Antipsychotic medication and psychosocial interventions have been found to substantially improve the prospect of recovery in schizophrenia for many. However, a major impediment to this is social exclusion by the general population (Reference Kingdon, Ramon and PerkinsKingdon et al, 2006). Health promotion campaigns have had marginal impact on this (Reference Crisp, Gelder and GoddardCrisp et al, 2004) and concerns about the dangerousness of people with schizophrenia to society have, if anything, hardened (National Statistics, 2003). This is not simply caused by lack of knowledge as campaigns to promote a biological model of schizophrenia have been successful in ‘increasing the public's tendency to endorse biological causes’ (Reference Angermeyer and MatschingerAngermeyer & Matschinger, 2005). Paradoxically, however, such campaigns may have the effect of increasing social distancing by the general population from people with schizophrenia (Reference Angermeyer and MatschingerAngermeyer & Matschinger, 2005).

An alternative approach is to associate schizophrenia with evidence from psychosocial research which has found that trauma (Reference Read, Agar and ArgyleRead et al, 2003), hallucinogenic drug use (Reference HallHall, 2006) and stress-sensitivity (Reference Myin-Germeys, Delespaul and VanMyin-Germeys et al, 2005) are significant risk factors. Approaches using cognitive therapy have found such associations valuable in directing formulation-based therapeutic interventions (Reference Kingdon and TurkingtonKingdon & Turkington, 2005). Using such associations has also proved meaningful and more acceptable to service users and carers who dislike the very term ‘schizophrenia’ (Reference Kingdon, Gibson and KinoshitaKingdon et al, 2008) and are proposing alternatives (Reference TeskeyTeskey, 2006). Renaming schizophrenia is controversial and concern has been expressed that it would not address the core problem that is ‘the public's ignorance and fear’ (Reference Lieberman and FirstLieberman & First, 2007). Nevertheless, attention to naming cannot be dismissed - the public relations industry devotes substantial resources to the importance of presentation of services and products (Reference Kingdon, Kinoshita and NaeemKingdon et al, 2007).

Describing more precisely Bleuler's ‘group of schizophrenias’ (Reference BleulerBleuler, 1911) would allow research, training and terminology to be tailored to each of them. Kraepelin (Reference Kraepelin1919) made an attempt to do this - he famously delineated manic depressive insanity from dementia praecox but also differentiated it from paranoid states where behaviour was only abnormal in so far as it was the outcome of delusions. He also distinguished dementia praecox from hysteria but then reclaimed those in whom hallucinations were persistent as he believed this gave ‘decisive evidence for dementia praecox’. Schneider's emphasis on defining schizophrenia based on the nature of symptoms rather than their content (Reference Schneider and HamiltonSchneider, 1959) initially led to a tighter definition of schizophrenia. However, first-rank symptoms have proved to be less specific than initially hoped (Reference Carpenter, Strauss and MulehCarpenter et al, 1973) - for example, they have been demonstrated to occur in association with trauma (Reference Ross and JoshiRoss & Joshi, 1992) and in individuals whose initial psychotic experience was directly from the effects of stimulant and hallucinogenic drugs. The inclusion of this group under the schizophrenia rubric became of increasing importance from the 1960s onwards, leading to a substantial broadening of this diagnostic category.

Thus, a combination of clinical observation, psychosocial research and historical precedent has contributed to the delineation of four possible subgroups of schizophrenia. Kraepelin's dementia praecox has survived in classification systems as disorganised schizophrenia (DSM-IV), nuclear schizophrenia and hebephrenia. This has been refined further as the ‘deficit state’ (Reference Kirkpatrick, Buchanan and RossKirkpatrick et al, 2001), renamed for use with patients as ‘stress-sensitivity psychosis’. Kraepelin's inclusion of ‘hallucinating hysteria’ in dementia praecox has been reversed and, reinforced by the evidence of childhood trauma as a factor in some - particularly female - patients, has become ‘traumatic psychosis’. Paranoid states, variously described as late-onset paranoia, paranoid schizophrenia and delusional disorder - where systematised delusions develop in mature individuals experiencing stressful circumstances - has led to a revival of Wernicke's term ‘anxiety psychosis’ (Reference HealyHealy, 2002). Finally, ‘drug-related psychosis’ which did not exist when ‘the group of schizophrenia's’ was originally described, is recognised in its own right.

