Introduction

Before it even began, the unification of Europe had been thought of in constitutional terms. This was most visible at The Hague conference in 1948, and most importantly, in 1952, when negotiations for a European Political Community were officially launched by the six members of the European Coal and Steel Community. While the European constitutional project was severely dampened when France rejected the proposed treaty without even a vote, far from disappearing, it was gradually transferred to the European Economic Community (EEC). The most famous example of this transfer is perhaps provided by the first President of the European Commission, Walter Hallstein. From the late 1950s, he defined the EEC as a ‘Community of law’ (Rechstgemeinschaft), whose law formed an autonomous and superior legal order, equivalent to an actual constitution. The ‘Community of law’ concept has since made its way into official European parlance.Footnote 1 It was even, eventually, used by the European Court of Justice to suggest that the treaties operated as a ‘constitutional charter’ of the EEC.Footnote 2 In spite of the staunch opposition from the many ‘internationalists’ who have claimed that the EEC was, in fact, nothing but an international organisation, this ‘imaginary constitution’ has increasingly been accepted in practice, as well as in theory.

In this paper, I would like to move the focus of this traditional narrative of the ‘constitutionalisation’ of Europe from the conflict between so-called ‘constitutionalists’ and ‘internationalists’,Footnote 3 and to place it instead on the diversity among the ‘constitutionalists’ themselves. Indeed, fundamental as the former might have been, focusing exclusively on this divide tends to cloud other important issues. In particular, I will emphasise that the constitutional interpretations of European integration that were advocated at the time by several groups concealed crucial differences. While they generally agreed on the idea of a supreme European law to take priority over national rules, they did so in the name of different conceptions of the role of law, and of its relationship to democracy and the market. Such differences were by no means incidental, as might be assumed if one concentrates solely on the common opposition to ‘internationalists’. Instead, exploring the specific articulations of law, market and democracy in these projects sheds light on the various foundations, drivers and horizons imagined for European integration by the ‘constitutionalists’. It highlights that, then as now, under the surface of a ‘constitutional’ language, the fault lines between the different imaginaries may run deep. The ‘Community of law’ put forward by Hallstein was one of these conceptions, but by no means the only one. Therefore, it is also necessary to understand why his conception was more generally accepted than the other available alternatives. It is to the elucidation of the ‘Community of law’, and of the reasons for its success, that this paper is dedicated.

The aim of this article is twofold. First, reaching back to the early years of the European project allows new light to be shed on the meaning and implications of the ‘Community of law’. It helps to clarify how conceptions of the ‘constitutional’ law of European integration were embedded in a more complex imaginary of a market-to-be built and a democracy-to-come. This issue is not only of interest to the intellectual historian: it also helps to identify some contemporary shortcomings of the imaginary that emerged at the time. In particular, it was assumed that the rule of law, free market and democracy could be constructed through a depoliticised process driven by legal integration, and through which they would mutually strengthen each other. At a time of acute challenge to the rule of law in some member states, it is crucial to remember that, at the time, it was hardly envisioned that member states could, themselves, endanger the rule of law or democracy.Footnote 4

Second, this paper would like to bring to light what it takes for a particular concept – the ‘Community of law’ – and the imaginary it carries with it to succeed in becoming routinely accepted in European integration. By tracing how a highly idiosyncratic concept has successfully interwoven legal, political and economic ideas, shaped in different national and intellectual contexts, this paper seeks to contribute to a more precise and contextual socio-historical understanding of the making of transnational constitutions. It unearths the complex strategies and processes at work, and, more specifically, the interplay of political and academic strategies. Such patient analyses are, it is contended, a condition for restoring a sense of agency in a history of European legal integration still often imagined as driven by necessity and the sheer ‘logic of things’.Footnote 5

From the imaginary constitution to the constitutional imaginary of the EEC

Dealing with such questions requires a broad perspective on European constitutional debates. In order to provide this, it will be useful to move from the history of the ‘imaginary constitution’ of Europe – how Europe was presented as a constitutional entity depite formally lacking one – to that of the ‘constitutional imaginary’ of the EEC.Footnote 6

A constitutional imaginary,Footnote 7 as understood here, can be regarded as a broad set of representations. It can be contrasted with two closely related concepts: constitutional paradigm; and constitutional imagination. Much like a constitutional paradigm, it offers ‘a relatively stable understanding’ of, in this case, the European Union and its law.Footnote 8 A synthetic formalisation of existing institutional arrangements,Footnote 9 it provides shared ‘ways by which [they] can be “explained” and justified’Footnote 10 – and, ultimately, contributes to their legitimation. However, referring to an imaginary suggests that it goes beyond a mere constitutional paradigm. As pointed out by Anderson, imagination has to do with absence: the nation is an ‘imagined community’ because we do not have direct relations with each of our fellow nationals.Footnote 11 Imagination extends our sense of belonging beyond the circle of those we actually know. Likewise, while a constitutional paradigm is concerned with actual arrangements, a constitutional imaginary includes further dimensions, generally not fully spelled out in legal rationalisations.

This brings us close to the idea of constitutional imagination, as delved into by constitutional theory.Footnote 12 Only, while constitutional imagination can be defined as the process of collectively exploring the implications of a particular set of rules, a constitutional imaginary is made up of the representations resulting from such a process. For instance, it encompasses general representations about the legitimate distribution of power, the conditions of membership in the community or a historical narrative explaining how it was shaped and where it is headed. Insofar as these representations are oriented towards an order yet to come – as in the case of the early EEC – an imaginary can directly challenge the established order, such as that of nation states in Europe. Here, I will explore representations touching on the legitimate distribution of power (democracy, market regulation), as well as the narrative about the future development of the European Communities, leaving the issue – however important – of membership aside.

Given its dual potential (legitimisation and contestation), shaping a constitutional imaginary is an activity with highly political stakes. A constitutional imaginary is usually produced and circulated by constitutional experts – judges, legal scholars or even politicians. However, its success, i.e. the way it becomes widely accepted and used (or not), is by no means predetermined. It results from a social process, through which this ‘collective self-representation’ is not only produced, but also circulated and promoted.Footnote 13 To analyse this process, I will use the concept of ‘co-production’, developed by Vauchez about European legal integration. This concept emphasises the joint work of politicians, civil servants and legal professionals in forging and advocating European constitutional representations.Footnote 14 Politicians and judges, as well as legal scholars, have come to play a crucial role in this process.Footnote 15 They not only contribute to forging a constitutional imaginary; they also allow it to circulate beyond the narrow circles in which it originates,Footnote 16 and try to build coalitions of supporters testifying to its legitimacy.Footnote 17 To account for the emergence and success of a constitutional imaginary, one thus needs to look into the representations carried by constitutional imaginaries, as well as into the process of their circulation within, and eventual endorsement by, a broader community. In a nutshell, it requires the knotting together of the analysis of ideas – about law, democracy and market – with their uses in the actors’ strategies.

