Majority leaders of the contemporary Congress preside over parties that are more cohesive than at any point in the modern era.Footnote 1 Leaders take a much more central role in the legislative process:Footnote 2 bypassing committees,Footnote 3 directly negotiating policy,Footnote 4 setting the agenda,Footnote 5 and managing floor debate.Footnote 6 But what do these remarkable shifts in legislative process and partisanship mean for the majority party’s influence over public policy?

Despite a burgeoning literature on party polarization in Congress,Footnote 7 scholars have not investigated the impact of increased partisanship on lawmaking. Do today’s majority parties in Congress succeed in enacting their legislative agendas to a greater extent than the less cohesive parties of earlier eras? Scholars have not tracked congressional majority parties’ records of policy success and failure over time nor examined whether today’s more cohesive parties are more efficacious at enacting their legislative priorities than those of earlier eras.

In this paper, we make two contributions. First, we take stock of congressional majority parties’ abilities to pass partisan laws since the 1970s. We examine whether legislation is more often passed along party lines in the contemporary Congress and whether majority parties have grown more self-sufficient in passing legislation without support from members of the minority party. Second, we examine whether majority parties are more successful at enacting their legislative agendas. To do so, we create a unique dataset that identifies the major legislative priorities of each congressional majority party from 1985–2016 and assess whether and how often these majorities accomplished their legislative goals.

Altogether, we find that congressional majority parties’ lawmaking capacities have not improved. Lawmaking in recent congresses is about as bipartisan as it was in the 1970s, and congressional majority parties today are no better at enacting their legislative priorities than they were in the 1980s. Contemporary majority parties frequently fail in legislating on their agenda items. When they succeed, majority parties rarely enact laws via party-line votes or by rolling the minority party. Rather they usually win on policy by coopting minority party support, including one or more of the minority party’s top leaders. These patterns have remained largely unchanged over recent decades. Despite their increased cohesion, today’s strong congressional parties are still constrained by the veto points, super-majoritarian requirements, and electoral incentives created by the U.S. constitutional structure,Footnote 8 as well as by the counterbalancing strength developed among minority parties.Footnote 9

Despite the hopes of party government theorists of earlier eras,Footnote 10 today’s organizationally strong and internally cohesive congressional parties are not better able to direct policy or bear collective accountability for policy outcomes. Although contemporary parties have greatly enhanced their capacity for party messaging,Footnote 11 they are not more effective than parties of earlier eras at actually delivering on the policy agendas they advocate and campaign on. These findings have important implications for our understanding of party responsibility and accountability in the United States, the strength and resilience of the U.S. constitutional system, and the role parties and leaders play in congressional policymaking.

Party Government in the U.S. Constitutional System

In today’s era of polarized parties and strong legislative party organizations, congressional majority parties are expected to pursue and enact laws so as to shift public policy in accord with their ideological preferences and create a record of partisan lawmaking accomplishments to tout in the next election campaign. At the same time, these parties must still work within a constitutional system that persistently checks partisan ambitions. Institutional changes inside Congress—including the centralization of power in leadership offices,Footnote 12 greater party cohesion,Footnote 13 and stronger legislative party organizationsFootnote 14—may avail little against the constitution’s constraints.

Theories of Party Power

Although theories of congressional party government differ in important respects, they share at least one commonality: they contend that congressional majority parties organize Congress to facilitate the enactment of their programmatic agendas. Key changes in congressional procedure and organization over time suggest that contemporary majority parties should be better able to achieve their legislative goals than those of less partisan eras. Today’s Congress frequently eschews traditional, decentralized, and committee-led processes in favor of unorthodox and behind-the-scenes processes managed by party leaders.Footnote 15 Members have provided their leaders a bevy of procedural and agenda-setting tools to structure the legislative process in ways that stand to benefit the majority party.

Aldrich and Rohde’s conditional party government posits that when “the preferences of party members are homogenous, especially within the majority party, and different between the parties,” members of Congress will provide their “legislative party institutions and party leadership stronger powers and greater resources” and encourage their party leaders to “use those powers and resources more often.”Footnote 16 The purpose of these organizational changes is to “enact as much of the party’s program as possible.”Footnote 17 Den Hartog and Monroe apply a similar logic to the Senate.Footnote 18

Other theories of party power, including procedural cartel theory Footnote 19 and strategic party government,Footnote 20 contend that the majority party in Congress structures the institution to enable it to construct a record of accomplishments to aid the party in future elections. Cox and McCubbins argue that the majority party provides its leaders, or “senior partners,” with substantial powers to both block legislation that divides the party internally and facilitate the passage of laws that its members can tout in subsequent elections. These powers and abilities are expected to grow as party organizational strength increases as, “the better the majority party’s control of such powers is, the more able will it be to fashion a favorable record”.Footnote 21

These theories of party power in Congress differ in their causal logics and in numerous specific predictions. Nevertheless, taken together, they, individually and collectively, imply that strong and unified majority parties with centralized power and decision-making authority, such as the congressional majority parties of today, should be better positioned to deliver on their campaign promises than the weaker and less cohesive majority parties of earlier eras.

Obstacles to Party Government

Theories of party government in Congress tend to deemphasize the harsh constitutional realities that stand in the way of partisan achievement. Regardless of how the House and Senate might organize themselves internally, the broader constitutional system’s bicameralism, separation of powers, and electoral incentives can persistently frustrate efforts at partisan lawmaking.Footnote 22 These obstacles can render even strong majority parties incapable of enacting laws that advance their policy preferences or give them partisan policy achievements to tout on the campaign trail.

