Introduction

During the initial phase of Operation Enduring Freedom, Pentagon officials held a daily briefing for journalists that followed a similar format each time. The briefings started with impressive gun-camera images of precision-guided munitions striking Taliban convoys followed by a detailed overview of the targets that were struck, the aircraft that were involved and the munitions that were dropped. Absent from these briefings, however, was any mention of the people who were killed. The Wall Street Journal accused the Pentagon of avoiding the subject of civilian deaths, noting that ‘officials say they don't know … how many civilians have died when American bombs went astray’.Footnote 1 Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld responded to these allegations later that day, rejecting the accusation that the Pentagon was avoiding the issue. Rumsfeld claimed that ‘with the disorder that reigns in Afghanistan, it is next to impossible to get factual information about civilian casualties’.Footnote 2 On the one hand, the military was unable to conduct its own investigations because these sites were often in enemy-controlled areas. Even when investigators were able to access these areas, Rumsfeld argued that ‘it is often impossible to know how many people were killed, how they died, and by whose hand.’ On the other hand, Rumsfeld said the Taliban were lying about civilian casualties, insisting that ‘they intentionally misled the press for their own purposes.’Footnote 3

Pentagon officials might have been reluctant to release their figures, but they were counting casualties. The military used sophisticated collateral damage software to estimate potential harm when planning attacks and units were expected to count casualties – both combatant and non-combatant – when completing routine battlefield damage assessment reports.Footnote 4 Nevertheless, counting casualties was not prioritised during this period, with troops receiving little guidance about what data needed to be collected or the importance of collecting this data.Footnote 5 As a consequence, military estimates were often incomplete and inaccurate, with commanders unable to contest outside reports with figures of their own.Footnote 6 But things started to change as the conflict progressed. In 2008, General David McKiernan created the Civilian Casualty Tracking Cell (CCTC) to ensure that commanders had timely and accurate information about instances of civilian harm. The following year, General Stanley McChrystal introduced new standard operating procedures for counting casualties to ‘ensure that all available facts are presented, and that analysis and assessment is conducted with discipline and rigor’.Footnote 7 And in 2011, General John Allen created the Civilian Casualty Mitigation Team (CCMT) to conduct more detailed analyses of civilian casualty trends to identify tactical lessons that might be learned. Following his stint with the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), General Joseph Dunford was able to claim that counting casualties had become ‘core business’ within the coalition, providing commanders with the ‘statistical and analytical basis [for a …] comprehensive understanding of trends’.Footnote 8 Coalition officials had gone from not counting civilian casualties, to counting them in fastidious detail.

The importance ascribed to counting casualties has largely been overlooked in the existing literature, which has focused almost exclusively on the decision not to count civilian casualties.Footnote 9 As a consequence, we lack basic information about what the coalition counted, how these counts were conducted, and what it hoped to achieve with this data. This article will correct these empirical oversights with a detailed examination of coalition figures, the procedures used to collect these figures, and the policies and practices that were adjusted in accordance with this data. My findings are based on a detailed analysis of more than 25 coalition texts, including various tactical directives, lessons learned reports, and recently declassified training material. I have also conducted more than twenty interviews with members of the coalition, including senior ISAF commanders and former CCTC/CCMT personnel. These individuals were selected because they were either involved with the formulation and implementation of these policies or were responsible for collating and analysing the data on civilian casualties. For the purposes of this article, I am interested in the rationale that underpinned the decision to count civilian casualties and what the coalition thought it could do with the data, rather than assessing the methodological rigour of coalition counts or the accuracy of coalition figures.Footnote 10 In this respect, my approach could be viewed as a form of what the anthropologist Laura Nader referred to as ‘studying up’ because I am interested in what prompted the coalition to start counting casualties, how officials tried to use the data, and what it reveals about their attitudes towards civilian harm.Footnote 11 Interviewing those directly involved with these policies, enabled me to gain a better understanding about what they were doing and why they were doing it, while giving me an opportunity to ask more detailed about questions about how these counts were conducted.

This article makes an important theoretical contribution to debates about the relationship between numbers and international security.Footnote 12 Building on the work of Sally Engle Merry and Arjun Appadurai, I argue that coalition counts did more than simply document the death and destruction inflicted on Afghan civilians, but were also complicit in the violence that was being counted. This article explains how these counts were used to ‘manage’ the problem of civilian harm, providing commanders with data that could be used to contest allegations they considered untrue and to contextualise allegations they considered inaccurate. I will focus particular attention on how commanders used this data to calibrate the violence they inflicted, ensuring that they could continue to kill insurgents without causing unnecessary harm to civilians, which might turn potential allies into adversaries. As the coalition started to reimagine civilian casualties as a strategic problem rather than a purely moral or legal concern, I will explain how coalition commanders sought to use data on civilian casualties to enhance both the effectiveness and the efficiency of military operations. The term ‘calibrate’ is particularly useful here because it refers to the ways in which certain things – in this case, violence – can be compared to certain standards and adjusted to ensure that it meets these standards. The Oxford English Dictionary, for example, talks about how certain instruments can be calibrated to remove any irregularities or ensure that these irregularities are kept within certain acceptable limits. The term also has certain martial connotations as it refers to the diameter of bullets and other projectiles, which has a significant bearing on the harm this ammunition can inflict.

I will draw on these two meanings to explain how the coalition sought to use civilian casualty data to calculate, regulate, and evaluate the violence inflicted in Afghanistan, with officials using these figures to ensure they had sufficient firepower to eliminate insurgents without jeopardising mission success. The article begins with an overview of recent work on counting casualties, which focuses on the importance of counting casualties and the methodological problems that are often encountered. The second section outlines the broad theoretical assumptions that animate my analysis, which focuses on what these counts do rather than what they show. In particular, I am interested in how these counts worked to constitute civilian harm as a problem, which could then be managed or mitigated by the coalition. The remainder of the article explains what prompted General McKiernan to create the CCTC, how General McChrystal sought to standardise this data, and how the CCMT used this data to calibrate the violence inflicted. In doing so, I will argue that the coalition were concerned with enhancing the effectiveness of military operations rather than highlighting the pain and suffering inflicted upon ordinary Afghans. Although counting civilian casualties is often seen as a way of humanising contemporary conflict, I will argue that coalition counts continued to dehumanise the Afghan civilians because they treated them as a means to an end rather than an end in themselves.Footnote 13 Put simply, I will argue that coalition counts were never really concerned with accounting for the harm inflicted upon civilians, but were used to make coalition operations more prudent, more potent and productive.

(Not) counting casualties

Counting civilian casualties has always been a contentious issue, but it is the refusal to count that has provoked the most interest because it is unclear how militaries can be held accountable if we do not know who they are killing or the circumstances surrounding their deaths. Several legal scholars claim that it is difficult to determine whether attacks are lawful without access to accurate information about the casualties inflicted because the principles of proportionality and distinction requires some knowledge about how many people were killed and the identities of those who died.Footnote 14 Others argue that the refusal to count represents an attempt to conceal the destructiveness of military operations and the devastating impact on civilians.Footnote 15 When General Norman Schwarzkopf declared that he was ‘anti-body count’ during Operation Desert Storm, Margot Norris argued that he was engaging in a form of ‘pre-censorship … with its deliberate aim of transforming the real-making sign of warfare – namely the injured and dead body – into an unreality’.Footnote 16 Norris argued that rendering these bodies unknowable ‘threatens to de-realise modern warfare in ways that will make it permanently acceptable’.Footnote 17 Similarly, when General Tommy Franks announced that ‘we don't do body counts’, Marc Herold argued that this omission would give ‘rein to the enthusiasts of precision-guided weaponry [while making …] it impossible for the families of those wrongfully killed to get the compensation to which they are entitled’.Footnote 18 Put simply, counting was crucial when it came to holding militaries accountable, so the refusal to count civilian casualties could be seen as an attempt to evade accountability.

