I Introduction

The export-oriented ready-made garments (RMG) sector in Bangladesh has registered a remarkable expansion over the past four decades. From a small base of only around US$ 31 million in 1984, RMG exports had grown to around US$ 30.6 billion by 2018,Footnote 1 accounting for more than 80% of export earnings. Bangladesh is now the second largest exporter of RMG in the world. The story of growth in the manufacturing sector in Bangladesh over the past three decades has been the story of the success of the RMG sector.

It is argued that the growth in exports of the RMG sector in Bangladesh have contributed to economic growth, macroeconomic stability, employment generation (especially female employment), and poverty alleviation. However, despite the successes, there are a number of challenges which raise concerns over the future of this sector. First, with the expansion of the RMG sector in Bangladesh, the export basket has become more and more concentrated. Though Bangladesh has potential in other export-oriented sectors, industries in those sectors have experienced very weak performance. With a highly concentrated export basket and high dependence on a single sector (RMG), Bangladesh remains in a high-risk situation, should there be any negative shock in that sector. Second, the factors that contributed to the growth of the RMG sector are now under pressure. Historically, the RMG sector in Bangladesh flourished for a number of reasons, including favourable policies, government support, and a number of critical political economy factors, which include the generation of sizeable ‘rents’ in this sector through the Multifibre Arrangement (MFA) quotaFootnote 2 (which no longer exists) and the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP)Footnote 3; different forms of subsidies; tax exemptions; the maintenance of a suppressed labour regime; weak factory compliance; and lawful and unlawful businesses relating to RMG by-products. However, the RMG sector in Bangladesh is now facing many challenges with respect to working conditions, labour unrest, technological upgrading and associated employment loss, stiff competition from competitor countries, and pressure from international buyers related to improvement on compliance issues. Third, Bangladesh will graduate from least developed country (LDC) status by 2024, whereupon it will face the challenge of the erosion of preferences in major export destinations, and thus the risk of export loss, especially the loss of RMG exports. Also, the country is seeking to expand its manufacturing base substantially and aims to become an upper middle-income country by 2031. Given these challenges, the fundamental question is whether the ‘RMG-centric’ export model is sustainable.

Therefore, there are genuine reasons to argue that there is a need for a major departure from the ‘RMG-centric’ export model and that the export basket in Bangladesh needs to be diversified. It is argued that export diversification in developing countries like Bangladesh is a necessary condition for sustained and long-term growth of the economy, and for job creation (Ghosh and Ostry, Reference Ghosh and Ostry1994; Bleaney and Greenaway, Reference Bleaney and Greenaway2001; Bertinelli et al., Reference Bertinelli, Salins and Strobl2006; di Giovanni and Levchenko, Reference di Giovanni and Levchenko2006; Hausmann et al., Reference Hausmann, Hwang and Rodrik2007; Hausmann and Klinger, Reference Hausmann and Klinger2006; Hwang, Reference Hwang2006). The current ‘global value chains’ discourse also highlights the importance of export diversification for effective integration into global value chains. While Bangladesh has been able to move away from agricultural exports to manufacturing exports, its export basket still remains highly concentrated around a few low-value manufacturing sector, especially the RMG sector (Mirdha, Reference Mirdha2018). For Bangladesh, it is argued that export diversification will be important for the long-term structural transformation of the economy with respect to shifting from the production of low-value products to high-value products. The long-term structural transformation of the economy requires production to be diversified and complexified, through which transferrable skills and capabilities will be acquired and linkages between sectors will be developed. Such a transformation will help to mitigate the impact of shocks on Bangladesh’s economy. However, despite the fact that export diversification has been an important policy agenda in Bangladesh over the past few decades, the country has achieved limited success in this area. In this context, there is a need to evaluate the so-called ‘RMG model’ of export success.

Against this backdrop, this chapter explores the institutional challenges of export diversification in Bangladesh in the context of the dominant RMG sector. Understanding the reasons behind the lack of success in the diversification of the export basket in Bangladesh requires a better grasp of the critical political economy factors. The major objectives of this chapter are to: (i) evaluate the features of the ‘RMG model’ of export success, and explore the dynamics of the institutional space around the RMG sector in Bangladesh; (ii) understand the sustainability of the ‘RMG-centric’ export model as far as the domestic and global scenarios and the bigger development goals of the country are concerned; and (iii) evaluate the challenges of export diversification in Bangladesh in the context of the dominant RMG sector. This chapter uses available data, conducts, and assesses interviews with key stakeholders to gather their views on institutional challenges related to export diversification and applies relevant political economy analytical tools to understand the successes of and the challenges faced by the RMG sector and the institutional challenges of export diversification in Bangladesh.

II Review of the Literature on Export Diversification

While the importance of export-led growth is generally acknowledged in the empirical literature, it is also commonly highlighted that a large number of developing countries are dependent on a relatively small range of export products. Countries that are commodity-dependent or have a narrow export basket usually face export instability, which arises from unstable global demand. Therefore, studies indicate the need for diversification of the export basket. Ghosh and Ostry (Reference Ghosh and Ostry1994) and Bleaney and Greenaway (Reference Bleaney and Greenaway2001) argued that export diversification usually refers to the move from ‘traditional’ to ‘non-traditional’ exports and can help to stabilise export earnings in the longer run. A diversified bundle of export products provides a hedge against price variations and shocks in specific product markets (Bertinelli et al., Reference Bertinelli, Salins and Strobl2006; di Giovanni and Levchenko, Reference di Giovanni and Levchenko2006). The type of products exported might affect economic growth and the potential for structural change (Hausmann et al., Reference Hausmann, Hwang and Rodrik2007; Hausmann and Klinger, Reference Hausmann and Klinger2006; Hwang, Reference Hwang2006). Diversification provides opportunities to extend investment risks over a wider portfolio of economic sectors, which eventually increases income (Love, Reference Love1986; Acemoglu and Zilibotti Reference Acemoglu and Zilibotti1997; Al-Marhubi, Reference Al-Marhubi2000; Hausmann and Rodrik, Reference Hausmann and Rodrik2003; Hausmann et al., Reference Hausmann, Hwang and Rodrik2007; Hausmann and Klinger, Reference Hausmann and Klinger2006).

There are several channels through which diversification may influence growth. It is therefore essential to make a distinction between horizontal and vertical diversification. Both are positively related to economic growth. Horizontal diversification means the alteration of the primary export mix in order to neutralise the volatility of global commodity prices. Horizontal export diversification benefits an economy by diminishing dependence on a narrow range of commodities that are subject to major price and volume fluctuations. Dawe (Reference Dawe1996) and Bleaney and Greenaway (Reference Bleaney and Greenaway2001) argued that horizontal export diversification may present considerable development benefits as it may lead to well-directed economic planning and also contribute towards investment. Vertical export diversification, on the other hand, refers to finding further uses for existing products or developing new innovations using value-adding activities, such as processing and marketing. By highlighting the role of increasing returns to scale and dynamic spill-over effects, de Piñeres and Ferrantino (Reference de Piñeres and Ferrantino2000) argued that export diversification affects long-run growth. Export may benefit economic growth through generating positive externalities on non-exports (Feder, Reference Feder1983), increased scale economies, improved allocative efficiency and better ability to produce dynamic comparative advantage (Sharma and Panagiotidis, Reference Sharma and Panagiotidis2004). Studies using regressions on cross-sections of countries (Sachs and Warner, Reference Sachs and Warner1995; Gylfason, Reference Gylfason2004; Feenstra and Kee, Reference Feenstra and Kee2004; Agosin, Reference Agosin2007) and panels (de Ferranti et al., Reference de Ferranti, Perry, Lederman and Maloney2002) have proposed that export concentration is associated with slow growth.

The review of the aforementioned literature suggests that though many of the aforementioned cross-country papers suffer from endogeneity problems, as growth also implies structural changes, which, in turn, trigger changes in the composition of exports, economic growth, and its long-term sustainability in developing countries are associated with the diversification of the export structure. Bangladesh, with a highly concentrated export basket, needs to align its efforts for export diversification with strategies for accelerating and sustaining economic growth. As Hausmann and Rodrik (Reference Hausmann and Rodrik2003) argued, there are various uncertainties related to cost in the production of new goods, and therefore, the Government should promote industrial growth and structural transformation by encouraging entrepreneurship, solving information problems to do with innovation, providing infrastructure and other public goods, and providing incentives to motivate entrepreneurs to invest in a new range of activities.

