Stigma and discrimination can significantly compound the difficulties facing people with mental health problems. Reference Peterson, Pere, Sheehan and Surgenor1,Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius, Leese and Indigo2 In England public attitudes towards people with mental health problems had not improved prior to the start of the Time to Change (TTC) programme in 2008, in spite of greater understanding about the causes of these problems. Reference Mehta, Kassam, Leese, Butler and Thornicroft3 In the USA attitudes have worsened in recent years, for example in relation to people with schizophrenia. Reference Pescosolido, Martin, Long, Medina, Phelan and Link4 To date there has been no evaluation at the national level of interventions to reduce discriminatory behaviour, as rated directly by people using mental health services. Reference Mehta, Kassam, Leese, Butler and Thornicroft3,Reference Crisp, Gelder, Rix, Meltzer and Rowlands5-Reference Thornicroft, Rose, Kassam and Sartorius8 In January 2009 the largest ever programme in England to reduce stigma and discrimination against people with mental health problems was launched, called Time to Change (www.time-to-change.org.uk/). Reference Henderson and Thornicroft9 A target set by the mental health charities Mind and Rethink Mental Illness was to achieve a 5% reduction in discrimination experienced by people with mental health problems between 2008 and 2011. The purpose of this study was to determine whether this target had been met.

Method

Telephone interview surveys (called the Viewpoint survey) were conducted annually between 2008 (baseline) and 2011. Different samples were used for each year. Participants were recruited through National Health Service (NHS) mental health trusts (service provider organisations). Participants were eligible to take part if they were aged 18-65 years, had any mental health diagnosis (excluding dementia) and had been in recent receipt of specialist mental health services (contact in the previous 6 months). We excluded people who were not currently living in the community (e.g. were in prison or hospital) because participants needed to be available to take part in a sensitive, confidential telephone survey. Our target sample was 1000 individual interviews in each year, based on power calculations to detect a 5% change in discrimination experiences.

Setting

Each year five NHS mental health trusts across England were selected to take part. Trusts were intended to be representative of all such trusts in the country, based on the socioeconomic deprivation level of their catchment area. Catchment areas for the whole of England were ordered using a score calculated from census variables chosen on the basis of an established association with mental illness rates, Reference Glover, Robin, Emami and Arabscheibani10 including lack of access to a car, permanent sickness, unemployment, being single, divorced or widowed, and living in housing that was not self-contained. We then selected five trusts to ensure areas in each quintile of socioeconomic deprivation were included. Different trusts and/or different regions within the same trusts were selected each year.

Participants

Within each participating trust, non-clinical staff in information technology or patient records departments used their central patient database to select a random sample of people receiving care for ongoing mental health problems. The sample size in 2008 was 2000 out-patients per trust based on a predicted response rate of 25% as achieved for the charity Rethink Mental Illness membership surveys. In 2009-2011 it was 4000 out-patients per trust to ensure we met the target sample after missing this in 2008. The sample was checked by clinical care teams to confirm eligibility and to remove those who were judged to be at risk of distress from receiving an invitation to participate. Invitation packs were mailed to potential participants from the trusts (8917 in 2008; 12 887 in 2009; 12 866 in 2010; 9120 in 2011). The packs contained complete information about the study including lists of interview topics, local and national sources of support, and a consent form. After 2008 information was also included in 13 commonly spoken languages explaining how to obtain the information pack in another language if needed. If no response was received a reminder letter was sent after approximately 2 weeks. Participants returned the completed consent forms, including contact details, by post directly to the research team. Participants in 2011 were offered a £10 voucher for taking part.

Data collection

The Discrimination and Stigma Scale (DISC) was used to measure both experienced and anticipated discrimination. Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius, Leese and Indigo2 Sociodemographic characteristics, diagnosis and brief clinical information were also recorded. The DISC was interviewer-administered, in this case by telephone, and contained 22 items on negative, mental health-related experiences of discrimination (covering 21 specific life areas, plus one for ‘other’ experience) and 4 items concerning anticipated discrimination. All responses were given on a four-point scale from ‘not at all’ to ‘a lot’. Where items related to situations that were not relevant to the participant in the previous 12 months (e.g. in relation to having children or seeking employment), or if a diagnosis could not have been known about in that situation, a ‘not applicable’ option was used. Recent analysis of the DISC has found that it has adequate psychometric properties. Reference Brohan, Slade, Clement, Rose, Sartorius and Thornicroft11

All telephone interviewers were trained and supervised by the research team. The majority of interviewers were themselves users of mental health services. Participants were allocated to interviewers according to availability. Once an interviewer had made contact with a participant an interview was conducted or scheduled. If, after three scheduled appointments, an interview had not been successfully completed, the participant was considered to have withdrawn. Consent was confirmed verbally by the interviewer prior to start of the interview.

