Introduction

The implementation of effective interventions hinges upon clinical decisions made between patients and mental health professionals. Clinical decision making in persistent conditions differs from well-defined acute care situations in many ways. Clinical decision-making in the treatment of severe mental illness (SMI) is characterised by a focus on long-term disease management, with patients being highly knowledgeable about their illness. A high number of decisions have to be made frequently, often involving more than one service provider or informal carer (Watt, Reference Watt2000). The defining features of decision making include context (direct and indirect background variables, such as information and preferences), the actual process of decision making and its evaluation, and outcome (Entwistle & Watt, Reference Entwistle and Watt2006; Puschner et al. Reference Puschner, Steffen, Slade, Kaliniecka, Maj, Fiorillo, Munk-Jorgensen, Larsen, Egerhazi, Nemes, Rössler, Kawohl and Becker2010; Wills & Holmes-Rovner, Reference Wills and Holmes-Rovner2006).

Three of decision making styles have been proposed to characterise the degree of patient involvement in decision making: passive or paternalistic (decision is made by the staff, patient consents), shared (information is shared and decision jointly made) and active (staff informs, patient decides) (Charles et al. Reference Charles, Gafni and Whelan1997; Coulter, Reference Coulter2003). Over the past 20 years, shared decision making has been recommended as the optimal style to improve patient-orientation and quality of health care (The Lancet, 2011; Del Piccolo & Goss, Reference Del Piccolo and Goss2012). Although it has been shown that people with mental illness want to be informed about and have a say in their care (Hamann et al. Reference Hamann, Cohen, Leucht, Busch and Kissling2005; Hill & Laugharne, Reference Hill and Laugharne2006), practitioners have largely failed to adopt principles of shared decision making in their daily routine (Goss et al. Reference Goss, Moretti, Mazzi, Del Piccolo, Rimondini and Zimmermann2008; Karnieli-Miller & Eisikovits, Reference Karnieli-Miller and Eisikovits2009; Légaré et al. Reference Légaré, Ratté, Stacey, Kryworuchko, Gravel, Graham and Turcotte2010; de las Cuevas et al. Reference de las Cuevas, Rivero-Santana, Perestelo-Perez, Perez-Ramos and Serrano-Aguilar2012; Storm & Edwards, Reference Storm and Edwards2013). Furthermore, the evidence base for the impact of shared decision making on health status is limited (Joosten et al. Reference Joosten, DeFuentes-Merillas, de Weert, Sensky, van der Staak and de Jong2008), especially in mental health care (Duncan et al. Reference Duncan, Best and Hagen2010). This is a clinically important knowledge gap. Staff decision-making style can be changed, so if it impacts on patient outcome then it provides a target for potential intervention. Longitudinal studies are necessary to provide empirical data about these important clinical issues (Hölzel et al. Reference Hölzel, Kriston and Härter2013).

In summary, there is a lack of knowledge on clinical decision making and its relation to outcome in the routine treatment of people with SMI. Specifically, the process of decision-making in real-time encounters has been under-researched (Karnieli-Miller & Eisikovits, Reference Karnieli-Miller and Eisikovits2009; Kon, Reference Kon2010). This paper addresses these knowledge gaps by examining the following research questions:

-

(a) Which clinical decision making style is preferred by patients and staff?

-

(b) What are the levels of involvement and satisfaction with clinical decisions from patient and staff perspectives, and how do these change over time?

-

(c) How are these aspects of clinical decision making related to outcome?

Methods

‘Clinical Decision Making and Outcome in Routine Care for People with Severe Mental Illness’ (CEDAR) is a naturalistic prospective longitudinal observational study with bimonthly assessments during a 12-month observation period (T0–T6). The study has been registered (ISRCTN75841675) and is reported in line with the STROBE statement (von Elm et al. Reference von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke2007). The six study sites reflect the diversity across Europe in the organisation of mental health services.