III Overview of the RMG and Overall Export Sector in Bangladesh

The textile and apparel industry is the gateway for many developing countries to enter into the process of industrialisation. The ease of entry into this field and the high wages in developed countries have created favourable conditions for the manufacturing and exportation of textile- and apparel-derived products (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Traore and Warfield2006). There are two reasons behind this: firstly, textiles and apparel are basic items of consumption for all people; and secondly, apparel manufacture is labour-intensive and requires relatively little fixed capital, but it can create substantial employment opportunities. The Asia-Pacific region has become one of the most competitive regions in textile and apparel manufacturing; approximately 50% of textile and apparel products are exported from this region (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Traore and Warfield2006).

RMG exports from Bangladesh have seen a remarkable rise over the past three and half decades. In 1983/84, RMG exports were insignificant, but by 2017/18, they had increased to US$ 30.6 billion. Riding on the growth of RMG exports, the country’s total exports of goods and services also saw a significant rise over the same period, from US$ 0.8 billion to US$ 36.7 billion.Footnote 4

The share of RMG in total exports increased from only 3.9% in 1983/84 to as high as 83.5% in 2017/18. Thus, in recent years, the export basket has become more and more concentrated around RMG exports. It also follows that, despite the impressive economic growth record, the export base and export markets have remained rather narrow for Bangladesh, which is a matter of concern. Despite the policy reforms and various incentives offered, it seems that Bangladesh has failed to develop a diversified export structure.

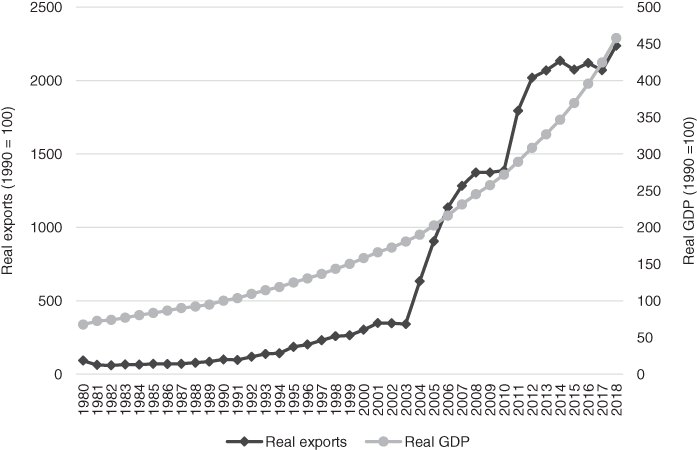

Figure 4.1 presents the evolution of real exports and real GDP considering 1990 as 100. There were two surges: one that followed the end of the MFA in 2004 and one after the global financial crisis in 2008. There has been a rather long stagnation since 2012. There are many reasons for the stagnation in recent years, which include both the demand- and supply-side challenges (which are discussed in Section V). It is also noticeable that the stagnation of export growth since 2012 did not prevent GDP from growing relatively rapidly.Footnote 5 However, it should be mentioned that exports represent around 15% of GDP, and less in value-added.

Figure 4.1 The evolution of exports and GDP in real terms (1990 = 100).

Bangladesh’s export concentrationFootnote 6 is higher than that of any other country groups. The comparable country groups are LDCs, lower middle-income countries, upper middle-income countries, high-income countries, and countries in South Asia. UNCTAD’s export concentration indicesFootnote 7 show that the marked differences in export concentration between Bangladesh and those of other country groups are noteworthy. Also, one important point to note here is that while other country groups have, in general, experienced declining export concentration indices, Bangladesh’s export concentration indices increased during the period between 1995 and 2016.

A close examination of the composition of the export baskets of Bangladesh and its major competitors, that is China, India, and Vietnam suggests that while Bangladesh’s export basket is highly concentrated around RMG, those of China, India, and Vietnam are fairly diversified.Footnote 8 The higher export concentration in Bangladesh is driven not only by the strong performance of RMG exports but also by the very weak performance of non-RMG exports. The performance of RMG exports since the early 1980s, and especially since 2003, has been quite remarkable.

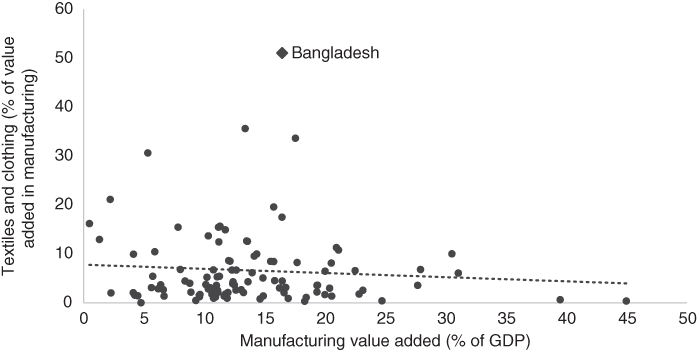

It is also important to note that Bangladesh appears to be an outlier with respect to the share of textiles and clothing in manufacturing value-added. The data for 109 countries from the World Development Indicators of World Bank suggest that Bangladesh has the highest share of textiles and clothing in manufacturing value-added, more than 50%, where the 95th percentile is around 20%. Bangladesh also appears to be a major outlier in the association between textiles and clothing share in manufacturing value-added and manufacturing share in GDP (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Bangladesh appears to be a major outlier in the association between textiles and clothing share in manufacturing and manufacturing share in GDP.

Note: Average for 2011–2016.

2011 was an important year due to the change in the double-transformation rule of the European Union (EU) for textiles and apparel (more than 60% of Bangladesh’s RMG exports are exported to the EU) to a single Rules of Origin (ROO) for LDCs. The double-transformation for clothing means that at least two substantial stages of production need to be carried out to confer origin status. For textiles, generally spinning and weaving needs to take place. For clothing, the weaving of fabric and making up into clothing needs to take place (European Commission, 2019). In the textiles and clothing sector, single-stage processing (manufacturing from fabric) has been allowed since 2011, in place of the previous two-stage one (manufacturing from yarn). Earlier, RMG exporters from Bangladesh, under the double-transformation rule, faced major difficulties in meeting the ROO criteria in the EU, due to the lack of supply of locally produced fabrics. In particular, a major part of the woven RMG exports from Bangladesh failed to access the duty-free market in the EU as they were unable to meet the double-transformation ROO.

The surge in exports over the past four decades also resulted in a rising export–GDP ratio. The export–GDP ratio was only around 5.7% in 1972 but increased to 15% in 2017. During this period, the import–GDP ratio also rose significantly, from only 13.7% to 20.3%. One important area of concern is that from 2011, both the export–GDP ratio and import–GDP ratio started to decline. Sluggish private investments is one of the major causes of the decline in the export–GDP ratio in Bangladesh.

The number of RMG factories in Bangladesh has increased quite remarkably since 1984/1985. While in 1984/1985, there were only 384 factories, the number had increased to 5,876 by 2012/2013. After the infamous Rana Plaza incident in 2013,Footnote 9 the number of RMG factories then declined sharply to 4,222 in 2013/2014. In 2017/2018, the number rose again to 4,560. Interviews with relevant stakeholders in the RMG industry suggest that the major structural change that is currently occurring in the RMG industry is the introduction of labour-saving machineries for the kind of jobs which were previously done mostly by low-skilled female workers. This has resulted in substantial gains in productivity in the RMG industry in recent years.

The composition of the RMG export products has also seen a major shift over the past decades. In the early years, the RMG exports from Bangladesh were predominantly woven RMG. In 1992/1993, more than 85% of RMG exports was woven RMG. Over the years, the share of knitwear has increased, and by 2017/2018, woven and knitwear had almost equal shares. The main RMG export items from Bangladesh are shirts, trousers, jackets, T-shirts, and sweaters. While in the initial years, shirts dominated, with more than 50% of the RMG export share, in recent years, the share of shirts has declined to less than 10%, while trousers and T-shirts have been major export items.

