1. Introduction

The present paper focuses on easy-to-read German (henceforth ETR German; in German Leichte Sprache).Footnote 1 It addresses the question ‘Is it a linguistic variety or a system, or just texts that have certain characteristics?’ (Nordic Journal of Linguistics call for papers).

Compared with the efforts for simplifying communication in other European countries such as Norway and Sweden, ETR German is a rather young phenomenon, mainly promoted by the activities of Netzwerk Leichte Sprache (= Network ETR German), who published their guidelines in 2009, and authorized by the Barrierefreie-Informationstechnik-Verordnung 2.0 (BITV 2.0) (= Accessible Information Technology Regulation 2.0), published by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs in September 2011 (see Bredel & Maaß Reference Bredel and Maaß2016:60ff. and Reference Bredel and Maaß2017:13ff. for further information). ETR German has been developed to meet the needs of people with different kinds of reading disabilities, to improve their chances to participate in various communicative practices in today’s society. It is important to note that ETR German was developed primarily on the basis of lay concepts. This means that the major guidelines emerged from the experience of people who worked with target group members such as people with learning difficulties. The guidelines do not refer to linguistic research on language comprehension and/or linguistic complexity vs. simplicity. The most prominent guidelines are the above-mentioned BITV 2.0 and Network ETR German. The guidelines are strictly normative (for example, do not use the passive voice, do not use the Genitive case, avoid negation). Although various empirical studies (see for example Bock Reference Bock2018a and Lange Reference Lange2019) have shown that such strict guidelines fail to adequately represent the various preconditions of the heterogeneous target groups and that ETR texts may diverge from the strict regulations, the guidelines have a powerful impact on ETR text production in Germany, especially in highly institutionalized contexts. The guidelines are used for processes of testing and permitting ETR texts by various authorities. Therefore, as far as the situation in Germany is concerned, we have to take two modes of ETR into consideration: the radical mode conceptualized by the above-mentioned guidelines, aiming at a maximum of plainness resp. accessibility, on the one hand, and the mode of the actual usage of fairly simple German in ETR texts on the other hand. To make it even more complicated, two variants of easy-to-read language are being differentiated in Germany: Leichte Sprache, the label for ETR related to the guidelines mentioned above, and Einfache Sprache, a less strictly defined notion for various reductions of linguistic complexity in texts (see Bredel & Maaß Reference Bredel and Maaß2016:526ff.).

After the development of ETR German, lay concepts and guidelines, and the rapid growth of their application in our society, linguistic research on ETR German has also developed quite rapidly. Linking the assumptions about easy German presented in the guidelines with the actual abilities and needs of target group members can be seen as the major concerns of German linguistic research on ETR. Thus, as mentioned above, several empirical studies on the level of difficulty of presumably relevant language phenomena for target group members have been carried out. Whereas it is broadly agreed upon that empirical research is necessary to better understand how ETR texts help target group members to participate more meaningfully in the various literate practices in our society, the status of the guidelines is controversial: whereas Maaß (Reference Maaß2015) and to some extent also Bredel & Maaß (Reference Bredel and Maaß2016) argue for putting the guidelines on a more sound linguistic basis, Bock (Reference Bock2018a) advocates replacing the strict guidelines with more flexible principles.

Due to the concentration on empirical studies in linguistic research on ETR German, theoretical issues, such as the above-mentioned question on the proposed status of ETR as a variety, a system, or a collection of texts, have not yet been discussed thoroughly (Bredel & Maaß Reference Bredel and Maaß2016 might be seen as an exception: see below). But surely, the questions posed in the Nordic Journal of Linguistics call for papers should be of major interest for the linguistic explanation of the phenomenon as such. Therefore the following article addresses the more theoretical question of how to classify ETR German within the system of language variation. The article focuses on the more restricted variant Leichte Sprache (based on the above-mentioned guidelines) because it has a much greater impact in German society than Einfache Sprache and is therefore also focused on German linguistic research. Reducing the issue of the paper to the German Leichte Sprache, the paper cannot claim to answer the discussed questions for all ETR languages.

2. ETR German within the German language

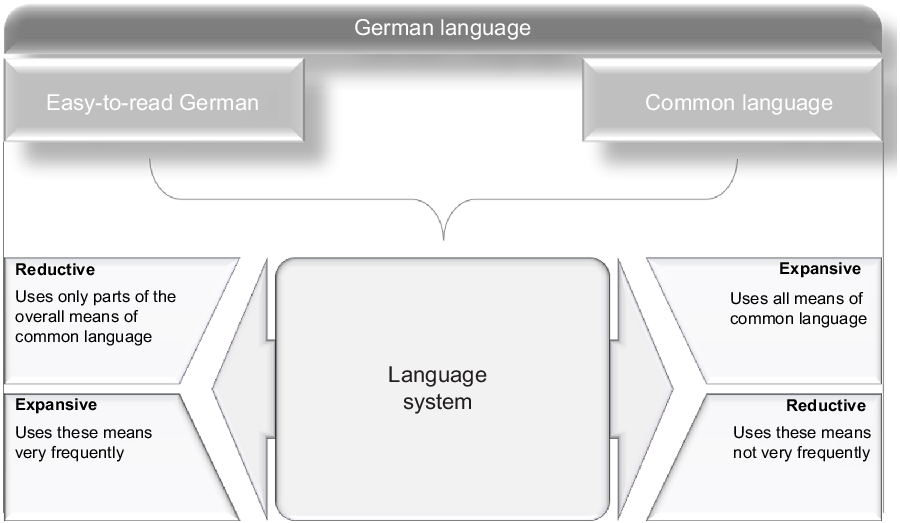

As mentioned in the introduction, ETR German is constituted by guidelines such as those of Network ETR German (2009) or BITV 2.0 (2011) which provide rules for language usage on various linguistic levels (grammar, lexicon, text, macrotypography). The rules both prescribe the use of special language phenomena considered to be simple and prohibit language phenomena considered to be complicated (for example, use positive language, avoid the genitive case and the conjunctive mode, write short sentences with only one proposition; see the guidelines by Network ETR German 2009). Rules like that refer to the system of the German language, that is, they presuppose that certain language phenomena are part of the system of the German language and they define their status for ETR German. By ruling out a certain number of language phenomena as not being adequate for ETR German, the number of phenomena used in ETR German is reduced (in comparison with common language). That means, on the other hand, that the phenomena supported by the rules are used expansively. If, for example, passive voice and simple past tense are excluded, active voice and other tenses (first of all the present and perfect tenses) will automatically be used more frequently. Figure 1 summarizes this idea.

