Introduction

Over the last decades, the proportion of childless adults has significantly increased in most European societies, after reaching a minimum in the 1935–1945 birth cohort. Demographic forecasts point to a general increase in the rate of childlessness among women born in the 1970s and 1980s cohorts (Sobotka Reference Sobotka, Kreyenfeld and Konietzka2017). It is therefore not surprising that socio-demographic research has devoted a great deal of attention to this phenomenon and its societal implications (Buhr and Huinink Reference Buhr and Huinink2017; Kreyenfeld and Konietzka Reference Kreyenfeld and Konietzka2017; Rowland Reference Rowland2007; Umberson, Pudrovska and Reczek Reference Umberson, Pudrovska and Reczek2010).

Despite the increased percentage of childless adults, the social acceptance of childlessness is still a matter of inquiry in both academia (Merz and Liefbroer Reference Merz and Liefbroer2012) and public discourse (Daum Reference Daum2015). The idea that some women and men prefer not to have children is often met with criticism by the public and mainstream media, which tend to frame parenthood in normative terms, i.e. as the only adult status with positive personal and societal implications. From an individual perspective, widespread is the claim that childlessness reflects selfish attitudes on the part of individuals, thought to opt out of raising children in favour of investing resources in themselves.Footnote 1 From a societal perspective, it is commonly held that childless adults are at higher risk of lacking socio-emotional support in later life, hence rising rates of childlessness will lead to increasing demands for public social care and health services (Plotnick Reference Plotnick2009; Wolf Reference Wolf1999).

This paper engages with the aforementioned discussions by relating childlessness to a specific domain of social life, namely intergenerational family support. By looking at childless adults from the giving side of the support chain, in this study I use data from 11 European countries to explore whether middle-aged adults (40+) with and without children differ in their propensity to provide support to their next-of-kin on the upward end of the generational lineage, i.e. their elderly parents. In addition to providing more evidence on how rising rates of childlessness and ageing populations will shape the socio-demographic outlook of the future, the motivation behind this research rests on the premise that the consequences of being childless in later life are to be assessed within a lifecourse and multigenerational framework whereby the childless are themselves active providers of resources as middle-aged adults. As I embrace a broad definition of transfers that accounts for money and assets, as well as help on daily activities and emotional support, in what follows the terms intergenerational transfers and intergenerational support will be used interchangeably.

The contribution of this study is threefold. First, I examine whether childless adults and adults with children differ in the likelihood of providing support to their elderly parents, which no prior research has heretofore addressed. In so doing, my analysis offers a descriptive account of prevalence and age patterns of upward intergenerational transfers across European countries – a relevant yet under-investigated topic of study per se (Dykstra et al. Reference Dykstra, Bühler, Fokkema, Petric, Platinovšek, Kogovšek and Hlebec2016). Second, I use cross-country data from the Generations and Gender Survey (GGS), moving beyond the convention of studying intergenerational transfers in Europe through the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). The analysis hence promotes the view that research should not be overly dependent on a single data-set, as alternative sources may help to cross-validate the accuracy of variables that are seldom collected, such as intergenerational transfers. Third, I acknowledge the importance of the issue of selection into childlessness by assessing the robustness of the findings through propensity score (PS) matching techniques.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. I first review the relevant literature – which intersects studies of upward intergenerational support across Europe and emerging research on the interplay between rising childlessness and family transfers – to derive some hypotheses before introducing the data and variables used in the analysis. I then discuss the methodology and raise concerns on the issue of selection into childlessness. Lastly, I present the results based on logistic regression and PS models, and run sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the findings. The article concludes with a discussion and limitations to be addressed in future research.

Background

Upward intergenerational support within the family in the European context

Scholars have devoted considerable attention to comparative studies on the exchange of financial transfers, help and care, as well as emotional closeness and proximity between adult family generations across European countries (e.g. Attias-Donfut, Ogg and Wolff Reference Attias-Donfut, Ogg and Wolff2005; Deindl and Brandt Reference Deindl and Brandt2011; Hank Reference Hank2007; Igel and Szydlik Reference Igel and Szydlik2011; Mudrazija Reference Mudrazija2014). These studies document that most help within the family – in kind or emotionally – is transferred between parents and their children, to the extent that what Bengtson (Reference Bengtson2001) labels as the ‘decline of the family’ still seems to be a myth. At the contextual level, public spending enables parents and children to support each other financially and with hands-on help (Kohli Reference Kohli1999). Overall, existing research shows that the state and the family work together, taking over different, complementary tasks for people in need of assistance (e.g. Attias-Donfut and Wolff Reference Attias-Donfut, Wolff, Arber and Attias-Donfut2000; Brandt and Deindl Reference Brandt and Deindl2013).

Despite the number of academic contributions acknowledging the bi-directionality of transfer flows, research on downward transfers from elderly parents to adult children continues to play a prominent role, especially when it relates to financial transfers (Dykstra et al. Reference Dykstra, Bühler, Fokkema, Petric, Platinovšek, Kogovšek and Hlebec2016). This has led to a relative shortage of studies on upward transfers, especially in more advanced societies in which the welfare state is thought to substitute for most family functions. Szinovacz and Davey (Reference Szinovacz and Davey2012) and Sloan, Zhang and Wang (Reference Sloan, Zhang and Wang2002) are important exceptions from the context of the United States of America (USA). A key reason why these transfers have been less investigated is because reality shows that private exchanges flow, on average, downwards from old to young age. Using National Transfer Accounts data from 23 economies, Lee and Donehower (Reference Lee, Donehower, Lee and Mason2011) suggest that children receive large net private transfers, typically until their early twenties, and in most societies the elderly continue to make net transfers to younger family members, at least into their seventies. Albertini, Kohli and Vogel (Reference Albertini, Kohli and Vogel2007) also document that in the European context, transfers of time and money from elderly parents to their children are much more frequent and intense than those in the opposite direction.

This study seeks to enrich the literature on upward intergenerational transfers, relying on the idea that bringing a comparative perspective to these exchanges, even if low in absolute terms, may reveal interesting cross-country variation and indirectly hint at the role heterogeneous welfare states play in different countries. Specifically, I test the hypothesis – already supported by SHARE data (Deindl and Brandt Reference Deindl and Brandt2011) – that upward family support is higher in Eastern and Western European countries, and lower in Northern European ones characterised by more generous welfare states (Hypothesis 1).

Intergenerational transfers and childlessness

Relating childlessness to intergenerational transfers may at first glance seem paradoxical, as childlessness is perceived as a ‘break’ in the direct intergenerational link (Kohli and Albertini Reference Kohli and Albertini2009). This belief, however, hinges upon the idea that family transfers within the generational lineage flow downwards from the older to the younger generations (Kohli Reference Kohli and Silverstein2004). This view yields a partial account of reality, as even transfers from childless individuals may flow upwards as well as downwards, and may not be limited to exchanges with close family members such as children.