Hallstein and the ‘Community of law’

Within the limited scope of this paper, I propose to apply this program to Hallstein and his idea of ‘Community of law’, in order to explore the constitutional imaginary attached to it. Of course, he was not alone in expounding such ideas, and one should be careful not to lionise him. Yet, concentrating on a single figure allows for a fine-grained investigation of how his ideas took shape, and how he was able to promote them.

Hallstein and his ideas have elicited a fair amount of historical, sociological and legal work. Once a ‘forgotten European’,Footnote 18 whose name was inescapably stained by the failed attempt at strengthening the EEC powers that led to the ‘empty chair crisis’, Hallstein has since been the subject of more careful investigations.Footnote 19 In particular, his ideas for European integration have been much discussed.Footnote 20 The traditional emphasis on his federalist commitment has been balanced by his supposed reliance on theories forged by neo-functionalist political scientists (most notably Haas) to explain his general vision of Europe, and the ‘empty chair crisis’.Footnote 21 Likewise, his role in the legal debates of the early years of European integration has been variously assessed. While his contribution to the ‘co-production’ of the ‘Community of law’ at the intersection of academia and politics has been abundantly stressed,Footnote 22 this reading is sometimes accused, in an idealistic vein, of putting too much weight on strategic behaviour.Footnote 23 Instead, it would have been successful because it was the only, or at least the most coherent, constitutional vision for the EEC.

I will address both issues on the basis of multiple sources that afford a detailed picture of Hallstein’s ideas and strategies. This article provides a close reading of Hallstein’s legal texts, published throughout his long career before and after European integration, and carefully places them in the context of his intellectual and professional biography; in addition, it is based on original archives about his career before European integration.Footnote 24 This will allow the intellectual genealogy of the concept of ‘Community of law’, as shaped by Hallstein, to be traced, along with the political mobilisation that helped turn it into a successful definition of the EEC. I will argue that his was a specific constitutional imaginary in the way it articulated law, market and democracy. It was neither the only available, nor identical to other available constitutional imaginaries – but it could appeal to them in its account of European integration as a depoliticised process of submitting to a higher law. Its success was further fostered by the fact that Hallstein was indeed able and willing to mobilise unparallelled social resources both in the academic and political spheres, which contributed to legitimising his interpretation of the EEC. I will show that this relationship between politics and academia, far from being the result of an excessively strategic reading of his career, was theorised by Hallstein himself long before he became involved in European integration. This justified in advance his eventual mobilisation of academic and political resources to promote the ‘Community of law’. Thus, the combination of the original intellectual resources it offered and of the mobilisation of this large social resource helps explain why the ‘Community of law’ was a more successful European constitutional imaginary than other alternatives.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. In a first part, I contrast two very central constitutional imaginaries of the early EEC: one ‘political-federalist’, and the other ‘functionalist’. I show that each offered a specific articulation of law, market and democracy, respectively emphasising democracy or the market as its foundation, and deriving distinct projects from there. In the second part, by pointing out relevant dimensions of Hallstein’s intellectual and political trajectory, I show how his European constitutional ideas took shape to form a third constitutional imaginary – the ‘Community of law’ – proposing a different, more legally-oriented relation between law, market and democracy. In a final part, I consider the mobilisation that made this imaginary successful, by showing how he himself had conceived of the proper relationship between science and politics, and how he accordingly sought to promote the ‘Community of law’.

Imagining European constitutions

When thinking about the origins of European constitutional representations, it is most common to emphasise their links to pacifist advocates of ‘peace through law’.Footnote 25 Throughout the second half of the 19th and the early 20th centuries, movements advocating a better legal regulation of international relations emerged in the Western world. They promoted a law aimed at curbing the will of sovereign states, whose rivalry had extended to the world through colonisation before dragging states into European wars. Law was therefore conceived as an instrument of ‘civilisation’ for states, limiting their ability to go to war by submitting them to a higher, non-national legal rule.Footnote 26 However, others mobilised with the more practical aim of regulating international trade through law, in order to limit the disruptive influence of states’ aggressive policies on private business. In the German Empire, in particular, the development of state intervention and the codification movement had revealed the danger of a control of private law – largely conceived, after Friedrich Carl von Savigny, as a non- (or even anti-) state law – by the state. Footnote 27 In this perspective, practical reflections about both public and private international law, that is a law standing above national laws and binding on states, developed.

Out of these efforts slowly solidified various representations of Europe as a constitutional entity. After the Second World War, the idea of limiting state powers through binding laws was partly taken up by European movements.Footnote 28 They no longer attempted to create a global constitutional law. Rather, advocates of a global constitutional law increasingly reconverted into European activists.Footnote 29 Yet, several ways of articulating these constitutional ideas were available. Differences appeared in particular as to the articulation of law, democracy and market. Thus, it is more accurate to write about European constitutional imaginaries. Here, I will first consider what can be labelled the ‘political federalist’ imaginary, advocated for instance by Altiero Spinelli. I will then contrast it with a functionalist constitutional imaginary, illustrated not so much by the political theory of Haas or the practice of Monnet, as by the legal theory of Hans-Peter Ipsen.

