1. Previous scholarship

The ruins of the Tangut city of Khara-khoto became known to modern scholarship following excavations conducted by the Russian expedition led by Pyotr K. Kozlov (1863–1935), who visited the site in 1908 and again, a few months later, in 1909. Since then, several other expeditions have excavated the ruins, including those led by M. Aurel Stein (1862–1943) and Sven Hedin (1865–1952).Footnote 1 In 1983 and 1984, the Inner Mongolian Institute of Archaeology carried out two rounds of systematic, large-scale excavations. Among the results of the project was that the team successfully reconstructed the boundaries of the city that had stood there during the Yuan period. In addition, they found about 3,000 fragments of handwritten and printed texts, the bulk of which were administrative documents in Chinese and Tangut. A small group of texts was in Mongolian, and a few additional items were in Old Uyghur, Tibetan, Arabic, Old Turkic and Syriac.Footnote 2 The earliest date featuring on the Chinese fragments was 1295 and the latest, 1371.Footnote 3

The Mongolian fragments were studied by Yoshida Jun'ichi and Chimeddorji, who published their research as a book in 2008.Footnote 4 In this, grouped in the category of “religious texts”, are fragments of a woodblock-printed book written in the Uyghur script. The editors classify the fragments as religious because interlinear Chinese characters mention a master called Perfected Sun (Sun zhenren 孫真人) and refer to the jiao 醮 ritual, pointing to a Daoist background.Footnote 5 The editors provide a full transcription of the text and translate it into both Japanese and Chinese. They also add notes, explaining unusual vocabulary and the transliterated form of Chinese words. In their concluding notes, they express their opinion that the Mongolian text must have been a translation of a Chinese original, which was most likely a Daoist work or a literary composition focusing on Daoism. As to the identity of Perfected Sun, they suggest that it may refer to the well-known physician Sun Simiao 孫思邈 (581–682), author of medical works such as the Qianjin yaofang 千金要方 (Essential Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Pieces of Gold) and Qianjin yifang 千金翼方 (Supplementary Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Pieces of Gold). Yoshida and Chimeddorji's book is also valuable because it includes photographs of the excavated items, giving ready access to the originals.

Photographs of the two printed folios are also included in a facsimile volume of the non-Chinese material excavated from Khara-khoto, published in 2013 by Tianjin Ancient Books Press 天津古籍出版社. Here the two sides of the same folios appear side by side, offering a convenient way of examining the text and illustrations.Footnote 6 An improvement to the arrangement of the fragments in this volume is that the organizers are able to identify the original location of a number of smaller pieces of one of the two folios, reconstructing additional details not visible before. Thus, on one side we can now see a standing man with a horse, and on the other, a small building. Unfortunately, the order of the pages themselves is still not correct, as it follows the sequence in which Yoshida and Chimeddorji presented the text.

In a study of Daoist texts from Khara-khoto, Chen Guang'en 陳廣恩 draws attention to several fragments, highlighting their significance in providing evidence for the spread of Daoism in northwestern China, and particularly in the Ejina 額濟納 (Ejin Banner, Inner Mongolia) region.Footnote 7 He argues that even though the fragmentary condition of the folios does not allow us to determine with certainty the nature of the text, it is possible that the Chinese original was neither a Daoist scripture nor a literary text, but rather a ritual manual used by Daoist devotees in their daily life, giving instructions related to prayers or the jiao ritual. In considering the identity of Perfected Sun, Chen contends that there are several possible candidates in addition to Sun Simiao, especially if the text was indeed a ritual manual.

In a paper devoted specifically to these Khara-khoto fragments, Otgon Borjigin provides an insightful analysis of the Mongolian text and makes a series of important observations.Footnote 8 Basing his argument on palaeographic and linguistic grounds, Borjigin maintains that its date must be close in time to the commentary of the Bodhicaryāvatāra from 1312 found in Turfan. Relying on the Chinese and Mongolian pagination that appears on the margins, he puts the pages in the right order, rearranging them from how they were initially catalogued. In addition to reading the text in the correct sequence, Borjigin also interprets the illustrations, which allows him to reconstruct the overall narrative. His reading of the text is thus fuller and provides crucial details not available in earlier translations. Regarding the interlinear Chinese characters, he proposes that they may have been added at a later time as an aid to readers.

