the community is an asset in creating and ensuring sustainable peace. Despite the unique position of CSOs, some researchers (e.g., Agyeman Reference Agyeman2008; Issifu Reference Issifu2017) have argued that the foreign and international nature of such organizations has sometimes prevented them from accomplishing any concrete conflict resolution within the communities. This is because most of these foreign CSOs do not have a knowledge of the cultural context and the dynamics of the conflict; therefore, they are unable to provide appropriate and sustainable context-specific solutions for terminating the conflict (Agyeman Reference Agyeman2008). For example, “the Bawku conflict in Ghana which is a conflict over belongingness and access to land witnessed numerous involvements of local, international and foreign NGOs in its resolution. Meanwhile, the conflict is yet to see a termination of violence and peacebuilding” (Issifu Reference Issifu2017:6–7). Based on these challenges, the best approach is to engage local actors and to use local values, including community/ethnic-based organizations, to resolve conflicts at the local level (Agyeman Reference Agyeman2008). Taking these things into consideration, this article explores how community-based organizations can employ the resources of the farmers and herders in the form of values, knowledge, and funds to manage the conflict in Agogo.

According to resource mobilization theory, society and culture are likely to change as a result of development in economic growth, war, or political upheavals (Castles Reference Castles2001). However, the mechanisms are completely different in some instances, with a particular organization or event generating the resource mobilization to pursue a common course of action. The continued clashes between nomadic pastoralists and farmers in West Africa has generated concerns around the significant role played by CSOs in resolving conflict. The resource mobilization theory explains the rational engagement by organizations that engage in some form of protest, mobilization, or political behavior in a general sense (Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg1989). Such organizations are triggered by the actors’ ability to mobilize resources for effectual participation (Tilly Reference Tilly1978). Among the various functions of CSOs is to “mobilize numbers” with the aim of changing government policies or dominant narratives by countervailing power against incumbents with a privileged position in the decision-making network (McCarthy & Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977). John Paul Lederach (Reference Lederach1997) argues that the contribution of CSOs (which he describes as meso-level organizations) helps with peace building among the indigenes by granting ownership and access to the relevant parties. Emma Elfversson (Reference Elfversson2016), in analyzing peace processes in the Kerio valley, illustrated the prominent role of non-state actors in ensuring that communities affected by conflict were able to reach mutually acceptable peace agreements through the provision of security and basic services. Others have also enumerated the positive contribution of CSOs to peacebuilding; these organizations provide their members with information, they monitor developments, and they provide early warning of conflict that can erupt into crises (USIP 2010). These organizations have the ability to bring their members into dialogue with their competitors. They can also induce their members to get involved in long-term reconciliation efforts (Rupesinghe & Anderlini Reference Rupesinghe and Anderlini1998:70). By working directly with their members, who are usually part of the conflict and peace processes on the ground, they are able to assess the situation more effectively than the external actors (Rupesinghe & Anderlini Reference Rupesinghe and Anderlini1998). Gerald Ezirim (Reference Ezirim and Ikejiani-Clark2009) argues that CSOs are well situated to engineer peace negotiation processes because they are able to mobilize support for such processes.

The resources of the organizations can be either tangible assets, such as funding, or intangible assets, such as the commitment of participants (Freeman Reference Freeman1979), or both simultaneously. Bob Edwards and John McCarthy also identify various types of resources generated by CSOs: moral resources, such as ownership and access, cultural resources, including tactical repertoires and strategic know-how, social-organizational resources, including organization infrastructures, networks, and organizational structures, human resources, such as the labor and experience of activities, and material resources such as money and office space (Reference Edwards, McCarthy, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004:125–28).

Despite the fact that they play an important role in conflict situations, CSOs do face challenges which may hinder the peace process. CSOs sometimes undercut sound conflict management due to insufficient funds; they may lack knowledge of the cultural context, or they may lack accountability and transparency, for example, allowing others to purchase weapons to fuel the conflict (e.g., Harbeson Reference Harbeson1994; Annan Reference Annan2013; Issifu Reference Issifu2017).

All the criticism notwithstanding, CSOs still can play an important role in promoting peace and managing conflict. However, these contributions have not been previously documented in the Agogo conflict between farmers and herders.