These terms have been found to be acceptable to both patients and clinical staff (Reference Kingdon, Gibson and KinoshitaKingdon et al, 2008) and this study was developed to explore whether they might be less stigmatising than the term schizophrenia itself. Medical students were recruited as being readily accessible to the researchers and able to readily comprehend the requirements of the study. Another reason was that doctors have a seminal role in combating stigmatisation but their attitudes to psychiatry (Reference Rajagopal, Rehill and GodfreyRajagopal et al, 2004) and people with mental health problems (Reference ByrneByrne, 1999) remain quite negative, which may affect their response to patients’ physical and psychological care (Reference ThornicroftThornicroft, 2006). We sought to test the hypothesis that the use of terminology based on psychosocial subgroups would lead to differences between these groups and schizophrenia, and that negative attitudes in respondents would be reduced.

Method

Medical students from the University of Southampton attending lectures about schizophrenia in their 2nd and 3rd years in 2005 were asked to complete the section of a questionnaire relating to schizophrenia which had been used to monitor the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ ‘Every Family in the Land’ campaign (Reference Crisp, Gelder and RixCrisp et al, 2000). The questionnaire asked the respondent to ‘think of a person with schizophrenia’ and then rate them on a five-point scale on being dangerous to others: unpredictable; hard to talk to; have only themselves to blame; would improve if given treatment; feel the way we all do at times; will eventually recover fully and could pull themselves together if they wanted to. (Formal psychometric properties of the scale have not been published. Its validity could be said to have been established through the consensus process used in its development by the campaign.)

The students were also given brief descriptions of the psychosocial subgroups (Appendix) and asked to rate the individual groups against the same characteristics. Respondents were regarded as having a ‘negative opinion’ if they endorsed either of the two points on the five-point scale on the ‘negative’ side of its mid-point.

Data measured on a continuous scale were presented with mean, standard deviation and 95% confidence intervals. Normally distributed continuous data were analysed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t-tests. Where data was skewed and non-normally distributed, non-parametric techniques (Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney U-test) were applied. Categorical data were presented in percentages and association between categorical variables was assessed with the use of chi-squared test and where expected frequency were below five then the Fisher's exact test was used. Statistical significant was assessed if P<0.05 and all analysis was conducted with the use of a statistical software SPSS version 14 for Windows.

Results

There were 241 medical students (66%) that took part in the survey from a possible 365 (the total number of 2nd and 3rd year students who could have attended the lectures); 16 questionnaires had missing data (in nine cases only the questionnaire on schizophrenia was completed). There were 160 females (66.4%); 79 students (32.8%) were less than 20 years old, 153 were between 20 and 30 years old (63.5%), and 8 were between 30 and 40 years old (3.3%); 178 were White (73.9%); 58 reported (24.1%) that they had known someone with schizophrenia prior to the survey. In comparison with previous studies using the same instrument in the general population (Reference Crisp, Gelder and GoddardCrisp et al, 2004) and psychiatrists (Reference Kingdon, Sharma and HartKingdon et al, 2004), the students’ attitudes were intermediate (Table 1).