The political federalist constitutional imaginary

A first European constitutional imaginary took shape early on, during the very first years of European integration. Much like those who had supported the ideal of peace-through-law before them, its advocates diagnosed the exhaustion of national politics: Europe was sick of its nations, whose exacerbated sovereignty led to the wars and disasters of the 20th century. In this situation, federalism provided a model and a large number of proposals for federal constitutions were made between 1945 and 1954.Footnote 30

European constitutionalism as it (re)emerged during this period under federalist auspices largely referred to pre-existing federal models, first and foremost the American model, but also, to some extent, the Swiss model. One of its most prominent political advocates in the early years of European integration was Spinelli.Footnote 31 His ideas were largely forged during the war and his time in prison; he pleaded for a strong measure of pragmatism in order to face the challenges of post-war Europe. Indeed, he borrowed from practically-oriented political thinkers, such as Machiavelli and – most importantly here – Hamilton.Footnote 32 Besides, he also was a fervent political advocate of his ideas. During the debate of the European Defence Community, and its twin, the European Political Community, he was extremely active in developing his ideas and rallying supporters around his conceptions of a constitutional Europe. He surrounded himself with professional jurists, many trained in the US. As early as March 1952, before the beginning of the work of the ad hoc Assembly, the European Movement had already planned the creation of a ‘Committee of Jurists’ – renamed in May 1952 the ‘Study Committee for the European Constitution’ – which was to reflect on the modalities of a political organisation of Europe. Its initial composition is evocative of its position at the intersection of federalist activism and legal technique:Footnote 33 In addition to political personalities such as Spinelli himself, the Committee was supported by a team of Harvard professors under the direction of Carl Friedrich, himself a specialist of federalist ideas, and of Robert Bowie, John McCloy’s adviser for the American zone in Germany.

Generally speaking, such federalist plans were oriented towards the creation of a European constitutional democracy. Of course, at the time, most plans for Europe included a Parliament elected by universal suffrage.Footnote 34 But Spinelli went beyond mere institutional design to advocate a voluntaristic and deeply political conception. He refused both the notion that European integration depended on the pre-existence of a cultural, pre-political community (what would later be known as the no-demos thesis), and the belief that it could succeed solely on the basis of depoliticised, economic or legal, processes (what would be illustrated by Monnet, on the one hand, and the ‘integration-through-law’ model, on the other). Instead, he conceived of a constituent ‘moment’ during which a constituent assembly would establish a new sovereign political being – in line with the tradition of federalism illustrated by the Philadelphia convention.Footnote 35 This implied that a European people would emerge as soon as it acted together politically to decide on the shape of its future constitution. In this view, the constitution was the operator through which the problem of national sovereignties could be resolved in Europe, that is, by submitting them to a higher legal order on which European peoples would have democratically agreed.Footnote 36 It was thought to be the occasion to firmly root European integration in democracy.

In this picture, a European constitution was legitimate only insofar as it was based on a clear democratic decision made by a constituent assembly. Only on this democratic foundation could a legitimate European constitutional law unfold. Therefore, it did not borrow much from international law, but rather from the field of internal constitutional law: such a constitutional law was central in regulating the precise functioning of the new European entity, and to ensure fundamental rights guarantees for the new European citizens. Nevertheless, the European constitutional law was, here, only a secondary product of the political decision of European citizens. Tellingly, while Spinelli was active during the drafting of the legal framework of the European Political Community in discussing the legal provisions of the future European constitution in great detail, and pleaded consistently to conceive of the future European constitution as a higher law, binding on member states and with direct effect for its citizens, he was also careful to prevent any possibility of a ‘government of judges’.Footnote 37

Likewise, questions regarding the role and design of the market in the future European federation were subordinate to decisions of the future European democratic assembly.Footnote 38 For instance, in the discussions of the multiple committees in charge of preparing the constitution of the European Political Community, in which Spinelli participated, it is striking to observe the imbalance between institutional questions and economic ones. While some federalists advocated specific economic ideas – for instance, ‘integral federalists’, insisting on subsidiarity, were decided advocates of some kind of corporatismFootnote 39 – these were not at the forefront of the constitutional debates of the time. Spinelli himself had expressed a clearly left-leaning economic vision in his celebrated Ventotene Manifesto,Footnote 40 but adopted a rather pragmatic approach to this matter in the 1950s. It would be for an elected Assembly to make the basic economic choices about the future European federation.

This federalist constitutional imaginary of European integration thus was centred – and indeed founded – on democracy, to which the legal and economic dimensions were subordinated: a constitutional Europe would result from a constituent moment mobilising the European people. It would progress through constant democratic deliberation and, eventually, would constitute a fully-fledged democratic federation.

The functionalist constitutional imaginary

This was not the only way to imagine what a European constitution might look like, though. Another might be labelled the ‘functional constitution’. This label will most likely suggest a link with the views of some pioneers of European integration, such as Monnet, in the political arena, or Haas, in the academic field. Yet, while this imaginary bears an affinity with both, especially in its emphasis on depoliticised administrative structures regulating the market, it is markedly different in its approach to law. For neither Monnet nor Haas were very concerned with constitutional issues: They regarded European integration as a primarily economic process, regulated through administrative means, leading to a democratic community – but hardly as a formally constitutional entity.

Others, however, also envisioned European integration as a process of functional integration driven by economic processes and governed by administrative procedures, but paid more careful attention to its legal dimension. This was, for instance, the case with an active group of French lawyers trained in administrative law, such as Pierre-Henri Teitgen, Maurice Lagrange or the head of the Legal Service of the European Communities, Michel Gaudet. But a distinct, and most peculiar, illustration of such a view is to be found in the work of Hans-Peter Ipsen. A German professor of administrative law who had been deeply compromised during the Third Reich, he was nevertheless central to the early debates on the new German constitution after the war, and to the beginnings of Community law in Germany.Footnote 41 In his 1972 textbook – a synthesis of his previous work initiated in the 1950s – he presented a vast theory of European integration and its ‘constitutional principles’, which proposed a different, but influential, constitutional imaginary of the Communities.Footnote 42 I do not mean that Ipsen’s constitutional view of Europe was identical to that of Monnet or Haas, or to that of French administrative lawyers. Rather, it illustrates the radical potential implications of a legal functionalist approach to the European constitution.

Ipsen unambiguously opposed jurists who sought to reduce Community law to traditional international law. Community law was constitutional, since the treaties were functionally equivalent to a constitution adopted by the member states. The Communities thus formed a constitutional order ‘of their own’, similar to that of the former German Empire.Footnote 43 However, Ipsen was staunchly opposed to federalists – and he would include Hallstein in that group – as he refused the idea that European integration would result in a European federal state, created by a grand constitutional ‘moment’ similar to the Philadelphia Convention. Instead, the ‘functionalists’ – among whom he counted himself: he also made explicit references to American political science and the concept of ‘spill-over’ for instance – did not think of integration as being anything similar to a state.Footnote 44 The Communities were, he argued, of a much more limited purpose, essentially concerned with economic functions. He accordingly defined Communities as a ‘grouping of functional integration’ (Zweckverband funktionneller Integration). Hence, there was a European constitution, but it was understood as a process that would not predictably lead to a (federal) state. Neither constituent moment nor constituent assembly was required. As we will see, while Hallstein agreed on the processual definition of integration, he rejected its purely functional definition.

