INTRODUCTION

Violence against children and older women is endemic in most contemporary African communities worldwide (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2017; Cimpric Reference Cimpric2010; Gorman and Petersen Reference Gorman and Petersen1999). A report produced by the Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General on Violence Against Children reveals that “[e]very year, between 500 million and 1.5 billion children worldwide endure some form of violence” (United Nations Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Violence Against Children 2015:1). According to a report released by the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) in 2014, globally, approximately 1 billion (i.e. six in 10) children between the ages of 2 and 14 years are regularly physically mistreated by their caregivers and communities. It also discloses that about 120 million teenage girls worldwide have been sexually assaulted at some stage in their lives. The UNICEF report and other studies indicate that the prevalence rates are considerably higher in sub-Saharan African countries than in other parts of the world (Pereda et al. Reference Pereda, Guilera, Fornsa and Gómez-Benito2009; UNICEF 2014a, 2014b). It has also been disclosed that in 2012 alone, about 95,000 young people below the age of 20 years were victims of homicide, and that children living in sub-Saharan Africa are at higher risk of being victims of such crimes (UNICEF 2014a, 2014b). Indeed, child mistreatment, as the African Child Policy Forum (ACPF) notes, is a significant problem throughout the African continent, occurring “in the home and family, schools, care and justice systems, workplaces and the community” (ACPF 2014).

Violence against older women is also widespread yet mostly hidden. “It occurs in multiple, often intersecting forms by perpetrators who may include intimate partners, family members (including male and female adult children), caregivers or members of the wider community.” (HelpAge International 2017:2) Elderly people tend to be marginalised throughout Africa; they face hardship because of the contemporary society’s negative attitudes towards them (Apt Reference Apt1996; Kabole, Kioli, and Onkware Reference Kabole, Kioli and Onkware2013; Mba Reference Mba2007). As Mba rightly observes, the “changing social conditions have left elderly people disadvantaged and vulnerable to mistreatment” (Mba Reference Mba2007:230; Pillay and Maharaj Reference Pillay, Maharaj and Maharaj2013:12). Even though there is a lack of reliable data or statistics on the prevalence of violence against elderly people, particularly women in Africa, it has been suggested by various experts and activists that about 50% of the estimated over 60 million elderly folks in sub-Saharan Africa have been subjected to some form of abuse and violence (Pillay and Maharaj Reference Pillay, Maharaj and Maharaj2013; UNFPA and HelpAge International 2012:110), including discrimination, banishment, isolation or rejection, stereotyping, physical assault or torture, and barbaric executions (Kabole et al. Reference Kabole, Kioli and Onkware2013:78).

Disturbingly, a considerable proportion of the mistreatment mentioned above and violence perpetrated against children and older women in Africa is triggered by certain superstitious beliefs, particularly witchcraft (Cimpric Reference Cimpric2010; International NGO Council on Violence against Children 2012; Mgbako and Glenn Reference Mgbako and Glenn2011; Spence Reference Spence2016). In many cases, to be labelled a witch, as Gerrie ter Haar rightly observes, “is tantamount to being declared liable to be killed with impunity” (ter Haar Reference Ter Haar and Haar2007a:18). In Ghana, the belief in witchcraft and the malicious activities of witches is widespread. Suspected witches are held responsible for all kinds of calamities, including inexplicable illnesses and untimely deaths, as well as a series of unexplained misfortunes in a family or the community, and are consequently persecuted (ActionAid 2012; Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011, Reference Adinkrah2017; National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE) 2010).

Unfortunately, although children and older women endure all forms of witchcraft-driven abuse, the subject has not received the attention it deserves in the academic literature. Thus, systematic and critical analyses of the impact of witchcraft accusations on crimes in Africa in general, and Ghana in particular, by social and behavioural scientists are lacking. Besides, there is a lack of data on its magnitude or prevalence, primarily because surveys are not set up to capture this information in the first place. Therefore, a lack of data translates into a lack of effective and realistic prevention programmes (or protection mechanisms) and limited support services for victims. Therefore, to fill the literature gap, the present study establishes the magnitude and identifies the principal features, motivations, and social and cultural contexts of witchcraft-driven mistreatment of children and older women in Ghana. The study also explores appropriate ways through which the venomous spell emitted by this ubiquitous superstition could be neutralised. The study first introduces key witchcraft concepts and historical development, and a summary of how this has been linked to abuse and violence in African countries, particularly Ghana. The second part then succinctly describes the main approach/method utilised to gather data and realise the study’s aim. The third part presents the results of an in-depth analysis of witchcraft-related abuse cases published on the websites of three renowned local Ghanaian media outlets between 2014 and 2020 and a critical discussion of the results. The final part explores and proposes appropriate and practical steps that could be taken to control or curtail the witchcraft-related abuse of vulnerable groups in Ghana and other African countries.

WITCHCRAFT AND CRIME IN AFRICA

The belief in witchcraft and the existence of witches and wizards is, unarguably, the most dominant harmful superstition in Africa (Cimpric Reference Cimpric2010; Evans-Pritchard Reference Evans-Pritchard1937; Quarmyne Reference Quarmyne2011; Tebbe Reference Tebbe2007). According to Kate Crehan (Reference Crehan1997) and Jill Schnoebelen (Reference Schnoebelen2009), witchcraft belief is an inescapable part of everyday life in the region; it is held by all manner of people – the uneducated and educated, the poor and rich, the old and young. The terms “witchcraft” and “witch” mean different things in different countries and to different ethnic groups, tribes or communities in Africa (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004:335; Niehaus Reference Niehaus2012; Quarmyne Reference Quarmyne2011:477; Tebbe Reference Tebbe2007:190). As Cimpric (Reference Cimpric2010:11) notes, “[t]he notion of witchcraft possesses a multifaceted semiology, referring to a wide variety of representations and practices, which further vary not only within a country but also according to different socio-cultural groups”. Evans-Pritchard (Reference Evans-Pritchard1937) defines witchcraft simply as the use of innate, inherited supernatural powers to control people or events or cause misfortune or death. Roma Standefer maintains that witchcraft beliefs “constitute a system for the personification of power and evil” (Standefer Reference Standefer1979:32). A witch, according to Robert Alan LeVine, is thus “a person with an incorrigible, conscious tendency to kill or disable others by magical means” (LeVine Reference LeVine, Middleton and Winter1963:225). Closely related to this definition is that of Nelson Tebbe, who describes a witch as someone “who secretly uses supernatural power for nefarious purposes” (Tebbe Reference Tebbe2007:190). To Standefer, a witch is “a person who is thought capable of harming others supernaturally through the use of innate mystic power, medicines or familiars” (Standefer Reference Standefer1979:32). Based on the above individual definitions and descriptions, witchcraft can conceivably be defined, in most African countries, “as the ability to harm someone through the use of mystical power. Consequently, the witch embodies this wicked persona, driven to commit evil deeds under the influence of the … force of witchcraft.” (Cimpric Reference Cimpric2010:1–2) Thus, in almost all African countries, witches are generally viewed as entities who possess extraordinary malevolent spiritual powers and whose intentions are almost always to do evil against others (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004; LeVine Reference LeVine, Middleton and Winter1963; Tebbe Reference Tebbe2007).

One of the first experts to present a detailed analysis of witchcraft’s concept and historical development within an African setting is Evans-Pritchard (Reference Evans-Pritchard1937). After conducting an ethnographic study among the Azande of Sudan, he concluded that though harmful, witchcraft belief, when its basis is properly understood, constitutes logical explanations for unfortunate events (Evans-Pritchard Reference Evans-Pritchard1937). His assertion seems to be supported by Henrietta Moore and Todd Sanders, who claim that “[f]ar from being a set of irrational discourses, … [witchcraft and the occult in Africa] are a form of historical consciousness, a sort of social diagnostics” (Moore and Sanders Reference Moore, Todd, Henrietta and Sanders2001:20). Evans-Pritchard’s (Reference Evans-Pritchard1937) approach was to interact with and interrogate the people and challenge their beliefs rather than merely observe their actions. This approach enabled him to gain more authentic information and a greater understanding of the witchcraft belief in an African community. However, as one commentator observes, his study was conducted at a time (i.e. 1920s) when the Azande social structure and viewpoints were beginning to undergo significant transformation due to British rule (Gracie Reference Gracie2017). Hence, the findings may not entirely conform to the people’s concept of witchcraft today. As Comaroff and Comaroff (Reference Comaroff, John and Comaroff1993), Geschiere (Reference Geschiere1997) and Meyer (Reference Meyer1999) note, the concept of witchcraft in Africa is no longer “traditional” but operates as a significant aspect of “modernity”.