Figure 1. Reductive and expansive use of German phenomena in ETR German.

Note: I adopt the figure from Czicza & Hennig (2011), who develop the idea of reductive vs. expansive grammar within language variation with regard to academic language. I consider the assumption of having one core system within a natural language that allows us to choose features within different variational contexts as being one major concept for the relations between the system of a natural language and different variational contexts (see Hennig Reference Hennig, Fuß and Wöllstein2018).

It is important to emphasize that this means that ETR German – at least as far as the layer of grammar is concerned – makes use of the possibilities provided by the system of the German language, that is, it does not establish an autonomous language system. We may conclude that ETR German is a special mode of usage of the German language, that can be characterized by its reductive and expansive usage of certain language phenomena compared with common language. According to Coseriu’s theory of speech (Reference Coseriu1988), this means that ETR German is characterized by features in the layer of norm, not in the layer of system (compound segmentation (Pappert & Bock Reference Pappert and Bock2019) might be seen as an exception). On the other hand, we have to take into consideration that this judgement only concerns the linguistic code of ETR German. But ETR texts are just as well characterized by visual codes such as their special macrotypography (Bock Reference Bock2020). If we deal with the question of special systematic characteristics of ETR German from a multimodal perspective, i.e. a perspective that focuses on the interaction between different semiotic codes, we might assume a special ETR subsystem.

In the following, the question will be discussed whether this ‘special mode of usage’ may be described as a variety and/or register, or whether we have to look for alternative concepts to capture the variational status of ETR German.

3. Modelling language variation and the notion of ‘variety’

In the Nordic Journal of Linguistics call for papers, the term easy-to-read language is introduced as a term that ‘refers to a modified variety of a natural language that has been adjusted so that it is easier to read and understand in terms of content, vocabulary and structure’. In German research on ETR, it is also common to classify ETR German as a variety. This also applies to Bredel & Maaß (Reference Bredel and Maaß2016), although they also discuss the limitations of classifying ETR German within the system of language variation (Bredel & Maaß Reference Bredel and Maaß2016:24ff.). I take the considerations by Bredel & Maaß as a starting point in this chapter, because they address important questions on the relations between ETR and language variation. Starting from their discussions of the status of ETR German within Coseriu’s model of language variation (Reference Coseriu1970, Reference Coseriu1988) and Koch & Oesterreicher’s model of the language of immediacy and distance (1985/Reference Koch and Oesterreicher2012), I will move on to general considerations on the relations between the notion of variety and the dynamics of language usage and language change.

3.1 ETR German within the architecture of German language variation

According to Coseriu (Reference Coseriu1970, Reference Coseriu1988), language differs with regard to the geographic space (= diatopic differences), the socio-cultural classes within the society (= diastratic differences), and the modalities of expressing content matters (= diaphasic differences). Bredel & Maaß follow the widespread custom of concluding that varieties can be classified into diatopic, diastratic, and diaphasic varieties, and discuss the question of which of the three dimensions is able to provide explanatory power to locate ETR German within the system of language variation. Unsurprisingly, they regard ETR German as related to the diastratic dimension of variation because it is only used by a certain group of people, mainly those with reading disabilities (Reference Bredel and Maaß2016:25). However, ETR is not suitable as a means for group formation (like youth language, the most frequently cited example of a diastratic variety), since it is based on an asymmetry between its producers and its recipients (ibid.). As this asymmetry also holds true for many kinds of scientific texts, Bredel & Maaß do not consider this to be an argument against describing ETR German as a diastratic variety. Apparently, they consider the notion of a non-standard variety according to Coseriu as appropriate due to its restricted range in contrast to Standard German, which Bredel & Maaß classify as neutral in usage (Reference Bredel and Maaß2016:24). On the other hand, Bredel & Maaß also systematically compare ETR German with Standard German (Reference Bredel and Maaß2016:523ff.), which establishes Standard German as a relevant point of reference for describing ETR German.

This brief discussion of the possible status of ETR German as a diastratic variety shows that language variation is much more dynamic than a classification of varieties as diatopic, diastratic, or diaphasic varieties is able to model (see also Section 3.3). Therefore the question of whether ETR German can be classified as a diatopic, diastratic, or diaphasic variety leads to a dead-end. It is a misunderstanding to assume that we use either a diastratic, diatopic, or diaphasic variety whilst speaking. If, for example, I speak to my students in a seminar at my university, my speech is at the same time influenced by the idea of how the social interaction in a seminar works (= diastratic dimension) and by our discussing special content matters (= diaphasic dimension). My accent also shows slight references to my regional origin (= diatopic dimension). Thus the dimensions of variation interact in every act of communication. The idea of chains of varieties (Koch & Oesterreicher Reference Koch, Oesterreicher, Günther and Ludwig1994) makes us aware of systematic correlations between the different dimensions of variation. For example, it is very unlikely that a scientific text carries features clearly marked as diatopically strong (i.e. features of basic dialects) or diastratically low (i.e. colloquial expressions). In contrast, in a conversation with friends from where we come from, we are quite likely to use regional language features and colloquial expressions. What makes ETR languages difficult to integrate into this is that their social and situational settings – i.e. the low diastratic and diaphasic features – would usually correlate with the usage of features of regional languages, but they do not. Rather, in ETR German diatopic language features are a priori excluded, which in the common chains of varieties usually correlates with high diastratic and diaphasic settings (for example written languages for special purposes or scientific languages). But although this might be seen as one further feature of the artificiality of ETR German, we have to note that the general abstraction from the diatopic dimension of variation is also a feature of the Standard German language. This might be the reason why Bredel & Maaß conceptualize Standard German as the basic reference point for ETR German (Reference Bredel and Maaß2016:523ff.) and describe ETR German as a reduction of Standard German. Standard German can generally be characterized by the abstraction from the dimensions of variation, i.e. equally well from the diaphasic and diastratic dimension as from the diatopic dimension of variation. If Standard German is the reference point for ETR German, the conclusion is that ETR German cannot be captured by the above-mentioned dimensions of variation.