Defining the Communities as purely functional organisations had the consequence of placing the market at the foundation of European integration. Indeed, Ipsen insisted that the process of European integration would more accurately be compared to the emergence of international economic law, that is of a non-state law limited to a specific area of social life. In this vein, he actually defined Community law as a ‘mutation of economic law’.Footnote 45 Moreover, this involved a peculiar understanding of the issue of democracy. Community law does not emerge from a democratic constituent moment, as in the federalist view. Indeed, not being conceived on the model of the sovereign state endowed with overall competence, the Communities are not subject to the same requirements of legitimisation: they need not be democratic.

As early as the 1959 Congress of the Staatsrechtslehrer, he had judged the whole controversy – crucial in Germany – over fundamental rights in the EEC to be exaggerated, insofar as, from the perspective of EEC law, citizens of the Community are ‘bearers of economic functions’, that is, ‘market citizens’ (Marktbürger).Footnote 46 These citizens do have economic ‘fundamental rights’: access to the four fundamental freedoms on an equal basis for all citizens (non-discrimination), guaranteed by judicial bodies. These rights are matched by ‘duties’ – in particular the prohibition of all discrimination in the Common Market. There is, therefore, no need to think of a more democratic organisation for the Communities. In this regard, Ipsen’s view differed from other functionalists, such as Haas, who at least until the ‘empty chair crisis’ pondered on the possibility of the EEC slowly transforming into a fully-fledged democratic federation.Footnote 47

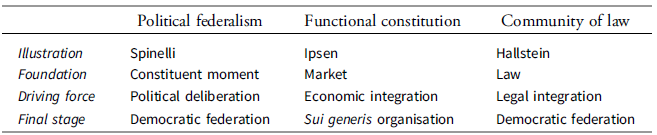

On the basis of ideas developed since the 19th century, two rival constitutional imaginaries took shape in these years (see Table 1). One referred to the ideal of peace through law, and elaborated on a democratic federal Europe; it was grounded on a fundamental popular decision, and evolved through democratic deliberation, by which its legal and economic developments were shaped. The other, however, alluded to the regulation of economic relations imagined earlier in the field of economic law; the market was the starting point of a process of integration, and only in relation to economic goals could the legitimacy of European projects and institutions be assessed. Here, the law was but a tool of economic integration, and European democracy was restricted to the (economic) activities of ‘market citizens’. Consequently, while political federalists envisioned a deeply political decision resulting in a democratic federation replacing nation states, the functionalist imaginary revolved around something quite different – in fact, a new, sui generis, type of organisation, not in the least resembling a state.

Table 1. Two early constitutional imaginaries of the European Communities

Politically, the ‘constituent’ version was severely damaged by the failure of the European Defence Community in 1954, and the ‘functionalist’ seemed to collapse after the ‘empty chair crisis’ erupted about ten years later. But this was not the end of European constitutional imaginaries. Part of the explanation of this paradox,Footnote 48 I will argue now, is that the ‘Community of law’ differed from these models, even though it was able to appeal to both.

Inventing the ‘Community of law’

During the first years of European integration, these two models for a European constitution gained increasing audience. In parallel, Hallstein also elaborated and put forward the concept of a ‘Community of law’. It has been claimed that this understanding of the EEC, and incidentally the ‘empty chair crisis’, had their origins in the functionalist model of processual integration, notably as it was developed by Haas.Footnote 49 Alternatively, it has been described as expressing a deep federalist commitment.Footnote 50 Yet, I will argue that this concept of ‘Community of law’ cannot be reduced to any of the models outlined above. Instead, while echoing some of their features, it forms a third autonomous constitutional imaginary.

This constitutional imaginary was shaped by Hallstein’s own specific intellectual and political trajectory. It was coherent with his academic training in private international law, as well as suited to his political vision for Europe, as President of the first European Commission. As a result, it provided new argumentative resources to various advocates – academic or political – of a European constitution. While it echoed federalist projects, it articulated the issues of democracy and market in a very different way, resonating with the more incremental approach of functionalists.

The professor and the president

The career of Hallstein up to 1958, when he became the first President of the European Commission, placed him at the crossroads of academic debates and of federalist efforts to build a peaceful Europe. This specific trajectory provided him with the intellectual tools to develop his concept of a ‘Community of law’.

In 1925, at the University of Berlin, Walter Hallstein defended a thesis on private international law in the Treaty of Versailles. Appointed professor of private law in 1929 (which made him the youngest law professor in Germany), he eventually directed the Institute of Comparative Law in Frankfurt. His work was in line with the German tradition of private and comparative law initiated by Savigny. For instance, he published an article in 1942 in which he developed the idea of a private law that would express and constitute the unity of a ‘people’ (Volk), alongside history and blood.Footnote 51 But analysing the contemporary developments of private law, he evoked the irresistible ‘push towards the community’ (Drang zur Gemeinschaft) and the dangers that this entailed for private autonomy. These same themes occupied him after 1945. From 1946, he was co-editor of the Süddeutsche Juristenzeitung, which took over from the Deutsche Juristen Zeitung (founded at the end of the 19th century by Paul Laband and then edited by Carl Schmitt in the 1930s). In the first issue, he published the speech he gave when he took office as rector of the University of Frankfurt. There, he stressed the dangers created by the extension of states’ powers for the individual, and for law in general (the editorial of the first issue opened with this sentence: ‘This journal wants to serve the law. No more, no less’) and the need to ‘restore’ private law in the face of this danger.Footnote 52

Hallstein was also acquainted with federalist ideas and political movements, especially as they were understood in the US. Taken prisoner in Cherbourg in 1944, he was sent to the US, where he organised law courses during his detention, and followed an American training program for the reconstruction of Germany. After his release, he came back to Germany but in 1948–1949 he was invited to stay at the University of Georgetown, which allowed him to further develop his international profile and his connections to the English-speaking academic world. He also attended The Hague Congress in 1948 and defined himself as a convinced European federalist, even though – as we will see – he represented another strand of federalism than that of Spinelli.