As the prototype of all evil, purported witches are blamed for all kinds of misfortunes and calamities (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004; Cimpric Reference Cimpric2010; Evans-Pritchard Reference Evans-Pritchard1937; Spence Reference Spence2017). It was previously believed that an “enlightened” religion, education, advancement in medicine or science and technology, urbanisation, modernisation, and better social conditions would help dispel or discourage witchcraft beliefs and associated violence (Cimpric Reference Cimpric2010; Parrinder Reference Parrinder1958). However, “[f]ar from fading away, these social and cultural representations have been maintained, transformed and adapted, according to contemporary realities and needs” (Cimpric Reference Cimpric2010:6).

Ipso facto, descriptions of the magnitude of witchcraft belief and its associated violence in African societies by some observers and social scientists have been exceedingly exaggerative and sensational. For instance, describing the degree of the prevalence of witchcraft among the Mbugwe of Tanzania, Robert F. Gray states that “[t]he number of witches in Mbugwe … is commonly estimated at half the population and this would be a conservative estimate, considering that witches are supposed to transmit the art to all their children” (Gray Reference Gray, Middleton and Winter1963:143). Even though a recent survey shows that Tanzania indeed has the highest rate of witchcraft belief in Africa (Pew Research Center 2010), it would be an over-exaggeration for anyone to suggest that over half the inhabitants of a particular community in the country are believed to be witches. Writing about her travels in West Africa, and the scale of witchcraft-driven crimes in the region between the 1890s and early 1900s, Kingsley (Reference Kingsley1901:315) asserts that “[t]he belief in witchcraft is the cause of more African deaths than anything else. It has killed and still kills more men and women than the slave trade. Its only rival is perhaps the smallpox.”

However, Meyer Fortes (Reference Fortes1949), writing about his experiences with the Tallensi of Ghana (also a West African country), paints a quite different picture. He notes that witchcraft belief “occupies a minor place in Talle mystical thought and ritual action … they have no clear notion of witchcraft, no detail theories of its mode of operation and no institutionalized means of combating or sterilizing it” (Fortes Reference Fortes1949:32). A similar observation is made about the Ibo of Nigeria by another commentator who writes that “although Ibo communities share common beliefs, most of them are little troubled by fear of witches … most Ibo areas are singularly free from fears of witchcraft and witchcraft persecutions and purges” (cited in Mesaki Reference Mesaki1995:168). After closely studying the Dinka of South Sudan, Godfrey Lienhardt (Reference Lienhardt1951:303) cautions that “[t]he signalling of witchcraft for attention may create the impression that it is more prominent as a feature of Dinka society than is the case”, insisting that “one could understand much of their social structure without reference to it [(witchcraft)]”. Appraising witchcraft beliefs among the Nandi of Kenya, Huntingford (Reference Huntingford, Middleton and Winter1963:181) also discards the portrayal of African societies as being witch-ridden, noting that “witchcraft is hardly ever mentioned in ordinary talk” and the absence of the mention of it is so obvious that a stranger is likely to be deceived into thinking that there is no witchcraft in Nandi at all. It is further observed that witches hardly get persecuted in Nandi society (Huntingford Reference Huntingford, Middleton and Winter1963).

Scholarly accounts of witchcraft and witchcraft-driven violence in Africa present a confusing picture of the phenomenon’s reality in the region. It is apparent that witches are marginal in the system of beliefs of certain African societies and that some anthropologists and observers have exaggerated in their narrations. However, despite the exaggerations and discrepancies, one cannot dispute that witchcraft beliefs pose a significant danger to society, particularly for vulnerable groups such as children and older people in contemporary Africa. Startling accounts of witchcraft-related crimes have been reported and documented all over Africa (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011; Cimpric Reference Cimpric2010; Spence Reference Spence2017; ter Haar Reference Ter Haar2007b). The barbaric murders of people accused of witchcraft by the mob, witchdoctors, religious leaders and family members are frequent occurrences (ter Haar Reference Ter Haar2007b). Since many witchcraft-triggered killings are not reported, exact figures are lacking; however, “it is generally agreed that the number of people, mostly elderly women, who have been murdered on charges of witchcraft during the last three decades is in the tens of thousands in Africa” (Federici Reference Federici2010). In May 2008, at least 15 women were tortured and killed by a mob in the Kenyan region of Kisii alone on suspicion of being witches (Schnoebelen Reference Schnoebelen2009). Tanzanian government statistics indicate that between 1998 and 2001, 17,220 women, mostly older women, were attacked on witchcraft allegations; and that 10% of the attacks ended in murder (Duff Reference Duff2005; Schnoebelen Reference Schnoebelen2009).

According to Niehaus (Reference Niehaus, Henrietta and Sanders2001), an estimated 389 executions of suspected witches were carried out in Limpopo Province of South Africa between 1985 and 1995; and ter Haar (Reference Ter Haar2007b) notes that between 1996 and 2001, more than 600 alleged witches were murdered in the same province. Cimpric (Reference Cimpric2010) asserts that in January 2009 alone, about 22 persons were tortured and killed following witchcraft accusations by local traditional healers in Lobaye in the Central African Republic. It is reported that since the early 1990s, witchcraft accusations have shifted from older women to children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the treatment of alleged child witches has become increasingly violent (Aguilar Molina Reference Aguilar Molina2006; Human Rights Watch 2006). Advocates estimate that more than 60% of the 25,000 children in Kinshasa’s streets have been driven away from home due to witchcraft allegations, making it the primary cause of neglect and homelessness among children (Irish Times 2006; Schnoebelen Reference Schnoebelen2009). Considering the hugeness of the African continent and the fact that the terms “witchcraft” and “witches” mean different things in different countries and to different ethnic groups and communities in Africa, it is important to now focus attention only on Ghana in a bid to understand the subject of witchcraft belief and its associated abuse and violence in Africa.

Witchcraft Beliefs in Ghana

The relevant primary literature demonstrates that witchcraft belief is rife in Ghana. A survey involving 1,500 respondents conducted in the country between December 2008 and April 2009 by Pew Research suggests that 52% of Ghanaians believe in witches and witchcraft (Pew Research Center 2010). However, a higher percentage of witchcraft believers in the country was reported in a similar survey carried out by Gallup (Tortora Reference Tortora2010). The Gallup survey, which was also based on face-to-face interviews with about 1,000 people aged 15 years and older, indicates that approximately 77% of Ghanaians believe in the existence of witches and witchcraft. It has been suggested that the significant discrepancy in the results of the two surveys may be down to the significantly different approaches employed. Thus, Gallup surveyed people aged 15 years and older, while Pew’s respondents were 18 years and above; there is also the issue of differences in the wording of the question posed, context, and where and how respondents were selected (Tortora Reference Tortora2010).

The results of a study conducted by the NCCE are consistent with those of Gallup. The survey involving 310 alleged witches and 230 “non-witch” respondents in various communities in the northern part of Ghana showed that approximately 89% of people surveyed believe in witchcraft (NCCE 2010). Interestingly, of the 310 alleged witches who were interviewed in the NCCE study, 47.4 % said they believe in witchcraft, with 22 of them admitting that they were, indeed, real witches (NCCE 2010). If the four different results are put together, the average figure or rate for belief in Ghana’s witchcraft would be about 66%, which is a fairly high rate. The most important thing here, however, is that all four surveys, except the one among alleged witches, provide convincing proof that the majority of people in Ghana, including highly educated folks, do believe in the existence of witches and witchcraft. As Knud Knudsen notes, witchcraft belief is so widespread in the country that if people fall ill, consulting a witchdoctor or traditional spiritualist is their first choice, not a physician (cited in University of Stavanger 2010).

Understanding witchcraft-driven violence or crime in Ghana, as Mensah Adinkrah opines, “requires intimate familiarity with Ghanaian witchcraft beliefs” (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2017:53). Therefore, a reasonable description of the most striking features of witchcraft beliefs and practices in Ghana must be provided. The Ghanaian understanding of witchcraft and a witch is not significantly different from the general perception highlighted above. In a study conducted by the NCCE on Witchcraft and Human Rights of Women in Ghana, 150 respondents, who were randomly selected, were asked to provide their views as to what witchcraft means. Interestingly, 129 (approximately 89%) defined it essentially as the use of spiritual or mystical powers by certain people to harm or to kill others (NCCE 2010).

