INTRODUCTION

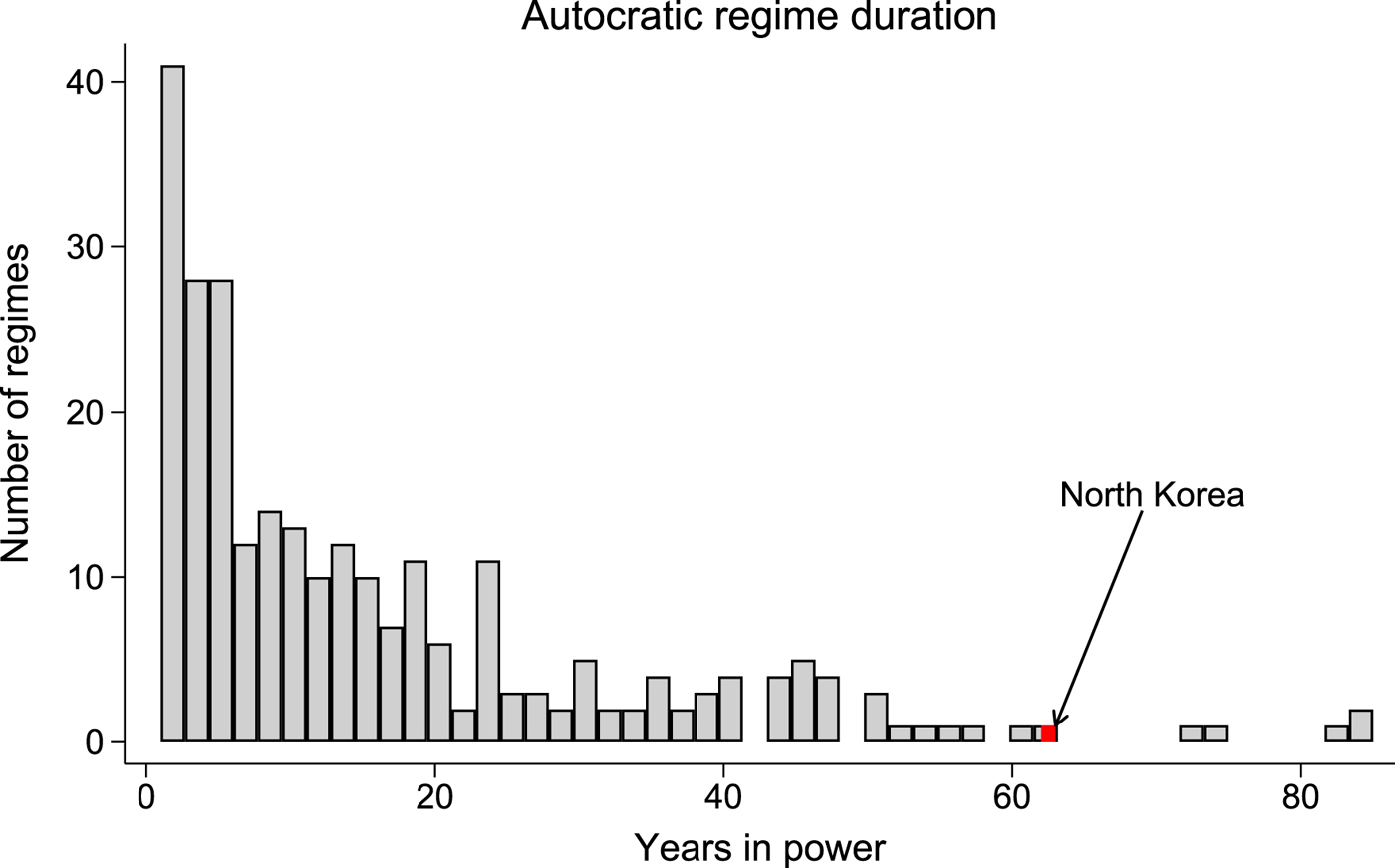

The North Korean dictatorship is the longest enduring autocratic regime in the post-World War II era. Figure 1 shows the distribution of regime longevity for non-democratic regimes in the post-war period.Footnote 1 While four dictatorships—in Mexico, Mongolia, the Soviet Union, and South Africa—all lasted longer than 70 years, the North Korean regime is the oldest surviving dictatorship outside of monarchies, closely rivaled by the Chinese Communist Party regime. A common feature of durable authoritarian regimes is a dominant political party that supports the regime. The Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Party of the Revolution, or PRI) in Mexico and the Communist parties in the Soviet Union and China are examples of dominant political parties that aided long-lasting autocratic regimes. Indeed, a well-established empirical finding suggests that dominant party regimes, in contrast to military juntas and personalist dictatorships, endure the longest (Geddes Reference Geddes1999, Reference Geddes2003).

Figure 1 The durability of the North Korean regime in comparative perspective

The North Korean regime differs from other long-lasting dictatorships because the leader successfully concentrated power, personalizing the regime. This characterization contrasts with early studies of North Korea that compared the case with other Communist parties (e.g. Scalapino and Lee Reference Scalapino and Lee1972; Suh Reference Suh1988) as well as with later work that emphasizes the role of the military in the Kim regime (Wintrobe Reference Wintrobe2013; Haggard, Herman, and Ryu Reference Haggard, Herman and Ryu2014). Further, many extant comparative data sets of autocracies simply note the role of civilian (i.e. non-military) leadership (e.g. Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Svolik Reference Svolik2012) or categorize it as a “one-party dictatorship” (Svolik Reference Svolik2012; Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius Reference Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius2013). We show that within his first decade as ruler, Kim Il-sung curtailed military autonomy and largely subdued the independent power of the Korean Workers’ Party. He even established a succession rule allowing his son and later grandson to succeed him as regime leaders—an unprecedented and unmatched example of enduring family rule found in no other dictatorship in the modern era outside of hereditary monarchies.

This paper examines the North Korean dictatorship in comparative perspective. We argue that high degree of initial factionalization of the regime, coupled with the presence of multiple foreign backers early in the regime, allowed Kim Il-sung to stamp out potential threats to his rule from the military first, and then subsequently curbed the autonomous power of the Korean Worker's Party. To support this argument, we trace the consolidation of personal power in the hands of the regime leader.

Characterizing the North Korean regime as highly personalist has implications for a number of important policy areas, because a large body of recent research on non-democratic politics shows that personalist dictatorships tend to have more aggressive foreign policies than other non-democratic regimes, are less cooperative in international relations, and are the least likely to give way to democracy when they collapse (Weeks Reference Weeks2008; Mattes and Rodríguez Reference Mattes and Rodríguez2014; Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014).

In addition to providing the first systematic, comparative evidence that traces the evolution of personalist power in North Korea, we make two contributions to the comparative study of autocracy. First, we compare the North Korean regime to other communist regimes in the region, China and Vietnam, to show how the evolution of personalist rule in these cases differed. Cross-national datasets code these three regimes similarly, in part, because they all have origins in military conquest and all three regimes have similar dominant party organizations that support regime rule. The North Korean regime, however, is the only one to devolve into a permanent personalist rule.

By comparing across cases, we gain perspective on key differences that help explain the distinct trajectories of personalist rule. When the Soviets handed North Korea independence, Kim Il-sung bargained with a new domestic military and a recently formed political party. While such groups often mitigate the personalization of power during the early years of regime consolidation, the North Korean military and regime party were newly created and highly factionalized; and Kim, with backing from Soviet occupation forces, had a hand in creating them, making them less likely to serve as mobilizing tools for mounting elite challenges to the leader. The presence of multiple foreign backers, in this case Soviet and later Chinese forces, created further coordination obstacles for domestic groups seeking to mobilize credible threats to oust Kim.