The separation of powers between Congress and the president regularly stands in the way of passing a partisan platform. Not surprisingly, vetoes and veto threats are more common under divided government.Footnote 23 Divided government has been the typical state of affairs since the middle of the twentieth century, with different parties controlling Congress and the presidency 69% of the time since 1954 and 75% of the time since 1980.

Congress’s bicameral structure also can stymie a majority party’s efforts. The two chambers’ different methods of apportionment, election, and internal procedure often frustrate bicameral agreement. The staggered election of senators can put the Senate and House out of synch, especially following electoral waves. The Senate’s super-majoritarian cloture requirements frequently prevent the majority from advancing legislation on party lines.Footnote 24 Binder finds that “bicameralism is perhaps the most critical structural factor shaping the politics of gridlock.”Footnote 25

Further, the individualized election of members of Congress from geographically distinct districts and states results in relatively heterogeneous congressional parties (especially compared to the legislative parties in parliamentary systems). As such, leaders often struggle to cultivate internal party consensus behind specific legislative proposals. It is by no means clear that members will defer to party leaders on policy questions at the cost of their own electoral security,Footnote 26 even if doing so might have collective benefits for the party.

Meanwhile, minority party unity and organizational strength have increased alongside majority party unity and strength in Congress, and this serves as another check on congressional majorities. Like the majority party, minority parties have delegated more authority to their leaders, as well as empowered them to use aggressive and creative tactics to check the efforts of the majority.Footnote 27 Stronger minority party organization and cohesion can combine with the other difficulties present in the constitutional system to further limit single-party lawmaking. Under such conditions, the minority can more easily hold together to oppose and block majority party efforts. At the same time, a strong and cohesive minority can effectively bargain with the majority for concessions in return for supporting their legislative proposals.Footnote 28

Although increases in party polarization and party organization would be expected to facilitate more partisan lawmaking, there are numerous systemic obstacles in the way of parties achieving their goals. The U.S. constitutional system of separated powers, bicameralism, and separate elections in geographic constituencies may still require, far more often than not, that congressional majority parties seek minority party buy-in in order to successfully pass laws, even in today’s partisan political environment.

Assessing Partisan Efficacy in Lawmaking

The key question, then, is whether the stronger congressional parties of recent decades have a better track record of partisan lawmaking success compared to the weaker parties of earlier eras. This question has seen surprisingly little attention from scholars. Mayhew has shown that divided government does not stand in the way of the enactment of landmark legislation, even under recent presidents.Footnote 29 Other work establishes that bipartisanship persists at some level in the contemporary CongressFootnote 30 and Congress remains capable of problem solving.Footnote 31 On the other hand, Binder finds that today’s contentious, party-polarized environment generates more legislative stalemate, meaning congressional failure on a greater proportion of the policy issues on the national policy agenda.Footnote 32

But scholars have not mapped such lawmaking patterns onto questions of majority party capacity. We want to know not whether Congress is more or less legislatively productive overall or whether it successfully addresses pressing policy problems on the national agenda, but to what extent parties are able to bend legislative outcomes toward their policy preferences. Our question centers on parties’ ability to deliver on their campaign promises, particularly in a polarized era when voters perceive the parties as offering clearly distinct policy alternatives.Footnote 33 Has increased party cohesion and centralization of power in Congress better enabled majority parties to enact their policy priorities?

Many of the empirical findings that make a case for majority party power in Congress analyze legislative action in just one chamber and do not consider whether the majority party’s efforts resulted in new, partisan-favorable laws. For instance, Monroe and RobinsonFootnote 34 and Young and WilkinsFootnote 35 show that the majority party successfully uses restrictive rules to achieve non-median outcomes in the House-passed version of bills. Cox and McCubbins demonstrate the abilities of majorities to avoid majority party rolls and to roll the minority.Footnote 36 Aldrich and Rohde provide many cases of the majority leadership using its powers to advance partisan policies in the House,Footnote 37 but most did not pass into law.Footnote 38

In this paper, we take stock of majority party power in lawmaking, or the lack thereof, by analyzing two sources of data: (1) roll-call votes on the passage of laws passed by Congress and signed by presidents from 1973–2016, and (2) a unique dataset identifying the major partisan legislative priorities of each congressional majority party from 1985–2016.

Passage Votes

We compiled passage votes in the House and Senate on bills becoming law from 1973–2016 (the 93rd–114th congresses). We analyze all House bills (H.R.) receiving passage roll-call votes in the House that went on to become law,Footnote 39 and all bills and joint resolutions receiving passage roll-call votes in the Senate that went on to become law.Footnote 40 We focus on the initial passage roll-call votes and not votes on bicameral reconciliations (i.e., conference reports) that typically broaden support. Such an approach biases our analyses toward finding higher levels of partisanship on legislation,Footnote 41 and also allows us to ascertain if bipartisanship typically results only when the House must accommodate the Senate’s supermajoritarian processes in reaching bicameral agreement, or whether the House legislates in a bipartisan manner from the outset. We also analyze separately the enactments on Mayhew’s list of landmark laws from 1973–2016, assessing the final roll call taken in each chamber on each measure.Footnote 42 Looking at this subset of laws allows us to assess whether lawmaking has become more partisan on major legislation.

Party Agenda Priorities

Second, we assess majority party success by taking stock of whether they were able to enact their priority legislative items in each Congress, 1985–2016 (99th–114th congresses). This analysis required first establishing a list of the priority items for each congressional majority party and then tracking the legislative outcomes on each item.