One common notion among Ghanaians is that witches operate at night and can transform into either invisible, flying entities or a ball of fire (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004:335, Reference Adinkrah2011; Bannerman-Richter Reference Bannerman-Richter1982; Debrunner Reference Debrunner1978). They are also believed to be capable of transforming themselves into various deadly animals to harm people (Bannerman-Richter Reference Bannerman-Richter1982; Debrunner Reference Debrunner1978). Even though some witches are believed to be good (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011; Dovlo Reference Dovlo and Haar2007), the general conception among Ghanaians is that witches are the embodiment of evil and that witchcraft is used chiefly for malicious purposes (Bannerman-Richter Reference Bannerman-Richter1982; Debrunner Reference Debrunner1978; Sarpong Reference Sarpong1974). It is also believed that witches belong to malevolent groups that celebrate nocturnal feasts during which members must occasionally offer human sacrifices (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004; Ametewee and Christensen Reference Ametewee and Christensen1977; Sarpong Reference Sarpong1974). Ghanaians believe that witchcraft may be an inherited/acquired art – handed down from parents to children, an art requested or learned from others, or something bought from other people (NCCE 2010; Nukunya Reference Nukunya2000; Sarpong Reference Sarpong2002).

The Ghanaian perception and depiction of witchcraft and witches are so vicious and terrifying that every evil and calamity that cannot be rationally explained is attributed to witchcraft. As Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2004), Bannerman-Richter (Reference Bannerman-Richter1982) and Debrunner (Reference Debrunner1978) assert, untimely deaths, suicide, motor vehicle accidents, AIDS, snake bites, psychiatric disorders, poverty, alcoholism, sexual impotence, leprosy, miscarriages, sterility, business downturns and divorce, among others, may all be attributed to malevolent witchcraft. Witchcraft accusations are based on mere suspicion, leading to rumours or gossip circulating within the community (Bannerman-Richter Reference Bannerman-Richter1982; Quarmyne Reference Quarmyne2011). Such rumours and accusations usually begin following a single serious misfortune such as an unexpected death or a series of unexplained misfortunes in a family or the community (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011). Mere bad dreams may also trigger suspicion and accusation. As Sarpong (Reference Sarpong1974:47) mentions, in some Ghanaian societies, “to dream that you are being chased after by cows is a clear indication that the witches are after you. Nightmares in general are supposed to be the doing of witches.” When a person sees a known individual attacking them in their dream, and the victim (i.e. the attacked person) falls sick shortly after the dream, accusations might be made against the “culprit” by the victim or the parents of the victim. Thus, a person named by a hallucinating sick person in a feverish state could easily be a victim of witchcraft accusation (Drucker-Brown Reference Drucker-Brown1993:533).

Anybody (whether male or female, young or old, rich or poor) can be a victim of witchcraft accusations and witchcraft-driven crime in Ghana (Bannerman-Richter Reference Bannerman-Richter1982; Debrunner Reference Debrunner1978). However, it is well documented that people accused of being witches and persecuted in Ghana and many other African countries are most commonly older women and children (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011, Reference Adinkrah2015; Cimpric Reference Cimpric2010; Spence Reference Spence2016). Section 3.3 of the Ghana National Ageing Policy 2010 notes that elderly people “are accused of being the cause of everything that evades the understanding of family members, and women in particular are often falsely accused of witchcraft and violently assaulted and tortured in some cases”. This corroborates Adinkrah’s observation that in Ghana, witchcraft allegations against elderly women are so common “that it is almost impossible to find a Ghanaian who does not know of an elderly woman in his or her community who is suspected of being a witch” (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004:336). Various propositions have been put forward to explain why witchcraft accusations are usually directed at women and children in Ghana.

Amoah (Reference Amoah, Diana and Jain1987), Kwame Gyekye (Reference Gyekye2003) and Samantha Spence (Reference Spence2017) suggest that Ghanaian women generally occupy an inferior or a lower social status compared with their male counterparts in practically every sphere of social life; and this may significantly explain why they are among the worst victims of witchcraft accusation and anti-witchcraft violence. Adinkrah argues that “female overrepresentation among suspected and accused witches [in Ghana] is traceable to deeply held misogynistic attitudes and gynophobic beliefs, which are the effects of patriarchal arrangements and ideology embedded in the society” (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2015:271); he thus views witchcraft-driven violence against women as a form of gender discrimination (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004). This view is supported by Amoah (Reference Amoah, Diana and Jain1987) and Spence (Reference Spence2017), who insist that gender discrimination and inequality are commonplace within Ghanaian society.

Some experts have also suggested that men perpetrate witchcraft-related violence against women to preserve or maintain male cultural dominance and superiority. They argue that the significant socio-economic and cultural changes that the current generation is experiencing, and the ongoing campaigns by activists and the international community for equality and women emancipation and empowerment, significantly threaten the age-old male cultural superiority (Drucker-Brown Reference Drucker-Brown1993; Spence Reference Spence2017). These campaigns and economic necessity have encouraged women in Africa to work harder, travel and trade to provide for themselves and their families and not rely entirely on men as before (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004). Such developments threaten men’s position as the superior gender; therefore, witchcraft accusations and witch hunts are employed as a way of suppressing the growing authority and economic autonomy of women (Drucker-Brown Reference Drucker-Brown1993).

Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2011:750) mentions that “there appears to be a diminution in witchcraft accusations against women while accusations against children appear to be on the rise”. Traditional Ghanaian communities place a high premium on childbearing (Sarpong Reference Sarpong1974; Wiafe Reference Wiafe2008). However, ironically, despite the high regard for childbearing or fertility, children in Ghana, as Adinkrah notes, “occupy a subordinate social status vis-à-vis adults in virtually every domain of social life” (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011:743). Various experts have advanced various theories to explain why a significant proportion of witchcraft accusations and witchcraft-driven violence is directed at children today. One plausible explanation is that children in the country currently do not have proper support from advocacy groups to champion their cause (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011:750).

Another explanation is the fact that children are easy targets. Criminological research shows that targets of crime are often vulnerable victims (Daigle Reference Daigle2017; Hough Reference Hough1987). As a result of their disadvantaged condition (e.g. disability, illness, youthfulness), these are folks who cannot defend themselves against their accusers. Children thus become perfect targets for witchcraft-related abuse due to their fragility and inability to repel physical assaults physically (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011). Another reason stems from the widespread belief that witchcraft is largely inherited or handed down from parents to their children; and that a baby may be a witch even before it is born (Sarpong Reference Sarpong1974). It is therefore assumed that the probability of a child being a witch is high. Such children (children who inherit witchcraft) and some other witches may not be conscious of their malevolent powers. Therefore, the fact that people are genuinely unaware that they are witches does not necessarily mean that they are not witches (Sarpong Reference Sarpong1974); they may not be conscious of their witchcraft potency. This, perhaps, explains why children accused of witchcraft are still persecuted even after flatly denying the allegations (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011). Both older women and children are probably targeted because they are easy prey.

Several studies have demonstrated that children and older women accused of being witches in Ghana are commonly those who are already vulnerable (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011, Reference Adinkrah2017; Spence Reference Spence2016). Adinkrah notes that children branded as witches ranged in age from 1 month old to 17 years old, are primarily from poor backgrounds, and live in rural areas (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011). Various studies suggest that children accused of witchcraft include those with extreme anti-social behaviours; children with disabilities; children whose births are viewed as abnormal (i.e. those born prematurely); children whose parents died just after their birth or who have lost one or both parents; children whose families experienced some form of calamity soon after their births; those who exhibit unusual or challenging behaviour; and those gifted (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011; Bruce-Lockhart Reference Bruce-Lockhart2007; Cimpric Reference Cimpric2010; International NGO Council on Violence against Children 2012; Sarpong Reference Sarpong1974).

Stubborn and aggressive children and those with albinism are also likely to be accused of witchcraft (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011). Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2004) and Spence (Reference Spence2017) note that older women with peculiar physical deformities or abnormalities, wrinkled facial skin, and emaciated bodies, as well as those with yellowish or reddish eyes, no teeth or fewer teeth, sagging breasts, stooped or hunched posture, and facial hair, among others, are particularly susceptible to witch accusations. Older women whose behaviours are regarded as eccentric (i.e. those who mutter to themselves), and those regarded as chatty, inquisitive and cantankerous, are also vulnerable to the witch label (Bannerman-Richter Reference Bannerman-Richter1982; Gray Reference Gray2000).