It is also important to note that Bangladesh’s RMG export markets are highly concentrated, with the EU and North America being the major destinations. In 2018, around 62.5% of the country’s RMG exports went to the EU, while another 21% was destined for North America. In Europe, the major destinations of Bangladesh’s RMG exports are Germany, the UK, Spain, and France. The major reason behind the EU becoming the dominant destination of RMG exports is the duty-free-quota-free (DFQF) market access in the EU market under the Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative for LDCs.Footnote 10

IV The ‘RMG Model’ of Export Success

A The MFA Regime

The development of Bangladesh’s RMG sector greatly benefited from the international trade regime in textiles and clothing, which, until 2004, was governed by the MFA quotas. In the global market, the quota system restricted competition, led to allocative inefficiency, and slowed the natural shift in comparative advantage from industrial countries to developing countries (Faini et al., Reference Faini, de Melo and Takacs1993). However, it created opportunities for countries like Bangladesh by providing reserved markets, where textiles and clothing items had not been traditional exports. Bangladesh, being an LDC, benefited from the MFA regime in a number of ways. In the EU, there were quotas on non-LDC exporters, but Bangladesh’s RMG items were allowed quota-free access (as well as duty-free treatment under the EU’s GSP scheme). In the US market, Bangladesh was allowed significant annual quota enhancement based on growth performance in the preceding year. This gave Bangladesh’s RMG exporters a secure market in the United States and also allowed them to gain from the quota-rent.Footnote 11

In 1995, the WTO’s Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) took over from the MFA. By 1 January 2005, the sector was fully integrated into normal GATT rules. In particular, the quotas came to an end, and importing countries were no longer able to discriminate between exporters. The ATC no longer exists: it is the only WTO agreement that had self-destruction built in to it.

B The Genesis of the RMG Industry in Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s RMG industry started its journey in the late 1970s, with the launch of the MFA. A handful of foreign companies, particularly the Korean companies Youngone and Daewoo, invested early in Bangladesh, bringing technical experience, marketing expertise, and a willingness to employ women. This was partly because South Korea had reached the limit of its MFA quota. Bangladesh’s middle managers and workers gained experience at Youngone and then, hired by other companies, spread their knowledge of operating an RMG business.

The late Nurool Quader Khan was the pioneer of the RMG industry in Bangladesh. In 1978, he sent 130 trainees to South Korea, where they learned how to produce RMG. With those trainees, he set up the first factory, Desh Garments, to produce garments for export. At the same time, the late Akhter Mohammad Musa of Bond Garments, the late Mohammad Reazuddin of Reaz Garments, Md. Humayun of Paris Garments, the engineer Mohammad Fazlul Azim of Azim Group, Major (Retd) Abdul Mannan of Sunman Group, M. Shamsur Rahman of Stylecraft Limited, and AM Subid Ali of Aristocrat Limited also came forward and established some of the first RMG factories in Bangladesh. Following in their footsteps, other entrepreneurs established RMG factories in the country.Footnote 12 These people were able to obtain major advantages from the Government, in the form of back to back letters of credit, bonded warehouses, and different forms of subsidies.

As mentioned before, the RMG sector has experienced an exponential growth since the early 1980s. The RMG sector was heavily promoted by all governments because of its remarkable economic performance, which contributed significantly to changing Bangladesh over the past four decades, from being an aid-dependent economy to being a trade-oriented economy.

C The RMG Industry Has Been the Major Beneficiary of Industry and Trade Policies and Export Incentives

After independence in 1971, the Government of Bangladesh nationalised all heavy industries, banks, and insurance companies. As a result of this mass nationalisation programme, by 1972 nationalised units accounted for 92% of the total fixed assets of the manufacturing sector in Bangladesh (Rahman, Reference Rahman and Helliner1994). Private sector participation was severely restricted to medium-sized, small, and cottage industries (Sobhan, Reference Sobhan1990). After the change in political power in 1975, the Government moved away from the nationalisation programme and revised the industrial policy with a view to facilitating a greater role for the private sector (Rahman, Reference Rahman and Helliner1994). Together with the denationalisation and privatisation process, these changing industrial policies led to a situation in which the major thrust was to support the growth of the private sector by amending the exclusive authority of the state in the economy (World Bank, 1989).

During the 1980s, the private sector development agenda became more prominent in industrial policies in Bangladesh. The successful outcome of these policies was the rapid growth of the RMG industry. The New Industrial Policy was put in place in 1982 and was further modified by the Revised Industrial Policy in 1986. These policies also aimed at accelerating the process of privatisation of public enterprises. All these policies involved providing substantial incentives and opportunities for private investment (Rahman, Reference Rahman and Helliner1994). Subsequent industrial policies re-emphasised the leading role of the private sector in the development of industries and clearly stated that the objective was to shift the role of the Government from a ‘regulatory’ authority to a ‘promotional’ entity. The industrial policies also encouraged domestic and foreign investment in the overall industrial development and stressed the importance of developing export-oriented industries.

Raihan and Razzaque (Reference Raihan and Razzaque2007) highlighted that an important element of trade policy reform in Bangladesh has been the use of a set of generous support and promotional measures for exports. These measures have primarily been directed to the RMG sector. While the import liberalisation was meant to correct the domestic incentive structure, in the form of reduced protection for import-substituting sectors, export promotion schemes were undertaken to provide exporters with an environment in which the previous bias against export-oriented investment could be reduced significantly. Important export incentive schemes available in Bangladesh include, among others: subsidised rates of interest on bank loans; duty-free import of machinery and intermediate inputs; cash subsidy; exemption from paying the value-added tax; and rebate on corporate income taxes. Box 4.1 summarises some of the most important incentive schemes that have been put in place in the country since the early 1980s, alongside the expansion of the RMG sector. With the significant reduction in tariff rates in the early 1990s, and the provision of generous support and promotional measures for exports, the anti-export bias declined quite significantly, which helped promote a surge in exports, especially RMG exports, during that period.Footnote 13

Box 4.1 Important export incentive schemes in Bangladesh, especially for RMG

Export Performance Benefit (XPB): This scheme was in operation from the mid-1970s to 1992. It allowed the exporters of non-traditional items to cash a certain proportion of their earnings (known as entitlements) at a higher exchange rate of the wage earner scheme (WESFootnote 1). In 1992, with the unification of the exchange rate system, the XPB scheme ceased.

Bonded warehouses: Exporters of manufactured goods are able to import raw materials and inputs without payment of duties and taxes. The raw materials and inputs are kept in bonded warehouses. On the submission of evidence of production for exports, a required amount of inputs is released from the warehouse. This facility is extended to exporters of RMG, specialised textiles (such as towels and socks), leather, ceramics, printed matter, and packaging materials, who are required to export at least 70% of their products.

Duty drawback: Exporters of manufactured products are given a refund of the customs duties and sales taxes paid on the imported raw materials that are used in the production of the goods exported. Exporters are exempted from paying value-added tax as they can obtain drawbacks on the value-added tax they have paid.

Duty-free import of machinery: Import of machineries without payment of any duties, for production in the export sectors.

Back-to-back letters of credits: Allows exporters to open letters of credit for the required import of raw materials against their export letters of credit in such sectors as RMG and leather goods. The system is considered to be one of the most important incentive schemes for the RMG export. Nurul Kader, the pioneer of the RMG industry in Bangladesh, was the inventor of back to back letters of credit.

Cash subsidy: The scheme was introduced in 1986. This facility is available mainly to exporters of textiles and clothing who choose not to use bonded warehouses or duty drawback facilities. Currently, the cash subsidy is 25% of the free on board export value. In recent times, cash subsidies have been offered to agro-product exporters.

Interest rate subsidy: Allows exporters to borrow from banks at lower bands of interest rates of 8–10%, as against the normal 14–16% charge.

Tax holiday: First introduced under the Industrial Policy of 1991–1993, this incentive allows a tax holiday for exporters, after the commencement of exports, for 5–12 years, depending on various conditions.

Income tax rebate: Exporters are given rebates on corporate income tax. Recently, this benefit has been increased: the advance income tax for exporters has been reduced from 0.50% of export receipts to 0.25%.

Retention of earnings in foreign currency: Exporters are now allowed to retain a portion of their export earnings in foreign currency. The entitlement varies in accordance with the local value addition in exportable. The maximum limit is 40% of total earnings, although for low value-added products such as RMG the current ceiling is only 7.5%.