We used a multi-pronged approach to identify majority party priorities during each Congress. First, we read the opening speeches made by the leader of the majority party in each chamber at the start of each Congress.Footnote 43 In each speech, we identified any policy items or issues the leaders indicated they hoped or planned to address in the coming two years and recorded those items as priorities. Second, we looked at the bills inserted into the slots reserved for the Speaker of the House and the Senate Majority Leader.Footnote 44 The policy proposals introduced in these slots were also recorded as priority items for the majorities in each Congress. Third, we read articles in CQ Magazine during the weeks before and after the start of each Congress that discussed policy items expected to be on the congressional agenda. Items addressed in leader speeches or introduced into leadership bill slots were often discussed in some detail in CQ Magazine, allowing us to sharpen our understanding of each item.

Most agenda items were identified in more than one source. For instance, some agenda items were mentioned in one or both speeches, introduced in reserved bill slots in one or both chambers, and discussed by CQ Magazine. Most items (60%) were identified in at least two sources, and the average agenda item was found in 2.1 sources. Items that were only mentioned in CQ Magazine but did not appear in a leader’s speech or in a leadership-reserved bill were not included on our list of party priorities.

This approach yielded a list of 254 priority agenda items. Majority party agendas ranged in size from 11 to 24 items, with the average number of priority agenda items around 13.Footnote 45 In the few congresses with split partisan control of the House and Senate (the 99th, 107th, 112th, and 113th), we identified each majority party’s agenda items. The full list of agenda items is found in the online appendix.

This approach for identifying majority party priorities performs well for the post-1984 era. Prior to 1985, the utility of leader speeches becomes spotty. Senate majority leaders did not regularly give these speeches before that time. In the House, while the Speaker and Minority Leader have long given speeches at the start of each congress, those given by O’Neill and Michel in the early 1980s were particularly devoid of policy content. The “leadership bills” indicator also performs inconsistently before 1984, particularly in the Senate. The GOP Senate leadership in the 97th (1981–1982) and 98th (1983–1984) congresses, newly returned to the majority after nearly three decades out of power, did not appear to use its reserved bill slots, often allowing Democrats to introduce bills with those designations. Extending our data series on party agenda priorities before 1985 would require a different approach.Footnote 46

For each item identified during the period, we coded the outcome obtained by the majority party into one of three categories. Either (1) the majority got most of what it wanted with a new law(s) enacted achieving most of what the majority set out to achieve; (2) the majority got some of what it wanted, passing a new law(s) falling short of the party’s goals or requiring substantial compromise; or (3) the majority got none of what it wanted, failing to enact any new law on its policy priority. We relied on journalistic coverage of each item to do this coding, drawing primarily on coverage in CQ Magazine and on articles providing an overview of the accomplishments of each congress in various editions of the CQ Almanac. Occasionally, we also drew upon other periodicals such as Roll Call, The Hill, and the Washington Post. It was not difficult to differentiate between laws widely regarded as a “win” for the majority party and laws where the majority party had to drop key priorities or make concessions. After coding each item for its outcome, we also recorded the partisan split on the relevant final passage votes (if any).Footnote 47 In addition, we noted the amount of each party’s support for the new law, as well as the support or opposition from the top leaders of each party in each chamber.Footnote 48

The Persistence of Bipartisan Lawmaking in Congress

Are today’s stronger congressional parties better at enacting their agendas? Do the more cohesive majority parties of recent years pass laws on a partisan basis more often than majority parties in less party-polarized contexts? Assessing more than 40 years of data on passage votes that resulted in new laws and 32 years of congressional majorities’ efforts to enact their partisan priorities, we find the answer to these questions is generally no. There are few trends in the data. To a similar degree across the decades, congressional majorities struggle to enact partisan agendas. Majority parties rarely get most of what they want. When they succeed or partially succeed, majority parties usually need bipartisan support to get it done.

Minority Party Support on Passage Votes

If majority parties are better able to pass partisan laws under contemporary conditions of increased party cohesion and party polarization, then we should find more laws enacted by party-line votes and over the opposition of a majority of the minority party than in the past. Figure 1 shows the average percent of minority party lawmakers voting in favor of all new laws and Mayhew’s landmark laws during each Congress from 1973–2016. The most striking patterns are the lack of any clear trend and the persistence of robust minority party support.

Figure 1 Average percent minority party support on passage of bills becoming law, 1973–2016

In every Congress since the early 1970s, the average percent of minority party members supporting new laws on the initial House passage vote was higher than 71%. In most Congresses, the share exceeds 80%. The figure displays a reference line at 50% in order to designate lawmaking that garnered support from a majority of the minority party. The four congresses with the highest average levels of minority party support all took place after 2000: the 107th (2001–2002), the 108th (2003–2004), the 109th (2005–2006), and the 113th (2013–2014). Because the data displayed are from initial House passage votes, these high levels of House minority support on legislation cannot be simply attributed to the need to arrive at bicameral agreement with the supermajoritarian Senate.Footnote 49 The data do not show that minority party support for enacted legislation is reliably lower in unified government.Footnote 50 Note that although minority party support for enacted legislation was relatively low in the 103rd (1993–1994) and 111th (2009–2010) congresses under unified government, the other recent congresses with unified government—the 108th (2003–2004) and the 109th (2005–2006)—do not stand out from the overall time series.

