Politicians need to cultivate public support to win elections. To do so, they invest a lot of energy into identifying the best ways to communicate with the public. Among the most important ways they do this is through how they present themselves as individuals (Fenno Reference Fenno1978). While elected officials try to connect to their constituents by listening to their concerns and explaining how they serve the public, much of their energy is centered on simply being the type of person that people want to support. In the words of Fenno (Reference Fenno1978, 55), “Members of Congress go home to present themselves ‘as a person’—and to win the accolade, ‘He’s a good man,’ ‘She’s a good woman.’” Campaign events are scheduled to boost the candidate’s image. Politicians post pictures of their family on social media and describe their upbringing on their website.

Elected officials want constituents to form favorable impressions of them as people, to perceive them as likeable and relatable. Does getting to know the personal side of a politician help to boost ratings—even in a time when attitudes seem strongly structured by partisanship? I consider whether sharing nonpolitical autobiographical details leads people to provide warmer ratings of elected officials. To do so, I use an experimental design inspired by the celebrity entertainment magazine, Us Weekly. Each issue includes a column titled, “25 Things You Don’t Know About Me,” in which celebrities—and sometimes politicians—share interesting details about themselves. In a design inspired by this column, experimental participants were given a short list of personal, nonpartisan details about one of two well-known elected officials (Senator Ted Cruz or Senator Bernie Sanders) and then were asked about their impressions of the senator.

I find that reading these types of personalizing details contributes to warmer evaluations of politicians. When elected officials share details about their personal quirks and background, they shift how people see them as individuals. It suggests that the apolitical personalizing details people encounter in soft news are not interpreted through the same schema as traditional news. Rather than perceiving elected officials as only politicians, they also see them as people. Moreover, these personalizing details do not seem to be interpreted in particularly partisan ways. Exposure to personalizing information leads to warmer evaluations among members of both parties but with the greatest boost in enthusiasm among those who do not share the same partisan leanings as the politician about whom they read. In contrast to the polarized views that can emerge from partisan motivated reasoning (Taber and Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge2006), these personal details lead to evaluations of politicians who are less polarized along party lines. Even as campaigns seem increasingly structured by partisanship (Wattenberg Reference Wattenberg2016), a candidate-centered campaign style offers elected officials a way to build cross-party support. By sharing some of themselves with the public, elected officials invite voters to think of them as more than simply another politician.

WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT PERSONALIZING COVERAGE

When politicians share autobiographical details, they invite the public to know not only their partisanship and their platform but also what they are like as a person. The presumption is that these personal appeals will win over voters, making the candidate seem more likeable and appealing. However, evidence is mixed about whether these attempts are successful. Consider the case of campaign ads. Candidates often use positive ads to highlight their personal traits (Johnston and Kaid Reference Johnston and Kaid2002). Some studies find that these positive ads can build candidate support and contribute to warmer impressions of unknown politicians (Kahn and Geer Reference Kahn and Geer1994; Malloy and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference Malloy and Pearson-Merkowitz2016), but others find minimal evidence that these ads are persuasive (Coppock, Hill, and Vavreck Reference Coppock, Hill and Vavreck2020). People also learn about the personal lives of politicians on soft news, such as when a presidential candidate shares anecdotes in a late-night talk show. However, previous studies suggest that this type of soft news coverage may not benefit politicians, failing to shift public impressions (Baum Reference Baum2005; Morris Reference Morris2009) or even contributing to negativity toward politicians (Baum Reference Baum2005; Baumgartner and Morris Reference Baumgartner and Morris2006; Morris Reference Morris2009).

One limitation of these previous studies is that they provide only indirect evidence of whether it is valuable for politicians to share personal details. Campaign ads can provide biographical details, but they do so alongside other details such as emotional cues, which makes it difficult to isolate the specific rewards of sharing personal anecdotes. Likewise, many studies of soft news appearances draw on observational data, considering whether soft news consumers view politicians differently. However, this also is an imprecise test of the specific effectiveness of sharing personal anecdotes. To better isolate whether politicians gain support by sharing details about themselves, I turn to an experimental design. I present participants with a set of apolitical personal details about one of two politicians to see whether doing so shifts how they evaluated these elected officials.

