It is our aim to show that clinicians should have a high index of suspicion regarding a genetic disorder when meeting someone with a mild learning disability. It is already common practice to carry out chromosomal analysis on patients with obvious dysmorphology. It is less common to carry out tests on people with mild learning disabilities and no associated dysmorphological findings. It has been assumed that the intelligence level of people with mild learning disabilities is merely the lower end of the normal distribution and not associated with pathology (Reference LehrkeLehrke, 1997); that this group of individuals was to be found almost exclusively among the lower social classes; and that their intelligence levels were accounted for by an interplay between the multifactorial genetic and environmental influences that account for intelligence in general. However, evidence is now gathering from a number of sources to question this (Reference Thapar, Gottesman and OwenThapar et al, 1994). Crucially, much work has been done with regard to the role of the X-chromosome in intelligence (Reference TurnerTurner, 1996; Reference LehrkeLehrke, 1997). Its contribution is now regarded as axial. Many different genetic defects involving the X-chromosome have been described (see below), resulting in lowered intelligence. This topic has been explored further by Gecz & Mulley (Reference Gecz and Mulley2000) and Partington et al (Reference Partington, Mowat and Einfeld2000). The incidence of chromosomal abnormalities has consistently been found to be higher in people with mild learning disability than the general population. Gostason et al (Reference Gostason, Wahlstrom and Johannisson1991) found chromosomal aberrations in 19.2% of a sample of 57 people with mild learning disability compared with 1.9% of controls. It may be that many cases of mild disability are not owing to a culmination of polygenic inheritance and environment, but rather because of genetic defects of the X-chromosome which can be small and not necessarily associated with other obvious dysmorphology. These can then be passed from generation to generation. The case study below illustrates some of the issues.

METHOD

Case study

Miss D was born when her mother was 29 years old, following an unsuspected twin pregnancy. She was the firstborn twin and weighed 5lb 2oz. There were no immediate neonatal problems, but it soon became apparent that Miss D's development was falling behind that of her twin sister. She did, however, manage to attend mainstream school until the age of 9 years, when she transferred to a school for children with mild learning disabilities. Her IQ was tested in 1993 using subsets of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Revised (WAIS-R; Reference WechslerWechsler, 1981) and verbal IQ of 65, performance IQ of 60 and full-scale IQ of 62 were obtained.

Miss D presented to the learning disability service in 1993, following an epileptic seizure. She was a slim, dark-haired young woman with no obvious dysmorphology apart from very slight clinodactyly. She had had epilepsy since childhood, at first absence type which later became tonic-clonic in nature. As part of routine assessment in 1993, chromosomal analysis had been carried out. This was reported as a normal female karyotype 46XX. Thus, Miss D was assigned to that large aetiological group designated ‘unknown’.

During the course of Miss D's investigations, it emerged that she had a brother with a more severe learning disability. At the request of one of the authors he attended for assessment. He was of a much more placid disposition than his sister, of short stature, had low-set ears, a high-arched palate, short, stubby fingers and, like his sister, clinodactyly. His facial features were slightly coarse. There were no other abnormal findings, he did not have epilepsy.

It also transpired that Miss D had two maternal cousins who died at the ages of one year and 18 months respectively. Both cousins had multiple handicaps and no diagnosis was established in either case. Lastly, Miss D had two maternal aunts with multiple deformities. Again, no diagnosis was established; one died when a few days old, the other was stillborn.

Fig. 1 Male dup(X)(p22.13p22.31). Extra chromosomal material on the short arm of the X-chromosome is also derived from X. The patient is disomic for this region.

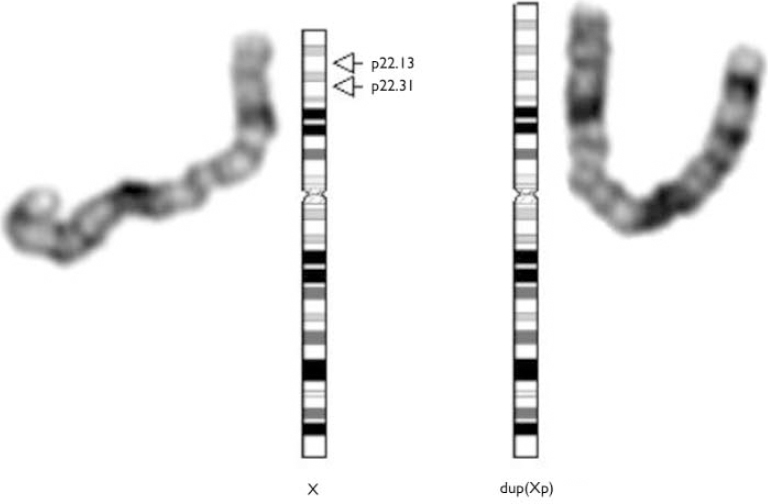

Fig. 2 Female dup(X)(p22.13p22.31). Extra chromosomal material on the short arm of the X-chromosome is also derived from X. The patient is trisomic for this region.