One recurring theme in the literature is the idea that refusing to count casualties suggests that the military does not value the lives of civilians, even those they claim to be protecting.Footnote 19 Didier Fassin, for example, argues that an important distinction can be drawn between the sacred lives of Western soldiers, whose deaths are counted and honoured, and the deaths of non-Western civilians, ‘whose losses are hardly tallied and whose corpses sometimes end up in mass graves’.Footnote 20 John Sloboda et al. argue that militaries have an obligation to count casualties, claiming that ‘it is a matter of simple humanity to record the dead’.Footnote 21 While they acknowledge that recording civilian casualties is unable to capture the significance of each loss, they argue that counting draws attention to the humans caught up in these conflicts. Not everyone is convinced that counting casualties is enough to contest the dehumanising logic that renders the civilian population so disposable.Footnote 22 Lauren Wilcox argues that enumerating these casualties is crucial to the critique of late modern warfare, but warns that ‘enumeration of deaths does not … necessarily challenge the production of certain bodies as killable’.Footnote 23 Jessica Hyndman warns that these counts might end up reproducing the same dehumanising logic they are meant to contest, transforming ‘unnamed dead people into abstract figures’.Footnote 24 More recently, Jessica Auchter argues that we need to pay much closer attention to the meanings assigned to dead bodies, warning that not all bodies are equally grievable.Footnote 25 Although we might think that every death matters and that high enough numbers will be sufficient to generate change, she suggests that this is not necessarily the case.Footnote 26

Even among those who believe that the corpses need to be counted, there are disagreements about who is responsible for conducting these counts and how these counts ought to be conducted.Footnote 27 Taylor Seybolt, Jay Aronson and Baruch Fischhoff argue that it is important to know how many people die in violent conflicts, but acknowledge that ‘it can be extraordinarily difficult … to gather accurate information about the number and identity of the people who are killed.’Footnote 28 In addition to the political pressure to inflate or deflate the data, Seybolt et al. note that investigators might not have access to the scene, that they might struggle to locate all the bodies (especially if they are in parts), and might not be able to determine who was responsible for inflicting this harm. There are disagreements about whether investigators should adopt an incident-based approach that examines specific cases or attempt to estimate excess morality within a given area (the problem with incident-based approaches is they are likely to undercount casualties, the problem with estimates is that they are likely to overcount casualties).Footnote 29 Moreover, there is disagreement about whether investigators should prioritise combat-related casualties or expand their counts to include indirect deaths, those who died because they were unable to source sufficient food or access appropriate medical care as a consequence of the conflict. Seybolt et al. suggest that some of these disagreements could be resolved with clearer methodological guidelines, while Keith Krause warns that these guidelines might be part of the problem because they claim to provide simple technical fixes to what are intensely political problems.Footnote 30

I am also interested in the politics of counting casualties, but I want to focus on why the coalition started counting casualties and what was done with the data.Footnote 31 Existing studies have underscored the importance of counting casualties and they outline how these counts ought to be conducted, but they have not examined the relationship between the process of counting casualties and what is being counted. There is an assumption that there are dead bodies out there waiting to be counted and that these counts can, providing they are completed correctly, provide an objective account of the violence inflicted upon the civilian population. Although these studies accept that most counts are incomplete and that counting is often insufficient on its own, they suggest that it is still possible (at least in theory) to create a comprehensive account of the civilian death toll. Diane Nelson challenges the idea that numbers are descriptive and that counting casualties can provide us with an objective account of the harm inflicted during periods of conflict.Footnote 32 Instead, she argues that numbers should be viewed as an engine rather than a camera because they are often part and parcel of the same world-making projects they are supposed to describe. Nelson argues that counting fosters an image of the world as quantifiable, while helping to construct the categories used to administer the social world.Footnote 33 As she explains,

Numbers traverse and transect all terrains of life. They offer powerful tools of generalisation and equivalence, but they are also deployed in particular instances, through situated and singular practices, and create complex relations between one and many, past and future … Mathematics is inseparable from politics.Footnote 34

While my argument owes an obvious debt to Diane Nelson, the work of Sally Engle Merry and Arjun Appadurai has been particularly influential. In her book The Seductions of Quantification, Merry explained why quantification is so appealing, noting that it offers concrete, numerical information about a range of complex political problems, which allows for easy comparison, evaluation, and assessment.Footnote 35 She argued that quantification also ‘organises and simplifies knowledge, facilitating decision making in the absence of more detailed, contextual information’.Footnote 36 While she was well aware of its appeal, she also warned about the problems with quantification, focusing particular attention on its ‘aura of objectivity’.Footnote 37 Despite claiming to provide impartial information, which has not been contaminated by the messiness of politics, Merry argued that the promise of objectivity ignores the enormous interpretative work that goes into producing these figures and the political considerations that shape both the collection and presentation of data. As she explained, ‘the process of translating the buzzing confusion of social life into neat categories that can be tabulated risks distorting the complexity of social phenomenon [because …] counting things requires making them comparable, which means that they are inevitably stripped of their context, history, and meaning.’Footnote 38 At the same time, she challenged the idea that numbers stood apart from the world they claimed to represent, outlining the extent to which statistical information had become entangled with policy formation and governance. As Merry explained,

Statistical knowledge is often viewed as nonpolitical by its creators and users. It flies under the radar of social and political analysis as a form of power. Yet how such numerical assessments are created, produced, cast into the world, and used has significant implications for the way the world is understood and governed.Footnote 39

Appadurai explores similar themes in his work on the relationship between counting and colonialism, which outlines how the demands of enumeration helped constitute the classes that were being counted while reinforcing an ‘illusion of bureaucratic control’.Footnote 40 Appadurai focuses on the various censuses and surveys conducted in India during the nineteenth century as the colonial authorities sought to quantify everything from crop production to caste. These counts were important, he argues, because they did not simply capture some pre-existing reality, but helped change how the colonised saw themselves and engaged with the world around them.Footnote 41 Appadurai notes that ‘colonial classifications had the effect of redirecting important indigenous practices in new directions, by putting different weights and values on existing conceptions of group-identity, bodily distinctions, and agrarian productivity.’Footnote 42 Rather than simply counting existing crops and castes, the census and surveys helped determine which crops would be produced and what communities would be recognised, while flattening idiosyncrasies within these communities and creating boundaries between them.Footnote 43 At the same time, he argues that this data was crucial to both the administration of the colonies and the idea that the colonies could be administered. On the one hand, these figures were used to set agrarian taxes, resolve land disputes, and assess demands for greater political representation. On the other hand, these figures helped reinforce the illusion of a controllable indigenous reality, ‘translating the colonial experience into terms graspable within the metropolis’.Footnote 44 Crucially, the numbers did not describe some pre-existing indigenous reality, but were complicit in both the creation and administration of the colonies.