High levels of minority party support on laws are not simply an artifact of broad bipartisan support for low profile or inconsequential legislation. The minority party also votes in favor of landmark laws at high rates. Minority party support for landmark laws is 66% on average and only dips below 50% twice (in the 103rd and the 111th congresses). Compared to all laws, there is more variation from congress to congress with landmark laws, but little evidence of an overall decrease in minority party support in recent years as majority party strength and party polarization increased.Footnote 51

Similar patterns are found in the Senate. With the exception of the 111th Congress (2009–2010), the average percent of minority party senators supporting new laws has been higher than 62% since the early 1970s, with most congresses registering levels of minority party support better than 75%. Since the start of the George W. Bush administration, only two congresses have seen levels of Senate minority party support dip below 70% for all new laws, the 111th (2009–2010) and 113th (2013–2014). The 114th Congress (2015–2016) had one of the highest rates of minority party support recorded. Among landmark laws, the pattern is similar: minority party senators back the passage of landmark laws at high rates, with most congresses registering average minority party support at 70% or better, with no appreciable trend in the data. In both the House and Senate, these data indicate that most new laws, including landmark laws, attract substantial minority party support, and do so at rates similar to those found in less partisan periods.

Figure 2 assesses partisan lawmaking via another metric—the minority party roll. A party is rolled when a measure is passed despite a majority of that party voting in opposition. Rolls have frequently been used to assess partisan legislating and partisan strength in legislatures.Footnote 52 Scholars focus on how often the majority rolls the minority because a majority party seeking to claim partisan credit for lawmaking needs to pass laws over the opposition of the minority party.Footnote 53 If most of the minority also supports the legislation, the majority will gain less relative advantage in party reputation. (Rather, both parties can claim a win.)

Figure 2 Minority party roll rates on passage of bills becoming law, 1973–2016

Figure 2 exhibits little upward trend in minority party rolls in House lawmaking overall despite the increased centralization of power in the majority party leadership.Footnote 54 In all but four congresses, the minority party was rolled on less than 25% of new laws, and typically, minority party roll rates fell below 15%. House minority party roll rates are higher on landmark laws with the House minority rolled, on average, on 32% of landmark laws. However, for both all laws and landmark laws, the trend in minority party rolls over time is insignificant.Footnote 55 The only notable feature in the data are spikes in minority party rolls on landmark laws during the 103rd (1993–1994) and 111th (2009–2010) congresses, two recent congresses with unified Democratic party control. The same pattern is not evident for the 108th and 109th congresses (2003–2006) with unified Republican party control.Footnote 56

In the Senate, the majority party rarely rolls the minority party on the passage of new laws. Minority party rolls are generally uncommon, happening on less than 16% of all new laws in most congresses and rarely exceeding 25%. Some recent congresses had higher than average percentages of minority party rolls, but others, including the 110th (2007–2008), saw very few, and overall the slight uptick in Senate minority party rolls on all new laws is statistically insignificant.Footnote 57 On landmark legislation, the Senate minority is rolled only 19% of the time on average. Several recent congresses never saw the Senate minority party rolled on the passage of a landmark law, including the 110th (2007–2008), 112th (2011–2012), and 114th (2015–2016) congresses.Footnote 58

Figure 3 looks for evidence of partisan (or bipartisan) lawmaking in one additional way: assessing how often the majority party in each chamber needed minority party votes to pass new laws. In other words, we simply calculate the percentage of new laws for which the majority party supplied a chamber majority with its own members, thereby making any minority party votes superfluous. These figures show the percentage of enacted laws on which the majority party did not muster a sufficient number of votes to pass the bill from among its own ranks alone. For those roll call votes in which the Senate imposed a 60-vote threshold, we consider whether members of the majority party alone provided the necessary 60 votes.Footnote 59 This is not a widely used metric, but it reveals those circumstances where the issues were sufficiently controversial and the majority party insufficiently cohesive to have passed the law without assistance from some members of the minority. As such, it points to a critical form of bipartisanship. Even under circumstances where a majority of the minority party opposes a bill, individual members of the minority may provide the votes decisive for a successful outcome.

Figure 3 Minority party votes needed for passage on bills becoming law, 1973–2016

If majority parties had become more efficacious over time, we would find a negative trend, but figure 3 shows that recent House majority parties are no more self-sufficient in lawmaking than the majority parties of the 1970s and 1980s. For laws generally, the House majority party usually (85% of the time), but not always, musters the votes necessary for passage of laws without requiring any votes from the minority party. However, despite increases in majority party strength, the need for minority party votes has not decreased.Footnote 60 On landmark laws, the House majority party musters sufficient support from among its own ranks less frequently—just 60% of the time on average. Put differently, the majority party tends more often to need minority party help to pass the most important laws. But again, no significant trends are evident in the data.Footnote 61

Compared to the House, Senate majorities more frequently need minority party support to enact laws. On average, the Senate majority party provided sufficient votes about 67% of the time to pass both all laws and landmark legislation. A greater need for minority party support in the Senate is not surprising given how the minority party exploits the chamber’s cloture rules under polarized conditions.Footnote 62 As a result, the Senate majority has needed minority votes more frequently over time, and this increase is statistically significant for landmark laws.Footnote 63

Altogether, across figures 1–3, we find little evidence that partisan lawmaking has increased along with increases in party polarization and majority party strength. Only one trend in the data is statistically significant (the need for minority party votes in the Senate on landmark laws) and it runs counter to the expectation that today’s more cohesive majorities would be more legislatively effective.

To assess the robustness of these bivariate findings, we also conducted multivariate analyses reported in tables 1 and 2. The analyses are of each of the variables assessed here (percent minority party support, minority party rolled, and minority party support needed) for each of the initial passage votes on each law. Several independent variables are included. The most important are, first, a measure for party polarization—party median distance—which is measured as the absolute difference between the parties’ first dimension DW-NOMINATE medians in each chamber, and second, a measure for majority party strength—majority party unity—which is measured as the inverse of the standard deviation of first dimension DW-NOMINATE scores among members of the majority party. As party median distance and majority party unity increase, party government theories expect that we should see lower levels of minority party support, higher likelihoods of minority party rolls, and lower likelihoods of minority party votes needed, all else being equal.