Statistical analysis

Analysis used SPSS version 15 and Stata version 11.2 for Windows. Overall experienced discrimination scores were calculated by counting any reported instance of negative discrimination as ‘1’ and situations in which no discrimination was reported as ‘0’. The overall score was then calculated as the number of instances of reported discrimination divided by the number of questions answered (only applicable answers were included) and multiplied by 100 to give the percentage of items in which discrimination was reported. For example, if a participant reported discrimination for 13 out of the possible 22 items and also reported that 4 items were not applicable, then the overall score would be 13/(22–4)×100 = 72%. To compare the yearly samples for frequencies of experiences from each source of discrimination (i.e. each DISC item), a binary variable - ‘no discrimination’ v. ‘any discrimination’ - was created for each item. In 2008, three items were used to measure anticipated discrimination. One was split into two items from 2009; we therefore compared only the two items common to all years.

Sampling weights were calculated separately for each year to account for demographic disparities in both the Viewpoint and NHS data between years, for characteristics on which good NHS data were available, i.e. gender, age and ethnicity. Weights were derived from the proportion of people using NHS mental health services divided by the proportion of Viewpoint participants for each characteristic. Patient information from the NHS data-set was selected to closely match Viewpoint inclusion criteria. Weights were then aggregated to provide an overall weight for each individual's combination of characteristics. A chi-squared test was carried out to check for differences in demographic characteristics between the years. Weighted analyses are reported where appropriate. A Holm-Bonferroni correction was used to control for the effects of multiple testing.

The study received ethical approval from Riverside NHS ethics committee.

Results

We interviewed 3579 participants between 2008 and 2011. For details of participant characteristics see Table 1. Response rates in 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2011 were 6%, 7%, 8% and 11% respectively. In all years, women and White British participants were overrepresented in our sample compared with data provided by the NHS Information Centre. 12

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of participants

| 2008 (n = 537) |

2009 (n = 1047) |

2010 (n = 979) |

2011 (n = 1016) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 188 (35) | 389 (37) | 369 (38) | 411 (40) |

| Female | 344 (64) | 654 (63) | 605 (62) | 602 (59) |

| Transgender | 0 (0) | 3 (0) | 5 (0) | 2 (0) |

| Missing | 5 (1) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Age, years | ||||

| Range | 18-65 | 18-65 | 18-65 | 18-65 |

| Mean (s.d.) | 46 (11) | 46 (11) | 46 (11) | 45 (11) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White British | 504 (94) | 904 (86) | 872 (89) | 868 (85) |

| Other White | 11 (2) | 51 (5) | 46 (5) | 36 (4) |

| Black or mixed Black/White | 6 (1) | 29 (3) | 25 (3) | 40 (4) |

| Asian or mixed Asian/White | 4 (1) | 33 (3) | 27 (3) | 53 (5) |

| Other mixed | 0 (0) | 13 (1) | 4 (0) | 5 (0) |

| Other | 1 (0) | 6 (0) | 1 (0) | 7 (1) |

| Did not wish to disclose | 11 (2) | 1 (0) | 4 (0) | 7 (1) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||||

| Unemployed | 264 (49) | 355 (34) | 370 (38) | 485 (48) |

| Part-time employed | 75 (14) | 98 (9) | 90 (9) | 90 (9) |

| Full-time employed | 72 (13) | 146 (14) | 175 (18) | 121 (12) |

| Retired | 70 (13) | 104 (10) | 33 (3) | 95 (9) |

| Volunteering | 32 (6) | 67 (6) | 85 (9) | 52 (5) |

| Training/education | 24 (5) | 34 (3) | 77 (8) | 20 (2) |

| Other (incl. self-employed) | 0 (0) | 242 (23) | 88 (9) | 152 (15) |

| Clinical diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Bipolar disorder | 147 (27) | 257 (25) | 194 (20) | 184 (18) |