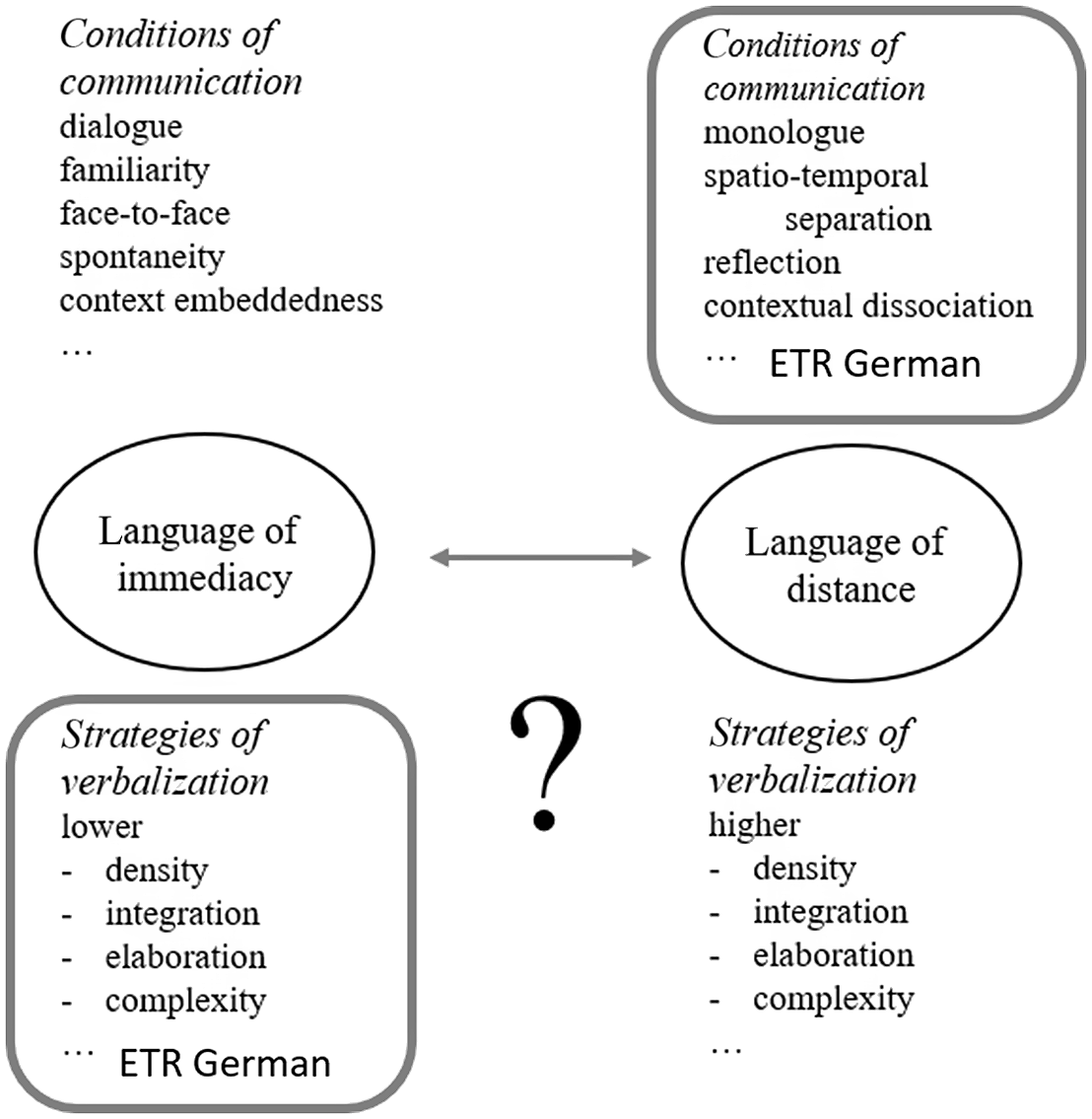

3.2 ETR German between immediacy and distance

Whereas Coseriu’s approach is often used to classify varieties due to their major variational features in German linguistics, Koch & Oesterreicher’s model of the language of immediacy and distance is popular for describing various language usage in oral and written communication. Related to Koch & Oesterreicher’s distinction between the language of immediacy and the language of distance, Bredel & Maaß reveal the following paradox: Koch & Oesterreicher model the poles of the immediacy–distance continuum by listing conditions of communication and strategies of verbalization (see Figure 2). Koch & Oesterreicher’s main concern is to show that there is a continuum between the two poles, that is, text types or instances of texts do not have to be either examples of language of immediacy or language of distance, so that there are transitional and hybrid forms as well (for example personal letters, which are written but also show features of immediacy, or lectures, which are spoken but carry features of distance). Surely it should be assumed that the two components of explanation – the conditions of communication and the strategies of verbalization – interact, that is, certain conditions of communication can be expected to lead to certain strategies of verbalization, although Koch & Oesterreicher do not elaborate these relations (for their modelling see Ágel & Hennig Reference Ágel and Hennig2006, Hennig Reference Hennig, Franco and Sieberg2011). Bredel & Maaß show that this does not apply to ETR German: due to the conditions of communication, ETR German can be considered to be a language of distance, because a high degree of planning is demanded and the reception should work without regard to the situation (Reference Bredel and Maaß2016:30f.). On the other hand, ETR German can be characterized by strategies of verbalization such as lower complexity or density of information: see Figure 2.