Table 1 Party voting on initial passage roll-calls in the House of Representatives, 1973–2016

*p<.05; ** p<.01

Notes: Columns 1 and 2 are OLS regressions.

Columns 3–6 are logistic regressions.

Each analysis includes robust standard errors correcting for clustering by each Congress.

N’s vary by analyses due to the fixed effects.

Since the unit of analysis for the key independent variables in these analyses is by Congress, the effective N for these analyses is n=16, rather than n=2,100+.

Table 2 Party voting on initial passage roll-calls in the Senate, 1973–2016

*p<.05; ** p<.01

Notes: Columns 1 and 2 are OLS regressions.

Columns 3-6 are logistic regressions.

Each analysis includes robust standard errors correcting for clustering by each Congress.

Since the unit of analysis for the key independent variables in these analyses is by Congress, the effective N for these analyses is n=16, rather than n=2,100+.

Majority Party Sponsor excluded from the analyses in columns 3 and 4 as it perfectly predicted the dependent variable.

We include several other variables in the analyses that might affect levels of partisanship on lawmaking. These include the number of seats held by the majority party in each chamber, a dichotomous indicator of divided government for each Congress, whether or not the sponsor of each law was a member of the majority party, and the law sponsor’s first-dimension DW-NOMINATE distance from the chamber median. We also included fixed effects for each bill’s issue topic,Footnote 64 and in each analysis robust standard errors are calculated to correct for clustering by congress. The analyses, specifically, are OLS regression analyses for % minority party support, and logistic regression analyses for minority party rolls and minority votes needed.

The results show a limited, and often only conditional, relationship between measures of party distance and majority party unity and predicted levels of partisanship in passage votes in the House (table 1). The coefficients for the polarization measure (party median distance) are insignificant in every test, and the level of majority party unity only has an independent effect in one test (predicting likelihoods that minority party votes are needed). Otherwise, the unity of majority party members is only relevant when the majority also controls a large share of the chamber’s seats (as demonstrated by the interaction term between majority party seats and majority party unity), a condition rarely found with the exception of the large, unified Democratic chamber majorities of the 111th Congress (2009–2010).

In the Senate (table 2), there is slightly more evidence that partisan change in Congress has affected levels of partisanship on passage votes, but the results are still mixed. A bigger distance between party medians consistently predicts higher likelihoods of minority party rolls (columns 3 and 4), but minority rolls remain unlikely in any case. The model (column 4) predicts that at one standard deviation below the mean of party distance there is a 6% likelihood of a minority party being rolled, and at one standard deviation above the mean that likelihood increases to 16%. This is an increase, but it underscores that minority party rolls are uncommon even at high levels of party distance in the Senate. In fact, even at the highest level of party difference, minority rolls are predicted to not occur almost 70% of the time.

As in the House, the unity of the majority party has little impact on lawmaking votes in the Senate, and in fact, does not have an independent effect in any analysis. Again, the number of seats held by the majority party appears to have the most significant effect, as well as a conditioning effect on majority party unity. Large and unified Senate majority parties obtain lower rates of minority party support, higher likelihoods of minority party rolls, and lower likelihoods that minority party votes are needed for passage. This makes sense as large, unified Senate majorities can more easily work around the Senate’s filibuster rules. However, again, this combined condition is rare with the exception of the 111th Congress (2009–2010).

A few other results from the analyses are worthy of discussion. Across the analyses, the impact of divided government is very modest. The coefficients never have a significant impact on passage votes on all new laws in the House. In the Senate, minority party rolls are predicted to be significantly less common under divided government (predicted to occur on 9% of votes), but they are still uncommon under unified government (15%). Otherwise, divided government appears to have little relevance for how partisan or bipartisan lawmaking is in Congress.

We conducted similar analyses to those in tables 1 and 2 for Mayhew’s landmark laws, but without any bill-level measures, such as the party or extremity of each law’s sponsor (these data are not included in Mayhew’s data). Limited inferences can be drawn among solely congress-level covariates, as the effective N’s are too small to make sense of the statistical results. Nonetheless, these results largely confirm the findings in tables 1 and 2 and can be found in the online appendix.

Altogether, little in the data presented here suggests that contemporary congressional majorities are better able than those of the 1970s and 1980s to pass partisan laws. Increases in party polarization and majority party unity have had minimal impacts on levels of partisanship on passage votes. Although minority party rolls have become slightly more common in the Senate as partisan change has occurred, they remain altogether uncommon. Only under conditions of large and unified majorities does partisanship on lawmaking appear to noticeably increase, but congresses meeting these conditions are rare—the 111th Congress (2009–2010) may be the only example in the years we analyze. Despite decades of dramatic partisan change, lawmaking has generally remained overwhelmingly bipartisan. Contemporary majority parties do not enact laws on party-line votes more frequently than those of earlier eras, and party polarization has had little impact on levels of partisanship found on passage votes.

Contemporary Efforts to Enact Partisan Agendas

The acid test for congressional party government is a majority party’s ability to enact its programmatic agenda priorities. Congressional parties do not have partisan goals on all issues, and many items taken up and passed into law do not relate to party goals, including some landmark laws. Theories of party government indicate that we are most likely to find significant party influence on party priority items.Footnote 65 A party’s agenda reflects its central goals, the campaign promises its members made, and the issues on which its members would like to establish a record of accomplishment.

