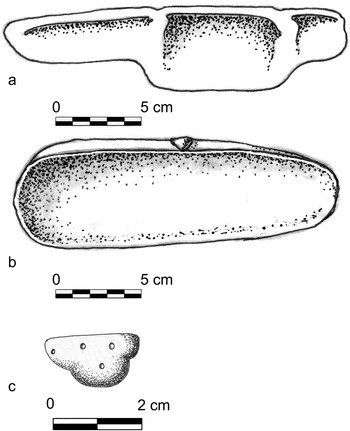

Jade has been long recognized by archaeologists as an important trade item among ancient Mesoamerican cultures. This is particularly true for ancient Olmec and Maya cultures where it is seen as an indicator of social status. Among the most unusual objects documented in Mesoamerica are jade “spoons.” These objects take one of two forms: a single oval piece or a tri-lobed shape (Figure 1). Along with debates as to the actual function of these objects, there is an issue regarding their origins, although both forms are commonly referred to in the literature as Olmec jade spoons (see Benson and de la Fuente Reference Benson and La Fuente1996:255–256; Covarrubias Reference Covarrubias1946:172; Graham Reference Graham and Jones1998; Snarskis Reference Snarkis, Quilter and Hoopes2003).

Figure 1. (a) Illustration of tri-lobe jade “spoon” pendant from Uxbenka (from photo by author); (b) illustration of “clamshell” jade spoon from La Venta (from photo Drucker Reference Drucker1952:Plate 53); (c) illustration of “spangle” from La Venta (from photo Drucker Reference Drucker1952:Plate 58). Illustrations by author.

While the first form of the object, the single oval piece often referred to as a “clamshell spoon,” was found at La Venta (Stirling Reference Stirling1943:323, see also Plate IV), no physical examples of the second type of tri-lobed “spoon” were found at La Venta or other sites within the Olmec cultural “heartland.” However, numerous examples of the latter form have been recovered from several sites throughout the Maya region. The ascribing of tri-lobed “spoon” pendants to the Olmec appears to be due to a conflation of two artifacts from La Venta: the “clamshell spoons” and tri-lobed “spangles” (Drucker Reference Drucker1952:170–171). The tri-lobed “spangles” found at La Venta, while similar in possessing a T-shape, differ from the tri-lobed “spoon” pendants found in the Maya area in several significant ways, including their size; the former being significantly smaller than the Maya objects and convex in cross-section with holes drilled straight through the objects (Drucker Reference Drucker1952:Plate 58; Drucker et al. Reference Drucker, Heizer and Squier1959). This shape is the opposite of the Maya objects that are characterized by a distinctive depression (Figure 1), and with the placement of the holes in the Maya objects indicating that they were meant to be suspended as pendants.

Despite the long-standing attribution in the literature of both “spoon” forms as “a specific type of Olmec artifact” (Pohorilenko Reference Pohorilenko2006:17; see also Coe Reference Coe, Wauchope and Willey1965; Turner Reference Turner2022:263), it is this author's view that the continued reference to the tri-lobed pendant as Olmec is inaccurate and misleading. Reviewing the artifacts and evidence presented in the literature, I argue that the attribution of the tri-lobed “spoon” pendants to the Olmec is based on superficial visual attributes and ingrained concepts of primacy as opposed to archaeological evidence. As the use of a cultural descriptor for objects can have repercussions on interpretations (see Brady and Coltman Reference Brady and Coltman2016), it is important to revisit our assumptions, particularly when there is a lack of clear evidence for the association or when it is contrary to new evidence. It is the position of this author that recent discoveries from the Maya Lowlands suggest that the origin of these tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendants may lie in Maya culture. As such, the continued use of the term “Olmec” to describe these objects may not only miscredit the works of Maya lapidary artisans but also obscure what may be a unique Maya expression of a wider Middle Formative Mesoamerican behavior or practice.

Jade “Spoon” Pendants

The term “spoon” is loosely applied to a variety of objects, with the term initially used by Stirling in 1943 in his National Geographic Magazine article announcing the finds at La Venta (Stirling Reference Stirling1943:323). However, the photo that accompanied Stirling's original article (Stirling Reference Stirling1943:Plate IV) shows items identical to one later described by Drucker in his reexamination of the objects found in the Mound A-2 tomb as a “clamshell-shaped jade pendant” (Drucker Reference Drucker1952:Plate 53). This piece was described as having a concave face with a “realistically shown” hinge (Drucker Reference Drucker1952:163, see also Plate 54a). The slightly asymmetrical oval shape with concave face and clear hinge corresponds with other objects also described as clamshell pendants (Andrews Reference Andrews and Andrews V1986:27, 29–30; Gann Reference Gann1918:91, Plate 16a; Graham Reference Graham and Jones1998:48; Hammond et al. Reference Hammond, Clarke and Belli1992:Figure 5; Snarskis Reference Snarskis1979; Zralka et al. Reference Zralka, Koszkul, Martin and Hermes2011).