Export credit guarantee scheme: Introduced in 1978 to insure loans in respect of export finance, it provides pre-shipment and post-shipment (and both) guarantee schemes. The principal risks covered include insolvency of the buyers and political restrictions delaying payment. The scheme was undertaken at the initiative of the Export Promotion Bureau and the ministries of commerce, industry, and finance. The scheme encourages exporters to initiate exports of new products and/or to enter new markets through covering the risk of insolvency of buyers and political risks inherent in foreign trade. The scheme also provides a guarantee for bank loans taken by the exporters to meet their financial needs during the production period and between exporting of goods and receiving payment from foreign buyers. Bangladeshi exporters can enjoy credit for a maturity of up to 180 days. Risks covered include insolvency and protracted default. Coverage percentages vary from 75% to 80% in the case of commercial risks, and 95% in the case of political risks.

Special facilities for export processing zones (EPZs)Footnote 2: To promote exports, a number of EPZs are currently in operation. The export units located in EPZs enjoy various other incentives, such as a tax holiday for 10 years, duty-free imports of spare parts, and exemption from value-added taxes and other duties. The major exports from EPZs are RMG.

A close scrutiny of the performance of sectors, apart from RMG, and consultation with the stakeholders of non-RMG sectors, reveal that many of these sectors, though classified as ‘thrust or priority sectors’ in the industrial and export policies, were not able to enjoy the incentives provided in these policies, despite having export potential. Instead, the RMG industry has been the major beneficiary of the incentives and facilities specified in these policies.

D Institutional Space, Political Settlement, and Deals Space Favouring RMG

The RMG sector in Bangladesh grew in an environment of very ‘weak’ institutions (see Chapters 2 and 3). Against the poor quality of institutions, the country became the second largest exporter of RMG in the world. How do we reconcile these two contrasting scenarios? If we look at the well-known institutional indicators (World Governance Indicators (WGI), Doing Business, Transparency International, and Global Competitiveness Index), all refer to the quality of formal institutions. However, in countries like Bangladesh, placed at the lower level of the development spectrum, what governs is a host of informal institutions, and the formal institutions are weak and fragile. Khan’s framework of ‘growth-enhancing institutions’, in contrast to ‘market-enhancing institutions’ (Khan, Reference Khan2012b), elaborates how the role of informal institutions can be critical in developing countries. Some developing countries, especially East and Southeast Asian countries, have been successful in steering unconventional institutions to drive growth. Khan (Reference Khan2012b) further highlights that the success of the RMG industry in Bangladesh was not replicated in any other major sectors, as no rent, such as the RMG industry enjoyed, was available for other sectors. The critical element in the institutional arrangement which allowed the take-off of this industry was the global institutional mechanism with the MFA and favourable domestic factors. The MFA facilitated fortuitous rents on terms that assisted the learning-by-doing that was critical for the RMG sector. With the high quota-rent, the quota utilisation rate for Bangladesh in the US market in 2001–2002 was much higher than the rates of other developing countries (Yang and Mlachila, Reference Yang and Mlachila2007).Footnote 14

Khan (Reference Khan2012b) further points out that the authoritarian clientelism during the early phases of the sector’s take-off allowed the rapid solution of a number of institutional constraints facing the sector, especially in the form of the poor quality of formal institutions. Many of these solutions were ‘unorthodox’ in nature (e.g. back to back letter of credits), and a ‘political settlement’Footnote 15 among the elites in Bangladesh on the RMG industry helped the industry to grow. This ‘political settlement’ was initially based on rent-sharing, and later evolved as the economic interest of RMG business owners coincided with the political interest of governments in terms of employment generation (especially female employment) and poverty alleviation.

As discussed in Chapter 1, the deals environment framework, proposed by Pritchett et al. (Reference Pritchett, Sen, Werker, Pritchett, Sen and Werker2018) relates to the idea of ‘deals space’. Informal institutions, which are prevalent in developing economies, may also take the form of ‘deals’ among the political and economic elites, in contrast to the formal rules guiding the relationship between these actors that exist in advanced countries. Deals can be open (access is open to all) or closed (access is restricted), and they can also be ordered (deals are respected) or disordered (deals are not respected). According to this view, countries are likely to exhibit high growth when deals are open and ordered, and thus deals become closer to formal institutions.

Informal institutions can have two distinct roles with respect to the stages of development. At an early stage of development, if countries can steer informal institutions so that they are ‘growth-enhancing’, as well as ensuring that the ‘deals space’ is more ordered (either open or closed), countries can achieve strong economic growth and also some improvements in the social sector. However, for the transition from a lower to a higher stage of development, whether the country can maintain a high growth rate and achieve further development goals depends on the dynamics of how informal institutions evolve, and whether formal institutions become stronger and functional. Not many developing countries have been able to do this. Certainly, the East Asian and most of the Southeast Asian countries are success stories in using informal institutions efficiently at the early stage of development, as well as achieving some notable successes in the transition to functional formal institutions.Footnote 16

In contrast to many other comparable countries in Asia and Africa at a similar stage of development, and especially in comparison to the LDCs, the country group to which Bangladesh belongs, Bangladesh has been successful in creating some efficient pockets of ‘growth-enhancing’ informal institutions, against an overall distressing picture as regards its formal institutions. The examples of ‘pockets of efficient informal institutions’ in Bangladesh include the well-functioning privileges and special arrangements for the RMG sector.Footnote 17

However, the next question is how did Bangladesh create such ‘pockets of efficient informal institutions’ and make the ‘best’ use of them? The explanations include both historical and political economy perspectives. The 1971 liberation war led to the emergence of an independent Bangladeshi state which for the first time gave unprecedented and enormous independent power to the burgeoning political and economic elites of the Bengali nation. Also, the people, in general, enjoyed some benefits of this power. To a great degree, the entrepreneurial nature of the people of this country is deeply rooted in this feeling of power.Footnote 18 Successful entrepreneurship is seen in the case of the RMG sector. As Bangladesh is not rich in natural resources, elites saw in the RMG sector the basis of the generation of substantial rents (the sources of rents in the RMG sector were discussed earlier in this chapter).

While Khan (Reference Khan2012b) rightly mentions the institutional perspectives behind the growth of the RMG sector, his narrative of the ‘political settlement’ is rather narrow and elite-centric. Khan’s ‘political settlement’ is primarily an ‘elite agreement’, and it overlooks the critical nexus between elites and non-elites within the society. Through large-scale employment generation in the RMG sector and its induced effects of poverty alleviation and female empowerment, the business elites were also able to draw support from both the political elites and non-elites in the society.

Using the lens of the ‘deals space’ of Pritchett et al. (Reference Pritchett, Sen, Werker, Pritchett, Sen and Werker2018), Hassan and Raihan (Reference Hassan, Raihan, Pritchett, Sen and Werker2018) argue that the RMG sector as a whole has enjoyed closed deals, and parts of the closed deals actually have legal and quasi-legal bases (bonded warehouse schemes, cash incentives, statutory regulatory ordinances, etc.), but these tend to be highly exclusive in nature. The ‘state capture’ by the RMG lobbies is manifested in the form of ensuring special privileges for them, and a high presence of RMG businesses among members of parliament. From the perspective of an individual RMG entrepreneur, bypassing the Bangladesh Garments Manufacturing and Exporters Associations (BGMEA) and maintaining bilateral interfaces with the state’s regulatory authority, in relation to duty-free import processes, would be prohibitively costly, in terms of the informal transaction costs that would be incurred and the excessive amount of time the process would entail. Therefore, the ‘deals environment’ became more ‘closed’ and the system became more ‘formal’, through voluntary compliance of individual firms with the BGMEA. Also, the individual firms also saw quite a rapid shift from a relatively disordered deal environment (during the late 1970s and early 1980s)Footnote 19 to an ordered deals environment in the subsequent decades. The transition occurred not only because of government prodding in relation to private sector development (through statist policy inducement) but also largely due to market actors’ strong incentive to ensure their survival and expand in a globally competitive market. The enactment of various beneficial rules and myriad forms of deals benefitting the RMG sector was mainly the outcome of effective demands and skilful negotiations by a sector that is characterised by strong collective action capability, thanks to the economic and political clout it gradually came to possess.

