Introduction

This study took place in a Year 7 class in a selective mixed independent school and examines the use of learning strategies for Latin vocabulary. The students were asked how they normally learn vocabulary, and these results using their normal method are compared to the results of using three different strategies.

This subject was chosen as I observed that many students who are otherwise successful at school struggle in particular with the vocabulary learning aspect of studying Latin. As successful study of language relies so heavily on retention of vocabulary, this can be an obstacle both in terms of difficulty understanding passages where large numbers of lexical items are not known, and also in adversely affecting motivation and confidence in the subject.

Much has been written on the learning of vocabulary in modern languages. In this study I investigate the extent to which techniques found to be successful in modern languages are applicable to Latin, on which less research has been done. I will also focus on the practicality of using any strategy in the classroom context within the constraints of keeping up with schemes of work, teacher preparation time, and the capabilities of Year 7 students; it was important to me that my findings be applicable in my future teaching career.

This study takes place in a selective school with limited numbers of students identified as having Special Educational Needs. Results are consistently excellent, with 94% of GCSE entries and 79% of A level entries last year being awarded A* or A. Nonetheless, the sample does include a couple of students identified as having literacy difficulties in their first language and careful attention will be paid to whether outcomes for these students are consistent with those of the class as a whole – i.e. I will not view as successful any strategy which results in improved marks for the class as a whole, but causes these disadvantaged students to fall further behind.

As noted above, motivation and confidence in Latin can suffer when a student is having significant difficulties with the retention of vocabulary. This study will therefore also address the question of which strategies are effective at motivating students.

The research questions this study aims to address are:

1. Which learning strategies seem to aid retention of Latin vocabulary?

2. Which learning strategies are practical for regular classroom use?

3. Which learning strategies seem to have a beneficial effect on student motivation?

Literature Review

The majority of literature on the subject of vocabulary acquisition is concerned with modern languages. Such works naturally focus on the acquisition of vocabulary in the context of the language as a whole and include a focus on communication and speaking. Whilst such approaches can naturally be applied to the teaching and learning of Latin, this study aims to be of genuine use in the classroom and therefore regards Latin in the context in which it is typically taught and learnt in Britain today, namely, as a subject based predominantly on the reading of texts and examined in the same way. Elements from the approaches used in modern languages will therefore be of interest chiefly when they focus on acquisition of vocabulary for reading and comprehension.

Phonological memory

The importance of phonological memory in vocabulary learning has been the subject of research (Healy et al., Reference Healy and Bourne1998, p.151). This has been based around the role of the “phonological loop” in language learning: when learners are processing vocabulary, it is temporarily stored in their short-term phonological memory. This enables mental rehearsal of the new vocabulary item and thus retention.

The role of phonological short-term memory in vocabulary learning has various important implications. For example, studies have found that students find it easier to learn words from languages with phonological systems similar to their native language, or nonsense words with similar phonological patterns to their native language (Healy et al., Reference Healy and Bourne1998, p.155).

More crucially for this study, it implies that students with poor phonological short-term memory will find vocabulary learning more difficult (Healy et al., 1998, p.146). This study will therefore focus in particular on those strategies that focus on making semantic rather than phonological connections, so as to look at vocabulary learning strategies that can be accessible and successful for all students. This is in keeping with the recommendation in Nation (Reference Nation2001, p.42) that learners can overcome limitations on phonological memory by developing meaning-based association techniques rather than relying on phonological repetition.

Reading

It is often suggested that much vocabulary can be acquired simply by exposure through reading. Beck et al. (Reference Beck, McKeown and McCaslin1983) suggests that the context must be designed carefully such that conditions for optimal acquisition of vocabulary are met. Jessop (Reference Jessop2007, p.1), on the other hand, implies that this is not sufficient when she points out that words that have previously been encountered in the specially designed context of the Cambridge Latin Course have been forgotten when they next appear.

In order to acquire vocabulary through reading, two main things are required: effort and repetitions. Effort is necessary in that attention must be paid to new vocabulary and it must be actively noticed. For example, Hunt (2016, p.111) suggests that vocabulary can be embedded in lessons by picking out new vocabulary after a story has been read and discussing it. Nation (Reference Nation2001, p.236ff) indicates that only limited vocabulary will be learnt simply from reading and guessing from context and that this will have to be done extensively to gain significant new vocabulary knowledge. Repeated use of the target vocabulary, as can be found in specially constructed graded readers, is desirable.

That repetition of new vocabulary is needed for it to be retained is intuitively obvious. Hunt (2016, pp.118-120) offers a case study where a teacher makes use of a range of ways of repeating vocabulary in class. Nation (Reference Nation2001, p.81) observes that there are many factors affecting vocabulary acquisition and thus the correlation between number of repetitions and retention is only moderate. In particular, different students can tend to need more or fewer repetitions than the average. That said, studies indicate that the average learner might require about seven repetitions for the learning of a word (Nation, Reference Nation2001, p.81).