Table 1. Respondents holding negative opinions about schizophrenia

| Opinion | General population (%) | Medical students (%) | Psychiatrists (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Danger to others | 71.3 | 24.5 | 5.8 |

| Unpredictable | 77.3 | 64.2 | 39.1 |

| Hard to talk to | 58.4 | 34.2 | 35.4 |

| Feel different | 57.9 | 29.3 | 30.5 |

| Themselves to blame | 7.6 | 3.4 | 0.7 |

| Cannot pull self together | 8.1 | 12.1 | 2.5 |

| Not improve with treatment | 15.2 | 4.3 | 1.8 |

| Never recover | 50.8 | 34.9 | 22.1 |

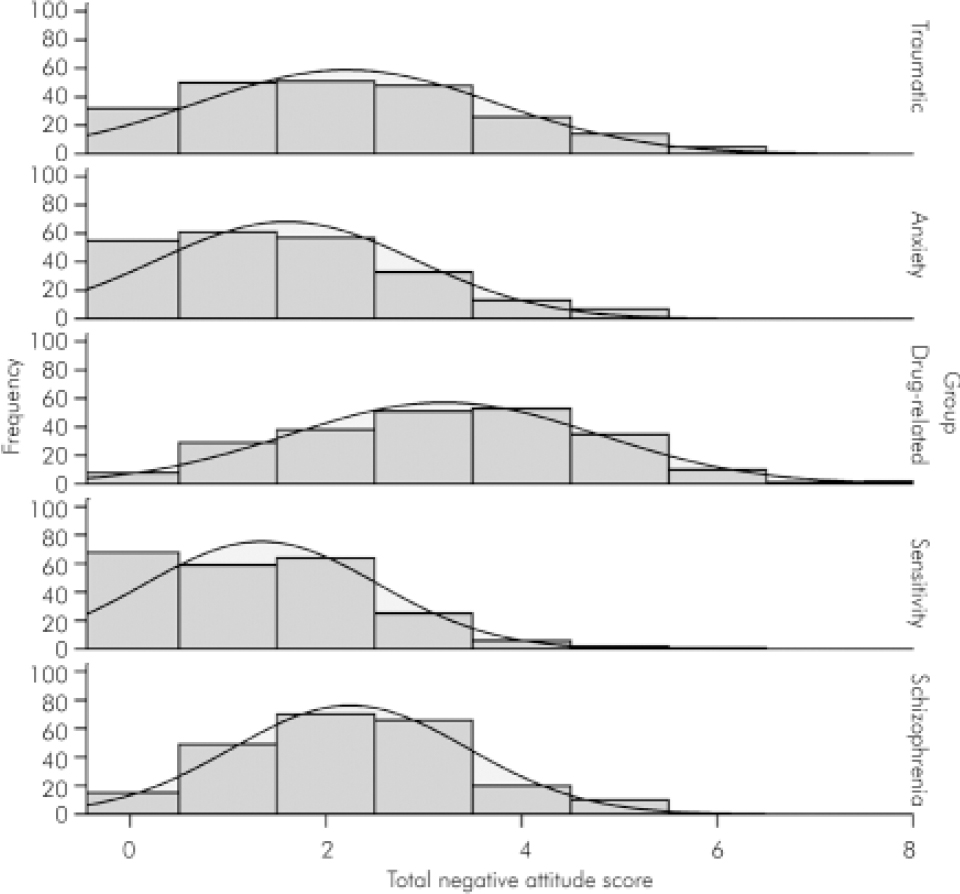

The distribution of student attitudes towards schizophrenia and the subgroups markedly differed (Fig. 1). For schizophrenia, the distribution was normal. The drug-related group was similar but flattened and shifted towards higher values, whereas the other groups had a skewed distribution towards a lack of negative attitudes.