The politics of counting

This section will explain how the broad arguments outlined in the previous section can be used to investigate coalition civilian casualty counts. Although Merry and Appadurai do not discuss civilian casualties in any detail, their work is well-suited to the task at hand because it draws attention to how counting is often complicit in the problem that is being counted. These numbers do not stand outside the events they are supposed to describe, simply cataloguing, classifying, and chronicling incidents as they unfold. Instead, their work draws attention to what could be described as the politics of counting: the decisions made about what gets counted and how these counts will be conducted, the way in which these counts work to establish certain problems as problems, and how these counts are entangled with the administration of both people and place. In this section, I want to outline the specific ways in which coalition counts were complicit in the violence inflicted in Afghanistan. Firstly, I will explain how coalition counts were entangled with broader efforts to reframe civilian casualties as a strategic problem that could jeopardise the success of military operations rather than an entirely humanitarian consideration, which is governed by certain moral and legal codes. Secondly, I will explain how coalition counts were used to help manage the problem of civilian harm, providing coalition commanders with the tools needed to respond to allegations. Finally, I will outline how the coalition tried to use this data to calibrate the violence used to achieve certain objectives, with the intention of making this violence more effective and more efficient. In doing so, I will argue that the quantification of civilian harm helped to reinforce the illusion that violence is controllable, and that conflict can be rendered more humane.Footnote 45

The principle of non-combatant immunity is meant to protect civilians from intentional attacks, but several scholars have drawn attention to conflicts where militaries have deliberately killed civilians in direct violation of this norm. In his book Targeting Civilians in War, Alexander B. Downes examines the relationship between military necessity and non-combatant immunity, suggesting that the former often prevails over the latter in conflicts where the situation is desperate, militaries are unwilling to sacrifice their own troops, or territorial consequent is involved.Footnote 46 The tensions between military necessity and non-combatant immunity were certainly evident during the initial stages of Operation Enduring Freedom, with Nicholas Wheeler noting that coalition forces ‘were sufficiently cognisant of the necessity to destroy the Taliban and al-Qaeda that they applied a very permissive interpretation of what counted as a legitimate military target’.Footnote 47 As the conflict progressed, however, there was a strange confluence of military necessity and non-combatant immunity, with coalition officials insisting that protecting civilians was crucial to winning the war. In 2008, General McKiernan issued a tactical directive that outlined the strategic importance of protecting civilians, in which he argued that the ‘support of the Afghan people for the GIRoA [Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan] and their collective support for ISAF are critical to defeating the insurgency we are fighting’.Footnote 48 General David Petraeus reiterated this in his tactical directive, stating that the coalition ‘must continue – indeed, redouble – our efforts to reduce the loss of innocent civilian life to an absolute minimum [because] every Afghan civilian death diminishes our cause’.Footnote 49

Specific restrictions were imposed to reduce civilian casualties. General McKiernan introduced rules to reduce the number of civilians killed in escalation of force engagements at coalition checkpoints and he prohibited attacks on residential buildings except when there was a clear and identified threat emanating from the compound.Footnote 50 Rationalising these new rules, he argued that ‘we are engaged in a counterinsurgency in an extremely demanding environment [so …] we must clearly apply and demonstrate proportionality, requisite restraint, and the utmost discrimination in our application of firepower.’Footnote 51 Likewise, General Petraeus insisted that commanders must determine that no civilians are present before using lethal force, unless there was a direct threat to coalition troops.Footnote 52 He argued that ‘protecting the Afghan people does require killing, capturing, or turning the insurgents’, but insisted that coalition troops ‘must fight with great discipline and tactical patience’.Footnote 53 It is important to note that the desire to reduce civilian casualties was driven by strategic concerns rather than humanitarian ones, with coalition commanders viewing civilian protection as a means to a distinctly martial end. There are several reasons for this, which will be elaborated below. On the one hand, civilian casualties were damaging relations between ISAF and the GIRoA, with President Hamid Karzai threatening to place restrictions on what coalition troops were permitted to do. These restrictions would have made it increasingly difficult, and in some cases almost impossible, for commanders to kill or capture high-value targets.Footnote 54 As one internal assessment warned, ‘CIVCAS [civilian casualty] concerns have led to increasing limitations upon … freedom of action.’Footnote 55

It is also important to acknowledge the influence of the Counterinsurgency Field Manual, which was updated and reissued in 2006. The manual argues that success in a counterinsurgency depended less on eliminating insurgents in kinetic operations, and more on securing the support of the local population through a mixture of military and non-military actions. It suggests that the local population can be divided into three distinct groups: those who support the insurgency, those who are neutral or passive, and those who support the counterinsurgents.Footnote 56 Offensive operations remain integral to the campaign, but the manual advises that other initiatives, such as rebuilding schools, repairing roads, and restoring local institutions might be more effective in the long run. At the same time, the manual warns that harming civilians and damaging their property can be counterproductive because it endangers the relationship between the counterinsurgent and the local population, potentially driving them into the arms of insurgents. I will return to this issue in later sections, but it is important to note that counterinsurgency doctrine views civilian casualties as a strategic problem rather than just a moral or legal concern. As Sarah Sewall argued in her introduction to the manual. ‘killing the civilian is no longer just collateral damage [because …] civilian casualties tangibly undermine the counterinsurgent's goals.’Footnote 57 The violence inflicted in the fight against insurgents has to be carefully calibrated to ensure that it is not counterproductive, that it does not end up alienating the local population and jeopardising their support for the counterinsurgent. As the manual makes clear, ‘combat operations must therefore be executed with an appropriate level of restraint to minimise or avoid injuring innocent people.’Footnote 58

Central to my argument is that coalition counts helped to constitute civilian casualties as a problem that could be managed in accordance with the dictates of counterinsurgency doctrine and the exigencies of the conflict that was unfolding in Afghanistan. I am not suggesting that coalition counts were solely responsible for these changes. As we shall see in the following section, coalition officials started counting civilian casualties because civilian casualties were already causing them problems. Nevertheless, these counts helped reinforce a particular way of seeing civilian harm – as a strategic obstacle that could be eliminated or overcome providing that commanders were able to see what was causing this harm and make the necessary tactical adjustments. These counts helped maintain the illusion that the destructiveness of war can be contained and civilians protected from its harms providing that enough data could be amassed and put to good use. As Nikolas Rose explains, ‘to count a problem is to define it and make it amenable to government; to govern a problem requires that it be counted.’Footnote 59 At the same time, the specific processes and procedures that were introduced to count civilian casualties had a significant bearing on what civilian casualties were counted, how these counts were conducted, and how these counts were represented. These procedures instilled specific definitions of the civilian, established certain evidential thresholds, and privileged specific ways of seeing civilian harm, with coalition officials preferring tables and charts rather than more relational accounts of the pain and suffering experienced by those caught in the crossfire.Footnote 60

The remainder of this article will outline how coalition counts were complicit in the violence they were counting, but there are two specific areas that need to be developed in more detail before we proceed. The first concerns how numbers were involved in what coalition officials referred to as ‘consequence management’.Footnote 61 According to the Afghanistan Civilian Casualty Prevention Handbook, which was produced by the Center for Army Lessons Learned and distributed to coalition partners, effective consequence management is critical to mission success because it can help temper the animosity that might be caused by civilian casualties. It notes that past experience has shown that ‘soldiers who were ineffective in addressing civilian harm … can turn a village against international forces, put troops at risk of retaliation, and cause strategic fallout at the national and international levels.’Footnote 62 However, it suggests that effective consequence management can ‘minimise further negative effects caused by potentially mishandling the unfortunate incident, and … can even improve relationships between soldiers and the local population’.Footnote 63 It recommends that units develop a civilian casualty battle drill, which began with soldiers seeking to ‘determine the ground truth of what happened, including the numbers and severity of CIVCAS’.Footnote 64 It also encourages commanders to communicate their findings with locals ‘to maintain credibility, pre-empt rumours, and minimise the enemy's possible exploitation of a reported incident’. At the same time, it emphasises the importance of balancing accuracy with speed, warning that communicating false information ‘can injure trust and create suspicions of cover-ups’.Footnote 65

What is significant about coalition counts is that this data was not only used to manage the consequences of civilian harm, but also used to calibrate the violence used to achieve certain objectives. This article will outline how the coalition sought to weaponise the counting of casualties, bringing them into ‘an arrangement of things [that …] comes to make events of death and dismemberment’.Footnote 66 I am not suggesting that numbers in a spreadsheet are capable of causing physical harm, but I do want to draw attention to the ways in which this data was used to calibrate coalition violence. The term ‘calibrate' is being used very deliberately here. As noted in the introduction, the term is used to describe processes involved adjusting instruments to meet certain standards, ensuring that any irregularities are removed or kept within acceptable levels. This term has a distinctly martial history because the term calibre is used to describe the diameter of bullets, cannonballs, and other projectiles, as well as the internal diameter or bore of the weapon responsible for firing them. Nisha Shah discusses the calibration of lethal force in her work on rifles, which traces how the ethics of lethal force is implicated in specific technical standards. There were certain technical demands that needed to be fulfilled: soldiers required guns that could fire accurately over sizeable distances, inflicting sufficient damage to their target to render them hors de combat.Footnote 67 At the same time, she argues that military necessity cannot explain the preference for certain bullets, warning that ‘arguments about efficiency fail to illuminate the full spectrum of forces that establish certain means of attacking, injuring and killing in warfare as more appropriate than others.’Footnote 68