Production

Works on production in vocabulary learning are focused on the teaching of modern languages (Nation, Reference Nation2001, p.180). They particularly look at the productive use of vocabulary as part of learning where production is the end goal. Although production is not the primary goal of most Latin teaching and is therefore not the focus of this study, some authors have investigated how it might reinforce Latin vocabulary for receptive use. For example, Hannegan (Reference Hannegan2012, p.1) presents a case study in which pronouns are learnt through a range of oral activities. This activity has the advantages of being social and interactive; however, it is particularly suitable here because of the goal of teaching pronouns, which naturally fit well into a question and answer activity. It seems likely that it would be more challenging to achieve similarly thorough coverage of lower frequency vocabulary. Practitioners of ‘comprehensible input’ approaches to Latin teaching find that about four new vocabulary items may be learned in a lesson through the method of circling (Ramahlo, Reference Ramahlo2019; Patrick Reference Patrick2015). In this method, the ideology is that “Latin is not different” (Patrick, Reference Patrick2011, p.1) from other languages and should therefore be taught in the same: namely, that the focus should be on presenting students with information in the target language that they can understand and respond to. Anecdotally, such methods produce good results in terms of comprehension and motivation. However, it would be difficult to use this method as the basis of a traditional curriculum designed to prepare for a traditional examination, and success in national examinations has been limited (Patrick, Reference Patrick2015, p.117).

Keyword Method

The keyword method is a mnemonic method based in visual imagery which aims to circumvent the need for phonological memory. In traditional rote learning a link in phonological memory between the L2 word and the L1 definition is needed, for example contentus and satisfied. In the keyword method, the use of phonological memory is avoided by selection of an L1 keyword which has phonological similarity to the L2 word to be learnt. For example, in this case, we might use the keyword tent. A mental image is then constructed which links the L1 keyword to the L1 definition. In this example, the image might consist of a tent with a big satisfied grin on its face. When asked to recall the meaning of contentus, the student should find that they are prompted to consider this image and thereby remember the definition.

Strengths of the Keyword Method

The keyword technique has been found to be extremely effective (Condus et al., Reference Condus, Marshall and Miller1986; Mastropieri et al., Reference Mastropieri, Scruggs and Mushinski Fulk1990). Nation (Reference Nation2001, p.313) says that studies “generally show the keyword technique results in faster and more secure learning than other approaches”. This has been found to be the case for learners using it for both L1 and L2 vocabulary in a range of languages. It has been found to be suitable for learners across a wide age and attainment range, as well as those with learning difficulties (Condus et al., Reference Condus, Marshall and Miller1986; Mastropieri et al., Reference Mastropieri, Scruggs and Mushinski Fulk1990). It has also been found to be effective for both immediate and longer-term retention. Nation (Reference Nation2001, p.42) suggests that this effectiveness is in large part due to the fact that the keyword method does not rely on phonological associations.

Shortcomings of the Keyword Method

The keyword method is an inherently more complex technique than the learning of simple L1-L2 word pairs, as there is extra information to be remembered in the form of keyword and image. However, the technique is set up such that remembering these extra pieces of information should not be extra effort; indeed, it is rather the point of the method that these pieces of information should be recalled easily.

Potentially more troublesome is the suggestion that extensive training in use of the strategy is required for it to be used effectively. Nation (Reference Nation2001, p.314) emphasises the need for extensive strategy training and explains that, without this, it will be easier for the students not to bother using the strategy and thus there will be no advantage. He suggests that many of the studies on the keyword method have neglected this training. Wei (Reference Wei2015, p.50), however, suggests that this issue can be minimised by instructing participants in the study as to which images to use, therefore reducing the likelihood that struggles with the method will cause them to learn by some other strategy.

Mnemonic techniques such as the keyword method depend upon the direct correspondence of L1-L2 vocabulary pairs where one meaning is remembered for one form. This can be too simplistic. Gu (Reference Gu2003) explores some of these limitations, pointing out that meanings can be more complex than the keyword method allows for, and that no additional information about a word, for example grammatical information, is learnt through such strategies. These shortcomings are not of great concern for the learning of Latin at first year level, where simple synthetic texts are being read. Further, Nation (Reference Nation2001, p.313) suggests that extra information can be included in the keyword method, such as gender.

Studies suggest that the keyword method works well for some words and less well for others (Nation Reference Nation2001, p.314). Naturally, it is harder to use the method where it is difficult to find an appropriate keyword. Sometimes a high frequency L2 word might be used instead of an L1 word. Many studies have also found the keyword method to be less effective for abstract or ‘low-imagery’ words, as this renders the creation of a strong image linking the keyword and L1 word significantly harder. Wei (Reference Wei2015, p.48 and p.63) sets this out as a limitation of the keyword technique.

A further limitation of this method was suggested by Wei (Reference Wei2015, p.60ff) who found that it was less effective than self-strategy learning for Chinese students studying English vocabulary. The suggestion was made that this could be because of the limited phonological similarity between the languages and the fact that the Chinese students were not accustomed to a phonetic script. It was therefore difficult for them to grasp the phonological link between the L2 word and the keyword. They found themselves doing all the extra work involved to secure the additional pieces of information involved in this strategy compared to self-strategy learning, but without the phonological advantage.