Figure 2. The paradoxical status of ETR German as a language of distance due to the conditions of communication and a language of immediacy due to the strategies of verbalization.

Note: The figure uses a simplified depiction of the Koch & Oesterreicher model. See Koch & Oesterreicher (1985/Reference Koch and Oesterreicher2012) for the model with all relevant conditions and strategies and the consequences for the location of text types between the poles of immediacy and distance.

Bredel & Maaß conclude that ETR German has neither the structure of the language of immediacy nor the structure of the language of distance (Reference Bredel and Maaß2016:31). To my mind, this conclusion questions the status of ETR German as a variety, since any natural variety ought to systematically interact with the dimension of immediacy and distance as Koch & Oesterreicher have modelled with their notion of ‘chains of varieties’ (Reference Koch, Oesterreicher, Günther and Ludwig1994) (see Section 3.1). Since in ETR German the natural relations between the conditions of language usage and the usage of certain language forms are being suspended, it seems difficult to capture its variational status by linguistic concepts outlined for describing natural languages.

3.3 The notion of ‘variety’ and the dynamics of natural languages

Although the two above-mentioned approaches are very prominent for modelling language variation in German linguistics, and Bredel & Maaß deliver a thorough discussion, I consider it necessary to turn back to the general question of how to define a variety and how to model language variation. In German linguistics, the term variety is commonly used to describe subsystems of the German language. There is broad agreement on describing varieties as subsystems within a natural language that are characterized by certain language features, which are related to extralinguistic conditions (see for example Elspaß Reference Elspaß, Neuland and Schlobinski2018:93). The notion of a variety has mainly been promoted by sociolinguistics. I quote Berruto as a prominent actor in this field, who defines variety as follows:

Wenn eine Menge von gewissen miteinander kongruierenden von sprachlichen Variablen … zusammen mit einer gewissen Menge von Merkmalen auftreten, die die Sprecher und/oder Gebrauchssituationen kennzeichnen, dann können wir eine solche Menge von Werten als eine sprachliche Varietät bezeichnen. (Berruto Reference Berruto, Ammon, Dittmar and Mattheier1987:264)

(If a certain amount of coinciding linguistic variables occur together with a certain amount of features characterizing the speaker and/or the situation of language usage, then we can refer to such an amount of values as a linguistic variety.)