Research methods

I rely on interviews and focus group discussions conducted in Agogo to explore how CSOs have approached the farmer-herder conflict. In Agogo, the Twi-speaking Akans are the dominant ethnic group in the area, but there are also migrant settlers mostly from the Northern and Volta regions in the area as well as Fulani herders. The indigenes are mostly Christians, while the Fulani herders are Muslims. Agogo had a population of 69,186 people according to the 2010 census (Ghana Statistical Service 2013). The rural dwellers constitute 53.5 percent of the inhabitants, while the urban population is approximately 46.5 percent. The main occupation of the people of the Agogo Traditional Area is farming, which employs about 73 percent of the labor force. This was confirmed by a representative of the Traditional Council: “Agogo is a small farming community, the great majority of the people in Agogo are farmers.”Footnote 3 The people of Agogo practice a hybrid system of land tenure that combines elements of both the customary and statutory land tenure systems (Ubink & Quan Reference Ubink and Quan2008:198–213). About 70 percent of the land is under the customary land tenure system, which is based on the existing traditions and practices of these communities, while the remaining 30 percent is entrusted lands owned under customary tenure but managed by the state or owned by the state for the benefit of the public. Land tenures are constituted in various ways, depending on the interests, namely, allodial title, freehold title, leasehold, and sharecropping (Ubink & Quan Reference Ubink and Quan2008:198–213). The chiefs, clans, sub-stools, and families hold the highest land title. The native farmers also hold usufructuary titles on the stool land.Footnote 4

Empirical evidence is derived from an in-depth understanding of how the Agogo and Fulani associations have contributed to managing the conflict in Agogo. The study was conducted from July to December 2017. Data was collected from representatives of AWA, ACA, AYA, FAG, and FYA, all of which played key roles in the community’s activities during the conflict. The in-depth interviews with the associations concentrated on the formation and motivation of the associations and their key contributions, as well as the roles they played, including specific activities they undertook to manage the conflict. There were two Focus Group Discussions (FDG), one each with the farmers and herders respectively. The qualitative questions centered on the migration history of the pastoralists, the underlying causes of the farmer-herder conflict, and the role of the associations. The interviews were mostly conducted in Twi, which is the native language of the people of the Agogo Traditional Area. The qualitative interviews and discussions were coded and later translated and transcribed into English. Based on an analysis of the interviews, the following themes emerged: the background of the associations, the causes of the conflict, and the results of the associations’ activities, such as the ban on funerals and the court ruling.

I obtained permission from the traditional leaders before entering the community. Permission was also sought from the associations before interviewing them. I have used pseudonyms to protect the identity of the participants.

Causes of Farmer-Herder Conflict in Agogo Traditional Area

The key drivers of the conflict in ATA include the non-adherence of Fulani herders to the land agreement, competing livelihoods, and competing claims of land ownership. The farmer-herder conflict is fundamentally due to the perception that the farmers and herders have incompatible goals (see Mitchell Reference Mitchell1981:17). As a result, both sides are unwilling to admit any possibilities of a peaceful co-existence, due to their individual group differences (Rubin Reference Rubin1994:5).

Competing livelihoods is a major driver of conflict in the Agogo Traditional Area. Here, both farmers and herders worry about the limited land, pasture, and water points, leading to encroachment on both sides. The farmers claim that the influx of large numbers of cattle leads to encroachment on farmlands and crop destruction. The following experiences were shared on how competing livelihoods and encroachment have fueled the farmer-herder conflict. The farmers in the FGD narrated their experience:

During the dry season, the grasses and water that the animals feed on are usually totally dried up in many parts of the country and beyond. The crux of this conflict stems from the fact that, when they herd their animals to these lands to graze, the animals freely feed on the food crops on the land of the people of Agogo and drink from water points meant for humans.Footnote 5

The farmers further stated:

We the farmers harvest the plantains in anticipation of the festival on a day prior to the celebration of the festival. There have been some instances when the animals of the herders go to eat our harvest. Just imagine what happens when one of us farmers walk in on a Fulani herder who is wrongfully feeding his animals with someone else’s farm produce. Definitely, as farmers, we try to take back what is ours or receive compensation for the damage and financial loss that has been caused.Footnote 6

Apart from the encroachment on farmlands as claimed by the farmers, the farmers also complain about the gigantic size of the animals which easily destroy their crops. The animals are described as:

very huge and large in numbers; and almost always cause a mess just by treading through the farm lands. The creeping plants and other food crops that are very close to the surface of the ground are destroyed by the animals even before they eat any of them. The financial losses caused by these animals are in tens of thousands of Ghana cedis and above (USD1000+), which is why we the farmers always try to fight back when we find the herders on our farmlands.Footnote 7

Additionally, the farmers claim that sometimes the herders set dry bushes on fire in order to facilitate the new growth of tender grass and plants for their animals. The leader of AYA explained:

The herders started the fire in their bid to burn off the “old” grass so that fresher grass could grow at a later time for their animals. The sad thing about the fire is that, it doesn’t just burn the food crops such as plantain and yam, but ends up affecting many different animals within the community.Footnote 8

On the other hand, the herders admitted to encroaching on farms, but they said that the encroachment was legal because the land was demarcated to them by the traditional council of Agogo. The herders argue that it is the farmers who have extended their farms to take over their lands, since their original location was very far away from farms. This is how the herders in an FDG explained the legality of their actions:

If the farmers are encroaching from the area which used to be a traditional area for herding as demarcated to them through the authority of the traditional council, then it means the farmers are rather encroaching. This means that our encroachment is legal, because we have documents to cover our stay in the area. So now, if those areas have not been demarcated for farming, but have been demarcated for herding animals, why are farmers then encroaching that portion of land. Once we decide to move on with our herding activities to the area that was originally demarcated for herding, then it starts the problem. We the herders of Agogo have lost not less than four thousand cows in Agogo. Sometimes, in trying to hunt for us, they [i.e., the farmers] come to our shelters and attack children and women. We have suffered because our relatives and friends have been killed as well as the animals that we have lost in the hands of farmers seeking revenge.Footnote 9

Both farmers and herders have rigid and opposing positions on the usage of the lands, and this has escalated the conflict, leading to deaths, insecurity, injury, and property destruction. The leader of the Fulani Youth Association supported the rigid and opposing positions of both parties:

Of course, the clashes must happen because the two sides are claiming one interest. The herders need water and the farmers also need water. This water issue is very essential to the conflict and will always come up between the two parties. Both parties need water to survive. If there are no alternate sources of water and demarcated areas for each group, then there will always be clashes between these groups as there is now.Footnote 10

The access and usage of land problems began in 1997, when the traditional council leased a parcel of land to the Fulani herders, with fifty years tenure and twenty-five years renewable. According to the agreement, the group of Fulani herdsmen were expected to: (a) give one live cow or bull yearly as payment of royalty; (b) build ranches to prevent crop destruction on farms and compensate farmers in the event of crop destruction; (c) if need be, they could be relocated from their present location by the approval of the traditional council; and (d) exhibit good behavior. According to the representative of the traditional council, “The only condition that has been adhered to by Fulani herders over the years is the offering of live cattle as royalty. Unfortunately, we did not monitor the total adherence of the herders to these conditions, which has been the source of conflict in ATA over the years.”Footnote 11

Apart from claiming breach of contract, the Agogo associations were ignorant about the sale of some portions of the land described above to a group of Fulani herders. The various representatives of the associations shared their views on the land agreement:

It was realized in our investigations that the chiefs had leased portions of land to a group of Fulani herders; the chiefs initially denied these allegations until we had copies of the contract. … once we got hold of the truth, they did not have much of a say. Only a few of the traditional leaders agreed with our actions. For those who had leased land to the Fulani people, they were against us. We did not allow them to have their way. All the Agogo associations mobilized our members to demonstrate and posted copies of the land agreement all over the community in order to expose the traditional council for leasing Agogo land to Fulani herders.Footnote 12

We got the impression that the traditional council was in favor of the Fulani herdsmen because of certain financial perks they were getting from them. As a result, we were not on the same page with them.Footnote 13

The Agogo Associations expressed disappointment in the traditional council, thereby weakening the trust that had been vested in traditional authorities by the community as a whole. Fergus Lyon argues that trust operates when there is confidence in other agents, despite the uncertainties and risks and the possibility for them to act opportunistically (Reference Lyon2000:664–65). Unfortunately, confidence in the traditional council had waned for all the actors. The traditional council could not effectively play its conflict resolution and mediation role, as both sides did not trust them. Traditionally, conflicts are resolved through negotiations under the leadership of the traditional council, which is made up of the chiefs and elders of the community. Instead of the traditional council, the farmers vested their trust in the Agogo associations, while the herders put their confidence in the Fulani associations. Both parties resorted to this approach in order to mobilize power against each other on one hand and against the traditional council on the other.