Instead, she shows that how these technical specifications were also adjusted in accordance with moral qualms about the damage these bullets could inflict to human bodies, with military surgeons complaining these bullets were inhumane because they were causing unnecessary suffering or superfluous injuries to their victims. Shah describes the heated debates that took place at the Hague Conference of 1899 about the harm used by expanding bullets, which flatten on impact with soft tissue. Several delegates sought to ban these bullets because their wounds were considered to be unnecessarily cruel, while the British argued – unsuccessfully – that their wounding impact was no more severe than existing ammunition.Footnote 69 Other bullets were abandoned because they failed to inflict sufficient damage to the tissue as they passed through the body, which meant that soldiers could be patched up and redeployed without much delay.Footnote 70 The technical specifications of the rifle bullets that now dominate the battlefield reflect these competing demands. On the one hand, they have been carefully calibrated to ensure they inflict enough harm to incapacitate the target, sometimes permanently. On the other hand, these bullets have been adjusted to ensure they do not transgress moral and legal prescriptions about what qualifies as a legitimate wartime injury. As Shah explains,

As these technical specifications coalesce and became standardised, the rifle began to imprint a distinctive calibre of deadly force: a socially acceptable standard not of the number of dead but how its different components and their consequences – barrels, bullets and ballistic power – produced an instrument of war in which lethality was forged and functioned as an indelible part of warfare.Footnote 71

Her arguments about calibrating rifle bullets has been enormously influential on my argument, but there are some important differences between her work and mine. While Shah is interested in the wounding impact of different bullets to make a broader point about how war has been rendered ‘humane’, I am concerned about how the coalition sought to calibrate the wounding impact of counterinsurgency operations in Afghanistan. Counting civilian casualties enabled the coalition to gauge the force needed to achieve their objectives without causing unnecessary harm to civilians. Commanders relied on this data to ensure they were using enough violence to kill their targets, but not too much that they caused unnecessary harm to civilians, which could undermine their tactical successes. Whereas counting civilian casualties is normally viewed in terms of obfuscating or illuminating the harm inflicted in warzones, this article examines how counting civilian casualties was used to enable and enhanced the violence inflicted on the battlefield as part of coalition attempts to maximise its efficiency. It is for this reason that I have italicised the term unnecessary civilian casualties because there were times when the coalition determined that civilian casualties were a necessary risk.Footnote 72 As the Afghanistan Civilian Casualty Prevention Handbook explained, ‘deliberate offensive engagements against high-value individuals may be approved despite the anticipated likelihood of CIVCAS because of the military importance of the target’.Footnote 73 In the same way that rifle bullets have been calibrated to ensure that lethal force can be wielded ‘humanely’, this article will show how civilian casualty data was used to calibrate coalition attacks to ensure that commanders could continue targeting insurgents without suffering ‘strategic setbacks’.Footnote 74

Damage control

The previous section outlined the broad theoretical arguments that inform my analysis, drawing attention to how the enumeration of violence is often entangled within the violence that is being enumerated. Rather than simply documenting the dead, I am suggesting that coalition counts were complicit in the creation of corpses as this data was used to calibrate the violence that was inflicted in the fight against insurgents and to help manage the strategic consequences of civilian harm. Coalition forces were required to reduce civilian casualties and counting these casualties became an important part of this endeavour, but it is important to recognise that these measures were really about protecting Afghan civilians, but maximising military efficiency. The data was something that could be used to gauge the forced needed to achieve certain objectives to ensure commanders has sufficient firepower to overpower their adversary without jeopardising mission success. Framing civilian casualties as a strategic problem obviously incentivises commanders to reduce the harm inflicted on non-combatants, but one might wonder what happens to civilians when protecting them is no longer considered to be as strategically important. I will return to this in the conclusion because this section will focus on what prompted the coalition to start counting civilian casualties and how coalition officials sought to use these figures to manage the consequences of civilian harm.

The coalition started counting casualties more carefully in the aftermath of an airstrike in the village of Azizabad, which took place on 22 August 2008.Footnote 75 Coalition forces were in pursuit of a high-value target named Mullah Siddiq, but came under fire when they entered the village, so an AC-130 gunship was dispatched to provide support. Over two hours, the gunship expended 82 howitzer rounds, 242 bullets, and a 500lb bomb, which was dropped on a residential building where enemy combatants were thought to be hiding.Footnote 76 The mission was initially heralded as a success. Coalition officials reported that thirty militants were killed in the attack – including the intended target – and a sizeable arsenal of weapons was recovered from the scene, without a single civilian casualty. Coalition officials revised their statement a few hours later, admitting that five civilians were among the casualties.Footnote 77 These figures were disputed by the Ministry of Interior Affairs, which reported that 76 civilians were killed.Footnote 78 During a separate investigation, UNAMA discovered ‘convincing evidence … that some 90 civilians were killed, including 60 children’.Footnote 79 Nevertheless, coalition officials maintained a thorough assessment had been conducted and that only five civilians – two women and three children – had been killed during the attack. Moreover, a spokesperson claimed that ‘we believe those to be family members of the targeted militant, Mullah Siddiq.’Footnote 80

Their account was called into question once again when mobile phone footage emerged showing approximately thirty corpses sprawled out at the village morgue, including the bodies of 11 children.Footnote 81 Despite their initial denials, officials eventually acknowledged that their figures were wrong (although they continued to dispute other counts). General McKiernan agreed to investigate the attack and a declassified summary concluded that 33 civilians were killed during the operation but claimed that other figures remain ‘unsubstantiated’.Footnote 82 The report argues that the list provided by the Afghan government was ‘invalid due to investigative shortfalls’, while other counts are described as being overly reliant on ‘inconsistent villager statements’ and lacking what it describes as a ‘multi-disciplined intelligence architecture’.Footnote 83 Investigators also discovered that the intended target escaped unharmed but this was not mentioned in the declassified summary.Footnote 84 Even with this omission, the episode was hugely embarrassing for the coalition. General McKiernan had personally dismissed allegations of civilian harm, claiming that the death toll was ‘nowhere near the number reported in the media’ and accusing journalists of falling victim to a ‘very deliberate information operation orchestrated by the insurgency’.Footnote 85 Now officials had to concede that ‘we were wrong on the number of civilian casualties.’Footnote 86

General McKiernan instructed officials to investigate the problem and these investigations uncovered a range of issues. Most significant was the lack of an appropriate institutional apparatus for collating data about civilian casualties, comparing the various reports and disseminating the findings in a timely and accurate manner.Footnote 87 Units complained that there was no obvious point of contact in the chain of command for them to report instances or allegations of civilian harm, which meant that officials at ISAF HQ often lacked up-to-date information about civilian casualties.Footnote 88 As a consequence, officials might be providing incorrect information to the media based on preliminary reports from the unit responsible, which should have been revised with the latest figures.Footnote 89 Human rights groups also complained about the absence of clear lines of communication with coalition officials, which made it unnecessarily difficult for them to report allegations of civilian harm or receive comments about incidents that were already in the public domain.Footnote 90 General McKiernan recognised that this was not only a problem for human rights groups but also coalition officials because it prevented them from shutting down rumours that they considered to be inaccurate and pre-empting reports that were still under investigation. Reflecting on these problems, General McKiernan argued that the coalition was becoming ‘totally reactionary’.Footnote 91 Allegations were circulating, and officials needed to comment, but they were reliant upon incomplete and inaccurate information. As General McKiernan explains, ‘we didn't always end up responding and at that point we were, we were behind.’Footnote 92

