Significant outcomes

-

There was a negative correlation between CTQ and ERSQ total score among patients with mood disorder.

-

There were significant between-group differences in both the ERSQ total scores and each subscale between childhood trauma and ERSQ in mood disorders.

-

The BDI group had a more significant association between CTQ and ERSQ scores than the MDD and BDII patient groups.

Limitations

-

The was a cross-sectional study; therefore, a causal relationship between exposure to childhood trauma and outcomes could not be established.

-

The CTQ was retrospective; therefore, reporting bias may have been included.

-

Our sample sizes were disproportionate among patients with each mood disorder, which limits the generalisability of the results.

Introduction

Childhood trauma refers to a child enduring emotional or physical distress as a consequence of being directly exposed to or witnessing traumatic events or unfavourable circumstances (Young and Widom, Reference Young and Widom2014). Globally, child maltreatment is highly prevalent, with one in four children reporting having experience of physical, emotional, sexual, or neglect abuse (Krug et al., Reference Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg and Zwi2002; ;Moody et al., Reference Moody, Cannings-John, Hood, Kemp and Robling2018). Several studies have demonstrated that early child maltreatment develop depressive disorders, and increase odds of poor health outcomes as well as severe mental disorders (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb and Janson2009; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos2012; Salmon et al., Reference Salmon, Davila, Taillieu, Stewart-Tufescu, Duncan, Fortier, Struck, Georgiades, MacMillan and Kimber2022). Maltreatment during childhood can have a negative impact on a child’s ability to control their emotions later in life (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Jackson and Harding2010). This is because recurrent interpersonal trauma between children and caregivers inhibits the development of healthy emotional control abilities (Gaensbauer, Reference Gaensbauer1982 Reference Burns, Jackson and Harding). Moreover, experiencing early-life trauma is a significant risk factor for the development of psychological disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar I disorder (BDI), and bipolar II disorder (BDII), regardless of the type of abuse that occurred (Konradt et al., Reference Konradt, Jansen, d. S. Magalhães, Pinheiro, Kapczinski, d. Silva and d. Souza2013).

Emotional regulations are defined as external and internal procedure that oversee, assess, adjust emotional response, particularly in terms of their intensity and duration with the aim of achieving one’s objectives (Thompson, Reference Thompson1994). Previous studies have suggested that emotional regulation skills are strongly related to mental health status and psychological well-being (Kraiss et al., Reference Kraiss, Klooster, Moskowitz and Bohlmeijer2020). Deficiencies in emotional regulation are the most likely cause of psychiatric problems such as MDD, BD, and borderline personality disorder (Gruber et al., Reference Gruber, Eidelman, Johnson, Smith and Harvey2011), while positive emotional regulation is positively correlated with mental health indicators and stress management (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Zhang, Wang, Mistry, Ran and Wang2014).

Previous studies have indicated that children and adolescence who were exposed to early traumatic events were more likely at high risk of mental disorder with depression (Vibhakar et al., Reference Vibhakar, Allen, Gee and Meiser-Stedman2019; LeMoult et al., Reference LeMoult, Humphreys, Tracy, Hoffmeister, Ip and Gotlib2020; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Cannon, Chambers, Conroy, Coughlan, Dodd, Healy, O’Donnell and Clarke2021). Multiple studies have described the association between childhood trauma and the emergence of mood disorders, including MDD, and BD (Janiri et al., Reference Janiri, Sani, Danese, Simonetti, Ambrosi, Angeletti, Erbuto, Caltagirone, Girardi and Spalletta2015; Gill et al., Reference Gill, El-Halabi, Majeed, Gill, Lui, Mansur, Lipsitz, Rodrigues, Phan and Chen-Li2020). Particularly, patients with BD have more early traumatic episodes and they experience emotional abuse most frequently (Dualibe and Osório, Reference Dualibe and Osório2017).