Generally, the resilience of the three associations, namely the Agogo Youth Association, Agogo Community Association, and Agogo Worldwide Association, is significant because the local people used them to challenge their own long-standing customs. While the farmers mistrusted the traditional council for selling out community lands to “strangers,” the Fulani herders also blamed the traditional council for not defending them as legal occupants of the parcel of land which was leased to the herders. One member of the Fulani Association (FAG) shared this experience:

Once these documents were there, and were genuine documents endorsed by the government, it meant that we the herders were right. The traditional council had taken money. We paid in cows and money and they gave documents to us and allocated a portion of land to us for animal grazing. I wondered why they were so quiet and did not defend us when their people were on our nerves [case].Footnote 14

Both farmers and herders described the silence by the council as indicative of their approval of the violence initiated by each party. One representative of the Agogo… Associations expressed their concern:

As the saying goes, silence means consent! The lack of support from the chiefs have made our fight so difficult. At a point, they were making all kinds of excuses, saying that they didn’t want to violate ECOWAS protocols by just sacking the herdsmen. But now, with all that has occurred, we can’t trust any of the herdsmen anywhere near our land. Now our main focus is just to get them off the land before even considering any other solution.Footnote 15

In defense of their use of land they had purchased, a member of the Fulani association said, “We refused to allow our herders to vacate the portion of Agogo land demarcated to them. We maintained that the 1997 land agreement given to our herders remain theirs and they have access to those lands.”Footnote 16 These two opposing claims have resulted in the Agogo conflict being described as the most notorious and protracted conflict in the history of Ghana (Paalo Reference Paalo2020).

Background and Contributions of the Associations in Promoting Peace Processes in Agogo

Membership of the associations, as indicated earlier, is based on ethnicity. Members of the Agogo Associations consist of persons of the same ethnic group who hail from the Agogo Traditional Area. On the other hand, the Fulani Associations are umbrella associations for persons of the same ethnic group living in Ghana who do not necessarily originate from the same country within the West African sub-region. Broadly, the associations contributed both cash and in-kind support for the daily running of the groups. The financial contributions were mobilized through fundraising, monthly contributions by members, and personal contributions from individuals who supported the interest of the farmers and herders.Footnote 17 Unlike the Agogo Associations, which were formed for the purpose of managing the conflict, the Fulani Associations already existed, with the agenda of helping their members integrate into Ghanaian communities. Since conflicts such as this have been a long-standing struggle in other parts of the country, the association recognizes the resolution of the Agogo farmer-herder conflict as one of their major tasks. Once the Agogo conflict emerged, the association had to organize support for their members in Agogo; this has been a major agenda of the association from 2009 to date.

The section below describes the formation and contributions of the five associations to the lives of the farmers and herders during the conflict.

Agogo Youth Association: protecting and supporting indigenous farmers to help them reclaim their land

The Agogo Youth Association has the mission of supporting development and providing key social amenities for the people of the Agogo Traditional Area. Members of the association indicated that their main concern was to support indigenous farmers in protecting themselves against attacks by the herders and to reclaim ownership of their land from the herders through non-violent means. The association has collaborated with ACA and AWA in carrying out their activities. Although the association existed prior to the conflict in 2009, it was not very active. However, through negotiations with the leaders of the community as well as the other two Agogo associations (AWA and ACA), they have mobilized themselves for operation. The notion of creating different associations was linked to the diverse resources they each brought to the conflict management table. The president of the AYA narrated how his association was formed and the kind of contribution they make toward promoting peace:

The youth are a strong pillar for success in any community. The community leaders and the two elderly associations gave us their full support. As a youth group, we understood the sensitive nature of the conflict and issues at hand, we mobilized support from within the community to avoid any sabotage. The backing of the community gave us the impetus to push ahead. We finally took off and were all over the place. From radio stations to organizing meetings and creating awareness of different platforms, people began to realize that this was becoming a movement and they needed to support us. We gained trust of the people due to this, and their trust in us was solidified when we organized demonstrations to oppose the Fulani herders for wanting to possess our lands.Footnote 18

The ability of AYA to mobilize the trust, support, and commitment of the community was a source of power that sustained the association and helped it move toward achieving its set goals. The trust that the community has invested in the AYA stems in part from the lack of trust the people have for the government and politicians (Issifu Reference Issifu2017:6). The association receives financial contributions from their members, both home and abroad, through voluntary contributions, remittances, and their monthly payments to the association. The leader of the Association explained:

Our members home and abroad sent cash to help organize these demonstrations. They provided whatever they thought was necessary to push the agenda of getting rid of the Fulani herdsmen. We also supported the group with our monthly contributions. It’s a youth organization, and a great majority of the members are still trying to get on their feet and find a stable job.Footnote 19

The activities organized by AYA were mainly demonstrations and protests to register their objection to the ongoing situation within the community. Another executive member of the association also shared this narration:

Most of the time, we led protests; we also realized that the Agogo farmers needed education on how to behave when they were approached by Fulani herders on their lands. For example, the farmers who met Fulani herders on their farms were advised not to be violent or confrontational, especially if the Fulani herder had weapons in their hands. The best thing to do was to walk away and probably report the incident to any of the leaders of the Agogo Associations. These measures have curbed the level of violence on the farmlands and have brought about more peace. They were asked to report any incidents they had with the Fulani herders.Footnote 20

The leaders of this association have been instrumental in assuming responsibilities of various forms, including organizing protests, sensitizing their constituents on how to protect themselves from attacks, and financial contributions as well as cultural resources. Through campaigns on various media platforms, the associations has made their grievances known as a means of creating public awareness and attracting public sympathy.

Agogo Community Association: playing the senior role of the Agogo association

The Agogo Community Association was formed in 1952 to ensure that the community was peaceful and to encourage development. However, with the rise of the issues with the Fulani herders in the early 2000s, the association modified its goals to include the prevention and curbing of any unwanted activity in ATA, including the atrocities caused by the Fulani herders. The leader of the association explained the functions of the group:

When the youth are asked to present a petition before the elders, they can’t make any headway, or even in some cases, the elders will not listen to them. That is the reason we came up with this association. The association is made up of elderly people living in Agogo Traditional Area. The Association serves as an intermediary between the community and all the other associations. We organize regular meetings with leaders of the various associations (including AYA and AWA) in ATA and they in turn pass on the message to their members.Footnote 21

Members of the older generation understand the values and norms of the Traditional Area. Respect for the elderly in the community is a major component of the traditions of the Agogo Traditional Area, hence the formation of this association. ACA negotiates with and passes judgment against traditional authorities, which could not have been done by the youth groups. Members of ACA claim to have the full support of AYA and AWA; they work closely with them to achieve their common goals. Additionally, one leader explained that “the AYA run errands and execute tasks for ACA and AWA.”Footnote 22

Although the ACA was already in existence and had its original set of goals, it had to adapt to the conflict situation confronting their community. It is obvious from the narration that the association acts as a big brother/sister or even as a father or mother figure in the community and toward the other associations. The symbolic nature of the organization’s position in the community seems to be a source of power or a driving force behind its existence. Similar to AYA, members of ACA also relied on the financial contribution of AWA as well as the contributions of its members. One ACA executive member highlighted some of their organized activities toward resolving the conflict:

I recommended that we use the media and other platforms to spread the message of what needed to be done. We held press conferences and also went to the neighboring villages to talk to farmers about what we were doing. We were also on television programs and almost all the radio stations in the region to create awareness and shed light on the conflict between the Agogo and Fulani herders.Footnote 23

Agogo Worldwide Association: supporting their community of origin through diaspora resources

The Agogo Worldwide Association was formed in 2003 by the Agogo diaspora, with the aim of mobilizing diaspora resources and minds for the development of ATA. The aim of AWA was to ensure coherence, consistency, and coordination of support for ATA. The leader of the association further explained the formation of the association and their functions in resolving the conflict:

Although the individual country’s diaspora associations were scattered all over Europe and North America, the emergence of the conflict in Agogo sparked the coordination of these associations into forming AWA. AWA represents one of the smallest towns in Ghana with a vibrant association, which is uncommon among diaspora associations of Ghana. Including the different chapters, AWA has about 500 members. The 2003 gala [annual meeting] was one of the most well-attended and it was the one that gave birth to AWA. Every chapter is independent, more or less, and then we have created the worldwide association to be the umbrella association.Footnote 24

The mobilization of AWA centered on the diaspora as a resource, including their financial and technical contributions during the conflict situation. AWA has five officers who manage the organization’s affairs: the president, vice president, the general secretary, the public relations officer, and the treasurer. There is also the executive board, which comprises chairpersons/presidents and their vice presidents and secretaries from all the chapters. AWA members live mainly in the U.S., with some in parts of Canada and Europe. Members, among other things, share ideas on how to manage Fulani issues within the community.

The activities of AWA are funded by members contributions, which are also used to support ACA and AYA. The leader of AWA said:

It was empathy, sympathy, and passion. We just made an appeal for funds, and people voluntarily donated. So, I visited all AWA chapters in the U.S., UK, and some other parts of Europe, and during our discussions, we told them our plans. We made an estimate of the amount of money needed, and members contributed. It was really a voluntary exercise and we touched the heart of every citizen living abroad and they felt proud for being in a position to help. That was the motivation, seeing themselves in the media and trying to help their town. Folks were excited and motivated.Footnote 25

The executives of AWA temporarily returned to Agogo to represent the Agogo community in court and to organize sensitization programs on television and on the radio on how farmers could control their temper when they were approached by Fulani herders on their lands and in the community.