Second, we show that Kim Il-sung initially wrested power from the military and then subsequently established personal control over the party. That is, the sequence of personalization in the North Korean regime took the form of first subduing the military as an autonomous organization with the ability to constrain the leader's policy and personnel choices. Then, only after securing firm control of the military, did the regime leader dismantle the independent power of the supporting political party. We explain this sequence by underscoring the fact that while the regime was imposed by one foreign power (the Soviet Union), it was backed militarily by another (China). As a result, the initial regime leader in North Korea successfully consolidated power over the military with less fear of military backlash and degradation of combat effectiveness than did leaders in most other autocratic regimes.

This research contributes to both the growing literature on authoritarianism that examines the historical origins of different flavors of autocratic rule (e.g. Jackson and Rosberg Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982; Slater Reference Slater2010; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2013; Kendall-Taylor, Frantz, and Wright Reference Kendall-Taylor, Frantz and Wright2017) and the literature on the consolidation of personal autocratic power (e.g. Svolik Reference Svolik2012; Morgenbesser Reference Morgenbesser2017). We introduce and discuss measures for two theoreticallyimportant components of consolidated personal power in the North Korean regime: control over the supporting political party and control over the military and internal security apparatus. We then utilize these measures to compare across cases and to explain the sequence of personalization in North Korea.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Interpretations of the nature of the North Korean regime evolved throughout the Cold War and the post-Cold War periods. Initial characterizations from Western scholars viewed the North Korean regime as a puppet of the Soviet Union without the need for independent analysis (US Department of State 1951). As Kim Il-sung consolidated personal power, researchers began to emphasize North Korea as a unique form of communist state, distinct from the Soviet Union, China, or Eastern European states (Scalapino and Lee Reference Scalapino and Lee1972; Suh Reference Suh1988). After the Cold War, some emphasized the historical events prior to 1947 or employed social structural factors to categorize the North Korean regime. For example, guerilla state theory argues that Kim Il-sung's experience as anti-Japanese rebel leader underpins the features autocratic rule in this regime (Wada Reference Wada and Lee1992). And scholars such as Cumings (Reference Cumings2004) and Suzuki (Reference Suzuki and Yu1994) viewed North Korea as a familial state with the mixture of socialism and Confucian hierarchy.

Other approaches emphasize the political role of the armed forces in communist states. The political role of communist militaries varied widely as a result of distinct circumstances under which different regimes came to power (Albright Reference Albright1978, 302–308). For example, in revolutionary communist regimes such as China, Cuba, and Vietnam, where the party came to power after a “protracted guerilla struggle during which political and military institutions developed simultaneously and interdependently,” the armed forces were respected and gained considerable political power (Colton Reference Colton1978, 221). On the other hand, leaders of communist regimes that were imposed by a foreign power, such as the Soviet Union, did not have an opportunity to develop the armed forces as a “mirror of the state” and thus became suspicious of the military's loyalty and political socialization. Leaders of Eastern European communist regimes that were installed by the Soviet Union did not share nationalistic, religious, agrarian, and anti-Russian sentiments that were common among the military officers and the general population (Herspring and Volgyes Reference Herspring and Volgyes1977, 251). In these cases, coercion eliminated hostile elements within the armed forces and political socialization ensured military officers’ loyalty.

More recently some scholars have emphasized the rise of military power in the North Korean regime (Wintrobe Reference Wintrobe2013; Haggard, Herman, and Ryu Reference Haggard, Herman and Ryu2014). The rise of military importance reflects the regime's ideological adaptation in the late 1990s after the death of the first regime leader, in which his son, Kim Jong-il, promoted the concept of “military-first” politics (Songun chongch'i) (Armstrong Reference Armstrong and Dimitrov2013, 100).

Scholars of comparative authoritarian politics categorize the regime as a civilian-led, single party dictatorship (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Svolik Reference Svolik2012) or dominant, single-party regime (Geddes Reference Geddes1999; Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius Reference Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius2013). This research focuses on broad institutional features of the regime such as the presence of a support party as well as the civilian background of the leader. However, the latter, as well as subsequent efforts that build on this project, such as Weeks (Reference Weeks2014) and Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014) describe the regime as a hybrid dominant-party and personalist regime.Footnote 2 Finally, Levitsky and Way (Reference Levitsky and Way2013) categorize the North Korean regime as one of the 25 “revolutionary” regimes that seized power after rebellions that destroyed prior power structures in society. None of these projects, however, incorporate comparative micro-historical data tracing the political events that contribute to the rise of personalist power.

While some scholars characterize the North Korean government as a variant of communist rule, and others note the role of the military or a hybrid form, we introduce a detailed way not only of measuring the personalist pattern but of showing how it compares with the other Asian communist systems. In doing so, we show that the Kim regime is not only personalist but more consistently personalist over time than either China or Vietnam.

Our characterization of the North Korean dictatorship emphasizes the personalist nature of the regime but notes that it is different from most personalist dictatorships in the post-WWII era because of its origins.Footnote 3 In particular, when the regime was imposed by foreign powers it had the backing of a pre-existing but nascent support party (Korean Workers’ Party) and a newly built military comprised mostly of former rebels (Korean People's Army), from both China and the Soviet Union. These two pre-seizure features of autocracies typically make the personalization of power more difficult because they entail the initial regime leader bargaining with a more unified support coalition. In the North Korean case, however, elite factionalization prevented these organizations from mobilizing credible threats to the regime leader in an attempt to counter moves by the leader to personalize the regime.

PERSONALIST RULE

Dictators cannot rule alone. Seizing power by undemocratic means most often occurs with the help of a group supporting the dictator, often referred to as the “launching organization” or “seizure group” (Haber Reference Haber, Weingast and Wittman2006; Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018). The features of this group vary widely. Sometimes the seizure group is composed primarily of senior-ranking military officers; other times it is a disciplined political party that forms a rebel military. In still other regimes, the seizure group is simply the extended family of the initial regime leader. At the extreme, a seizure group may be little more than a loosely organized assortment of semi-autonomous factions, as was the case in North Korea. While the composition of the main group supporting the leader can change over time—for example as the leader increases his own power by excluding members of the seizure group from power or switches his support base from one group to another—the differences among seizure groups help explain why some leaders successfully consolidate power while others must continue to share it widely.

The internal cohesion of the seizure group influences the relative bargaining power of the dictator and members of his inner circle (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018). Cohesive seizure groups demand more from the dictator in return for their support. In contrast, if the initial leader faces a factionalized seizure group, he can bargain separately with different members of the group. Further, dictators have an informational advantage over a factionalized seizure group because the leader can use different factions to spy on each other. Better information helps dictators to unearth potential coup plotters. And factionalized seizure groups face higher collective action costs in attempts to overthrow the leader, which leads some, such as Haber (Reference Haber, Weingast and Wittman2006), to argue that the solution to preserving authoritarian power is to create multiple, overlapping regime support organizations.

Second, more unified seizure groups are better able to make credible promises of support if the dictator shares power. When discipline has long been enforced through an institution—such as a unified military or a political party with a long history as a rebel movement—members of the inner circle can commit their subordinates in the organization to abide by agreements made with the leader. This in turn, makes the promise of support by the seizure coalition more credible. Thus, because factionalized seizure groups are both less likely than unified groups to overcome collective action problems to mount a credible challenge to the leader and less capable of making credible promises to the leader if he shares, factionalization should lead to more personalization.

The origins of the North Korean regime, we argue, gave rise to a highly factionalized support coalition at the time of independence in 1949. The rise of these factions stemmed, in part, from the confluence of historical events at the close of the Second World War: liberation of the Korean peninsula from Japanese occupation; the participation of ethnic Koreans in the Chinese civil war, which left the Communist Party in territorial control of northern China by 1945; and Soviet occupation of the northern half of the peninsula, coupled with two distinct groups of ethnic Koreans living in Soviet territory in the early 1940s, one with links the Soviet Communist Party and other with standing in the Soviet military.