THE EFFECTS OF POLITICAL CONTENT IN US WEEKLY

I design this experiment to mimic one real-world example of how politicians have shared personal details with the public: a column in Us Weekly. Us Weekly is a celebrity entertainment magazine, with pop culture news and interviews as well as other nonpolitical fare such as recipes and movie reviews. Each issue concludes with the column titled, “25 Things You Don’t Know About Me,” in which people in the public eye share a list of details about themselves. The entries are short and personalized, mentioning topics such as favorite foods, pets, hobbies, and childhood anecdotes. Most of the participants in the column are actors, comedians, reality-television stars, athletes, and musicians. Yet, over the years, a number of politicians have contributed their own lists of “25 Things.” Donald Trump provided a list in 2010 while promoting The Celebrity Apprentice, sharing his love of Scotland and how he only eats the pizza toppings and not the dough. Barack Obama named some of the artists that populate his iPod playlist in his 2012 list. In 2015, Rand Paul shared his love of root beer floats and his composting hobby. In 2016, Ted Cruz offered that he hates avocados and made it to level 350 in the game of Candy Crush. Hillary Clinton made the cover of the magazine in 2016 with her list, in which she shared her love of Adele, the Beatles, and goldfish crackers. Joe Biden also contributed a list in 2016, in which he shared his dream of being an architect and his obsession with Ray-Ban aviator sunglasses.

I propose that people who read personal anecdotes like those shared in Us Weekly’s “25 Things” column will offer warmer evaluations of the politicians profiled. At the simplest level, the column presents readers with novel, entertaining information that can capture their interest. To the degree to which these personal details paint a positive view of an elected official, this can contribute to warmer evaluations, making favorable considerations more accessible in memory. I also expect that this type of soft news is likely to be viewed differently from other types of political details. Baum (Reference Baum2003) argues that information from entertainment outlets is processed differently from mainstream news. By focusing on the nonpolitical details from the personal life of politicians, soft news may humanize elected officials—inviting news consumers to see elected officials as more than simply stereotypical politicians.

As things go, people typically hold negative impressions of politicians as a group (Citrin and Stoker Reference Citrin and Stoker2018). When an individual is described as a “politician,” people tend to interpret information through existing schema about negative attributes of politicians. However, if the same individual is described in a way that invites people to think of him or her as a “person” rather than a “politician,” they offer warmer evaluations (Fiske Reference Fiske, Clark and Fiske1982). I expect that a similar mechanism is at work when people read this type of soft news coverage. When given a list of personal rather than political attributes, the participants’ encoding of this soft news coverage may not be interpreted through the usual negative lens of a politician schema. People encode new information differently depending on how they connect that information to existing details held in their long-term memory (Steenbergen and Lodge Reference Steenbergen, Lodge, MacKuen and Rabinowitz2003). I expect that when politicians share apolitical personal details about themselves, people will focus attention on them as individuals rather than as exemplars of a politician stereotype. This should contribute to warmer impressions, given that people are more likely to perceive individuals more favorably than members of a group (Sears Reference Sears1983).

Given that these personal details likely are processed differently from other types of political information, I also expect that they will not be seen in particularly partisan ways. In an era of party polarization, impressions of politicians often are deeply split across partisan lines. People typically approve of those politicians who share their party allegiance, while criticizing those on the other side (Donovan et al. Reference Donovan, Kellstedt, Key and Lebo2020). This is believed to be the product of partisan motivated reasoning, where people rely on prior partisan attitudes to guide the interpretation and evaluation of new information (Taber and Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge2006). People are more willing to accept information that is consistent with their priors and are critical of information that challenges their views. As a result, even balanced information can lead to evaluations polarized along party lines.