In the particular context following 1945, these credentials helped open to him the doors to a political career.Footnote 53 Indeed, in Germany, ‘new men’, non-politicised, competent and, as far as possible, on good terms with the Allied powers, were being sought to succeed those who were too compromised under Nazism. Many academics then entered politics. The ministry of Foreign Affairs was particularly involved in this logic of technical recruitment, since it did not have a Minister until 1955, remaining under the direct political control of Adenauer and the technical responsibility of his Secretary of State. In this context, Hallstein, who had belonged to several organisations linked to the National Socialist German Workers’ Party but had never been a member of the party itself, was recruited to take part in the UNESCO negotiations. He then led the German delegation to the Schuman Plan negotiations, and was appointed State Secretary for Foreign Affairs (1951–1958). In this capacity, he attached his name to a crucial aspect of West Germany’s foreign policy during the early Cold War, the ‘Hallstein doctrine’, asserting that the Federal Republic of Germany would end diplomatic relations with any country recognising its East German counterpart. Later participating in the negotiations of the Treaty of Rome, he was chosen as the first President of the EEC Commission in 1958, a position he left in 1967, following his confrontation with de Gaulle during the ‘empty chair crisis’.

The choice of Hallstein for this position and to lead the negotiations is evocative of this particular situation: he was not a member of the Christian Democratic Union at the time, and had no significant political experience. But Adenauer had precise criteria in choosing who would lead the Schuman Plan negotiations: he was looking for ‘a jurist who is known both in Germany and in international circles’, who did not appear to be connected with the war, and who would in a way be the ‘German Monnet’ – i.e. who would lead the technical negotiations under the political responsibility of the Chancellor.Footnote 54 When Adenauer finally chose Hallstein, he insisted that he retained his chair at the University of Frankfurt, and thus a certain material independence from politics, which he readily accepted.Footnote 55 It is in this space – between politics and university – that Hallstein’s special position rested. This hybrid character would be reflected in his concept of ‘Community of law’ and its eventual development.

The EEC as a Rechtsgemeinschaft

In the late 1950s, Hallstein formalised his own understanding of a European constitution. For him, it was then, of course, a question with direct political stakes: not only did it represent a direct intervention in the lively German debate;Footnote 56 as President of the European Commission, his theorisations were aimed at legitimising the EEC and his vision for its future. By constructing an interpretation of the EEC as a constitutional organisation, he very directly attempted to distinguish it from traditional international organisations with limited powers. Instead, he too, adopted a federalist perspective: The constitutional questions raised by the EEC were similar to the ‘federal problem’ of uniting several components.Footnote 57 Yet, the EEC was defined as an ‘incomplete federation’, at best ‘analogous to a state’, but certainly not identical to it.Footnote 58 It is the positive definition he gave of the EEC that remained famous: it is a ‘Community of law’.Footnote 59 This means that it is ‘a creation of the law; it is a source of law; and it is a legal system’ – in short, it is ‘a realisation of the idea of law’ itself.Footnote 60 This asserted the constitutional dimension of the EEC, but it offered a constitutional imaginary deeply different from that of federalists à la Spinelli or of functionalists such as Ipsen, who rejected the definition of the EEC as international without endorsing the federalist imaginary. In fact, it connected various pre-existing strands of legal thought in a new composite concept, which was, because of its very ambiguity, able to appeal to many lawyers and politicians of the time.

The definition as a community of law (Rechts-gemeinschaft) bore affinities with the rich legal controversies of the interwar period: on the one hand, it echoed the debates of the Weimar Republic, especially touching on the issues of the ‘Rechtsstaat’ and of positivism; on the other hand, it also reflected transnational discussions of peace through international law. First, the concept of a Community of law inevitably conjured up a concept of the rule of law (Rechts-staat) that had been much debated in the preceding decades. It had revolved around two understandings, both of which were echoed in Hallstein’s concept: a formal conception, in which public authority was committed to abiding by existing laws, regardless of their actual content – a formalism whose dangerous consequences had been amply illustrated under Nazi rule;Footnote 61 a more substantial conception, emphasising the protection of individuals’ rights against state powers. The ‘Community of law’ alluded to the former conception to the extent that it implied that the EEC had to formally guarantee the identical enforcement of its rules in the six member states. This directly justified the primacy of EEC law, in order to prevent differences from appearing between member states.Footnote 62 It thus was a clearly hierarchical vision of the relationship of EEC and national laws. But the substantial meaning of the Rechtsstaat was also hinted at: as a Community of law, the EEC not only guaranteed but also directly created rights for the citizens of the member states.Footnote 63 In practice, Hallstein was an early supporter of setting up a European court charged with overseeing their enforcement.Footnote 64 This dimension would eventually be deepened, following reflections about the necessary ‘structural congruence’ between the protection of fundamental rights by the German constitution and by EEC law – an issue which had been raised early on in the German legal debate and that led to the Solange case.Footnote 65 In this sense, the Community of law was also in line with the liberal idea of the constitution as a barrier against arbitrary power. Only, it was mostly concerned with ensuring that the EEC would not endanger these rights – not so much with the risk of member states destabilising these rights themselves.

In insisting on curbing state powers, the ‘Community of law’ was equally in line with pacifist projects of constraining states through international law. Since the end of the 19th century, international legal debates had been replete with plans aimed at strengthening international law. The concept of ‘supranational law’ had actually been shaped in these debates.Footnote 66 As was especially illustrated by French (Scelle) or American (Snow) lawyers of the time, these efforts were infused with notions derived from the social sciences and firmly rejected legal positivism.Footnote 67 The emergence of a stronger international law would simply be the consequence of the historical process of growing international interdependence between states, economies and individuals. Such ideas were, of course, reflected in the attempts to secure peace through public international law, but in private international law, Hallstein’s initial discipline, a similar trend towards a more ‘realist’ understanding of the law had also emerged. Indeed, his concept of ‘Community of law’ resonated with these older theorisations: as a creation of law, he insisted, the Communities were the result of a general historical process whose sources are to be found in the depths of European history. Law has finally succeeded in uniting Europe where ‘blood and iron’ have failed.Footnote 68 A ‘Community of law’ would therefore be nothing short of the realisation of the ‘majesty of law’Footnote 69 – or, as earlier writers might have wanted to put it, of the ‘sovereignty of law’.