When Japanese occupation ended, the Soviets brought both Soviet-aligned groups to Pyongang, while the Korean Communists in southern Korean fled to the North for fear of repression in the newly created South Korean state. Meanwhile, the largest group of armed ethnic Koreans, closely aligned with the People's Liberation Army, was stationed in northern China. Importantly, these disparate groups did not have to work together to seize power from the prior regime, in this liberating Korea from Japanese occupation. Instead, the Soviet military was the organization that seized power; it subsequently empowered—to varying degrees—each of these initial factions in an effort to establish an independent North Korean client state. We posit that this factionalization of the initial support coalition, which never had to act collectively to seize power, gave rise to a highly personalist regime in North Korea.

In what follows we introduce how we measure personalization and then compare the North Korea dictatorship to two other communist regimes in the region. Next, we trace the historical evolution of personalization in North Korea from independence onwards by showing how Kim Il-sung first personalized the military and security apparatus and then subdued the autonomous power of the Korean Workers’ Party (KWP). Finally, we explain this sequence by tracing how Kim played factions against each other to consolidate his own power, and we argue that the presence of two foreign backers exacerbated coordination obstacles for elites who might have otherwise challenged the leader.

MEASURING PERSONALISM

There is now a wide body of research on authoritarian politics that utilizes measures of personalism, in particular the categorical regime typology pioneered by Geddes (Reference Geddes1999). We build on this approach but use newly collected data that covers all dictatorships in the world from 1946 to 2010; it captures observable indicators of personalist power (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018). This allows us to examine how personalist power changes over time within particular autocratic regimes. While prior research categorizes a dictatorship as either personalist or not, we use data that measures this concept over time. For example, instead of treating the Chinese Communist Party as a civilian or dominant party regime for its entire duration, measuring personalism over time allows us to show how personalism varies across different leaders of the same regime. For example, as we demonstrate below, we can trace the rise and decline of Mao's power as well as compare the level of personalism under his rule to that of subsequent leaders of the same regime.

The Personalism Index we construct for this paper aggregates information from 10 indicators of personalist power, grouped into three broad categories. The observable indicators of personalism are gathered from information about politics after the regime seizes power (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018). These features extend beyond observing hereditary leadership succession.Footnote 4 The first dimension relates to how the leaders who are not the initial leader are selected and whether appointments to high office are personalized. We call this the leader dimension. The second dimension groups together four observable behaviors that measure the extent to which the regime leader controls the supporting political party (if there is one); we call this the party dimension. Finally, there are four indicators of the leader's control over the military; the dimension constructed from this information is the military dimension.

Together, these pieces of information help us assess the extent to which the regime leader has consolidated power over the two organizations—the support party and the military/security apparatus—that are most likely to constrain his rule. The indicators also attempt to capture information on the (often informal) rule used to select regime leadership and important regime personnel, aspects of personalism that need not pertain to the relationship between the leader and the military and support party.

Table 1 lists the 10 individual indicators that we aggregate into the Personalism Index. Each entry in the table is a question that researchers use to code the information captured in the raw variable. The name we give to each indicator is in the parentheses following the question. When coding these questions, the coders look for the first instance in which the phenomena occur and then code the regime as meeting this criterion for the rest of the time the leader remains in power. For example, once the regime leader purges high-ranking officers by imprisoning them or killing them without a fair trial, this item retains a high value for all subsequent years of the leader's time in office.

Table 1 Items used to construct the Personalist Index

We aggregate these ten items into one variable, which we call the Personalism Index, using principle components analysis.Footnote 5 The items most strongly correlated with the Personalist index are: High office, Party exec committee, Rubber-stamp party, and Security apparatus.

Next, we show the evolution of personalism in North Korea in comparative perspective by contrasting the North Korean case with two examples of durable authoritarianism in the same geographic region: China and Vietnam. Then, we trace the historical events in North Korea that constitute concrete, observable manifestations of personalist power. In doing so, we show that the sequence of personalization in the North Korean regime took the form of first subduing the military as an autonomous organization and then usurping power from the supporting political party. Finally, we explain this sequencing of power consolidation by focusing on initial divisions within the military and the regime's backing from foreign powers.

PERSONALIST POWER IN NORTH KOREA IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

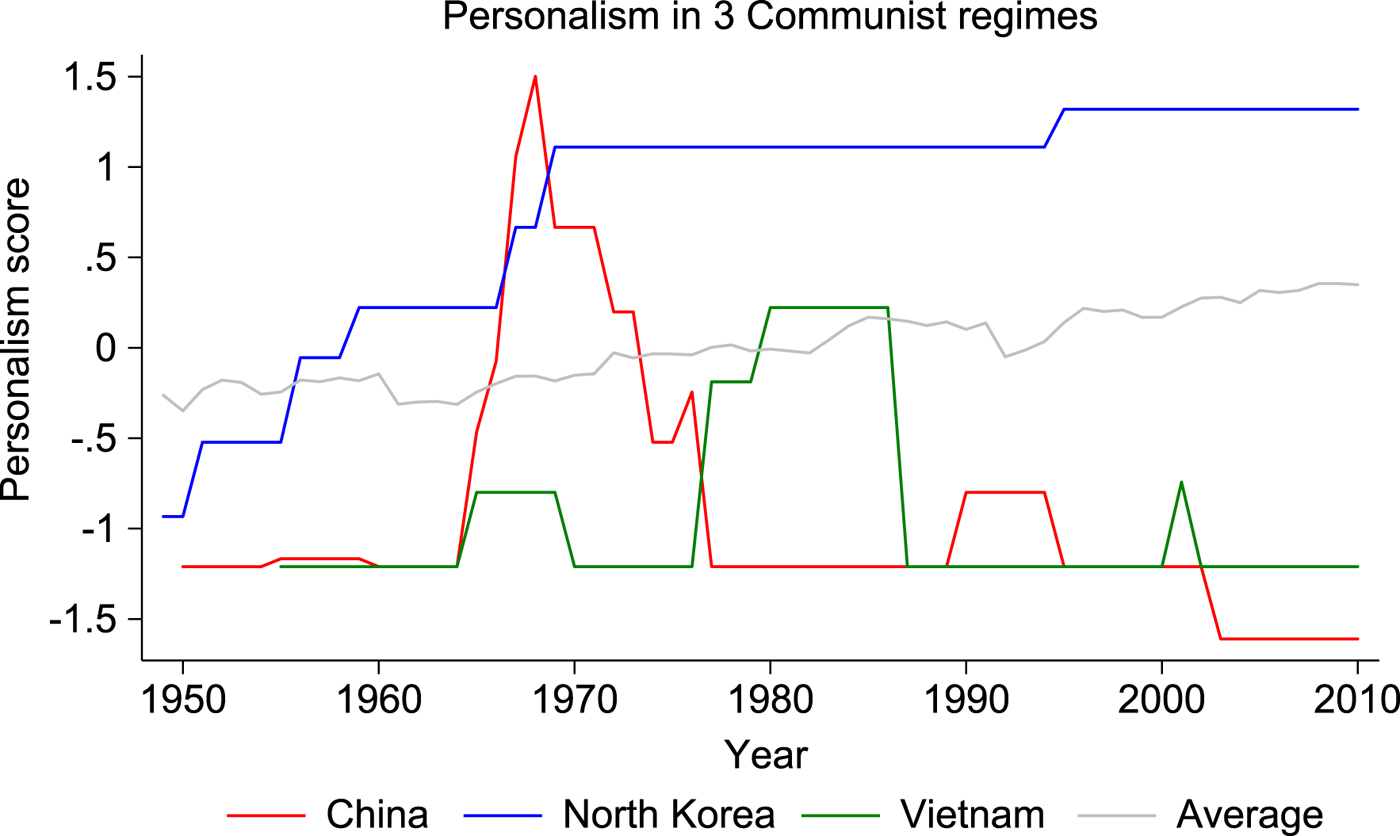

Figure 2 shows the evolution of personalism over time in three communist regimes in the same region. We chose these three regimes to illustrate the evolution of personalism over time in North Korea leading scholars often categorize them in the same way: “revolutionary regimes” (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2013);Footnote 6 “dominant party” or “one-party” regimes by (Geddes Reference Geddes1999; Svolik Reference Svolik2012; Wahman, Teorell, and Hadenius Reference Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius2013);Footnote 7 or “civilian regimes” (Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010; Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Indeed, all three have one-party systems and the military in each has roots in rebel movements.