As was pointed out earlier, the RMG sector as a whole enjoys privileges that are quite extraordinary. For instance, the state has delegated the authority over rule enactments and enforcement of these rules to its collective forum BGMEA, as well as to Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturing Associations (BKMEA). The most prominent power held by these organisations is the power to issue customs certificates – utilisation declarations (UDs) and utilisation permits (UPs)Footnote 20 governing the duty-free importing process. This act by the state tends to blur the distinction between legality and illegality.Footnote 21 In this sense, one can legitimately categorise such privileges as de facto deals, since they are exclusive to this sector and indicate the RMG sector’s ability to generate and preserve a de facto closed deal environment that has allowed it to accrue substantial rent for decades, and also to achieve spectacular economic performance.Footnote 22

Over the decades, RMG owners came to be the most powerful and the best organised business group in Bangladesh. The political power of this group derives from its high contribution to economic growth, close political integration with the state (including parliamentary representation) (Rashid Reference Rashid2008), and the class basis of the owners: former military and bureaucratic officials and the white collar managerial class were the pioneers of RMG sector (Rashid, Reference Rashid2008; Kabeer and Mahmud, Reference Kabeer and Mahmud2004). The political power of the RMG sector is manifested in the extraordinary tax privileges and subsidies that it has enjoyed during the last three decades. These exemptions and financial incentives have not changed over the decades, despite the fact that the sector has witnessed substantial expansion over time.

E Subcontracting in the RMG Industry in Bangladesh

As the industry grew, the need for subcontracting increased. A large factory has a maximum production capacity (e.g. number of shirts per month), even taking into account some allowed overtime. When orders are larger than what can be produced by the business receiving the order, work is subcontracted. This is necessary to balance production capacity and order size. As buyers moved towards wanting to deal with only a few factories, subcontracting became even more important (Cookson, Reference Cookson2017). In recent years, subcontracting has received a bad name. Buyers believe, usually correctly, that factory compliance is not met by subcontractors. The compulsion to demand compliance leads to a reluctance to allow subcontracting. Demands for compliance have many impacts on RMG costs, but a hidden, very significant cost is the difficulty experienced in using subcontracting (Cookson, Reference Cookson2017). In particular, after the Rana Plaza accident in 2013, and the stringent scrutiny by the Accord and Alliance, the number of subcontracting firms declined drastically.Footnote 23

F ‘Political Settlement’ Regarding the Management of the Labour Regime in the RMG Sector

The labour regime in the RMG sector has been managed quite extraordinarily over the past decades. Most workers work in sweatshop conditions. However, the issue only appears in the global media when major fatal accidents occur, like that at the Rana Plaza in 2013. Long working hours, low wages, lack of regular contracts, and systemically hazardous conditions are often reported (Uddin, Reference Uddin2015; Berik and Rodgers, Reference Berik and Rodgers2010). Trade unions, when allowed, are unable to protect their workers. Not all ‘Fundamental’ International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions have been ratified, and their concrete application is far from the norm. The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises fix good standards of corporate social responsibility for Western brands operating in such countries, but they are not binding and do not provide for sanctions if they are not applied. In practice, they have failed to defend workers’ rights. While there has been growing unrest from workers, which has led to strikes and protests, their main achievement has been some increases in the minimum wage, which remains far below a living wageFootnote 24 (Lu, Reference Lu2016). Also, subcontracting has been used as a way of escaping constraints.

Trade unions are often suppressed, and union organisers intimidated, including physically. Workers claim that some managers mistreat employees involved in setting up unions, or force them to resign (Bhuiyan, Reference Bhuiyan2012; Parry, Reference Parry2016). Some claim they have been beaten up, sometimes by local gangsters who attack workers outside the workplace, and even at their homes. The lack of regular contracts means many workers who are injured in factory fires, and the relatives of those who die, do not receive any compensation because they are not registered as formal employees of the companies and the management therefore does not identify them as their workers. The biggest strength that Bangladesh has over its competitors is its cheap and vast workforce. The minimum wage in Bangladesh in the RMG industry is among the lowest in the top RMG-producing countries (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 Minimum monthly wage for garment workers in 2018 (measured in US$).

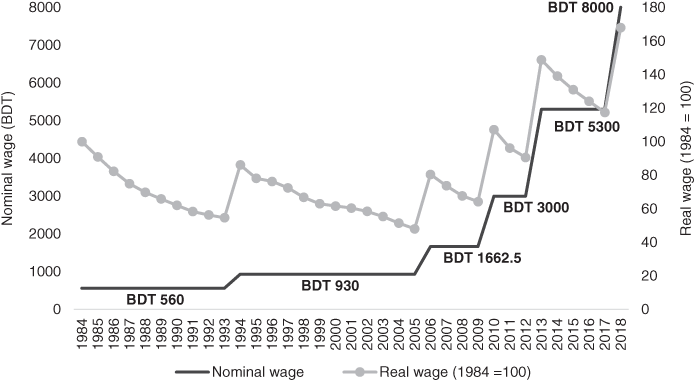

After the inception of an export-oriented RMG sector in 1978, the first wage board, formed in 1984, set a minimum wage for the sector’s workers at Bangladeshi Taka (BDT) 560 a month (Figure 4.4). This shows that the country’s first wage board for fixing the salaries of workers in the garment sector was constituted long after Bangladeshi entrepreneurs ventured into the RMG business, which suggests the weak bargaining power of the workers in this sector. This low minimum wage continued for the next 10 years, despite the erosion of purchasing power due to inflation (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 Minimum wage in the RMG sector in Bangladesh (BDT).

In the following three and half decades, five more wage boards were constituted, at very irregular intervals. The second (in 1994) and third (in 2006) wage boards were established at 10-year and 12-year intervals, respectively. Periodic labour unrest, with the demand for an increase in the minimum wage, led to relatively more frequent revisions of the minimum wage after 2006, and a political settlement evolved as workers became more important for political elites in the political game than in the past. Nevertheless, during the almost four decades of the RMG industry’s existence, the minimum wage in the industry was kept very low. This was done with the support of the state, whoever was in power. Figure 4.5 also suggests that, in real terms, the value of minimum wages declined over time, even in those years when they were kept fixed in nominal terms. The real increase was 60% between 2010 and 2018. More or less the same evolution is found for 2000–2010, but the increase was only 20% in the decade before. Of course, the loss in real terms is due to the infrequency of the wage adjustments.

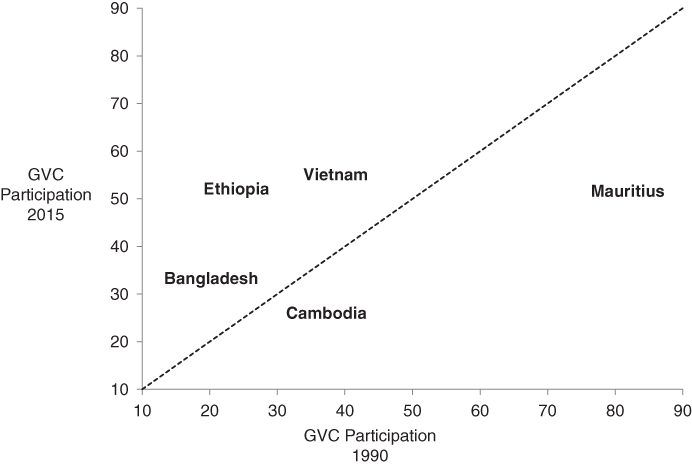

Figure 4.5 GVC participation: Bangladesh and comparators.

Notes: GVC measures from the EORA MRIO national and global input–output tables covering the period 1990–2015. GVC participation measures are the sum of the backward and forward participation rates expressed as shares of gross exports (see text), excluding double counting of exports when intermediates cross borders multiple times. Points above the 450 indicate an increase in GVC participation over the period.

The minimum wage is set in Bangladesh’s RMG sectorFootnote 25 through a process that involves the Government forming a new minimum wage board for the RMG sector, to formulate a new wage structure for RMG workers. The board is usually led by a senior district judge, as chairman. In addition to representatives from the owners and workers, the board also consists of three independent members. The representatives of owners and workers separately propose a minimum wage for the workers and propose this to the board. After discussions with stakeholders, the board recommends a new wage structure based on the inflation rate, living costs, the country’s economic condition, and strength of the sector as regards paying the settled wage. The wage board then publishes a gazette and gives the workers’ and owners’ representatives a 14-day period in which to appeal if there have any objection to the recommendations. The board finalises the new wage structure taking into consideration the objections of workers’ and owners’ representatives, if there are any. The wage board then passes the wage structure to the Ministry of Labour and Employment, which reviews the proposed wage structure and sends it to the Ministry of Law for vetting. After approval is obtained from the Ministry of Law, the Ministry of Labour and Employment publishes a gazette notification and the new wage structure enters the implementation phase. Once the gazette notification is issued, all export-oriented garment manufacturers are bound to implement the new wage structure in their factories. The new wage structure comes into effect from the date set by the Government.Footnote 26 However, there are allegations that workers’ voices are not heard properly in the wage board as the board includes no ‘true’ representatives of workers.Footnote 27

There also exists a gender wage gap in the RMG industry in Bangladesh. Menzel and Woodruff (Reference Menzel and Woodruff2019), using data from 70 large export-oriented garment manufacturers in Bangladesh, showed that among production workers, women’s wages were 8% lower than those of men. A study by ILO-SANEM (2018), using survey data from 111 RMG factories, also found a similar gender wage gap.