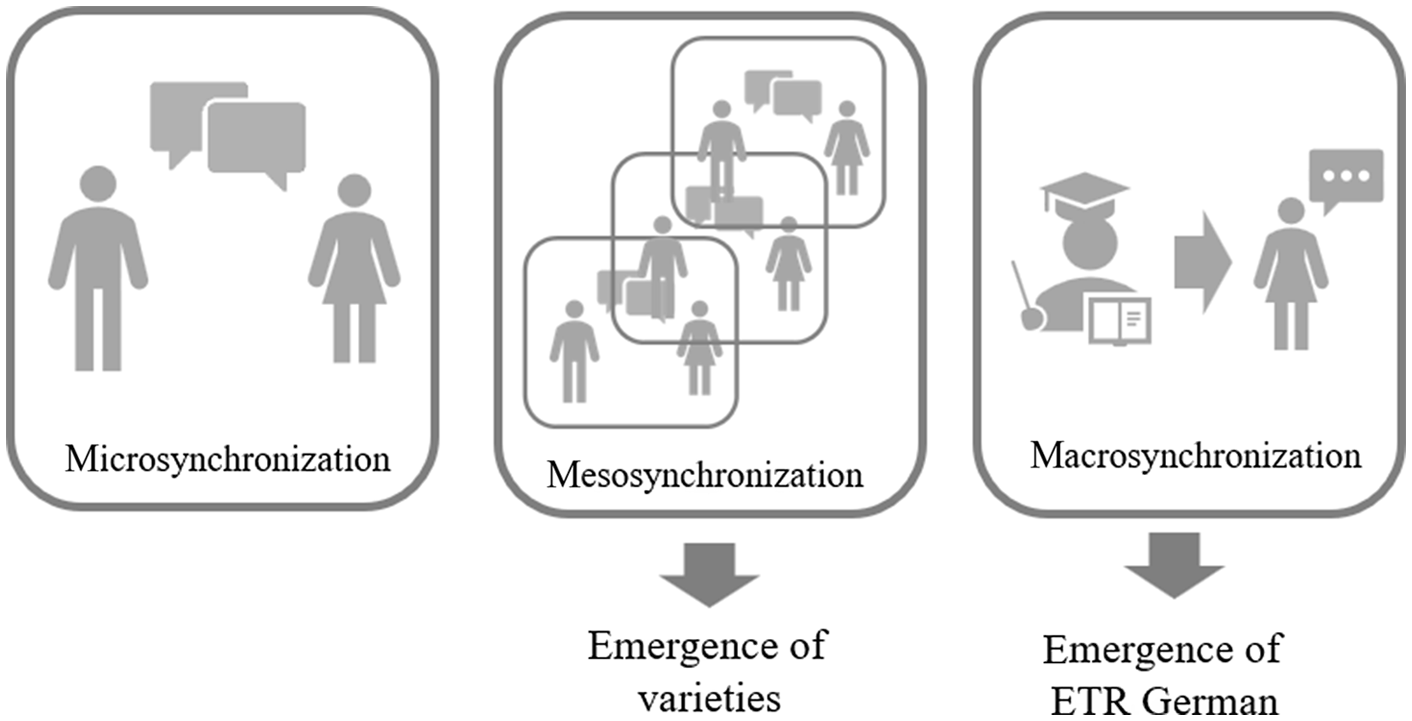

Berruto himself points out that it is very difficult to quantify the number of features necessary in order to speak of a variety. As far as ETR German is concerned, this should not be the problem: ETR German contains a well-defined number of linguistic features. As far as their functionality is concerned, ETR features are undoubtedly related to the situations of ETR usage. The confusion starts if one considers the correlation with the speaker as an indispensable criterion for calling a certain language usage a variety: ETR features are not fully functional with respect to the producers of ETR texts, but only to their recipients. Producers of ETR texts do of course use the features in order to make them functional for the situations of ETR usage. But the production of a kind of language that falls far below their own language competence and which does not even correlate with their own usage of language in colloquial, non-professional situations, makes them a type of participant that cannot be compared with any kind of participation in language discourse. In other contexts where text producers use linguistic features that are simpler than their usage of language in other situations (the production of textbooks by scientists may be used as an example, or the way teachers speak with their students), the production of utterances that seem adequate for the particular recipients is carried out by the producer’s intuitive understanding of simplicity rather than by the producer’s compliance with a set of predefined rules of simplicity: the producers choose language features because they consider them to be functional for their purposes, not in order to follow the rules by special guidelines. Thus the process of production of more simple utterances in situations like these can be classified as an act of microsynchronization, whereas the orientation towards a norm of simplicity in the production of ETR texts must be seen as macrosynchronization (see below).

On the other hand, the notion of variety is itself not straightforward. Within their theory of language dynamics, Schmidt & Herrgen (Reference Schmidt and Herrgen2011) criticize the assumption of homogeneity that results from many established notions of modern linguistics such as the distinction of synchrony and diachrony (Reference Schmidt and Herrgen2011:21ff.). Furthermore, Schmidt & Herrgen point out that approaches that take the variability of language into account also tend to end up in the homogeneity trap if they classify varieties as static modes of languages: if varieties are conceptualized as homogeneous subsystems of a language, the inadequate notion of a homogeneous competence is duplicated (Reference Schmidt and Herrgen2011:21). To make this problem more concrete: it has often been pointed out that we cannot speak of the youth language or the language for a special purpose, since in fact language also varies within the respective variational contexts. This is the case because language users do not just reproduce a restricted number of variational patterns. We do not just produce our notion of language for a special purpose if we communicate in a special field and we do not always use the same level of dialect independently of whom we talk to. We adopt our language usage to the particular situations of interaction and to our understanding of what kind of language will be appropriate in addressing our respective communication partner. Schmidt & Herrgen call this process ‘synchronization’, which they define as the adjustment of differences in competence within acts of language performance (Reference Schmidt and Herrgen2011:28). Schmidt & Herrgen differentiate between micro-, meso-, and macrosynchronization. Microsynchronization means the individual synchronization processes in individual interactions (Reference Schmidt and Herrgen2011:29). Schmidt & Herrgen define mesosynchronization as a sequence of aligned acts of microsynchronization (Reference Schmidt and Herrgen2011:31), that is, they speak of mesosynchronization if several similar acts of microsynchronization can be amassed. Macrosynchronization, however, cannot just be seen as a further degree of abstraction; instead Schmidt & Herrgen conceptualize macrosynchronization as acts of synchronization where the participants are guided by a common norm (Reference Schmidt and Herrgen2011:32). Schmidt & Herrgen name the emergence of Standard German and the establishing of an orthographic norm as examples of processes of macrosynchronization.

I refer to Schmidt & Herrgen’s ideas, because they provide a model that exceeds the notion of variety: language usage is far too dynamic to be adequately classified by well-defined varieties. On the other hand, linguistics will never be able to describe every single act of microsynchronization. Scientific approaches depend on abstraction and classification. Thus the notion of variety may yet be helpful and should not be removed from our set of linguistic categories. But we should see variety as a methodologically motivated simplification that helps us speak about different modes of language usage.

Within Schmidt & Herrgen’s model the notion of variety is most closely related to the level of mesosynchronization, which is responsible for the emergence of linguistic conventions specific to certain groups and situations (Reference Schmidt and Herrgen2011:31). It is the dynamics of the mesosynchronization process that Schmidt & Herrgen consider to be a more adequate linguistic view on language variation than defining static varieties with well-defined boundaries. If we follow the assumption of Schmidt & Herrgen that dynamics is always fundamental for language variation, Bredel & Maaß’s attempt to capture the special character of ETR German by calling it a static variety (Reference Bredel and Maaß2016:531) must be seen as a contradiction in itself. The dynamic process of mesosynchronization ought to be relevant to the emergence of any kind of mode of language usage that in other linguistic contexts would be called a variety (or a register, style, practice: see below). Now, what is striking about ETR German is that its emergence cannot be fully explained by the concept of mesosynchronization: see Figure 3.

Figure 3. The special status of ETR German as a result of macrosynchronization.

Surely, the emergence of ETR German can partly be considered a sequence of communication acts in which the producers explore options of making themselves understandable to their recipients, and that certain conventions and patterns of an easier German stabilize in their repeated usage in a sequence of similar situations. But, as mentioned above, ETR German is conceptualized to a high extent by its guidelines. As the guidelines constitute a norm, the usage of ETR German is – at least partly – a matter of macrosynchronization: we can speak of macrosynchronization as long as a speaker or writer reflects the norms relevant for his or her production of utterances. The systematic orientation towards an established set of rules makes ETR German different from the wide range of varieties such as dialects or sociolects. As pointed out by referring to the creation of an orthographic norm as an example of a process of macrosynchronization in German, language change cannot only be seen as a bottom-up phenomenon of stabilizing mesosynchronization acts, but it can also be established by top-down macrosynchronizations. But the correlation of macrosynchronization and the notion of a variety which is restricted to a well-defined group of participants seems rather unusual.

3.4 Is ETR German a ‘variety’?

In the discussion of various approaches towards modelling the notion of variety, the following criteria have been worked out as significant for classifying a mode of language usage as a variety.