Self-made mnemonics etc

Some studies have found that students create their own informal mnemonic-based learning strategies, particularly for difficult or abstract items of vocabulary. For example, one student in Jessop (Reference Jessop2007, p.20) used personification of tamen to allow her to visualise a story around this abstract word. One pupil in this study described a visualisation process which is very similar to the keyword method, where the meaning of Latin fur is remembered by visualising a thief stealing a fur coat.

Other Activities

Hunt (2016, p.112ff) explores the use of a number of other techniques in the classroom. For example, group work might include Total Physical Response, or students could be given a word and make progress around the classroom, teaching their words to one another. He particularly explores opportunities for visual ways of working with vocabulary, such as labelling of pictures, or the use of a ‘Pandora's box’ of Latin words. All of these approaches are based on the principle of doing something with the vocabulary to engage students in remembering it differently than by simply reading the words.

Motivation

Macaro (Reference Macaro2001, p.28) believes that motivation is of importance in the learning of vocabulary through strategies because strategy use is an inherently effortful process. However, little research has been done in this area so he reaches no firm conclusions as to whether it is the case that those students with less motivation put less effort into strategy use and therefore perform less well, or whether those who use strategies less successfully achieve less success and therefore become less motivated. He also implies (Macaro, Reference Macaro2001, p.38) that motivation might be particularly important in vocabulary learning because it is generally treated as an independent learning task that learners are expected to go away and work on in their own time.

Similarly, St. Clair Otten (Reference St. Clair Otten2003) found that motivation for independent study was a key factor in the learning of vocabulary, with only 20% of students in this study going away and studying their vocabulary outside of class. These students were therefore asked to work on a range of activities in class to target vocabulary, such as pair matching games and crosswords. The students were also introduced to the idea of offering a piece of paper with an anonymous explanation of why they had not done better in a vocabulary test they had not studied for, a measure that helps the teacher to understand the situation and encourages openness but without the students’ motivation being further reduced by fear of a reprimand.

Nation (Reference Nation2001, p.231) suggests a strategy which he refers to as “sharing with others”. It is suggested that an advantage of this method is the motivation that comes from the student sharing the word receiving the respect and attention of their peers and watching their peers add the word to their own list of words to learn. The social aspect of this approach could also aid in developing a whole class enthusiasm for vocabulary.

Strategy training

A great deal of the literature makes reference to the fact that strategies must be used correctly if they are to be effective; it is therefore necessary that both teachers and students undergo training. Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Hardy and Hardy2001) goes further and insists that the teacher must be trained through specific staff development on relevant topics such as psychological research and specifically information-processing. Naturally any technique requiring such specific additional training is unlikely to be practical for regular classroom use by the majority of teachers. Similarly, Nation (Reference Nation2001, p. 223) describes a number of steps that should be followed if students are to use a new strategy, with meta-learning of how to use the strategy being necessary before the strategy can be used. This outline has seven steps, of which the majority require use of lesson time.

Conclusions from the literature

A wide range of vocabulary learning strategies exist and have been studied to different extents. It is not possible to say that one of these is superior; because of the nature of this area of language learning, different methods have different strengths and weaknesses and are not directly comparable. In particular, different strategies appear to be more or less helpful for different learners. It is, however, possible to observe that some strategies, such as production/retrieval and the keyword method, have been found to be beneficial by the majority of studies.

Methodology

I put in place an intervention consisting of three different strategies to be used by the whole class in turn. These strategies would be fitted into the normal programme of learning half of a vocabulary checklist from the Cambridge Latin Course each week, in accordance with the school's scheme of learning. This was obviously necessary from an ethical point of view, in order that my study be to the educational detriment of no child. The methodology was approved by my mentor, head of department and the regular teacher of the class involved. No recordings were made and all students are anonymised.

Intervention 1: Presenting to Class

I chose this strategy because it combined the potential for students to explore a range of learning methods whilst completing a task that is motivating. It was based partly on an idea found in Nation (Reference Nation2001, p.231) of “sharing with others”.

Students were split into groups of two or three and allocated a word from the vocabulary list to be covered that week. They were instructed to prepare exactly one minute of material to teach their word to the class in any way they liked using only the simple resources of whiteboard, pen, and their own words and acting. I explained to them that their priority should be making their peers remember their word and its English translation. Those students who display confidence were allocated the words judged to be more challenging, for example those that were abstract or had no obvious etymological links to English.

The students were allowed to choose their own approach and encouraged to be imaginative and adventurous. Some broad suggestions were given; they might like to do rhyme of some kind, or some acting, for example. Other than this no direction was given. This meant I could examine the methods students chose to use. This approach was, therefore, partly chosen in order to see the manifestation of strategies such as those described in Jessop (Reference Jessop2007, pp.17-20).

This method was also chosen as a means to investigate what students find motivating. The method includes a social aspect through group work, and also avoids written work that students can find less motivating. There was also the avoidance of an immediate written test for this subsection, as this was replaced with viewing the presentations.

Intervention 2: Keyword Method

For this strategy, the words had to be the remainder of the vocabulary checklist for that chapter after the words suitable for strategy three had been removed, in order to keep pace with the scheme of learning. This meant that there was a combination of low-imagery and high-imagery words, but more high-imagery words because of the content of the textbook. It would therefore be possible to compare results for high- or low- imagery words to some extent.