Azizabad was a particularly embarrassing moment for the coalition, but civilian casualties were already creating tensions with the Afghan government, with Afghan officials threatening to place restrictions on coalition operations. The coalition attempted to address some of these concerns with Fragmentary Order 221, which was issued a month before the attack on Azizabad. The new directive stated that coalition troops must report all allegations of civilian harm – irrespective of the source – so that commanders could assess whether an incident needed investigating.Footnote 93 Units were now required to submit a first impressions report within two hours together with a second impressions report eight hours later (providing additional details about the operation, the number of civilians killed, and whether local officials had been informed). The unit then had another 72 hours to recommend whether the incident should be investigated because civilians were killed, or potential misconduct had occurred.Footnote 94 Despite tightening reporting procedures, coalition officials still struggled to get accurate information from the units involved, which meant that their initial statements often contained errors or inaccuracies that would have to be corrected in subsequent releases.Footnote 95 Azizabad was a particularly egregious example of this, with officials having to issue several clarifications as more evidence emerged.Footnote 96 These inconsistencies were not just embarrassing for the coalition, but were aggravating tensions with the Afghan government, who believed that the coalition were dismissing credible reports without conducting an appropriate investigation.Footnote 97

General McKiernan established the Civilian Casualty Tracking Cell (CCTC) to rectify these shortcomings. The tracking cell began as a two-person team, which was comprised of non-military personnel and located inside the Combined Joint Operations Center in Kabul.Footnote 98 It was responsible for collating data on civilian casualties in a single spreadsheet, which could be consulted whenever allegations emerged.Footnote 99 The database contained basic information about coalition operations, including the time and date of attacks, the type of operations that were being conducted and the units involved, and whether anyone – combatant or non-combatant – was killed. The purpose of documenting these deaths was not entirely benign. The coalition was not interested in enhancing transparency or accountability but ensuring that officials could contest allegations they considered unfounded or to explain cases where civilians had been killed. According to Larry Lewis, who co-authored the Joint Civilian Casualty Study, the CCTC was initially launched as public relations exercise, designed to help manage ‘reputational risk’.Footnote 100 Coalition officials were ‘getting so many allegations that [they …] wanted to contest but you cannot contest these allegations if you don't know what is happening on the ground’.Footnote 101 This was echoed by Lieutenant General Frank Kearney, who argued that ‘every civilian casualty situation that we couldn't explain … begins to erode your authority and your freedom of action.’Footnote 102 The harm inflicted upon civilians was no longer just a humanitarian concern for the coalition, it was starting to have a detrimental effect on military operations and needed to be minimised and managed more effectively.

The importance of counting civilian casualties to managing reputational risk was echoed by Major General Gordon ‘Skip’ Davis, who was Chief of the Strategic Advisory Group. He argues that coalition officials were being asked to comment on allegations within incomplete or inaccurate information only to discover that no coalition troops were in the area.Footnote 103 Unable to deny that civilians had been killed without confirming the facts, the coalition would announce some form of investigation but these investigations could take weeks to complete, while the initial allegation continued to circulate without challenge.Footnote 104 When coalition officials were finally in a position to contest these claims, the rumour would be so well established that coalition denials appeared like ‘we were withholding things’.Footnote 105 Creating the CCTC helped to alleviate the problem because officials could simply cross-reference allegations with entries in their database, which detailed who was operating in the area, whether they had discharged their weapons and whether any civilians had been killed. The CCTC ‘would know the grid locations of where ordnance was dropped, so if there was a report of a bomb or an explosion or rocket fire from an airborne platform, we could confirm what unit was nearby’.Footnote 106 Cases that did not appear in the database could simply be dismissed as erroneous but additional information could also be requested if weapons were discharged and no civilian casualties were recorded or there was uncertainty about the identity of those who had been killed.Footnote 107 Put simply, the database was supposed to assist coalition officials manage the problem of civilian harm more effectively, providing them with tools that could be used to placate Afghan anger and distress.

Some parallels could be drawn here with the literature on lawfare, which traces how the law has been used to realise certain military objectives.Footnote 108 The term was popularised by Major General Charles Dunlap, who was concerned that opponents of the United States were using international humanitarian law to impede or discredit lawful military operations. Unable to overpower American troops on the battlefield, Dunlap argued that its adversaries were intent on destroying its will to fight, misusing the law to create the impression that United States operations were indiscriminate, disproportionate, and inhumane.Footnote 109 Since then, the term has been reappropriated to explain how the law can be invoked to legitimise operations, with critics arguing that powerful states are using the law to rationalise the harm inflicted upon civilians.Footnote 110 As noted in the introduction, Rumsfeld was particularly concerned about the appearance of propriety during Operation Enduring Freedom, telling reporters that ‘no nation in human history has done more to avoid civilian casualties than the United States has in this conflict’.Footnote 111 Although Rumsfeld acknowledged that some civilians had died as a consequence of American airstrikes, he claimed that the Taliban were ‘hiding in mosques and using Afghan civilians as human shields by placing their armour and artillery in close proximity to civilian schools, hospitals and the like’.Footnote 112 Responding to allegations that American operations were unlawful, Rumsfeld argued that ‘responsibility for every single casualty in this war, be they innocent Afghans or innocent Americans, rests at the feet of the Taliban’.Footnote 113

The lawfare literature is useful because it highlights how international humanitarian law is both indeterminate and ‘productive of military violence’.Footnote 114 There was clearly a pressure on commanders to ensure that coalition operations appeared lawful and civilian casualties made things more complicated, especially when officials were unclear how many civilians were killed in a particular attack or had to go back and correct previous statements in response to new evidence. At the same time, it is important to note that there is something specific about the measures introduced during this period that is not captured in the literature on lawfare. Coalition officials believed that it was no longer enough to simply demonstrate that operations were lawful, they needed to demonstrate a commitment to civilian protection beyond the normal legal requirements. In his tactical directive, General McKiernan argued that the support of the Afghan people was critical in the fight against insurgents, but warned that civilian casualties could jeopardise this support.Footnote 115 Simply affirming the legality of coalition attacks – that civilians were not targeted intentionally, that the unintended harm to civilians was proportionate to the anticipated military gains, and that precautions were taken during the attacks – was unlikely to convince bereaved relatives and wounded civilians that the coalition cared about their security. Instead, General McKiernan argued that coalition troops must ‘clearly apply and demonstrate proportionality, requisite restraint, and the utmost discrimination in our application of firepower’.Footnote 116 This meant minimising the need to use deadly force in the first place and avoiding attacks on civilian infrastructure, but it also entailed responding appropriately when civilians were harmed.Footnote 117

This section has examined what prompted the coalition to start counting civilian casualties, focusing on the specific problems following the airstrike in Azizabad. I have argued that the decision to start counting civilian casualties was animated by military necessity rather than humanitarian considerations, with coalition officials fearing that civilian casualties were having a detrimental impact on both their ability to conduct operations against insurgents and the effectiveness of these operations. It was becoming increasingly difficult for the coalition to dispute allegations without having immediate access to accurate figures, while rejecting credible allegations prematurely was extremely damaging for its reputation. Establishing the CCTC enabled the coalition to amass the information it needed to respond to any allegations that emerged, equipping commanders with the facts and figures they needed to dispute allegations they considered to be untrue, clarify allegations they considered to be partially accurate, and to explain cases where civilians were injured or killed. In the following sections, I will explain how the coalition sought to use this data to calibrate the violence inflicted rather than simply responding to incidents that had already occurred. As the CCTC began to amass more data about what was causing these casualties, coalition officials were able to make adjustments to tactics, techniques, and procedures with the explicit aim of reducing civilian harm – not because they were concerned about the pain and suffering inflicted upon the civilian population, per se, but because they were concerned about the damage it was doing to the success of military operations.