Magnitude of Witchcraft-Driven Mistreatment of Children and Elderly Women in Ghana

Several empirical studies have suggested that witchcraft-driven violence against children and older women is widespread in Ghana (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011; NCCE 2010; Roxburgh Reference Roxburgh2016). They have shown that some of the common forms of mistreatment resulting from witchcraft beliefs in the country are: murder, physical torture or degrading and inhumane treatment, unlawful banishment, forcible confinement and enslavement, deprivation of education, child labour, child neglect, discrimination, and deprivation of necessities of life (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011; NCCE 2010; Roxburgh Reference Roxburgh2016). Roxburgh vividly expresses the gravity of witchcraft-related violence in the country in the following words:

The killing of accused witches is quite prominent in Ghana. Accused witches are frequently subjected to ridicule, ostracism, assault and torture, exile and murder. Family members may seize an accused witch’s property, and social privileges such as access to communal foods, water, and land may be limited. As there are no formal means for addressing witchcraft attacks or suspicions, the progression of suspicion to accusation is often rapid and severe. These murders are also highly visible within society. (Roxburgh Reference Roxburgh2016:vi)

In a qualitative study that sought to establish the correlation between witchcraft belief and violence in Ghana and the non-violent “means for mediating the threat of witchcraft attack”, Roxburgh found that the so-called mob justice against suspected witches is a common phenomenon in the country; and it is often viewed by witchcraft believers “as the last defence against a world which is increasingly uncontrolled and uncontrollable” (Roxburgh Reference Roxburgh2016:i). Roxburgh’s findings were based on semi-structured face-to-face interviews with 25 heads of relevant state institutions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), religious organisations and local communities (i.e. chiefs and other traditional authorities), as well as 2 months of informal discussion with various individuals, including victims and culprits of witchcraft-related abuse and violence. The study revealed that accused people, who are mostly older women, are made to undergo torturous rituals such as exorcism regularly to cleanse themselves of witchcraft power or the stain of witchcraft accusation.

Following an investigation into the link between child abuse/mistreatment and witchcraft accusations in Ghana, Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2011) found that witchcraft-related violence against children is triggered largely by seemingly inexplicable illnesses, untimely deaths, and financial hardships; and perpetrators are mostly relatives and caregivers. This finding is very consistent with that of Cimpric (Reference Cimpric2010), who, in an anthropological study, analyses the diversity, complexity and harmful consequences of superstition and the belief in witchcraft in sub-Saharan Africa. Besides interviewing experts, Adinkrah’s (Reference Adinkrah2011) study also examined 13 cases of child witch hunts appearing in the Daily Graphic between 1994 and 2009. In an earlier study that focused on witchcraft-related murders concerning gender discrimination, Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2004) found that witchcraft-related female homicide is a common phenomenon in Ghana; and that the status of women in African society is crucial in developing an understanding of witch-related femicides in Africa. These findings were based on the analysis of newspaper reports and semi-structured interviews with some law enforcement personnel. The extant empirical studies demonstrate that perpetrators of witchcraft-triggered abuse and violence are mostly young males, who are family members of the victims (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011; NCCE 2010; Roxburgh Reference Roxburgh2016). Since the types of abuse and violence resulting from the belief in witchcraft are very many, it has been considered reasonable to discuss them here under just two main categories – lethal violence (murder) and non-lethal mistreatment.

Lethal Violence

The existing studies suggest that murder, the mother of all criminal acts, is unfortunately a common result of witchcraft belief in Ghana (Roxburgh Reference Roxburgh2016); and the worst victims of such a barbaric act are children and older women (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011). In his study published in 2004, Adinkrah identified 13 witchcraft-triggered murder cases in Ghana between 1995 and 2001. The study reveals that witchcraft-driven murders in Ghana are committed by various methods, including beatings with blunt objects (such as sticks and pieces of timber), stoning, shooting with a firearm, cutting or slashing with knives or machetes, and forcing suspects to drink poisonous concoctions in a purificatory ritual. It also establishes that the murders of alleged witches are fuelled by the assailants’ desire to eliminate the source of their suffering for good, alleviating them of the calamities that beleaguered them and allowing them to live a problem-free existence. According to the study, another motivation is revenge – where attackers seek to avenge the demises of family members, friends or neighbours assumed to have been caused by the alleged witch (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004).

In the study that analysed 13 cases of child witch hunts (involving 18 victims) appearing in the Daily Graphic between 1994 and 2009, Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2011) found that two cases involved murder. In one case, a 26-year-old woman who believed that her 4-year-old niece was a witch and responsible for her predicaments in life, including her inability to give birth to more children, locked up the little girl in a tiny bedroom and inflicted multiple knife wounds on her, resulting in her untimely death (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011). In another case, a couple refused to obtain the required medical treatment for their severely ill 9-year-old son on a spiritualist’s orders. The spiritualist had made them believe that the boy was a wizard (male witch) and that his ailing condition was a symptom of spiritual torment associated with his witchcraft (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011).

In the study by Roxburgh (Reference Roxburgh2016), two men, during a group discussion involving respondents, confessed to playing a part in putting an accused witch to death. They narrated that a close friend dreamt of a female neighbour biting him on the arm, and when he woke up, there were teeth marks on his flesh. Thus, the youth in the area confronted the woman with the so-called evidence (i.e. the teeth marks on their friend’s arm), demanding a confession. When she refused to confess, the youth had her lynched. The two respondents discussed their involvement in this barbaric crime not because they were remorseful but because they felt they did nothing wrong for killing a “witch” – the epitome of evil. Their attitude and lack of sympathy for alleged witches reflect those of the majority of witchcraft believers in Ghana (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2017).

Non-Lethal Mistreatment

In almost all the 13 child witch hunt cases (involving 18 child victims) that Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2011) analysed, the accused witches and wizards were physically brutalised and tortured. He reports that torture was employed to force confessions from the children about unpleasant events or occurrences in the family or the community attributed to them by spiritualists and pastors (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011). Adinkrah’s study further found that some alleged witches were not only deprived of food and other necessities of life but were also confined and isolated from social and physical contact with others. It is reported that three child witch hunt victims were held in dungeons for up to 8 years. In one case, an epileptic girl who was accused of being a witch was confined by her family to a tiny dark room with the family’s chickens and goats for 8 years. She was only occasionally fed with table scraps and only periodically bathed. In another instance, two young girls, 12 and 14 years old, who had been accused of being witches were, upon the orders of a pastor, brought to a local prayer camp where they were severely whipped with canes as part of an exorcism ritual intended to cast out the witchcraft powers they allegedly possessed (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011). There was also another case in which a 44-year-old woman who had been influenced by her pastor to believe that her 7-year-old nephew was a wizard (male witch) responsible for her mother’s untreatable ailments, persistently force-fed the poor boy a mixture of human excreta and urine to coerce him to confess to being a malignant wizard responsible for his grandmother’s plight (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011).

Mention must also be made of a case in which police arrested two male pastors of a local Pentecostal church for subjecting three children to a traumatic and torturous ordeal apparently to exorcise them of evil spirits. The victims (a boy and two girls aged 11, 6 and 4 years old) had accompanied their parents to the “holy” place for worship. However, during the so-called prophesy segment of the service, the children were accused of being witches and subjected to a torturous procedure, ostensibly to exorcise them of the alleged witch spirits. Each of the three victims was forced to kneel and hold up a piece of cement block in their palms while being lashed with brooms and canes by the pastors (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011). The findings by Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011) are consistent with studies conducted by the NCCE (2010) and Roxburgh (Reference Roxburgh2016). For instance, in the study carried out by the NCCE interviewing 310 alleged witches in witches’ camps in northern Ghana, as many as 74 (23%) said that they were maltreated or tortured by their assailants, 38 (12.3%) were banished from their communities in a humiliating manner, and 20 (6.5%) were stigmatised and isolated (NCCE 2010). The study further reveals that about 225 (72.6%) of the alleged witches were forced to drink some form of concoction meant to remove the witchcraft spells and purify them (NCCE 2010).