One previous study indicated that emotional regulation skills mediate the association between childhood trauma and the course of depression (Hopfinger et al., Reference Hopfinger, Berking, Bockting and Ebert2016), and other have demonstrated that patients with MDD and BDI have difficulties with emotional regulation skills (Liu and Thompson, Reference Liu and Thompson2017, ). Previous Study have also indicated that maltreatment during childhood contirbutes difficulties on emotional regulation later in life (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Jackson and Harding2010). In particular, emotional abuse and neglect are more likely to have a negative impact on emotional regulation skills (Carvalho Fernando et al., Carvalho Fernando et al., Reference Carvalho Fernando, Beblo, Schlosser, Terfehr, Otte, Löwe, Wolf, Spitzer, Driessen and Wingenfeld2014).

While many studies have attempted to investigate the relationship between childhood trauma and mood disorders or emotional regulation and childhood trauma, studies explaining the relationship between emotional regulation and childhood trauma in patients with mood disorders are limited. Therefore, in this study we aimed to examine the relationship between childhood trauma and emotional regulation in patients with MDD, BDI, and BDII. We hypothesised that (1) childhood trauma and emotional regulation would have a significant association, (2) certain types of emotional regulation skills would be more likely to be associated with childhood trauma skills in mood disorder patients, and (3) the association between childhood trauma and emotional regulation would differ according to the mood disorder type.

Methods

Participants

Data from 779 outpatients with psychiatric disorders were analysed. All patients had a psychiatric diagnosis of a mood disorder such as MDD, BDI, or BDII based on the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), and were treated at the mood disorder clinic of the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital from July 2013 to February 2021. We collected relevant demographic information from patients, including age, sex, education, work status, marital status, smoking status, alcohol use status, family psychiatric history, and history of psychiatric hospitalisation. The diagnoses were assessed by trained researchers and confirmed by board-certified psychiatrists (T.H.H. and W.M.) through structured diagnostic interviews (using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview [MINI]) (Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker and Dunbar1998) or assessment of case records. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (protocol code B-2104-679-103, approved April 5, 2021).

Clinical instruments

Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire (ERSQ)

The Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire (ERSQ) is a 27-item self-reported questionnaire used to evaluate a broad range of emotional regulation skills. Each item is assessed on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = not at all, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, and 4 = almost always). The following nine subscales were used to evaluate successful skill use: awareness, sensation, clarity, understanding, acceptance, resilience, self-support, tolerance, and modification. Each subscale comprised three items (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Salsman and Berking2018).

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-short form (CTQ)

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ) (Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Stein, Newcomb, Walker, Pogge, Ahluvalia, Stokes, Handelsman, Medrano and Desmond2003) is a retrospective self-reporting scale that asks questions about childhood and adolescent experiences (those experienced below the age of 18) using 28 items rated on a five-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1–5 (1 = never true, 2 = rarely true, 3 = sometimes true, 4 = often true, and 5 = very often true). The five trauma subtypes were emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Based on a previous study, we used a modified CTQ score that excluded minimisation/denial scores (items 10, 16, and 22), with scores ranging from 25–125, and potential scores ranging from 5–25 for each subscale.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the demographic and clinical variables were analysed. An independent samples t-test was performed for continuous variables, such as age, and a chi-square test was used for categorical variables, such as sex, employment status, marital status, family psychiatric history, alcohol consumption, and smoking status. Analysis of covariance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare the ERSQ and CTQ scores between patients with mood disorders, followed by post hoc testing with Bonferroni correction to ascertain the direction of the differences. We calculated the partial correlation coefficients between the ERSQ and CTQ scores using residuals from multiple regression while controlling for potential confounding factors (age, sex, education, employment, marital status, psychiatric first-degree family history, alcohol use status, and smoking status). Furthermore, we used multiple linear regression analysis with an interaction term to determine the correlation between the ERSQ and CTQ scores by group, with the MDD group serving as the reference group. (ERSQ total score–CTQ total score + CTQ total score × diagnosis [e.g. MDD (reference), BDI, BDII] + age + sex + education + employment + marital status + smoking + alcohol use status + family psychiatric history). All statistical analyses were two-tailed, with significance set at p < 0.05. Bonferroni correction was used to correct for type I errors from multiple tests, which involved multiplying the unadjusted p-value by the total number of tests. All analyses were performed using R, version 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Clinical and demographic characteristics

The clinical and demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The participants’ ages ranged from 16–69 years, with a mean age of 34.25 (standard deviation [SD] = 12.10) years. Data from 779 patients with psychiatric disorders (MDD [n = 240] BDI, [n = 121], and BDII [n = 418]) were analysed. The study included 220 male and 559 female participants.