Scholarly research relating childlessness and private intergenerational transfers is not extensive. A point that is frequently stressed, though, is the weakness of childless people's informal support networks, and the implication that the increasing number of childless people will create a rising, and likely unsustainable demand for public care services as these individuals age (Wu and Pollard Reference Wu and Pollard1998). It is not surprising, therefore, that the available literature on the topic has mostly focused on the intra- and intergenerational support childless people receive in old age (Albertini and Kohli Reference Albertini and Kohli2009, Reference Albertini, Kohli, Kreyenfeld and Konietzka2017).

Dykstra and Hagestad (Reference Dykstra and Hagestad2007) document that childless people face support deficits towards the end of life, and that the childless are more likely to be embedded in networks with limited support potential – usually a spouse or a co-resident sibling – than it is the case for parents. Deindl and Brandt (Reference Deindl and Brandt2017) assess the support networks of childless people aged 50 and over in 12 European countries, showing that informal help for childless elders is often taken over by the extended family, friends and neighbours, while intense care tasks are more likely supplied by public providers. In countries with low social service provision, therefore, childless older people are likely to experience a lack of help, especially when depending on vital care. A study for Italy also shows that, compared to parents, the childless are more likely to be helped by non-relatives and not-for-profit organisations, while only to a lesser extent by the welfare system – thus suggesting that public welfare is not able to compensate fully for informal support deficits (Albertini and Mencarini Reference Albertini and Mencarini2014).

The disproportionate research focus on the elderly childless as a group in high need of support, and the recurrent media coverage (Marak Reference Marak2016; Sodha Reference Sodha2017; Woodard Reference Woodard2014) on the social consequences of increasing rates of childlessness for future social care demands, have led to neglecting the other side of the coin, i.e. how the absence of children affects what people give. Albertini and Kohli (Reference Albertini and Kohli2009, Reference Albertini, Kohli, Kreyenfeld and Konietzka2017), Hurd (Reference Hurd2009), and Schnettler and Woehler (Reference Schnettler and Woehler2016) were among the first to shift the focal interest in childlessness and intergenerational transfers from what childless people receive to what they give to their families, friends and society at large. A shared finding of their research suggests that childless adults usually make up for the lack of own children by passing to next-of-kin, such as nephews and nieces.

Using SHARE data on the likelihood and intensity (amount) of transfers from ten European countries, Albertini and Kohli (Reference Albertini and Kohli2009) show that the likelihood of giving financial transfers and social support to non-family or family members other than children is lower for childless people, albeit still substantial. The support networks of the childless are found to be both more diverse than those of parents, and characterised by tighter links with ascendants, lateral relatives and non-relatives. Conversely, using data on the likelihood and intensity of transfers from the US Health and Retirement Study, Hurd (Reference Hurd2009) finds that childless individuals are more likely to give financial transfers to people other than their children – including their parents – and the amount of these transfers is higher compared to those given by adults with children. Having a greater need for constructing outside-family social networks, childless people may also participate more in charitable or community activities, thus contributing more than parents to society at large.

The current analysis fits within this growing literature looking at childless individuals as providers – instead of receivers – of intergenerational support, and specifically restricts the focus to transfers provided to elderly parents. Although Albertini and Kohli (Reference Albertini and Kohli2009) investigate inter vivos transfers from the childless to ascendants, descendants, lateral relatives and non-relatives, the focus of their analyses is never exclusively on transfers to parents. Hence, evidence from Europe on whether the childless transfer more to their elderly parents as compared to individuals with children remains partial or inconclusive. There are at least three reasons why focusing on transfers to parents is a sensible approach. First, members of the nuclear family typically share close and long-term bonds, with clear expectations for support and exchange (Couch, Daly and Zissimopoulos Reference Couch, Daly and Zissimopoulos2013). Therefore, as parents are the closest relatives in the generation above, there is reason to believe that the motives behind the provision of support to parents might differ from those that underlie the provision of support to more distal relatives such as uncles. Second, focusing exclusively on vertical parent–child exchanges is more directly consistent with my former claim that the long-term implications of childlessness ought to be evaluated in a dynamic multigenerational perspective. Third, following this analytical strategy I am able to assess whether Albertini and Kohli's (Reference Albertini and Kohli2009) finding of lower support on the part of the childless across European countries holds once considering support to parents only. In the alternative scenario, findings would be fully reconciled with evidence from the USA supplied by Hurd (Reference Hurd2009).

Potential mechanisms

Despite the richness of the aforementioned findings, it is challenging to advance theoretical hypotheses on whether and why the childless would support their parents differently than their non-childless counterparts. Hurd (Reference Hurd2009) claims that the transfer behaviour of the childless is in fact more complex and unpredictable, as the shift away from giving to children paves the way to a multiplicity of transfer partners and a set of substitution and compensatory mechanisms of various nature. Different scenarios underlie the testable hypothesis that adults with and without children differ in their propensity to provide upward support.

On the one hand, children are typically the primary desired target of intergenerational support for adults with children. Therefore, due to a constraint on lifetime resources such as earnings, wealth, savings and time, adults with children would have to reduce transfers to other targets – such as their parents – or reduce spending and time spent on other ‘goods’. In addition to budget considerations, following a similar ‘substitution effect’ we might observe non-childless adults who share close emotional ties with their children to have less need for strong ties with other relatives. If the need for social connections can be met by strengthening ties with children, the substitution effect would further reduce support to parents beyond the reduction operating through the budget constraint (Hurd Reference Hurd2009). Looking at the same issue from the childless angle, the childless person might have more resources to transfer (e.g. higher wealth or earnings potential), more time available outside work and stronger needs for social connections to compensate for the lack of children. An important prediction of this reasoning is that, relative to the non-childless, the childless give somewhat more to other family members, including their parents (Hypothesis 2a).

On the other hand, there is research showing that sense of independence, autonomy and ambition often characterise individuals who remain voluntarily childless (Avison and Furnham Reference Avison and Furnham2015; Houseknecht Reference Houseknecht, Steinmetz and Sussman1987). A study even noted that individuals who decide not to have children early in life are more likely to have parents who stressed achievement themselves, and to experience more social distance from their parents during adolescence, thus growing up with less desire to participate in family life as adults (Houseknecht Reference Houseknecht1979). These behavioural traits, combined with the above findings and the observation that the childless tend to participate more in community activities and other forms of civic engagement (Albertini and Kohli Reference Albertini and Kohli2009), might lead to the opposite prediction, i.e. relative to the non-childless, the childless provide somewhat less support to other family members, including their parents (Hypothesis 2b).