G Poor Factory Compliance and a Weak Regulatory and Monitoring Mechanism

The RMG industry started with small factories as it was easy to set up a small garment factory: one could establish a factory by renting space, buying 50–100 sewing machines, wiring up the factory for electricity, hiring and training the workers, getting a contract for a small order of simple garments, and going to work. Sourcing, pricing, and quality control were learned by doing. The profits were high, and therefore small companies could get established. There was no ban on entry (Cookson, Reference Cookson2017).

Systemic hazardous conditions are a common feature of many factories in this sector. The rapid expansion of the industry led to the adaptation of many buildings that were built for other purposes – residential, for instance – into factories, often without the required permits. Other plants have had extra floors added or have increased the workforce and machinery to levels beyond the safe capacity of the building. Lack of appropriate protective equipment, old and outdated wiring that is at risk of short circuiting (a major cause of fires), and non-existent or outdated fire extinguishing facilities are often reported in these overcrowded workplaces. Fire exits are often deliberately blocked by factory owners, and windows even barred, thus increasing the death toll in accidents (D’Ambrogio, Reference D’Ambrogio2014).Footnote 28 Poor factory compliance persisted for a long time due to a weak regulatory and monitoring mechanism. The Department for Factory Inspection (DIFE), under the Ministry of Labour and Employment, established in 1969, is entrusted with the responsibility for monitoring the compliance of factory conditions. However, due to DIFE’s numerous institutional challenges related to weak capacity, corruption, and a lack of interest from the Government in strengthening DIFE, it failed to perform its duties. After the Rana Plaza accident in 2013, there has been an effort to enhance DIFE’s capacity.Footnote 29

H Rent Generation and Management through RMG By-products

The business of rent generation and management through the RMG by-product jhut (the scrap from clothing items) is an important aspect of the RMG industry. Previously, jhut was a waste product produced by RMG factories, but it has now become a by-product of the industry, since it has commercial value. A newspaper report,Footnote 30 citing the Bangladesh Garment and Textile Waste Exporters Association (BGTEA), highlights that the market size of RMG by-products is over BDT 2,000 crore (around US$ 2.4 billion, equivalent to 1% of GDP). RMG factories in Bangladesh produce over 400,000 tonnes of by-products annually.Footnote 31 The simple scraps of fabric that are a by-product of making RMG generate new jobs, especially for women in the informal sector. Some 150,000 people are currently employed in the informal, small-scale operations of this potentially lucrative sector.Footnote 32

The business of re-using wasted cloth is a three-step process. First, a person, usually a locally influential person, collects the cloth forcibly or via negotiations. Second, it is sold to the re-use or recycling business. Third, the final product is then sold to different consumers and exported. After collection, the process of recycling starts with sorting, which is done by the colour, type, and size of the fabric. Larger scraps of cloth are used to make children’s frocks, skirts, shirts, pyjamas, and sometimes pillow covers. Large scraps of fabric are sold to local traders to make garments for children. Most of these children’s clothes are sold in Bangladesh but some are exported to India. Dhaka’s bedding industry is dependent on jhut. Mattresses, pillows, cushions, and seat stuffing and padding in cars, public buses, and rickshaws use recycled cloth and processed cotton.Footnote 33

Because of the lucrative nature of this business, locally influential people seek to obtain more jhut through influencing either workers or mid-level management of the factories. Many factories have faced unrest resulting from the politics involved in the jhut business.Footnote 34 This high rent from the jhut business, through legal and illegal means, also makes the RMG industry more attractive than any other export-oriented sectors.

V Sustainability Challenges of the RMG-Centric Export Model

A Increased Competition in the Global Market

In recent years, Bangladesh’s share of global RMG exports has increased steadily. In 2012, the share was 4.66%; this had increased to 6.19% by 2017.Footnote 35 The increased share of global RMG exports shows that, despite numerous challenges, Bangladesh’s RMG industry has been able to strengthen its market share at the global level. With the increased share in the world market, in recent years, Bangladesh has become the second largest exporter of RMG in the world. After China, its closest competitors are Vietnam and India. It can be mentioned that, in 2006, Bangladesh ranked sixth on the list of top RMG exporting countries, with a share of only 2.8%.Footnote 36

However, there is also a very high concentration of products in the RMG industry in Bangladesh. An analysis using the Trade MapFootnote 37 data suggests that while, products conforming with the six-digit Harmonised System (HS) code level, the top 10 RMG products account for around 68% of total RMG exports in Bangladesh, for China, India, and Vietnam, the figures are 35.5%, 45.6%, and 42.1%, respectively. Moreover, the top five products account for 53.3% of Bangladesh’s RMG exports, whereas the figures are only 22.7%, 28.7%, and 25% for China, India, and Vietnam, respectively. Another important concern is that Bangladesh’s RMG exports face stiff competition, especially from China and Vietnam. The 16 products conforming with the six-digit HS code level are common among the top 25 RMG products, both in the cases of Bangladesh vs. China and Bangladesh vs. Vietnam. The EU, Bangladesh’s largest export destination, has extended duty-free access to Vietnam, under the EU–Vietnam Free Trade Agreement, which eliminates the competitive edge that Bangladesh had held over Vietnam in RMG exports to the EU market.Footnote 38

B Diversification within RMG and Quality Issues

While Bangladesh’s export basket remains highly concentrated around RMG exports, diversification within the RMG sector remains a big challenge. According to the data from WTO, products conforming with the six-digit HS code level, just 10 RMG products accounted for 70% of the total RMG exports from Bangladesh in 2017/18. Just two products (T-shirts and men’s trousers) accounted for 36% of RMG exports in that year. Most of these are low-value and basic-quality products. According to the Global Sourcing Survey 2018 by AsiaInspection, Bangladesh is still an attractive source of low-cost RMG items.Footnote 39

Attempts within the RMG industry to move up the ladder to high-value and high-quality products have not been very successful. According to IMF (2014), at the four-digit Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) level, only three RMG products have been of higher quality compared to Bangladesh’s major competitors, China, India, and Vietnam, and the advantage Bangladesh has in these three products is marginal.Footnote 40 However, it should be mentioned that while Bangladesh no longer has any duty-free market access or GSP facility in the USA,Footnote 41 presently Bangladesh enjoys a 12% ‘margin of preference’Footnote 42 for its RMG industry under the EU’s EBA initiative (United Nations Department for Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA, 2019).

C The Segmented RMG Value Chain in Bangladesh

Mercer-Blackman (Reference Mercer-Blackman2016) argues that, ideally, successful structural transformation in Bangladesh should consist of two types of processes at this juncture: (i) diversification away from garments into other manufactures by producing goods that entail increasingly more complex manufacturing processes compared to garments, but that are still similar enough that it is easy for workers and managers to master these processes; or (ii) linking to the fashion industry global production chain and providing increasingly more complex and valuable parts of garments: for example, through increasing involvement in the design process of the garment. If the country chose avenue ‘ii’ – that is, moving up the fashion industry value chain – increasing overall productivity will be very difficult because of the segmented nature of the value chain. It will thus be much easier for Bangladesh to make products that are similar to garments, such as footwear or small appliances, than to begin to understand and master the various aspects of designing and retailing clothes.