2. Description of the fragments

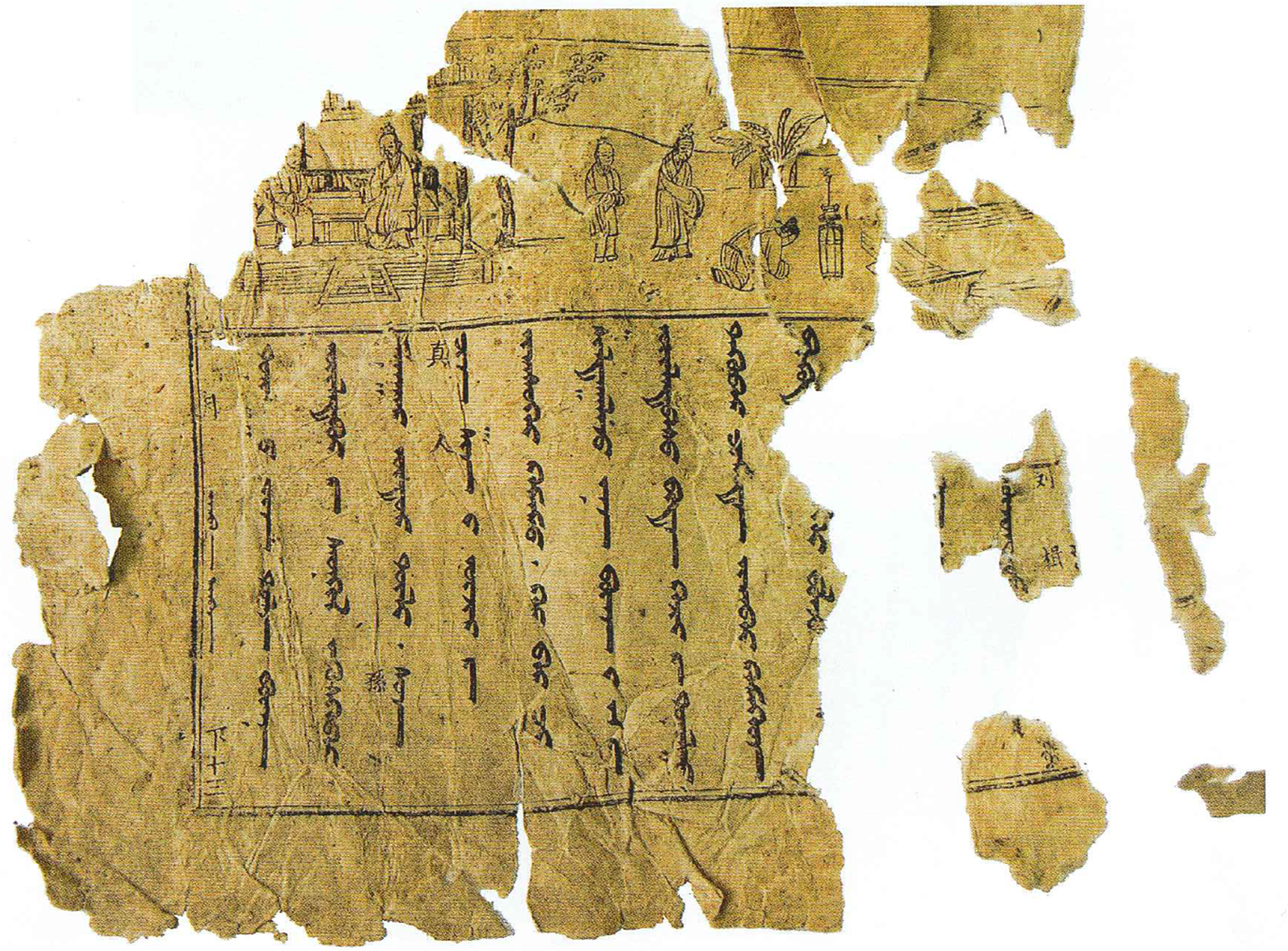

The fragments discussed in this article originally come from two folios (i.e. four pages) of a woodblock-printed book. Fortunately, there are page numbers in both Chinese and Mongolian, signifying the correct order of the pages (i.e. 13A, 13B, 14A, 14B).Footnote 9 In each case (Figure 1), the page numbers are preceded by the Chinese character yue 月 (“moon”), indicating the number of the volume. Such Chinese characters are known in some Mongolian printed texts where they signify the number and sequence of volumes in longer books. According to György Kara, Chinese characters on the margins sometimes appear in Mongolian books from Chinese printing shops, and may represent the sequence from a well-known set of characters, such as the Five Elements, the Ten Stems or the initial words of the Qianziwen 千字文 (Thousand Character Text).Footnote 10 Interestingly, the Turfan booklet with the commentary to the Bodhicaryāvatāra mentioned above also has similar Chinese pagination starting with the character yue 月 (i.e. 156A一百五十六上, 156B一百五十六下, etc.). Erich Haenisch, who studied this blockprint in detail, wrote that the character referred to the fourth item in the four-character sequence “heaven and earth, the sun and the moon” (tiandi riyue 天地日月).Footnote 11 Whether in this case the character yue 月 similarly marks the fourth item or it comes from another sequence, such as the Qianziwen, it demonstrates that the Khara-khoto fragments were originally part of a multi-volume set.Footnote 12

Figure 1. Page 13B of the book, showing the illustration above the text, the format of pagination as well as the interlinear Chinese characters. Source: Yoshida and Chimedodoruji (Reference Yoshida and Chimedodoruji2008: 4).