However, even if partisan motivated reasoning is common, people do not use it in all situations (Kunda Reference Kunda1990; Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge, Taber, Lupia, McCubbins and Popkin2000). The influence of partisan motives is conditional to the task at hand (Groenendyk and Krupnikov Reference Groenendyk and Krupnikov2021). Soft news may present information in a way that does not necessarily activate partisan reasoning. In the case of personalizing details, the content is not particularly political in nature. Politicians are not describing their partisan views or policy priorities; instead, they are sharing their hobbies, interests, and personal anecdotes. This type of soft news coverage invites the audience to focus on the personal rather than the political, which may fail to activate the partisan biases that people otherwise would bring to how they interpret the news. If partisan motivated reasoning is not engaged, then this type of soft news coverage may reduce rather than increase partisan differences in politician affect. I expect that personalizing information from soft news will boost the favorability of politicians among both copartisans and those who favor the opposing party.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

I explore the effects of these types of personalizing details on affect toward elected officials using a survey experiment of 994 participants who completed a module of the 2020 Cooperative Election Study (Wolak Reference Wolak2023). In the experiment, I manipulated the identity of the politician as well as the presence of personal details. People were randomly assigned to provide an evaluation of either Senator Bernie Sanders or Senator Ted Cruz. Rather than creating profiles of hypothetical officeholders, I focused on prominent politicians currently serving in government. I did so because people evaluate familiar politicians differently than unfamiliar ones. People are inclined toward positive first impressions of political unknowns, and new information matters more when people are starting with a blank slate (Holbrook et al. Reference Holbrook, Krosnick, Visser, Gardner and Cacioppo2001). It should be easier to create positive perceptions about invented hypothetical candidates as opposed to trying to shift prior impressions of politicians shaped by years of news coverage. Rather than looking at how people weigh personal details in forming an initial impression, I explore how they compare novel personal details against the accumulated biases and impressions they hold in memory. This represents a tough test of my hypothesis that apolitical personal details can shift people’s perceptions of politicians.

Both senators are prominent politicians who are well known beyond their state constituencies, given their time in the US Senate and their previous bids for the presidency. Almost all Americans are familiar with their names. Surveys from the time of the study in the fall of 2020 showed that about 95% of Americans had heard of Bernie Sanders and 90% had heard of Ted Cruz. Compared to people’s recognition of other politicians, these surveys revealed Cruz to be the best-known Republican senator and Sanders to be the best recognized among senators on the Left. In addition to their political prominence, both senators are ideologically distinctive. Compared to other Republicans, Cruz is particularly conservative. Based on DW-Nominate scores from the 116th Congress, his voting record makes him more conservative than 98% of other senators. At the other end of the political spectrum, Sanders stands out as distinctly liberal. In the same period, his voting history places him to the far left, more liberal than 97% of other senators (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Poole, Rosenthal, Boche, Rudkin and Sonnet2021). Given the deepening partisan and ideological divides within the American electorate, Cruz and Sanders are likely perceived by many as polarizing politicians. As such, there is reason to believe that many hold strong prior opinions about the political views of both senators.

In the control condition, participants were told only about the ideology of the senator and the state that he represents, noting either that “Ted Cruz is a conservative lawmaker who represents the state of Texas in the US Senate” or “Bernie Sanders is a liberal lawmaker who represents the state of Vermont in the US Senate.” In the treatment conditions, participants were given the same introductory text as in the control condition followed by the sentence: “Here are five things you might not know about the senator.” In the case of Ted Cruz, I selected five statements that Cruz himself provided to Us Weekly when he participated in the magazine’s “25 Things You Don’t Know About Me” column on March 16, 2016. The selected items are personal, speaking to Cruz’s childhood, interests, and day-to-day life. The type of information shared with readers is similar to the details that a politician might share in an interview on an entertainment program or in a post on social media. The following five statements were presented in random order:

-

• I was once suspended in high school for skipping class to play foosball.

-

• As a kid, I used to go bull-frogging on the lake behind our house.

-

• My favorite movie is The Princess Bride. I can quote every line.