Ulm, Germany (coordinating centre): The Department is responsible for the provision of mental health care in a large catchment area in rural Bavaria (population 671 000). Multidisciplinary teams (psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, nurses and occupational therapists) offer the full range of pharmacological and psychosocial interventions in inpatient, outpatient and day care clinics. The Department collaborates closely with office-based psychiatrists and psychotherapists in the area. London, UK: The site comprised three specialist community teams: early psychosis, assertive outreach and Rehabilitation and Recovery. All teams are multidisciplinary (n = 10–15), comprising clinical psychology, nursing, occupational therapy, psychiatry and social work professionals, as well as support workers and administrative staff. These teams provide a service across the London Borough of Croydon (population 330 000) as part of a range of services for adults aged 18–65, including three community mental health teams, home treatment team, community forensic team and in-patient beds. Naples, Italy: The Department includes inpatient and outpatient units and 1 day hospital. The outpatient units include specialist clinical teams for the management and treatment of psychotic disorders, mood disorders, eating disorders and obsessive–compulsive disorders. Specialist teams for early detection and management of psychoses and for cognitive and psychosocial rehabilitation are available. Debrecen, Hungary: The Department provides in- and outpatient mental health care for the city of Debrecen (population 200 000). The team is completed by an occupational therapist and a social worker professional who keeps contact with the regional rehabilitation institutions and mental homes. Aalborg, Denmark: The Psychiatry Region North includes various treatment centres, including inpatient treatment, outpatient teams and early psychosis teams. The collaborating centres in the CEDAR study were organised within Universities of Aarhus, Aalborg, Copenhagen and Southern Denmark. Others were provincial hospitals with associations to Aarhus University. Furthermore, CEDAR collaborated with office-based psychiatrist. Zurich, Switzerland: The Department takes responsibility for a defined catchment area in Zurich City of about 390 000 inhabitants. It comprises 488 beds and additionally offers specialised care in a crisis centre and centre for psychiatric rehabilitation.

Participants

The study was approved by the ethical review boards at each study site. Participants were recruited from caseloads of outpatient/community mental health services. Inclusion criteria were: adult age (18–60 years, chosen to match the age range seen by adult mental health services across the participating sites) at intake, mental disorder of any kind as main diagnosis established by case notes or staff communication using SCID criteria (First et al. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1997); presence of SMI (Threshold Assessment Grid ≥5 points (Slade et al. Reference Slade, Cahill, Kelsey, Leese, Powell and Strathdee2003) and illness duration ≥2 years); expected contact with mental health services (excluding inpatient services) during the time of study participation; sufficient command of the host country's language; and capability of giving informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: primary clinical diagnosis of mental retardation, dementia, substance use or organic brain disorder; cognitive impairment severe enough to make it impossible to give meaningful information on study instruments; and treatment by forensic mental health services. A paired member of staff was identified by the service user. Data were collected via questionnaires (filled in by the patient and their key worker) or via interviews conducted by the CEDAR study workers every 2 months for 1 year. Data entry modes were via computer or paper-pencil forms. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the phases of the study. Between November 2009 and December 2010, 708 patients were screened for inclusion of which 588 were included after having given written informed consent.

Fig. 1. Study participant flow.

Measures

The Clinical Decision Making Style Scale (CDMS; Puschner et al. Reference Puschner, Neumann, Jordan, Slade, Fiorillo, Giacco, Égerházi, Ivánka, Bording, Sørensen, Bär, Kawohl and Loos2013) measured preferences for decision making at baseline. Parallel patient (CDMS-P) and staff (CDMS-S) versions both have 20 items rated on a five-point Likert scale in three sections: (A) six items referring to general preferences regarding patient autonomy in decisions; (B) nine items referring to decision making preferences in three scenarios; and (C) five items referring to desire for information. CDMS sub-scales are Participation in Decision Making (PD) which consists of the mean of items in sections A and B (with a higher score indicating a higher desire by the service user to be an active participant in decision making), and Information (IN) consisting of the mean of items in sections C (ranging 0–4, 0 with a higher score indicating a higher desire by the service user to be provided with information). Categorical sum scores were formulated on the basis of utility where an emphasis was placed on separating categories according to clinical meaningfulness. Categories for the PD sub-scale were ‘passive’ (<1.5), ‘shared’ (1.5–2.5) and ‘active’ (>2.5), and for the IN sub-scale were ‘low’ (<2.0), ‘moderate’ (2.0–3.0) and ‘high’ (>3.0).