The pages have wide margins, and the text and illustrations are enclosed within a frame that consists of a thick outer and a thin inner line. The illustrations are separated from the text by the same double frame, with a thin line on the top and a thick one on the bottom. The folios have text and illustrations on both sides, showing that this was not a double-layered thread-bound book common in Song printing but a pothi-style volume, with relatively thick leaves. One of the peculiarities of the folios is that they contain illustrations, with the images on the top occupying slightly more than a third of the framed area. Although this article does not aim to analyse the images, we cannot but note that the image on the top and text at the bottom (shangtu xiawen 上圖下文) format had already made its debut among the Dunhuang manuscripts from at least the tenth century, and became extremely popular in later print culture.Footnote 13 Examples of it are also known from Khara-khoto in Chinese and Tangut.Footnote 14 The Tangut books in this format, as well as our two Mongolian folios, are translations from Chinese and collectively constitute evidence for the circulation of such prints in this period.

An important feature of the text is the presence of several interlinear Chinese characters, placed to the left of the Mongolian lines. These are instrumental in identifying the original text, as they drastically narrow down the range of possibilities, which are unavoidable when trying to reconstruct Chinese names and terms on the basis of a phonetic script. The fragments include the following Chinese characters, which invariably appear to the left of their Mongolian transliterations:

• Sun zhenren 孫真人 (Mongolian: sun čin s̠in). This is a reference to a Daoist master by the surname Sun. Because of the fragmentary nature of the folios, sometimes the name is truncated and appears as zhenren 真人 (“Perfected One; perfected person”) or ren 人 (“person”).

• Liu Ji 劉楫 (Mongolian: liu si). This is the name of the protagonist in the text, occurring twice in its full form and once as Ji 楫 only.

• Yiyang 宜陽 (Mongolian: i yang). In the text, this is the native city of Liu Ji, mentioned only once in the text.

• Jiao 醮 (Mongolian: sau). This is the Daoist ritual jiao, or purgation, which appears a single time in the surviving portion of the text.

The interlinear Chinese characters immediately allow us to make several interesting observations. One of these is that in all cases they are Chinese proper nouns or terms which feature in the Mongolian text in transliterated form. The Chinese characters not only disambiguate these entities, making clear what they refer to with greater precision, but also mark them as foreign lexical items, alerting the reader to the need to treat them as such. This latter function is useful even if the reader does not read Chinese, as it signals that the potentially unfamiliar string is a phonetic rendering of a Chinese lexical item. Another thing that is apparent from the fragments is that the Chinese characters appear not only at first occurrence of the name or term but accompany their Mongolian transliteration consistently. Therefore, whenever the word čin s̠in appears in the Mongolian text, the Chinese characters zhenren 真人 are also there on the side. Similarly, the name Liu Ji (or Ji) occurs four times, and in each case we find the Chinese characters on the side, almost as if they were part of the way of writing the name in Mongolian. As far as it is possible to tell from the photographs, the Chinese characters are not written by hand but are printed together with the Mongolian text, even if they appear to the left of the Mongolian lines. In other words, they could not have been glosses or notes added by a later reader but formed part of the printed edition from the beginning. This, in turn, means that they were part of how the text was intended to be presented in Mongolian.

Such auxiliary use of Chinese characters in non-Chinese texts is a fascinating phenomenon. In the preclassical Mongolian translation of the Xiaojing 孝經 (Classic of Filial Piety), the Chinese text is broken up into smaller segments which, within the same line, are then followed by the corresponding Mongolian translation.Footnote 15 In this manner, the book is a bilingual edition in which the two languages alternate, following each other in small segments. But the two partial folios from Khara-khoto are somewhat different in that the text is entirely in Mongolian, and the Chinese characters are written not on the same line as the main text but to the left of the line, next to the corresponding Mongolian segment. Moreover, they are given only for names and terms that appear in transliterated form and do not therefore form meaningful lexical items in Mongolian.