What follows from these hypotheses is that if complete data on earnings, wealth, savings, time use, attitudes and behavioural traits were available (together with more basic socio-demographic controls), controlling for these dimensions in a multivariate framework would make any childless/non-childless difference fade. Conversely, persistent differences after accounting for these controls would suggest that omitted factors are responsible for explaining sub-group differences, or the included variables are not properly measured. In the analyses that follow, I will assess the contribution of relevant controls available in the GGS, and speculate on the role on potentially explanatory yet missing dimensions.

Gender differences

Previous research provides insights on gender differences in upward intergenerational support given and received (Chesley and Poppie Reference Chesley and Poppie2009; Kahn, McGill and Bianchi Reference Kahn, McGill and Bianchi2011). On the giving end, Silverstein, Gans and Yang (Reference Silverstein, Gans and Yang2006) claim that adult daughters in the USA are among the most active providers of support to ageing parents, with differences with sons rooted in task specialisation, wage disparities and differences in normative attitudes towards care work. A similar finding holds in the European context, where Haberkern, Schmid and Szydlik (Reference Haberkern, Schmid and Szydlik2015) document that parents in need receive more care from daughters than from sons when the children have the same resources and live in the same circumstances (e.g. household types and living arrangements). Daughters are found to respond differently to parental need and opportunity structures, being more likely to meet their parents’ need by cutting down working hours and interrupting their careers.

On the receiving end, the gender of the parent is a likely factor in whether and how much support is provided, as women tend to outlive men, hence they are more likely to experience widowhood in old age and need care. Besides differences in health and longevity, mothers are also more likely to engage in behaviours that build social capital and strengthen their commitment to elder-care norms (Silverstein, Gans and Yang Reference Silverstein, Gans and Yang2006). Older mothers typically receive more instrumental, financial and emotional support from their children than older fathers, with explanations lying in greater material investments of time and emotion in child rearing (Silverstein and Bengtson Reference Silverstein and Bengtson1997). In light of these findings, I test the hypotheses that female respondents provide more upward transfers to their parents than their male counterparts, and that older mothers receive more support than older fathers independently of average longevity and differentials in parental household types (Hypothesis 3).

Data sources to study intergenerational support in the European context

To the best of my knowledge, no studies have yet investigated the relationship between childlessness and upward intergenerational support using data other than SHARE. The present analysis suggests that the GGS may constitute a valuable alternative source to tackle the research question at hand and cross-validate demographic information within the European context. Differently from SHARE, the GGS samples individuals aged 18–79 and collects information from the middle generation (i.e. the adult children), hence allowing to: (a) treat survey respondents as children, and (b) shift the traditional research focus from what childless elderly people transfer downwards to what childless respondents transfer upwards to their elderly parents. Emery and Mudrazija (Reference Emery and Mudrazija2015) recently expressed the concern that the study of private intergenerational transfers in Europe may have become overly dependent on a single data source (SHARE) and wondered whether the findings of many studies would similarly hold with alternative data sources and methodologies.Footnote 2 I here welcome Emery and Mudrazija's claim that substantive research should avoid being overly dependent on a single data source.

Data and methodology

Sample and measures

The GGS is a set of comparative surveys of nationally representative samples of the 18–79-year-old resident population in each of the participating countries. In the GGS individual respondents are interviewed face-to-face and provide information on themselves as well as on their partners, children, parents, other household members and social networks. The sample size differs by country, but in most cases it is about 10,000 respondents. The overall response rates vary between 49 per cent in Russia and 78 per cent in Bulgaria. A detailed description of the survey's design, scope and aims can be found in Vikat et al. (Reference Vikat, Spéder, Beets, Billari, Désesquelles, Fokkema, Hoem, MacDonald, Neyer, Pailhé, Pinnelli and Solaz2007).

As of now, complete GGS data are available for 17 European countries in Wave 1 and nine European countries in Wave 2. This analysis uses Wave 1 data from 11 countries, namely Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Georgia, Poland, Romania, Russia (‘Eastern Europe’), Belgium, France, Germany (‘Western Europe’), the Netherlands and Sweden (‘Northern Europe’). These were chosen for their heterogeneity in terms of welfare systems and, foremost, for their close-to-complete and harmonised information on intergenerational transfers. The GGS also includes Australia and Japan, though the present study focuses on European countries with complete transfer data only. Hungary, Estonia and Lithuania were excluded from the analysis as they do not collect information on transfers. Austria and Italy were excluded as the age range of sampled respondents is different from 18–79 (18–46 in Austria and 18–64 in Italy). Furthermore, data on transfers in Italy refer to exchanges occurring over the previous month instead of the previous 12 months. Data for the countries in the analysis were collected between 2004 and 2010 and weighted to adjust for unequal probabilities of sample selection and non-response differences within countries.Footnote 3

As the analysis builds upon comparing childless and non-childless individuals, I restrict the overall sample to respondents close to the end of their reproductive span, i.e. individuals aged 40–79. I define as childless respondents 40+ who report having neither biological nor adopted/foster/step-children.Footnote 4 Table 1 reports descriptive statistics by country, separately for childless (CL) and non-childless (C) respondents. By restricting to ages 40 and above, the sample reduces from 121,206 to 75,452 respondents, 33,425 (44.3%) of whom are males and 42,027 (55.7%) are females.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for Generations and Gender Survey (GGS) respondents aged 40–79, by country and childless status

Notes: N = 75,452. C: with children. CL: childless.

Source: Generations and Gender Survey Wave 1, own calculations, weighted percentages/proportions and unweighted number of cases.

Data in Table 1 show that childlessness ranges from a minimum of 4.9 per cent of the sample in Russia to a maximum of 21.2 per cent in Germany. The mean age of respondents is stable across countries, with the non-childless averaging 56.8 years, as compared to 56.5 for the childless. Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of the childless and the non-childless show some degree of variation, both within and across countries, with particular reference to household composition. As expected, in all countries the proportion of adults with children living with a partner is about twice the proportion of childless, and the childless are significantly less likely to report being married. Household size is on average smaller for the childless by at least one unit. As far as schooling is concerned, highest educational level of the respondents and their parents is coded according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). I categorise individuals into three groups. Those with ISCED codes 0–2 (lower secondary education or less) are classified as ‘low education’, those with ISCED codes 3 and 4 (higher secondary education) as ‘medium education’ and those with ISCED codes 5 and 6 (tertiary education) as ‘high education’. Based on this categorisation, the percentage of childless and non-childless individuals with medium education within each country is similar, whereas the childless tend to be over-represented in the high-education category, particularly in Bulgaria, Georgia and the Netherlands. No clear pattern emerges when it comes to occupational status. While in the Netherlands the share of childless respondents who are employed or self-employed (61.0%) far exceeds that of individuals with children (47.6%), the reverse is observed in Russia (43.1% versus 33.0%) and Belgium (50.5% versus 38.6%). In terms of health differences, in six countries childless respondents are more likely to report being in poor health than adults with children. Although the literature is inconclusive on whether childlessness is associated with worse health in adulthood, these findings align with Graham (Reference Graham2015). Lastly, childless respondents and parents differ little in terms of attitudes towards old-age support, although the childless report overall a significantly higher mean value score, hinting at a stronger inclination towards helping their parents in case of need.Footnote 5