Mitigating the harm

General McKiernan was sacked not long after the CCTC was established, but his successor continued to count civilian casualties. Upon his arrival in Afghanistan, General Stanley McChrystal issued a new tactical directive, which emphasised the operational importance of reducing civilian casualties. It stated that coalition forces should continue to fight insurgents using all the tools at their disposal but warned that the coalition ‘will not win based on the number of Taliban we kill’.Footnote 118 Instead, the directive argued that gaining and maintaining the support of the local population should be the ‘overriding operational imperative and the ultimate objective of every action we take’.Footnote 119 It warned that civilian casualties were becoming an impediment to mission success and urged troops to ‘avoid the trap of winning tactical victories – but suffering strategic defeats – by causing civilian casualties or excessive damage and thus alienating the people’.Footnote 120 General McChrystal placed additional restrictions on the use of lethal force, including close-air support. When operating in residential areas, he argued that ‘commanders must weigh the gain of using [close-air support] against the cost of civilian casualties, which in the long run makes mission success more difficult and turn the Afghan people against us’.Footnote 121 He also received regular briefings about civilian casualty trends, exclaiming during one meeting that ‘we are going to lose this fucking war if we don't stop killing civilians.’Footnote 122

Coalition officials started counting civilian casualties because they wanted to be able to respond quickly and accurately to allegations of civilian harm, but the data was also useful when it came to calculating the violence needed to achieve certain military objectives. This is particularly important in the context of counterinsurgency operations, which depend upon the support of the local population. An entire section of the Counterinsurgency Field Manual is dedicated to what it describes as ‘us[ing] the appropriate level of force’.Footnote 123 It acknowledges that there are times when an ‘overwhelming effort’ is needed to defeat or intimidate the enemy, but warns that ‘an operation that kills five insurgents is counterproductive if collateral damage leads to the recruitment of fifty more insurgents.’Footnote 124 Unlike more conventional conflicts, in which spectacular displays of force might be needed to establish rapid dominance, the manual argues that ‘it is vital for commanders to adopt appropriate and measured levels of force and apply that force precisely so that it accomplishes the mission without causing unnecessary loss of life.’Footnote 125 It also emphasises the importance of constant measurement and assessment, outlining a range of indicators that should be tracked to measure progress.Footnote 126 These indicators include obvious things, such as the level of insurgent violence, as well as things like economic activity, attendance at religious ceremonies and participation in local elections. The manual is strangely ambivalent about counting casualties, noting that it can be difficult to establish the identities of the dead and determine ‘which side the local populace blames for collateral damage’.Footnote 127 Nevertheless, civilian casualty data became increasingly important as the coalition tried to ‘calibrate how killing in war occurs’.Footnote 128

CCTC was particularly valuable to the coalition because it not only enabled officials to respond to specific incidents, but also allowed them to monitor long-term trends. General McChrystal created the Counterinsurgency Advisory and Assistance Team (CAAT) to identify the causes of these casualties and Radha Iyengar, an economist based at the London School of Economics, was appointed to help make sense of these figures.Footnote 129 Shortly into her secondment, Iyengar was summoned to the situation room at ISAF HQ to deliver a presentation on the strategic impact of civilian casualties.Footnote 130 On average, she found that civilian casualties caused by coalition forces led to an increase in attacks on coalition forces that persisted for fourteen weeks after the civilians were killed.Footnote 131 Subsequent research confirmed this correlation, finding that if one coalition-caused civilian casualty incident (involving at least two civilian casualties) was eliminated, there would be six fewer insurgent attacks on coalition positions over the following six weeks.Footnote 132 These findings were significant because they seemed to confirm the idea behind ‘insurgent math’, which suggests that ‘for every innocent person you kill, you create 10 new enemies.’Footnote 133 In doing so, these figures not only documented the violence that was inflicted upon the Afghan people but shaped coalition attitudes towards civilian harm, reinforcing the idea that killing civilians was undermining the success of military operations. As Merry explains, these ‘indicators do not stand outside regimes of power and governance but exist within them, both in their creation and ongoing functioning’.Footnote 134