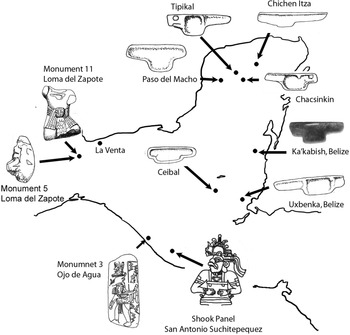

While these concave clamshell-shaped objects can be connected directly to the Olmec through their discovery at La Venta, the same cannot be claimed for tri-lobed variants. An examination of the photographs and descriptions of La Venta artifacts (see Drucker Reference Drucker1952:170–171, and Plate 58; Drucker et al. Reference Drucker, Heizer and Squier1959) show that while the objects from La Venta are the same general shape as the tri-lobed objects under discussion, they differ in several significant ways. In fact, in his reexamination and cataloguing of artifacts from La Venta Drucker clearly distinguishes the clamshell from the tri-lobed objects, referring to the first as pendants and the latter as spangles (Drucker Reference Drucker1952:170–171). First, the La Venta spangles are much smaller, averaging 1–2 cm in length and less than 1 cm in thickness, in comparison to the tri-lobed “spoon” pendants that range in size from 7 to 18.5 cm in length. Second, although the tri-lobed “spoon” pendants and spangles may share a similar general T-shaped form, the three parts of the tri-lobed pendants vary in proportions with one side being longer, and in some cases tapering toward the tip (Figure 1). Third, the La Venta objects have multiple perforations drilled directly through the faces of the objects. The configuration of the holes in the “spangles” suggest they were “intended for attachment on some article of clothing” (Drucker et al. Reference Drucker, Heizer and Squier1959:149) and likely sewn directly on clothing as depicted on Monument 5 at Loma del Zapote (Figure 2). The tri-lobed objects from the Maya area all have L-shaped holes at the top and were clearly intended to be suspended like a pendant, making them more akin to the clamshell-shaped pendants than the spangles. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, in his description Drucker describes the spangles as “an ellipse, or half ellipse, with a tab, usually rounded, on one side” (Drucker Reference Drucker1952:171), indicating that they lack the depression that characterizes the pendant pieces.

Figure 2. Map showing locations of statues and spoons (illustrations by author and not to scale; adapted from Andrews Reference Andrews and Andrews V1986:Figure 1a; Cyphers Reference Cyphers2004:172; Castillo and Inomata Reference Castillo Aguilar and Inomata2011; Healy and Awe Reference Healy and Awe2001:Figure 2; Hodgson et al. Reference Hodgson, Clark and Murrieta2010:Figure 2; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1974; Shook and Heizer Reference Shook and Heizer1976; Zorich Reference Zorich2020).

The tri-lobed “spoon” pendants have at least one concavity, either in one of the lobes or encompassing all three lobes; variations on this theme are noted with some objects possessing three separate concavities (one on each lobe). The presence of a depression that may have served as a receptacle was a key component in classifying these objects as “spoons,” and this characteristic makes them closer in form, and possibly function, to their clamshell-shaped counterparts. Although the term “tri-lobed pendant” is probably more accurate for artifacts, the use of the term spoon to describe these objects is well-embedded in the literature.

Presumed Functions and Meaning

A variety of functions have been suggested for the tri-lobed “spoon” pendants, ranging from esoteric to quotidian. Pohorilenko (Reference Pohorilenko and Benson1981, Reference Pohorilenko, Benson and de la Fuente1996) refers to the objects as “tadpoles,” creatures that could serve as symbols of the watery underworld and sea of creation. Tate and Bendersky extend this watery, amorphous creature view of the objects and argue that they represent human fetuses at roughly 26 days of gestation (Tate Reference Tate2012:43; Tate and Bendersky Reference Tate and Bendersky1999) and are part of a larger corpus of carved imagery dealing with gestation, birth, and creation (Tate Reference Tate2012).

Alternatively, it is suggested that tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendants share an ideological meaning with ik’-shaped pendants (Hammond Reference Hammond, Grove and Joyce1999; Hammond et al. Reference Hammond, Clarke and Belli1992:Figure 5) and pendants with ik’ symbols carved on them (Prager and Braswell Reference Prager and Braswell2016; Taube Reference Taube2005). This symbol, which appears widely in Classic Maya art, is seen carved on celts and as discrete objects such as pendants where it has been linked to ideas of breath, air, wind, life, and the soul (Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000:267; Fitzsimmons Reference Fitzimmons2009:29; Taube Reference Taube2005:32). Turner (Reference Turner2022:268) draws parallels between the ik’ form and shells, noting “cross-sectioned conch shells” symbolized wind in other parts of Mesoamerica. In this regard, tri-lobed pendants may encode a shared Mesoamerican ideological meaning, if not form or function, to the La Venta spangles.

Follensbee (Reference Follensbee2008) argues that the objects served a practical purpose, that of being weaving tools. However, this argument fails to address the lack of use-wear reported on the objects, although it is possible that these were symbolic, nonfunctioning weaving implements. More significant is that while textiles are known to have been considered a high-status trade good during other periods of Mesoamerican history, their production is ascribed to women (Chase et al. Reference Chase, Chase, Zorn and Teeter2008; Halperin Reference Halperin2008; Hendon Reference Hendon2006; Stark et al. Reference Stark, Heller and Ohnersorgen1998). While it is possible that particularly high-status individuals who wished to display their weaving skills wore these jade tools, there is no evidence to link these pieces with women.

More recently, Turner (Reference Turner2022) makes the convincing argument that these pieces are jade skeuomorphs meant to represent marine bivalves, specifically those in the genus Pteria, and suggests using the term “wing oyster pendant” in place of the more common “spoon” or “spoon pendant” (Turner Reference Turner2022:266). He notes that the presence of tri-lobed “spoon” pendants in imagery on monuments outside the Maya area, but the lack of physical objects may be due to the pendants in these areas being made from a less durable material (e.g., shells from Pteria sp.; Turner Reference Turner2022:264). While Turner's idea regarding the skeuomorphic origin of the shape has merit, he follows in the footsteps of other researchers and assumes that these objects, including the jade forms, are Olmec, speculating that the “spoon” pendants found at Chichen Itza and Uxbenka were possibly “collected by Classic-period Maya from Middle Formative deposits, or were perhaps kept as heirlooms” (Turner Reference Turner2022:263). As noted earlier, that the pendants’ shape may have been part of widely shared Mesoamerica symbolic imagery and encoded similar meaning is not in question; however, the origin of the jade forms of these objects warrants reconsideration. Turner's observation regarding the lack of physical pendants in areas outside of the Maya region merely reinforces the idea that tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendants are a particular Maya expression associated with what is undoubtably a larger shared Mesoamerican practice.