I decided that the students should be told which keywords to use, to ensure that the study could fairly examine the effectiveness of the strategy rather than being disrupted by students’ struggles to find suitable keywords when using an unfamiliar method for the first time. Keywords were obviously selected to have phonetic similarity to the Latin word, but also where possible to create amusing and memorable images.

The method was introduced to the students and a sheet provided which gave the Latin word, English definition and keyword, together with a sentence describing the image to be visualised. Less instruction in the method was therefore given than many authors recommend, but I judged that this should be sufficient to attempt the task and that the amount of instruction was in keeping with the aims of the study to investigate what is practical within the constraints of normal classroom teaching.

Intervention 3: Completing Sentences

A story from the textbook was chosen which contained half the words on the vocabulary list for that chapter. This story was read in class, with attention directed towards the use of new vocabulary. A sheet was then provided on which there were sentences, based on the text, which had blank spaces for the vocabulary words to be targeted, with the English meaning in brackets to aid comprehension. The sentences were written such that the words were to be given in the same form as they were found in the text.

This strategy was chosen to investigate the learning of vocabulary through reading and production rather than deliberate learning. It was based partly on the ‘second-hand cloze’ activity in Nation (Reference Nation2001, p.107).

Data collection

Answers in vocabulary tests both before and after the intervention were recorded, primarily in order to observe qualitatively the patterns of correct, near-correct and incorrect answers rather than for the goal of extensive statistical analysis, which can have little use in such a small study. There are 22 students in the class, of whom 16 completed all parts of the study. The students were used to a regular routine and format of vocabulary testing after a vocabulary learning homework; this was largely followed during the study, although questions targeting aspects of accidence, which the students typically had within vocabulary tests, were omitted. This was done in order to prevent situations where students who did not know the answer to the accidence aspect of the question did not include useful vocabulary information they did know; examination of prior tests had revealed that students found these questions particularly difficult and were prone to get much lower marks on them than simple definition of vocabulary. Of course, it could be argued that their ability to identify vocabulary in such contexts is a far more useful measure of their ability to identify vocabulary when reading a continuous passage, but such questions fall outside the scope of this study.

Information about the students’ ability to recall vocabulary learned with these strategies when reading Latin is instead provided by my observations of occasions when these words appeared in lessons, as naturally happened quite often because of the structure of the Cambridge Latin Course. This is of course the least thorough aspect of the study, as it is simply not possible for the teacher to record every incidence of the use of one of these items of vocabulary during a course of lessons. Very often the word was simply translated correctly and no evidence existed of whether the strategy had been instrumental in its recall. Where such observations are discussed, therefore, it is because classroom discussion has occurred that makes specific reference to the recent prior learning of a word by means of one of the intervention strategies.

The students were asked to fill in a questionnaire. All who were present consented to take part, and only a very few chose to remain anonymous, such that it was possible to observe correspondences between individual students’ answers in vocabulary tests and their opinions as stated in the questionnaire. The questionnaire was short and consisted mainly of simple multiple-choice questions with some space at the end to give any further relevant thoughts. This method of data collection was chosen to gather information from as many students as possible. It also had the benefit of preserving anonymity where students desired it, making honest responses more likely. A combination of closed and open questions was included to gather as much useful data as possible (Wilson, Reference Wilson2013, p.115).

For the strategy that consisted of presenting to the class, data also include both my observation notes and those of the more experienced regular class teacher. For the strategy that consisted of completing the sentences, the worksheet of sentences was collected in for marking and the relationship between correct answers on this sheet and in the vocabulary test was observed.

Data as to the practicality of the strategies are based on my records of time and resources used, as well as evidence of the students’ ability to undertake the learning activity successfully and without undue confusion, such as their feedback in the questionnaire and any noticeable common patterns of error.

Overall, data collection methods were chosen to be as unobtrusive as possible and with little departure from the normal atmosphere of the classroom to minimise the extent to which students would behave differently because of unusual circumstances (Wilson, Reference Wilson2013, p.115).