-

• To my wife’s great annoyance, my kids both love playing Plants vs. Zombies with Daddy on his iPhone.

-

• When I am away from the family, in Washington, DC, my dinner is a can of soup. I have dozens in the pantry.

For Bernie Sanders, I collected a list of five similar personal details about the senator from news articles and interviews. Items were selected to be complementary to the biographical details about Senator Cruz, reflecting what he liked as a kid, his favorite media programs, and details about his family. I used the same first-person presentation as found in the Us Weekly column. The details about Senator Sanders included the following:

-

• I like disco music. I like ABBA. We played some ABBA at my wedding.

-

• When I was a kid, I really liked attending Boy Scout camp in upstate New York.

-

• Modern Family is my favorite guilty-pleasure TV show.

-

• My idea of the perfect day off is being at home in Vermont with the grandkids.

-

• I proposed to my wife in the parking lot of a Friendly’s restaurant.

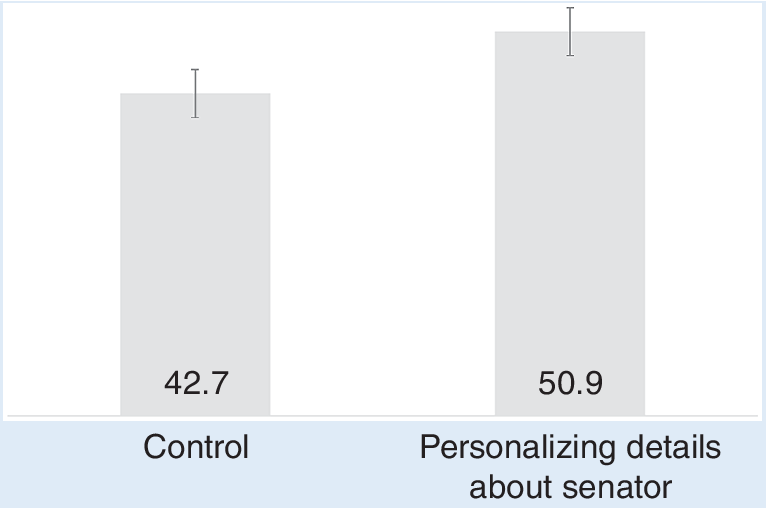

After reading the blurb, participants were asked to rate the senator on a feeling thermometer. I find that those who read the personal details about the senator report warmer feelings toward the politician than those in the control condition. In a two-way analysis of variance, I find a significant main effect associated with the treatment (F(1,990)=12.99; p<0.01). As shown in figure 1, those participants who were given personal details rated the senator 8 points more warmly than those in the control condition on the 0-to-100 scale. If the experiment had focused on unknown hypothetical politicians, it might not be especially surprising to find that people consider positive personalizing details in forming their impressions. Yet, this study considered two familiar and arguably polarizing figures in Senator Ted Cruz and Senator Bernie Sanders. Even in a case in which many people likely hold strong prior views about the senators, I find that sharing personalizing details helps lawmakers to win warmer ratings from the public. These results support Fenno’s (Reference Fenno1978) arguments about the importance of impression management in building public support.

Figure 1 Effect of Personalizing Treatment on Feeling-Thermometer Ratings of the Senators

One limitation of using accurate information about actual politicians is that the content of the two treatments is only similar rather than identical. In the supplemental online appendix, I show that although the treatments do not include identical information, their effects on the feeling-thermometer ratings were not statistically distinguishable. The treatment had statistically similar effects on evaluations of Cruz and Sanders (F=0.80; p<0.37) but with a difference in intercept because Sanders drew warmer evaluations, on average, than Cruz within this sample (F=27.97; p<0.00). In the supplemental online appendix, I also demonstrate further evidence of treatment effects by showing that these personalizing details affect the traits that people associate with the two senators. Those participants in the treatment condition perceived the senator as more likeable, more trustworthy, and more willing to make compromises than those in the control condition. However, the treatments did not shift perceptions that the politician understands the problems faced by average Americans.