Spanning both the practical and abstract spheres is the idea that the objects, both tri-lobed and clamshell, were used in ritual activities to hold substances such as hallucinogens for inhalation or to catch blood drawn in bloodletting rituals (Furst Reference Furst1974:5–6; Griffin Reference Griffen and Benson1981:219; Snarskis Reference Snarkis, Quilter and Hoopes2003:7–8). Their use as a means of ingesting hallucinogens is also speculated upon by Furst, who notes the presence of similar concavities in objects found in Brazil that are believed to have been used as receptacles for snuff (Furst Reference Furst and Benson1968:162; see also Wassén Reference Wassén and Efron1967). If the T-shaped objects did share a ritual purpose akin to the clamshell “spoon” pendants, which have been recovered from archaeological context throughout Mesoamerica (Andrews Reference Andrews and Andrews V1986:27, 29–30; Gann Reference Gann1918:91, Plate 16a; Graham Reference Graham and Jones1998:48; Hammond et al. Reference Hammond, Clarke and Belli1992:Figure 5; Snarskis Reference Snarskis1979; Zralka et al. Reference Zralka, Koszkul, Martin and Hermes2011), it again raises the likelihood that the jade forms are idiosyncratic Maya expressions of items that belong to a large assemblage of objects with shared function and meaning.

Distribution of Tri-lobed “Spoon” Pendants and Related Imagery

It is clear these pieces, like other early jade items, played an “important role in ancient ceremonial life” and were likely “used by high-status personages as insignia and worn as pectoral ornaments” (Benson and de La Fuente Reference Benson and La Fuente1996:255–256). Middle Formative carved jade objects, such as “clamshell pectorals,” have been interpreted as important parts of early regalia symbolizing divine rulership and the evolution of kingship (Clark and Colman Reference Clark and Colman2014:15, 22; Graham Reference Graham and Jones1998). Moreover, discussion of a jade pectoral from Nim li Punit, Belize, shows that these items were important parts of Maya royal insignia through the Classic period (Prager and Braswell Reference Prager and Braswell2016).

Three sculptures depicting rulers wearing this type of tri-lobed “spoon” pendant exist: the Shook Panel reportedly from San Antonio Suchitepéquez, Guatemala (Shook and Heizer Reference Shook and Heizer1976); Monument LZ-11 from Loma del Zapote, Veracruz (Cyphers Reference Cyphers2004:256, Figure 172); and Monument 3 from Ojo de Agua, Chiapas (Hodgson et al. Reference Hodgson, Clark and Murrieta2010). The most securely dated of these pieces is Monument 3 from Ojo de Agua, which, based on associated ceramics, is dated to the Jocotal phase of the Early Formative (Hodgson et al. Reference Hodgson, Clark and Murrieta2010:139), which Clark (Reference Clark and Fowler1991:Figure 2) places between 1000 BC and 900 BC. Monument LZ-11 from Loma del Zapote, like many other pieces from that site (Cyphers Reference Cyphers2004:29), regrettably has “no context” (Cyphers Reference Cyphers, Grove and Joyce1999:168). Although the origin of the Shook Panel is cited as San Antonio Suchitepéquez, Guatemala, “the site from which it was recovered is not known” (Shook and Heizer Reference Shook and Heizer1976:1), and as such it lacks “any archaeological context which might give us any hint of its age” (Shook and Heizer Reference Shook and Heizer1976:4). Based on its artistic style, Parsons (Reference Parsons1986:12) places the Shook Panel in the Late Olmec period (ca. 900–700 BC), while Taube, using chronological terms derived from the Maya area, refers to this piece as Middle Formative using the same artistic basis (Taube Reference Taube1976:74).

Taube's use of the term “Middle Formative” to describe the monument from San Antonio Suchitepéquez highlights the fact that these monuments are either contemporaneous with or only slightly earlier than the physical pendants excavated in the Maya area, all which date to the Middle Formative period. The jade pendant from Cache 145 at Ceibal dates to the Real 2 phase (ca. 850–800 BC; Inomata and Triadan Reference Inomata and Triadan2015:79), while the pendant excavated from Ka'kabish dates slightly later (800–600 BC). Dates from Paso del Macho for the Tzimin jades place the cache between 900 BC and 350 BC (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Bey and Negrón2020).

The monuments vary in form with the Loma del Zapote Monument LZ-11 being the torso of a human figure (Cyphers Reference Cyphers2004:256), the San Antonio Suchitepéquez monument being a “nearly round flattened stream boulder” (Shook and Heizer Reference Shook and Heizer1976:1), and Monument 3 from Ojo de Agua being “a rectangular, flat slab (Hodgson et al. Reference Hodgson, Clark and Murrieta2010:139). Both the San Antonio Suchitepéquez monument and Monument 3 are low bas relief carvings and therefore quite different from the Loma del Zapote statue, which was carved in the round. However, all three monuments clearly portray an individual wearing a T-shaped pendant with a slightly distended end (Cyphers Reference Cyphers2004:Figure 172; Hodgson et al. Reference Hodgson, Clark and Murrieta2010:Figure 3; Shook and Heizer Reference Shook and Heizer1976:Figure 1). The way the objects are depicted suggests that they were suspended around the wearer's neck as a pendant, as opposed to sewn on clothing. This suggestion is supported by the location and types of holes found in many of the tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendants, perforations that are located along the long edge and exit through the back, creating an L-shape that leaves the front surface unmarked. Additional evidence that these objects were suspended on necklaces comes from a burial at Ka'kabish, Belize, where a tri-lobed “spoon” pendant was found in association with the remnants of a shell necklace (Haines Reference Haines2012).