| Depression | 137 (26) | 294 (28) | 331 (34) | 311 (31) |

| Missing | 71 (13) | 58 (6) | 69 (7) | 109 (11) |

| Schizophrenia | 59 (11) | 135 (13) | 113 (12) | 116 (11) |

| Anxiety disorder | 36 (7) | 59 (6) | 57 (6) | 82 (8) |

| Other | 26 (5) | 121 (12) | 128 (13) | 121 (12) |

| Personality disorder | 20 (4) | 61 (6) | 41 (4) | 55 (5) |

| Eating disorder | 16 (3) | 8 (1) | 11 (1) | 6 (1) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 16 (3) | 35 (3) | 24 (3) | 26 (3) |

| Multiple diagnoses | 6 (1) | 7 (1) | 3 (0) | 4 (0) |

| Substance misuse/addiction | 3 (1) | 2 (0) | 3 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Received involuntary treatment, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 212 (40) | 418 (40) | 309 (32) | 353 (35) |

| No | 325 (60) | 628 (60) | 668 (68) | 663 (65) |

Significant differences were found for ethnicity, employment status, gender and whether participants had been admitted to hospital involuntarily between the 2008 and 2011 samples.

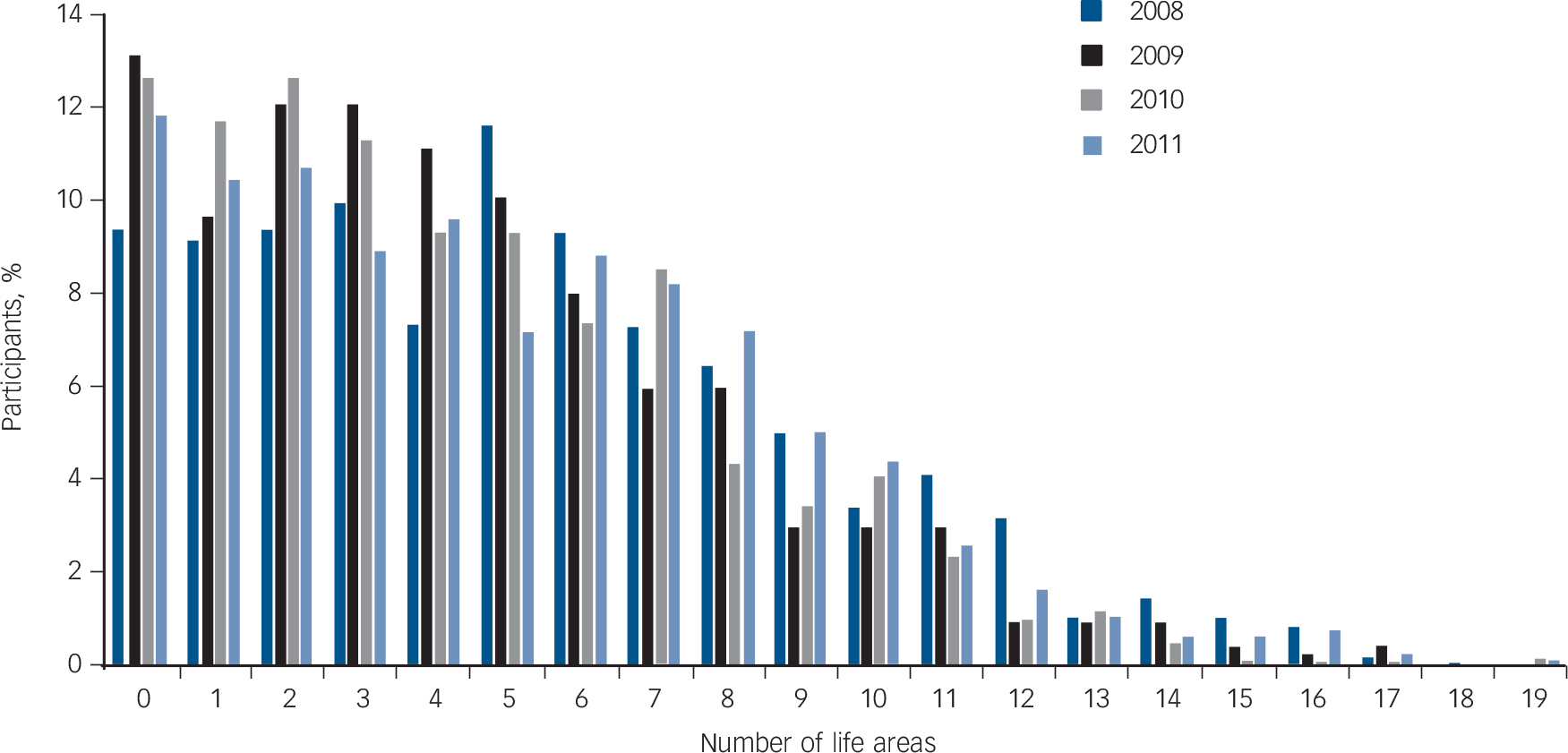

Experienced discrimination

In 2008 over nine-tenths (91%) of participants reported one or more experiences of discrimination, compared with 88% in 2011 (z = −1.94, P = 0.05). The equivalent figure was 87% in 2009 (z = −3.2, P = 0.001) and 87% in 2010 (z = 2.4, P = 0.02). The median number of life areas in which participants reported discrimination was five (interquartile range 2-7) in 2008 and four in 2009 (IQR 1-6), 2010 (IQR 3-7) and 2011 (IQR 3-7). A Kruskal-Wallis test suggested that there was a significant difference between the underlying distributions of the number of life areas of experienced discrimination between 2008 and 2011 (χ2 = 29.1, P<0.001). Figure 1 shows the profile for the overall experienced discrimination score for each of the samples; a Kruskal-Wallis test suggested a significant difference between the underlying distributions of scores between 2008 and 2011 (χ2 = 83.4, P<0.001).

Fig. 1 Distribution of discrimination experiences reported in 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2011.