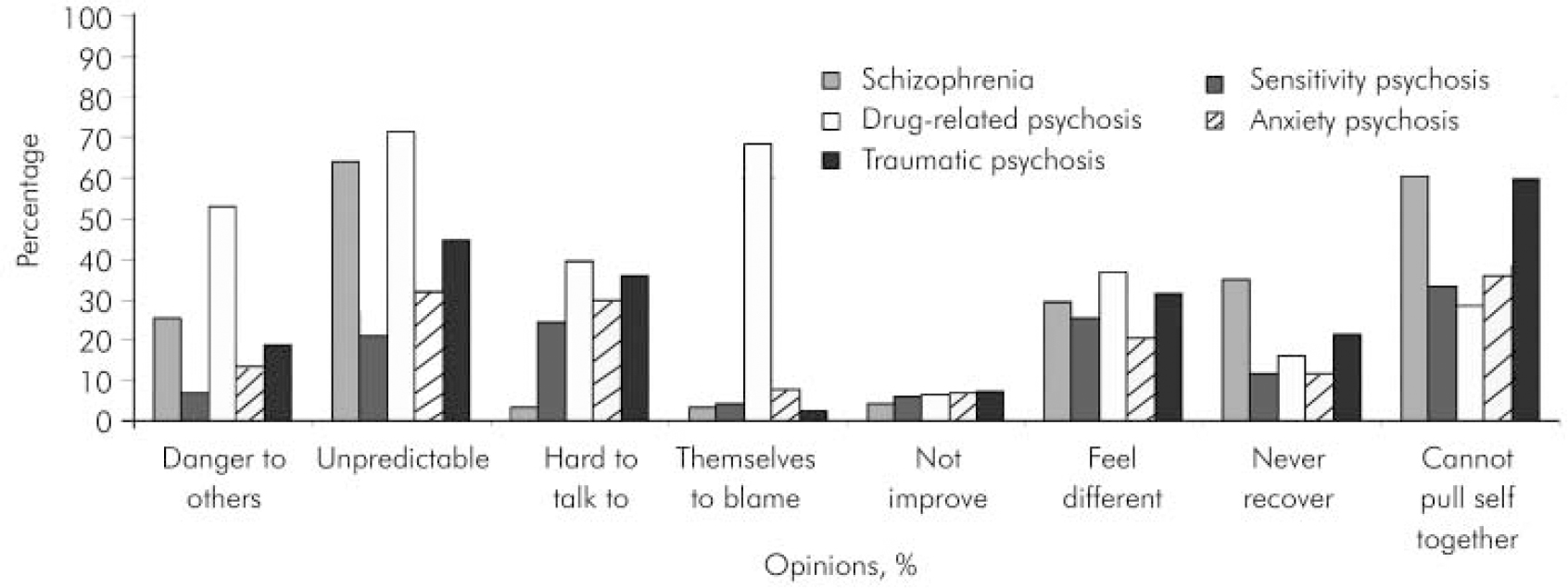

Gender, ethnic group and age did not affect negative attitudes. The total negative attitude score was significantly greater towards schizophrenia than the subgroups overall (P<0.023). These also differentiated between schizophrenia and the individual subgroups with the exception of the trauma group. The sensitivity (P<0.001) and anxiety psychosis (P<0.001) subgroups were viewed more favourably, but the drug-related group was perceived more negatively (P<0.001). There were also significant differences in scores between schizophrenia and the subgroups on individual items (Table 2): 53% of respondents rated individuals with drug-induced psychosis as dangerous to others, which is significantly higher than for the other groups (Fig. 2). Furthermore, 35% of the respondents thought that individuals with schizophrenia would never recover, which was higher than for any of the subgroups.

Table 2. Negative attitudes to schizophrenia and subgroups

| Subgroups, % (95% CI) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion | Schizophrenia | Sensitivity psychosis | Drug psychosis | Anxiety psychosis | Traumatic psychosis | ||||

| Danger to others | 25.4 (20.2–31.4) | 7.0 (4.4–11.1) | 53.0 (46.6–59.4) | 13.5 (9.7–18.6) | 19.0 (14.5–24.6) | ||||

| Unpredictable | 64.2 (57.8–70.1) | 21.1 (16.3–26.9) | 71.6 (65.5–77.1) | 31.9 (26.2–38.2) | 44.6 (38.3–51.0) | ||||

| Hard to talk to | 3.4 (1.8–6.7) | 24.4 (19.3–30.5) | 39.5 (33.3–45.9) | 30.0 (24.4–36.2) | 36.0 (30.0–42.4) | ||||