Such synergy between languages and scripts is far from obvious. We do not see it, for example, in Tangut translations excavated from Khara-khoto. Even if a Tangut text is translated from a Chinese original, there are no Chinese characters to help the reader to interpret or process proper nouns and technical terms. Apart from lexicographic works, Tangut is typically the only language the reader encounters on the page. Instead, the Tangut translators may use other devices to tag foreign names and terms. For example, in the Tangut version of the Sunzi bingfa 孫子兵法 (Art of War of Sunzi), they often provide additional information in order to contextualize proper nouns. Thus, what appears in the original simply as Qin 秦 is translated as “the state of Qin”; Ye 業 as “the city of Ye”; Taizong 太宗 as “Tang Taizong”.Footnote 16 To some extent, such devices are also used in the Mongolian text of the two folios; for example, Yiyang is rendered as i yang qoton (“the city of Yiyang”), expressly tagging the syllables i yang as the name of a city. The interlinear Chinese characters, however, provide a technical mark-up mechanism that is independent of the translation. In a sense, adding Chinese characters on the side is similar to our modern practice of writing foreign names and terms with the Latin script but also including them in the original script (e.g. Greek, Chinese, Japanese). By doing this, we accomplish three things: 1) mark them graphically as independent units distinct from the surrounding text, 2) disambiguate them semantically, and 3) draw attention to them as items of significance.

3. Tracing the sources of the story

Despite the fragmentary nature of the folios, enough of the Mongolian text is present to gain a general picture of the overall narrative. The illustrations offer some details as well. As the Mongolian text has been transcribed and translated in previous scholarship,Footnote 17 here I simply summarize the narrative insofar as it can be reconstructed from the fragments. The text describes how a Chinese official called Liu Ji deliberates with his wife on how to redeem the souls of those who died in battle. He finds a Daoist priest (i.e. Perfected One) to initiate the project. Then the Daoist priest has a dream in which the deceased souls complain to him that they still have not been redeemed because no meritorious deeds have been performed on their behalf. They say that a rich man called Liu Ji, a native of Yiyang, would like to perform such deeds to have them released from hell and he will come to see him at noon the next day. If he does not perform meritorious deeds, they will not be able to attain redemption. Eventually, the jiao ritual is performed and then food and alms are distributed to the poor for three days. These actions result in favourable weather conditions and an abundant harvest that year.

Even though the basic outline of the narrative is coherent, the text is incomplete, which makes the identification of the Chinese original difficult. Naturally, the starting point for such an endeavour is to focus on the identity of the protagonist Liu Ji 劉楫, who appears in the text as a native of Yiyang. There are several historical figures by this name, including a Yuan-dynasty official (fl. 1309), whose courtesy name was Jichuan 濟川.Footnote 18 More relevant, however, is a Liu Ji mentioned in an inscription on a stele from 1577, erected at the Shangqing Temple 上清宮 in Luoyang. The inscription is called “Record of the Origin of the Yellow Registers Ritual” 黃籙緣起儀文記, and it traces the origin of the Yellow Register and the associated jiao ritual to the end of the Eastern Han period. Liu Ji enters the story only as the next step in this long line of transmission:Footnote 19

漢晉隋唐,教法逐興,至唐時間,有劉楫者,遊香山寺,回,道遇相士曰:“汝壽不長矣。” 楫行途見群鬼曰:“我等世崇李密戰殺之魂,丐求超托。” 楫遂謁上清宫孫真人,建齋,超魂托趣。真人夢天門大開,天真曰:“賜楫壽延三紀。”真人曰其言後,楫□天津橋復遇相者,曰:“翁所陰德出現,壽延三紀。”後果如言。楫以才德位列品官,生子五人,壽考善終。

During the Han, Jin, Sui, and Tang periods, the teachings gradually started to flourish. In the Tang period, there was a certain Liu Ji, who traveled to the Xiangshan Temple, and on his way back, he met a fortune-teller who said to him: “You will not live long!” Along the way, Liu Ju also met a group of ghosts who said: “We were the followers of Li Mi and are the souls of those who were killed in battle, we beg you to redeem us!” Thereupon Liu Ji visited Perfected Sun at the Shangqing Temple, who set up the ritual space to redeem the souls. Perfected Sun had a dream that the gates of heaven opened up and a heavenly perfect said: “Liu Ji has been granted three twelve-year cycles as an extension of his lifespan.” After the Perfected One has spoken (i.e. telling Liu about his dream), Liu Ji was [later] crossing the Heavenly Ford Bridge and once again met the fortune-teller, who told him: “Because of your hidden virtue, your life has been extended by three twelve-year cycles.”Footnote 20 And later it indeed turned out as he had predicted. Because of his talent and merits, Liu Ji became a ranked official; he fathered five sons, enjoyed a long life and died in peace.

The point of Liu Ji's story in the inscription is to explain that he served as an inspiration for present-day believers to make the Yellow Register, motivating the entire village to offer contributions to the project. The story itself roughly follows the trajectory of what we see in the Mongolian text, including the plea made by the souls of those killed in battle, Liu Ji's visit to Perfected Sun's place, the jiao ritual, as well as the master's dream. There are details, however, that are absent from the Mongolian version, including the time when the events happened (i.e. the Tang dynasty), the names of the Xiangshan and Shangqing temples, the two meetings with the fortune-teller, the prediction of a short life, the prolongation of his lifespan as well as his successful career and happy personal life. The fragmentary nature of the Mongolian folios makes it impossible to tell whether these details are missing due to damage or if they were never part of the source text. At the same time, it is also clear that the Mongolian version contains details that are absent from the inscription, notably that Liu Ji lived in Yiyang, that he consulted with his wife, that food and alms were given to beggars for three days and that the weather was favourable that year, resulting in an abundant harvest. These do not feature in the Luoyang inscription because there Liu Ji's story merely provides the background for the villagers’ inspiration to contribute towards the costs of the ritual and it is not the main topic.