This realisation would be the result of a long process. In agreement with functionalists, he claimed that the Community ‘is not a being (Sein), it is a permanent becoming (Werden)’.Footnote 70 This processual understanding responded to some extent to the conceptions of functionalist political science, which, as White has shown,Footnote 71 were familiar to Hallstein and his advisers: they predicted the regular development of integration from sector to sector. But it also resonated with the tradition, especially vivid in Germany, of conceiving of law as a product of social and economic activity – as opposed to a centralised creation. For instance, Rudolf Smend – whose teachings the young Hallstein had once followed, and who had been involved in the bitter discussion of the European Defence Community in the 1950s – had proposed an understanding of the constitution as expressing a social process of ‘integration’.Footnote 72 Similarly, Hallstein emphasised that one can speak of a European ‘constitution’ in the broader sense of a system of norms incrementally produced by the functional requisites of European social and economic life, rather than by a fundamental constituent ‘moment’. Indeed, he observed that states and the EEC formed a ‘harmony’ in which legal orders are intertwined like the living tissues in an organism.Footnote 73 Crucially, this harmony was not the result of a ‘master plan’, but of the slow adaptation of norms and practices to a new reality. As early as 1951, Ophüls – his colleague at the Department of Foreign Affairs and the University of Frankfurt – had also called for Community law to be conceived in the tradition of Savigny, as the result of a creative force emanating from social life itself and partly independent from voluntary action.Footnote 74 This ‘living’ and ‘growing’ character indeed made it a real Community.

Regarding the final stage of this process, however, Hallstein strongly disagreed with Ipsen. He endorsed the idea of the EEC becoming a fully democratic federation. But he did not see this as the result of a grand constituent moment. He emphasised that, in essence, legal and economic integration were political phenomena. They would automatically foster democratic aspirations among citizens, which the EEC would have to satisfy if it wished to remain legitimate: The demands for increased democratic control over the Communities would lead, in the long run, to the ‘politicisation’ of the EEC, which would in turn result in the election of the European Parliament by universal suffrage and the strengthening of its powers to equate to those of a true federal Assembly.Footnote 75 This suggested a convenient path forward for European integration: far from requiring a ‘leap of faith’, a brutal conversion into a political union, it would naturally follow from legal integration. Hence, the law itself – not the market, nor deliberation per se – was to drive European integration into becoming a democratic federation: the conceptual basis of what would become known as ‘integration through law’ was laid.

In the context of the time, such a conception further resonated with those who claimed that the free market needed to be insulated from public interferences. Indeed, assuming that ‘the basic law of the European Economic Community, its whole philosophy, is liberal’,Footnote 76 Hallstein connected his federal institutional views with a liberal economic philosophy. In this, he echoed the ideas, developed in an important text by Hayek, published in 1939, on ‘the conditions of interstate federalism’. There, the Austrian economist had argued that while ‘an essentially liberal economic regime is a necessary condition for the success of any interstate federation, […] the converse is no less true: The abrogation of national sovereignties and the creation of an effective international order of law is a necessary complement and the logical consummation of the liberal program’.Footnote 77

In Germany, closely related ideas were also discussed by so-called ordoliberals. Böhm, a colleague of Hallstein at the University of Frankfurt, developed the idea of a ‘private law society’,Footnote 78 following the economist Eucken, and largely based on coordination through private contracts. Hallstein was also familiar with the work of Groβmann-Doerth, a colleague of Eucken in Freiburg, who had conceptualised economic law as a ‘self-created law’ (selbstgeschaffenes Recht). Footnote 79 In his view, the law ‘constituted’ the market, that is, made its very existence possible. The role of the state was essentially limited to securing an ‘economic constitution’, that is, to building the institutional framework of the market. In a strikingly similar formulation, Hallstein stated that European integration ‘is integrating […] the role of the state in establishing the framework within which economic activity takes place’.Footnote 80 The point here is not to identify Hallstein’s understanding of the European constitution and ordoliberal theory – in fact, Hallstein and one of the most prominent political representatives of ordoliberalism, the Minister for Economic Affairs and later Chancellor Erhard, clashed on several occasions regarding European integration.Footnote 81 Nevertheless, it is relevant to emphasise that in both cases, they elaborated on the idea of a constitutional law independent from state authority but instrumental in establishing and securing the operation of the market.

In the early years of European integration, the ‘Community of law’ was one out of several available constitutional imaginaries of the Communities. When analysed as such, it becomes clear that, in spite of resemblances – the constitutional nature of EEC law, i.e. a common opposition to ‘internationalists’ – each imaginary consisted of a specific articulation of law, market and democracy (see Table 2). Ultimately, they offered different foundations, dynamics and political perspectives for European integration: according to Spinelli, a constituent moment initiated a process of political integration leading to a full-fledged democratic federation inspired by the US; in Ipsen’s view, the creation of a large market opened the path to the emergence of a functional organisation sufficiently distinct from a state not to require any democratic legitimation; in Hallstein’s understanding, the creation of a European law responded to and fostered the realisation of a century-old process of legal integration leading to a democratic federation, without requiring a great constituent moment. In this, it inherited and appealed to both the peace-through-law tradition endorsed by many federalists, and the tradition of private law that had developed vividly in Germany.

Table 2. Three early constitutional imaginaries of the European Communities

Promoting a constitutional imaginary

How, then, did the constitutional representation of European integration offered by the Rechtsgemeinschaft succeed more than the others available at the time? It is all the more surprising as it is often interpreted as the intellectual source of the confrontation with de Gaulle during the ‘empty chair crisis’, which eventually led to the demise of Hallstein. As we just saw, part of the answer to this puzzle is that it offered convenient intellectual resources to conceptualise the EEC as a de facto constitutional entity, in the process of becoming a political union. As such, it was a compromise for those who had regarded federalist enthusiasm with suspicion, as well as for those federalists disappointed since the failure of the European Defence Community in 1954. However, focusing only on these intellectual resources leaves us halfway to an explanation. In order to understand how, in effect, this representation gained ground, it is necessary to also clarify how it was promoted and circulated.