The Clinical Decision Making Involvement and Satisfaction Scale (CDIS; Slade et al. Reference Slade, Jordan, Clarke, Williams, Kaliniecka, Arnold, Fiorillo, Giacco, Luciano, Egerhazi, Nagy, Krogsgaard Bording, Østermark Sørensen, Rössler, Kawohl and Puschner2014) measured involvement and satisfaction with a specific decision at all time points. In order to have a common unit of analysis, patient and staff rated the decision identified by the patient as being the most important made at the latest treatment session. The scale has parallel patient (CDIS-P) and staff versions (CDIS-S). Each of the six items of the Satisfaction sub-scale is rated on a five-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5), yielding a total score of the mean of all items, ranging from 1 (low satisfaction) to 5 (high satisfaction). Clinical utility categories for the Satisfaction sub-scale were ‘low’ (<3.0), ‘moderate’ (3.0–4.0) and ‘high’ (>4.0). The Involvement sub-scale comprises one item about level of involvement experienced, which uses five categories which were collapsed into three (‘active’, ‘shared’ and ‘passive’ involvement). The CDMS and CDIS in all five study languages can be downloaded at http://www.cedar-net.eu/instruments.

Needs were assessed at all time points by the patient-rated version of the Camberwell Assessment of Need Short Appraisal Schedule (CANSAS-P; Trauer et al. Reference Trauer, Tobias and Slade2008) which measures the presence of a met or unmet need in 22 domains, yielding a total score indicating number of unmet needs ranging from 0 (low) to 22. Further measures included the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Thornicroft, Coffey and Dunn1995) which is a staff-rated one-item global measure of symptomatology and social functioning, ranging from 1 (worst) to 100, and the Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory (CSSRI-EU; Chisholm et al. Reference Chisholm, Knapp, Knudsen, Amaddeo, Gaite and van Wijngaarden2000) which is a standardised method for collating information on socio-economic status and service use. Participants were assessed by trained researchers not involved in the care process.

Sample size

Sample size calculation for the analyses of the primary outcome (effect of decision making on unmet needs over 1 year) via hierarchical linear modelling taking into account the centre-effect yielded a needed sample size of N = 561 (94 per centre). See study protocol for details (Puschner et al. Reference Puschner, Steffen, Slade, Kaliniecka, Maj, Fiorillo, Munk-Jorgensen, Larsen, Egerhazi, Nemes, Rössler, Kawohl and Becker2010).

Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests were used to compare proportions of the four nominal CDMS subscales. Baseline differences and change over time of the nominal CDIS subscales were examined by four mixed-effects multinomial regression models with time as fixed effect (Hedeker, Reference Hedeker2003). Based on concepts of causality (Bollen, Reference Bollen1989) and modelling change (Singer & Willett, Reference Singer and Willett2003), it was specifically tested for the 1-year observation period whether time-invariant (CDMS at baseline and covariates) and time-varying (CDIS at T0–T5) predictors affected subsequent unmet needs 2 months thereafter (T1–T6). This was done using of hierarchical linear modelling (Raudenbush & Bryk, Reference Raudenbush and Bryk2002) with the time variable months (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12). Fixed effects were time, clinical decision making variables, and covariates to control for confounding (study centre, patient age, duration of illness and diagnosis). Clustering of data (patients nested in key workers) was taken into account by specifying participants and staff as random effects.