The names of the Xiangshan and Shangqing temples and the Heavenly Ford Bridge all point to Luoyang as the place where these things happened. The stele inscription's mention of the ghosts of the dead having been the followers of Li Mi 李密 (582–619) also points to Luoyang, as this is where the general fought the Sui 隋 forces in a battle that resulted in massive casualties. In fact, the stele was erected at the Shangqing Temple with which, according to the story, Perfected Sun was associated. This temple had been established in 662 following Emperor Gaozong's 高宗 (r. 649–683) edict, at the site of an existing shrine to Laozi 老子祠, in order to provide “defence against ghosts” 以鎮鬼. Once the construction works were completed, “the emperor ordered the performance of the jiao ritual” 帝令設醮.Footnote 21 In later centuries, the temple's fortunes varied greatly and by the beginning of the sixteenth century it was completely abandoned, and the steles were being reused as building material.Footnote 22 As part of the Jiajing 嘉靖 Emperor's (r. 1521–1567) commitment to supporting Daoism, the temple was rebuilt in 1550, and the 1577 stele was no doubt connected to this renewed appreciation of the temple and its history.Footnote 23

Another source mentioning Liu Ji's miracle story is a stele inscription from 1574, located in the Dongzhen Temple 洞真觀 in Tiemen Town 鐵門鎮 near Luoyang. This inscription dates from only three years earlier and is situated about 40 km west of the Shangqing Temple, revealing that the two of them were part of the same resurgence of interest in Liu Ji and his ritual. The inscription commemorates the donations local believers gave for the performance of the jiao ritual. The beginning of the inscription traces the Yellow Register expressly to Liu Ji:Footnote 24

黃籙者,乃劉公巨濟之始也,命推夭壽,遂投孫真人,言曰::“廣捨資財,書畫黃籙二堂,建其黃籙延生大醮。”乃巨濟壽增二紀,後得主簿之職。

The Yellow Register began with Master Liu Juji (i.e. Liu Ji). Because he had been foretold that he would die early, he went to see Perfected Sun, who told him to be generous with his wealth and paint two [liturgical paintings for the] Yellow Registers Ritual and establish the Great Jiao Ritual of the Yellow Register for Prolonging Life. As a result, Juji increased his lifespan by two twelve-year cycles and was later able to rise to the post of Assistant Magistrate.

Liu Ji's story here features both as the origin of the Yellow Register and a precedent for the efficacious results of the jiao ritual. The rest of the text, not translated here, explains how he inspired present-day believers to make financial contributions towards the performance of the ritual and the creation of the Yellow Register. This version of the story is even briefer but mentions details not seen in the surviving portion of the Mongolian text, such as the prediction of Liu Ji's dying early, the prolongation of his life by two (instead of three) twelve-year cycles and his becoming an assistant magistrate. In this inscription, the main reason Liu Ji approaches Perfected Sun is to prolong his own lifespan, rather than the more altruistic cause of saving the ghosts of the dead. This, of course, demonstrates that the motivation of local believers for erecting the stele stemmed from a similar desire to live longer and happier lives. This concern, however, does not seem to feature in the Mongolian text, which is about redeeming others. Moreover, the protagonist is called Master Liu Juji, and without the help of the Shangqing Temple inscription it would be difficult to identify him with Liu Ji in the Mongolian inscription. Naturally, the style name Juji is significant from the point of view of the narrative because it literally means “Grand Redemption” and seems to be a reference to the large-scale project of saving the souls of the dead.

4. A printed edition from 1407

The two Luoyang stele inscriptions reference a story that was without doubt well known among Daoist believers of the region during the 1570s. As a result, they retold only the part that was most relevant from the perspective of their own agenda. Fortunately, an earlier and fuller account of the story survives in the Da Ming Renxiao huanghou quanshan shu 大明仁孝皇后勸善書 (Morality Book of Empress Renxiao of the Great Ming Dynasty), a collection compiled by Empress Xu 徐 (1362–1407; i.e. Empress Renxiao 仁孝皇后 or Empress Renxiaowen 仁孝文皇后), consort of the Yongle 永樂 Emperor (r. 1402–24). The book consists of inspiring stories originating from Buddhist, Daoist and Confucian sources, collated together into a single 20-juan 卷 collection. It was printed by the court in 1407, following the death of the empress, and was distributed not only within the Ming Empire but also to neighbouring states such as Korea.Footnote 25 In Japan, the collection gained popularity somewhat later and mainly in an excerpted edition; in the end, it was the translated version of these excerpts (1730) that may have been the most influential.Footnote 26