| Themselves to blame | 3.4 (1.8–6.7) | 4.4 (2.4–7.9) | 68.3 (62.0–74.9) | 7.9 (5.0–12.1) | 2.6 (1.2–5.6) | ||||

| Not improve with treatment | 4.3 (2.4–7.8) | 6.2 (3.7–10.9) | 6.5 (4.0–10.5) | 7.0 (4.3–11.0) | 7.4 (4.6–11.5) | ||||

| Feel different | 29.3 (23.8–35.5) | 25.5 (20.3–31.6) | 37.0 (31.0–43.4) | 20.5 (15.8–26.2) | 31.7 (26.1–38.0) | ||||

| Never recover | 34.9 (29.1–41.2) | 11.9 (8.3–9.1) | 16.1 (11.9–21.4) | 11.8 (8.2–16.6) | 21.6 (16.8–27.4) | ||||

| Cannot pull self together | 60.6 (54.2–66.7) | 33.5 (27.7–39.8) | 28.7 (23.2–34.8) | 35.8 (29.9–42.2) | 59.7 (53.3–65.9) | ||||

Fig. 1. Distribution of negative attitudes.

Conclusions

Use of psychosocial categories and terminology significantly reduced negative perceptions of medical students about people who comprise the group of schizophrenias. Most students exhibited some negative views towards schizophrenia. This was less towards the subgroups although a residual level of negative attitudes remained. The exception was the drug-related group where most held at least some negative views. There was concern about dangerousness and unpredictability with individuals who had misused hallucinogenic drugs and, as this is a major risk factor for aggression where it is associated with schizophrenia (Reference Walsh, Buchanan and FahyWalsh et al, 2002), this may to some extent be justified. Overall, attitudes were substantially improved across most of the domains and in particular towards the possibility of recovery, even for the drug-related group. Evidence supporting the risk factors used to define the groups is substantial but there has been very limited research into differentiation between these individual groups in relation to prognosis, etc. There also needs to be debate about whether these are the most appropriate terms to use. For example, in response to a formal request from a carer organisation, the Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology recently adopted the term ‘integration disorder’ for schizophrenia (Reference SatoSato, 2006). Changing names of conditions has limitations in reducing stigma but there are few advocates, especially among patients themselves, for changing back from, for instance cerebral palsy, learning disability and bipolar disorder to spastic, retard or manic depressive.

Fig. 2. Negative opinions of medical students to schizophrenia and psychosocial subgroups.

The study does have significant limitations. As an ‘intervention’ to change attitudes, a randomised controlled approach would be more rigorous: the terms were not presented in a randomised way and this might have influenced the outcome. Also, as with many such health promotion studies, this investigation has been into declared attitudes and further work is needed to see if this is reflected in behaviour change and in the wider population where attitudes are more negative (Reference Crisp, Gelder and GoddardCrisp, 2004) than in medical students.

Appendix

The person would typically describe their experience in the following way.

Drug-related psychosis

‘My problems started after I had taken speed (amphetamines), LSD, cocaine or a lot of cannabis. After that I started to get some problems and received treatment. The problems continued or came back after settling after the first time this happened. Eventually these problems were happening even when I did not take drugs.’

Anxiety psychosis

‘When I first received treatment for my problems, I had been having some hassle, stress, and so on, but had become convinced that there was a particular reason behind it all. Unfortunately, other people did not agree with me.’

Traumatic psychosis

‘My problems go back quite a way - maybe even as far as my childhood or soon after - and seem to have something to do with some very unpleasant experiences that I had. Now I seem to get unpleasant voices and maybe also visions - sometimes to do with these experiences.’

Stress-sensitivity psychosis

‘My problems began over a period of a few months or even a year or two. I became quite sensitive to stress which gradually led to interference with what I was doing. This led to increasing confusion and worry and eventually I received treatment. It was or has been difficult to get going again properly - however hard I try.’

Declaration of interest

None. National Health Service research and development support funding.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.