-

– Varieties are part of a natural individual language. As such they underlie the dynamics of language variation and change and emerge via processes of mesosynchronization, i.e. as a sequence of aligned acts of individual synchronization processes in individual interactions.

-

– Varieties can be classified by dimensions of variation, such as the diastratic, diaphasic, and diatopic dimensions. Although all the named dimensions influence any individual speech act, individual acts of communication might be classified as instances of diastratic, diaphasic, or diatopic variation if they show particularly salient features of one of the dimensions.

-

– Varieties correlate with other varieties within a chain of varieties.

-

– Varieties possess a certain number of features characterizing the speaker and/or the situation of language usage. That means that varieties are characterized by systematic form–function correlations.

-

– Individual communication acts of any variety of a natural language can be localized between the language of immediacy and the language of distance. That means that they show certain strategies of verbalization which can be derived from certain conditions of communication.

If we consider these characteristics as definitional criteria for a variety, we have to come to the conclusion that it is not adequate to classify ETR German as a variety.

4. Modelling language variation and the notion of ‘register’

Therefore it might be helpful to discuss the applicability of other models of language variation for ETR German as well. By taking a closer look at the notion of register as another model of language variation, I will move on to the second part of the question posed by the current call of the Nordic Journal of Linguistics: ‘Is it a linguistic variety or a system, or just texts that have certain characteristics?’

The notion of register is currently a very prominent notion for describing and modelling language variation. What makes it complicated is that the notion of register is used in different research contexts with different approaches and definitions. I cannot claim to consider all relevant approaches. I will instead mention a small choice of different approaches and then move on to the discussion of the applicability to ETR German within one of them.

The concept of register plays an important role in approaches that focus on the social and cultural dimensions of language variation. For Agha, for example, ‘registers are cultural models of action that link diverse behavioural signs to enactable effects, including images of persona, interpersonal relationship and type of conduct’ (Reference Agha2006:145). Agha understands register as a social concept, since ‘the register range of a person may influence the range of social activities in which that person is entitled to participate’ (Reference Agha2006:146). Therefore, in Agha’s outline of the notion of register, the sociohistorical perspective systematically interacts with the repertoire perspective (i.e. the repertoire involved in shaping a register) and the utterance perspective. In this approach ‘register’ is closely related to the notion of ‘social practices’.

A prominent approach within German linguistics is the notion of register within the modelling of orality and literacy and formal and informal language, by Utz Maas (Reference Maas2010, Reference Maas, Feilke and Hennig2016). Maas differentiates formal, informal, and intimate registers by assigning to them the following domains: institutional regulation (literary language), official situations such as the place of work, and family and friends (Reference Maas, Feilke and Hennig2016:96). Maas uses the notion for modelling the development of language skills within language acquisitions (towards a differentiation of registers).

4.1 The notion of ‘register’ by Douglas Biber (and Susan Conrad)

I will now take a closer look at the notion of register by Douglas Biber, since his register approach seems to have an enormous impact on current linguistics, which might be due to its close relation to the currently influential corpus linguistics (see below). Biber’s notion of register is therefore to a high extent adapted to surface characteristics of registers.

Also, in the textbook written together with Susan Conrad, Biber & Conrad (Reference Biber and Conrad2019) classify register as a ‘text variety’, which leads to the assumption that their register approach might be appropriate for discussion of the NJL question of whether ETR languages are ‘just texts that have certain characteristics’. Biber & Conrad use the term text ‘to refer to natural language used for communication, whether it is realized in speech or writing’ and the term variety ‘for a category of texts that share some social or situational characteristic’ (Reference Biber and Conrad2019:5). Starting from this definition, Biber & Conrad differentiate between dialects as ‘varieties that are associated with different groups of speakers’ and registers ‘that occur in particular situations of use’ (which also holds true for genres and styles) (ibid.). Comparing these definitions with the approaches discussed in the previous section, there seems to be an obvious link between Biber & Conrad’s notion of dialect and the diastratic dimension of variation, and their notion of register and the diaphasic dimension of variation. Thus the conclusion above, that the dimensions of variation systematically interact, naturally remains relevant even if we use varying notions while considering language variation. Therefore it seems doubtful to differentiate notions of language variation by strictly separating the groups of speakers and the situations of use: language use always depends on the systematic relations between the situation and the speakers. The notion of register – as understood by Biber & Conrad – might be helpful in order to take a closer look on the situational factors that have an effect on language variation, but it will not provide an overall modelling of language variation. The situational factor is without doubt important for capturing the special character of ETR German. Thus ETR languages are – as the term itself indicates – mainly used as written languages. Although certain attempts to make use of ETR German in oral communication in Germany can be observed – such as radio features in ETR German or the usage of plain language in oral consultations – ETR German is mainly used as a written language in situational contexts with institutional settings. On the other hand, the restriction on situational factors by Biber & Conrad might be considered as problematic in the context of the description of ETR languages, because the social groups unquestionably play an important role in the constitution of such languages.

The question now is what the register approach can offer to locate ETR German within the system of language variation. According to Biber & Conrad, ‘The description of a register covers three major components: the situational context, the linguistic features, and the functional relationships between the first two components’ (Reference Biber and Conrad2019:6). This outline does not differ much from the above-cited definition of variety by Berutto, the only difference being the already mentioned restriction to the situational context. Biber & Conrad describe the functionality as constitutive for registers: ‘When speakers switch between registers, they are doing different things with language – using language for different communicative purposes and producing language under different circumstances’ (Biber & Conrad Reference Biber and Conrad2019:12). They use this defining feature for differentiating registers from dialects as well as from styles and genres. According to Biber & Conrad, ‘register variables are functional, as opposed to dialect variables, which are conventional’ (Reference Biber and Conrad2019:11). They consider variables in dialect studies as being dichotomic whereas variables in register studies are described as scalar: ‘Linguistic variables in dialect studies almost always consist of a choice between two linguistic variants … In contrast, linguistic variables in register studies are usually rates of occurrence for a linguistic feature in a text, and a higher rate of occurrence is interpreted as reflecting a greater need for the functions associated with that feature’ (ibid.). This rather strict distinction seems to originate from a fairly traditional view of dialectology. As far as the current state of research in German linguistics is concerned, modern research on regional languages shows a deep interest in ranges of regional variation (see for example Schmidt & Herrgen Reference Schmidt and Herrgen2011 for the theoretical principles and Kehrein Reference Kehrein2012 for a case study). Thus our discussion of Biber & Conrad’s differentiation between register and dialect leads to the impression that the differentiation depends on how defining criteria are determined and interpreted.