Table 2 shows the frequency with which participants reported negative discrimination in 2008-2011 for the life areas covered by the DISC. For 17 of the 21 items (i.e. excluding ‘other’) the experienced discrimination reported was less in 2011 than in 2008, but not all these differences were statistically significant. Discrimination in four areas increased between 2008 and 2011: safety, benefits, marriage and transport. These increases were not significant after allowing for multiple testing.

Table 2 Negative discrimination 2008-2011

| Participants reporting discrimination, % | Direction of change 2008-2011 |

Significant after Holm-Bonferroni correction |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life area | 2008 | 2011 | Z (d.f.)Footnote a | P Footnote a | ||

| Being shunned | 57.9 | 50 | Reduction | –2.94 (3,1) | <0.01 | Yes |

| Friends | 53.3 | 39.4 | Reduction | –5.04 (3,1) | <0.01 | Yes |

| Family | 53.1 | 43.7 | Reduction | –3.23 (3,1) | <0.01 | Yes |

| Social life | 43.2 | 31.5 | Reduction | –3.52 (3,1) | <0.001 | Yes |

| Neighbours | 25.3 | 22.7 | Reduction | 0.53 (3,1) | 0.60 | NA |

| Mental health staff | 34.3 | 30.4 | Reduction | –1.11 (3,1) | 0.27 | NA |

| Dating | 30.9 | 22.1 | Reduction | –2.13 (3,1) | 0.03 | No |

| Physical health | 29.6 | 28.9 | Reduction | –0.08 (3,1) | 0.94 | NA |

| Finding a job | 24.2 | 18.6 | Reduction | –1.92 (3,1) | 0.05 | NA |

| Privacy | 21.6 | 20.0 | Reduction | –1.15 (3,1) | 0.25 | NA |

| Safety | 19.6 | 24.8 | Increase | 0.21 (3,1) | 0.84 | NA |

| Benefits | 19.0 | 24.9 | Increase | 2.16 (3,1) | 0.03 | No |

| Parenting | 18.6 | 15.6 | Reduction | –0.88 (3,1) | 0.38 | NA |

| Keeping a job | 16.9 | 16.6 | Reduction | –0.99(3,1) | 0.32 | NA |

| Police | 16.4 | 16.1 | Reduction | –0.21 (3,1) | 0.83 | NA |

| Housing | 14.7 | 13.3 | Reduction | 0.20 (3,1) | 0.84 | NA |

| Education | 12.3 | 10.2 | Reduction | –0.76 (3,1) | 0.45 | NA |

| Marriage | 12.1 | 17.3 | Increase | 1.34 (3,1) | 0.18 | NA |

| Transport | 11.4 | 12.0 | Increase | 1.09 (3,1) | 0.27 | NA |

| Starting a family | 10.8 | 6.9 | Reduction | –1.45 (3,1) | 0.15 | NA |

| Religious activities | 10.1 | 4.3 | Reduction | –2.52 (3,1) | <0.01 | No |

NA, not applicable.

a. Score after weighting.