Results and Analysis

Self study

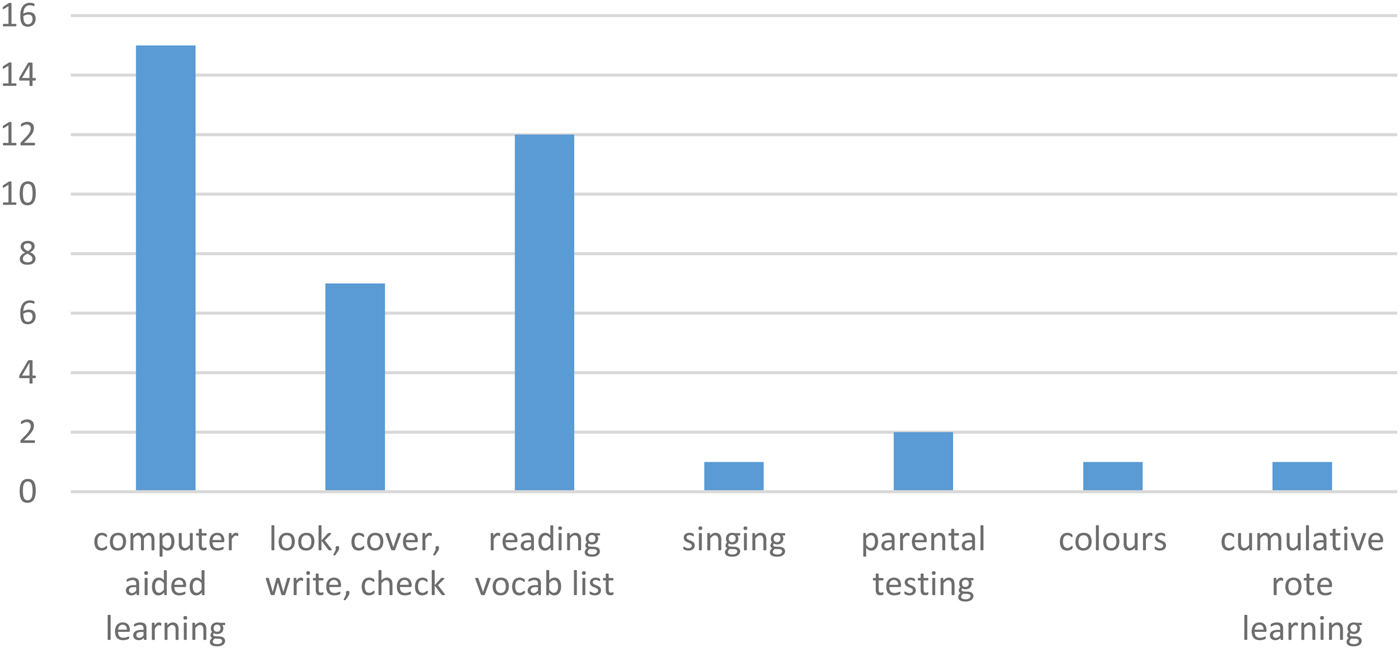

The first part of the questionnaire asked about students’ normal method of learning vocabulary (see figure 1). They were asked to tick all that apply to them, so many students listed more than one method. The most popular were traditional rote-learning based methods, with reading the words being listed by 12 respondents and look, cover, write, check being listed by seven. One student also described a cumulative rote learning approach. This therefore indicates that the students predominantly learn vocabulary using these methods which rely on phonological memory and that the strategies introduced in the intervention would be different to what they were used to. Indeed, a small minority of students appear to have disregarded the strategy instruction provided in the intervention and continued with their preferred method, with one student admitting as much in the questionnaire. Whilst students making radical departures from the strategies would obviously harm the integrity of any serious attempt at statistical analysis of the fluctuation in scores on vocabulary tests, in this study I did not think it was of any great concern; such a study was too small to make any conclusions based on statistics that could be generalised more widely anyway, and if nothing else, something has been learnt about the motivations and attitudes of students when it comes to vocabulary learning; those who have a successful method may not like to be challenged to try something new!

Fig. 1. | Students’ usual vocabulary learning methods

A sizeable number of students also used computer-aided methods, with two using quizlet, eight using memrise, and five using the Cambridge Latin Course vocabulary tester. These all work on an algorithm that assesses which words students find most difficult and tests these more often. Apps such as memrise also send a reminder to users to review vocabulary frequently. Fundamentally, such software bases its success on frequent exposure to the vocabulary items and motivation, but encourages similar learning methods (i.e. simple repetition) to rote learning. This, then, is also in contrast to the strategies introduced in the intervention.

A very small minority of students listed an approach that was not based on repetition and rote learning. For example, one student indicated that he made use of colour to write out the items to be learnt in a way that was visually memorable.

In general, then, the analysis of the relative usefulness of any of the strategies introduced in the intervention compared to the students’ normal methods will mean comparing them to rote-learning based methods.

Presenting to Class

The students undertook this task with great enthusiasm and effort. Every group had clearly spent time considering the task and presented something original. It was fascinating to observe that they had, independently of any instruction, often thought of ideas that show elements of one or more of the strategies explored in the literature review above.

Three groups used elements of the keyword method. For example, one group made ostendit memorable by using the keyword “ostrich”. They used the following phrasing (their emphasis):

“Ostendit sounds like ostrich and an ostrich has a really long neck because it wants to show you its head.”

Other groups using elements of the keyword method similarly made use of emphasis and rhythmic speech alongside it to render their presentations more memorable.

Six groups made use of etymology or word relationships. For example, one group showed how the word revenit is composed of word elements the class already know, namely re and venit, and how combining these two meanings gave the new word.

The students presenting iterum walked backwards and forwards again and again repeating the word. This had elements of total physical response for the students participating, and was a strong visual image for those watching.

The vast majority of the groups made a clear attempt to use humour to make their word memorable in addition to any techniques described above. For example, one group combined humour with the keyword method by saying:

“pulcher sounds like vulture and a vulture eating [friend and classmate] would be a beautiful sight.”