Table 1. Clinical and demographic characteristics of participants (n = 779)

1 Statistical significance in mood disorders.

2 F-test was used; Data are given as mean and standard deviation.

3 Chi-square test was used.

4 Single, divorced, widowed.

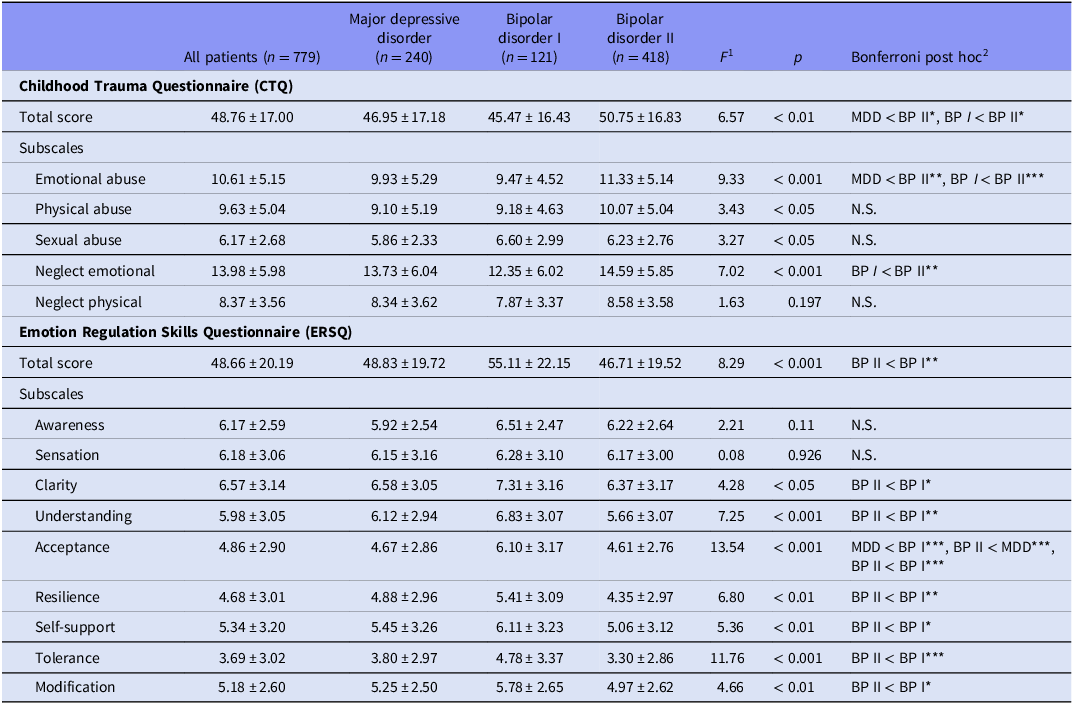

ERSQ and CTQ scores for patients with mood disorders

There were significant differences between the patients in terms of both the CTQ (F = 6.57, p <0.01) and ERSQ total scores (F = 8.29, p <0.001). In the CTQ subscale analysis, we found significant between-group differences between mood disorders in terms of emotional abuse (F = 9.33, p <0.001) and emotional neglect (F = 7.02, p <0.001). In the ERSQ subscale analysis, we observed significant differences between patients on the subscales. In particular, patients with BDI had significantly higher scores for clarity (mean ± SD = 7.31 ± 3.16) than those with BDII (6.37 ± 3.17, p <0.05). Likewise, the scores for understanding and tolerance were significantly higher among patients with BDI than among those with BDII (p <0.001). Scores for resilience and self-reporting of the BDI group were also higher than those of the BDII group (p <0.01), whereas the score for acceptance in patients with BDII (mean ± SD = 4.61 ± 2.76) was significantly lower than that for patients with BDI (6.10 ± 3.17, p <0.001), and MDD (4.67 ± 2.86, p <0.001). In the Bonferroni post hoc comparisons, we found multiple differences in the total and subscale scores of both the CTQ and ERSQ. Detailed results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Total and subscale scores of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) and Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire (ERSQ) in patient groups

Values are presented as mean and standard deviation.