The GGS delves into how family relationships function through their tangible aspects, such as monetary transfers between family members, emotional and practical support, and the satisfaction that individual family members derive from their relationships with other members. As far as intergenerational transfers are concerned, the GGS includes information on both monetary and non-monetary transfers from children to parents (upward transfers) and from parents to children (downward transfers). The focus of this paper is exclusively on the former and builds upon the following combination of transfer variables, in a spirit similar to Mudrazija (Reference Mudrazija2014):

1. Assets and goods: ‘During the last 12 months, have you or your partner/spouse given for one time, occasionally or regularly money, assets or goods of substantive value to [R]?’ (henceforth, financial transfers).

2. Help on daily activities: ‘Over the last 12 months, have you given [R] regular help with personal care such as eating, getting up, dressing, bathing or using toilets?’ (henceforth, practical transfers).

3. Emotional support: ‘Over the last 12 months, has [R] talked to you about his/her personal experiences and feelings?’ (henceforth, emotional transfers).

Additional variables in the survey permit identification of the recipient of these transfers [R], among whom I keep biological parents, parents-in-law (if the respondent has a spouse/partner) and step-parents. Sensitivity analyses will assess the robustness of the findings to the exclusion of the latter two categories.

As the main outcome, I construct a dichotomous variable measuring the likelihood that respondents provide any type of support listed above. I acknowledge that the combination of different types of transfer into one variable may pose challenges to the validity of the study. For instance, country differences may emerge because the distribution of supports differs among nations. Similarly, adults with and without children may offer different types of support, thereby leading to misleading conclusions and policy recommendations. However, due to little variability in some transfer components and small cell sizes, it makes little sense to conduct statistical inference in a multivariate framework keeping the three support types as separate outcomes. In the following sections I will address these concerns by presenting bivariate associations and sensitivity analyses reconstructing the dependent variable excluding one type of support at a time.

Methodology

I begin the analysis by estimating age profiles of upward transfer flows between respondents aged 40+ and their elderly parents. Age patterns of transfers are estimated by means of a local polynomial regression-fitting procedure – kernel-weighted local polynomial smoothing – applied to individual-level data for each country. The age profiles provide a representation of the following variables as a function of age of the respondent:

1. Probability of providing support to any parent (‘unconditional transfers’).

2. Probability of providing support to any parent, conditional on at least one parent being alive (‘conditional transfers’).

The comparison between unconditional and conditional transfers is insightful as it reflects the contribution of parental survival to the observed transfer patterns at different stages of the respondent's lifecourse (Kohler et al. Reference Kohler, Kohler, Anglewicz and Behrman2012). For example, the fact that a respondent does not provide support to his/her mother can be due to the fact the she is deceased, or that the respondent does not give support to the mother despite her being alive.

Second, I examine childless/non-childless differences in upward support provision by means of multivariate logistic regression on the sample restricted to respondents whose parents are alive. I run models separately for transfers to any parent, to the mother and to the father, to assess whether predictions of higher upward support to mothers hold. I run five sets of models, adding controls for relevant characteristics of the respondent – and his/her parents – that may confound the association of interest. Model 1 estimates a simple bivariate relationship between childlessness and the dependent variable. Model 2 adds demographic controls such as age, gender, and an interaction term between gender and childlessness. The latter interaction, rarely considered in the literature, allows for the possibility that the experience of remaining childless (in terms of reactions and responses) might differ between women and men. Model 3 adds socio-economic controls for education and employment status to account for the fact that respondents with higher socio-economic status might be better positioned to provide upward support. Model 4 accounts for household composition variables such as household size, respondent's partnership status, number of siblings alive and parents’ living arrangements.Footnote 6 Lastly, Model 5 includes the remaining controls such as respondent's health status – as respondents in poor health might be less capable of providing upward support – and attitudes towards old-age support (henceforth ‘full specification’). All models control for country fixed-effects and include survey-year dummies to account for potential period effects.

Third, I complement logistic regression with a PS approach to address the possibility that non-random selection into childlessness may result in biased estimates. Childless and non-childless individuals may in fact be compositionally different along observed and unobserved dimensions. If most childlessness were unintentional because of genetic factors or exogenous health conditions that prevented successful pregnancy, endogenous selection would be minor and likely to have little effect on the estimates. The GGS, however, does not include complete information to identify individuals who were unable to become biological parents.Footnote 7

Although a natural or randomised experiment constitutes the ideal scenario to deal with selection, it is virtually impossible to run an experiment to generate an estimate of the effect of the ‘treatment’ of being childless that is unbiased by self-selection. In the absence of experimental data, a second-best approach would be to include person or family fixed-effects, or to identify an instrumental variable for childlessness, i.e. a variable that affects the probability of providing transfers to parents only through its effect on the respondent being childless. While the former strategy cannot be pursued in this context because childlessness is time invariant for each person and the GGS lacks sibling data, the implementation of the latter builds on the challenge of finding a variable that captures factors that affect childbearing decisions over a long period – roughly ages 18–45 years – but are not controlled by respondents, and are unlikely to affect transfer behaviour directly. Past research in the field has mostly relied on country-specific policy variables, such as Supreme Court rulings on contraception and abortion, as instruments for fertility outcomes (Ananat et al. Reference Ananat, Gruber, Levine and Staiger2009). Yet the multi-purpose scope of the GGS and the cross-national nature of this work prevent following this same route.

I hence resort to non-parametric PS models (Rosenbaum and Rubin Reference Rosenbaum and Rubin1985), with the PS being the probability of being childless, conditional on a set of observed characteristics. I use logistic regression to predict each respondent's PS. Once all respondents’ PS are calculated, a childless person is matched to one or more parents who have similar PS using one of several established procedures for determining matches.Footnote 8 The mean of the difference in outcomes between each treated case and its match (or matches) provides the estimate of the relationship between childlessness and the outcome.