Analyses of majority parties’ priorities also more directly allow us to assess if party polarization and increased party organizational strength in recent years has better enabled congressional majority parties to succeed in enacting their programmatic agendas. In fact, these data allow us to assess overall party effectiveness at turning partisan priorities into laws, as well as the means by which they succeed in passing laws related to these priorities. In other words, when the majority does succeed, does it do so on a partisan or bipartisan basis?

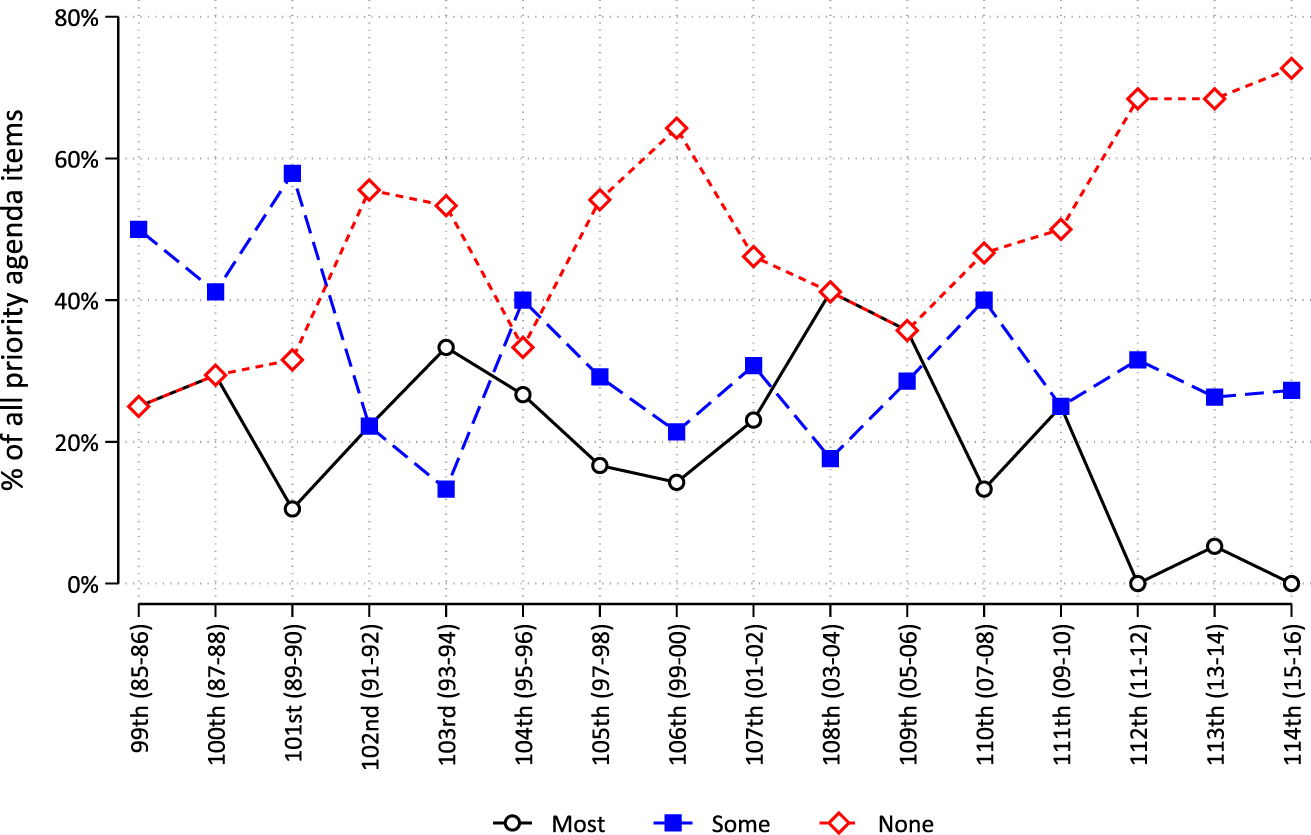

Figure 4 first provides an overview of the outcomes of each majority’s agenda items for the 99th–114th congresses (1985–2016). The full tallies for each congressional majority are found in the online appendix. For each congress, the figure shows the percent of the majority’s priority items that fall into each of the three outcomes—the majority party achieving most, some, or none of what it wanted to achieve.Footnote 66 The overall results indicate contemporary congressional majorities are rarely able to enact partisan agendas. Typically, a majority party successfully acts on only half of its agenda priorities in any form. On 49% (124/254) of policy priorities, congressional majorities achieved none of what they wanted to achieve.

Figure 4 Legislative outcomes of majority party agenda items

Note: The 99th, 107th, 112th, and 113th congresses featured split party control of the House and Senate. The combined agenda items of both parties are included in these tallies.

As evident in the figure, majority party success varies quite a bit from congress to congress. Some congressional majorities avoided racking up failures, including the Republican majorities during the first six years of the George W. Bush administration (2001–2006), and the Republican Revolution majority of the 104th Congress (1995–96). Nonetheless, in eight of the 16 congresses, majority parties failed half the time or more on their agendas. Some majorities, including Democrats in the 112th (2011–2012) and Republicans in the 106th (1999–2000), 113th (2013–2014), and 114th (2015–2016) congresses got none of what they wanted on the vast majority of their agenda priorities.