It was interesting to note that such varied and inventive presentations were given, often involving elements of various different strategies, in light of the information given in the questionnaire that indicated that students typically used rote learning or computer software. This was especially fascinating given how much the students clearly enjoyed these more imaginative ways of learning words. It seems likely that the reason why students do not learn in this way more often is simply one of effort; students repeatedly reading the vocabulary list in the text book during form time on the morning of a test is a common sight, and clearly any attempt to learn in a more imaginative way would be more effortful and time-consuming.

Effectiveness

11 of the 20 students answering the questionnaire answered “yes” to the question “Did you find [presenting vocabulary to the class] helped you learn?” This is a higher proportion of students claiming to find the method helpful than any other strategy. Only three students answered with an outright no to this question, with the rest being unsure. Seven students found that this was an improvement over their normal method of learning vocabulary, with nine saying that it was not.

The vocabulary test scores of this class are in general good, with a minority of students who consistently score low marks in such tests. This intervention did not make a significant difference to the marks in tests across the class as a whole. It was, however, noticeable from conversation and observation that the mnemonics and other such memorable presentations of their peers were effective memory cues when meeting words in texts. For example, when a student is having difficulty remembering the word ostendit, the class now enthusiastically respond to the prompt the presentation group used (ostrich) and consistently use this to recall the correct word. In the vocabulary test administered after use of this strategy, it is apparent that some of the particularly interesting or memorable presentations had made an impression even on those students who generally get particularly low marks in vocabulary tests. For example, the two lowest scoring students in this test did both give a correct answer for ostendit.

This strategy performed relatively well in the post test, considering the significant decrease in marks overall after four weeks. In particular, it is worthy of note that all but one of the students who presented a word and then took part in the post test remembered the word they themselves had presented. This indicates that the effort put into making the word memorable for others and presenting in this context had a beneficial effect on retention of words over a longer time period.

Amongst those words from the presenting to the class strategy that were widely remembered even by those who had not presented them were unsurprisingly those that had been the most memorable to begin with. For example, post was remembered by every student except one, and this is a word that might be expected to be memorable because of its common use in Latin phrases adopted into English. However, some words which might be judged as being less memorable, i.e. with no obvious etymological link to English or use in common phrases, also performed well here. For example, all but two students correctly translated pulcher. Where words such as this were well-remembered they were generally those featured in particularly memorable presentations. It is therefore apparent that a good presentation can make this a very effective method even for less memorable words. If this method were used again, it seems likely that the students would continue to become more practised and this would make the presentations better and therefore the method more effective.

Enjoyment

Unsurprisingly, given the social aspect of this activity and the use of humour, this was by far the most enjoyed of the strategies according to the questionnaire responses. Only one student answered “no” to the question “Did you enjoy this?” It should be noted that this student receives learning support for ASD. He agreed to take part and took quite a simple role, but this indicates that a teacher using this method should be aware of any students who might be uncomfortable with performing. Both the more experienced teacher who was observing and I agreed that a particular merit of this strategy was that every group can choose to do a presentation all group members are comfortable with and everyone can choose a role which suits them. For example, some students chose to take a non-speaking role and write on the board, whereas others acted or chose a role with more speech.

This task was also inherently motivating for the students in as much as they did not wish to appear foolish in front of their peers by having prepared nothing interesting when all their friends had prepared such humorous presentations. They therefore all completed the task with rather more care than it would appear many of them regularly spend on vocabulary learning homework. Further, they were all present to watch their peers and engaged with their presentations, meaning every student was exposed to every word. This, too, made it an effective strategy for targeting particularly disengaged pupils who do not learn vocabulary independently.

There is evidence that the use of differentiation in allocating the words was appreciated and aided motivation. Some of the more vocal and engaged members of the class were given words judged to be difficult and responded well. For example, the students who were asked to present mox immediately noted that it would be tricky because of the lack of English cognates and because it is abstract, but prepared an excellent presentation where mox was rendered memorable by three different keywords and with much use of rhyme. Conversely, students who were identified as lower attainment and in particular less confident performed well because they were able easily to find ideas for their word. For example, one of the students working on post said the activity “helped” and the choice of word was good in that it was responsible for “making it easy” to take part.

Practicality

This strategy required very little preparation time on the part of the teacher as all that was needed was to select the words for that week and allot them to groups, with a little attention to differentiation.

No more class or homework time was needed than for a typical vocabulary homework, as it was decided that the presentation of words would replace the small sub-test the students are used to receiving straight after a vocabulary learning homework, and the preparation of presentations would take place in the normal vocabulary learning time allocation.

Overall impact of strategy

This strategy was motivating for the students and convenient for the teacher. In terms of impact on retention of vocabulary, there is evidence that it did have some positive impact. This was particularly evident where a good presentation was given that was remembered by the class, and of course in students remembering their own presented word. It is to be hoped that if this strategy were used often the students would become more confident in taking part and more experienced in identifying what makes for a successful presentation. It will certainly be used with this class again!

Keyword Method

The students were attentive when the process was being explained and gave every appearance of understanding the task. Their reactions when the keywords and images were introduced also indicated that they noticed and appreciated the attempts to make the images amusing and engaging.