Mercer-Blackman (Reference Mercer-Blackman2016) further argues that there are two main reasons why the fashion industry value chain is segmented for Bangladesh. First, the value buyers attribute to clothes – reflected in the price they are actually willing to pay – is the result of a process occurring in a place that is geographically and information-wise very far from Bangladesh, at the retail end, where fashion fads and volatile markets operate in a complicated way. Second, there is a broken link of accountability once the garment is shipped abroad. The sector’s production process is completely decoupled informally from the fast-fashion production process. This segmentation also exacerbates the dissociation between the unit cost of production in Bangladesh and its retail price: factories sometimes send the clothes with the price tag – even the sales price – so they are floor-ready. It is possible to send one box to New York with shirts price-tagged at US$ 50 each and the identical box to rural New Jersey with shirts price-tagged at US$ 5 each. The price is completely independent of the actual cost. As long as the big buyers maintain price-setting power, garment makers have no incentive to upgrade facilities or enhance workers’ skills because race-to-the-bottom, cost-cutting measures will always take precedence, to guarantee a firm’s survival. Moreover, because of the focus on meeting orders on time, firms have little leeway to become more proactive in anticipating buyers’ needs.

Bangladesh’s place at the lower end of the value chain is also related to the fact that RMG factories are predominantly locally owned in Bangladesh. By contrast, in Cambodia, also a large exporter of basic garments, factories are owned mostly by foreign investors. In the case of Bangladesh, local factory owners are economically powerful business persons who have managed to find ways to bypass the institutional weaknesses and inadequate infrastructure, which is difficult for foreign investors. There are also limits on the input side as the industry is dependent on the large-scale import of machinery and raw materials. There is also a lack of sufficient supply of skilled domestic workers to operate sophisticated machinery, let alone maintain it (ADB-ILO, 2016).

D Increased Pressure on Workplace Safety and Compliance

There are concerns with regard to compliance issues and workplace safety in the RMG industry in Bangladesh, and in the last few years, especially after the infamous Rana Plaza accident in 2013, these issues have become critical for the future of this industry (Box 4.2). There is strong international pressure, in the form of the threat of cancelling large preferential treatment in the markets of Western countries, if labour conditions are not improved.Footnote 43 Quality competitiveness is being increasingly prioritised over price competitiveness, and, of course, the quality of a product tends to increase the standard of living of labour being used in the production process. These concerns should be addressed in a positive way, by seeing them as an opportunity to build the industry’s reputation in the global market. This calls for, among many other things, a more careful engagement with labour issues in the RMG industry. In this context, issues like wages, workplace security, fringe benefits, workplace environment, etc. need to be resolved on a priority basis. Current labour practices prevalent in the RMG industry need to be improved in order to make the sector sustainable. The improvement of labour conditions is closely linked to the enhancement of labour productivity. There is equally a need to invest in training workers to move to high-value garment products (i.e. men’s suits, baby garments, lingerie, and sportswear).

Box 4.2 Bangladesh after Rana Plaza: from tragedy to action

Customers:

The 13 May 2013 Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh was signed by the IndustriALL Global Union and UNI Global Union trade unions, and more than 180 enterprises, most of them European. The Accord is to run for five years and is aimed at strengthening safety and fire inspections in the textile industry, and improving workers’ health and occupational safety. The Accord provides for the inspection of more than 1,600 factories, the cost of which will be borne by the signatories in proportion to the value of their orders.

North American companies took a separate initiative on 10 July 2013, named the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety. It was launched by a group of 26 North American brands and covers 700 factories. The Alliance is non-binding and less stringent, as regards freedom of association, than the 13 May 2013 Accord.

International Community:

On 8 July 2013 in Geneva, as a response to the Rana Plaza tragedy, the European Commission, the ILO, and the Government of Bangladesh launched the Compact for Continuous Improvements in Labour Rights and Factory Safety in the Ready-Made Garment and Knitwear Industry in Bangladesh. This Compact seeks to improve labour, health, and safety conditions for workers, as well as to encourage responsible behaviour by businesses in the RMG industry in Bangladesh. In particular, it set out a road map for implementing an action plan, including: reforming Bangladeshi labour laws (in particular regarding freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining); recruiting 200 additional factory inspectors by the end of 2013; and improving building and fire safety, by June 2014.

The ILO launched the Better Work Programme for Bangladesh on 23 October 2013. It covered 500 factories and ran for three years. Factory assessments were due to begin during the second quarter of 2014. The programme had been conceived well before the Rana Plaza tragedy.

Bangladeshi Government:

A National Tripartite Plan of Action on Fire Safety and Structural Integrity in the Garment Sector of Bangladesh (NTPA) was adopted on 25 July 2013 by the Bangladeshi Government, manufacturers in the sector (BGMEA and BKMEA), and the local unions. It acts as a platform to coordinate the various projects and initiatives to improve working and safety conditions in the textile industry. On this basis, a Ready-Made Garment Programme, in partnership with the ILO, was approved on 22 October 2013 and will run for three and a half years. The NTPA will inspect the 1,500 factories not due to be inspected under either the Accord or the Alliance.

Rana Plaza Compensation Scheme:

Following the Rana Plaza tragedy, an arrangement was signed on 20 November 2013 and a Donors’ Trust Fund, run by the ILO, was set up. Some US$ 40 million was expected to be collected for distribution among the victims. So far, just less than US$ 18 million has been collected. An advance payment has been made available to injured workers and the families of deceased and missing workers.

A study by ILO-SANEM (2018) suggests that, despite some improvements after the Rana Plaza accident in 2013, there are still unresolved issues related to occupational safety, hours of work and leave, fixing and execution of minimum wage provisions, workplace training, workplace harassment, and gender equality.

E The Evolving Political Settlement on the Labour Regime

After multiple incidents, including the Tazreen fire and the Rana Plaza collapse, Bangladesh came under international scrutiny for its labour practices and safety standards. However, RMG workers in the country are still being paid one of the world’s lowest minimum wages. The success of the fashion industry in the West is built on the ‘exploitation’ of workers from countries like Bangladesh, who struggle every day to survive above the poverty line. The sector’s vision of achieving US$ 50 billion worth of RMG exports by 2021 shows little concern for the well-being of its workers. Oxfam (2017) highlights that for every garment sold in Australia, only 4% of its price goes to the factory workers who made it. Cheap labour is the main factor on which Bangladesh’s RMG industry capitalises when it comes to attracting big retail brands. The RMG sector faced severe labour unrest demanding a wage increase in 2006. Since then, labour unrest has taken place in the sector almost every year. This is threatening the political settlement between the political elite and RMG owners, or at least modifying its conditions.

F Crisis in the Deals Environment of the RMG Sector

Hassan and Raihan (Reference Hassan, Raihan, Pritchett, Sen and Werker2018) argue that despite experiencing massive political and reputational crises (e.g. the Rana Plaza disaster), labour movements for higher wages, intense global pressures for ensuring factory standards, and social compliance and labour’s associational rights, the RMG sector has managed to perform reasonably well. During the previous decades, its high performance, notwithstanding the many domestic challenges the industry faced, was possible due to the combination of close and ordered deals that it enjoyed in the economic domain. In the political domain, a robust and resilient anti-labour elite political settlement (between RMG owners and political elites) across political divides has enabled it to cope with the sustained movements and critiques that it faced from labour, media, and human rights actors, both local and global. This settlement has recently become increasingly vulnerable to both domestic and international pressures as the Government might side with labour if pressures do increase.

In the economic domain, the decades-long closed and semi-closed deals are now being questioned by the state and local and global stakeholders. BGMEA has vigorously protested any such policy reform initiatives. Its political capacity to successfully thwart similar policy initiatives many times in the past has proved the robustness of the hitherto elite political settlement. With the crises the sector is now facing, its continuing high performance and its ambition to grow further will largely depend on the nature of the evolving political settlement and the deals that it will be able to renegotiate with political elites, and also on how and to what extent it will be able to neutralise the de facto national/global reputation of its actors as greedy entrepreneurs, promoters of economic injustice, and violators of labour/human rights.

G Automation in the RMG Sector and Implications for Job Creation

Technological advances associated with automation raises the concern that new technologies will lead to widespread job losses in manufacturing industries in countries like Bangladesh. What is perhaps different now is that new, interconnected digital technologies will likely have a broader and more far-reaching array of abilities, and so the prospect of new kinds of jobs appearing may well be diminished or limited to increasingly sophisticated domains. In addition, new technologies are now not just replacing jobs, they are also enabling the disruption and restructuring of entire industries (Hamann, Reference Hamann2018).