Better Agenda for Fulbe in Ghana: educating herders and their families against conflict

The Fulani Youth Association is called Better Agenda for Fulbe in Ghana; it has been active since 2009 in sensitizing its members on how to conduct themselves in their dealings with the farmers. The name originated from the idea of mobilizing resources, whether tangible or intangible, for better conditions and recognition for the Fulani people in Ghana. The association was formed, among other reasons, with the aim of:

changing the narrative and to inform the Ghanaian populace that not all Fulani are herders. There is this perception that all Fulani herd cattle, but people don’t know that there are Fulanis who are also educated. We have lawyers, bankers, and people who work in many different professions; such narratives contribute to the harsh attitudes of host communities towards the herders in the country. Because of the herding profession, Ghanaians look down on us as Fulani.Footnote 26

FYA members are usually young and unemployed, but they depend on the monthly contribution of members and on the contributions from FAG. The FYA moved into the communities during the conflict to educate the herders on how to behave in their communities of work, to empower them through education on their rights, and to encourage them to educate their children. One of the executive members explained their activities in this manner:

We have been able to get some of them to register for the health insurance card, voter’s ID, and the national ID card. We have managed to encourage some of them to allow their children to attend the free basic education; at least that gives the children two opportunities of being herders and educated. The herding job is under threat and further threatens the long-term existence of the job.Footnote 27

Suudu-Baaba Association of Fulani in Ghana: giving a voice to the voiceless herders

The Suudu-Baaba Association of Fulani in Ghana became active during the peak of the conflict in Agogo in 2009, with the aim of giving a voice to the voiceless herders. The association has strong roots in the history of Ghana. The earlier Fulani settlers constructed certain popular communities in the city of Accra, including “cow lane” in Tudu, Adabraka, Nima, and Kanda. Members of the association testified that the conflict between the Fulani herders and indigenous farmers is one of the most challenging and difficult issues for the association. The leader of the association confirmed that he was nominated for the position because “of my long-term experience in working on conflict resolution with the African Union. The idea is to give me the opportunity to contribute to peacebuilding among farmers and the herders with my twenty-five years of experience.” He gained this experience from his work, which required him to help conflict-prone areas in Africa to build peace. The association is led by the president, with the assistance of the secretary general, social secretary, women’s secretary, and children’s secretary, as well as other departments with different functions. The association also engages in the following activities among the herders:

We advise our people to educate their children in the local schools, which is an opportunity provided by the government. They should make sure that their children attend those schools. We also discuss how to establish a conducive environmental situation which will be good for both parties (the farmers and the herdsmen). And that’s what we have been doing most of the time.Footnote 28

Resources for the association are mobilized along the lines of seniority, trust, expertise, experience, commitment, and funds. Importantly, both FYA and FAG have broad aims, but they both fight for the rights of their members, who are herders living in ATA. Similarly, the Fulani Associations also receive donations through personal contributions from their members and through their monthly contributions. The leader of the group further said;

It’s usually personal contributions. We appeal to individuals in order to raise funds. We also approach some opinion leaders among the herders to make some personal contributions to help promote the activities of the association. But basically, we make monthly contributions as well. In certain cases, we specify the target amount that we need and then contribute towards meeting that target to fund our activities. Some of our members who live abroad are encouraged to also donate to support our cause and we call them on board.Footnote 29

“Meet us in court or have no peace!”: The role of the Agogo and Fulani Associations in managing the conflict

Our legal advisor made us understand that the indenture issued to the herders was still be active and could not be nullified without the court’s ruling. Once we realized this, we decided to file the case in court, because only the court’s ruling could overrule the indenture. The chief and his council who were supposed to file the matter in court turned deaf ears to our appeals… we made an announcement in the town and said that until the chief takes the matter to court and expels the Fulani herders from the town, we will not let them have peace. At the time, the Fulani herders had killed about fifty people already…But the chiefs were not bothered at all by these threats.Footnote 30

The quotation above shows that the Agogo Associations, by mobilizing their resources (in the form of numbers, trust, expertise, and cash), mounted pressure against the traditional council. They demanded that the traditional council file a court case against the Fulani herders for breach of contract, however, these appeals did not yield any results. Consequently, they claimed they had to devise strategies to compel the traditional council to respond to their demands. Among the strategies were a ban on funerals and the filing of the case in the court of law. The ban on funerals lasted for over three months. The leader of the ACA explained the strategy for issuing a ban on funerals:

We became very aggressive in our approach and realized that the one thing that the chiefs were very much interested in was attending and performing funeral rites. So, all the Agogo Associations and members came together and decided to place a ban on funerals or the performance of any funeral rite. Meanwhile, against our warning, the paramount chief whose uncle had passed on decided to organize a funeral rite. We went out to the radio stations to make a public announcement and reiterated the ban we had placed on funerals; we emphasized that every single person should stay indoors and not attend the funeral of the late uncle of the paramount chief. The whole town became quiet. The paramount chief then came to the realization that what he was hoping to achieve wasn’t going to work. He had no other choice but to take the “dead body” [corpse] back to the morgue.Footnote 31

While the ban on funerals was in effect, the Agogo Associations said that they had to file the case in court because there was no practical solution emerging on the part of the traditional council. They also explained that although the ban had been successfully implemented, the traditional council was not compelled to engage with them on how best to resolve the pending issues. Through the associations, the farmers and the Agogo citizens were able to control the activities of the community, thus co-opting the role of the regular traditional rulers.

The leaders of the Agogo Associations shared their involvement in the court processes. The AWA representative said:

Through the associations, we funded the documentation of destroyed farms, injuries, and the other outcomes, which were later used as evidence in the court of justice. Although we cannot estimate all the amount involved in the processes, AWA contributed about $20,000 in support of the efforts, including the court case. AWA together with ACA supported with technical expertise and professional support to the legal team of the farmers and citizens of the traditional area.Footnote 32

One of the executive members of ACA further narrated the outcome of the court case:

On January 20, 2012, the high court issued a mandatory injunction and directed the Ashanti Regional Security Council and Regional Coordinating Council “to take immediate, decisive, efficacious and efficient action to flush out all the cattle from” Agogo Traditional Area.Footnote 33 The final verdict from the court case was that the Fulani herders had breached the contract and were therefore banned from ever setting foot on the land that belonged to the people of Agogo. Once the court ruled in our favor, we had to lift the ban. Additionally, some members of our group were involved in the business of hiring chairs and canopies for funerals, and it was impacting negatively on their businesses. Somewhere in the month of February, the ban on funerals was finally lifted.Footnote 34

While the Agogo Associations were excited and felt vindicated by the court ruling, the Fulani Associations had a contrary view on the court’s judgement. The representative of the association narrated the herders’ side of the story and the position of the Fulani associations in general:

Yes, we gave our herders technical support, advised them, and also sent some people to be part of the legal team in the court of law. But with the court’s ruling, it looks like it is one-sided. The court could not provide a cause and effect explanation, neither did they justify the judgment. Not just concentrating on the fact that the farmers are losing, the farmers are killed, the farmers are victimized—which is true—but what about the other side? The herders also have lost relatives and properties. This case needs to be revisited in a proper way. Our position as an association is to forget about the court ruling and allow the two sides to sit together and come up with solutions to resolve the issue once and for all.Footnote 35

The ban on funerals as well as the court case had consequences for both herders and farmers with regard to their livelihoods and what they valued most as culture. Through the associations, the members assumed ownership of the activities in managing the conflict. They sacrificed their time and obeyed their leaders’ instructions, trusting them throughout the processes. Funerals are a very important cultural institution among the Akans (van der Geest Reference Van der Geest2000), but for purposes of achieving the wishes of the members of the Agogo Associations, they had to temporarily do without this culturally significant activity. The herders in an FDG shared their concerns about the ban:

The willingness with which the farmers and citizens of Agogo adhered to the ban was scary; we didn’t think the traditional council could be silenced, until it actually happened. At that point we didn’t even have the courage to herd our animals as we used to.Footnote 36

The implementation of the court ruling did not happen immediately. Although security personnel were successful in evicting some of the herders and their animals, this has not been fully accomplished. But the reduction of the animals in the Agogo traditional area has restored some calmness in the area, reducing the frequency of conflict between farmers and herders. The representative of the ACA had this to say about the eviction exercise:

A security task force has implemented the 2012 court ruling by evicting thousands of cattle from ATA. Our slogan was “TOTAL EVICTION OF ALL CATTLE.” We planned and gathered all the herders and their animals in a particular location and directed their trucks to pick them up from that geographical location.Footnote 37