Double-sided critical levels for significance tests were used. Prorating was used to deal with missing items in the computation of subscales for each participant, so long as there were fewer than 20% missing items for that participant, or else the scale was set to missing. Scales with specific instructions were exempted from this rule (as in the case of the CANSAS). Otherwise, there was no imputation of missing values. EpiData and SPSS versions 19–21 were used for data acquisition and checking, SuperMix 1 for the mixed-effects multinomial regression models and S-PLUS (version 6.2) for the hierarchical linear models.

Results

Sample

Table 1 gives an overview of sample characteristics. GAF score indicates serious symptomatology and social disability, indicating that the TAG threshold had successfully resulted in a sample of participants who can be characterised as having SMI. The ‘other’ category for professions included nurses, district nurses, support time and recovery workers, and psychiatric trainees.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients (n = 588) and staff (n = 213)

Missing values patients: n = 1 (married, ethnic group, work and benefits), n = 4 (living), n = 11 (school), n = 29 (GAF). Missing values staff: n = 6 (gender), n = 7 (profession), n = 54 (working outpatient), n = 41 (working mental health).

Preferred and experienced clinical decision making

Differences in proportions were significant for all four CDMS subscales. Both patients and staff indicated ‘shared’ as their preferred style of participation in decision making, with staff showing a stronger preference than patients. Desire for information was predominantly high in patient report, and mostly moderate in the view of staff (Table 2).

Table 2. Preferred clinical decision making style (participation and information) at baseline, and unmet needs over time

CDMS, Clinical Decision Making Style Scale; CANSAS, Camberwell Assessment of Need Short Appraisal Schedule.

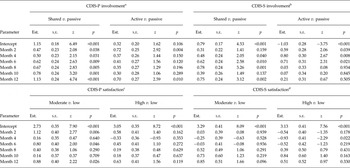

For the CDIS it was found that at baseline involvement in the last decision made was predominantly rated as ‘shared’ by both patients and staff (see intercepts in upper part of Table 3 and starting levels in Figure 2). Furthermore, patient ratings of ‘shared’ involvement significantly increased over time, accompanied by a decrease in rating of ‘active’ and ‘passive’. A similar trend of involvement ratings was found for staff (see month 2–month 12 in upper part of Table 3).

Fig. 2. CDIS involvement over time from patient and staff perspectives.

Table 3. Experienced clinical decision making (involvement and satisfaction) over time

CDIS-P/S, Clinical Decision Involvement and Satisfaction Scale Patient or Staff version; Est., estimate; s.e., standard error

a2444 observations of 651 patients; AIC = 4456.06;

b2223 observations for 621 patients; AIC = 3800.63;

c2447 observations of 650 patients; AIC = 3947.11;

d2227 observations for 621 patients; AIC = 3375.79.

Furthermore, the majority of the patients rated high the satisfaction with the way the last decision was made, a considerable proportion were moderately satisfied, and hardly any indicated low satisfaction. In comparison, staff satisfaction ratings were mostly moderate, closely followed by high and hardly ever low (see intercepts in lower part of Table 3 and starting levels in Figure 3). With only minimal changes, satisfaction ratings by both patients and staff were rather stable over time (Table 3).

Fig. 3. CDIS satisfaction over time from patient and staff perspectives. Numbers given for staff indicate observations per patient, not number of staff.

Clinical decision making and outcome

As shown in Table 2, there was a decrease in number of unmet needs over time. An unconditional hierarchical linear model showed that at baseline, starting level (intercept) was 3.30 unmet needs which significantly declined over time by −0.16 points per 2 months (slope; t = −9.06; p < 0.001; 3640 observations of 586 participants). To control for effects of study drop-out, this analysis was repeated for participants for whom number of unmet needs were available at all seven measurement points (N = 378), resulting in a similar pattern with intercept = 3.05 unmet needs and slope = −0.18 (t = −9.41; p < 0.001; 2646 observations).