1 ANOVA was used between all patient groups.

2 ANOVA with pairwise test after Bonferroni post hoc was used between all patient groups.

1, 2 Adjusted p-values with Bonferroni’s correction were calculated multiplying raw p-values by total number of multiple testing of subscales (p = 0.05 ×5 for CTQ, p = 0.05 ×9 for ERSQ).

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, N.S. = not significant.

The relationship between childhood trauma and emotional regulation skills

A residual correlation analysis after adjusting for confounding factors (age, sex, education, employment, marital status, psychiatric first-degree family history, alcohol use status, and smoking status) demonstrated that the CTQ total score was negatively correlated with the ERSQ total score (r = − 0.136, p <0.001). These findings indicate that individuals with higher scores for childhood trauma have weaker emotional regulation skills. Among the CTQ subscales, emotional neglect was most negatively correlated with the ERSQ total score (r = −0.199, p <0.001). Among the ERSQ subscales, acceptance was most negatively correlated with the CTQ total score (r = −0.146, p <0.01, Figure 1, Supplementary Table S1). Tolerance and resilience were also negatively correlated with the CTQ total score (r = −0.140, corrected p <0.05 and r = −0.131, p <0.01, respectively), as were clarity and understanding (r = −0.121, p <0.05and r = −0.118, corrected p <0.05, respectively, Figure 1, Supplementary Table S1). In terms of gender differences, the CTQ total score was negatively correlated with the ERSQ total score: r = −0.141, corrected p <0.001 for female participants; r = −0.104, while the correlation between the CTQ and ERSQ total scores was not significant for male participants (Supplementary Table S5-6).

Figure 1. Partial correlation plot between Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) scores, Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire (ERSQ) scores. Partial correlation coefficients (p <0.05) are shown in the figure and partial correlation coefficients (p >0.05) are marked as X. Positive correlations are shown in blue colour and negative correlations in red colour. Colour intensity is proportional to the partial correlation coefficients. A. All patients (n = 779), B. Major depressive disorder (n = 240), C. Bipolar I disorder (n = 121), D. Bipolar II disorder (n = 418).

Relationship between childhood trauma and emotional regulation skills according to mood disorder diagnosis