Forcible confinement and enslavement are among the most callous abuses resulting from witchcraft beliefs. Studies have demonstrated that hundreds if not thousands of children and older women accused of witchcraft in Ghana have been compelled to live in isolated shrines and witches’ camps (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011; Mgbako and Glenn Reference Mgbako and Glenn2011; NCCE 2010). Alleged witches in the southern part of Ghana may be kept in fetish shrines for long periods, apparently to be cleansed by the fetish priest or spiritualist. In Adinkrah’s (Reference Adinkrah2011) study, two children accused of witchcraft in the southern part of Ghana were detained at a fetish shrine for 16 days against their will. However, in the northern part of the country, the commonest place where accused witches are housed are witches’ camps. Witches’ camps are dilapidated settlements (largely mud huts) in mainly the northern part of Ghana where people, usually women and children, suspected or accused of being witches seek “refuge” after being banished from their homes and villages. Most accused witches go there to avoid being lynched by neighbours or the mob in their community (ActionAid 2012; Whitaker Reference Whitaker2012). Accused persons settle in witches’ camps to be “cleansed” by tindanas, individuals believed to possess supernatural powers and who claim to have the ability to exorcise an accused witch (ActionAid 2012). Alleged witches who find themselves in these camps are virtually cut off from the outside world (ActionAid 2012).

Until the latter part of 2014, there were at least seven well-known witches’ camps in the northern part of the country: Gushegu, Gambaga, Gnani-Tindang (Ghani), Kukuo, Nabuli, Kpatinga and the Bonyase witches’ camps (ActionAid 2012; Whitaker Reference Whitaker2012). It has been revealed that the witches’ camps, which “offer poor living conditions and little hope of a normal life”, are home to around 800 women and 500 children, and most of these victims have no formal education (ActionAid 2012:3; Holmes Reference Holmes2016; NCCE 2010). These “outcasts” live in unhygienic and uninhabitable camps (NCCE 2010). According to the NCCE’s study, over 77% of the 310 alleged witches surveyed in the witches’ camps are women (NCCE 2010); and the condition of the camps is exceedingly appalling – extremely overcrowded, no electricity, no healthcare services, inadequate water and toilet facilities, and poor sanitation, among others. It was found that about 54 (17.7%) of the respondents (the alleged witches) had lived in the wretched camps for 1–3 years; 58 (18.7%) had been there for 3–5 years; 114 (36.8%) had spent 5–10 years there; 41 (13.2%) had been there for 10–20 years; while 23 (7.4%) had lived in the camps for over 20 years (NCCE 2010). Interestingly, 278 (89.6%) of the alleged witches interviewed wanted the camps to be maintained. Their reason was that it is a safe haven for them, protecting them from mob attacks (NCCE 2010). The NCCE study also shows that more than half of the 310 accused witches interviewed (precisely 182) were forced to live in the witches’ camps, whereas 127 (42%) went there voluntarily to avoid been attacked or mistreated by the mob or members of the community after they had been accused.

Other witchcraft-triggered abuses such as deprivation of education, child labour and discrimination are also increasing. In Adinkrah’s (Reference Adinkrah2011) study, five of 18 children accused of being witches dropped out of school as they were unable to endure the ridicule and gossip that the witchcraft imputations generated in the community and the abuse that they suffered at the hands of school mates, peers and even teachers. The relevant existing empirical studies demonstrate that witchcraft belief is a significant cause of the rising levels of abuse and crimes perpetrated against children and older women in Ghana today. Therefore, a media content analysis was conducted to establish the extent to which the results reflect the findings of the extant empirical studies outlined above.

METHODOLOGY

To realise the present study’s aim, an in-depth analysis was conducted of witchcraft-related abuse cases or reports published on the websites of three renowned Ghanaian local media outlets between 2014 and 2020. Indeed, several academics and experts have demonstrated that in Ghana, newspapers and the electronic media are a major source of information on deviance, violence and other crimes (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011, Reference Adinkrah2019; Roxburgh Reference Roxburgh2016; Spence Reference Spence2016). Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2011, Reference Adinkrah2019) observes that Ghana’s major media houses maintain a staff of expert journalists who carry out detailed investigations into violence and criminality issues, including witchcraft-related ones. Therefore, it was appropriate to critically analyse relevant media reports to explore the scale of the abuse and violence resulting from the belief in witchcraft in Ghana. The selected local media outlets were – the Daily Graphic (a state-owned newspaper), the Daily Guide (a privately owned newspaper) and MyJoyOnline (a privately owned online news outlet).

The Daily Graphic, founded in 1950, is a reputable national daily newspaper with the largest circulation and readership (approximately 1.5 million) in Ghana (Elliott Reference Elliott2018; Hasty Reference Hasty2005; Pettersson et al. Reference Pettersson, Lindberg-Wada, Petersson and Helgesson2006). It has highly trained investigative reporters posted to every corner of the country and usually at crime scenes (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011). The quality, accuracy and depth of reporting and coverage make it the most reputable newspaper in Ghana (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2011:745). The Daily Guide (or Daily Guide Network, the name of its electronic/online version) is a well-known, well-managed and widely read daily newspaper in Ghana (Anercho Abbey Reference Anercho and Thelma2019). It is the second most popular newspaper and the largest privately owned daily in the country, enjoying a daily readership of close to 1 million, constituting approximately 18.9% of the total audience share (Anercho Abbey Reference Anercho and Thelma2019; Elliott Reference Elliott2018). It has well-trained reporters in all parts of the country and provides a detailed and accurate account of crimes, strange incidents and dramatic events. MyJoyOnline is one of Ghana’s largest and most widely patronised online news outlets, as it provides prompt, accurate and reliable account of events. What makes it even more unique is the fact that its reports/stories are usually audiovisually supported. It has an effective and easy-to-use search engine.

To obtain the relevant reports on witchcraft-related mistreatments, a search was conducted on the websites of the relevant media outlets, using key phrases: “witches”, “witchcraft”, “witches in Ghana”, “witchcraft and crime”, “witches and witchcraft in Ghana”, and “persecution of witches in Ghana”. Particular attention was paid to key information such as the number of witchcraft-triggered abuse cases reported in the selected media within the study period (between 2014 and 2020), the forms of abuse and violence perpetrated, types of weapons/tools used, gender and status of assailants and victims, victim–perpetrator relationship, and motivations for the mistreatment. Every relevant case/report was counted only once. Thus, where a case was reported by more than one of the selected media, the report that appeared to be more detailed and coherent was adopted. Where a selected report on a case was still not detailed or intelligible enough, reports on the same event/incident published by other media outlets other than the three selected ones were reviewed for a clearer and detailed description of the case.

As already noted, Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011) has adopted the content analysis technique in, at least, two of his highly informative and fascinating studies on witchcraft belief and its associated violence in Ghana. However, the key problem with Adinkrah’s Reference Adinkrah2004 and Reference Adinkrah2011 studies is that the findings are based on an analysis of reports/articles (13 in each study) extracted from just one newspaper, the state-owned Daily Graphic. The small sample size (in terms of the number of media houses involved and the number of reports/cases found and analysed for the period studied in each of Adinkrah’s two works) limits his findings’ credibility and generalisability. The content analysis conducted in the present study improves upon Adinkrah’s approach in several ways: the media sample size is bigger (i.e. 3), the media forms are varied, ownership of the selected media is diverse, and the mode of searching for relevant reports/cases is more advanced and effective (i.e. done electronically).

It is deemed important to mention that the term “child” is used in this study to refer to a person below the age of 18 years as defined by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) and the Ghana Children’s Act (1998). It must also be stressed that a generally agreed-upon definition of the phrases “older person” and “elderly person” (terms used interchangeably in this investigation) does not currently exist. The Ghana National Ageing Policy (2010) and the Ghana Statistical Service seem to strike a slight difference between the two terms, defining the former as a person aged 60 years and above, and the latter as a person aged 65 years and above (Ghana Statistical Service 2013). For this study, the term “older woman” refers to a female aged 60 years and above.