Rather than achieving better rates of success, the more cohesive majority parties of recent years have actually fared worse in terms of legislative outcomes. Across the time series, there is an upward trend in majority party agenda failure. Over time, majority parties have achieved most of their policy goals on a decreasing share of their agenda items and have failed entirely on an increasing share of their agenda. Congresses in the 2010s racked up the highest failure rates and the lowest success rates over the post-1985 period.Footnote 67 However, even before these last few congresses, there was a clear upward trajectory of majority party failure.Footnote 68 This is the case, even though the majority parties of these years are not setting forth agendas that are lengthier or in any obvious respect more ambitious in policy terms compared to agendas of the 1980s or 1990s.

If failure is common, overwhelming success is exceedingly rare. On just 20% of agenda items—50 items in total over the period—did a congressional majority achieve most of what it set out to achieve. During some congresses, such successes were nonexistent. Neither party got most of what it wanted on any agenda item during the 112th Congress (2011–2012). Democrats had only one such success during the 113th (2013–2014) when they ushered through a reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act (PL 113-4). Republican majorities in the 113th (2013–2014) and 114th congresses (2015–2016) did not get most of what they wanted on any agenda priority.

Majority parties were somewhat more successful at getting some of what they wanted. In fact, in most cases, majority party success appears more easily achieved through compromise. In 11 of the 16 congresses, majority parties achieved some of what they wanted more frequently than they achieved most of what they wanted. There is no pattern in the data. While the majorities of the late 1980s were relatively adept at achieving some of what they wanted, majorities have achieved these kinds of successes at a steady rate since 1991.

Beyond just looking at successes and failures, we also need to assess how bills addressing agenda items were passed. For those agenda priorities on which majority parties achieved either some or most of their policy goals (n=130), figure 5 displays the percentage of the time they did so (1) over the opposition of a majority of the minority party in both chambers, (2) with the support of a majority of the minority party in at least one chamber, and (3) with the support of one or more of the minority party’s top leaders in at least one chamber. Items can fit into more than one category, but only the first of these categories captures successes in partisan lawmaking.

Figure 5 How majority parties succeed on their agendas

Note: The 99th, 107th, 112th, and 113th congresses featured split party control of the House and Senate. The combined agenda items of both parties are included in these tallies.

Just as majority parties rarely achieve most of what they set out to achieve, they rarely enact new laws addressing agenda items over the opposition of the minority party. On just 22% (28/129) of successfully legislated agenda priorities did a congressional majority party enact legislation over the opposition of a majority of the minority party in both chambers. Almost a quarter of this total (6/28) occurred during the 111th Congress (2009–2010) alone. In five congresses, this outcome never occurred. Instead, the vast majority of party agenda items passed with the support of a majority of the minority party in at least one chamber (79%, 102/129), or with the endorsement of at least one of the minority party’s top elected leaders (86%, 111/129). In fact, in 9 of 16 congresses, minority party leaders in at least one chamber endorsed fully 100% of the majority party agenda items that passed into law. There is also no trend in these data. Congressional majorities have not become better or worse at enacting their priorities over the opposition of the minority. A few congressional majorities did so more frequently than average—those of the 103rd (1993–1994), 108th (2003–2004), and 111th (2009–2010) congresses—but even these congress’s majorities varied in their overall efficacy.Footnote 69

The preceding analyses make one thing clear—contemporary congressional majorities almost never enact laws achieving most of what they set out to achieve by rolling their party opponents. Among the 254 agenda items we identified, on just 10 items (4%) did a congressional majority get most of what it wanted and enact a new law over the objections of most of the opposing party in both chambers and without the endorsement of at least one elected party leader of the opposing party in either chamber. These purest of party victories include three of the Democrats’ major accomplishments in the 111th Congress (the Affordable Care Act, the Dodd-Frank financial regulatory reforms, and the SCHIP reauthorization), the PAYGO rules adopted in the 110th Congress, the Class Action Fairness Act passed by Republicans in the 109th Congress, two Republican accomplishments during the 108th Congress (Medicare Part D and the second round of the so-called Bush tax cuts), and three Democratic accomplishments in the 103rd Congress (The Family and Medical Leave Act, the Motor Voter law, and the 1993 omnibus crime bill). Notably, nine of these ten items were enacted during periods of unified party government, and the other—the PAYGO rules—did not require a presidential signature.

That these items were so few underscores the most salient finding from our analyses: despite rising party polarization and increased party strength in both the House and Senate, congressional majorities can rarely succeed in enacting policy change over minority party opposition. They are also no more likely to do so today than in the past. When parties succeed in enacting their agenda priorities, they usually do so with the support of a majority of the opposing party in at least one chamber of Congress and with the endorsement of at least one of the opposing party’s top leaders. Consequently, congressional majority parties usually have few partisan lawmaking accomplishments to tout on the campaign trail and can rarely claim to have decisively moved public policy is a partisan direction.

Lawmaking as a Process of Bipartisan Accommodation

The impulse of the parties . . . to clothe themselves in a dogmatic and argumentative garment of high public purpose is so strong that a wholly misleading picture of the process is likely to be conveyed by the mere words of party propagandists.

E.E. SchattschneiderFootnote 70

Even amidst today’s party polarization, Congress continues to pass laws with broad bipartisan support. Despite increased party organizational strength inside Congress, contemporary majority parties do not succeed in enacting partisan legislative agendas at rates any higher than those of less party-polarized congresses. Our findings suggest that decades of partisan change and institutional evolution in Congress have been no match for the harsh constitutional realities that stand in the way of partisan ambitions. The veto points, super-majoritarian requirements, and electoral incentives created by the U.S. constitutional system, as well as by the counterbalancing strength developed among minority parties, continue to frustrate majority parties. Lawmaking remains a process of bipartisan accommodation.