Although the story of Liu Ji (in juan 14) is just one of a multitude of inspiring narratives in the collection, it is significantly longer and contains more details than the brief references in the two Luoyang inscriptions.Footnote 27 This version properly introduces the protagonist, explaining that his name was Liu Ji, he was a native of Yiyang County 宜陽縣 in the Western Capital 西京 region and lived during the Tang period. His courtesy name was Juji 巨濟 (“Grand Redemption”) and he was 27 years of age at the time of the events retold in the narrative. He was a wealthy man and in the fourth year of the Jiaxiang 嘉祥 era (a reign title that did not exist in Chinese history), he rode his horse to the Xiangshan Temple 香山寺 to burn incense there. As he was coming out of the temple, he met a fortune-teller who told him that even though he had fine clothes and was a wealthy man, he would not live long. To avoid his fate, within 30 days he should cultivate blessings (xiufu 修福). After returning home, Liu Ji deliberated with his wife, who was from the Xu 許 family, trying to work out what he should do. His wife suggested that he should arrange a ritual for the redemption of the ghosts of those who had died in the battle between Wang Shichong 王世充 (567–c. 621) and Li Mi 李密, but had been unable to be liberated. She thought this was especially appropriate because their home was in Gong County 鞏縣, a place full of such souls who also frequently harmed ordinary people. But for this, they needed to enlist a holy man whose spiritual powers would help to save the souls.

Liu Ji thought that he could ask the great master Perfected Sun 孫真人 at the Shangqing Temple 上清宫, and his wife agreed. Accordingly, he travelled there and as he was getting close, he saw from a distance two or three men under a tree, holding a horse. Once he got near, he recognized Perfected Sun, who was wearing purple clothes. The master said that he had been waiting for him for quite a while, greatly surprising Liu Ji who could not imagine how the master knew that he would be coming. The master explained that the day before he had gone to Luoyang and, on his way back, at dusk, he came across hundreds of ghosts who told him that they were the ghosts of those who had perished in battle and had been unable to obtain redemption. They asked him to have Liu Ji perform a purgation ritual for them so that they could finally be liberated. Having finished speaking, the ghosts suddenly disappeared. And this is how the master knew of his coming. The two of them decided on a suitable day for the jiao ritual, and Liu Ji returned home.

On the agreed day, he rode a horse cart to Perfected Sun's place.Footnote 28 On the night of the jiao ritual, a group of cranes came down from the gates of heaven and flew around the altar. That year, the entire region of Luoyang enjoyed balanced weather and there were no disasters. The jiao ritual was extremely efficacious. Later on, Perfected Sun sent a letter to Liu Ji and recounted that he had had a dream in which the ghosts came to thank him, telling him that they had requested heaven to extend Liu Ji's life and that he was allowed three extra twelve-year cycles. The closing lines of the story read as follows:

巨濟後於洛陽天津橋上,見一相者曰:「公作何福?面上有陰德之氣,觀公之貌,壽可延三紀。」劉曰:「別無陰德,止做醮救拔孤魂,設貧三日而已。」相者曰:「救死拔亡,其功甚大!」楫後以才德,任洛陽主簿,及生五子,壽年六十六歲,善終。

Sometime later, on the Ford of Heaven Bridge in Luoyang, Juji (i.e. Liu Ji) once again met the fortune-teller, who said: “What blessings have you performed? Your face has the aura of hidden virtue. Judging by the way you look, your lifespan has been extended by three twelve-year cycles.” Liu Ji replied: “I have no hidden virtue; I just set up a jiao ritual to redeem the orphaned souls and distributed alms to the poor for three days, and that is all.” The fortune-teller said: “The merit gained from redeeming the dead is great!” Because of his talent and merits, Liu Ji later assumed the post of Assistant Magistrate of Luoyang; he had five sons, lived to the age of sixty-six and died in peace.

This version in Empress Renxiao's compilation has a series of concrete details and names, which set up the historical background. According to this version, Liu Ji was from Yiyang County in the Western Capital and lived during the Tang period. The reign title Jiaxiang seems to be a mistake because no reign with that name is known from Chinese history.Footnote 29 We also learn that he was visiting the Xiangshan Temple, which is in the southern part of Luoyang. His wife's surname is Xu 許, which seems to play no role in the story, other than perhaps making it sound more specific and thereby more authentic. His home was in Gong County, east of Luoyang, not far from the site of the Battle of Yanshi 偃師之戰, fought in 618 between the armies of Wang Shichong and Li Mi. The story expressly mentions this historical event and uses it as the premise for the plot. The mention of Wang Shichong's 王世充 name makes it likely that the awkward phrase shichong 世崇Footnote 30 in the Shangqing Temple inscription derives from Wang's personal name Shichong 世充, and that this bit became corrupted in the inscription. We also learn that Perfected Sun, whose given name is never mentioned, was based at the Shangqing Temple.