I have argued that these personal details can shift people’s ratings of politicians in part because they are less likely to be interpreted through the lens of partisan motivated reasoning. I explored this possibility by considering heterogeneous treatment effects. If information about political candidates is processed in partisan ways, then those who share the same party affiliation as the politician should read these details more favorably than those who hold opposing political leanings. Those from the opposing side should resist positive information and instead look for reasons to criticize the politician among those shared personal details. If people evaluate the treatment through the lens of partisan motivated reasoning, the difference in ratings between copartisans and those who do not share the same partisanship should increase after exposure to the treatment (Taber and Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge2006).

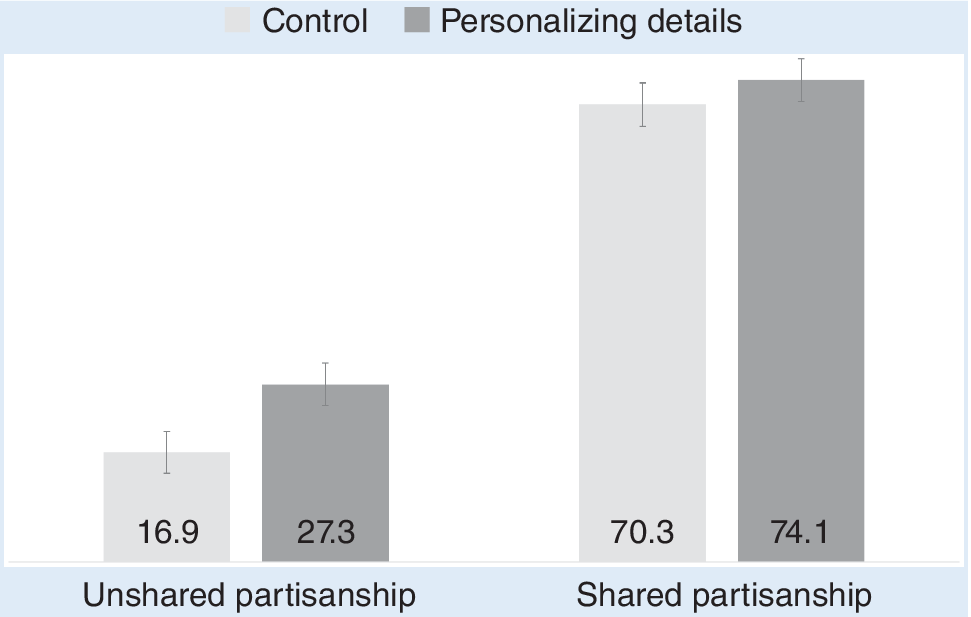

However, I fail to find evidence of such a pattern in these data. Figure 2 shows the effects of the personalizing treatment for those who share the same party leanings as the politician they had read about versus those who do not.Footnote 1 I find that personalizing details about politicians is associated with warmer affect among members of both parties, but particularly among those who do not share the same partisan leanings as the politician about whom they read. This is consistent with the expectation that apolitical personal details are interpreted differently from other politicized details. Among those who share the same partisan leanings as the senator, the treatment boosts the feeling-thermometer ratings by approximately 4 points, with a marginal effect of the treatment that falls short of statistical significance (p<0.11). However, among those who do not share the same partisan leanings as the senator, the treatment has a significantly greater impact, increasing the feeling-thermometer ratings by slightly more than 10 points.Footnote 2

Figure 2 Effect of Personalizing Treatment on Senator Ratings, by Shared Partisanship

If people were engaged in partisan motivated reasoning, I would expect to see the opposite pattern: greater receptivity to the treatment among copartisans and greater resistance to the treatment among opposing partisans. It is interesting that I find greater effects among out-partisans than among copartisans. It may be that partisans already favor copartisan politicians and do not update as much in the face of new information, whereas personalizing information offers opposing partisans new apolitical reasons to like the politician.