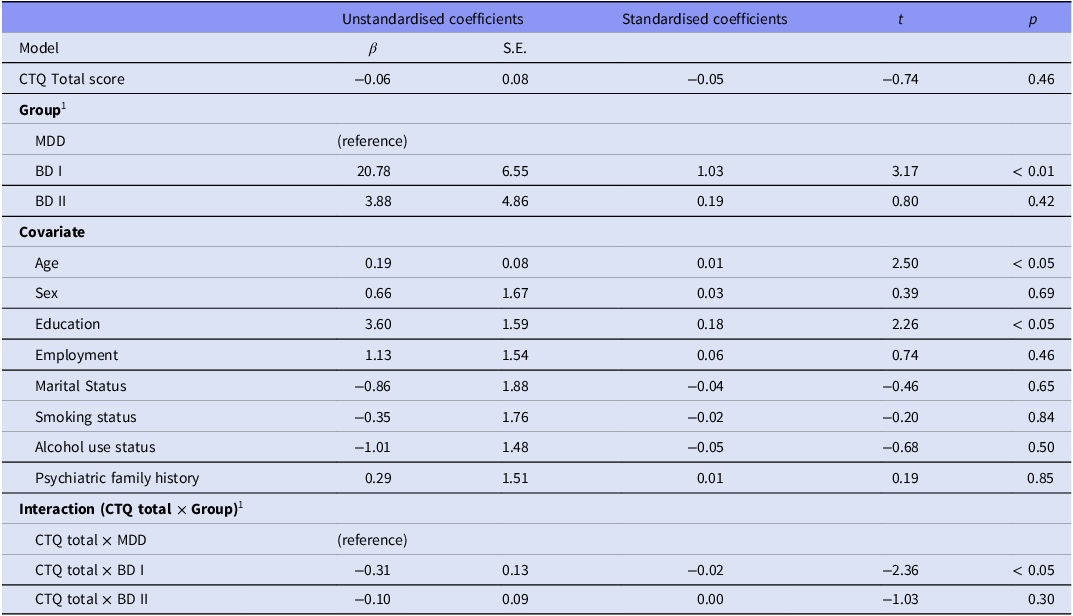

For patients with BDII, as CTQ total scores increased, the decrease in ERSQ total scores was similar to that observed in patients with MDD. In patients with BDI, the CTQ total score had a greater impact on the ERSQ total score, as the ERSQ total score sharply decreased when the CTQ scores increased. The significance of the two-way interaction effects of childhood trauma (CTQ total score) and mood disorders (MDD, BDI, and BDII) on emotional regulation (ERSQ total score) was examined using multiple regression models (Table 3). The main effect terms for the CTQ total score and group, as well as the two-way interaction term (CTQ total score × group), were entered into the regression model after the terms for potential confounding variables (age, sex, education, employment, marital status, family psychiatric history, alcohol use status, and smoking status) were used in the assessment. The findings demonstrated that the two-way interaction coefficient was significant for patients with BDI (β = –0.31, SE = 0.13, interaction p < 0.05), but not for patients with BDII (β = −0.10, SE = 0.09, interaction p = 0.30), using patients with MDD as the reference group (Figure 2). These findings imply that the ERSQ total score in patients with BDI had a greater impact on CTQ scores, as the decrease in ERSQ was larger than that in other patients when CTQ increased.

Figure 2. Multiple linear regression for the association between CTQ and ERSQ by mood disorders. Interactive effects of CTQ (Childhood Trauma Questionnaire) score and mood disorders on ERSQ (Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire) are shown in the figure. X-axis denotes level of CTQ score and Y-axis denotes level of ERSQ score. Regression lines (shaded area = 95% CI) are shown in solid for the major depressive disorder (MDD) group, dotted for bipolar II disorder (BDII), two dash for bipolar I disorder (BDI) group.

Table 3. The main effect and interactive effects of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) and group on Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire (ERSQ)

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) scores and interaction term were used as independent variable, and Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire (ERSQ) scores were used as dependent variable.

1 MDD group was used as reference group.

Age, sex, education, employment, marital status, psychiatric first-degree family history, alcohol use status and smoking status were adjusted.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the association between childhood trauma and emotional regulation skills in patients with Major Depressive Disorder, Bipolar Disorder I and Bipolar Disorder II. We observed a significant negative association between childhood trauma and emotional regulation skills regarding both total scale scores and each subscale score. It is important to highlight that emotional neglect was most significantly associated with lower level of emotional regulation skills. Among the subtypes of emotional regulation skills, acceptance and tolerance showed the strongest negative correlations with the total childhood trauma score. In addition, the association between childhood trauma and emotional regulation skills varied by mood disorder, and the association was more prominent in patients with BDI than in those with MDD or BDII. These findings contribute to our understanding of the relationship between emotional regulation skills and early childhood trauma in patients with various mood disorders.

Several studies have demonstrated that childhood abuse can influence the regulation of emotions and serve as a risk factor for the development of mood disorders (Kim and Cicchetti, Reference Kim and Cicchetti2010; Hosang et al., Reference Hosang, Fisher, Hodgson, Maughan and Farmer2018). Another study found that experiencing greater maltreatment as a child was associated with an increase in negative emotional convictions and psychological inflexibility, resulting in reduced emotional regulation (Bozorgi Kazerooni and Gholamipour, Reference Bozorgi Kazerooni and Gholamipour2023). Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies, as we observed significant negative correlations between the CTQ and emotional regulation skills scores. Moreover, emotional neglect was most negatively associated with emotional regulation skills. A previous study found that individuals who had experienced emotional neglect tended to have difficulties in emotional regualtion. Because neglectful parents are less likely to teach skills for coping strategies for emotional regulation (Shipman et al., Reference Shipman, Edwards, Brown, Swisher and Jennings2005).