Figure 2 Personalist power in China, North Korea, and Vietnam

Figure 2 shows the evolution of personalist power over time in China, North Korea, and Vietnam. The colored lines depict the level of personalism, as measured by the previously-discussed index, for each of the three countries. The light gray line shows the average level of personalism among all dictatorships in the world in that year. Including this line in the plot allows us to visually compare the evolution of personalism in specific regimes to the overall trend in personalism.

The plot shows the increase in personalism in North Korea in the 1950s and 1960s that we describe in detail below. The level stays high but stable until after the death of the first regime leader in 1994 and the selection of his son as the succeeding regime leader. The figure also shows the rise and fall of Mao's personal power in China, particularly the sharp increase in Mao's control over the party during the Cultural Revolution and re-assertion of party power in the early 1970s, culminating in the loss of personal power after Mao's death and members of the Politburo arrested Mao's wife and other members of the “Gang of Four.”Footnote 8

Finally, the personalism index is relatively low for the Vietnamese Communist regime throughout the entire post-independence period, except during the decade following the end of the Resistance War against America (Vietnam War) until the leader's death in 1986. The steep increase in personalism in 1977 reflects Lê Duẩn's post-war purge of pro-Chinese factions from the party elite that enabled him to control personnel appointments in the military. However, even the relatively higher levels of personalism under Lê Duẩn after 1976 bring the regime's personalism score only to the average level across all dictatorships during that period. The peak levels of personalism in China and North Korea, in contrast, are substantially higher than average.

The personalist patterns depicted in Figure 2 show that while personalism decreased in China and Vietnam following regime leaders’ deaths (Mao in 1976 and Lê Duẩn in 1986), the North Korean regime leader's natural death in office in 1994 did not bring a new era of party control. Importantly, the CCP had already begun to re-assert its power prior to Mao's death. During the 10th party congress in 1973, for example, the party re-instituted collective vice-chairmanship in the standing committee of the Politburo, stripping Mao of unilateral power to appoint a successor. When Mao died three years later, the party was able to purge the Mao family faction. In Vietnam, the regime leader, Lê Duẩn, never had uncontested personal control over the party apparatus even during the peak years of his power.

In contrast, Kim Il-sung consolidated his power over the party at the October 1966 Party Congress that eliminated the positions of chairman and vice-chairmen of the party, replacing them with one general secretary, namely Kim Il-sung, and ten secretaries.Footnote 9 By 1968—nearly three decades prior to Kim Il-sung's death—the KWP had effectively become a rubber-stamp party (Buzo Reference Buzo1999, 34), with little power to constrain the regime leader's personnel appoints or policy choices. Indeed, the party had no capacity to stop Kim Il-sung from grooming his son as his chosen successor, as early as 1974. The differences in the extent to which the party executive body had power relative to the regime leader at the time of a leader's natural death may therefore help explain why the regime leader's death in China and Vietnam did not result in a new leader selected from the dying leader's family.

THE EVOLUTION OF PERSONAL POWER IN NORTH KOREA

This section discusses how the items used to construct the Personalism Index changed over time in North Korea. We identify both the core concepts (items) that underpin personal power in this case and the historical events that comprise the observable manifestations of personalization.

Of the four items in the party dimension, only two items change over time: Party exec committee and Rubber-stamp party. Kim Il-sung purged the Politburo of rival factions after the Yan'an and Soviet factions’ failed attempt to unseat him in August 1956 (Lankov Reference Lankov2013, 12). His personal control over the party was enhanced further in 1967 when the Kapsan faction—a junior partner to the leader's faction—was purged after their disagreement with Kim‘s policy of simultaneously developing both heavy industries and national defense (Pearson Reference Pearson2013). As noted above, the regime leader gained control over the party after the 1966 Party Congress in which he abolished the positions of chairman and vice-chairmen of the party and replaced them with a general secretary position, which he occupied. By 1968, the KWP had effectively become a rubber-stamp party (Buzo Reference Buzo1999, 32–33). Unlike other highly personalist dictatorships, however, North Korean leaders did not create a new support party or rule by plebiscite.

Similarly, two items for the military dimension increase over time. The regime leader never created a new paramilitary organization under his personal control; but the regime leader is coded as personally controlling promotion of high-ranking military officers from the start of the regime, as Kim was able to fill most of the senior security-related posts with his Manchurian faction members prior to 1948 (Yi Reference Yi2003, 48–49; Lee Reference Lee1989, 84).

The first military item to increase is the Purge indicator, which reflects the ouster of the de facto leader of the Yan'an faction Mu Chong (the commander responsible for the II Corps and Pyongyang's defense) and other division-level commanders such as Kim Han-chung and Choe Kwang in December 1950 after the collapse and retreat of the Korean People's Army (Seo Reference Seo2005, 390).Footnote 10 After the war, the Kim Il-sung grabbed personal control over the security apparatus. Scoring this shift in 1956 corresponds to the 1955 purge of Pak Il-u, the former head of interior ministry, to consolidate control of the international security apparatus (Chen Reference Chen and Palmiotto2006, 459; Minnich Reference Minnich and Worden2008, 277; Gause Reference Gause2012, 97; Lankov Reference Lankov2013, 14). 1955 also marks the year the regime created a military unit—the Pyongyang Defense Command—outside the normal military command structure (Bermudez Reference Bermudez2001; Gause Reference Gause2006). Such a move often proves useful in establishing a counter-weight to the military. Both of these events indicate stronger leader control over the security apparatus.

The increases in the final two items, access to High office and family Leader selection occur at very different junctures in the regime. The former captures the appointment of Kim Il-sung's younger brother Kim Yong-ju as the director of the KWP's the Organization and Guidance Department, one of the most powerful organizations within the party responsible for imposing party controls over military and government institutions (Madden Reference Madden2009; Hwang Reference Hwang1999). The shift in the Leader selection item occurs in 1995, following the selection of the first regime leader's son as the new regime leader in 1994: Kim Jong-il replaces his dead father, Kim Il-sung. This shift in the Leader selection variable is significant because it contrasts sharply with other Communist regimes (except Cuba) where personalization under a dominant regime leader (e.g. Stalin or Mao) did not result in family leadership succession. Solving the leadership succession issue in this manner is relatively common in highly personalized autocracies,Footnote 11 but it is rare in regimes that, prior to seizing power, had a supporting political party or a military formed from rebel groups.