Although this test of heterogeneous treatment effects does not offer conclusive evidence that participants were not engaged in partisan motivated reasoning, these findings suggest that personalizing details are not interpreted in particularly partisan ways. When participants are given details that make them think about the politician as a person, the gap between partisan evaluations narrows rather than expands. In the control condition, ratings of the senators are polarized along partisan lines, with a 54-point gap between the ratings of copartisans and opposing partisans. This gap narrows to 47 points when participants read the information shared in the treatment. Although the effects of partisan priors on political impressions are strong, personalizing details about politicians undercut the partisan divides. This type of soft news coverage can depolarize the public’s partisan evaluations of elected officials. This can happen across party lines because I fail to find evidence that this relationship differs between the two senators. The three-way interaction of shared partisanship, treatment, and the senator that participants read about is not statistically significant.

…personalizing details about politicians undercut the partisan divides. This type of soft news coverage can depolarize the public’s partisan evaluations of elected officials.

DISCUSSION

A few caveats about this study should be acknowledged. I find that the effects of personalizing details are not substantial in magnitude. Although they boost favorability among out-partisans, average ratings remain negative. In practice, personalizing details likely matter mostly at the margins—that is, influencing some independents or reinforcing an incumbent’s approval rating rather than deciding election outcomes. It also is important to acknowledge that this study cannot determine how enduring these effects might be in practice. Participants may remember these personalizing details because they are novel and interesting, but these small effects may diminish outside of the experimental setting when they encounter other information about the politicians. That said, it is useful to note that these types of personalizing details can shift ratings of even well-known and polarizing politicians. For those politicians who are less well known, these personal details may have a greater effect.

CONCLUSIONS

At one time, many Americans stated that they vote the person, not the party (Kessel Reference Kessel1984). However, in recent years, such candidate-centric preferences seem to be a thing of the past. When asked what they think of the candidates, people increasingly focus on partisan and policy considerations rather than the candidates’ personal attributes (Wattenberg Reference Wattenberg2016). Nevertheless, although campaigns are less candidate centered than they once were, these results show that candidates continue to benefit from cultivating their image to boost their personal vote. When politicians share personal anecdotes about themselves, they not only can boost their image among those who are loyal to the party; they also can temper the negativity felt among those in the opposing party. This is useful to incumbents who are interested in building a coalition of supporters for reelection, which confirms Fenno’s (Reference Fenno1978) argument about the importance of home style. The results suggest one way to mitigate polarized party affect in the electorate. Although people often see the political world through the lens of partisanship, not all information invites partisan thinking to the same degree. For those interested in undercutting the power of partisanship in politics, returning to a candidate-centered campaign style might be one way to do so.

When politicians share personal anecdotes about themselves, they not only can boost their image among those who are loyal to the party, they also can temper the negativity felt among those in the opposing party.

For those interested in undercutting the power of partisanship in politics, returning to a candidate-centered campaign style might be one way to do so.

The politicians in Fenno’s (Reference Fenno1978) study cultivated a positive self-presentation by attending events in their district and interacting with their constituents. Today, elected officials can draw on soft news outlets and social media to share details about themselves with the electorate. This study explains why politicians are willing to share details about their personal lives on social media, in talk-show interviews, and in tabloid columns like these. When politicians can control the messages shared with the electorate, they often choose to provide personal details about themselves.

These findings also suggest an upside for the tabloidization of political news. While some scholars laud soft news for its potential to engage inattentive citizens in politics (Baum Reference Baum2003), others are concerned about its damaging effects on trust and confidence in elected officials (Baumgartner and Morris Reference Baumgartner and Morris2006; Morris Reference Morris2009). This research demonstrates the potential of soft news coverage to promote positive affect toward elected officials. While the content of soft news may not always be as rich in substantive detail as hard news (Prior Reference Prior2003), the types of positive personal details that readers glean from this format may be less polarizing than the typical partisan content of hard news.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Eric Gonzalez Juenke and Jana Morgan for their helpful comments and suggestions.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/77KLLV.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096523000331.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.