Across all years the most commonly reported sources of discrimination were family, friends and social life contacts, or a general report of being avoided or shunned. All four of these items showed a significant reduction in reported discrimination between baseline and the following three years, with the exception of family, which had a significant reduction between baseline and 2011 only (data shown only for 2008-2011 comparison). For five items (finding a job, keeping a job, police, education and starting a family) significant reductions in reported discrimination between 2008 and 2009 or 2010 were not sustained in the 2011 sample, such that there was no significant overall change from baseline at the end of this period (data shown only for 2008-2011 comparison).

Awareness of anti-stigma campaign and reported discrimination

From 2009 onwards participants were asked whether they were aware of the Time to Change programme and whether they had participated in any of its activities. Using data from all relevant years, we compared discrimination scores of participants who had been aware of the programme (n = 661; median discrimination score 30.8, s.d. = 22.3) with those who were not (n = 2366; median discrimination score 25.0, s.d. = 22.8). A Mann-Whitney test showed a significant difference between the groups' overall discrimination scores (U = −4.7, P<0.01), with those who were aware of the campaign being significantly more likely to report higher levels of discrimination.

Anticipated discrimination

In 2011 72% of participants felt that they had to conceal their mental health status to some extent. In 2008 the figure was 75%. A Mann-Whitney test revealed that the difference between 2008 and 2011 was not significant. Additionally, a Mann-Whitney test revealed a clear but non-significant improvement in how far participants stopped themselves trying to initiate a close personal a relationship in 2008 and 2011 (54% in 2008, 54% in 2009, 43% in 2010 and 46% in 2011).

Discussion

The proportion of people using mental health services who experienced no discrimination increased over the course of Time to Change by 2.8%, which is less than the target of 5%. At the same time the overall median of discrimination ratings fell significantly by a remarkable 11.5%. Nevertheless, these changes cannot be directly attributed to the TTC programme, especially as there is only one baseline point in 2008 so it is not known if or how experienced discrimination was changing before this. Although the results show an improvement in most areas from 2008 to 2011, for a few of the life domains we found an increase in discrimination between 2010 and 2011 (data not shown). This is consistent with results from surveys on discrimination against people with physical disabilities. 13 Additionally, these findings are clearly consistent with data from the Attitudes to Mental Illness survey (see Evans-Lacko et al, this supplement Reference Evans-Lacko, Henderson and Thornicroft14 ) and our study of newspaper coverage regarding this period Reference Goulden, Corker, Evans-Lacko, Rose, Thornicroft and Henderson15 (also Thornicroft et al, this supplement Reference Thornicroft, Goulden, Shefer, Rhydderch, Rose and Williams16 ).

Although we have detected clear positive changes, it is also true that our findings across all four years show that experiences of discrimination are extremely common among people using mental health services in England. In all four years the most commonly identified sources of negative discrimination were those with whom most people have closest contact, i.e. family and friends. Reference Couture and Penn17 These are also the sources that showed the greatest reduction in discrimination experiences. This suggests a positive impact of the TTC programme when coupled with social marketing campaign evaluation data showing that those who know someone with a mental health problem have a high level of campaign awareness. Reference Evans-Lacko, London, Little, Henderson and Thornicroft18 However, as it was also found that participants with an awareness of the TTC programme reported more discrimination, it is possible that a reporting bias had an effect on the results. An awareness of TTC may also have increased awareness of discriminatory behaviour. Less positively, no significant reduction in reported discrimination from mental health professionals was found. Research suggests a number of reasons why professionals' behaviour might be more resistant to change: professional contact selects for people with the most severe course and outcome (the ‘physician's bias’); contact occurs in the context of an unequal power relationship; and prejudice against the client group is one aspect of burnout, which is not uncommon among mental health professionals. Reference Onyett19 The implications of this finding may bear upon ‘diagnostic overshadowing’, namely the provision of worse physical healthcare for people with mental disorders, and also contribute to the higher mortality rates among people with mental illness. Reference Jones, Howard and Thornicroft20-Reference Wahlbeck, Westman, Nordentoft, Gissler and Laursen22

The results related to finding and keeping a job, although improving between 2008 and 2010, deteriorated between 2010 and 2011 (data not shown) despite legislative changes in 2010 providing greater protection to people with disabilities. Reference Lockwood, Henderson and Thornicroft23 Continued efforts, such as the ‘Time to Challenge’ component of TTC, which aimed to improve awareness of mental health problems in the workplace, are needed to educate employers, employees and job candidates about the rights of employees and job candidates with disabilities. Additionally, efforts are needed to ensure that overall increases in unemployment do not disproportionately affect people with a mental health problem.