In every respect, this printed version gives a more complete account of the background and the sequence of events in Liu Ji's story than the brief references in the two Luoyang stele inscriptions. The two epigraphic sources contain no additional information that does not feature in this version or contradicts it. It is apparent, however, that although in the Renxiao version Liu Ji's primary motivation is still the desire to extend his own life, the story goes into greater detail about performing the ritual and feeding the hungry. These deeds not only redeem the souls of the dead but also bring blessings that year to the entire Luoyang region. The two stele inscriptions do not go into detail in this regard, assuming that the readership was familiar with what Liu Ji had accomplished.Footnote 31

Indeed, the Mongolian text is remarkably similar to the Renxiao version. Both are shorter pieces of narrative literature, comparable to many other stories in Empress Renxiao's collection. This raises the possibility that the Mongolian version was also part of a similar collection, a hypothesis corroborated by the physical dimensions of the book. In particular, the Chinese-Mongolian page numbers show that the surviving portion of the text was on folios 13–14 in a multi-volume book. Because the two versions are so similar, it is also probable that, despite the discrepancies, they belonged to the same genre. This, in turn, points towards the whole pothi book having been of a similar nature. In other words, the Mongolian book may not have been a Daoist work per se, but rather an eclectic collection of stories from a variety of sources, including Buddhist and Daoist ones. Knowing the sequence of events from the Chinese version, we can calculate that Liu Ji's story took up four or five full pages, and if the stories in the book were on average of similar length, the previous 12 folios (i.e. folios 1–12, amounting to 24 pages) of this volume would have contained five or six more stories. In addition, the Chinese volume number yue 月 demonstrates that there were four or more such volumes, making it a larger collection of stories.

The Mongolian fragments and the Renxiao text match not only in terms of the general narrative but also in many concrete details. Both mention horses, for example, in contrast to the stele inscriptions, which do not. Thus, at the very beginning of the Renxiao text Liu Ji rides a horse to go the Xiangshan Temple, and although we do not see this in the Mongolian text, the reconstructed left side of the first image shows a man standing with a horse.Footnote 32 Then in the Renxiao text Liu Ji rides a horse cart to the ritual, and the corresponding part of the Mongolian folio likewise mentions the horse. Another telling example is the expression shepin 設貧 (translated above as “gave alms to the poor”), a decidedly uncommon phrase in Chinese sources.Footnote 33 The corresponding part in the Mongolian text talks about distributing food and alms to beggars, which is a good match for the meaning of the Chinese phrase.

Despite these similarities, enough of the Mongolian version survives to make it clear that it differs in some respect from the Renxiao version. For example, in the Mongolian text the ghosts mention Liu Ji's name, him being a native of Yiyang and that he had consulted his wife about performing meritorious deeds. By contrast, in the Renxiao version, these details appear earlier in the story and are related by the narrator. Whether they also featured in the now-lost beginning of the Mongolian text, it is certain that the ghosts do not mention such specifics in the Renxiao version. In addition, there is also some imbalance between the two versions in how much space the narrative allocates to particular events. In other words, the Renxiao version is not the text the translator used. On the one hand, this is only to be expected, since it is later than the Mongolian version, which was dated by the archaeologists to the Yuan period. Having said that, we should remember that the dating of this group of fragments from Khara-khoto relies on the handful of dated items, the latest of which comes from 1371. This is merely 36 years earlier than 1407, when the Ming court printed Empress Renxiao's collection and, more importantly, some of the undated fragments from the site could have been of a later date. Just as importantly, even though Empress Renxiao's book was printed in the early fifteenth century, the Preface describes that she collected the stories of the Three Teachings (i.e. Buddhist, Daoist and Confucian) from existing sources, compiling them into a single book. Therefore, Liu Ji's story in her collection was undoubtedly based on an earlier version, which quite possibly predated the Mongolian version.

Although Liu Ji is only identified as living in the Tang period, it is possible to narrow down the time frame of his story. The mention of the Battle of Yanshi (618) as the cause for the presence of large numbers of orphaned souls lingering in the Luoyang area implies that the story itself would have taken place several years after that. The Shangqing Temple, which plays a central role in the story, was established in 662, which means that Liu Ji's visit there would have happened not long after that. Therefore, purely from a chronological perspective, it would be possible that the appellation “Perfected Sun” referred to Sun Simiao (581–682) who lived at that time. Indeed, several printed fragments of his Sun zhenren Qianjin fang 孫真人千金方 (Master Sun's Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Pieces of Gold) have been excavated at various locations in Khara-khoto, showing that he was well-known in the region.Footnote 34 Yet if Liu Ji was a historical person in the Luoyang area, Perfected Sun would have also been someone living in the same region. All in all, the surname and the time frame are not enough evidence for identifying Perfected Sun with Sun Simiao.