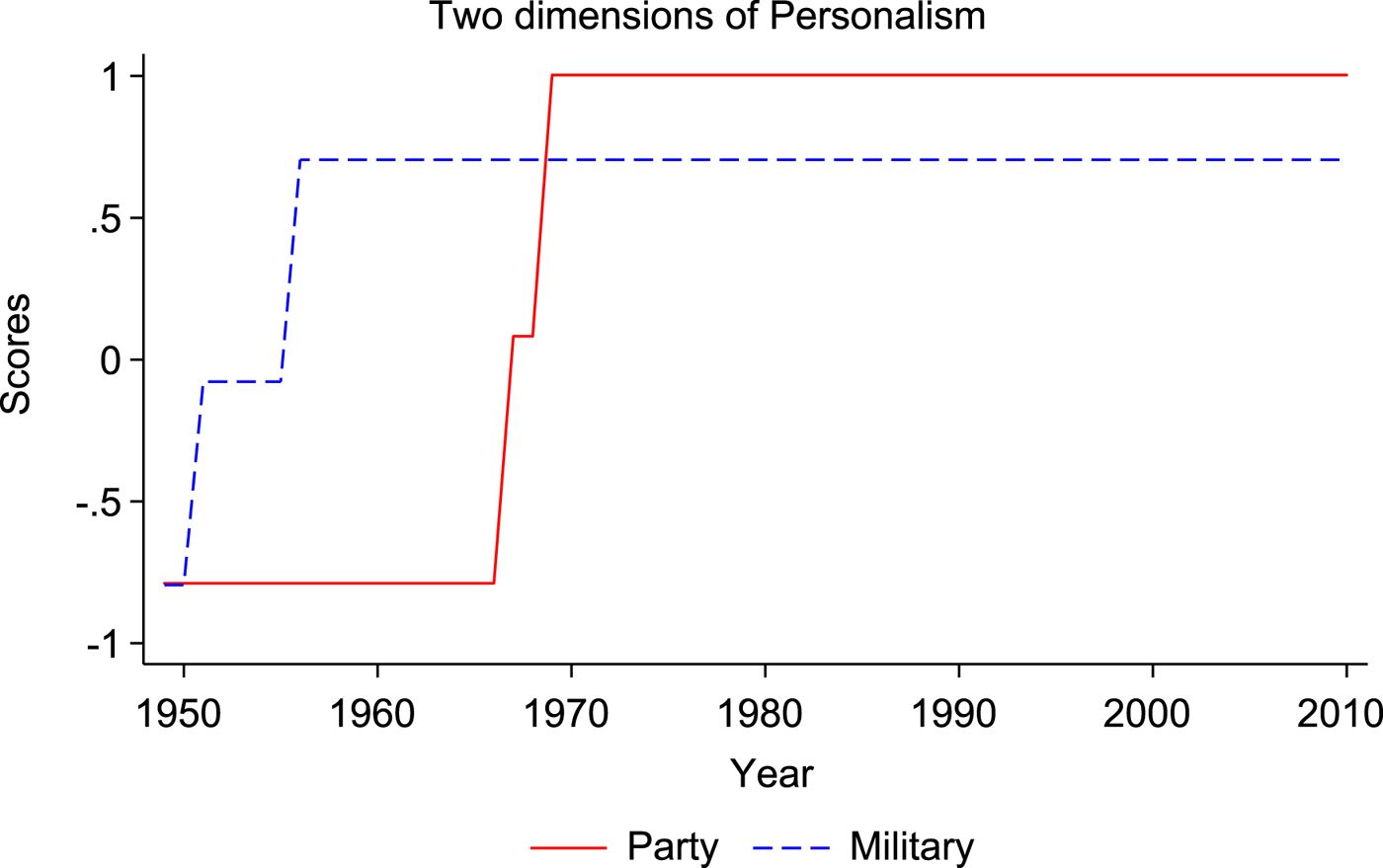

Figure 3 shows the sequence of personalization in North Korea: consolidation of power over the military occurs prior to personalization of the party. Next, we explore how the initial factionalization of the seizure group, combined with the presence of foreign troops allowed Kim to take personal control over the domestic military and internal security apparatus with less fear of reprisal from the military.

Figure 3 The sequence of consolidating personalist power

HOW DID KIM IL-SUNG PERSONALIZE POWER?

The North Korean state was created by the Soviet Union after it defeated Japan during the Second World War. Initially, the regime “operated under the complete control of Soviet advisers,” and Stalin reportedly edited a draft of the first North Korean Constitution (Suh Reference Suh1988, 62–63; Lankov Reference Lankov2013, 6).Footnote 12 Unlike the current personalist dictatorship, the initial North Korean regime was supported by various factions in a power-sharing arrangement. Kim Il-sung's group, known as the Manchurian faction, was drawn from anti-Japanese guerilla fighters who had spent the early 1940s in the Soviet Union, many as members of the Soviet military's 88th Brigade.Footnote 13 A second group, the Yan'an faction, was comprised of Korean communists who fought with the Communist Party of China against Japan and the Nationalists during the late 1940s. A third group was a Soviet faction comprised of Soviet officials of Korean descent who were dispatched by Moscow from Central Asian Soviet states as the Soviet army entered the Korean Peninsula. A final group, the Domestic faction, consisted of communist activists who had fled repression on the southern part of the peninsula.

In what follows, we show that the Kim Il-sung consolidated control over the security forces in part because the regime had two foreign patrons, the Soviet Union and China. Though ostensible allies during the late 1940s and early 1950s, these patrons competed for influence in the new regime, allowing Kim Il-sung to purge elite members of various factions with less fear of backlash in the form of a coup. Crucially, the Soviets gave Kim Il-sung a virtual monopoly on domestic armed groups in the early stages of regime consolidation, thus enabling Kim to prevent cooperation between Yan'an faction military elite and Chinese military commanders.

SECURITY ORGANIZATIONS UNDER SOVIET OCCUPATION OF THE NORTH

In the first months after the Soviet advance and the Japanese retreat, three volunteer security organizations sprang up, each led by different Korean (i.e. non-Soviet) factions (Kim Reference Kim2018, 120). However, the Soviets quickly ordered all domestic security organizations to hand over weapons and demobilize in October 1945. At the time, the Soviet occupation commanders wanted Kim Il-sung to control security because they knew him from his stint in the 88th Brigade of the Soviet military. Thus after appointing Kim head of the People's Committee in February 1946, the Soviets authorized Kim to organize a new security force via the People's Committee (Lankov Reference Lankov2002a, 59). Kim had a monopoly on all non-Soviet armed groups in the North.

In that same month, the Soviets prevented Korean communist troops stationed in China from entering Korea. Soviet forces disarmed perhaps as many as 2,000 soldiers from the Korean Volunteer Army after they crossed the Amnok (Yalu) River on the Chinese–Korean border, with most of this force returning to Manchuria (Suh Reference Suh and Hammond1975, 481; Suh Reference Suh1988, 68–69; Lankov Reference Lankov2002a, 81; Minnich Reference Minnich2005, 27; Kim Reference Kim2018, 52). One motivation for this move may have been to prevent the Yan'an faction, which the Soviets viewed as closer to China than the Soviet-imposed regime in North Korea, from gaining control over a large armed group (Scalapino and Lee Reference Scalapino and Lee1972, 334; Minnich Reference Minnich2005, 27). Irrespective of the motivations for this move, the Soviet occupation force nonetheless defanged an armed group that could potentially challenge Kim's increasing monopolization of personnel decisions atop the nascent North Korean security organizations.

Thus, Kim did not inherit an established military when the Soviets handed him power, but rather was charged with creating new military and security forces by s foreign occupation administration. In contrast to most new regime leaders who come to power via force, Kim was not part of an established guerrilla force nor the leader of an institutionalized military organization.Footnote 14 From the beginning, there were no groups of armed Koreans, no domestic security organizations, nor any armed vestiges of Japanese rule with whom Kim had to bargain when tasked by the Soviets with establishing his rule. Indeed, the largest armed group of Koreans in 1945 was the Korean Volunteer Army (KVA), a unit of perhaps as many as 4,000 soldiers, including many who had fought with the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) in the early 1940s, stationed in China (Kim Reference Kim2018, 40).

Kim filled the ranks of the first security organizations with former guerrilla comrades who had served with him in the Soviet 88th Brigade, though Korean soldiers who has spent most of the Chinese Civil War in Yan'an filled some positions (Kim Reference Kim2018, 42–54). Soviet Koreans who arrived from Central Asia, however, were mostly interpreters and education specialists, with few joining Kim's early security forces (Lankov Reference Lankov2002a, 125–126). In 1946, the Soviets created the first units of new North Korean army as “police and railway defence units,” while Kim opened the first officer training school in Pyongang, under the command of Kim Ch'aek (Kim Reference Kim2018, 123).Footnote 15 The official declaration of an independent North Korean People's Army (KPA) and corresponding Department of National Defense came in February 1948 (Lankov Reference Lankov2002a, 37). The top two positions went to Kim partisans, Kang Kon as the Chief of Staff of the military and Choe Yong-gon as the first head of internal security (later the Ministry of Interior) (Lankov Reference Lankov2002a, 37; Szalontai Reference Szalontai2005, 15).Footnote 16 The North Korean political police were headed by Pang Hak-se, notably one of the few Soviet Koreans initially atop a key security organization (Lankov Reference Lankov2002a, 38).