These findings have several important implications. First, they have implications for our understanding of majority party capacity in Congress. Despite many changes in the legislative process that have strengthened parties and leaders, there is not appreciably more partisan lawmaking. When Congress gets down to the brass tacks of enacting laws, it still typically needs to cultivate bipartisan support. House majority parties may pass non-median bills, but these bills are unlikely to pass both chambers or earn a presidential signature. Many more laws look like the 21st Century Cures Act (PL 114-255) than the Affordable Care Act (PL 111-148).

Second, these results call into question the majority party’s ability to campaign on its record of partisan achievement. Scholars argue that moderate legislators may be induced to support their parties because the outcome—a partisan policymaking success—will give the party as a whole something to run on in the next election.Footnote 71 Parties simply do not have many such successes to claim, particularly in recent party-polarized congresses. Legislative votes that distinguish the parties abound, but these votes are very rarely the enactment of laws. In many cases, they are messaging efforts that have no effect on public policy. On the occasions when majority parties do succeed in lawmaking, they rarely do so over the opposition of the minority party. Most lawmaking accomplishments are bipartisan, allowing both parties to claim credit.

Our findings suggest that congressional majority parties fare somewhat worse in enacting their agendas than do presidents. Mayhew finds that presidents since Truman have succeeded in getting Congress to enact about 60% of their proposals.Footnote 72 Tracking the policy outcomes of majority party agendas, we find the majority parties succeed (either in full or in part) on only about half of their proposals.Footnote 73 Extending beyond Mayhew’s “scorecard” of success and failure, we also examine how majority parties achieve their successes. We conclude that not only does the constitutional system make it difficult for majority parties to succeed, but clear, partisan successes are exceedingly rare—occurring on just 4% of the agenda items we analyzed. Even in periods of strong parties, legislative enactments rarely skew public policy in a substantial way toward the majority party’s preferred policy positions.

These findings raise questions about party accountability more broadly within the American system of separated powers and checks and balances. Congressional party strength today is arguably at its highest point in over a century, leaders have been empowered, and committees have been eclipsed. Party reformers of the past would have welcomed these developments, hoping that more programmatic and cohesive parties would improve governmental accountability and responsiveness in our otherwise fractured political system.Footnote 74 However, our results indicate that even when legislative parties are at their strongest, the American constitutional system frustrates programmatic partisan lawmaking. Even today, congressional majority parties cannot effectively steer the ship of state and move public policy decidedly in one direction or the other. Laws still typically reflect bipartisan compromises, muddling party responsibility for public policy outcomes, and making it difficult for voters to accurately determine who deserves the credit (or blame). Increases in party polarization and party organization have not solved the problems that concerned advocates of party reform 70 years ago. Where lawmaking is concerned, strong parties have not overcome the compromise-inducing structure of the U.S. constitutional system.

Even though parties in Congress seldom enact programmatic agendas in the manner sought by theorists of responsible party government, we should not conclude that they are unimportant. Congressional parties play a vital role in conflict-clarifying representation.Footnote 75 By bringing forward messaging bills and encouraging their members to hold the party line in position taking, and by taking sides among various political interests and publicly displaying their coalitions, congressional parties help clarify the lines of political conflict for the public and enable the “ventilation of opinion for the education of the country at large.”Footnote 76 Contemporary parties are clearly better at this than parties of the past, as demonstrated by the rise in partisan voting on the numerous measures that never become law and the extensive growth and institutionalization of party message operations in both chambers and both parties.Footnote 77 It is likely that the public’s improved understanding of party differencesFootnote 78 owes something to the congressional parties’ strengthened capacities for conflict-clarifying representation.

Congressional parties also play a vital role in making law, just not in the way typically conceived. Our results clearly indicate that majority parties usually succeed (when they succeed) by co-opting support from the minority party, rather than rolling the opposition. Today’s legislative processes put party leaders at the center of legislative negotiations.Footnote 79 Leaders negotiate across branches, chambers, and parties with the aim of winning the necessary support to enact laws in a challenging political system. Once those agreements are reached, leaders must then work to convince rank-and-file members to set aside partisan or ideological inclinations and support the compromise. Expecting that congressional majority parties will crush their enemies, Conan-the-Barbarian style, misunderstands the role of parties in our compromise-inducing political system. Rather, leaders must typically negotiate bipartisan agreement and then convince rabid partisans on both sides to accept unsatisfying compromises. The ability to maintain support for these negotiated agreements is often the true test of party leadership and party influence in the contemporary House and Senate.

It is worth reflecting on these findings in the light of the unified Republican government of the first two years of the Trump Presidency. Even with control of the House, Senate, and presidency, alongside continued party polarization, Republicans have repeatedly struggled to enact their agenda.Footnote 80 High-profile attempts at one-party lawmaking have failed, most prominently the 2017 effort to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act in which the majority party fell short despite the use of budget reconciliation procedures that would have allowed Republicans to overcome Democratic filibusters in the Senate. Omnibus budget and spending measures have required Republicans to make concessions to the minority Democrats, and such measures have passed with strong bipartisan support.Footnote 81 Only one partisan achievement stands out, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (PL 115-97), enacted via budget reconciliation. Consistent with the data analyzed for this paper, strong parties and unified government provide little relief from harsh constitutional realities.

Altogether, the evidence here strongly suggests that we should reconsider our understanding of party government and party influence in Congress. Persistent bipartisanship on congressional lawmaking does not mean parties do not matter, but it may mean parties matter in a different way than we have often thought.

Supplementary Materials

Regression Analyses of Mayhew’s Landmark Laws

Regression Analyses of Majority Party Priority Agenda Items

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592718002128