RESULTS

Miss D's brother's chromosomes were analysed as part of his assessment. His karyotype was 46,dup(X)(p22.13-p22.31),Y. Following this result it was decided to again examine Miss D's sample and this time it was found to have the same configuration as brother, i.e. 46,X,dup(X)(p22.13p22.31). In situ hybridisation studies using probes specific for the X-chromosome established that the extra genetic material came from the X-chromosome (see data supplement to the online version of this paper).

Wider family studies were then undertaken where it was found that their mother had the same duplication on the X-chromosome. She has no learning disability. No other family members were found to be affected.

DISCUSSION

A brief glance at the literature surrounding the X-chromosome will confirm the explosion of interest and information about its role in learning disability. It has long been known that the X-chromosome is important in the genesis of X-linked learning disability, but the information around precise genetic mechanisms is increasing year on year.

Reports of similar genetic defects

We have been unable to find any reports in the literature of duplications exactly the same as that of Miss D and her brother, although some similar abnormalities have been found. For example, Cianchetti et al (Reference Cianchetti, Muntoni and Falchi1992) described two brothers with the duplicate Xp22-Xpter.

Martinez et al (Reference Martinez, Gal and Palau1995) report linkage data in a Spanish family with non-specific X-linked learning disability. They localised the gene to the area Xp22.2-p22.3, interestingly close to the duplicated area in this family. Reichenbach et al (Reference Reichenbach, Holland and Thamm1993) described multiple abnormalities in a male child owing to duplication of the Xp21-Xp22 region. Tuck-Muller et al (1993) described an inverted duplication of the short arm of the X-chromosome in a mother and daughter. In both these cases of duplication, the area concerned was larger than that implicated in our case. Telvi et al (Reference Telvi, Ion and Carel1996) found a duplication of distal Xp associated with not only learning disability but also dysmorphic features and genital abnormalities, i.e. 46Y,invdup(X)(p22.11-p22.32).

Muroya et al (Reference Muroya, Kosho and Ogata1999) cite the example of a boy with an interstitial deletion at Xp.22.3. Boycott et al (Reference Boycott, Parslow and Ross2003) describe also a familial contiguous gene deletion syndrome of Xp22.3. Kleefstra et al (Reference Kleefstra, Yntema and Oudakker2002) have localised a gene for non-specific learning disability to Xp22.3-Xp21.3.

Whereas the above are all interesting in their own right, the overall picture they create of the X-chromosome is even more important. The above is only a small sample of the defects reported concerning the distal Xp area. Learning disability is a consistent feature of such defects.

Syndromal and non-syndromal phenotypes

It is becoming more evident that the X-chromosome is implicated in a sizeable proportion of cases of learning disability of genetic origin. It is now estimated that X-linked learning disability has a prevalence of 2.6:1000 population, accounting for over 10% of all cases of learning disability (Reference Stevenson and SwartzStevenson & Swartz, 2002). The most common of these disorders is fragile-X syndrome, with a prevalence of 1:4000 males and approximately 1:8000 females (Reference TurnerTurner, 1996). Many other less prevalent gene defects, such as that in our own case study, have now been identified. More than 150 genes associated with X-linked learning disability have now been identified.

Conventionally, the phenotypes associated with these genotypes have been split into two groups: syndromal and non-syndromal. The syndromal types are characterised by external features, neurological signs and/or metabolic anomalies. The non-syndromal types do not show such specific features; here the X-linked mode of inheritance is the only indicator (Reference Tariverdian and VogelTariverdian & Vogel, 2000).

However, recent findings have caused this distinction to become blurred, as mutations in some genes have been found in both syndromic and non-syndromic learning disability. Our case study adds to the blurring of the groups. Whereas Miss D's brother's phenotype undoubtedly falls within the syndromic group, his sister's only other physical manifestation, apart from her learning disability, was a very mild clinodactyly and epilepsy.

Clinical relevance

These findings are of great significance to both Miss D and her family. Should Miss D wish to have a family of her own then this result will enable a genetic counsellor to give her more accurate advice. It has to be realised, however, that a degree of uncertainty about the severity of the disability associated with the phenotype must exist, since Miss D's mother, herself and her brother all have the same genotype but vary greatly in their degrees of expression.

There are a number of ethical factors to be considered. Miss D and her mother consented to blood tests after counselling. Miss D's brother does not have the capacity to understand the issues involved. Moreover, other family relatives who were not involved in the original decision may also have the particular genetic defect and will now be faced with difficult decisions.

On a wider scale, the case adds to the momentum for even further research into the causes of learning disability. When the defects have been fully elucidated at the gene level, it may be possible to have gene therapy treatment which may be available in the medium to long term. This no doubt will bring its own ethical considerations.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.