Between 2013 and 2016/2017, manufacturing jobs in Bangladesh declined by 0.8 million. A major part of this was in the RMG industry (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, 2018). Increased use of automation also changed the composition of the labour in the RMG sector. Raihan and Bidisha (Reference Raihan and Bidisha2018) show that the RMG factories that were closed down after the Rana Plaza event in 2013 were mostly the ones that were comparatively female labour-intensive. Furthermore, the introduction of labour-saving machinery was speeded up after the Rana Plaza event for the kind of jobs which were previously done mostly by low-skilled female workers, which caused employment loss in respect of female labour. Also, there is a perceived threat of automation to employment, and this affects women disproportionately. Already there is evidence of RMG workers being displaced by automation in Bangladesh.Footnote 44 There are a few applications of automation in important manufacturing industries related to RMG, a few companies have taken steps to implement automation in their operations, and this automation is increasing.Footnote 45

H The Challenges of LDC Graduation

Bangladesh successfully met all three criteria for graduating out of LDC status in the first review in 2018 and in the second review in 2021 and will finally graduate out of LDC status in 2026. Such a graduation carries with it a risk of preferences for Bangladesh being eroded.

UNDESA (2019) argues that Bangladesh would lose access to DFQF arrangements for LDCs, and to simplified ROO reserved for LDCs, with especially important impacts on the RMG sector. In its main market, the EU, Bangladesh would remain eligible for DFQF market access under the EBA scheme for a period of three years after graduation, given the scheme’s ‘smooth transition’ provision. After that, the terms under which it would have access to the EU market would depend on the new GSP regulation, as the current regulation will expire at the end of 2023 (before Bangladesh’s expected graduation date). Under current rules, Bangladesh would in principle have access to the standard GSP, whereby it would face higher but still preferential tariffs. Most of Bangladesh’s RMG exports would face tariffs of 9.6% in the EU under the GSP, which would result in increased competition from Bangladesh’s competitors. Bangladesh’s exports would also have to comply with more stringent ROO to benefit from the GSP than it is required to comply with, as an LDC, to benefit from the EBA. Bangladeshi RMG exports currently benefit from the single transformation rule for LDCs, whereby products qualify for preferential treatment if only one form of product alteration is undertaken in the country, as opposed to the double-transformation rule for non-LDCs, whereby two stages of conversion are required. Despite Bangladesh having had access to the EBA since 2001, it was only after the simplification of the rules in 2011 that the country was able to fully benefit from the preferences, as the country relies significantly on imported inputs, particularly in the case of woven RMG. Woven RMG would be most affected by application of the double-transformation rule.

UNDESA (2019) further argues that no important impacts are expected in the US market, since Bangladesh’s most important products are not covered by an LDC-specific preference scheme. Bangladesh has been suspended from the GSP scheme (including preferential tariffs for LDCs) since 2013 due to labour safety issues. Among other developed country markets, in Canada, Japan, and Australia, the standard GSP does not cover an important part of Bangladesh’s exports, which will face MFN tariffs. Moreover, in some countries, such as Canada and Australia, Bangladesh would no longer be able to use dedicated ROO for LDCs, making it more difficult to benefit from preferences for the tariff lines covered by the standard GSP than it is to use the GSP for LDCs. Among major developing country markets, Turkey, Bangladesh’s largest importer of jute and jute products, has aligned its GSP scheme to that of the EU. In India and China, still relatively small destinations for Bangladesh’s exports but important due to potential and proximity, Bangladesh would no longer benefit from the DFQF treatment reserved for LDCs and would instead export under the Asia-Pacific Trade Agreement (APTA) (for China and India), the South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) (in the case of India), and MFN rates.

Raihan (Reference Raihan2019a), using a global dynamic general equilibrium model, suggests that due to the loss of preferences after graduation from LDC status, in the markets of the EU, Canada, Australia, Japan, India, and China, Bangladesh might see a sizeable drop in exports of RMG compared to the business-as-usual scenario. The scenario in the model considers the imposition of MFN tariff on imports from Bangladesh in the markets of the EU, Canada, Australia, Japan, India, and China. According to the model simulation, the drop in RMG exports would be US$ 5.4 billion in 2024 (13.5% of RMG exports), which could further fall to US$ 5.8 billion by 2030 (10.8% of RMG exports).

VI Challenges of the Diversification of Exports in Bangladesh

A Weak Collective Action of Non-RMG Sectors

Future potential export sectors are leather and footwear, agro-processing, electronics, pharmaceuticals, ICT, light engineering, and ship building.Footnote 46 Unlike the RMG sector, these sectors tend to have weak collective action capacity, which is a liability (for a sector as a whole) when operating in a predominantly deals world. This weakness in collective action capacity is perhaps due to the small numbers of firms involved in these sectors. Also, unlike the RMG sector, no ‘accidental rent’ (in the form of the MFA) has enabled any of these sectors to take off in a robust manner, except for the pharmaceutical sector, which has been enjoying such rent for the last few decades (e.g. through the exemption from patent rights under Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which will continue until 2033).

B Inadequate Policies and Strategies That Hurt Non-RMG Sectors

Though Bangladesh’s export and import policies are supposed to provide unbiased facilities to all export-oriented sectors, there is an inherent pro-RMG bias in policies and strategies for export diversification in Bangladesh. This is also reflected in a statement by the Md Mosharraf Hossain Bhuiyan, Chairman of the National Board of Revenue, on 3 May 2019: ‘In case of diversification, we will give the same facilities that we are giving to the garment sector this year’. At present, the apparel sector enjoys a host of benefits, including a 4% cash incentive on exports to new destinations, lower corporate tax, and a bonded warehouse facility.Footnote 47 However, as Box 4.3 suggests, there are inherent biases towards the RMG sector in the bonded warehouse facility, and many of these biases are deals-based.

Box 4.3 Blessings for RMG are a misfortune for leather: the case of bonded warehouses

| RMG sector | Leather goods sector |

|---|---|

| Audits take place every two or three years | Annual audits |

| Direct exporters are exempt from annual entitlement process for accessing imported inputs | Annual entitlement process for imported input based on machinery and previous years’ production |

| Utilisation rates used to acquit duty liability set by industry body with industry expertise | Utilisation rates used to acquit duty liability set by customs, with little industry experience |

| Allowed to use multiple premises of bonded warehouses (within 60 kilometres) on a single licence | Allowed to use single premises only |

| Goods may be sent to subcontractors as part of the process | Goods cannot be sent to subcontractors as part of the manufacturing process |

| Not required to house full-time Bond Commissionerate staff on site | Bond Commissionerate station’s full-time staff on site, with licensee required to pay towards their salaries |

The new export policy for fiscal year 2018/2019 to fiscal year 2020/2021, like in the past, also highlights the importance of diversification of the export basket. Leather gets a special focus in the new export policy and the benefits enjoyed by the RMG industry are supposed to be extended to the leather industry. Also, in the new export policy, the number of highest-priority sectors has been raised to 15 from the existing 12, and the number of special development sectors has been raised to 19 from the existing 14. Like in past export policies, the new policy also mentions special benefits, including subsidies and tax benefits, for the priority and special development sectors. This new policy also mentions extending easy term loans and other banking facilities from the Export Development Fund (EDF) of the Bangladesh Bank to export-oriented industries.

However, as already mentioned, though export policies identify ‘thrust’ or ‘priority’ or ‘special development’ sectors with a view to promoting the development of potential export items, many of these sectors are probably not in a position to reap the benefits of the incentives reserved for them. For example, although the Government’s cash incentiveFootnote 48 plays a vital positive role in the export of agro-food processing products, exporters complain about difficulties in gaining access to this subsidy as a result of bureaucratic and other procedural obstacles. Many firms have also complained about the duty drawback system, as the process is cumbersome and bureaucratic in nature and takes a long time to finish (Raihan et al., Reference Raihan, Lemma, Khondker and Ferdous2017c). Also, though the Government has set up the EDF to provide pre-shipment financing for imports of raw materials, and support to exporters of new and non-traditional items, many of the non-RMG sectors have been unable to exploit the benefits of the scheme, and so far, the RMG sector has been the prime beneficiary of this facility. Stringent rules and regulations are identified as the major hindrances shutting out many of the non-traditional export-oriented industries from the Government stimulus package meant for export promotion, diversification, and growth (Rahman, Reference Rahman2015). Also, there are allegations that the EDF only benefits big companies.Footnote 49 Therefore, it seems that before formulating policies and schemes, it is important to undertake sector-specific diagnostic studies so that structural and policy constraints can be identified, in order to devise the most appropriate incentives.