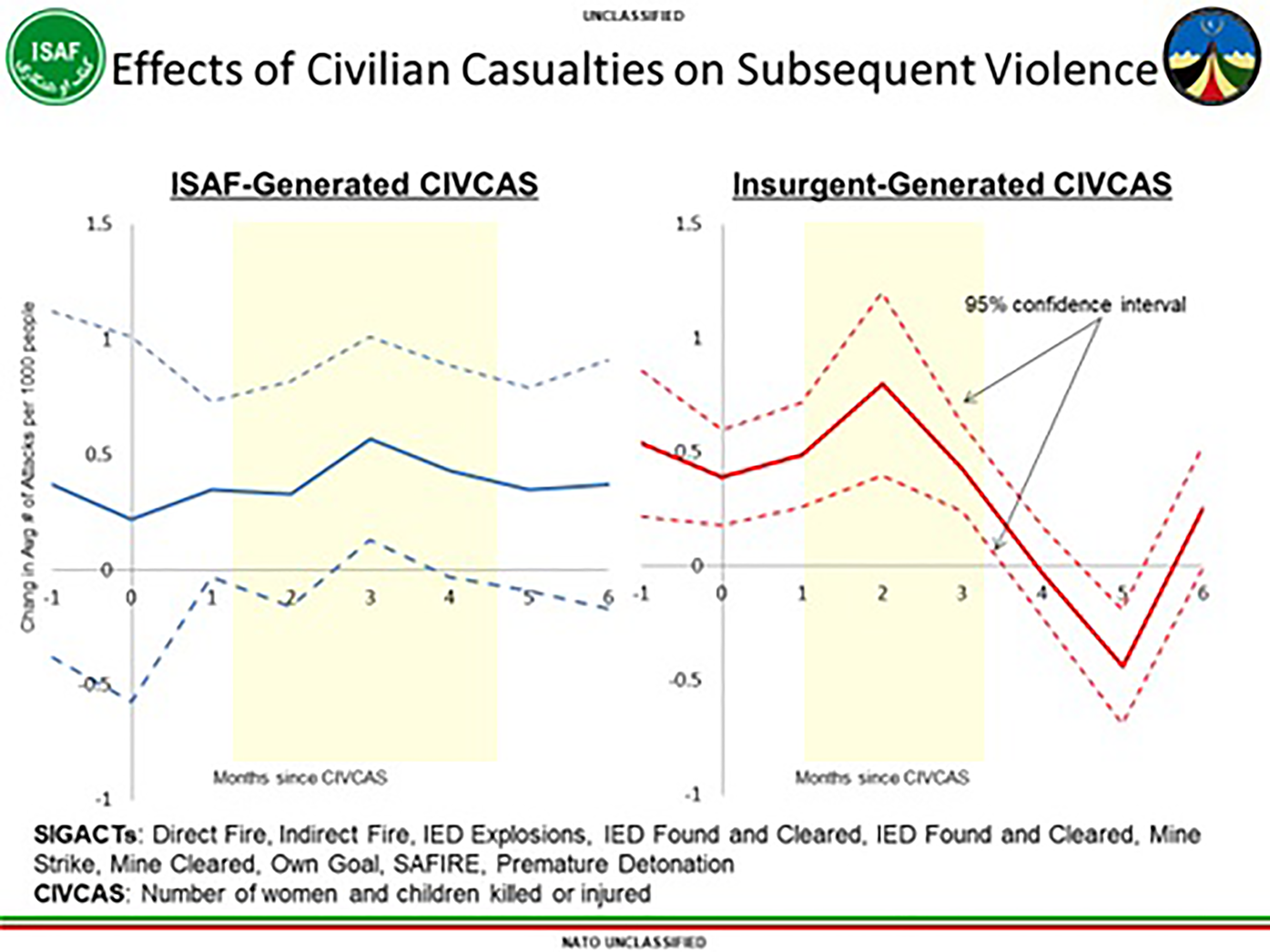

The performative power of these numbers is reflected in both the changes made to the rules of engagement as a consequence of this analysis and the way these numbers were invoked to justify these changes to coalition troops, who were obviously concerned about the additional risks.Footnote 135 General McChrystal introduced the notion of ‘courageous restraint’ to encourage soldiers to consider the ‘delicate balance between strategic intent and tactical necessity’.Footnote 136 The idea was that troops would refrain from using lethal force in situations where civilians might be killed unless it was absolutely necessary. Not surprisingly, there was some pushback against these rules, with troops complaining that they were being forced to fight with ‘one hand tied behind their back’.Footnote 137 Coalition officials were able to use CCTC data to contest these claims, producing various graphs to demonstrate that killing civilians increased the risk to coalition troops. Figure 1, for example, outlines the effects of civilian casualties on subsequent violence, indicating that there is an increase in violent activity in the months following an ISAF-generate civilian casualty incident. It shows that the effect can vary from a 25 to 65 per cent increase in kinetic activity, with an average of 35 per cent over five months.Footnote 138 The second graph shows that insurgent-generated civilian casualties also lead to an uptick in violent activity, but the impact was less significant.Footnote 139

Figure 1. Slide from CAAT PowerPoint briefing (2010).

This graph is interesting for several reasons, not least because it reveals how coalition officials categorised the dead. International humanitarian law is notoriously vague on the distinction between combatants and non-combatants, defining civilians as ‘any person who does not belong to the armed forces’.Footnote 140 The definition has proven problematic during the conflict in Afghanistan, where insurgents relied on their ability to blend in with the civilian population (for the most part, they did not wear a uniform, they did not carry their weapons openly and they did not identify themselves as combatants). The absence of obvious markers meant that coalition troops had to look for other ways to identify the enemy, with gender being used to shore up this distinction.Footnote 141 Christiane Wilke and Khalid Mohd Naseemi argue that these gendered assumptions were not only operationalised to target certain individuals but also when the casualties were being counted.Footnote 142 Buried in the small print, we see how coalition officials categorised the victims, defining civilian casualties as ‘the number of women and children killed or injured’ (see Figure 1). The data released by coalition forces works to solidify a particular understanding of the civilian, which actively excludes ‘military-age males’ from this category, transforming them into killable subjects.Footnote 143 As Merry reminds us, these numerical indicators ‘camouflage the political considerations that shape the collection and presentation of data’.Footnote 144

At the same time, the graph points to the way in which this data was used to reinforce a specific understanding of the conflict. CAAT officials were dispatched to bases around Afghanistan to reinforce messages about the strategic impact of civilian casualties, reminding troops that ‘the goal of reducing civilian casualties is not necessarily in conflict with the objective of protecting the lives of international forces’.Footnote 145 Figure 2 comes from a PowerPoint presentation delivered by Colonel Joseph Felter, in which he urges troops to ‘accept tactical risk [to …] avoid strategic failure’.Footnote 146 Colonel Felter draws on the data to explain the rationale behind insurgent maths, claiming that minus one civilian can lead to plus twenty insurgents – causing civilian casualties, he argues, is ‘how we lose’.Footnote 147 Subsequent slides outline the strategic consequences of civilian casualties. He cites an example from Nangahar where an improvised explosive device (IED) – planted by insurgents – killed two Afghan children, alongside several Afghan soldiers. Although insurgents were responsible for this attack, Colonel Felter argues that ‘they were able to start a whisper campaign that the US forces were throwing grenades at Afghan children’.Footnote 148 These rumours made things much more difficult for coalition troops, triggering protests against their continued presence and a ‘decreased willingness … to share information’. As a consequence, coalition data indicates there was a much lower clearance rate for IEDs in the months that followed.Footnote 149

Figure 2. Slide from CAAT PowerPoint briefing (2010).

His presentation also outlined the strategic benefits of not killing civilians, explaining how tactical patience can actually make troops safer in the long run. Colonel Felter cites an example from Helmand, where people were protesting allegations that coalition troops were defacing the Qur'an. As the protests escalated, frustrated locals began throwing rocks at coalition troops. Rather than opening fire on protestors, he argues that troops ‘stood fast – not a single Marine fired their weapon, even after suffering concussions and other injuries’, claiming that their ‘courageous restraint prevented a bad situation becoming much worse’.Footnote 150 Colonel Felter argues their restraint actually improved relations with the local community, noting that this unit enjoyed one of the highest ratios of found-to-exploded IEDs across the entire country, due – in no small part – to tips received from the local community.Footnote 151 Here we can see how the coalition used civilian casualty data to convince soldiers about the importance of courageous restraint, highlighting the strategic benefits of not killing civilians and the strategic consequences of inflicting civilian harm. Crucially, these examples highlight how the data became increasingly entangled in the violence it was supposed to represent. Rather than simply documenting civilian deaths, these figures were used as a tool to manage the violence inflicted on the Afghan people. At the same time, the coalition were starting to run into problems with the accuracy of the information that was being collected, so new procedures were needed to help standardise the data the coalition was collecting. In the following section, I will outline some of the changes that were introduced to improve the data, and how these improvements enabled the coalition to conduct more complex assessments of the violence used to achieve certain objectives.

Standardising the data

The more detailed analysis undertaken by coalition officials was only possible due to vast improvements in both the quantity and the quality of data collected. General McKiernan required troops to report allegations of civilian harm within two hours of a report being received, but concerns were raised about the accuracy of this information, with Bob Dreyfuss and Nick Turse describing it as ‘woefully incomplete’.Footnote 152 These concerns were shared by Larry Lewis, who argued that some commanders investigated every incident while others only conducted investigations when they thought there ‘could be neglect or actual criminality’.Footnote 153 Put simply, there were no clear criteria about what needed to be reported and what should be included in these reports.Footnote 154 In order to rectify these problems, General McChrystal introduced Standard Operating Procedure 307, arguing that ‘deliberate management and active quality control by the chain of command [is needed …] to ensure that all available facts are presented and that analysis and assessment is conducted with discipline and rigor.’Footnote 155 Under the new procedures, units had to submit a first impressions report at the ‘conclusion of any tactical engagement where a CIVCAS incident is known or suspected to have occurred’ and another four hours to produce a more detailed storyboard of events. A second impressions report had to be submitted within four hours of the unit returning to base, but this could be extended to a maximum of 24 hours if they were still out on assignment.Footnote 156

The unit was then expected to submit a final Investigation Recommendation Report within 24 hours, providing an outline of the recommendation to COMISAF about whether the incident should be formally investigated. Even in cases where no further action is recommended, the unit responsible is required to submit a CIVCAS Assessment Report within nine days, ‘reviewing the facts, post incident response and effectiveness, and lessons identified with recommendations for implementation’.Footnote 157 Standard Operating Procedure 307 also introduced a separate process for assessing the credibility of any claims, stipulating that a Joint Incident Assessment Team be established within 24 hours. These teams were assembled to assess specific allegations and their membership varied depending on the incident, but they were normally composed of operational experts, military lawyers, and medical personnel.Footnote 158 Officials tried to ensure that at least one woman was present because it was ‘very helpful if you were going to talk to women and kids’.Footnote 159 These teams were not authorised to investigate the incident, merely assess the credibility of any reports. However, these assessment teams were permitted to interview the troops involved, review coalition footage, and collect forensic evidence from the scene.Footnote 160 They were also encouraged to interview local witnesses, but this was not always the case, with victims often complaining that they were not consulted.Footnote 161