RESULTS OF MEDIA CONTENT ANALYSIS

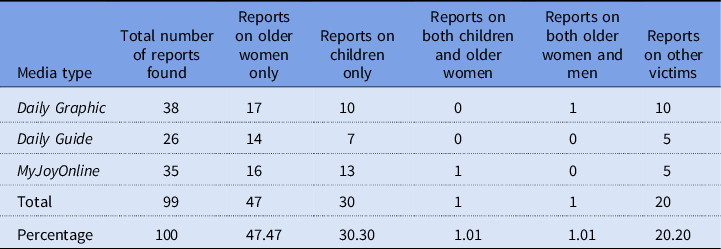

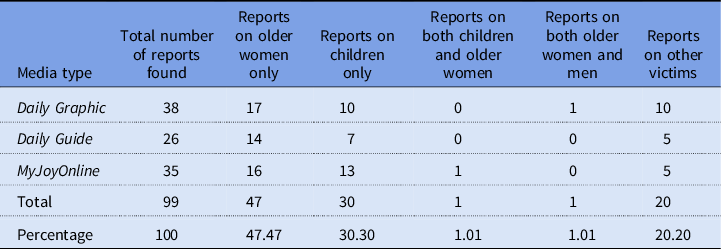

A diligent search of the three selected media websites for reports on witchcraft-driven abuse and violence, spanning the period 2014–2020, yielded interesting results. On the Daily Graphic website, 38 different reports on witchcraft-related abuse and violence were found; as many as 17 of the reports were on older women only, 10 only on children, and one on both older women and men. About 26 different cases were identified on the Daily Guide’s website; 14 were about older women only, and seven concerned just children. On the MyJoyOnline website, 35 reports on witchcraft-triggered mistreatment were retrieved; 16 concerned older women only, 12 were exclusively about child victims, and one on both older women and children. This information is summarised in Table 1. It must be pointed out that a single report or story may concern two or more victims and involve multiple forms of abuse. For instance, in one of the reports retrieved, a group of accused older people were not only physically brutalised but were also expelled from the community and compelled to live in a witches’ camp after their houses had been burnt. The 99 reports extracted from the websites of the three media outlets thus involved more than 130 victims, a little over 100 (approximately 78%) of whom were children and older women.

Table 1. The Number of Relevant Reports Found in Each of the Selected Media

As already noted, all the relevant reports/articles identified were analysed for pertinent information. The results indicate that witchcraft belief prompts physical abuse and psychological torture, and the deprivation of life necessities, including health care facilities and education. Among the major forms of abuse and violence that accused older women and children were subjected to include murder, torture, rape, beating, discrimination, banishment, forcible confinement, enslavement, child neglect, child labour, deprivation of primary education, and arson. Torture was, unarguably, the most dominant abuse resulting from witchcraft beliefs. The data show that at least seven out of every 10 witchcraft-related abuse cases in Ghana involve physical torture. In the children’s case, torture was employed largely to force confessions from them about some misfortune or unpleasant event attributed to them by pastors and fetish priests. In the case of the older women, torture was designed mainly to punish them. At least 28 of the accused witches, all older women, were murdered (22 of the killings occurred between 2014 and 2018). No child was reported murdered as a result of belief in witchcraft in any of the reports.

Most of the attacks were perpetrated by males or groups of males, usually aged between 20 and 45 years. The oldest perpetrator was in his sixties; however, his participation was minimal. The involvement of high-profile figures such as chiefs was suspected in some of the cases. In at least one instance, the police called in a local chief for questioning concerning the murder of an older woman accused of being a witch. There were only a few instances (less than 10) of women-led attacks against the victims or when women played a significant role in mistreating victims on witchcraft allegations. Most of the perpetrators (about 85%) had little or no formal education and were unemployed or experiencing financial difficulties.

The majority of the abuse and violence occurred in rural communities (particularly those in the country’s northern part). Almost all the victims, especially the older women (over 98%), had low socio-economic status and lived in poverty. There was not a single case where a well-educated and well-to-do woman was abused. Most of the attacks (about 85%) were single-handedly carried out by, led by, or involved close member(s) of the victims’ family. Sons, grandchildren, brothers and nephews were the major culprits concerning witch-related violence against older women, whereas mothers and fathers were usually complicit in the mistreatment of their own child “witches”. The dominant non-relative perpetrators were pastors and traditional spiritualists (fetish priests, witchdoctors and medicine-men).

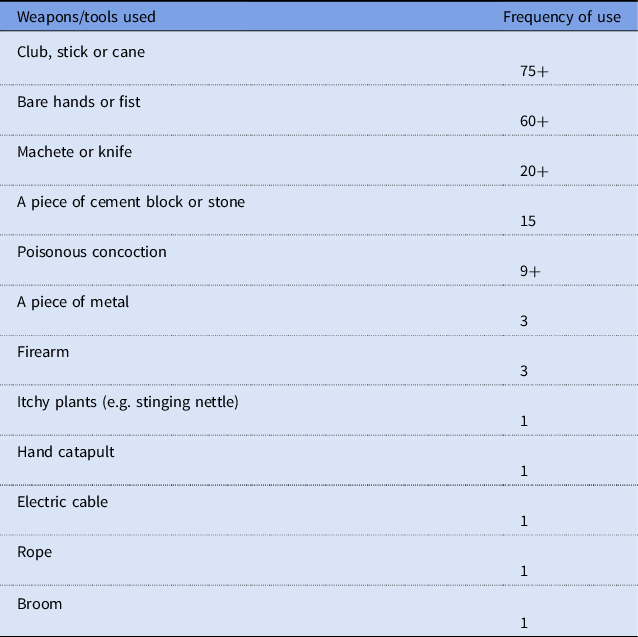

The most frequently expressed reasons or motivations for attacks or violence against children and older women were suspicion that the accused witches had used witchcraft: to cause the death or illness of a family member or someone in the community; to cause the business failure or financial problems of a supposed victim; to retard the intelligence of pupils or students in the community; to make some folks barren, impotent or childless; to prevent some individuals from getting marriage partners (spouses); to make people adopt certain destructive lifestyles such as substance (drug and alcohol) abuse; or to destroy someone’s talent or career. Three of the reports concerned women who were mistreated after being accused of being witches who had crash-landed; all the victims of the crash-landing accusation were below 60 years of age. In popular Ghanaian witchcraft narratives, crash-landings of flying witches are inadvertently aborted flights that occur while malignant witches are on their way to clandestine nocturnal assemblies or to carry out their nefarious deeds. There was no concrete evidence from the reports that any of the perpetrators suffered from a mental disorder when their transgressions were perpetrated. Various tools were used to carry out the attacks on accused witches. Table 2 shows the types of tools used for the attacks reported in the media perused and the frequency of their use.

Table 2. Types of Weapons/Tools Used and Frequency of Use

Some of the witchcraft-related abuse and violence such as forcing accused witches to drink a potentially fatal concoction (usually a mixture of alcohol, water, earth/sand and chicken blood) as part of a purificatory ceremony, forcible exorcisms, usually violent, child labour and starvation, among others, occurred in witches’ camps. However, despite this mistreatment and violence, accused witches see these dilapidated camps as a “sanctuary” that offers them protection against persecution, lynching by the mob, and other community members. Thus, despite the camps’ poor living conditions, many of the “witches” are unwilling to go back to their respective communities for fear of being killed. In other words, victims of witchcraft accusations prefer the mistreatment and the harsh conditions at the witches’ camps to the persecution and torture they would endure in their local communities if they returned or were reintegrated there. For the alleged witches, the camps are a “refuge” or a “sanctuary” not because they are not mistreated there, but because the abuse that they face is nothing compared with the extreme cruelty and violence they are subjected to in the community. Some travel on foot for three days through the bush to seek protection at the camps. The probability of an accused witch in her community being murdered is over 15 times higher than one living in a witches’ camp.