As shown Table 4, a conditional hierarchical linear model yielded that slope constant was no longer significant in the model indicating that the included predictors substantially contributed to explaining variance of the rate of change of unmet needs (Singer & Willett, Reference Singer and Willett2003). Slope was affected by CDMS-S Participation, indicating that reduction of unmet needs over time was significantly higher in patients whose key workers rated their decision making style as active at T0 (v. passive). No effects were found for the other variables in the model. When recoding the reference category to shared, the effect of CDMS-S participation on slope remained (active: β = −0.303, t = −2.417, p = 0.015).

Table 4. Effect of clinical decision making on unmet needs

β, effect estimate; s.e., standard error; CI, confidence interval; 1726 observations of 499 patients within 189 key workers. Akaike information criterion (AIC) = 7668.6. CDMS-P/S, Clinical Decision Making Style Scale Patient or Staff version; CDIS-P/S, Clinical Decision Involvement and Satisfaction Scale Patient or Staff version. Reference categories: ‘passive’ for CDMS-P/S participation and CDIS-P/S involvement; ‘low’ for CDMS-P/S information and CDIS-P/S satisfaction. Results of control variables in the model not reported.

Discussion

This observational study on clinical decision making in routine care for people with SMI analysed the relationships between decision making style, involvement and satisfaction with decision making, and patient outcome. Both patient and staff perspectives were considered. The study design was longitudinal with seven assessment points.

In line with previous evidence (Hamann et al. Reference Hamann, Cohen, Leucht, Busch and Kissling2005; Hill & Laugharne, Reference Hill and Laugharne2006), people with SMI and their key workers predominantly stated a preference for a shared (rather than passive or active) decision making style. Both patients and staff indicated that involvement in decision making during their last treatment session was mainly shared. This trend increased over time, with about 10% more patients and key workers indicating that decision making 1 year later was shared. Furthermore, satisfaction with the decision made at the last treatment session was mostly high in patients and moderate in staff, with very little change over time. This finding corresponds with high and rather stable patient satisfaction with mental health service provision (Ruggeri et al. Reference Ruggeri, Salvi, Perwanger, Phelan, Pellegrini and Parabiaghi2006).

Patient-rated unmet needs significantly decreased over time. This pattern was found even when restricting the analysis to participants who had completed all seven measurement points, indicating that the decrease in unmet needs is not due to selective attrition. A comprehensive hierarchical linear model controlling for confounding effects showed that a staff-rated active decision making style was causally related to a significant reduction in patient-rated unmet needs. After 1 year, reduction of unmet needs in patients whose clinicians indicated a preference for an active decision making style was 2.44 (0.406 × 6, cf. Table 4) compared to passive, and 1.81 compared to shared. This effect is important because patient-rated unmet needs are associated with important outcome and process variables such as quality of life (Slade et al. Reference Slade, Leese, Cahill and Thornicroft2005) and the therapeutic alliance (Junghan et al. Reference Junghan, Leese, Priebe and Slade2007).

Unmet needs decreased over time, and patient and staff ratings of experienced shared involvement in decisions increased. CEDAR neither delivered an intervention nor encouraged a specific decision making approach, to the finding of decreased unmet needs might indicate the general effectiveness of specialist community treatment over 1 year. However, this result is inconsistent with other research showing relative stability in unmet needs in people with SMI over time at both 4-year (Lasalvia et al. Reference Lasalvia, Bonetto, Salvi, Bissoli, Tansella and Ruggeri2007) and 10-year follow-up (Arvidsson, Reference Arvidsson2008). Changes in experienced involvement may be due to social desirability bias, although it is unclear why such bias should increase over time. It is also possible that the increase over time was solely due to study participation, perhaps associated with increased self-monitoring or an assumption – even though not held by the study team – that shared decision making style was optimal. In other words, participation in the study might have been an important stimulus towards shared involvement, at least for staff. Clinical decision making might also differ within subgroups (e.g. by diagnosis, study cite or staff profession). Further analysis of the CEDAR data will examine these important issues.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the study include a large sample size of people with SMI from six European countries, and assessment of clinical decision making from both patient and staff perspectives. While adjusted for a number of variables, analyses could still be affected by confounders not controlled for, e.g. change of service provider of dissatisfied patients. It should also be noted that the instruments used to assess decision making did not measure actual behaviour, but preferences and subjective experiences with decision making. Furthermore, outcomes were patient-reported, so results might differ if staff- or observer-rated outcomes were used, as patient-rated scores might have been affected by study participation. Finally, even though overall dropout rates were low, the sample size varied in the different analyses of this paper, with number of missing values increasing with complexity of analyses.