These assessments were beneficial to coalition officials as they could be completed much quicker than formal investigations because the emphasis was on establishing the facts rather than identifying misconduct.Footnote 162 The assessment teams were expected to file a first impressions report with 72 hours to ensure that coalition officials had accurate details about the number of casualties and the circumstances surrounding their deaths.Footnote 163 Colonel Hans Bush recalls one incident where an assessment team arrived so soon after the first reports were received that the firefight was still going when they touched down.Footnote 164 In this case, rumours were circulating that coalition troops had killed an important village elder but the assessment team were able to track the man down – alive and well – and send footage back to Kabul. General Petraeus, who was now in command, was able to walk over to the presidential palace to show footage of the man to President Hamid Karzai on his iPad.Footnote 165 The information provided by these assessment teams was particularly useful when it came to mitigating the negative impact of civilian casualties on the success of counterinsurgency operations. In cases where the allegations were considered to be false, coalition officials could use the eyewitness testimony and forensic evidence to dispute the claims being made.Footnote 166 In cases where the allegations were found to be true, coalition officials could provide detailed information about how these casualties occurred, what steps were taken to avoid killing civilians, and what would be done to make amends for this harm.Footnote 167

The deluge of data now flowing into coalition spreadsheets meant that officials could not only respond more accurately to allegations of civilian harm but to conduct more detailed analyses of what was causing this harm. When General John Allen took command of coalition forces, he expanded the Civilian Casualty Tracking Cell (CCTC) into the Civilian Casualty Mitigation Team (CCMT), which was headed by a colonel and staffed by a mixture of military and nonmilitary personnel.Footnote 168 Tracking civilian casualties remained an integral part of its mandate but the CCMT was also responsible for providing guidance on how civilian casualties could be mitigated or avoided. Drawing on the data its predecessor had collected, the CCMT coordinated subject-specific studies on particular operations or weapons to determine what was causing civilian casualties and whether anything could be done to address these problems.Footnote 169 The coalition established a CIVCAS Mitigation Working Group, which met on a bi-monthly basis to review specific engagements and discuss lessons learned. The CIVCAS Mitigation Working Group would make recommendations to the CIVCAS Avoidance and Mitigation Board, which was chaired by the deputy commander of coalition forces.Footnote 170 These recommendations could lead to the introduction of new guidelines or fragmentary orders, as well as adjustments to existing tactics, techniques, and procedures. The CCMT would be responsible to monitoring the impact of these adjustments and whether units were complying with new directives.Footnote 171

Coalition officials also held a series of conferences on the issue of civilian harm to encourage what General Petraeus described as ‘a candid exchange of views and ideas as we work through the tragic consequences of armed conflict’.Footnote 172 Brigadier Paul Harkness, who organised the conference, extended invitations to various Afghan groups, arguing that ‘we need to consciously see the issue through Afghan eyes, we need to ensure our dialogue is continuous.’Footnote 173 Participants discussed specific incidents and events but coalition officials also used it as an opportunity to emphasise that the number of civilians killed and injured by coalition troops had decreased by more than 20 per cent despite a significant increase in troop levels. A second conference was organised to discuss coalition airstrikes, with participants invited to discuss everything from the rules of engagement through to the ordnance that was being used. Opening the conference, Lieutenant General Adrian Bradshaw argued that the elimination of civilian casualties was no longer just a moral imperative but an ‘operational necessity to ensure ISAF operational freedom of action’.Footnote 174 Attention shifted to those killed by the enemy at the third civilian casualty conference, with Lieutenant General Bradshaw noting that insurgents were responsible for 93 per cent of the civilians killed and injured in the four months leading up to the event. Coalition data indicated improvised explosive devices were responsible for the vast majority, so killing those responsible for making these devices was an ‘absolutely vital part of reducing civilian casualties’.Footnote 175

So far, this article has traced how coalition counts have evolved from a relatively crude instrument primarily concerned with reputational risk into a much more sophisticated apparatus focused on managing the violence inflicted upon the people of Afghanistan. Detailed guidelines were introduced to ensure that troops were not only counting civilian casualties but providing specific information about how these civilians were killed, which officials used to produce subject-specific studies on both the causes and consequences of this harm. More importantly, these figures were used to shape the conduct of coalition troops, helping to convince frontline soldiers that tactical patience could enhance mission effectiveness and make them safer. Once again, this article has shown that coalition body counts were entangled with the violence they were supposed to represent. The figures assembled in coalition spreadsheets were never an impartial register of dead and injured bodies but an instrument that could be deployed by the coalition in the fight against insurgents. In the following section, I will outline how the coalition used these figures to calibrate the violence used to achieve certain objectives. Building on the work of Appadurai, I will argue that coalition civilian casualty data helped to reinforce the illusion of bureaucratic control, which suggested that the conflict was winnable providing that coalition forces were more judicious in their application of lethal force.

Calibrating the violence

This is certainly not the first time that body counts have been weaponised by the military. During the war in Vietnam, for example, body counts were an important measure of success, with officials relying on enemy attrition rate to compensate for the growing irrelevance of other indicators, such as territorial control.Footnote 176 These counts were never simply about documenting the dead but encouraging troops to be more ferocious in the field.Footnote 177 Pressure to produce high body counts flowed down the chain of command, with officers establishing ‘production quotas’ to ensure that units were killing in sufficient quantities.Footnote 178 Units that surpassed their targets were rewarded with rest and relaxation passes, lighter duties around base and additional food at mealtimes. Those who missed their targets were kept out on patrol or punished with hot and dangerous hikes through treacherous terrain instead of the usual helicopter ride home.Footnote 179 Commanders even erected chalkboards – or ‘kill boards’ – in canteens across the country so troops could see how they performed against other units operating in the same area, ‘lending death totals the air of sports statistics’.Footnote 180 Rather than merely recording casualties, these counts actively encouraged soldiers to kill by honouring those with the highest scores and humiliating soldiers who underperformed.

These counts were contentious because they created a powerful incentive for units to inflate their figures, either by lying about the number of people they had killed or deliberately misclassifying innocent civilians as enemy combatants.Footnote 181 One particularly egregious example is Operation Speedy Express, which sought to disrupt enemy supply lines in the Mekong Delta. The military initially claimed that 10,899 enemy combatants were killed during the operation but admitted that only 748 weapons were recovered.Footnote 182 An article in Newsweek argued the ‘staggering number’ was suspicious, observing that ‘the operation yielded an embarrassingly small number of enemy weapons’.Footnote 183 Officials claimed that insurgents were shot ‘before they could get to their weapons’ and that ‘many individuals in … guerrilla units were not equipped with individual firearms’ but locals insisted that the vast majority were farmers who were ‘gunned down while they worked in their rice fields’.Footnote 184 A subsequent investigation estimated that between 5,000 and 7,000 civilians were killed during the operation and that their bodies had been miscategorised as combatants.Footnote 185 Although this was a particularly shocking example, it certainly was not an aberration. As one Pentagon investigation found, ‘padded claims kept everyone happy: there were no penalties for overstating enemy losses but an understatement could lead to sharp questions as to why [American] casualties were so high’.Footnote 186

Things were very different in Afghanistan, where coalition officials were more interested in tracking civilian harm rather than dead combatants. These counts were also used to influence the behaviour of troops but they were meant to encourage a more judicious application of force rather than incentivise unnecessary killings. General McChrystal outlined the rationale for this in his tactical directive, where he urged troops to abandon ‘more traditional measures, like capture of terrain or attrition of enemy forces’. The directive called for a more ‘carefully controlled and disciplined employment of force’, acknowledging that this entails greater risks for coalition troops but warning that ‘excessive use of force resulting in an alienated population will produce far greater risks’.Footnote 187 General Petraeus reiterated this in his tactical directive.Footnote 188 Coalition troops were required to pursue the Taliban with tenacity, killing or capturing them when necessary, but they were also encouraged to fight with ‘great discipline and tactical patience’.Footnote 189 General Petraeus also argued that coalition troops had to ‘hunt the enemy aggressively but use only the firepower needed to win a fight’.Footnote 190 In other words, lethal force needed to be carefully calibrated to ensure that the coalition could continue to kill those it wanted to kill without causing unnecessary harm to civilians, and jeopardising the success of the mission.