It is significant that while images of people wearing tri-lobed pendants are found in the Central Isthmian and Pacific Coast area, no tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendants have been recovered in this area. In addition, they have not been found in the Olmec heartland, nor at “any other major site with monumental carvings in the Olmec style” (Pohorilenko Reference Pohorilenko2006:17). Rather all these objects to which archaeological context can, even loosely, be ascribed come from the Maya area (Figure 2): Chichen Itza (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1974), Chacsinkin (Andrews Reference Andrews and Andrews V1986, Reference Andrews1987), Uxbenka (Healy and Awe Reference Healy and Awe2001), Tipikal (Peraza Lope et al. Reference Peraza Lope, Delgado and Escamilla2002:Foto 17), Ceibal (Castillo and Inomata Reference Castillo Aguilar and Inomata2011), Ka'kabish (Haines Reference Haines2012; Haines et al. Reference Haines, Gomer and Sagebiel2014; Lockett-Harris Reference Lockett-Harris2016), and Paso del Macho (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Bey and Negrón2020).

Ka'kabish and Its Tri-lobed Jade “Spoon” Pendant

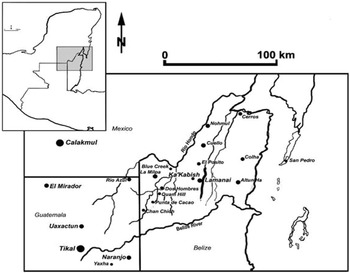

Ka'kabish is located on a ridge in north-central Belize approximately 10 km to the northwest of the New River Lagoon (Figure 3), and 25 km east of the Rio Bravo Escarpment (Lohse Reference Lohse, Lohse and Valdez2004:121). This topographic feature is considered to represent a cultural, as well as physical, divide between the occupants of the Three Rivers Region (part of the Central Petén cultural sphere) and the Belizean coastal groups. The location of Ka'kabish on this ridge was likely strategic as well as practical. It not only placed the original settlement well above the rich dark alluvial soil that surrounds the site, and is known to suffer inundations during heavy rains, but it also provided a vantage point from where the occupants could watch the surrounding area. The site is clearly visible from both the Rio Bravo Escarpment and the top of the High Temple at Lamanai, as well as several other points across the region.

Figure 3. Map showing location of Ka'kabish, Belize.

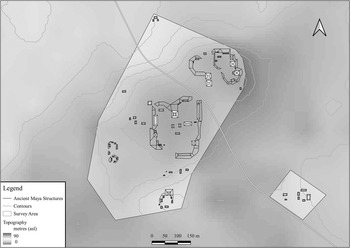

The site core consists of 32 structures arranged around two large plazas: Group D and Group F. The site is surrounded by several courtyard groups as well as several smaller residential clusters (Figure 4). Investigations in these areas revealed that Ka'kabish had a long history of occupation starting in the Middle Formative period ca. 800 BC and lasting until the contact period in the sixteenth century (Haines et al. Reference Haines, Sagebiel and McLellan2020). Material evidence from the site indicates that through its long history, its inhabitants participated in far reaching trade networks (Haines and Shugar Reference Haines and Shugar2017).

Figure 4. Map of Ka'kabish showing core and immediately adjacent courtyard groups.