One advantage of PS techniques is that, unlike regression models, they do not impose strong restrictions on the functional form of the relationship. They hence provide a useful tool to explore the results’ sensitivity to the linearity assumption of the regression approach, as documented in several other studies dealing with demographic outcomes (Chevalier and Viitanen Reference Chevalier and Viitanen2003; Gertler, Levine and Ames Reference Gertler, Levine and Ames2004; Levine and Painter Reference Levine and Painter2003). In fact, a potential pitfall of the regression approach entails that if the difference between the average values of the covariates in the childless and non-childless groups is large, the results are sensitive to the linearity assumption. However, PS methods do not help to deal with selection driven by unobserved characteristics likely to influence both childlessness and transfer provision to parents. If the treatment and control groups differ in unobserved ways, between-group differences may reflect those differences rather than the treatment (i.e. being childless) itself. Therefore, although PS estimates provide a useful benchmark, no claim of causality will be made throughout this analysis.

Due to the inherent complexity of dealing with the issue of selection into childlessness, very few studies have addressed it. In this endeavour, I follow Plotnick (Reference Plotnick2009, Reference Plotnick2011), who complements regression models with PS estimates to study how childlessness relates to the economic wellbeing and health status of the elderly in the USA.

Descriptive statistics on upward support

Figure 1 shows the probability of providing upward support to any parent in the 11 European countries included in the study. The figure reports four panels, one for the combined outcome described in the data section, and the remaining three for the three transfer components. The data show a high level of variability across countries, arguably due to a combination of cultural idiosyncrasies and different social policies (Albertini, Kohli and Vogel Reference Albertini, Kohli and Vogel2007; Deindl and Brandt Reference Deindl and Brandt2011). Upward support is remarkably low in the Netherlands and Sweden, i.e. the Northern European countries in the sample. These countries best embody the ‘social democratic’ type of welfare state described by Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990), characterised by publicly funded and administered programmes with comprehensive and universal coverage and relatively egalitarian benefit structures. Although purely speculative at this stage, these findings align with previous research showing that across European countries upward support – both practical and financial – is less likely when the state provides adequate public support, thus indicating a ‘crowding out’ of private transfers by state transfers (Deindl and Brandt Reference Deindl and Brandt2011). In short, the more generous the welfare state, the lower the need to provide upward support within the family (typically the opposite holds for downward transfers to children). No big difference is observed in the likelihood of providing upward support between Eastern and Western European countries, although Russia stands out of the picture as the country with the highest likelihood of upward transfer provision (about 0.3), followed by the Czech Republic. In line with the institutional argument outlined above, both countries are characterised by ‘former socialist’ types of welfare states, where old-age support is largely based on family ties (Margolis and Myrskylä Reference Margolis and Myrskylä2011). A look at the individual transfer components suggests that the likelihood of providing upward financial transfers is the lowest, followed in turn by practical and emotional help. Most importantly, the distribution of different types of support does not markedly differ among nations, i.e. in countries where one type of support is high (low), other types of support are high (low) too (e.g. Russia). This increases confidence in the validity of the combined outcome variable.

Figure 1. Probability of providing transfers to any parent, by type of transfer and country. Source: GGS wave 1, own calculations, weighted.

Table 2 reports descriptive statistics for the likelihood of providing upward support by country, childless status and transfer recipient (any parent, mother and father). The table conveys two main ideas. First, the likelihood of providing transfers to mothers is at least twice that of providing transfers to fathers, likely due to the fact that women outlive men and thus men are potential receivers of support from their wives. Second, t-tests for the difference in means between sub-groups suggest that in Bulgaria, Georgia, Poland, Romania and France childless respondents are significantly more likely to transfer than non-childless, while they provide significantly less support in the Czech Republic. In the remaining countries differences are not statistically significant, yet the consistently negative sign on the difference provides suggestive evidence that, at least in a bivariate framework, the childless are on average more supportive to their elderly parents. To address the concern that childless/non-childless differences in upward support might differ according to the type of support considered, in Table S1 in the online supplementary material I report t-tests for the difference in means by type of transfer (financial, practical and emotional). These data show that never for one country is the childless/non-childless difference negative for one type of support and positive for other types of support (it is typically negative and statistically significant for one or two types of support, and null for the third). Georgia is a case of full concordance, in that for all three types of support the difference is negative and statistically significant, suggesting that the childless provide more upward support to their parents, regardless of the type of support.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics on the probability of providing transfers to parents by country, childless status and transfer recipient

Notes: Robust standard errors are given in parentheses. C: with children. CL: childless.

Source: Generations and Gender Survey Wave 1, own calculations, weighted.

Significance levels: † p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 (t-tests).

Results

Age profiles of upward support

As the probability of providing support varies over the lifecourse, Figure 2 shows the age pattern of transfers made by respondents aged 40+ to any parent by country and childless status, unconditional (top panel) and conditional on at least one parent being alive (bottom panel).Footnote 9 Age profiles from the top panel show that the likelihood of providing upward support at exact age 40 is around 0.2 across Eastern and Western European countries, while it reaches a minimum of 0.05 in Northern European countries. Interesting heterogeneity unravels when looking at differences between childless and non-childless adults across countries. In line with the descriptive statistics, in the Czech Republic individuals with children transfer more to their elderly parents as compared to the childless, with a higher likelihood observed throughout the whole adult lifecourse. Conversely, in Georgia and Poland the childless transfer more up until around age 65–70. No noticeable pattern emerges in the remaining countries, as the likelihoods of childless and non-childless respondents overlap at multiple stages. Overall, estimates from the top panel show that upward transfers decline rapidly with the age of the respondent, suggesting that a declining probability of having a living parent determines a strong age pattern in the unconditional transfers. The bottom panel allows assessment of the contribution of parental survival to the observed transfer patterns. Conditional on parental survival, the likelihood of providing upward transfers does not follow a steep age pattern and respondents are more likely to transfer to their parents across all ages. More discrepancies emerge between childless and non-childless respondents, especially in Eastern European countries, suggesting that mortality trends in these countries play an even stronger role in shaping observed transfer patterns (Table S2 in the online supplementary material hints at the heterogeneity in mortality patterns across the 11 European countries).

Figure 2. Probability of providing transfers to any parent, unconditional (top) and conditional on at least one parent alive (bottom), by country and childless status.

Logistic regression

Table 3 presents multivariate results from a logistic regression of the probability of providing transfers to any parent on the childlessness dummy, estimated on the sample restricted to respondents with at least one living parent. The key findings are as follows. First and foremost, childless respondents are significantly more likely to provide support to their elderly parents as compared to individuals with children. Estimates are robust across specifications and suggest that childless males are about 30–40 per cent more likely to transfer to their parents compared to non-childless males, with no significant differences by gender of the survey respondent (i.e. given that the gender–childless interaction is not statistically significant, the finding also holds for female respondents). Note that the reported coefficient on childlessness represents an average association for the 11 countries considered in the analysis, yet some country-specific exceptions where the opposite trend is observed persist (e.g. Czech Republic). In line with the fading age patterns once parental survival is taken into account (Figure 2), age does not turn out to be a crucial driver of transfer patterns.Footnote 10

Table 3. Logistic regression (odds ratios): likelihood of providing transfers to any parent, conditional on at least one parent being alive

Notes: Robust standard errors are given in parentheses. Models control for country and survey-year dummies. Ref.: reference category.