Unlike the other two strategies explored in this study, the keyword method did not produce direct evidence that students had undertaken the task in quite the same way. However, it is apparent from their comments that at least some attempt to use the prescribed technique was made by the vast majority of students. A minority of students did present concrete evidence of having made use of the sheet provided to undertake the task in that they had used colour to add emphasis and to colour code keywords and target vocabulary.

Effectiveness

Five students said this did help them to learn, eight said it did not, and five were unsure. Two abstained on the grounds of absence for part of the time we spent working on this strategy. When asked if it was more helpful than their normal method, the class as a whole disagreed, with 14 saying it was not and only two saying it was. These two students consistently perform well in vocabulary tests and were very positive about trying the new strategies in general. It would appear that the class as a whole was somewhat ambivalent about the usefulness of the keyword method according to the questionnaire responses.

This is interesting given this method did seem to have a noticeable effect on the scores in vocabulary tests. 11 students scored full marks in this test; whilst these students were mostly those who tend to score well, this is still unusual and worthy of note, and many others came very close to this. What is more interesting, however, is the improvement amongst those students who normally score lower marks. For example, one student who had been causing concern because he seemed to be working hard but scoring poorly answered every question except one of this vocabulary test correctly. This student was also receiving learning support for literacy difficulties. When he found out about the improved mark, he was pleasantly surprised, because he had not particularly felt the method to be helpful, but it had clearly resulted in a much better mark. Although the improvement is much less dramatic, the two students in this class who consistently struggle the most in Latin also had some improvement using the keyword method. Here, however, it seems less likely that the improvement is down to the method itself but due to the change in approach and motivation that is caused by giving a worksheet with clear instructions and a different format for a vocabulary homework, rather than simply a list. Of course, if this change of format in itself improves motivation that is noteworthy. Further, the worksheet was read through together in class when setting the task to ensure everyone understood; this naturally was further exposure to the words for any students who do not typically go home and learn the vocabulary.

A very small number of incorrect answers showed confusion of the keyword and the required answer, for example “ox” for uxor.

There was no significant difference in test performance between concrete or high-imagery words and those that were less so. The majority of the words happened to be relatively easy to visualise because of the nature of Book One of the Cambridge Latin Course.

In the post-test, marks were in general lower than they had been immediately after learning. However, the student who had been particularly identified in the initial test as benefiting from the keyword method also performed well in this area of the post-test, still remembering 11 of these words, compared with much lower marks in the other strategies. There was also other evidence of the keyword method being of use to the students. For example, one had underlined the keyword lid within the word callidus in the post-test.

Confusion was more noticeable in the post-test than it had been in the initial test of the keyword method, with one student writing keeper for accipit and with a number of students misidentifying portus as being porto (“carry”) or similar.

The words that were most successfully remembered amongst those for which the keyword method had been used were nos and vos. These words had, being pronouns, also been used extensively in reading in class since being learned, further reinforcing their meaning.

Enjoyment

Students were split almost evenly between enjoying it, not enjoying it, and neither. Many students chose to expand upon this in the comments section, saying things such as “I think the keyword just confused me”. There was, however, relatively little evidence of this in the test results. Students appreciated the attempts to produce humorous and memorable keywords and images.

Practicality

This required significant teacher planning time, although this would be reduced significantly if students used their own keywords. However, it seems unlikely that asking students to choose their own keywords would be practical unless significantly more practice of the strategy had been done first; asking for this at an early stage would surely increase confusion and render the task sufficiently time-consuming and difficult as to be less than motivating for the students.

The task required only a little class time to explain and then to test as normal, and was undertaken in a standard homework allocation.

Overall impact of strategy

This strategy suited some students far better than others, with some seeing significant improvement and others claiming to be confused. This was further confirmed by the post-test results. Although the potential for confusion and the limited use for most students, combined with the preparation on the part of the teacher, make it unlikely that this strategy would be a contender for regular use with a whole class, there is clearly a great deal of merit in ensuring that students who might find it valuable are equipped with the knowledge of how to use it. It may also prove particularly useful to create class mnemonics for words that are particularly difficult to remember, as for example has happened with ostendit.

Two months after this strategy was introduced, the students began revising for internal school exams. Four students, without prompting, showed me mnemonic sentences based on the keyword method that they had created as part of their revision for this, or expressed the intention of making this a key part of their revision. When I discussed with one student who was falling particularly behind with vocabulary what he might do about this, he volunteered that he thought this strategy would help him and has since presented a great deal of evidence of creating keywords. This has resulted in a great improvement in his vocabulary knowledge, and consequently even greater improvement in his motivation and participation in lessons. Clearly these students have benefited from being equipped with this strategy.

Completing Sentences

Only just over half of the class had stuck the sentences in their books as instructed, so at the time of writing the body of evidence for how the students approached this task is rather small. All of these students had followed the instructions to put Latin words in the space provided, although a minority had left blank spaces where they were unsure. Ten of the students gave the correct lexical item for every space, although often in an incorrect grammatical form. Often the form in which they had given the word was that used in the vocabulary list in the textbook, indicating they might have taken the words from here rather than reading through the story as instructed. Two students left blank spaces or gave the wrong item of vocabulary.