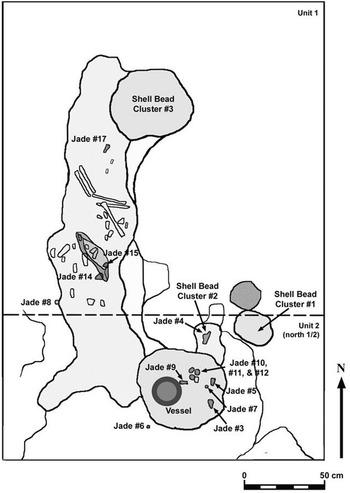

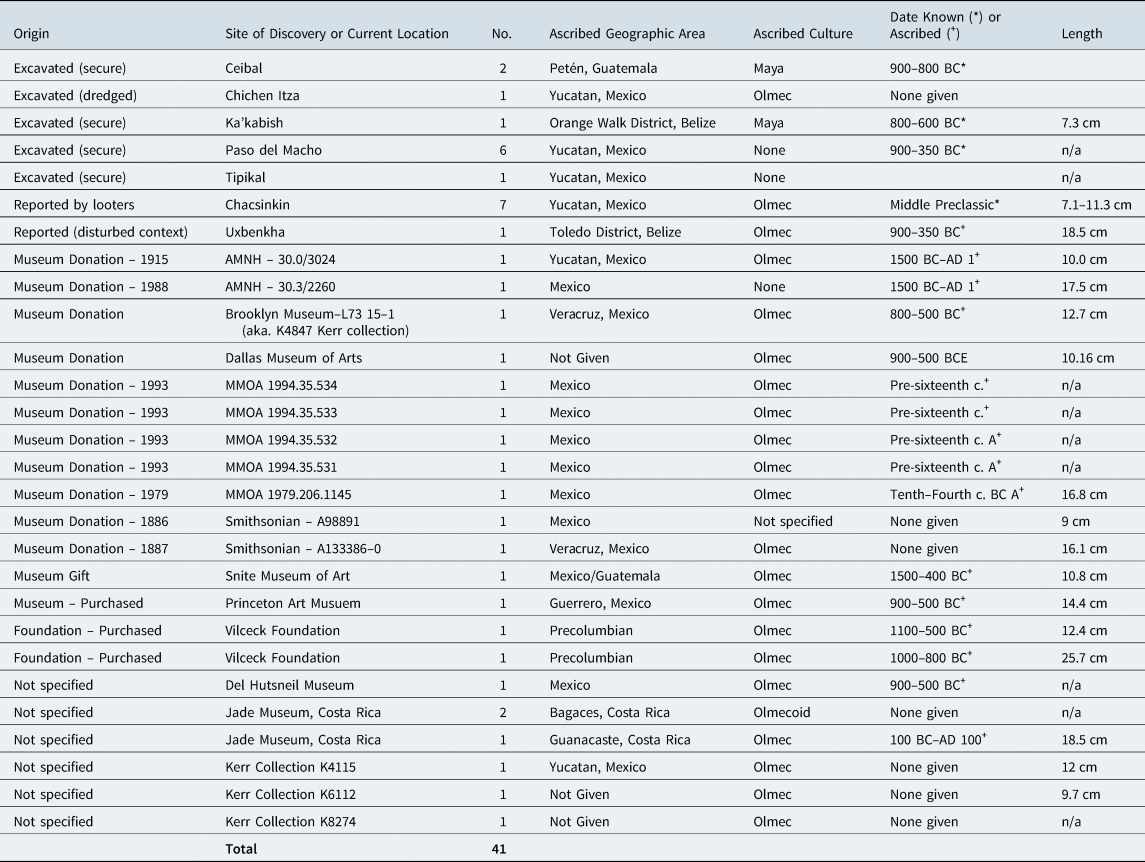

Excavations into the southeast plaza area of Group D revealed a wealth of items, including numerous pieces of jade associated with pits carved into the bedrock that date to the latter part of the Middle Formative period (ca. 800–400 BC). While the diameter of most of these pits was quite small (i.e., less than 30 cm; Lockett-Harris Reference Lockett-Harris2016), two large round pits at either end of a long, north-south oriented depression were discovered (Figure 5). The central cavity contained the bundled remains of an individual while the two pits at either end, as well as the area immediately around the remains, contained many long-distance trade goods, leading us to surmise that these three interconnected pits contained a founder burial and accompanying mortuary offerings (Haines Reference Haines2012).

Figure 5. Map of Ka'kabish burial pit (spoon is Jade #4).

Mortuary offerings recovered from these three pits included a small Consejo Red-Striated bowl (Haines et al. Reference Haines, Gomer and Sagebiel2014; Sagebiel and Haines Reference Sagebiel and Haines2017), more than 515 marine shell beads of various sizes, likely manufactured from Strombidae species (Stanchly Reference Stanchly, Haines and Tremain2013), and 17 jade objects (Haines Reference Haines2012; Lockett-Harris Reference Lockett-Harris2016). The jade used ranged in color from deep greens to greenish-white flecked stone. Although these items are referred to as being jade, many may not be true jade but rather any one of a wide range of rocks of mineralogical compositions and quality. Hammond and colleagues have argued that the variety in the material used by the Maya to produce objects suggests that it was the color green rather than the material that made these sources significant and consequently they are perhaps better described as social jade (sensu Hammond et al. Reference Hammond, Aspinall, Feather, Hazelden, Gazard, Agrell, Earle and Ericson1977:61; see also Kovacevich and Callaghan Reference Kovacevich and Callaghan2019). Jade items recovered in association with the burial not only varied in terms of color and potential quality of material but also in type of object. The assemblage included one small tubular bead, two small round beads, three pendants, two plaques, eight chunks or semiworked pieces, and one tri-lobed “spoon” pendant (Locket-Harris Reference Lockett-Harris2016).

The jade “spoon” pendant found at Ka'kabish measures roughly 7.5 × 3 cm and is 0.7 cm thick. It is asymmetrical in form, with the right lobe being longer and narrower than the left lobe. The latter lobe is incised with a circle and line, giving it the impression of a bird (Figure 6). The object has two discrete depressions, the first in the larger central lobe and the second on the right lobe. The abrupt termination of the right depression at the end of the lobe suggests that the object may have originally been longer. Two L-shaped holes are carved in the piece running from the top edge to the back of the pendant. Recovered from the southern pit, the “spoon” pendant was found in clear association with a cluster of 150 marine shell beads. The arrangement of the “spoon” pendant in conjunction with the shell beads indicates that when deposited they likely were part of a single offering: a shell necklace with a suspended “spoon” pendant.

Figure 6. Photo of Ka'kabish jade spoon.