When the Soviets withdrew their last divisions from Korea in late 1948, North Korean security forces numbered over 60,000 troops, with nearly as many internal security force personnel (Suh Reference Suh1988, 103; Minnich Reference Minnich2005, 39–40). During the next two years the KPA's size would nearly double, with most new KPA soldiers, who were ethnic Koreans, coming from China as the Chinese Civil War came to a close (Chen Reference Chen1994, 110; Kim Reference Kim2018, 128; Minnich Reference Minnich2005, 53–54). The arrival of ethnic Korean PLA units brought combat-hardened units that were vital for Kim Il-sung to achieve his military objective of “national unification” of the peninsula. However, the newly arrived troops were also potential threats to Kim Il-sung because the Yan'an faction was the only armed group with the capacity to carry out a coup against the North Korean leader. Kim Il-sung's first efforts to consolidate power, therefore, meant keeping members of the Yan'an faction from taking important military posts in the newly created armed forces (Lee Reference Lee1989, 84; Kim Reference Kim2018, 52). Efforts to marginalize the Yan'an faction proceeded apace during the Korean War, part of Kim's strategy to “use the war to strengthen his personal power” (Lankov Reference Lankov2002a, 148).

Therefore, the origins of the North Korean military did not lie in a relatively cohesive rebel group that fought together for sustained period of time, as was the case of the PLA in China or the Vietnamese People's Army (VPA). While many senior appointments in the KPA were guerrilla veterans who fought with Kim Il-sung in Manchuria during the 1930s, this group suffered a devastating defeat by the Japanese and fled to the Soviet Union as exiles in late 1940 (Kim Reference Kim2018, 43). Rather than a victorious guerrilla movement, the KPA was the creation of the first regime leader. And while Kim selected many partisans to senior positions in the military, the KPA's military might lay with the leadership provided by experienced commanders from the Yan'an faction and foot soldiers from the Korean Volunteer Army.

PREVENTING CHINESE-KOREAN COORDINATION DURING THE KOREAN WAR

The early months of the Korean War provided Kim with an opportunity to further consolidate power over the military. As importantly, Kim prevented the Chinese military from coordinating with his own forces until early 1951, permitting Chinese command of the war effort only when his military faced total defeat and after he had purged numerous senior officers from both his faction and the rival Yan'an faction.

Both prior to and during the initial stages of the Korean war, “the North Korean leadership steadfastly refused to accept Chinese offers of assistance until forced to do so by the U.N. advance across the 38th parallel” (Shen, Reference Shen2004, 9). During Kim's courting of Stalin for permission to attack the South, Stalin wanted assurances that Soviets troops would not have to intervene if the KPA invaded the South. Kim argued that Chinese troops were unnecessary, arguing “that his own forces were sufficient” (Shen, Reference Shen2004, 9). At Stalin's insistence, however, Kim was only proceeded with invasion plans once the Soviets were assured that Chinese troops would back the KPA should the US intervene.

Once hostilities began on June 25, 1950, Kim continued to keep the Chinese at a distance. The Chinese liaison with the North Koreans, Chai Chengwen, knew little of KPA battle plans or events in the field. And although Chai received daily briefings from the KPA Political Department, these were simply repackaged public information from the Korean Foreign News Service, and he quickly “formed the opinion that they [North Koreans] had been forbidden from sharing any military intelligence with the Chinese” (Shen, Reference Shen2004, 10). As Kim (Reference Kim2018, 121) notes, the Yan'an faction leaders, including Mu Chong, were not “allowed to enter the secret situation room and to read the invasion plans; the Chinese liaison officer was similarly excluded.” In short, Kim ensured there was little room for coordination between the KPA and Chinese military forces during the early months of the conflict.

However, after the US entered the war and ROK-US forces advanced on Pyongyang in October 1950, KPA defeat looked immanent. This forced North Korean leaders to appeal to the Soviet Union for direct military intervention. Stalin, however, insisted that Chinese forces come to the rescue (Shen, Reference Shen2004, 11). The Chinese Volunteer Forces (CVF), commanded by PLA veteran Peng Dehuai, crossed the Yalu River into Korea in late October, with their first major offensive against UN forces beginning in late November.

Even after reluctantly accepting the Chinese aid, Kim Il-sung still stymied KPA–CVF military cooperation. In fact, coordination was so poor that once CVF units entered the fray, KPA troops mistakenly attacked them on several occasions in the early going (Shen, Reference Shen2004, 12). As Chinese frustration with the war effort mounted, the Soviets pressed Kim to cooperate, and a joint KPA–CVF command structure for the militaries was agreed upon in early December 1950. However, the joint command was not implemented until early the next year (Shen, Reference Shen2004, 11). Between agreement and implementation of a joint command, the KWP met for an emergency Third Plenum of the Second Congress, where Kim Il-sung dismissed Mu Chong, the leading military officer from the Yan'an faction, as the commander the KPA's 2nd Corps (Chung Reference Chung1963, 115; Suh Reference Suh1988, 122).Footnote 17 While Kim's stated rationale for Mu's sacking was poor performance on the battlefield, “Kim Il Song may also have assessed that Mu's Chinese military connections from the per-1945 period were a potential threat’” (Buzo Reference Buzo1999, 21).Footnote 18 Indeed, prior to returning to Korea, Mu Chong had been the commander of the Korean Volunteer Army (KVA) (Kim Reference Kim2018, 40). Thus prior to allowing senior officers from the KPA and CVF to communicate about military operations in the same room, Kim sacked the highest-ranking KPA commander from the Yan'an faction.

By the time the Chinese CVF command took joint control over the war operation in January 1951, Kim had not only sacked the highest-ranking military commander from a rival faction (Mu Chong), but all the top field commanders of the KPA were gone. Two partisan generals, Kim Ch'aek, the commander of the Front Army, and Kang Kon, the commander of the 1st Corps, were killed in battle.Footnote 19 Kim Il-sung also demoted three of his closest allies, all members of his own Manchurian faction, during the December 1950 Plenum: Kim Il, the top political commissar in the military who had spent much of WWII in the Soviet 88th Brigade with Kim Il-sung; Choe Kwang, commander of the 1st Division; and Kim Yol, Chief of the Rear Service Bureau, charged with protecting Pyongyang (Suh Reference Suh1988, 122, 142, 358).Footnote 20 While Mu Chong was permanently purged, many of Kim's partisans who were sacked in December 1950 were later rehabilitated. Nonetheless, Kim Il-sung demonstrated, as early as December 1950, the power to unilaterally purge top military officers, even leading officers from own faction, thus establishing his control over personnel appointments to security positions. The most senior military officers atop the KPA at the start of the war, with the exception of Defense Minister Choe Yong-gon, were gone. If the CVF commanders were to collude with KPA leaders to oust Kim Il-sung, they would have work with freshly appointed field commanders, not the senior officers who commanded troops at the start of the conflict.

FURTHER CONSOLIDATION

After expelling the leader of the Yan'an faction from the military, the presence of PLA troops, who ostensibly backed Kim Il-sung, enabled him to further consolidate power over the domestic security apparatus. While Kim had reluctantly handed over the operational control of KPA to China, this move also freed up his responsibilities from warfighting to concentrate on personalizing the internal security apparatus and the party leadership (Choi Reference Choi2009). In November 1952, Kim removed Pak Il-u—then the top security official from the Yan'an faction, the chief liaison between the Kim regime and the Chinese forces during the war, and the only Yan'an member on the seven-man military council (Shen, Reference Shen2004, 12)—as head of the Interior Ministry (Central Intelligence Agency 1953; Szalontai Reference Szalontai2005, 245–246). After the war, in 1955, Kim Il-sung purged Pak Il-u from the regime entirely, under the charge of “conspiring to expand his personal power base with the Chinese support” (Lee Reference Lee2014, 29). In the same year, Kim also established the Pyongyang Defense Command as the first military unit outside the normal command structure of the military. Both moves provided Kim control over security organization to counter potential military backlash as he further consolidated power.Footnote 21

Kim also used the early war period to marginalize other factions. After North Korean and Chinese forces regained territory that had been occupied by US–ROK troops in late 1950 to early 1951, Kim instructed the most prominent party member in the Soviet faction, Ho Ka'i, to purge members of the Domestic faction from the KWP (late 1951). Because they had been in the occupied territory after the US advance, Kim employed the pretext of treason to purge them. As Lankov (Reference Lankov2002a, 102) notes, the Domestic faction “was eliminated mainly by the former guerrillas, with a degree of support and participation from the Soviet and Yan'an factions whose members hoped to use the opportunity to strengthen their own position.” Factionalization thus not only prevented coordination among competing groups but also allowed Kim to pit one group against the other.