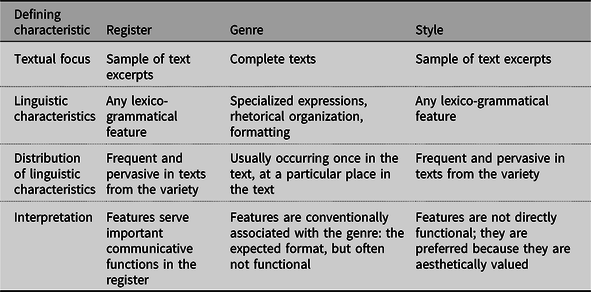

As mentioned above, Biber & Conrad also use the criteria of functionality for differentiating between register, style, and genre. In addition to register, genre and style are introduced as ‘different approaches or perspectives for analyzing text varieties’ (Reference Biber and Conrad2019:15). According to the research question proposed by the Nordic Journal for Linguistics whether ETR is ‘just texts that have certain characteristics’, the differentiation between these three perspectives on textual variation might provide interesting insights into the understanding of ETR languages. I will use Table 1 to start the discussion.

Table 1. Defining characteristics of registers, genres, and styles (Biber & Conrad Reference Biber and Conrad2019:16)

As far as the defining characteristic ‘textual focus’ is concerned, the differentiation between a sample of text excerpts and complete texts indicates a methodological perspective on ‘text’ rather than a defining criterion of textual features. We will come back to that later.

As far as the other defining characteristics are concerned, we can easily conclude that ETR texts can be explained by the notion of register rather than the notion of genre or style as they are understood by Biber & Conrad: according to this outline, genre differs from style and register in the usage of specialized expressions that usually occur only once in a text. This surely holds true for fairy tales with their specialized introductions Once upon a time in English and Es war einmal in German. On the other hand, a feature such as use of the simple past tense (instead of the present perfect) in German fictional prose is frequent and pervasive. Nevertheless, it can be registered that linguistic features in ETR texts are pervasive in general. And they certainly ‘serve important functions in the register’: they are not just preferred aesthetic features. Along with regard to the notion of register, Biber & Conrad provide a fairly restrictive meaning of genre which does not correspond to the use of this concept in sociolinguistics. Thus Spitzmüller points out that the concept of genre in modern sociolinguistics is used for social patterns of action and evaluation that govern the formation of texts and discourses due to parameters such as goals of action and social positions rather than simply categorize them based on surface features (Reference Spitzmüller2013:241). Again we have to conclude that the question of whether or not a certain notion may be appropriate for locating ETR languages within the system of language variation depends very much on how the respective notion is understood. This also holds true for the notion of style: Biber & Conrad’s interpretation of a preference of style due to aesthetic values indicates a rather narrow definition of style. Modern stylistics provides a wider range of more flexible notions of style: ‘Jede Äußerung hat Stil – in Relation zum Textmuster und zu den Umständen ihrer Verwendung [Every utterance has style – in relation to text patterns and to the circumstances of its usage]’ (Sandig Reference Sandig2006:2). Due to this understanding of style, features are indeed functional.

Now how can the notion of register be used to describe the linguistic characteristics and their functions within ETR texts? With regard to the linguistic features, Biber & Conrad distinguish register features and register markers: register features are characteristics that occur ‘more commonly in the target register than in most comparison registers’ (Reference Biber and Conrad2019:54). Register markers on the other hand are ‘distinctive linguistic constructions that do not occur in other registers’ (ibid.). Biber & Conrad conclude that ‘register markers are rare’ and therefore ‘Most registers cannot be identified by the occurrence of a distinctive register marker’ (Reference Biber and Conrad2019:57). This also holds true for ETR German. The differences between ETR German and other modes of German language usage are quantitative rather than systematic, as stated in Section 2.

And what are functions in a register and how can they be described? Biber & Conrad admit that this step of the overall analysis is open to interpretation (Reference Biber and Conrad2019:69) and thus has to be carried out inductively: ‘once the situational and linguistic analyses are completed, the functional analysis involves matching up characteristics of the two’ (Reference Biber and Conrad2019:74). But even if this step is open to interpretation, we need an overall model for functions relevant to distinguishing various modes of communication. Biber & Conrad provide a list of ‘Major functions that distinguish among registers’ and ‘Selected linguistic features associated with each function’ (Reference Biber and Conrad2019:73). The list consists of general functions such as interactivity or referring to the time and place of communication or shared personal knowledge; general communicative purposes such as narrative, description, directive, or procedural; presentation of information such as elaboration or condensation; and finally production circumstances such as real time and careful production and revision. Examples of associated features are pronouns for interactivity, past tense verbs for narrative, prepositional phrases for condensing information, and complex noun phrases and sentences for careful production and revision. Biber & Conrad describe their list as a ‘starting point for undertaking the functional interpretations’ (Reference Biber and Conrad2019:74). This quite modest classification of their own approach offered for the analysis of functions seems adequate, since the list does not provide a systematic approach to relations between functions and language variation. To describe and model functions is a much more difficult task for linguistics than to describe features visible on the surface of language usage. The modelling of functionality might be more promising if the model were restricted to one dimension, as is shown by Koch & Oesterreicher’s (1985/Reference Koch and Oesterreicher2012) model of the language of immediacy and distance, which is restricted to the variation between orality and literacy. Nevertheless, in a way it is disappointing that an approach that declares functionality to be the major key to understanding the modelled notion does not provide a more consistent model of linguistic functions. Furthermore, the ‘starting point’ list does not provide any relevant examples or ideas that give us a better understanding of how ETR languages can be explained.