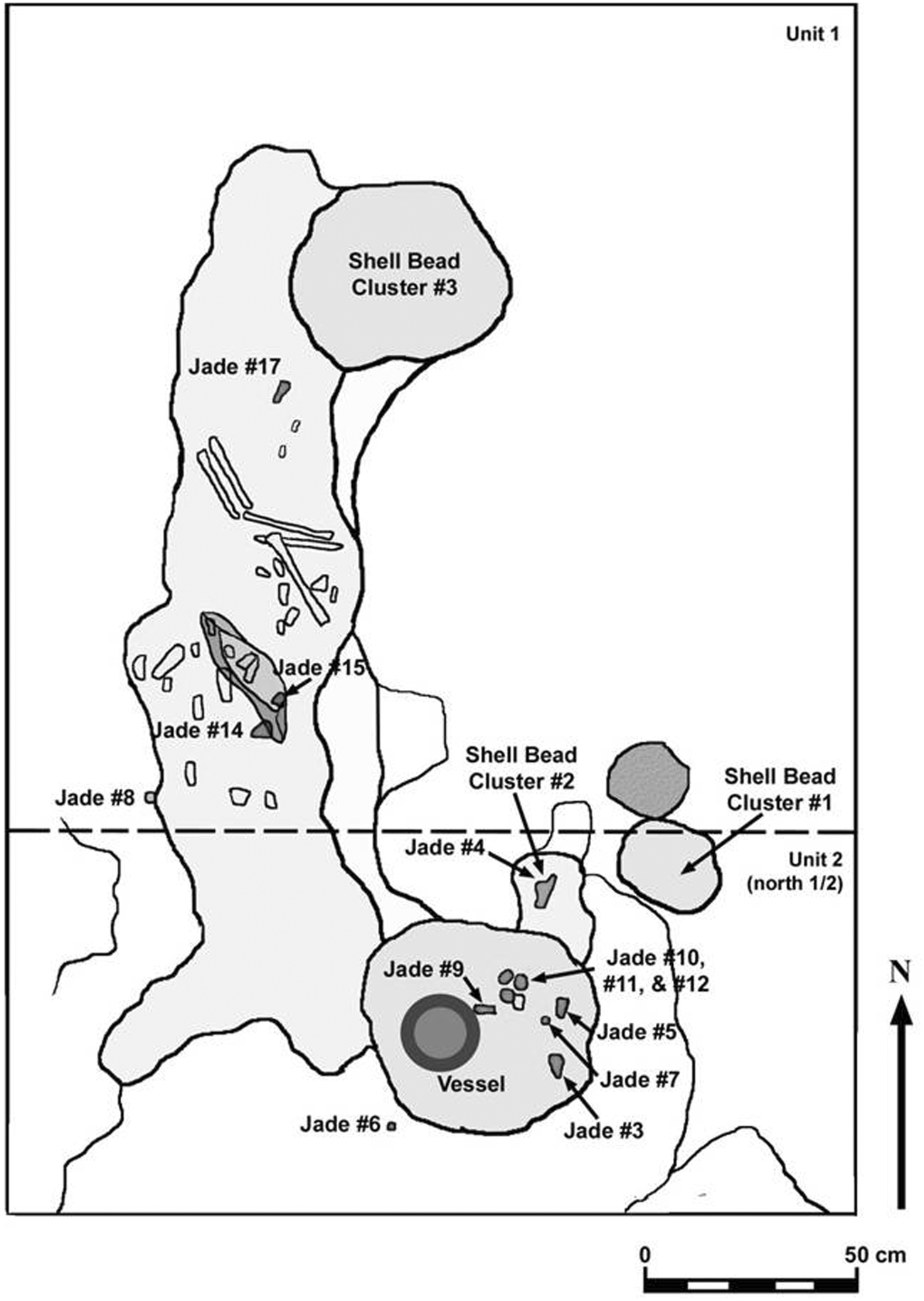

An Overview of Other Identified Tri-lobed “Spoon” Pendants

A total of 41 objects identified as jade “spoon” pendants were identified during this study (Table 1). All pendants correspond to the general description in that they are manufactured of jade and tri-lobed with at least one depression, although this may in some cases encompass all three lobes of the objects in a single depression. Nineteen of the “spoon” pendants identified for this study are currently in museum collections; 16 of these are in the United States and three are in the Jade Museum, Costa Rica (Basler Reference Basler1974:20; see Table 1). Of the artifacts held in American institutions, 14 are identified as Olmec, despite the fact that they possess no secure provenance; all but one of the pieces are listed as either being purchased directly by the museum or donated, and as such likely were purchased through the art market prior to being given to the museums by patrons. The means of acquisition for the three pieces in the Museo de Jade in Costa Rica are not specified (Basler Reference Basler1974:20; Graham Reference Graham and Jones1998), although these pieces also are attributed to being Olmec. Additionally, three tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendants may be found in the FAMSI Kerr Collection (K8274, K6112, and K4115), where, despite the lack of provenance, they, too, are described as Olmec.

Table 1. Summary of Tri-lobed Jade “Spoon” Pendants.

Of the remaining 19 tri-lobed “spoon” pendants identified, nine could be categorized as having come from insecure archaeological contexts; that is, while their reporters were informed as to the original location of items, the objects were not recovered in situ during archaeological investigations. One of these was found on the backfill from a looters’ trench at Uxbenka by the site caretaker (Healy and Awe Reference Healy and Awe2001). Another tri-lobed “spoon” pendant that falls into a similar gray area was discovered between 1904 and 1912 as part of the formal investigations by Edward H. Thompson at Chichen Itza. While the object can be securely documented to Chichen Itza, it was dredged from the Sacred Cenote, rendering it impossible to ascertain an exact date for the piece (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1974:ix). Seven tri-lobed “spoon” pendants came from a collection originating at Chacsinkin (Andrews Reference Andrews and Andrews V1986, Reference Andrews1987). Their existence was noticed when pieces from the collection went for sale on the New Orleans art market. An investigation by Andrews tracked the objects back to the site of Chacsinkin where the locals reported having found them in a trench in one of the buildings (Andrews Reference Andrews and Andrews V1986, Reference Andrews1987). Despite being found at Maya sites, all eight objects originally were reported as being Olmec (Andrews Reference Andrews and Andrews V1986), “Olmec in design” (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1974:36), or “most likely of Olmec origin” (Healy and Awe Reference Healy and Awe2001:61). While Andrews, in a subsequent article (Andrews Reference Andrews1987) revises his opinion and clearly states that the pieces were “not from the Olmec Gulf Coast,” he does not state directly where the tri-lobed “spoon” pendants originate. Rather, Andrews ambiguously describes the artifacts as reflecting a “diversity of regional styles” (Reference Andrews1987:79).