Despite the differences, finding a closely related Chinese version of the text also helps to improve our comprehension of the Mongolian fragments. Thus, even though most of the line is torn off, we now understand that the “… appointment which has been made with each other…” (line 6, no. 055) must refer to Liu Ji and Perfected Sun having agreed on an auspicious day for the jiao ritual. Similarly, the small, disconnected fragment HF125c-b contains the word küčündür (“by the strength of”) and, from the adjacent line, the name of Liu Ji in Chinese characters.Footnote 35 Although this fragment is currently entirely without context, based on the Chinese text we can deduce that the word küčündür probably corresponds to the part where Liu Ji and his wife discuss that to ensure the efficacy of the ritual, they would need to rely on the spiritual powers of a holy man. For this reason, it is likely that the fragment does not belong with folio 13 B, as seen in Figure 1, but comes from an earlier part in the narrative.

As a final note, it is worth pointing out that the story of Liu Ji resembles the plot of the much better known account of Liu Hongjing 劉弘敬, recorded in the Taiping guangji 太平廣記 (Extended Records of the Taiping Era), which identifies the Yinde zhuan 陰德傳 (Accounts of Hidden Virtue) as its source. This other Liu is also a wealthy man who meets a fortune-teller and learns that, despite his wealth, he does not have long to live. The fortune-teller advises the traumatized man to perform meritorious deeds in order to cancel out the disasters in his life, and soon Liu has the chance to free a slave girl called Fang Lansun 方蘭蓀. Shortly after that, he has a dream in which the girl's late father comes to thank him for his good deed and to tell him that he appealed to the Thearch on High (shangdi 上帝), who extended his life by 25 years and will also make his descendants prosperous.Footnote 36 In addition, the father relates that their misfortunes are due to political injustice. Sometime later, Liu once again meets the fortune-teller, who confirms that his lifespan has indeed been extended.Footnote 37 It is obvious that the two stories resemble each other in many ways, ranging from the surname of the protagonist to the specific chain of events, and even the character sun 蓀 in the girl's name, which may preserve a link with the surname of Perfected Sun.

5. Conclusions

Previous scholarship suggested that the fragments of the two Mongolian folios examined here contained a translation of a Chinese Daoist work, although there has been little certainty regarding the identity of the source text, or even that of the story itself. This article managed to locate the story of Liu Ji in several Chinese sources, arguing that the Mongolian text was closest to the version included in Empress Renxiao's Quanshan shu. Although this collection was printed by the Ming court in 1407 and thus may post-date the Mongolian text, it consists of stories and tales gathered from earlier sources and it is very likely that the original of Liu Ji's story in it predated the Mongolian translation. The similarities between the Renxiao and Mongolian versions went beyond sharing the same overall plot, as they were also of comparable length and narrative genre. In addition, the pagination of the Mongolian fragments made it clear that the folios had originally been part of a larger book, which may have been analogous to Empress Renxiao's collection, an eclectic compilation that drew on a variety of religious and moralizing sources. If this hypothesis is accurate, then the original book would have been transmitted to Khara-khoto as a heterogeneous collection of inspiring stories, rather than as a text used by Daoist communities.

Other versions of the story survived in two sixteenth-century Ming steles erected at Daoist temples in the Luoyang region. Of the two temples, the Shangqing Temple featured in the story as the very place where Liu Ji commissioned Perfected Sun to perform the jiao ritual in order to redeem the orphaned souls. Thus, not only the events in the plot but even the sources that cited the story had a connection with Luoyang, while it remained comparatively unknown in other parts of China. Although the imperially distributed Renxiao collection would have had wide circulation, Liu Ji's story in particular did not seem to have achieved widespread popularity beyond its cult place. This is yet another reason to think that it reached Khara-khoto as part of a larger collection of miracle stories.

The primary aim of this article was to identify the story in the Mongolian folios and to locate antecedents or parallels in Chinese sources. Although the Renxiao text cannot be seen as an immediate source for the translation, it preserves a version that is relatively close to that used by the translator. There are certainly other fruitful avenues of research connected with the fragments, especially with regards to the illustrations, which could be compared with other known specimens from the Yuan period. These questions, however, lie beyond the scope of this article.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Shih-shan Susan Huang, Nadine Bregler, Otgon Borjigin, Flavia Xi Fang and Daniel Sheridan for their generous advice while writing this article.