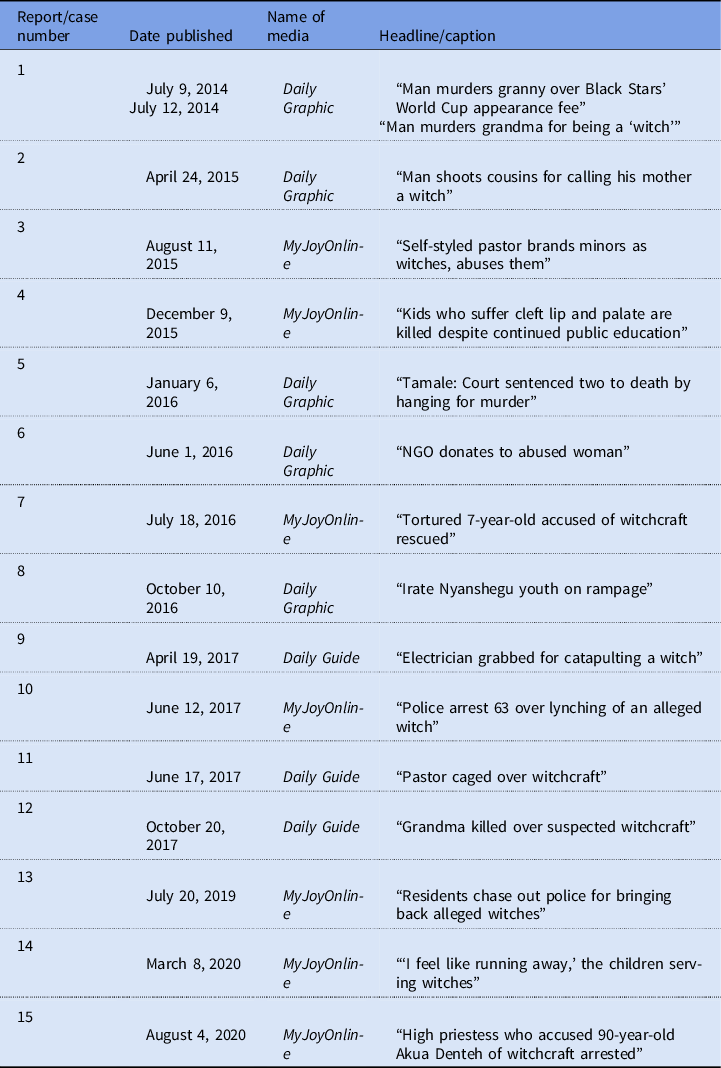

Table 3 shows the captions and summaries of just 15 of the relevant witchcraft-related abuse cases or reports identified on the three media outlets’ websites perused. The selected cases/reports provide a reasonable and clearer idea of the forms of abuse or crime triggered by beliefs in witchcraft, how often various forms of abuse and violence are perpetrated, the gender and socio-economic status of perpetrators, victim–offender relationship, the types of tools used for the attacks, and the motivations for the mistreatment. The summaries of the selected reports have been presented chronologically by the first publication date (from 2014 to 2020).

Table 3. Captions of Witchcraft-Related Abuse Stories Publicised Between 2014 and 2020

A SUMMARY DESCRIPTION OF THE ABOVE 15 CASES

Case number 1 is about a 70-year-old grandmother who was strangled to death by her grandson. The perpetrator was convinced that his grandmother was a witch who had used witchcraft to wreck his cousin’s talent as an ostensibly good footballer, resulting in him not being selected to play for the Ghana national football team, the Black Stars, at the 2014 World Cup in Brazil. The assailant was of the view that the grandmother was effectively responsible for the family’s financial predicament because if his cousin’s footballing skills had not been “destroyed” with witchcraft, he (the cousin) would have been selected to play for the Black Stars, and the family’s economic well-being or financial standing would have significantly improved since the players who participated in the tournament received huge sums of money as appearance fees. For this reason, his grandmother did not deserve to live. He first entered the victim’s bedroom and used a broom to beat her up. She managed to escape to her close friend’s house. She then returned home later that day to have some rest, but the accuser forced his way into her bedroom, strangled her to death, and fled (Aklorbortu and Tetteh Reference Aklorbortu and Andrews2014a, Reference Aklorbortu and Andrews2014b).

Victims of witchcraft-related attacks are not always the accused witches; accusers may also be subjected to severe violence, but such cases are very rare in Ghana. In case number 2, a man (who was also an Assembly Member in his electoral area) shot and killed two younger cousins and wounded another with a gun for branding his mother a witch. It is reported that on that fateful day, the shooter was in his bedroom when he was called out by his cousins to be confronted with the accusation that his mother was a witch and had used her witchcraft to make members of the family jobless and poor. The accused, who could not entertain such baseless allegations, entered his bedroom and re-emerged with a single barrel gun, which he used to shoot at his mother’s accusers, killing two and severely injuring one (Duodu Reference Duodu2015).

In case number 3, dozens of young girls, mostly between the ages of 12 and 14 years, were constantly caned by a self-styled pastor after branding them as witches. The abuse began when the pastor accused them of using witchcraft to kill some of the community’s residents. The parents of these girls who believed the pastor’s claim allowed him to consistently send them to his “sanctuary” on a hill-top under the guise of praying for and exorcising the demonic spirit from them. The deliverance or exorcism process involved severe physical abuse – pushing, dragging and lashing, leaving marks on their bodies. The girls were often forced to confess that they were witches, and the pastor badly beat up those who refused to confess. The witchcraft imputation and the ensuing mistreatment affected the girls in school, compelling many of them to discontinue their education. Some of the children told their parents about the pastor’s persistent abuse, but the parents ignored their complaints and made no efforts to report the matter to the authorities (MyJoyOnline 2015a, 2015b).

Report number 4 describes how children born with cleft lip and palate deformities in certain parts of Ghana continue to be abandoned or even killed by their parents, who believe that such children possess evil spirits and bring bad luck to the family and the community. In an interview with one journalist, the president of the Ghana Cleft Foundation, who is a senior medical expert, revealed that they (the healthcare professionals) have a child in their care whose parents have disowned or abandoned her because they believe that taking the child home would bring witches into the family and the community to cause havoc and calamity (Tawiah Reference Tawiah2015).

In case/report number 5, a 35-year-old farmer believed that his stepmother was a witch, retrogressing his progress in life (including making him jobless, poor and useless in society) with witchcraft. His persistent witchcraft accusations against the stepmother forced her to relocate from the northern part of Ghana, where she lived, to a different region in the country for a considerable period of time. However, she returned to visit the family, and, as she was sleeping, the perpetrator sneaked into her bedroom and shot her, killing her instantly. He was convicted of the murder and sentenced to death by hanging (Duodu Reference Duodu2016a).

Case number 6 concerns a 75-year-old woman accused of witchcraft and tortured by her community’s youth. Her brutal ordeal started when a fetish priest in the community accused her of witchcraft and being responsible for the death of her younger brother, who died after a short illness at age 68 years, a year before this incident. This angered the youth who rushed to her house, stripped her naked, and subjected her to severe beatings. They smeared Urtica dioica, commonly known as stinging nettle, and other extremely itchy plants all over her body, including her private parts and eyes, resulting in partial blindness. They then proceeded to set her house and farm ablaze, rendering her homeless. She was ostracised from the community and became a squatter with her daughter in a dilapidated, abandoned building near a defunct railway station. However, years later, an NGO learned of her plight and came to her aid (Daily Graphic 2016).

In case number 7, a 7-year-old girl accused of witchcraft was confined and tortured for over a month by her 34-year-old father. The father branded the girl a witch, claiming that he persistently saw “four spiritual objects” in the girl’s body whenever she was sleeping. Any time that happened, he would repeatedly hit the girl’s stomach until she fainted. According to the little girl, her father burnt her fingers with fire, stepped on her leg, beat her up with a stick, and denied her food on many occasions. He also refused to enrol her in school. Her father’s fiancée only rescued the girl after realising that her ordeal was becoming unbearable. Medical examination showed that the child had multiple body wounds (including septic wounds) and scars, swollen fingers, and multiple fractures on her left leg and arm. The frail-looking girl’s back, hands and face had a cluster of cane marks (MyJoyOnline 2016).

In case/report number 8, the houses of dozens of alleged elderly witches and wizards were burnt by some irate youth in a town in the northern part of Ghana. The youth had been made to believe by peers that certain older people in the community were witches and wizards who had cast evil spells on the community and destroyed its illustrious youth’s fortunes and future. They thus forcefully took some of the people they suspected to be witches to witchdoctors and other traditional spiritualists in the community to be exorcised. The rest were somehow dragged from their houses to the chief’s palace by the youth with the request and, in fact, demand that the chief banish them from the community. While the victims were at the chief’s palace and the residence of witchdoctors, the youth proceeded to torch their houses and destroy their property. Many of the alleged witches had no option but to run to the witches’ camps to seek refuge (Duodu Reference Duodu2016b).

In case number 9, a 36-year-old electrician who believed that his 75-year-old mother was a witch shot her with a hand catapult, damaging her right eye. The details of this case are that the attacker accused his mother of being a witch and using witchcraft to kill four of her 12 children. His persistent accusations against and harassment of the victim created a sour relationship between mother and son. On one occasion, the assailant ordered his mother to vacate her own house, threatening to kill her if she failed to comply. The victim refused to yield to her son’s threats and was sitting at her bedroom door when he shot her right eye with a hand catapult and ran off. He was later apprehended and charged with the relevant offences (Bampoe Reference Bampoe2017).