Source: Generations and Gender Survey Wave 1, own calculations, weighted.

Significance levels: † p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Female respondents provide more upward support than their male counterparts across all specifications (also shown in Figure S1 in the online supplementary material). Gendered roles stressing daughters’ kin-keeping and presumed expertise in carrying out what their societies regard as typically feminine tasks related to care-giving might be among the underlying mechanisms (Gerstel and Gallagher Reference Gerstel and Gallagher2001; Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985). Measures of socio-economic status suggest that there is a clear and robust educational gradient in transfer provision (also shown in Figure S1 in the online supplementary material).Footnote 11 Compared to respondents with low education, the odds of providing upward transfers for the medium- and high-educated are 1.5 and 2 times larger, respectively. When it comes to employment status, the data show that retired individuals are about 10–15 per cent more likely to support their parents compared to their employed counterparts, while housekeepers and unemployed adults do no statistically differ from employed ones. Controls for household composition are aligned with findings from the relevant literature. Divorced individuals are approximately 20 per cent more likely to provide upward support than married ones. By the same token, adults living with a partner are 15 per cent less likely to transfer upward. Many explanations (beyond the scope of this paper) might lie behind these findings, such as more competing time demands on the part of the partnered, more expenses, more emotional independence, less need for alternative social ties, etc. (Sarkisian and Gerstel Reference Sarkisian and Gerstel2008). Consistent with the idea that individuals with siblings share responsibilities towards their parents (Bonsang Reference Bonsang2007), we observe declining odds of upward support with each additional living sibling. Lastly, respondents with more positive attitudes towards providing care and financial transfers to parents effectively show a higher likelihood of transfer provision. Overall, the key message from this set of models is the following: on average, the childless are more likely to provide higher upward support even after ruling out differences due to demographic, socio-economic and household composition variables, with the coefficient on the childlessness dummy proving remarkably stable in magnitude and significance.