In addition, our results support the second hypothesis that certain emotional regulation skill subtypes are closely associated with childhood trauma. Our study found that childhood trauma total score was negatively associated with acceptance and tolerance. If individuals had a higher score for childhood trauma, they had a lower score for acceptance and tolerance on the emotional regulation skills. A previous study found that individuals with early post trauma were less likely to have high emotional acceptance on the ERSQ subscales (Tull et al., Reference Tull, Barrett, McMillan and Roemer2007). This finding might be a consequence of individuals attempting to avoid stressful emotions rather than dealing with them, as a result of learning helplessness, influenced by abuse and neglect from childhood (Milojevich et al., Reference Milojevich, Levine, Cathcart and Quas2018). Additionally, cognitive vulnerability from childhood adversity may result in a negative bias in emotions (Beevers, Reference Beevers2005). Individuals with a history of emotional childhood adversity exhibit reduced tolerance of the emotional aspects of pain (Gratz et al., Reference Gratz, Bornovalova, Delany-Brumsey, Nick and Lejuez2007; Erol and Inozu, Reference Erol and Inozu2023). A decrease in tolerance may result in the interaction between a person’s biological vulnerabilities and an invalidating social environment (Linehan, Reference Linehan2018). Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies, as emotional neglect and abuse had a significant negative correlation with tolerance.

The relationship between childhood trauma and ERSQ differed according to mood disorder. Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with Bipolar disorders who are exposed to childhood trauma have deficits in emotional regulation and stability (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Aminoff, Lagerberg, Etain, Agartz, Andreassen and Melle2014, Reference Aas, Henry, Andreassen, Bellivier, Melle and Etain2016). Our results are consistent with those of these previous studies, as there was a significant negative correlation between childhood trauma and ERSQ scores in patients with BDI and BDII, but not in patients with MDD. Additionally, for patients with BDI, as the CTQ total scores increased, the decrease in ERSQ total scores was greater than that in patients with BDII and MDD. A potential explanation for this finding is that the association between childhood trauma and ERSQ scores in patients with BDII and MDD was less pronounced than that in patients with BDI, as the impact of multiple depressive episodes was larger than that of childhood trauma. Previous studies have suggested that MDD and BDII showed longer phrase of depression with recurrent depressive episodes ( Forte et al., Reference Forte, Baldessarini, Tondo, Vázquez, Pompili and Girardi2015) and that recurrent depressive episodes impact emotional regulation across all aspects of executive functioning and self-awareness (Arditte and Joormann, Reference Arditte and Joormann2011). Our results are expected to help clinicians understand patients with mood disorders who experienced child trauma, and plan appropriate treatment for each mood disorder. Particularly, it is likely more important to address the history of childhood adversity in patients with BD I for planning therapeutic intervention.

In the subgroup analysis for patients with MDD, BD I, and BD II, tolerance, one of the subtypes of emotional regulation skills, has a significant relationship with emotional abuse in patients with BD I. Previous studies demonstrated that patients with BD I frequently showed impulsivity as well as higher aggressiveness, and mood lability during manic episodes (Swann, Reference Swann2010), and they usually had emotional trauma during childhood (Dualibe and Osório, Reference Dualibe and Osório2017). Therefore, patients with BD I who experienced emotional abuse may experience more difficulty to tolerate or regulate their emotion than those with other mood disorders (Miola et al., Reference Miola, Cattarinussi, Antiga, Caiolo, Solmi and Sambataro2022). Our findings were consistent with previous studies as tolerance was negatively correlated with emotional abuse and neglect in patients with BD I. This result assists clinicians in differential diagnosis among mood disorder patients, particularly in identifying patients with BD I. Considering our result, patients with BD I who have higher scores in child trauma may show more difficulties in emotional tolerance as mood disorder symptoms.