Case number 10 is about a 67-year-old woman who was gruesomely murdered following allegations of witchcraft. The assailants making the witchcraft allegation against the older woman took her to the main local chief; however, unable to find any evidence that the woman had bewitched anyone, he ordered her to go home and decided to arrange for a sub-chief to address the issue in a way that would result in peace and harmony in the community. However, unfortunately, before the sub-chief could begin the mediation process, the accusers had gone to haul her from her family home and callously stoned her to death. About 63 people were arrested in connection with the crime (Bruce-Quansah Reference Bruce-Quansah2017a; Ghanaian Chronicle 2017; MyJoyOnline 2017; Yeboah-Afari Reference Yeboah-Afari2017).

In case number 11, some community members encouraged by a pastor persistently harassed and molested three older women they suspected to be witches. The violence against the women started when a so-called man of God “prophesied” in public that the three old ladies were witches who were using witchcraft to retard the community’s progress. Based on this pronouncement, some young folks in the community decided to persecute the “evil-doers”. They dragged them to the shrine of a witchdoctor who allegedly confirmed that the three women were witches. The assailants then brought them back to the local chief, claiming that the witchdoctor had confirmed that the women were indeed witches and demanding that the chief banish them from the community. When the chief refused to banish the three women and decided to keep them in his palace, the assailants proceeded to ransack the alleged witches’ houses and bedrooms (Bruce-Quansah Reference Bruce-Quansah2017b).

Case number 12 concerned a 90-year-old woman killed on suspicion of being a witch and using witchcraft to cause family members’ deaths and other misfortunes. She had been summoned to an emergency family meeting to answer questions about the allegation that she was a witch. When the meeting did not yield the results that some of the members were expecting, they conspired to kill her to end the supposed mysterious deaths and misfortunes in the family. They tied the old lady’s hands and legs with an electric cable, placed her in a sack, and threw her into the Volta River, drowning her in the process (Kubi Reference Kubi2017).

In report number 13, two women in their seventies were accused by members of their village of being behind several misfortunes in the community, including the paralysis of a young man. They were accordingly tortured by the residents and sent to the Gambaga chief’s palace, where witchcraft suspects in the area are usually tried. To the residents’ disappointment, the chief and his council of witchdoctors declared the two accused women innocent following a trial by ordeal and ordered that they be sent back to the community. However, the angry youth and other residents refused to allow the reintegration of the two older women back into the community, insisting that the chief have them sent to the Gambaga witches’ camp instead. A group of police officers who were sent there to enforce the chief and his council’s judgment was chased out of the community by the mob who threatened to subject the two accused witches to further torture if they ever returned to the village. The two rejected women were eventually moved to an undisclosed location for their safety (Tanko Reference Tanko2019).

In report number 14, the reporter who spent months in three witches’ camps to investigate the plight of children in those establishments reveals that many of the over 400 children living in the camps he visited have been sent there to live with and care for their elderly relatives, typically grandmothers, accused of witchcraft. This is because such older women are usually frail and can hardly do any chores on their own. It is reported that a boy was sent to live with his grandmother in the witches’ camp when he was only 5 years old. Such children are compelled to abandon their education and spend ages at the witches’ camps to help their outcast grandparents. They are not only denied the right to live with their parents but are practically cast out of their homes and forced into a life of bondage and torture. The circumstances leading to the arrival of these older women and their grandchildren are heart-breaking.

In one case, an older woman was accused, together with others, of witchcraft in her native village and persistently mistreated by community members. Fearing for her life, she fled and ended up in the Nabuli witches’ camp, one of many in Ghana’s northern part. Because she was quite frail and unable to do many chores independently, someone had to be sent to live with her to help and care for her in the camp. Ironically, and quite disturbingly, her vulnerable granddaughter (who was 13 years old at the time of the reporter’s investigation) was the one chosen by her family members to go and look after her grandmother in the witches’ camp. In another case, an older woman who, in 1995, refused to attend the funeral of a family member with whom she was not on good terms found herself in a witches’ camp. Members of the community had reasoned that her absence at the funeral was an unmistakable proof that she was the one who had killed the deceased through witchcraft. In her kitchen, she was preparing dinner when a mob, wielding clubs and sticks, stormed her home and subjected her to severe beating. She had no other option than to run on foot for three hours to the Nabuli witches’ camp to seek protection. Since then, 10 different children have been sent, at different times, to live with this woman (now 87 years old) in the camp, the present “carer” being a 13-year-old girl. According to the reporter, these two stories are similar to those of many women and children in the camps.

It is also reported that nearly half of the hundreds of children found in the three witches’ camps visited by the reporter do not go to school. Some people believe that witchcraft is hereditary, so the grandchild of a witch must necessarily be a witch too; for this reason, children living with their grandparents are laughed at, bullied and mistreated in school by their mates and, in some cases, by their teachers. Many of the “witches’ grandchildren” who get the chance to go to school thus becoming dropouts. It is also revealed that some of the children are physically assaulted and raped. There is a chronic water shortage problem in most camps. In some camps, children walk for over an hour to reach and fetch water from the nearest streams, usually dirty and unhygienic. Health facilities are also non-existent in most witches’ camps; some “inmates” get bitten by snakes and never receive the treatment they need. A human rights expert revealed to the reporter that “[l]ess than one percent of all the cases … [they] deal with, in terms of witchcraft accusations and beating end up in court.” (Baidoo Reference Baidoo2020a, Reference Baidoo2020b)

Report number 15 concerns a 90-year-old woman murdered by a supposed fetish priestess and a couple of other persons in the East Gonja Municipality on suspicion of being a witch. The priestess had been invited to the community by some folks to detect and dismantle the powers of witches living in their midst and believed to be responsible for tearing into pieces the election campaign posters of a certain political party during the night. The victim was approached by the priestess who accused her of being a witch and threatened her with physical assault if she did not confess. When she persistently denied the allegation, the assailants subjected her to severe beatings, using their fists, canes and other objects, in broad daylight until she became unconscious and died. Surprisingly, none of the numerous onlookers showed any sign of disapproval, and none did anything to stop the barbaric killing (Azumah Reference Azumah2020; Duodu Reference Duodu2020; MyJoyOnline 2020).

DISCUSSION

The results from the analysis of the reports/cases extracted from the three selected media are quite consistent with the findings of existing empirical studies such as Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011), NCCE (2010) and Roxburgh (Reference Roxburgh2016). They all demonstrate that older women and children are the worst victims of witchcraft-driven crimes in Ghana. The results also forcefully confirm the claim that witchcraft-motivated crimes against children and older women are committed mostly by young males. A substantial proportion of witchcraft-driven mistreatment takes place in witches’ camps, which have existed for years, and are known by most Ghanaian adults and all relevant government institutions such as the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection, the Domestic Violence and Victim Support Unit (DOVVSU) and the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ). Thus, one wonders why very little has been done about these vulnerable groups’ plight in the camps by the relevant institutions.

Distressingly, witchcraft beliefs play a major role in the killings that occur in Ghana annually. The data show that 22 of the killings of accused older women occurred between 2014 and 2018, a disturbing development. A report about violent crime statistics in Ghana released in 2019 shows that about 2,726 murder cases were recorded nationwide between 2014 and 2018 (Tankebe and Boakye Reference Tankebe and Boakye2019:1). This, in a way, suggests that approximately 0.8% of the murder cases that occurred within the 5 years were witchcraft-related murders of older women. This is indeed a very significant figure or rate because older people (both males and females) form only 6.7% of the entire Ghanaian population (currently projected to be approximately 30 million) according to the 2010 population and housing census (Ghana Statistical Service 2013; Kpessa-Whyte Reference Kpessa-Whyte2018).

It must also be pointed out that the number of witchcraft-driven homicides identified in the three chosen media may just be the tip of the iceberg as many of such murder cases are never detected or reported. Thus, even though media reports are among the most reliable sources of crime data available in Ghana, the selected media in the present study may not have reported all witchcraft-induced murder cases in Ghana during the study period. The selected media might have published only the most dramatic cases, or cases where the death occurred instantly, not days or weeks after the incident. Again, some witch killings may have been misclassified and misreported as accidents, suicides, deaths resulting from illnesses, natural deaths or deaths resulting from undetermined causes. Such misclassifications are possible since many bodies in Ghana are not autopsied, making it difficult to determine the exact cause of death in many instances (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004). Since perpetrators of witch murders are usually family members, the victims’ bodies may be swiftly buried to avert a criminal investigation and prevent it from coming to the media and the public’s attention in general.