It should also be noted that stigma and discrimination can influence the outcome of a person's illness. It has been shown that a reluctance to seek help for one's mental health problem can be related to stigma. Reference Rusch, Angermeyer and Corrigan24 Additionally, a lack of treatment adherence has also been associated with stigma. Reference Thornicroft25

Strengths and limitations

The key limitation of this study is the low response rate. Following the rate of 6% in 2008, two changes were made to the 2009-2010 recruitment strategy. Despite these changes only 7% and 8% of people who received an invitation pack were interviewed in 2009 and 2010 respectively. In 2011 two further changes - an invitation letter from the participating mental health trust, and the offer of a £10 voucher for taking part in the survey - increased the response rate to 11%. A number of factors might have caused the low response rate. First, participants had to respond to the initial mailing by sending back a consent form to the research team; subsequently they were telephoned by an interviewer who would verbally confirm consent before starting the interview. Effectively this created a ‘two-step’ consent procedure that participants had to navigate. Second, the recruitment method relied on sampling through NHS trust patient databases. These databases may not have been accurate or up to date. We are aware that between 46 and 176 packs during various years were returned as undeliverable and it is likely that more were undelivered but not returned. Third, the consistently low response rate may also reflect the nature of the population, many of whom might struggle to engage with a study of this kind owing to their illness. Finally, this population (especially participants from London NHS trusts) may be asked to participate in research quite regularly and therefore may been experiencing ‘research fatigue’.

A response bias could result in overrepresentation of those with more experiences of discrimination in the sample. Although we cannot fully determine the extent to which this was the case, we were able to determine the extent to which the sample was representative of the entire population of non-institutionalised NHS mental health service patients aged 18-65 years with respect to age, ethnicity and gender. Comparison with these data shows that our sample underrepresented younger people, Black and minority ethnic groups and men, and that this was more the case in 2008 than in 2011.

In spite of the low response rate the sampling design for this study was an improvement over previous similar surveys in England, in that it was a random sample drawn from those using NHS mental health services across England, rather than from memberships of national mental health charities as has been the case previously. Further, the high reported rates of experienced discrimination were consistent with surveys using the same instrument and different data collection methods yielding higher response rates: face-to-face surveys, Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius, Leese and Indigo2,Reference Pinfold, Huxley, Thornicroft, Farmer, Toulmin and Graham26 and a postal questionnaire to people using mental health services in New Zealand. Reference Wyllie and Brown27

The results may in theory have been affected by changes to simplify the wording of the survey instrument, as a revised version of the DISC was used from 2009. The main change was that ‘treated differently, and worse’ was replaced by ‘treated unfairly’ in each item on experienced discrimination. The changes lowered the Flesch-Kincaid reading grade to level 7.4 (i.e. understandable by the average 7-8th grade student in the USA) from 13.2 (i.e. understandable by the average 13th grade student). However, subsequent validation of the DISC showed that the questions elicit similar responses. Reference Brohan, Slade, Clement, Rose, Sartorius and Thornicroft11 Further, although each question was reworded in the same way this did not result in the same pattern of change in endorsement across all items. Instead, the frequency of reporting increased for a few items and fell for the rest.

Future research

Future research will seek to delineate different types of discrimination and the extent to which these vary by source, as examples given by those interviewed ranged from being patronised, overprotected or treated like a child to being shunned, rejected or at times abused. We will also investigate how people are affected by different levels of discrimination; for example, is a reduction associated with increased access to employment and greater participation in leisure activities? The question of what a world free from mental illness discrimination would look like is critical for anti-stigma campaigns wanting to realise this vision in the future.

Funding

This work was supported by the Big Lottery, Comic Relief and Shifting Attitudes to Mental Illness (SHiFT), UK government Department of Health. C.H., E.C., S.H., D.R., P.W. and V.P. are supported by a grant to Time to Change from Big Lottery and Comic Relief and a grant from SHiFT. C.H., P.W. and G.T. are funded by National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grant for Applied Research (RP-PG-0606-1053) awarded to the South London and Maudsley National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust. D.R. and G.T. are also supported by the NIHR Specialist Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, and the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. C.H. is also funded by a grant from the Guy's and St Thomas' Charity and a grant from the Maudsley Charity.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating National Health Service trusts, the Viewpoint interviewers and Sue Baker, Maggie Gibbons, Paul Farmer, Paul Corry, Mark Davies, Dorothy Gould and Jayasree Kalathil for their collaboration.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.