Conclusion

This article has examined the role of Agogo and Fulani associations in managing farmer-herder conflict in the Agogo Traditional Area in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. The farmer-herder conflict came about as a result of the competition between farmers and herders over land, pasture, and water. Both sides are unable or unwilling to perceive any peaceful co-existence, due to encroachment, competing livelihoods, and claims of land ownership. Unlike some foreign or international CSOs (see Bombande Reference Bombande and Heemskerk2005; Issifu Reference Issifu2017) that have not fared well in some conflict zones in Ghana, these local associations have played positive roles in the lives of the farmers and the herders during this conflict. One advantage the associations have is the fact that they belong to the community and understand the context of the conflict better, which has enabled them to amass support and gain the trust of their members in managing the conflict. In line with the ongoing debates (Agyeman Reference Agyeman2008), being cognizant of the root causes and understanding the community and cultural dynamics of the conflict has been a fundamental principle in managing the farmer-herder conflicts in Agogo.

Beyond the tangible resources (such as funds) which are very much highlighted in the literature (Freeman Reference Freeman1979; Edwards & McCarthy Reference Edwards, McCarthy, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004), the various associations were also endowed with indigenous knowledge which informed their formation and activities. The youth associations were distinct from the others, in that they performed most of the grassroot jobs such as demonstrations, protests, and education, while the older generation represented the associations at the decision-making level with the chiefs and traditional authorities. The demonstrations and education programs were relevant in broadening the knowledge base of both farmers and herders as well as in improving the sense of belongingness of members to their various groups. Through the activities of the associations, the farmers and herders learned how to report destruction to the appropriate authorities instead of engaging in violence. Through campaigns on various media platforms, the associations made known their grievances as a means of creating awareness and attracting public sympathy in their approach to resolve the conflict. This approach was successful for both parties, because it attracted the attention of the diaspora and others who were neither farmers nor herders but yet had a common ethnic background. These resources had a positive impact on the process of managing the conflict in the Agogo Traditional Area. The associations have been instrumental in building the trust of the farmers and herders through dialogue. Through the associations, members took ownership of the process of managing the conflict and had access to a means of controlling community activities. More specifically, the Agogo Associations mobilized local support, which allowed them to take over the administration of Agogo from the traditional council through the ban on funerals. The traditional council has a mandate to make decisions concerning the daily administration of the community. However, this role was taken over by the Agogo Associations. Instead of the traditional council, the farmers vested their trust in the Agogo Associations, while the herders put their confidence in the Fulani Associations. Similar to John Paul Lederach’s (Reference Lederach1997) explanation on the contribution of CSOs, these associations, through their activities, endowed the farmers and herders with the opportunity to take ownership of the peace process and mobilize resources for their intended goals.

This article argues that the associations played important roles in promoting peace and managing this farmer-herder conflict because they were able to produce a relatively calm situation in Agogo. Once the court ruled against the herders, a majority of them left the Agogo township with their animals. However, the call for locally- or community-based associations must be initiated with caution. The performance of the association depends on whether the association is indigenous or non-indigenous. In the case of the Agogo and Fulani Associations, the Agogo Associations had the upper hand because they have the highest land ownership as indigenes of the Agogo traditional area. The Fulani associations, conversely, are seen as strangers occupying lands of the indigenes of Agogo, even though they had acquired the land legally. This binary categorization leads to a winner-takes-all attitude instead of resolving the conflict in a more sustainable way. There is still work to be done toward creating a lasting peace, but the community organizations were able to de-escalate the situation and at least greatly reduce the violence. This study therefore demonstrates the valuable contributions that community organizations can make within their limited spheres of influence.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for the valuable comments from anonymous reviewers and the editors, Benjamin Lawrance and Kathryn Salucka, at African Studies Review. I am grateful to the executives and members of Agogo Community Association (Agogoman Mma), Agogo Worldwide Association, Agogo Youth Association, the Suudu-baaba Association of Fulani in Ghana and the Better for Fulbe In Ghana association, whose openness and support have made this project possible. Thanks to my graduate assistants, especially Francis Williams Aubyn and Maame Adwoa Nyame Sam for all the assistance including fieldwork support.

Funding

The project on which this article is based was funded by the African Peacebuilding Network (APN) Individual Research Grant of the Social Science Research Council (SSRC). The writing of the article began during my post-doctoral fellowship at the University of South Florida, under the University of Ghana- Carnegie Corporation of New York-sponsored project, Building a New Generation of Academics in Africa (BANGA-Africa).

Competing Interest

None.