Then, after using Ho Ka'i to neuter the Domestic faction, Kim purged Ho, in the process ousting the strongest potential challenger in the ruling party from the Soviet faction (Suh Reference Suh1988, 124). Notably, during these early party purges, elites from the Domestic and Soviet factions did not have a large armed group of supporters within the military; and Chinese—not Soviet—troops remained the largest group of armed actors throughout.Footnote 22 Thus, Kim purged the most serious Yan'an faction challengers in the military prior to allowing KPA–CVP cooperation, and only purged the Soviet faction leaders in the KPW once the Soviets had completely withdrawn their forces and Stalin had pledged not to send troops to the Korean peninsula again.

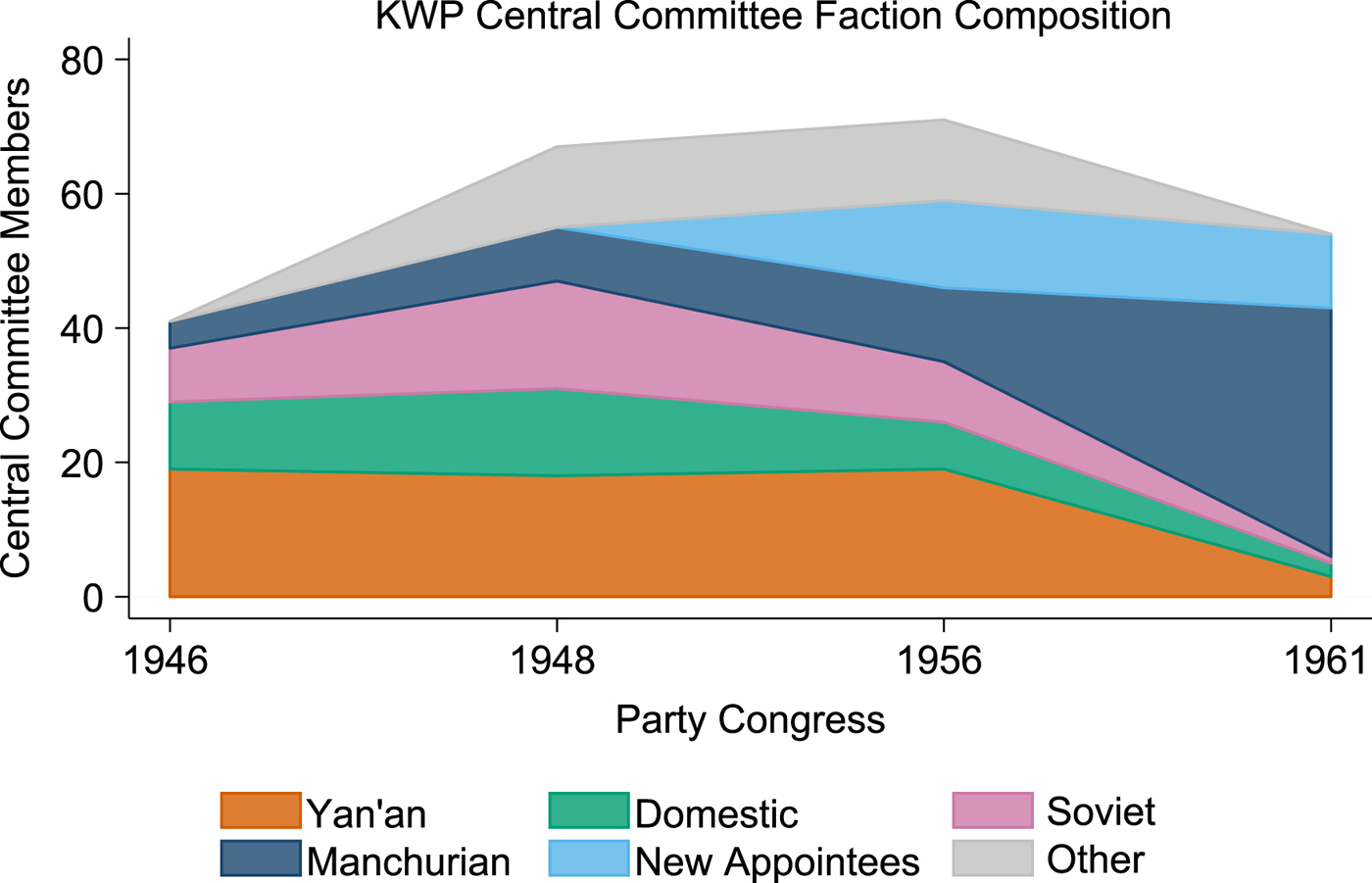

Perhaps the strongest challenge to Kim from the KWP came in 1956, when members of Yan'an and Soviet factions, encouraged by Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalin, attempted to unseat Kim Il-sung.Footnote 23 During the 3rd Party Congress of the KWP in April, which was held shortly after the first post-Stalin Soviet party congress, Kim gave a nod to collective party leadership but managed to place many new—and loyal—comrades on the KWP Central Committee, mostly at the expense of the Soviet and Domestic factions (see Figure 4), whom Kim continued to denounce.

Figure 4 Factions in the KWP Central Committee

Conspirators took the opportunity of Kim's visit to the Soviet Union in early July to plan their move to re-assert party control by institutionalizing collective leadership within the KWP.Footnote 24 Plotting party leaders of both opposition factions—Yan'an and Soviet—met with the Soviet ambassador when Kim was out of the country (Lankov Reference Lankov2002a, 158–160.) However, the conspirators were unable to win over all Yan'an faction members and failed to get the head of the political police, Pang Hak-se, a former Soviet faction member who remained loyal to Kim throughout, on board (Lankov Reference Lankov2002a, 162). Kim caught wind of the plans from allies and strategically postponed the Plenum to organize his own supporters prior to the crucial party meeting (Lankov Reference Lankov2002a, 164–165).Footnote 25

Kim survived with his position intact and subsequently purged most members of the Yan'an and Soviet factions, except the few who were personally loyal to him. A joint Chinese–Soviet delegation—comprised of Khrushchev's top aide, Anastas Mikoyan, and the commander of PLA troops in Korea, Peng Dehuai—was sent to Pyongyang to demand Kim reinstate the members of the ousted factions. Kim pledged he would cease the purges and make conciliatory remarks at the September Plenum; but the joint delegation left having stopped well short of preparing the way for Kim's exit from power (Lankov Reference Lankov2002b, 92). Radchenko (Reference Radchenko2017) notes that Mikoyan was in North Korea in September 1956 to organize a path forward without Kim, but Soviet action would require Chinese approval. Indeed, the PLA still had over 400,000 troops stationed in North Korea at the time (Shen, Reference Shen2008, 22). In the end, Mao “warned the Soviet envoy they should not try to topple [Kim]” (Radchenko, Reference Radchenko2017). Without patron cooperation, domestic challengers stood no chance.