Conclusions and outlook

This study provides evidence to improve decision making by professionals, and at the same time provides tools (CDMS and CDIS measures) for assessing important aspects of clinical decision making (Légaré et al. Reference Légaré, Ratté, Stacey, Kryworuchko, Gravel, Graham and Turcotte2010). For the first time, a staff-based causal influence of clinical decision making on outcome could be demonstrated, with two additional patient needs being met over 1 year being a substantial improvement. In line with emerging evidence that increased involvement leads to higher satisfaction (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Puschner, Jordan, Williams, Konrad, Kawohl, Bär, Rössler, Del Vecchio, Sampogna, Nagy, Süveges, Krogsgaard Bording and Slade2014), this means that decision making style of staff is a prime candidate for the development of targeted interventions building upon shared decision making approaches (Torrey & Drake, Reference Torrey and Drake2010). If proven effective in future trials, this would pave the ground for a shift from shared to active involvement of patients including changes to professional socialisation through training in principles of active decision making.

CEDAR study group

Bernd Puschner (chief investigator), Katrin Arnold, Esra Ay, Thomas Becker, Jana Konrad, Petra Neumann, Sabine Loos, Nadja Zentner (Ulm); Mike Slade, Elly Clarke, Harriet Jordan (London); Mario Maj, Andrea Fiorillo, Domenico Giacco, Mario Luciano, Corrado De Rosa, Gaia Sampogna, Valeria Del Vecchio, Pasquale Cozzolino, Heide Gret Del Vecchio, Antonio Salzano (Naples); Anikó Égerházi, Tibor Ivánka, Marietta Nagy, Roland Berecz, Teodóra Glaub, Ágnes Süveges, Attila Kovacs, Erzsebet Magyar (Debrecen); Povl Munk-Jørgensen, Malene Krogsgaard Bording, Helle Østermark Sørensen, Jens-Ivar Larsen (Aalborg); Wolfram Kawohl, Arlette Bär, Wulf Rössler, Susanne Krömer, Jochen Mutschler, Caitriona Obermann (Zurich).

Acknowledgements

CEDAR is a multicenter collaboration between the Section Process-Outcome Research, Department of Psychiatry II, Ulm University, Germany (Bernd Puschner); the Section for Recovery, Institute of Psychiatry, London, U.K. (Mike Slade); the Department of Psychiatry, Second University of Naples, Italy (Mario Maj); the Department of Psychiatry, Debrecen University, Hungary (Anikó Égerházi); the Unit for Psychiatric Research, Aalborg Psychiatric Hospital, Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark (Povl Munk-Jørgensen); and the Department of General and Social Psychiatry, University of Zurich, Switzerland (Wulf Rössler). We wish to thank the CEDAR study advisory board members Margareta Östmann, PhD (Malmö University, Sweden), Prof Sue Estroff, PhD (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, USA), Dirk Richter, PhD (Bern University for Applied Sciences, Switzerland) and Istvan Bitter, MD (Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary) for their support of our work.

Financial Support

This work was supported by a grant from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (Grant agreement number: 223290).

Conflict of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.