In the past two decades, 10 tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendants were recovered from secure archaeological investigations. One of these from Ka'kabish, has already been discussed (see Haines Reference Haines2012; Haines et al. Reference Haines, Gomer and Sagebiel2014; Locket-Harris Reference Lockett-Harris2016). The remaining pieces include two from Ceibal, Guatemala (Castillo and Inomata Reference Castillo Aguilar and Inomata2011; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Pinzón, Palomo, Sharpe, Ortíz, Méndez and Román2017:211, 219, 225, Figure 31; Inomata and Triadan Reference Inomata and Triadan2015:79–80; Ortiz et al. Reference Ortiz, Pinzon, Méndez, Arroyo, Paiz and Mejia2012), one from Tipikal (Peraza Lope et al. Reference Peraza Lope, Delgado and Escamilla2002:265, Photo 17), and most recently six from Paso del Macho (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Bey and Negrón2020). What is of significance here is that all 10 “spoon” pendants from securely excavated contexts, as well as all eight objects from unsecure archaeological contexts, were recovered from sites in the Maya area (Figure 2).

The Issue with Origins

It is not the intention of this article to resolve the issue of function for these objects, nor is it to cast into question the acquisitions practices of museums; rather, it is to argue that the origin of the tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendant form should not be assumed to be Olmec. A subsequent and interrelated intention stemming from this argument is to highlight the automatic and unquestioning attribution of all jade “spoon” pendants to the Olmec, either directly in terms of implying where and by whom they were manufactured or through the more nebulous use of the term “Olmec-style.”

The first tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendant was reported on by Covarrubias who called it a “cucharita” (Reference Covarrubias1946:172, Figure 24). Covarrubias was, according to Pohorilenko (Reference Pohorilenko2006:17–18), not only a friend of Stirling who likely knew about the contents of the stone cache but also “a great connoisseur and enthusiast of Olmec art.” It is highly probable that he adopted Stirling's term for the objects. While the Guerrero object described by Covarrubias does fit the overall description of tri-lobed “spoon” pendants, its lack of provenance is troublesome. Although the item is described as coming from Las Balsas, Guerrero, it was in a private collection when Covarrubias inspected the object, and as such it did not have clear context (Covarrubias Reference Covarrubias1946). While the basin of the “spoon” pendant and tail are crudely carved with Olmec-like imagery, the insecure nature and unclear history of the piece make the automatic and unquestioning assumption of an Olmec origin problematic.

While the presumed and widely cited Olmec origin of tri-lobed “spoon” pendants is tenuously supported by several examples with Olmec imagery, it should be stressed that none of these carved objects are from secure archaeological contexts. Consequently, it is unclear if the imagery is original to the objects or added recently to enhance the value of genuine artifacts. Kelker and Bruhns (Reference Kelker and Bruhns2010:167–168) document two examples where Mesoamerican jades were recarved before appearing on the art market. This practice of enhancing genuine objects to increase their value is not limited to jade objects or even Mesoamerica (Brent Reference Brent2001; MacLaren Walsh Reference MacLaren Walsh2005; Sease Reference Sease2007:156; Taylor Reference Taylor, Benson and Boone1982:109). The apparently widespread nature of faking objects in general, coupled with the general lack of provenience overall for the clear majority of these “spoon” pendants, calls into question the aftermarket provenance attached to these objects and the financial implications for providing a provenance (see Marrone and Betrametti Reference Marrone and Beltrametti2020).

Perhaps nowhere is the assumption of an Olmec origin for these objects in the face of contrary evidence more apparent than in the assessment of a tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendant in the Instituto Nacional de Seguros, San José, Costa Rica. Despite the presence of Maya writing on the reverse, Graham (Reference Graham and Jones1998:52, Plate 28) considered this piece to be Olmec in origin, claiming that the piece was “appropriated by a Maya ruler of the late Formative period (100 BC–AD 100)” and that once carved, the “Olmec spoon, newly inscribed, entered the regalia set of the ruler.” Snarskis (Reference Snarkis, Quilter and Hoopes2003) also suggests that “the Maya inherited, appropriated, or looted some older Olmec jades and modified them” rather than considering a possible non-Olmec origin for these objects (Snarskis Reference Snarkis, Quilter and Hoopes2003:164–165; see also Ortiz et al. Reference Ortiz, Pinzon, Méndez, Arroyo, Paiz and Mejia2012:913).

More recently, Zralka and colleagues (Reference Zralka, Koszkul, Hermes and Martin2012) fell into the same line of thought with a recently discovered clamshell pendant at Nakum. Although the piece was found at a site located in the Central Petén and decorated with Early Classic Maya imagery and hieroglyphs, they assumed that, as the form was similar to pieces found at La Venta, the “pectoral is an Olmec piece that was subsequently reused by the Maya” (Zralka et al. Reference Zralka, Koszkul, Hermes and Martin2012:5). Their explanation of the history of this object has it crafted by the Olmec and transported to the Central Petén during the Early Classic where it is incised before being deposited in the early Late Classic burial. While the interment of heirloom artifacts is documented at Maya sites, the argument that the Nakum piece originated in the Middle Preclassic with the Olmec hinges solely on its form being “analogous to several Olmec spoons or clamshell pendants” (Zralka et al. Reference Zralka, Koszkul, Hermes and Martin2012:5).