The subsequent 1957–58 purges paved the way for Kim's faction to dominate the KWP. The Manchurian group was a minority faction at the 1st and 2nd Congresses of the Korean Workers’ Party in the late 1940s, for which the Yan'an faction had the highest number of delegates, followed by members from the Domestic and Soviet factions (Wada Reference Wada and Lee1992, 305–307; Seo Reference Seo2005, 178–179, 217). However, as Figure 4 shows, by the 4th Congress in 1961 Kim's faction dominated, with the combined representation of the rival factions on the Central Committee falling to less than 10 percent of the total. With rival factions almost completely eliminated from the KWP leadership, Kim would complete his control over the party by 1968, after he abolished the positions of chairman and vice-chairmen of the party (1966), replacing them with a general secretary position.

In short, the presence of two foreign powers backing the regime against external threats provided the regime leader with both an opportunity to consolidate power over the military and internal security apparatus and an incentive to do so. To prevent potential collusion between a foreign military and the strongest rival faction of the military, Kim Il-sung purged the leader of the rival faction before allowing Chinese and Korean forces to cooperate. Foreign troop presence also allowed the regime leader to consolidate power over the domestic military precisely because the domestic military was not the primary deterrent to external threats; early on Soviet forces provided this deterrent and from 1951 to 1958, Chinese forces served this purpose. As important, during the period of military and party purges in the 1950s, the foreign troops in North Korea were not from the most powerful regional hegemon, namely the Soviet Union. Indeed, a foreign-backed coup led by the Yan'an faction might have met resistance from the Soviet Union.Footnote 26 Indeed, Chinese troops did not leave North Korea until well after the close of the Korean War, and not until Kim had purged senior Soviet faction members from the KPW.Footnote 27 As Suh (Reference Suh1988, 154) notes, “[b]y the time the Chinese Volunteer Army left Korea on March 11, 1958, Kim and his partisans had more or less eliminated every group capable of challenging him.”

DISCUSSION

Our account of personalization in North Korea suggests that two foreign patrons and, importantly, the presence of foreign occupation troops increases the probability that autocratic leaders personalize the security apparatus. However, why would the foreign patron permit personalization?

One answer is that the patron does not care about personalization in the client state: the patron(s) may have no normative preference for an institutionalized, rather than a personalized, security apparatus in the client state; or the patron(s)’ preference for stability in and compliant international behavior of the client state outweighs preferences about the military structure of the client. This may help explain Soviet behavior shortly after Japanese retreat. The Soviet military administration likely preferred Kim Il-sung as the leader of the new client state to other potential candidates, particularly those from the Yan'an and Domestic factions.Footnote 28 Perhaps the best evidence for this lies in Soviet insistence on disarming the returning members of the KVA in 1945. As Kim (Reference Kim2018, 121) notes, “Kim Il-sung shared the Soviets’ anxiety concerning the possible influence of the returning pro-Chinese Korean communists.” This suggests shared preferences, at least in the late 1940s, between patron and client laid the groundwork for personalization. Similarly, in 1956 during the plot to oust Kim, the Chinese likely preferred Kim, despite misgivings about the nature of his rule, to a new Soviet-installed puppet (Radchenko Reference Radchenko2017).

A second answer lies in the classic principal–agent problem, where the actors’ preferences diverge. In this framework, the agent (Kim Il-sung, in this case) realizes his preferences even if they contravene the principal's (Soviet Union and later China) preferred outcome for one of two reasons: either the agent has better information about effort and outcomes, or the patron, even with accurate information about outcomes, lacks credible enforcement mechanisms. It is unlikely the Soviet military administration lacked accurate information about Kim's moves to assert control over nascent military and security organizations. Indeed, the Soviets facilitated the early marginalization of Yan'an military elites and helped orchestrate Chinese participation in the Korean War effort. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s the Soviet Union also had substantial power to coerce compliance with their preferred outcome in the client state. Soviet troops did not withdraw until 1948; and Soviet military aid and training was instrumental in developing a military strong enough to invade the South. During and after the war, Soviet aid continued apace. Just prior to the August 1956 attempt to reassert party power by institutionalizing collective decision-making, Kim had been in Moscow asking for aid (Suh Reference Suh1988, 149). At least at this point, Kim was vulnerable both to the coercive power of the Soviets and to domestic opponents in the KWP. The fact that the Soviets (and the Chinese) attempted to reinstate purged KWP members after the August challenge suggests that the patrons preferred less personalization in 1956.

However, the foreign powers stopped well short of undermining Kim's rule, which suggests the patrons cared more about stability than preventing Kim's consolidation of power. Indeed, Lankov (Reference Lankov2002a, 185) suggests that “political stability of the DPRK inevitably worried the Soviet diplomats”; they only would have considered replacing Kim if “such actions did not jeopardize the stability of the easternmost Communist country … a protective buffer between the US troops stationed in South Korea and the vital industrial regions of Chinese Manchuria and the Soviet Far East.”Footnote 29 Indeed, if the Soviets thought they could control Kim, but credible enforcement was too costly for the patron to implement, particularly given an over-riding preference for stability, this would leave Kim considerable latitude to personalize the regime.Footnote 30

A third answer lies in the presence of dual patrons. Multiple patrons with coercive power presents domestic actors who prefer to remove the leader with a colossal collective action problem. Lankov's (Reference Lankov2002a) account of the August 1956 challenge to Kim, largely based on de-classified Soviet documents, indicates that the conspirators communicated frequently with the Soviet embassy, which may have been the source of Kim's knowledge of the plot. Lankov further argues that the Yan'an faction conspirators would undoubtedly have sought counsel from the Chinese as well, though similar Chinese documents that might confirm as much are unavailable. Unilateral action by one of the patrons to remove Kim would have been difficult. While counter-factual scenarios cannot establish positive evidence for conjecture, it is hard to imagine an anti-Kim faction plotting with the Soviets to execute a coup without Chinese consent, with over 400,000 PLA troops stationed in North Korea.

Finally, multiple foreign patrons with a troop presence in the client state provides the client leader with a buffer against hostile external intervention. To the extent that personalization of the military hurts military combat power, and thus deterrence against potential external threats, client leaders who rely on foreign troops to protect them have more room to personalize without fear of comprising the capacity to deter the external adversaries. When Kim sacked the most experienced KPA military commanders in December 1950, Chinese forces had already launched their initial offensive against UN forces.

In short, evidence from the North Korean case suggests that the reliance on two foreign patrons, including the presence of foreign occupation troops, likely contributed to personalization of the Kim regime. There is also some evidence the patrons, at least at certain points during Kim's consolidation of power, valued North Korean stability over the possible negative consequences of personalization. We leave future research the task of assessing the relative strengths of these arguments using a broader array of cases.

CONCLUSION

This study traces the historical evolution of political power in North Korea during the past 60 years. We place this historical trajectory in comparative authoritarian context to understand the types of political events that constitute manifestations of personalism that are meaningful in a variety of distinct contexts.

The North Korean regime is relatively unusual among dictatorships because it is both very durable and highly personalized. We show that the initial conditions from which the regime was born largely explain the trajectory of personalism in this case. The presence of two foreign backers enabled the first regime leader to consolidate personal power by wresting power from the military. Kim Il-sung first purged the most senior commander from outside his faction in December 1950 and then grabbed personal control of the internal security apparatus by 1955. Not until the 1960s did he successfully transform the Korean Workers’ Party into an instrument of personal power.

This sequence of personalization, we argue, may be relatively unique because two foreign powers backed the regime during the 1950s. The presence of Chinese troops in North Korean meant that the Korean People's Army was not the primary deterrent to external threats, allowing the regime leader to attack the domestic military. Equally important, these foreign Chinese troops were not from the most powerful regional hegemon; thus, a foreign-backed coup supported by Chinese troops was less likely to be successful. This combination provided the regime leader with an opportunity to establish personal control over the internal security apparatus without provoking military backlash. The longevity of the Kim regime can be explained, in part, we argue, by the relatively unique sequence of historical circumstances that led to the early personalization of a regime that came to power with both a pre-existing, though newly formed, political party and a factionalized military with elites drawn from a distinct guerillas groups.