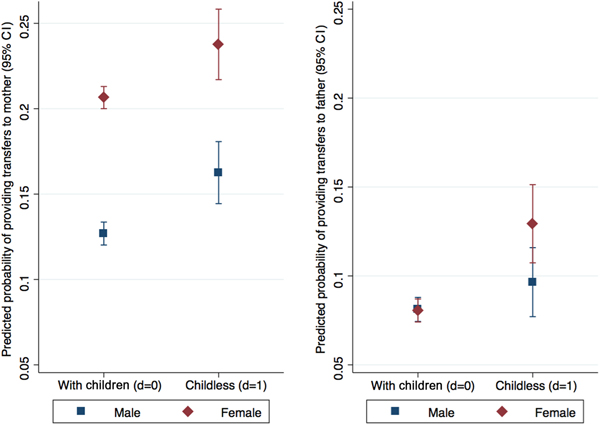

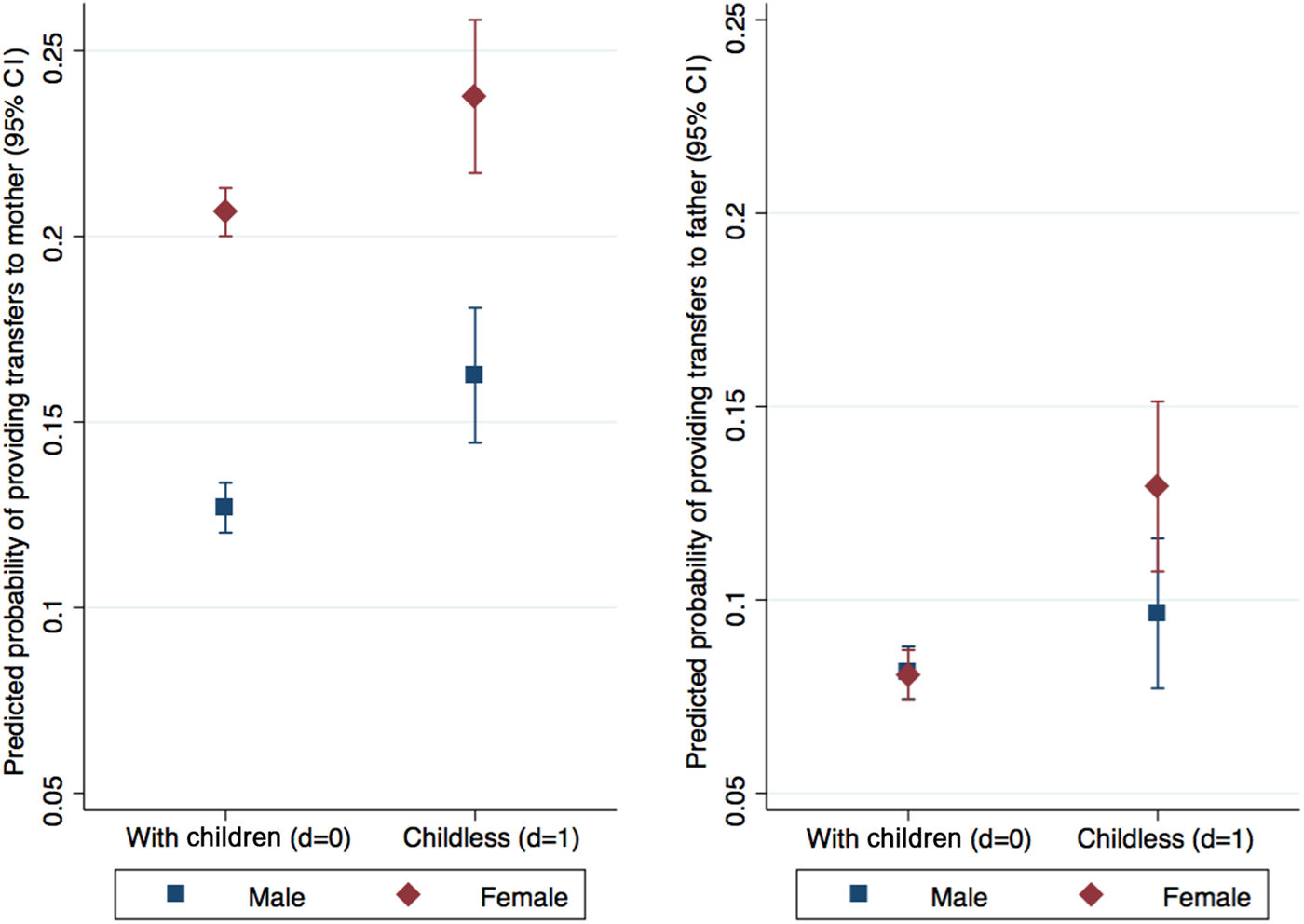

Figure 3 plots predicted probabilities of upward support from the full specification estimated separately for transfers to the mother (left panel) and transfers to the father (right panel). The corresponding regression output is reported in Table S3 in the online supplementary material. Note that these two models are estimated on the samples restricted to respondents whose mothers (fathers) are alive, and the control for parental household type shown in Table 3 is replaced by a variable for whether the mother (father) lives alone. For transfers to mothers the data show that the predicted probability of providing upward support is higher for female respondents, regardless of childless status; childless males support significantly more than males with children (0.163 versus 0.127); and childless females support significantly more than females with children (0.238 versus 0.207). Conversely, for transfers to fathers there is no evidence of statistically significant differences in upward support provision between childless males and males with children, while childless females are significantly more likely to transfer to their fathers than females with children. Findings also align with theoretical predictions and confirm raw evidence from descriptive statistics that the likelihood of supporting mothers is higher (almost double) than the likelihood of supporting fathers. These multivariate analyses limited to living parents and controlling for living arrangements of the parents suggest that gender differences in support receipt might be due to higher socio-emotional connectedness with mothers, rather than differential longevity whereby women outlive men and fathers potentially receive support from their wives.

Figure 3. Predicted probability of providing transfers to mothers (left) and fathers (right), by sex of the respondent. Full specification (model 5).

Propensity score estimation

The goal of this sub-section is to match childless individuals with non-childless individuals with similar observed characteristics, and get an estimate of the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT) by means of PS estimation techniques. Concerning the choice of covariates to include in the PS model, Sianesi (Reference Sianesi2004) and Smith and Todd (Reference Smith and Todd2005) recommend choosing: (a) variables that influence simultaneously the treatment status (i.e. childlessness) and the outcome variable (i.e. likelihood of transfer provision); and (b) variables that are unaffected by the treatment itself. As the set of variables at my disposal is limited, I estimate the score including only age, gender, education and number of siblings alive, grouping by country. The logit specification used to estimate the PS for each individual passes the balancing test (Dehejia and Wahba Reference Dehejia and Wahba2002), and the distributions of PS for childless and non-childless adults closely overlap within the region of common support. This indicates that there are ample numbers of parents well matched with each childless person.Footnote 12

Table 4 reports estimates of the ATT using three types of matching algorithms, namely nearest-neighbour, Epanechnikov kernel and radius matching. Standard errors are bootstrapped. Although the odds ratios from Table 3 and Figure 3 and the matching estimators provided in Table 4 are not directly comparable – as the latter show the difference between childless and non-childless mean probability of the outcome – findings from Table 4 are mostly consistent with the regression results. Specifically, there is evidence that childless adults transfer more to any of their parents compared to non-childless, and the difference between the mean probability of the outcome ranges from a minimum of 0.027 with nearest-neighbour matching and a maximum of 0.039 with radius matching. Results are consistent across matching methods, and the estimated ATTs are positive and statistically significant for transfers to any parent and transfers to mothers, while there is no evidence of differential support to fathers between childless and non-childless adults. This latter finding slightly departs from evidence shown in Figure 3 (right panel), yet it provides a more conservative estimate, hence I take it as more reliable.

Table 4. Estimated coefficient on the childless dummy variable using different propensity score estimators

Notes: ATT: Average Treatment Effect on the Treated. Bootstrapped standard errors are given in parentheses. Caliper set at 0.0005. These models include no gender–childless interaction; the reported coefficient hence compares childless versus adults with children (instead of childless males versus males with children).

Source: Generations and Gender Survey Wave 1, own calculations, weighted.

Significance level: ** p < 0.01.

Sensitivity analyses

Wealth and income

As outlined in the theoretical background, an important concern has to do with the possibility that the higher likelihood of upward support on the part of the childless might reflect their higher wealth or earnings potential. Due to missing data and lack of comparative measures of income and wealth, these controls were not included in the main specifications reported in Table 3. Findings from previous literature have in fact shown that the childless do not markedly differ from parents in mean income, and parenthood tends not to be associated with lower wages (Lundberg and Rose Reference Lundberg and Rose2000; Plotnick Reference Plotnick2009).Footnote 13 According to data from the Netherlands, fathers between 40 and 59 have even higher incomes than childless men (Dykstra and Keizer Reference Dykstra and Keizer2009). Evidence on wealth differences is instead more blurred. In the US context, while Plotnick (Reference Plotnick2009) documents that mean differences in wealth between childless and non-childless are not statistically significant, Lundberg and Rose (Reference Lundberg and Rose2000) find that childless unmarried men have greater wealth arising from not paying the costs of raising children. If this is the case, the childless might be more likely to devote these additional resources to caring for parents, thereby explaining the significant differences documented in Table 3.

I here assess the robustness of the findings to the inclusion of wealth and income measures for countries in which the latter are available. Table S4 in the online supplementary material reports mean differences in (a) the proportion of respondents who own the dwelling in which they live (the only available proxy for wealth); (b) household-level average net income over the past 12 months; and (c) individual-level earnings from a main job or business over the past 12 months (in Purchasing Power Parity).Footnote 14 GGS data largely support what is commonly found in the US context. As far as ownership is concerned, in eight out of the 11 countries the proportion of parents who own the dwelling is significantly higher than that of childless adults. Similarly, in six out of seven countries average household income is far higher for parents, a result which does not surprise given that parents tend to have larger mean household sizes, hence more potential contributors. Individual-level data on earnings confirm Lundberg and Rose's (Reference Lundberg and Rose2000) finding that there is no significant childless/non-childless difference in earnings. The only statistical differences are observed in Poland, Sweden, and Germany. While in the former two countries earnings are significantly higher for parents, the opposite holds in Germany. Taken together, these descriptive statistics suggest that, if anything, wealth and income differences tend to favour adults with children.

Table 5 (panel a) reports regression coefficients from a series of models (full specifications) predicting transfers to any parent, with controls for respondents’ education replaced, in sequence, by ownership status, household income (log-transformed) and individual earnings (log-transformed). Results from these models are in line with those presented in Table 3, and they show that childless males are approximately 20–35 per cent more likely to provide support to their parents as compared to their non-childless counterparts, with no significant differences by gender of the respondent. While controlling for either ownership or household income alters the magnitude of the coefficients to a minimal extent, the odds ratio drops more significantly once individual earnings are accounted for, suggesting that differences in earnings by childless status explain a portion of the association of interest, albeit still minimal.

Table 5. Sensitivity analyses (conditional on at least one parent alive)

Notes: Robust standard errors are given in parentheses. Full specification reported (Model 5 from Table 3). Household income and earnings from main job have been log-transformed. Ref.: reference category.