To that aim, one should consider the social resources its advocates were willing, and able, to mobilise in their efforts to promote the ‘Community of law’. In this regard, Hallstein was in a very favourable position, at the intersection of academia and politics, and proved an extremely active advocate of his views. Being able to play on both academic and political fields allowed him to create a broad coalition of support around it. Far from alluding to a ‘conspiracy’, as is sometimes misleadingly suggested,Footnote 82 this analysis, emphasising the entanglement of politics and academic knowledge during the early years of European integration, was actually theorised in Hallstein’s own writing.

Hallstein and the politics of knowledge

Long before he was appointed President of the European Commission, or even started a political career, Hallstein had reflected on the relationship between science and politics. He had summarised his views on the issue on several occasions after the war. Contrary to the positivist understanding of a formal separation between science and politics, he had pleaded for a strong relationship between both areas. This helps cast light on his promotion of the ‘Community of law’ during the early years of European integration, for it can be regarded as the direct practical application of his reflections.

After 1945, Hallstein had been particularly involved in the reconstruction of German universities – first as a Professor and then as Rector of the University of Frankfurt (1946–1948) and President of the Rectors’ Conference of South Germany. The debate during this period on the relationship between political power and universities was extremely lively. This was not only because of the Nazi annihilation of the tradition of academic independence inherited from Humboldt. The Minister of Religious Affairs and Education of the Land of Hesse made a speech on 19 March 1947, in which he proposed, among other things, the establishment in the universities of supervisory boards (Kuratorium) including representatives of the government. The rectors, including Hallstein, vocally opposed this proposal in the name of academic independence. This, they claimed, would practically mean (re)introducing a political control of academic work.

In this context, Hallstein developed his theses on the ‘good’ relationship between science and politics on several occasions. As early as 1944, he had raised these questions before an audience of German prisoners in the US.Footnote 83 Lecturing on the ‘social and political responsibility of German universities’, for the inauguration of the ‘prisoners’ university’ he organised during his American detention, he denounced in particular the idea that theory and practice must be separated. This artificial gap, largely the result of positivism, contributed to the moral decay of German universities in the first half of the 20th century. Instead, according to Hallstein, while universities must remain free of ideological and partisan battles, and while science must not be submitted to utilitarian imperatives, there is a necessary link between (academic) theory and (political) practice. On the one hand, universities are inherently democratic, as they foster exchange on a strictly egalitarian basis – scientific merit and soundness; on the other, it is part of their mission to study political issues and debates along with any other social phenomenon. This, however, requires some methodological precautions.Footnote 84

Returning to this issue in a speech for the centenary of the Paulskirche in 1948, he stressed that the apparent antithesis between science and politics was contradicted by history – here, the gathering of the Paulskirche, sometimes called the ‘Professoren Parlament’. In reality, he added, politics can be concerned with science in three unequally legitimate ways. First, political authorities can produce science. in this case, they will directly define what is true and false, what can be said and thought: It is ‘in modern terms, the last stage of the total state’, which intervenes to prescribe truth. When political power intervenes, whether in research or teaching, it is no longer a matter of science, but of propaganda. But politics can also influence science more subtly, by setting the framework of scientific work. This can be achieved by repressing or fostering the development of certain disciplines, by preventing or encouraging the circulation of ideas, books. This dimension thus refers to higher education policies as they have come to be practised in most European states. Finally, politics can be concerned with using science in order to achieve its practical objectives. In particular, this includes the training of officials, or the practical use of knowledge in the decision-making process. Science is here regarded as complementing politics. There is, therefore, no need to strictly separate the two, as concentrating on the first mode of relation only would certainly suggest; but it is necessary to be clear about how, as a politician, one seeks to mobilise science.

Conversely, politics can be an object of scientific study. In 1949, continuing his critique against positivism, he attacked the Weberian position of science ‘without presuppositions’; this he not only claimed to be impossible, but confidently asserted ‘has been abandoned’. This position is not satisfying because it rests on an artificial separation of both areas. Instead, he offered to play Kant against Weber. Accordingly, the professor (here, of law) must be allowed to take normative positions on law as far as it concerns ‘the last and highest values of civilisation’. The guarantee of scientific rigour will in this case be preserved if – and only if – ‘the immanent rules of all science’ are followed. These include sincerity, which prevents the stating of things that one does not necessarily believe; rationality, which he defined as the propensity to refuse preconceived distinctions; objectivity, which requires the giving of a complete presentation on a given position even when one disagrees with it; humanity, that is, ‘the readiness to criticise and discuss, the awareness that the ultimate task of science is not to give answers, but to ask questions so that each theory is presented with the sole meaning of contributing to that eternal discussion which is called science’. Provided these conditions are fulfilled, there is no obstacle to a scholar acknowledging the political dimension of his or her work.

Hence, Hallstein was not of the opinion that science and politics were to be strictly separated. On the contrary: he saw them as distinct but interrelated and complementary areas of human activity. But there are several, not equally legitimate, ways to connect them. In his opinion, it was acceptable and desirable that politics be improved through scientific knowledge; conversely, scientists were allowed to take political positions, not only because he saw this as unavoidable, but also because science, especially legal science, cannot turn a blind eye to politics – an observation that surely found many echoes in the context of post-Nazi Europe. Thus, a legal scholar can – and under certain circumstances must – be involved in facing the political challenges of the time. Hallstein dedicated himself to putting these insights into practice when he became President of the Commission.

Mobilising supports

With these justifications in mind, it should come as no surprise that Hallstein, once appointed as President of the Commission, took great care to present his political positions as grounded on scientific arguments, and to disclose the political implications of his scientific views. An academic involved in politics, he was able to reach audiences in both arenas during the first years of European integration. This gave him a decisive advantage over those who essentially inhabited the political field, and those who remained primarily confined to the academic debate. The intense work he deployed to promote his representation of Europe as a ‘Community of law’ indeed allowed him to build a large coalition of political, as well as academic supports.