It should be reiterated that while jade clamshell-shaped “spoon” pendants can be documented to the Olmec area, jade tri-lobed forms cannot. Moreover, while the two forms may have served a similar function, the physical expression of the object used—single ovate dish versus tri-lobed form with variable depressions—are clearly regionally distinct. The conflation of the two objects and the uncritical attributing of any jade “spoon” to a non-Maya point of origin highlight Estrada-Belli's criticism (Reference Estrada-Belli, Traxler and Sharer2016:225) that scholars have “a preference for searching for cultural innovation outside of the Maya Region.” Moreover, the historic and enduring use of the term Olmec in reference to these objects has perpetuated a long-standing problem of creating “implications of ‘source’ and ‘influence’” for objects where none may actually have existed (Grove Reference Grove and Sharer1989:14).

Arguments that rely on the portability of these jade pendants and the two pieces of imagery from Loma del Zapote and the Pacific coast to support the idea that tri-lobed “spoon” pendants owe their genesis to or were manufactured by the Olmec and exported into the Maya area can be countered using a similar argument. Dress and adornment have been long recognized as a way to encode identity (Aizpurúa and McAnany Reference Aizpurúa and McAnany1999; Kerr Reference Kerr2003; McCafferty and McCafferty Reference McCafferty and McCafferty2012; McCafferty and McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty and Mattson2021; Roach-Higgins and Eicher Reference Roach-Higgens and Eicher1992; Schevill Reference Schevill1986; see also Barnes and Eicher Reference Barnes and Eicher1992; Carter et al. Reference Carter, Houston and Rossi2020; Orr and Looper Reference Orr and Looper2014). Building on this theme, Mollenhauer (Reference Mollenhauer2014:17) argued that the clothing and adornments seen on Olmec monuments could represent “dynastic, religious, and/or political affiliations or even the territories they governed.” Given the idea that the regalia conveyed cultural affiliation, coupled with the lack of physical tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendants and limited appearance of imagery showing individuals wearing these pendants, it can be argued that the sculptures depicted individuals of nonlocal origin (i.e., people from the Maya region). Moreover, as the imagery depicting tri-lobed pendants are largely contemporaneous with the physical examples of tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendants found in the Maya region, it can be argued that the objects, or the knowledge of them, could just as easily have been imported into the Olmec area as outward from it. Grove, in his early assessment of Olmec artistic canons, cautioned that regarding some elements “one must consider the probability that Olmec style first appeared in Pacific Guatemala” before being transferred to the Olmec heartland (Grove Reference Grove, Sharer and Grove1981:238–239), a caveat that appears warranted in considerations of tri-lobed “spoon” pendants.

It is the opinion of this author that the attribution of these items to the Olmec, whether to them directly or to their influence as denoted by the use of the term “Olmec-style,” derives from a misunderstanding of what Stirling originally identified as a “spoon” (Reference Stirling1943:Plate IV), and that his term was conflated with what he termed “spangles.” As such, the continued misattribution of these tri-lobed items as Olmec, or even Olmec-style, particularly where there is no extant evidence to do so or more problematically where the archaeological and epigraphic evidence places them firmly within the context of Maya culture, not only precludes a more in-depth examination of the origin of these items but diminishes our understanding of the early development of rulership and the items used to manifest it among the ancient Maya.

Conclusions

Regardless of whether the idea of a Maya origin for tri-lobed jade “spoon” pendants withstands the test of time, clearly to continue uncritically using the term “Olmec” in describing these objects is at best misleading and at worst inaccurate. The application of this ethnonym not only perpetuates the idea that they are of Olmec origin, but it leads to an a priori belief regarding the physical source of the objects that affects their interpretation, as demonstrated by the analyses by Graham (Reference Graham and Jones1998), Snarskis (Reference Snarkis, Quilter and Hoopes2003), and more recently Zralka and colleagues (Reference Zralka, Koszkul, Hermes and Martin2012). While it is indisputable that T-shaped objects were used by Olmecs as a form of adornment, it is equally clear that the functional use of these items was very different. The morphological similarity in shape and material between the small spangles from La Venta and larger tri-lobed jade “spoons” pendants found at Maya sites, coupled with the use of the term “spoon” in the literature to describe both the tri-lobed and clamshell objects, complicated the issue of origin and led to the fusing of these object types. This fusing led to the idea of an Olmec origin for all “spoon” pendants, clamshell and tri-lobed, becoming entrenched in both the literature and the psyche of Mesoamerican archaeology.

Considering the new evidence emerging from sites in the Maya region, I argue that it is time for a reconsideration of the origin of these tri-lobed “spoon” pendants. To continue to ascribe them to the Olmec in any manner—whether directly as Olmec or as Olmec-style—may not only mask their genuine origin but also obscure their meaning. The inaccuracy in describing tri-lobed “spoon” pendants draws attention to the practice of, and problems inherent in, automatically assuming a cultural association when describing an object, particularly when there is little evidence to support the connection. While future research may or may not produce new ideas that change our interpretations of the meaning of these jade “spoon” pendants, the first step in reinterpreting these objects lies in reevaluating our current ideas regarding how we attribute origin to them. More broadly, our tendency to use long-established labels or ethnonyms without reviewing their validity in light of more recent finds warrants greater attention.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Norman Hammond for his assistance and comments on previous drafts of this article. I also am grateful for the comments of the six anonymous reviewers. I am indebted to the Institute of Archaeology, NICH, Belize, for their continued support of my work at Ka'kabish, and for the issuing of Permit IA/H/2/1/12(08) under which this work was conducted.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Standard Research Grant (410-2009-0722), and a grant from the National Geographic Committee for Research and Exploration (9495-14).

Data Availability Statement

Ka'kabish jade objects are held by the Institute of Archaeology, NICH, Belize. Objects cited in Table 1 as belonging to museums or foundations are held at their respective listed institutions with information acquired through their websites. Data for excavated artifacts other than those from Ka'kabish were gathered through published sources.

Competing Interests

The author declares none.