Since functions of language phenomena are less feasible than the description of linguistic forms, the register approach pays more attention to the methods of describing linguistic features. Biber & Conrad advocate a comparative quantitative approach to the analysis of register (Reference Biber and Conrad2019:53ff.): assuming that register markers are rare and thus registers can be distinguished by register features as defined by the notion of frequency, it is obvious that a quantitative approach is the means of choice. Note that one of the central projects of the Collaborative Research Centre ‘Register’, currently being carried out in Berlin, is named ‘Data management and statistical analysis’ and, for instance, one of the projects on ‘register and grammar’, which deals with syntactic register variation in German, aims at developing Biber’s approach further by ‘(i) using a probabilistic approach to registers, (ii) using a more sophisticated method for automatically inferring registers from distributions of features in texts’. Unsurprisingly, the register approach is also closely linked to corpus linguistics (Biber Reference Biber2012). To avoid misunderstanding, I want to make it clear that I do not point out the relations of the register approach to corpus linguistics and quantitative linguistics because I doubt that these relations are useful or because I want to criticize the tendencies towards these kinds of linguistic approaches. On the contrary, I assume that these relations are one reason for the apparent success of the notion of register in current linguistics.

4.2 Is ETR German a ‘register’?

Whereas the discussion of the applicability of the notion of variety to ETR German leads to the conclusion that ETR German cannot really be classified as a variety because it does not fulfil the criteria compiled from various approaches, we are confronted with a different picture with regard to the notion of register: register seems to be a term for a wide range of notions which are too different to amount to a coherent picture of one clearly focused notion of language variation. Therefore the question of whether the notion is applicable to ETR German can only be discussed with regard to individual approaches. I chose Biber & Conrad’s approach due to its current popularity and to their focus on text variation.

Admittedly, the last section provided a critical discussion of Biber & Conrad’s notion of register rather than a thorough application to ETR German. As a theoretical approach, Biber & Conrad could not convince me due to their attempt to make clear distinctions between concepts such as dialect, register, style, and genre by arranging relevant parameters such as function and situation in a distinctive model. Such a clear-cut model is surely attractive in a way, but it neglects the existing research traditions.

As a methodological approach to the analysis of larger quantities of texts, the register approach could serve as a reference point for research on ETR languages. The methods applied in the register approach could support access to ETR languages that concentrates on the mesosynchronization processes, that is, processes of conventionalizing language phenomena proven to meet the needs of easy-to-read texts. As far as the research on ETR German is concerned, it is highly influenced by the strong impact of the ETR guidelines and has therefore promoted empirical research on phenomena sanctioned by the guidelines by the members of the target groups. Corpus studies on the usage of these phenomena in ETR texts have also been carried out (see for example Lange Reference Lange2019 on the genitive case or Rocco Reference Rocco2021 on clause linking). For a more neutral view on how simplicity is displayed in texts that are supposed to be easy to read (as for example carried out by Lange Reference Lange2018), it might be helpful to make use of the methods proposed by the register approach.

5. Conclusions

Making use of two highly prominent concepts of language variation has proved useful with respect to arriving at general explanatory features that might lead to a better understanding of the linguistic status of ETR German. However, none of the consulted approaches provide simple answers on the question of whether ETR German is a variety, a system, or just a collection of texts. I do not expect that the search for other explanatory approaches will lead to more concise results. Rather, the difficulties in capturing the functioning of language variation with clear-cut definitions and concepts described in this article arise from the dynamics and complexity of language variation as such on the one hand and the special performance of ETR German on the other hand.

ETR languages are special modes of individual languages created for the special needs of special target groups. The features of ETR languages can be linguistically examined by analysing ETR texts. Written texts can be seen as the major manifestation of ETR languages, since attempts to use ETR principles in oral communication are comparably sparse. But the fact that texts do play an important role in the realization of ETR languages does not mean that ETR languages can only be described as a phenomenon of language usage and that they are just a collection of texts. Rather, ETR languages aim at a systematic mapping of language features used for the intended functionality. But this also does not mean that ETR languages are autonomous language systems, although they might dispose of special systematic features that are restricted to the respective ETR language. They mainly and systematically make expansive and reductive use of the core systems provided by the related individual languages. Describing ETR languages as systematic modes of individual languages implies that they are comparable to such notions as variety or register. From a heuristic point of view it might be seen as useful to classify ETR languages as varieties or registers because these are the most common concepts for special modes of individual languages in current linguistics. With regard to ETR German, Bock (Reference Bock, Feilke and Wieser2018b) also proposes applying the concept of practice. This might provide interesting insights into the social settings of ETR languages, since the concept of practice derives from sociology and cultural sciences. The concept of variety, on the other hand, can be seen as a research tradition that has always concentrated on thoroughly describing the linguistic features of the various modes of individual languages. The concept of register – as outlined by Biber & Conrad and used in modern corpus linguistics – has its strength in providing a methodological framework for analysing language features. And both approaches offer ideas of how to explain the use of these features in terms of their functionality for their usage in certain social and situational settings. In its sociolinguistic meaning, the concept of register provides a framework for understanding the social indexicality of language stereotypes and is related to the notion of social practices. Therefore there is no reason not to use the explanatory tools by the major approaches on language variation for analysing the status of ETR German or other ETR languages within the system of language variation. But we should see notions such as variety or register as explanatory frameworks and/or heuristic aids rather than as notions with defining criteria that unrestrictedly hold true for ETR German.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Bettina Bock for her comments on an earlier version of this paper. Thanks are also due to two NJL referees, whose comments have been very helpful. Finally, I also thank Viveka Velupillai for proofreading.