The present study had a few limitations. First, it was cross-sectional in nature; therefore, a causal relationship between exposure to childhood trauma and outcomes could not be established. Second, the CTQ was retrospective; therefore, reporting bias may have been included (Hardt and Rutter, Reference Hardt and Rutter2004). False-negative reports occur when individuals refuse to report upsetting memories they avoid retrieving or when older participants are unable to recall childhood episodic memories from the past (Hänninen and Soininen, Reference Hänninen and Soininen1997). Third, our sample sizes were disproportionate among patients with each mood disorder, which limits the generalisability of the results. Since we had varying sample sizes of patients with MDD (n = 240), BDI (n = 121), and BDII (n = 418), this could have affected our accuracy in detecting the differences between these groups. Fourth, we did not assess the participants’ age of onset and number of mood episodes. However, these may be significant variables as a previous study has demonstrated child trauma is negatively associated with an earlier age at the onset of bipolar depression and a greater number of mood episodes (Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Aas, Klungsøyr, Agartz, Mork, Steen, Barrett, Lagerberg, Røssberg and Melle2013). In addition, to better address participants’ information, we should collect additional data such as medication and physical health status. Fifth, we did not evaluate present mood status especially depressive symptoms at the time of the CTQ and ERSQ responses. According to a prior study, euthymic patients experience less psychological distress from traumatic life events than bipolar disorder patients during manic, hypomanic, or depressive episodes (Sato et al., Reference Sato, Hashimoto, Kimura, Niitsu and Iyo2018). As a result, patients’ present mood status may impact on how they recall traumatic events and respond to emotion regulation skills. Lastly, we did not recruit a psychiatric healthy group as a control group. Therefore, the study should be investigated in both the patient group and control group by matching age and gender to ensure the validity of the research (Basham, Reference Basham1986). Despite these limitations, our study showed a significant association between the CTQ and ERSQ across diverse mood disorders, including MDD, BDI, and BDII. Previous studies have investigated emotional regulation skills as mediators between childhood trauma and depressive disorders (Janiri et al., Reference Janiri, Sani, Danese, Simonetti, Ambrosi, Angeletti, Erbuto, Caltagirone, Girardi and Spalletta2015, Gill et al., Reference Gill, El-Halabi, Majeed, Gill, Lui, Mansur, Lipsitz, Rodrigues, Phan and Chen-Li2020). As our study observed significant CTQ and ERSQ subscale correlations, as well as significant differences between mood disorder patients, the present study may be helpful in future studies investigating childhood trauma and emotional regulation in various psychopathological populations, including those with mood disorders.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated an association between childhood trauma and emotional regulation skills in patients with MDD, BDI, and BDII. The results indicated a negative correlation between the CTQ and ERSQ total scores. The study also found that certain types of emotional regulation skills were more likely to be associated with total childhood trauma scores and vice versa. Specifically, among the CTQ scales, the emotional neglect scales were negatively correlated with the ERSQ total score. Patients with BDI showed a significant correlation between the CTQ and ERSQ scores. Our findings provide insights into the relationship between childhood traumatic experiences and the ERSQ in the context of mood disorders.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2024.41.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

WM and THH had full access to all the data in this study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conceptualisation: Yejin Park, Chan Woo Lee, Tae Hyon Ha, Woojae Myung.

Data curation: Yejin Park, Chan Woo Lee, Hyeona Yu, Joohyun Yoon, Yun Seong Park, Hyun A Ryoo.

Funding acquisition: Woojae Myung.

Investigation: Yejin Park, Chan Woo Lee, Hyeona Yu, Joohyun Yoon, Yun Seong Park, Hyun A Ryoo, Daseul Lee, Hyuk Joon Lee.

Methodology: Yejin Park, Chan Woo Lee, Yeong Chan Lee, Chan Woo Lee, Hong-Hee Won, Tae Hyon Ha, Woojae Myung.

Supervision: Hong-Hee Won, Tae Hyon Ha, Woojae Myung.

Writing – original draft: Yejin Park, Chan Woo Lee.

Writing – review & editing: All authors.

Funding statement

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea Grant, funded by the Korean government (NRF-2021R1A2C4001779 and RS-2024-00335261; WM). The funding body had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of this report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in this study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Institutional review board statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National Bundang Hospital (protocol code B-2104-679-103, approved April 5, 2021).

Informed consent statement

Patient consent was waived because data was gathered through a medical chart review. Comparison consent was also waived as the researchers did not have direct access to participant personal information and used anonymised survey data for analyses.