Source: Generations and Gender Survey Wave 1, own calculations, weighted.

Significance levels: † p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Type of support

I then test the sensitivity of the results reported in Table 3 to the type of support provided, to ensure that combining three transfer components (financial, practical and emotional) into a single outcome does not lead to misleading conclusions. Instead of running models for each transfer component, I preserve variability by reconstructing the combined outcome excluding one type of support at a time. Estimates from Table 5 (panel b) show that results are consistent across specifications, stronger in magnitude when emotional transfers are excluded (1.43) and smaller when practical transfers are excluded (1.17), thus suggesting that the documented association is independent of the type of support considered, yet practical transfers are the strongest drivers.

Age

Given that nowadays many adults still have children in their forties, in panel c of Table 5 I test the sensitivity of the results to alternative sample selections based on the age of the respondent. Findings are again fully consistent with those reported in Table 3 (Model 5), although the magnitude of the main coefficient of interest decreases with each subsequent sample restriction (1.32 for 40+ to 1.29 for 45+ to 1.27 for 50+).

Extended family

Lastly, acknowledging that past research demonstrates that upward support to biological parents is typically higher than the one provided to parents-in-law and/or step-parents (Coleman and Ganong Reference Coleman and Ganong2008; Schoeni et al. Reference Schoeni, Bianchi, Hotz, Seltzer and Wiemers2015; Steinbach and Hank Reference Steinbach and Hank2016), I conclude the analysis by addressing the concern that the composition of these parent types might vary between childless and non-childless respondents, potentially leading to misleading results. As the prevalence of transfers to parents-in-law and step-parents in the sample is very low, I follow the above approach and reconstruct the dependent variable excluding transfers to members of the extended family. Estimated coefficients are essentially unchanged (panel d).

Conclusions and discussion

This study has shed light on the reality of intergenerational support from respondents aged 40 and above to their elderly parents, a topic of study that has received little attention in socio-demographic research (Dykstra et al. Reference Dykstra, Bühler, Fokkema, Petric, Platinovšek, Kogovšek and Hlebec2016). Using GGS data from 11 European countries I have shown – and confirmed evidence from SHARE – that the likelihood of upward transfer provision is higher in Eastern and Western European countries, while it is lower in Northern European ones. Although no definitive claim can be made, this finding provides suggestive evidence that in countries with more generous welfare states middle-aged adults take up, on average, less responsibility towards their elderly parents (Hypothesis 1). By means of logistic regression and PS matching, I have then examined whether childless and non-childless adults differ in their propensity to support their elderly parents. My findings, robust across methodologies, are consistent with the hypothesis that the childless are more likely to provide support to their elderly parents than individuals with children (Hypothesis 2a). Separate analyses by gender of the transfer recipient have shown that transfers to fathers are far lower than transfers to mothers, independently of average longevity (Hypothesis 3), and statistical differences in transfer provision by childless status arise when predicting the latter only.

Interestingly, the significant estimates on the childlessness dummy are only marginally explained by sub-group differences in respondents’ household composition, education, occupation, wealth, earnings, parental living arrangements and attitudes towards old-age support, thus suggesting that other dimensions – either missing from the current framework or measured in alternative ways – lie at the root of the differences. Among the most likely candidates, I suspect that having information on time allocation (such as time-use diaries) and better data on income and savings would permit light to be shed on additional relevant mechanisms. As they stand now, my results are nonetheless consistent with the idea that childless adults compensate for the lack of children by strengthening social ties with their elderly parents.

The findings of this research support the argument that researchers and policy makers should take into more consideration not only what childless people receive or need in old age, but also what they give. The available literature stresses that, from a social policy perspective, increasing childlessness rates may be a challenge – in addition to that of population ageing – to the current configuration of the systems of long-term care provision (Albertini and Mencarini Reference Albertini and Mencarini2014). My findings are not at odds with this claim, yet they point towards a different set of societal implications. Specifically, they suggest that the rise in childlessness may be less worrisome for public care policies than is commonly held. In a multigenerational perspective, the strain that the growth of the elderly childless imposes on the sustainability of the welfare state might be partly compensated by the higher upward support they themselves provide as middle-aged adults. In other words, the contributions that childless adults provide to society are important and ought to be more visibly acknowledged. On top of this, this work may contribute to shaping further the policy and media discourse that still depicts childless adults as selfish and self-absorbed individuals.

This study has limitations that lay the ground for subsequent research. First, due to data restrictions, the analysis makes no clear-cut distinction between voluntary and involuntary childlessness. As the involuntary childless would likely behave as parents in terms of downwards transfers to children, one could raise the concern that the involuntary childless would also resemble the non-childless in their propensity to provide transfers to parents, hence biasing estimates upwards. If data allowed, it would be ideal to treat the voluntary childless as a separate group. Second, the study builds upon a dependent variable that measures the likelihood of transfer provision only, with no reference to the magnitude, intensity or frequency of exchanges. The GGS provides the cash value of the financial transfers, yet data quality on this variable is too poor to prove useful for this research. A third source of concern, typical of every survey-based research on private transfers, is the possibility of systematic bias in the self-reported transfer measures. The literature (e.g. Mason et al. Reference Mason, Lee, Tung, Lai and Miller2006) suggests that survey respondents systematically under-report transfers received and over-report transfers made, which suggests that the extent of upward support could be biased upwards. Fourth, and most importantly, is the issue of selection into childlessness. While PS matching is a useful tool to reduce the bias driven by selection on observables, unobserved heterogeneity still prevents one from making causal claims. The broad agreement across logistic regression and PS models suggests a degree of reliability to my findings. Yet they are certainly not undisputable, since the sensitivity of the estimates to possible selection on unobservable characteristics cannot be assessed with any of the methodologies at hand.Footnote 15

This analysis has also demonstrated that studying intergenerational support in Europe through the GGS presents advantages as well as challenges. On one hand, the GGS represents a valuable alternative to SHARE due to the high number of countries covered, the availability of contextual information and the inclusion of transfer data (in a way that could be compared with transfer data in SHARE). On the other hand, it still lacks complete and harmonised information in important domains – such as fertility intentions, income, frequency of transfers, time-use modules, etc. – that would permit more elaborate theories of change to be tested. Future ageing research should capitalise on the GGS and SHARE in a synergistic way so that weaknesses on either front could guide scholars and policy makers towards even higher data quality standards.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X17001519

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges helpful comments from two anonymous referees, Francesco C. Billari, Hans-Peter Kohler, Melissa J. Wilde, Herb L. Smith, Irma T. Elo and Tom Emery. I am also grateful for useful comments from seminar participants at the 2016 European Population Conference (EPC) and the 2017 Population Association of America. This work was supported by the Fulbright Commission and the School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania. No ethical approval was required.