Effectiveness

Only two students’ questionnaire responses indicated that they found this helpful, and no student felt that this was more useful than their normal method. Nine found that it was not helpful. Surprisingly, when asked at the end of the questionnaire to list any methods they would use again, five students listed completing sentences. However, this seems to be more down to the structure of the questionnaire than positive feelings about this method, as the students seem in general to have been far more generous in this question than throughout the rest of the questionnaire.

These vocabulary test results were rather poor, with many students who typically perform well struggling. It had been hoped that the method might be effective for those students who do not typically learn vocabulary at home because there was a written worksheet to complete and they were aware that the teacher would mark this. However, these students also underperformed compared to their typical marks.

There did not appear to be a relationship between correct answers in completing the sentences and in the vocabulary test. For example, one student who identified all the correct items of vocabulary when completing the sentences scored only three correct answers in the vocabulary test. Conversely, one student who left multiple blank spaces and scored only six on the sheet of sentences scored eight on the vocabulary test with two more answers that were near-correct, although based on her results and comments throughout the study it seems likely that she may actually have used her own study technique here rather than relying on the sentences task.

Words learnt through the completing sentences task were worst remembered in the post- test, which is hardly surprising given so many of them had not really been known in the first place. Students struggled particularly with grammar words such as quam, which I had hoped might particularly benefit from being learnt in a sentence context.

Enjoyment

Only two students stated that they had enjoyed using this method. Even one student who said he had found it helpful said in the comments section that it was useful but not enjoyable. By contrast seven said they had not enjoyed it, which is more than said this of any other strategy in this study. It is therefore clear that this was not a strategy the students found motivating from an enjoyment point of view. Some were motivated by a sense of duty to complete written work, but this does not seem to be the best way to go about motivating students who are discouraged with vocabulary learning.

Practicality

This required forward planning on the part of the teacher, examining the textbook several weeks ahead to find a suitable passage where a good number of words on the vocabulary checklist were introduced in one story. However, it took no lesson time apart from that to administer a standard vocabulary test, and used one homework allocation.

Students understood what the task was in as much as they understood that they had to write the correct Latin word in the space. However, this seemed to fluster many even though they have a workbook for the writing of Latin which is regularly used. Many gave an incorrect grammatical form, which, although not such a concern where the target is vocabulary, was nonetheless alarming given they are used to doing a certain amount of prose composition and the words were in the same form in the text as they should be in the sentences. Some ignored the text and looked up different words in a dictionary. This was a rather unexpected problem given that the words had been chosen deliberately to appear in identical forms in the text and in the sentences.

Overall impact of strategy

The only real positive to be found for this strategy is in the fact that a written activity on a sheet to be submitted for marking could be a motivator for certain students to interact with the vocabulary when they otherwise would not. Other than that, it would appear that this strategy was fairly accurately summarised by one student who said “the sentences were terrible”.

However, elements of this can certainly usefully be incorporated into classroom practice. A certain amount of prose composition is included in the scheme of work for these students; having conducted this study, it seems the natural conclusion that the practising of target vocabulary items by including them in prose composition exercises would be an effective way of increasing exposure to new vocabulary for those students who will complete written tasks but seem to regard the learning of vocabulary as “not real homework”. It is to be hoped that, by incorporating vocabulary into the familiar setting of their prose composition work, the flustered use of wrong words that occurred with this rather unfamiliar activity might be reduced.

Conclusions

Without doubt, the strategy that the students found most motivating was that of presenting to the class. This was both intrinsically enjoyable and had the incentive of students wishing to prepare material they were proud of to present to their peers. However, the other two methods also had something to contribute in motivating students to learn vocabulary. Some enjoyed the keyword method, and the majority completed the sheet of sentences and submitted it for marking, ensuring that some of those who are reluctant to learn vocabulary had interacted with the words to some extent. As far as student motivation is concerned, it can be concluded that the activity that included novelty and a sociable aspect was successful, but that any move away from simply giving students a list of words and the instruction to learn had some impact.

In terms of practicality, the completing sentences task was the least practical, requiring a suitable passage to be available during the course of ordinary lessons and significant teacher planning. This impracticality seems to outweigh the usefulness of the strategy.

Different strategies were effective for different students. Presenting to the class was almost universally successful in encouraging retention of the students’ own presented word. However, the extent to which students learned from the presentations of others depended very much upon the quality of those presentations. The keyword method was of little use to the majority and actively confusing to a few, but of noticeable benefit to a minority of students who often struggle particularly with vocabulary learning.

In conclusion, the only strategy I do not intend to make use of in this format in my teaching is that of completing sentences. The other two strategies both have much to recommend them. Presenting to the class was a successful way of getting every student involved in and excited about vocabulary learning, while the keyword method was of particular benefit to some individuals. Overall, it is apparent when viewing the results of the intervention strategies and the students’ own approaches that successful vocabulary learning is best achieved when students are equipped with a range of strategies, and motivation is maintained by presenting the task of vocabulary learning in novel and engaging ways.