While Spinelli and the proponents of a constitutional moment retreated into more discreet political activism after 1954, the first President of the European Commission remained very active in European academic circles during his time at the Commission and in the following years. He could rely on his own academic networks, increasingly extending from Germany throughout Europe. For instance, as early as 1951, he had supported the transformation of the Institute of Comparative Law of the University of Frankfurt, which he previously directed, into an Institute of European Economic Law.Footnote 85 During the negotiations on the EEC, he had also advocated for the creation of a European university.Footnote 86 While this project faced much opposition, he then supported the creation of the first scientific associations dedicated to the study of the EEC and of its law. When the Director of the Legal Service of the Communities, Michel Gaudet, sought to foster the creation of a German association of European legal studies, similar to that created in France, he naturally and successfully turned to Hallstein to support him.Footnote 87 This would give birth to the Wissenschaftliche Gesellschaft für Europarecht, the German member of the transnational association of associations for the study of European law (FIDE). Hallstein would eventually, in 1967, be named an honorary member of the association. Likewise, when another, interdisciplinary association for the study of European integration – the Arbeitskreis Europäische Integration – was created in Germany in 1969, he acted as its first President.Footnote 88 This sustained academic involvement provided him with many occasions to present his ideas to an academic audience, and to take part in the ongoing debate about the status of EEC law. It contributed to circulating the idea of a ‘Community of law’ that found echoes among trained lawyers, especially those familiar with the German legal tradition.

This academic activism was all the more important since the political debate was, in turn, largely conducted in academic terms. Indeed, lawyers were most active in the debate about the primacy of EEC law in the 1960s. This was not only the case in relation to Michel Gaudet and the Legal Service of the Communities. It was also true of the European Parliament, where MEPs with legal training largely dominated the Legal Commission in charge of the reports on primacy. Between 1960 and 1965, the proportion of members of the Legal Commission who had practised law ranged from 70.6% to 88.2%.Footnote 89 Strikingly, the concept of ‘Community of law’ found early users at the European Parliament among those who had long been familiar with European negotiations and institutions – and through this had long been acquainted with Hallstein and his ideas. For instance, as early as 1958, the concept of ‘Community of law’ was used in plenary session by a Dutch MEP, the former lawyer and member of the Assembly that had drafted the failed Constitution of the European Political Community, Mr van der Goes van Naters,Footnote 90 and again in 1960 by the vice-president of the European Coal and Steel Community, Mr Spierenburg, who had led the Dutch delegation to the Schuman plan negotiations.Footnote 91

In this situation, Hallstein largely used his academic credentials to push his interpretation of the concept forward.Footnote 92 In 1964, the Commission published a note on the ‘Community of law’, essentially repeating his position exposed earlier. In 1965, on the eve of the ‘empty chair crisis’, he intervened during the debate on primacy, literally quoting his 1958 Hamburg speech.Footnote 93 Tellingly, he started by praising the ‘scientific’ quality of the report drafted by Fernand Dehousse, himself a professor of international law, and directly referred to the doctrinal debates that had been taking place at the FIDE meetings. The ‘empty chair crisis’, while it cost Hallstein his position, did not fundamentally contradict this approach; it only postponed the moment when the EEC would become a fully democratic federation. Hallstein would continue to play an important political role after he left the Commission. In 1968, he was elected President of the European Movement, a position he held until 1974, and he was a Member of the Bundestag (CDU) from 1969 to 1972. This gave him a strong advantage over both Ipsen and American political scientists, whose theories remained more narrowly confined to academic readerships.

Of course, this intertwining of academic and political arguments did not automatically lead to a general acceptance of his constitutional views. Scientifically, it remained contested by those who maintained that the EEC was an international organisation. Politically, it was opposed by Gaullists and, more generally, by those defending the primacy of national constitutions. Yet, it was increasingly received in a now well-known process.Footnote 94 Most important in this process was the endorsement by the Court of the primacy and direct effect of EEC law and, eventually, of the concept of ‘Community of law’ itself. While the constitutional implications of the early jurisprudence of the Court were famously spelled out during the 1960s, it eventually directly endorsed the concept of ‘Community of law’. From 1982, it was increasingly used in the Court’s proceedings.Footnote 95 Then, it was no longer an academic construction, nor a political project: it became part of the actual jurisprudence of the EEC and thus was changed into a legal fact.

On the other hand, academic circles slowly came to endorse this concept as the autonomy of EEC law as a field of study and an academic discipline became stronger. It had the effect of legitimising professional claims to being specialists of a new kind of law, distinct from international law. Following Hallstein’s argument, since Community law was of a constitutional nature, they were able to define themselves as members of a new distinct profession – that of Community lawyers. Indeed, Hallstein’s vision became part of the teaching materials on EEC law, as its penetration into EEC law handbooks shows. While the concept of ‘Community of law’ itself was at first mostly used in Germany, Hallstein’s more general ideas about the European constitution were echoed in France as early as the 1960s.Footnote 96 After the Court used it, the process accelerated. The concept became a standard way to introduce the EEC and its law,Footnote 97 and was taught to generations of students.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have examined the constitutional imaginary attached to the concept of ‘Community of law’, as it was developed by Walter Hallstein from the 1950s. Analysing the ‘Community of law’ as a constitutional imaginary has allowed it to be explained not only in its legal dimension, but also with regard to the conception of democracy and market it carried. In contrast with the literature that has explored the struggle between ‘constitutionalists’ and ‘internationalists’ during the early years of the EEC, I have focused on the contrasts between different constitutional imaginaries, namely, political federalism, functionalism and the ‘Community of law’. The last of these provided an original model, in which the law itself, rather than popular will or economic interest, was the anonymous driving force of integration. At the same time, the law would secure the free play of the market, while promising, in a more or less distant future, the realisation of a European federal democracy. I have argued that this original imaginary offered by the ‘Community of law’ and the great mobilisation of political and academic support by Hallstein provide clarity on why it succeeded more than others.

It should be noted that, in the long run, the endorsement of this imaginary by increasing parts of European academia and legal practice had important consequences. In particular, in the debates of the time, creating and protecting a ‘Community of law’ was mostly framed as a guarantee that member states would abide by supranational rules, while supranational institutions in turn would respect the rule of law as it was protected in the national contexts. In other words, guaranteeing the rule of law at the supranational level was mostly presented as a way for states to keep the Community in check – while today, the opposite seems to be the case. Besides, this imaginary helped to produce a largely depoliticised understanding of European integration: law being the driver of integration would lead, in due course, to a more democratic organisation. Political issues were, until then, largely subordinate. Thus, in spite of its constitutional claims, Community law tended to be framed as a narrowly defined, essentially technical discipline. It was only in the late 1980s, paradoxically at the exact moment when it started to be used by the European Court of Justice and formalised by European legal academia under the label of ‘integration through law’,Footnote 98 that criticism would start to be aimed at this narrow understanding of the constitutionality of EEC law.